15th century

| Millennium |

|---|

| 2nd millennium |

| Centuries |

| Timelines |

| State leaders |

| Decades |

| Categories: |

|

Births – Deaths Establishments – Disestablishments |

The 15th century was the century which spans the Julian years 1401 to 1500.

In Europe, the 15th century is seen as the bridge between the Late Middle Ages, the Early Renaissance, and the early modern period. Many technological, social and cultural developments of the 15th century can in retrospect be seen as heralding the "European miracle" of the following centuries. The architectural perspective and the field which is known today as accounting were founded in Italy.

Constantinople, known as the Capital of the World and the Capital of the Byzantine Empire (today's Turkey), falls to the emerging Muslim Ottoman Turks, marking the end of the tremendously influential Byzantine Empire and, for some historians, the end of the Middle Ages.[1] This led to the migration of Greek scholars and texts to Italy, while Johannes Gutenberg's invention of the mechanical movable type began the printing press. These two events played key roles in the development of the Renaissance.[2][3] The Roman Papacy was split in two parts in Europe for decades (the so-called Western Schism), until the Council of Constance. The division of the Catholic Church and the unrest associated with the Hussite movement would become factors in the rise of the Protestant Reformation in the following century. Islamic Spain (Al-Andalus) became dissolved through the Christian Reconquista, followed by the forced conversions and the Muslim rebellion,[4] ending over seven centuries of Islamic rule and returning Spain, Portugal and Southern France back to Christian rulers.

The search for the wealth and prosperity of India's Bengal Sultanate[5] led to the colonization of the Americas by Christopher Columbus in 1492 and the Portuguese voyages by Vasco da Gama, which linked Europe with the Indian subcontinent, ushering the period of Iberian empires.

The Hundred Years' War ended with a decisive French victory over the English in the Battle of Castillon. Financial troubles in England following the conflict results in the Wars of the Roses, a series of dynastic wars for the throne of England. The conflicts end with the defeat of Richard III by Henry VII at the Battle of Bosworth Field, establishing the Tudor dynasty in the later part of the century.

In Asia, the Timurid Empire collapsed, and the Afghan Pashtun Lodi dynasty is founded under the Delhi Sultanate. Under the rule of the Yongle Emperor, who built the Forbidden City and commanded Zheng He to explore the world overseas, the Ming Dynasty's territory reached its pinnacle.

In Africa, the spread of Islam leads to the destruction of the Christian kingdoms of Nubia, by the end of the century leaving only Alodia (which was to collapse in 1504). The formerly vast Mali Empire teeters on the brink of collapse, under pressure from the rising Songhai Empire.

In the Americas, both the Inca Empire and the Aztec Empire reach the peak of their influence, but the European colonization of the Americas changed the course of modern history.

Events

- 1401: Dilawar Khan establishes the Malwa Sultanate in present-day central India.

- 1402: Ottoman and Timurid Empires fight at the Battle of Ankara resulting in Timur's capture of Bayezid I.

- 1402: Sultanate of Malacca founded by Parameswara.[6]

- 1402: The settlement of the Canary Islands signals the beginning of the Spanish Empire.

- 1403–1413: Ottoman Interregnum, a civil war between the four son's of Bayezid I.

- 1403: The Yongle Emperor moves the capital of China from Nanjing to Beijing.[7]

- 1404–1406: Paregreg war, Majapahit civil war of secession between Wikramawardhana against Wirabhumi.

- 1405–1433: During the Ming treasure voyages, Admiral Zheng He of China sails through the Indian Ocean to Malacca, India, Ceylon, Persia, Arabia, and East Africa to spread China's influence and sovereignty.

- 1405–1407: The first voyage of Zheng He, a massive Ming dynasty naval expedition visited Java, Palembang, Malacca, Aru, Samudera and Lambri.[8] (to 1433)

- 1410: The Battle of Grunwald is the decisive battle of the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War leading to the downfall of the Teutonic Knights.

- 1410–1413: Foundation of St Andrews University in Scotland.

- 1414: Khizr Khan, deputised by Timur to be the governor of Multan, takes over Delhi founding the Sayyid dynasty.

- 1415: Henry the Navigator leads the conquest of Ceuta from the Moors marking the beginning of the Portuguese Empire.

- 1415: Battle of Agincourt fought between the Kingdom of England and France.

- 1415: Jan Hus is burned at the stake as a heretic at the Council of Constance.

- 1419–1433: The Hussite Wars in Bohemia.

- 1420: Construction of the Chinese Forbidden City is completed in Beijing.

- 1424: James I returns to Scotland after being held hostage under three Kings of England since 1406.

- 1424: Deva Raya II succeeds his father Veera Vijaya Bukka Raya as monarch of the Vijayanagara Empire.

- 1425: Catholic University of Leuven (Belgium) founded by Pope Martin V.

- 1429: Joan of Arc ends the Siege of Orléans and turns the tide of the Hundred Years' War.

- 1429: Queen Suhita succeeds her father Wikramawardhana as ruler of Majapahit.[9]

- 1431

- January 9 – Pretrial investigations for Joan of Arc begin in Rouen, France under English occupation.

- March 3 – Pope Eugene IV succeeds Pope Martin V, to become the 207th pope.

- March 26 – The trial of Joan of Arc begins.

- May 30 – Nineteen-year-old Joan of Arc is burned at the stake.

- June 16 – the Teutonic Knights and Švitrigaila sign the Treaty of Christmemel, creating anti-Polish alliance

- September – Battle of Inverlochy: Donald Balloch defeats the Royalists.

- October 30 – Treaty of Medina del Campo, consolidating peace between Portugal and Castille.

- December 16 – Henry VI of England is crowned King of France.

- 1438: Pachacuti founds the Inca Empire.

- 1440: Eton College founded by Henry VI.

- 1440s: The Golden Horde breaks up into the Siberia Khanate, the Khanate of Kazan, the Astrakhan Khanate, the Crimean Khanate, and the Great Horde.

- 1440–1469: Under Moctezuma I, the Aztecs become the dominant power in Mesoamerica.

- 1440: Oba Ewuare comes to power in the West African city of Benin, and turns it into an empire.

- 1441: Jan van Eyck, Flemish painter, dies.

- 1441: Portuguese navigators cruise West Africa and reestablish the European slave trade with a shipment of African slaves sent directly from Africa to Portugal.

- 1441: A civil war between the Tutul Xiues and Cocom breaks out in the League of Mayapan. As a consequence, the league begins to disintegrate.

- 1442: Leonardo Bruni defines Middle Ages and Modern times.

- 1443: Abdur Razzaq visits India.

- 1443: King Sejong the Great publishes the hangul, the native phonetic alphabet system for the Korean language.

- 1444: The Albanian league is established in Lezha, Skanderbeg is elected leader. A war begins against the Ottoman Empire. An Albanian state is set up and lasts until 1479.

- 1444: Ottoman Empire under Sultan Murad II defeats the Polish and Hungarian armies under Władysław III of Poland and János Hunyadi at the Battle of Varna.

- 1445: The Kazan Khanate defeats the Grand Duchy of Moscow at the Battle of Suzdal.

- 1446: Mallikarjuna Raya succeeds his father Deva Raya II as monarch of the Vijayanagara Empire.

- 1447: Wijaya Parakrama Wardhana, succeeds Suhita as ruler of Majapahit.[9]

- 1449: Saint Srimanta Sankardeva was born.

- 1449: Esen Tayisi leads an Oirat Mongol invasion of China which culminate in the capture of the Zhengtong Emperor at Battle of Tumu Fortress.

- 1450s: Machu Picchu constructed.

- 1451: Bahlul Khan Lodhi ascends the throne of the Delhi sultanate starting the Lodhi dynasty

- 1451: Rajasawardhana, born Bhre Pamotan, styled Brawijaya II succeeds Wijayaparakramawardhana as ruler of Majapahit.[9]

- 1453: The Fall of Constantinople marks the end of the Byzantine Empire and the death of the last Roman Emperor Constantine XI and the beginning of the Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire.

- 1453: The Battle of Castillon is the last engagement of the Hundred Years' War and the first battle in European history where cannons were a major factor in deciding the battle.

- 1453: Reign of Rajasawardhana ends.[9]

- 1454–1466: After defeating the Teutonic Knights in the Thirteen Years' War, Poland annexes Royal Prussia.

- 1455–1485: Wars of the Roses – English civil war between the House of York and the House of Lancaster.

- 1456: Joan of Arc is posthumously acquitted of heresy by the Catholic Church, redeeming her status as the heroine of France.

- 1456: The Siege of Belgrade halts the Ottomans' advance into Europe.

- 1456: Girishawardhana, styled Brawijaya III, becomes ruler of Majapahit.[9]

- 1457: Construction of Edo Castle begins.

- 1461: The League of Mayapan disintegrates. The league is replaced by seventeen Kuchkabal.

- 1461: The city of Sarajevo is founded by the Ottomans.

- 1461

- February 2 – Battle of Mortimer's Cross: Yorkist troops led by Edward, Duke of York defeat Lancastrians under Owen Tudor and his son Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke in Wales.

- February 17 – Second Battle of St Albans, England: The Earl of Warwick's army is defeated by a Lancastrian force under Queen Margaret, who recovers control of her husband.

- March 4 – The Duke of York seizes London and proclaims himself King Edward IV of England.

- March 5 – Henry VI of England is deposed by the Duke of York during war of the Roses.

- March 29 – Battle of Towton: Edward IV defeats Queen Margaret to make good his claim to the English throne (thought to be the bloodiest battle ever fought in England).

- June 28 – Edward, Richard of York's son, is crowned as Edward IV, King of England (reigns until 1483).

- July – Byzantine general Graitzas Palaiologos honourably surrenders Salmeniko Castle, last garrison of the Despotate of the Morea, to invading forces of the Ottoman Empire after a year-long siege.

- July 22 – Louis XI of France succeeds Charles VII of France as king (reigns until 1483).

- 1462: Sonni Ali Ber, the ruler of the Songhai (or Songhay) Empire, along the Niger River, conquers Mali in the central Sudan by defeating the Tuareg contingent at Tombouctou (or Timbuktu) and capturing the city. He develops both his own capital, Gao, and the main centres of Mali, Timbuktu and Djenné, into major cities. Ali Ber controls trade along the Niger River with a navy of war vessels.

- 1462: Mehmed the Conqueror is driven back by Wallachian prince Vlad III Dracula at The Night Attack.

- 1464: Edward IV of England secretly marries Elizabeth Woodville.

- 1465: The 1465 Moroccan revolt ends in the murder of the last Marinid Sultan of Morocco Abd al-Haqq II.

- 1466: Singhawikramawardhana, succeeds Girishawardhana as ruler of Majapahit.[9]

- 1467: Uzun Hasan defeats the Black Sheep Turkoman leader Jahān Shāh.

- 1467–1615: The Sengoku period is one of civil war in Japan.

- 1469: The marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile leads to the unification of Spain.

- 1469: Matthias Corvinus of Hungary conquers some parts of Bohemia.

- 1469: Birth of Guru Nanak Dev. Beside followers of Sikhism, Guru Nanak is revered by Hindus and Muslim Sufis across the Indian subcontinent.

- 1470: The Moldavian forces under Stephen the Great defeat the Tatars of the Golden Horde at the Battle of Lipnic.

- 1471: The kingdom of Champa suffers a massive defeat by the Vietnamese king Lê Thánh Tông.

- 1472: Abu Abd Allah al-Sheikh Muhammad ibn Yahya becomes the first Wattasid Sultan of Morocco.

- 1474–1477: Burgundy Wars of France, Switzerland, Lorraine and Sigismund II of Habsburg against the Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

- 1478: Muscovy conquers Novgorod.

- 1478: Reign of Singhawikramawardhana ends.[9]

- 1478: The Great Mosque of Demak is the oldest mosque in Java, built by the Wali Songo during the reign of Sultan Patah.

- 1479: Battle of Breadfield, Matthias Corvinus of Hungary defeated the Turks.

- 1480: After the Great standing on the Ugra river, Muscovy gained independence from the Great Horde.

- 1481: Spanish Inquisition begins in practice with the first auto-da-fé.

- 1485: Matthias Corvinus of Hungary captured Vienna, Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor ran away.

- 1485: Henry VII defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth and becomes King of England.

- 1485: Ivan III of Russia conquered Tver.

- 1485: Saluva Narasimha Deva Raya drives out Praudha Raya ending the Sangama Dynasty.

- 1486: Sher Shah Suri, is born in Sasaram, Bihar.

- 1488: Portuguese Navigator Bartolomeu Dias sails around the Cape of Good Hope.

- 1492: The death of Sunni Ali Ber left a leadership void in the Songhai Empire, and his son was soon dethroned by Mamadou Toure who ascended the throne in 1493 under the name Askia (meaning "general") Muhammad. Askia Muhammad made Songhai the largest empire in the history of West Africa. The empire went into decline, however, after 1528, when the now-blind Askia Muhammad was dethroned by his son, Askia Musa.

- 1492: Boabdil's surrender of Granada marks the end of the Spanish Reconquista and Al-Andalus.

- 1492: Ferdinand and Isabella sign the Alhambra Decree, expelling all Jews from Spain unless they convert to Catholicism; 40,000–200,000 leave.

- 1492: Christopher Columbus landed in the Americas from Spain.

- 1494: Spain and Portugal sign the Treaty of Tordesillas and agree to divide the World outside of Europe between themselves.

- 1494–1559: The Italian Wars lead to the downfall of the Italian city-states.

- 1497–1499: Vasco da Gama's first voyage from Europe to India and back.

- 1499: Ottoman fleet defeats Venetians at the Battle of Zonchio.

- 1499: Michelangelo's Pietà in St. Peter's Basilica is made in Rome

- 1500: Islam becomes the dominant religion across the Indonesian archipelago.[10]

- 1500: Around late 15th century Bujangga Manik manuscript was composed, tell the story of Jaya Pakuan Bujangga Manik, a Sundanese Hindu hermit journeys throughout Java and Bali.[11]

Significant people

- Abu Sa'id al-Afif, Samaritan physician.

- Pachacuti (c. 1418–1471/72) was the ninth Sapa Inca, likely builder of Machu Picchu and founder of the Inca Empire.

- Afonso de Albuquerque (1453–1515), was a Portuguese nobleman, naval general officer whose military and administrative activities conquered and established the Portuguese colonial empire in the Indian Ocean. Generally considered as a world conquest military genius by means of his successful strategy.

- Ah Xiu Xupan, last ruler of the Mayan city–state of Uxmal.

- Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, Renaissance ruler (1443–1490).

- George Kastrioti, Skanderbeg – Albanian Prince who resisted the Ottomans for almost 30 years (1405–1468).

- Ferdinand II of Aragon, co-ruler of Spain with Isabella I of Castile and responsible with her for the unification of Spain (1452–1516).

- Johannes Gutenberg, European inventor of printing with movable type (c. 1398–1468)

- Constantine XI, the last Byzantine Emperor and Roman Emperor. (1405–1453)

- Henry the Navigator Infante Henrique, Duke of Viseu (1394–1460); infante (prince) of the Portuguese House of Aviz and an important figure in the early days of the Portuguese Empire, being responsible for the beginning of the European worldwide explorations.

- Henry V of England, the English King who won the famous Battle of Agincourt in 1415 (1387–1422).

- Henry VI of England, English King (1421–1471)

- Henry VII of England, English King and founder of the Tudor dynasty (1457–1509).

- The Princes in the Tower, Edward V of England (1470–1483?) and his brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, 1st Duke of York (1473–1483?), two sons of Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville.

- John Hunyadi, Regent of Kingdom of Hungary, won the Siege of Belgrade in 1456 (c. 1406–1456)

- Jan Hus, Bohemian religious thinker and reformer (c. 1372–1415).

- Isabella I of Castile, co-ruler of Spain with Ferdinand II of Aragon and responsible for the unification of Spain and the discovery of the New World (1451–1504).

- Ivan III of Russia, Grand Duke of Moscow who ended the dominance of the Golden Horde over the Rus (1440–1505)

- Joan of Arc, military commander and national heroine of France (1412–1431).

- Kazimierz IV Jagiellon King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1427–1492).

- Louis XI, King of France (1423–1483).

- Mehmed II, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and Conqueror of Constantinople (1432–1481).

- Babur, the founder of the Mughal empire (1483–1530).

- Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Vaishnav saint and important social reformer (1486–1534).

- Guru Nanak, founder of the Sikh Religion (1469–1539).

- Srimanta Sankardeva, founder of Ekasarana Religion preacher of Vaishnavism, creator of Sattriya Dance, Ankiya Nat, Satras etc.

- Sejong the Great of Joseon, a Korean monarch who developed hangul, the native Korean alphabet (1397–1450).

- Stephen III of Moldavia, also known as Stephen the Great, ruler of Moldavia, national hero of Romanians for long resistance to the Ottomans (1437–1504)

- Richard III of England, last English King of the House of York, last of the House of Plantagenet (1452–1485).

- Mir Chakar Khan Rind (1468–1565), a Baloch chieftain.

- Vlad III Dracula, Prince of Wallachia who led the defense of his territory against the expanding Ottoman Empire (1431–1476).

- Oba Ewuare, transformed the city state of Benin into the Benin Empire.

Visual artists, architects, sculptors, printmakers, illustrators

- Bartolomé Bermejo (c. 1440 – 1498), Spanish painter who adopted Dutch painting techniques and conventions.

- Pedro Berruguete (c. 1450 – 1504), Spanish painter.

- Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450 – 1516), Early Netherlandish painter. Many of his works depict sin and human moral failings.

- Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445 – 1510), Italian painter.

- Dirk Bouts (c. 1410/1420 – 1475), Early Netherlandish painter.

- Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446), invents one-point perspective, leads innovation in Italian architecture.

- Robert Campin (c. 1375 – 1444), the Master of Flémalle, first great master of Early Netherlandish painting.

- Petrus Christus (c. 1410/1420 – 1475/1476), Early Netherlandish painter.

- Gerard David (c. 1460 – 1523), Early Netherlandish painter and manuscript illuminator known for his brilliant use of color.

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)[12] was a German painter, printmaker and theorist from Nuremberg, Germany.

- Barthélemy d'Eyck;[13] (c. 1420 – after 1470)[14] was an Early Netherlandish artist who worked in France and probably in Burgundy Early Netherlandish painter and manuscript illuminator. He was active between about 1440 to about 1469.[15]

- Dionisius (c. 1440 – 1502), Russian painter

- Hubert van Eyck (c. 1366 – 1426), Flemish painter and older brother of Jan van Eyck.

- Jan van Eyck (before c. 1395 – before 1441), Early Netherlandish painter, considered one of the best Northern European painters of the 15th century.

- Juan de Flandes (1460–1519), Early Netherlandish painter who was active in Spain from 1496 to 1519 at the court of Isabella I of Castile.

- Jean Fouquet (1420–1481) French painter of both panel painting and manuscript illumination, inventor of the portrait miniature.

- Piero della Francesca (c. 1415–1492) Italian painter

- Nicolas Froment (c. 1435 – c. 1486), French painter.

- Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455) was an Italian artist of the early Renaissance best known for works in sculpture and metalworking.

- Hugo van der Goes (c. 1440 – 1482 or 1483), Early Netherlandish painter.

- Jean Hey (c. 1475 – c. 1505),[16] now generally identified with the artist formerly known as the Master of Moulins, Early Netherlandish painter.

- Hans Holbein the Elder (c. 1460 – 1524), German painter, woodcut artist, illustrator of books and church window designer.[17] He and his brother Sigismund Holbein painted religious works in the late Gothic style.

- Limbourg brothers, (Herman, Paul, and Johan; 1385–1416), Dutch Renaissance miniature painters from the city of Nijmegen.

- Simon Marmion (c. 1425 – 1489) French, or Burgundian, painter of panels and illuminated manuscripts.

- Masaccio, (c. 1401 – 1428), Italian painter.

- Hans Memling (c. 1430 – 1494), Early Netherlandish painter, born in Germany.

- Michelozzo (1396–1472), Italian architect and sculptor.

- Andrei Rublev (c. 1360 – c. 1430), Russian painter.

- Enguerrand Quarton (c. 1410 – c. 1466) was a French painter and manuscript illuminator.

- Leonardo da Vinci, (1452–1519), Italian polymath, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, painter, sculptor, architect, botanist, musician and writer.

- Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400 – 1464), considered one of the greatest exponents of Early Netherlandish painting.

See links above for Italian Renaissance painting and Renaissance sculpture.

Literature

- Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) was an Italian author, artist, architect, poet, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer, and general Renaissance humanist polymath.

- Joseph Albo (c. 1380 – 1444) was a Jewish philosopher and rabbi who lived in Spain.

- John Argyropoulos (1415–1487), Greek lecturer, philosopher and humanist.

- Antonio Beccadelli (1394–1471), Italian poet, canon lawyer, scholar, diplomat, and chronicler.

- Vespasiano da Bisticci (1421–1498), Italian humanist and librarian.

- Matteo Maria Boiardo (1440/1 – 1494), Italian poet.

- Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459), Italian writer and humanist.

- Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370 – 1444), Italian humanist, historian and statesman.

- Laonikos Chalkokondyles (1423–1490), Greek scholar.

- Pal Engjëlli (1416–1470) was an Albanian Catholic clergyman, Archbishop of Durrës and Cardinal of Albania.

- Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), Italian humanist and writer.

- Constantine Lascaris (1434–1501), Greek scholar and grammarian.

- Antonio de Lebrija (1441–1522), Spanish scholar, historian, teacher, astronomer and poet.

- John Lydgate (c.1370 – c.1451), English monk and poet.

- Sir Thomas Malory (1405–1471), English writer.

- Jorge Manrique (c.1440 – 1479), Spanish poet.

- Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), Italian Renaissance philosopher.

- Iñigo López de Mendoza (1398–1458) Castilian (Spanish) politician and poet.

- Afanasy Nikitin (? – 1472), Russian merchant, traveler and writer.

- Thomas Occleve (c. 1368 – 1426), English poet.

- Reginald Pecock (c. 1395 – 1460), was an English prelate and writer.

- Christine de Pizan, French writer (1364–1430).

- Poliziano (1454–1494), Italian classical scholar and poet.

- Giovanni Pontano (1426–1503), Italian humanist and poet.

- Luigi Pulci (1432–1484), Italian poet.

- Bartolomeo Sacchi (1421–1481), Italian humanist writer and gastronomist.

- Lorenzo Valla (c.1407 – 1457), Italian humanist, rhetorician, and educator.

- Gil Vicente (c. 1465 – c. 1536), Portuguese poet.

- François Villon (c.1431 – 1474), French poet .

Musicians and composers

- Juan de Anchieta (1462 – 1523, Spanish composer of the Renaissance.

- Adrien Basin (c. 1457 – 1476; died after 1498), Franco-Flemish composer, singer, and diplomat of the Burgundian school of the early Renaissance.

- Gilles Binchois, (c. 1400 – 1460), Franco-Flemish composer, one of the earliest members of the Burgundian School.

- Antoine Busnois (c. 1430 – 1492), French composer and poet of the early Renaissance Burgundian School.

- Guillaume Dufay, (c. 1397 – 1474), Franco-Flemish composer and music theorist.

- John Dunstaple (c. 1390 – 1453), English composer of polyphonic music.

- Juan del Encina (1468–1530), Spanish composer, poet and playwright.

- Hayne van Ghizeghem (c. 1445 – 1472 or possibly later; New Grove says he died between 1472 and 1497), Flemish composer of the early Renaissance Burgundian School.

- Nicolas Grenon (c. 1375 – 1456), French composer of the early Renaissance.

- Robert Morton (c. 1430 – 1479), English composer of the early Renaissance.

- Johannes Ockeghem, (c. 1410 – 1497), Flemish composer.

- Francisco de Peñalosa (c. 1470 – 1528), Spanish composer of the middle Renaissance..

- Leonel Power (c. 1370 to 1385 – 1445), English composer of the late Medieval and early Renaissance eras.

- Johannes Tapissier (c. 1370 – 1408 to 1410), French composer and teacher of the late Middle Ages.

- Jacobus Vide (c. 1405 – 1433), Franco-Flemish composer of the transitional period between the medieval period and early Renaissance.

- Josquin des Prez (c. 1450 – 1521), Franco-Flemish composer of the Renaissance.

Exploration

- Johann Schiltberger (1381 – c. 1440), German traveller throughout the Middle East and Central Asia.

- Diogo de Azambuja (1432–1518) Portuguese explorer of the African coast.

- John Cabot (c. 1450 – 1499) – Italian explorer for England. Claimed Newfoundland for the Kingdom of England.

- Pedro Álvares Cabral (c. 1467 – c. 1520), Portuguese navigator and explorer.

- Pêro Vaz de Caminha (c. 1450 – 1500), Portuguese explorer that accompanied Pedro Álvares Cabral in the discovery of Brazil.

- Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) – Italian explorer for Spain. Sailed in 1492 and arrived in (hailed with the discovery of) the "New World" of the Americas.

- Niccolò Da Conti (1395–1469), Venetian merchant and explorer, born in Chioggia, who traveled to India and Southeast Asia.

- Bartolomeu Dias (c. 1450 – 1500) – Portuguese explorer. He sailed from Portugal and reached the Cape of Good Hope.

- Vasco da Gama reaches India for Portugal, creating the first maritime alternative for the Silk Road (c. 1469 – 1524)

- Zheng He, Chinese eunuch admiral and explorer (1371–1433).

- João Fernandes Lavrador (1445?–1501) – Portuguese explorer. One of the first European's to reach Newfoundland and Labrador.

- João da Nova (c. 1460 – 1509), Portuguese explorer of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean.

- Amerigo Vespucci (c. 1454 – 1512) – Italian explorer for Spain. Sailed in 1499 and 1502. He explored the east coast of South America.

Science, invention and philosophy

- Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1400 – 1468) was a German goldsmith and printer who is credited with inventing movable type printing in Europe around 1439, and mechanical printing globally.

- Pietro Pomponazzi (1462–1525), Italian philosopher.

- Georg von Peuerbach (1423–1461), German/Austrian astronomer and mathematician.

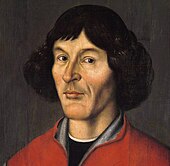

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), Father of modern astronomy

- Regiomontanus (1436–1476), Mathematician and astronomer

Inventions, discoveries, introductions

List of 15th century inventions

- Renaissance affects philosophy, science and art.

- Rise of Modern English language from Middle English.

- Introduction of the noon bell in the Catholic world.

- Public banks

- Yongle Encyclopedia—over 22,000 volumes

- Hangul alphabet in Korea

- Scotch whisky

- Psychiatric hospitals[clarification needed]

- Development of the woodcut for printing between 1400–1450

- Movable type first used by King Taejong of Joseon—1403 (Movable type, which allowed individual characters to be arranged to form words, was invented in China by Bi Sheng between 1041 and 1048.)

- Although pioneered earlier in Korea and by the Chinese official Wang Zhen (with tin), bronze metal movable type printing is created in China by Hua Sui in 1490.

- Johannes Gutenberg advances the printing press in Europe (c. 1455)

- Linear perspective drawing perfected by Filippo Brunelleschi 1410–1415

- Invention of the harpsichord c. 1450

- Arrival of Christopher Columbus to the Americas in 1492

References

- ^ Crowley, Roger (2006). Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453. Faber. ISBN 0-571-22185-8. (reviewed by Foster, Charles (22 September 2006). "The Conquestof Constantinople and the end of empire". Contemporary Review. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009.

It is the end of the Middle Ages

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Renaissance, 2008, O.Ed.

- ^ McLuhan 1962; Eisenstein 1980; Febvre & Martin 1997; Man 2002

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Nanda, J. N (2005). Bengal: the unique state. Concept Publishing Company. p. 10. 2005. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2.

Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- ^ Winstedt, R. O. (1948). "The Malay Founder of Medieval Malacca". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 12 (3/4). Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies: 726–729. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00083312. JSTOR 608731.

- ^ "An introduction to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644)". Khan Academy. Asian Art Museum. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Modern interpretation of the place names recorded by Chinese chronicles can be found e.g. in Some Southeast Asian Polities Mentioned in the MSL Archived 12 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine by Geoffrey Wade

- ^ a b c d e f g Ricklefs (1991), page 18.

- ^ Leinbach, Thomas R. (20 February 2019). "Religions". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Noorduyn, J. (2006). Three Old Sundanese poems. KITLV Press. p. 437.

- ^ Mueller, Peter O. (1993) Substantiv-Derivation in Den Schriften Albrecht Durers, Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012815-2.

- ^ Also sometimes in contemporary documents Barthélemy de Cler, der Clers, Deick d'Ecle, d'Eilz – Harthan, John, The Book of Hours, p. 93, 1977, Thomas Y Crowell Company, New York, ISBN 0-690-01654-9

- ^ Unterkircher, Franz (1980). King René's Book of Love (Le Cueur d'Amours Espris). New York: G. Braziller. ISBN 0-8076-0989-7.

- ^ Tolley 2001, p. [page needed].

- ^ Brigstocke, 2001, p. 338

- ^ "Hans Holbein". Catholic Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

Sources

- Febvre, Lucien; Martin, Henri-Jean (1997), The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450–1800, London: Verso, ISBN 1-85984-108-2

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. (1980), The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29955-1

- Tolley, Thomas (2001). "Eyck, Barthélemy d'". In Hugh Brigstocke (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866203-3.

- Harvey, L. P. (16 May 2005). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31963-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Man, John (2002), The Gutenberg Revolution: The Story of a Genius and an Invention that Changed the World, London: Headline Review, ISBN 978-0-7472-4504-9

- McLuhan, Marshall (1962), The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1st ed.), University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-6041-9