Apollo

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

Apollo[a] is one of the Olympian deities in classical Greek and Roman religion and Greek and Roman mythology. The national divinity of the Greeks, Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, music and dance, truth and prophecy, healing and diseases, the Sun and light, poetry, and more. One of the most important and complex of the Greek gods, he is the son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. Seen as the most beautiful god and the ideal of the kouros (ephebe, or a beardless, athletic youth), Apollo is considered to be the most Greek of all the gods. Apollo is known in Greek-influenced Etruscan mythology as Apulu.[1]

As the patron deity of Delphi (Apollo Pythios), Apollo is an oracular god—the prophetic deity of the Delphic Oracle. Apollo is the god who affords help and wards off evil; various epithets call him the "averter of evil". Delphic Apollo is the patron of seafarers, foreigners and the protector of fugitives and refugees.

Medicine and healing are associated with Apollo, whether through the god himself or mediated through his son Asclepius. Apollo delivered people from epidemics, yet he is also a god who could bring ill-health and deadly plague with his arrows. The invention of archery itself is credited to Apollo and his sister Artemis. Apollo is usually described as carrying a golden bow and a quiver of silver arrows. Apollo's capacity to make youths grow is one of the best attested facets of his panhellenic cult persona. As the protector of young (kourotrophos), Apollo is concerned with the health and education of children. He presided over their passage into adulthood. Long hair, which was the prerogative of boys, was cut at the coming of age (ephebeia) and dedicated to Apollo.

Apollo is an important pastoral deity, and was the patron of herdsmen and shepherds. Protection of herds, flocks and crops from diseases, pests and predators were his primary duties. On the other hand, Apollo also encouraged founding new towns and establishment of civil constitution. He is associated with dominion over colonists. He was the giver of laws, and his oracles were consulted before setting laws in a city.

As the god of Mousike (art of Muses), Apollo presides over all music, songs, dance and poetry. He is the inventor of string-music, and the frequent companion of the Muses, functioning as their chorus leader in celebrations. The lyre is a common attribute of Apollo. In Hellenistic times, especially during the 5th century BCE, as Apollo Helios he became identified among Greeks with Helios, Titan god of the sun.[2] In Latin texts, however, there was no conflation of Apollo with Sol among the classical Latin poets until 1st century CE.[3] Apollo and Helios/Sol remained separate beings in literary and mythological texts until the 5th century CE.

Etymology

Apollo (Attic, Ionic, and Homeric Greek: Ἀπόλλων, Apollōn (GEN Ἀπόλλωνος); Doric: Ἀπέλλων, Apellōn; Arcadocypriot: Ἀπείλων, Apeilōn; Aeolic: Ἄπλουν, Aploun; Latin: Apollō)

The name Apollo—unlike the related older name Paean—is generally not found in the Linear B (Mycenean Greek) texts, although there is a possible attestation in the lacunose form ]pe-rjo-[ (Linear B: ]𐀟𐁊-[) on the KN E 842 tablet.[4][5][6]

The etymology of the name is uncertain. The spelling Ἀπόλλων (pronounced [a.pól.lɔːn] in Classical Attic) had almost superseded all other forms by the beginning of the common era, but the Doric form, Apellon (Ἀπέλλων), is more archaic, as it is derived from an earlier *Ἀπέλjων. It probably is a cognate to the Doric month Apellaios (Ἀπελλαῖος),[7] and the offerings apellaia (ἀπελλαῖα) at the initiation of the young men during the family-festival apellai (ἀπέλλαι).[8][9] According to some scholars, the words are derived from the Doric word apella (ἀπέλλα), which originally meant "wall," "fence for animals" and later "assembly within the limits of the square."[10][11] Apella (Ἀπέλλα) is the name of the popular assembly in Sparta,[10] corresponding to the ecclesia (ἐκκλησία). R. S. P. Beekes rejected the connection of the theonym with the noun apellai and suggested a Pre-Greek proto-form *Apalyun.[12]

Several instances of popular etymology are attested from ancient authors. Thus, the Greeks most often associated Apollo's name with the Greek verb ἀπόλλυμι (apollymi), "to destroy".[13] Plato in Cratylus connects the name with ἀπόλυσις (apolysis), "redemption", with ἀπόλουσις (apolousis), "purification", and with ἁπλοῦν ([h]aploun), "simple",[14] in particular in reference to the Thessalian form of the name, Ἄπλουν, and finally with Ἀειβάλλων (aeiballon), "ever-shooting". Hesychius connects the name Apollo with the Doric ἀπέλλα (apella), which means "assembly", so that Apollo would be the god of political life, and he also gives the explanation σηκός (sekos), "fold", in which case Apollo would be the god of flocks and herds.[15] In the ancient Macedonian language πέλλα (pella) means "stone,"[16] and some toponyms may be derived from this word: Πέλλα (Pella,[17] the capital of ancient Macedonia) and Πελλήνη (Pellēnē/Pallene).[18]

A number of non-Greek etymologies have been suggested for the name,[19] The Hittite form Apaliunas (dx-ap-pa-li-u-na-aš) is attested in the Manapa-Tarhunta letter,[20] perhaps related to Hurrian (and certainly the Etruscan) Aplu, a god of plague, in turn likely from Akkadian Aplu Enlil meaning simply "the son of Enlil", a title that was given to the god Nergal, who was linked to Shamash, Babylonian god of the sun.[21] The role of Apollo as god of plague is evident in the invocation of Apollo Smintheus ("mouse Apollo") by Chryses, the Trojan priest of Apollo, with the purpose of sending a plague against the Greeks (the reasoning behind a god of the plague becoming a god of healing is apotropaic, meaning that the god responsible for bringing the plague must be appeased in order to remove the plague).

The Hittite testimony reflects an early form *Apeljōn, which may also be surmised from comparison of Cypriot Ἀπείλων with Doric Ἀπέλλων.[22] The name of the Lydian god Qλdãns /kʷʎðãns/ may reflect an earlier /kʷalyán-/ before palatalization, syncope, and the pre-Lydian sound change *y > d.[23] Note the labiovelar in place of the labial /p/ found in pre-Doric Ἀπέλjων and Hittite Apaliunas.

A Luwian etymology suggested for Apaliunas makes Apollo "The One of Entrapment", perhaps in the sense of "Hunter".[24]

Greco-Roman epithets

Apollo's chief epithet was Phoebus (/ˈfiːbəs/ FEE-bəs; Φοῖβος, Phoibos Greek pronunciation: [pʰó͜i.bos]), literally "bright".[25] It was very commonly used by both the Greeks and Romans for Apollo's role as the god of light. Like other Greek deities, he had a number of others applied to him, reflecting the variety of roles, duties, and aspects ascribed to the god. However, while Apollo has a great number of appellations in Greek myth, only a few occur in Latin literature.

Sun

- Aegletes (/əˈɡliːtiːz/ ə-GLEE-teez; Αἰγλήτης, Aiglētēs), from αἴγλη, "light of the sun"[26]

- Helius (/ˈhiːliəs/ HEE-lee-əs; Ἥλιος, Helios), literally "sun"[27]

- Lyceus (/laɪˈsiːəs/ ly-SEE-əs; Λύκειος, Lykeios, from Proto-Greek *λύκη) "light". The meaning of the epithet "Lyceus" later became associated with Apollo's mother Leto, who was the patron goddess of Lycia (Λυκία) and who was identified with the wolf (λύκος).[28]

- Phanaeus (/fəˈniːəs/ fə-NEE-əs; Φαναῖος, Phanaios), literally "giving or bringing light"

- Phoebus (/ˈfiːbəs/ FEE-bəs; Φοῖβος, Phoibos), literally "bright", his most commonly used epithet by both the Greeks and Romans

- Sol (Roman) (/sɒl/), "sun" in Latin

Wolf

- Lycegenes (/laɪˈsɛdʒəniːz/ ly-SEJ-ən-eez; Λυκηγενής, Lukēgenēs), literally "born of a wolf" or "born of Lycia"

- Lycoctonus (/laɪˈkɒktənəs/ ly-KOK-tə-nəs; Λυκοκτόνος, Lykoktonos), from λύκος, "wolf", and κτείνειν, "to kill"

Origin and birth

Apollo's birthplace was Mount Cynthus on the island of Delos.

- Cynthius (/ˈsɪnθiəs/ SIN-thee-əs; Κύνθιος, Kunthios), literally "Cynthian"

- Cynthogenes (/sɪnˈθɒdʒɪniːz/ sin-THOJ-i-neez; Κυνθογενής, Kynthogenēs), literally "born of Cynthus"

- Delius (/ˈdiːliəs/ DEE-lee-əs; Δήλιος, Delios), literally "Delian"

- Didymaeus (/dɪdɪˈmiːəs/ did-i-MEE-əs; Διδυμαῖος, Didymaios) from δίδυμος, "twin") as Artemis' twin

Place of worship

Delphi and Actium were his primary places of worship.[29][30]

- Acraephius (/əˈkriːfiəs/ ə-KREE-fee-əs; Ἀκραίφιος, Akraiphios, literally "Acraephian") or Acraephiaeus (/əˌkriːfiˈiːəs/ ə-KREE-fee-EE-əs; Ἀκραιφιαίος, Akraiphiaios), "Acraephian", from the Boeotian town of Acraephia (Ἀκραιφία), reputedly founded by his son Acraepheus.[31]

- Actiacus (/ækˈtaɪ.əkəs/ ak-TY-ə-kəs; Ἄκτιακός, Aktiakos), literally "Actian", after Actium (Ἄκτιον)

- Delphinius (/dɛlˈfɪniəs/ del-FIN-ee-əs; Δελφίνιος, Delphinios), literally "Delphic", after Delphi (Δελφοί). An etiology in the Homeric Hymns associated this with dolphins.

- Epactaeus, meaning "god worshipped on the coast", in Samos.[32]

- Pythius (/ˈpɪθiəs/ PITH-ee-əs; Πύθιος, Puthios, from Πυθώ, Pythō), from the region around Delphi

- Smintheus (/ˈsmɪnθjuːs/ SMIN-thewss; Σμινθεύς, Smintheus), "Sminthian"—that is, "of the town of Sminthos or Sminthe"[33] near the Troad town of Hamaxitus[34]

Healing and disease

- Acesius (/əˈsiːʒəs/ ə-SEE-zhəs; Ἀκέσιος, Akesios), from ἄκεσις, "healing". Acesius was the epithet of Apollo worshipped in Elis, where he had a temple in the agora.[35]

- Acestor (/əˈsɛstər/ ə-SES-tər; Ἀκέστωρ, Akestōr), literally "healer"

- Culicarius (Roman) (/ˌkjuːlɪˈkæriəs/ KEW-li-KARR-ee-əs), from Latin culicārius, "of midges"

- Iatrus (/aɪˈætrəs/ eye-AT-rəs; Ἰατρός, Iātros), literally "physician"[36]

- Medicus (Roman) (/ˈmɛdɪkəs/ MED-i-kəs), "physician" in Latin. A temple was dedicated to Apollo Medicus at Rome, probably next to the temple of Bellona.

- Paean (/ˈpiːən/ PEE-ən; Παιάν, Paiān), physician, healer[37]

- Parnopius (/pɑːrˈnoʊpiəs/ par-NOH-pee-əs; Παρνόπιος, Parnopios), from πάρνοψ, "locust"

Founder and protector

- Agyieus (/əˈdʒaɪ.ɪjuːs/ ə-JY-i-yooss; Ἀγυιεύς, Aguīeus), from ἄγυια, "street", for his role in protecting roads and homes

- Alexicacus (/əˌlɛksɪˈkeɪkəs/ ə-LEK-si-KAY-kəs; Ἀλεξίκακος, Alexikakos), literally "warding off evil"

- Apotropaeus (/əˌpɒtrəˈpiːəs/ ə-POT-rə-PEE-əs; Ἀποτρόπαιος, Apotropaios), from ἀποτρέπειν, "to avert"

- Archegetes (/ɑːrˈkɛdʒətiːz/ ar-KEJ-ə-teez; Ἀρχηγέτης, Arkhēgetēs), literally "founder"

- Averruncus (Roman) (/ˌævəˈrʌŋkəs/ AV-ə-RUNG-kəs; from Latin āverruncare), "to avert"

- Clarius (/ˈklæriəs/ KLARR-ee-əs; Κλάριος, Klārios), from Doric κλάρος, "allotted lot"[38]

- Epicurius (/ˌɛpɪˈkjʊəriəs/ EP-i-KEWR-ee-əs; Ἐπικούριος, Epikourios), from ἐπικουρέειν, "to aid"[27]

- Genetor (/ˈdʒɛnɪtər/ JEN-i-tər; Γενέτωρ, Genetōr), literally "ancestor"[27]

- Nomius (/ˈnoʊmiəs/ NOH-mee-əs; Νόμιος, Nomios), literally "pastoral"

- Nymphegetes (/nɪmˈfɛdʒɪtiːz/ nim-FEJ-i-teez; Νυμφηγέτης, Numphēgetēs), from Νύμφη, "Nymph", and ἡγέτης, "leader", for his role as a protector of shepherds and pastoral life

- Sauroctunos, “lizard killer”, possibly a reference to his killing of Python

Prophecy and truth

- Coelispex (Roman) (/ˈsɛlɪspɛks/ SEL-i-speks), from Latin coelum, "sky", and specere "to look at"

- Iatromantis (/aɪˌætrəˈmæntɪs/ eye-AT-rə-MAN-tis; Ἰατρομάντις, Iātromantis,) from ἰατρός, "physician", and μάντις, "prophet", referring to his role as a god both of healing and of prophecy

- Leschenorius (/ˌlɛskɪˈnɔːriəs/ LES-ki-NOR-ee-əs; Λεσχηνόριος, Leskhēnorios), from λεσχήνωρ, "converser"

- Loxias (/ˈlɒksiəs/ LOK-see-əs; Λοξίας, Loxias), from λέγειν, "to say",[27] historically associated with λοξός, "ambiguous"

- Manticus (/ˈmæntɪkəs/ MAN-ti-kəs; Μαντικός, Mantikos), literally "prophetic"

Music and arts

- Musagetes (/mjuːˈsædʒɪtiːz/ mew-SAJ-i-teez; Doric Μουσαγέτας, Mousāgetās), from Μούσα, "Muse", and ἡγέτης "leader"[39]

- Musegetes (/mjuːˈsɛdʒɪtiːz/ mew-SEJ-i-teez; Μουσηγέτης, Mousēgetēs), as the preceding

Archery

- Aphetor (/əˈfiːtər/ ə-FEE-tər; Ἀφήτωρ, Aphētōr), from ἀφίημι, "to let loose"

- Aphetorus (/əˈfɛtərəs/ ə-FET-ər-əs; Ἀφητόρος, Aphētoros), as the preceding

- Arcitenens (Roman) (/ɑːrˈtɪsɪnənz/ ar-TISS-i-nənz), literally "bow-carrying"

- Argyrotoxus (/ˌɑːrdʒərəˈtɒksəs/ AR-jər-ə-TOK-səs; Ἀργυρότοξος, Argyrotoxos), literally "with silver bow"

- Hecaërgus (/ˌhɛkiˈɜːrɡəs/ HEK-ee-UR-gəs; Ἑκάεργος, Hekaergos), literally "far-shooting"

- Hecebolus (/hɪˈsɛbələs/ hi-SEB-əl-əs; Ἑκηβόλος, Hekēbolos), "far-shooting"

- Ismenius (/ɪzˈmiːniəs/ iz-MEE-nee-əs; Ἰσμηνιός, Ismēnios), literally "of Ismenus", after Ismenus, the son of Amphion and Niobe, whom he struck with an arrow

Amazons

- Amazonius (Ἀμαζόνιος), Pausanias at the Description of Greece writes that near Pyrrhichus there was a sanctuary of Apollo, called Amazonius (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζόνιος) with image of the god said to have been dedicated by the Amazons.[40]

Celtic epithets and cult titles

Apollo was worshipped throughout the Roman Empire. In the traditionally Celtic lands, he was most often seen as a healing and sun god. He was often equated with Celtic gods of similar character.[41]

- Apollo Atepomarus ("the great horseman" or "possessing a great horse"). Apollo was worshipped at Mauvières (Indre). Horses were, in the Celtic world, closely linked to the sun.[42]

- Apollo Belenus ('bright' or 'brilliant'). This epithet was given to Apollo in parts of Gaul, Northern Italy and Noricum (part of modern Austria). Apollo Belenus was a healing and sun god.[43]

- Apollo Cunomaglus ('hound lord'). A title given to Apollo at a shrine at Nettleton Shrub, Wiltshire. May have been a god of healing. Cunomaglus himself may originally have been an independent healing god.[44]

- Apollo Grannus. Grannus was a healing spring god, later equated with Apollo.[45][46][47]

- Apollo Maponus. A god known from inscriptions in Britain. This may be a local fusion of Apollo and Maponus.

- Apollo Moritasgus ('masses of sea water'). An epithet for Apollo at Alesia, where he was worshipped as god of healing and, possibly, of physicians.[48]

- Apollo Vindonnus ('clear light'). Apollo Vindonnus had a temple at Essarois, near Châtillon-sur-Seine in present-day Burgundy. He was a god of healing, especially of the eyes.[46]

- Apollo Virotutis ('benefactor of mankind?'). Apollo Virotutis was worshipped, among other places, at Fins d'Annecy (Haute-Savoie) and at Jublains (Maine-et-Loire).[47][49]

Origins

The cult centers of Apollo in Greece, Delphi and Delos, date from the 8th century BCE. The Delos sanctuary was primarily dedicated to Artemis, Apollo's twin sister. At Delphi, Apollo was venerated as the slayer of Pytho. For the Greeks, Apollo was all the gods in one and through the centuries he acquired different functions which could originate from different gods. In archaic Greece he was the prophet, the oracular god who in older times was connected with "healing". In classical Greece he was the god of light and of music, but in popular religion he had a strong function to keep away evil.[50] Walter Burkert[51] discerned three components in the prehistory of Apollo worship, which he termed "a Dorian-northwest Greek component, a Cretan-Minoan component, and a Syro-Hittite component."

From his eastern origin Apollo brought the art of inspection of "symbols and omina" (σημεῖα καὶ τέρατα : sēmeia kai terata), and of the observation of the omens of the days. The inspiration oracular-cult was probably introduced from Anatolia. The ritualism belonged to Apollo from the beginning. The Greeks created the legalism, the supervision of the orders of the gods, and the demand for moderation and harmony. Apollo became the god of shining youth, ideal beauty, fine arts, philosophy, moderation, spiritual-life, the protector of music, divine law and perceptible order. The improvement of the old Anatolian god, and his elevation to an intellectual sphere, may be considered an achievement of the Greek people.[52]

Healer and god-protector from evil

The function of Apollo as a "healer" is connected with Paean (Παιών-Παιήων), the physician of the gods in the Iliad, who seems to come from a more primitive religion.[53] Paeοn is probably connected with the Mycenaean pa-ja-wo-ne (Linear B: 𐀞𐀊𐀺𐀚),[54][55][56] but this is not certain. He did not have a separate cult, but he was the personification of the holy magic-song sung by the magicians that was supposed to cure disease. Later the Greeks knew the original meaning of the relevant song "paean" (παιάν). The magicians were also called "seer-doctors" (ἰατρομάντεις), and they used an ecstatic prophetic art which was used exactly by the god Apollo at the oracles.[57]

In the Iliad, Apollo is the healer under the gods, but he is also the bringer of disease and death with his arrows, similar to the function of the Vedic god of disease Rudra.[58] He sends a plague (λοιμός) to the Achaeans. The god who sends a disease can also prevent it; therefore, when it stops, they make a purifying ceremony and offer him a hecatomb to ward off evil. When the oath of his priest appeases, they pray and with a song they call their own god, the Paean.[59]

Some common epithets of Apollo as a healer are "paion" (παιών literally "healer" or "helper")[60] "epikourios" (ἐπικούριος, "succouring"), "oulios" (οὔλιος, "healer, baleful")[61] and "loimios" (λοίμιος, "of the plague"). In classical times, his strong function in popular religion was to keep away evil, and was therefore called "apotropaios" (ἀποτρόπαιος, "averting evil") and "alexikakos" (ἀλεξίκακος "keeping off ill"; from v. ἀλέξω + n. κακόν).[62] In later writers, the word, usually spelled "Paean", becomes a mere epithet of Apollo in his capacity as a god of healing.[63]

Homer illustrated Paeon the god and the song both of apotropaic thanksgiving or triumph.[64] Such songs were originally addressed to Apollo and afterwards to other gods: to Dionysus, to Apollo Helios, to Apollo's son Asclepius the healer. About the 4th century BCE, the paean became merely a formula of adulation; its object was either to implore protection against disease and misfortune or to offer thanks after such protection had been rendered. It was in this way that Apollo had become recognized as the god of music. Apollo's role as the slayer of the Python led to his association with battle and victory; hence it became the Roman custom for a paean to be sung by an army on the march and before entering into battle, when a fleet left the harbour, and also after a victory had been won.

Dorian origin

The connection with the Dorians and their initiation festival apellai is reinforced by the month Apellaios in northwest Greek calendars.[66] The family-festival was dedicated to Apollo (Doric: Ἀπέλλων).[67] Apellaios is the month of these rites, and Apellon is the "megistos kouros" (the great Kouros).[68] However it can explain only the Doric type of the name, which is connected with the Ancient Macedonian word "pella" (Pella), stone. Stones played an important part in the cult of the god, especially in the oracular shrine of Delphi (Omphalos).[69][70]

The "Homeric hymn" represents Apollo as a Northern intruder. His arrival must have occurred during the "Dark Ages" that followed the destruction of the Mycenaean civilization and his conflict with Gaia (Mother Earth) was represented by the legend of his slaying her daughter the serpent Python.[71]

The earth deity had power over the ghostly world and it is believed that she was the deity behind the oracle.[72] The older tales mentioned two dragons who were perhaps intentionally conflated. A female dragon named Delphyne (Δελφύνη; cf. δελφύς, "womb"),[73] and a male serpent Typhon (Τυφῶν; from τύφειν, "to smoke"), the adversary of Zeus in the Titanomachy, who the narrators confused with Python.[74][75] Python was the good daemon (ἀγαθὸς δαίμων) of the temple as it appears in Minoan religion,[76] but she was represented as a dragon, as often happens in Northern European folklore as well as in the East.[77]

Apollo and his sister Artemis can bring death with their arrows. The conception that diseases and death come from invisible shots sent by supernatural beings, or magicians is common in Germanic and Norse mythology.[58] In Greek mythology Artemis was the leader (ἡγεμών, "hegemon") of the nymphs, who had similar functions with the Nordic Elves.[78] The "elf-shot" originally indicated disease or death attributed to the elves, but it was later attested denoting stone arrow-heads which were used by witches to harm people, and also for healing rituals.[79]

The Vedic Rudra has some similar functions with Apollo. The terrible god is called "the archer" and the bow is also an attribute of Shiva.[80] Rudra could bring diseases with his arrows, but he was able to free people of them and his alternative Shiva is a healer physician god.[81] However the Indo-European component of Apollo does not explain his strong relation with omens, exorcisms, and with the oracular cult.

Minoan origin

It seems an oracular cult existed in Delphi from the Mycenaean age.[82] In historical times, the priests of Delphi were called Lab(r)yadai, "the double-axe men", which indicates Minoan origin. The double-axe, labrys, was the holy symbol of the Cretan labyrinth.[83][84] The Homeric hymn adds that Apollo appeared as a dolphin and carried Cretan priests to Delphi, where they evidently transferred their religious practices. Apollo Delphinios or Delphidios was a sea-god especially worshiped in Crete and in the islands.[85] Apollo's sister Artemis, who was the Greek goddess of hunting, is identified with Britomartis (Diktynna), the Minoan "Mistress of the animals". In her earliest depictions she is accompanied by the "Master of the animals", a male god of hunting who had the bow as his attribute. His original name is unknown, but it seems that he was absorbed by the more popular Apollo, who stood by the virgin "Mistress of the Animals", becoming her brother.[78]

The old oracles in Delphi seem to be connected with a local tradition of the priesthood and there is not clear evidence that a kind of inspiration-prophecy existed in the temple. This led some scholars to the conclusion that Pythia carried on the rituals in a consistent procedure through many centuries, according to the local tradition. In that regard, the mythical seeress Sibyl of Anatolian origin, with her ecstatic art, looks unrelated to the oracle itself.[86] However, the Greek tradition is referring to the existence of vapours and chewing of laurel-leaves, which seem to be confirmed by recent studies.[87]

Plato describes the priestesses of Delphi and Dodona as frenzied women, obsessed by "mania" (μανία, "frenzy"), a Greek word he connected with mantis (μάντις, "prophet").[88] Frenzied women like Sibyls from whose lips the god speaks are recorded in the Near East as Mari in the second millennium BC.[89] Although Crete had contacts with Mari from 2000 BC,[90] there is no evidence that the ecstatic prophetic art existed during the Minoan and Mycenean ages. It is more probable that this art was introduced later from Anatolia and regenerated an existing oracular cult that was local to Delphi and dormant in several areas of Greece.[91]

Anatolian origin

A non-Greek origin of Apollo has long been assumed in scholarship.[7] The name of Apollo's mother Leto has Lydian origin, and she was worshipped on the coasts of Asia Minor. The inspiration oracular cult was probably introduced into Greece from Anatolia, which is the origin of Sibyl, and where existed some of the oldest oracular shrines. Omens, symbols, purifications, and exorcisms appear in old Assyro-Babylonian texts, and these rituals were spread into the empire of the Hittites. In a Hittite text is mentioned that the king invited a Babylonian priestess for a certain "purification".[52]

A similar story is mentioned by Plutarch. He writes that the Cretan seer Epimenides purified Athens after the pollution brought by the Alcmeonidae and that the seer's expertise in sacrifices and reform of funeral practices were of great help to Solon in his reform of the Athenian state.[92] The story indicates that Epimenides was probably heir to the shamanic religions of Asia and proves, together with the Homeric hymn, that Crete had a resisting religion up to historical times. It seems that these rituals were dormant in Greece and they were reinforced when the Greeks migrated to Anatolia.

Homer pictures Apollo on the side of the Trojans, fighting against the Achaeans, during the Trojan War. He is pictured as a terrible god, less trusted by the Greeks than other gods. The god seems to be related to Appaliunas, a tutelary god of Wilusa (Troy) in Asia Minor, but the word is not complete.[93] The stones found in front of the gates of Homeric Troy were the symbols of Apollo. A western Anatolian origin may also be bolstered by references to the parallel worship of Artimus (Artemis) and Qλdãns, whose name may be cognate with the Hittite and Doric forms, in surviving Lydian texts.[94] However, recent scholars have cast doubt on the identification of Qλdãns with Apollo.[95]

The Greeks gave to him the name ἀγυιεύς agyieus as the protector god of public places and houses who wards off evil and his symbol was a tapered stone or column.[96] However, while usually Greek festivals were celebrated at the full moon, all the feasts of Apollo were celebrated at the seventh day of the month, and the emphasis given to that day (sibutu) indicates a Babylonian origin.[97]

The Late Bronze Age (from 1700 to 1200 BCE) Hittite and Hurrian Aplu was a god of plague, invoked during plague years. Here we have an apotropaic situation, where a god originally bringing the plague was invoked to end it. Aplu, meaning the son of, was a title given to the god Nergal, who was linked to the Babylonian god of the sun Shamash.[21] Homer interprets Apollo as a terrible god (δεινὸς θεός) who brings death and disease with his arrows, but who can also heal, possessing a magic art that separates him from the other Greek gods.[98] In Iliad, his priest prays to Apollo Smintheus,[99] the mouse god who retains an older agricultural function as the protector from field rats.[33][100][101] All these functions, including the function of the healer-god Paean, who seems to have Mycenean origin, are fused in the cult of Apollo.

Oracular cult

Unusually among the Olympic deities, Apollo had two cult sites that had widespread influence: Delos and Delphi. In cult practice, Delian Apollo and Pythian Apollo (the Apollo of Delphi) were so distinct that they might both have shrines in the same locality.[102] Lycia was sacred to the god, for this Apollo was also called Lycian.[103][104] Apollo's cult was already fully established when written sources commenced, about 650 BCE. Apollo became extremely important to the Greek world as an oracular deity in the archaic period, and the frequency of theophoric names such as Apollodorus or Apollonios and cities named Apollonia testify to his popularity. Oracular sanctuaries to Apollo were established in other sites. In the 2nd and 3rd century CE, those at Didyma and Claros pronounced the so-called "theological oracles", in which Apollo confirms that all deities are aspects or servants of an all-encompassing, highest deity. "In the 3rd century, Apollo fell silent. Julian the Apostate (359–361) tried to revive the Delphic oracle, but failed."[7]

Oracular shrines

Apollo had a famous oracle in Delphi, and other notable ones in Claros and Didyma. His oracular shrine in Abae in Phocis, where he bore the toponymic epithet Abaeus (Ἀπόλλων Ἀβαῖος, Apollon Abaios), was important enough to be consulted by Croesus.[105] His oracular shrines include:

- Abae in Phocis.

- Bassae in the Peloponnese.

- At Clarus, on the west coast of Asia Minor; as at Delphi a holy spring which gave off a pneuma, from which the priests drank.

- In Corinth, the Oracle of Corinth came from the town of Tenea, from prisoners supposedly taken in the Trojan War.

- At Khyrse, in Troad, the temple was built for Apollo Smintheus.

- In Delos, there was an oracle to the Delian Apollo, during summer. The Hieron (Sanctuary) of Apollo adjacent to the Sacred Lake, was the place where the god was said to have been born.

- In Delphi, the Pythia became filled with the pneuma of Apollo, said to come from a spring inside the Adyton.

- In Didyma, an oracle on the coast of Anatolia, south west of Lydian (Luwian) Sardis, in which priests from the lineage of the Branchidae received inspiration by drinking from a healing spring located in the temple. Was believed to have been founded by Branchus, son or lover of Apollo.

- In Hierapolis Bambyce, Syria (modern Manbij), according to the treatise De Dea Syria, the sanctuary of the Syrian Goddess contained a robed and bearded image of Apollo. Divination was based on spontaneous movements of this image.[106]

- At Patara, in Lycia, there was a seasonal winter oracle of Apollo, said to have been the place where the god went from Delos. As at Delphi the oracle at Patara was a woman.

- In Segesta in Sicily.

Oracles were also given by sons of Apollo.

- In Oropus, north of Athens, the oracle Amphiaraus, was said to be the son of Apollo; Oropus also had a sacred spring.

- in Labadea, 20 miles (32 km) east of Delphi, Trophonius, another son of Apollo, killed his brother and fled to the cave where he was also afterwards consulted as an oracle.

Temples of Apollo

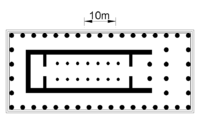

Many temples were dedicated to Apollo in Greece and the Greek colonies. They show the spread of the cult of Apollo and the evolution of the Greek architecture, which was mostly based on the rightness of form and on mathematical relations. Some of the earliest temples, especially in Crete, do not belong to any Greek order. It seems that the first peripteral temples were rectangular wooden structures. The different wooden elements were considered divine, and their forms were preserved in the marble or stone elements of the temples of Doric order. The Greeks used standard types because they believed that the world of objects was a series of typical forms which could be represented in several instances. The temples should be canonic, and the architects were trying to achieve this esthetic perfection.[107] From the earliest times there were certain rules strictly observed in rectangular peripteral and prostyle buildings. The first buildings were built narrowly in order to hold the roof, and when the dimensions changed some mathematical relations became necessary in order to keep the original forms. This probably influenced the theory of numbers of Pythagoras, who believed that behind the appearance of things there was the permanent principle of mathematics.[108]

The Doric order dominated during the 6th and the 5th century BC but there was a mathematical problem regarding the position of the triglyphs, which couldn't be solved without changing the original forms. The order was almost abandoned for the Ionic order, but the Ionic capital also posed an insoluble problem at the corner of a temple. Both orders were abandoned for the Corinthian order gradually during the Hellenistic age and under Rome.

The most important temples are:

Greek temples

- Thebes, Greece: The oldest temple probably dedicated to Apollo Ismenius was built in the 9th century B.C. It seems that it was a curvilinear building. The Doric temple was built in the early 7th century B.C., but only some small parts have been found[109] A festival called Daphnephoria was celebrated every ninth year in honour of Apollo Ismenius (or Galaxius). The people held laurel branches (daphnai), and at the head of the procession walked a youth (chosen priest of Apollo), who was called "daphnephoros".[110]

- Eretria: According to the Homeric hymn to Apollo, the god arrived to the plain, seeking for a location to establish its oracle. The first temple of Apollo Daphnephoros, "Apollo, laurel-bearer", or "carrying off Daphne", is dated to 800 B.C. The temple was curvilinear hecatombedon (a hundred feet). In a smaller building were kept the bases of the laurel branches which were used for the first building. Another temple probably peripteral was built in the 7th century B.C., with an inner row of wooden columns over its Geometric predecessor. It was rebuilt peripteral around 510 B.C., with the stylobate measuring 21,00 x 43,00 m. The number of pteron column was 6 x 14.[111][112]

- Dreros (Crete). The temple of Apollo Delphinios dates from the 7th century B.C., or probably from the middle of the 8th century B.C. According to the legend, Apollo appeared as a dolphin, and carried Cretan priests to the port of Delphi.[113] The dimensions of the plan are 10,70 x 24,00 m and the building was not peripteral. It contains column-bases of the Minoan type, which may be considered as the predecessors of the Doric columns.[114]

- Gortyn (Crete). A temple of Pythian Apollo, was built in the 7th century B.C. The plan measured 19,00 x 16,70 m and it was not peripteral. The walls were solid, made from limestone, and there was single door on the east side.

- Thermon (West Greece): The Doric temple of Apollo Thermios, was built in the middle of the 7th century B.C. It was built on an older curvilinear building dating perhaps from the 10th century B.C., on which a peristyle was added. The temple was narrow, and the number of pteron columns (probably wooden) was 5 x 15. There was a single row of inner columns. It measures 12.13 x 38.23 m at the stylobate, which was made from stones.[115]

- Corinth: A Doric temple was built in the 6th century B.C. The temple's stylobate measures 21.36 x 53.30 m, and the number of pteron columns was 6 x 15. There was a double row of inner columns. The style is similar with the Temple of Alcmeonidae at Delphi.[116] The Corinthians were considered to be the inventors of the Doric order.[115]

- Napes (Lesbos): An Aeolic temple probably of Apollo Napaios was built in the 7th century B.C. Some special capitals with floral ornament have been found, which are called Aeolic, and it seems that they were borrowed from the East.[117]

- Cyrene, Libya: The oldest Doric temple of Apollo was built in c. 600 B.C. The number of pteron columns was 6 x 11, and it measures 16.75 x 30.05 m at the stylobate. There was a double row of sixteen inner columns on stylobates. The capitals were made from stone.[117]

- Naukratis: An Ionic temple was built in the early 6th century B.C. Only some fragments have been found and the earlier, made from limestone, are identified among the oldest of the Ionic order.[118]

- Syracuse, Sicily: A Doric temple was built at the beginning of the 6th century B.C. The temple's stylobate measures 21.47 x 55.36 m and the number of pteron columns was 6 x 17. It was the first temple in Greek west built completely out of stone. A second row of columns were added, obtaining the effect of an inner porch.[119]

- Selinus (Sicily):The Doric Temple C dates from 550 B.C., and it was probably dedicated to Apollo. The temple's stylobate measures 10.48 x 41.63 m and the number of pteron columns was 6 x 17. There was portico with a second row of columns, which is also attested for the temple at Syracuse.[120]

- Delphi: The first temple dedicated to Apollo, was built in the 7th century B.C. According to the legend, it was wooden made of laurel branches. The "Temple of Alcmeonidae" was built in c. 513 B.C. and it is the oldest Doric temple with significant marble elements. The temple's stylobate measures 21.65 x 58.00 m, and the number of pteron columns as 6 x 15.[121] A fest similar with Apollo's fest at Thebes, Greece was celebrated every nine years. A boy was sent to the temple, who walked on the sacred road and returned carrying a laurel branch (dopnephoros). The maidens participated with joyful songs.[110]

- Chios: An Ionic temple of Apollo Phanaios was built at the end of the 6th century B.C. Only some small parts have been found and the capitals had floral ornament.[117]

- Abae (Phocis). The temple was destroyed by the Persians in the invasion of Xerxes in 480 B.C., and later by the Boeotians. It was rebuilt by Hadrian.[122] The oracle was in use from early Mycenaean times to the Roman period, and shows the continuity of Mycenaean and Classical Greek religion.[123]

- Bassae (Peloponnesus):A temple dedicated to Apollo Epikourios ("Apollo the helper"), was built in 430 B.C. and it was designed by Iktinos.It combined Doric and Ionic elements, and the earliest use of column with a Corinthian capital in the middle.[124] The temple is of a relatively modest size, with the stylobate measuring 14.5 x 38.3 metres[125] containing a Doric peristyle of 6 x 15 columns. The roof left a central space open to admit light and air.

- Delos: A temple probably dedicated to Apollo and not peripteral, was built in the late 7th century B.C., with a plan measuring 10,00 x 15,60 m. The Doric Great temple of Apollo, was built in c. 475 B.C. The temple's stylobate measures 13.72 x 29.78 m, and the number of pteron columns as 6 x 13. Marble was extensively used.[117]

- Ambracia: A Doric peripteral temple dedicated to Apollo Pythios Sotir was built in 500 B.C., and It is lying at the centre of the Greek city Arta. Only some parts have been found, and it seems that the temple was built on earlier sanctuaries dedicated to Apollo. The temple measures 20,75 x 44,00 m at the stylobate. The foundation which supported the statue of the god, still exists.[126]

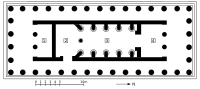

- Didyma (near Miletus): The gigantic Ionic temple of Apollo Didymaios started around 540 B.C. The construction ceased and then it was restarted in 330 B.C. The temple is dipteral, with an outer row of 10 x 21 columns, and it measures 28.90 x 80.75 m at the stylobate.[127]

- Clarus (near ancient Colophon): According to the legend, the famous seer Calchas, on his return from Troy, came to Clarus. He challenged the seer Mopsus, and died when he lost.[128] The Doric temple of Apollo Clarius was probably built in the 3rd century B.C., and it was peripteral with 6 x 11 columns. It was reconstructed at the end of the Hellenistic period, and later from the emperor Hadrian but Pausanias claims that it was still incomplete in the 2nd century B.C.[129]

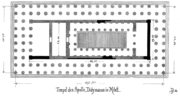

- Hamaxitus (Troad): In Iliad, Chryses the priest of Apollo, addresses the god with the epithet Smintheus (Lord of Mice), related with the god's ancient role as bringer of the disease (plague). Recent excavations indicate that the Hellenistic temple of Apollo Smintheus was constructed at 150–125 B.C., but the symbol of the mouse god was used on coinage probably from the 4th century B.C.[130] The temple measures 40,00 x 23,00 m at the stylobate, and the number of pteron columns was 8 x 14.[131]

- Pythion (Ancient Greek: Πύθιον), this was the name of a shrine of Apollo at Athens near the Ilisos river. It was created by Peisistratos, and tripods placed there by those who had won in the cyclic chorus at the Thargelia placed .[132]

Etruscan and Roman temples

- Veii (Etruria): The temple of Apollo was built in the late 6th century B.C. and it indicates the spread of Apollo's culture (Aplu) in Etruria. There was a prostyle porch, which is called Tuscan, and a triple cella 18,50 m wide.[133]

- Falerii Veteres (Etruria): A temple of Apollo was built probably in the 4th-3rd century B.C. Parts of a teraccotta capital, and a teraccotta base have been found. It seems that the Etruscan columns were derived from the archaic Doric.[133] A cult of Apollo Soranus is attested by one inscription found near Falerii.[134]

- Pompeii (Italy): The cult of Apollo was widespread in the region of Campania since the 6th century B.C. The temple was built in 120 B.V, but its beginnings lie in the 6th century B.C. It was reconstructed after an earthquake in A.D. 63. It demonstrates a mixing of styles which formed the basis of Roman architecture. The columns in front of the cella formed a Tuscan prostyle porch, and the cella is situated unusually far back. The peripteral colonnade of 48 Ionic columns was placed in such a way that the emphasis was given to the front side.[135]

- Rome: The temple of Apollo Sosianus and the temple of Apollo Medicus. The first temple building dates to 431 B.C., and was dedicated to Apollo Medicus (the doctor), after a plague of 433 B.C.[136] It was rebuilt by Gaius Sosius, probably in 34 B.C. Only three columns with Corinthian capitals exist today. It seems that the cult of Apollo had existed in this area since at least to the mid-5th century B.C.[137]

- Rome:The temple of Apollo Palatinus was located on the Palatine hill within the sacred boundary of the city. It was dedicated by Augustus on 28 B.C. The façade of the original temple was Ionic and it was constructed from solid blocks of marble. Many famous statues by Greek masters were on display in and around the temple, including a marble statue of the god at the entrance and a statue of Apollo in the cella.[138]

- Melite (modern Mdina, Malta): A Temple of Apollo was built in the city in the 2nd century A.D. Its remains were discovered in the 18th century, and many of its architectural fragments were dispersed among private collections or reworked into new sculptures. Parts of the temple's podium were rediscovered in 2002.[139]

Mythology

Apollo appears often in the myths, plays and hymns. As Zeus' favorite son, Apollo had direct access to the mind of Zeus and was willing to reveal this knowledge to humans. A divinity beyond human comprehension, he appears both as a beneficial and a wrathful god.

Birth

Apollo was the son of Zeus, the king of the gods, and Leto, his previous wife[140] or one of his mistresses. Growing up, Apollo was nursed by the nymphs Korythalia and Aletheia, the personification of truth.[141]

When Zeus' wife Hera discovered that Leto was pregnant, she banned Leto from giving birth on terra firma. Leto sought shelter in many lands, only to be rejected by them. Finally, the voice of unborn Apollo informed his mother about a floating island named Delos which had once been Asteria, Leto's own sister.[142] Since it was neither a mainland nor an island, Leto was readily welcomed there and gave birth to her children under a palm tree. All the goddesses except Hera were present to witness the event.

It is also stated that Hera kidnapped Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth, to prevent Leto from going into labor. The other gods tricked Hera into letting her go by offering her a necklace of amber 9 yards or 8.2 meters long.

When Apollo was born clutching a golden sword,[143] everything on Delos turned into gold, and the island was filled with ambrosial fragrance. Swans circled the island seven times, and the nymphs sang in delight.[142] He was washed clean by the goddesses who then covered him in white garment and fastened golden bands around him. Since Leto was unable to feed the him, Themis, the goddess of divine law, fed him with nectar, or ambrosia. Upon tasting the divine food, Apollo broke free of the bands fastened onto him and declared that he would be the master of lyre and archery, and interpret the will of Zeus to humankind.[144] Zeus, who had calmed Hera by the time, came and adorned his son with a golden headband.

Apollo's birth fixed the floating Delos to the earth.[145] Leto promised that her son would be always favorable towards the Delians. According to some, Apollo secured Delos to the bottom of the ocean after some time.[146][147] This island became sacred to Apollo and was one of the major cult centres of the god.

Apollo was born on the seventh day (ἑβδομαγενής, hebdomagenes)[148] of the month Thargelion —according to Delian tradition—or of the month Bysios—according to Delphian tradition. The seventh and twentieth, the days of the new and full moon, were ever afterwards held sacred to him.[15] Mythographers agree that Artemis was born first and subsequently assisted with the birth of Apollo, or that Artemis was born on the island of Ortygia and that she helped Leto cross the sea to Delos the next day to give birth to Apollo.

Hyperborea

Hyperborea, the mystical land of eternal spring, venerated Apollo above all the gods. The Hyperboreans always sang and danced in his honor and hosted Pythian games.[149] There, a vast forest of beautiful trees was called "the garden of Apollo". Apollo spent the winter months among the Hyperboreans.[150][151] His absence from the world caused coldness and this was marked as his annual death. No prophecies were issued during this time.[152] He returned to the world during the beginning of the spring. The Theophania festival was held in Delphi to celebrate his return.[153]

It is said that Leto came to Delos from Hyperborea accompanied by a pack of wolves. Henceforth, Hyperborea became Apollo's winter home and wolves became sacred to him. His intimate connection to wolves is evident from his epithet Lyceus, meaning wolf-like. But Apollo was also the wolf-slayer in his role as the god who protected flocks from predators. The Hyperborean worship of Apollo bears the strongest marks of Apollo being worshipped as the sun god. Shamanistic elements in Apollo's cult are often liked to his Hyperborean origin, and he is likewise speculated to have originated as a solar shaman.[154][155] Shamans like Abaris and Aristeas were also the followers of Apollo, who hailed from Hyperborea.

In myths, the tears of amber Apollo shed when his son Asclepius died became the waters of the river Eridanos, which surrounded Hyperborea. Apollo also buried in Hyperborea the arrow which he had used to kill the Cyclopes. He later gave this arrow to Abaris.[156]

Childhood and youth

As a child, Apollo is said to have built a foundation and an altar on Delos using the horns of the goats that his sister Artemis hunted. Since he learnt the art of building when young, he later came to be known as Archegetes, the founder (of towns)" and god who guided men to build new cities.[151] From his father Zeus, Apollo had also received a golden chariot drawn by swans.[157]

In his early years when Apollo spent his time herding cows, he was reared by Thriae, the bee nymphs, who trained him and enhanced his prophetic skills.[158] Apollo is also said to have invented the lyre, and along with Artemis, the art of archery. He then taught to the humans the art of healing and archery.[159] Phoebe, his grandmother, gave the oracular shrine of Delphi to Apollo as a birthday gift. Themis inspired him to be the oracular voice of Delphi thereon.[160][161]

Python

Python, a chthonic serpent-dragon, was a child of Gaea and the guardian of the Delphic Oracle, whose death was foretold by Apollo when he was still in Leto's womb.[151] Python was the nurse of the giant Typhon.[162] In most of the traditions, Apollo was still a child when he killed Python.

Python was sent by Hera to hunt the pregnant Leto to death, and had assaulted her. To avenge the trouble given to his mother, Apollo went in search of Python and killed it in the sacred cave at Delphi with the bow and arrows that he had received from Hephaestus. The Delphian nymphs who were present encouraged Apollo during the battle with the cry "Hie Paean". After Apollo was victorious, they also brought him gifts and gave the Corycian cave to him.[152][163] According to Homer, Apollo had encountered and killed the Python when he was looking for a place to establish his shrine.

According to another version, when Leto was in Delphi, Python had attacked her. Apollo defended his mother and killed Python.[164] Euripides in his Iphigenia in Aulis gives an account of his fight with Python and the events aftermath.

You killed him, o Phoebus, while still a baby, still leaping in the arms of your dear mother, and you entered the holy shrine, and sat on the golden tripod, on your truthful throne distributing prophecies from the gods to mortals.

A detailed account of Apollo's conflict with Gaea and Zeus' intervention on behalf of his young son is also given.

But when Apollo came and sent Themis, the child of Earth, away from the holy oracle of Pytho, Earth gave birth to dream visions of the night; and they told to the cities of men the present, and what will happen in the future, through dark beds of sleep on the ground; and so Earth took the office of prophecy away from Phoebus, in envy, because of her daughter. The lord made his swift way to Olympus and wound his baby hands around Zeus, asking him to take the wrath of the earth goddess from the Pythian home. Zeus smiled, that the child so quickly came to ask for worship that pays in gold. He shook his locks of hair, put an end to the night voices, and took away from mortals the truth that appears in darkness, and gave the privilege back again to Loxias.

Apollo also demanded that all other methods of divination be made inferior to his, a wish that Zeus granted him readily. Because of this, Athena, who had been practicing divination by throwing pebbles, cast her pebbles away in displeasure.[165]

However, Apollo had committed a blood murder and had to be purified. Because Python was a child of Gaea, Gaea wanted Apollo to be banished to Tartarus as a punishment.[166] Zeus didn't agree and instead exiled his son from Olympus, and instructed him to get purified. Apollo had to serve as a slave for nine years.[167] After the servitude was over, as per his father's order, he travelled to the Vale of Tempe to bath in waters of Peneus.[168] There Zeus himself performed purificatory rites on Apollo. Purified, Apollo was escorted by his half sister Athena to Delphi where the oracular shrine was finally handed over to him by Gaea.[169] According to a variation, Apollo had also travelled to Crete, where Carmanor purified him. Apollo later established the Pythian games to appropriate Gaea. Henceforth, Apollo became the god who cleansed himself from the sin of murder and, made men aware of their guilt and purified them.[170]

Soon after, Zeus instructed Apollo to go to Delphi and establish his law. But Apollo, disobeying his father, went to the land of Hyperborea and stayed there for a year.[171] He returned only after the Delphians sang hymns to him and pleaded him to come back. Zeus, pleased with his son's integrity, gave Apollo the seat next to him on his right side. He also gave to Apollo various gifts, like a golden tripod, a golden bow and arrows, a golden chariot and the city of Delphi.[172]

Soon after his return, Apollo needed to recruit people to Delphi. So, when he spotted a ship sailing from Crete, he sprang aboard in the form of a dolphin. The crew was awed into submission and followed a course that led the ship to Delphi. There Apollo revealed himself as a god. Initiating them to his service, he instructed them to keep righteousness in their hearts. The Pythia was Apollo's high priestess and his mouthpiece through whom he gave prophecies. Pythia is arguably the constant favorite of Apollo among the mortals.

Tityos

Hera once again sent another giant, Tityos to rape Leto. This time Apollo shot him with his arrows and attacked him with his golden sword. According to other version, Artemis also aided him in protecting their mother by attacking Tityos with her arrows.[173] After the battle Zeus finally relented his aid and hurled Tityos down to Tartarus. There, he was pegged to the rock floor, covering an area of 9 acres (36,000 m2), where a pair of vultures feasted daily on his liver.

Admetus

Admetus was the king of Pherae, who was known for his hospitality. When Apollo was exiled from Olympus for killing Python, he served as a herdsman under Admetus, who was then young and unmarried. Apollo is said to have shared a romantic relationship with Admetus during his stay.[174] After completing his years of servitude, Apollo went back to Olympus as a god.

Because Admetus had treated Apollo well, the god conferred great benefits on him in return. Apollo's mere presence is said to have made the cattle give birth to twins.[175][174] Apollo helped Admetus win the hand of Alcestis, the daughter of King Pelias,[176][177] by taming a lion and a boar to draw Admetus' chariot. He was present during their wedding to give his blessings. When Admetus angered the goddess Artemis by forgetting to give her the due offerings, Apollo came to the rescue and calmed his sister.[176] When Apollo learnt of Admetus' untimely death, he convinced or tricked the Fates into letting Admetus live past his time.[176][177]

According to another version, or perhaps some years later, when Zeus struck down Apollo's son Asclepius with a lightning bolt for resurrecting the dead, Apollo in revenge killed the Cyclopes, who had fashioned the bolt for Zeus.[175] Apollo would have been banished to Tartarus for this, but his mother Leto intervened, and reminding Zeus of their old love, pleaded him not to kill their son. Zeus obliged and sentenced Apollo to one year of hard labor once again under Admetus.[175]

The love between Apollo and Admetus was a favored topic of Roman poets like Ovid and Servius.

Niobe

The fate of Niobe was prophesied by Apollo while he was still in Leto's womb.[174] Niobe was the queen of Thebes and wife of Amphion. She displayed hubris when she boasted that she was superior to Leto because she had fourteen children (Niobids), seven male and seven female, while Leto had only two. She further mocked Apollo's effeminate appearance and Artemis' manly appearance. Leto, insulted by this, told her children to punish Niobe. Accordingly, Apollo killed Niobe's sons, and Artemis her daughters. According to some versions of the myth, among the Niobids, Chloris and her brother Amyclas were not killed because they prayed to Leto. Amphion, at the sight of his dead sons, either killed himself or was killed by Apollo after swearing revenge.

A devastated Niobe fled to Mount Sipylos in Asia Minor and turned into stone as she wept. Her tears formed the river Achelous. Zeus had turned all the people of Thebes to stone and so no one buried the Niobids until the ninth day after their death, when the gods themselves entombed them.

When Chloris married and had children, Apollo granted her son Nestor the years he had taken away from the Niobids. Hence, Nestor was able to live for 3 generations.[178]

Building the walls of Troy

Once Apollo and Poseidon served under the Trojan king Laomedon in accordance to Zeus' words. Apollodorus states that the gods willingly went to the king disguised as humans in order to check his hubris.[179] Apollo guarded the cattle of Laomedon in the valleys of mount Ida, while Poseidon built the walls of Troy.[180] Other versions make both Apollo and Poseidon the builders of the wall. In Ovid's account, Apollo completes his task by playing his tunes on his lyre.

In Pindar's odes, the gods took a mortal named Aeacus as their assistant.[181] When the work was completed, three snakes rushed against the wall, and though the two that attacked the sections of the wall built by the gods fell down dead, the third forced its way into the city through the portion of the wall built by Aeacus. Apollo immediately prophesied that Troy would fall at the hands of Aeacus's descendants, the Aeacidae (i.e. his son Telamon joined Heracles when he sieged the city during Laomedon's rule. Later, his great grandson Neoptolemus was present in the wooden horse that lead to the downfall of Troy).

However, the king not only refused to give the gods the wages he had promised, but also threatened to bind their feet and hands, and sell them as slaves. Angered by the unpaid labour and the insults, Apollo infected the city with a pestilence and Posedion sent the sea monster Cetus. To deliver the city from it, Laomedon had to sacrifice his daughter Hesione (who would later be saved by Heracles).

During his stay in Troy, Apollo had a lover named Ourea, who was a nymph and daughter of Poseidon. Together they had a son named Ileus, whom Apollo loved dearly.[182]

Trojan War

Apollo sided with the Trojans during the Trojan War waged by the Greeks against the Trojans.

During the war, the Greek king Agamemnon captured Chryseis, the daughter of Apollo's priest Chryses, and refused to return her. Angered by this, Apollo shot arrows infected with the plague into the Greek encampment. He demanded that they return the girl, and the Achaeans (Greeks) complied, indirectly causing the anger of Achilles, which is the theme of the Iliad.

Receiving the aegis from Zeus, Apollo entered the battlefield as per his father's command, causing great terror to the enemy with his war cry. He pushed the Greeks back and destroyed many of the soldiers. He is described as "the rouser of armies" because he rallied the Trojan army when they were falling apart.

When Zeus allowed the other gods to get involved in the war, Apollo was provoked by Poseidon to a duel. However, Apollo declined to fight him, saying that he wouldn't fight his uncle for the sake of mortals.

When the Greek hero Diomedes injured the Trojan hero Aeneas, Aphrodite tried to rescue him, but Diomedes injured her as well. Apollo then enveloped Aeneas in a cloud to protect him. He repelled the attacks Diomedes made on him and gave the hero a stern warning to abstain himself from attacking a god. Aeneas was then taken to Pergamos, a sacred spot in Troy, where he was healed.

After the death of Sarpedon, a son of Zeus, Apollo rescued the corpse from the battlefield as per his father's wish and cleaned it. He then gave it to Sleep (Hypnos) and Death (Thanatos). Apollo had also once convinced Athena to stop the war for that day, so that the warriors can relieve themselves for a while.

The Trojan hero Hector (who, according to some, was the god's own son by Hecuba[183]) was favored by Apollo. When he got severely injured, Apollo healed him and encouraged him to take up his arms. During a duel with Achilles, when Hector was about to lose, Apollo hid Hector in a cloud of mist to save him. When the Greek warrior Patroclus tried to get into the fort of Troy, he was stopped by Apollo. Encouraging Hector to attack Patroclus, Apollo stripped the armour of the Greek warrior and broke his weapons. Patroclus was eventually killed by Hector. At last, after Hector's fated death, Apollo protected his corpse from Achilles' attempt to mutilate it by creating a magical cloud over the corpse.

Apollo held a grudge against Achilles throughout the war because Achilles had murdered his son Tenes before the war began and brutally assassinated his son Troilus in his own temple. Not only did Apollo save Hector from Achilles, he also tricked Achilles by disguising himself as a Trojan warrior and driving him away from the gates. He foiled Achilles' attempt to mutilate Hector's dead body.

Finally, Apollo caused Achilles' death by guiding an arrow shot by Paris into Achilles' heel. In some versions, Apollo himself killed Achilles by taking the disguise of Paris.

Apollo helped many Trojan warriors, including Agenor, Polydamas, Glaucus in the battlefield. Though he greatly favored the Trojans, Apollo was bound to follow the orders of Zeus and served his father loyally during the war.

Heracles

After Heracles (then named Alcides) was struck with madness and killed his family, he sought to purify himself and consulted the oracle of Apollo. Apollo, through the Pythia, commanded him to serve king Eurystheus for twelve years and complete the ten tasks the king would give him. Only then would Alcides be absolved of his sin. Apollo also renamed him as Heracles.[184]

To complete his third task, Heracles had to capture the Ceryneian Hind, a hind sacred to Artemis, and bring it alive. He chased the hind for one year. When the animal eventually got tired and tried crossing the river Ladon, he captured it. While he was taking it back, he was confronted by Apollo and Artemis, who were angered at Heracles for this act. However, Heracles soothed the goddess and explained his situation to her. After much pleading, Artemis permitted him to take the hind and told him to return it later.

After he was freed from his servitude to Eurystheus, Heracles fell in conflict with Iphytus, a prince of Oechalia, and murdered him. Soon after, he contracted a terrible disease. He consulted the oracle of Apollo once again, in hope of ridding himself of the disease. The Pythia, however, denied to give any prophesy. In anger, Heracles snatched the sacred tripod and started walking away, intending to start his own oracle. However, Apollo did not tolerate this and stopped Heracles; a duel ensued between them. Artemis rushed to support Apollo, while Athena supported Heracles. Soon, Zeus threw his thunderbolt between the fighting brothers and separated them. He reprimanded Heracles for this act of violation and asked Apollo to give a solution to Heracles. Apollo then ordered the hero to serve under Omphale, queen of Lydia for one year in order to purify himself.

Periphas

Periphas was an Attican king and a priest of Apollo. He was noble, just and rich. He did all his duties justly. Because of this people were very fond of him and started honouring him to the same extent as Zeus. At one point, they worshipped Periphas in place of Zeus and set up shrines and temples for him. This annoyed Zeus, who decided to annihilate the entire family of Periphas. But because he was a just king and a good devotee, Apollo intervened and requested his father to spare Periphas. Zeus considered Apollo's words and agreed to let him live. But he metamorphosed Periphas into an eagle and made the eagle the king of birds. When Periphas' wife requested Zeus to let her stay with her husband, Zeus turned her into a vulture and fulfilled her wish.[185]

Plato's concept of soulmates

A long time ago, there were three kinds of human beings: male, descended from the sun; female, descended from the earth; and androgynous, descended from the moon. Each human being was completely round, with four arms and fours legs, two identical faces on opposite sides of a head with four ears, and all else to match. They were powerful and unruly. Otis and Ephialtes even dared to scale Mount Olympus.

To check their insolence, Zeus devised a plan to humble them and improve their manners instead of completely destroying them. He cut them all in two and asked Apollo to make necessary repairs, giving humans the individual shape they still have now. Apollo turned their heads and necks around towards their wounds, he pulled together their skin at the abdomen, and sewed the skin together at the middle of it. This is what we call navel today. He smoothened the wrinkles and shaped the chest. But he made sure to leave a few wrinkles on the abdomen and around the navel so that they might be reminded of their punishment.[186]

"As he [Zeus] cut them one after another, he bade Apollo give the face and the half of the neck a turn... Apollo was also bidden to heal their wounds and compose their forms. So Apollo gave a turn to the face and pulled the skin from the sides all over that which in our language is called the belly, like the purses which draw in, and he made one mouth at the centre [of the belly] which he fastened in a knot (the same which is called the navel); he also moulded the breast and took out most of the wrinkles, much as a shoemaker might smooth leather upon a last; he left a few wrinkles, however, in the region of the belly and navel, as a memorial of the primeval state.

Nurturer of the young

Apollo Kourotrophos is the god who nurtures and protects children and the young, especially boys. He oversees their education and their passage into adulthood. Education is said to have originated from Apollo and the Muses. Many myths have him train his children. It was a custom for boys to cut and dedicate their long hair to Apollo after reaching adulthood.

Chiron, the abandoned centaur, was fostered by Apollo, who instructed him in medicine, prophecy, archery and more. Chiron would later become a great teacher himself.

Asclepius in his childhood gained much knowledge pertaining to medicinal arts by his father. However, he was later entrusted to Chiron for further education.

Anius, Apollo's son by Rhoeo, was abandoned by his mother soon after his birth. Apollo brought him up and educated him in mantic arts. Anius later became the priest of Apollo and the king of Delos.

Iamus was the son of Apollo and Evadne. When Evadne went into labour, Apollo sent the Moirai to assist his lover. After the child was born, Apollo sent snakes to feed the child some honey. When Iamus reached the age of education, Apollo took him to Olympia and taught him many arts, including the ability to understand and explain the languages of birds.[187]

Idmon was educated by Apollo to be a seer. Even though he foresaw his death that would happen in his journey with the Argonauts, he embraced his destiny and died a brave death. To commemorate his son's bravery, Apollo commanded Boetians to build a town around the tomb of the hero, and to honor him.[188]

Apollo adopted Carnus, the abandoned son of Zeus and Europa. He reared the child with the help of his mother Leto and educated him to be a seer.

When his son Melaneus reached the age of marriage, Apollo asked the princess Stratonice to be his son's bride and carried her away from her home when she agreed.

Apollo saved a shepherd boy (name unknown) from death in a large deep cave, by the means of vultures. To thank him, the shepherd built Apollo a temple under the name Vulturius.[189]

God of music

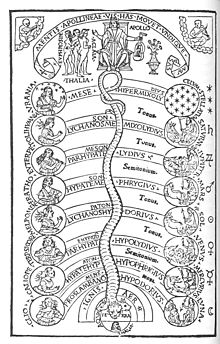

Immediately after his birth, Apollo demanded a lyre and invented the paean, thus becoming the god of music. As the divine singer, he is the patron of poets, singers and musicians. The invention of string music is attributed to him. Plato said that the innate ability of humans to take delight in music, rhythm and harmony is the gift of Apollo and the Muses.[190] According to Socrates, ancient Greeks believed that Apollo is the god who directs the harmony and makes all things move together, both for the gods and the humans. For this reason, he was called Homopolon before the Homo was replaced by A.[191][192] Apollo's harmonious music delivered people from their pain, and hence, like Dionysus, he is also called the liberator.[193] The swans, which were considered to be the most musical among the birds, were believed to be the "singers of Apollo". They are Apollo's sacred birds and acted as his vehicle during his travel to Hyperborea.[193] Aelian says that when the singers would sing hymns to Apollo, the swans would join the chant in unison.[194]

Among the Pythagoreans, the study of mathematics and music were connected to the worship of Apollo, their principal deity.[195][196][197] Their belief was that the music purifies the soul, just as medicine purifies the body. They also believed that music was delegated to the same mathematical laws of harmony as the mechanics of the cosmos, evolving into an idea known as the music of the spheres.[198]

Apollo appears as the companion of the Muses, and as Musagetes ("leader of Muses") he leads them in dance. They spend their time on Parnassus, which is one of their sacred places. Apollo is also the lover of the Muses and by them he became the father of famous musicians like Orpheus and Linus.

Apollo is often found delighting the immortal gods with his songs and music on the lyre.[199] In his role as the god of banquets, he was always present to play music in weddings of the gods, like the marriage of Eros and Psyche, Peleus and Thetis. He is a frequent guest of the Bacchanalia, and many ancient ceramics depict him being at ease amidst the maenads and satyrs.[200] Apollo also participated in musical contests when challenged by others. He was the victor in all those contests, but he tended to punish his opponents severely for their hubris.

Apollo's lyre

The invention of lyre is attributed either to Hermes or to Apollo himself.[201] Distinctions have been made that Hermes invented lyre made of tortoise shell, whereas the lyre Apollo invented was a regular lyre.[202]

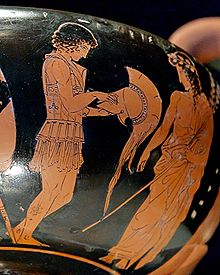

Myths tell that the infant Hermes stole a number of Apollo's cows and took them to a cave in the woods near Pylos, covering their tracks. In the cave, he found a tortoise and killed it, then removed the insides. He used one of the cow's intestines and the tortoise shell and made his lyre.

Upon discovering the theft, Apollo confronted Hermes and asked him to return his cattle. When Hermes acted innocent, Apollo took the matter to Zeus. Zeus, having seen the events, sided with Apollo, and ordered Hermes to return the cattle. Hermes then began to play music on the lyre he had invented. Apollo fell in love with the instrument and offered to exchange the cattle for the lyre. Hence, Apollo then became the master of the lyre.

According to other versions, Apollo had invented the lyre himself, whose strings he tore in repenting of the excess punishment he had given to Marsyas. Hermes' lyre, therefore, would be a reinvention.[203]

Contest with Pan

Once Pan had the audacity to compare his music with that of Apollo and to challenge the god of music to a contest. The mountain-god Tmolus was chosen to umpire. Pan blew on his pipes, and with his rustic melody gave great satisfaction to himself and his faithful follower, Midas, who happened to be present. Then, Apollo struck the strings of his lyre. It was so beautiful that Tmolus at once awarded the victory to Apollo, and everyone was pleased with the judgement. Only Midas dissented and questioned the justice of the award. Apollo did not want to suffer such a depraved pair of ears any longer, and caused them to become the ears of a donkey.

Contest with Marsyas

Marsyas was a satyr who was punished by Apollo for his hubris. He had found an aulos on the ground, tossed away after being invented by Athena because it made her cheeks puffy. Athena had also placed a curse upon the instrument, that whoever would pick it up would be severely punished. When Marsyas played the flute, everyone became frenzied with joy. This led Marsyas to think that he was better than Apollo, and he challenged the god to a musical contest. The contest was judged by the Muses, or the nymphs of Nysa. Athena was also present to witness the contest.

Marsyas taunted Apollo for "wearing his hair long, for having a fair face and smooth body, for his skill in so many arts".[204] He also further said,

'His [Apollo] hair is smooth and made into tufts and curls that fall about his brow and hang before his face. His body is fair from head to foot, his limbs shine bright, his tongue gives oracles, and he is equally eloquent in prose or verse, propose which you will. What of his robes so fine in texture, so soft to the touch, aglow with purple? What of his lyre that flashes gold, gleams white with ivory, and shimmers with rainbow gems? What of his song, so cunning and so sweet? Nay, all these allurements suit with naught save luxury. To virtue they bring shame alone!'[204]

The Muses and Athena sniggered at this comment. The contestants agreed to take turns displaying their skills and the rule was that the victor could "do whatever he wanted" to the loser.

According to one account, after the first round, they both were deemed equal by the Nysiads. But in the next round, Apollo decided to play on his lyre and add his melodious voice to his performance. Marsyas argued against this, saying that Apollo would have an advantage and accused Apollo of cheating. But Apollo replied that since Marsyas played the flute, which needed air blown from the throat, it was similar to singing, and that either they both should get an equal chance to combine their skills or none of them should use their mouths at all. The nymphs decided that Apollo's argument was just. Apollo then played his lyre and sang at the same time, mesmerising the audience. Marsyas could not do this. Apollo was declared the winner and, angered with Marsyas' haughtiness and his accusations, decided to flay the satyr.[205]

According to another account, Marsyas played his flute out of tune at one point and accepted his defeat. Out of shame, he assigned to himself the punishment of being skinned for a wine sack.[206] Another variation is that Apollo played his instrument upside down. Marsyas could not do this with his instrument. So the Muses who were the judges declared Apollo the winner. Apollo hung Marsyas from a tree to flay him.[207]

Apollo flayed the limbs of Marsyas alive in a cave near Celaenae in Phrygia for his hubris to challenge a god. He then gave the rest of his body for proper burial[208] and nailed Marsyas' flayed skin to a nearby pine-tree as a lesson to the others. Marsyas' blood turned into the river Marsyas. But Apollo soon repented and being distressed at what he had done, he tore the strings of his lyre and threw it away. The lyre was later discovered by the Muses and Apollo's sons Linus and Orpheus. The Muses fixed the middle string, Linus the string struck with the forefinger, and Orpheus the lowest string and the one next to it. They took it back to Apollo, but the god, who had decided to stay away from music for a while, laid away both the lyre and the pipes at Delphi and joined Cybele in her wanderings to as far as Hyperborea.[205][209]

Contest with Cinyras

Cinyras was a ruler of Cyprus, who was a friend of Agamemnon. Cinyras promised to assist Agamemnon in the Trojan war, but did not keep his promise. Agamemnon cursed Cinyras. He invoked Apollo and asked the god to avenge the broken promise. Apollo then had a lyre-playing contest with Cinyras, and defeated him. Either Cinyras committed suicide when he lost, or was killed by Apollo.[210][211]

Patron of sailors

Apollo functions as the patron and protector of sailors, one of the duties he shares with Poseidon. In the myths, he is seen helping heroes who pray to him for safe journey.

When Apollo spotted a ship of Cretan sailors that was caught in a storm, he quickly assumed the shape of a dolphin and guided their ship safely to Delphi.[212]

When the Argonauts faced a terrible storm, Jason prayed to his patron, Apollo, to help them. Apollo used his bow and golden arrow to shed light upon an island, where the Argonauts soon took shelter. This island was renamed "Anaphe", which means "He revealed it".[213]

Apollo helped the Greek hero Diomedes, to escape from a great tempest during his journey homeward. As a token of gratitude, Diomedes built a temple in honor of Apollo under the epithet Epibaterius ("the embarker").[214]

During the Trojan War, Odysseus came to the Trojan camp to return Chriseis, the daughter of Apollo's priest Chryses, and brought many offerings to Apollo. Pleased with this, Apollo sent gentle breezes that helped Odysseus return safely to the Greek camp.[215]

Arion was a poet who was kidnapped by some sailors for the rich prizes he possessed. Arion requested them to let him sing for the last time, to which the sailors consented. Arion began singing a song in praise of Apollo, seeking the god's help. Consequently, numerous dolphins surrounded the ship and when Arion jumped into the water, the dolphins carried him away safely.

Wars

Titanomachy

Once Hera, out of spite, aroused the Titans to war against Zeus and take away his throne. Accordingly, when the Titans tried to climb Mount Olympus, Zeus with the help of Apollo, Artemis and Athena, defeated them and cast them into tartarus.[216]

Trojan War

Apollo played a pivotal role in the entire Trojan War. He sided with the Trojans, and sent a terrible plague to the Greek camp, which indirectly led to the conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon. He killed the Greek heroes Patroclus, Achilles, and numerous Greek soldiers. He also helped many Trojan heroes, the most important one being Hector. After the end of the war, Apollo and Poseidon together cleaned the remains of the city and the camps.

Telegony war

A war broke out between the Brygoi and the Thesprotians, who had the support of Odysseus. The gods Athena and Ares came to the battlefield and took sides. Athena helped the hero Odysseus while Ares fought alongside of the Brygoi. When Odysseus lost, Athena and Ares came into a direct duel. To stop the battling gods and the terror created by their battle, Apollo intervened and stopped the duel between them .[217][218]

Indian war

When Zeus suggested that Dionysus defeat the Indians in order to earn a place among the gods, Dionysus declared war against the Indians and travelled to India along with his army of Bacchantes and satyrs. Among the warriors was Aristaeus, Apollo's son. Apollo armed his son with his own hands and gave him a bow and arrows and fitted a strong shield to his arm.[219] After Zeus urged Apollo to join the war, he went to the battlefield.[220] Seeing several of his nymphs and Aristaeus drowning in a river, he took them to safety and healed them.[221] He taught Aristaeus more useful healing arts and sent him back to help the army of Dionysus.

Theban war

During the war between the sons of Oedipus, Apollo favored Amphiaraus, a seer and one of the leaders in the war. Though saddened that the seer was fated to be doomed in the war, Apollo made Amphiaraus' last hours glorious by "lighting his shield and his helm with starry gleam". When Hypseus tried to kill the hero by a spear, Apollo directed the spear towards the charioteer of Amphiaraus instead. Then Apollo himself replaced the charioteer and took the reins in his hands. He deflected many spears and arrows away them. He also killed many of the enemy warriors like Melaneus, Antiphus, Aetion, Polites and Lampus. At last when the moment of departure came, Apollo expressed his grief with tears in his eyes and bid farewell to Amphiaraus, who was soon engulfed by the Earth.[222]

Slaying of giants

Apollo killed the giants Python and Tityos, who had assaulted his mother Leto.

Gigantomachy

During the gigantomachy, Apollo killed the giant Ephialtes by shooting him in his eyes. He also killed Porphyrion, the king of giants, using his bow and arrows.[223]

Aloadae