Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christianity (from the Greek word Xριστός, Khristos, "Christ", literally "anointed one") is a monotheistic religion[1] based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as presented in the New Testament.[2] Christianity comprises three major branches: Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy (which parted ways with Catholicism in 1054 A.D.) and Protestantism (which came into existence during the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century).[3] Protestantism is further divided into smaller groups called denominations.

Christians believe Jesus is the son of God, God having become man and the savior of humanity. Christians, therefore, commonly refer to Jesus as Christ or Messiah.[4]

Adherents of the Christian faith, known as Christians,[5] believe that Jesus is the Messiah prophesied in the Hebrew Bible (the part of scripture common to Christianity and Judaism, and referred to as the "Old Testament" in Christianity). The foundation of Christian theology is expressed in the early Christian ecumenical creeds, which contain claims predominantly accepted by followers of the Christian faith.[6] These professions state that Jesus suffered, died from crucifixion, was buried, and was resurrected from the dead to open heaven to those who believe in him and trust him for the remission of their sins (salvation).[7] They further maintain that Jesus bodily ascended into heaven where he rules and reigns with God the Father. Most denominations teach that Jesus will return to judge all humans, living and dead, and grant eternal life to his followers. He is considered the model of a virtuous life, and both the revealer and physical incarnation of God.[8] Christians call the message of Jesus Christ the Gospel ("good news") and hence refer to the earliest written accounts of his ministry as gospels.

Christianity began as a Jewish sect[9][10] and is classified as an Abrahamic religion.[11][12][13] Originating in the eastern Mediterranean, it quickly grew in size and influence over a few decades, and by the 4th century had become the dominant religion within the Roman Empire.[14]

During the Middle Ages, most of the remainder of Europe was Christianized, with Christians also being a (sometimes large) religious minority in the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of India.[15] Following the Age of Discovery, through missionary work and colonization, Christianity spread to the Americas, Australasia, and the rest of the world. Christianity, therefore, is a major influence in the shaping of Western civilization.

As of the early 21st century, Christianity has around 2.2 billion adherents.[16][17][18] Christianity represents about a quarter to a third of the world's population and is the world's largest religion.[19] In addition, Christianity is the state religion of several countries.[20]

Beliefs

Though there are many important differences of interpretation and opinion of the Bible on which Christianity is based, Christians share a set of beliefs that they hold as essential to their faith.[21]

Creeds

Creeds (from Latin credo meaning "I believe") are concise doctrinal statements or confessions, usually of religious beliefs. They began as baptismal formulae and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries to become statements of faith.

The Apostles' Creed (Symbolum Apostolorum) was developed between the 2nd and 9th centuries. It is the most popular creed used in worship by Western Christians. Its central doctrines are those of the Trinity and God the Creator. Each of the doctrines found in this creed can be traced to statements current in the apostolic period. The creed was apparently used as a summary of Christian doctrine for baptismal candidates in the churches of Rome.[22] Since the Apostles Creed is still unaffected by the later Christological divisions, its statement of the articles of Christian faith remain largely acceptable to most Christian denominations:

- belief in God the Father, Jesus Christ as the Son of God and the Holy Spirit

- the death, descent into hell, resurrection, and ascension of Christ

- the holiness of the Church and the communion of saints

- Christ's second coming, the Day of Judgement and salvation of the faithful.

The Nicene Creed, largely a response to Arianism, was formulated at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381 respectively[23][24] and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the First Council of Ephesus in 431.[25]

The Chalcedonian Creed, developed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451,[26] though rejected by the Oriental Orthodox Churches,[27] taught Christ "to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably": one divine and one human, and that both natures are perfect but are nevertheless perfectly united into one person.[28]

The Athanasian Creed, received in the western Church as having the same status as the Nicene and Chalcedonian, says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the Substance."[29]

Most Christians (Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox and Protestants alike) accept the use of creeds, and subscribe to at least one of the creeds mentioned above.[30]

Many evangelical Protestants reject creeds as definitive statements of faith, even while agreeing with some creeds' substance. The Baptists have been non-creedal “in that they have not sought to establish binding authoritative confessions of faith on one another.” [31]: p.111 Also rejecting creeds are groups with roots in the Restoration Movement, such as the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and the Churches of Christ.[32][33]: 14–15 [34]: 123

Jesus Christ

The central tenet of Christianity is the belief in Jesus as the Son of God and the Messiah (Christ). The title "Messiah" comes from the Hebrew word מָשִׁיחַ (māšiáħ) meaning anointed one. The Greek translation

[Χριστός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Christos) is the source of the English word "Christ".[8]

Christians believe that Jesus, as the Messiah, was anointed by God as savior of humanity, and hold that Jesus' coming was the fulfillment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. The Christian concept of the Messiah differs significantly from the contemporary Jewish concept. The core Christian belief is that through belief in and acceptance of the death and resurrection of Jesus, sinful humans can be reconciled to God and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life.[35]

While there have been many theological disputes over the nature of Jesus over the earliest centuries of Christian history, Christians generally believe that Jesus is God incarnate and "true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Jesus, having become fully human, suffered the pains and temptations of a mortal man, but did not sin. As fully God, he rose to life again. According to the Bible, "God raised him from the dead,"[36] he ascended to heaven, is "seated at the right hand of the Father"[37] and will ultimately returnActs 1:9–11 to fulfill the rest of Messianic prophecy such as the Resurrection of the dead, the Last Judgment and final establishment of the Kingdom of God.

According to the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit and born from the Virgin Mary. Little of Jesus' childhood is recorded in the canonical Gospels, however infancy Gospels were popular in antiquity. In comparison, his adulthood, especially the week before his death, are well documented in the Gospels contained within the New Testament. The Biblical accounts of Jesus' ministry include: his baptism, miracles, preaching, teaching, and deeds.

Death and resurrection of Jesus

Christians consider the resurrection of Jesus to be the cornerstone of their faith (see 1 Corinthians 15) and the most important event in human history.[38] Among Christian beliefs, the death and resurrection of Jesus are two core events on which much of Christian doctrine and theology is based.[39][40] According to the New Testament Jesus was crucified, died a physical death, was buried within a tomb, and rose from the dead three days later.Jn. 19:30–31 Mk. 16:1 16:6 The New Testament mentions several resurrection appearances of Jesus on different occasions to his twelve apostles and disciples, including "more than five hundred brethren at once,"cor. 15:6 1Cor 15:6 before Jesus' Ascension to heaven. Jesus' death and resurrection are commemorated by Christians in all worship services, with special emphasis during Holy Week which includes Good Friday and Easter Sunday.

The death and resurrection of Jesus are usually considered the most important events in Christian Theology, partly because they demonstrate that Jesus has power over life and death and therefore has the authority and power to give people eternal life.[41]

Christian churches accept and teach the New Testament account of the resurrection of Jesus with very few exceptions.[42] Some modern scholars use the belief of Jesus' followers in the resurrection as a point of departure for establishing the continuity of the historical Jesus and the proclamation of the early church.[43] Some liberal Christians do not accept a literal bodily resurrection,[44][45] seeing the story as richly symbolic and spiritually nourishing myth. Arguments over death and resurrection claims occur at many religious debates and interfaith dialogues.[46] Paul the Apostle, an early Christian convert and missionary, wrote, "If Christ was not raised, then all our preaching is useless, and your trust in God is useless."1 Cor. 15:14 [47]

Salvation

Paul of Tarsus, like Jews and Roman pagans of his time, believed that sacrifice can bring about new kinship ties, purity, and eternal life.[48] For Paul the necessary sacrifice was the death of Jesus: Gentiles who are "Christ's" are, like Israel, descendants of Abraham and "heirs according to the promise".Gal. 3:29 [49] The God who raised Jesus from the dead would also give new life to the "mortal bodies" of Gentile Christians, who had become with Israel the "children of God" and were therefore no longer "in the flesh".Rom. 8:9,11,16 [48]

Modern Christian churches tend to be much more concerned with how humanity can be saved from a universal condition of sin and death than the question of how both Jews and Gentiles can be in God's family. According to both Catholic and Protestant doctrine, salvation comes by Jesus' substitutionary death and resurrection. The Catholic Church teaches that salvation does not occur without faithfulness on the part of Christians; converts must live in accordance with principles of love and ordinarily must be baptized.[50][51] Martin Luther taught that baptism was necessary for salvation, but modern Lutherans and other Protestants tend to teach that salvation is a gift that comes to an individual by God's grace, sometimes defined as "unmerited favor", even apart from baptism.

Christians differ in their views on the extent to which individuals' salvation is pre-ordained by God. Reformed theology places distinctive emphasis on grace by teaching that individuals are completely incapable of self-redemption, but that sanctifying grace is irresistible.[52] In contrast Arminians, Catholics, and Orthodox Christians believe that the exercise of free will is necessary to have faith in Jesus.[53]

Trinity

Trinity refers to the teaching that the one God comprises three distinct, eternally co-existing persons; the Father, the Son (incarnate in Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit. Together, these three persons are sometimes called the Godhead,[54][55][56] although there is no single term in use in Scripture to denote the unified Godhead.[57] In the words of the Athanasian Creed, an early statement of Christian belief, "the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, and yet there are not three Gods but one God".[58] They are distinct from another: the Father has no source, the Son is begotten of the Father, and the Spirit proceeds from the Father. Though distinct, the three persons cannot be divided from one another in being or in operation.[59]

The Trinity is an essential doctrine of mainstream Christianity. "Father, Son and Holy Spirit" represents both the immanence and transcendence of God. God is believed to be infinite and God's presence may be perceived through the actions of Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit.[60]

According to this doctrine, God is not divided in the sense that each person has a third of the whole; rather, each person is considered to be fully God (see Perichoresis). The distinction lies in their relations, the Father being unbegotten; the Son being begotten of the Father; and the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and (in Western theology) from the Son. Regardless of this apparent difference, the three 'persons' are each eternal and omnipotent.

The word trias, from which trinity is derived, is first seen in the works of Theophilus of Antioch. He wrote of "the Trinity of God (the Father), His Word (the Son) and His Wisdom (Holy Spirit)".[61] The term may have been in use before this time. Afterwards it appears in Tertullian.[62][63] In the following century the word was in general use. It is found in many passages of Origen.[64]

Trinitarians

Trinitarianism denotes those Christians who believe in the concept of the Trinity. Almost all Christian denominations and Churches hold Trinitarian beliefs. Although the words "Trinity" and "Triune" do not appear in the Bible, theologians beginning in the 3rd century developed the term and concept to facilitate comprehension of the New Testament teachings of God as Father, God as Jesus the Son, and God as the Holy Spirit. Since that time, Christian theologians have been careful to emphasize that Trinity does not imply three gods, nor that each member of the Trinity is one-third of an infinite God; Trinity is defined as one God in three Persons.[65]

Non-trinitarians

Nontrinitarianism refers to beliefs systems that reject the doctrine of the Trinity. They are a small minority of Christians. Various nontrinitarian views, such as adoptionism or modalism, existed in early Christianity, leading to the disputes about Christology.[66] Nontrinitarianism later appeared again in the Gnosticism of the Cathars in the 11th through 13th centuries, in the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th century, and in some groups arising during the Second Great Awakening of the 19th century.

Scriptures

Christianity regards the Bible, a collection of canonical books in two parts (the Old Testament and the New Testament), as the authoritative word of God. It is believed by Christians to have been written by human authors under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, and therefore for many it is held to be the inerrant word of God.[67][68][69] Jews, Catholics, Orthodox and Protestants each define separate lists of Books of the Bible that each considers canonical. These variations are a reflection of the range of traditions and councils that have convened on the subject. Every version of the complete Bible always includes books of the Jewish scriptures, the Tanakh, and includes additional books and reorganizes them into two parts: the books of the Old Testament primarily sourced from the Tanakh (with some variations), and the 27 books of the New Testament containing books originally written primarily in Greek.[70] The Roman Catholic and Orthodox canons include other books from the Septuagint which Roman Catholics call Deuterocanonical.[71] Protestants consider these books to be apocryphal. Some versions of the Christian Bible have a separate Apocrypha section for the books not considered canonical by some Churches or by the groups publishing them.[72]

Catholic and Orthodox interpretations

In antiquity, two schools of exegesis developed in Alexandria and Antioch. Alexandrine interpretation, exemplified by Origen, tended to read Scripture allegorically, while Antiochene interpretation adhered to the literal sense, holding that other meanings (called theoria) could only be accepted if based on the literal meaning.[73]

Catholic theology distinguishes two senses of scripture: the literal and the spiritual.[74]

The literal sense of understanding scripture is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture. The spiritual sense is further subdivided into:

- the allegorical sense, which includes typology. An example would be the parting of the Red Sea being understood as a "type" (sign) of baptism.1 Cor. 10:2

- the moral sense, which understands the scripture to contain some ethical teaching.

- the anagogical sense, which applies to eschatology, eternity and the consummation of the world

Regarding exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation, Catholic theology holds:

- the injunction that all other senses of sacred scripture are based on the literal[75][76]

- that the historicity of the Gospels must be absolutely and constantly held[77]

- that scripture must be read within the "living Tradition of the whole Church"[78] and

- that "the task of interpretation has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome".[79]

Protestant interpretation

- Clarity of Scripture

- Protestant Christians believe that the Bible is a self-sufficient revelation, the final authority on all Christian doctrine, and revealed all truth necessary for salvation. This concept is known as sola scriptura.[80] Protestants characteristically believe that ordinary believers may reach an adequate understanding of Scripture because Scripture itself is clear (or "perspicuous"), because of the help of the Holy Spirit, or both. Martin Luther believed that without God's help Scripture would be "enveloped in darkness."[81] He advocated "one definite and simple understanding of Scripture."[81] John Calvin wrote, "all who...follow the Holy Spirit as their guide, find in the Scripture a clear light."[82] The Second Helvetic (Latin for "Swiss")[83] Confession, composed by the pastor of the Reformed church in Zurich (successor to Protestant reformer Zwingli) was adopted as a declaration of doctrine by most European Reformed churches.[84]

- Original intended meaning of Scripture

- Protestants stress the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture, the historical-grammatical method.[85] The historical-grammatical method or grammatico-historical method is an effort in Biblical hermeneutics to find the intended original meaning in the text.[86] This original intended meaning of the text is drawn out through examination of the passage in light of the grammatical and syntactical aspects, the historical background, the literary genre as well as theological (canonical) considerations.[87] The historical-grammatical method distinguishes between the one original meaning and the significance of the text. The significance of the text includes the ensuing use of the text or application. The original passage is seen as having only a single meaning or sense. As Milton S. Terry said: "A fundamental principle in grammatico-historical exposition is that the words and sentences can have but one significance in one and the same connection. The moment we neglect this principle we drift out upon a sea of uncertainty and conjecture."[88] Technically speaking, the grammatical-historical method of interpretation is distinct from the determination of the passage's significance in light of that interpretation. Taken together, both define the term (Biblical) hermeneutics.[89]

Some Protestant interpreters make use of typology.[90]

Afterlife and Eschaton

Most Christians believe that human beings experience divine judgment and are rewarded either with eternal life or eternal damnation. This includes the general judgement at the Resurrection of the dead (see below) as well as the belief (held by Roman Catholics,[91][92] Orthodox[93][94] and most Protestants) in a judgment particular to the individual soul upon physical death.

In Roman Catholicism, those who die in a state of grace, i.e., without any mortal sin separating them from God, but are still imperfectly purified from the effects of sin, undergo purification through the intermediate state of purgatory to achieve the holiness necessary for entrance into God's presence.[95] Those who have attained this goal are called saints (Latin sanctus, "holy").[96]

Christians believe that the second coming of Christ will occur at the end of time. All who have died will be resurrected bodily from the dead for the Last Judgment. Jesus will fully establish the Kingdom of God in fulfillment of scriptural prophecies.[97][98] Jehovah's Witnesses deny the existence of hell. Instead, they hold that the souls of the wicked will be annihilated.[99]

Worship

Justin Martyr described 2nd century Christian liturgy in his First Apology (c. 150) to Emperor Antoninus Pius, and his description remains relevant to the basic structure of Christian liturgical worship:

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need.

— Justin Martyr[100]

Thus, as Justin described, Christians assemble for communal worship on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, though other liturgical practices often occur outside this setting. Scripture readings are drawn from the Old and New Testaments, but especially the Gospels. Often these are arranged on an annual cycle, using a book called a lectionary. Instruction is given based on these readings, called a sermon, or homily. There are a variety of congregational prayers, including thanksgiving, confession, and intercession, which occur throughout the service and take a variety of forms including recited, responsive, silent, or sung. The Lord's Prayer, or Our Father, is regularly prayed. The Eucharist (called Holy Communion, or the Lord's Supper) is the part of liturgical worship that consists of a consecrated meal, usually bread and wine. Justin Martyr described the Eucharist:

And this food is called among us Eukaristia [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.

— Justin Martyr[100]

Some Christian denominations practice closed communion. They offer communion to those who are already united in that denomination or sometimes individual church. Catholics restrict participation to their members who are not in a state of mortal sin. Most other churches practice open communion since they view communion as a means to unity, rather than an end, and invite all believing Christians to participate.

Some groups depart from this traditional liturgical structure. A division is often made between "High" church services, characterized by greater solemnity and ritual, and "Low" services, but even within these two categories there is great diversity in forms of worship. Seventh-day Adventists meet on Saturday, while others do not meet on a weekly basis. Charismatic or Pentecostal congregations may spontaneously feel led by the Holy Spirit to action rather than follow a formal order of service, including spontaneous prayer. Quakers sit quietly until moved by the Holy Spirit to speak. Some Evangelical services resemble concerts with rock and pop music, dancing, and use of multimedia. For groups which do not recognize a priesthood distinct from ordinary believers the services are generally lead by a minister, preacher, or pastor. Still others may lack any formal leaders, either in principle or by local necessity. Some churches use only a cappella music, either on principle (e.g., many Churches of Christ object to the use of instruments in worship) or by tradition (as in Orthodoxy).

Worship can be varied for special events like baptisms or weddings in the service or significant feast days. In the early church, Christians and those yet to complete initiation would separate for the Eucharistic part of the worship. In many churches today, adults and children will separate for all or some of the service to receive age-appropriate teaching. Such children's worship is often called Sunday school or Sabbath school (Sunday schools are often held before rather than during services).

Sacraments

In Christian belief and practice, a sacrament is a rite, instituted by Christ, that mediates grace, constituting a sacred mystery. The term is derived from the Latin word sacramentum, which was used to translate the Greek word for mystery. Views concerning both what rites are sacramental, and what it means for an act to be a sacrament vary among Christian denominations and traditions.[101]

The most conventional functional definition of a sacrament is that it is an outward sign, instituted by Christ, that conveys an inward, spiritual grace through Christ. The two most widely accepted sacraments are Baptism and the Eucharist, however, the majority of Christians recognize seven Sacraments or Divine Mysteries: Baptism, Confirmation (Chrismation in the Orthodox tradition), and the Eucharist, Holy Orders, Reconciliation of a Penitent (confession), Anointing of the Sick, and Matrimony.[101] Taken together, these are the Seven Sacraments as recognised by churches in the High church tradition—notably Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Independent Catholic, Old Catholic and some Anglicans. Most other denominations and traditions typically affirm only Baptism and Eucharist as sacraments, while some Protestant groups, such as the Quakers, reject sacramental theology.[101] Most Protestant Christian denominations who believe these rites do not communicate grace prefer to call them ordinances.

Liturgical calendar

Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Eastern Christians, and traditional Protestant communities frame worship around a liturgical calendar. This includes holy days, such as solemnities which commemorate an event in the life of Jesus or the saints, periods of fasting such as Lent, and other pious events such as memoria or lesser festivals commemorating saints. Christian groups that do not follow a liturgical tradition often retain certain celebrations, such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost. A few churches make no use of a liturgical calendar.[102]

Symbols

The cross, which is today one of the most widely recognised symbols in the world, was used as a Christian symbol from the earliest times.[103][104] Tertullian, in his book De Corona, tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace repeatedly on their foreheads the sign of the cross.[105] Although the cross was known to the early Christians, the crucifix did not appear in use until the 5th century.[106]

Among the symbols employed by the primitive Christians, that of the fish seems to have ranked first in importance. From monumental sources such as tombs it is known that the symbolic fish was familiar to Christians from the earliest times. The fish was depicted as a Christian symbol in the first decades of the 2nd century.[107] Its popularity among Christians was due principally, it would seem, to the famous acrostic consisting of the initial letters of five Greek words forming the word for fish (Ichthys), which words briefly but clearly described the character of Christ and the claim to worship of believers: Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter, meaning, Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour.[107]

Christians from the very beginning adorned their tombs with paintings of Christ, of the saints, of scenes from the Bible and allegorical groups. The catacombs are the cradle of all Christian art. The first Christians had no prejudice against images, pictures, or statues. The idea that they must have feared the danger of idolatry among their new converts is disproved in the simplest way by the pictures, even statues, that remain from the first centuries.[108] Other major Christian symbols include the chi-rho monogram, the dove (symbolic of the Holy Spirit), the sacrificial lamb (symbolic of Christ's sacrifice), the vine (symbolising the necessary connectedness of the Christian with Christ) and many others. These all derive from writings found in the New Testament.[106]

Baptism

Baptism is the ritual act, with the use of water, by which a person is admitted to membership of the Church.[109]

Prayer

Jesus' teaching on prayer in the Sermon on the Mount displays a distinct lack of interest in the external aspects of prayer. A concern with the techniques of prayer is condemned as 'pagan', and instead a simple trust in God's fatherly goodness is encouraged.Mat. 6:5–15Template:Bibleverse with invalid book Elsewhere in the New Testament this same freedom of access to God is also emphasized.Phil. 4:6Jam. 5:13–19Template:Bibleverse with invalid book This confident position should be understood in light of Christian belief in the unique relationship between the believer and Christ through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit.[110]

In subsequent Christian traditions, certain physical gestures are emphasised, including medieval gestures such as genuflection or making the sign of the cross. Kneeling, bowing and prostrations (see also poklon) are often practiced in more traditional branches of Christianity. Frequently in Western Christianity the hands are placed palms together and forward as in the feudal commendation ceremony. At other times the older orans posture may be used, with palms up and elbows in.

Intercessory prayer is prayer offered for the benefit of other people. There are many intercessory prayers recorded in the Bible, included prayers of the Apostle Peter on behalf of sick personsActs 9:40 and by prophets of the Old Testament in favor of other people.1Ki 17:19–22Template:Bibleverse with invalid book In the New Testament book of James no distinction is made between the intercessory prayer offered by ordinary believers and the prominent Old Testament prophet Elijah.Jam 5:16–18Template:Bibleverse with invalid book The effectiveness of prayer in Christianity derives from the power of God rather than the status of the one praying[110]

The ancient church, in both Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity, developed a tradition of asking for the intercession of (deceased) saints, and this remains the practice of most Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and some Anglican churches. Churches of the Protestant Reformation however rejected prayer to the saints, largely on the basis of the sole mediatorship of Christ.[111] The reformer Huldrych Zwingli admitted that he had offered prayers to the saints until his reading of the Bible convinced him that this was idolatrous.[112]

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church: "Prayer is the raising of one's mind and heart to God or the requesting of good things from God."[113] The Book of Common Prayer in the Anglican tradition is a guide which provides a set order for church services, containing set prayers, scripture readings, and hymns or sung Psalms.

History and origins

This section may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (November 2008) |

Early Church and Christological Councils

Christianity began as a Jewish sect in the eastern Mediterranean in the mid-1st century.[5][9][10] Its earliest development took place under the leadership of the Twelve Apostles, particularly Saint Peter and Paul the Apostle, followed by the early bishops, whom Christians considered the successors of the Apostles.

From the beginning, Christians were subject to persecution by some Jewish religious leaders, who disagreed with the apostles' teachings (See Split of early Christianity and Judaism). This involved punishments, including death, for Christians such as StephenActs 7:59 and James, son of Zebedee.Acts 12:2 Larger-scale persecutions followed at the hands of the authorities of the Roman Empire, first in the year 64, when Emperor Nero blamed them for the Great Fire of Rome. According to Church tradition, it was under Nero's persecution that early Church leaders Peter and Paul of Tarsus were each martyred in Rome. Further widespread persecutions of the Church occurred under nine subsequent Roman emperors, most intensely under Decius and Diocletian. From the year 150, Christian teachers began to produce theological and apologetic works aimed at defending the faith. These authors are known as the Church Fathers, and study of them is called Patristics. Notable early Fathers include Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen.

State persecution ceased in the 4th century, when Constantine I issued an edict of toleration in 313. On 27 February 380, Emperor Theodosius I enacted a law establishing Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire.[114] From at least the 4th century, Christianity has played a prominent role in the shaping of Western civilization.[115]

Constantine was also instrumental in the convocation of the First Council of Nicaea in 325, which sought to address the Arian heresy and formulated the Nicene Creed, which is still used by the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, Anglican Communion, and many Protestant churches.[30] Nicaea was the first of a series of Ecumenical (worldwide) Councils which formally defined critical elements of the theology of the Church, notably concerning Christology.[116] The Assyrian Church of the East did not accept the third and following Ecumenical Councils, and are still separate today.

The presence of Christianity in Africa began in the middle of the 1st century in Egypt, and by the end of the 2nd century in the region around Carthage. Important Africans who influenced the early development of Christianity includes Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, Cyprian, Athanasius and Augustine of Hippo. The later rise of Islam in North Africa reduced the size and numbers of Christian congregations, leaving only the Coptic Church in Egypt and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church in the Horn of Africa. The History of Christianity in Africa began in the 1st century when Mark the Evangelist started the Orthodox Church of Alexandria in about 43 AD.[117][118][119]

Early Middle Ages

With the decline and fall of the Roman Empire in the west, the papacy became a political player, first visible in Pope Leo's diplomatic dealings with Huns and Vandals.[120] The church also entered into a long period of missionary activity and expansion among the various tribes. Whilst arianists instituted the death penalty for practicing pagans (see Massacre of Verden as example), Catholicism also spread among the Germanic peoples ([120] the Celtic and Slavic peoples, the Hungarians, and the Baltic peoples.

Around 500, St. Benedict set out his Monastic Rule, establishing a system of regulations for the foundation and running of monasteries.[120] Monasticism became a powerful force throughout Europe,[120] and gave rise to many early centers of learning, most famously in Ireland, Scotland and Gaul, contributing to the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century.

From the 7th century onwards, Islam conquered the Christian lands of the Middle East, North Africa and much of Spain,[121] resulting in oppression of Christianity and numerous military struggles, including the Crusades, the Spanish Reconquista and wars against the Turks.

The Middle Ages brought about major changes within the church. Pope Gregory the Great dramatically reformed ecclesiastical structure and administration.[122] In the early 8th century, iconoclasm became a divisive issue, when it was sponsored by the Byzantine emperors. The Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (787) finally pronounced in favor of icons.[123] In the early 10th century, western monasticism was further rejuvenated through the leadership of the great Benedictine monastery of Cluny.[124]

High and Late Middle Ages

In the west, from the 11th century onward, older cathedral schools developed into universities (see University of Oxford, University of Paris, and University of Bologna.) Originally teaching only theology, these steadily added subjects including medicine, philosophy and law, becoming the direct ancestors of modern western institutions of learning.[125]

Accompanying the rise of the "new towns" throughout Western Europe, mendicant orders were founded, bringing the consecrated religious life out of the monastery and into the new urban setting. The two principal mendicant movements were the Franciscans[126] and the Dominicans[127] founded by St. Francis and St. Dominic respectively. Both orders made significant contributions to the development of the great universities of Europe. Another new order were the Cistercians, whose large isolated monasteries spearheaded the settlement of former wilderness areas. In this period church building and ecclesiastical architecture reached new heights, culminating in the orders of Romanesque and Gothic architecture and the building of the great European cathedrals.[128]

From 1095 under the pontificate of Urban II, the Crusades were launched.[129] These were a series of military campaigns in the Holy Land and elsewhere, initiated in response to pleas from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I for aid against Turkish expansion. The Crusades ultimately failed to stifle Islamic aggression and even contributed to Christian enmity with the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.[130]

Over a period stretching from the 7th to the 13th century, the Christian Church underwent gradual alienation, resulting in a schism dividing it into a so-called Latin or Western branch, the Roman Catholic Church,[131] and an Eastern, largely Greek, branch, the Orthodox Church. These two churches disagree on a number of administrative, liturgical, and doctrinal issues, most notably papal primacy of jurisdiction.[132][133] The Second Council of Lyon (1274) and the Council of Florence (1439) attempted to reunite the churches, but in both cases the Eastern Orthodox refused to implement the decisions and the two principal churches remain in schism to the present day. However, the Roman Catholic Church has achieved union with various smaller eastern churches.

Beginning around 1184, following the crusade against the Cathar heresy,[134] various institutions, broadly referred to as the Inquisition, were established with the aim of suppressing heresy and securing religious and doctrinal unity within Christianity through conversion and prosecution.[135]

Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation

The 15th-century Renaissance brought about a renewed interest in ancient and classical learning. Another major schism, the Reformation, resulted in the splintering of the Western Christendom into several Christian denominations.[136] Martin Luther in 1517 protested against the sale of indulgences and soon moved on to deny several key points of Roman Catholic doctrine. Others like Zwingli and Calvin further criticized Roman Catholic teaching and worship. These challenges developed into the movement called Protestantism, which repudiated the primacy of the pope, the role of tradition, the seven sacraments, and other doctrines and practices.[137] The Reformation in England began in 1534, when King Henry VIII had himself declared head of the Church of England. Beginning in 1536, the monasteries throughout England, Wales and Ireland were dissolved.[138]

Partly in response to the Protestant Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church engaged in a substantial process of reform and renewal, known as the Counter-Reformation or Catholic Reform.[139] The Council of Trent clarified and reasserted Roman Catholic doctrine. During the following centuries, competition between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism became deeply entangled with political struggles among European states.[140]

Meanwhile, the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492 brought about a new wave of missionary activity. Partly from missionary zeal, but under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Throughout Europe, the divides caused by the Reformation led to outbreaks of religious violence and the establishment of separate state religions in Western Europe: Lutheranism in parts of Germany and in Scandinavia and Anglicanism in England in 1534. Ultimately, these differences led to the outbreak of conflicts in which religion played a key factor. The Thirty Years' War, the English Civil War, and the French Wars of Religion are prominent examples. These events intensified the Christian debate on persecution and toleration.[141]

In the Modern era

In the Modern Era, Christianity has been confronted with various forms of skepticism and with certain modern political ideologies such as Marxism. Events ranged from mere anti-clericalism to violent outbursts against Christianity such as the Dechristianisation during the French Revolution,[142] the Spanish Civil War, and general hostility of Marxist movements, especially the Russian Revolution.

Christian commitment in Europe dropped as modernity and secularism came into their own[clarification needed] in Western Europe, while religious commitments in America have been generally high in comparison to Western Europe. The late 20th century has shown the shift of Christian adherence to the Third World and southern hemisphere in general, with western civilization no longer the chief standard bearer of Christianity.

Some Europeans (including diaspora), Indigenous peoples of the Americas, and natives of other continents have revived their respective peoples' historical folk religions. (see Neo-paganism, Native Americans in the United States#Religion) Approximately 7.1 to 10% of Arabs are Christians[143] most prevalent in Egypt, Syria and Lebanon.

Demographics

With an estimated number of adherents that ranges approximately around 2.1 billion,[144] split into 3 main branches of Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox, Christianity is the world's largest religion.[145] The Christian share of the world's population has stood at around 33 per cent for the last hundred years. This masks a major shift in the demographics of Christianity; large increases in the developing world (around 23,000 per day) have been accompanied by substantial declines in the developed world, mainly in Europe and North America (around 7,600 per day).[146] It is still the predominant religion in Europe, the Americas, the Philippines, and Southern Africa.[147] However it is declining in many areas including the Northern and Western United States,[148] Oceania (Australia and New Zealand), northern Europe (including Great Britain,[149] Scandinavia and other places), France, Germany, the Canadian provinces of Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec, and parts of Asia (especially the Middle East,[150][151][152] South Korea,[153] Taiwan[154] and Macau[155]).

This is true of Christianity as a whole but it should be noted that there are many charismatic movements that have extremely large progress over large parts of the world, including Western countries. It is estimated that 6 million African Muslims convert to Christianity every year[156].

In most countries in the developed world, church attendance among people who continue to identify themselves as Christians has been falling over the last few decades.[157] Some sources view this simply as part of a drift away from traditional membership institutions,[158] while others link it to signs of a decline in belief in the importance of religion in general.[159]

Christianity, in one form or another, is the sole state religion of the following nations: Armenia (Armenian Apostolic),[160] Bolivia (Roman Catholic),[161] Costa Rica (Roman Catholic),[162] Denmark (Evangelical Lutheran),[163] El Salvador (Roman Catholic),[164] England (Anglican),[165] Finland (Evangelical Lutheran & Orthodox),[166][167] Georgia (Georgian Orthodox),[168] Greece (Greek Orthodox),[164] Iceland (Evangelical Lutheran),[169] Liechtenstein (Roman Catholic),[170] Malta (Roman Catholic),[171] Monaco (Roman Catholic),[172] Norway (Evangelical Lutheran),[173] Switzerland (Roman Catholic, Old Catholic, or Protestant—denomination varies per canton)[174] and Vatican City (Roman Catholic).[175]

There are numerous other countries, such as Cyprus, which although do not have an established church, still give official recognition to a specific Christian denomination.[176]

Main grouping of Christianity

The three primary divisions of Christianity are Roman Catholicism, the Orthodox church, and Protestantism.[34]: 14 [177] There are other Christian groups that do not fit neatly into one of these primary categories.[178] The Nicene Creed is "accepted as authoritative by the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and major Protestant churches."[179] There is a diversity of doctrines and practices among groups calling themselves Christian. These groups are sometimes classified under denominations, though for theological reasons many groups reject this classification system.[180] Another distinction that is sometimes drawn is between Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity.

| Christian denominations in the English-speaking world |

|---|

Catholic

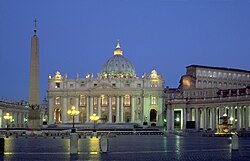

The Catholic Church comprises those particular churches, headed by bishops, in communion with the Pope, the Bishop of Rome, as its highest authority in matters of faith, morality and Church governance.[181][182] Like the Eastern Orthodox, the Roman Catholic Church through Apostolic succession traces its origins to the Christian community founded by Jesus Christ.[183][184] Catholics maintain that the "one, holy, catholic and apostolic church" founded by Jesus subsists fully in the Roman Catholic Church, but also acknowledges other Christian churches and communities[185][186] and works towards reconciliation among all Christians.[185] The Catholic faith is detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[187][188]

The 2,782 sees[189] are grouped into 23 particular rites, the largest being the Latin Rite, each with distinct traditions regarding the liturgy and the administering the sacraments.[190] With more than 1.1 billion baptized members, the Catholic Church is the largest church representing over half of all Christians and one sixth of the world's population.[191][192][193]

Various smaller communities, such as the Old Catholic and Independent Catholic Churches, include the word Catholic in their title, and share much in common with Roman Catholicism but are no longer in communion with the See of Rome. The Old Catholic Church is in communion with the Anglican Communion.[194][195]

Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy comprises those churches in communion with the Patriarchal Sees of the East, such as the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.[196] Like the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church also traces its heritage to the foundation of Christianity through Apostolic succession and has an episcopal structure, though the autonomy of the individual, mostly national churches is emphasized. A number of conflicts with Western Christianity over questions of doctrine and authority culminated in the Great Schism. Eastern Orthodoxy is the second largest single denomination in Christianity, with over 200 million adherents.[191]

The Oriental Orthodox Churches (also called Old Oriental Churches) are those eastern churches that recognize the first three ecumenical councils—Nicaea, Constantinople and Ephesus—but reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon and instead espouse a Miaphysite christology. The Oriental Orthodox communion comprises six groups: Syriac Orthodox, Coptic Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, Eritrean Orthodox, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (India) and Armenian Apostolic churches.[197] These six churches, while being in communion with each other are completely independent hierarchically.[198] These churches are generally not in communion with Eastern Orthodox Churches with whom they are in dialogue for a return to unity.[199]

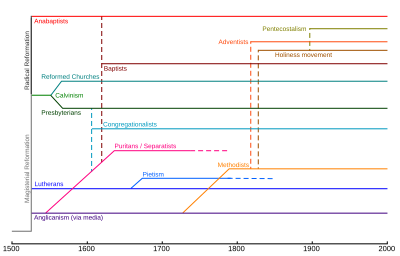

Protestant

In the 16th century, Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, and John Calvin inaugurated what has come to be called Protestantism. Luther's primary theological heirs are known as Lutherans. Zwingli and Calvin's heirs are far broader denominationally, and are broadly referred to as the Reformed Tradition.[200] Most Protestant traditions branch out from the Reformed tradition in some way. In addition to the Lutheran and Reformed branches of the Reformation, there is Anglicanism after the English Reformation. The Anabaptist tradition was largely ostracized by the other Protestant parties at the time, but has achieved a measure of affirmation in more recent history. Some but not most Baptists prefer not to be called Protestants, claiming a direct ancestral line going back to the apostles in the 1st century.[201]

The oldest Protestant groups separated from the Catholic Church in the 16th century Protestant Reformation, followed in many cases by further divisions.[200] For example, the Methodist Church grew out of Anglican minister John Wesley's evangelical and revival movement in the Anglican Church.[202][203] Several Pentecostal and non-denominational Churches, which emphasize the cleansing power of the Holy Spirit, in turn grew out of the Methodist Church.[203][204] Because Methodists, Pentecostals, and other evangelicals stress "accepting Jesus as your personal Lord and Savior",[205] which comes from John Wesley's emphasis of the New Birth,[206] they often refer to themselves as being born-again.[207][208]

Estimates of the total number of Protestants are very uncertain, partly because of the difficulty in determining which denominations should be placed in these categories, but it seems clear that Protestantism is the second largest major group of Christians after Catholicism in number of followers (although the Orthodox Church is larger than any single Protestant denomination).[191]

A special grouping are the Anglican churches descended from the Church of England and organised in the Anglican Communion. Some Anglican churches consider themselves both Protestant and Catholic.[209] Some Anglicans consider their church a branch of the "One Holy Catholic Church" alongside of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, a concept rejected by the Roman Catholic Church and some Eastern Orthodox.[210][211]

Some groups of individuals who hold basic Protestant tenants identify themselves simply as "Christians" or "born-again Christians". They typically distance themselves from the confessionalism and/or creedalism of other Christian communities[212] by calling themselves "non-denominational". Often founded by individual pastors, they have little affiliation with historic denominations.[213]

Others

Esoteric Christianity is a term which refers to an ensemble of spiritual currents which regard Christianity as a mystery religion,[214][215] and profess the existence and possession of certain esoteric doctrines or practices,[216][217] hidden from the public but accessible only to a narrow circle of "enlightened", "initiated", or highly educated people.[218][219]. A special characteristic common in these mystical denominations is the belief in the reincarnation and the evolution. These beliefs are not well accepted in the mainstream Christianity. Some of the esoteric christian institutions include the Rosicrucian Fellowship, the Anthroposophical Society and the Martinism.

The Second Great Awakening, a period of religious revival that occurred in the U.S. during the early 1800s, saw the development of a number of unrelated churches. They generally saw themselves as restoring the original church of Jesus Christ rather than reforming one of the existing churches.[220] A common belief held by Restorationists was that the other divisions of Christianity had introduced doctrinal defects into Christianity, which was known as the Great Apostasy.[221][222]

Some of the churches originating during this period are historically connected to early-19th century camp meetings in the Midwest and Upstate New York. American Millennialism and Adventism, which arose from Evangelical Protestantism, influenced the Jehovah's Witnesses movement (with 7 million members),[223] and, as a reaction specifically to William Miller, the Seventh-day Adventists. Others, including the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Evangelical Christian Church in Canada, Churches of Christ, and the Independent Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, have their roots in the contemporaneous Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement, which was centered in Kentucky and Tennessee. Other groups originating in this time period include the Christadelphians and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the largest denomination of the Latter Day Saint movement with over 13 million members.[224][225][226][227] While the churches originating in the Second Great Awakening have some superficial similarities, their doctrine and practices vary significantly.

Cultural Christian

Cultural Christian is a broad term used to describe people with either ethnic or religious Christian heritage who may not believe in the religious claims of Christianity, but who retain an affinity for the culture, art, music, and so on related to it.

Many of the population of the Western hemisphere could broadly be described as cultural Christians, due to the predominance of the Christian faith in Western culture, as well as widely celebrated religious holidays such as Easter and Christmas. Another frequent application of the term is to distinguish political groups in areas of mixed religious backgrounds. The term "cultural Christian" is often used pejoratively by more religious, usually fundamentalist, Christians.

Ecumenism

Most churches have long expressed ideals of being reconciled with each other, and in the 20th century Christian ecumenism advanced in two ways.[228] One way was greater cooperation between groups, such as the Edinburgh Missionary Conference of Protestants in 1910, the Justice, Peace and Creation Commission of the World Council of Churches founded in 1948 by Protestant and Orthodox churches, and similar national councils like the National Council of Churches in Australia which includes Roman Catholics.[228]

The other way was institutional union with new United and uniting churches. Congregationalist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches united in 1925 to form the United Church of Canada,[229] and in 1977 to form the Uniting Church in Australia. The Church of South India was formed in 1947 by the union of Anglican, Methodist, Congregationalist, Presbyterian, and Reformed churches.[230]

Steps towards reconciliation on a global level were taken in 1965 by the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches mutually revoking the excommunications that marked their Great Schism in 1054;[231] the Anglican Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC) working towards full communion between those churches since 1970;[232] and the Lutheran and Roman Catholic churches signing The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification in 1999 to address conflicts at the root of the Protestant Reformation. In 2006, the Methodist church adopted the declaration.[233]

See also

- Christian World

- Christian Apologetics

- Criticism of Christianity

- Freedom of religion

- Good news (Christianity), concerning the gospel message

- Christian art

- Christian philosophy

- Christian symbolism

- Christian architecture

- Political Catholicism

- Gospel

- Bible

- Evangelism

- Messianic Judaism

Endnotes

- ^ Christianity's status as monotheistic is affirmed in, amongst other sources, the Catholic Encyclopedia (article "Monotheism"); William F. Albright, From the Stone Age to Christianity; H. Richard Niebuhr; About.com, Monotheistic Religion resources; Kirsch, God Against the Gods; Woodhead, An Introduction to Christianity; The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia Monotheism; The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, monotheism; New Dictionary of Theology, Paul, pp. 496–99; Meconi. "Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity". p. 111f.

- ^ BBC, BBC—Religion & Ethics—566, Christianity

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=q-vhwjamOioC&pg=PA23&dq=anagignoskomena#v=onepage&q=anagignoskomena&f=true

- ^ Briggs, Charles A. The fundamental Christian faith: the origin, history and interpretation of the Apostles' and Nicene creeds. C. Scribner's sons, 1913. Books.Google.com

- ^ a b The term "Christian" (Greek [Χριστιανός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) was first used in reference to Jesus' disciples in the city of AntiochActs 11:26 about 44 AD, meaning "followers of Christ". The name was given by the non-Jewish inhabitants of Antioch, probably in derision, to the disciples of Jesus. In the New Testament the names by which the disciples were known among themselves were "brethren", "the faithful", "elect", "saints", "believers". The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity" (Greek [Χριστιανισμός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) was by Ignatius of Antioch, around 100 AD. See Elwell/Comfort. Tyndale Bible Dictionary, pp. 266, 828

- ^ Defined to avoid the ambiguous term "orthodox"

- ^ Sheed, Frank. "Theology and Sanity." (Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 1993), pp. 276.

- ^ a b McGrath, Christianity: An Introduction, pp. 4-6.

- ^ a b Robinson, Essential Judaism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs and Rituals, p. 229.

- ^ a b Esler. The Early Christian World. p. 157f.

- ^ J.Z.Smith, p. 276.

- ^ Anidjar, p. 3.

- ^ Fowler, World Religions: An Introduction for Students, p. 131.

- ^ Religion in the Roman Empire, Wiley-Blackwell, by James B. Rives, page 196

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity, pp. 301-03.

- ^ 33.2% of 6.7 billion world population (under the section 'People') "World". CIA world facts.

- ^ "The List: The World's Fastest-Growing Religions". foreignpolicy.com. 2007-03. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Major Religions Ranked by Size". Adherents.com. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Hinnells, The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion, p. 441.

- ^ See Christianity#Demographics for information and references

- ^ Olson, The Mosaic of Christian Belief.

- ^ Pelikan/Hotchkiss, Creeds and Confessions of Faith in the Christian Tradition.

- ^ Catholics United for the Faith, "We Believe in One God"

- ^ Encyclopedia of Religion, "Arianism".[clarification needed]

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Council of Ephesus".

- ^ Christian History Institute, First Meeting of the Council of Chalcedon.

- ^ British Orthodox Church, The Oriental Orthodox Rejection of Chalcedon

- ^ Pope Leo I, Letter to Flavian

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Athanasian Creed".

- ^ a b "Our Common Heritage as Christians". The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ Avis, Paul (2002) The Christian Church: An Introduction to the Major Traditions, SPCK, London, ISBN 0-281-05246-8 paperback

- ^ White, The History of the Church.

- ^ Cummins, Duane D. (1991). A handbook for Today's Disciples in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) Revised Edition. St Louis, MO: Chalice Press. ISBN 0-8272-1425-1.

- ^ a b Ron Rhodes, The Complete Guide to Christian Denominations, Harvest House Publishers, 2005, ISBN 0-7369-1289-4

- ^ Metzger/Coogan, Oxford Companion to the Bible, pp. 513, 649.

- ^ Acts 2:24, 2:31–32, 3:15, 3:26, 4:10, 5:30, 10:40–41, 13:30, 13:34, 13:37, 17:30–31, Romans 10:9, 1 Cor. 15:15, 6:14, 2 Cor. 4:14, Gal 1:1, Eph 1:20, Col 2:12, 1 Thess. 11:10, Heb. 13:20, 1 Pet. 1:3, 1:21

- ^ "Nicene Creed—Wikisource". En.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Hanegraaff. Resurrection: The Capstone in the Arch of Christianity.

- ^ "The Significance of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus for the Christian". Australian Catholic University National. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ "Why is the resurrection of Jesus Christ important?". Got Questions Ministries. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ John 3:16, 5:24, 6:39–40, 6:47, 10:10, 11:25–26, and 17:3

- ^ This is drawn from a number of sources, especially the early Creeds, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, certain theological works, and various Confessions drafted during the Reformation including the Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, works contained in the Book of Concord.

- ^ Fuller, The Foundations of New Testament Christology, p. 11.

- ^ A Jesus Seminar conclusion: "in the view of the Seminar, he did not rise bodily from the dead; the resurrection is based instead on visionary experiences of Peter, Paul, and Mary."

- ^ Funk. The Acts of Jesus: What Did Jesus Really Do?.

- ^ Lorenzen. Resurrection, Discipleship, Justice: Affirming the Resurrection Jesus Christ Today, p. 13.

- ^ Ball/Johnsson (ed.). The Essential Jesus.

- ^ a b Eisenbaum, Pamela (2004). "A Remedy for Having Been Born of Woman: Jesus, Gentiles, and Genealogy in Romans" (PDF). Journal of Biblical Literature. 123 (4): 671–702. doi:10.2307/3268465. JSTOR 3268465. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wright, N.T. What Saint Paul Really Said: Was Paul of Tarsus the Real Founder of Christianity? (Oxford, 1997), p. 121.

- ^ CCC 846; Vatican II, Lumen Gentium 14

- ^ See quotations from Council of Trent on Justification at Justforcatholics.org

- ^ Westminster Confession, Chapter X; Spurgeon, A Defense of Calvinism.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, Grace and Justification

- ^ Kelly. Early Christian Doctrines. pp. 87-90.

- ^ Alexander. New Dictionary of Biblical Theology. p. 514f.

- ^ McGrath. Historical Theology. p. 61.

- ^ Metzger/Coogan. Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 782.

- ^ Kelly. The Athanasian Creed.

- ^ Oxford, "Encyclopedia Of Christianity, pg1207

- ^ Fowler. World Religions: An Introduction for Students. p. 58.

- ^ Theophilus of Antioch Apologia ad Autolycum II 15

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. p. 50.

- ^ Tertullian De Pudicitia chapter 21

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity, p. 53.

- ^ Moltman, Jurgen. The Trinity and the Kingdom: The Doctrine of God. Tr. from German. Fortress Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8006-2825-X

- ^ Harnack, History of Dogma.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture (§105-108)

- ^ Second Helvetic Confession, Of the Holy Scripture Being the True Word of God

- ^ Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, online text

- ^ "PC (USA)—Presbyterian 101—What is The Bible?". Pcusa.org. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Bruce, The Canon of Scripture; Catechism of the Catholic Church, "The Canon of Scripture", § 120

- ^ Metzger/Coogan, Oxford Companion to the Bible. p. 39.

- ^ Kelly. Early Christian Doctrines. pp. 69-78.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, The Holy Spirit, Interpreter of Scripture § 115-118.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, "Whether in Holy Scripture a word may have several senses"

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, §116

- ^ Second Vatican Council, Dei Verbum (V.19).

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, "The Holy Spirit, Interpreter of Scripture" § 113.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, "The Interpretation of the Heritage of Faith" § 85.

- ^ Mathison. The Shape of Sola Scriptura.[clarification needed]

- ^ a b Foutz, Martin Luther and Scripture.

- ^ John Calvin, Commentaries on the Catholic Epistles 2 Peter 3:14-18

- ^ Article about Helvetic confessions

- ^ Second Helvetic Confession, Of Interpreting the Holy Scriptures; and of Fathers, Councils, and Traditions

- ^ Sproul. Knowing Scripture, pp. 45-61; Bahnsen, A Reformed Confession Regarding Hermeneutics (article 6).

- ^ Elwell, Walter A. (1984). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House. ISBN 0801034132.

- ^ Johnson, Elliott (1990). Expository hermeneutics : an introduction. Grand Rapids Mich.: Academie Books. ISBN 9780310341604.

- ^ Terry, Milton (1974). Biblical hermeneutics : a treatise on the interpretation of the Old and New Testaments. Grand Rapids Mich.: Zondervan Pub. House. p. 205

- ^ Elwell, Walter A. (1984). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House. ISBN 0801034132. p. 565

- ^ e.g., in his commentary on Matthew 1 (§III.3) Matthew Henry interprets the twin sons of Judah, Phares and Zara, as an allegory of the Gentile and Jewish Christians. For a contemporary treatment, see Glenny, Typology: A Summary Of The Present Evangelical Discussion.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Particular Judgment".

- ^ Ott, Grundriß der Dogmatik, p. 566.

- ^ David Moser, What the Orthodox believe concerning prayer for the dead.

- ^ Ken Collins, What Happens to Me When I Die?.

- ^ Audience of 4 August 1999

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "The Communion of Saints".

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicum, Supplementum Tertiae Partis questions 69 through 99

- ^ Calvin, John. "Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book Three, Ch. 25". www.reformed.org. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The death that Adam brought into the world is spiritual as well as physical, and only those who gain entrance into the Kingdom of God will exist eternally. However, this division will not occur until Armageddon, when all people will be resurrected and given a chance to gain eternal life. In the meantime, "the dead are conscious of nothing."What is God's Purpose for the Earth?" Official Site of Jehovah's Witnesses. Watchtower, July 15, 2002.

- ^ a b Justin Martyr, First Apology §LXVII

- ^ a b c Cross/Livingstone. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. p. 1435f.

- ^ Hickman. Handbook of the Christian Year.

- ^ "ANF04. Fathers of the Third Century: Tertullian, Part Fourth; Minucius Felix; Commodian; Origen, Parts First and Second | Christian Classics Ethereal Library". Ccel.org. 2005-06-01. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Minucius Felix speaks of the cross of Jesus in its familiar form, likening it to objects with a crossbeam or to a man with arms outstretched in prayer (Octavius of Minucius Felix, chapter XXIX).

- ^ "At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign." (Tertullian, De Corona, chapter 3)

- ^ a b Dilasser. The Symbols of the Church.

- ^ a b Catholic Encyclopedia, "Symbolism of the Fish".

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Veneration of Images.

- ^ "Through Baptism we are freed from sin and reborn as sons of God; we become members of Christ, are incorporated into the Church and made sharers in her mission" (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1213;] "Holy Baptism is the sacrament by which God adopts us as his children and makes us members of Christ's Body, the Church, and inheritors of the kingdom of God" (Book of Common Prayer, 1979, Episcopal ); "Baptism is the sacrament of initiation and incorporation into the body of Christ" (An United Methodist Understanding of Baptism); "As an initiatory rite into membership of the Family of God, baptismal candidates are symbolically purified or washed as their sins have been forgiven and washed away" (William H. Brackney, Believer's Baptism).

- ^ a b Alexander, T. D., & Rosner, B. S, ed. (2001). "Prayer". New Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "Saints". New Dictionary of Theology. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press. 1988.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Madeleine Gray, The Protestant Reformation, (Sussex Academic Press, 2003), page 140.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church: Part Four - Christian Prayer

- ^ Theodosian Code XVI.i.2, in: Bettenson. Documents of the Christian Church. p. 31.

- ^ Orlandis, A Short History of the Catholic Church (1993), preface.

- ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity, p. 37f.

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea, the author of Ecclesiastical History in the 4th century, states that St. Mark came to Egypt in the first or third year of the reign of Emperor Claudius, i.e. 41 or 43 AD. "Two Thousand years of Coptic Christianity" Otto F.A. Meinardus p28.

- ^ Bethel.edu

- ^ Allaboutreligion.org

- ^ a b c d Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 238–42.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 248–50.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 244–47.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, p. 260.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 278–81.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 305, 312, 314f..

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 303–07, 310f., 384–86.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 305, 310f., 316f.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 321–23, 365f.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 292–300.

- ^ Riley-Smith. The Oxford History of the Crusades.

- ^ The Western church was called Latin at the time by the Eastern Christians and non Christians due to its conducting of its rituals and affairs in the Latin language

- ^ "The Great Schism: The Estrangement of Eastern and Western Christendom". Orthodox Information Centre. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), p. 91

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 300, 304–05.

- ^ Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, pp. 310, 383, 385, 391.

- ^ Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. p. 7.

- ^ Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. pp. 39, 55–61.

- ^ Schama. A History of Britain. pp. 306–10.

- ^ Bokenkotter, A Concise History of the Catholic Church, pp. 242–44.

- ^ Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. pp. 109–120.

- ^ A general overview about the English discussion is given in Coffey, Persecution and Toleration in Protestant England 1558–1689.

- ^ Mortimer Chambers, The Western Experience (vol. 2) chapter 21.

- ^ ed. by Andrea Pacini (1998). Christian Communities in the Middle East. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829388-7.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Adherents.com– Number of Christians in the world

- ^ "Major Religions Ranked by Size". Adherents. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ Werner Ustorf. "A missiological postscript", in McLeod and Ustorf (eds), The Decline of Christendom in Western Europe, 1750-2000, (Cambridge University Press, 2003) pp. 219–20.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica table of religions, by region. Retrieved November 2007.

- ^ American Religious Identification Survey 2008

- ^ New UK opinion poll shows continuing collapse of 'Christendom'

- ^ Barrett/Kurian.World Christian Encyclopedia, p. 139 (Britain), 281 (France), 299 (Germany).

- ^ BBC NEWS—Guide: Christians in the Middle East

- ^ Is Christianity dying in the birthplace of Jesus?

- ^ Number of Christians among young Koreans decreases by 5% per year

- ^ "Christianity fading in Taiwan | American Buddhist Net". Americanbuddhist.net. 2007-11-10. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ A Gambling-Fueled Boom Adds to a Church’s Bane

- ^ Six Million African Muslims Convert to Christianity Each Year - Al-Jazeerah Website

- ^ Putnam, Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society, p. 408.

- ^ McGrath, Christianity: An Introduction, p. xvi.

- ^ Peter Marber, Money Changes Everything: How Global Prosperity Is Reshaping Our Needs, Values and Lifestyles, p. 99.

- ^ "Gov. Pataki Honors 1700th Anniversary of Armenia's Adoption of Christianity as a state religion". Aremnian National Committe of America. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

- ^ "Bolivia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Costa Rica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Denmark". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ a b "El Salvador". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Church and State in Britain: The Church of privilege". Centre for Citizenship. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Official Religions of Finland". Finish Tourist Board. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "State and Church in Finland". Euresis. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "McCain Praises Georgia For Adopting Christianity As Official State Religion". BeliefNet. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

- ^ "Iceland". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Liechtenstein". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Malta". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Monaco". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Norway". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Switzerland". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Vatican". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Cyprus". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Divisions of Christianity". North Virginia College. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "The LDS Restorationist movement, including Mormon denominations". Religious Tolerance. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "Nicene Creed". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sydney E. Ahlstrom ([clarification needed], p. 381.) characterized denominationalism in America as "a virtual ecclesiology" that "first of all repudiates the insistences of the Roman Catholic church, the churches of the 'magisterial' Reformation, and of most sects that they alone are the true Church." For specific citations, on the Roman Catholic Church see the Catechism of the Catholic Church §816; other examples: Donald Nash, Why the Churches of Christ are not a Denomination; Wendell Winkler, Christ's Church is not a Denomination; and David E. Pratt, What does God think about many Christian denominations?

- ^ Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium.

- ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners, p. 1.

- ^ Hitchcock, Geography of Religion, p. 281.

- ^ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History, p. 11, 14.

- ^ a b Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, chapter 2, paragraph 15.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 865.

- ^ Marthaler, Introducing the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Traditional Themes and Contemporary Issues (1994), preface.

- ^ John Paul II, Pope (1997). "Laetamur Magnopere". Vatican. Archived from the original on 2008-02-11. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ Annuario Pontificio (2007), p. 1172.

- ^ Barry, One Faith, One Lord (2001), p. 71

- ^ a b c Adherents.com, Religions by Adherents

- ^ Zenit.org, "Number of Catholics and Priests Rises", 12 February 2007.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency, CIA World Factbook (2007).

- ^ According to the Bonn Accord of 1931, cited at Old Catholic Church of the Beatitudes.

- ^ Council of Anglican Episcopal Churches in Germany.

- ^ Cross/Livingstone. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, p. 1199.

- ^ Oriental Orthodox Churches

- ^ An Introduction to the Oriental Orthodox Churches

- ^ Syrian Orthodox Resources -- Middle Eastern Oriental Orthodox Common Declaration

- ^ a b McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. pp. 251–59.

- ^ Dr. James Milton Carroll. The Trail of Blood. The School of Biblical & Theological Studies (2004).

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "About The Methodist Church". Methodist Central Hall Westminster. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ a b "American Holiness Movement". Finding Your Way, Inc. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "Christianity: Pentecostal Churches". Finding Your Way, Inc. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "Statement of Belief". Cambridge Christ United Methodist Church. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "The New Birth by John Wesley (Sermon 45)". The United Methodist Church GBGM. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "God's Preparing, Accepting, and Sustaining Grace". The United Methodist Church GBGM. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "Total Experience of the Spirit". Warren Wilson College. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ Sykes/Booty/Knight. The Study of Anglicanism, p. 219.

- ^ Gregory Hallam, Orthodoxy and Ecumenism.

- ^ Gregory Mathewes-Green, "Whither the Branch Theory?", Anglican Orthodox Pilgrim Vol. 2, No. 4.

- ^ Confessionalism is a term employed by historians to describe "the creation of fixed identities and systems of beliefs for separate churches which had previously been more fluid in their self-understanding, and which had not begun by seeking separate identities for themselves—they had wanted to be truly Catholic and reformed." (MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History, p. xxiv.)