Spice

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are sometimes used in medicine, religious rituals, cosmetics or perfume production. For example, vanilla is commonly used as an ingredient in fragrance manufacturing.[1]

A spice may be available in several forms: fresh, whole dried, or pre-ground dried. Generally, spices are dried. Spices may be ground into a powder for convenience. A whole dried spice has the longest shelf life, so it can be purchased and stored in larger amounts, making it cheaper on a per-serving basis. A fresh spice, such as ginger, is usually more flavorful than its dried form, but fresh spices are more expensive and have a much shorter shelf life. Some spices are not always available either fresh or whole, for example turmeric, and often must be purchased in ground form. Small seeds, such as fennel and mustard seeds, are often used both whole and in powder form.

Although health benefits are often claimed for spices, there is currently not enough research conducted to prove these benefits.[2]

India contributes to 75% of global spice production. This is reflected culturally through their cuisine; historically, the spice trade developed throughout the Indian subcontinent, as well as in East Asia and the Middle East. Europe's demand for spices was among the economic and cultural factors that encouraged exploration in the early modern period.

Etymology

The word spice originated in Middle English[3] which came from the Old French words espece, espis(c)e, and espis(c)e.[4] According to the Middle English Dictionary, the Old French words came from Anglo-French spece;[4] according to Merriam Webster, the Old-French words came from Anglo-French espece, and espis.[3] Both publications agree that the Anglo-French words derived from Latin species.[3][4] Middle English spice had its first known use as a noun in the 13th century.[3]

History

Early history

The spice trade developed throughout the Indian subcontinent[5] by at earliest 2000 BCE with cinnamon and black pepper, and in East Asia with herbs and pepper. The Egyptians used herbs for mummification and their demand for exotic spices and herbs helped stimulate world trade. By 1000 BCE, medical systems based upon herbs could be found in China, Korea, and India. Early uses were connected with magic, medicine, religion, tradition, and preservation.[6]

Cloves were used in Mesopotamia by 1700 BCE.[note 1] The ancient Indian epic Ramayana mentions cloves. The Romans had cloves in the 1st century CE, as Pliny the Elder wrote about them.[10] The earliest written records of spices come from ancient Egyptian, Chinese, and Indian cultures. The Ebers Papyrus from early Egypt dating from 1550 BCE describes some eight hundred different medicinal remedies and numerous medicinal procedures.[11] Historians believe that nutmeg, which originates from the Banda Islands in Southeast Asia, was introduced to Europe in the 6th century BCE.[12]

Indonesian merchants traveled around China, India, the Middle East, and the east coast of Africa. Arab merchants facilitated the routes through the Middle East and India. This resulted in the Egyptian port city of Alexandria being the main trading center for spices. The most important discovery prior to the European spice trade was the monsoon winds (40 CE). Sailing from Eastern spice cultivators to Western European consumers gradually replaced the land-locked spice routes once facilitated by the Middle East Arab caravans.[6]

Spices were prominent enough in the ancient world that they are mentioned in the Old Testament. In Genesis, Joseph was sold into slavery by his brothers to spice merchants. In Exodus, manna is described as being similar to coriander in appearance. In the Song of Solomon, the male narrator compares his beloved to many saffron, cinnamon, and other spices.

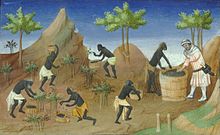

Middle Ages

Spices were among the most demanded and expensive products available in Europe in the Middle Ages,[5] the most common being black pepper, cinnamon (and the cheaper alternative cassia), cumin, nutmeg, ginger and cloves. Given medieval medicine's main theory of humorism, spices and herbs were indispensable to balance "humors" in food,[6] a daily basis for good health at a time of recurrent pandemics. In addition to being desired by those using medieval medicine, the European elite also craved spices in the Middle Ages. An example of the European aristocracy's demand for spice comes from the King of Aragon, who invested substantial resources into bringing back spices to Spain in the 12th century. He was specifically looking for spices to put in wine, and was not alone among European monarchs at the time to have such a desire for spice.[13]

Spices were all imported from plantations in Asia and Africa, which made them expensive. From the 8th until the 15th century, the Republic of Venice held a monopoly on spice trade with the Middle East, using this position to dominate the neighboring Italian maritime republics and city-states. The trade made the region rich. It has been estimated that around 1,000 tons of pepper and 1,000 tons of the other common spices were imported into Western Europe each year during the Late Middle Ages. The value of these goods was the equivalent of a yearly supply of grain for 1.5 million people.[14] The most exclusive was saffron, used as much for its vivid yellow-red color as for its flavor. Spices that have now fallen into obscurity in European cuisine include grains of paradise, a relative of cardamom which mostly replaced pepper in late medieval north French cooking, long pepper, mace, spikenard, galangal and cubeb.[15]

Early modern period

Spain and Portugal were interested in seeking new routes to trade in spices and other valuable products from Asia. The control of trade routes and the spice-producing regions were the main reasons that Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama sailed to India in 1499.[8] When da Gama discovered the pepper market in India, he was able to secure peppers for a much cheaper price than the ones demanded by Venice.[13] At around the same time, Christopher Columbus returned from the New World. He described to investors new spices available there.[citation needed]

Another source of competition in the spice trade during the 15th and 16th century was the Ragusans from the maritime republic of Dubrovnik in southern Croatia.[16] The military prowess of Afonso de Albuquerque (1453–1515) allowed the Portuguese to take control of the sea routes to India. In 1506, he took the island of Socotra in the mouth of the Red Sea and, in 1507, Ormuz in the Persian Gulf. Since becoming the viceroy of the Indies, he took Goa in India in 1510, and Malacca on the Malay peninsula in 1511. The Portuguese could now trade directly with Siam, China, and the Maluku Islands.

With the discovery of the New World came new spices, including allspice, chili peppers, vanilla, and chocolate. This development kept the spice trade, with America as a latecomer with its new seasonings, profitable well into the 19th century.[citation needed]

Function

Spices are primarily used as food flavoring or to create variety.[17] They are also used to perfume cosmetics and incense. At various periods, many spices have been believed to have medicinal value. Finally, since they are expensive, rare, and exotic commodities, their conspicuous consumption has often been a symbol of wealth and social class.[15]

Preservative claim

The most popular explanation for the love of spices in the Middle Ages is that they were used to preserve meat from spoiling, or to cover up the taste of meat that had already gone off. This compelling but false idea constitutes something of an urban legend, a story so instinctively attractive that mere fact seems unable to wipe it out... Anyone who could afford spices could easily find meat fresher than what city dwellers today buy in their local supermarket.[15]

It is often claimed that spices were used either as food preservatives or to mask the taste of spoiled meat, especially in the European Middle Ages.[15][18] This is false.[19][20][21][15] In fact, spices are rather ineffective as preservatives as compared to salting, smoking, pickling, or drying, and are ineffective in covering the taste of spoiled meat.[15] Moreover, spices have always been comparatively expensive: in 15th century Oxford, a whole pig cost about the same as a pound of the cheapest spice, pepper.[15] There is also no evidence of such use from contemporary cookbooks: "Old cookbooks make it clear that spices weren't used as a preservative. They typically suggest adding spices toward the end of the cooking process, where they could have no preservative effect whatsoever."[22] Indeed, Cristoforo di Messisbugo suggested in the 16th century that pepper may speed up spoilage.[22]

Though some spices have antimicrobial properties in vitro,[23] pepper—by far the most common spice—is relatively ineffective, and in any case, salt, which is far cheaper, is also far more effective.[22]

Classification and types

Culinary herbs and spices

Botanical basis

- Seeds, such as fennel, mustard, nutmeg, and black pepper

- Fruits, such as Cayenne pepper and Chimayo pepper

- Arils, such as mace (part of nutmeg plant fruit)

- Barks, such as True Cinnamon and cassia

- Flower buds, such as cloves

- Stigmas, such as saffron

- Roots and rhizomes, such as turmeric, ginger and galangal

- Resins, such as asafoetida

Common spice mixtures

- Advieh (Iran)

- Baharat (Arab world, and the Middle East in general)

- Berbere (Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia)

- Bumbu (Indonesia)

- Cajun (United States)

- Chaat masala (Indian subcontinent)

- Chili powder and crushed red pepper (Cayenne, Chipotle, Jalapeño, New Mexico, Tabasco, and other cultivars)

- Curry powder

- Five-spice powder (China)

- Garam masala (Indian subcontinent)

- Harissa (North Africa)

- Hawaij (Yemen)

- Jerk spice (Jamaica)

- Khmeli suneli (Georgia, former U.S.S.R.)

- Masala (a generic name for any mix used in the Indian subcontinent)

- Mixed spice (United Kingdom)

- Panch phoron (Indian subcontinent)

- Pumpkin pie spice (United States)

- Quatre épices (France)

- Ras el hanout (North Africa)

- Sharena sol (literally "colorful salt", Bulgaria)

- Shichimi tōgarashi (Japan)

- Speculaas (Belgium and Netherlands)

- Thuna Paha (Sri Lanka)

- Vegeta (Croatia)

- Za'atar (Middle East)

Handling

For ground spices, to grind a whole spice, the classic tool is mortar and pestle. Less labor-intensive tools are more common now: a microplane or fine grater can be used to grind small amounts; a coffee grinder[note 2] is useful for larger amounts. A frequently used spice such as black pepper may merit storage in its own hand grinder or mill.

The flavor of a spice is derived in part from compounds (volatile oils) that oxidize or evaporate when exposed to air. Grinding a spice greatly increases its surface area and so increases the rates of oxidation and evaporation. Thus, the flavor is maximized by storing a spice whole and grinding when needed. The shelf life of a whole dry spice is roughly two years; of a ground spice roughly six months.[24] The "flavor life" of a ground spice can be much shorter.[note 3] Ground spices are better stored away from light.[note 4]

Some flavor elements in spices are soluble in water; many are soluble in oil or fat. As a general rule, the flavors from a spice take time to infuse into the food so spices are added early in preparation. This contrasts to herbs which are usually added late in preparation.[24]

Salmonella contamination

A study by the Food and Drug Administration of shipments of spices to the United States during fiscal years 2007–2009 showed about 7% of the shipments were contaminated by Salmonella bacteria, some of it antibiotic-resistant.[25] As most spices are cooked before being served salmonella contamination often has no effect, but some spices, particularly pepper, are often eaten raw and present at table for convenient use. Shipments from Mexico and India, a major producer, were the most frequently contaminated.[26] Food irradiation is said to minimise this risk.[27][28]

Health research

Spices have been claimed to have health effects during both ancient and current times;[17] for example, in 2017, the Washington Post said spices put "a natural pharmacy in your kitchen".[17] The supposed health benefits include antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, and benefits towards certain diseases.[2] A 2019 systematic review looked at studies of 25 spices and concluded that there is not enough evidence yet to support these supposed benefits, and that "further work is needed".[2] The review noted that many studies were conducted by administering capsule or "artificial" forms of the spices, but spices are not normally consumed in this manner, and are normally consumed along other foods.[2] Spices may reduce the need for salt as a flavoring agent in dishes, which has cardiovascular benefits.[29]

Production

| Rank | Country | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | India | 1,474,900 | 1,525,000 |

| 2 | Bangladesh | 128,517 | 139,775 |

| 3 | Turkey | 107,000 | 113,783 |

| 4 | China | 90,000 | 95,890 |

| 5 | Pakistan | 53,647 | 53,620 |

| 6 | Iran | 18,028 | 21,307 |

| 7 | Nepal | 20,360 | 20,905 |

| 8 | Colombia | 16,998 | 19,378 |

| 9 | Ethiopia | 27,122 | 17,905 |

| 10 | Sri Lanka | 8,293 | 8,438 |

| — | World | 1,995,523 | 2,063,472 |

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organization[30] | |||

Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization addresses spices and condiments, along with related food additives, as part of the International Classification for Standards 67.220 series.[31]

Research

The Indian Institute of Spices Research in Kozhikode, Kerala, is devoted exclusively to conducting research for ten spice crops: black pepper, cardamom, cinnamon, clove, garcinia, ginger, nutmeg, paprika, turmeric, and vanilla.

Gallery

-

The Gato Negro café and spice shop (Buenos Aires, Argentina)

-

A spice shop selling a variety of spices in Iran

-

Night spice shop in Casablanca, Morocco

-

A spice shop in Taliparamba, India

-

Spices sold in Taliparamba, India

-

Spice seller, Kashgar market

-

Spice market, Marrakesh, Morocco

See also

- List of Indian spices – Variety of spices grown across the Indian subcontinent

- List of culinary herbs and spices

- Outline of herbs and spices

- Seasoning – Process of supplementing food via herbs, salts, or spices

- Spice mix

- Spice use in Antiquity

Notes

- ^ A team of archaeologists led by Giorgio Buccellati excavating the ruins of a burned-down house at the site of Terqa, in modern-day Syria, found a ceramic pot containing a handful of cloves. The house had burned down around 1720 BC and this was the first evidence of cloves being used in the west before Roman times.[7][8][9]

- ^ Other types of coffee grinders, such as a burr mill, can grind spices just as well as coffee beans.

- ^ Nutmeg, in particular, suffers from grinding and the flavor will degrade noticeably in a matter of days.

- ^ Light contributes to oxidation processes.

References

- ^ Ahmad, Hafsa; Khera, Rasheed Ahmad; Hanif, Muhammad Asif; Ayub, Muhammad Adnan; Jilani, Muhammad Idrees (2020). "Vanilla". Medicinal Plants of South Asia. pp. 657–669. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102659-5.00048-3. ISBN 978-0-08-102659-5. S2CID 241855294.

- ^ a b c d Rosa Vázquez-Fresno et al., "Herbs and Spices- Biomarkers of Intake Based on Human Intervention Studies – A Systematic Review", Genes and Nutrition 14:18 doi:10.1186/s12263-019-0636-8

- ^ a b c d "Definition of SPICE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c "spice - Middle English Compendium". quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Steven E. Sidebotham (May 7, 2019). Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-30338-6.

- ^ a b Murdock, Linda (2001). A Busy Cook's Guide to Spices: How to Introduce New Flavors to Everyday Meals. Bellwether Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-9704285-0-9.

- ^ Daniel T. Potts (1997), Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. A&C Black publishers, p. 269

- ^ Buccellati, G., M. Kelly-Buccellati, Terqa: The First Eight Seasons, Les Annales Archeologiques Arabes Syriennes 33(2), 1983, 47-67

- ^ O'Connell, John (2016). The Book of Spice: From Anise to Zedoary. Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1-68177-152-6.

- ^ Duke, J.A. (2002). CRC Handbook of Medicinal Spices. CRC Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4200-4048-7. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ Woodward, Penny (2003). "Herbs and Spices". In Katz (ed.). Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. Vol. 2. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 187–195.

- ^ Burkill, I.H. (1966). A Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula. Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Agriculture and Co-Operatives.

- ^ a b Freedman, Paul (June 5, 2015). "Health, wellness and the allure of spices in the Middle Ages". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. Potent Substances: On the Boundaries of Food and Medicine. 167: 47–53. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.065. PMID 25450779.

- ^ Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2004). Food in Medieval Times. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-313-32147-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Paul Freedman, Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination, 2008, ISBN 9780300151350, p. 2-3

- ^ Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, p. 453, Gil Marks, John Wiley & Sons, 2010. ISBN 978-0-470-39130-3

- ^ a b c Dennett, Carrie (January 26, 2017). "How a full spice cabinet can keep you healthy". The Washington Post.

- ^ Thomas, Frédéric; Daoust, Simon P.; Raymond, Michel (June 2012). "Can we understand modern humans without considering pathogens?: Human evolution and parasites". Evolutionary Applications. 5 (4): 368–379. doi:10.1111/j.1752-4571.2011.00231.x. PMC 3353360. PMID 25568057.

- ^ Paul Freedman, "Food Histories of the Middle Ages", in Kyri W. Claflin, Peter Scholliers, Writing Food History: A Global Perspective, ISBN 1847888097, p. 24

- ^ Andrew Dalby, Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices, 2000, ISBN 0520236742, p. 156

- ^ Andrew Jotischky, A Hermit's Cookbook: Monks, Food and Fasting in the Middle Ages, 2011, ISBN 1441159916, p. 170

- ^ a b c Michael Krondl, The Taste of Conquest: The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spice, 2007, ISBN 9780345480835, p. 6

- ^ Shelef, L.A. (1984). "Antimicrobial Effects of Spices". Journal of Food Safety. 6 (1): 29–44. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4565.1984.tb00477.x.

- ^ a b Host: Alton Brown (January 14, 2004). "Spice Capades". Good Eats. Season 7. Episode 14. Food Network.

- ^ Van Dorena, Jane M.; Daria Kleinmeiera; Thomas S. Hammack; Ann Westerman (June 2013). "Prevalence, serotype diversity, and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella in imported shipments of spice offered for entry to the United States, FY2007–FY2009". Food Microbiology. 34 (2): 239–251. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2012.10.002. PMID 23541190.

Shipments of imported spices offered for entry to the United States were sampled during the fiscal years 2007–2009. The mean shipment prevalence for Salmonella was 0.066 (95% CI 0.057–0.076)

- ^ Gardiner Harris (August 27, 2013). "Salmonella in Spices Prompts Changes in Farming". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Calucci, L.; Pinzino, C.; Zandomeneghi, M.; Capocchi, A.; Ghiringhelli, S.; Saviozzi, F.; Tozzi, S.; Galleschi, L. (2003). "Effects of gamma-irradiation on the free radical and antioxidant contents in nine aromatic herbs and spices". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (4): 927–34. doi:10.1021/jf020739n. PMID 12568551.

- ^ Anonymous (June 28, 2017). "Myths about Food Irradiation". Center for Consumer Research. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Cheryl AM; Cobb, Laura K; Miller, Edgar R; Woodward, Mark; Hottenstein, Annette; Chang, Alex R; Mongraw-Chaffin, Morgana; White, Karen; Charleston, Jeanne; Tanaka, Toshiko; Thomas, Letitia; Appel, Lawrence J (September 1, 2015). "Effects of a behavioral intervention that emphasizes spices and herbs on adherence to recommended sodium intake: results of the SPICE randomized clinical trial". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 102 (3): 671–679. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.100750. ISSN 0002-9165. PMC 4548171. PMID 26269371.

- ^ "Production of Spice by countries". UN Food & Agriculture Organization. 2011. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "67.220: Spices and condiments. Food additives". International Organization for Standardization. 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

Further reading

Books

- Czarra, Fred (2009). Spices: A Global History. Reaktion Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-86189-426-7.

- Dalby, Andrew (2000). Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23674-5.

- Freedman, Paul (2008). Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21131-3.

- Keay, John (2006). The Spice Route: A History. John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6199-3.

- Krondl, Michael (2008). The Taste of Conquest: The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spice. Random House. ISBN 978-0-345-50982-6.

- Miller, James Innes (1969). The spice trade of the Roman Empire, 29 B.C. to A.D. 641. Oxford: Clarendon P. ISBN 978-0-19-814264-5.

- Morton, Timothy (2006). The Poetics of Spice: Romantic Consumerism and the Exotic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02666-6.

- Seidemann, Johannes (2005). World Spice Plants: Economic Usage, Botany, Taxonomy. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-22279-8.

- Turner, Jack (2004). Spice: The History of a Temptation. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-40721-5.