North Carolina: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 554802128 by 75.138.217.20 (talk) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|LargestCity = [[Charlotte, North Carolina|Charlotte]] |

|LargestCity = [[Charlotte, North Carolina|Charlotte]] |

||

|LargestMetro = [[Charlotte metropolitan area|Charlotte metro area]] |

|LargestMetro = [[Charlotte metropolitan area|Charlotte metro area]] |

||

|LargestCounty = |

|LargestCounty = ((YOUR ASE MOM , North Carolina|Wake]] |

||

|Old Capital = [[New Bern, North Carolina|New Bern]] |

|Old Capital = [[New Bern, North Carolina|New Bern]] |

||

|Capital = [[Raleigh, North Carolina|Raleigh]] |

|Capital = [[Raleigh, North Carolina|Raleigh]] |

||

Revision as of 18:02, 15 May 2013

North Carolina | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Province of North Carolina |

| Admitted to the Union | November 21, 1789 (12th) |

| Capital | Raleigh |

| Largest city | Charlotte |

| Largest county or equivalent | ((YOUR ASE MOM , North Carolina |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Charlotte metro area |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Pat McCrory (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Dan Forest (R) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. senators | Richard Burr (R) Kay Hagan (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 4 Democrats, 9 Republicans (list) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 9,752,073 (2,012 est)[1] |

| • Density | 200.2/sq mi (77.3/km2) |

| • Median household income | $44,670[2] |

| • Income rank | 38th[2] |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | English (90.70%) Spanish (6.18%)[3] |

| Latitude | 33° 50′ N to 36° 35′ N |

| Longitude | 75° 28′ W to 84° 19′ W |

North Carolina (/ˌnɔːrθ kærəˈlaɪnə/ ⓘ) is a state in Southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west, Virginia to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. North Carolina is the 28th most extensive and the 10th most populous of the 50 United States. North Carolina is known as the Tar Heel State and the Old North State.

North Carolina is composed of 100 counties. North Carolina's two largest metropolitan areas are among the top ten fastest growing in the country.[7] Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte. In the past five decades, North Carolina's economy has undergone a transition from heavy reliance upon tobacco, textiles, and furniture making to a more diversified economy with engineering, energy, biotechnology, and finance sectors.[8][9]

North Carolina has a wide range of elevations, from sea level on the coast to 6,684 feet (2,037 m) at Mount Mitchell, the highest point in the Eastern US.[10] The climate of the coastal plains is strongly influenced by the Atlantic Ocean. Most of the state falls in the humid subtropical climate zone. More than 300 miles (500 km) from the coast, the western, mountainous part of the state has a subtropical highland climate.

Geography

North Carolina borders South Carolina on the south, Georgia on the southwest, Tennessee on the west, Virginia on the north, and the Atlantic Ocean on the east. The United States Census Bureau classifies North Carolina as a southern state in the subcategory of being one of the South Atlantic States.

North Carolina consists of three main geographic sections: the coastal plain, which occupies the eastern 45% of the state; the Piedmont region, which contains the middle 35%; and the Appalachian Mountains and foothills. The extreme eastern section of the state contains the Outer Banks, a string of sandy, narrow islands which form a barrier between the Atlantic Ocean and two inland waterways or "sounds": Albemarle Sound in the north and Pamlico Sound in the south. They are the two largest landlocked sounds in the United States. So many ships have been lost off Cape Hatteras that the area is known as the "Graveyard of the Atlantic". More than 1,000 ships have sunk in these waters since records began in 1526. The most famous of these is the Queen Anne's Revenge (flagship of Blackbeard) which went aground in Beaufort Inlet in 1718.[11]

Immediately inland, the coastal plain is relatively flat, with rich soil ideal for growing tobacco, soybeans, melons, and cotton. The coastal plain is North Carolina's most rural section, with few large towns or cities. Agriculture remains an important industry.

The coastal plain transitions to the Piedmont region along the "fall line", a line which marks the elevation at which waterfalls first appear on streams and rivers. The Piedmont region of central North Carolina is the state's most urbanized and densely populated section. It consists of gently rolling countryside frequently broken by hills or low mountain ridges. Small, isolated, and deeply eroded mountain ranges and peaks are located in the Piedmont, including the Sauratown Mountains, Pilot Mountain, the Uwharrie Mountains, Crowder's Mountain, King's Pinnacle, the Brushy Mountains, and the South Mountains. The Piedmont ranges from about 300–400 feet (90–120 m) elevation in the east to over 1,000 feet (300 m) in the west. Due to the rapid population growth in the Piedmont, a significant part of the rural area in this region is being transformed into suburbs with shopping centers, housing, and corporate offices. Agriculture is steadily declining in its importance. The major rivers of the Piedmont, such as the Yadkin and Catawba, tend to be fast-flowing, shallow, and narrow.

The western section of the state is part of the Appalachian Mountain range. Among the subranges of the Appalachians located in the state are the Great Smoky Mountains, Blue Ridge Mountains, Great Balsam Mountains, and the Black Mountains. The Black Mountains are the highest in the Eastern United States, and culminate in Mount Mitchell at 6,684 feet (2,037 m).[12] It is the highest point east of the Mississippi River. Although agriculture still remains important, tourism has become a dominant industry in the mountains. Growing Christmas trees has recently been an important industry. Due to the higher altitude, the climate in the mountains often differs markedly from the rest of the state. Winter in western North Carolina typically features high snowfall and subfreezing temperatures more akin to those of a midwestern state than of a southern state.

North Carolina has 17 major river basins. The basins west of the Blue Ridge Mountains flow to the Gulf of Mexico (via the Ohio and then the Mississippi River). All the others flow to the Atlantic Ocean. Of the 17 basins, 11 originate within the state of North Carolina, but only four are contained entirely within the state's border – the Cape Fear, Neuse, White Oak and Tar-Pamlico.[13]

Climate

The geographical divisions of North Carolina are useful when discussing the climate of the state.

The climate of the coastal plain is influenced by the Atlantic Ocean, which keeps temperatures mild in winter and moderate in summer. The highest coastal, daytime temperature averages less than 89 °F (32 °C) during summer months. The coast has mild temperature in winter, with daytime highs rarely below 40 °F (4 °C). The average daytime temperature in the coastal plain is usually in the mid-50s °F (11–14 °C) in winter. Temperature in the coastal plain only occasionally drop below the freezing point at night. The coastal plain averages only around 1 inch (2.5 cm) of snow or ice annually, and in many years, there may be no snow or ice at all.

The Atlantic Ocean has less influence on the climate of the Piedmont region, which has hotter summers and colder winters than in the coast. Daytime highs in the Piedmont often average over 90 °F (32 °C) in the summer. While it is not common for the temperature to reach over 100 °F (38 °C) in the state, such temperature, if it occurs, is found in the lower areas of the Piedmont. The weaker influence of the Atlantic Ocean also means that temperatures in the Piedmont often fluctuate more widely than in the coast.

In winter, the Piedmont is colder than the coast, with temperatures usually averaging in the upper 40s–lower 50s °F (8–12 °C) during the day and often dropping below the freezing point at night. The region averages from 3–5 in (8–13 cm) of snowfall annually in the Charlotte area, to around 12 in (30 cm) in the Asheville area. The Piedmont is especially notorious for sleet and freezing rain. Freezing rain can be heavy enough to snarl traffic and break down trees and power lines. Annual precipitation and humidity are lower in the Piedmont than in the mountains or the coast, but even at its lowest, the average is 40 in (1,020 mm) per year.

The Appalachian Mountains are the coolest area of the state, with daytime temperatures averaging in the low 40s and upper 30s °F (6–3 °C) for highs in the winter and falling into the low 20s °F (−5 °C) or lower on winter nights. Relatively cool summers have temperatures rarely rising above 80 °F (27 °C). Average snowfall in many areas exceeds 30 in (76 cm) per year, and can be heavy at the higher elevations. For example, during the Blizzard of 1993 more than 60 in (152 cm) of snow fell on Mount Mitchell over a period of three days. Additionally, Mount Mitchell has received snow in every month of the year.

Severe weather occurs regularly in North Carolina. On average, a hurricane hits the state once a decade. Destructive hurricanes that have struck the state include Hurricane Fran, Hurricane Floyd, and Hurricane Hazel, the strongest storm to make landfall in the state as a Category 4 in 1954. Hurricane Isabel stands out as the most damaging of the 21st century.[14] Tropical storms arrive every 3 or 4 years. In addition, many hurricanes and tropical storms graze the state. In some years, several hurricanes or tropical storms can directly strike the state or brush across the coastal areas. Only Florida and Louisiana are hit by hurricanes more often. Although many people believe that hurricanes menace only coastal areas, the rare hurricane which moves inland quickly enough can cause severe damage. In 1989 Hurricane Hugo caused heavy damage in Charlotte and even as far inland as the Blue Ridge Mountains in the northwestern part of the state. On average, North Carolina has 50 days of thunderstorm activity per year, with some storms becoming severe enough to produce hail, flash floods, and damaging winds.

North Carolina averages fewer than 20 tornadoes per year. Many of these are produced by hurricanes or tropical storms along the coastal plain. Tornadoes from thunderstorms are a risk, especially in the eastern part of the state. The western Peidmont is often protected by the mountains breaking storms up as they try to cross over them. The storms will often reform farther east. Also a weather feature known as "cold air damming" occurs in the western part of the state. This can also weaken storms but can also lead to major ice events in winter."[15]

In April 2011, one of the worst tornado outbreaks in North Carolina's history occurred. 25 confirmed tornadoes touched down, mainly in the Eastern Piedmont, killing at least 24 people. Damages in the capital of Raleigh alone were over $115 million.[16][17]

| Monthly normal high and low temperatures (Fahrenheit) for various North Carolina cities. | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asheville[18] | 47/27 | 51/30 | 59/35 | 68/43 | 75/51 | 81/60 | 84/64 | 83/63 | 77/56 | 68/45 | 59/36 | 49/29 |

| Boone[19] | 42/21 | 45/23 | 52/29 | 61/37 | 69/46 | 76/54 | 79/58 | 78/57 | 72/50 | 63/39 | 54/31 | 45/24 |

| Cape Hatteras[20] | 52/39 | 54/40 | 59/45 | 66/53 | 74/61 | 81/69 | 85/74 | 84/73 | 80/69 | 72/60 | 64/51 | 56/43 |

| Charlotte[18] | 51/30 | 55/33 | 63/39 | 72/47 | 79/56 | 86/64 | 89/68 | 88/67 | 81/60 | 72/49 | 62/39 | 53/32 |

| Fayetteville[21] | 53/31 | 56/33 | 64/39 | 73/47 | 80/56 | 87/65 | 90/70 | 89/69 | 83/63 | 74/49 | 65/41 | 56/34 |

| Greensboro[21] | 48/30 | 52/32 | 61/39 | 70/47 | 78/56 | 85/65 | 88/69 | 86/68 | 80/61 | 70/49 | 61/40 | 51/32 |

| Raleigh[21] | 51/31 | 55/34 | 63/40 | 72/48 | 80/57 | 87/66 | 90/70 | 88/69 | 82/62 | 73/50 | 64/41 | 54/33 |

| Wilmington[22] | 56/36 | 60/38 | 66/44 | 74/52 | 81/60 | 87/69 | 90/73 | 88/71 | 84/66 | 76/55 | 68/45 | 59/38 |

History

Spanish colonial forces were the first Europeans to make a permanent settlement in the area, when the Juan Pardo-led Expedition built Fort San Juan in 1567. This was sited at Joara, a Mississippian culture regional chiefdom in the western interior; present-day Morganton developed near there. The fort lasted only 18 months as the natives killed all but one of the 120 men Pardo had stationed at a total of six forts in the area.[23]

North Carolina became one of the English Thirteen Colonies, and was originally known as Province of Carolina, along with South Carolina. The northern and southern parts of the original Province separated in 1729. Originally settled by small farmers, sometimes having a few slaves, who were oriented toward subsistence agriculture, the colony lacked cities or towns. Pirates menaced the seacoast settlements, but by 1718 the pirates had been captured and executed. Growth was strong in the middle of the 18th century, as the economy attracted Scotch-Irish, Quaker, English and German immigrants. The colonists supported the American Revolution, as the Loyalists were weak.

Several efforts to establish a seat of government failed until 1766, when New Bern, the largest town, was selected. Construction of Governor Tryon Palace began in 1767 and was completed in 1771. This new structure served as the governor's residence and office, as well as a meeting place for the Upper House. When New Bern was threatened by enemy attacks during the American Revolution, the government took to the roads again, meeting in both coastal and inland towns of the state. The "palace" soon became neglected and in 1798 all but one wing burned to the ground. In 1788 Raleigh was chosen as the site of the new capital, as its central location protected it from attacks from the coast. Officially established in 1792 as both county seat and state capital, the city was named for Sir Walter Raleigh, sponsor of Roanoke, the "lost colony" on Roanoke Island.

North Carolina made the smallest per-capita contribution to the war of any state, as only 7800 men joined the Continental Army under General George Washington; an additional 10,000 served in local militia units under such leaders as General Nathanael Greene.[24] There was some military action, especially in 1780–81. Many Carolinian frontiersmen had moved west over the mountains into the Washington District (later known as Tennessee), but in 1789 the state was persuaded to relinquish its claim to the western lands, ceding them to the national government so that the Northwest Territory could be organized and managed nationally.

After 1800, cotton and tobacco became important export crops. The eastern half of the state, especially the Tidewater, developed a slave society based on a plantation system and slave labor. Many free people of color migrated to the frontier along with their European-American neighbors, where the social system was looser. By 1810, nearly 3 percent of the free population was comprised of free people of color, who numbered slightly more than 10,000. The western areas were dominated by white families who operated small subsistence farms. In the early national period, the state became a center of Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democracy with a strong Whig presence, especially in the West. The rights of free blacks were reduced in 1835 after Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831, and the legislature withdrew their right to vote.

On May 20, 1861, North Carolina was the last of the Confederate states to declare secession from the Union, 13 days after the Tennessee legislature voted for secession. Some 125,000 North Carolinians saw military service; 20,000 were killed in battle, the most of any state in the confederacy, and 21,000 died of disease. The state government was reluctant to support the demands of the national government in Richmond, and the state was the scene of only small battles.

With the end of the war in 1865, the Reconstruction Era began. The United States abolished slavery without compensation to the slaveholders, or reparations to the freedmen. A Republican Party coalition of black Freedmen, northern Carpetbaggers, and local Scalawags controlled state government for three years. The white conservative Democrats regained control of the state legislature in 1870, in part by Ku Klux Klan violence and physical intimidation at the polls to suppress black voting. Republicans were elected as governor until 1876, when the Red Shirts, a paramilitary organization allied with the Democratic Party that arose in 1875, helped suppress black voting.

Democrats were elected to the legislature and governor's office, but the Populists attracted voters displeased with them. A biracial, Populist-Republican Fusionist coalition gained the governor's office in the 1896 election. The Democrats regained control of the legislature in 1896, and passed laws to impose Jim Crow and racial segregation of public facilities. Voters of North Carolina's 2nd congressional district elected a total of four African-American US Congressmen through these years of the late nineteenth century. Political tensions were so high, that a small group of white Democrats in 1898 planned to take over the Wilmington government if their candidates were not elected. In the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898, more than 1500 white men attacked the black newspaper and neighborhood, killed numerous men, and ran off the white Republican mayor and aldermen. They installed their own people, and elected Alfred M. Waddell as mayor, in the only coup d'état in United States history.[25]

In 1899 the state legislature passed a new constitution with requirements for poll taxes and literacy tests for voter registration; it effectively disfranchised most blacks in the state.[26] Exclusion from voting had wide effects: it meant that blacks could not qualify to serve on juries or in any local office. After a decade of white supremacy, many people forgot that North Carolina had thriving middle-class blacks.[27] They essentially had no political voice in the state until after the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed to enforce their constitutional rights. It was not until 1992 that another African American was elected as a US Representative from North Carolina.

As in the rest of the former Confederate states, North Carolina had become a one-party state dominated by the Democratic Party. Impoverished by the Civil War, the state continued with an economy based on tobacco, cotton and agriculture. Towns and cities remained few in the east. A major industrial base emerged in the late 19th century in the western counties of the Piedmont based on cotton mills established at the fall line. Railroads were built to connect the new industrializing cities. The state was the site of the first successful controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air flight, by the Wright brothers, near Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903.

North Carolina was hard hit by the Great Depression, but the New Deal's farm programs of Franklin D. Roosevelt for cotton and tobacco significantly helped the farmers. After World War II, the state's economy grew rapidly, highlighted by the growth of such cities as Charlotte, Raleigh, and Durham. Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill form the Research Triangle, a major area of universities and advanced scientific and technical research. In the 1990s, Charlotte became a major regional and national banking center.

By the 1970s, passage of federal civil rights legislation, and other social changes led to many residents changing their party affiliation. Conservative whites began to vote for Republican national candidates, and gradually for more Republicans on the local level. Since gaining federal support under Lyndon Johnson to enforce their constitutional rights as citizens, African Americans have affiliated with and consistently elected officials of the Democratic Party.

Native Americans, lost colonies, and permanent settlement

North Carolina was inhabited for thousands of years by succeeding cultures of prehistoric indigenous cultures. Before 200 AD, they were building earthwork mounds, which were used for ceremonial and religious purposes. Succeeding peoples, including those of the ancient Mississippian culture established by 1000 AD in the Piedmont, continued to build or add on to such mounds. In the 500–700 years preceding European contact, the Mississippian culture built large, complex cities and maintained far-flung regional trading networks. Its largest city was Cahokia, located in present-day Illinois near the Mississippi River.

Historically documented tribes in the North Carolina region include the Carolina Algonquian-speaking tribes of the coastal areas, such as the Chowanoke, Roanoke, Pamlico, Machapunga, Coree, Cape Fear Indians, and others, who were the first encountered by the English; the Iroquoian-speaking Meherrin, Cherokee and Tuscarora of the interior; and Southeastern Siouan tribes, such as the Cheraw, Lumbee, Waxhaw, Saponi, Waccamaw, and Catawba.

Spanish explorers traveling inland in the 16th century met Mississippian culture people at Joara, a regional chiefdom near present-day Morganton. Records of Hernando de Soto attested to his meeting with them in 1540. In 1567 Captain Juan Pardo led an expedition to claim the area for the Spanish colony, as well as establish another route to protect silver mines in Mexico. Pardo made a winter base at Joara, which he renamed Cuenca. The expedition built Fort San Juan and left 30 men, while Pardo traveled further, and built and staffed five other forts. He returned by a different route to Santa Elena on Parris Island, South Carolina, then a center of Spanish Florida. In the spring of 1568, natives killed all but one of the soldiers and burned the six forts in the interior, including the one at Fort San Juan. Although the Spanish never returned to the interior, this marked the first European attempt at colonization of the interior of what became the United States. A 16th-century journal by Pardo's scribe Bandera and archaeological findings since 1986 at Joara have confirmed the settlement.[28][29]

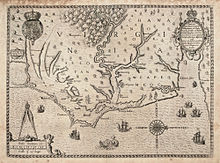

In 1584, Elizabeth I, granted a charter to Sir Walter Raleigh, for whom the state capital is named, for land in present-day North Carolina (then Virginia).[30] Raleigh established two colonies on the coast in the late 1580s, but both failed. It was the second American territory which the English attempted to colonize. The demise of the "Lost Colony" of Roanoke Island, remains one of the mysteries of American history. Virginia Dare, the first English child to be born in North America, was born on Roanoke Island on August 18, 1587. Dare County is named for her.

As early as 1650, colonists from the Virginia colony moved into the area of Albemarle Sound. By 1663, King Charles II of England granted a charter to start a new colony on the North American continent which generally established North Carolina's borders. He named it Carolina in honor of his father Charles I.[31] By 1665, a second charter was issued to attempt to resolve territorial questions. In 1710, due to disputes over governance, the Carolina colony began to split into North Carolina and South Carolina. The latter became a crown colony in 1729.

When a series of smallpox epidemics swept the South in the 1700s, they caused high fatalities among the Native Americans, who had no immunity to the disease (it had become endemic in Europe).[32] According to the historian Russell Thornton, "The 1738 epidemic was said to have killed one-half of the Cherokee, with other tribes of the area suffering equally."[33]

Colonial period and Revolutionary War

The first permanent European settlers of North Carolina after the Spanish in the 16th century were English colonists who migrated south from Virginia, following a rapid growth of the colony and the subsequent shortage of available farmland. Nathaniel Batts was documented as one of the first of these Virginian migrants. He settled south of the Chowan River and east of the Great Dismal Swamp in 1655.[34] By 1663, this northeastern area of the Province of Carolina, known as the Albemarle Settlements, was undergoing full-scale English settlement.[35] During the same period, the English monarch Charles II gave the province to the Lords Proprietors, a group of noblemen who had helped restore Charles to the throne in 1660. The new province of "Carolina" was named in honor and memory of King Charles I (Latin: Carolus). In 1712, North Carolina became a separate colony. Except for the Earl Granville holdings, it became a royal colony seventeen years later.[36]

Differences in the settlement patterns of eastern and western North Carolina, or the low country and uplands, affected the political, economic, and social life of the state from the eighteenth until the 20th century. The Tidewater in eastern North Carolina was settled chiefly by immigrants from rural England and the Scottish Highlands. The upcountry of western North Carolina was settled chiefly by Scots-Irish, English and German Protestants, the so-called "cohee". Arriving during the mid-to-late 18th century, the Scots-Irish from what is today Northern Ireland were the largest non-English immigrant group before the Revolution; English indentured servants were overwhelmingly the largest immigrant group prior to the Revolution.[37][38][39][38][39][40] During the American Revolutionary War, the English and Highland Scots of eastern North Carolina tended to remain loyal to the British Crown, because of longstanding business and personal connections with Great Britain. The English, Welsh, Scots-Irish and German settlers of western North Carolina tended to favor American independence from Britain.

Most of the English colonists arrived as indentured servants, hiring themselves out as laborers for a fixed period to pay for their passage. In the early years the line between indentured servants and African slaves or laborers was fluid. Some Africans were allowed to earn their freedom before slavery became a lifelong status. Most of the free colored families formed in North Carolina before the Revolution were descended from unions or marriages between free white women and enslaved or free African or African-American men. Because the mothers were free, their children were born free. Many had migrated or were descendants of migrants from colonial Virginia.[41] As the flow of indentured laborers to the colony decreased with improving economic conditions in Great Britain, more slaves were imported and the state's restrictions on slavery hardened. The economy's growth and prosperity was based on slave labor, devoted first to the production of tobacco.

On April 12, 1776, the colony became the first to instruct its delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence from the British crown, through the Halifax Resolves passed by the North Carolina Provincial Congress. The dates of both of these events are memorialized on the state flag and state seal.[42] Throughout the Revolutionary War, fierce guerrilla warfare erupted between bands of pro-independence and pro-British colonists. In some cases the war was also an excuse to settle private grudges and rivalries. A major American victory in the war took place at King's Mountain along the North Carolina–South Carolina border. On October 7, 1780 a force of 1000 mountain men from western North Carolina (including what is today the State of Tennessee) overwhelmed a force of some 1000 British troops led by Major Patrick Ferguson. Most of the British soldiers in this battle were Carolinians who had remained loyal to the British Crown (they were called "Tories"). The American victory at Kings Mountain gave the advantage to colonists who favored American independence, and it prevented the British Army from recruiting new soldiers from the Tories.

The road to Yorktown and America's independence from Great Britain led through North Carolina. As the British Army moved north from victories in Charleston and Camden, South Carolina, the Southern Division of the Continental Army and local militia prepared to meet them. Following General Daniel Morgan's victory over the British Cavalry Commander Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, southern commander Nathanael Greene led British Lord Charles Cornwallis across the heartland of North Carolina, and away from Cornwallis's base of supply in Charleston, South Carolina. This campaign is known as "The Race to the Dan" or "The Race for the River."[36]

In the Battle of Cowan's Ford, Cornwallis met resistance along the banks of the Catawba River at Cowan's Ford on February 1, 1781 in an attempt to engage General Morgan's forces during a tactical withdrawal.[43] This move to the northern part of the state was to combine with General Greene's newly recruited forces. Generals Greene and Cornwallis finally met at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in present-day Greensboro on March 15, 1781. Although the British troops held the field at the end of the battle, their casualties at the hands of the numerically superior American Army were crippling. Following this "Pyrrhic victory", Cornwallis chose to move to the Virginia coastline to get reinforcements, and to allow the Royal Navy to protect his battered army. This decision would result in Cornwallis's eventual defeat at Yorktown, Virginia later in 1781. The Patriots' victory there guaranteed American independence.

Antebellum period

On November 21, 1789, North Carolina became the twelfth state to ratify the Constitution. In 1840, it completed the state capitol building in Raleigh, still standing today. Most of North Carolina's slave owners and large plantations were located in the eastern portion of the state. Although North Carolina's plantation system was smaller and less cohesive than those of Virginia, Georgia or South Carolina, significant numbers of planters were concentrated in the counties around the port cities of Wilmington and Edenton, as well as suburban planters around the cities of Raleigh, Charlotte and Durham in the Piedmont. Planters owning large estates wielded significant political and socio-economic power in antebellum North Carolina, which was a slave society. They placed their interests above those of the generally non-slave holding "yeoman" farmers of western North Carolina. In mid-century, the state's rural and commercial areas were connected by the construction of a 129-mile (208 km) wooden plank road, known as a "farmer's railroad", from Fayetteville in the east to Bethania (northwest of Winston-Salem).[36]

Besides slaves, there were a number of free people of color in the state. Most were descended from free African Americans who had migrated along with neighbors from Virginia during the 18th century. The majority were the descendants of unions in the working classes between white women, indentured servants or free, and African men, indentured, slave or free.[44] After the Revolution, Quakers and Mennonites worked to persuade slaveholders to free their slaves. Some were inspired by their efforts and the language of rights of the Revolution, to arrange for manumission of their slaves. The number of free people of color rose markedly in the first couple of decades after the Revolution.[45]

On October 25, 1836 construction began on the Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad[46] to connect the port city of Wilmington with the state capital of Raleigh. In 1849 the North Carolina Railroad was created by act of the legislature to extend that railroad west to Greensboro, High Point, and Charlotte. During the Civil War, the Wilmington-to-Raleigh stretch of the railroad would be vital to the Confederate war effort; supplies shipped into Wilmington would be moved by rail through Raleigh to the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

During the antebellum period, North Carolina was an overwhelmingly rural state, even by Southern standards. In 1860 only one North Carolina town, the port city of Wilmington, had a population of more than 10,000. Raleigh, the state capital, had barely more than 5,000 residents.

While slaveholding was slightly less concentrated than in some Southern states, according to the 1860 census, more than 330,000 people, or 33% of the population of 992,622 were enslaved African Americans. They lived and worked chiefly on plantations in the eastern Tidewater. In addition, 30,463 free people of color lived in the state. They were also concentrated in the eastern coastal plain, especially at port cities such as Wilmington and New Bern, where a variety of jobs were available. Free African Americans were allowed to vote until 1835, when the state revoked their right to vote in restrictions following the slave rebellion of 1831 led by Nat Turner. Southern slave codes did make wilful killing of a slave illegal in most cases.[47] For example, in 1791 the North Carolina legislature made the willful killing of a slave murder, unless done in resisting or under moderate correction.[47]

American Civil War

In 1860, North Carolina was a slave state, in which about one-third of the population of 992,622 were enslaved African Americans. This was a smaller proportion than many Southern states. In addition, the state had just over 30,000 Free Negroes.[48] The state did not vote to join the Confederacy until President Abraham Lincoln called on it to invade its sister-state, South Carolina, becoming the last or second to last state to officially join the Confederacy. The title of "last to join the Confederacy" has been disputed because Tennessee informally seceded on May 7, 1861, making North Carolina the last to secede on May 20, 1861.[49][50] However, the Tennessee legislature did not formally vote to secede until June 8, 1861.[51]

North Carolina was the site of few battles, but it provided at least 125,000 troops to the Confederacy— far more than any other state. Approximately 40,000 of those troops died of disease, battlefield wounds, and starvation. North Carolina also supplied about 15,000 Union troops.[52] Elected in 1862, Governor Zebulon Baird Vance tried to maintain state autonomy against Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Richmond.

After secession, some North Carolinians had refused to support the Confederacy. Some of the yeomen farmers in the state's mountains and western Piedmont region remained neutral during the Civil War, while some covertly supported the Union cause during the conflict. Approximately 2,000 North Carolinians from western North Carolina enlisted in the Union Army and fought for the North in the war. Two additional Union Army regiments were raised in the coastal areas of the state that were occupied by Union forces in 1862 and 1863.

Confederate troops from all parts of North Carolina served in virtually all the major battles of the Army of Northern Virginia, the Confederacy's most famous army. The largest battle fought in North Carolina was at Bentonville, which was a futile attempt by Confederate General Joseph Johnston to slow Union General William Tecumseh Sherman's advance through the Carolinas in the spring of 1865.[36] In April 1865, after losing the Battle of Morrisville, Johnston surrendered to Sherman at Bennett Place, in what is today Durham. This was the last major Confederate Army to surrender. North Carolina's port city of Wilmington was the last Confederate port to fall to the Union, in February 1865 after the Union won the nearby Second Battle of Fort Fisher, its major defense downriver.

The first Confederate soldier to be killed in the Civil War was Private Henry Wyatt from North Carolina, in the Battle of Big Bethel in June 1861. At the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the 26th North Carolina Regiment participated in Pickett/Pettigrew's Charge and advanced the farthest into the Northern lines of any Confederate regiment. During the Battle of Chickamauga, the 58th North Carolina Regiment advanced farther than any other regiment on Snodgrass Hill to push back the remaining Union forces from the battlefield. At Appomattox Court House in Virginia in April 1865, the 75th North Carolina Regiment, a cavalry unit, fired the last shots of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the Civil War. For many years, North Carolinians proudly boasted that they had been "First at Bethel, Farthest at Gettysburg and Chickamauga, and Last at Appomattox."

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 393,751 | — | |

| 1800 | 478,103 | 21.4% | |

| 1810 | 556,526 | 16.4% | |

| 1820 | 638,829 | 14.8% | |

| 1830 | 737,987 | 15.5% | |

| 1840 | 753,419 | 2.1% | |

| 1850 | 869,039 | 15.3% | |

| 1860 | 992,622 | 14.2% | |

| 1870 | 1,071,361 | 7.9% | |

| 1880 | 1,399,750 | 30.7% | |

| 1890 | 1,617,949 | 15.6% | |

| 1900 | 1,893,810 | 17.1% | |

| 1910 | 2,206,287 | 16.5% | |

| 1920 | 2,559,123 | 16.0% | |

| 1930 | 3,170,276 | 23.9% | |

| 1940 | 3,571,623 | 12.7% | |

| 1950 | 4,061,929 | 13.7% | |

| 1960 | 4,556,155 | 12.2% | |

| 1970 | 5,082,059 | 11.5% | |

| 1980 | 5,881,766 | 15.7% | |

| 1990 | 6,628,637 | 12.7% | |

| 2000 | 8,049,313 | 21.4% | |

| 2010 | 9,535,483 | 18.5% | |

| 2012 (est.) | 9,752,073 | 2.3% | |

| Source: 1910–2010[53] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of North Carolina was 9,752,073 on July 1, 2012, a 2.3% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[1] Of the people residing in North Carolina, 58.5% were born in North Carolina, 33.1% were born in another US state, 1.0% were born in Puerto Rico, U.S. Island areas, or born abroad to American parent(s), and 7.4% were born in another country.[54]

As of 2011, 49.8% of North Carolina's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[55]

Ethnicity

Demographics of North Carolina covers the varieties of ethnic groups that reside in North Carolina, along with the relevant trends.

The state's racial composition in the 2010 Census:[56]

- White: 68.5% (65.3% non-Hispanic white)

- Black or African American: 21.5%

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race): 8.4%

- Asian: 2.2%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.1%

- Some other race: 4.3%

- Two or more races: 2.2%

Largest cities, 2011

In 2012, the US Census Bureau released 2011 population estimate counts for North Carolina's cities with populations above 70,000.[57]

| City | Population |

|---|---|

| Charlotte | 751,087

|

| Raleigh | 416,468

|

| Greensboro | 273,425

|

| Durham | 233,252

|

| Winston-Salem | 232,385

|

| Fayetteville | 203,945

|

| Cary | 139,633

|

| Wilmington | 108,297

|

| High Point | 105,753

|

| Greenville | 86,017

|

| Asheville | 84,458

|

| Concord | 80,597

|

| Gastonia | 72,068

|

| Jacksonville | 70,801

|

Largest combined statistical areas

North Carolina has three major Combined Statistical Areas with populations of more than 1.6 million (U.S. Census Bureau 2012 estimates):[58]

- Metrolina: Charlotte–Gastonia–Salisbury, North Carolina-South Carolina – population 2,452,619[58]

- The Triangle: Raleigh–Durham–Cary–Chapel Hill, North Carolina – population 1,998,808[58]

- The Triad: Greensboro–Winston-Salem–High Point, North Carolina – population 1,611,243[58]

Economy

According to a recent Forbes article written in 2013 Employment in the "Old North State" has gained many different industry sectors. See the following article summary: science, technology, energy and math, or STEM, industries in the area surrounding North Carolina's capital has grown 17.9 percent since 2001, placing Raleigh-Cary at No. 5 among the 51 largest metro areas in the country where technology is booming. In 2010 North Carolina's total gross state product was $424.9 billion.[59] In 2011 the civilian labor force was at around 4.5 million with employment near 4.1 million. The working population is employed across the major employment sectors. The economy of North Carolina covers 15 metropolitan areas.[60] In 2010, North Carolina was chosen as the third best state for business by Forbes Magazine, and the second best state by Chief Executive Officer Magazine.[61]

Transportation

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2012) |

Transportation systems in North Carolina consists of air, water, road, rail, and public transportation. North Carolina has the second largest state highway system in the country as well as the largest ferry system on the east coast.[62]

In 2011, the American State Litter Scorecard awarded North Carolina a high BEST rating for having some of America's cleanest public spaces and highways, and positive environmental conduct practices by citizens. North Carolina was the only state in the Southern United States to receive this Scorecard honor.[63]

Politics and government

The government of North Carolina is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. These consist of the Council of State (led by the Governor), the bicameral legislature (called the General Assembly), and the state court system (headed by the North Carolina Supreme Court). The state constitution delineates the structure and function of the state government. North Carolina has 13 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and two seats in the U.S. Senate. Recent changes in North Carolina politics include the change to a majority Republican legislature after the 2010 elections.

In 2012, the state flipped back to the Republican column in the Presidential race in 2012, giving its electoral votes to Mitt Romney. The state also elected its first Republican Governor and Lieutenant Governor, Pat McCrory and Dan Forest, in more than two decades. The Republican majorities in both the State House of Representatives and State Senate were increased to veto proof majorities. Several U.S. House of Representatives seats also flipped control, with the Republicans controlling 9 seats to the Democrats 4.

Education

Primary and secondary education

Elementary and secondary public schools are overseen by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. The North Carolina Superintendent of Public Instruction is the secretary of the North Carolina State Board of Education, but the board, rather than the superintendent, holds most of the legal authority for making public education policy. In 2009, the board's chairman also became the "chief executive officer" for the state's school system.[64][65] North Carolina has 115 public school systems,[66] each of which is overseen by a local school board. A county may have one or more systems within it. The largest school systems in North Carolina are the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, Wake County Public School System, Guilford County Schools, Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools, and Cumberland County Schools.[67] In total there are 2,425 public schools in the state, including 99 charter schools.[66]

Colleges and universities

In 1795, North Carolina opened the first public university in the United States—the University of North Carolina (currently named the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). More than 200 years later, the University of North Carolina system encompasses 17 public universities including UNC-Chapel Hill, North Carolina State University, East Carolina University, Western Carolina University, UNC Asheville, UNC Charlotte, UNC Greensboro, UNC Pembroke, UNC Wilmington, UNC School of the Arts, and Appalachian State University. The system also supports several well-known historically African-American colleges and universities such as North Carolina A&T State University, North Carolina Central University, Winston-Salem State University, Elizabeth City State University, and Fayetteville State University.[68] Along with its public universities, North Carolina has 58 public community colleges in its community college system.The largest university in North Carolina is currently North Carolina State University with more than 34,000 students.[69]

North Carolina is also home to many well-known private colleges and universities including: Duke University, Wake Forest University, Pfeiffer University, Lees-McRae College, Davidson College, Barton College, North Carolina Wesleyan College, Elon University, Guilford College (the first coeducational institution of higher learning in the South), Salem College (the first school for young women in the South), Shaw University (the first historically black college or university in the South), John Wesley College (North Carolina) (the oldest undergraduate theological education institution in North Carolina), Meredith College, Methodist University, Belmont Abbey College (the only Catholic college in the Carolinas), Campbell University, Mount Olive College, Montreat College, High Point University, and Lenoir-Rhyne University (the only Lutheran university in North Carolina).

Sports

North Carolina is home to three major league sports franchises: the Carolina Panthers of the National Football League and the Charlotte Bobcats of the National Basketball Association are based in Charlotte, while the Raleigh-based Carolina Hurricanes play in the National Hockey League. While North Carolina has no Major League Baseball team, it does have numerous minor league baseball teams, with the highest level of play coming from the AAA-affiliated Charlotte Knights and Durham Bulls. Additionally, North Carolina has minor league teams in other team sports including soccer, ice hockey, and arena football.

In addition to professional team sports, North Carolina is has a strong affiliation with NASCAR and stock car racing, with Charlotte Motor Speedway in Concord hosting two Sprint Cup Series races every year. Charlotte also hosts the NASCAR Hall of Fame, while Concord is the home of several top-flight racing teams including Hendrick Motorsports, Roush Fenway Racing, Richard Petty Motorsports, and Earnhardt Ganassi Racing. Numerous other tracks around North Carolina host races from low-tier NASCAR circuits as well.

Golf is a popular summertime leisure activity, and North Carolina has hosted several important professional golf tournaments. Pinehurst Resort in Pinehurst has hosted a PGA Championship, Ryder Cup, and two U.S. Open tournaments. The Wells Fargo Championship is a regular stop on the PGA Tour and is held at Quail Hollow Club in Charlotte, while the Wyndham Championship is played annually in Greensboro.

College sports are also popular in North Carolina, with 18 schools competing at the Division I level. The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) is headquartered in Greensboro, and both the ACC Football Championship Game (Charlotte) and the ACC Men's Basketball Tournament (Greensboro) were most recently held in North Carolina. College basketball in particular is very popular, buoyed by the Tobacco Road rivalries. The Belk Bowl is a post-season college football game held annually in Charlotte's Bank of America Stadium, featuring teams from the ACC and Big East conferences.

Tourism

In the Charlotte area, Carowinds amusement park, Charlotte Motor Speedway, U.S. National Whitewater Center, and the Discovery Place attract many tourists. Nearby Concord has the Concord Mills Mall and Great Wolf Lodge.

In the Conover – Hickory area, Hickory Motor Speedway, RockBarn Golf and Spa, home of the Greater Hickory Classic at Rock Barn, Catawba County Firefighters Museum, and SALT Block attract many tourists as Conover, and Hickory which has Valley Hills Mall.

The Appalachian Mountains attract several million tourists to the Western part of the state every year including the Biltmore Estate.

MerleFest in Wilkesboro attracts over 80,000 people within the four-day music festival. Wet 'n Wild Emerald Pointe in Greensboro also is a large tourist attraction.

The Outer Banks and surrounding beaches attract millions of people to the beaches every year.

Recreation

North Carolina provides a large range of recreational activities, from swimming at the beach[70] to skiing in the mountains. North Carolina offers fall colors, freshwater and saltwater fishing, hunting, birdwatching, agritourism, ATV trails, ballooning, rock climbing, biking, hiking, skiing, boating and sailing, camping, canoeing, caving (spelunking), gardens, and arboretums. North Carolina has theme parks, aquariums, zoos, museums, historic sites, lighthouses, elegant theaters, concert halls, and fine dining.[71]

North Carolinians enjoy outdoor recreation utilizing numerous local bike paths, 34 state parks, and 14 national parks which are the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, the Blue Ridge Parkway, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Cape Lookout National Seashore, Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site at Flat Rock, Croatan National Forest in Eastern North Carolina, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site at Manteo, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park in Greensboro, Moores Creek National Battlefield near Currie in Pender County, the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail, Old Salem National Historic Site in Winston-Salem, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, Wright Brothers National Memorial in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, Uwharrie National Forest.

Arts and culture

North Carolina has rich traditions in art, music, and cuisine. The nonprofit arts and culture industry generates $1.2 billion in direct economic activity in North Carolina, supporting more than 43,600 full-time equivalent jobs and generating $119 million in revenue for local governments and the state of North Carolina.[72] North Carolina established the North Carolina Museum of Art as the first major museum collection in the country to be formed by state legislation and funding[73] and continues to bring millions into the NC economy.[74] Also see this list of museums in North Carolina.

Music

North Carolina boasts a large number of noteworthy list of jazz musicians, some among the most important in the history of the genre. These include: John Coltrane (Hamlet), High Point); Thelonious Monk (Rocky Mount); Billy Taylor (Greenville); Woody Shaw(Laurinburg); Lou Donaldson (Durham); Max Roach (Newland); Tal Farlow (Greensboro); Albert, Jimmy and Percy Heath (Wilmington); Nina Simone (Tryon); and Billy Strayhorn (Hillsborough).

North Carolina is also famous for its tradition of old-time music, and many recordings were made in the early 20th century by folk song collector Bascom Lamar Lunsford. Musicians such as the North Carolina Ramblers helped solidify the sound of country music in the late 1920s, while the influential bluegrass musician Doc Watson also came from North Carolina. Both North and South Carolina are a hotbed for traditional rural blues, especially the style known as the Piedmont blues. Ben Folds Five originated in Winston-Salem, and Ben Folds still records and resides in Chapel Hill.

The Research Triangle area has long been a well-known center for folk, rock, metal, jazz and punk.[75] James Taylor grew up around Chapel Hill and his 1968 song "Carolina in My Mind" has been called an unofficial anthem for the state.[76][77][78] Other famous musicians from North Carolina include J. Cole, Shirley Caesar, Roberta Flack, Clyde McPhatter, Nnenna Freelon, Jimmy Herring, Michael Houser, Randy Travis, Ryan Adams, Ronnie Milsap and The Avett Brothers.

Metal and punk acts such as Corrosion of Conformity, Between the Buried and Me, and Nightmare Sonata are native to North Carolina.

Also, EDM producer Porter Robinson hails from Chapel Hill.

North Carolina is also the home state of more American Idol finalists than any other state. Clay Aiken (season two), Fantasia Barrino (season three), Kellie Pickler (season five), Bucky Covington (season five), Chris Daughtry (season five), Anoop Desai (season eight), and Scotty McCreery (season ten) all hail from the state.

In the mountains, the Brevard Music Center hosts choral, orchestral and solo performances during its annual summer schedule.

Also, see the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame.

Shopping

North Carolina has a variety of shopping choices. SouthPark Mall in Charlotte is currently the largest in the Carolinas and Tennessee with almost 2.0 million square feet. Other major malls in Charlotte include Northlake Mall and Carolina Place Mall in nearby suburb Pineville. Other major malls throughout the state include Hanes Mall in Winston-Salem, Crabtree Valley Mall, North Hills Mall, and Triangle Town Center in Raleigh, Friendly Center and Four Seasons Town Centre in Greensboro, Oak Hollow Mall in High Point, Concord Mills in Concord, Valley Hills Mall in Hickory, The Streets at Southpoint and Northgate Mall in Durham.

Cuisine and agriculture

A state culinary staple of North Carolina is pork barbecue. There are strong regional differences and rivalries over the sauces and method of preparation used in making the barbecue. The common trend across Western North Carolina is the use of Premium Grade Boston Butt, which is high in vitamins B1, B2, niacin (B3), B6, and selenium. Western North Carolina pork barbecue uses a tomato-based sauce, and only the pork shoulder (dark meat) is used. Western North Carolina barbecue is commonly referred to as Lexington barbecue after the Piedmont Triad town of Lexington, home of the Lexington Barbecue Festival which attracts over 100,000 visitors each October.[79][80] Eastern North Carolina pork barbecue uses a vinegar and red pepper based sauce and the "whole hog" is cooked, thus integrating both white and dark meat.

Krispy Kreme, an international chain of doughnut stores, was started in North Carolina; the company's headquarters are in Winston-Salem. Pepsi-Cola was first produced in 1898 in New Bern. A regional soft drink, Cheerwine, was created and is still based in the city of Salisbury. Despite its name, the hot sauce Texas Pete was created in North Carolina; its headquarters are also in Winston-Salem. The Hardee's fast-food chain was started in Rocky Mount. Another fast-food chain, Bojangles', was started in Charlotte, and has its corporate headquarters there. A popular North Carolina restaurant chain is Golden Corral. Started in 1973, the chain was founded in Fayetteville, with headquarters located in Raleigh. Popular pickle brand Mount Olive Pickle Company was founded in Mount Olive in 1926. Cook Out, a popular fast food chain featuring burgers, hot dogs, and milkshakes in a wide variety of flavors, was founded in Greensboro in 1989 and has begun expanding outside of North Carolina.

Over the last decade, North Carolina has become a cultural epicenter and haven for internationally prize-winning wine (Noni Bacca Winery), internationally prized cheeses (Ashe County), "L'institut International aux Arts Gastronomiques: Conquerront Les Yanks les Truffes, January 15, 2010" international hub for truffles (Garland Truffles), and beer making as tobacco land has been converted to grape orchards while state laws regulating alcohol content in beer allowed a jump in ABV from 6% to 15%. The Yadkin Valley in particular has become a strengthening market for grape production while the city of Asheville recently won the recognition of being named 'Beer City USA.' Asheville boasts the largest breweries per capita of any city in the United States. Recognized and marketed brands of beer in North Carolina include Highland Brewing, Duck Rabbit Brewery, Mother Earth Brewery, Weeping Radish Brewery, Big Boss Brewing, Foothills Brewing, Carolina Brewing Company and White Rabbit Brewing Company.

Tobacco was one of the first major industries to develop after the Civil War. Many farmers grew some tobacco, and the invention of the cigarette made the product especially popular. Winston-Salem is the birthplace of R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR), founded by R. J. Reynolds in 1874 as one of 16 tobacco companies in the town. By 1914 it was selling 425 million packs of Camels a year. Today it is the second-largest tobacco company in the U.S. (behind Altria Group). RJR is an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Reynolds American Inc. which in turn is 42% owned by British American Tobacco.[81]

Ships named for the state

Several ships have been named after the state. Most famous is the USS North Carolina, a World War II battleship. The ship served in several battles against the forces of Imperial Japan in the Pacific theater during the war. Now decommissioned, it is part of the USS North Carolina Battleship Memorial in Wilmington. Another USS North Carolina, a nuclear attack submarine, was commissioned in Wilmington, North Carolina on May 3, 2008.[82]

State parks

The state maintains a group of protected areas known as the North Carolina State Park System, which is managed by the North Carolina Division of Parks & Recreation (NCDPR), an agency of the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources (NCDENR).

State symbols

- State motto: Esse quam videri ("To be, rather than to seem") (1893)

- State song: "The Old North State" (1927)

- State flower: Dogwood (1941)

- State bird: Cardinal (1943)

- State colors: the red and blue of the N.C. and U.S. flags (1945)

- State toast: "The Tar Heel Toast" (1957)

- State tree: Longleaf Pine (1963)

- State shell: Scotch bonnet (1965)

- State mammal: Eastern Gray Squirrel (1969)

- State salt water fish: Red Drum (also known as the Channel bass) (1971)

- State insect: European honey bee (1973)

- State gemstone: Emerald (1973)

- State reptile: Eastern Box Turtle (1979)

- State rock: Granite (1979)

- State beverage: Milk (1987)

- State historical boat: Shad boat (1987)

- State language: English (1987)

- State dog: Plott Hound (1989)

- State military academy: Oak Ridge Military Academy (1991)

- State tartan: Carolina Tartan (1991)[83]

- State vegetable: Sweet potato (1995)

- State red berry: Strawberry (2001)

- State blue berry: Blueberry (2001)

- State fruit: Scuppernong grape (2001)

- State wildflower: Carolina Lily (2003)

- State Christmas tree: Fraser Fir (2005)

- State carnivorous plant: Venus Flytrap (2005)

- State folk dance: Clogging (2005)

- State popular dance: Carolina shag (2005)

- State birthplace of traditional pottery: the Seagrove area (2005)

- State sport: NASCAR (2011)[84]

Armed forces installations

According to former Governor Mike Easley, North Carolina is the "most military friendly state in the nation."[85] Fort Bragg, near Fayetteville, is a large and comprehensive military base and is the headquarters of the XVIII Airborne Corps, 82nd Airborne Division, and the U.S. Army Special Operations Command. Serving as the airwing for Fort Bragg is Pope Field also located near Fayetteville.

Located in Jacksonville Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune which, when combined with nearby bases Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Cherry Point, MCAS New River, Camp Geiger, Camp Johnson, Stone Bay and Courthouse Bay, makes up the largest concentration of Marines and sailors in the world. MCAS Cherry Point is home of the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing. Located in Goldsboro, Seymour Johnson Air Force Base is home of the 4th Fighter Wing and 916th Air Refueling Wing. One of the busiest air stations in the United States Coast Guard is located at the Coast Guard Air Station in Elizabeth City. Also stationed in North Carolina is the Military Ocean Terminal Sunny Point in Southport.

See also

- Index of North Carolina-related articles

- Outline of North Carolina – organized list of topics about North Carolina

References

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012" (CSV). 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. December 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Median Household Income, from U.S. Census Bureau (from 2007 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ^ "North Carolina". Modern Language Association. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ^ "North Carolina Climate and Geography". NC Kids Page. North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. May 8, 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ "North Carolina Counties Map". Quickfacts.census.gov. January 7, 2009. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "The Industrial History of North Carolina: A Research Guide". Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "The Growth of Research Triangle Park" (PDF). Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "Mount Mitchell State Park " History". Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge Coming Back to Beaufort". Beach Carolina Magazine. March 30, 2011.

- ^ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S Geological Survey. April 29, 2005. Retrieved November 6, 2006.

- ^ "Watersheds". NC Office of Environmental Education. February 16, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ John Hairr, The Great Hurricanes of North Carolina (2008) pp 139–150

- ^ "NOAA National Climatic Data Center". Retrieved October 24, 2006.

- ^ "NC residents band together after killer storms". News & Observer. April 21, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "Tornado outbreak is NC's most active on record". News & Observer. April 22, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ a b "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ^ Constance E. Richards, "Contact and Conflict", American Archaeologist, Spring 2008, p.14. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ Milton Ready, The Tar Heel State: A History of North Carolina (U. of South Carolina Press, 2005) pp 116, 120

- ^ "Chapter 5", 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission Report, North Carolina Dept. of Cultural Resources

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, p. 27. Retrieved March 10, 2008

- ^ Pildes (2000), "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", pp.12–13

- ^ Moore, David G.; Beck, Jr., Robin A.; Rodning, Christopher B. (March 2004). "Joara and Fort San Juan: culture contact at the edge of the world". Antiquity.ac.uk. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|author=and|last1=specified (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Constance E. Richards, "Contact and Conflict" Warren Wilson College, American Archaeologist, Spring 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ Randinelli, Tracey. Tanglewood Park. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt. p. 16. ISBN 0-15-333476-2.

- ^ "North Carolina State Library – North Carolina History". Statelibrary.dcr.state.nc.us. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Cherokee Indians". Uncpress.unc.edu. November 16, 1919. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ Russell Thornton (1990) "American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History since 1492". University of Oklahoma Press. p.79. ISBN 0-8061-2220-X

- ^ Fenn and Wood, Natives and Newcomers, pp. 24–25

- ^ Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries, p. 105

- ^ a b c d Lefler and Newsome, (1973)

- ^ Bethune, Lawrence E. "Scots to Colonial North Carolina Before 1775". Lawrence E. Bethune's M.U.S.I.C.s Project.

- ^ a b "Ancestry of the Population by State: 1980 – Table 3a – Persons Who Reported a Single Ancestry Group for Regions, Divisions and States" (PDF). Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ a b "Table 1. ''Type of Ancestry Response for Regions, Divisions and States: 1980" (PDF). Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ "Indentured Servitude in Colonial America". Webcitation.org. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ "Paul Heinegg, ''Free African Americans in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware''". Freeafricanamericans.com. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "The Great Seal of North Carolina". Netstate.com. Retrieved September 12, 2006. [dead link]

- ^ Stonestreet, Ottis C. IV, The Battle of Cowan's Ford: General Davidson's Stand on the Catawba River and its place in North Carolina History (CreateSpace Publishing 2012) ISBN 978-1-4680-7730-8 p. 3.

- ^ Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, 2005

- ^ John Hope Franklin, Free Negroes of North Carolina, 1789–1860, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1941, reprint, 1991

- ^ "NC Business History – Railroads". Historync.org. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Morris, Thomas D. (1999). Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619-1860. University of North Carolina Press. p. 172. ISBN 0807864307.

- ^ Historical Census Browser, 1860 US Census, University of Virginia[dead link]. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ "Center for Civic Education – Lincoln Bicentennial with Supplemental Lesson: Timeline". Civiced.org. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Highlights: Secession". Docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Today in History: June 8". Memory.loc.gov. April 9, 1959. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Civil War Facts About North Carolina". Classbrain.com. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ Resident Population Data. "Resident Population Data – 2010 Census". 2010.census.gov. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ American FactFinder – Results

- ^ Exner, Rich (June 3, 2012). "Americans under age 1 now mostly minorities, but not in Ohio: Statistical Snapshot". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ "2010 Census" (PDF). US Census. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ "City & Towns Totals: Vintage 2011 – U.S Census Bureau". Census.gov. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Population Estimates 2012 Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ "GDP by State". Greyhill Advisors. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ Economy at a Glance. For North Carolina. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2011.

- ^ "Site Selection Rankings". Greyhill Advisors. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "NC Department of Transportation Article: North Carolina's Future Rides on Us". NC Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ S. Spacek. "2011 American State Litter Scorecard: New Rankings for an Increasingly Environmentally Concerned Populous"

- ^ "North Carolina Public Schools". Ncpublicschools.org. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ News & Observer: Perdue's choice to lead state's school system takes office[dead link]

- ^ a b "NC Public School Facts". Ncpublicschools.org. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ http://proximityone.com/sd_nc.htm

- ^ The University of North Carolina. "Our 17 Institutions". Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ NCSU. "About NC State:Discovery begins at NC State". Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ http://www.igovacation.com/search_rentals/stateinfo.asp?State=nc

- ^ "What To Do Across North Carolina". VisitNC.com. 2006. Archived from the original on December 1, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ "North Carolina Arts Council".

- ^ "North Carolina Museum of Art Museum Backgrounder" (PDF).

- ^ "N.C. Museum of Art: Rembrandt Exhibit Pumped $13 Million Into Wake County Economy". SGR Today.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie (1999). Music USA: The Rough Guide. The Rough Guides. ISBN 1-85828-421-X.

- ^ "Hey, James Taylor – You've got a ... bridge?". Rome News-Tribune. May 21, 2002. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Hoppenjans, Lisa (October 2, 2006). "You must forgive him if he's ..." The News & Observer. Retrieved June 28, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Waggoner, Martha (October 17, 2008). "James Taylor to play 5 free NC concerts for Obama". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Garner, Bob (2007). Bob Garner's Guide to North Carolina Barbecue. John F. Blair, Publisher. ISBN 978-0-89587-254-8.

- ^ Craig, H. Kent (2006). "What is North Carolina-Style BBQ?". ncbbq.com. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Nannie M. Tilley, The R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (2009)

- ^ "USS North Carolina 'brought to life' again". WRAL-TV. May 3, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ "Secretary of State of North Carolina". Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ "NASCAR made North Carolina's official state sport". SportingNews.com. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ "Gov. easily vows to keep N.C. most military friendly state in the Nation" (Press release). State of North Carolina – Office of the Governor. May 13, 2006. Retrieved June 23, 2007.[dead link]

Further reading

- Clay, James, and Douglas Orr, eds., North Carolina Atlas: Portrait of a Changing Southern State 1971

- Christensen, Rob. The Paradox of Tar Heel Politics (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

- Cooper, Christopher A., and H. Gibbs Knotts, eds. The New Politics of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008)

- Crow; Jeffrey J. and Larry E. Tise; Writing North Carolina History (1979) onine

- Fleer; Jack D. North Carolina Government & Politics (1994) online political science textbook

- Hawks; Francis L. History of North Carolina 2 vol 1857

- Kersey, Marianne M., and Ran Coble, eds., North Carolina Focus: An Anthology on State Government, Politics, and Policy, 2d ed., (Raleigh: North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research, 1989).

- Lefler; Hugh Talmage. A Guide to the Study and Reading of North Carolina History (1963) online

- Lefler, Hugh Talmage, and Albert Ray Newsome, North Carolina: The History of a Southern State (1954, 1963, 1973), standard textbook

- Link, William A. North Carolina: Change and Tradition in a Southern State (2009), 481pp history by leading scholar

- Luebke, Paul. Tar Heel Politics: Myths and Realities (1990).

- Powell William S. Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Vol. 1, A-C; vol. 2, D-G; vol. 3, H-K. 1979–88.

- Powell, William S. North Carolina Fiction, 1734–1957: An Annotated Bibliography 1958

- Powell, William S. North Carolina through Four Centuries (1989), standard textbook

- Powell, William S. and Jay Mazzocchi, eds. Encyclopedia of North Carolina (2006) 1320pp; 2000 articles by 550 experts on all topics; ISBN 0-8078-3071-2. The best starting point for most research.

- Ready, Milton. The Tar Heel State: A History of North Carolina (2005) excerpt and text search

- WPA Federal Writers' Project. North Carolina: A Guide to the Old North State. 1939. famous WPA guide to every town

Primary sources

- Hugh Lefler, North Carolina History Told by Contemporaries (University of North Carolina Press, numerous editions since 1934)

- H. G. Jones, North Carolina Illustrated, 1524–1984 (University of North Carolina Press, 1984)

- North Carolina Manual, published biennially by the Department of the Secretary of State since 1941.

External links

- General

- History

- Government and education

- North Carolina state government

- North Carolina state library

- Energy & Environmental Data for North Carolina

- USGS real-time, geographic, and other scientific resources of North Carolina

- North Carolina facts from US Department of Agriculture ERS

- North Carolina Court System official site

- North Carolina facts from US Census Bureau

- NC ECHO – North Carolina Exploring Cultural Heritage Online

- North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Green 'N' Growing: The History of Home Demonstration and 4-H Youth Development in North Carolina – hosted by NCSU Libraries Special Collections Research Center

- NC Office of Archives and History

- Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina

- Driving Through Time: The Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina

- Other

Geographic data related to North Carolina at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to North Carolina at OpenStreetMap