Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

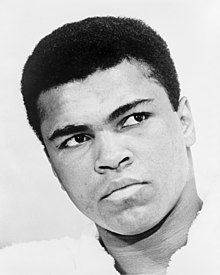

Ali in 1967 | |||||||||||||||

| Born | Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. January 17, 1942 Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Died | June 3, 2016 (aged 74) Scottsdale, Arizona, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Cause of death | Septic shock | ||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Cave Hill Cemetery, Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Monuments |

| ||||||||||||||

| Other names |

| ||||||||||||||

| Education | Central High School (1958)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Criminal charge | Draft evasion[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Criminal penalty | Five years in prison (not served), fined $10,000 and banned from boxing for three years[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Criminal status | Conviction overturned[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

| ||||||||||||||

| Children | 9, including Laila Ali[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr. Odessa Grady Clay[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Awards | List of awards

| ||||||||||||||

| Boxing career | |||||||||||||||

| Statistics | |||||||||||||||

| Weight(s) | Heavyweight | ||||||||||||||

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (191 cm)[7] | ||||||||||||||

| Reach | 78 in (198 cm)[7] | ||||||||||||||

| Stance | Orthodox | ||||||||||||||

| Boxing record | |||||||||||||||

| Total fights | 61 | ||||||||||||||

| Wins | 56 | ||||||||||||||

| Wins by KO | 37 | ||||||||||||||

| Losses | 5 | ||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||

| Website | muhammadali | ||||||||||||||

Muhammad Ali /ɑːˈliː/[8] (born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.;[9] January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. He is widely regarded as one of the most significant and celebrated sports figures of the 20th century. From early in his career, Ali was known as an inspiring, controversial, and polarizing figure both inside and outside the ring.[10][11]

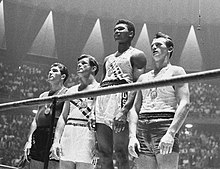

Cassius Clay was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky, and began training as an amateur boxer when he was 12 years old. At age 18, he won a gold medal in the light heavyweight division at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, after which he turned professional later that year. At age 22 in 1964, he won the WBA and WBC heavyweight titles from Sonny Liston in an upset. Clay then converted to Islam and changed his name from Cassius Clay, which he called his "slave name", to Muhammad Ali. He set an example of racial pride for African Americans and resistance to white domination during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement.[12][13]

In 1966, two years after winning the heavyweight title, Ali further antagonized the white establishment in the U.S. by refusing to be conscripted into the U.S. military, citing his religious beliefs and opposition to American involvement in the Vietnam War.[12][14] He was eventually arrested, found guilty of draft evasion charges and stripped of his boxing titles. He successfully appealed in the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned his conviction in 1971, by which time he had not fought for nearly four years—losing a period of peak performance as an athlete. Ali's actions as a conscientious objector to the war made him an icon for the larger counterculture generation.[15][16]

Ali is regarded as one of the leading heavyweight boxers of the 20th century. He remains the only three-time lineal heavyweight champion; he won the title in 1964, 1974 and 1978. Between February 25, 1964, and September 19, 1964, Ali reigned as the undisputed heavyweight champion. He is the only boxer to be named The Ring magazine Fighter of the Year six times. He was ranked as the greatest athlete of the 20th century by Sports Illustrated and the Sports Personality of the Century by the BBC. ESPN SportsCentury ranked him the 3rd greatest athlete of the 20th century. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he was involved in several historic boxing matches.[17] Notable among these were the first Liston fight; the "Fight of the Century", "Super Fight II" and the "Thrilla in Manila" versus his rival Joe Frazier; and "The Rumble in the Jungle" versus George Foreman.

At a time when most fighters let their managers do the talking, Ali thrived in—and indeed craved—the spotlight, where he was often provocative and outlandish.[18][19][20] He was known for trash talking, and often freestyled with rhyme schemes and spoken word poetry, both for his trash talking in boxing and as political poetry for his activism, anticipating elements of rap and hip hop music.[21][22][23] As a musician, Ali recorded two spoken word albums and a rhythm and blues song, and received two Grammy Award nominations.[23] As an actor, he performed in several films and a Broadway musical. Ali wrote two autobiographies, one during and one after his boxing career.

As a Muslim, Ali was initially affiliated with Elijah Muhammad's Nation of Islam (NOI) and advocated their black separatist ideology. He later disavowed the NOI, adhering to Sunni Islam and supporting racial integration, like his former mentor Malcolm X. After retiring from boxing in 1981, Ali devoted his life to religious and charitable work. In 1984, Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome, which his doctors attributed to boxing-related brain injuries. As the condition worsened, Ali made limited public appearances and was cared for by his family until his death on June 3, 2016 in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Early life and amateur career

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. (/ˈkæʃəs/) was born on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky.[24] He had a sister and four brothers.[25][26] He was named for his father, Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr., who himself was named in honor of the 19th-century Republican politician and staunch abolitionist, Cassius Marcellus Clay, also from the state of Kentucky. Clay's father's paternal grandparents were John Clay and Sallie Anne Clay; Clay's sister Eva claimed that Sallie was a native of Madagascar.[27] He was a descendant of slaves of the antebellum South, and was predominantly of African descent, with Irish[28] and English heritage.[29][30] His father painted billboards and signs,[24] and his mother, Odessa O'Grady Clay, was a domestic helper. Although Cassius Sr. was a Methodist, he allowed Odessa to bring up both Cassius Jr. and his younger brother Rudolph "Rudy" Clay (later renamed Rahman Ali) as Baptists.[31] Cassius Jr. attended Central High School in Louisville.[2]

Clay grew up amid racial segregation. His mother recalled one occasion where he was denied a drink of water at a store—"They wouldn't give him one because of his color. That really affected him."[12] He was also affected by the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, which led to young Clay and a friend taking out their frustration by vandalizing a local railyard.[32][33]

Clay was first directed toward boxing by Louisville police officer and boxing coach Joe E. Martin,[34] who encountered the 12-year-old fuming over a thief taking his bicycle. He told the officer he was going to "whup" the thief. The officer told him he had better learn how to box first.[35] Initially, Clay did not take up on Martin's offer, but after seeing amateur boxers on a local television boxing program called Tomorrow's Champions, Clay was interested in the prospects of fighting for fame, fortune, and glory.[citation needed] For the last four years of Clay's amateur career he was trained by boxing cutman Chuck Bodak.[36]

Clay made his amateur boxing debut in 1954 against local amateur boxer Ronnie O'Keefe. He won by split decision.[37] He went on to win six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles, two national Golden Gloves titles, an Amateur Athletic Union national title, and the Light Heavyweight gold medal in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome.[38] Clay's amateur record was 100 wins with five losses. Ali said in his 1975 autobiography that shortly after his return from the Rome Olympics, he threw his gold medal into the Ohio River after he and a friend were refused service at a "whites-only" restaurant and fought with a white gang. The story was later disputed and several of Ali's friends, including Bundini Brown and photographer Howard Bingham, denied it. Brown told Sports Illustrated writer Mark Kram, "Honkies sure bought into that one!" Thomas Hauser's biography of Ali stated that Ali was refused service at the diner but that he lost his medal a year after he won it.[39] Ali received a replacement medal at a basketball intermission during the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, where he lit the torch to start the games.

Professional boxing

Early career

Clay made his professional debut on October 29, 1960, winning a six-round decision over Tunney Hunsaker. From then until the end of 1963, Clay amassed a record of 19–0 with 15 wins by knockout. He defeated boxers including Tony Esperti, Jim Robinson, Donnie Fleeman, Alonzo Johnson, George Logan, Willi Besmanoff, Lamar Clark, Doug Jones and Henry Cooper. Clay also beat his former trainer and veteran boxer Archie Moore in a 1962 match.[40][41]

These early fights were not without trials. Clay was knocked down both by Sonny Banks and Cooper. In the Cooper fight, Clay was floored by a left hook at the end of round four and was saved by the bell. The fight with Doug Jones on March 13, 1963, was Clay's toughest fight during this stretch. The number-two and -three heavyweight contenders respectively, Clay and Jones fought on Jones' home turf at New York's Madison Square Garden. Jones staggered Clay in the first round, and the unanimous decision for Clay was greeted by boos and a rain of debris thrown into the ring (watching on closed-circuit TV, heavyweight champ Sonny Liston quipped that if he fought Clay he might get locked up for murder). The fight was later named "Fight of the Year" by Ring Magazine.[42]

In each of these fights, Clay vocally belittled his opponents and vaunted his abilities. He called Jones "an ugly little man" and Cooper a "bum". He was embarrassed to get in the ring with Alex Miteff. Madison Square Garden was "too small for me".[43] Clay's behavior provoked the ire of many boxing fans.[44] His provocative and outlandish behavior in the ring was inspired by professional wrestler "Gorgeous George" Wagner.[45] Ali stated in a 1969 interview with the Associated Press' Hubert Mizel that he met with Gorgeous George in Las Vegas in 1961 and that the wrestler inspired him to use wrestling jargon when he did interviews.[46]

After Clay left Moore's camp in 1960, partially due to Clay's refusing to do chores such as dish-washing and sweeping, he hired Angelo Dundee, whom he had met in February 1957 during Ali's amateur career,[47] to be his trainer. Around this time, Clay sought longtime idol Sugar Ray Robinson to be his manager, but was rebuffed.[48]

Heavyweight champion

By late 1963, Clay had become the top contender for Sonny Liston's title. The fight was set for February 25, 1964, in Miami Beach. Liston was an intimidating personality, a dominating fighter with a criminal past and ties to the mob. Based on Clay's uninspired performance against Jones and Cooper in his previous two fights, and Liston's destruction of former heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson in two first-round knock outs, Clay was a 7–1 underdog. Despite this, Clay taunted Liston during the pre-fight buildup, dubbing him "the big ugly bear". "Liston even smells like a bear", Clay said. "After I beat him I'm going to donate him to the zoo."[49] Clay turned the pre-fight weigh-in into a circus, shouting at Liston that "someone is going to die at ringside tonight". Clay's pulse rate was measured at 120, more than double his normal 54.[50] Many of those in attendance thought Clay's behavior stemmed from fear, and some commentators wondered if he would show up for the bout.

The outcome of the fight was a major upset. At the opening bell, Liston rushed at Clay, seemingly angry and looking for a quick knockout, but Clay's superior speed and mobility enabled him to elude Liston, making the champion miss and look awkward. At the end of the first round Clay opened up his attack and hit Liston repeatedly with jabs. Liston fought better in round two, but at the beginning of the third round Clay hit Liston with a combination that buckled his knees and opened a cut under his left eye. This was the first time Liston had ever been cut. At the end of round four, as Clay returned to his corner, he began experiencing blinding pain in his eyes and asked his trainer Angelo Dundee to cut off his gloves. Dundee refused. It has been speculated that the problem was due to ointment used to seal Liston's cuts, perhaps deliberately applied by his corner to his gloves.[50] Though unconfirmed, Bert Sugar claimed that two of Liston's opponents also complained about their eyes "burning".[51][52]

Despite Liston's attempts to knock out a blinded Clay, Clay was able to survive the fifth round until sweat and tears rinsed the irritation from his eyes. In the sixth, Clay dominated, hitting Liston repeatedly. Liston did not answer the bell for the seventh round, and Clay was declared the winner by TKO. Liston stated that the reason he quit was an injured shoulder. Following the win, a triumphant Clay rushed to the edge of the ring and, pointing to the ringside press, shouted: "Eat your words!" He added, "I am the greatest! I shook up the world. I'm the prettiest thing that ever lived."[53]

In winning this fight, Clay became at age 22 the youngest boxer to take the title from a reigning heavyweight champion, though Floyd Patterson was the youngest to win the heavyweight championship at 21, during an elimination bout following Rocky Marciano's retirement. Mike Tyson broke both records in 1986 when he defeated Trevor Berbick to win the heavyweight title at age 20.

Soon after the Liston fight, Clay changed his name to Cassius X, and then later to Muhammad Ali upon converting to Islam and affiliating with the Nation of Islam. Ali then faced a rematch with Liston scheduled for May 1965 in Lewiston, Maine. It had been scheduled for Boston the previous November, but was postponed for six months due to Ali's emergency surgery for a hernia three days before.[54] The fight was controversial. Midway through the first round, Liston was knocked down by a difficult-to-see blow the press dubbed a "phantom punch". Ali refused to retreat to a neutral corner, and referee Jersey Joe Walcott did not begin the count. Liston rose after he had been down about 20 seconds, and the fight momentarily continued. But a few seconds later Walcott stopped the match, declaring Ali the winner by knockout. The entire fight lasted less than two minutes.[55]

It has since been speculated that Liston dropped to the ground purposely. Proposed motivations include threats on his life from the Nation of Islam, that he had bet against himself and that he "took a dive" to pay off debts. Slow-motion replays show that Liston was jarred by a chopping right from Ali, although it is unclear whether the blow was a genuine knockout punch.[56]

Ali defended his title against former heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson on November 22, 1965. Before the match, Ali mocked Patterson, who was widely known to call him by his former name Cassius Clay, as an "Uncle Tom", calling him "The Rabbit". Although Ali clearly had the better of Patterson, who appeared injured during the fight, the match lasted 12 rounds before being called on a technical knockout. Patterson later said he had strained his sacroiliac. Ali was criticized in the sports media for appearing to have toyed with Patterson during the fight.[57]

Ali and then-WBA heavyweight champion boxer Ernie Terrell had agreed to meet for a bout in Chicago on March 29, 1966 (the WBA, one of two boxing associations, had stripped Ali of his title following his joining the Nation of Islam). But in February Ali was reclassified by the Louisville draft board as 1-A from 1-Y, and he indicated that he would refuse to serve, commenting to the press, "I ain't got nothing against no Viet Cong; no Viet Cong never called me nigger."[58] Amidst the media and public outcry over Ali's stance, the Illinois Athletic Commission refused to sanction the fight, citing technicalities.[59]

Instead, Ali traveled to Canada and Europe and won championship bouts against George Chuvalo, Henry Cooper, Brian London and Karl Mildenberger.

Ali returned to the United States to fight Cleveland Williams in the Houston Astrodome on November 14, 1966. The bout drew a record-breaking indoor crowd of 35,460 people. Williams had once been considered among the hardest punchers in the heavyweight division, but in 1964 he had been shot at point-blank range by a Texas policeman, resulting in the loss of one kidney and 10 feet (3.0 m) of his small intestine. Ali dominated Williams, winning a third-round technical knockout in what some consider the finest performance of his career.

Ali fought Terrell in Houston on February 6, 1967. Terrell was billed as Ali's toughest opponent since Liston—unbeaten in five years and having defeated many of the boxers Ali had faced. Terrell was big, strong and had a three-inch reach advantage over Ali. During the lead up to the bout, Terrell repeatedly called Ali "Clay", much to Ali's annoyance (Ali called Cassius Clay his "slave name"). The two almost came to blows over the name issue in a pre-fight interview with Howard Cosell. Ali seemed intent on humiliating Terrell. "I want to torture him", he said. "A clean knockout is too good for him."[60] The fight was close until the seventh round when Ali bloodied Terrell and almost knocked him out. In the eighth round, Ali taunted Terrell, hitting him with jabs and shouting between punches, "What's my name, Uncle Tom... what's my name?" Ali won a unanimous 15-round decision. Terrell claimed that early in the fight Ali deliberately thumbed him in the eye—forcing Terrell to fight half-blind—and then, in a clinch, rubbed the wounded eye against the ropes. Because of Ali's apparent intent to prolong the fight to inflict maximum punishment, critics described the bout as "one of the ugliest boxing fights". Tex Maule later wrote: "It was a wonderful demonstration of boxing skill and a barbarous display of cruelty." Ali denied the accusations of cruelty but, for Ali's critics, the fight provided more evidence of his arrogance.

After Ali's title defense against Zora Folley on March 22, he was stripped of his title due to his refusal to be drafted to army service.[24] His boxing license was also suspended by the state of New York. He was convicted of draft evasion on June 20 and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. He paid a bond and remained free while the verdict was being appealed.

Exile and comeback

In March 1966, Ali refused to be inducted into the armed forces. He was systematically denied a boxing license in every state and stripped of his passport. As a result, he did not fight from March 1967 to October 1970—from ages 25 to almost 29—as his case worked its way through the appeals process before his conviction was overturned in 1971. During this time of inactivity, as opposition to the Vietnam War began to grow and Ali's stance gained sympathy, he spoke at colleges across the nation, criticizing the Vietnam War and advocating African American pride and racial justice.

Fantasy fight against Rocky Marciano

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (July 2016) |

In 1968, Ali sued radio producer Murray Woroner for $1 million stating defamation of character,[61] after Woroner announced the broadcast of a series of "fantasy fight" specials created by computer simulation in which eight fantasy matches were placed through the use of an NCR 315 computer and approximately 250 boxing experts.[62] Known statistics, fighting styles, patterns and other factors determined the probable outcome. Ali had been placed in a fantasy fight with several boxers, and was unhappy regarding the outcome of his quarter final fantasy bout with Jim Jeffries in which he was predicted to have lost.[63]

Ali settled for a $10,000 payoff from Woroner in exchange for his participation in a filmed version of a fantasy fight with boxing legend Rocky Marciano,[64] who had retired 13 years earlier while World Heavyweight Champion and finished his career undefeated at 49–0.[65] Both men received cuts of the film's profits as part of their agreement to participate and commenced filming in 1969 in Miami, Florida.

The two fighters sparred between 70 and 75 1-minute rounds, which were later edited according to the findings of the computer. The final outcome was not revealed until the release of the film on January 20, 1970, where the fight was shown in over 1500 theaters over closed-circuit television in the United States, Canada and Europe. The film depicted that had the fight been actual, Marciano defeated Ali in the 13th round.

Marciano died in a plane crash three weeks after the completion of filming, which prevented any form of feedback regarding the fight,[66] while Ali criticized the film for being promoted as an actual fight, saying audiences were left angered by the depicted outcome, while also saying his predicted loss was a result of him not taking the simulation seriously, though he praised Marciano as a boxer and stated they left the filming on good terms.[62] As Ali was still banned from boxing, the filmmakers proceeded to destroy remaining prints of the film to prevent legal action, although one print survived, allowing for a DVD release in 2005, featuring an alternative ending in which Ali defeated Marciano in the 13th.[67] In 2006, the film was featured and used as inspiration for the film Rocky Balboa.

Legal vindication

On August 11, 1970, with his case still in appeal, Ali was granted a license to box by the City of Atlanta Athletic Commission, thanks to State Senator Leroy R. Johnson.[68] Ali's first return bout was against Jerry Quarry on October 26, resulting in a win after three rounds after Quarry was cut.

A month earlier, a victory in federal court forced the New York State Boxing Commission to reinstate Ali's license.[69] He fought Oscar Bonavena at Madison Square Garden in December, an uninspired performance that ended in a dramatic technical knockout of Bonavena in the 15th round. The win left Ali as a top contender against heavyweight champion Joe Frazier.

First fight against Joe Frazier

Ali and Frazier's first fight, held at the Garden on March 8, 1971, was nicknamed the "Fight of the Century", due to the tremendous excitement surrounding a bout between two undefeated fighters, each with a legitimate claim as heavyweight champions. Veteran boxing writer John Condon called it "the greatest event I've ever worked on in my life". The bout was broadcast to 35 foreign countries; promoters granted 760 press passes.[39]

Adding to the atmosphere were the considerable pre-fight theatrics and name calling. Ali portrayed Frazier as a "dumb tool of the white establishment". "Frazier is too ugly to be champ", Ali said. "Frazier is too dumb to be champ." Ali also frequently called Frazier an "Uncle Tom". Dave Wolf, who worked in Frazier's camp, recalled that, "Ali was saying 'the only people rooting for Joe Frazier are white people in suits, Alabama sheriffs, and members of the Ku Klux Klan. I'm fighting for the little man in the ghetto.' Joe was sitting there, smashing his fist into the palm of his hand, saying, 'What the fuck does he know about the ghetto?'"[39]

Ali began training at a farm near Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1971 and, finding the country setting to his liking, sought to develop a real training camp in the countryside. He found a five-acre site on a Pennsylvania country road in the village of Deer Lake, Pennsylvania. On this site, Ali carved out what was to become his training camp, the camp where he lived and trained for all the many fights he had from 1972 on to the end of his career in the 1980s.

The Monday night fight lived up to its billing. In a preview of their two other fights, a crouching, bobbing and weaving Frazier constantly pressured Ali, getting hit regularly by Ali jabs and combinations, but relentlessly attacking and scoring repeatedly, especially to Ali's body. The fight was even in the early rounds, but Ali was taking more punishment than ever in his career. On several occasions in the early rounds he played to the crowd and shook his head "no" after he was hit. In the later rounds—in what was the first appearance of the "rope-a-dope strategy"—Ali leaned against the ropes and absorbed punishment from Frazier, hoping to tire him. In the 11th round, Frazier connected with a left hook that wobbled Ali, but because it appeared that Ali might be clowning as he staggered backwards across the ring, Frazier hesitated to press his advantage, fearing an Ali counter-attack. In the final round, Frazier knocked Ali down with a vicious left hook, which referee Arthur Mercante said was as hard as a man can be hit. Ali was back on his feet in three seconds.[39] Nevertheless, Ali lost by unanimous decision, his first professional defeat.

Fights against Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry Quarry, Floyd Patterson, Bob Foster, and Ken Norton

In the same year basketball star Wilt Chamberlain challenged Ali, and a fight was scheduled for July 26. Although the seven foot two inch tall Chamberlain had formidable physical advantages over Ali, weighing 60 pounds more and able to reach 14 inches further, Ali was able to intimidate Chamberlain into calling off the bout by taunting him with calls of "Timber!" and "The tree will fall" during a shared interview. These statements of confidence unsettled his taller opponent to the point that he called off the bout.[70]

After the loss to Frazier, Ali fought Jerry Quarry, had a second bout with Floyd Patterson and faced Bob Foster in 1972, winning a total of six fights that year. In 1973, Ken Norton broke Ali's jaw while giving him the second loss of his career. After initially seeking retirement, Ali won a controversial decision against Norton in their second bout, leading to a rematch at Madison Square Garden on January 28, 1974, with Joe Frazier, who had recently lost his title to George Foreman.

Second fight against Joe Frazier

Ali was strong in the early rounds of the fight, and staggered Frazier in the second round. Referee Tony Perez mistakenly thought he heard the bell ending the round and stepped between the two fighters as Ali was pressing his attack, giving Frazier time to recover. However, Frazier came on in the middle rounds, snapping Ali's head in round seven and driving him to the ropes at the end of round eight. The last four rounds saw round-to-round shifts in momentum between the two fighters. Throughout most of the bout, however, Ali was able to circle away from Frazier's dangerous left hook and to tie Frazier up when he was cornered, the latter a tactic that Frazier's camp complained of bitterly. Judges awarded Ali a unanimous decision.

Heavyweight champion (second tenure)

The defeat of Frazier set the stage for a title fight against heavyweight champion George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire, on October 30, 1974—a bout nicknamed "The Rumble in the Jungle". Foreman was considered one of the hardest punchers in heavyweight history. In assessing the fight, analysts pointed out that Joe Frazier and Ken Norton—who had given Ali four tough battles and won two of them—had been both devastated by Foreman in second-round knockouts. Ali was 32 years old, and had clearly lost speed and reflexes since his twenties. Contrary to his later persona, Foreman was at the time a brooding and intimidating presence. Almost no one associated with the sport, not even Ali's long-time supporter Howard Cosell, gave the former champion a chance of winning.

As usual, Ali was confident and colorful before the fight. He told interviewer David Frost, "If you think the world was surprised when Nixon resigned, wait 'til I whup Foreman's behind!"[71] He told the press, "I've done something new for this fight. I done wrestled with an alligator, I done tussled with a whale; handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail; only last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalized a brick; I'm so mean I make medicine sick."[72] Ali was wildly popular in Zaire, with crowds chanting "Ali, bomaye" ("Ali, kill him") wherever he went.

Ali opened the fight moving and scoring with right crosses to Foreman's head. Then, beginning in the second round—and to the consternation of his corner—Ali retreated to the ropes and invited Foreman to hit him while covering up, clinching and counter-punching, all while verbally taunting Foreman. The move, which would later become known as the "Rope-a-dope", so violated conventional boxing wisdom—letting one of the hardest hitters in boxing strike at will—that at ringside writer George Plimpton thought the fight had to be fixed.[39] Foreman, increasingly angered, threw punches that were deflected and did not land squarely. Midway through the fight, as Foreman began tiring, Ali countered more frequently and effectively with punches and flurries, which electrified the pro-Ali crowd. In the eighth round, Ali dropped an exhausted Foreman with a combination at center ring; Foreman failed to make the count. Against the odds, and amidst pandemonium in the ring, Ali had regained the title by knockout. In reflecting on the fight, George Foreman later said: "I thought Ali was just one more knockout victim until, about the seventh round, I hit him hard to the jaw and he held me and whispered in my ear: 'That all you got, George?' I realized that this ain't what I thought it was."[73]

Ali's next opponents included Chuck Wepner, Ron Lyle, and Joe Bugner. Wepner, a journeyman known as "The Bayonne Bleeder", stunned Ali with a knockdown in the ninth round; Ali would later say he tripped on Wepner's foot. It was a bout that would inspire Sylvester Stallone to create the acclaimed film, Rocky.

Ali then agreed to a third match with Joe Frazier in Manila. The bout, known as the "Thrilla in Manila", was held on October 1, 1975,[24] in temperatures approaching 100 °F (38 °C). In the first rounds, Ali was aggressive, moving and exchanging blows with Frazier. However, Ali soon appeared to tire and adopted the "rope-a-dope" strategy, frequently resorting to clinches. During this part of the bout Ali did some effective counter-punching, but for the most part absorbed punishment from a relentlessly attacking Frazier. In the 12th round, Frazier began to tire, and Ali scored several sharp blows that closed Frazier's left eye and opened a cut over his right eye. With Frazier's vision now diminished, Ali dominated the 13th and 14th rounds, at times conducting what boxing historian Mike Silver called "target practice" on Frazier's head. The fight was stopped when Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, refused to allow Frazier to answer the bell for the 15th and final round, despite Frazier's protests. Frazier's eyes were both swollen shut. Ali, in his corner, winner by TKO, slumped on his stool, clearly spent.

An ailing Ali said afterwards that the fight "was the closest thing to dying that I know", and, when later asked if he had viewed the fight on videotape, reportedly said, "Why would I want to go back and see Hell?" After the fight he cited Frazier as "the greatest fighter of all times next to me".

Later career

Following the Manila bout, Ali fought Jean-Pierre Coopman, Jimmy Young, and Richard Dunn, winning the last by knockout.

On June 1, 1976, Ali removed his shirt and jacket and confronted professional wrestler Gorilla Monsoon in the ring after his match at a World Wide Wrestling Federation show in Philadelphia Arena. After dodging a few punches, Monsoon put Ali in an airplane spin and dumped him to the mat. Ali stumbled to the corner, where his associate Butch Lewis convinced him to walk away.[74]

On June 26, 1976, Ali participated in an exhibition bout in Tokyo against Japanese professional wrestler and martial artist Antonio Inoki.[75] Though the fight was a publicity stunt, Inoki's kicks caused bruises, two blood clots and an infection in Ali's legs.[75] The match was ultimately declared a draw.[75] After Ali's death, The New York Times declared it his least memorable fight.[76] In hindsight, CBS Sports said the attention the mixed-style bout received "foretold the arrival of standardized MMA years later."[77]

Ali fought Ken Norton for the third time at Yankee Stadium in September 1976, which he won in a heavily contested decision, which was loudly booed by the audience. Afterwards, he announced he was retiring from boxing to practice his faith, having converted to Sunni Islam after falling out with the Nation of Islam the previous year.[78]

After returning to beat Alfredo Evangelista in May 1977, Ali struggled in his next fight against Earnie Shavers that September, getting pummeled a few times by punches to the head. Ali won the fight by another unanimous decision, but the bout caused his longtime doctor Ferdie Pacheco to quit after he was rebuffed for telling Ali he should retire. Pacheco was quoted as saying, "the New York State Athletic Commission gave me a report that showed Ali's kidneys were falling apart. I wrote to Angelo Dundee, Ali's trainer, his wife and Ali himself. I got nothing back in response. That's when I decided enough is enough."[39]

In February 1978, Ali faced Leon Spinks at the Hilton Hotel in Las Vegas. At the time, Spinks had only seven professional fights to his credit, and had recently fought a draw with journeyman Scott LeDoux. Ali sparred less than two dozen rounds in preparation for the fight, and was seriously out of shape by the opening bell. He lost the title by split decision. A rematch followed shortly thereafter in New Orleans, which broke attendance records. Ali won a unanimous decision in an uninspiring fight, making him the first heavyweight champion to win the belt three times.[79]

Following this win, on July 27, 1979, Ali announced his retirement from boxing. His retirement was short-lived, however; Ali announced his comeback to face Larry Holmes for the WBC belt in an attempt to win the heavyweight championship an unprecedented fourth time. The fight was largely motivated by Ali's need for money. Boxing writer Richie Giachetti said, "Larry didn't want to fight Ali. He knew Ali had nothing left; he knew it would be a horror."

It was around this time that Ali started struggling with vocal stutters and trembling hands.[80] The Nevada Athletic Commission (NAC) ordered that he undergo a complete physical in Las Vegas before being allowed to fight again. Ali chose instead to check into the Mayo Clinic, who declared him fit to fight. Their opinion was accepted by the NAC on July 31, 1980, paving the way for Ali's return to the ring.[81]

The fight took place on October 2, 1980, in Las Vegas Valley, with Holmes easily dominating Ali, who was weakened from thyroid medication he had taken to lose weight. Giachetti called the fight "awful ... the worst sports event I ever had to cover". Actor Sylvester Stallone at ringside said it was like watching an autopsy on a man who is still alive.[39] Ali's trainer Angelo Dundee finally stopped the fight in the eleventh round, the only fight Ali lost by knockout. The Holmes fight is said to have contributed to Ali's Parkinson's syndrome.[82] Despite pleas to definitively retire, Ali fought one last time on December 11, 1981, in Nassau, Bahamas, against Trevor Berbick, losing a ten-round decision.[83][84][85]

Personal life

Marriages and children

Ali was married four times and had seven daughters and two sons. Ali was introduced to cocktail waitress Sonji Roi by Herbert Muhammad and asked her to marry him after their first date. They were wed approximately one month later on August 14, 1964.[86] They quarrelled over Sonji's refusal to adhere to strict Islamic dress and behavior codes, and her questioning of Elijah Muhammad's teachings. According to Ali, "She wouldn't do what she was supposed to do. She wore lipstick; she went into bars; she dressed in clothes that were revealing and didn't look right."[87] The marriage was childless and they divorced on January 10, 1966. Just before the divorce was finalized, Ali sent Sonji a note: "You traded heaven for hell, baby."[88]

On August 17, 1967, Ali married Belinda Boyd. After the wedding, she, like Ali, converted to Islam. She changed her name to Khalilah Ali, though she was still called Belinda by old friends and family. They had four children: Maryum "May May" (born 1968), twins Jamillah and Rasheda (born 1970; Rasheda married Robert Walsh and has a son Biaggio Ali, born in 1998), and Muhammad Ali Jr. (born 1972).[89] Maryum has a career as an author and rapper.[90]

Ali was a resident of Cherry Hill, New Jersey, in the early 1970s.[91] In 1974, Ali began a relationship with the 16-year-old Wanda Bolton (who subsequently changed her name to Aaisha Ali) with whom he fathered another daughter, Khaliah (born 1974). While still married to Belinda, Ali married Aaisha in an Islamic ceremony that was not legally recognized. According to Khaliah, she and her mother lived at Ali's Deer Lake training camp alongside Belinda and her children.[92] In January 1985 Aaisha sued Ali for unpaid palimony. The case was settled when Ali agreed to set up a $200,000 trust fund for Khaliah.[93] In 2001 Khaliah was quoted as saying she believed her father viewed her as "a mistake".[92] He also had another daughter, Miya, from an extramarital relationship.[89][94]

In 1975, Ali began an affair with Veronica Porché, an actress and model. While Ali was in the Philippines for the "Thrilla in Manila" against Joe Frazier, Belinda was enraged when she saw Ali on television introducing Veronica to Ferdinand Marcos. She flew out to Manila to confront Ali and scratched his face during their argument. Belinda later said that marriage to Ali was a "rollercoaster ride – it had its ups and its downs but it was fun". Referring to his infidelities, she said: "Tiger Woods and Arnold Schwarzenegger didn't have nothing on Muhammad Ali". She believes he had "many more" illegitimate children.[95]

By the summer of 1977, his second marriage was over and he had married Porché.[96] At the time of their marriage, they had a baby girl, Hana, and Veronica was pregnant with their second child. Their second daughter, Laila Ali, was born in December 1977. By 1986, Ali and Porché were divorced.[96]

On November 19, 1986, Ali married Yolanda ("Lonnie") Williams. They had been friends since 1964 in Louisville. Together they adopted a son, Asaad Amin, when Amin was five months old.

Kiiursti Mensah-Ali claims to be Ali's biological daughter with Barbara Mensah, with whom he had a 20-year relationship,[89][97][98][99][100] citing photographs and a paternity test conducted in 1988. She said he accepted responsibility and took care of her, but all contacts with him were cut off after he married his fourth wife Lonnie. Kiiursti claims to have a relationship with his other children. After his death she again made passionate appeals to be allowed to mourn at his funeral.[101][102][103]

In 2010, Osmon Williams came forward claiming to be Ali's biological son.[104] His mother Temica Williams (also known as Rebecca Holloway) had sued Ali for sexual assault in 1981, claiming that she had started a sexual relationship with him when she was 12, and that her son Osmon (born 1977) was fathered by Ali. The case went on until 1986 and was eventually thrown out as her allegations were deemed to be barred by the statute of limitations.[105]

Ali then lived in Scottsdale, Arizona, with Lonnie.[106] In January 2007 it was reported that they had put their home in Berrien Springs, Michigan, up for sale and had purchased a home in eastern Jefferson County, Kentucky for $1,875,000.[107] Lonnie converted to Islam from Catholicism in her late twenties.[108]

Ali's daughter Laila became a boxer in 1999,[109] despite her father's earlier comments against female boxing in 1978: "Women are not made to be hit in the breast, and face like that... the body's not made to be punched right here [patting his chest]. Get hit in the breast... hard... and all that."[110]

Ali's daughter Hana is married to UFC middleweight fighter Kevin Casey.[111]

In 2016, Ali's daughter Maryum appeared as a volunteer inmate in the reality show 60 Days In.

Religion and beliefs

Affiliation with the Nation of Islam

Ali said that he first heard of the Nation of Islam when he was fighting in the Golden Gloves tournament in Chicago in 1959, and attended his first Nation of Islam meeting in 1961. He continued to attend meetings, although keeping his involvement hidden from the public. In 1962, Clay met Malcolm X, who soon became his spiritual and political mentor.[112] By the time of the first Liston fight, Nation of Islam members, including Malcolm X, were visible in his entourage. This led to a story in The Miami Herald just before the fight disclosing that Clay had joined the Nation of Islam, which nearly caused the bout to be canceled.

In fact, Clay was initially refused entry to the Nation of Islam (often called the Black Muslims at the time) due to his boxing career. However, after he won the championship from Liston in 1964, the Nation of Islam was more receptive and agreed to publicize his membership.[112] Shortly afterwards, Elijah Muhammad recorded a statement that Clay would be renamed Muhammad (one who is worthy of praise) Ali (Ali is the most important figure after Muhammad in Shia view and fourth rightly guided caliph in Sunni view). Around that time Ali moved to the south side of Chicago and lived in a series of houses, always near the Nation of Islam's Mosque Maryam or Elijah Muhammad's residence. He stayed in Chicago for about 12 years.[113]

Only a few journalists (most notably Howard Cosell) accepted the new name at that time. Ali later announced: "Cassius Clay is my slave name."[114] Not afraid to antagonize the white establishment, Ali stated, "I am America. I am the part you won't recognize. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me."[115] Ali's friendship with Malcolm X ended as Malcolm split with the Nation of Islam a couple of weeks after Ali joined, and Ali remained with the Nation of Islam.[116][117] Ali later said that turning his back on Malcolm was one of the mistakes he regretted most in his life.[118]

Aligning himself with the Nation of Islam, its leader Elijah Muhammad, and a narrative that labeled the white race as the perpetrator of genocide against African Americans made Ali a target of public condemnation. The Nation of Islam was widely viewed by whites and even some African Americans as a black separatist "hate religion" with a propensity toward violence; Ali had few qualms about using his influential voice to speak Nation of Islam doctrine.[119] In a press conference articulating his opposition to the Vietnam War, Ali stated, "My enemy is the white people, not Viet Cong or Chinese or Japanese."[120] In relation to integration, he said: "We who follow the teachings of Elijah Muhammad don't want to be forced to integrate. Integration is wrong. We don't want to live with the white man; that's all".[121][122]

Writer Jerry Izenberg once noted that, "the Nation became Ali's family and Elijah Muhammad became his father. But there is an irony to the fact that while the Nation branded white people as devils, Ali had more white colleagues than most African American people did at that time in America, and continued to have them throughout his career."[39]

Later beliefs

Ali converted from the Nation of Islam sect to mainstream Sunni Islam in 1975. In a 2004 autobiography, written with daughter Hana Yasmeen Ali, he attributed his conversion to the shift toward mainstream Islam made by Warith Deen Muhammad after he gained control of the Nation of Islam upon the death of Elijah Muhammad in 1975.

He had gone on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in 1972, which inspired Ali in a similar manner to Malcolm X, meeting people of different colors from all over the world giving him a different outlook and greater spiritual awareness.[123] In 1977, he said that, after he retired, he would dedicate the rest of his life to getting "ready to meet God" by helping people, charitable causes, uniting people and helping to make peace.[124] He went on another Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in 1988.[125] In his later life, he had taken an interest in Sufism, which he referenced in his autobiography, The Soul of a Butterfly.[118]

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, he stated that "Islam is a religion of peace" and "does not promote terrorism or killing people", and that he is "angry that the world sees a certain group of Islam followers who caused this destruction, but they are not real Muslims. They are racist fanatics who call themselves Muslims". In December 2015, he stated that "True Muslims know that the ruthless violence of so-called Islamic jihadists goes against the very tenets of our religion", that "We as Muslims have to stand up to those who use Islam to advance their own personal agenda", and that "political leaders should use their position to bring understanding about the religion of Islam, and clarify that these misguided murderers have perverted people's views on what Islam really is."[126]

Vietnam War and resistance to the draft

"My enemy is the white people, not Viet Cong or Chinese or Japanese. You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice. You my opposer when I want equality. You won't even stand up for me in America for my religious beliefs — and you want me to go somewhere and fight, but you won't even stand up for me here at home?"

—Muhammad Ali to a crowd of college students during his exile[120]

Ali registered for conscription in the United States military on his 18th birthday and was listed as 1-A in 1962.[127] In 1964, he was reclassified as Class 1-Y (fit for service only in times of national emergency) after he failed the U.S. Armed Forces qualifying test because his writing and spelling skills were sub-standard.[128] (He was quoted as saying, "I said I was the greatest, not the smartest!")[127][129] By early 1966, the army lowered its standards to permit soldiers above the 15th percentile and Ali was again classified as 1-A.[24][127][129] This classification meant he was now eligible for the draft and induction into the U.S. Army at a time when the U.S. was involved in the Vietnam War, a war which put him further at odds with the white establishment.[14]

When notified of this status, Ali declared that he would refuse to serve in the army and publicly considered himself a conscientious objector.[24] Ali stated: "War is against the teachings of the Qur'an. I'm not trying to dodge the draft. We are not supposed to take part in no wars unless declared by Allah or The Messenger. We don't take part in Christian wars or wars of any unbelievers." He stated: "Man, I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong."[130] Ali elaborated: "Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?"[131]

Appearing for his scheduled induction into the U.S. Armed Forces on April 28, 1967, in Houston, Ali refused three times to step forward at the call of his name. An officer warned him he was committing a felony punishable by five years in prison and a fine of $10,000. Once more, Ali refused to budge when his name was called. As a result, he was arrested. On the same day the New York State Athletic Commission suspended his boxing license and stripped him of his title. Other boxing commissions followed suit. Ali would not be able to obtain a license to box in any state for over three years.[132][page needed]

At the trial on June 20, 1967, after only 21 minutes of deliberation, the jury found Ali guilty.[24] After a Court of Appeals upheld the conviction, the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court.[citation needed]

In the years between the Appellate Court decision and the Supreme Court verdict, Ali remained free. As public opinion began turning against the war and the Civil Rights Movement continued to gather momentum, Ali became a popular speaker at colleges and universities across the country, rare if not unprecedented for a boxer. At Howard University, for example, he gave his popular "Black Is Best" speech to 4,000 cheering students and community intellectuals, after he was invited to speak by sociology professor Nathan Hare on behalf of the Black Power Committee, a student protest group.[133]

On June 28, 1971, the Supreme Court of the United States in Clay v. United States overturned Ali's conviction by a unanimous 8–0 decision (Justice Thurgood Marshall recused himself, as he had been the U.S. Solicitor General at the time of Ali's conviction).[134] The decision was not based on, nor did it address, the merits of Ali's claims per se; rather, the Court held that since the Appeal Board gave no reason for the denial of a conscientious objector exemption to Ali, and that it was therefore impossible to determine which of the three basic tests for conscientious objector status offered in the Justice Department's brief that the Appeals Board relied on, Ali's conviction must be reversed.[135]

Impact of Ali's draft refusal

Ali's example inspired countless black Americans and others. The New York Times columnist William Rhoden wrote, "Ali's actions changed my standard of what constituted an athlete's greatness. Possessing a killer jump shot or the ability to stop on a dime was no longer enough. What were you doing for the liberation of your people? What were you doing to help your country live up to the covenant of its founding principles?"[16]

Recalling Ali's anti-war position, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar said: "I remember the teachers at my high school didn't like Ali because he was so anti-establishment and he kind of thumbed his nose at authority and got away with it. The fact that he was proud to be a black man and that he had so much talent ... made some people think that he was dangerous. But for those very reasons I enjoyed him."[136]

Civil rights figures came to believe that Ali had an energizing effect on the freedom movement as a whole. Al Sharpton spoke of his bravery at a time when there was still widespread support for the Vietnam War. "For the heavyweight champion of the world, who had achieved the highest level of athletic celebrity, to put all of that on the line – the money, the ability to get endorsements – to sacrifice all of that for a cause, gave a whole sense of legitimacy to the movement and the causes with young people that nothing else could have done. Even those who were assassinated, certainly lost their lives, but they didn't voluntarily do that. He knew he was going to jail and did it anyway. That's another level of leadership and sacrifice."[137]

In speaking of the cost on Ali's career of his refusal to be drafted, his trainer Angelo Dundee said, "One thing must be taken into account when talking about Ali: He was robbed of his best years, his prime years."[138]

Ali's resistance to the draft was covered in the 2013 documentary The Trials of Muhammad Ali.[139]

NSA and FBI monitoring of Ali's communications

In a secret operation code-named "Minaret", the National Security Agency (NSA) intercepted the communications of leading Americans, including Ali, Senators Frank Church and Howard Baker, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., prominent U.S. journalists, and others who criticized the U.S. war in Vietnam.[140][141] A review by the NSA of the Minaret program concluded that it was "disreputable if not outright illegal".[141]

In 1971, his Fight of the Century with Frazier provided cover for an activist group, the Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI, to successfully pull off a burglary at an FBI office in Pennsylvania, which exposed the COINTELPRO operations that included illegal spying on activists involved with the civil rights and anti-war movements. One of the COINTELPRO targets was Ali, which included the FBI gaining access to his records as far back as elementary school; one such record mentioned him loving art as a child.[142]

Later years

Ali began visiting Africa starting in 1964, when he visited Ghana.[143] In 1974, he visited a Palestinian refugee camp in Southern Lebanon, where Ali declared "support for the Palestinian struggle to liberate their homeland".[144][145] In 1978, following his defeat to Spinks and before winning the rematch, Ali visited Bangladesh and received honorary citizenship there.[146] The same year, he participated in The Longest Walk, a protest march in the United States in support of Native American rights, along with singer Stevie Wonder and actor Marlon Brando.[147]

In 1980, he visited Kenya and successfully convinced the government to boycott the Moscow Olympics (in response to the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan).[148] On January 19, 1981, in Los Angeles, Ali talked a suicidal man down from jumping off a ninth-floor ledge, an event that made national news.[149][150]

Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome in 1984, a disease that sometimes results from head trauma from activities such as boxing.[151][152][153] Ali still remained active during this time, however, later participating as a guest referee at WrestleMania I.[154][155]

In 1984, Ali announced his support for the re-election of United States President Ronald Reagan. When asked to elaborate on his endorsement of Reagan, Ali told reporters, "He's keeping God in schools and that's enough."[156] In 1985, he visited Israel to request the release of Muslim prisoners at Atlit detainee camp, which Israel declined.[157]

Around 1987, the California Bicentennial Foundation for the U.S. Constitution selected Ali to personify the vitality of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. Ali rode on a float at the following year's Tournament of Roses Parade, launching the U.S. Constitution's 200th birthday commemoration.[citation needed] In 1988, during the First Intifada, Ali participated in a Chicago rally in support of Palestine.[145] The same year, he visited Sudan to raise awareness about the plight of famine victims.[158] In 1989, he participated in an Indian charity event with the Muslim Educational Society in Kozhikode, Kerala, along with Bollywood actor Dilip Kumar.[125]

In 1990, Ali traveled to Iraq prior to the Gulf War, and met with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages. Ali successfully secured the release of the hostages, in exchange for promising Hussein that he'd bring America "an honest account" of Iraq. Despite rescuing hostages, he received criticism from President George H. W. Bush, diplomat Joseph C. Wilson, and The New York Times.[159][160] Ali published an oral history, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times by Thomas Hauser, in 1991. In 1996, he had the honor of lighting the flame at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia.

Ali's bout with Parkinson's led to a gradual decline in his health, though he was still active into the early years of the millennium, promoting his own biopic, Ali, in 2001. Ali also contributed an on-camera segment to the America: A Tribute to Heroes benefit concert.[citation needed]

In 1998, Ali began working with actor Michael J Fox, who has Parkinson's disease, to raise awareness and fund research for a cure. They made a joint appearance before Congress to push the case in 2002. In 2000, Ali worked with the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Disease to raise awareness and encourage donations for research.[161]

On November 17, 2002, Ali went to Afghanistan as the "U.N. Messenger of Peace".[162] He was in Kabul for a three-day goodwill mission as a special guest of the UN.[163]

On September 1, 2009, Ali visited Ennis, County Clare, Ireland, the home of his great-grandfather, Abe Grady, who emigrated to the U.S. in the 1860s, eventually settling in Kentucky.[164] A crowd of 10,000 turned out for a civic reception, where Ali was made the first Honorary Freeman of Ennis.[165]

On July 27, 2012, Ali was a titular bearer of the Olympic Flag during the opening ceremonies of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. He was helped to his feet by his wife Lonnie to stand before the flag due to his Parkinson's rendering him unable to carry it into the stadium.[166] In 2014, Ali tweeted in support of Trayvon Martin and the Black Lives Matter movement.[167]

Illness and death

In February 2013, Ali's brother Rahman Ali said Muhammad could no longer speak and could be dead within days.[168] Ali's daughter May May Ali responded to the rumors, stating that she had talked to him on the phone the morning of February 3 and he was fine.[169]

On December 20, 2014, Ali was hospitalized for a mild case of pneumonia.[170] Ali was once again hospitalized on January 15, 2015, for a urinary tract infection after being found unresponsive at a guest house in Scottsdale, Arizona.[171][172] He was released the next day.[173]

Ali was hospitalized in Scottsdale on June 2, 2016, with a respiratory illness. Though his condition was initially described as "fair", it worsened and he died the following day, at the age of 74, from septic shock.[174][175][176][177] Following Ali's death, he was the number one trending topic on Twitter for over 12 hours and on Facebook was trending topic number one for several days. ESPN played four hours of non-stop commercial-free coverage of Ali. BET played their documentary Muhammad Ali: Made In Miami. News networks such as CNN, BBC, Fox News, and ABC News also covered him extensively.

Tributes

Ali was mourned globally, and a family spokesman said the family "certainly believes that Muhammad was a citizen of the world … and they know that the world grieves with him."[178] Politicians such as Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, David Cameron and more paid tribute to Ali. Ali also received numerous tributes from the world of sports including Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, Floyd Mayweather, Mike Tyson, the Miami Marlins, LeBron James, Steph Curry and more. Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer stated, "Muhammad Ali belongs to the world. But he only has one hometown."[178]

Memorial

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Ali's funeral was preplanned by himself and others beginning years prior to his actual death.[180] The services began in Louisville on June 9, 2016, with an Islamic Janazah prayer service at Freedom Hall on the grounds of the Kentucky Exposition Center. A funeral procession went through the streets of Louisville on June 10, 2016, ending at Cave Hill Cemetery, where a private interment ceremony occurred. Ali's grave is marked with a simple granite marker that bears only his name. A public memorial service for Ali at downtown Louisville's KFC Yum! Center was held in the afternoon of June 10.[181][182][183] The pallbearers included Will Smith, Lennox Lewis and Mike Tyson, with honorary pallbearers including George Chuvalo, Larry Holmes and George Foreman.[184]

Boxing style

Ali had a highly unorthodox boxing style for a heavyweight, epitomized by his catchphrase "float like a butterfly, sting like a bee". Never an overpowering puncher, Ali relied early in his career on his superior hand speed, superb reflexes and constant movement, dancing and circling opponents for most of the fight, holding his hands low and lashing out with a quick, cutting left jab that he threw from unpredictable angles. His footwork was so strong that it was extremely difficult for opponents to cut down the ring and corner Ali against the ropes. He was also able to quickly dodge punches with his head movement and footwork.[citation needed]

One of Ali's greatest tricks was to make opponents overcommit by pulling straight backward from punches. Disciplined, world-class boxers chased Ali and threw themselves off balance attempting to hit him because he seemed to be an open target, only missing and leaving themselves exposed to Ali's counter punches, usually a chopping right.[185] Slow motion replays show that this was precisely the way Sonny Liston was hit and apparently knocked out by Ali in their second fight.[186] Ali often flaunted his movement by dancing the "Ali Shuffle", a sort of center-ring jig.[187] Ali's early style was so unusual that he was initially discounted because he reminded boxing writers of a lightweight, and it was assumed he would be vulnerable to big hitters like Sonny Liston.[citation needed]

Using a synchronizer, Jimmy Jacobs, who co-managed Mike Tyson, measured young Ali's punching speed versus Sugar Ray Robinson, a welter/middleweight, often considered the best pound-for-pound fighter in history. Ali was 25% faster than Robinson, even though Ali was 45–50 pounds heavier.[188] Ali's punches produced approximately 1,000 pounds of force.[189] "No matter what his opponents heard about him, they didn't realize how fast he was until they got in the ring with him", Jacobs said.[190] The effect of Ali's punches was cumulative. Charlie Powell, who fought Ali early in Ali's career and was knocked out in the third round, said: "When he first hit me I said to myself, 'I can take two of these to get one in myself.' But in a little while I found myself getting dizzier and dizzier every time he hit me. He throws punches so easily that you don't realize how much they hurt you until it's too late."[43]

Commenting on fighting the young Ali, George Chuvalo said: "He was just so damn fast. When he was young, he moved his legs and hands at the same time. He threw his punches when he was in motion. He'd be out of punching range, and as he moved into range he'd already begun to throw the punch. So if you waited until he got into range to punch back, he beat you every time."[39]

Floyd Patterson said, "It's very hard to hit a moving target, and (Ali) moved all the time, with such grace, three minutes of every round for fifteen rounds. He never stopped. It was extraordinary."[39]

Darrell Foster, who trained Will Smith for the movie Ali, said: "Ali's signature punches were the left jab and the overhand right. But there were at least six different ways Ali used to jab. One was a jab that Ali called the 'snake lick', like cobra striking that comes from the floor almost, really low down. Then there was Ali's rapid-fire jab—three to five jabs in succession rapidly fired at his opponents' eyes to create a blur in his face so he wouldn't be able to see the right hand coming behind it."[191]

In the opinion of many, Ali became a different fighter after the 3½-year layoff. Ferdie Pacheco, Ali's corner physician, noted that he had lost his ability to move and dance as before.[39] This forced Ali to become more stationary and exchange punches more frequently, exposing him to more punishment while indirectly revealing his tremendous ability to take a punch. This physical change led in part to the "rope-a-dope" strategy, where Ali would lie back on the ropes, cover up to protect himself and conserve energy, and tempt opponents to punch themselves out. Ali often taunted opponents in the process and lashed back with sudden, unexpected combinations. The strategy was dramatically successful in the George Foreman fight, but less so in the first Joe Frazier bout when it was introduced.[citation needed]

Of his later career, Arthur Mercante said: "Ali knew all the tricks. He was the best fighter I ever saw in terms of clinching. Not only did he use it to rest, but he was big and strong and knew how to lean on opponents and push and shove and pull to tire them out. Ali was so smart. Most guys are just in there fighting, but Ali had a sense of everything that was happening, almost as though he was sitting at ringside analyzing the fight while he fought it."[39]

"Talking trash"

Ali regularly taunted and baited his opponents—including Liston, Frazier, and Foreman—before the fight and often during the bout itself. He said Frazier was "too dumb to be champion", that he would whip Liston "like his Daddy did", that Terrell was an "Uncle Tom" for refusing to call Ali by his name and continuing to call him Cassius Clay, and that Patterson was a "rabbit". In speaking of how Ali stoked Liston's anger and overconfidence before their first fight, one writer commented that "the most brilliant fight strategy in boxing history was devised by a teenager who had graduated 376 in a class of 391."[188]

Ali typically portrayed himself as the "people's champion" and his opponent as a tool of the (white) establishment (despite the fact that his entourage often had more white faces than his opponents'). During the early part of his career, he built a reputation for predicting rounds in which he would finish opponents, often vowing to crawl across the ring or to leave the country if he lost the bout.[24] Ali adopted the latter practice from "Gorgeous" George Wagner, a professional wrestling champion who drew thousands of fans to his matches as "the man you love to hate".[24] When Ali was 19, Wagner, who was in town to wrestle Freddie Blassie and had crossed paths with Clay,[46] told the boxer before a bout with Duke Sabedong in Las Vegas,[46] "A lot of people will pay to see someone shut your mouth. So keep on bragging, keep on sassing and always be outrageous."[45]

ESPN columnist Ralph Wiley called Ali "The King of Trash Talk".[192] In 2013, The Guardian said Ali exemplified boxing's "golden age of trash talking".[193] The Bleacher Report called Clay's description of Sonny Liston smelling like a bear and his vow to donate him to a zoo after he beat him the greatest trash talk line in sports history.[194]

Legacy

Muhammad Ali defeated every top heavyweight in his era, which has been called the golden age of heavyweight boxing. Ali was named "Fighter of the Year" by Ring Magazine more times than any other fighter, and was involved in more Ring Magazine "Fight of the Year" bouts than any other fighter. He was an inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and held wins over seven other Hall of Fame inductees. He was one of only three boxers to be named "Sportsman of the Year" by Sports Illustrated.

In 1978, three years before Ali's permanent retirement, the Louisville Board of Aldermen in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, voted 6–5 to rename Walnut Street to Muhammad Ali Boulevard. This was controversial at the time, as within a week 12 of the 70 street signs were stolen. Earlier that year, a committee of the Jefferson County Public Schools (Kentucky) considered renaming Ali's alma mater, Central High School, in his honor, but the motion failed to pass. In time, Muhammad Ali Boulevard—and Ali himself—came to be well accepted in his hometown.[195]

In 1993, the Associated Press reported that Ali was tied with Babe Ruth as the most recognized athlete, out of over 800 dead or living athletes, in America. The study found that over 97% of Americans over 12 years of age identified both Ali and Ruth.[196] He was the recipient of the 1997 Arthur Ashe Courage Award.

In 1999, Time magazine named Ali one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century.[197] He was crowned Sportsman of the Century by Sports Illustrated.[198] Named Sports Personality of the Century in a BBC poll, he received more votes than the other contenders (which included Pelé, Jesse Owens and Jack Nicklaus) combined.[199] On September 13, 1999, Ali was named "Kentucky Athlete of the Century" by the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame in ceremonies at the Galt House East.[200]

On January 8, 2001, Muhammad Ali was presented with the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Bill Clinton.[201] In November 2005, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush,[202][203] followed by the Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold of the UN Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin for his work with the U.S. civil rights movement and the United Nations (December 17, 2005).[204]

On November 19, 2005 (Ali's 19th wedding anniversary), the $60 million non-profit Muhammad Ali Center opened in downtown Louisville. In addition to displaying his boxing memorabilia, the center focuses on core themes of peace, social responsibility, respect, and personal growth. On June 5, 2007, he received an honorary doctorate of humanities at Princeton University's 260th graduation ceremony.[205]

Ali Mall, located in Araneta Center, Quezon City, Philippines, is named after him. Construction of the mall, the first of its kind in the Philippines, began shortly after Ali's victory in a match with Joe Frazier in nearby Araneta Coliseum in 1975. The mall opened in 1976 with Ali attending its opening.[206]

The 1976 Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki fight played a role in the history of mixed martial arts, particularly in Japan. The match inspired Inoki's students Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki to found Pancrase in 1993, which in turn inspired the foundation of Pride Fighting Championships in 1997. Pride was later acquired by its rival Ultimate Fighting Championship in 2007.[207][208]

The Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act was introduced in 1999 and passed in 2000, to protect the rights and welfare of boxers in the United States. In May 2016, a bill was introduced to United States Congress by Markwayne Mullin, a politician and former MMA fighter, to extend the Ali Act to mixed martial arts.[209] In June 2016, US senator Rand Paul proposed an amendment to the US draft laws named after Ali, a proposal to eliminate the Selective Service System.[210]

Ranking in boxing history

Ali is regarded as one of the greatest boxers of all time by boxing commentators and historians. Ring Magazine, a prominent boxing magazine, named him number 1 in a 1998 ranking of greatest heavyweights from all eras.[211] The Associated Press voted Ali the No. 1 heavyweight of the 20th century in 1999.[212] In December 2007, ESPN listed Ali second in its choice of the greatest heavyweights of all time, behind Joe Louis.[213] Ali was named the second greatest pound for pound fighter in boxing history by ESPN, behind only welterweight and middleweight great Sugar Ray Robinson.[214]

Spoken word poetry and music

Ali often used rhyme schemes and spoken word poetry, both for when he was trash talking in boxing and as political poetry for his activism outside of boxing. He played a role in the shaping of the black poetic tradition, paving the way for The Last Poets in 1968, Gil Scott-Heron in 1970, and the emergence of rap music in the 1970s.[21]

In 1963, Ali released an album of spoken word music on Columbia Records titled I Am the Greatest, and in 1964, he recorded a cover version of the rhythm and blues song "Stand by Me".[215][216] I Am the Greatest reached number 61 on the album chart and was nominated for a Grammy Award. He later received a second Grammy nomination, for "Best Recording for Children", with his 1976 spoken word novelty record, The Adventures of Ali and His Gang vs. Mr. Tooth Decay.[23]

Ali was an influential figure in the world of hip hop music. As a "rhyming trickster", he was noted for his "funky delivery", "boasts", "comical trash talk", and "endless quotables".[22] According to Rolling Stone, his "freestyle skills" and his "rhymes, flow, and braggadocio" would "one day become typical of old school MCs" like Run–D.M.C. and LL Cool J, and his "outsized ego foreshadowed the vainglorious excesses of Kanye West, while his Afrocentric consciousness and cutting honesty pointed forward to modern bards like Rakim, Nas, Jay-Z, and Kendrick Lamar."[23] Ali has been cited as an inspiration by rappers such as LL Cool J,[22] Public Enemy's Chuck D,[217] Jay-Z, Eminem, Sean Combs, Slick Rick, Nas and MC Lyte.[218] Ali has been referenced in a number of hip hop songs, including The Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight", the Fugees' "Ready or Not", EPMD's "You're a Customer" and Will Smith's "Gettin' Jiggy wit It".[218]

In the media and popular culture

As a world champion boxer, social activist, and pop cuture icon, Ali was the subject of numerous books, films, music, video games, TV shows, and other creative works.

Ali appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated on 37 different occasions, second only to Michael Jordan.[219][needs update?] He also appeared on the cover of Time Magazine 5 times, the most of any athlete.[citation needed]

Ali had a cameo role in the 1962 film version of Requiem for a Heavyweight, and during his exile, he starred in the short-lived Broadway musical, Buck White (1969).

Ali appeared in the documentary film Black Rodeo (1972) riding both a horse and a bull. His autobiography The Greatest: My Own Story, written with Richard Durham, was published in 1975.[220] In 1977 the book was adapted into a film called The Greatest, in which Ali played himself and Ernest Borgnine played Angelo Dundee.

The film Freedom Road, made in 1978, features Muhammad Ali in a rare acting role as Gideon Jackson, a former slave and Union (American Civil War) soldier in 1870s Virginia, who gets elected to the U.S. Senate and battles other former slaves and white sharecroppers to keep the land they have tended all their lives.

On the set of Freedom Road Ali met Canadian singer-songwriter Michel (also known as Robert Williams, a co-founder of The Kindness Offensive[221]), and subsequently helped create Michel's album entitled The First Flight of the Gizzelda Dragon and an unaired television special featuring them both.[222]

Ali was the subject of This Is Your Life (UK TV series) in 1978 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews.[223] Ali was featured in Superman vs. Muhammad Ali, a 1978 DC Comics comic book pitting the champ against the superhero. In 1979, Ali guest-starred as himself in an episode of the NBC sitcom Diff'rent Strokes.

He also wrote several best-selling books about his career, including The Greatest: My Own Story and The Soul of a Butterfly. The Muhammad Ali Effect, named after Ali, is a term that came into use in psychology in the 1980s, as he stated in his autobiography The Greatest: My Own Story: "I only said I was the greatest, not the smartest."[220] According to this effect, when people are asked to rate their intelligence and moral behavior in comparison to others, people will rate themselves as more moral, but not more intelligent than others.[224][225]

When We Were Kings, a 1996 documentary about the Rumble in the Jungle, won an Academy Award,[226] and the 2001 biopic Ali garnered an Oscar nomination for Will Smith's portrayal of the lead role.[227] The latter film was directed by Michael Mann, with mixed reviews, the positives given to Smith's portrayal of Ali. Prior to making the film, Smith rejected the role until Ali requested that he accept it. Smith said the first thing Ali told him was: "Man you're almost pretty enough to play me."[228]

In 2002, for his contributions to the entertainment industry, Ali was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard.[229] His star is the only one to be mounted on a vertical surface, out of deference to his request that his name not be walked upon.[230][231]

The Trials of Muhammad Ali, a documentary directed by Bill Siegel that focuses on Ali's refusal of the draft during the Vietnam War, opened in Manhattan on August 23, 2013.[139][232] A made-for-TV movie called Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight, also in 2013, dramatized the same aspect of Ali's life.

Professional boxing record

| 61 fights | 56 wins | 5 losses |

|---|---|---|

| By knockout | 37 | 1 |

| By decision | 19 | 4 |

| No. | Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round, time | Date | Age | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61 | Loss | 56–5 | UD | 10 | Dec 11, 1981 | 39 years, 328 days | |||

| 60 | Loss | 56–4 | RTD | 10 (15), 3:00 | Oct 2, 1980 | 38 years, 259 days | For WBC, vacant The Ring and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 59 | Win | 56–3 | UD | 15 | Sep 15, 1978 | 36 years, 241 days | Won WBA, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 58 | Loss | 55–3 | SD | 15 | Feb 15, 1978 | 36 years, 29 days | Lost WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 57 | Win | 55–2 | UD | 15 | Sep 29, 1977 | 35 years, 255 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 56 | Win | 54–2 | UD | 15 | May 16, 1977 | 35 years, 119 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 55 | Win | 53–2 | UD | 15 | Sep 28, 1976 | 34 years, 255 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 54 | Win | 52–2 | TKO | 5 (15), 2:05 | May 24, 1976 | 34 years, 128 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 53 | Win | 51–2 | UD | 15 | Apr 30, 1976 | 34 years, 104 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 52 | Win | 50–2 | KO | 5 (15), 2:46 | Feb 20, 1976 | 34 years, 34 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 51 | Win | 49–2 | TKO | 14 (15), 3:00 | Oct 1, 1975 | 33 years, 257 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles; RTD according to some contemporary sources | ||

| 50 | Win | 48–2 | UD | 15 | Jun 30, 1975 | 33 years, 164 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 49 | Win | 47–2 | TKO | 11 (15), 1:08 | May 16, 1975 | 33 years, 119 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 48 | Win | 46–2 | TKO | 15 (15), 2:41 | Mar 24, 1975 | 33 years, 66 days | Retained WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 47 | Win | 45–2 | KO | 8 (15), 2:58 | Oct 30, 1974 | 32 years, 286 days | Won WBA, WBC, The Ring, and lineal heavyweight titles | ||

| 46 | Win | 44–2 | UD | 12 | Jan 28, 1974 | 32 years, 11 days | Retained NABF heavyweight title | ||

| 45 | Win | 43–2 | UD | 12 | Oct 20, 1973 | 31 years, 276 days | |||

| 44 | Win | 42–2 | SD | 12 | Sep 10, 1973 | 31 years, 236 days | Won NABF heavyweight title | ||

| 43 | Loss | 41–2 | SD | 12 | Mar 31, 1973 | 31 years, 73 days | Lost NABF heavyweight title | ||

| 42 | Win | 41–1 | UD | 12 | Feb 14, 1973 | 31 years, 28 days | |||

| 41 | Win | 40–1 | KO | 8 (12), 0:40 | Nov 21, 1972 | 30 years, 309 days | Retained NABF heavyweight title | ||

| 40 | Win | 39–1 | RTD | 7 (12), 3:00 | Sep 20, 1972 | 30 years, 247 days | Retained NABF heavyweight title | ||

| 39 | Win | 38–1 | TKO | 11 (12), 1:15 | Jul 19, 1972 | 30 years, 184 days | |||