Fentanyl

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Actiq, Duragesic, Fentora, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Very high |

| Routes of administration | Buccal, epidural, IM, IT, IV, sublingual, skin patch |

| Drug class | Opioid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 92% (transdermal) 89% (intranasal) 50% (buccal) 33% (ingestion) |

| Protein binding | 80–85% |

| Metabolism | hepatic, primarily by CYP3A4 |

| Onset of action | 5 minutes[2] |

| Elimination half-life | IV: 6 mins (T1/2 α) 1 hours (T1/2 β) 16 hours (T1/2 ɣ) Intranasal: 6.5 hours Transdermal: 20–27 hours[3] Sublingual/buccal (single dose): 2.6–13.5 hours[3] |

| Duration of action | IV: 30–60 minutes[4][2] |

| Excretion | Mostly urinary (metabolites, <10% unchanged drug)[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.468 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

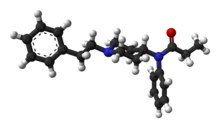

| Formula | C22H28N2O |

| Molar mass | 336.471 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 87.5 °C (189.5 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Fentanyl, also spelled fentanil, is an opioid which is used as a pain medication and together with other medications for anesthesia.[3] It has a rapid onset and effects generally last less than an hour or two.[3] Fentanyl is available in a number of forms including by injection, as a skin patch, and to be absorbed through the tissues inside the mouth.[3]

Common side effects include nausea, constipation, sleepiness, and confusion.[3] Serious side effects may include a decreased effort to breathe (respiratory depression), serotonin syndrome, low blood pressure, or addiction.[3] Fentanyl works in part by activating μ-opioid receptors.[3] It is about 75 times stronger than morphine for a given amount.[5] Some fentanyl analogues may be as much as 10,000 times stronger than morphine.[6]

Fentanyl was first made by Paul Janssen in 1960 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1968.[3][7] It was developed by testing chemicals similar in structure to pethidine (meperidine) for opioid activity.[8] In 2015, 1,600 kilograms (3,500 lb) were used globally.[9] As of 2017[update], fentanyl was the most widely used synthetic opioid in medicine.[10]

Fentanyl patches are on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[11] The wholesale cost in the developing world as of 2015 is between US$0.08 and US$0.81 per 100 microgram vial.[12] In the United States this amount costs about US$0.40 as of 2017.[13] Fentanyl is also made illegally and used as a recreational drug often mixed with heroin or cocaine.[14] In 2016 more than 20,000 deaths occurred in the United States due to overdoses of fentanyl and its analogues.[15]

Medical uses

Intravenous and intrathecal

Intravenous fentanyl is often used for anaesthesia and analgesia. During anaesthesia it is often used along with a hypnotic agent like propofol. It is also administered in combination with a benzodiazepine, such as midazolam, to produce sedation for procedures such as endoscopy, cardiac catheterization, and oral surgery, or in emergency rooms.[16][17] It is often used in the management of chronic pain including cancer pain.[18]

Fentanyl is sometimes given intrathecally as part of spinal anaesthesia or epidurally for epidural anaesthesia and analgesia. Because of fentanyl's high lipid solubility, its effects are more localized than morphine, and some clinicians prefer to use morphine to get a wider spread of analgesia.[19]

Patches

Fentanyl transdermal patches (Durogesic/Duragesic) are used in chronic pain management. The patches work by slowly releasing fentanyl through the skin into the bloodstream over 48 to 72 hours, allowing for long-lasting pain management.[20] Dosage is based on the size of the patch, since, in general, the transdermal absorption rate is constant at a constant skin temperature.[20] Rate of absorption is dependent on a number of factors. Body temperature, skin type, amount of body fat, and placement of the patch can have major effects. The different delivery systems used by different makers will also affect individual rates of absorption. Under normal circumstances, the patch will reach its full effect within 12 to 24 hours; thus, fentanyl patches are often prescribed with a fast-acting opioid (such as morphine or oxycodone) to handle breakthrough pain.[20]

It is unclear if fentanyl gives long-term pain relief to people with neuropathic pain.[21]

In palliative care, transdermal fentanyl has a definite, but limited, role for:

- people already stabilized on other opioids who have persistent swallowing problems and cannot tolerate other parenteral routes such as subcutaneous administration.

- people with moderate to severe kidney failure.

- troublesome side effects of oral morphine, hydromorphone, or oxycodone.[citation needed]

Care must be taken to guard against the application of external heat sources (such as direct sunlight, heating pads, etc.) which in certain circumstances can trigger the release of too much medication and cause life-threatening complications.

Duragesic was first approved by the College ter Beoordeling van Geneesmiddelen, the Medicines Evaluation Board in the Netherlands, on July 17, 1995, as 25, 50, 75 and 100 µg/h formulations after a set of successful clinical trials, and on October 27, 2004, the 12 µg/h (actually 12.5 µg/h) formulation was approved as well. On January 28, 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved first-time generic formulations of 25, 50, 75, and 100 µg/h fentanyl transdermal systems (made by Mylan Technologies, Inc.; brand name Duragesic, made by Alza Corp.) through an FTC consent agreement derailing the possibility of a monopoly in the treatment of breakthrough chronic pain by Alza Corp. In some cases, physicians instruct patients to apply more than one patch at a time, giving a much wider range of possible dosages. For example, a patient may be prescribed a 37.5 µg dosage by applying one 12.5 µg patch and one 25 µg patch simultaneously, or contingent on the large size of the (largest) 100 μg/h patch, multiple patches are commonly prescribed for doses exceeding 100μg/h, such as two 75 μg/h patches worn to afford a 150 μg/h dosage regimen. Although the commonly referred to dosage rates are 12/25/50/75/100 µg/h, the "12 µg" patch actually releases 12.5 µg/h.[22] It is designed to release half the dose of the 25 µg/h dose patch.

As of July 2009, construction of the Duragesic patch had been changed from the gel pouch and membrane design to "a drug-in-adhesive matrix designed formulation", as described in the prescribing information.[22] This construction makes illicit use of the fentanyl more difficult.

Storage and disposal

The fentanyl patch is one of a small number of medications that may be especially harmful, and in some cases fatal, with just one dose, if used by someone other than the person for whom the medication was prescribed.[23] Unused fentanyl patches should be kept in a secure location that is out of children’s sight and reach, such as a locked cabinet.

When patches cannot be disposed of through a medication take-back program, flushing is recommended for fentanyl patches because it is the fastest and surest way to remove them from the home so they cannot harm children, pets and others who were not intended to use them.[23][24][25]

Recalls

In February 2004, a leading fentanyl supplier, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, L.P., recalled one lot, and then later, additional lots of fentanyl (brand name: Duragesic) patches because of seal breaches which might have allowed the medication to leak from the patch. A series of Class II recalls was initiated in March 2004, and in February 2008 ALZA Corporation recalled their 25 µg/h Duragesic patches due to a concern that small cuts in the gel reservoir could result in accidental exposure of patients or health care providers to the fentanyl gel.[26]

In February 2011, the manufacturer suspended production of all Duragesic patches due to quality control issues involving unspecified "microscopic crystallization" detected during the manufacturing process of the 100 µg/h strength.[citation needed]

Intranasal

The bioavailability of intranasal fentanyl is about 70–90%, but with some imprecision due to clotted nostrils, pharyngeal swallow and incorrect administration. For both emergency and palliative use, intranasal fentanyl is available in doses of 50, 100, and 200 µg. In emergency medicine, safe administration of intranasal fentanyl with a low rate of side effects and a promising pain reducing effect was demonstrated in a prospective observational study in about 900 out-of-hospital patients.[27]

In children, intranasal fentanyl is useful for the treatment of moderate and severe pain and is well tolerated.[28]

Sublingual

Abstral dissolves quickly and is absorbed through the sublingual mucosa to provide rapid analgesia.[29] Fentanyl is a highly lipophilic compound,[29][30] which is well absorbed sublingually and generally well tolerated.[29] Such forms are particularly useful for breakthrough cancer pain episodes, which are often rapid in onset, short in duration and severe in intensity.[31]

Lozenges

Fentanyl lozenges (Actiq) are a solid formulation of fentanyl citrate on a stick in the form of a lollipop that dissolves slowly in the mouth for transmucosal absorption. These lozenges are intended for opioid-tolerant individuals and are effective in treating breakthrough cancer pain.[32] It has also been used for breakthrough pain for patients with nonmalignant (not cancer related) pain, but this application is controversial.[33] The unit is a berry-flavoured lozenge on a stick swabbed on the mucosal surfaces inside the mouth—inside of the cheeks, under and on the tongue and gums—to release the fentanyl quickly into the system. It is most effective when the lozenge is consumed within 15 minutes. About 25% of the medication is absorbed through the oral mucosa, resulting in a fast onset of action, and the rest is swallowed and absorbed in the small intestine, acting more slowly. The lozenge is less effective and acts more slowly if swallowed as a whole, as despite good absorbance from the small intestine there is extensive first-pass metabolism, leading to an oral bioavailability of about 33% as opposed to 50% when used correctly, (25% via the mouth mucosa and 25% via the gut).[32]

Actiq is produced by the pharmaceutical company Cephalon on a plastic stick; this provides the means by which the medication can maintain its placement while it dissolves slowly in the mouth for absorption across the buccal mucosa, in a manner similar to sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone film strips. An Actiq lozenge contains two grams of sugar (eight calories).[34][35] Actiq has been linked to dental decay, with some users who had no prior dental issues suffering tooth loss, and in the U.S many users have started their own Facebook pages to educate users about the severe dental issues caused by the so-called fentanyl lollipops. CBS News reported the issue 28 September 2009. The status of a sugar-free version, called Actiq-SF, is unclear. Since the release of Fentora—an effervescent buccal fentanyl tablet for breakthrough cancer pain—Cephalon has indefinitely postponed plans to release a sugar-free version of Actiq.[citation needed]

Beginning late September 2006, a generic "oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate" has been available, made by Barr Pharmaceuticals.[36]

The United States Air Force Pararescue and Swedish armed forces combat medics utilize lollipops with fentanyl.[37] Navy corpsmen working with the United States Marine Corps in Afghanistan use fentanyl lollipops on combat casualties from IED blasts and other mechanisms of injury. The lollipop is taped to the casualty's finger and inserted in between the teeth and cheek (buccal area) of the patient. When enough of the medication has been absorbed, the finger will generally fall from the patient's mouth, thereby indicating that the medication has become effectively administered.

Other

Some preparations such as nasal sprays and inhalers may result in a rapid response, but the fast onset of high blood levels may compromise safety. In addition, the expense of some of these appliances may greatly reduce their cost-effectiveness. In children it is unclear if intranasal fentanyl is as good as or the same as morphine.[38]

A fentanyl patient-controlled transdermal system (PCTS) is under development, which aims to allow patients to control administration of fentanyl through the skin during the treatment of perioperative pain.[39]

Adverse effects

Fentanyl's most common side effects (more than 10% of patients) include diarrhea, nausea, constipation, dry mouth, somnolence, confusion, asthenia (weakness), sweating, and less frequently (3 to 10% of patients) abdominal pain, headache, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss, dizziness, nervousness, hallucinations, anxiety, depression, flu-like symptoms, dyspepsia (indigestion), shortness of breath, hypoventilation, apnoea, and urinary retention. Fentanyl use has also been associated with aphasia.[40]

Despite being a more potent analgesic, fentanyl tends to induce less nausea, as well as less histamine-mediated itching, than morphine.[41]

Fentanyl may produce more prolonged respiratory depression than other opioid analgesics.[42][43][44][45][46][47][48] In 2006 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began investigating several respiratory deaths, but doctors in the United Kingdom were not warned of the risks with fentanyl until September 2008.[49] The FDA reported in April 2012 that twelve young children had died and twelve more made seriously ill from separate accidental exposures to fentanyl skin patches.[50]

The precise reason for sudden respiratory depression is unclear, but there are several hypotheses:

- Saturation of the body fat compartment in patients with rapid and profound body fat loss (patients with cancer, cardiac or infection-induced cachexia can lose 80% of their body fat).

- Early carbon dioxide retention causing cutaneous vasodilation (releasing more fentanyl), together with acidosis, which reduces protein binding of fentanyl, releasing yet more fentanyl.

- Reduced sedation, losing a useful early warning sign of opioid toxicity and resulting in levels closer to respiratory-depressant levels.

Fentanyl has a therapeutic index of 270.[51]

Overdose

In July 2014, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) of the UK issued a warning about the potential for life-threatening harm from accidental exposure to transdermal fentanyl patches, particularly in children,[53] and advised that they should be folded, with the adhesive side in, before being discarded. The patches should be kept away from children, who are most at risk from fentanyl overdose.[54]

Death from fentanyl overdose was declared a public health crisis in Canada in September 2015, and it continues to be a significant public health issue.[55] In 2016, deaths from fatal fentanyl overdoses in British Columbia, Canada, averaged two persons per day.[56] In 2017 the death rate rose over 100% with 368 overdose related deaths in British Columbia between January and April 2017.[57]

Medical examiners concluded that musician Prince died on April 21, 2016, from an accidental fentanyl overdose.[58] Fentanyl was among many substances identified in counterfeit pills recovered from his home, especially some that were mislabeled as Watson 385, a combination of hydrocodone and paracetamol.[58][59] American rapper Lil Peep also died of an accidental fentanyl overdose on November 15, 2017.[60][61] On January 19, 2018, the medical examiner-coroner for the county of Los Angeles announced that Tom Petty died from an accidental drug overdose as a result of mixing medications that included fentanyl, acetyl fentanyl and despropionyl fentanyl (among others). He was reportedly treating "many serious ailments" that included a broken hip.[62]

In the US, Fentanyl caused 20,100 deaths in 2016, a rise of 540% over the past 3 years.[63][52]

Pharmacology

Fentanyl provides some of the effects typical of other opioids through its agonism of the opioid receptors. Its strong potency in relation to that of morphine is largely due to its high lipophilicity, per the Meyer-Overton correlation. Because of this, it can more easily penetrate the central nervous system.[41]

Detection in biological fluids

Fentanyl may be measured in blood or urine to monitor for abuse, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Commercially available immunoassays are often used as initial screening tests, but chromatographic techniques are generally used for confirmation and quantitation. Blood or plasma fentanyl concentrations are expected to be in a range of 0.3–3.0 μg/l in persons using the medication therapeutically, 1–10 μg/l in intoxicated patients and 3-300 μg/l in victims of acute overdosage.[64]

History

Fentanyl was first synthesized by Paul Janssen under the label of his relatively newly formed Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1959.[65] The widespread use of fentanyl triggered the production of fentanyl citrate (the salt formed by combining fentanyl and citric acid in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio),[66] which entered medical use as a general anaesthetic under the trade name Sublimaze in the 1960s.[citation needed]

In the mid-1990s, Janssen Pharmaceutica developed and introduced into clinical trials the Duragesic patch, which is a formation of an inert alcohol gel infused with select fentanyl doses, which are worn to provide constant administration of the opioid over a period of 48 to 72 hours. After a set of successful clinical trials, Duragesic fentanyl patches were introduced into medical practice.

Following the patch, a flavoured lollipop of fentanyl citrate mixed with inert fillers was introduced in 1998 under the brand name of Actiq, becoming the first quick-acting formation of fentanyl for use with chronic breakthrough pain.[67]

In 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Onsolis (fentanyl buccal soluble film), a fentanyl drug in a new dosage form for cancer pain management in opioid-tolerant subjects.[68] It uses a medication delivery technology called BEMA (BioErodible MucoAdhesive), a small dissolvable polymer film containing various fentanyl doses applied to the inner lining of the cheek.[68]

Fentanyl has a US DEA ACSCN of 9801 and a 2013 annual aggregate manufacturing quota of 2,108.75 kg, unchanged from the prior year.

Society and culture

Brand names

Brand names include Sublimaze,[40] Actiq, Durogesic, Duragesic, Fentora, Matrifen, Haldid, Onsolis,[69] Instanyl,[70] Abstral,[71] Lazanda[72] and others.[73] Subsys is a sublingual spray of fentanyl manufactured by Insys Therapeutics.[74]

Cost

The wholesale cost in the developing world as of 2015 is between US$0.08 and US$0.81 per 100 microgram vial.[12] In the United States this amount costs about US$0.40 as of 2017.[13] In the United States the patches cost US$11.22 for a 12 µg/hr version and US$8.74 for a 100 µg/hr version.[13]

Legal status

In the UK, fentanyl is classified as a controlled Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.[75]

In the Netherlands, fentanyl is a List I substance of the Opium Law.

In the U.S., fentanyl is a Schedule II controlled substance per the Controlled Substance Act. Distributors of Abstral are required to implement an FDA-approved risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program.[76][77] In order to curb misuse, many health insurers have begun to require precertification and/or quantity limits for Actiq prescriptions.[78][79][80]

Legal action

On June 19, 2007, a $5.5 million jury verdict was awarded in a US case against Johnson & Johnson subsidiaries, Alza Corporation and Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, the manufacturers of the Duragesic fentanyl transdermal pain patch. This case, the first Federal trial involving the Duragesic fentanyl patch, was tried in the Federal District Court for the Southern District of Florida, West Palm Beach Division.

Public health advisories

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued public health advisories related to fentanyl patch dangers. Among these, in July 2005, the FDA issued a Public Health Advisory,[81] which advised that "deaths and overdoses have occurred in patients using both the brand name product Duragesic and the generic product." In December 2007, as part of this continuing investigation, the FDA issued a second Public Health Advisory[81] stating, "The FDA has continued to receive reports of deaths and life-threatening side effects in patients who use the fentanyl patch. The reports indicate that doctors have inappropriately prescribed the fentanyl patch... In addition, the reports indicate that patients are continuing to incorrectly use the fentanyl patch..."

Recreational use

Illicit use of pharmaceutical fentanyl and its analogues first appeared in the mid-1970s in the medical community and continues in the present. More than 12 different analogues of fentanyl, all unapproved and clandestinely-produced, have been identified in the U.S. drug traffic. The biological effects of the fentanyl analogues are similar to those of heroin, with the exception that many users report a noticeably less euphoric high associated with the drug and stronger sedative and analgesic effects.[citation needed]

Fentanyl analogues may be hundreds of times more potent than street heroin, and tend to produce significantly more respiratory depression, making it much more dangerous than heroin to users. Fentanyl is used orally, smoked, snorted, or injected. Fentanyl is sometimes sold as heroin or oxycodone, often leading to overdoses. Many fentanyl overdoses are initially classified as heroin overdoses.[83] The recreational use is not particularly widespread in the EU with the exception of Tallinn, Estonia, where it has largely replaced heroin. Estonia has the highest rate of 3-methylfentanyl overdose deaths in the EU, due to its high rate of recreational use.[84]

Fentanyl is sometimes sold on the black market in the form of transdermal fentanyl patches such as Duragesic, diverted from legitimate medical supplies. The gel from inside the patches may be ingested or injected.[85]

Another form of fentanyl that has appeared on the streets is the Actiq lollipop formulation. The pharmacy retail price ranges from $15 to $50 per unit based on the strength of the lozenge, with the black market cost ranging from $5 to $25, depending on the dose.[86] The attorneys general of Connecticut and Pennsylvania have launched investigations into its diversion from the legitimate pharmaceutical market, including Cephalon's "sales and promotional practices for Provigil, Actiq and Gabitril".[86]

Non-medical use of fentanyl by individuals without opiate tolerance can be very dangerous and has resulted in numerous deaths.[85] Even those with opiate tolerances are at high risk for overdoses. Once the fentanyl is in the user's system, it is extremely difficult to stop its course because of the nature of absorption. Illicitly synthesized fentanyl powder has also appeared on the United States market. Because of the extremely high strength of pure fentanyl powder, it is very difficult to dilute appropriately, and often the resulting mixture may be far too strong and, therefore, very dangerous.[citation needed]

Some heroin dealers mix fentanyl powder with heroin to increase potency or compensate for low-quality heroin. In 2006, illegally manufactured, non-pharmaceutical fentanyl often mixed with cocaine or heroin caused an outbreak of overdose deaths in the United States and Canada, heavily concentrated in the cities of Dayton, Ohio; Chicago; Detroit; and Philadelphia.[87]

Several large quantities of illicitly produced fentanyl have been seized by U.S. law enforcement agencies. In June 2006, 945 grams (2.08 lbs) of 83%-pure fentanyl powder was seized by Border Patrol agents in California from a vehicle that had entered from Mexico.[88] Mexico is the source of much of the illicit fentanyl for sale in the U.S. However, in April 2006, there was one domestic fentanyl lab discovered by law enforcement in Azusa, California. The lab was a source of counterfeit 80 mg OxyContin tablets containing fentanyl instead of oxycodone, as well as bulk fentanyl and other drugs.[89][90] In November 2016, the DEA uncovered an operation making counterfeit oxycodone and Xanax from a home in Cottonwood Heights, Utah. They found about 70,000 pills in the appearance of oxycodone and more than 25,000 in the appearance of Xanax. The DEA reported that millions of pills could have been distributed from this location over the course of time. The accused owned a pill press and ordered fentanyl in powder form from China.[91][92]

The "China White" form of fentanyl refers to any of a number of clandestinely produced analogues, especially α-methylfentanyl (AMF).[93] This Department of Justice document lists "China White" as a synonym for a number of fentanyl analogues, including 3-methylfentanyl and α-methylfentanyl,[94] which today are classified as Schedule I drugs in the United States.[93] Part of the motivation for AMF is that, despite the extra difficulty from a synthetic standpoint, the resultant drug is relatively more resistant to metabolic degradation. This results in a drug with an increased duration.[95]

In June 2013, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a health advisory[96] to emergency departments alerting to 14 overdose deaths among intravenous drug users in Rhode Island associated with acetylfentanyl, a synthetic opioid analog of fentanyl that has never been licensed for medical use. In a separate study conducted by the CDC, 82% of fentanyl overdose deaths involved illegally manufactured fentanyl, while only 4% were suspected to originate from a prescription.[97]

Beginning in 2015, Canada has seen a widespread number of fentanyl overdoses. Authorities suspect that the drug is being imported from Asia to the western coast by organized crime groups in powder form and being pressed into pseudo-OxyContin tablets.[98] Traces of the drug have also been found in other recreational drugs including cocaine, MDMA, and heroin. The drug has been implicated in multiple deaths from the homeless to young professionals, including multiple teens and young parents.[99] Because of the rising deaths across the country, especially in British Columbia where the deaths for 2016 is 668 and deaths for 2017 (January to October) is 999,[100]Health Canada is putting a rush on a review of the prescription-only status of naloxone in an effort to combat overdoses of the drug.[101]

Fentanyl has been discovered for sale in illicit markets in Australia in 2017[102] and in New Zealand in 2018.[103] In response, New Zealand experts called for wider availability of naloxone.[104]

Incapacitating agent

Russian spetsnaz security forces used a "fentanyl gas" to incapacitate people rapidly in the Moscow theater hostage crisis in 2002. The siege was ended, but about 130 of the 850 hostages died from the gas. The Russian Health Minister later stated that the gas was based on fentanyl,[105] but the exact chemical agent has not been identified.

Veterinary use

Fentanyl in injectable formulation is commonly used for analgesia and as a component of balanced sedation and general anaesthesia in small animal patients. Its potency and short duration of action make it particularly useful in critically ill patients. In addition, it tends to cause less vomiting and regurgitation than other pure-opioid agonists (morphine, hydromorphone) when given as a continuous post-operative infusion. As with other pure opioids, fentanyl can be associated with dysphoria in both dogs and cats.

Transdermal fentanyl has also been used for many years in dogs and cats for post-operative analgesia. This is usually done with off-label fentanyl patches manufactured for humans with chronic pain. In 2012 a highly concentrated (50 mg/ml) transdermal solution, trade name Recuvyra, has become commercially available for dogs only. It is FDA approved to provide four days of analgesia after a single application prior to surgery. It is not approved for multiple doses or other species.[106] The drug is also approved in Europe.[107]

See also

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b Clinically Oriented Pharmacology (2 ed.). Quick Review of Pharmacology. 2010. p. 172.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Fentanyl, Fentanyl Citrate, Fentanyl Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Guideline for administration of fentanyl for pain relief in labour" (PDF). RCP. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

Onset of action after IV administration of Fentanyl is 3–5 minutes; duration of action is 30–60 minutes.

- ^ "DrugFacts: Fentanyl". National Institute on Drug Abuse, US National Institutes of Health. June 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "Commission on Narcotic Drugs takes decisive step to help prevent deadly fentanyl overdoses". Commission on Narcotic Drugs, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Stanley TH (April 1992). "The history and development of the fentanyl series". J Pain Symptom Manage. 7 (3 Suppl): S3–7. doi:10.1016/0885-3924(92)90047-L. PMID 1517629.

- ^ Black J (March 2005). "A personal perspective on Dr. Paul Janssen" (PDF). J. Med. Chem. 48 (6): 1687–8. doi:10.1021/jm040195b. PMID 15771410. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Narcotic Drugs Estimated World Requirements for 2017 Statistics for 2015 (PDF). New York: United Nations. 2016. p. 40. ISBN 978-92-1-048163-2. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "Fentanyl And Analogues". LiverTox. 16 October 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (20th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 2017. p. 2. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Single Drug Information". International Medical Products Price Guide. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "NADAC as of 2017-12-13". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "Fentanyl Drug Overdose". CDC Injury Center. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "Overdose Death Rates". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 15 September 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Godwin, SA; Burton, JH; Gerardo, CJ; Hatten, BW; Mace, SE; Silvers, SM; Fesmire, FM; American College of Emergency, Physicians (February 2014). "Clinical policy: procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 63 (2): 247–58.e18. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.10.015. PMID 24438649.

- ^ Smith, HS; Colson, J; Sehgal, N (April 2013). "An update of evaluation of intravenous sedation on diagnostic spinal injection procedures". Pain Physician. 16 (2 Suppl): SE217–28. PMID 23615892.

- ^ Plante, GE; VanItallie, TB (October 2010). "Opioids for cancer pain: the challenge of optimizing treatment". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 59 Suppl 1: S47–52. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2010.07.010. PMID 20837194.

- ^ Bujedo, BM (July 2014). "Current evidence for spinal opioid selection in postoperative pain". The Korean journal of pain. 27 (3): 200–9. doi:10.3344/kjp.2014.27.3.200. PMC 4099232. PMID 25031805.

- ^ a b c Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 2621f. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ^ Derry, Sheena; Stannard, Cathy; Cole, Peter; Wiffen, Philip J.; Knaggs, Roger; Aldington, Dominic; Moore, R. Andrew (2016-10-11). "Fentanyl for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD011605. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011605.pub2. PMID 27727431.

- ^ a b "Official Duragesic Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Disposal of Unused Medicines: What You Should Know". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "Medicines Recommended for Disposal by Flushing". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "Medication Guide and Instructions for Use – Duragesic (fentanyl) Transdermal System" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "PRICARA RECALLS 25 mcg/hr DURAGESIC (fentanyl transdermal system) CII PAIN PATCHES". FDA. 2008-02-12.

- ^ Karlsen, A. P.; Pedersen, D. M.; Trautner, S; Dahl, J. B.; Hansen, M. S. (2014). "Safety of intranasal fentanyl in the out-of-hospital setting: A prospective observational study". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 63 (6): 699–703. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.10.025. PMID 24268523.

- ^ Murphy A, O'Sullivan R, Wakai A, Grant TS, Barrett MJ, Cronin J, McCoy SC, Hom J, Kandamany N (Oct 10, 2014). "Intranasal fentanyl for the management of acute pain in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD009942. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009942.pub2. PMID 25300594.

- ^ a b c "Abstral Sublingual Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. May 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ "Abstral (Fentanyl Sublingual Tablets for Breakthrough Cancer Pain)". P T. 36 (2): 2–28. February 2011. PMC 3086091. PMID 21560267.

- ^ Ward, J.; Laird, B.; Fallon, M. (1 April 2011). "The UK breakthrough cancer pain registry: origin, methods and preliminary data". BMJ Support Palliat Care. 1 (Suppl 1): A24–A24. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000020.71 – via spcare.bmj.com.

- ^ a b Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 89–92. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ^ O'Connor AB (2008). "Is actiq use in noncancer-related pain really "a recipe for success"?". Pain Medicine. 9 (2): 258–60, author reply 261–5. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00413.x. PMID 18298711.

- ^ "Actiq (fentanyl citrate) Uses, Dosage, Side Effects - Drugs.com".

- ^ Fentanyl citrate (oral transmucosal) (FEN ta nil SIT rayt). "Actiq". drugs.com.

- ^ "Barr Launches Generic ACTIQ(R) Cancer Pain Management Product – LifeSciencesWorld".

- ^ Shachtman, Noah (September 10, 2009). "Airborne EMTs Shave Seconds to Save Lives in Afghanistan". Danger Room. Wired. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Murphy A, O'Sullivan R, Wakai A, Grant TS, Barrett MJ, Cronin J, McCoy SC, Hom J, Kandamany N (10 October 2014). "Intranasal fentanyl for the management of acute pain in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD009942. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009942.pub2. PMID 25300594.

- ^ Peter J.S. Koo (2005). "Postoperative Pain Management With a Patient-Controlled Transdermal Delivery System for Fentanyl". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 62 (11): 1171–1176. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b "fentanyl". Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ a b Stacey Mayes, PharmD MS, Marcus Ferrone, PharmD BCNSP, 2006.Fentanyl HCl Patient-Controlled Iontophoretic Transdermal System for Pain: Pharmacology The Annals of Pharmacotherapy.

- ^ Smydo, J. (1979). "Delayed respiratory depression with fentanyl". Anesth Prog. 26 (2): 47–8. PMC 2515983. PMID 295585.

- ^ van Leeuwen, L.; Deen, L.; Helmers, J. H. (August 1981). "A comparison of alfentanil and fentanyl in short operations with special reference to their duration of action and postoperative respiratory depression". Anaesthesist. 30 (8): 397–9. PMID 6116461.

- ^ Brown, D. L. (November 1985). "Postoperative analgesia following thoracotomy. Danger of delayed respiratory depression". Chest. 88 (5): 779–80. doi:10.1378/chest.88.5.779. PMID 4053723.

- ^ Bülow, H. H.; Linnemann, M.; Berg, H.; Lang-Jensen, T.; LaCour, S.; Jonsson, T. (August 1995). "Respiratory changes during treatment of postoperative pain with high dose transdermal fentanyl". Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 39 (6): 835–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1995.tb04180.x. PMID 7484044.

- ^ Nilsson, C.; Rosberg, B. (June 1982). "Recurrence of respiratory depression following neurolept analgesia". Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 26 (3): 240–1. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1982.tb01762.x. PMID 7113633.

- ^ McLoughlin, R.; McQuillan, R. (September 1997). "Transdermal fentanyl and respiratory depression". Palliat Med. 11 (5): 419–421. doi:10.1177/026921639701100515. PMID 9472602.

- ^ Regnard, C.; Pelham, A. (December 2003). "Severe respiratory depression and sedation with transdermal fentanyl: four case studies". Palliat Med. 17 (8): 714–6. PMID 14694924.

- ^ "Fentanyl patches: serious and fatal overdose from dosing errors, accidental exposure, and inappropriate use". Drug Safety Update. 2 (2): 2. September 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-01-01.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Fentanyl Patch Can Be Deadly to Children". U.S. FDA (Drugs.com). April 19, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ^ Stanley, Theodore Henry; Petty, William Clayton (1983-03-31). New Anesthetic Agents, Devices, and Monitoring Techniques. Springer. ISBN 978-90-247-2796-4. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Overdose Death Rates". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 15 September 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "Fentanyl patches warning". Pharmaceutical Journal. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "MHRA warns about fentanyl patches after children exposed". Pharmaceutical Journal. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "Fentanyl Overdose". Huffington Post. May 20, 2016.

- ^ "Fentanyl-Detected in Illicit Drug Overdose Deaths January 1, 2012 to April 30, 2016" (PDF). British Columbia Coroners Service.

- ^ "Fentanyl contributed to hundreds of deaths in Canada so far this year".

- ^ a b Eligon, John; Kovaleski, Serge F. (June 2, 2016). "Prince Died From Accidental Overdose of Opioid Painkiller". The New York Times.

- ^ "Official: Mislabeled pills found at Prince's estate contained fentanyl". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ "Report: Toxic Combo of Prescription Drugs Killed Rapper".

- ^ Brown, August (November 16, 2017). "Lil Peep, hero to the emo and hip-hop scenes, dies of suspected overdose at 21". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ Coscarelli, Joe (2018). "Tom Petty Died From Accidental Drug Overdose Involving Opioids, Coroner Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-01-20.

- ^ Katz, Josh (September 2, 2017). "The First Count of Fentanyl Deaths in 2016- Up 540% in Three Years". The New York Times.

- ^ Baselt, R. (2017) Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 11th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, pp. 883–886.

- ^ Lopez-Munoz, Francisco; Alamo, Cecilio (2009). "The Consolidation of Neuroleptic Therapy: Janssen, the Discovery of Haloperidol and Its Introduction into Clinical Practice". Brain Research Bulletin. 79 (2): 130–141. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.01.005. PMID 19186209.

- ^ "DailyMed: About DailyMed". Dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ^ "ACTIQ® (fentanyl citrate) oral transmucosal lozenge (1968 version revised in 2011)" (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. December 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Questions and Answers about Onsolis (fentanyl buccal soluble film)". US Food and Drug Administration. 16 July 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "Introducing Onsolis". Onsolis.com. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ^ "EPAR summary for the public: Instanyl" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ^ "Abstral: Prescribing Information". Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ^ "Lazanda (fentanyl nasal spray) CII". Lazanda.com. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ^ "Fentanyl". International Drug Names. Drugs.com.

- ^ Worstall, Tim (11 May 2014). "The Short Case For Insys Therapeutics". Forbes. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ "Misuse of Drugs Act 1971".

- ^ "RelayHealth's pharmacy connectivity network and reach, aligned with McKesson Specialty Care Solutions' REMS expertise, expands cancer patients' access to pain therapy". Atlanta. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Shelley, Suzanne (22 April 2011). "With a Few Stumbles, REMS Begins to Hit Its Stride". Pharmaceutical Commerce. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Aetna notice regarding precertification requirement[permanent dead link]", Aetna, May, 2007

- ^ "BlueCross BlueShield of Arizona notice regarding precertification requirement Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine", BlueCross BlueShield of Arizona, November 5, 2007

- ^ "Medications Requiring Precertification Archived October 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine", Oxford Health Plans

- ^ a b "Fentanyl Transdermal System (marketed as Duragesic) Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "DEA Microgram Bulletin, June 2006". US Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Forensic Sciences Washington, D.C. 20537. June 2006. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Boddiger, D. (2006, August 12).Fentanyl-laced street drugs "kill hundreds". The Lancet. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ "Synthetic drug fentanyl causes overdose boom in Estonia". BBC News. 30 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Fentanyl" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration. March 2015.

- ^ a b "Painkiller is topic of inquiry", Bob Mims, The Salt Lake Tribune, 11 November 2004

- ^ "CDC Nonpharmaceutical Fentanyl-Related Deaths – Multiple States, April 2005 – March 2007". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ^ Intelligence alert: High purity fentanyl seized near Westmoreland, California Archived 2009-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, DEA Microgram, June 2006

- ^ Intelligence alert: Large fentanyl / MDA / TMA laboratory in Azuza, California – possibly the "OC-80" tablet source Archived 2006-09-02 at the Wayback Machine, DEA Microgram, April 2006.

- ^ Intelligence alert: Oxycontin mimic tablets (containing fentanyl) near Atlantic, Iowa Archived 2006-08-20 at the Wayback Machine, DEA Microgram, January 2006.

- ^ Tribune, Courtney Tanner. "Thousands of fentanyl pills confiscated in Utah drug raid". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ^ "Cottonwood Heights drug bust one of the largest in Utah history". fox13now.com. 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ^ a b List of Schedule I Drugs, U.S. Department of Justice. Archived January 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Behind the Identification of China White Analytical Chemistry, 53(12), 1379A–1386A (1981)

- ^ Van Bever, Willem F. M.; Niemegeers, Carlos J. E.; Janssen, Paul A. J. (October 1974). "Synthetic analgesics. Synthesis and pharmacology of the diastereoisomers of N-(3-methyl-1-(2-phenylethyl)-4-piperidyl)-N-phenylpropanamide and N-(3-methyl-1-(1-methyl-2-phenylethyl)-4-piperidyl)-N-phenylpropanamide". J. Med. Chem. 17 (10): 1047–51. doi:10.1021/jm00256a003. PMID 4420811.

- ^ CDC Health Alert Network (June 20, 2013). "Recommendations for Laboratory Testing for Acetyl Fentanyl and Patient Evaluation and Treatment for Overdose with Synthetic Opioids". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Characteristics of Fentanyl Overdose — Massachusetts, 2014–2016 (Report). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 14, 2017.

- ^ Lethal fentanyl profiting gangs in Western Canada while deaths climb, Metro News Edmonton, August 6, 2015.

- ^ Fentanyl doesn’t discriminate, killing the homeless and young professionals, Edmonton Journal, August 22, 2015.

- ^ "Fentanyl - Detected Illicit Drug Overdose Deaths" (PDF). British Columbia Government.

- ^ "Winnipeg Naloxone-distribution program could prevent fentanyl deaths | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Bonini, Tierney (13 October 2017). "Could fentanyl be Australia's next deadly drug epidemic?". ABC News. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Fentanyl found at New Zealand festival". KnowYourStuffNZ. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Buchanan, Julian. "NZ's 'deadly' indifference to drug overdose antidote". HealthCentral NZ. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Russia names Moscow Siege Gas". BBC. October 31, 2002.

- ^ "Original new animal drug application: Recuvyra" (PDF).

- ^ "European Medicines Agency – Veterinary medicines – Recuvyra". Retrieved 28 March 2016.