COVID-19

Template:Use Commonwealth English

| Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| |

| Microscopy image showing SARS-CoV-2. The spikes on the outer edge of the virus particles resemble a crown, giving the disease its characteristic name. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Acute respiratory infection[5] |

| Symptoms | Fever, cough, shortness of breath[6] |

| Complications | Pneumonia, ARDS, kidney failure |

| Causes | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Risk factors | Not taking preventative measures |

| Diagnostic method | rRT-PCR testing, immunoassay, CT scan |

| Prevention | Correct handwashing technique, cough etiquette, avoiding close contact with sick people or subclinical carriers |

| Treatment | Symptomatic and supportive |

| Frequency | 676,609,955[7] confirmed cases since 30 December 2019 |

| Deaths | 6,881,955[7] (3.4% of confirmed cases; significantly lower when non-reported cases are included[8][9]) |

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).[10] The disease was first identified in 2019 in Wuhan, China, and has spread globally, resulting in the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic.[11][12] Common symptoms include fever, cough and shortness of breath. Muscle pain, sputum production and sore throat are less common symptoms.[6][13] While the majority of cases result in mild symptoms,[14] some progress to pneumonia and multi-organ failure.[11][15] The deaths per number of diagnosed cases is estimated at between 1% and 5% but varies by age and other health conditions.[16][17]

The infection is spread from one person to others via respiratory droplets, often produced during coughing and sneezing.[18][19] Time from exposure to onset of symptoms is generally between 2 and 14 days, with an average of 5 days.[20][21] The standard method of diagnosis is by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) from a nasopharyngeal swab or throat swab. The infection can also be diagnosed from a combination of symptoms, risk factors and a chest CT scan showing features of pneumonia.[22][23]

Recommended measures to prevent the disease include frequent hand washing, maintaining distance from other people and not touching one's face.[24] The use of masks is recommended for those who suspect they have the virus and their caregivers, but not the general public.[25][26] There is no vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for COVID-19; management involves treatment of symptoms, supportive care, isolation and experimental measures.[27]

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the 2019–20 coronavirus outbreak a pandemic[12] and a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).[28][29] Evidence of local transmission of the disease has been found in many countries across all six WHO regions.[30]

Signs and symptoms

| Symptom | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Fever | 87.9% |

| Dry cough | 67.7% |

| Fatigue | 38.1% |

| Sputum production | 33.4% |

| Shortness of breath | 18.6% |

| Muscle pain or joint pain | 14.8% |

| Sore throat | 13.9% |

| Headache | 13.6% |

| Chills | 11.4% |

| Nausea or vomiting | 5.0% |

| Nasal congestion | 4.8% |

| Diarrhoea | 3.7% |

| Haemoptysis | 0.9% |

| Conjunctival congestion | 0.8% |

Those infected with the virus may either be asymptomatic or develop flu-like symptoms that include fever, cough and shortness of breath.[6][32][33] Diarrhoea and upper respiratory symptoms such as sneezing, runny nose, or sore throat are less common.[34] Cases can progress to pneumonia, multi-organ failure and death in the most vulnerable.[11][15]

The incubation period ranges from two to 14 days, with an estimated median incubation period of five to six days, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).[35][36] The median time from onset to clinical recovery for mild cases is approximately 2 weeks and is 3-6 weeks for people with severe or critical disease. Preliminary data suggests that the time period from onset to the development of severe disease, including hypoxia, is 1 week. Among people who have died, the time from symptom onset to outcome ranges from 2-8 weeks.[37]

One study in China found that CT scans showed ground-glass opacities in 56%, but 18% had no radiological findings. 5% were admitted to intensive care units, 2.3% needed mechanical support of ventilation and 1.4% died.[38] Bilateral and peripheral ground glass opacities are the most typical CT findings.[39] Consolidation, linear opacities and reverse halo sign are other radiological findings.[39] Initially, the lesions are confined to one lung, but as the disease progresses, indications manifest in both lungs in 88% of so-called "late patients" in the study group (the subset for whom time between onset of symptoms and chest CT was 6–12 days).[39]

It has been noted that children seem to have milder symptoms than adults.[40]

Cause

The disease is caused by the virus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), previously referred to as the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV).[41] It is primarily spread between people via respiratory droplets from coughs and sneezes.[19]

Lungs are the organs most affected by COVID-19 because the virus accesses host cells via the enzyme ACE2, which is most abundant in the type II alveolar cells of the lungs. The virus uses a special surface glycoprotein, called "spike", to connect to ACE2 and intrude the hosting cell.[42] The density of ACE2 in each tissue correlates with the severity of the disease in that tissue and some have suggested that decreasing ACE2 activity might be protective,[43][44] though another view is that increasing ACE2 using Angiotensin II receptor blocker drugs could be protective and that these hypotheses need to be tested.[45] As the alveolar disease progresses respiratory failure might develop and death might ensue.[44] ACE2 might also be the path for the virus to assault the heart causing acute cardiac injury. People with existing cardiovascular conditions have worst prognosis.[46]

The virus is thought to have an animal origin,[47] through spillover infection.[48] It was first transmitted to humans in Wuhan, China, in November or December 2019, and the primary source of infection became human-to-human transmission by early January 2020.[49][50] On 14 March 2020, South China Morning Post reported that a 55-year-old from Hubei province could have been the first person to have contracted the disease on 17 November 2019.[51] As of 14 March 2020, 67,790 cases and 3,075 deaths due to the virus have been reported in Hubei province; a case fatality rate (CFR) of 4.54%.[51]

Diagnosis

The WHO has published several testing protocols for the disease.[53] The standard method of testing is real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR).[54] The test can be done on respiratory samples obtained by various methods, including a nasopharyngeal swab or sputum sample.[55] Results are generally available within a few hours to 2 days.[56][57] Blood tests can be used, but these require two blood samples taken two weeks apart and the results have little immediate value.[58] Chinese scientists were able to isolate a strain of the coronavirus and publish the genetic sequence so that laboratories across the world could independently develop polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests to detect infection by the virus.[11][59][60]

As of 26 February 2020, there were no antibody tests or point-of-care tests though efforts to develop them are ongoing.[61]

Diagnostic guidelines released by Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University suggested methods for detecting infections based upon clinical features and epidemiological risk. These involved identifying people who had at least two of the following symptoms in addition to a history of travel to Wuhan or contact with other infected people: fever, imaging features of pneumonia, normal or reduced white blood cell count, or reduced lymphocyte count.[22] A study published by a team at the Tongji Hospital in Wuhan on 26 February 2020 showed that a chest CT scan for COVID-19 has more sensitivity (98%) than the polymerase chain reaction (71%).[23] False negative results may occur due to PCR kit failure, or due to either issues with the sample or issues performing the test. False positive results are likely to be rare.[62]

-

Typical CT imaging findings

-

CT imaging of rapid progression stage

Prevention

Because a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 is not expected to become available until 2021 at the earliest,[68] a key part of managing the COVID-19 pandemic is trying to decrease the epidemic peak, known as flattening the epidemic curve.[64] This helps decrease the risk of health services being overwhelmed and provides more time for a vaccine and treatment to be developed.[64]

Preventive measures to reduce the chances of infection in locations with an outbreak of the disease are similar to those published for other coronaviruses: stay home, avoid travel and public activities, wash hands with soap and hot water often, practice good respiratory hygiene and avoid touching the eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands.[69][70] Social distancing strategies aim to reduce contact of infected persons with large groups by closing schools and workplaces, restricting travel and canceling mass gatherings.

According to the WHO, the use of masks is only recommended if a person is coughing or sneezing or when one is taking care of someone with a suspected infection.[71]

To prevent transmission of the virus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States recommends that infected individuals stay home except to get medical care, call ahead before visiting a healthcare provider, wear a face mask when exposed to an individual or location of a suspected infection, cover coughs and sneezes with a tissue, regularly wash hands with soap and water and avoid sharing personal household items.[72][73] CDC also recommends that individuals wash hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after going to the toilet or when hands are visibly dirty, before eating and after blowing one's nose, coughing, or sneezing. It further recommended using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol, but only when soap and water are not readily available.[69] The WHO advises individuals to avoid touching the eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands.[70] Spitting in public places also should be avoided.[74]

Management

There are no specific antiviral medications. People are managed with supportive care such as fluid and oxygen support.[76][77] The WHO and Chinese National Health Commission have published treatment recommendations for taking care of people who are hospitalised with COVID-19.[78][79] Steroids such as methylprednisolone are not recommended unless the disease is complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome.[80][81] Intensivists and pulmonologists in the US have compiled treatment recommendations from various agencies into a free resource, the IBCC.[82][83] The CDC recommends that those who suspect they carry the virus wear a simple face-mask.[25]

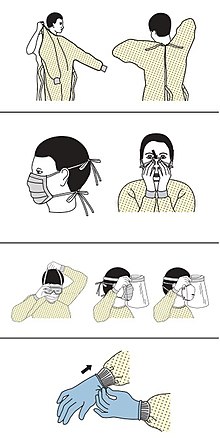

Personal protective equipment

Management of people infected by the virus includes taking precautions while applying therapeutic manoeuvres, especially when performing procedures like intubation or hand ventilation that can generate aerosols.[84]

The CDC outlines the specific personal protective equipment and the order in which healthcare providers should put it on when dealing with someone who may have COVID-19: 1) gown, 2) mask or respirator [1], 3) goggles or a face shield, 4) gloves.[85][86]

Mechanical ventilation

Most cases of COVID-19 are not severe enough to require mechanical ventilation (artificial assistance to support breathing), but a percentage of cases do. This is most common in older adults (those older than 60 years and especially those older than 80 years). This component of treatment is the biggest rate-limiter of health system capacity that drives the need to flatten the curve (to keep the speed at which new cases occur and thus the number of people sick at one point in time lower). This is why social distancing is so important to saving the lives of others, not just to preserving one's own. This fact falsifies the argument that a young healthy adult can ignore the need for social distancing, accept a mild flu-like illness, recover, and move on. The burden on the healthcare system will also limit the availability of other types of health care, such as that required after a motor vehicle collision.

Experimental treatment

Antiviral medication may be tried in people with severe disease.[76] The WHO recommended volunteers take part in trials of the effectiveness and safety of potential treatments.[87] There is tentative evidence for remdesivir as of March 2020.[88] Lopinavir/ritonavir is also being studied in China.[89] Chloroquine was being trialled in China in February 2020, with preliminary results that seem positive.[90] Nitazoxanide has been recommended for further in vivo study after demonstrating low concentration inhibition of SARS-CoV-2.[91]

Tocilizumab, an immunosuppressive drug, mainly used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, has been included in treatment guidelines by China's National Health Commission after a completed small study by the University of Science and Technology of China.[92][93] The drug is undergoing testing in five hospitals in Italy after showing positive results in people with severe disease.[94][95] Combined with a serum ferritin blood test to identify cytokine storms, it is meant to counter such developments which are thought to be the cause of death in some patients.[96][97] The interleukin-6 receptor antagonist was approved by the FDA for treatment against cytokine release syndrome induced by a different cause, CAR T cell therapy, in 2017.[98]

Information technology

In February 2020, China launched a mobile app to deal with the disease outbreak.[99] Users are asked to enter their name and ID number. The app is able to detect 'close contact' using surveillance data and therefore a potential risk of infection. Every user can also check the status of three other users. If a potential risk is detected, the app not only recommends self-quarantine, it also alerts local health officials.[100]

Psychological support

Infected individuals may experience distress from quarantine, travel restrictions, side effects of treatment, or fear of the infection itself. To address these concerns, the National Health Commission of China published a national guideline for psychological crisis intervention on 27 January 2020.[101][102]

Prognosis

Many of those who die of COVID-19 have preexisting conditions, including hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.[103] In a study of early cases, the median time from exhibiting initial symptoms to death was 14 days, with a full range of 6 to 41 days.[104] In a study by the National Health Commission (NHC) of China, men had a death rate of 2.8% while women had a death rate of 1.7%.[105] In those younger than 50 years, the risk of death is less than 0.5%, while in those older than 70 it is more than 8%.[105] No deaths had occurred in people younger than 10 as of 26 February 2020[update].[105] Availability of medical resources and the socioeconomics of a region may also affect mortality.[106]

Histopathological examinations of post-mortem lung samples showed diffuse alveolar damage with cellular fibromyxoid exudates in both lungs. Viral cytopathic changes were observed in the pneumocytes. The lung picture resembled acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[107]

It is unknown if past infection provides effective and long-term immunity in people who recover from the disease.[108] Immunity is likely, based on the behaviour of other coronaviruses,[109] but some cases of someone recovering and later testing positive again have been reported in various countries.[110][111] It is unclear if those cases are the result of reinfection, relapse, or testing error; more research is needed about how the SARS-CoV-2 virus interacts with the human immune system.

| Age | 80+ | 70–79 | 60–69 | 50–59 | 40–49 | 30–39 | 20–29 | 10–19 | 0–9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China as of 11 February[112] | 14.8 | 8.0 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Italy as of 12 March[113] | 16.9 | 9.6 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| South Korea as of 15 March[114] | 9.5 | 5.3 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

-

The severity of diagnosed COVID19 cases in China[115]

-

Case fatality rates by age group in China. Data through 11 February 2020.[116]

-

Case fatality rate depending on other health problems

Long-term health consequences

On 12 March, the Hong Kong Hospital Authority announced they had found a drop of 20% to 30% in lung capacity in two to three of around a dozen people who had recovered from the disease. The people who recovered gasp if they walk more quickly. Lung scans of the nine people infected at Princess Margaret Hospital suggested they had sustained organ damage.[117]

Epidemiology

The case fatality rate (CFR) depends on the availability of healthcare, the typical age and health problems within the population, and the number of undiagnosed cases.[118][119] Preliminary research has yielded case fatality rate numbers between 2% and 3%;[16] in January 2020 the WHO suggested that the case fatality rate was approximately 3%,[120] and 2% in February 2020 in Hubei.[121] Other CFR numbers, which adjust for differences in time of confirmation, death or cured, are respectively 7%[122] and 33% for people in Wuhan 31 January.[123] An unreviewed preprint of 55 deaths noted that early estimates of mortality may be too high as asymptomatic infections are missed. They estimated a mean infection fatality ratio (IFR, the mortality among infected) ranging from 0.8% - 0.9%.[124] The outbreak in 2019–2020 has caused at least 676,609,955Template:Edit sup[7] confirmed infections and 6,881,955Template:Edit sup[7] deaths.

An observational study of nine people, found no vertical transmission from mother to the newborn.[125] Also, a descriptive study in Wuhan found no evidence of viral transmission through vaginal sex (from female to partner), but authors note that transmission during sex might occur through other routes.[126]

Research

Because of its key role in the transmission and progression of the disease, ACE2 has been the focus of a significant proportion of research and various therapeutic approaches have been suggested.[44]

Vaccine

There is no available vaccine, but research into developing a vaccine has been undertaken by various agencies. Previous work on SARS-CoV is being utilised because SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV both use ACE2 enzyme to invade human cells.[127] There are three vaccination strategies being investigated. First, researchers aim to build a whole virus vaccine. The use of such a virus, be it inactive or dead, aims for a prompt immune response of the human body to a new infection with COVID-19. A second strategy, subunit vaccines, aims to create a vaccine that sensitises the immune system to certain subunits of the virus. In the case of SARS-CoV-2 such research focuses on the S-spike protein that helps the virus intrude the ACE2 enzyme. A third strategy is the nucleic acid vaccines (DNA or RNA vaccines, a novel technique for creating a vaccination). Experimental vaccines from any of these strategies would have to be tested for safety and efficacy.[128]

Antiviral

No medication has yet been approved to treat coronavirus infections in humans by the WHO although some are recommended by the Korean and Chinese medical authorities.[129] Trials of many antivirals have been started in COVID-19 including oseltamivir, lopinavir/ritonavir, ganciclovir, favipiravir, baloxavir marboxil, umifenovir, and interferon alfa but currently there are no data to support their use.[130] Korean Health Authorities recommend lopinavir/ritonavir or chloroquine[131] and the Chinese 7th edition guidelines include interferon, lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin, chloroquine and/or umifenovir.[132]

Research into potential treatments for the disease was initiated in January 2020, and several antiviral drugs are already in clinical trials.[133][134] Although completely new drugs may take until 2021 to develop,[135] several of the drugs being tested are already approved for other antiviral indications, or are already in advanced testing.[129]

Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the coronavirus in vitro.[91] Remdesivir is being trialled in US and in China.[130]

Preliminary results from a multicentric trial, announced in a press conference and described by Gao, Tian and Yang, suggested that chloroquine is effective and safe in treating COVID-19 associated pneumonia, "improving lung imaging findings, promoting a virus-negative conversion, and shortening the disease course".[90]

Recent studies have demonstrated that initial spike protein priming by transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) is essential for entry of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV via interaction with the ACE2 receptor.[136][137] These findings suggest that the TMPRSS2 inhibitor Camostat approved for clinical use in Japan for inhibiting fibrosis in liver and kidney disease, postoperative reflux esophagitis and pancreatitis might constitute an effective off-label treatment option.[136]

Passive antibody therapy

Using blood donations from healthy people who have already recovered from COVID-19 holds promise,[138] a strategy which has also been tried for SARS, an earlier cousin of COVID-19.[138] The mechanism of action is that the antibodies naturally produced in the immune systems of those who have already recovered are transferred to people in need of them via a nonvaccine form of immunization.[138] Such convalescent serum therapy (antiserum therapy) is also analogous to the way that hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) is used to prevent hepatitis B or human rabies immune globulin (HRIG) is used to treat rabies.[138] Other forms of passive antibody therapy, such as with manufactured monoclonal antibodies, may come later after biopharmaceutical development,[138] but convalescent serum production could be increased for quicker deployment.[139]

Terminology

The World Health Organization announced on 11 February 2020 that "COVID-19" would be the official name of the disease. World Health Organization chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said "co" stands for "corona", "vi" for "virus" and "d" for "disease", while "19" was for the year, as the outbreak was first identified on 31 December 2019. Tedros said the name had been chosen to avoid references to a specific geographical location (i.e. China), animal species, or group of people in line with international recommendations for naming aimed at preventing stigmatisation.[140][141]

While the disease is named COVID-19, the virus that causes it was named SARS-CoV-2 by the WHO.[142] The virus was initially referred to as the 2019 novel coronavirus or 2019-nCoV.[143] The WHO additionally uses "the COVID-19 virus" and "the virus responsible for COVID-19" in public communications.[142]

See also

- Coronavirus diseases, a group of closely related syndromes

- Li Wenliang, a doctor at Central Hospital of Wuhan and one of the first to warn others about the disease, from which he later died

- 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic

References

- ^ 国家卫生健康委关于新型冠状病毒肺炎暂命名事宜的通知 (in Chinese (China)). National Health Commission. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Charlie Campbell (20 January 2020). "The Wuhan Pneumonia Crisis Highlights the Danger in China's Opaque Way of Doing Things". Time. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Daniel Lucey and Annie Sparrow (14 January 2020). "China Deserves Some Credit for Its Handling of the Wuhan Pneumonia". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Stobbe, Mike (8 February 2020). "Wuhan coronavirus? 2018 nCoV? Naming a new disease". Fortune. Associated Press. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ See SARS-CoV-2 for more.

- ^ a b c "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States. 10 February 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)". ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200306-sitrep-46-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=96b04adf_2

- ^ World Health Organization (March 2020). "Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 46" (Document). hdl:10665/331443.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, et al. (February 2020). "The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China". Int J Infect Dis. 91: 264–66. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. PMID 31953166.

- ^ a b "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 11 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19)". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 11 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Wang, Vivian (5 March 2020). "Most Coronavirus Cases Are Mild. That's Good and Bad News". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Q&A on coronaviruses". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Wuhan Coronavirus Death Rate". www.worldometers.info. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Report 4: Severity of 2019-novel coronavirus (nCoV)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Q&A on coronaviruses". World Health Organization (WHO). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

The disease can spread from person to person through small droplets from the nose or mouth which are spread when a person with COVID-19 coughs or exhales ... The main way the disease spreads is through respiratory droplets expelled by someone who is coughing.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

The virus is thought to spread mainly from person-to-person ... through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Symptoms of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". www.cdc.gov. 10 February 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Velavan TP, Meyer CG (March 2020). "The COVID-19 epidemic". Tropical Medicine & International Health. n/a (n/a): 278–80. doi:10.1111/tmi.13383. PMID 32052514.

- ^ a b Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, Cheng H, Deng T, Fan YP, et al. (February 2020). "A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version)". Military Medical Research. 7 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. PMC 7003341. PMID 32029004.

- ^ a b "CT provides best diagnosis for COVID-19". ScienceDaily. 26 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Advice for public". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b CDC (11 February 2020). "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Advice for public". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 15 February 2020. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Mahtani S, Berger M, O'Grady S, Iati M (6 February 2020). "Hundreds of evacuees to be held on bases in California; Hong Kong and Taiwan restrict travel from mainland China". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ World Health Organization (March 2020). "Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 47" (Document). hdl:10665/331444.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|website=ignored (help) - ^ World Health Organization. "Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (Document). pp. 11–12.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. (February 2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMID 32007143.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Hessen, Margaret Trexler (27 January 2020). "Novel Coronavirus Information Center: Expert guidance and commentary". Elsevier Connect. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. (February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMID 31986264.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ World Health Organization (19 February 2020). "Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 29" (Document). hdl:10665/331118.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19): How long is the incubation period for COVID-19?". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19); 16-24 February 2020" (PDF). who.int.

- ^ Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. (28 February 2020). "Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China". New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2002032. PMID 32109013.

- ^ a b c Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, et al. (February 2020). "Chest CT Findings in Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19): Relationship to Duration of Infection". Radiology: 200463. doi:10.1148/radiol.2020200463. PMID 32077789.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Gorbalenya, Alexander E. (11 February 2020). "Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus – The species and its viruses, a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group". bioRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.02.07.937862.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V (2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses". Nature Microbiology: 1–8. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PMID 32094589.

- ^ Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS (March 2020). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target". Intensive Care Medicine. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. PMID 32125455.

- ^ a b c Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, Peng J, Dan H, Zeng X, et al. (February 2020). "High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa". International Journal of Oral Science. 12 (1): 8. doi:10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x. PMC 7039956. PMID 32094336.

- ^ Gurwitz D (March 2020). "Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS‐CoV‐2 therapeutics". Drug Development Research. doi:10.1002/ddr.21656. PMID 32129518.

- ^ Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X (March 2020). "COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system". Nature Reviews Cardiology. doi:10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. PMID 32139904.

- ^ Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. (23 January 2020). "Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in humans and its potential bat origin". bioRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.01.22.914952.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Berger, Kevin (12 March 2020). "The Man Who Saw the Pandemic Coming". Nautilus. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) – China, 2020" (PDF). China CDC Weekly. 2. 20 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020 – via unpublished master.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Heymann DL, Shindo N (February 2020). "COVID-19: what is next for public health?". Lancet. 395 (10224): 542–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30374-3. PMID 32061313.

- ^ a b Walker, James (14 March 2020). "China Traces Cornovirus To First Confirmed Case, Nearly Identfying 'Patient Zero'". Newsweek. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ CDC (5 February 2020). "CDC Tests for 2019-nCoV". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Summary". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Real-Time RT-PCR Panel for Detection 2019-nCoV". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Curetis Group Company Ares Genetics and BGI Group Collaborate to Offer Next-Generation Sequencing and PCR-based Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Testing in Europe". GlobeNewswire News Room. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Brueck, Hilary (30 January 2020). "There's only one way to know if you have the coronavirus, and it involves machines full of spit and mucus". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases". Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Cohen J, Normile D (January 2020). "New SARS-like virus in China triggers alarm" (PDF). Science. 367 (6475): 234–35. doi:10.1126/science.367.6475.234. PMID 31949058. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 data hub". NCBI. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Pang J, Wang MX, Ang IY, Tan SH, Lewis RF, Chen JI, et al. (February 2020). "Potential Rapid Diagnostics, Vaccine and Therapeutics for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): A Systematic Review". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (3): 623. doi:10.3390/jcm9030623. PMID 32110875.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, Tian F, Jin DY, Chen L, et al. (February 2020). "Presumed Asymptomatic Carrier Transmission of COVID-19". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2565. PMC 7042844. PMID 32083643.

- ^ Wiles, Siouxsie (9 March 2020). "The three phases of Covid-19 – and how we can make it manageable". The Spinoff. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD (March 2020). "How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic?". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. PMID 32164834.

A key issue for epidemiologists is helping policy makers decide the main objectives of mitigation – eg, minimising morbidity and associated mortality, avoiding an epidemic peak that overwhelms health-care services, keeping the effects on the economy within manageable levels, and flattening the epidemic curve to wait for vaccine development and manufacture on scale and antiviral drug therapies.

- ^ Barclay, Eliza (10 March 2020). "How canceled events and self-quarantines save lives, in one chart". Vox.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Wiles, Siouxsie (14 March 2020). "After 'Flatten the Curve', we must now 'Stop the Spread'. Here's what that means". The Spinoff. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD (March 2020). "How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic?". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. PMID 32164834.

- ^ Grenfell, Rob; Drew, Trevor (17 February 2020). "Here's Why It's Taking So Long to Develop a Vaccine for the New Coronavirus". Science Alert. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Centers for Disease Control (3 February 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Prevention & Treatment". Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b World Health Organization. "Advice for Public". Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "When and how to use masks". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 8 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Prevention & Treatment". 10 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (11 February 2020). "What to do if you are sick with 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ M, Serena Josephine (14 February 2020). "Watch out! Spitting in public places too can spread infections". The Hindu. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sequence for Putting On Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Fisher D, Heymann D (February 2020). "Q&A: The novel coronavirus outbreak causing COVID-19". BMC Medicine. 18 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01533-w. PMC 7047369. PMID 32106852.

- ^ Kui L, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, et al. (February 2020). "Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province". Chinese Medical Journal: 1. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. PMID 32044814.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Cheng ZJ, Shan J (February 2020). "2019 Novel coronavirus: where we are and what we know". Infection. doi:10.1007/s15010-020-01401-y. PMID 32072569.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Vetter P, Eckerle I, Kaiser L (February 2020). "Covid-19: a puzzle with many missing pieces". BMJ. 368: m627. doi:10.1136/bmj.m627. PMID 32075791.

- ^ "Novel Coronavirus – COVID-19: What Emergency Clinicians Need to Know". www.ebmedicine.net. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Farkas, Josh (March 2020). COVID-19 - The Internet Book of Critical Care (digital) (Reference manual). USA: EMCrit. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "COVID19 - Resources for Health Care Professionals". Penn Libraries. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Cheung JC, Ho LT, Cheng JV, Cham EY, Lam KN (February 2020). "Staff safety during emergency airway management for COVID-19 in Hong Kong". Lancet Respiratory Medicine. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30084-9. PMID 32105633.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Nebehay, Stephanie; Kelland, Kate; Liu, Roxanne (5 February 2020). "WHO: 'no known effective' treatments for new coronavirus". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Ko WC, Rolain JM, Lee NY, Chen PL, Huang CT, Lee PI, Hsueh PR (March 2020). "Arguments in favor of remdesivir for treating SARS-CoV-2 infections". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents: 105933. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105933. PMID 32147516.

- ^ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X (February 2020). "Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies". Bioscience Trends. doi:10.5582/bst.2020.01047. PMID 32074550.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, et al. (February 2020). "Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro". Cell Research. 30 (3): 269–71. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. PMC 7054408. PMID 32020029.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Liu, Roxanne; Miller, Josh (3 March 2020). "China approves use of Roche drug in battle against coronavirus complications". Reuters. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "Effective Treatment of Severe COVID-19 Patients with Tocilizumab". ChinaXiv.org. 5 March 2020. doi:10.12074/202003.00026. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "3 patients get better on arthritis drug". 5 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus, via libera dell'Aifa al farmaco anti-artrite efficace su 3 pazienti e a un antivirale: test in 5 centri" (in Italian). Il Messaggero. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "How doctors can potentially significantly reduce the number of deaths from Covid-19". Vox. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China". Intensive Care Medicine. 3 March 2020. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "China turns Roche arthritis drug Actemra against COVID-19 in new treatment guidelines". FiercePharma. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "China launches coronavirus 'close contact' app". BBC News. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Chen, Angela. "China's coronavirus app could have unintended consequences". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. (March 2020). "Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 7 (3): 228–29. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. PMID 32032543.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. (March 2020). "The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 7 (3): e14. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. PMID 32035030.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "WHO Director-General's statement on the advice of the IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus". World Health Organization (WHO).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Wang W, Tang J, Wei F (April 2020). "Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (4): 441–47. doi:10.1002/jmv.25689. PMID 31994742.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Coronavirus Age, Sex, Demographics (COVID-19)". www.worldometers.info. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q (February 2020). "Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability". Lancet Global Health. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30068-1. PMID 32109372.

- ^ Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). World Health Organization (WHO), 16–24 February 2020

- ^ "BSI open letter to Government on SARS-CoV-2 outbreak response | British Society for Immunology". www.immunology.org. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Can you get coronavirus twice or does it cause immunity?". The Independent. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "They survived the coronavirus. Then they tested positive again. Why?". Los Angeles Times. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "14% of Recovered Covid-19 Patients in Guangdong Tested Positive Again - Caixin Global". www.caixinglobal.com. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51

- ^ https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Bollettino-sorveglianza-integrata-COVID-19_12-marzo-2020.pdf

- ^ https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a30402000000&bid=0030

- ^ Roser, Max; Ritchie, Hannah; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban (4 March 2020). "Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) – China, 2020. China CDC Weekly, 2020, 2(8): 113–22.

- ^ Cheung, Elizabeth (13 March 2020). "Some recovered Covid-19 patients may have lung damage, doctors say". South China Morning Post.

- ^ "Limited data on coronavirus may be skewing assumptions about severity". STAT. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Sparrow, Annie. "How China's Coronavirus Is Spreading – and How to Stop It". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "WHOが"致死率3%程度" 専門家「今後 注意が必要」". NHK. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Boseley, Sarah (17 February 2020). "Coronavirus causes mild disease in four in five patients, says WHO". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Diao, Ying; Liu, Xiaoyun; Wang, Tao; Zeng, Xiaofei; Dong, Chen; Zhou, Changlong; Zhang, Yuanming; She, Xuan; Liu, Dingfu; Hu, Zhongli (20 February 2020). "Estimating the cure rate and case fatality rate of the ongoing epidemic COVID-19". MedRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.02.18.20024513.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "2019-nCoV: preliminary estimates of the confirmed-case-fatality-ratio and infection-fatality-ratio, and initial pandemic risk assessment". institutefordiseasemodeling.github.io. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Report 4: Severity of 2019-novel coronavirus (nCoV)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, Luo F, Yu X, Zhang W, et al. (February 2020). "Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records". Lancet. 395 (10226): 809–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. PMID 32151335.

- ^ Cui, Pengfei; Chen, Zhe; Wang, Tian; Dai, Jun; Zhang, Jinjin; Ding, Ting; Jiang, Jingjing; Liu, Jia; Zhang, Cong; Shan, Wanying; Wang, Sheng; Rong, Yueguang; Chang, Jiang; Miao, Xiaoping; Ma, Xiangyi; Wang, Shixuan (27 February 2020). "Clinical features and sexual transmission potential of SARS-CoV-2 infected female patients: a descriptive study in Wuhan, China". MedRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.02.26.20028225.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R (March 2020). "Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19)". StatPearls [Internet]. PMID 32150360. Bookshelf ID: NBK554776.

- ^ Chen, Wen-Hsiang; Strych, Ulrich; Hotez, Peter J; Bottazzi, Maria Elena (3 March 2020). "The SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Pipeline: an Overview". Current Tropical Medicine Reports. doi:10.1007/s40475-020-00201-6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Li G, De Clercq E (March 2020). "Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 19 (3): 149–150. doi:10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. PMID 32127666.

- ^ a b Beeching, Nicholas J.; Fletcher, Tom E.; Fowler, Robert (2020). "BMJ Best Practices: COVID-19" (Document). BMJ.

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|access-date=,|archive-date=, and|archive-url=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|url-status=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "Physicians work out treatment guidelines for coronavirus". m.koreabiomed.com (in Korean). 13 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Plan (Provisional 7th Edition)". China Law Translate. 4 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Steenhuysen, Julie; Kelland, Kate (24 January 2020). "With Wuhan virus genetic code in hand, scientists begin work on a vaccine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Praveen Duddu. Coronavirus outbreak: Vaccines/drugs in the pipeline for Covid-19 Archived 19 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine. clinicaltrialsarena.com 19 February 2020.

- ^ Lu H. Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Biosci Trends. 28 January 2020. doi:10.5582/bst.2020.01020

- ^ a b Hoffmann, Markus; Kleine-Weber, Hannah; Krüger, Nadine; Müller, Marcel; Drosten, Christian; Pöhlmann, Stefan (31 January 2020). "The novel coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) uses the SARS-coronavirus receptor ACE2 and the cellular protease TMPRSS2 for entry into target cells". bioRxiv (preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.01.31.929042.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Okamura T, Shimizu Y, Hasegawa H, Takeda M, Nagata N (March 2019). "TMPRSS2 Contributes to Virus Spread and Immunopathology in the Airways of Murine Models after Coronavirus Infection". Journal of Virology. 93 (6). doi:10.1128/JVI.01815-18. PMC 6401451. PMID 30626688.

- ^ a b c d e Casadevall A, Pirofski LA (March 2020). "The convalescent sera option for containing COVID-19". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. doi:10.1172/JCI138003. PMID 32167489.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Pearce, Katie (13 March 2020). "Antibodies from COVID-19 survivors could be used to treat patients, protect those at risk: Infusions of antibody-laden blood have been used with reported success in prior outbreaks, including the SARS epidemic and the 1918 flu pandemic". The Hub at Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Novel coronavirus named 'Covid-19': WHO". TODAYonline. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "The coronavirus spreads racism against – and among – ethnic Chinese". The Economist. 17 February 2020. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Novel Coronavirus(2019-nCoV) Situation Report - 10" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). 30 January 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

External links

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak". World Health Organization (WHO).

- "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". European Medicines Agency (EMA).

- Steps to Prevent Illness (COVID-19) for the general population, by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Preventing COVID-19 Spread in Communities, by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Information for Healthcare Professionals, by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- "SARS-CoV-2 (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) Sequences". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- "Coronavirus: Latest news and resources". BMJ.

- "Novel Coronavirus Information Center". Elsevier.

- "COVID-19 Resource Centre". Lancet.

- "SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19". Nature.

- "Coronavirus (Covid-19)". NEJM.

- "Covid-19: Novel Coronavirus Content Free to Access". Wiley.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". JAMA Network.

- "Don't Panic: The comprehensive Ars Technica guide to the coronavirus". Ars Technica.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Filtering out Confusion: Frequently Asked Questions about Respiratory Protection, US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- Proper N95 Respirator Use for Respiratory Protection Preparedness, US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

![The severity of diagnosed COVID19 cases in China[115]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/47/Severity-of-coronavirus-cases-in-China-1.png/468px-Severity-of-coronavirus-cases-in-China-1.png)