Sega

| |

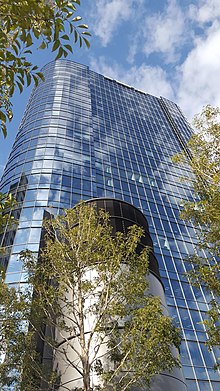

Sega's headquarters in Tokyo, Japan | |

Native name | 株式会社セガ |

|---|---|

Romanized name | Kabushiki gaisha Sega |

| Formerly |

|

| Company type | Subsidiary |

| Industry | Video games |

| Predecessor | Service Games of Japan |

| Founded | June 3, 1960 |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | Shinagawa, Tokyo , Japan |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Owner | Sega Sammy Holdings |

Number of employees | 3,238 (2020) |

| Parent | Sega Group Corporation |

| Divisions | Sega development studios |

| Subsidiaries | |

| Website | sega |

| Footnotes / references "Sega Sammy Holdings Fiscal Year 2020 Full Results Appendix" (PDF). Sega Sammy Holdings. May 13, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020. "Notice of Changes of Directors and Executive Officers at SEGA SAMMY HOLDINGS INC. and its Major Subsidiaries" (PDF). Sega Sammy Holdings. February 28, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020. | |

Sega Corporation[a] is a Japanese multinational video game developer and publisher headquartered in Shinagawa, Tokyo. Its international branches, Sega of America and Sega Europe, are respectively headquartered in Irvine, California, and London. Sega's arcade division existed as Sega Interactive Co., Ltd. from 2015 to 2020 before it merged with Sega Games to create Sega Corporation with Sega Games as the surviving entity. Sega is a subsidiary of Sega Group Corporation, which is, in turn, a part of Sega Sammy Holdings. From 1983 until 2002, Sega also developed video game consoles.

Sega was founded by American businessmen Martin Bromley and Richard Stewart as Nihon Goraku Bussan[b] on June 3, 1960; shortly after, the company acquired the assets of its predecessor, Service Games of Japan. Five years later, the company became known as Sega Enterprises, Ltd., after acquiring Rosen Enterprises, an importer of coin-operated games. Sega developed its first coin-operated game, Periscope, in the late 1960s. Sega was sold to Gulf and Western Industries in 1969. Following a downturn in the arcade business in the early 1980s, Sega began to develop video game consoles, starting with the SG-1000 and Master System but struggled against competitors such as the Nintendo Entertainment System. In 1984, Sega executives David Rosen and Hayao Nakayama led a management buyout of the company with backing from CSK Corporation.

Sega released its next console, the Sega Genesis (known as the Mega Drive outside North America), in 1988. The Genesis struggled against the competition in Japan, but found success overseas after the release of Sonic the Hedgehog in 1991 and briefly outsold its main competitor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, in the U.S. Later in the decade, Sega suffered several commercial failures such as the 32X, Saturn, and Dreamcast consoles. In 2002, Sega stopped manufacturing consoles to become a third-party developer and publisher and was acquired by Sammy Corporation in 2004. In the years since the acquisition, Sega has been more profitable. Sega Holdings Co. Ltd. was established in 2015, Sega Corporation, being renamed Sega Games Co., Ltd. and its arcade, entertainment, and toy divisions separated into other companies. Sega Games and Sega Interactive were merged in 2020 and renamed Sega Corporation.

Sega has produced several multi-million-selling game franchises, including Sonic the Hedgehog, Total War, and Yakuza, and is the world's most prolific arcade game producer. It also operates amusement arcades and produces other entertainment products, including Sega Toys. Sega is recognized for its time supporting its own video game consoles, its creativity, and its innovations. In more recent years, it has been criticized for its business decisions and the quality of its creative output.

History

Origins and arcade success (1940–1982)

In 1940, American businessmen Martin Bromley, Irving Bromberg, and James Humpert formed Standard Games in Honolulu, Hawaii. Their aim was to provide coin-operated amusement machines, including slot machines, to military bases as the increase in personnel with the onset of World War II would create demand for entertainment. After the war, the founders sold Standard Games in 1945, and in 1946 established Service Games, named for the military focus.[1] After the United States government outlawed slot machines in its territories in 1952, Bromley sent employees Richard Stewart and Ray LeMaire to Tokyo to establish Service Games of Japan to provide coin-operated slot machines to U.S. bases in Japan.[2][3][4] A year later, all five men established Service Games Panama to control the entities of Service Games worldwide. The company expanded over the next seven years to include distribution in South Korea, the Philippines, and South Vietnam.[5] The name Sega, an abbreviation of Service Games,[6] was first used in 1954 on a slot machine, the Diamond Star.[5]

Due to notoriety arising from investigations into criminal business practices, Service Games of Japan was dissolved on May 31, 1960.[5] On June 3,[7] Bromley established two companies to take over its business activities, Nihon Goraku Bussan and Nihon Kikai Seizō.[c] The two new companies purchased all of Service Games of Japan's assets. Kikai Seizō, doing business as Sega, Inc., focused on manufacturing slot machines. Goraku Bussan, doing business under Stewart as Utamatic, Inc., served as a distributor and operator of coin-operated machines, particularly jukeboxes.[5][8][9] The companies merged in 1964, retaining the Nihon Goraku Bussan name.[5]

During the same time frame, David Rosen, an American officer in the United States Air Force stationed in Japan, launched a photo booth business in Tokyo in 1954.[2] This company became Rosen Enterprises, and in 1957 began importing coin-operated games into Japan. In 1965, Nihon Goraku Bussan acquired Rosen Enterprises to form Sega Enterprises, Ltd.[d] Rosen was installed as the CEO and managing director, while Stewart was named president and LeMaire was the director of planning. Shortly afterward, Sega stopped leasing to military bases and moved its focus from slot machines to coin-operated amusement machines.[10] Its imports included Rock-Ola jukeboxes, pinball games by Williams, and gun games by Midway Manufacturing.[11]

Because Sega imported second-hand machines that required frequent maintenance, it began constructing replacement guns and flippers for its imported games. According to former Sega director Akira Nagai, this led to the company developing its own games.[11] The first electromechanical game Sega manufactured was the submarine simulator Periscope, released worldwide in the late 1960s. It featured light and sound effects considered innovative, and was successful in Japan. It was exported to malls and department stores in Europe and the United States, and helped standardize the 25-cent-per-play cost for arcade games in the U.S. Sega was surprised by the success, and for the next two years, the company produced and exported between eight and ten games per year.[12] Despite this, rampant piracy in the industry would lead to Sega stepping away from exporting its games around 1970.[13]

In 1969, Sega was sold to the American conglomerate Gulf and Western Industries, although Rosen remained CEO. In 1974, Gulf and Western made Sega Enterprises, Ltd., a subsidiary of an American company renamed Sega Enterprises, Inc. Sega released Pong-Tron, its first video-based game, in 1973.[13] Despite late competition from Taito's hit arcade game Space Invaders in 1978,[11] Sega prospered from the arcade game boom of the late 1970s, with revenues climbing to over US$100 million by 1979. During this period, Sega acquired Gremlin Industries, which manufactured microprocessor-based arcade games,[14] and Esco Boueki, a coin-op distributor founded and owned by Hayao Nakayama. Nakayama was placed in a management role of Sega's Japanese operations.[15] In the early 1980s, Sega was one of the top five arcade game manufacturers active in the United States, as company revenues rose to $214 million.[16] 1979 saw the release of Head On, which introduced the "eat the dots" gameplay Namco later used in Pac-Man.[17] In 1981, Sega licensed and released Frogger, its most successful game until then.[18] In 1982, Sega introduced the first game with isometric graphics, Zaxxon.[19]

Entry into the game console market (1982–1989)

Following a downturn in the arcade business starting in 1982, Gulf and Western sold its North American arcade game manufacturing organization and the licensing rights for its arcade games to Bally Manufacturing in September 1983.[20][21][22] Gulf and Western retained Sega's North American R&D operation and its Japanese subsidiary, Sega Enterprises, Ltd. With its arcade business in decline, Sega Enterprises, Ltd. president Nakayama advocated for the company to use its hardware expertise to move into the home consumer market in Japan.[23] This led to Sega's development of a computer, the SC-3000. Learning that Nintendo was developing a games-only console, the Famicom, Sega developed its first home video game system, the SG-1000, alongside the SC-3000.[24] Rebranded versions of the SG-1000 were released in several other markets worldwide.[24][25][26][27] The SG-1000 sold 160,000 units in 1983, which far exceeded Sega's projection of 50,000 in the first year,[24] but was outpaced by the Famicom. This was in part because Nintendo expanded its game library by courting third-party developers, whereas Sega was hesitant to collaborate with companies with which it was competing in the arcades.[24]

In November 1983, Rosen announced his intention to step down as president of Sega Enterprises, Inc. on January 1, 1984. Jeffrey Rochlis was announced as the new president and COO of Sega.[28] Shortly after the launch of the SG-1000, and the death of company founder Charles Bluhdorn, Gulf and Western began to sell off its secondary businesses.[29] Nakayama and Rosen arranged a management buyout of the Japanese subsidiary in 1984 with financial backing from CSK Corporation, a prominent Japanese software company.[30] Sega's Japanese assets were purchased for $38 million by a group of investors led by Rosen and Nakayama. Isao Okawa, head of CSK, became chairman,[15] while Nakayama was installed as CEO of Sega Enterprises, Ltd.[31]

In 1985, Sega began working on the Mark III,[32] a redesigned SG-1000.[33] For North America, Sega rebranded the Mark III as the Master System,[34] with a futuristic design intended to appeal to Western tastes.[35] The Mark III was released in Japan in October 1985.[36] Despite featuring more powerful hardware than the Famicom in some ways, it was unsuccessful at launch. As Nintendo required third-party developers not to publish their Famicom games on other consoles, Sega developed its own games and obtained the rights to port games from other developers.[32] To help market the console in North America, Sega planned to sell the Master System as a toy, similar to how Nintendo had done with the Nintendo Entertainment System. Sega partnered with Tonka, an American toy company, to make use of Tonka's expertise in the toy industry.[37] Ineffective marketing by Tonka handicapped sales of the Master System.[38] By early 1992, production had ceased in North America. The Master System sold between 1.5 million and 2 million units in the region.[39] This was less market share in North America than both Nintendo and Atari, which controlled 80 percent and 12 percent of the market respectively.[40] The Master System was eventually a success in Europe, where it outsold the NES by a considerable margin.[41] As late as 1993, the Master System's active installed user base in Europe was 6.25 million units.[41] The Master System has had continued success in Brazil. New versions continue to be released by Sega's partner in the region, Tectoy.[42] By 2016, the Master System had sold 8 million units in Brazil.[43]

During 1984, Sega opened its European division of arcade distribution, Sega Europe.[44] It re-entered the North American arcade market in 1985 with the establishment of Sega Enterprises USA at the end of a deal with Bally. The release of Hang-On in 1985 would prove successful in the region, becoming so popular that Sega struggled to keep up with demand for the game.[45] UFO Catcher was introduced in 1985 and as of 2005 was Japan's most commonly installed claw crane game.[46] In 1986, Sega of America was established to manage the company's consumer products in North America, beginning with marketing the Master System.[47] During Sega's partnership with Tonka, Sega of America relinquished marketing and distribution of the console and focused on customer support and some localization of titles.[37] Out Run, released in 1986, became Sega's best selling arcade cabinet of the 1980s.[48] Former Sega director Akira Nagai stated that Hang-On and Out Run helped to pull the arcade game market out of the 1982 downturn and created new genres of video games.[11]

Genesis, Sonic the Hedgehog, and mainstream success (1989–1994)

With the arcade game market once again growing, Sega was one of the most recognized game brands at the end of the 1980s. In the arcades, the company focused on releasing games to appeal to diverse tastes, including racing games and side-scrollers.[49] Sega released the Master System's successor, the Mega Drive, in Japan on October 29, 1988. The launch was overshadowed by Nintendo's release of Super Mario Bros. 3 a week earlier. Positive coverage from magazines Famitsu and Beep! helped establish a following, but Sega only shipped 400,000 units in the first year.[50] The Mega Drive struggled to compete against the Famicom[51] and lagged behind Nintendo's Super Famicom and NEC's PC Engine in Japanese sales throughout the 16-bit era.[52] For the North American launch, where the console was renamed Genesis, Sega had no sales and marketing organization. After Atari declined an offer to market the console in the region, Sega launched it through its own Sega of America subsidiary. The Genesis was launched in New York City and Los Angeles on August 14, 1989, and in the rest of North America later that year.[53] The European version of the Mega Drive was released in September 1990.[54]

Former Atari executive and new Sega of America president Michael Katz developed a two-part strategy to build sales in North America. The first part involved a marketing campaign to challenge Nintendo and emphasize the more arcade-like experience available on the Genesis,[53][55] with slogans including "Genesis does what Nintendon't".[50] Since Nintendo owned the console rights to most arcade games of the time, the second part involved creating a library of games which used the names and likenesses of celebrities, such as Michael Jackson's Moonwalker and Joe Montana Football.[2][56] Nonetheless, Sega had difficulty overcoming Nintendo's ubiquity in homes.[57] Despite being tasked by Nakayama to sell one million units in the first year, Katz and Sega of America sold only 500,000.[50]

After the launch of the Genesis, Sega sought a new flagship series to compete with Nintendo's Mario series.[59] Its new character, Sonic the Hedgehog, went on to feature in one of the best-selling video game franchises in history.[60][61] Sonic the Hedgehog began with a tech demo created by Yuji Naka involving a fast-moving character rolling in a ball through a winding tube; this was fleshed out with Naoto Ohshima's character design and levels conceived by designer Hirokazu Yasuhara.[62] Sonic's color was chosen to match Sega's cobalt blue logo; his shoes were inspired by Michael Jackson's boots, and his personality by Bill Clinton's "can-do" attitude.[63][64][65]

Nakayama hired Tom Kalinske as CEO of Sega of America in mid-1990, and Katz departed soon after. Kalinske knew little about the video game market, but surrounded himself with industry-savvy advisors. A believer in the razor-and-blades business model, he developed a four-point plan: cut the price of the Genesis, create a U.S. team to develop games targeted at the American market, expand the aggressive advertising campaigns, and replace the bundled game Altered Beast with Sonic the Hedgehog. The Japanese board of directors disapproved,[57] but it was approved by Nakayama, who told Kalinske, "I hired you to make the decisions for Europe and the Americas, so go ahead and do it."[50] In large part due to the popularity of Sonic the Hedgehog,[57] the Genesis outsold its main competitor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), in the United States nearly two to one during the 1991 holiday season. By January 1992, Sega controlled 65 percent of the 16-bit console market.[66] Sega outsold Nintendo for four consecutive Christmas seasons[67] due to the Genesis' head start, lower price, and a larger library compared to the SNES at release.[68] Nintendo's dollar share of the U.S. 16-bit market dropped from 60% at the end of 1992 to 37% at the end of 1993,[69] Sega claimed 55% of all 16-bit hardware sales during 1994,[70] and the SNES outsold the Genesis from 1995 through 1997.[71][72][73]

In 1990, Sega launched the Game Gear, a handheld console, to compete against Nintendo's Game Boy. The Game Gear was designed as a portable version of the Master System and featured a full-color screen, in contrast to the monochrome Game Boy screen.[74] Due to its short battery life, lack of original games, and weak support from Sega, the Game Gear did not surpass the Game Boy, having sold approximately 11 million units.[75] Sega launched the Mega-CD in Japan on December 1, 1991, initially retailing at JP¥49,800.[76] The add-on uses CD-ROM technology. Further features include a second, faster processor, vastly expanded system memory, a graphics chip that performed scaling and rotation similar to Sega's arcade games, and another sound chip.[77][78] In North America, it was renamed the Sega CD and launched on October 15, 1992, with a retail price of US$299.[77] It was released in Europe as the Mega-CD in 1993.[76] The Mega-CD sold only 100,000 units during its first year in Japan, falling well below expectations.[76] Sega did have success with arcade games; in 1992 and 1993, the new Sega Model 1 arcade system board showcased in-house development studio Sega AM2's Virtua Racing and Virtua Fighter (the first 3D fighting game), which played a crucial role in popularizing 3D polygonal graphics.[79][80][81][82]

In 1993, the American media began to focus on the mature content of certain video games, such as Night Trap for the Sega CD and the Genesis version of Midway's Mortal Kombat.[83][84] This came at a time when Sega was capitalizing on its image as an "edgy" company with "attitude", and this reinforced that image.[51] To handle this, Sega instituted the United States' first video game ratings system, the Videogame Rating Council (VRC), for all its systems. Ratings ranged from the family-friendly GA rating to the more mature rating of MA-13, and the adults-only rating of MA-17.[84] Executive vice president of Nintendo of America Howard Lincoln was quick to point out in the United States congressional hearings in 1993 that Night Trap was not rated at all. Senator Joe Lieberman called for another hearing in February 1994 to check progress toward a rating system for video game violence.[84] After the hearings, Sega proposed the universal adoption of the VRC; after objections by Nintendo and others, Sega took a role in forming the Entertainment Software Rating Board.[84]

32X, Saturn, and falling sales (1994–1999)

Sega began work on the Genesis' successor, the Sega Saturn, over two years before the system was showcased at the Tokyo Toy Show in June 1994.[85] According to former Sega of America producer Scot Bayless, Nakayama became concerned about the 1994 release of the Atari Jaguar, and that the Saturn would not be available until the next year. As a result, Nakayama decided to have a second console release to market by the end of 1994. Sega began to develop the 32X, a Genesis add-on which would serve as a less expensive entry into the 32-bit era.[86] The 32X would not be compatible with the Saturn, but would play Genesis games.[31] Sega released the 32X on November 21, 1994, in North America, December 3, 1994, in Japan, and January 1995 in PAL territories, and was sold at less than half of the Saturn's launch price.[87][88] After the holiday season, interest in the 32X rapidly declined.[86][89]

Sega released the Saturn in Japan on November 22, 1994.[90] Virtua Fighter, a port of the popular arcade game, sold at a nearly one-to-one ratio with the Saturn at launch and was crucial to the system's early success in Japan.[91][92][93] Sega's initial shipment of 200,000 Saturn units sold out on the first day,[2][93][94] and it was more popular than new competitor Sony's PlayStation in Japan.[93][95] In March 1995, Sega of America CEO Tom Kalinske announced that the Saturn would be released in the U.S. on "Saturnday" (Saturday) September 2, 1995.[96][97] Sega of Japan mandated an early launch to give the Saturn an advantage over the PlayStation.[94] At the first Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) in Los Angeles on May 11, 1995, Kalinske revealed the release price and that Sega had shipped 30,000 Saturns to Toys "R" Us, Babbage's, Electronics Boutique, and Software Etc. for immediate release.[96] The Saturn's release in Europe also came before the previously announced North American date, on July 8, 1995.[98] Within two days of the PlayStation's American launch on September 9, 1995, the PlayStation sold more units than the Saturn had in the five months following its surprise launch.[99][100] Within its first year, the PlayStation secured over 20 percent of the U.S. video game market.[101] The console's high price point, surprise launch causing issues with distributors and third-party developers, and difficulty handling polygonal graphics were factors in its lack of success.[102] Sega also underestimated the continued popularity of the Genesis; sales of 16-bit games and consoles accounted for 64 percent of the market in 1995.[103][104] Despite capturing 43 percent of the dollar share of the U.S. market and selling more than 2 million Genesis units in 1995, Kalinske estimated that Sega could have sold another 300,000 consoles if it had been prepared for demand.[105]

Sega announced that Shoichiro Irimajiri had been appointed chairman and CEO of Sega of America in July 1996, while Kalinske left Sega after September 30 of that year.[106][107] A former Honda executive,[108][109] Irimajiri had been involved with Sega of America since joining Sega in 1993.[106][110] The company also announced that Rosen and Nakayama had resigned from their positions at Sega of America, though both remained with Sega.[106][111] Bernie Stolar, a former executive at Sony Computer Entertainment of America,[112][113] became Sega of America's executive vice president in charge of product development and third-party relations.[106][107] Stolar was not supportive of the Saturn, believing its hardware was poorly designed.[2] While Stolar had stated that "the Saturn is not our future" at E3 1997, he continued to emphasize the quality of its games,[2] and later reflected that "we tried to wind it down as cleanly as we could for the consumer".[113] At Sony, Stolar had opposed the localization of certain Japanese PlayStation games that he felt would not represent the system well in North America. He advocated a similar policy for the Saturn, although he later sought to distance himself from this stance.[2][114][115] Other changes included a softer image in Sega's advertising, including removing the "Sega!" scream, and holding press events for the education industry.[116]

Sega partnered with GE to develop the Model 2 arcade system board, building onto 3D technology in the arcade industry at the time. This led to several successful arcade games, including Daytona USA, launched in a limited capacity in late 1993 and worldwide in 1994. Other popular games included Virtua Cop and Virtua Fighter 2.[117] Aside from the Saturn, Sega made forays in the PC market with the 1995 establishment of SegaSoft, which was tasked with creating original Saturn and PC games.[118][119] In 1996, Sega operated in-door theme parks not only in Japan with Joypolis, but also overseas, with Sega World branded arcades in the UK and Australia.[120][121] From 1994 to 1999, Sega participated in the pinball market when it took over Data East's pinball division.[122]

In January 1997, Sega announced its intentions to merge with the Japanese toymaker Bandai. The merger, planned as a $1 billion stock swap whereby Sega would wholly acquire Bandai, was set to form a company known as Sega Bandai, Ltd.[123][124] Though it was to be finalized in October of that year, it was called off in May after growing opposition from Bandai's midlevel executives. Bandai instead agreed to a business alliance with Sega.[125] As a result of Sega's deteriorating financial situation, Nakayama resigned as Sega president in January 1998 in favor of Irimajiri.[108] Nakayama's resignation may have in part been due to the failure of the merger, as well as Sega's 1997 performance.[126] Stolar became CEO and president of Sega of America.[113][127]

The Saturn failed to take the lead in the market. After the launch of the Nintendo 64 in 1996, sales of the Saturn and its games fell sharply,[113] while the PlayStation outsold the Saturn three-to-one in the U.S. in 1997.[101] Following five years of declining profits,[128] in the fiscal year ending March 31, 1998, Sega suffered its first financial losses since its 1988 listing on the Tokyo Stock Exchange as both a parent company and a corporation as a whole.[129] Shortly before the announcement of the losses, Sega discontinued the Saturn in North America to prepare for the launch of its successor, the Dreamcast.[108][113] The decision effectively left the Western market without Sega games for over one year.[130] The Saturn lasted longer in Japan and Europe,[109] Irimajiri telling Japanese newspaper Daily Yomiuri that Saturn development would stop at the end of 1998 and games would continue to be produced until mid-1999.[131] Sega suffered a further ¥42.881 billion consolidated net loss in the fiscal year ending March 1999, and announced plans to eliminate 1,000 jobs, nearly a quarter of its workforce.[132][133] With lifetime sales of 9.26 million units,[134] the Saturn is considered a commercial failure.[135] Sega's arcade divisions also struggled in the late 1990s, partly due to a market slump following competition from home consoles.[136]

Dreamcast and continuing struggles (1998–2001)

Despite a 75 percent drop in half-year profits just before the Japanese launch of the Dreamcast, Sega felt confident about its new system. The Dreamcast attracted significant interest and drew many pre-orders.[137] Sega announced that Sonic Adventure, the next game starring company mascot Sonic the Hedgehog, would be a Dreamcast launch game. It was promoted with a large-scale public demonstration at the Tokyo Kokusai Forum Hall.[138][139][140] Due to a high failure rate in the manufacturing process, Sega could not ship enough consoles for the Dreamcast's Japanese launch.[137][141] As more than half of its limited stock had been pre-ordered, Sega stopped pre-orders in Japan.[142] Before the launch, Sega announced the release of its New Arcade Operation Machine Idea (NAOMI) arcade system board, which served as a cheaper alternative to the Sega Model 3.[143] NAOMI shared technology with the Dreamcast, allowing nearly identical ports of arcade games.[130][144]

The Dreamcast launched in Japan on November 27, 1998. The entire stock of 150,000 consoles sold out by the end of the day.[142] Irimajiri estimated that another 200,000 to 300,000 Dreamcast units could have been sold with sufficient supply.[142] He hoped to sell over 1 million Dreamcast units in Japan by February 1999, but less than 900,000 were sold. The low sales undermined Sega's attempts to build up a sufficient installed base to ensure the Dreamcast's survival after the arrival of competition from other manufacturers.[145] Before the Western launch, Sega reduced the price of the Dreamcast in Japan by JP¥9,100, effectively making it unprofitable but increasing sales.[137]

On August 11, 1999, Sega of America confirmed that Stolar had been fired.[146] Peter Moore, whom Stolar had hired as a Sega of America executive only six months before,[147] was placed in charge of the North American launch.[146][148][149][150] The Dreamcast launched in North America on September 9, 1999,[130][145][151] with 18 games.[151][152][153] Sega set a record by selling more than 225,132 Dreamcast units in 24 hours, earning $98.4 million in what Moore called "the biggest 24 hours in entertainment retail history".[147] Within two weeks, U.S. Dreamcast sales exceeded 500,000.[147] By Christmas, Sega held 31 percent of the U.S. video game market by revenue.[154] On November 4, Sega announced it had sold over one million Dreamcast units.[155] Nevertheless, the launch was marred by a glitch at one of Sega's manufacturing plants, which produced defective GD-ROMs where data was not properly burned onto the disc.[156] Sega released the Dreamcast in Europe on October 14, 1999.[155] While Sega sold 500,000 units in Europe by Christmas 1999,[137] sales there slowed, and by October 2000 Sega had sold only about 1 million units.[157]

Though the Dreamcast's launch was successful, Sony's PlayStation still held 60 percent of the overall market share in North America at the end of 1999.[155] On March 2, 1999, in what one report called a "highly publicized, vaporware-like announcement",[158] Sony revealed the first details of its "next-generation PlayStation".[159][160] The same year, Nintendo announced that its next console would meet or exceed anything on the market, and Microsoft began development of its own console, the Xbox.[161][162][163] Sega's initial momentum proved fleeting as U.S. Dreamcast sales—which exceeded 1.5 million by the end of 1999[164]—began to decline as early as January 2000.[165] Poor Japanese sales contributed to Sega's ¥42.88 billion ($404 million) consolidated net loss in the fiscal year ending March 2000. This followed a similar loss of ¥42.881 billion the previous year and marked Sega's third consecutive annual loss.[132][166] Sega's overall sales for the term increased 27.4 percent, and Dreamcast sales in North America and Europe greatly exceeded its expectations. However, this coincided with a decrease in profitability due to the investments required to launch the Dreamcast in Western markets and poor software sales in Japan.[132] At the same time, worsening conditions reduced the profitability of Sega's Japanese arcade business, prompting the closure of 246 locations.[132][167]

Moore stated that the Dreamcast would need to sell 5 million units in the U.S. by the end of 2000 to remain viable, but Sega fell short of this goal with some 3 million units sold.[154][168] Moreover, Sega's attempts to spur Dreamcast sales through lower prices and cash rebates caused escalating financial losses.[169] In March 2001, Sega posted a consolidated net loss of ¥51.7 billion ($417.5 million).[170] While the PlayStation 2's October 26 U.S. launch was marred by shortages, this did not benefit the Dreamcast as much as expected, as many disappointed consumers continued to wait or purchased a PSone.[154][171][172] Eventually, Sony and Nintendo held 50 and 35 percent of the U.S. video game market respectively, while Sega held only 15 percent.[137]

Shift to third-party software development (2001–2003)

CSK chairman Isao Okawa replaced Irimajiri as president of Sega on May 22, 2000.[175] Okawa had long advocated that Sega abandon the console business.[176] Others shared this view; Sega co-founder David Rosen had "always felt it was a bit of a folly for them to be limiting their potential to Sega hardware", and Stolar had suggested that Sega should have sold the company to Microsoft.[2][177] In a September 2000 meeting with Sega's Japanese executives and heads of its first-party game studios, Moore and Sega of America executive Charles Bellfield recommended that Sega abandon its console business. In response, the studio heads walked out.[147] Sega announced an official company name change from Sega Enterprises, Ltd. to Sega Corporation effective November 1, 2000. Sega stated in a release that this was to display its commitment to its "network entertainment business".[178]

On January 23, 2001, Japanese newspaper Nihon Keizai Shinbun reported that Sega would cease production of the Dreamcast and develop software for other platforms.[179] After an initial denial, Sega of Japan released a press release confirming it was considering producing software for the PlayStation 2 and Game Boy Advance as part of its "new management policy".[180] On January 31, 2001, Sega announced the discontinuation of the Dreamcast after March 31 and the restructuring of the company as a "platform-agnostic" third-party developer.[181][182] Sega also announced a Dreamcast price reduction to eliminate its unsold inventory, estimated at 930,000 units as of April 2001.[183][184] This was followed by further reductions to clear the remaining inventory.[185][186] The final manufactured Dreamcast was autographed by the heads of all nine of Sega's first-party game studios, plus the heads of sports game developer Visual Concepts and audio studio Wave Master, and given away with 55 first-party Dreamcast games through a competition organized by GamePro.[187]

Okawa, who had loaned Sega $500 million in 1999, died on March 16, 2001. Shortly before his death, he forgave Sega's debts to him and returned his $695 million worth of Sega and CSK stock, helping the company survive the third-party transition.[188][189][190] He held failed talks with Microsoft about a sale or merger with their Xbox division.[191] According to former Microsoft executive Joachim Kempin, Microsoft founder Bill Gates decided against acquiring Sega because "he didn't think that Sega had enough muscle to eventually stop Sony".[192] As part of the restructuring, nearly one third of Sega's Tokyo workforce was laid off in 2001.[193] 2002 was Sega's fifth consecutive fiscal year of net losses.[194] After Okawa's death, Hideki Sato, a 30-year Sega veteran who had worked on Sega's consoles, became company president. Following poor sales in 2002, Sega cut its profit forecast for 2003 by 90 percent, and explored opportunities for mergers. In 2003, Sega began talks with Sammy Corporation–a pachinko and pachislot manufacturing company–and video game company Namco. The president of Sammy, Hajime Satomi, had a history with Sega, as he was mentored by Isao Okawa and was previously asked to be CEO of Sega.[195] On February 13, Sega announced that it would merge with Sammy but, as late as April 17, Sega was still in talks with Namco, which was attempting to overturn the merger. Sega's consideration of Namco's offer upset Sammy executives. The day after Sega announced it was no longer planning to merge with Sammy, Namco withdrew its offer.[196] In 2003, Sato and COO Tetsu Kamaya stepped down, Sato being replaced by Hisao Oguchi, the head of the Sega studio Hitmaker.[197]

After the decline of the global arcade industry around the 21st century, Sega introduced several novel concepts tailored to the Japanese market. Derby Owners Club was an arcade machine with memory cards for data storage, designed to take over half an hour to complete and costing JP¥500 to play. Testing of Derby Owners Club in an arcade in Chicago showed that it became the most popular machine in the arcade, with a 92% replay rate. While the eight-player Japanese version of the game was released in 1999, the game was reduced to a smaller four-player version due to size issues and released in North America in 2003.[198] Sega introduced trading card game machines, with games such as World Club Champion Football for general audiences and Mushiking: The King of Beetles for young children. The company also introduced internet functionality in arcades with Virtua Fighter 4 in 2001, and further enhanced it with ALL.Net, a network system for arcade games, introduced in 2004.[199]

Sammy takeover and business expansion (2003–2015)

In August 2003, Sammy bought 22.4 percent of Sega's shares from CSK, making Sammy into Sega's largest shareholder.[200][201] In the same year, Hajime Satomi stated that Sega's activity would focus on its profitable arcade business as opposed to loss-incurring home software development.[202] In 2004, Sega Sammy Holdings, an entertainment conglomerate, was created; Sega and Sammy became subsidiaries of the new holding company, both companies operating independently while the executive departments merged. According to the first Sega Sammy Annual Report, the merger went ahead as both companies were facing difficulties. Satomi stated that Sega had been operating at a loss for nearly 10 years,[203] while Sammy feared stagnation and overreliance of its highly profitable pachislot and pachinko machine business and wanted to diversify.[46] Sammy acquired the remaining percentages of Sega, completing a takeover.[204] The stock swap deal valued Sega between $1.45 billion and $1.8 billion.[203][205] Sega Sammy Holdings was structured into four parts: Consumer Business (video games), Amusement Machine Business (arcade games), Amusement Center Business (Sega's theme parks and arcades) and Pachislot and Pachinko Business (Sammy's pachinko and pachislot business).[206]

In the console and handheld business, Sega found success with games targeted at the Japanese market such as the Yakuza and Hatsune Miku: Project DIVA series while also distributing games from smaller Japanese game developers and localizations of Western games in Japan.[207][208] Sega's most successful arcade games at the time, such as Sangokushi Taisen and Border Break, continued to be based on network and card systems. Arcade machine sales incurred higher profits than the company's console, mobile and PC games on a year-to-year basis until the fiscal year of 2014.[209] In 2004, the GameWorks chain of arcades came under Sega ownership, until it was sold in 2011. In 2009, Sega Republic, an indoor theme park, opened in Dubai. The next year, Sega began providing the 3D imaging for Hatsune Miku's holographic concerts.[210] In 2013, Index Corporation was purchased by Sega Sammy after going bankrupt.[211] After the buyout, Sega implemented a corporate spin-off with Index. The latter's game assets were rebranded as Atlus, a wholly owned subsidiary of Sega.[212]

Due in part to the decline of packaged game sales worldwide in the 2010s,[213] Sega began layoffs and closed five offices based in Europe and Australia on July 1, 2012.[214] This was to focus on the digital game market, such as PC and mobile devices.[215][216] Strong performers for Sega on these platforms include Phantasy Star Online 2 and Chain Chronicle.[217] Sega gradually reduced its arcade centers from 450 in 2005[218] to around 200 in 2015.[219] In the mobile market, Sega released its first app on the iTunes Store with a version of Super Monkey Ball in 2008. The Western lineup consisted of emulations of games and pay-to-play apps. These were eventually overshadowed by free-to-play games, leading to 19 older mobile games being pulled due to quality concerns in May 2015.[220][221] In 2012, Sega also began acquiring studios for mobile development, studios such as Hardlight, Three Rings Design, and Demiurge Studios becoming fully owned subsidiaries.[222][223][224]

To streamline operations, Sega established operational firms for each of its businesses in the 2010s. In 2012, Sega established Sega Networks as a subsidiary company for its mobile games.[225] The same year, Sega Entertainment was established for Sega's amusement facility business.[226] In January 2015, Sega of America announced its relocation from San Francisco to Atlus USA's headquarters in Irvine, California, which was completed later that year.[227] From 2005 to 2015, Sega's operating income generally saw improvements compared to Sega's past financial problems, but was not profitable every year.[228]

| Business year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amusement Machine Sales[228] | 7,423 | 12,176 | 11,682 | 7,152 | 6,890 | 7,094 | 7,317 | 7,415 | 1,902 | -1,264 | -2,356 |

| Amusement Center Operations[228] | 5,472 | 9,244 | 132 | -9,807 | -7,520 | -1,338 | 342 | 355 | 1,194 | 60 | -946 |

| Consumer Business[228] | -8,809 | 9,244 | 1,748 | -5,989 | -941 | 6,332 | 1,969 | -15,182 | -732 | 2,089 | 4033 |

Restructuring (2015–present)

In April 2015, Sega Corporation was reorganized into Sega Group, one of three groups of Sega Sammy Holdings. Sega Holdings Co., Ltd. was established, with four business sectors under its control. Haruki Satomi, son of Hajime Satomi, took office as president and CEO of the company in April 2015.[229][230] Sega Games Co., Ltd. became the legal name of Sega Corporation and continued to manage home video games, while Sega Interactive Co., Ltd. was founded to take control of the arcade division.[231][232] Sega Networks merged with Sega Games Co., Ltd. in 2015.[225] At the Tokyo Game Show in September 2016, Sega announced that it had acquired the intellectual property and development rights to all games developed and published by Technosoft.[233]

Sega Sammy Holdings announced in April 2017 that it would relocate its head office functions and domestic subsidiaries located in the Tokyo metropolitan area to Shinagawa-ku by January 2018. This was to consolidate scattered head office functions including Sega Sammy Holdings, Sammy Corporation, Sega Holdings, Sega Games, Atlus, Sammy Network, and Dartslive.[234] Sega's previous headquarters in Ōta was sold in 2019 and will likely be torn down.[235] In June 2018, Gary Dale, formerly of Rockstar Games and Take-Two Interactive, replaced Chris Bergstresser as president and COO of Sega Europe.[236] A few months later, Ian Curran, a former executive at THQ and Acclaim Entertainment, replaced John Cheng as president and COO of Sega of America in August 2018.[237] In October 2018, Sega reported favorable western sales results from games such as Yakuza 6 and Persona 5, due to the localization work of Atlus USA.[238]

Despite a 35-percent increase in the sale of console games and success in its PC game business, profits fell 70 percent for the 2018 fiscal year in comparison to the previous year, mainly due to the digital games market which includes mobile games as well as Phantasy Star Online 2. In response, Sega announced that for its digital games it would focus on releases for its existing intellectual property and also focus on growth areas such as packaged games in the overseas market. Sega blamed the loss on market miscalculations and having too many games under development. Projects in development at Sega included a new game in the Yakuza series, Persona 5 Scramble: The Phantom Strikers, the Sonic the Hedgehog film, and the Sega Genesis Mini,[239][240] which was released in September 2019.[241] In May 2019, Sega acquired Two Point Studios, known for its positively reviewed Two Point Hospital.[242][243]

On April 1, 2020, Sega Interactive merged with Sega Games Co., Ltd. The company was again renamed Sega Corporation, while Sega Holdings Co., Ltd. was renamed Sega Group Corporation.[244] According to a company statement, the move was made to allow greater research and development flexibility.[245] In April 2020, Sega sold Demiurge Studios to Demiurge co-founder Albert Reed. Demiurge said it would continue to support the mobile games it developed under Sega.[246]

In June, as part of its 60th anniversary, Sega announced the Game Gear Micro microconsole, scheduled for October 6, 2020 in Japan.[247] Sega also announced its Fog Gaming platform, which will use the unused processing power of arcade machines in Japanese arcades overnight to help power cloud gaming applications.[247]

Corporate structure

Sega's headquarters is in Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Sega also has offices in Irvine, California (as Sega of America), in London (as Sega Europe),[248] in Seoul, South Korea (as Sega Publishing Korea),[249] and in Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Taipei.[250] In other regions, Sega has contracted distributors for its games and consoles, such as Tectoy in Brazil.[32] Sega has had offices in France, Germany, Spain, and Australia;[214] those markets have since contracted distributors.[251]

Relations between the regional offices have not always been smooth.[252] Some conflict in the 1990s may have been caused by Sega president Nakayama and his admiration for Sega of America; according to Kalinske, "There were some guys in the executive suites who really didn't like that Nakayama in particular appeared to favor the U.S. executives. A lot of the Japanese executives were maybe a little jealous, and I think some of that played into the decisions that were made."[2] By contrast, author Steven L. Kent stated that Nakayama bullied American executives and that Nakayama believed the Japanese executives made the best decisions. Kent also stated that Sega of America CEOs Kalinske, Stolar, and Moore dreaded meeting with Sega of Japan executives.[253]

Subsidiaries of Sega Group Corporation

After the formation of Sega Group in 2015 and the founding of Sega Holdings (now Sega Group Corporation), the former Sega Corporation was renamed Sega Games Co., Ltd.[232] Under this structure, Sega Games was responsible for the home video game market and consumer development, while Sega Interactive Co., Ltd., comprised Sega's arcade game business.[231] The two were consolidated in 2020, renamed as Sega Corporation.[245] The company includes Sega Networks, which handles game development for smartphones.[229] Sega Corporation develops and publishes games for major video game consoles and arcade cabinets, and has not expressed interest in developing consoles again. According to former Sega Europe CEO Mike Brogan, "There is no future in selling hardware. In any market, through competition, the hardware eventually becomes a commodity... If a company has to sell hardware then it should only be to leverage software, even if that means taking a hit on the hardware."[51]

Sega Toys Co., Ltd. has created toys for children's franchises such as Oshare Majo: Love and Berry, Mushiking: King of the Beetles, Lilpri, Bakugan, Jewelpet, Rilu Rilu Fairilu, Dinosaur King and Hero Bank. Products released in the West include the home planetarium Homestar and the robot dog iDog. The Homestar was released in 2005 and has been improved several times. Its newest model, Flux, was released in 2019. The series is developed by the Japanese inventor and entrepreneur Takayuki Ohira. As a recognized specialist for professional planetariums, he has received numerous innovation prizes and supplies large planetariums internationally with his company Megastar. Sega Toys also inherited the Sega Pico handheld system and produced Pico software.[254] Sega has operations of bowling alleys and arcades through its Sega Entertainment Co., Ltd. subsidiary.[231] Since its first arcade opened in Japan in 1970, Sega has maintained a presence in operating arcades there, but has not been consistently successful in other territories.[255] Its DartsLive subsidiary creates electronic darts games,[250] while Sega Logistics Service distributes and repairs arcade games.[231] In 2015, Sega and Japanese advertising agency Hakuhodo formed a joint venture, Stories LLC, to create entertainment for film and TV. Stories LLC has exclusive licensing rights to adapt Sega properties into film and television,[256][257] and has partnered with producers to develop series based on properties including Shinobi, Golden Axe, Virtua Fighter, The House of the Dead, and Crazy Taxi.[258]

Software research and development

As a games publisher, Sega produces games through its research and development teams. The Sonic the Hedgehog franchise, maintained through Sega's Sonic Team division, is one of the best-selling franchises in the history of video games.[259] Sega has also acquired third-party studios that are now owned by the company, including Amplitude Studios,[260] Atlus,[212] Creative Assembly,[261] Hardlight,[224] Relic Entertainment,[262] Sports Interactive,[263] and Two Point Studios.[242][243]

Sega's software research and development teams began with one development division operating under Sega's longtime head of R&D, Hisashi Suzuki. As the market increased for home video game consoles, Sega expanded with three Consumer Development (CS) divisions. After October 1983, arcade development expanded to three teams: Sega DD No. 1, 2, and 3. Some time after the release of Power Drift, the company restructured its teams again as the Sega Amusement Machine Research and Development Teams, or AM teams. Each arcade division was segregated, and a rivalry existed between the arcade and consumer development divisions.[264] In what has been called "a brief moment of remarkable creativity",[130] in 2000, Sega restructured its arcade and console development teams into nine semi-autonomous studios headed by the company's top designers.[2][151][265] The studios were United Game Artists, Smilebit, Hitmaker, Sega Rosso, Sega Wow, Overworks, Amusement Vision, Sega AM2, and Sonic Team.[130][266] Sega's design houses were encouraged to experiment and benefited from a relatively lax approval process.[267] After taking over as company president in 2003, Hisao Oguchi announced his intention to consolidate Sega's studios.[197] Prior to the acquisition by Sammy, Sega began the process of re-integrating its subsidiaries into the main company.[268]

Sega still operates first-party studios as departments of its research and development division. Sonic Team exists as Sega's CS2 research and development department,[269] while Sega's CS3 department has developed games such as Phantasy Star Online 2,[270] and Sega Interactive's AM2 department has more recently worked on projects such as smartphone game Soul Reverse Zero.[271] Toshihiro Nagoshi, formerly the head of Amusement Vision, remains involved with research and development as Sega's chief creative officer while working on the Yakuza series.[272]

Legacy

Sega is the world's most prolific arcade game producer, having developed more than 500 games, 70 franchises, and 20 arcade system boards since 1981. It has been recognized by Guinness World Records for this achievement.[273] Of Sega's arcade division, Eurogamer's Martin Robinson said, "It's boisterous, broad and with a neat sense of showmanship running through its range. On top of that, it has something that's often evaded its console-dwelling cousin: success."[274]

The Sega Genesis is often ranked among the best consoles in history.[275][276][277] In 2014, USgamer's Jeremy Parish credited it for galvanizing the market by breaking Nintendo's near-monopoly, helping create modern sports game franchises, and popularizing television games in the UK.[278] Kalinske felt Sega had innovated by developing games for an older demographic and pioneering the "street date" concept with the simultaneous North American and European release of Sonic the Hedgehog 2.[279] Sega of America's marketing campaign for the Genesis influenced marketing for later consoles.[280]

Despite its commercial failure, the Saturn is well regarded for its library,[98][281][282] though it has been criticized for a lack of high-profile franchise releases.[2] Edge wrote that "hardened loyalists continue to reminisce about the console that brought forth games like Burning Rangers, Guardian Heroes, Dragon Force and Panzer Dragoon Saga".[283] Sega's management was criticized for its handling of the Saturn.[2][98] According to Greg Sewart of 1Up.com, "the Saturn will go down in history as one of the most troubled, and greatest, systems of all time".[281]

The Dreamcast is remembered for being ahead of its time,[284][285][286] with several concepts that became standard in consoles, such as motion controls and online functionality.[287] Its demise has been connected with transitions in the video game industry. In 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die, Duncan Harris wrote that the Dreamcast's end "signaled the demise of arcade gaming culture ... Sega's console gave hope that things were not about to change for the worse and that the tenets of fast fun and bright, attractive graphics were not about to sink into a brown and green bog of realistic war games."[288] Parish contrasted the Dreamcast's diverse library with the "suffocating sense of conservatism" that pervaded the industry in the following decade.[289]

In Eurogamer, Damien McFerran wrote that Sega's decisions in the late 1990s were "a tragic spectacle of overconfidence and woefully misguided business practice".[51] Travis Fahs of IGN noted that since the Sammy takeover Sega had developed fewer games and outsourced to more western studios, and that its arcade operations had been significantly reduced. Nonetheless, he wrote: "Sega was one of the most active, creative, and productive developers the industry has ever known, and nothing that can happen to their name since will change that."[2] In 2015, Sega president Haruki Satomi told Famitsu that, in the previous ten years, Sega had "betrayed" the trust of older fans and that he hoped to re-establish the Sega brand.[290] During the promotion of the Sega Genesis Mini, Sega executive manager Hiroyuki Miyazaki reflected on Sega's history, saying, "I feel like Sega has never been the champion, at the top of all the video game companies, but I feel like a lot of people love Sega because of the underdog image."[291] In his 2018 book The Sega Arcade Revolution, Horowitz connected Sega's decline in the arcades after 1995 with broader industry changes. He argued that its most serious problems came from the loss of its creative talent, particularly Yuji Naka and Yu Suzuki, after the Sammy takeover, but concluded that "as of this writing, Sega is in its best financial shape of the past two decades. The company has endured."[292]

See also

Notes

- ^ Japanese: 株式会社セガ, Hepburn: Kabushiki gaisha Sega

- ^ Japanese: 日本娯楽物産株式会社, Hepburn: Nihon goraku bussan kabushiki gaisha, Japanese Amusement Products Co., Ltd.

- ^ Japanese: 日本機械製造株式会社, Hepburn: Nihon kikai seizō kabushiki gaisha, Japanese Machine Manufacturers Co., Ltd.

- ^ Japanese: 株式会社セガ・エンタープライゼズ, Hepburn: Kabushiki gaisha Sega Entapuraizezu

References

- ^ Smith, Alexander (2019). They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies That Shaped the Video Game Industry, Vol. I: 1971–1982. CRC Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-429-75261-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Fahs, Travis (April 21, 2009). "IGN Presents the History of SEGA". IGN. Archived from the original on August 24, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (April 4, 2011). "Meet the four Americans who built Sega". Kotaku. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ Sánchez-Crespo Dalmau, Daniel (2004). Core Techniques and Algorithms in Game Programming. New Riders. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-13-102009-2. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Horowitz, Ken (2018). The Sega Arcade Revolution, A History in 62 Games. McFarland & Company. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-1-4766-3196-7.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Prima Publishing. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ "Sammy Corporation and SEGA Corporation Announce Business Combination: SEGA SAMMY HOLDINGS INC". Business Wire. May 19, 2004. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Sega and Utamatic Purchase Assets of Service Games". Billboard. Vol. 72, no. 34. September 5, 1960. p. 71.

- ^ "Service Games Inc. Bought By Sega and Uta Matic". Cashbox. Vol. 21, no. 51. September 3, 1960. p. 52.

- ^ Horowitz 2018, p. 7

- ^ a b c d Sega Arcade History (in Japanese). Enterbrain. 2002. pp. 20–23. ISBN 978-4-7577-0790-0.

- ^ Horowitz 2018, pp. 10–11

- ^ a b Horowitz 2018, pp. 14–16

- ^ Horowitz 2018, pp. 21–23

- ^ a b Pollack, Andrew (July 4, 1993). "Sega Takes Aim at Disney's World". The New York Times. pp. 3–1. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Brandt, Richard; Gross, Neil (February 20, 1994). "Sega!". Businessweek. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Horowitz 2018, pp. 24–26

- ^ Horowitz 2018, p. 36

- ^ Horowitz 2018, p. 48

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (October 24, 1982). "What's New In Video Games; Taking the Zing Out of the Arcade Boom". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "The Bottom Line". Miami Herald. August 27, 1983. p. 5D. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013 – via NewsBank(subscription required).

- ^ Horowitz 2018, p. 64

- ^ Battelle, John (December 1993). "The Next Level: Sega's Plans for World Domination". Wired. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Marley, Scott (December 2016). "SG-1000". Retro Gamer. No. 163. pp. 56–61.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (October 2, 2009). "Playing the SG-1000, Sega's First Game Machine". Wired. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (January 19, 2017). "The Story of Sega's First Console, Which Was Not The Master System". Kotaku. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Marley, Scott (December 2016). "The Rare Jewels from Taiwan...". Retro Gamer. No. 163. p. 61.

- ^ "Rosen Departs Sega". Cashbox. Vol. 45, no. 24. November 12, 1983. p. 32.

- ^ "G&W Wins Cheers $1 Billion Spinoff Set". Miami Herald. Associated Press. August 16, 1983. p. 6D. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013 – via NewsBank(subscription required).

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 343. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ a b Kent 2001, p. 494. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ a b c McFerran, Damien (December 2007). "Retroinspection: Master System". Retro Gamer. No. 44. pp. 48–53.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (February 27, 2012). "The Story of Sega's First Ever Home Console". Kotaku. Archived from the original on September 15, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ "Bruce Lowry: The Man That Sold the NES". Game Informer. Vol. 12, no. 110. June 2002. pp. 102–103.

- ^ Parkin, Simon (June 2, 2014). "A history of video game hardware: Sega Master System". Edge. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Mark III" (in Japanese). Sega. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ a b Horowitz, Ken (2016). Playing at the Next Level: A History of American Sega Games. McFarland & Company. pp. 6–15. ISBN 978-1-4766-2557-7.

- ^ Williams, Mike (November 21, 2013). "Next Gen Graphics, Part 1: NES, Master System, Genesis, and Super NES". USgamer. Archived from the original on May 22, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Matheny, Dave (October 15, 1991). "16-Bit Hits – New video games offer better graphics, action". Minneapolis Star Tribune. p. 01E. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2014 – via NewsBank(subscription required).

- ^ "Company News; Nintendo Suit by Atari Is Dismissed". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 16, 1992. pp. 1–40. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "Sega Consoles: Active installed base estimates". Screen Digest. March 1995. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Smith, Ernie (July 27, 2015). "Brazil Is An Alternate Video Game Universe Where Sega Beat Nintendo". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Azevedo, Théo (May 12, 2016). "Console em produção há mais tempo, Master System já vendeu 8 mi no Brasil". Universo Online (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ Horowitz 2018, pp. 76–77

- ^ Horowitz 2018, pp. 85–89

- ^ a b "Sega Sammy Holdings Annual Report 2005" (PDF). Sega Sammy Holdings. September 5, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Horowitz 2018, p. 151

- ^ Thorpe, Nick (June 2016). "The History of OutRun". Retro Gamer. No. 156. pp. 20–29.

- ^ Horowitz 2018, p. 141

- ^ a b c d Szczepaniak, John (August 2006). "Retroinspection: Mega Drive". Retro Gamer. No. 27. pp. 42–47. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015 – via Sega-16.

- ^ a b c d McFerran, Damien (February 22, 2012). "The Rise and Fall of Sega Enterprises". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 447

- ^ a b Kent 2001, p. 405

- ^ "Data Stream". Edge. No. 5. February 1994. p. 16.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (April 28, 2006). "Interview: Michael Katz". Sega-16. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 406–408

- ^ a b c Kent 2001, pp. 424–431

- ^ Lee, Dave (June 23, 2011). "Twenty years of Sonic the Hedgehog". BBC News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (April 6, 2011). "Remembering Sega's Exiled Mascot". Kotaku. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Harris, Blake (2014). Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo, and the Battle that Defined a Generation. HarperCollins. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-06-227669-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Smith, Jamin (June 23, 2011). "Sonic the Hedgehog celebrates his 20th birthday". VideoGamer. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ "Sonic's Architect: GI Interviews Hirokazu Yasuhara". Game Informer. Vol. 13, no. 124. August 2003. pp. 114–116.

- ^ "Sonic Boom: The Success Story of Sonic the Hedgehog". Retro Gamer—The Mega Drive Book. 2013. p. 31.

- ^ Sheffield, Brandon (December 4, 2009). "Out of the Blue: Naoto Ohshima Speaks". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (December 7, 2009). "Sonic's Shoes Inspired by Michael Jackson". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- ^ "This Month in Gaming History". Game Informer. Vol. 12, no. 105. January 2002. p. 117.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 496–497

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 434–449

- ^ Gross, Neil (February 20, 1994). "Nintendo's Yamauchi: No More Playing Around". Businessweek. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ Dillon, Roberto (2016). The Golden Age of Video Games: The Birth of a Multibillion Dollar Industry. CRC Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-4398-7324-3.

- ^ "Game-System Sales". Newsweek. January 14, 1996. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ "Sega tops holiday, yearly sales projections; Sega Saturn installed base reaches 1.6 million in U.S., 7 million worldwide". Business Wire. January 13, 1997. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ "Sega farms out Genesis". CBS. March 2, 1998. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (October 9, 2008). "Remember Game Gear?". IGN. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ Dillon 2016, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Birch, Aaron (September 2005). "Next Level Gaming: Sega Mega-CD". Retro Gamer. No. 17. pp. 36–42.

- ^ a b Kent 2001, pp. 449–461

- ^ "Behind the Screens at Sega of Japan". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Vol. 3, no. 29. December 1991. pp. 115, 122.

- ^ Feit, Daniel (September 5, 2012). "How Virtua Fighter Saved PlayStation's Bacon". Wired. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ Thomason, Steve (July 2006). "The Man Behind the Legend". Nintendo Power. Vol. 19, no. 205. p. 72.

- ^ Leone, Matt (2010). "The Essential 50 Part 35: Virtua Fighter". 1Up.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Donovan, Tristan (2010). Replay: The History of Video Games. Yellow Ant. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-9565072-0-4.

- ^ "Television Violence". Hansard. December 16, 1993. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Kent 2001, p. 461–480

- ^ "EGM Interviews SEGA SATURN Product Manager HIDEKI OKAMURA". EGM2. Vol. 1, no. 1. July 1994. p. 114.

- ^ a b McFerran, Damien (June 2010). "Retroinspection: Sega 32X". Retro Gamer. No. 77. pp. 44–49.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (October 24, 2008). "32X Follies". IGN. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^ "Super 32X" (in Japanese). Sega. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Beuscher, David. "Sega Genesis 32X – Overview". AllGame. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ "Sega Saturn" (in Japanese). Sega. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 501–502. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ "Virtua Fighter Review". Edge. December 22, 1994. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Sega and Sony Sell the Dream". Edge. Vol. 3, no. 17. February 1995. pp. 6–9.

- ^ a b Harris 2014, p. 536.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 502. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ a b Kent 2001, p. 516. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ "Let the games begin: Sega Saturn hits retail shelves across the nation Sept. 2; Japanese sales already put Sega on top of the charts". Business Wire. March 9, 1995. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c McFerran, Damien (February 2007). "Retroinspection: Sega Saturn". Retro Gamer. No. 34. pp. 44–49.

- ^ "History of the PlayStation". IGN. August 27, 1998. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 519–520. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ a b Mäyrä, Frans (editor); Finn, Mark (2002). "Console Games in the Age of Convergence". Computer Games and Digital Cultures: Conference Proceedings: Proceedings of the Computer Games and Digital Cultures Conference, June 6–8, 2002, Tampere, Finland. Tampere University Press. pp. 45–58. ISBN 978-951-44-5371-7.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ Thorpe, Nick (November 2014). "20 Years: Sega Saturn". Retro Gamer. No. 134. pp. 20–29.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 531. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Gallagher, Scott; Park, Seung Ho (February 2002). "Innovation and Competition in Standard-Based Industries: A Historical Analysis of the U.S. Home Video Game Market". IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 49 (1): 67–82. doi:10.1109/17.985749.

- ^ a b c d "Sega of America appoints Shoichiro Irimajiri chairman/chief executive officer". M2PressWIRE. July 16, 1996. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014 – via M2(subscription required).

- ^ a b "Kalinske Out – WORLD EXCLUSIVE". Next Generation. July 16, 1996. Archived from the original on December 20, 1996. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c Strom, Stephanie (March 14, 1998). "Sega Enterprises Pulls Its Saturn Video Console From the U.S. Market". The New York Times. p. D-2. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Kent 2001, p. 559. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ "Irimajiri Settles In At Sega". Next Generation. July 25, 1996. Archived from the original on December 20, 1996. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 535. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ "NEWSFLASH: Sega Planning Drastic Management Reshuffle – World Exclusive". Next Generation. July 13, 1996. Archived from the original on December 20, 1996. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Kent 2001, p. 558. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 506. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Johnston, Chris (September 8, 2009). "Stolar Talks Dreamcast". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 533. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Horowitz 2018, pp. 198–210

- ^ "Sega's Bold Leap to PC". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 78. January 1996. p. 22.

- ^ "Trailing Sony, Sega Restructures". GamePro. No. 89. February 1996. p. 16.

- ^ "Sega creates alternate reality". Edge. No. 32. May 1996. p. 10.

- ^ "The History of Sega". Sega Amusements. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Rossignoli, Marco (2011). The Complete Pinball Book: Collecting the Game and Its History. Schiffer Publishing, Limited. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7643-3785-7.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (August 9, 2011). "When Sega Wanted to Take Over the World (and Failed Miserably)". Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (January 24, 1997). "Sega to Acquire Bandai, Creating Toy-Video Giant". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ "Bandai Calls Off Planned Merger with Sega". Wired. May 28, 1997. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ "Sega President Leaving?". GameSpot. April 28, 2000. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Feldman, Curt (April 28, 2000). "Katana Strategy Still on Back Burner". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Sega Enterprises Annual Report 1998" (PDF). Sega. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 4, 2004. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ "Sega News From Japan". GameSpot. April 28, 2000. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Fahs, Travis (September 9, 2010). "IGN Presents the History of Dreamcast". IGN. Archived from the original on September 28, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "The 'Q'". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 114. January 1999. p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e "Sega Corporation Annual Report 2000" (PDF). Sega. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ King, Sharon R. (July 12, 1999). "TECHNOLOGY; Sega Is Giving New Product Special Push". The New York Times. p. C-4. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ Ernkvist, Mirko (2012). "Console Hardware: The Development of Nintendo Wii". In Zackariasson, Peter; Wilson, Timothy L. (eds.). The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-138-80383-1.

- ^ Lefton, Terry (1998). "Looking for a Sonic Boom". Brandweek. Vol. 9, no. 39. pp. 26–29.

- ^ Horowitz 2018, pp. 211–212

- ^ a b c d e McFerran, Damien (May 2008). "Retroinspection: Dreamcast". Retro Gamer. No. 50. pp. 66–72. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 17, 2020 – via NintendoLife.

- ^ Ohbuchi, Yutaka (April 28, 2000). "Sonic Onboard Dreamcast". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ "International News: Sonic Rocks Tokyo". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Vol. 10, no. 112. November 1998. p. 50.

- ^ "News: Sonic's Back!". Sega Saturn Magazine. Vol. 4, no. 36. October 1998. pp. 6–8.

- ^ "Sega Dreamcast". Game Makers. Episode 302. August 20, 2008. G4. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Kent 2001, p. 563. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Ohbuchi, Yutaka (April 28, 2000). "How Naomi Got Its Groove On". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Hagiwara, Shiro; Oliver, Ian (November–December 1999). "Sega Dreamcast: Creating a Unified Entertainment World". IEEE Micro. 19 (6): 29–35. doi:10.1109/40.809375.

- ^ a b Kent 2001, p. 564. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ a b Kennedy, Sam (September 8, 2009). "A Post-Bernie Sega Speaks". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Perry, Douglass (September 9, 2009). "The Rise And Fall Of The Dreamcast". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 564–565. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ "Dreamcast: In the USA". Next Generation. Vol. 2, no. 9. September 2000. pp. 6–9.

- ^ "News Bytes". Next Generation. Vol. 1, no. 3. November 1999. p. 14.

- ^ a b c Parish, Jeremy (September 3, 2009). "9.9.99, A Dreamcast Memorial". 1Up.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Gantayat, Anoop (September 9, 2008). "IGN Classics: Dreamcast Launch Guide". IGN. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Kato, Matthew (October 30, 2013). "Which Game Console Had The Best Launch Lineup?". Game Informer. p. 4. Archived from the original on December 30, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Cliff (December 18, 2000). "Sega vs. Sony: Pow! Biff! Whack!". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019 – via Bloomberg News(subscription required).

- ^ a b c "Dreamcast beats PlayStation record". BBC News. November 24, 1999. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Defective Dreamcast GD-ROMs". GameSpot. April 27, 2000. Archived from the original on April 1, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Bye, John (October 17, 2000). "Dreamcast – thanks a million". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ Croal, N'Gai (March 6, 2000). "The Art of the Game: The Power of the PlayStation Is Challenging Designers to Match Its Capabilities-And Forcing Sony's Competitors to Rethink Their Strategies". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 560–561. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Parkin, Simon (June 25, 2014). "A history of videogame hardware: Sony PlayStation 2". Edge. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 563, 574. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ DeMaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (2004). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games. McGraw-Hill/Osborne. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-07-223172-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Parkin, Simon (June 27, 2014). "A history of videogame hardware: Xbox". Edge. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ Davis, Jim (January 2, 2002). "Sega's sales fly despite business woes". CNET. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 566. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ "Sega warns of losses". BBC News. February 28, 2000. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 582. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 581, 588. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ "Dreamcast may be discontinued, Sega says". USA Today. Associated Press. January 24, 2001. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ "Sega Corporation Annual Report 2001" (PDF). Sega. August 2001. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Becker, David (March 2, 2002). "Old PlayStation tops holiday game console sales". CNET. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 585–588. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ "Sega Corporation Annual Report 2002" (PDF). Sega. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ^ "Sega Corporation Annual Report 2004" (PDF). Sega. pp. 2, 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 25, 2009. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 581–582. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 577, 582. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (April 2001). "A Few Words on Sega, From the Founder". Next Generation. Vol. 3, no. 4. p. 9.

- ^ "Sega Enterprises, Ltd. Changes Company Name". Sega. November 1, 2001. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Justice, Brandon (January 23, 2001). "Sega Sinks Console Efforts?". IGN. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop (January 23, 2001). "Sega Confirms PS2 and Game Boy Advance Negotiations". IGN. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- ^ Kent 2001, pp. 588–589. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKent2001 (help)

- ^ Ahmed, Shahed (January 31, 2001). "Sega announces drastic restructuring". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ "Revisions to Annual Results Forecasts" (PDF). Sega. October 23, 2001. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ "Sega pulls plug on Dreamcast". Next Generation. Vol. 3, no. 4. April 2001. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Ahmed, Shahed (May 17, 2006). "Sega drops Dreamcast price again". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2014.