George Town, Penang

George Town

Tanjung Penaga | |

|---|---|

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | 乔治市 |

| • Tamil | ஜோர்ஜ் டவுன் |

Clockwise from top right: Penang Bridge, Eastern & Oriental Hotel, St. George's Church, George Town city centre and Jubilee Clock Tower. | |

| Nickname(s): Bandaraya Mutiara Pearl of the Orient City[1] | |

Location in Penang | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 11 August 1786 |

| Municipality established | 1857 |

| Granted city status | 1 January 1957[2] |

| Regain city status | 10 March 2015[3] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Patahiyah Ismail |

| Area | |

• City | 305.773 km2 (118.060 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,740.000 km2 (1,057.920 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 14 m (46 ft) |

| Population (2010) | |

• City | 500,000[6] |

| • Demonym | George Townians[7] |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | Not observed |

| Postal code | 10xxx to 14xxx |

| Area code(s) | 04 |

| Vehicle registration | P |

| Website | www |

George Town (Chinese: 乔治市; pinyin: Qiáozhì Shì, Tamil: ஜோர்ஜ் டவுன்) is the capital city of the Malaysian state of Penang, located on the north-east corner of the island. It had an estimated population of 500,000 as of 2010[update].[6] The metropolitan area (which consists of Jelutong, Sungai Pinang, Sungai Nibong, Gelugor, Air Itam, Tanjung Bungah and Tanjung Tokong) has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the second largest metropolitan area and the biggest northern metropolis in Malaysia.[8][9][10] Excluding the metropolitan area, the area of George Town is the seventh largest city by population in Malaysia.[note 1] Together with Alor Setar and Malacca City, it is one of the Malaysian oldest cities in the Straits of Malacca since its foundation by Francis Light, who was a captain and trader for the British East India Company (EIC) after being instructed by his company, Jourdain Sullivan and de Souza to establish presence in the Malay Archipelago.

Light gained control of Penang Island through a treaty negotiated with the Sultan of Kedah, although in the early stages of negotiation the Sultan refused to cede the island. The Fort Cornwallis was then established and he was successful in increasing the island import values and settlement population especially with the free trade policy the British used at the time. The Sultan of Kedah tried to regain control of the area when he saw the British had failed to provide protection to them as promised earlier in the treaty they had signed when the Sultan was attacked by the Siamese, the plan was however ended with a failure when Light implemented night raids on the Sultan's fortress. Prior to its successful trading post, many Chinese traders began to settle in the town as well to other areas in Penang Island to participate in agriculture and to manage plantations.[11][12] This was continued under the administration of Straits Settlements with the migration of more Chinese together with Indian workers prior to the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

The situation during the World War I did not directly impact the town daily activities, although the Imperial German Cruiser Emden sank a French destroyer and a Russian cruiser before shelling the oil storage tanks near the city in the Battle of Penang. During World War II, however, the town suffered greatly, since as it was heavily bombed first by the Japanese and later by the Allies. After the war, the town remained as the capital of Penang until the formation of Malaysia in 1963. In 2008, it was listed together with Malacca City as one of Malaysian UNESCO World Heritage Site for its long history as a cosmopolitan city.[13] Today, George Town is well known for its unique street foods, culture and heritage as well with its position as a medical tourism hub with many patients from neighbouring Sumatra in Indonesia frequently visiting the city to undergoing treatment.[14][15][16]

Etymology

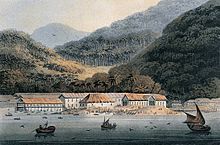

The George Town area was once known as Tanjung (Cape) in Malay language by the Malay community living there as it was situated on a cape area on the island northeast.[17] The name is derived from the older name of the town, Tanjung Penaga (Cape Penaigre).[18] As a settlement was soon established and founded by British Captain Francis Light in 1786, it was named after King George III.[17][19]

History

Founding of George Town

As the Dutch East India Company had dominated the Far East spice trade, the British were determined to establish their presence in the region to control the trade route between mainland China and the Indian subcontinent through the archipelago, and to set up a base to repair British Navy ships.[8][20] Because of this, Francis Light, who was a captain and a trader for the British East India Company (EIC) was instructed by his company, Jourdain Sullivan and de Souza in Madras, India to establish trade relations in the Malay archipelago.[21] He arrived on Penang Island on 17 July 1786.[20]

As Penang was still under the control of the Sultan of Kedah, Light needed to negotiate with the Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah to grant the island to the EIC in exchange for protection of the Sultanate against Siamese and Burmese intrusions.[21][22] The early negotiations were problematic because the Sultan did not want to cede the island to the British, but the threat from Siam grew as the five Malay kingdoms of Kedah, Perak, Terengganu, Kelantan and Pattani were forced to offer bunga mas annually as a sign of vassal state.[22] The Sultan was aware that he needed an agreement with the British for protection from the Siamese although he did not realise Light had acted without the approval of his superiors.[20] Following the sealing of agreements by both sides, Light returned to the island on 11 August 1786 to establish possession under the flag of the United Kingdom,[21] and renamed it Prince of Wales Island after George III who later became the King of the United Kingdom.[23]

At the time of his arrival, the island was inhabited by at least 1,000 Malay fishermen.[20] He then built Fort Cornwallis which became the first British presence in the Malay archipelago. The area of present-day George Town was developed from a swampy area. Light introduced the island to traders as a free port to attract them from the Dutch trading post in neighbouring Sumatra.[20] Although during the early stage of development he had difficulty in defending the island because of the shortage of water supply and because it was prone to flooding and malaria,[24][25] Light managed to increase the settlement population to 10,000 and the value of imports to £130,000.[26] In addition to Britain's free trade policy, Light also succeeded in attracting many traders from the Dutch ports in Sumatra where many restrictions and taxes had been imposed.[19]

After the company failed to provide military protection to the Sultanate of Kedah was attacked by Siam in 1790, the Sultan formed an army at Seberang Perai (later Province Wellesley) to remove the British as well some Dutch presence, to retake Prince of Wales Island. This action was defeated by Light who implemented night raids on the Sultan's fortress.[20] The following year, the Sultan was forced to signed a treaty with the British, which stipulated the official handing-over of the island to the British. Light was appointed Superintendent of the island and, to appease the Sultan, he paid $6,000 annually.[20][22] After Light died of malaria on 21 October 1794,[26] Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Wellesley arrived to defend and maintain British control of the island.[20] Sir George Alexander William Leith won control of another strip of land across the channel near the island in the Sultan of Kedah's territory in 1800, and named it Province Wellesley (present-day Seberang Perai). This gave the island control over the harbour and ended the problem of water shortage in the town. The annual payment to the Sultan of Kedah was increased to $10,000 after the acquisition and payment continues into the present.[20][22]

In 1805, the island was elevated from a colonial status to that of a residency on par with the cities of Madras and Bombay in India,[23] and by 1832, under the British administration in India, the Straits Settlements comprising the states of Malacca, Singapore and Penang was formed. Penang became its capital from 1826 and maintain its status as a free port but later in 1935 it was replaced by Singapore.[8][20][23] During this time, many Chinese traders began to settle to participate in agriculture and managing the plantations sector.[11][12] Although the town was increasingly developed, it became dangerous as it turns into a nest for Chinese secret societies who notorious for its gambling and brothels which resulting a violence when two rival sides of the secret societies came into fight in 1867 with each groups had allied themselves with similar Malay groups. Once the fight between them been resolved, each group was fined by the British authorities with a huge sum of $10,000 which later became the earlier cause for the establishment of police force in the island.[23] The island successfully developed under British rule and became a naval base for the British to protect its interest from Dutch and French.[12] At the end of the 19th century, prior to rich deposits of tin from neighbouring state and relentless demands of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, the island and the town enjoyed an economic boom. At this time, the town was overwhelmed by more immigrants especially those from China and India.[20] Many European planters and Chinese towkays (business leaders) generate their money in the plantations and mines sectors in other northern Malay states but built their homes and sent their children to school in the town.[20] The continuous town development was however halted when the Japanese arrived in 1941 as part of World War II.

World War, post-independence and present

During World War I, a surprise naval attack against the Allies occurred on 28 October 1914 in the town harbour area when the German cruiser SMS Emden disguised as the British cruiser HMS Yarmouth fired torpedos which sank the Russian cruiser Zhemchug. Subsequently the French destroyer Mousquet was also sunk. The engagement is known as the Battle of Penang. The attack resulted in 135 sailors killed while another 157 were wounded, mainly from the Russian and French side. Local Malay fishermen who were doing their daily activities not far from the area reportedly rushed to the site to save any sailors they could.[28]

At the start of World War II the Japanese landed in Kelantan on 8 December 1941. Following the Sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse on 10 December, Japanese forces launched airstrikes with their planes being sighted near George Town on 11 December.[29] The Japanese fighters and bombers arrived in V-formations. Amazed George Town residents emerged from their homes and places of business to see the unexpected aircraft formations, as has been described by Historian Allen Warren. The amazement, however, turned to horror as the populace saw the Japanese aircraft dropping bombs.[29] Exploding bombs hit buildings in the town, and some residents panicked, seeing the dead and injured in the streets and buildings on fire. Many residents began quickly to evacuate the town to save their lives. Looting was reported in the aftermath of the Japanese bombing.[29]

Eighty Japanese fighters and bombers had flown over Georgetown unopposed... Thousands of people had filled the streets to watch the spectacle, which turned to tragedy when the bombs began to fall. Aircraft had then wheeled down to dive-bomb and strafe. Mass panic was the result of the bombing, and Penang had no anti-aircraft guns and few air raid shelters. Most of the bombs fell by design on Georgetown's densely populated Chinatown...[30]

— Allen Warren, British historian.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

File:George Town, Penang (UNESCO).svg | |

| Location | Malaysia |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 1223 |

| Inscription | 2008 (32nd Session) |

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) No. 453 Squadron with sixteen-F2A Buffalo valiantly tried to counter the Japanese attacks, but met with failure. Many of the over-matched Australian pilots flying the obsolete and lumbering Buffalos were killed during dog-fights with the more agile Japanese fighter aircraft. The town burned for days following the Japanese bombing. An estimated 600 town residents were killed and another 1,100 wounded as a result of the Japanese attack.[29] The Japanese continued their advance with land attacks on 19 December, until on 22 December the first contingent of the Japanese land forces arrived to occupy the town as well as Penang Island. This marked the beginning of the Japanese occupation of Penang, and the incorporation of Penang as part of the Empire of Japan.[31]

The Japanese had constructed a small submarine base in Penang for joint use with German U-boats,[30] and during the extensive Southeast Asian Allied bombing campaign of November 1944 to May 1945, naval facilities in Penang as well as those in Singapore came under attack, and mines were dropped by aircraft to impede Axis shipping.[32] After the surrender of Japan in August 1945, and the end of the Japanese occupation of the peninsula, the British Military Administration set up a Settlement Advisory Council to revive its ties with the local residents.[33] On 1 April 1946, the Straits Settlements were dissolved and Penang was incorporated as part of the Malayan Union along with Malacca (Singapore became a separate crown colony). Subsequently, in 1948, these two former Straits Settlements entities and nine Malay States became part of the Federation of Malaya, which was geographically identical to the Union but embodied some political differences.

On 1 January 1957, a royal charter of Queen Elizabeth II awarded city status to the town.[2] Though the island of Penang had long enjoyed the status as a free port, this trading advantage was revoked in 1969, with a decidedly negative impact on Penang's commerce and employment.[23] Nevertheless, when the Federation of Malaya, together with North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore formed the Federation of Malaysia in 1963, the city generally enjoyed rapid economic growth, especially in important new industries such as electronics. George Town was maintained as the state capital of Penang.[23] It was listed as one of the historical cities in Malaysia, together with Malacca City on 7 July 2008.[13] When the George Town City Council was merged with the Penang Rural District Council to form a local government management board in 1974, the city lost its status as a sister city. The local government management board was replaced with Penang Municipal Council (MPPP) following the enforcement of Local Government Act in 1976.[4] The city regain its city status on 10 March 2015 after the Cabinet of Malaysia approves the request of city status for the whole Penang Island and a consent was given by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong.[3][34]

Capital city

Being the capital city of Penang, George Town plays an important role especially in the political and economic welfare of the population of the entire state. It is the seat of the state government where almost all of their ministries and agencies are based. Most of the Malaysian federal government agencies and departments are also located in George Town. The Penang State Legislative Assembly is located between Light Street and Farquhar Street near Fort Cornwallis. There are six members of parliament (MPs) representing the six parliamentary constituencies in the city as well for the whole island: Bukit Bendera (P.48), Tanjong (P.49), Jelutong (P.50), Bukit Gelugor (P.51), Bayan Baru (P.52) and Balik Pulau (P.53). The city also elects 19 representatives to the state legislature from the state assembly districts of Tanjong Bunga, Air Puteh, Kebun Bunga, Pulau Tikus, Padang Kota, Pengkalan Kota, Komtar, Datok Keramat, Sungai Pinang, Batu Lancang, Seri Delima, Air Itam, Paya Terubong, Batu Uban, Pantai Jerejak, Batu Maung, Bayan Lepas, Pulau Betong and Telok Bahang.[35]

Local authority and city definition

The authority of George Town was originally administer by the Municipal Council of George Town, which was established in 1857. Since the formation of Malaysia, it was changed to George Town City Council which then merged with the Penang Rural District Council to form the Penang Island Municipal Council in 1974.[4] In 2015, the municipal council status was upgraded into Penang Island City Council (Majlis Bandaraya Pulau Pinang).[34] Following the upgrade, the city area expands from 297 square kilometres to 305.773 square kilometres.[4] The present city council is now responsible for regulating traffic and parking, maintaining public parks, upkeeping cleanliness and drainage, managing waste disposal, issuing business licenses, and overseeing public health over the whole island of Penang. The current mayor of George Town is Patahiyah Ismail, who is also known as the first woman to be appointed as mayor in the city's mayor list.[4]

Geography

As Penang Island is only slightly ⅓ the size of Singapore with a population density of 2,559.7 square km,[36] it is one of the densest cities in Malaysia.[37] Almost entire of the city area have been extensively developed as a result of urban development. The contiguous hotel and resort belts of Tanjung Tokong, Batu Ferringhi and Tanjung Bungah along the northern beaches of Penang Island also form the northwestern edges of George Town. Meanwhile, the central hills, including Penang Hill, serve as a giant green lung for George Town and an important forested catchment area. With the shortage of land for more development, this has resulted more land reclamation projects been carried out to provide more low-lying land in high-demand areas.

Climate

The city features a tropical rainforest climate, under the Köppen climate classification (Af). As it is the norm for Malaysian cities with this climate, George Town experiences relatively consistent temperatures throughout the course of the year, with an average high temperature of about 32 °C (90 °F) and an average low of 21 °C (70 °F).[38] Its driest months are from December through February. The city sees on average around 2,477 millimetres (97.5 in) of precipitation annually with the lowest being 60 millimetres (2.4 in) in February while the highest was around 210 millimetres (8.3 in) between August and October.[39]

| Climate data for George Town | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 32 (89) |

32 (89) |

32 (89) |

32 (89) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

31 (87) |

31 (87) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

31 (87) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (76) |

24 (76) |

24 (76) |

24 (76) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

23 (74) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70 (2.8) |

90 (3.5) |

140 (5.5) |

230 (9.1) |

240 (9.4) |

170 (6.7) |

190 (7.5) |

240 (9.4) |

350 (13.8) |

390 (15.4) |

240 (9.4) |

110 (4.3) |

2,540 (100.0) |

| Source: Weatherbase[40] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

George Town people are commonly referred to as "George Townians".[7] The terms "G-Towns" and "G.T-ians" have also been used to a limited extent. While people from the whole Penang state are called Penangites.[41]

Ethnicity and religion

In 1911, the British Colonial Government Census reported the population of the city was at 101,182,[12] with the main race being the Chinese, followed by Malays, Indian- along with other bumiputras.[8] The Malaysian Census in 1970 reported the population had increased to 269,247 before decreasing to 198,298 in 2001 due to the rapid development of housing projects in Air Itam, Gelugor, Tanjong Bunga and Tanjong Tokong which attracted the city residents to migrate there.[12] In 2010, the census saw an increase with the population standing at 500,000.[6]

-

Kapitan Keling Mosque, the largest mosque in the city.

-

Church of the Assumption, founded after Francis Light landed on Penang Island, considered as the oldest Roman Catholic church in the city.

Languages

English has been the main language for the city community during the British colonial before being changed back to Malay after the formation of Malaysia.[42] Today, Malay is the main language that connecting every different ethnic backgrounds in George Town, with the city Malay was strongly influenced by Tamil speakers; especially for the Jawi Peranakan, it remains distinctly different from the Malay in the southern Malay Peninsula.[18] As the Chinese majority in the city are mainly Hoklo people, the city also has an own variation of Hokkien language called the Penang Hokkien.[43] While the main language spoken by Indian community is Malaysian Tamil dialect of Tamil language in addition to the country's official and national language Malaysian (English is also widely spoken and understood). Besides Tamil, Urdu is also spoken by a small number of Indian Muslims and Telugu as well as Punjabi is also spoken by ethnic Telugu and Punjabi community. However, young people are more interested in speaking English and English-Tamil mixture macaronic language, Tanglish. Ethnic Jawi Peranakan, a Muslim creole ethnic group of mixed Indian, Malay and Arab ancestry with predominantly Indian origin mostly use Malay as their first language in addition to English.[18][44] Another distinct group of Indian Muslims known as Mamak use the Penang Malay (northern slang) variant as their first and daily language.

Economy

Historically, the British established George Town as an entrepôt, where products from Britain and India such as opium, textile, steel, gunpowder, and iron goods, were sold to local merchants to be distributed throughout the Malay Archipelago.[12] Today, the city economy is dominated by the tertiary-based industry as George Town has been one of the centre of medical tourism in Malaysia with an estimated 1,000 tourists travel to the city every day for medical treatment in addition to Penang as the fifth-largest economy amongst the states and federal territories of Malaysia after Selangor, Kuala Lumpur, Johor and Sarawak,[37][45] Most of the patients are come from Sumatra in Indonesia,[15][16] with the sector have generating about 70% of the country medical tourism revenue.[46] In addition, secondary-based industry of manufacturing also take a presence with the city became the hub for electric and electronics manufacturing.[14]

Since 1800s, international banks, chiefly Standard Chartered,[47] HSBC, and the Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation, have opened branches in the city, with most of the banks still maintain their local headquarters on Beach Street, the historic commercial centre of George Town. Since the formation of Malaysia, more new banks have establish their presence, including ABN AMRO, Citibank, United Overseas Bank, Bank of China[48] and Bank Negara Malaysia (Malaysian central bank) together with other local banks such as the Public Bank, Maybank, Ambank and CIMB Bank.

Transport

The earliest modes of transportation in George Town was the horse hackney carriage which was popular throughout the last quarter of the 18th century until 1935, when the rickshaw gained popularity, until it in turn was rapidly superseded by the trishaw beginning in 1941.

Land

The city has an extensive road network since the British colonial rule. Outside the narrow streets of George Town, more modern roads link the city centre with the surrounding suburbs of Tanjung Tokong, Air Itam, Jelutong and Gelugor. The Jelutong Expressway connects the city to the Penang Bridge, the Bayan Lepas Free Industrial Zone and the Penang International Airport. As for the whole island, it is connected with the Malay Peninsula through the Penang Bridge and the Second Penang Bridge in the south area of the island, linking Batu Maung on the island with Batu Kawan on the mainland.

Public transport

The Rapid Penang is the sole bus company for the island of Penang. Almost every bus connects the city with other parts of the island, with Weld Quay being the main terminal while KOMTAR became the main hub. It is also operates a free daily bus service around the city, taking commuters and tourists on a drive along the heritage sites. Recently, open-air double decker buses, known as Hop-On Hop-Off buses, have been introduced for tourists.[49] Most of the express buses stop at the Sungai Nibong Bus Terminal at the southern suburbs of the city. There are several express bus companies operating round the clock, and the main destinations include Genting Highlands, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and southern Thailand. Since 2015, the Uber company has been actively engaging customers for taxis services.[50]

George Town also has numerous cycle rickshaws and trishaws plying its streets. As well with rental bicycles, which are being introduced and marketed by several companies in the city.[51] More efforts are now being carried out by the Penang state government to make the city as a cyclists' haven and a pedestrian-friendly city by introducing dedicated cycling lanes.[52] The only rail-based transportation in the city is the Penang Hill Railway, a funicular railway to the top of Penang Hill. Since it was completed in 1923, the railway underwent an extensive upgrading in 2010 and was reopened in early 2011.[53] Since the colonial period, the city has experienced different types of public transportation system with electric trams, trolleybuses and double-decker buses. The first steam tramway started operations in the 1880s, while electrical trams were launched in 1905. Trolleybuses commenced operations in 1925 and they gradually supplanted the trams. The George Town Municipal Transport (GTMT) operated both the trams and the trolleybuses. The GTMT is famous for having operated the smallest public service trolleybuses. In the 1950s, GTMT bought ex-London Transport trolleybuses. Despite having purchased new Sunbeam British trolleybuses in 1956-57, the system was abandoned in 1961.[54] The use of double-decker buses ceased in the 1970s when George Town Transport ceased to trade, the network being taken over by private-owned buses.

In 2015, there is a planning for the return of trams in the streets of George Town,[55] The Light Rail Transit (Penang Rapid Transit) was also proposed to be built from Komtar passing through the Penang International Airport and the suburbs of Air Itam, Paya Terubong and Tanjung Tokong,[56] as well with a cable car project linking Komtar to the Penang Sentral in Butterworth.[56][57]

Air

The Penang International Airport (PEN, ICAO: WMKP) is one of the oldest airports in Malaysia, being opened in 1935 when Penang was governed under Straits Settlements. It serves as the main airport for the northern part of Malaysia. The airport connects the city with major Asian cities of Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Bangkok, Jakarta, Guangzhou, Taipei and recently with a direct flights to Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) and Yangon.[58][59] It is also the hub for two Malaysian low-cost carriers of AirAsia and Firefly. As the second busiest Malaysian airport in terms of cargo traffic, it serves as an important cargo hub due to the large presence of multinational factories in the nearby Bayan Lepas Free Trade Zone.

Water

The Port of Penang is one of the major ports of Malaysia with four terminals - one on the city northeastern coast (Swettenham Pier) while three on the mainland Seberang Perai. With Malaysia being one of the largest exporting nations in the world, the Port of Penang plays an important role in the nation's shipping industry, linking the city to more than 200 ports worldwide.[60] The Swettenham Pier Port accommodates cruise ships as cruise tourism is one of the major industries in the city. The port serves as to bring tourists into and out of the city towards other regional destinations of Singapore and Phuket. The Penang Ferry Service connects the city with the half side of Penang of Butterworth on the Malay Peninsula, becoming the convenient mode of transportation for local residents to travelling by sea. It is the oldest ferry service in Malaysia since 1920 with four ferries ply the Penang Strait between George Town and Butterworth daily. Separate ferry services also connect the city with the island of Langkawi of Kedah to the north and the Indonesian city of Medan in Sumatra.

Other utilities

Courts of law and legal enforcement

The city high court complex is located along Light Highway,[61] along with the Sessions and Magistrate Courts.[61] While a court for Sharia law is located on Batu Gantung Road.[62] The Penang Police Contingent Headquarters is located on Penang Road,[63] together with the North East District police headquarters.[64] There are around fourteen police stations and six police substations (Pondok Polis) around the city.[64]

Health care

As George Town is one of the centre for medical tourism in Malaysia, it features many hospitals in both public and private. There are one public hospital, eight publics health clinic[65] and two child and mother health clinics[66] in George Town. The Penang General Hospital is one of the oldest and second largest hospital in Malaysia built in 1812 with around 1,198 beds until present.[67] The Lam Wah Ee Hospital in Jelutong established since 1883 is the oldest and largest private hospital with 700 beds.[68] The Island Hospital near Peel Highway is the second largest private hospital with 300 beds since 1996.[69] The Penang Adventist Hospital is the second oldest private hospital built in 1924, located in Burma Road with 253 beds.[70] The Loh Guan Lye Specialist Centre located in the heart of the city was established in 1975 and has around 273 beds.[71] The Pantai Hospital in Bayan Lepas has 200 beds.[72] The Gleneagles Medical Centre located in Burma Road was opened on 1 July 1973 with just 70 beds before expanding to a total of 132 beds in 1975.[73] Other private hospitals include the Mount Miriam Cancer Hospital in Tanjung Tokong with 40 beds and the Tropicana Medical Centre in Bayan Lepas with 24 beds, both located in the city suburbs.[74][75]

Education

Many government or state schools are available in the city. Some of the secondary schools include Penang Free School, St. Xavier's Institution, St. George's Girls' School, Methodist Boys' School, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Convent Green Lane, Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Convent Pulau Tikus and Convent Light Street.[76] There is also Chinese high schools like the Han Chiang High School, Phor Tay High School, Heng Ee High School, Penang Chinese Girls' High School, Convent Datuk Keramat, Chung Ling High School, Chung Hwa Confucian High School. The University of Science, Malaysia has its campus here and the Penang Medical College is known as the main medical college in the city. A number of other colleges and universities also has their campus such as the KDU University College (KDU),[77] SEGi College Penang,[78] Sentral College,[79] Olympia College,[80] INTI University College,[81] along with the state homegrown colleges of Equator Academy of Art and Han Chiang College and university like the Wawasan Open University. Beside that, the Penang Japanese (Supplementary) Saturday School (ペナン補習校, Penan Hoshūkō, PJSS), a supplementary Japanese school, holds its classes in the Moral Uplifting Society of Penang. Opened since January 2012, the Japanese school had six preschool and 25 primary students as of September 2013.[82]

Libraries

The Penang State Library Headquarters is located in Seberang Jaya of Seberang Perai. The city has its branch known as the George Town Branch Library, located in Scotland Road.[83][84] Other libraries or private libraries can be found in schools, colleges, or universities.

Culture and leisure

Attractions and recreational spots

Much of the attractions inside the city area is part of the Penang Heritage Trial.[85][86]

Cultural

As George Town is known as the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage City, there are a number of cultural venues. The Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion is an old mansion located at 14 Leith Street that was built in a traditional Hakka–Teochew architecture. The mansion was erected in the 1880s after a Hakka merchant from China, Cheong Fatt Tze commissioned its construction.[87] Another cultural attraction, the Cheah Kongsi is the first of five Penang Hokkien clan houses. Located in a block beside Khoo Kongsi, the clan house fuses Malay, traditional Straits Chinese and European cultural architectures. It was established in 1873 by Cheah Yam, an immigrant who came from the Sek Tong village in South China.[88] The Clan Jetties is a known Chinese settlements in the city. It was built after the construction of the Quay in 1882 with each jetty representing different clans due to constant rivalry over access and monopoly of work consignments. The jetties total are originally seven but one have destroyed by fire leaving it to six.[89]

Historical

The Fort Cornwallis is the main historical attraction as it is marking the founding of modern George Town city since the establishment by Francis Light. The Old Georgetown Streets is considered as the oldest heritage in Penang where Chinese and Indian cultures are presented. The area is where many Chinese shoplots, narrow roads, historical colonial-era mansions, clan houses, numerous schools, ornate temples and Little India districts are located.[90] Some historical religious buildings include the Kek Lok Si, Kong Hock Keong Temple, Han Jiang Ancestral Temple, Lebuh Aceh Mosque, Kapitan Keling Mosque, Nattukkottai Chettiar Temple, Sri Mahamariamman Temple, Church of the Assumption and the St. George's Church. Other historical attractions such as the Hainanese Mariners’ Lodge was built during the pre-World War II days when 49 Hainanese sailors pooled their resources to set up a common lodge and clubhouse they could stay,[91] while the Millionaire’s Row is used to be a European enclave during the British colonisation.[92]

Leisure and conservation areas

The main leisure attraction in the city is the Penang Botanic Gardens which featuring a lot of flower species and is the oldest gardens in the city. The gardens was establish by an English botanist Charles Curtis in 1884. Another nature attraction is the Penang Butterfly Farm which also showcases other insects and animals like beetles, lizards, frogs and snails.[93] The only main theme park in the city is the SIM Leisure Escape which opened since 2010.[94]

Other attractions

The Jubilee Clock Tower was built in 1897 and named after the Queen Victoria's 1897 Diamond Jubilee. The tower is sixty feet tall, with each foot representing a year of the Queen's 60-year reign. The P. Ramlee House located in P. Ramlee Road is the former house of the late Malaysian actor and singer P. Ramlee and is part of the state heritage.[95] The Penang Road feature a historical views of old shoplots starting from Farquhar Street into Gurdwara Road near the KOMTAR tower which also another attractions in the city.[96] The Penang Islamic Museum that was built in 1860 was once the residence of a powerful Acehnese pepper merchant. Near the Bahang Bay, located the Batik Factory that present cultural events and handicraft exhibitions.[97] The Penang’s Millionaires’ Row is one of two George Town grand heritage mansions together with Soonstead Mansion.[98]

The Penang Street Art in Armenian Street created by Lithuanian-artist Ernest Zacharevic is the main art attractions in the city, with the most popular graffiti featuring a children on a real bicycle and a boy on a real motorcycle.[99] The Penang State Museum and Art Gallery is also one of the oldest building since the British colonial time located in Farquhar Street. The Wonderfood Museum which located in Beach Street is a building where replica food made from synthetics, plastic, silicone and a mix of various chemicals and materials are displayed.[100] The Peranakan Mansion was once belong to Chung Keng Quee, a Kapitan from China who has a great influence to the Peranakan community.[101] The Sun Yat-sen Museum Penang in Armenian Street is another attraction that was known as the Southeast Asian base of progressive Chinese movement, the Tongmenghui. From this base Dr. Sun Yat-sen planned the Xinhai Revolution (Revolution of 1911).[25]

The Old Protestant Cemetery is the oldest Christian cemetery in the city that was maintained by the Penang Heritage Trust. The cemetery once served as a final resting place for a number of British administrators. Less than a mile away, the only Jewish cemetery in Malaysia is located between Burmah Road and Macalister Road behind high walls; the gates are locked most of the time, as the Jewish community in Penang is all but gone.[102]

Shopping

George Town is the main shopping destination in northern Malaysia due to its fast development with many new skyscrapers. While many newest landmarks have started to dominate the city, many centuries-old shophouses are still operating alongside flea markets. Since 2001, the city had a high supply of shophouses. In comparison, shopping complexes in George Town registered the biggest increases in Malaysia.[103] This increase can be seen in the many shopping malls in George Town, such as Gurney Plaza, 1st Avenue and Gurney Paragon. The combination of both old and new creates a unique bustling retail sector in George Town.[104]

Entertainment

There are four cinemas located in the city, with the largest is the Gurney Plaza cinema with 1,618 seats. The cinemas are either owned by Golden Screen Cinemas, TGV Cinemas and Lotus Five Star.

Sports

The city main football stadium, City Stadium has a capacity of around 40,000.[105] The stadium is the home ground of Penang FA.

International relations

Several countries have set up their consulates in George Town, including Australia,[106] Austria,[107] Canada,[107] China,[108] Denmark,[107] Finland,[107] Germany,[107] Indonesia,[109] Japan,[110] Poland,[111] Russia,[107] Sweden,[107] Thailand,[112] and the United Kingdom.[113]

Twin towns – Sister cities

George Town has six sister cities:

See also

Notes

- ^ Excluding the population in the whole administration area of Penang Island City Council, the city stand as the seventh largest city in Malaysia.

- ^ The new cenotaph is built in 11 November 1948 as a replaceable to an earlier cenotaph that have been destroyed by both the Japanese and Allied bombings in World War II.

References

- ^ Mike Aquino (30 August 2012). "Exploring Georgetown, Penang". Asian Correspondent. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ a b Goh Ban Lee (19 May 2014). "The Penang Island City agenda". The Sun. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ a b Looi Sue-Chern (24 March 2015). "George Town a city again". The Malaysian Insider. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Cavina Lim (25 March 2015). "Penang's first mayor a woman". The Star. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "Malaysia Elevation Map (Elevation of George Town)". Flood Map : Water Level Elevation Map. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Looking for a 2016 vacation? Here are 16 must-see destinations". Los Angeles Times. 26 December 2015. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Toni Marie Ford. "Penang Beach Holiday". Tropical Sky. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Usman Haji Yaakob; Nik Norliati Fitri Md Nor (2013). "The Process and Effects of Demographic Transition in Penang, Malaysia" (PDF). School of Humanities. University of Science, Malaysia. pp. 42, 45 6, 9/28. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Homi Kharas; Albert Zeufack; Hamdan Majeed (September 2010). "Cities, People & the Economy — A Study on Positioning Penang" (PDF). Khazanah Nasional, World Bank. ThinkCity. pp. 5, 12/105. ISBN 978-983-44193-3-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hamdan Abdul Majeed (11 April 2012). "Urban Regeneration : The Case of Penang, Malaysia (Putting Policy into Practice) - The Penang Metropolitan Region (George Town Conurbation)" (PDF). Khazanah Nasional. World Bank. pp. 10/20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wang Gungwu (7 April 2003). Anglo-Chinese Encounters Since 1800: War, Trade, Science and Governance. Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0-521-53413-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Usman Yaakob; Tarmiji Masron; Fujimaki Masami (11 October 2015). "Ninety Years of Urbanization in Malaysia: A Geographical Investigation of Its Trends and Characteristics" (PDF). University of Science, Malaysia and Ritsumeikan University, Japan. Ritsumeikan. pp. 90, 99/23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Eight new sites, from the Straits of Malacca, to Papua New Guinea and San Marino, added to UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO (World Heritage Site). 7 July 2008. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Christina Oon Khar Ee; Khoo Suet Leng (2004). "Issues and challenges of a liveable and creative city: The case of Penang, Malaysia" (PDF). Development Planning and Management Programme, School of Social Sciences, University of Science, Malaysia. p. 1/11. ISSN 2180-2491. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wardah Fajri (17 February 2014). "Mengapa Pasien Puas Berobat ke Penang?" (in Indonesian). Kompas. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Tamasya ke George Town" (in Indonesian). Aceh Kita. 29 October 2013. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Abu Talib Ahmad (10 October 2014). Museums, History and Culture in Malaysia. NUS Press. pp. 233–. ISBN 978-9971-69-819-5.

- ^ a b c Editor Muhammad Haji Salleh (27 August 2015). Early History of Penang (Penerbit USM). Penerbit USM. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-983-861-657-7.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Ashley Jackson (November 2013). Buildings of Empire. OUP Oxford. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-19-958938-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "History of Penang". Penang State Government. 14 September 2008. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "The Penang connection". The Hindu. 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Swettenham; Frank Athelstane (1850–1946). "Map to illustrate the Siamese question". W. & A.K. Johnston Limited. University of Michigan Library. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Simon Richmond (2010). Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei. Lonely Planet. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-1-74104-887-2.

- ^ Robert K. Home (2013). Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities. Routledge. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-415-54053-7.

- ^ a b c Streets of George Town, Penang. Areca Books. 2007. pp. 5–85. ISBN 978-983-9886-00-9.

- ^ a b Walter Makepeace; Gilbert E. Brooke; Roland St. J. Braddell; John Murray. "One hundred years of Singapore : being some account of the capital of the Straits Settlements from its foundation by Sir Stamford Raffles on the 6th February 1819 to the 6th February 1919". Library Bureau, University of Toronto Libraries. Internet Archive. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ Jin Seng Cheah (19 February 2013). Penang 500 Early Postcards. Editions Didier Millet. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-967-10617-1-8.

- ^ Ajay Kamalakaran (20 May 2015). "Battle of Penang: When Malay fishermen rescued Russian sailors". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Alan Warren (2006). Britain's Greatest Defeat: Singapore 1942. A&C Black. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-1-85285-597-0.

- ^ a b Nick Shepley (7 December 2015). Red Sun at War Part II: Allied Defeat in the Far East. Andrews UK Limited. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-1-78166-301-1.

- ^ Salma Nasution Khoo; Alison Hayes; Sehra Yeap Zimbulis (2010). Giving Our Best: The Story of St. George's Girls' School, Penang, 1885-2010. Areca Books. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-967-5719-04-2.

- ^ Paul H. Kratoska (1998). The Japanese Occupation of Malaya: A Social and Economic History. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 296–. ISBN 978-1-85065-284-7.

- ^ Kim Hong Tan (2007). 檳榔嶼華人史圖錄 (in Chinese). Areca Books. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-983-42834-7-6.

- ^ a b Himanshu Bhatt (17 December 2014). "Cabinet approves city status for Penang island". The Malaysian Insider. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "List of Parliamentary Elections Parts and State Legislative Assemblies on Every States". Ministry of Information Malaysia. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hairunnisa Md Arus; Dr. Mohd Effendi Daud; Najihah Remali (13–14 December 2012). "Seminar Teknikal Kebangsaan Gempa Bumi dan Tsunami (Study Area) — Implementing Thematic Indices Combination Technique for Tsunami Vulnerability Mapping in West Coast of Peninsula Malaysia using High-Resolution Imagery" (PDF). Faculty of Engineering and Environment, Tun Hussein Onn University of Malaysia, Penang State Government (in English and Malay). Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: Malaysian Meteorological Department. pp. 7/41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Nathaniel Fernandez (26 July 2014). "Making Penang more liveable". The Star. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Difussion of Useful Knowledge. Charles Knight. 1840. pp. 400–.

- ^ Tijs Neutens; Philippe de Maeyer (16 October 2009). Developments in 3D Geo-Information Sciences. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-3-642-04791-6.

- ^ "Weatherbase — George Town". Weatherbase. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Wong Chun Wai (11 October 2015). "Proud of being multiracial". The Star. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Dr. Leo Semashko and 75 GHA co-authors from 26 countries (2013). The ABC of Harmony: for World Peace, Harmonious Civilization and Tetranet Thinking: Global Textbook. Lulu.com. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-1-304-11284-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Teh Chee Jye; Dr. Lim Yong Long (February 2014). "An Alternative Architectural Strategy to Preserve the Living Heritage and Identity of Penang Hokkien Language in Malaysia" (PDF). International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Built Environment. University of Technology, Malaysia. pp. 243, 1/6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 29 January 2016 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Naidu Ratnala Thulaja (13 January 2005). "Jawi Peranakan community". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Imran Hilmy (5 December 2014). "Penang accounts for 50% of medical tourists". The Sun. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ OECD (29 March 2011). Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Development: State of Penang, Malaysia 2011. OECD Publishing. pp. 87–. ISBN 978-92-64-08945-7.

- ^ "About Us – Standard Chartered Bank Malaysia Berhad". Standard Chartered. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "Bank of China (Malaysia) Berhad". Bank of China. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Free rides as 'Hop-On Hop-Off' starts". The Star. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Arnold Loh (27 June 2015). "Uber makes presence felt in Penang". The Star. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Bicycle Rentals". Penang State Government. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Penang tourism: Promoting cycle lanes in urban heritage areas". The Sun. 24 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Penang Hill train service to resume next year". Bernama. The Malaysian Insider. 6 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ric Francis; Colin Ganley (2006). Penang Trams, Trolleybuses & Railways: Municipal Transport History, 1880s-1963. Areca Books. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-983-42834-0-7.

- ^ Tan Sin Chow (15 August 2015). "Trams making comeback under RM27bil Penang plan". The Star. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ a b David Tan (16 April 2015). "First LRT project in Penang next year". The Star. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "Penang to ease island's transport woes". The Star/Asia News Network. The Straits Times. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ Looi Sue-Chern (25 January 2016). "After Ho Chi Minh, Yangon, let's have Hong Kong, says Lim". The Malaysian Insider. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ N. Trisha (28 January 2016). "First AirAsia plane flies in from Ho Chi Minh City". The Star. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ ""Market Watch 2010" The Environmental Sector in Malaysia" (PDF). Malaysian-German Chamber of Commerce and Industry. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Hubungi Kami" (in Malay). Penang Law Courts Official Website. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Penang Syariah Court Directory". E-Syariah Malaysia. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ "Direktori PDRM (Pulau Pinang)" (in Malay). Royal Malaysia Police. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Direktori PDRM Pulau Pinang - Timur Laut" (in Malay). Royal Malaysia Police. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Clinics & Doctors in Penang — Clinics in George Town". Penang Travel Tips. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Senarai Klinik Kerajaan (List of Government Clinics)" (in Malay and English). Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pengenalan (Introduction)" (in Malay and English). Penang General Hospital. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Specialties & Services (Our Facilities & Services)". Lam Wah Ee Hospital. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About Us". Island Hospital. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About Us". Penang Adventist Hospital. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Services and Facilities Available". Loh Guan Lye Specialist Centre. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Our History". Pantai Hospitals (Gleneagles Hospitals). Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The History - How It All Began". Gleneagles Penang. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mount Miriam Cancer Hospital". Georgetown Penang Attractions. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tropicana Medical Centre". Georgetown Penang Attractions. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH DI NEGERI PULAU PINANG (List of Secondary Schools in Penang) – See Penang" (PDF). Educational Management Information System. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Our Campuses". KDU University College. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About the Campus". SEGi College Penang. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Sentral College Penang (Main Page)". Sentral College Penang. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "About Us". Olympia College. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Campuses (INTI International College Penang)". INTI International University. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "ペナン日本人補習授業校 (Penang Japanese Saturday School)" (in Japanese and English). Penang Japanese Saturday School. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Introduction" (in Malay and English). Penang Public Library Corporation. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Perpustakaan Cawangan (Libraries Branch)" (in Malay and English). Penang Public Library Corporation. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Heritage Trail Around George Town". Penang State Government. 27 July 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Penang Heritage Trail". Google Maps. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Penny Wong. "Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion in Penang". Penang.ws. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Penny Wong. "Cheah Kongsi in Penang". Penang.ws. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Penny Wong. "Clan Jetties in Penang". Penang.ws. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Penny Wong. "Old Georgetown Streets at Penang". Penang.ws. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Penny Wong. "Hainanese Mariners' Lodge in Penang". Penang.ws. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Penny Wong. "Millionaire's Row in Penang". Penang.ws. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Penang Butterfly Farm". Penang State Government. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Opalyn Mok (5 November 2012). "'Hanging' out with nature". The Malaysian Insider. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "P. Ramlee's Birthplace". National Archives of Malaysia. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Penny Wong. "Penang Road". Penang.ws. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Joe Bindloss; Celeste Brash (2008). Kuala Lumpur, Melaka & Penang. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-1-74104-485-0.

- ^ Opalyn Mok (4 September 2014). "Penang's Soonstead Mansion saved from demolition". The Malay Mail. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 7 April 2016 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Trinna Leong (15 June 2012). "No Sticker Lady Here: Malaysia Welcomes a New Banksy". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Opalyn Mok (13 December 2015). "Be warned! A visit to Wonderfood Museum will make you hungry". The Malay Mail. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pinang Peranakan Mansion". Penang State Government. 3 September 2009. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wong Chun Wai (6 July 2013). "The Jewish community in Penang is all but gone leaving only tombs behind". The Star. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Lim Yoke Mui; Nurwati Badarulzaman; A. Ghafar Ahmad (20–22 January 2003). "Retail Activity in Malaysia : From Shophouse to Hypermarket" (PDF). School of Housing, Building and Planning, University of Science, Malaysia. Pacific Rim Real Estate Society (PRRES). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Georgetown". University of Science, Malaysia. 19 February 2004. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Stadiums in Malaysia (Penang City)". World Stadiums. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Australian Consulate in Penang, Malaysia". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia). Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Directory of Consulates". Penang State Government. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lim Guan Eng (8 October 2013). "The New China's Consulate-General Office In Penang Reflects The Burgeoning Increase In Chinese Arrivals By 50% For Tourism And Business Air Travellers At The Penang International Airport". Penang Chief Minister Office. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia, Penang". Consulate General of Indonesia, Penang, Malaysia. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "Consulate-General of Japan in Penang, Malaysia". Consulate-General of Japan in Penang, Malaysia. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "Opening the first Consulate Honorary of the Republic of Poland in West Malaysia". Embassy of the Republic of Poland, Kuala Lumpur. 14 April 2014. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Royal Thai Consulate-General, Penang, Malaysia". Royal Thai Consulate-General, Penang, Malaysia. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "Supporting British nationals in Malaysia". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

Working with local partners and honorary representatives in Penang, Langkawi, Kota Kinabalu and Kuching to assist British nationals

- ^ a b c Hans Michelmann (28 January 2009). Foreign Relations in Federal Countries. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 198–. ISBN 978-0-7735-7618-6.

- ^ "Achievements of the Sister City Relationship". Adelaide City Council. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Malaysia-Xiamen trade volume gets a boost". New Straits Times. 21 November 2001. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "Kunjungan Hormat oleh Konsul Jeneral ke atas Walikota Medan" (in Malay). Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia. 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Malaysia: Taipei, Georgetown ink friendship memorandum". Central News Agency. Taiwan News. 29 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sister Cities Agreement, Georgetown". International Affairs Division, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Natthaphol Wittayarungrote (18 September 2014). "Phuket and Penang become twin cities". Phuket Gazette. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Literature

- Suet Leng Khoo; Narimah Samat; Nurwati Badarulzaman; Sharifah Rohayah Sheikh Dawood The Promise and Perils of the Island City of George Town (Penang) as a Creative City (archive link). Urban Island Studies. (2015).

- Francis, Ric; Ganley, Colin. Penang Trams, Trolleybuses & Railways: Municipal Transport History 1880s–1963. Penang: Areca Books. (2006, 2nd ed. 2012) ISBN 983-42834-0-7.

- Khoo Salma Nasution. More Than Merchants: A History of the German-speaking Community in Penang, 1800s–1940s. Areca Books. (2006). ISBN 978-983-42834-1-4

- Ooi Cheng Ghee. Portraits of Penang: Little India. Areca Books. (2011). ISBN 978-967-5719-05-9