Koyilandy

Koyilandy

Quilandy | |

|---|---|

Municipality Taluk | |

Kadaloor Point lighthouse, Koyilandy | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Coordinates: 11°26′20″N 75°41′42″E / 11.439°N 75.695°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Kerala |

| Region | North Malabar |

| District | Kozhikode |

| Area | |

• Total | 29 km2 (11 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 20 |

| Elevation | 2 m (7 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

• Total | 71,873 |

| • Rank | 20 th |

| Demonym | Koyilandikaran |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Malayalam, English |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 673305 |

| Telephone code | 0496 |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-KL |

| Vehicle registration | KL 56 |

| Website | www |

Koyilandy (IPA: [kojilɐːɳɖi]; formerly known in English as Quilandy, Malayalam as Pandalayani Kollam, Arabic as Fundriya, and Portuguese as Pandarani)[2][1][3] is a municipality and a taluk in Kozhikode district, Kerala on the Malabar Coast. The historical town is located right in the middle of the coast of Kozhikode district, between Kozhikode (Calicut) and Kannur, on National Highway 66.

The freedom fighter K. Kelappan, popularly known as Kerala Gandhi, was born in a nearby village, Muchukunnu.[4]

Etymology

Pandalayani is described by different authors, all the way from Europe to Arabia to China, in different names. Some of the names are given here. Pliny the Elder describes the place as Patale.[2] The Odoric of Pordenone called Pandalayani as Flandarina.[2] The medieval Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta called it Fandaraina.[2] The Portuguese writers called Pandalayani as Pandarani.[2] The medieval historic chronicle Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen written by the Zainuddin Makhdoom II of Ponnani calls the port town as Fundreeah.[2]

History

"No one has tried to clear that misconception [that Vasco da Gama landed at Kappad]. The government has even installed a memorial stone at the Kappad beach. Actually [Vasco da] Gama landed at Koyilandy in the [Kozhikode] district because there was a port there and Kozhikode did not have one. It does not have a port even now."[5]

Ancient era

Koyilandy, formerly known as Panthalayani Kollam, is one of the oldest ports in South India and is often identified with the port of Tyndis by some of the historians, which was a satellite feeding port to Muziris, according to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.[1] Tyndis was a major center of trade, next only to Muziris, between the Cheras and the Roman Empire.[6] Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) states that the port of Tyndis was located at the northwestern border of Keprobotos (Chera dynasty).[7] The North Malabar region, which lies north of the port at Tyndis, was ruled by the kingdom of Ezhimala during Sangam period.[1] According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a region known as Limyrike began at Naura and Tyndis. However the Ptolemy mentions only Tyndis as the Limyrike's starting point. The region probably ended at Kanyakumari; it thus roughly corresponds to the present-day Malabar Coast. The value of Rome's annual trade with the region was estimated at around 50,000,000 sesterces.[8] Pliny the Elder mentioned that Limyrike was prone by pirates.[9] The Cosmas Indicopleustes mentioned that the Limyrike was a source of peppers.[10][11] The medieval Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta describes Pandalayani Kollam as "A beautiful and large place, abounding with gardens and markets".[2]

Early Middle Ages

According to Kerala Muslim tradition, Koyilandy was home to one of the oldest mosques in the Indian subcontinent. According to the Legend of Cheraman Perumals, the first Indian mosque was built in 624 AD at Kodungallur with the mandate of the last the ruler (the Cheraman Perumal) of Chera dynasty, who left from Dharmadom to Mecca and converted to Islam during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad (c. 570–632).[12][13][14][15] According to the legend, the Masjid at Pandalayani (Koyilandy) was built by Malik Dinar, and he appointed one of his ten sons as the Quazi in the Masjid.[2] According to Qissat Shakarwati Farmad, the Masjids at Kodungallur, Kollam, Madayi, Barkur, Mangalore, Kasaragod, Kannur, Dharmadam, Panthalayani (Koyilandy), and Chaliyam, were built during the era of Malik Dinar, and they are among the oldest Masjids in the Indian subcontinent.[16] It is believed that Malik Dinar died at Thalangara in Kasaragod town.[17] The Koyilandy Jumu'ah Mosque contains an Old Malayalam inscription written in a mixture of Vatteluttu and Grantha scripts which dates back to the 10th century CE.[18] It is a rare surviving document recording patronage by a Hindu king (Bhaskara Ravi) to the Muslims of Kerala.[18] Several Old Malayalam inscriptions, those date back to the 11th century CE, have found from Pandalayani Kollam.[19]

Portuguese era

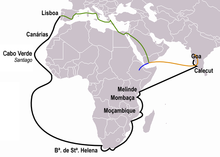

Initially, Koyilandy was an important port town of Kolathunadu (Kingdom of Kannur) in the early medieval period. Later the Zamorin of Calicut annexed the port town to establish supremacy over the North Malabar region.[1] The Kollam Raja of Payanad had made his capital at Pandalayani Kollam and the Zamorin, his conquerrer, had a palace here.[2] The few remnants of the Chinese trade can be seen in and around the present city of Koyilandy. This include a Silk Street, Chinese Fort ("Chinakotta"), Chinese Settlement ("Chinachery" in Kappad), and Chinese Mosque ("Chinapalli" in Koyilandy).[20][21][22] The Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama visited Koyilandy in 1498, opening the sailing route directly from Europe to South Asia, during the Age of Discovery.[23] It eventually led to the European colonisation of Indian subcontinent.[1] In March 1505, a large Muslim fleet at Koyilandy was destroyed by Portuguese. It had assembled there to take back a large number of Muslims to Arabia and Egypt, who were leaving the kingdom of Calicut disappointed at the trade losses caused to them recently. Duarte de Menezes captured 17 vessels and killed 2,000 men.[24][25]

In February–March 1525, A Portuguese navy led by new Viceroy Henry Menezes raided Ponnani and Koyilandy, and burned both of the towns.[25] Koyilandy was defended by a combined army of 20,000 Nairs and Muslims.[25] On reaching Calicut, he earlier found that the place had been attacked by the Calicut forces.[25] The Nairs of the chief of Kurumbranad and Calicut forces invested Fort Calicut (Siege of Calicut).[25][26] They were helped by a band of Muslims under the command of a European engineer.[26] The Kutti Ali's (Kunjali Marakkar) ships blockaded the port. Captain Lima, with 300 men, defended the fort.[26] In 1550, the Portuguese made descents on the coastal towns of Calicut, particularly on Koyilandy, destroying mosques and houses, and killing one-third of the inhabitants.[25] According to historian M. G. Raghava Varier, at the peak of their reign, the Zamorin of Calicut ruled over a region from Kollam in south to Koyilandy in north.[27][28][29]

Location

Koyilandy is located at 11°26′N 75°42′E / 11.43°N 75.70°E[30] at an average elevation of 2 m (6.6 ft).

Demographics

As of 2011 India census,[31] Koyilandy had a population of 71,873. Males constitute 46.78% of the population and females 53.22%. Literacy rate of Koyilandy is 95.11% (higher than Kerala average of 94.00%). Male literacy is around 97.38% while female literacy rate is 93.15%. In Koyilandy, around 10% of the population is under 6 years of age.[3] Economy of Koyilandy revolves around fishing, local businesses and remittance from the Persian Gulf. Around 70% of population follows Hinduism, and around 30% follows Islam in Koyilandy.[3]

Koyilandy taluk

Koyilandy is the largest Taluk in Kozhikode district.[32][33] It administers a population of 645,979 within an area of 642 square kilometre, as of the Census 2011.[32][33] The position of the Koyilandy Taluk in Kozhikode district is given below:

Koyilandy is the taluk headquarters of 34 Revenue Villages. They are Arikkulam, Atholy, Avitanallur, Balussery, Chakkittapara, Changaroth, Chemancheri, Chempanode, Chengottukavu, Cheruvannur, Eravattur, Iringal, Kayanna, Keezhariyur, Koorachundu, Koothali, Kottur, Kozhukkallur, Menhaniam, Meppayur, Moodadi, Naduvannur, Nochad, Palery, Panangad, Panthalayani, Payyoli, Perambra, Sivapuram, Thikkodi, Thurayur, Ulliyeri, Unnikulam, Uralloor, Viyyur and Muchukunnu.[33]

Koyilandy Cuisine

Koyilandy has a wide variety of indigenous dishes. The centuries of maritime trade has given the Koyilandy a cosmopolitan cuisine. The cuisine is a blend of traditional Kerala, Persian, Yemenese and Arab food culture.[34] One of the main elements of this cuisine is Pathiri, a pancake made of rice flour. Variants of Pathiri include Neypathiri (made with ghee), Poricha Pathiri (fried rather than baked), Meen Pathiri (stuffed with fish), and Irachi Pathiri (stuffed with beef). Spices like Black pepper, Cardamom, and Clove are widely used in the cuisine of Koyilandy. The main item used in the festivals is the Malabar style of Biryani. Sadhya is also seen in marriage and festival occasions. Snacks such as Arikadukka, Chattipathiri, Muttamala, Pazham Nirachathu, and Unnakkaya have their own style in Koyilandy. Besides these, other common food items of Kerala are also seen in the cuisine of Koyilandy.[35] The Malabar version of Biryani, popularly known as Kuzhi Mandi in Malayalam is another popular item, which has an influence from Yemen.[34]

Wards of Koyilandy

The town is administered by Koyilandy Municipality, headed by a chairperson. For administrative purposes, the town is divided into 44 wards,[36] from which the members of the municipal council are elected for a term of five years.

The wards are:[37]

| Ward no. | Name | Ward no. | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pathirikkad | 2 | Maraloor |

| 3 | Kodakkattu Muri | 4 | Perunkuni |

| 5 | Puliyanchery | 6 | Attavayal |

| 7 | Puliyanchery East | 8 | Kalathil Kadavu |

| 9 | Viyyur | 10 | Pavuvayal |

| 11 | Panthalayani North | 12 | Puthalath Kunnu |

| 13 | Peruvattur | 14 | Panthalayani Central |

| 15 | Panthalayani South | 16 | Peruvattur Central |

| 17 | Kakrattu Kunnu | 18 | Aruvayal |

| 19 | Anela | 20 | Muthambi |

| 21 | Thetti Kunnu | 22 | Kavum Vattam |

| 23 | Moozhikk Meethal | 24 | Marathoor |

| 25 | Anela-Kuruvangad | 26 | Kanayankode |

| 27 | Varakunnu | 28 | Kuruvangad |

| 29 | Manamal | 30 | Komathukara |

| 31 | Kothamangalam | 32 | Nadelakandi |

| 33 | Korayangad | 34 | Chalil Parambu |

| 35 | Cheriyamangad | 36 | Virunnu Kandi |

| 37 | Koyilandy South | 38 | Thazhangadi |

| 39 | Koyilandy Town | 40 | Kasmikandi |

| 41 | Civil Station | 42 | Ooraam Kunnu |

| 43 | Kollam West | 44 | Kaniyamkunnu |

Elected representatives

- MP - K. Muraleedharan (Indian National Congress-UDF)

- MLA - Kanathil Jameela (CPIM-LDF)

- Koyilandy municipal Chairman-

See also

- Koyilandy (State Assembly constituency)

- Kolathunadu

- Zamorin

- Kunjali Marakkar

- Calicut

- Kannur

- Thalassery

- Vadakara

- Ponnani

- Cochin

- Puttad

- North Malabar

- Korapuzha

References

- ^ a b c d e f A Survey of Kerala History, A. Shreedhara Menon

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Charles Alexander Innes (1908). Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-I). Madras Government Press. pp. 464–465.

- ^ a b c India Census 2011

- ^ "Kelappan. K | Kerala Press Academy". Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ^ "Vasco da Gama never landed at Kappad: M G S" [1] The Hindu FEBRUARY 06, 2017

- ^ Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India, Yogesh Sharma, Primus Books 2010

- ^ Gurukkal, R., & Whittaker, D. (2001). In search of Muziris. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 14, 334-350.

- ^ According to Pliny the Elder, goods from India were sold in the Empire at 100 times their original purchase price. See [2]

- ^ Bostock, John (1855). "26 (Voyages to India)". Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). Christian Topography. 11. United Kingdom: The Tertullian Project. pp. 358–373.

- ^ Das, Santosh Kumar (2006). The Economic History of Ancient India. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 301.

- ^ Jonathan Goldstein (1999). The Jews of China. M. E. Sharpe. p. 123. ISBN 9780765601049.

- ^ Edward Simpson; Kai Kresse (2008). Struggling with History: Islam and Cosmopolitanism in the Western Indian Ocean. Columbia University Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-231-70024-5. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Uri M. Kupferschmidt (1987). The Supreme Muslim Council: Islam Under the British Mandate for Palestine. Brill. pp. 458–459. ISBN 978-90-04-07929-8. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Husain Raṇṭattāṇi (2007). Mappila Muslims: A Study on Society and Anti Colonial Struggles. Other Books. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-81-903887-8-8. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Prange, Sebastian R. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press, 2018. 98.

- ^ Pg 58, Cultural heritage of Kerala: an introduction, A. Sreedhara Menon, East-West Publications, 1978

- ^ a b Aiyer, K. V. Subrahmanya (ed.), South Indian Inscriptions. VIII, no. 162, Madras: Govt of India, Central Publication Branch, Calcutta, 1932. p. 69.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 475-76.

- ^ Subairath C.T. "CALICUT: A CENTRI-PETAL FORCE IN THE CHINESE AND ARAB TRADE (1200–1500)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol. 72, PART-II (2011), pp. 1082-1089

- ^ Michael Keevak. Embassies to China: Diplomacy and Cultural Encounters Before the Opium Wars. Springer (2017)

- ^ Das Gupta, A., 1967. Malabar in Asian Trade: 1740-1800. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- ^ Eila M.J. Campbell, Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, "Vasco da Gama." Encyclopædia Britannica Online [3]

- ^ Robert Swell. "A Forgotten Empire: Vijayanagar"., Book 1, Chapter 10.

- ^ a b c d e f William Logan (1887). Malabar Manual (Volume-I). Madras Government Press.

- ^ a b c K. K. N. Kurup, ed., India's Naval Traditions. Northern Book Centre, New Delhi, 1997

- ^ Varier, M. R. Raghava. "Documents of Investiture Ceremonies" in K. K. N. Kurup, Edit., "India's Naval Traditions". Northern Book Centre, New Delhi, 1997

- ^ Sanjay Subrahmanyam. "The Political Economy of Commerce: Southern India 1500–1650". Cambridge University Press, 2002

- ^ V. V., Haridas. "King court and culture in medieval Kerala – The Zamorins of Calicut (AD 1200 to AD 1767)". [4] Unpublished PhD Thesis. Mangalore University

- ^ Falling Rain Genomics, Inc - Koyilandy

- ^ "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Taluk-wise demography of Kozhikode" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala. pp. 161–193. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Villages in Kozhikode". kozhikode.nic.in. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ a b Sabhnani, Dhara Vora (14 June 2019). "Straight from the Malabar Coast". The Hindu. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Cuisine of Malappuram". malappuramtourism.org. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Koyilandy municipality". lsgkerala.

- ^ "Wards of Koyilandy". sec.kerala.gov.in.