Cannabis (drug)

Cannabis, also known as marijuana[1] (from the Mexican Spanish marihuana) and by other names,[a] refers to preparations of the Cannabis plant intended for use as a psychoactive drug and as medicine.[2][3][4] Chemically, the major psychoactive compound in cannabis is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC); it is one of 400 compounds in the plant, including other cannabinoids, such as cannabidiol (CBD), cannabinol (CBN), and tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), which can produce sensory effects unlike the psychoactive effects of THC.[5]

Contemporary uses of cannabis are as a recreational drug, as religious or spiritual rites, or as medicine; the earliest recorded uses date from the 3rd millennium BC.[6] In 2004, the United Nations estimated that global consumption of cannabis indicated that approximately 4.0 percent of the adult world population (162 million people) used cannabis annually, and that approximately 0.6 percent (22.5 million) of people used cannabis daily.[7] Since the early 20th century cannabis has been subject to legal restrictions with the possession, use, and sale of cannabis preparations containing psychoactive cannabinoids currently illegal in most countries of the world; the United Nations has said that cannabis is the most used illicit drug in the world.[8][9]

Effects

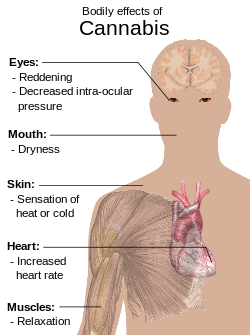

Cannabis has psychoactive and physiological effects when consumed. The minimum amount of THC required to have a perceptible psychoactive effect is about 10 micrograms per kilogram of body weight.[10] Aside from a subjective change in perception and, most notably, mood, the most common short-term physical and neurological effects include increased heart rate, lowered blood pressure, impairment of short-term and working memory,[11] psychomotor coordination, and concentration. Long-term effects are less clear.[12][13]

There are no verified human deaths associated with cannabis overdose. Recorded fatalities resulting from cannabis overdose in animals are also exceptionally rare, generally only after intravenous injection of hashish oil.[14][unreliable medical source?]

Classification

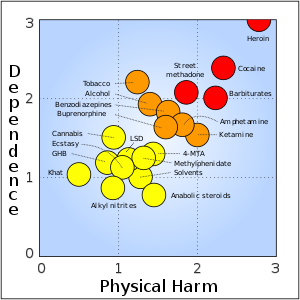

While many psychoactive drugs clearly fall into the category of either stimulant, depressant, or hallucinogen, cannabis exhibits a mix of all properties, perhaps leaning the most towards hallucinogenic or psychedelic properties, though with other effects quite pronounced as well. Though THC is typically considered the primary active component of the cannabis plant, various scientific studies have suggested that certain other cannabinoids like CBD may also play a significant role in its psychoactive effects.[15][16][17]

Medical use

Cannabis used medically has several well-documented beneficial effects. Among these are: the amelioration of nausea and vomiting, stimulation of hunger in chemotherapy and AIDS patients, lowered intraocular eye pressure (shown to be effective for treating glaucoma), as well as general analgesic effects (pain reliever).[b]

Less confirmed individual studies also have been conducted indicating cannabis to be beneficial to a gamut of conditions running from multiple sclerosis to depression. Synthesized cannabinoids are also sold as prescription drugs, including Marinol (dronabinol in the United States and Germany) and Cesamet (nabilone in Canada, Mexico, the United States and the United Kingdom).[b]

Currently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved smoked cannabis for any condition or disease in the United States, largely because good quality scientific evidence for its use from U.S. studies is lacking.[18] Regardless, fourteen states have legalized cannabis for medical use.[19][20] The United States Supreme Court has ruled in United States v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers' Coop and Gonzales v. Raich that it is the federal government that has the right to regulate and criminalize cannabis, even for medical purposes. Canada, Spain, The Netherlands and Austria have legalized some form of cannabis for medicinal use.[21]

Long-term effects

Given the limitations of the research, scientists still debate the possibility of cannabis dependence; the potential of cannabis as a "gateway drug"; its effects on intelligence and memory; its effect on the lungs; and the relationship, if any, of cannabis use to mental disorders[23] such as schizophrenia,[24] psychosis,[25] Depersonalization disorder[26] and depression.[27]

Forms

Unprocessed

The terms cannabis or marijuana generally refer to the dried flowers and subtending leaves and stems of the female cannabis plant.[citation needed] This is the most widely consumed form, containing 3% to 22% THC.[28][29] In contrast, cannabis varieties used to produce industrial hemp contain less than 1% THC and are thus not valued for recreational use.[30]

Processed

Kief

Kief is a powder, rich in trichomes, which can be sifted from the leaves and flowers of cannabis plants and either consumed in powder form or compressed to produce cakes of hashish.[31]

Hashish

Hashish (also spelled hasheesh, hashisha, or simply hash) is a concentrated resin produced from the flowers of the female cannabis plant. Hash can often be more potent than marijuana and can be smoked or chewed.[32] It varies in color from black to golden brown depending upon purity.

Hash oil

Hash oil, or "butane honey oil" (BHO), is a mix of essential oils and resins extracted from mature cannabis foliage through the use of various solvents. It has a high proportion of cannabinoids (ranging from 40 to 90%).[33] and is used in a variety of cannabis foods.

Residue (resin)

Because of THC's adhesive properties, a sticky residue, most commonly known as "resin", builds up inside utensils used to smoke cannabis. It has tar-like properties but still contains THC as well as other cannabinoids. This buildup retains some of the psychoactive properties of cannabis but is more difficult to smoke without discomfort caused to the throat and lungs. This tar may also contain CBN, which is a breakdown product of THC. Cannabis users typically only smoke residue when cannabis is unavailable. Glass pipes may be water-steamed at a low temperature prior to scraping in order to make the residue easier to remove.[34]

Routes of administration

Cannabis is consumed in many different ways, most of which involve inhaling vaporized cannabinoids ("smoke") from small pipes, bongs (portable version of hookah with water chamber), paper-wrapped joints or tobacco-leaf-wrapped blunts.

A vaporizer heats herbal cannabis to 365–410 °F (185–210 °C),[citation needed] causing the active ingredients to evaporate into a vapor without burning the plant material (the boiling point of THC is 390.4 °F (199.1 °C) at 760 mmHg pressure).[35][failed verification] A lower proportion of toxic chemicals is released than by smoking, depending on the design of the vaporizer and the temperature setting. This method of consuming cannabis produces markedly different effects than smoking due to the flash points of different cannabinoids; for example, CBN (usually considered undesirable) has a flash point of 212.7 °C (414.9 °F)[36] and would normally be present in smoke but not in vapor.

Fresh, non-dried cannabis may be consumed orally. However, the cannabis or its extract must be sufficiently heated or dehydrated to cause decarboxylation of its most abundant cannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), into psychoactive THC.[37]

Cannabinoids can be extracted from cannabis plant matter using high-proof spirits (often grain alcohol) to create a tincture, often referred to as Green Dragon.

Cannabis can also be consumed as a tea. THC is lipophilic and only slightly water-soluble (with a solubility of 2.8 mg per liter),[38] so tea is made by first adding a saturated fat to hot water (i.e. cream or any milk except skim) with a small amount of cannabis.

Mechanism of action

The high lipid-solubility of cannabinoids results in their persisting in the body for long periods of time. Even after a single administration of THC, detectable levels of THC can be found in the body for weeks or longer (depending on the amount administered and the sensitivity of the assessment method). A number of investigators have suggested that this is an important factor in marijuana's effects, perhaps because cannabinoids may accumulate in the body, particularly in the lipid membranes of neurons.[39]

Until recently, little was known about the specific mechanisms of action of THC at the neuronal level. However, researchers have now confirmed that THC exerts its most prominent effects via its actions on two types of cannabinoid receptors, the CB1 receptor and the CB2 receptor, both of which are G-Protein coupled receptors. The CB1 receptor is found primarily in the brain as well as in some peripheral tissues, and the CB2 receptor is found primarily in peripheral tissues, but is also expressed in nueroglial cells as well.[40] THC appears to alter mood and cognition through its agonist actions on the CB1 receptors, which inhibit a secondary messenger system (adenylate cyclase) in a dose dependent manner. These actions can be blocked by the selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (rimonabant), which has been shown in clinical trials to be an effective treatment for smoking cessation, weight loss, and as a means of controlling or reducing metabolic syndrome risk factors.[41] However, due to the dysphoric effect of CB1 antagonists, this drug is often discontinued due to these side effects.

Potency

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), "the amount of THC present in a cannabis sample is generally used as a measure of cannabis potency."[42] The three main forms of cannabis products are the flower, resin (hashish), and oil (hash oil). The UNODC states that cannabis often contains 5% THC content, resin "can contain up to 20% THC content", and that "Cannabis oil may contain more than 60% THC content."[42]

A scientific study published in 2000 in the Journal of Forensic Sciences (JFS) found that the potency (THC content) of confiscated cannabis in the United States (US) rose from "approximately 3.3% in 1983 and 1984", to "4.47% in 1997". It also concluded that "other major cannabinoids (i.e., CBD, CBN, and CBC)" (other chemicals in cannabis) "showed no significant change in their concentration over the years".[43] More recent research undertaken at the University of Mississippi's Potency Monitoring Project[44] has found that average THC levels in cannabis samples between 1975 and 2007 have increased from 4% in 1983 to 9.6% in 2007.

Australia's National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre (NCPIC) states that the buds (flowers) of the female cannabis plant contain the highest concentration of THC, followed by the leaves. The stalks and seeds have "much lower THC levels".[45] The UN states that the leaves can contain ten times less THC than the buds, and the stalks one hundred times less THC.[42]

After revisions to cannabis rescheduling in the UK, the government moved cannabis back from a class C to a class B drug. A purported reason was the appearance of high potency cannabis. They believe skunk accounts for between 70 and 80% of samples seized by police[46] (despite the fact that skunk can sometimes be incorrectly mistaken for all types of herbal cannabis).[47][48] Extracts such as hashish and hash oil typicality contain more THC than high potency cannabis flowers.

While commentators have warned that greater cannabis "strength" could represent a health risk, others have noted that users readily learn to compensate by reducing their dosage, thus benefiting from reductions in smoking side-hazards such as heat shock or carbon monoxide.

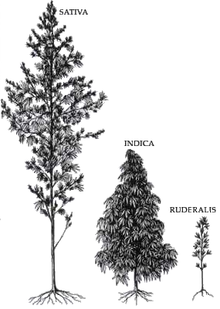

Difference between Cannabis indica and sativa

A Cannabis indica plant may have a CBD/THC ratio 4:-5 times that of Cannabis sativa. Cannabis with relatively high ratios of CBD:THC is less likely to induce anxiety than vice versa. This is be due to CBD's antagonistic effects at the cannabinoid receptor, compared to THC's partial agonist effect. CBD is also a 5-HT1A agonist, which contributes to an anxiolytic effect of cannabis.[49] The relatively large amount of CBD contained in Cannabis indica, means, compared to a sativa, the effects are modulated significantly.[citation needed] The effects of sativa are well known for its cerebral high, hence used daytime as medical cannabis, while indica are well known for its sedative effects and preferred night time as medical cannabis.[citation needed]

Adulterants

Chalk (in the Netherlands) and glass particles (in the UK) have been used to make cannabis appear to be higher quality.[50][51][52] Increasing the weight of hashish products in Germany with lead caused lead intoxication in at least 29 users.[53] In the Netherlands two chemical analogs of Sildenafil (Viagra) were found in adulterated marijuana.[54]

According to both the "Talk to FRANK" website and the UKCIA website, Soap Bar, "perhaps the most common type of hash in the UK", was found "at worst" to contain turpentine, tranquilizers, boot polish, henna and animal feces—amongst several other things.[55][56] One small study of five "soap-bar" samples seized by UK Customs in 2001 found huge adulteration by many toxic substances, including soil, glue, engine oil and animal feces.[57]

Detection of use

THC and its major (inactive) metabolite, THC-COOH, can be measured in blood, urine, hair, oral fluid or sweat using chromatographic techniques as part of a drug use testing program or a forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal offense. The concentrations obtained from such analyses can often be helpful in distinguishing active use from passive exposure, prescription use from illicit use, elapsed time since use, and extent or duration of use. These tests cannot, however, distinguish authorized cannabis smoking for medical purposes from unauthorized recreational smoking.[58] Commercial cannabinoid immunoassays, often employed as the initial screening method when testing physiological specimens for marijuana presence, have different degrees of cross-reactivity with THC and its metabolites. Urine contains predominantly THC-COOH, while hair, oral fluid and sweat contain primarily THC. Blood may contain both substances, with the relative amounts dependent on the recency and extent of usage.[58][59][60][61]

The Duquenois-Levine test is commonly used as a screening test in the field, but it cannot definitively confirm the presence of cannabis, as a large range of substances have been shown to give false positives. Despite this, it is common in the United States for prosecutors to seek plea bargains on the basis of positive D-L tests, claiming them definitive, or even to seek conviction without the use of gas chromatography confirmation, which can only be done in the lab.[62] In 2011, researchers at John Jay College of Criminal Justice reported that dietary zinc supplements can mask the presence of THC and other drugs in urine. Similar claims have been made in web forums on that topic.[63]

Gateway drug theory

Since the 1950s, United States drug policies have been guided by the assumption that trying cannabis increases the probability that users will eventually use "harder" drugs.[64] This hypothesis has been one of the central pillars of anti-cannabis drug policy in the United States,[65] though the validity and implications of this hypothesis are hotly debated.[64] Studies have shown that tobacco smoking is a better predictor of concurrent illicit hard drug use than smoking cannabis.[66]

No widely accepted study has ever demonstrated a cause-and-effect relationship between the use of cannabis and the later use of harder drugs like heroin and cocaine. However, the prevalence of tobacco cigarette advertising and the practice of mixing tobacco and cannabis together in a single large joint, common in Europe, are believed to be cofactors in promoting nicotine dependency among young people trying cannabis.[67]

A 2005 comprehensive review of the literature on the cannabis gateway hypothesis found that pre-existing traits may predispose users to addiction in general, the availability of multiple drugs in a given setting confounds predictive patterns in their usage, and drug sub-cultures are more influential than cannabis itself. The study called for further research on "social context, individual characteristics, and drug effects" to discover the actual relationships between cannabis and the use of other drugs.[68]

Some studies state that while there is no proof for this gateway hypothesis, young cannabis users should still be considered as a risk group for intervention programs.[69] Other findings indicate that hard drug users are likely to be "poly-drug" users, and that interventions must address the use of multiple drugs instead of a single hard drug.[70]

Another gateway hypothesis is that a gateway effect may be detected as a result of the "common factors" involved with using any illegal drug. Because of its illegal status, cannabis users are more likely to be in situations which allow them to become acquainted with people who use and sell other illegal drugs.[71][72] By this argument, some studies have shown that alcohol and tobacco may be regarded as gateway drugs.[66] However, a more parsimonious explanation could be that cannabis is simply more readily available (and at an earlier age) than illegal hard drugs, and alcohol/tobacco are in turn easier to obtain earlier than cannabis (though the reverse may be true in some areas), thus leading to the "gateway sequence" in those people who are most likely to experiment with any drug offered.[64]

A 2010 study published in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior found that the main factors in users moving on to other drugs were age, wealth, unemployment status, and psychological stress. The study found there is no "gateway theory" and that drug use is more closely tied to a person's life situation, although cannabis users are more likely to use other drugs.[73]

History

Cannabis is indigenous to Central and South Asia.[76] Evidence of the inhalation of cannabis smoke can be found in the 3rd millennium BCE, as indicated by charred cannabis seeds found in a ritual brazier at an ancient burial site in present day Romania.[6] In 2003, a leather basket filled with cannabis leaf fragments and seeds was found next to a 2,500- to 2,800-year-old mummified shaman in the northwestern Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China.[77][78] Cannabis is also known to have been used by the ancient Hindus of India and Nepal thousands of years ago. The herb was called ganjika in Sanskrit (गांजा/গাঁজা ganja in modern Indic languages).[79][80] The ancient drug soma, mentioned in the Vedas, was sometimes associated with cannabis.[81]

Cannabis was also known to the ancient Assyrians, who discovered its psychoactive properties through the Aryans.[82] Using it in some religious ceremonies, they called it qunubu (meaning "way to produce smoke"), a probable origin of the modern word "cannabis".[83] Cannabis was also introduced by the Aryans to the Scythians, Thracians and Dacians, whose shamans (the kapnobatai—"those who walk on smoke/clouds") burned cannabis flowers to induce a state of trance.[84]

Cannabis has an ancient history of ritual use and is found in pharmacological cults around the world. Hemp seeds discovered by archaeologists at Pazyryk suggest early ceremonial practices like eating by the Scythians occurred during the 5th to 2nd century BCE, confirming previous historical reports by Herodotus.[85] One writer has claimed that cannabis was used as a religious sacrament by ancient Jews and early Christians[86][87] due to the similarity between the Hebrew word "qannabbos" ("cannabis") and the Hebrew phrase "qené bósem" ("aromatic cane"). It was used by Muslims in various Sufi orders as early as the Mamluk period, for example by the Qalandars.[88]

A study published in the South African Journal of Science showed that "pipes dug up from the garden of Shakespeare's home in Stratford-upon-Avon contain traces of cannabis."[89] The chemical analysis was carried out after researchers hypothesized that the "noted weed" mentioned in Sonnet 76 and the "journey in my head" from Sonnet 27 could be references to cannabis and the use thereof.[90]

Cannabis was criminalized in various countries beginning in the early 20th century. In the United States, the first restrictions for sale of cannabis came in 1906 (in District of Columbia).[91] It was outlawed in South Africa in 1911, in Jamaica (then a British colony) in 1913, and in the United Kingdom and New Zealand in the 1920s.[92] Canada criminalized cannabis in the Opium and Drug Act of 1923, before any reports of use of the drug in Canada. In 1925 a compromise was made at an international conference in The Hague about the International Opium Convention that banned exportation of "Indian hemp" to countries that had prohibited its use, and requiring importing countries to issue certificates approving the importation and stating that the shipment was required "exclusively for medical or scientific purposes". It also required parties to "exercise an effective control of such a nature as to prevent the illicit international traffic in Indian hemp and especially in the resin".[93][94]

In 1937 in the United States, the Marihuana Tax Act was passed, and prohibited the production of hemp in addition to cannabis. The reasons that hemp was also included in this law are disputed. Several scholars have claimed that the Act was passed in order to destroy the hemp industry,[95][96][97] largely as an effort of businessmen Andrew Mellon, Randolph Hearst, and the Du Pont family.[95][97] With the invention of the decorticator, hemp became a very cheap substitute for the paper pulp that was used in the newspaper industry.[95][98] Hearst felt that this was a threat to his extensive timber holdings. Mellon, Secretary of the Treasury and the wealthiest man in America, had invested heavily in the DuPont's new synthetic fiber, nylon, and considered its success to depend on its replacement of the traditional resource, hemp.[95][99][100][101][102][103][104][105] The claims that hemp could have been a successful substitute for wood pulp have been based on an incorrect government report of 1916 which concluded that hemp hurds, broken parts of the inner core of the hemp stem, were a suitable source for paper production. This has not been confirmed by later research, as hemp hurds are not reported to be a good enough substitute. Many advocates for hemp have greatly overestimated the proportion of useful cellulose in hemp hurds. In 2003, 95 % of the hemp hurds in EU were used for animal bedding, almost 5 % were used as building material.[106][107][108][109]

Legal status

Since the beginning of the 20th century, most countries have enacted laws against the cultivation, possession or transfer of cannabis. These laws have impacted adversely on the cannabis plant's cultivation for non-recreational purposes, but there are many regions where, under certain circumstances, handling of cannabis is legal or licensed. Many jurisdictions have lessened the penalties for possession of small quantities of cannabis, so that it is punished by confiscation and sometimes a fine, rather than imprisonment, focusing more on those who traffic the drug on the black market.

In some areas where cannabis use has been historically tolerated, some new restrictions have been put in place, such as the closing of cannabis coffee shops near the borders of the Netherlands,[110] closing of coffee shops near secondary schools in the Netherlands and crackdowns on "Pusher Street" in Christiania, Copenhagen in 2004.[111][112]

Some jurisdictions use free voluntary treatment programs and/or mandatory treatment programs for frequent known users. Simple possession can carry long prison terms in some countries, particularly in East Asia, where the sale of cannabis may lead to a sentence of life in prison or even execution. More recently however, many political parties, non-profit organizations and causes based on the legalization of medical cannabis and/or legalizing the plant entirely (with some restrictions) have emerged.

Price

The price or street value of cannabis varies strongly by region and area. In addition, some dealers may sell potent buds at a higher price.[113]

In the United States, cannabis is overall the #4 value crop, and is #1 or #2 in many states including California, New York and Florida, averaging $3,000/lb.[114][115] It is believed to generate an estimated $36 billion market.[116] Most of the money is spent not on growing and producing but on smuggling the supply to buyers. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical U.S. retail prices are $10–15 per gram (approximately $280–420 per ounce). Street prices in North America are known to range from about $150 to $400 per ounce, depending on quality.[117]

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that typical retail prices in Europe for cannabis varies from 2€ to 14€ per gram, with a majority of European countries reporting prices in the range 4–10€.[118] In the United Kingdom, a cannabis plant has an approximate street value of £300,[119] but retails to the end-user at about £160/oz.

Truth serum

Cannabis was used as a truth serum by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a US government intelligence agency formed during World War II. In the early 1940s, it was the most effective truth drug developed at the OSS labs at St. Elizabeths Hospital; it caused a subject "to be loquacious and free in his impartation of information."[120]

In May 1943, Major George Hunter White, head of OSS counter-intelligence operations in the US, arranged a meeting with Augusto Del Gracio, an enforcer for gangster Lucky Luciano. Del Gracio was given cigarettes spiked with THC concentrate from cannabis, and subsequently talked openly about Luciano's heroin operation. On a second occasion the dosage was increased such that Del Gracio passed out for two hours.[120]

Breeding and cultivation

It is often claimed by growers and breeders of herbal cannabis that advances in breeding and cultivation techniques have increased the potency of cannabis since the late 1960s and early '70s, when THC was first discovered and understood. However, potent seedless cannabis such as "Thai sticks" were already available at that time. Sinsemilla (Spanish for "without seed") is the dried, seedless inflorescences of female cannabis plants. Because THC production drops off once pollination occurs, the male plants (which produce little THC themselves) are eliminated before they shed pollen to prevent pollination. Advanced cultivation techniques such as hydroponics, cloning, high-intensity artificial lighting, and the sea of green method are frequently employed as a response (in part) to prohibition enforcement efforts that make outdoor cultivation more risky. It is often cited that the average levels of THC in cannabis sold in United States rose dramatically between the 1970s and 2000, but such statements are likely skewed because of undue weight given to much more expensive and potent, but less prevalent samples.[121] The average THC level in coffee shops in the Netherlands is currently about 18–19%, but new regulations adopted by the Dutch government in 2011 will force the THC content of cannabis sold in coffee shops to be limited to 15%, stating that cannabis in excess of 15% THC will be reclassified as a hard drug. These new regulations take effect in 2012.[122][123]

In arts and literature

See also

- Addiction Recovery

- Cannabis plant

- Cannabis legality

- Cannabis political parties

- Global Marijuana March

- Legal and medical status of cannabis

- Legal history of cannabis in the United States

- Legality of cannabis by country

- Marijuana Control, Regulation, and Education Act

- Marijuana Policy Project

- Marihuana Tax Act of 1937

- National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws

- Cannabis use demographics

Footnotes

^ a: Weed,[124] pot,[125] and herb,[126] are among the many other nicknames for marijuana or cannabis as a drug.[127]

^ b: Sources for this section and more information can be found in the Medical cannabis article

Citations

- ^ See article on Marijuana as a word.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- ^ See, Etymology of marijuana.

- ^ Company, Houghton Mifflin (2007-11-14). Spanish Word Histories and Mysteries. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 142. ISBN 0-618-91054-9, 9780618910540.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, Bhattacharyya S; et al. (2009). "Distinct effects of {delta}9-tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol on Neural Activation during Emotional Processing". Archives of General Psychiatry. 66 (1): 95–105. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.519. PMID 19124693. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rudgley, Richard (1998). Lost Civilisations of the Stone Age. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-85580-1.

- ^ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2006). Cannabis: Why We Should Care (PDF). Vol. 1. S.l.: United Nations. p. 14. ISBN 92-1-148214-3.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Cannabis: Legal Status". Erowid.org. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ^ UNODC. World Drug Report 2010. United Nations Publication. p. 198. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ^ "Marijuana and the Brain, Part II: The Tolerance Factor".

- ^ Riedel, G.; Davies, S.N. (2005). "Cannabinoid function in learning, memory and plasticity". Handb Exp Pharmacol. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 168 (168): 446. doi:10.1007/3-540-26573-2_15. ISBN 3-540-22565-X. PMID 16596784. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ "Long-Term Effects of Exposure to Cannabis". Sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ "Adverse Effects of Cannabis on Health: An Update of the Literature Since 1996". Sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16225128, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16225128instead. - ^ Stafford, Peter (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Berkeley, California, United States: Ronin Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-914171-51-8.

- ^ McKim, William A (2002). Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology (5th Edition). Prentice Hall. p. 400. ISBN 0-13-048118-1.

- ^ "Information on Drugs of Abuse". Commonly Abused Drug Chart.

- ^ "FDA: Inter-Agency Advisory Regarding Claims That Smoked Marijuana Is a Medicine". Fda.gov. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- ^ "Medical Frequently Asked Questions". NORML. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "FDA: Inter-Agency Advisory Regarding Claims That Smoked Marijuana Is a Medicine". Fda.gov. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions - Medical Marihuana". Hc-sc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17382831, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17382831instead. - ^ McLaren, Jennifer; Lemon, Jim; Robins, Lisa; Mattick, Richard P. (2008). Cannabis and Mental Health: Put into Context. National Drug Strategy Monograph Series. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Harding, Anne (3 November 2008). "Pot-induced psychosis may signal schizophrenia". Reuters. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/bmj.38267.664086.63, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/bmj.38267.664086.63instead. - ^ Simeon, Daphne (2004). "Depersonalization Disorder: A Contemporary Overview". CNS Drugs. Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- ^ "The BEACH Project". Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ "High Times in Ag Science: Marijuana More Potent Than Ever | Wired Science". Wired.com. 2008-12-22. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "Marijuana- Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com.

- ^ "Hemp Facts". Naihc.org. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "Kief | Cannabis Culture Magazine". Cannabisculture.com. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "Hashish - Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com.

- ^ "Hash Oil Info".

- ^ "Pipe Residue Information".

- ^ "ChemSpider - THC".

- ^ "ChemSpider - Cannabinol".

- ^ "Decarboxylation - Does Marijuana Have to be Heated to Become Psychoactive?".

- ^ Template:ChemID

- ^ Leo E. Hollister; et al. (March 1986). "Health aspects of cannabis". Pharma Review (38): 1–20. Archived from the original on 1986. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Wilson, R. & Nicoll, A. (2002). "Endocannabinoid signaling in the brain". Science. 296 (5568): 678–682. doi:10.1126/science.1063545. PMID 11976437.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fernandez, J. & Allison, B. (2004). "Rimbonabant Sanofi-Synthelabo". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs (5): 430–435.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Why Does Cannabis Potency Matter?". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2009-06-29.

- ^ ElSohly MA, Ross SA, Mehmedic Z, Arafat R, Yi B, Banahan BF (2000). "Potency Trends of delta9-THC and Other Cannabinoids in Confiscated Marijuana from 1980 to 1997". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 45 (1): 24–30. PMID 10641915.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olemiss.edu[dead link]

- ^ "Cannabis Potency". National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ^ "BBC: Cannabis laws to be strengthened. May 2008 20:55 UK". BBC News. 2008-05-07. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Di Forti, M; Morgan, C; Dazzan, P; Pariante, C; Mondelli, V; Marques, TR; Handley, R; Luzi, S; Russo, M. "High-potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis". British Journal of Psychiatry. 195 (6). Bjp.rcpsych.org: 488–91. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.064220. PMC 2801827. PMID 19949195. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ Hope, Christopher (2008-02-06). "Use of extra strong 'skunk' cannabis soars". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ J.E. Joy, S. J. Watson, Jr., and J.A. Benson, Jr, (1999). Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing The Science Base. Washington D.C: National Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 0-585-05800-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Electronenmicroscopisch onderzoek van vervuilde wietmonsters" (PDF).

- ^ "Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety - Contamination of herbal or 'skunk-type' cannabis with glass beads" (PDF).

- ^ "Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety - Update on seizures of cannabis contaminated with glass particles" (PDF).

- ^ Busse F, Omidi L, Timper K; et al. (2008). "Lead poisoning due to adulterated marijuana". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (15): 1641–2. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0707784. PMID 18403778.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Venhuis BJ, de Kaste D (2008). "Sildenafil analogs used for adulterating marijuana". Forensic Sci. Int. 182 (1–3): e23–4. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.09.002. PMID 18945564.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "FRANK - Cannabis". Talktofrank.com. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "UKCIA Soapbar warning - cannabis conamination - don't buy soapbar!". Ukcia.org. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "Feature - Dr Russell Newcome on the ACMD report on cannabis : 2006-02-07". Lifeline Project. 2006-02-07. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ a b R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp 1513–1518.

- ^ Coulter C, Taruc M, Tuyay J, Moore C. Quantitation of tetrahydrocannabinol in hair using immunoassay and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric detection. Drug Test. Anal. 1: 234–239, 2009.

- ^ DM Schwope, G Milman and MA Huestis. Validation of an enzyme immunoassay for detection and semiquantification of cannabinoids in oral fluid. Clin. Chem. 56: 1007–1014, 2010.

- ^ Huestis MA, Scheidweiler KB, Saito T, Fortner N, Abraham T, Gustafson RA, Smith ML (2008). "Excretion of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Sweat". Forensic Sci. Int. 174 (2–3): 173–177. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.04.002. PMC 2277330. PMID 17481836.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ AlterNet, 28 July 2010, Has the Most Common Marijuana Test Resulted in Tens of Thousands of Wrongful Convictions?

- ^ Venkatratnam, Abhishek (2011). "Zinc Reduces the Detection of Cocaine, Methamphetamine, and THC by ELISA Urine Testing". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 35 (6): 333–340. doi:10.1093/anatox/35.6.333.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "RAND study casts doubt on claims that marijuana acts as "gateway" to the use of cocaine and heroin". RAND Corporation. 2002-12-02. Archived from the original on 2006-11-04.

- ^ Lundin, Leigh (2009-03-01). "The Great Smoke-Out". Criminal Brief.

- ^ a b Torabi MR, Bailey WJ, Majd-Jabbari M (1993). "Cigarette Smoking as a Predictor of Alcohol and Other Drug Use by Children and Adolescents: Evidence of the "Gateway Drug Effect"". The Journal of School Health. 63 (7): 302–306. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb06150.x. PMID 8246462.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Australian Government Department of Health: National Cannabis Strategy Consultation Paper, p. 4. "Cannabis has been described as a 'Trojan Horse' for nicotine addiction, given the usual method of mixing Cannabis with tobacco when preparing marijuana for administration."

- ^ Hall WD, Lynskey M (2005). "Is Cannabis A Gateway Drug? Testing Hypotheses About the Relationship Between Cannabis Use and the Use of Other Illicit Drugs". Drug and Alcohol Review. 24 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1080/09595230500126698. PMID 16191720.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Saitz, Richard (2003-02-18). "Is marijuana a gateway drug?". Journal Watch. 2003 (218): 1.

- ^ Degenhardt, Louisa; et al. (2007). "Who are the new amphetamine users? A 10-year prospective study of young Australians".

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Paddock SM (2002). "Reassessing the marijuana gateway effect". Addiction. 97 (12): 1493–504. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00280.x. PMID 12472629.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Marijuana Policy Project- FAQ". Archived from the original on 2008-06-22.

- ^ "Risk of marijuana's 'gateway effect' overblown, new research shows". Sciencedaily.com. 2010-09-02. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Stafford, Peter (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Berkeley, CA, USA: Ronin Publishing. ISBN 0-914171-51-8.

- ^ Matthews, A; Matthews, L (2007). Learning Chinese Characters. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-8048-3816-0.

- ^ "Marijuana and the Cannabinoids", ElSohly (p. 8).

- ^ "Lab work to identify 2,800-year-old mummy of shaman". People's Daily Online. 2006.

- ^ Hong-En Jiang; et al. (2006). "A new insight into Cannabis sativa (Cannabaceae) utilization from 2500-year-old Yanghai tombs, Xinjiang, China". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 108 (3): 414–22. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.05.034. PMID 16879937.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Leary, Thimothy (1990). Tarcher & Putnam (ed.). Flashbacks. New York: GP Putnam's Sons. ISBN 0-87477-870-0.

- ^ Miller, Ga (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 34 (11th ed.). pp. 761–2. doi:10.1126/science.34.883.761. PMID 17759460.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Rudgley, Richard (1998). Little, Brown; et al. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances. ISBN 0-349-11127-8.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) - ^ Franck, Mel (1997). Marijuana Grower's Guide. Red Eye Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-929349-03-2.

- ^ Rubin, Vera D (1976). Cannabis and Culture. Campus Verlag. p. 305. ISBN 3-593-37442-0.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry W (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 405. ISBN 0-19-285441-0.

- ^ Walton, Robert P (1938). Marijuana, America's New Drug Problem. JB Lippincott. p. 6.

- ^ Matthew J. Atha (Independent Drug Monitoring Unit). "Types of Cannabis Available in the United Kingdom (UK)".

- ^ "Cannabis linked to Biblical healing". News. BBC. 2003-01-06. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ^ Ibn Taymiyya (2001). Le haschich et l'extase (in French). Beyrouth: Albouraq. ISBN 2-84161-174-4.

- ^ "Bard 'used drugs for inspiration'". BBC News. BBC. 2001-03-01. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Drugs clue to Shakespeare's genius". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. 2001-03-01. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Statement of Dr. William C. Woodward". Drug library. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ "Debunking the Hemp Conspiracy Theory".

- ^ W. W. Willoughby (1925). "Opium as an international problem". Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Opium as an international problem: the Geneva conferences – Westel Woodbury Willoughby at Google Books

- ^ a b c d French, Laurence; Manzanárez, Magdaleno (2004). NAFTA & neocolonialism: comparative criminal, human & social justice. University Press of America. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7618-2890-7.

- ^ Earlywine, 2005: p. 24

- ^ a b Peet, 2004: p. 55

- ^ Sterling Evans (2007). Bound in twine: the history and ecology of the henequen-wheat complex for Mexico and the American and Canadian Plains, 1880–1950. Texas A&M University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-58544-596-7.

- ^ Evans, Sterling, ed. (2006). The borderlands of the American and Canadian Wests: essays on regional history of the forty-ninth parallel. University of Nebraska Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-8032-1826-0.

- ^ Gerber, Rudolph Joseph (2004). Legalizing marijuana: drug policy reform and prohibition politics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-275-97448-0.

- ^ Earleywine, Mitchell (2005). Understanding marijuana: a new look at the scientific evidence. Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-19-518295-8.

- ^ Robinson, Matthew B & Scherlen, Renee G (2007). Lies, damned lies, and drug war statistics: a critical analysis of claims made by the office of National Drug Control Policy. SUNY Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7914-6975-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rowe, Thomas C (2006). Federal narcotics laws and the war on drugs: money down a rat hole. Psychology Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7890-2808-2.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Law Enforcement: Federal. SAGE. 2005. p. 747. ISBN 978-0-7619-2649-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Lusane, Clarence (1991). Pipe dream blues: racism and the war on drugs. South End Press. pp. 37–8. ISBN 978-0-89608-410-0.

- ^ Lyster H. Dewey and Jason L. Merrill Hemp Hurds as Paper-Making Material USDA Bulletin No. 404, Washington, DC, October 14, 1916, p. 25.

- ^ "Hayo MG van der Werf: Hemp facts and hemp fiction". Hempfood.com. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ^ "Dr. Ivan BÛcsa, GATE Agricultural Research Institute, Kompolt — Hungary, Book Review Re-discovery of the Crop Plant Cannabis Marihuana Hemp (Die Wiederentdeckung der Nutzplanze Cannabis Marihuana Hanf)". Hempfood.com. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ^ Michael Karus: European Hemp Industry 2002 Cultivation, Processing and Product Lines. Journal of Industrial Hemp Volume 9 Issue 2 2004, Taylor & Francis, London.

- ^ "Many Dutch coffee shops close as liberal policies change, Exaptica". Expatica.com. 2007-11-27. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ EMCDDA Cannabis reader: Global issues and local experiences, Perspectives on Cannabis controversies, treatment and regulation in Europe, 2008, p. 157.

- ^ "43 Amsterdam coffee shops to close door", Radio Netherlands, Friday 21 November 2008[dead link]

- ^ "UNODC.org" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ "Report on U.S. Domestic Marijuana Production". NORML. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "Marijuana Crop Reports". NORML. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ^ "Marijuana Called Top U.S. Cash Crop". 2008 ABCNews Internet Ventures.

- ^ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2008). World drug report (PDF). United Nations Publications. p. 264. ISBN 978-92-1-148229-4.

- ^ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2008). Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe (PDF). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 38. ISBN 978-92-9168-324-6.

- ^ Dearne Safer Neighbourhood Team (SNT) recovers cannabis with a street value of approximately £9,000

- ^ a b Cockburn, Alexander (1998). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. Verso. pp. 117–118. ISBN 1-85984-139-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Daniel Forbes (November 19, 2002). "The Myth of Potent Pot". Slate.com.

- ^ "World Drug Report 2006". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Ch. 2.3.

- ^ "Dutch to reclassify high-strength cannabis". BBC News. 2011-10-07.

- ^ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/weed

- ^ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pot

- ^ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/herb

- ^ "Marijuana Dictionary".

Further reading

- Booth, Martin (2005). Cannabis: A History. Macmillan Publishers & Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-0-312-42494-7.

- Deitch, Robert (2003). Hemp: American history revisited: the plant with a divided history. Algora Pub. ISBN 0-87586-206-3Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Earleywine, Mitchell (2005). Understanding marijuana: a new look at the scientific evidence. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513893-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Emmett, David (2009). What you need to know about cannabis: understanding the facts. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 1-84310-697-3Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Geoffrey William, Guy (2004). The medicinal uses of cannabis and cannabinoids. Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 0-85369-517-2Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Holland, Julie M.D. (2010). The pot book : a complete guide to cannabis : its role in medicine, politics, science, and culture. Park Street Press. ISBN 978-1-59477-368-6Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Iversen, Leslie L (2008). The science of marijuana (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532824-0Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Jenkins, Richard (2006). Cannabis and young people: reviewing the evidence. Jessica Kingsley. ISBN 1-84310-398-2Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lambert, Didier M (2008). Cannabinoids in Nature and Medicine. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-906390-56-XTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Roffman, Roger A (2006). Cannabis dependence: its nature, consequences, and treatment. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81447-2Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Russo, Ethan (2004). Women and cannabis: medicine, science, and sociology. Haworth Press. ISBN 0-7890-2101-3Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Solowij, Nadia (1998). Cannabis and cognitive functioning. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59114-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link)

External links

![]() Media related to Cannabis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cannabis at Wikimedia Commons

- Wiktionary Appendix of Cannabis Slang

- Montana PBS documentary,Clearing the Smoke

- Erowid Cannabis (Marijuana) Vault

- Reefer Madness! - slideshow by Life magazine

- "Cannabis: a health perspective and research agenda", Programme on Substance Abuse, World Health Organization, 1997

- "Endocannabinoids Inhibit Transmission at Granule Cell to Purkinje Cell Synapses by Modulating Three Types of Presynaptic Calcium Channels"