LSD

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | LSD, LSD-25, lysergide, D-lysergic acid diethylamide, N,N-diethyl-D-lysergamide |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, Intravenous, Transdermal |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3 hours |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.031 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

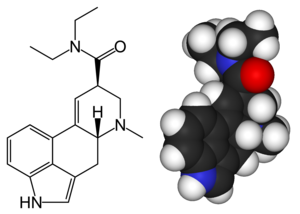

| Formula | C20H25N3O |

| Molar mass | 323.43 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 80 °C (176 °F) |

| |

Lysergic acid diethylamide, LSD, LSD-25, or acid, is a semisynthetic psychedelic drug. It is synthesized from lysergic acid derived from ergot, a grain fungus that typically grows on rye. The short form LSD comes from its early codename LSD-25, which is an abbreviation for the German "Lysergsäure-diethylamid" followed by a sequential number.[1][2]

LSD is sensitive to oxygen, ultraviolet light, and chlorine, especially in solution, though its potency may last years if it is stored away from light and moisture at low temperature. In pure form it is colorless, odorless and mildly bitter.[2] LSD is typically delivered orally, usually on a substrate such as absorbent blotter paper, a sugar cube, or gelatin. In its liquid form, it can be administered by intramuscular or intravenous injection. The threshold dosage level for an effect on humans is of the order of 20 to 30 µg (micrograms).

Introduced by Sandoz Laboratories as a drug with various psychiatric uses, LSD quickly became a therapeutic agent that appeared to show great promise. However, the extra-medical use of the drug in Western society in the middle years of the twentieth century led to a political firestorm that resulted in the banning of the substance for medical as well as recreational and spiritual uses. Despite this, it is still considered a promising drug in some intellectual circles, and organizations such as the Beckley Foundation, MAPS, Heffter Research Institute and the Albert Hofmann Foundation exist to fund, encourage and coordinate research into its medical uses.

Origins and history

LSD was first synthesized on November 16, 1938[3] by Swiss chemist Dr. Albert Hofmann at the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, as part of a large research program searching for medically useful ergot alkaloid derivatives. Its psychedelic properties were unknown until 5 years later, when Hofmann, acting on what he has called a "peculiar presentiment," returned to work on the chemical. He attributed the discovery of the compound's psychoactive effects to the accidental absorption of a tiny amount through his skin on April 16, which led to him testing a larger amount (250 µg) on himself for psychoactivity on April 19, the so-called bicycle day.[1]

Until 1966, LSD and psilocybin were provided by Sandoz Laboratories free of charge to interested scientists under the trade name "Delysid".[1] The use of these compounds by psychiatrists to gain a better subjective understanding of the schizophrenic experience was an accepted practice. Many clinical trials were conducted on the potential use of LSD in psychedelic psychotherapy, generally with very positive results.[4]

Regulation and research

Cold War intelligence services were keenly interested in the possibilities of using LSD for interrogation and mind control, and also for large-scale social engineering. The CIA conducted extensive research on LSD, the records of which were mostly destroyed. LSD was a central research area for Project MKULTRA, the code name for a CIA mind-control research program begun in the 1950s and continued until the late 1960s.[5] Tests were also conducted by the U.S. Army Biomedical Laboratory (now known as the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense) located in the Edgewood Arsenal at Aberdeen Proving Grounds. Volunteers would take LSD and then perform a battery of tests to investigate the effects of the drug on soldiers. Based on remaining publicly available records, the projects seem to have concluded that LSD was of little practical use as a mind control drug and moved on to other drugs. Both the CIA and the Army experiments became highly controversial when they became public knowledge in the 1970s, as the test subjects were not normally informed of the nature of the experiments, or even that they were subjects in experiments at all. Several subjects developed severe mental illnesses and even committed suicide after the experiments, although it is not clear whether this was due to the experiments. Most of the MKULTRA records were deliberately destroyed in 1973. The controversy contributed to President Ford's creation of the Rockefeller Commission and new regulations on informed consent.

The British government also engaged in LSD testing; in 1953 and 1954, scientists working for MI6 dosed servicemen in an effort to find a "truth drug". The test subjects were not informed that they were being given LSD, and had in fact been told that they were participating in a medical project to find a cure for the common cold. One subject, aged 19 at the time, reported seeing "walls melting, cracks appearing in people's faces … eyes would run down cheeks, Salvador Dalí-type faces … a flower would turn into a slug". After keeping the trials secret for many years, MI6 agreed in 2006 to pay the former test subjects financial compensation. Like the CIA, MI6 decided that LSD was not a practical drug for mind control purposes.[6]

LSD first became popular recreationally among a small group of mental health professionals such as psychiatrists and psychologists during the 1950s, as well as by socially prominent and politically powerful individuals such as Henry and Clare Boothe Luce to whom the early LSD researchers were connected socially.

Several mental health professionals involved in LSD research, most notably Harvard psychology professors Dr. Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, became convinced of LSD's potential as a tool for spiritual growth. In 1961, Dr. Timothy Leary received grant money from Harvard University to study the effects of LSD on test subjects. 3,500 doses were given to over 400 people. Of those tested, 90% said they would like to repeat the experience, 83% said they had "learned something or had insight," and 62% said it had changed their life for the better.

Their research became more esoteric and controversial, as Leary and Alpert alleged links between the LSD experience and the state of enlightenment sought after in many mystical traditions. They were dismissed from the traditional academic psychology community, and as such cut off from legal scientific acquisition of the drug. Drs. Leary and Alpert acquired a quantity of LSD and relocated to a private mansion, where they continued their research. The experiments lost their scientific character as the pair evolved into countercultural spiritual gurus associated with the hippie movement, encouraging people to question authority and challenge the status quo, a concept summarized in Leary's catchphrase, "Turn on, tune in, drop out".

The drug was banned in the United States in 1967, with scientific therapeutic research as well as individual research also becoming prohibitively difficult. Many other countries, under pressure from the U.S., quickly followed suit. Since 1967, underground recreational and therapeutic LSD use has continued in many countries, supported by a black market and popular demand for the drug. Legal, academic research experiments on the effects and mechanisms of LSD are also conducted on occasion, but rarely involve human subjects. Despite its proscription, the hippie counterculture continued to promote the regular use of LSD, led by figures such as Leary and psychedelic rock bands such as The Beatles, The Doors, The Grateful Dead. Acidhead has been used as a — sometimes derogatory — name for people who frequently use LSD.

According to Leigh Henderson and William Glass, two researchers associated with the NIDA who performed a 1994 review of the literature, LSD use is relatively uncommon when compared to the abuse of alcohol, cocaine, and prescription drugs. Over the previous fifteen years, long-term usage trends stayed fairly stable, with roughly 5% of the population using the drug and most users being in the 16 to 23 age range.[7] Henderson and Glass found that LSD users typically partook of the substance on an infrequent, episodic basis, then "maturing out" after two to four years. Overall, LSD appeared to have comparatively few adverse health consequences, of which "bad trips" were the most commonly reported (and, the researchers found, one of the chief reasons youths stop using the drug).[8]

Popular LSD Users

- Your mom

- Liam Hoskins

- George Harrison

- The rest of the Beatles

- Natasha Hoskins

- Liam's mom

Dosage

LSD is, by mass, one of the most potent drugs yet discovered. Dosages of LSD are measured in micrograms (µg), or millionths of a gram. By comparison, dosages of almost all other drugs, both recreational and medical, are measured in milligrams (mg), or thousandths of a gram. Hofmann determined that an active dose of mescaline, roughly 0.2 to 0.5 g, has effects comparable to 100 µg or less of LSD; put another way, LSD is between five and ten thousand times more active than mescaline.[1]

While a typical single dose of LSD may be between 100 and 500 micrograms — an amount roughly equal to one-tenth the mass of a grain of sand — threshold effects can be felt with as little as 20 micrograms.[9]

According to Stoll, the dosage level that will produce a threshold hallucinogenic effect in humans is generally considered to be 20 to 30 µg, with the drug's effects becoming markedly more evident at higher dosages.[10][9] According to Glass and Henderson's review, black-market LSD is largely unadulterated though sometimes contaminated by manufacturing by-products. Typical doses in the 1960s ranged from 200 to 1000 µg, while street samples of the 1970s contained 30 to 300 µg. By the mid-1980s, the average had reduced to about 100 to 125 µg, lowering still further in the 1990s to the 20–80 µg range. (Lower doses, Glass and Henderson found, generally produce fewer bad trips.)[8] Dosages by frequent users can be as high as 1,200 µg (1.2 mg), although such a high dosage may precipitate unpleasant physical and psychological reactions.

Estimates for the lethal dosage (LD50) of LSD range from 200 µg/kg to more than 1 mg/kg of human body mass, though most sources report that there are no known human cases of such an overdose. Other sources note one report of a suspected fatal overdose of LSD occurring in 1974 in Kentucky in which there were indications that ~1/3 of a gram (320 mg or 320,000 µg) had been injected intravenously, i.e., over 3,000 more typical oral doses of ~100 µg had been injected.[11]

LSD is not considered addictive, in that its users do not exhibit the medical community's commonly accepted definitions of addiction and physical dependence. Rapid tolerance build-up prevents regular use, and there is cross-tolerance shown between LSD, mescaline and psilocybin. This tolerance diminishes after a few days' abstention from use.

Effects

Pharmacokinetics

LSD's effects normally last from eight to twelve hours[2] -- Sandoz's prospectus for "Delysid" warned: "intermittent disturbances of affect may occasionally persist for several days."[1] Contrary to early reports and common belief, LSD effects do not last longer than significant levels of the drug in the blood. Aghajanian and Bing[12] found LSD had an elimination half-life of 175 minutes, while, more recently, Papac and Foltz[13] reported that 1 µg/kg oral LSD given to a single male volunteer had an apparent plasma half-life of 5.1 hours, with a peak plasma concentration of 1.9 ng/mL at 3 hours post-dose. Notably, Aghajanian and Bing found that blood concentrations of LSD matched the time course of volunteers' difficulties with simple arithmetic problems.

Some reports indicate that although administration of chlorpromazine (Thorazine) or similar typical antipsychotic tranquilizers will not end an LSD trip, it will either lessen the intensity or immobilize and numb the patient, a side effect of the medication.[14] While it also may not end an LSD trip, the best chemical treatment for a "bad trip" is an anxiolytic agent such as diazepam (Valium) or another benzodiazepine. Some have suggested that administration of niacin (nicotinic acid, vitamin B3) could be useful to end the LSD user's experience of a "bad trip".[15] The nicotinic acid in niacin as opposed to nicotinamide, will produce a full body heat rash, due to widening of peripheral blood vessels. The effect is somewhat akin to a poison ivy rash. Although it is not clear to what extent the effects of LSD are reduced by this intervention, the physical effect of an itchy skin rash may itself tend to distract the user from feelings of anxiety. Indeed, nicotinic acid was experienced as a stressor by all tested persons. The rash itself is temporary and disappears within a few hours. It is questionable if this method could be effective for people having serious adverse psychological reactions.

LSD affects a large number of the G protein coupled receptors, including all dopamine receptor subtypes, all adrenoreceptor subtypes as well as many others. LSD binds to most serotonin receptor subtypes except for 5-HT3 and 5-HT4. However, most of these receptors are affected at too low affinity to be activated by the brain concentration of approximate 10–20 nM.[16] Recreational doses of LSD can affect 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT5A, 5-HT5B, and 5-HT6 receptors. The hallucinogenic effects of LSD are attributed to its strong partial agonist effects at 5-HT2A receptors as specific 5-HT2A agonist drugs are hallucinogenic and largely 5-HT2A specific antagonists block the hallucinogenic activity of LSD.[16] Exactly how this produces the drug's effects is unknown, but it is thought that it works by increasing glutamate release and hence excitation in the cortex, specifically in layers IV and V.[17] In the later stages, LSD might act through DARPP-32 - related pathways that are likely the same for multiple drugs including cocaine, amphetamine, nicotine, caffeine, PCP, ethanol and morphine.[18] A particularly compelling look at the actions of LSD was performed by Barry Jacobs recording from electrodes implanted into cat Raphe nuclei.[19] Behaviorally relevant doses of LSD result in a complete blockade of action potential activity in the dorsal raphe, effectively shutting off the principal endogenous source of serotonin to the telencephalon.

Physical

Physical reactions to LSD are highly variable and may include the following: uterine contractions, hypothermia, fever, elevated levels of blood sugar, goose bumps, increase of heart rate, jaw clenching, perspiration, pupil-dilation, saliva production, mucus production, sleeplessness, paresthesia, euphoria, hyperreflexia, tremors and synesthesia. LSD users report numbness, weakness, trembling, and nausea[citation needed].

LSD was studied in the 1960s by Eric Kast as an analgetic for serious and chronic pain caused by cancer or other major trauma.[20] Even at low (sub-psychedelic) dosages, it was found to be at least as effective as traditional opiates while being much longer lasting (pain reduction lasting as long as a week after peak effects had subsided). Kast attributed this effect to a decrease in anxiety. This reported effect is being tested (though not using LSD) in an ongoing (as of 2006) study of the effects of the psychedelic tryptamine psilocybin on anxiety in terminal cancer patients.

Furthermore, LSD has been illicitly used as a treatment for cluster headaches, an uncommon but extremely painful disorder. Researcher Peter Goadsby describes the headaches as "worse than natural childbirth or even amputation without anesthetic."[21] Although the phenomenon has not been formally investigated, case reports indicate that LSD and psilocybin can reduce cluster pain and also interrupt the cluster-headache cycle, preventing future headaches from occurring. Currently existing treatments include various ergolines, among other chemicals, so LSD's efficacy may not be surprising. A dose-response study, testing the effectiveness of both LSD and psilocybin is, as of 2007, being planned at McLean Hospital. A 2006 study by McLean researchers interviewed 53 cluster-headache sufferers who treated themselves with either LSD or psilocybin, finding that a majority of the users of either drug reported beneficial effects.[22] Unlike attempts to use LSD or MDMA in psychotherapy, this research involves non-psychological effects and often sub-psychedelic dosages; therefore, it is plausible that a respected medical use of LSD will arise.[23]

Psychological

LSD's psychological effects (colloquially called a "trip") vary greatly from person to person, depending on factors such as previous experiences, state of mind and environment, as well as dose strength. They also vary from one trip to another, and even as time passes during a single trip. An LSD trip can have long term psychoemotional effects; some users cite the LSD experience as causing significant changes in their personality and life perspective. Widely different effects emerge based on what Leary called set and setting; the "set" being the general mindset of the user, and the "setting" being the physical and social environment in which the drug's effects are experienced.[citation needed]

Some psychological effects may include an experience of radiant colors, objects and surfaces appearing to ripple or "breathe," colored patterns behind the eyes, a sense of time distortion, crawling geometric patterns overlaying walls and other objects, morphing objects, loss of a sense of identity or the ego, and powerful, and sometimes brutal, psycho-physical reactions described by users as reliving their own birth.

LSD experiences can range from indescribably ecstatic to extraordinarily difficult; many difficult experiences (or "bad trips") result from a panicked feeling that he or she has been permanently severed from reality and his or her ego.[citation needed] If the user is in a hostile or otherwise unsettling environment, or is not mentally prepared for the powerful distortions in perception and thought that the drug causes, effects are more likely to be unpleasant than if he or she is in a comfortable environment and has a relaxed, balanced and open mindset.[citation needed]

Many users experience a dissolution between themselves and the "outside world".[24] This unitive quality may play a role in the spiritual and religious aspects of LSD. The drug sometimes leads to disintegration or restructuring of the user's historical personality and creates a mental state that some users report allows them to have more choice regarding the nature of their own personality.

Some experts hypothesize that drugs such as LSD may be useful in psychotherapy, especially when the patient is unable to "unblock" repressed subconscious material through other psychotherapeutic methods,[25] and also for treating alcoholism. One study concluded, "The root of the therapeutic value of the LSD experience is its potential for producing self-acceptance and self-surrender,"[26] presumably by forcing the user to face issues and problems in that individual's psyche. Many believe that, in contrast, other drugs (such as alcohol, heroin, and cocaine) are used to escape from reality. Studies in the 1950s that used LSD to treat alcoholism professed a 50% success rate,[27] five times higher than estimates near 10% for Alcoholics Anonymous.[28] Some LSD studies were criticized for methodological flaws, and different groups had inconsistent results. Mangini's 1998 paper reviews this history and concludes that the efficacy of LSD in treating alcoholism remains an open question.[29]

Many notable individuals have commented publicly on their experiences with LSD. Some of these comments date from the era when it was legally available in the US and Europe for non-medical uses, and others pertain to psychiatric treatment in the 1950s and 60s. Still others describe experiences with illegal LSD, obtained for philosophic, artistic, therapeutic, spiritual, or recreational purposes.

Sensory / perception

LSD causes expansion and altered experience of senses, emotions, memories, time, and awareness for 6 to 14 hours, depending on dosage and tolerance. Generally beginning within thirty to ninety minutes after ingestion, the user may experience anything from subtle changes in perception to overwhelming cognitive shifts. LSD does not produce hallucinations in the strict sense, but instead illusions and vivid daydream-like fantasies, in which ordinary objects and experiences can take on entirely different appearances or meanings.

Changes in auditory and visual perception are typical.[24][30] Visual effects include the illusion of movement of static surfaces ("walls breathing"), after image-like trails of moving objects, the appearance of moving colored geometric patterns (especially with closed eyes), an intensification of colors and brightness ("sparkling"), new textures on objects, blurred vision, and shape suggestibility. Users commonly report that the inanimate world appears to animate in an unexplained way; for instance, objects that are static in three dimensions can seem to be moving relative to one or more additional spatial dimensions.[31] Many of the basic visual effects resemble the phosphenes seen after applying pressure to the eye and have also been studied under the name "form constants". Auditory effects are not that pronounced and include echo-like distortions of sounds, a general intensification of the experience of music, and an increased discrimination of instruments and sounds.

Higher doses often cause intense and fundamental distortions of sensory perception such as synaesthesia, the experience of additional spatial or temporal dimensions, and temporary dissociation.

Spiritual

LSD is considered an entheogen because it can catalyze intense spiritual experiences where users feel they have come into contact with a greater spiritual or cosmic order. Some users report insights into the way the mind works, and some experience long-lasting changes in their life perspective. Some users consider LSD a religious sacrament, or a powerful tool for access to the divine. Several books have been written comparing the LSD trip to the state of enlightenment of eastern philosophy.

Such experiences under the influence of LSD have been observed and documented by researchers such as Alan Watts,Timothy Leary and Stanislav Grof. For example, Walter Pahnke conducted the Good Friday Marsh Chapel Experiment under Leary's supervision, performing a double blind experiment on the administration of psilocybin to volunteers who were students in religious graduate programs, e.g., divinity or theology.[32] That study provided evidence that hallucinogens may induce mystical religious states (at least in people with a spiritual predisposition).

Potential Risks of LSD use

Although LSD is generally considered nontoxic, it may temporarily impair the ability to make sensible judgments and understand common dangers, thus making the user susceptible to accidents and personal injury.

There is also some indication that LSD may trigger a dissociative fugue state in individuals who are taking certain classes of antidepressants such as lithium salts and tricyclics. In such a state, the user has an impulse to wander, and may not be aware of his or her actions, which can lead to physical injury.[33] SSRIs are believed to interact more benignly, with a tendency to noticeably reduce LSD's subjective effects.[34] Similar and perhaps greater reductions have also been reported with MAOIs.[33]

As Albert Hofmann reports in LSD – My Problem Child, the early pharmacological testing Sandoz performed on the compound (before he ever discovered its psychoactive properties) indicated that LSD has a pronounced effect upon the mammalian uterus. Sandoz's testing showed that LSD can stimulate uterine contractions with efficacy comparable to ergobasine, the active uterotonic component of the ergot fungus (Hofmann's work on ergot derivatives also produced a modified form of ergobasine which became a widely accepted medication used in obstetrics, under the trade name Methergine). Therefore, LSD use by pregnant women could be dangerous and is contraindicated.[1]

Initial studies in the 1960s and 70s raised concerns that LSD might produce genetic damage or developmental abnormalities in fetuses. However, these initial reports were based on in vitro studies or were poorly controlled and have not been substantiated. In studies of chromosomal changes in human users and in monkeys, the balance of evidence suggests no significant increase in chromosomal damage. For example, studies were conducted with people who had been given LSD in a clinical setting.[35] White blood cells from these people were examined for visible chromosomal abnormalities. Overall, there appeared to be no lasting changes. Several studies have been conducted using illicit LSD users and provide a less clear picture. Interpretation of these data is generally complicated by factors such as the unknown chemical composition of street LSD, concurrent use of other psychoactive drugs, and diseases such as hepatitis in the sampled populations. It seems possible that the small number of congenital abnormalities reported in users of street LSD is either coincidental or related to factors other than a toxic effect of pure LSD.[35]

Flashbacks and HPPD

There is a reported possibility of "flashbacks", a psychological phenomenon in which an individual experiences an episode of some of LSD's subjective effects long after the drug has worn off — sometimes weeks, months, or even years afterward. Flashbacks can incorporate both positive and negative aspects of LSD trips. Colloquial usage of the term flashback refers to any experience reminiscent of LSD effects, with the typical connotation that the episodes are of short duration. However, psychiatry recognizes a disorder in which LSD-like effects are persistent and cause clinically significant impairment or distress. This syndrome is called Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD), a DSM-IV diagnosis. Several scientific journal articles have described the disorder.[36]

The issues of HPPD and flashbacks are complicated and subtle, with no definitive explanations currently available. Any attempt at explanation must reflect several observations: first, over 70 percent of LSD users claim never to have "flashed back"; second, the phenomenon does appear linked with LSD use, though a causal connection has not been established; and third, a higher proportion of psychiatric patients report flashbacks than "normal" users.[37] Several studies have tried to determine how likely a "normal" user (that is, a user not suffering from known psychiatric conditions) of LSD is to experience flashbacks. The larger studies include Blumenfeld's in 1971[38] and Naditch and Fenwick's in 1977,[39] which arrived at figures of 20% and 28%, respectively. A recent review suggests that HPPD (according to the DSM-IV definition) caused by LSD appears to be rare and affects a distinctly vulnerable subpopulation of users.[40] Differences in the estimated prevalence of flashbacks may partly depend on the multiple meanings of the term and the fact that Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder can only be diagnosed in a person who admits to their health care practitioner that they have used hallucinogens.

Debate continues over the nature and causes of chronic flashbacks. Explanations in terms of LSD physically remaining in the body for months or years after consumption have been discounted by experimental evidence.[37] Some say HPPD is a manifestation of post-traumatic stress disorder, not related to the direct action of LSD on brain chemistry, and varies according to the susceptibility of the individual to the disorder. Many emotionally intense experiences can lead to flashbacks when a person is reminded acutely of the original experience. However, not all published case reports of chronic flashbacks appear to describe an anxious hyper-vigilant state reminiscent of post-traumatic stress disorder.[37]

An alternative theory regarding flashbacks postulates that it is a form of perceptual learning.[citation needed] Although unusual perceptual experiences may be just as common among people with no history of having taken the drug, people who have taken LSD may be more likely to associate these otherwise normal psychological events with the experiences they remember having had while on LSD.[citation needed] Under this theory, HPPD would be a separate, more serious, and far less common psychological condition. "Mere" flashbacks, in comparison, may be experienced by a broad segment of the population, and only attributed to LSD by those who have tried the drug.[citation needed]

Psychosis

There are some cases of LSD inducing a psychosis in people who appeared to be healthy prior to taking LSD. This issue was reviewed extensively in a 1984 publication by Rick Strassman.[41] In most cases, the psychosis-like reaction is of short duration, but in other cases it may be chronic. It is difficult to determine if LSD itself induces these reactions or if it merely triggers latent conditions that would have manifested themselves otherwise. The similarities of time course and outcomes between putatively LSD-precipitated and other psychoses suggests that the two types of syndromes are not different and that LSD may have been a nonspecific trigger. Several studies have tried to estimate the prevalence of LSD-induced prolonged psychosis arriving at numbers of around 4 in 1,000 individuals (0.8 in 1,000 volunteers and 1.8 in 1,000 psychotherapy patients in Cohen 1960;[42] 9 per 1,000 psychotherapy patients in Melleson 1971[43]). Although, this is the same percentage of people in general society who suffer from psychosis[citation needed]. This had led scientists[who?] to believe that LSD does not cause psychoses, only triggers it in cases of people with a predisposition to schizophrenia or other mental illnesses. There is no higher rate for psychoses occurring amongst LSD users to those occurring without the use of LSD[citation needed].

Chemistry

LSD is an ergoline derivative. It is commonly produced from reacting diethylamine with an activated form of lysergic acid. Activating reagents include phosphoryl chloride and peptide coupling reagents. Lysergic acid is made by alkaline hydrolysis of lysergamides like ergotamine, a substance derived from the ergot fungus on rye, or, theoretically, from ergine (lysergic acid amide, LSA), a compound that is found in morning glory (Ipomoea tricolor) and hawaiian baby woodrose (Argyreia nervosa) seeds. LSD is a chiral compound with two stereocenters at the carbon atoms C-5 and C-8, so that theoretically four different optical isomers of LSD could exist. LSD, also called (+)-D-LSD, has the absolute configuration (5R,8R). The C-5 isomers of lysergamides do not exist in nature and are not formed during the synthesis from D-lysergic acid. However, LSD and iso-LSD, the two C-8 isomers, rapidly interconvert in the presence of base. Non-psychoactive iso-LSD which has formed during the synthesis can be removed by chromatography and can be isomerized to LSD. A totally pure salt of LSD will emit small flashes of white light when shaken in the dark.[44] LSD is strongly fluorescent and will glow bluish-white under UV light.

Stability

"LSD," writes the chemist Alexander Shulgin, "is an unusually fragile molecule."[2] It is stable for indefinite amounts of time if stored, as a solid salt or dissolved in water, at low temperature and protected from air and light exposure. Two portions of its molecular structure are particularly sensitive, the carboxamide attachment at the 8-position and the double bond between the 8-position and the aromatic ring. The former is affected by high pH, and if perturbed will produce isolysergic acid diethylamide (iso-LSD), which is biologically inactive. If water or alcohol adds to the double bond (especially in the presence of light), LSD converts to "lumi-LSD", which is totally inactive in human beings, to the best of current knowledge. Furthermore, chlorine destroys LSD molecules on contact; even though chlorinated tap water typically contains only a slight amount of chlorine, because a typical LSD solution only contains a small amount of LSD, dissolving LSD in tap water is likely to completely eliminate the substance.[2]

A controlled study was undertaken to determine the stability of LSD in pooled urine samples.[45] The concentrations of LSD in urine samples were followed over time at various temperatures, in different types of storage containers, at various exposures to different wavelengths of light, and at varying pH values. These studies demonstrated no significant loss in LSD concentration at 25 °C for up to 4 weeks. After 4 weeks of incubation, a 30% loss in LSD concentration at 37 °C and up to a 40% at 45 °C were observed. Urine fortified with LSD and stored in amber glass or nontransparent polyethylene containers showed no change in concentration under any light conditions. Stability of LSD in transparent containers under light was dependent on the distance between the light source and the samples, the wavelength of light, exposure time, and the intensity of light. After prolonged exposure to heat in alkaline pH conditions, 10 to 15% of the parent LSD epimerized to iso-LSD. Under acidic conditions, less than 5% of the LSD was converted to iso-LSD. It was also demonstrated that trace amounts of metal ions in buffer or urine could catalyze the decomposition of LSD and that this process can be avoided by the addition of EDTA.

Production

Because an active dose of LSD is astonishingly minute, a large number of doses can be synthesized from a comparatively small amount of raw material. Beginning with ergotamine tartrate, for example, one can manufacture roughly one kilogram of pure, crystalline LSD from five kilograms of the ergotamine salt. Five kilograms of LSD — 25 kilograms of ergotamine tartrate — could provide 100 million doses, sufficient for supplying the entire illicit demand of the United States. Since the masses involved are so small, concealing and transporting illicit LSD is much easier than smuggling other illegal drugs like cocaine or cannabis in equal dosage quantities.[46]

Manufacturing LSD requires laboratory equipment and experience in the field of organic chemistry. It takes two or three days to produce 30 to 100 grams of pure compound. It is believed that LSD usually is not produced in large quantities, but rather in a series of small batches. This technique minimizes the loss of precursor chemicals in case a synthesis step does not work as expected.[46]

Forms of LSD

LSD is produced in crystalline form and then mixed with excipients or redissolved for production in ingestible forms. Liquid solution is either distributed as-is in small vials or, more commonly, sprayed onto or soaked into a distribution medium. Historically, LSD solutions were first sold on sugar cubes, but practical considerations forced a change to tablet form. Early pills or tabs were flattened on both ends and identified by color: "grey flat", "blue flat", and so forth. Next came "domes", which were rounded on one end, then "double domes" rounded on both ends, and finally small tablets known as "microdots". Later still, LSD began to be distributed in thin squares of gelatin ("window panes", "gel tabs") and, most commonly, as blotter paper: sheets of paper impregnated with LSD and perforated into small squares of individual dosage units. The paper is then cut into small square pieces called "tabs" or "hits" for distribution. Individual producers often print designs onto the paper serving to identify different makers, batches or strengths, and such "blotter art" often emphasizes psychedelic themes.

LSD has been sold under a wide variety of often short-lived and regionally restricted street names including Acid, Trips, Alice Dee, Blotter, Liquid A, Lucy, Microdots, Sunshine, Twenty-five, Windowpane, etc., as well as names that reflect the designs on the sheets of blotter paper.[47][48] On occasion, authorities have encountered the drug in other forms — including powder or crystal, and capsule. More than 200 types of LSD tablets have been encountered since 1969 and more than 350 paper designs have been observed since 1975. Designs range from simple five-point stars in black and white to exotic artwork in full four-color print.

Legal status

LSD is Schedule I in the United States[49]. This means it is illegal to manufacture, buy, possess, or distribute LSD without a DEA license.

The United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances (adopted in 1971) requires its parties to prohibit LSD. Hence, it is illegal in all parties to the convention, which includes the United States, Australia, and most of Europe. However, enforcement of extant laws varies from country to country.

LSD is easy to conceal and smuggle. A tiny vial can contain thousands of doses. Not much money is made from retail-level sales of LSD, so the drug is typically not associated with the violent organized criminal organizations involved in cocaine and opiate smuggling.

Canada

In Canada, LSD is a controlled substance under Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA). Every person who seeks to obtain the substance without disclosing authorization to obtain such substances 30 days prior to obtaining another prescription from a practitioner is guilty of an indictable offense and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 3 years. Possession for purpose of trafficking is guilty of an indictable offense and liable to imprisonment for 10 years.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, Lysergide and derivatives are regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance, and can only be used legally by health professionals and for university research purposes. The substance can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies the substance without prescription can be fined $10,000(HKD). The penalty for trafficking or illegally manufacturing the substance is a $5,000,000 (HKD) fine and life imprisonment. Possession of the substance for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $1,000,000 (HKD) fine and/or 7 years' imprisonment.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, LSD is classed as a class A drug. This means that, without a license, possession of the drug is punishable with 7 years imprisonment and/or an unlimited fine, and trafficking is punishable with life imprisonment and an unlimited fine (see main article on drug punishments Misuse of Drugs Act 1971).

United States: Prior to 1967

Beginning in the 1950s the Central Intelligence Agency began a research program code named Project MKULTRA. Experiments included administering LSD to CIA employees, military personnel, doctors, other government agents, prostitutes, mentally ill patients, and members of the general public in order to study their reactions, usually without the subject's knowledge. The project was revealed in the US congressional Rockefeller Commission report.

Prior to October 6th, 1966, LSD was available legally in the United States as an experimental psychiatric drug. (LSD "apostle" Al Hubbard actively promoted the drug between the 1950s and the 1970s and introduced thousands of people to it.) The US Federal Government classified it as a Schedule I drug according to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. As such, the Drug Enforcement Administration holds that LSD meets the following three criteria: it is deemed to have a high potential for abuse; it has no legitimate medical use in treatment; and there is a lack of accepted safety for its use under medical supervision. (LSD prohibition does not make an exception for religious use.) Lysergic acid and lysergic acid amide, LSD precursors, are both classified in Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act. Ergotamine tartrate, a precursor to lysergic acid, is regulated under the Chemical Diversion and Trafficking Act.

LSD has been manufactured illegally since the 1960s. Historically, LSD was distributed not for profit, but because those who made and distributed it truly believed that the psychedelic experience could do good for humanity, that it expanded the mind and could bring understanding and love. A limited number of chemists, probably fewer than a dozen, are believed to have manufactured nearly all of the illicit LSD available in the United States. The best known of these is undoubtedly Augustus Owsley Stanley III, usually known simply as Owsley. The former chemistry student set up a private LSD lab in the mid-Sixties in San Francisco and supplied the LSD consumed at the famous Merry Pranksters parties held by Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, and other major events such as the Gathering of the tribes in San Francisco in January 1967. He also had close social connections to leading San Francisco bands the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother and The Holding Company, regularly supplied them with his LSD and also worked as their live sound engineer and made many tapes of these groups in concert. Owsley's LSD activities — immortalized by Steely Dan in their song "Kid Charlemagne" — ended with his arrest at the end of 1967, but some other manufacturers probably operated continuously for 30 years or more. Announcing Owsley's first bust in 1966, The San Francisco Chronicle's headline "LSD Millionaire Arrested" inspired the rare Grateful Dead song "Alice D. Millionaire."

United States: 1970 to the present

American LSD usage declined in the 1970s and 1980s, then experienced a mild resurgence in popularity in the 1990s. Although there were many distribution channels during this decade, the U.S. DEA identified continued tours by the psychedelic rock band The Grateful Dead and the then-burgeoning rave scene as primary venues for LSD trafficking and consumption. American LSD usage fell sharply circa 2000, following a single major DEA operation.

Pickard and Apperson

The decline is attributed to the arrest of two chemists, William Leonard Pickard, a Harvard-educated organic chemist, and Clyde Apperson. According to DEA reports, black market LSD availability dropped by 95% after the two were arrested in 2000. These arrests were a result of the largest LSD manufacturing raid in DEA history.[50]

Pickard was an alleged member of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love group that produced and sold LSD in California during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is believed he had links to other "cooks" associated with this group — an original source of the drug back in the 1960s — and his arrest may have forced other operations to cease production, leading to the large decline in street availability.

The DEA claims these two individuals were responsible for the vast majority of LSD sold illegally in the United States and a significant amount of the LSD sold in Europe, and that they worked closely with organized traffickers. While this claim may have some bearing, the extent of Pickard's direct influence on the overall availability in the United States is not fully known. Some attest that "Pickard's Acid" was sold exclusively in Europe, and was not distributed through American music venues[citation needed].

In November of 2003, Pickard was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole, and Apperson was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment without parole, after being convicted in Federal Court of running a large scale LSD manufacturing operation out of several clandestine laboratories, including a former missile silo near Wamego, Kansas.

Modern Distribution

LSD manufacturers and traffickers can be categorized into two groups: A few large scale producers, such as the aforementioned Pickard and Apperson, and an equally limited number of small, clandestine chemists, consisting of independent producers who, operating on a comparatively limited scale, can be found throughout the country. As a group, independent producers are of less concern to the Drug Enforcement Administration than the larger groups, as their product reaches only local markets.

In April, 2007, Canadian psychologist Andrew Feldmar was permanently barred from entering the United States[51]after a border patrol agent used the internet to uncover a 2001 paper by Feldmar, Entheogens and Psychotherapy, which admits to therapeutic LSD use during the 1960s.[52]

See also

- ALD-52

- Bogle-Chandler case, deaths mistakenly attributed to LSD overdoses

- Drug urban legends

- Entheogen

- List of notable psychedelic self-experimenters

- Project MKULTRA, Central Intelligence Agency mind-control research program that began in the 1950s.

- Psychedelics in popular culture

- Psychedelic psychotherapy

- United States v. Stanley, US Supreme Court case

- Related chemical compounds: ergolines, LSA, psilocybin, DMT, serotonin

References

- ^ a b c d e f Hofmann, Albert. LSD—My Problem Child (McGraw-Hill, 1980). ISBN 0-07-029325-2. Available online here or here; accessed 2007-02-01.

- ^ a b c d e Shulgin, Alex and Ann Shulgin. "LSD", in TiHKAL (Berkeley: Transform Press, 1997). ISBN 0-963-00969-9.

- ^ Dr. Albert Hofmann; translated from the original German (LSD Ganz Persönlich) by J. Ott. MAPS-Volume 6 Number 3 Summer 1996

- ^ PSYCHEDELIC LSD RESEARCH By A. Kurland, W. Pahnke, S. Unger, C Savage and S. Grof

- ^ ACHRE Report, chapter 3: "Supreme Court Dissents Invoke the Nuremberg Code: CIA and DOD Human Subjects Research Scandals".

- ^ Rob Evans, "MI6 pays out over secret LSD mind control tests". The Guardian 24 February 2006.

- ^ Goldsmith, Neal M. (1995). "A Review of "LSD : Still With Us After All These Years"". Newsletter of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. 6 (1). Retrieved 2006-01-31.

- ^ a b Henderson, Leigh A.; Glass, William J. (1994). LSD: Still with Us after All These Years. ISBN 978-0787943790.

{{cite book}}: Text "Jossey-Bass Inc., San Francisco" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Greiner T, Burch NR, Edelberg R (1958). "Psychopathology and psychophysiology of minimal LSD-25 dosage; a preliminary dosage-response spectrum". AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 79 (2): 208–10. PMID 13497365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stoll, W.A. (1947). Ein neues, in sehr kleinen Mengen wirsames Phantastikum. Schweiz. Arch. Neur. 60,483.

- ^ "LSD Vault: Dosage". Erowid. 2006-07-06. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Aghajanian, George K. and Bing, Oscar H. L. (1964). "Persistence of lysergic acid diethylamide in the plasma of human subjects" (PDF). Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 5: 611–4. PMID 14209776.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Papac DI, Foltz RL (1990). "Measurement of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in human plasma by gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry". J Anal Toxicol. 14 (3): 189–90. PMID 2374410.

- ^ Gilberti, F. and Gregoretti, L. L. (1955). "Prime esperienze di antaonismo psicofarmacologico" (PDF). Sistema Nervoso. 4: 301–309.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Agnew N, and Hoffer A. L. (1955). "Nicotinic acid modified lysergic acid diethylamide psychosis". J. Ment. Sci. 101: 12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b Nichols, David E. (2004). "Hallucinogens". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101 (2): 131–81. PMID 14761703.

- ^ BilZ0r. "The Neuropharmacology of Hallucinogens: a technical overview". Erowid, v3.1 (August 2005).

- ^

Svenningsson P. , Nairn A. C., Greengard P. (2005). "DARPP-32 Mediates the Actions of Multiple Drugs of Abuse". AAPS Journal. 07 (02): E353–E360. doi:10.1208/aapsj070235.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Jacobs B. L., Heym J., Rasmussen K. (1983). "Raphe neurons: firing rate correlates with size of drug response". European Journal of Pharmacology. 90 (2–3): 275–8. PMID 6873185.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kast, Eric (1967). "Attenuation of anticipation: a therapeutic use of lysergic acid diethylamide" (PDF). Psychiat. Quart. 41 (4): 646–57. PMID 4169685.

- ^ Dr. Goadsby is quoted in "Research into psilocybin and LSD as cluster headache treatment", and he makes an equivalent statement in an Health Report interview on Australian Radio National (9 August 1999). Pages accessed 2007-01-31.

- ^ Sewell, R. A. (2006-06-27). "Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD". Neurology. 66 (12): 1920–2. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Summarized from "Research into psilocybin and LSD as cluster headache treatment" and the Clusterbusters website. Pages accessed 2007-01-31.

- ^ a b Linton, Harriet B. and Langs, Robert J. "Subjective Reactions to Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD-25)". Arch. Gen. Psychiat. Vol. 6 (1962): 352–68.

- ^ Cohen, S. (1959). The therapeutic potential of LSD-25. A Pharmacologic Approach to the Study of the Mind, p251–258.

- ^ Chwelos N, Blewett D.B., Smith C.M., Hoffer A. (1959). "Use of d-lysergic acid diethylamide in the treatment of alcoholism". Quart. J. Stud. Alcohol. 20: 577–90. PMID 13810249.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maclean, J.R.; Macdonald, D.C.; Ogden, F.; Wilby, E., "LSD-25 and mescaline as therapeutic adjuvants." In: Abramson, H., Ed., The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism, Bobbs-Merrill: New York, 1967, pp. 407–426; Ditman, K.S.; Bailey, J.J., "Evaluating LSD as a psychotherapeutic agent," pp.74–80; Hoffer, A., "A program for the treatment of alcoholism: LSD, malvaria, and nicotinic acid," pp. 353–402.

- ^ Minogue, S. J. "Alcoholics Anonymous." The Medical Journal of Australia May 8 (1948):586–587.

- ^ Mangini M (1998). "Treatment of alcoholism using psychedelic drugs: a review of the program of research". J Psychoactive Drugs. 30 (4): 381–418. PMID 9924844.

- ^ Katz MM, Waskow IE, Olsson J (1968). "Characterizing the psychological state produced by LSD". J Abnorm Psychol. 73 (1): 1–14. PMID 5639999.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ See, e.g., Gerald Oster's article "Moiré patterns and visual hallucinations". Psychedelic Rev. No. 7 (1966): 33–40.

- ^ Video of the experiment can be viewed here.

- ^ a b "LSD and Antidepressants" (2003) via Erowid.

- ^ Kit Bonson, "The Interactions between Hallucinogens and Antidepressants" (2006).

- ^ a b Dishotsky NI, Loughman WD, Mogar RE, Lipscomb WR (1971). "LSD and genetic damage" (PDF). Science. 172 (982): 431–40. PMID.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ See, for example, Abraham HD, Aldridge AM (1993). "Adverse consequences of lysergic acid diethylamide". Addiction. 88 (10): 1327–34. PMID 8251869.

- ^ a b c David Abrahart (1998). "A Critical Review of Theories and Research Concerning Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) and Mental Health". Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ^ Blumenfield M (1971). "Flashback phenomena in basic trainees who enter the US Air Force". Military Medicine. 136 (1): 39–41. PMID 5005369.

- ^ Naditch MP, Fenwick S (1977). "LSD flashbacks and ego functioning". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 86 (4): 352–9. PMID 757972.

- ^ Halpern JH, Pope HG Jr (2003). "Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years?". Drug Alcohol Depend. 69 (2): 109–19. PMID 12609692.; Halpern JH (2003). "Hallucinogens: an update". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 5 (5): 347–54. PMID 13678554. [1]

- ^ Strassman RJ (1984). "Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature". J Nerv Ment Dis. 172 (10): 577–95. PMID 6384428.

- ^ Cohen, Sidney (1960). "Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: Side Effects and Complications" (PDF). Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 130 (1): 30–40. PMID 13811003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Malleson, Nicholas (1971). "Acute Adverse Reactions to LSD in Clinical and Experimental Use in the United Kingdom" (PDF). Brit. J. Psychiat. 118 (543): 229–30. PMID 4995932.

- ^ http://www.erowid.org/library/books_online/tihkal/tihkal26.shtml

- ^ Li Z., McNally A. J., Wang H., Salamone S. J. (1998). "Stability study of LSD under various storage conditions". J Anal Toxicol. 22 (6): 520–5. PMID 9788528.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "LSD in the US – Manufacture", DEA Publications.

- ^ Honig, David. Frequently Asked Questions via Erowid.

- ^ "Street Terms: Drugs and the Drug Trade". Office of National Drug Control Policy. 2005-04-05. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ From [2]: LSD is a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act.

- ^ Seper, Jerry. "Man sentenced to life in prison as dealer of LSD". The Washington Times 27 November 2003.

- ^ O'Brien, Luke. Canadian Psychologist Who Used LSD Forty Years Ago Permanently Barred from Entering U.S.

- ^ Feldmar, Andrew Entheogens and Psychotherapy

Further reading

- Stevens, Jay. Storming Heaven: LSD And The American Dream ([3])

- Aldous FAB, Barrass BC, Brewster K, et al. "Structure-Activity Relationships in Psychotomimetic Phenylalkylamines," Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 17, 1100–1111 (1974)

- Grof, Stanislave. LSD Psychotherapy. (April 10, 2001)

- Lee, Martin A. and Bruce Shlain. Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond [4]

External links

- Belfast Telegraph Dr. Albert Hofmann - The father of LSD

- Salon.com: Dr. Hofmann's problem child turns 58, April 16, 2001

- Spontaneous pattern formation in large scale brain activity: what visual migraines and hallucinations tell us about the brain, lecture by Jack Cowan (via the Internet Archive)

- Hofmann's Potion: The Early Years of LSD by the National Film Board of Canada

- Hofmann's Potion: The Early Years of LSD on YouTube

- Erowid -> LSD Information

- A Critical Review of Theories and Research Concerning LSD and Mental Health

- The Neurochemistry of Psychedelic Experience, Science & Consciousness Review

- Current LSD Research – MAPS

- International 3 day conference on LSD in Basel

- The Lycaeum Archive -> LSD

- FRANK - LSD

- Detailed subjective personal experiences (from Drugs-Forum)

- A visual illusion similar to the effects of LSD

- Artist Frank Murdoch in LSD experiment in the late 1950's