Christmas: Difference between revisions

Stevensaylor (talk | contribs) →History: Removal of clause that makes no sense (and contradicts the information in the section directly below, which section renders this clause unnecessary in any case). |

m date formats per MOS:DATEFORMAT by script not sure why Davey changed the date format without explaining why. Restoring per WP:DATERET |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

{{pp-move-indef}} |

||

{{Use |

{{Use mdy dates|date=December 2016}} |

||

{{Infobox holiday |

{{Infobox holiday |

||

| holiday_name = Christmas<br/><small>Christmas Day</small> |

| holiday_name = Christmas<br/><small>Christmas Day</small> |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| caption = A [[nativity scene|depiction]] of the [[Nativity of Jesus]] with a [[Christmas tree]] backdrop |

| caption = A [[nativity scene|depiction]] of the [[Nativity of Jesus]] with a [[Christmas tree]] backdrop |

||

| nickname = Noël, [[Nativity of Jesus|Nativity]], [[Xmas]], [[Yule]] |

| nickname = Noël, [[Nativity of Jesus|Nativity]], [[Xmas]], [[Yule]] |

||

| observedby = [[Christian]]s, many non-Christians<ref name="nonXians">[http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/learningenglish/entertainment/scripts/multifaith_christmas.pdf Christmas as a Multi-faith Festival]—BBC News. Retrieved |

| observedby = [[Christian]]s, many non-Christians<ref name="nonXians">[http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/learningenglish/entertainment/scripts/multifaith_christmas.pdf Christmas as a Multi-faith Festival]—BBC News. Retrieved September 30, 2008.</ref><ref name="NonXiansUSA">{{cite web|url = http://www.gallup.com/poll/113566/us-christmas-not-just-christians.aspx|title = In the U.S., Christmas Not Just for Christians|publisher = Gallup, Inc.|date = December 24, 2008|accessdate=December 16, 2012}}</ref> |

||

| date = * |

| date = * December 25<br/>''[[Western Christianity]] and some [[Eastern Christianity|Eastern]] churches; secular world'' |

||

* {{OldStyleDate| |

* {{OldStyleDate|January 7||December 25}}<br/>''Some Eastern churches''<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/?id=tdsRKc_knZoC&pg=RA5-PT130 |first=Paul |last=Gwynne |title=World Religions in Practice |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=2011 |isbn=978-1-44436005-9}}</ref><ref name="Jan7">{{cite web |url=http://www.copticchurch.net/topics/coptic_calendar/nativitydate.html |title=The Glorious Feast of Nativity: 7 January? 29 Kiahk? 25 December? |publisher=Coptic Orthodox Church Network |first=John |last=Ramzy |accessdate=January 17, 2011}}</ref>'' |

||

* |

* January 6<br/>''[[Armenian Apostolic Church|Armenian Apostolic]] and [[Armenian Evangelical Church|Armenian Evangelical]] Churches<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=EDO5bcaMvUIC&pg=PT27 |title=The Feast of Christmas |publisher=Liturgical Press |isbn=978-0-8146-3932-0|last=Kelly|first=Joseph F|year=2010}}</ref>'' |

||

* {{OldStyleDate| |

* {{OldStyleDate|January 19||January 6}}<br/>''[[Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem]]''<ref>{{cite news|last=Jansezian|first=Nicole|title=10 things to do over Christmas in the Holy Land|url=http://www.jpost.com/Travel/Around-Israel/10-things-to-do-over-Christmas-in-the-Holy-Land|work=[[The Jerusalem Post]]|quote=...the Armenians in Jerusalem – and only in Jerusalem – celebrate Christmas on January 19...}}</ref>'' |

||

| observances = [[Church service]]s |

| observances = [[Church service]]s |

||

| celebrations = Gift-giving, family and other social gatherings, symbolic decoration, feasting etc. |

| celebrations = Gift-giving, family and other social gatherings, symbolic decoration, feasting etc. |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

<!--Please review talk archives before altering the opening line and make good use of the talk pages.--> |

<!--Please review talk archives before altering the opening line and make good use of the talk pages.--> |

||

'''Christmas''' or '''Christmas Day''' ({{lang-ang|Crīstesmæsse}}, meaning "[[Christ (title)|Christ]]'s [[Mass (liturgy)|Mass]]") is an annual festival commemorating [[Nativity of Jesus|the birth]] of [[Jesus|Jesus Christ]],<ref>[http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/christmas Christmas], ''[[Merriam-Webster]]''. Retrieved 2008-10-06.<br />[http://www.webcitation.org/5kwKlFgsB?url=http%3A%2F%2Fencarta.msn.com%2Fencnet%2Frefpages%2FRefArticle.aspx%3Frefid%3D761556859 Archived] 2009-10-31.</ref><ref name="CathChrit">Martindale, Cyril Charles.[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm "Christmas"]. ''[[The Catholic Encyclopedia]]''. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908.</ref> observed most commonly on |

'''Christmas''' or '''Christmas Day''' ({{lang-ang|Crīstesmæsse}}, meaning "[[Christ (title)|Christ]]'s [[Mass (liturgy)|Mass]]") is an annual festival commemorating [[Nativity of Jesus|the birth]] of [[Jesus|Jesus Christ]],<ref>[http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/christmas Christmas], ''[[Merriam-Webster]]''. Retrieved 2008-10-06.<br />[http://www.webcitation.org/5kwKlFgsB?url=http%3A%2F%2Fencarta.msn.com%2Fencnet%2Frefpages%2FRefArticle.aspx%3Frefid%3D761556859 Archived] 2009-10-31.</ref><ref name="CathChrit">Martindale, Cyril Charles.[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm "Christmas"]. ''[[The Catholic Encyclopedia]]''. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908.</ref> observed most commonly on December 25<ref name="Jan7"/><ref name="altdays">Several branches of [[Eastern Christianity]] that use the [[Julian calendar]] also celebrate on December 25 according to that calendar, which is now January 7 on the [[Gregorian calendar]]. Armenian Churches observed the nativity on January 6 even before the Gregorian calendar originated. Most Armenian Christians use the Gregorian calendar, still celebrating Christmas Day on January 6. Some Armenian churches use the Julian calendar, thus celebrating Christmas Day on January 19 on the Gregorian calendar, with January 18 being Christmas Eve.</ref><ref name=4Dates /> as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world.<ref name="NonXiansUSA" /><ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-christians/|title = The Global Religious Landscape <nowiki>|</nowiki> Christians|publisher = Pew Research Center|date = December 18, 2012|accessdate = May 23, 2014}}</ref><ref name="Gallup122410">{{cite web|url = http://www.gallup.com/poll/145367/christmas-strongly-religious-half-celebrate.aspx|title = Christmas Strongly Religious For Half in U.S. Who Celebrate It|publisher = Gallup, Inc.|date = December 24, 2010|accessdate = December 16, 2012}}</ref> A [[feast day|feast]] central to the [[Christianity|Christian]] [[liturgical year]], it is prepared for by the season of [[Advent]] or the [[Nativity Fast]] and initiates the season of [[Christmastide]], which historically in the West lasts [[Twelve Days of Christmas|twelve days]] and culminates on [[Twelfth Night (holiday)|Twelfth Night]];<ref name="Forbes">{{cite book|last=Forbes|first=Bruce David|title=Christmas: A Candid History|date=October 1, 2008|publisher=[[University of California Press]]|isbn=978-0-520-25802-0|page=27|quote=In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide. On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself. After Christmas and Epiphany were in place, on December 25 and January 6, with the twelve days of Christmas in between, Christians gradually added a period called Advent, as a time of spiritual preparation leading up to Christmas.}}<!--|accessdate=December 7, 2015--></ref> in some traditions, Christmastide includes an [[Octave (liturgical)|Octave]].<ref name="Senn2012">{{cite book|last=Senn|first=Frank C.|title=Introduction to Christian Liturgy|year=2012|publisher=Fortress Press|isbn=978-1-4514-2433-1|page=145|quote=We noted above that late medieval calendars introduced a reduced three-day octave for Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost that were retained in Roman Catholic and passed into Lutheran and Anglican calendars.}}<!--|accessdate=December 8, 2015--></ref> The traditional Christmas narrative, the [[Nativity of Jesus]], delineated in the [[New Testament]] says that Jesus was born in [[Bethlehem]], in accordance with [[Christian messianic prophecies|messianic prophecies]];<ref name="Crump2001">{{cite book|last=Crump|first=William D.|title=The Christmas Encyclopedia|accessdate=December 17, 2016|edition=3|date=September 15, 2001|publisher=McFarland|language=English |isbn=9780786468270|page=39|quote=Christians believe that a number of passages in the Bible are prophecies about future events in the life of the promised Messiah or Jesus Christ. Most, but not all, of those prophecies are found in the Old Testament ... ''Born in Bethlehem'' (Micah 5:2): "But thou, Bethlehem Ephratah, ''though'' though be little among the thousands of Juda, ''yet'' out of thee shall he come forth unto me ''that is'' to be ruler in Israel; whose goings forth ''have been'' from of old, from everlasting."}}</ref> when [[Saint Joseph|Joseph]] and [[Mary, mother of Jesus|Mary]] arrived in the city, the inn had no room and so they were offered a [[manger|stable]] where the [[Christ Child]] was soon born, with [[angels]] proclaiming this news to shepherds who then disseminated the message furthermore.<ref name="Tucker2011">{{cite book|last=Tucker|first=Ruth A.|title=Parade of Faith: A Biographical History of the Christian Church|accessdate=December 17, 2016|year=2011|publisher=Zondervan|language=English |isbn=9780310206385|page=23|quote=According to gospel accounts, Jesus was born during the reign of Herod the Great, thus sometime before 4 BCE. The birth narrative in Luke's gospel is one of the most familiar passages in the Bible. Leaving their hometown of Nazareth, Mary and Joseph travel to Bethlehem to pay taxes. Arriving late, they find no vacancy at the inn. But they are offered a stable, most likely a second room attached to a family dwelling where animals were sheltered—a room that would offer some privacy from the main family room for cooking, eating, and sleeping. ... This "city of David" is the ''little town of Bethlehem'' of Christmas-carol fame, a starlit silhouette indelibly etched on Christmas cards. No sooner was the baby born than angels announced the news to shepherds who spread the word.}}</ref> Christmas Day is a public [[holiday]] in [[List of holidays by country|many of the world's nations]],<ref>[http://www.pch.gc.ca/pgm/ceem-cced/jfa-ha/index-eng.cfm Canadian Heritage – Public holidays] – ''Government of Canada''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref><ref>[http://www.opm.gov/Operating_Status_Schedules/fedhol/2009.asp 2009 Federal Holidays] – ''U.S. Office of Personnel Management''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref><ref>[http://www.direct.gov.uk/en/Governmentcitizensandrights/LivingintheUK/DG_073741 Bank holidays and British Summer time] – ''HM Government''. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref> is celebrated religiously by the vast majority of Christians,<ref name="EhornHewlett1995">{{cite book|last1=Ehorn|first1=Lee Ellen|last2=Hewlett|first2=Shirely J.|last3=Hewlett|first3=Dale M.|title=December Holiday Customs |accessdate=December 17, 2016|date=September 1, 1995|publisher=Lorenz Educational Press|language=English|isbn=9781429108966|page=1}}</ref> as well as culturally by a number of non-Christian people,<ref name="nonXians"/><ref>[http://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-1100842/Why-I-celebrate-Christmas-worlds-famous-atheist.html Why I celebrate Christmas, by the world's most famous atheist] – ''Daily Mail''. December 23, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2010.</ref><ref>[http://www.siouxcityjournal.com/lifestyles/leisure/article_9914761e-ce50-11de-98cf-001cc4c03286.html Non-Christians focus on secular side of Christmas] – ''Sioux City Journal''. Retrieved November 18, 2009.</ref> and is an integral part of the [[Christmas and holiday season|holiday season]], while some Christian groups reject the celebration. In several countries, celebrating [[Christmas Eve]] on December 24 has the main focus rather than December 25, with gift-giving and sharing a traditional meal with the family. |

||

Although the month and date of Jesus' birth are unknown, by the early-to-mid 4th century the [[Western Christian Church]] had placed Christmas on |

Although the month and date of Jesus' birth are unknown, by the early-to-mid 4th century the [[Western Christian Church]] had placed Christmas on December 25,<ref>[https://books.google.com/books/about/Sourcebook_for_Sundays_Seasons_and_Weekd.html?id=kQWbWCXMGQgC Google Books] Sourcebook for Sundays, Seasons, and Weekdays 2011: The Almanac for Pastoral Liturgy by Corinna Laughlin, Michael R. Prendergast, Robert C. Rabe, Corinna Laughlin, Jill Maria Murdy, Therese Brown, Mary Patricia Storms, Ann E. Degenhard, Jill Maria Murdy, Ann E. Degenhard, Therese Brown, Robert C. Rabe, Mary Patricia Storms, Michael R. Prendergast – LiturgyTrainingPublications, March 26, 2010 – page 29</ref> a date which was later adopted in the East.<ref name="Chrono354">[http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_12_depositions_martyrs.htm The Chronography of 354 AD. Part 12: Commemorations of the Martyrs] – ''The Tertullian Project''. 2006. Retrieved November 24, 2011.</ref><ref name="SusanKOrigins">Roll, Susan K., ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=6MXPEMbpjoAC&pg=PA133&lpg=PA133&dq=&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false Toward the Origins of Christmas]'', (Peeters Publishers, 1995), p.133.</ref> Today, most Christians celebrate on December 25 in the [[Gregorian calendar]], which has been adopted almost universally in the [[civil calendar]]s used in countries throughout the world. However, some [[Eastern Christian Churches]] celebrate Christmas on December 25 of the older [[Julian calendar]], which currently corresponds to January 7 in the Gregorian calendar, the day after the Western Christian Church celebrates the [[Epiphany (holiday)|Epiphany]]. This is not a disagreement over the date of Christmas as such, but rather a preference of which calendar should be used to determine the day that is December 25. In the [[Council of Tours]] of 567, the Church, with its desire to be universal, "declared the [[Twelve Days of Christmas|twelve days]] between Christmas and Epiphany to be one [[Christmastide|unified festal cycle]]", thus giving significance to both the Western and Eastern dates of Christmas.<ref name="Forbes08">{{cite book|last=Forbes|first=Bruce David|title=Christmas: A Candid History|accessdate=December 15, 2014|date=October 1, 2008|publisher=[[University of California Press]]|isbn=978-0-520-25802-0|page=27|quote=In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide. On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself. After Christmas and Epiphany were in place, on December 25 and January 6, with the twelve days of Christmas in between, Christians gradually added a period called Advent, as a time of spiritual preparation leading up to Christmas.}}</ref><ref name="Hynes1993">{{cite book|last=Hynes|first=Mary Ellen|title=Companion to the Calendar|accessdate=December 15, 2014|year=1993|publisher=Liturgy Training Publications|isbn=978-1-56854-011-5|page=8|quote=In the year 567 the church council of Tours called the 13 days between December 25 and January 6 a festival season. Up until that time the only other joyful church season was the 50 days between Easter Sunday and Pentecost.}}</ref><ref name=Knight>{{cite web|url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm|title=Christmas|last=Knight|first=Kevin|year=2012|work=The Catholic Encyclopedia|publisher=New Advent|accessdate=December 15, 2014|quote=The Second Council of Tours (can. xi, xvii) proclaims, in 566 or 567, the sanctity of the "twelve days" from Christmas to Epiphany, and the duty of Advent fast; that of Agde (506), in canons 63–64, orders a universal communion, and that of Braga (563) forbids fasting on Christmas Day. Popular merry-making, however, so increased that the "Laws of King Cnut", fabricated c. 1110, order a fast from Christmas to Epiphany.}}</ref><ref name="Hill2003">{{cite book|last=Hill|first=Christopher|title=Holidays and Holy Nights: Celebrating Twelve Seasonal Festivals of the Christian Year|accessdate=December 15, 2014|year=2003|publisher=Quest Books|isbn=978-0-8356-0810-7|page=91|quote=This arrangement became an administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east. While the Romans could roughly match the months in the two systems, the four cardinal points of the solar year—the two equinoxes and solstices—still fell on different dates. By the time of the first century, the calendar date of the winter solstice in Egypt and Palestine was eleven to twelve days later than the date in Rome. As a result the Incarnation came to be celebrated on different days in different parts of the Empire. The Western Church, in its desire to be universal, eventually took them both—one became Christmas, one Epiphany—with a resulting twelve days in between. Over time this hiatus became invested with specific Christian meaning. The Church gradually filled these days with saints, some connected to the birth narratives in Gospels (Holy Innocents' Day, December 28, in honor of the infants slaughtered by Herod; St. John the Evangelist, "the Beloved," December 27; St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, December 26; the Holy Family, December 31; the Virgin Mary, January 1). In 567, the Council of Tours declared the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany to become one unified festal cycle.}}</ref><ref name=Bunson>{{cite web|url=http://www.ewtn.com/vexperts/showmessage_print.asp?number=518618&language=en|title=Origins of Christmas and Easter holidays|last=Bunson|first=Matthew|date=October 21, 2007|publisher=[[Eternal Word Television Network]] (EWTN)|accessdate=December 17, 2014|quote=The Council of Tours (567) decreed the 12 days from Christmas to Epiphany to be sacred and especially joyous, thus setting the stage for the celebration of the Lord's birth not only in a liturgical setting but in the hearts of all Christians.}}</ref> Moreover, for Christians, the belief that [[God the Son|God]] came into the world in the [[Incarnation (Christianity)|form of man]] to [[Atonement in Christianity|atone]] for the [[sin]]s of humanity, rather than the exact birth date, is considered to be the primary purpose in celebrating Christmas.<ref name="Joan Chittister, Phyllis Tickle">{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/?id=inhMGc5732kC&pg=PT40&dq=date+of+christmas+important#v=onepage&q=date%20of%20christmas%20important&f=false| title = The Liturgical Year|publisher = [[Thomas Nelson (publisher)|Thomas Nelson]]|quote=Christmas is not really about the celebration of a birth date at all. It is about the celebration of a birth. The fact of the date and the fact of the birth are two different things. The calendrical verification of the feast itself is not really that important ... What is important to the understanding of a life-changing moment is that it happened, not necessarily where or when it happened. The message is clear: Christmas is not about marking the actual birth date of Jesus. It is about the Incarnation of the One who became like us in all things but sin (Heb. 4:15) and who humbled Himself "to the point of death-even death on a cross" (Phil. 2:8). Christmas is a pinnacle feast, yes, but it is not the beginning of the liturgical year. It is a memorial, a remembrance, of the birth of Jesus, not really a celebration of the day itself. We remember that because the Jesus of history was born, the Resurrection of the Christ of faith could happen. |accessdate = April 2, 2009| isbn = 978-1-4185-8073-5| date = November 3, 2009}}</ref><ref name="Voice-Christmas">{{cite web|url = http://www.crivoice.org/cyxmas.html| title = The Christmas Season|publisher = CRI / Voice, Institute|accessdate = April 2, 2009|quote=The origins of the celebrations of Christmas and Epiphany, as well as the dates on which they are observed, are rooted deeply in the history of the early church. There has been much scholarly debate concerning the exact time of the year when Jesus was born, and even in what year he was born. Actually, we do not know either. The best estimate is that Jesus was probably born in the springtime, somewhere between the years of 6 and 4 BC, as December is in the middle of the cold rainy season in [[Bethlehem]], when the sheep are kept inside and not on pasture as told in the Bible. The lack of a consistent system of timekeeping in the first century, mistakes in later calendars and calculations, and lack of historical details to cross reference events has led to this imprecision in fixing Jesus' birth. This suggests that the Christmas celebration is not an observance of a historical date, but a commemoration of the event in terms of worship.}}</ref><ref name="Harvard University">{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/?id=x_kBAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA469&dq=date+of+christmas+unimportant#v=onepage&q=date%20of%20christmas%20unimportant&f=false| title = The School Journal, Volume 49|publisher = [[Harvard University]]|quote=Throughout the Christian world the 25th of December is celebrated as the birthday of Jesus Christ. There was a time when the churches were not united regarding the date of the joyous event. Many Christians kept their Christmas in April, others in May, and still others at the close of September, till finally December 25 was agreed upon as the most appropriate date. The choice of that day was, of course, wholly arbitrary, for neither the exact date not the period of the year at which the birth of Christ occurred is known. For purposes of commemoration, however, it is unimportant whether the celebration shall fall or not at the precise anniversary of the joyous event.|accessdate = April 2, 2009| year = 1894}}</ref><ref name="McGrath2006">{{cite book|author=[[Alister McGrath]]|title=Christianity: An Introduction|accessdate=December 17, 2016|date=February 13, 2006|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|language=English |isbn=9781405108997|page=15|quote=For Christians, the precise date of the birth of Jesus is actually something of a non-issue. What really matters is that he was born as a human being, and entered into human history.}}</ref> |

||

Although it is not known why |

Although it is not known why December 25 became a date of celebration, there are several factors that may have influenced the choice. December 25 was the date the Romans marked as the winter solstice,<ref name="SolsticeDate" /> and Jesus was identified with the Sun based on an Old Testament verse.<ref name="Newton">Newton, Isaac, ''[http://www.gutenberg.org/files/16878/16878-h/16878-h.htm Observations on the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John]'' (1733). Ch. XI. A sun connection is possible because Christians considered Jesus to be the "Sun of righteousness" prophesied in Malachi 4:2: "But for you who fear my name, the sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings. You shall go out leaping like calves from the stall."</ref> The date is exactly nine months following [[Annunciation]], when the conception of Jesus is celebrated.<ref name="bib-arch.org">{{cite web |

||

|last=McGowan |

|last=McGowan |

||

|first=Andrew |

|first=Andrew |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

|title=How December 25 Became Christmas |

|title=How December 25 Became Christmas |

||

|magazine=Bible Review & Bible History Daily |

|magazine=Bible Review & Bible History Daily |

||

|publisher=[[Biblical Archaeology Society]] |accessdate= |

|publisher=[[Biblical Archaeology Society]] |accessdate=February 24, 2011}}</ref><ref name="Touchstone">{{cite journal |last1=Tighe |first1=William J. |title=Calculating Christmas |journal=[[Touchstone (magazine)|Touchstone]] |year=2003 |volume=16 |issue=10 |url=http://touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=16-10-012-v}}</ref> Finally, the Romans had a series of pagan festivals near the end of the year, so Christmas may have been scheduled at this time to appropriate, or compete with, one or more of these festivals.<ref name="SolInvictus">"[http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761556859_1____4/christmas.html#s4 Christmas]", ''[[Encarta]]''. [http://www.webcitation.org/5kwR1OTxS Archived] 2009-10-31.<br/>{{cite book |

||

|last=Roll |

|last=Roll |

||

|first=Susan K. |

|first=Susan K. |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

|publisher=Peeters Publishers |year=1995 |page=130}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Robert Laurence Moore|title=Selling God: American religion in the marketplace of culture|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|year=1994|page=205| quote=When the Catholic Church in the fourth century singled out December 25 as the birth date of Christ, it tried to stamp out the Saturnalia common to the solstice season.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Encyclopedia|publisher=[[Merriam Webster]]|year=2000|page=1211| quote=Christian missionaries frequently sought to stamp out pagan practices by building churches on the sites of pagan shrines or by associated Christian holidays with pagan rituals (eg. linking -Christmas with the celebration of the winter solstice).}}</ref> |

|publisher=Peeters Publishers |year=1995 |page=130}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Robert Laurence Moore|title=Selling God: American religion in the marketplace of culture|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|year=1994|page=205| quote=When the Catholic Church in the fourth century singled out December 25 as the birth date of Christ, it tried to stamp out the Saturnalia common to the solstice season.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Encyclopedia|publisher=[[Merriam Webster]]|year=2000|page=1211| quote=Christian missionaries frequently sought to stamp out pagan practices by building churches on the sites of pagan shrines or by associated Christian holidays with pagan rituals (eg. linking -Christmas with the celebration of the winter solstice).}}</ref> |

||

The celebratory customs associated in various countries with Christmas have a mix of [[wikt:pre-Christian|pre-Christian]], Christian, and [[secularity|secular]] themes and origins.<ref>{{cite book|author=|title=West's Federal Supplement|publisher=[[West Publishing Company]]|year=1990|quote=While the Washington and King birthdays are exclusively secular holidays, Christmas has both secular and religious aspects.}}</ref> Popular modern customs of the holiday include [[Gift economy|gift giving]], completing an [[Advent calendar]] or [[Advent wreath]], [[Christmas music]] and [[Christmas carol|caroling]], lighting a [[Christingle]], an exchange of [[Christmas card]]s, [[church service]]s, a [[List of Christmas dishes|special meal]], and the display of various [[Christmas decoration]]s, including [[Christmas tree]]s, [[Christmas lights]], [[nativity scene]]s, [[garland]]s, [[wreath]]s, [[mistletoe]], and [[holly]]. In addition, several closely related and often interchangeable figures, known as [[Santa Claus]], [[Father Christmas]], [[Saint Nicholas]], and [[Christkind]], are associated with bringing gifts to children during the Christmas season and have their own body of [[Christmas traditions|traditions]] and lore.<ref>[http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/16329025 "Poll: In a changing nation, Santa endures"], Associated Press, |

The celebratory customs associated in various countries with Christmas have a mix of [[wikt:pre-Christian|pre-Christian]], Christian, and [[secularity|secular]] themes and origins.<ref>{{cite book|author=|title=West's Federal Supplement|publisher=[[West Publishing Company]]|year=1990|quote=While the Washington and King birthdays are exclusively secular holidays, Christmas has both secular and religious aspects.}}</ref> Popular modern customs of the holiday include [[Gift economy|gift giving]], completing an [[Advent calendar]] or [[Advent wreath]], [[Christmas music]] and [[Christmas carol|caroling]], lighting a [[Christingle]], an exchange of [[Christmas card]]s, [[church service]]s, a [[List of Christmas dishes|special meal]], and the display of various [[Christmas decoration]]s, including [[Christmas tree]]s, [[Christmas lights]], [[nativity scene]]s, [[garland]]s, [[wreath]]s, [[mistletoe]], and [[holly]]. In addition, several closely related and often interchangeable figures, known as [[Santa Claus]], [[Father Christmas]], [[Saint Nicholas]], and [[Christkind]], are associated with bringing gifts to children during the Christmas season and have their own body of [[Christmas traditions|traditions]] and lore.<ref>[http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/16329025 "Poll: In a changing nation, Santa endures"], Associated Press, December 22, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2009.</ref> Because gift-giving and many other aspects of the Christmas festival involve heightened economic activity, the holiday has become a significant event and a key sales period for retailers and businesses. The economic impact of Christmas has grown steadily over the past few centuries in many regions of the world. |

||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

"Christmas" is a shortened form of "[[Christ]]'s [[Mass (liturgy)|mass]]". It is derived from the [[Middle English]] ''Cristemasse'', which is from [[Old English language|Old English]] ''Crīstesmæsse'', a phrase first recorded in 1038<ref name="CathChrit"/> followed by the word ''Cristes-messe'' in 1131.<ref name="Christmas">Cyril Charles Martindale, [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm "Christmas"], in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3'', New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908 (accessed |

"Christmas" is a shortened form of "[[Christ]]'s [[Mass (liturgy)|mass]]". It is derived from the [[Middle English]] ''Cristemasse'', which is from [[Old English language|Old English]] ''Crīstesmæsse'', a phrase first recorded in 1038<ref name="CathChrit"/> followed by the word ''Cristes-messe'' in 1131.<ref name="Christmas">Cyril Charles Martindale, [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm "Christmas"], in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3'', New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908 (accessed December 21, 2012)</ref> ''Crīst'' ([[genitive case|genitive]] ''Crīstes'') is from Greek ''Khrīstos'' (Χριστός), a translation of [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] ''Māšîaḥ'' (מָשִׁיחַ), "[[Messiah]]", meaning "anointed";<ref>{{cite book|title=God's human face: the Christ-icon |first=Christoph |last=Schoenborn |year=1994 |isbn=0-89870-514-2 |page=154}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine |first=John |last=Galey |year=1986 |isbn=977-424-118-5 |page=92}}</ref> and ''mæsse'' is from Latin ''missa'', the celebration of the [[Eucharist]]. The form ''Christenmas'' was also historically used, but is now considered archaic and dialectal;<ref>''Christenmas, n.'', ''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]''. Retrieved December 12.</ref> it derives from Middle English ''Cristenmasse'', literally "Christian mass".<ref name=XMED>"Christmas" in the [http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/m/mec/med-idx?type=id&id=MED10371 Middle English Dictionary]</ref> ''[[Xmas]]'' is an abbreviation of ''Christmas'' found particularly in print, based on the initial letter [[chi (letter)|chi]] (Χ) in Greek ''Khrīstos'' (Χριστός), "Christ", though numerous [[style guides]] discourage its use;<ref>Griffiths, Emma, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/4097755.stm "Why get cross about Xmas?"], BBC, December 22, 2004. Retrieved December 12, 2011.</ref> it has precedent in Middle English ''Χρ̄es masse'' (where "Χρ̄" is an abbreviation for Χριστός).<ref name=XMED/> |

||

===Other names=== |

===Other names=== |

||

In addition to "Christmas", the holiday has been known by various other names throughout its history. The [[Anglo-Saxon]]s referred to the feast as "midwinter",<ref name="Hutton">Hutton, Ronald, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=H3PvQ5bqoBkC&pg=PT21&dq=#v=onepage&q&f=false The stations of the sun: a history of the ritual year]'', Oxford University Press, 2001.</ref><ref>"Midwinter" in [http://bosworth.ff.cuni.cz/022849 Bosworth & Toller]</ref> or, more rarely, as ''Nātiuiteð'' (from [[Latin language|Latin]] ''nātīvitās'' below).<ref name="Hutton"/><ref>Serjeantson, Mary Sidney, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=HZaxAAAAIAAJ&q=%22natiuited%22&dq=%22natiuited%22&hl=en&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2 A History of Foreign Words in English]''</ref> "[[Nativity of Jesus|Nativity]]", meaning "birth", is from Latin ''nātīvitās''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=nativity&searchmode=none|title=Online Etymology Dictionary}}</ref> In Old English, ''Gēola'' (''[[Yule]]'') referred to the period corresponding to December and January, which was eventually equated with Christian Christmas.<ref>[http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=yule&searchmode=none ''Yule''], Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved |

In addition to "Christmas", the holiday has been known by various other names throughout its history. The [[Anglo-Saxon]]s referred to the feast as "midwinter",<ref name="Hutton">Hutton, Ronald, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=H3PvQ5bqoBkC&pg=PT21&dq=#v=onepage&q&f=false The stations of the sun: a history of the ritual year]'', Oxford University Press, 2001.</ref><ref>"Midwinter" in [http://bosworth.ff.cuni.cz/022849 Bosworth & Toller]</ref> or, more rarely, as ''Nātiuiteð'' (from [[Latin language|Latin]] ''nātīvitās'' below).<ref name="Hutton"/><ref>Serjeantson, Mary Sidney, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=HZaxAAAAIAAJ&q=%22natiuited%22&dq=%22natiuited%22&hl=en&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2 A History of Foreign Words in English]''</ref> "[[Nativity of Jesus|Nativity]]", meaning "birth", is from Latin ''nātīvitās''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=nativity&searchmode=none|title=Online Etymology Dictionary}}</ref> In Old English, ''Gēola'' (''[[Yule]]'') referred to the period corresponding to December and January, which was eventually equated with Christian Christmas.<ref>[http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=yule&searchmode=none ''Yule''], Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved December 12.</ref> "Noel" (or "Nowel") entered English in the late 14th century and is from the Old French ''noël'' or ''naël'', itself ultimately from the Latin ''nātālis (diēs)'', "birth (day)".<ref>[http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=noel&searchmode=none ''Noel''] Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved December 12.</ref> |

||

==Nativity== |

==Nativity== |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

[[File:English luke2-1-20 tyndale mtd.ogg|thumb|start=25|Gospel according to St. Luke Chapter 2, v 1–20]] |

[[File:English luke2-1-20 tyndale mtd.ogg|thumb|start=25|Gospel according to St. Luke Chapter 2, v 1–20]] |

||

[[File:Gerard van Honthorst - Adoration of the Shepherds (1622).jpg|thumb|right|''Adoration of the Shepherds'' by Gerard van Honthorst depicts the nativity of [[Jesus]]]] |

[[File:Gerard van Honthorst - Adoration of the Shepherds (1622).jpg|thumb|right|''Adoration of the Shepherds'' by Gerard van Honthorst depicts the nativity of [[Jesus]]]] |

||

The [[canonical gospels]] of Luke and Matthew both describe Jesus as being born in [[Bethlehem]] in Judea, to a virgin mother. In the Gospel of Luke account, Joseph and Mary travel from [[Nazareth]] to Bethlehem for the census, and Jesus is born there and laid in a manger.<ref>"[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/64496/biblical-literature Biblical literature]." ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. |

The [[canonical gospels]] of Luke and Matthew both describe Jesus as being born in [[Bethlehem]] in Judea, to a virgin mother. In the Gospel of Luke account, Joseph and Mary travel from [[Nazareth]] to Bethlehem for the census, and Jesus is born there and laid in a manger.<ref>"[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/64496/biblical-literature Biblical literature]." ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. January 22, 2011.</ref> It says that angels proclaimed him a savior for all people, and shepherds came to adore him. In the Matthew account, magi [[Star of Bethlehem|follow a star]] to Bethlehem to bring gifts to Jesus, born the [[Jesus, King of the Jews|king of the Jews]]. [[Herod the Great|King Herod]] orders the [[Massacre of the Innocents|massacre of all the boys]] less than two years old in Bethlehem, but the family flees to Egypt and later settles in Nazareth. |

||

[[File:Nativity (15th c., Annunciation Cathedral in Moscow).jpg|thumb|[[Eastern Orthodox]] [[icon]] of the birth of Christ by [[Andrei Rublev|St. Andrei Rublev]], 15th century]] |

[[File:Nativity (15th c., Annunciation Cathedral in Moscow).jpg|thumb|[[Eastern Orthodox]] [[icon]] of the birth of Christ by [[Andrei Rublev|St. Andrei Rublev]], 15th century]] |

||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

[[File:Hortus Deliciarum, Die Geburt Christi.JPG|thumb|''Nativity of Christ'' – medieval illustration from the [[Hortus deliciarum]] of [[Herrad of Landsberg]] (12th century)]] |

[[File:Hortus Deliciarum, Die Geburt Christi.JPG|thumb|''Nativity of Christ'' – medieval illustration from the [[Hortus deliciarum]] of [[Herrad of Landsberg]] (12th century)]] |

||

The earliest known Christian festivals were attempts to celebrate Jewish holidays, especially Passover, according to the local calendar. Modern scholars refer to such holidays as "Quartodecimals" because Passover is dated as 14 Nisan on the Jewish calendar. All the major events of the life of Jesus were celebrated in this festival, including his conception, birth, and passion. In the Greek-speaking areas of the Roman Empire, the [[Macedonian calendar]] was used. In these areas, the Quartodecimal was celebrated on |

The earliest known Christian festivals were attempts to celebrate Jewish holidays, especially Passover, according to the local calendar. Modern scholars refer to such holidays as "Quartodecimals" because Passover is dated as 14 Nisan on the Jewish calendar. All the major events of the life of Jesus were celebrated in this festival, including his conception, birth, and passion. In the Greek-speaking areas of the Roman Empire, the [[Macedonian calendar]] was used. In these areas, the Quartodecimal was celebrated on April 6. In Latin-speaking areas, the Quartodecimal was March 25. The significance of the Quartodecimal declined after 165, when Pope Soter moved celebration of the Resurrection to a Sunday, thereby creating Easter. This put celebration of the passion on Good Friday, and thus moved it away from the Quartodecimal.<ref>Tally, pp. 2–4.</ref> |

||

The Christian ecclesiastical calendar contains many remnants of pre-Christian festivals. The later development of Christmas as a festival includes elements of the Roman feast of the [[Saturnalia]] and the birthday of [[Mithra]] as described in the Roman cult of [[Mithraism]].<ref>"The survival of Roman religion" in the section on the history of the [http://global.britannica.com/topic/Roman-religion Roman religion] in Encyclopaedia Britannica</ref> |

The Christian ecclesiastical calendar contains many remnants of pre-Christian festivals. The later development of Christmas as a festival includes elements of the Roman feast of the [[Saturnalia]] and the birthday of [[Mithra]] as described in the Roman cult of [[Mithraism]].<ref>"The survival of Roman religion" in the section on the history of the [http://global.britannica.com/topic/Roman-religion Roman religion] in Encyclopaedia Britannica</ref> |

||

===Choice of |

===Choice of December 25 date=== |

||

In the 3rd century, the date of birth of Jesus was the subject of both great interest and great uncertainly. Around AD 200, [[Clement of Alexandria]] wrote: |

In the 3rd century, the date of birth of Jesus was the subject of both great interest and great uncertainly. Around AD 200, [[Clement of Alexandria]] wrote: |

||

{{cquote|There are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord's birth, but also the day; and they say that it took place in the 28th year of Augustus, and in the 25th day of [the Egyptian month] Pachon [May 20] … And treating of His Passion, with very great accuracy, some say that it took place in the 16th year of Tiberius, on the 25th of Phamenoth [March 21]; and others on the 25th of Pharmuthi [April 21] and others say that on the 19th of Pharmuthi [April 15] the Savior suffered. Further, others say that He was born on the 24th or 25th of Pharmuthi [April 20 or 21].<ref>McGowan, Andrew, [http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/how-december-25-became-christmas/ How December 25 Became Christmas], ''Bible History Daily'', 12/02/2016.</ref>}} |

{{cquote|There are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord's birth, but also the day; and they say that it took place in the 28th year of Augustus, and in the 25th day of [the Egyptian month] Pachon [May 20] … And treating of His Passion, with very great accuracy, some say that it took place in the 16th year of Tiberius, on the 25th of Phamenoth [March 21]; and others on the 25th of Pharmuthi [April 21] and others say that on the 19th of Pharmuthi [April 15] the Savior suffered. Further, others say that He was born on the 24th or 25th of Pharmuthi [April 20 or 21].<ref>McGowan, Andrew, [http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/how-december-25-became-christmas/ How December 25 Became Christmas], ''Bible History Daily'', 12/02/2016.</ref>}} |

||

In other writing of this time, 20 May, 18 or 19 April |

In other writing of this time, 20 May, 18 or 19 April March 25, 2 January November 17, and November 20 are all suggested.<ref name="CathChrit"/><ref name=Coffman>{{cite web|url=http://www.christianitytoday.com/ch/news/2000/dec08.html |title=Elesha Coffman, "Why December 25?" |publisher=Christianitytoday.com |date=August 8, 2008 |accessdate=December 25, 2013}}</ref> Various factors contributed to the selection of December 25 as a date of celebration: it was the date of the winter solstice on the Roman calendar; it was about nine months after March 25, the date of the vernal equinox and a date linked to the conception of Jesus; and it was the date of a Roman pagan festival in honor of the Sun god [[Sol Invictus]]. |

||

====Solstice date==== |

====Solstice date==== |

||

December 25 was the date of the [[winter solstice]] on the Roman calendar.<ref name="Bradt">Bradt, Hale, ''Astronomy Methods'', (2004), p. 69.<br/>Roll p. 87.</ref><ref name="SolsticeDate">"[http://www.cs.utk.edu/~mclennan/BA/SF/WinSol.html Bruma]", ''Seasonal Festivals of the Greeks and Romans''<br/>[[Pliny the Elder]], [[Natural History (Pliny)|Natural History]], [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137&query=head%3D%231117 18:59]</ref> Jesus chose to be born on the shortest day of the year for symbolic reasons, according to an early sermon by [[Augustine]]: "Hence it is that He was born on the day which is the shortest in our earthly reckoning and from which subsequent days begin to increase in length. He, therefore, who bent low and lifted us up chose the shortest day, yet the one whence light begins to increase."<ref>Augustine, [http://www.dec25th.info/Augustine's%20Sermon%20192.html Sermon 192].</ref> |

|||

Linking Jesus to the Sun was supported by various Biblical passages. Jesus was considered to be the "Sun of righteousness" prophesied by Malachi.<ref>{{bibleverse||Malachi|4:2|ESV}}.</ref> John describes him as "the light of the world."<ref>{{bibleverse||John|8:12|ESV}}.</ref> |

Linking Jesus to the Sun was supported by various Biblical passages. Jesus was considered to be the "Sun of righteousness" prophesied by Malachi.<ref>{{bibleverse||Malachi|4:2|ESV}}.</ref> John describes him as "the light of the world."<ref>{{bibleverse||John|8:12|ESV}}.</ref> |

||

Such solar symbolism could support more than one date of birth. An anonymous work known as ''De Pascha Computus'' (243) linked the idea that creation began at the spring equinox, on |

Such solar symbolism could support more than one date of birth. An anonymous work known as ''De Pascha Computus'' (243) linked the idea that creation began at the spring equinox, on March 25, with the conception or birth (the word ''nascor'' can mean either) of Jesus on March 28, the day of the creation of the sun in the Genesis account. One translation reads: "O the splendid and divine providence of the Lord, that on that day, the very day, on which the sun was made, the 28 March, a Wednesday, Christ should be born. For this reason Malachi the prophet, speaking about him to the people, fittingly said, 'Unto you shall the sun of righteousness arise, and healing is in his wings.'"<ref name="CathChrit"/><ref name="Roll">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6MXPEMbpjoAC&pg=PA82 |first=Susan K. |last=Roll |title=Towards the Origin of Christmas |publisher=Kok Pharos Publishing |year=1995 |isbn=90-390-0531-1 |page=82, cf. note 115 |accessdate=December 25, 2013}}</ref> |

||

In the 17th century, [[Isaac Newton]] argued that the date of Christmas was selected to correspond with the solstice.<ref name="Newton"/> |

In the 17th century, [[Isaac Newton]] argued that the date of Christmas was selected to correspond with the solstice.<ref name="Newton"/> |

||

According to Steven Hijmans of the University of Alberta, "It is cosmic symbolism ... which inspired the Church leadership in Rome to elect the [[southern solstice]], December 25, as the birthday of Christ, and the [[northern solstice]] as that of John the Baptist, supplemented by the equinoxes as their respective dates of conception."<ref name="Hijmans">Hijmans, S.E., ''[http://www.scribd.com/doc/33490806/Hijmans-Sol-The-Sun-in-the-Art-and-Religions-of-Rome Sol, the sun in the art and religions of Rome],'' 2009, p. 595. ISBN 978-90-367-3931-3 {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130510231050/http://www.scribd.com/doc/33490806/Hijmans-Sol-The-Sun-in-the-Art-and-Religions-of-Rome |date= |

According to Steven Hijmans of the University of Alberta, "It is cosmic symbolism ... which inspired the Church leadership in Rome to elect the [[southern solstice]], December 25, as the birthday of Christ, and the [[northern solstice]] as that of John the Baptist, supplemented by the equinoxes as their respective dates of conception."<ref name="Hijmans">Hijmans, S.E., ''[http://www.scribd.com/doc/33490806/Hijmans-Sol-The-Sun-in-the-Art-and-Religions-of-Rome Sol, the sun in the art and religions of Rome],'' 2009, p. 595. ISBN 978-90-367-3931-3 {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130510231050/http://www.scribd.com/doc/33490806/Hijmans-Sol-The-Sun-in-the-Art-and-Religions-of-Rome |date=May 10, 2013 }}</ref> |

||

====The Calculation hypothesis==== |

====The Calculation hypothesis==== |

||

The Calculation hypothesis suggests that an earlier holiday held on |

The Calculation hypothesis suggests that an earlier holiday held on March 25 became associated with the Incarnation.<ref name=SCM>Bradshaw, Paul, ''[https://books.google.com/books/about/The_New_SCM_Dictionary_of_Liturgy_and_Wo.html?id=ZrVDmaXP6HEC&redir_esc=y The New SCM Dictionary of Liturgy of Worship]'', "Chistmas," 2002.</ref> Modern scholars refer to this feast as the Quartodecimal. Christmas was then calculated as nine months later. The Calculation hypothesis was proposed by French writer [[Louis Duchesne]] in 1889.<ref name="Roll87">Roll, pp. 88–90.<br/>Duchesne, Louis, ''Les Origines du Culte Chrétien,'' Paris, 1902, 262 ff.</ref><ref name="bib-arch.org"/> |

||

In modern times, |

In modern times, March 25 is celebrated as [[Annunciation]]. This holiday was created in the seventh century and was assigned to a date that is nine months before Christmas, in addition to being the traditional date of the equinox. It is unrelated to the Quartodecimal, which had been forgotten by this time.<ref>"Annunciation, ''New Catholic Encyclopedia'' (2003).</ref> |

||

Early Christians celebrated the life of Jesus on a date considered equivalent to 14 Nisan (Passover) on the local calendar. Because Passover was held on the 14th of the month, this feast is referred to as the Quartodecimal. All the major events of Christ's life, especially the passion, were celebrated on this date. In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul mentions Passover, presumably celebrated according to the local calendar in Corinth.<ref>{{bibleverse|1|Corinthians|5:7–8|ESV}}: "Our paschal lamb, Christ, has been sacrificed. Therefore let us celebrate the festival…"<br />Tally, pp. 2–4.</ref> Tertullian (d. 220), who lived in Latin-speaking North Africa, gives the date of celebration as |

Early Christians celebrated the life of Jesus on a date considered equivalent to 14 Nisan (Passover) on the local calendar. Because Passover was held on the 14th of the month, this feast is referred to as the Quartodecimal. All the major events of Christ's life, especially the passion, were celebrated on this date. In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul mentions Passover, presumably celebrated according to the local calendar in Corinth.<ref>{{bibleverse|1|Corinthians|5:7–8|ESV}}: "Our paschal lamb, Christ, has been sacrificed. Therefore let us celebrate the festival…"<br />Tally, pp. 2–4.</ref> Tertullian (d. 220), who lived in Latin-speaking North Africa, gives the date of celebration as March 25.<ref>Roll, p. 87.</ref> In the East, which used the [[Macedonian calendar]], the date of celebration was April 6.<ref>Roll, p. 95.</ref> The date of the passion was moved to Good Friday in 165 when [[Pope Soter]] created Easter by reassigning the Resurrection to a Sunday. According to the Calculation hypothesis, celebration of the quartodecimal continued in some areas and the feast became associated with Incarnation. While Christmas was nine months after March 25, Epiphany (January 6) was nine months after April 6. Both Christmas and Epiphany have been widely celebrated as Christ's date of birth. The Armenian Church continues to celebrate the birth of Jesus on Epiphany. |

||

The Calculation hypothesis is considered academically to be "a thoroughly viable hypothesis", though not certain.<ref>Roll (1995), p. 88</ref> It was a traditional Jewish belief that great men lived a whole number of years, without fractions, so that Jesus was considered to have been conceived on |

The Calculation hypothesis is considered academically to be "a thoroughly viable hypothesis", though not certain.<ref>Roll (1995), p. 88</ref> It was a traditional Jewish belief that great men lived a whole number of years, without fractions, so that Jesus was considered to have been conceived on March 25, as he died on March 25, which was calculated to have coincided with 14 Nisan.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LR0Nyt3bi_MC&pg=PA99|title=Historical Dictionary of Catholicism}}</ref> |

||

A passage in ''Commentary on the Prophet Daniel'' (204) by [[Hippolytus of Rome]] identifies |

A passage in ''Commentary on the Prophet Daniel'' (204) by [[Hippolytus of Rome]] identifies December 25 as the date of the nativity. This passage is generally considered a late interpellation. The manuscript includes another passage, one that is more likely to be authentic, that gives the passion as March 25.<ref>[http://www.chronicon.net/chroniconfiles/Hippolytus%20and%20December%2025th.pdf Hippolytus and December 25th as the date of Jesus' birth] Roll (1995), p. 87</ref> |

||

In 221, [[Sextus Julius Africanus]] (c. 160 – c. 240) gave |

In 221, [[Sextus Julius Africanus]] (c. 160 – c. 240) gave March 25 as the day of creation and of the conception of Jesus in his universal history.<ref>{{cite book |first=Joseph F. |last=Kelly |title=The Origins of Christmas |publisher=Liturgical Press |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-81462984-0 |page= 60}}</ref> This conclusion was argued based on March 25 as the date of the spring equinox. As this implies a birth in December, it is sometimes claimed to be the earliest identification of December 25 as the nativity.<ref>"[https://global.britannica.com/topic/Christmas Christmas]," ''Encyclopædia Britannica.''</ref> However, Africanus was not such an influential writer that it is likely he determined the date of Christmas. He wrote in Greek, and Christmas seems to have originated in a Latin-speaking area. |

||

The tractate ''De solstitia et aequinoctia conceptionis et nativitatis Domini nostri Iesu Christi et Iohannis Baptistae,'' falsely attributed to [[John Chrysostom]], also argued that Jesus was conceived and crucified on the same day of the year and calculated this as |

The tractate ''De solstitia et aequinoctia conceptionis et nativitatis Domini nostri Iesu Christi et Iohannis Baptistae,'' falsely attributed to [[John Chrysostom]], also argued that Jesus was conceived and crucified on the same day of the year and calculated this as March 25.<ref name=ODCC/><ref name=Senn>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_WHCk9tyaNoC&pg=PA114|title=Introduction to Christian Liturgy}}</ref> This anonymous tract also states: "But Our Lord, too, is born in the month of December ... the eight before the calends of January [25 December] ..., But they call it the 'Birthday of the Unconquered'. Who indeed is so unconquered as Our Lord...? Or, if they say that it is the birthday of the Sun, He is the Sun of Justice."<ref name="CathChrit"/> |

||

====The History of Religions hypothesis==== |

====The History of Religions hypothesis==== |

||

The rival "History of Religions" hypothesis suggests that the Church selected |

The rival "History of Religions" hypothesis suggests that the Church selected December 25 date to appropriate festivities held by the Romans in honor of the Sun god Sol Invictus.<ref name="SCM" /> This feast was established by Aurelian in 274. |

||

An explicit expression of this theory appears in an annotation of uncertain date added to a manuscript of a work by 12th-century Syrian bishop [[Jacob Bar-Salibi]]. The scribe who added it wrote: "It was a custom of the Pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnised on that day." <ref>(cited in ''Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries'', [[Ramsay MacMullen]]. Yale:1997, p. 155)</ref> |

An explicit expression of this theory appears in an annotation of uncertain date added to a manuscript of a work by 12th-century Syrian bishop [[Jacob Bar-Salibi]]. The scribe who added it wrote: "It was a custom of the Pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnised on that day." <ref>(cited in ''Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries'', [[Ramsay MacMullen]]. Yale:1997, p. 155)</ref> |

||

In 1743, German Protestant Paul Ernst Jablonski argued Christmas was placed on |

In 1743, German Protestant Paul Ernst Jablonski argued Christmas was placed on December 25 to correspond with the Roman solar holiday ''[[Dies Natalis Solis Invicti]]'' and was therefore a "paganization" that debased the true church.<ref name="SolInvictus"/> It has been argued that, on the contrary, the Emperor [[Aurelian]], who in 274 instituted the holiday of the ''Dies Natalis Solis Invicti'', did so partly as an attempt to give a pagan significance to a date already important for Christians in Rome.<ref name="Touchstone"/> |

||

Hermann Usener<ref>[[Hermann Usener]], ''Das Weihnachtsfest'' (Part 1 of ''Religionsgeschichtliche Untersuchungen'', Second edition 1911; Verlag von Max Cohen & Sohn, Bonn. (Note that the first edition, 1889, doesn't have the discussion of Natalis Solis Invicti); also ''Sol Invictus'' (1905).)</ref> and others<ref name="Christmas"/> proposed that the Christians chose this day because it was the Roman feast celebrating the birthday of Sol Invictus. Modern scholar S. E. Hijmans, however, states that "While they were aware that pagans called this day the 'birthday' of Sol Invictus, this did not concern them and it did not play any role in their choice of date for Christmas."<ref name="Hijmans"/> |

Hermann Usener<ref>[[Hermann Usener]], ''Das Weihnachtsfest'' (Part 1 of ''Religionsgeschichtliche Untersuchungen'', Second edition 1911; Verlag von Max Cohen & Sohn, Bonn. (Note that the first edition, 1889, doesn't have the discussion of Natalis Solis Invicti); also ''Sol Invictus'' (1905).)</ref> and others<ref name="Christmas"/> proposed that the Christians chose this day because it was the Roman feast celebrating the birthday of Sol Invictus. Modern scholar S. E. Hijmans, however, states that "While they were aware that pagans called this day the 'birthday' of Sol Invictus, this did not concern them and it did not play any role in their choice of date for Christmas."<ref name="Hijmans"/> |

||

In the judgement of the Church of England Liturgical Commission, the History of Religions hypothesis has been challenged<ref name=CofE>"Although this view is still very common, it has been seriously challenged" – Church of England Liturgical Commission, ''The Promise of His Glory: Services and Prayers for the Season from All Saints to Candlemas'' (Church House Publishing 1991 ISBN 978-0-71513738-3) quoted in [http://www.oremus.org/liturgy/etc/ktf/intro.html#xmas The Date of Christmas and Epiphany]</ref> by a view based on an old tradition, according to which the date of Christmas was fixed at nine months after {{OldStyleDate| |

In the judgement of the Church of England Liturgical Commission, the History of Religions hypothesis has been challenged<ref name=CofE>"Although this view is still very common, it has been seriously challenged" – Church of England Liturgical Commission, ''The Promise of His Glory: Services and Prayers for the Season from All Saints to Candlemas'' (Church House Publishing 1991 ISBN 978-0-71513738-3) quoted in [http://www.oremus.org/liturgy/etc/ktf/intro.html#xmas The Date of Christmas and Epiphany]</ref> by a view based on an old tradition, according to which the date of Christmas was fixed at nine months after {{OldStyleDate|April 7||March 25}}, the date of the vernal equinox, on which the [[Annunciation]] was celebrated.<ref name=ODCC>''Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article "Christmas"</ref> |

||

With regard to a December religious feast of the sun as a god (Sol), as distinct from a solstice feast of the (re)birth of the astronomical sun, one scholar has commented that, "while the winter solstice on or around December 25 was well established in the Roman imperial calendar, there is no evidence that a religious celebration of Sol on that day antedated the celebration of Christmas".<ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.scribd.com/doc/33490806/Hijmans-Sol-The-Sun-in-the-Art-and-Religions-of-Rome |first=S.E. |last=Hijmans |title=The Sun in the Art and Religions of Rome |isbn=978-90-367-3931-3 |page=588 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130510231050/http://www.scribd.com/doc/33490806/Hijmans-Sol-The-Sun-in-the-Art-and-Religions-of-Rome |archive-date= |

With regard to a December religious feast of the sun as a god (Sol), as distinct from a solstice feast of the (re)birth of the astronomical sun, one scholar has commented that, "while the winter solstice on or around December 25 was well established in the Roman imperial calendar, there is no evidence that a religious celebration of Sol on that day antedated the celebration of Christmas".<ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.scribd.com/doc/33490806/Hijmans-Sol-The-Sun-in-the-Art-and-Religions-of-Rome |first=S.E. |last=Hijmans |title=The Sun in the Art and Religions of Rome |isbn=978-90-367-3931-3 |page=588 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130510231050/http://www.scribd.com/doc/33490806/Hijmans-Sol-The-Sun-in-the-Art-and-Religions-of-Rome |archive-date=May 10, 2013 }}</ref> "Thomas Talley has shown that, although the Emperor Aurelian's dedication of a temple to the sun god in the Campus Martius (C.E. 274) probably took place on the 'Birthday of the Invincible Sun' on December 25, the cult of the sun in pagan Rome ironically did not celebrate the winter solstice nor any of the other quarter-tense days, as one might expect."<ref name="Anderson">Michael Alan Anderson, ''Symbols of Saints'' (ProQuest 2008 ISBN 978-0-54956551-2), pp. 42–46</ref> The ''Oxford Companion to Christian Thought'' remarks on the uncertainty about the order of precedence between the religious celebrations of the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun and of the birthday of Jesus, stating that the hypothesis that December 25 was chosen for celebrating the birth of Jesus on the basis of the belief that his conception occurred on March 25 "potentially establishes 25 December as a Christian festival before Aurelian's decree, which, when promulgated, might have provided for the Christian feast both opportunity and challenge".<ref>[[Adrian Hastings]], Alistair Mason, Hugh Pyper (editors), ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=ognCKztR8a4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Oxford+Companion+to+Christian+Thought&hl=en&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=opportunity&f=false The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought]'' (Oxford University Press 2000 ISBN 978-0-19860024-4), p. 114</ref> |

||

===Introduction of feast=== |

===Introduction of feast=== |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

The fact the [[Donatist]]s of North Africa celebrated Christmas suggests that the feast was established by the time that church was created in 311.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7n3IqxsT0RMC&pg=PA10 |editor-first=Thomas |editor-last=Comerford Lawler |title=Sermons for Christmas and Epiphany (of Saint Augustine) |publisher=Paulist Press |year=1952 |isbn=978-0-80910137-5 |page=10}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6MXPEMbpjoAC&pg=PA169 |first=Susan K. |last=Roll |title=Toward the Origin of Christmas |publisher=Peeters Publishers |year=1995 |isbn=978-90-3900531-6 |page=169}}</ref> The earliest known Christmas celebration is recorded in a [[Chronography of 354|fourth-century manuscript compiled in Rome]]. This manuscript is thought to record a celebration that occurred in 336. It was prepared privately for Filocalus, a Roman aristocrat, in 354. The reference in question states, "VIII kal. ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeæ".<ref>[http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_08_fasti.htm]</ref> This reference is in a section of the manuscript that was copied from earlier source material.<ref>[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm]</ref> The document also contains the earliest known reference to the feast of Sol Invictus.<ref>[http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_06_calendar.htm]</ref> |

The fact the [[Donatist]]s of North Africa celebrated Christmas suggests that the feast was established by the time that church was created in 311.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7n3IqxsT0RMC&pg=PA10 |editor-first=Thomas |editor-last=Comerford Lawler |title=Sermons for Christmas and Epiphany (of Saint Augustine) |publisher=Paulist Press |year=1952 |isbn=978-0-80910137-5 |page=10}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6MXPEMbpjoAC&pg=PA169 |first=Susan K. |last=Roll |title=Toward the Origin of Christmas |publisher=Peeters Publishers |year=1995 |isbn=978-90-3900531-6 |page=169}}</ref> The earliest known Christmas celebration is recorded in a [[Chronography of 354|fourth-century manuscript compiled in Rome]]. This manuscript is thought to record a celebration that occurred in 336. It was prepared privately for Filocalus, a Roman aristocrat, in 354. The reference in question states, "VIII kal. ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeæ".<ref>[http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_08_fasti.htm]</ref> This reference is in a section of the manuscript that was copied from earlier source material.<ref>[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03724b.htm]</ref> The document also contains the earliest known reference to the feast of Sol Invictus.<ref>[http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_06_calendar.htm]</ref> |

||

In [[Eastern Christianity]] the birth of Jesus was already celebrated in connection with the [[Epiphany (feast)|Epiphany]] on |

In [[Eastern Christianity]] the birth of Jesus was already celebrated in connection with the [[Epiphany (feast)|Epiphany]] on January 6.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h5VQUdZhx1gC&pg=PA65 |editor-first1=Geoffrey |editor-last1=Wainwright |editor-first2=Karen Beth |editor-last2=Westerfield Tucker |title=The Oxford History of Christian Worship |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-19-513886-3 |page=65 |accessdate=February 3, 2012}}</ref><ref name=Roy>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Traditional_Festivals_An_Multicultur.html?id=ANxZYgEACAAJ |first=Christian |last=Roy |title=Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia |publisher=ABC-CLIO |year=2005 |isbn=978-1-57607-089-5 |page=146 |accessdate=February 3, 2012}}</ref> Epiphany emphasized celebration of the [[baptism of Jesus]].<ref>Pokhilko, Hieromonk Nicholas, [http://sites.google.com/site/historyofepiphany "History of Epiphany"]</ref> December 25 celebration was imported into the East later: in Antioch by [[John Chrysostom]] towards the end of the fourth century,<ref name=Roy/> probably in 388, and in Alexandria only in the following century.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eUkNAQAAMAAJ |editor-first1=James |editor-last1=Hastings |editor-first2=John A. |editor-last2=Selbie |title=Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics |publisher=Kessinger Publishing Company |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-7661-3676-2 |page= Part 6, pp. 603–604 |accessdate=February 3, 2012}}</ref> Even in the West, January 6 celebration of the nativity of Jesus seems to have continued until after 380.<ref>Hastings and Selbie, p. 605</ref> |

||

In the East, early Christians celebrated the birth of Christ as part of [[Epiphany (Christian)|Epiphany]] ( |

In the East, early Christians celebrated the birth of Christ as part of [[Epiphany (Christian)|Epiphany]] (January 6), although Christmas was promoted in the Christian East as part of the revival of [[Nicene Christianity]] following the death of the pro-[[Arianism|Arian]] Emperor [[Valens]] at the [[Battle of Adrianople]] in 378. The feast was introduced at [[Constantinople]] in 379, and at [[Antioch]] in about 380. The feast disappeared after [[Gregory of Nazianzus]] resigned as [[bishop]] in 381, although it was reintroduced by [[John Chrysostom]] in about 400.<ref name="CathChrit"/> |

||

===Relation to concurrent celebrations=== |

===Relation to concurrent celebrations=== |

||

Many popular customs associated with Christmas developed independently of the commemoration of Jesus' birth, with certain elements having origins in pre-Christian festivals that were celebrated around the winter solstice by pagan populations who were later [[Christianization|converted to Christianity]]. These elements, including the [[Yule log]] from Yule and gift giving from [[Saturnalia]],<ref name="OriginMyth">{{cite web|url=http://www.bsu.edu/web/01bkswartz/xmaspub.html |title=The Origin of the American Christmas Myth and Customs |accessdate= |

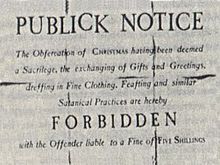

Many popular customs associated with Christmas developed independently of the commemoration of Jesus' birth, with certain elements having origins in pre-Christian festivals that were celebrated around the winter solstice by pagan populations who were later [[Christianization|converted to Christianity]]. These elements, including the [[Yule log]] from Yule and gift giving from [[Saturnalia]],<ref name="OriginMyth">{{cite web|url=http://www.bsu.edu/web/01bkswartz/xmaspub.html |title=The Origin of the American Christmas Myth and Customs |accessdate=April 30, 2011 |deadurl=bot: unknown |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110430004539/http://www.bsu.edu/web/01bkswartz/xmaspub.html |archivedate=April 30, 2011 |df=mdy }} – Ball State University. Swartz Jr., BK. Archived version. Retrieved October 19, 2011.</ref> became [[syncretism|syncretized]] into Christmas over the centuries. The prevailing atmosphere of Christmas has also continually evolved since the holiday's inception, ranging from a sometimes raucous, drunken, [[carnival]]-like state in the [[Middle Ages]],<ref name="Murray">Murray, Alexander, [http://www.historytoday.com/alexander-murray/medieval-christmas "Medieval Christmas"], ''History Today'', December 1986, '''36''' (12), pp. 31 – 39.</ref> to a tamer family-oriented and children-centered theme introduced in a 19th-century transformation.<ref name=standiford>{{cite book |first=Les |last=Standiford |title=The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits |publisher=Crown |year=2008 |isbn= 978-0-307-40578-4}}</ref><ref name=AFP>{{cite news |

||

|title=Dickens' classic 'Christmas Carol' still sings to us |

|title=Dickens' classic 'Christmas Carol' still sings to us |

||

|url=http://www.usatoday.com/life/books/news/2008-12-17-dickens-main_N.htm |

|url=http://www.usatoday.com/life/books/news/2008-12-17-dickens-main_N.htm |

||

|work=[[USA Today]] |

|work=[[USA Today]] |

||

|accessdate= |

|accessdate= April 30, 2010 |

||

|first=Bob |

|first=Bob |

||

|last=Minzesheimer |

|last=Minzesheimer |

||

|date= |

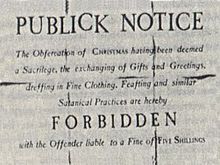

|date=December 22, 2008}}</ref> Additionally, the celebration of Christmas was banned on more than one occasion within certain [[Protestantism|Protestant]] groups, such as the [[Puritans]], due to concerns that it was too pagan or unbiblical.<ref name="Durston">Durston, Chris, [http://www.historytoday.com/dt_main_allatonce.asp?gid=12890&aid=&tgid=&amid=12890&g12890=x&g9130=x&g30026=x&g20991=x&g21010=x&g19965=x&g19963=x "Lords of Misrule: The Puritan War on Christmas 1642–60"] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070310013925/http://www.historytoday.com/dt_main_allatonce.asp?gid=12890&aid=&tgid=&amid=12890&g12890=x&g9130=x&g30026=x&g20991=x&g21010=x&g19965=x&g19963=x |date=March 10, 2007 }}, ''History Today'', December 1985, '''35''' (12) pp. 7 – 14. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070310013925/http://www.historytoday.com/dt_main_allatonce.asp?gid=12890&aid=&tgid=&amid=12890&g12890=x&g9130=x&g30026=x&g20991=x&g21010=x&g19965=x&g19963=x |date=March 10, 2007 }}</ref><ref name="Barnett"/> [[Jehovah's Witnesses]] also reject the celebration of Christmas. |

||

[[File:ChristAsSol.jpg|thumb|right|Mosaic of Jesus as ''Christus Sol'' (Christ the Sun) in Mausoleum M in the pre-fourth-century necropolis under [[St Peter's Basilica]] in Rome.<ref>Kelly, Joseph F., ''The Origins of Christmas'', Liturgical Press, 2004, p. 67-69.</ref>]] |

[[File:ChristAsSol.jpg|thumb|right|Mosaic of Jesus as ''Christus Sol'' (Christ the Sun) in Mausoleum M in the pre-fourth-century necropolis under [[St Peter's Basilica]] in Rome.<ref>Kelly, Joseph F., ''The Origins of Christmas'', Liturgical Press, 2004, p. 67-69.</ref>]] |

||

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

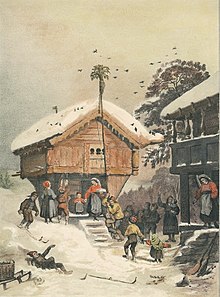

The pre-Christian [[Germanic peoples]]—including the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse—celebrated a winter festival called [[Yule]], held in the late December to early January period, yielding modern English ''yule'', today used as a synonym for ''Christmas''.<ref name="SIMEK379">Simek (2007:379).</ref> In Germanic language-speaking areas, numerous elements of modern Christmas folk custom and iconography stem from Yule, including the [[Yule log]], [[Yule boar]], and the [[Yule goat]].<ref name="SIMEK379"/> Often leading a ghostly procession through the sky (the [[Wild Hunt]]), the long-bearded god [[Odin]] is referred to as "the Yule one" and "Yule father" in Old Norse texts, whereas the rest of the gods are referred to as "Yule beings".<ref name="SIMEK-2010">Simek (2010:180, 379–380).</ref> |

The pre-Christian [[Germanic peoples]]—including the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse—celebrated a winter festival called [[Yule]], held in the late December to early January period, yielding modern English ''yule'', today used as a synonym for ''Christmas''.<ref name="SIMEK379">Simek (2007:379).</ref> In Germanic language-speaking areas, numerous elements of modern Christmas folk custom and iconography stem from Yule, including the [[Yule log]], [[Yule boar]], and the [[Yule goat]].<ref name="SIMEK379"/> Often leading a ghostly procession through the sky (the [[Wild Hunt]]), the long-bearded god [[Odin]] is referred to as "the Yule one" and "Yule father" in Old Norse texts, whereas the rest of the gods are referred to as "Yule beings".<ref name="SIMEK-2010">Simek (2010:180, 379–380).</ref> |

||

In eastern Europe also, old pagan traditions were incorporated into Christmas celebrations, an example being the [[Koleda]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/pages%5CK%5CO%5CKoliadaIT.htm |title=Koliada |publisher=Encyclopediaofukraine.com |accessdate= |

In eastern Europe also, old pagan traditions were incorporated into Christmas celebrations, an example being the [[Koleda]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/pages%5CK%5CO%5CKoliadaIT.htm |title=Koliada |publisher=Encyclopediaofukraine.com |accessdate=November 19, 2012}}</ref> which was incorporated into the [[Christmas carol]]. |

||

===Middle Ages=== |

===Middle Ages=== |

||

[[File:Nativity from Sherbrooke Missal cropped.jpg|thumb|left|''The Nativity'', from a 14th-century [[Missal]]; a liturgical book containing texts and music necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the year]] |

[[File:Nativity from Sherbrooke Missal cropped.jpg|thumb|left|''The Nativity'', from a 14th-century [[Missal]]; a liturgical book containing texts and music necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the year]] |

||

In the [[Early Middle Ages]], Christmas Day was overshadowed by Epiphany, which in [[western Christianity]] focused on the visit of the [[Biblical Magi|magi]]. But the medieval calendar was dominated by Christmas-related holidays. The forty days before Christmas became the "forty days of St. Martin" (which began on |

In the [[Early Middle Ages]], Christmas Day was overshadowed by Epiphany, which in [[western Christianity]] focused on the visit of the [[Biblical Magi|magi]]. But the medieval calendar was dominated by Christmas-related holidays. The forty days before Christmas became the "forty days of St. Martin" (which began on November 11, the feast of [[St. Martin of Tours]]), now known as Advent.<ref name="Murray"/> In Italy, former [[Saturnalia]]n traditions were attached to Advent.<ref name="Murray"/> Around the 12th century, these traditions transferred again to the [[Twelve Days of Christmas]] (December 25 – January 5); a time that appears in the liturgical calendars as Christmastide or Twelve Holy Days.<ref name="Murray"/> |

||

The prominence of Christmas Day increased gradually after [[Charlemagne]] was crowned Emperor on Christmas Day in 800. King [[Edmund the Martyr]] was anointed on Christmas in 855 and King [[William I of England]] was crowned on Christmas Day 1066. |

The prominence of Christmas Day increased gradually after [[Charlemagne]] was crowned Emperor on Christmas Day in 800. King [[Edmund the Martyr]] was anointed on Christmas in 855 and King [[William I of England]] was crowned on Christmas Day 1066. |

||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

By the [[High Middle Ages]], the holiday had become so prominent that chroniclers routinely noted where various [[magnate]]s celebrated Christmas. [[Richard II of England|King Richard II]] of England hosted a Christmas feast in 1377 at which twenty-eight oxen and three hundred sheep were eaten.<ref name="Murray"/> The Yule boar was a common feature of medieval Christmas feasts. [[Christmas carol|Caroling]] also became popular, and was originally a group of dancers who sang. The group was composed of a lead singer and a ring of dancers that provided the chorus. Various writers of the time condemned caroling as lewd, indicating that the unruly traditions of Saturnalia and Yule may have continued in this form.<ref name="Murray"/> "[[Lord of Misrule|Misrule]]"—drunkenness, promiscuity, gambling—was also an important aspect of the festival. In England, gifts were exchanged on [[New Year's Day]], and there was special Christmas ale.<ref name="Murray"/> |