Mark Tully

Mark Tully | |

|---|---|

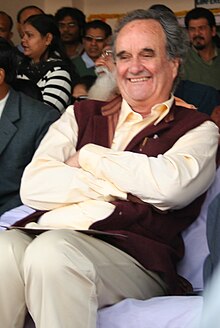

Tully in September 2011 | |

| Born | William Mark Tully 24 October 1935 |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Marlborough College Trinity Hall, Cambridge |

| Occupations |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Sir William Mark Tully, KBE (born 24 October 1935)[1][2] is a British journalist and the former Bureau Chief of BBC, New Delhi, a position he held for 20 years.[3] He worked with the BBC for 30 years before resigning in July 1994.[4] The recipient of several awards, Tully has authored nine books. He is a member of the Oriental Club.

Personal life

[edit]Tully was born in Tollygunge in India [5] His father was a British businessman who was a partner in one of the leading managing agencies of the British Raj. He spent the first decade of his childhood in India, although without being allowed to socialise with Indian people; at the age of four, he was sent to a "British boarding school" in Darjeeling,[6][7] before going to England for further schooling from the age of nine. There he was educated at Twyford School (Hampshire), Marlborough College and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, where he studied Theology.[6]

After Cambridge, Tully intended to become a priest in the Church of England but abandoned the vocation after just two terms at Lincoln Theological College, admitting later that he had doubts about "trusting [his] sexuality to behave as a Christian priest".[2] His personal life has been complex. In 2001 he married Margaret, with whom he has four children in London. When in India, however, he lives with his girlfriend Gillian Wright.[8][9] Tully also holds an Overseas Citizenship of India card.[10]

Journalistic career

[edit]Tully joined the BBC in 1964 and moved back to India in 1965 to work as the corporation's India Correspondent.[2][11][12] He covered all the major incidents in South Asia during his tenure, ranging from Indo-Pakistan conflicts, Bhopal gas tragedy, Operation Blue Star (and the subsequent assassination of Indira Gandhi, anti-Sikh riots), Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi to the Demolition of Babri Masjid.[13][14][15] He was barred from entering India during Emergency in 1975–77 when Prime Minister Mrs Gandhi had imposed censorship curbs on the media.

Tully resigned from the BBC in July 1994, after an argument with John Birt, the then Director General. He accused Birt of "running the corporation by fear" and "turning the BBC into a secretive monolith with poor ratings and a demoralised staff".[4] In 1994 he presented an episode of BBCs Great Railway Journeys "Karachi to The Khyber Pass" travelling by train across Pakistan. Since 1994 he has been working as a freelance journalist and broadcaster based in New Delhi.[11][13] He was the regular presenter of the weekly BBC Radio 4 programme Something Understood[16] until the BBC announced its cessation in 2019.[17]

As a guest of the Bangalore Initiative for Religious Dialogue on 7 October 2010 he spoke on How certain should we be? The problem of religious pluralism. He described his experiences and the fact that India had historically been home to all the world's major religions. He said that had taught him that there are many ways to God.[18]

Tully is patron of the British branch of Child in Need India (CINI UK).[19] Tully is equally well versed in English and Hindi. He had contributed his heartfelt efforts to keep literature alive and had been key speaker among 50 speakers of second Kalinga Literary Festival on 17 May 2015, where he explored the role of literature in nation building.[20]

Awards and honours

[edit]Tully was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1985 and was awarded the Padma Shri in 1992.[6] He was knighted in the New Year Honours 2002,[21] receiving a KBE, and in 2005 he received the Padma Bhushan.[22] BAFTA in 1985 for lifelong achievement.[23] He was conferred the coveted RedInk Lifetime Achievement Award of the Mumbai Press Club

Books

[edit]Tully's first book on India Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi's Last Battle (1985) was co-authored with his colleague at BBC Delhi, Satish Jacob; the book dealt with the events leading up to Operation Blue Star, Indian military action carried out between 1 and 8 June 1984 to remove militant religious leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his followers from the buildings of the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) complex in Amritsar, Punjab.

His next book Raj to Rajiv: 40 Years of Indian Independence was written with Zareer Masani, and was based on a BBC radio series of the same name. In the US, this book was published under the title India: Forty Years of Independence.

Tully's No Full Stops in India (1988), a collection of journalistic essays, was published in the US as The Defeat of a Congress-man. The Independent wrote that "Tully's profound knowledge and sympathy .. unravels a few of the more bewildering and enchanting mysteries of the subcontinent."[24]

Tully's only work of fiction, The Heart of India, was published in 1995.

In 2002 came India in Slow Motion, written in collaboration with Gillian Wright and published by Viking. Reviewing the book in The Observer, Michael Holland wrote of Tully that "Few foreigners manage to get under the skin of the world's biggest democracy the way he does, and fewer still can write about it with the clarity and insight he brings to all his work."[25]

Tully later wrote India's Unending Journey (2008) and India: The Road Ahead (2011), published in India under the title Non-Stop India.

In the area of religion, Tully has written An Investigation into The Lives of Jesus (1996) to accompany the BBC series of the same name, and Mother (1992) on Mother Teresa.

The anonymously authored Hindutva Sex and Adventure is a novel featuring a main character with strong similarities to Tully. Tully himself has stated that "I am amazed that Roli Books should publish such thinly disguised plagiarism, and allow the author to hide in a cavalier manner behind a nom-de-plume. The book is clearly modelled on my career, even down to the name of the main character. That character's journalism is abysmal, and his views on Hindutva and Hinduism do not in any way reflect mine. I would disagree with them profoundly".[26]

His latest book Upcountry Tales: Once Upon A Time In The Heart Of India (2017) is a collection of short stories set in rural north India.[27][28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Birthdays". The Guardian. Guardian News & Media. 29 October 2014. p. 47.

- ^ a b c "Mark Tully: The voice of India". London: BBC. 31 December 2001. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ "Media reportage: Interview with Mark Tully". The Hindu. 20 February 2000. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ a b Victor, Peter (10 July 1994). "Tully quits BBC". The Independent. London. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ "Why Mark Tully needs a Calcutta birth certificate at 78". BBC News. 20 August 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ a b c "Meeting Mark". The Hindu. 18 June 2007. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ Lakhani, Brenda (2003). "British and Indian influences in the identities and literature of Mark Tully and Ruskin Bond". University of North Texas. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ "Mark Tully: The Voice of India". BBC. 31 December 2001. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "Mighty Words Indeed". The Hindu. 1 November 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "Why Mark Tully needs a Calcutta birth certificate at 78". BBC News. 19 August 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Mark Tully to give annual Toleration lecture at the University of York". The University of York. Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ Drogin, Bob (22 December 1992). "Profile The BBC's Battered Sahib Mark Tully has been expelled by India, chased by mobs and picketed. He loves his job". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ a b "It's Sir Mark Tully in UK honors list". CNN. 31 December 2001. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ "After Blue Star". BBC. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ^ Tully, Mark (5 December 2002). "Tearing down the Babri Masjid". London: BBC. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ^ "Mark Tully". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ Marshall, Michelle (16 April 2019). "Mark Tully: BBC Radio 4 host speaks out on shock programme axe 'I feel sad for myself'". Daily Express. London. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ "Former BBC-India Chief Highlights Multiple Paths To God". Hindu American Foundation. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ "About Us | Child in Need India | CINI". Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ "50 Speakers to attend Kalinga Literary Festival 2015". Odisha News Insight. 2 May 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ "An honour, says Tully". The Hindu. 1 January 2002. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ "Padma Bhushan Awardees". Indian government. 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards". awards.bafta.org. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "The Independent". Book Review: No Full Stops in India. independent.co.uk. 20 September 1992. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Holland, Michael (7 December 2003). "The Observer". Slow Progress: Michael Holland on India in Slow Motion by Mark Tully. guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Nelson, Dean (5 April 2010). "Former BBC correspondent Sir Mark Tully attacked in novel". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Mark Tully's latest from the frontlines of 'upcountry India'". The Tribune. 12 November 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "A date with destiny". tabla!. 5 January 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- "Interview with Mark Tully". Sussex - BBC Centenary Collection. Connected Histories of the BBC. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1935 births

- 20th-century British essayists

- 20th-century British journalists

- Alumni of Lincoln Theological College

- Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge

- British Christians

- British radio personalities

- British travel writers

- British political writers

- Journalists from West Bengal

- Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Living people

- People educated at Marlborough College

- People educated at Twyford School

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in literature & education

- Writers from Kolkata

- Christian and Hindu interfaith dialogue

- British expatriates in India

- People with Overseas Citizenship of India