Indian religions: Difference between revisions

SashatoBot (talk | contribs) m robot Modifying: da:Religion i Sydasien |

fmt ref |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

'''Religion in India''' comprises beliefs and traditions that rank among the world's most ancient and varied. [[India]] is one of the most religiously diverse nations in the world; religion plays a central role in the lives of most Indians. The [[Constitution of India]] declares the nation to be a [[secularism in India|secular]] republic that must uphold the right of citizens to freely worship and propagate any religion or faith.<ref>[http://lawmin.nic.in/legislative/Art1-242%20(1-88).doc The Constitution of India Art 25-28]. Retrieved on [[22 April]] [[2007]].</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://indiacode.nic.in/coiweb/amend/amend42.htm |title=The Constitution (Forty-Second Amendment) Act, 1976 |accessdate=2007-04-22 }}</ref> |

'''Religion in India''' comprises beliefs and traditions that rank among the world's most ancient and varied. [[India]] is one of the most religiously diverse nations in the world; religion plays a central role in the lives of most Indians. The [[Constitution of India]] declares the nation to be a [[secularism in India|secular]] republic that must uphold the right of citizens to freely worship and propagate any religion or faith.<ref>[http://lawmin.nic.in/legislative/Art1-242%20(1-88).doc The Constitution of India Art 25-28]. Retrieved on [[22 April]] [[2007]].</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://indiacode.nic.in/coiweb/amend/amend42.htm |title=The Constitution (Forty-Second Amendment) Act, 1976 |accessdate=2007-04-22 }}</ref> |

||

More than four-fifths of Indians practice [[Hinduism]], which is native to the [[Indian subcontinent]]. [[Islam]], practised by around one-sixth of the population, is the most important minority religion. [[Christianity]] and [[Sikhism]] are each practised by around 2% of Indians.<ref name=censusreligion/> About 1.1% practise [[Buddhism]] and 0.4% practise [[Jainism]]; both are [[Dharmic religion]]s, which originated in the [[Indian subcontinent]] and have long had a worldwide presence. [[Zoroastrianism]] and [[Judaism]] have a long history in India; each has several thousand adherents. |

More than four-fifths of Indians practice [[Hinduism]], which is native to the [[Indian subcontinent]]. [[Islam]], practised by around one-sixth of the population, is the most important minority religion. [[Christianity]] and [[Sikhism]] are each practised by around 2% of Indians.<ref name=censusreligion>{{cite web |title=Tables: Profiles by main religions |url=http://www.censusindia.net/religiondata/ |format=Data file (in spreadsheet format) |accessdate=2007-04-17 |work=Census of India 2001: Data on religion |publisher=Office of the Registrar General, India }}. Please download the file (which is compressed by winzip) to see the data in spreadsheet.</ref> About 1.1% practise [[Buddhism]] and 0.4% practise [[Jainism]]; both are [[Dharmic religion]]s, which originated in the [[Indian subcontinent]] and have long had a worldwide presence. [[Zoroastrianism]] and [[Judaism]] have a long history in India; each has several thousand adherents. |

||

Religious considerations are extremely important to the vast majority of Indians; more than nine-tenths of Indians state that religion plays a key role in their lives.<ref name="PRC_2002">{{cite web |url=http://people-press.org/reports/display.php3?ReportID=167 |title=Among Wealthy Nations ... U.S. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion |publisher=The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press |date=[[19 December]] [[2002]] |accessdate=2007-06-03 }}</ref> Though inter-religious marriages are generally taboo, Indians are generally tolerant of other religions and retain a secular outlook. Inter-community clashes have never found widespread support in the social mainstream, and it is generally perceived that its causes are political rather than ideological in nature. India's religious diversity extends to the highest levels of government; the [[President of India]] is a Muslim, the [[Prime Minister of India|Prime Minister]] is a Sikh, and the chairperson of the ruling [[United Progressive Alliance]] (UPA) is a Christian. |

Religious considerations are extremely important to the vast majority of Indians; more than nine-tenths of Indians state that religion plays a key role in their lives.<ref name="PRC_2002">{{cite web |url=http://people-press.org/reports/display.php3?ReportID=167 |title=Among Wealthy Nations ... U.S. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion |publisher=The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press |date=[[19 December]] [[2002]] |accessdate=2007-06-03 }}</ref> Though inter-religious marriages are generally taboo, Indians are generally tolerant of other religions and retain a secular outlook. Inter-community clashes have never found widespread support in the social mainstream, and it is generally perceived that its causes are political rather than ideological in nature. India's religious diversity extends to the highest levels of government; the [[President of India]] is a Muslim, the [[Prime Minister of India|Prime Minister]] is a Sikh, and the chairperson of the ruling [[United Progressive Alliance]] (UPA) is a Christian. |

||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

]] |

]] |

||

Following is the |

Following is the breakdown of different religions in India: |

||

{| style="text-align:right;" class="sortable wikitable" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" |

{| style="text-align:right;" class="sortable wikitable" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="0" |

||

|+ '''Religions of India'''{{cref|α}}{{cref|β}} |

|+ '''Religions of India'''<ref name=censusreligion/>{{cref|α}}{{cref|β}} |

||

|- style="background:#CCCCCC; color:black; text-align: center;" |

|- style="background:#CCCCCC; color:black; text-align: center;" |

||

! style="text-align:left;" | [[Religion]] !! Persons !! Percent |

! style="text-align:left;" | [[Religion]] !! Persons !! Percent |

||

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

! style="text-align:left;" | Religion not stated |

! style="text-align:left;" | Religion not stated |

||

| 727,588 || 0.07% |

| 727,588 || 0.07% |

||

|} |

|||

|}<div style="text-align: left; width: 100%;"><small>Source: Census of India, 2001<ref name=censusreligion>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.censusindia.net/religiondata/ |

|||

| title = Tables: Profiles by main religions. DATA FILE (in Spreadsheet format) |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

|||

| work = Census of India 2001: DATA ON RELIGION |

|||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

|||

}} Please download the file (which is compressed by winzip) to see the data in spreadsheet.</ref></small></div> |

|||

<!--[[Image:India religion pi graph.svg|thumb|Breakup of India's religions:{{crlf}}{{crlf}} |

<!--[[Image:India religion pi graph.svg|thumb|Breakup of India's religions:{{crlf}}{{crlf}} |

||

| Line 144: | Line 138: | ||

|format= PDF |

|format= PDF |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

||

| work = Census of India 2001: |

| work = Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

| Line 152: | Line 146: | ||

|format= PDF |

|format= PDF |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

||

| work = Census of India 2001: |

| work = Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

| Line 160: | Line 154: | ||

|format= PDF |

|format= PDF |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

||

| work = Census of India 2001: |

| work = Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

| Line 168: | Line 162: | ||

|format= PDF |

|format= PDF |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

||

| work = Census of India 2001: |

| work = Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

| Line 176: | Line 170: | ||

|format= PDF |

|format= PDF |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

||

| work = Census of India 2001: |

| work = Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

| Line 184: | Line 178: | ||

|format= PDF |

|format= PDF |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

||

| work = Census of India 2001: |

| work = Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

| Line 192: | Line 186: | ||

|format= PDF |

|format= PDF |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

||

| work = Census of India 2001: |

| work = Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

| Line 210: | Line 204: | ||

| accessdate = 2007-04-20 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-20 |

||

| format =PDF |

| format =PDF |

||

| work =Census of India 2001: Data on |

| work =Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

| pages = pp. 1–9 |

| pages = pp. 1–9 |

||

| Line 280: | Line 274: | ||

| title = Tables: Profiles by main religions. |

| title = Tables: Profiles by main religions. |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-17 |

||

| work = Census of India 2001: |

| work = Census of India 2001: Data on religion |

||

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

| publisher = Office of the Registrar General, India |

||

}}</ref></small></div> |

}}</ref></small></div> |

||

| Line 388: | Line 382: | ||

=== Politics === |

=== Politics === |

||

[[Image:Babri rearview.jpg|thumb|The [[Babri Mosque]], namesake of [[Mughal Empire|Mughal]] [[list of Mughal emperors|emperor]] [[Babur]], was razed by Hindu extremists in 1992]] |

[[Image:Babri rearview.jpg|thumb|The [[Babri Mosque]], namesake of [[Mughal Empire|Mughal]] [[list of Mughal emperors|emperor]] [[Babur]], was razed by Hindu extremists in 1992.]] |

||

Religious ideology, particularly that expressed by the [[Hindutva]] movement, has strongly influenced [[Politics of India|Indian politics]]. Many of the elements underlying India's [[casteism]] and [[communalism (South Asia)|communalism]] originated during the rule of the [[British India|British Raj]], particularly after the late 19th century; the authorities and others often politicised religion.<ref>{{harvnb|Makkar|1993|p=141}}</ref> The [[Government of India Act 1909|Indian Councils Act of 1909]] (widely known as the Morley-Minto Reforms Act), which established separate Hindus and Muslim electorates for the Imperial Legislature and provincial councils, was particularly divisive. It was blamed for increasing tensions between the two communities.<ref>{{harvnb|Olson|Shadle|1996|p=759}}</ref> Due to the high degree of oppression faced by the lower castes, the [[Constitution of India]] included provisions for [[affirmative action]] for certain sections of Indian society. Growing disenchantment with the [[Hindu caste system]] has led thousands of [[Dalits]] (also referred to as "Untouchables") to embrace Buddhism and Christianity in recent decades.<ref name=bbcdalit>{{cite news |title=Dalits in conversion ceremony |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6050408.stm |work=BBC News |date=[[14 October]] [[2006]] |accessdate=2007-04-20}}</ref> In response, many states ruled by the [[Bharatiya Janata Party]] (BJP) introduced laws that made them more difficult; they assert that such conversions are often forced or allured.<ref name=bjpdalit>{{cite journal |date=May 1–15, 2006 |title=Constitution doesn’t permit forced conversions: Naqvi |journal=BJP Today |volume=15 |issue=9 |url=http://www.bjp.org/today/may_0106/may_0106_p_30.htm |accessdate=2007-04-20}}</ref> The BJP, a [[Hindu nationalism|Hindu nationalist]] party, gained widespread media attention after its leaders associated themselves with the [[Ayodhya debate|Ram Janmabhoomi movement]] and other prominent issues.<ref>{{harvnb|Ludden|1996|pp=64–65}}</ref> |

Religious ideology, particularly that expressed by the [[Hindutva]] movement, has strongly influenced [[Politics of India|Indian politics]]. Many of the elements underlying India's [[casteism]] and [[communalism (South Asia)|communalism]] originated during the rule of the [[British India|British Raj]], particularly after the late 19th century; the authorities and others often politicised religion.<ref>{{harvnb|Makkar|1993|p=141}}</ref> The [[Government of India Act 1909|Indian Councils Act of 1909]] (widely known as the Morley-Minto Reforms Act), which established separate Hindus and Muslim electorates for the Imperial Legislature and provincial councils, was particularly divisive. It was blamed for increasing tensions between the two communities.<ref>{{harvnb|Olson|Shadle|1996|p=759}}</ref> Due to the high degree of oppression faced by the lower castes, the [[Constitution of India]] included provisions for [[affirmative action]] for certain sections of Indian society. Growing disenchantment with the [[Hindu caste system]] has led thousands of [[Dalits]] (also referred to as "Untouchables") to embrace Buddhism and Christianity in recent decades.<ref name=bbcdalit>{{cite news |title=Dalits in conversion ceremony |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6050408.stm |work=BBC News |date=[[14 October]] [[2006]] |accessdate=2007-04-20}}</ref> In response, many states ruled by the [[Bharatiya Janata Party]] (BJP) introduced laws that made them more difficult; they assert that such conversions are often forced or allured.<ref name=bjpdalit>{{cite journal |date=May 1–15, 2006 |title=Constitution doesn’t permit forced conversions: Naqvi |journal=BJP Today |volume=15 |issue=9 |url=http://www.bjp.org/today/may_0106/may_0106_p_30.htm |accessdate=2007-04-20}}</ref> The BJP, a [[Hindu nationalism|Hindu nationalist]] party, gained widespread media attention after its leaders associated themselves with the [[Ayodhya debate|Ram Janmabhoomi movement]] and other prominent issues.<ref>{{harvnb|Ludden|1996|pp=64–65}}</ref> |

||

| Line 404: | Line 398: | ||

=== Education === |

=== Education === |

||

| ⚫ | Several political parties have been accused of using their political power to manipulate educational content in a [[historical revisionism|revisionist]] manner. During the [[Janata Party]] government (1977–1979), the government was accused of being too sympathetic to the Muslim viewpoint. In 2002, the BJP-led [[National Democratic Alliance (India)|NDA]] government tried to change the [[National Council of Educational Research and Training]] (NCERT) school textbooks through a new National Curriculum Framework.<ref name="delhi1">{{cite web |author=Mukherjee M, Mukherjee A |format=PDF |title=Communalisation of education: the history textbook controversy |publisher=Delhi Historians' Group |url=http://www.sacw.net/India_History/DelHistorians.pdf |month=December |year=2001 |accessdate= 2007-06-03 }}</ref> The changes promoted [[Hindutva]] [[national mysticism]], which conformed to a narrow sectarian and Hindu chauvinist ideology; some media referred to it as the "saffronisation" of textbooks, saffron being the colour of BJP flag.<ref name="delhi1"/> The next government, formed by the UPA and led by the Congress Party, pledged to de-saffronise textbooks.<ref name=report2005>{{cite web |url=http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2005/51618.htm |title= |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | International Religious Freedom Report 2005|accessdate= 2007-06-03 |author=Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor |date=[[November 8]] 2005|work=2005 Report on International Religious Freedom |publisher= U.S. State Department}}</ref> Hindu groups alleged that the UPA promoted Marxist and pro-Muslim biases in school curricula.<ref>{{cite web |author=Upadhyay R |title=The politics of education in India: the need for a national debate |publisher=South Asia Analysis Group |url=http://www.saag.org/%5Cpapers3%5Cpaper299.html |date=[[21 August]] [[2001]] |accessdate=2007-06-03 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Upadhyay R |title=Opposition in India: in search of genuine issues |publisher= South Asia Analysis Group |url=http://www.saag.org/%5Cpapers2%5Cpaper107.html |date=[[26 February]] [[2000]] |accessdate=2007-06-03 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Several political parties have been accused of |

||

| ⚫ | International Religious Freedom Report 2005|accessdate= 2007-06-03 |author=Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor |date=[[November 8]] 2005|work=2005 Report on International Religious Freedom |publisher= U.S. State Department}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Communal conflicts have periodically plagued |

Communal conflicts have periodically plagued India since it became independent in 1947. The roots of such strife lie largely in the underlying tensions between sections of its majority Hindu and minority Muslim communities, which emerged under the Raj and during the bloody [[Partition of India]]. Such conflict also stems from the competing ideologies of [[Hindu nationalism]] versus [[Islamic fundamentalism]] and [[Islamism]]; both are prevalent in parts of the Hindu and Muslim populations. Alongside other major Indian independence leaders, [[Mahatma Gandhi]] and his ''shanti sainiks'' ("peace soldiers") worked to quell early outbreaks of religious conflict in [[Bengal]], including riots in [[Kolkata|Calcutta]] (now in [[West Bengal]]) and [[Noakhali District]] (in modern-day [[Bangladesh]]) that accompanied [[Muhammad Ali Jinnah]]'s [[Direct Action Day]], which was launched on [[16 August]] [[1946]]. These conflicts, waged largely with rocks and knives and accompanied by widespread looting and arson, were crude affairs. Explosives and firearms, which are rarely found in India, were far less likely to be used.<ref>{{harvnb|Shepard|1987|pp=45–46}}.</ref> |

||

Notable post-independence communal conflicts include the [[1984 Anti-Sikh Riots]], which followed the [[Operation Blue Star|storming of the Harimandir Sahib]] by the [[Indian Army]]; heavy artillery, tanks, and helicopters were employed against the [[Khalistan movement|Sikh separatist]]s hiding inside, causing heavy damage to Sikhism's holiest shrine. [[Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale]], who sought independence for the proposed Sikh theocracy of [[Khalistan]], was killed by Indian troops during the assault. This triggered [[Indira Gandhi]]'s assassination by her outraged Sikh bodyguards on [[31 October]] [[1984]], which set off a four-day period during which Sikhs were massacred. Other incidents include the 1992 [[Bombay Riots]] that followed the demolition of the [[Babri Mosque]] as a result of the [[Ayodhya debate]], and the [[2002 Gujarat violence]] that followed the [[Godhra Train Burning]]—in the latter, more than 2,000 Muslims were killed.<ref>{{harvnb|Human Rights Watch|2006|p=265}}.</ref> Terrorist activities such as the [[2005 Ram Janmabhoomi attack in Ayodhya]], the [[2006 Varanasi bombings]], the [[2006 Jama Masjid explosions]], and the [[11 July 2006 Mumbai Train Bombings]] are often blamed on communalism. Lesser incidents plague many towns and villages; representative was the killing of five people in [[Mau]], [[Uttar Pradesh]] during Hindu-Muslim rioting, which was triggered by the proposed celebration of a Hindu festival.<ref>{{harvnb|Human Rights Watch|2006|p=265}}.</ref> |

|||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

| Line 426: | Line 422: | ||

== References == |

== References == |

||

<div class="references-small"> |

|||

* {{Harvard reference |

* {{Harvard reference |

||

| surname1=Charlton |

| surname1=Charlton |

||

| Line 462: | Line 459: | ||

| publisher=Princeton University Press |

| publisher=Princeton University Press |

||

| isbn=0-691-06663-9 |

| isbn=0-691-06663-9 |

||

}} |

|||

* {{Harvard reference |

|||

| surname1=Human Rights Watch |

|||

| year=2006 |

|||

| title=Human Rights Watch World Report 2006 |

|||

| publisher=Seven Stories Press |

|||

| isbn=1-583-22715-6 |

|||

| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=eXmogaDhd20C |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{Harvard reference |

* {{Harvard reference |

||

| Line 516: | Line 521: | ||

| publisher=ABC-Clio |

| publisher=ABC-Clio |

||

| isbn=1-57607-905-8 |

| isbn=1-57607-905-8 |

||

}} |

|||

* {{Harvard reference |

|||

| surname1=Shepard |

|||

| given1=MA |

|||

| title=Gandhi Today: A Report on Mahatma Gandhi's Successors |

|||

| year=1987 |

|||

| publisher=Shepard Publications |

|||

| isbn=0-93849-704-9 |

|||

| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=DQyPbvLvK_sC |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{Harvard reference |

* {{Harvard reference |

||

| Line 522: | Line 536: | ||

| title=The Making of Pakistan |

| title=The Making of Pakistan |

||

| year=1950 |

| year=1950 |

||

| title=Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice |

|||

| publisher=[[Faber and Faber]] |

| publisher=[[Faber and Faber]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

</div> |

|||

== Citations == |

== Citations == |

||

| Line 533: | Line 547: | ||

;Statistics |

;Statistics |

||

* {{cite web |title=Census of India 2001: Data on |

* {{cite web |title=Census of India 2001: Data on religion |work=Government of India (Office of the Registrar General) |url=http://www.censusindia.net/religiondata/ |accessdate=2007-05-28 }} |

||

;Constitution and law |

;Constitution and law |

||

| Line 552: | Line 566: | ||

<!-- Interwiki --> |

<!-- Interwiki --> |

||

[[da:Religion i Sydasien]] |

[[da:Religion i Sydasien]] |

||

Revision as of 13:02, 9 June 2007

Religion in India comprises beliefs and traditions that rank among the world's most ancient and varied. India is one of the most religiously diverse nations in the world; religion plays a central role in the lives of most Indians. The Constitution of India declares the nation to be a secular republic that must uphold the right of citizens to freely worship and propagate any religion or faith.[1][2]

More than four-fifths of Indians practice Hinduism, which is native to the Indian subcontinent. Islam, practised by around one-sixth of the population, is the most important minority religion. Christianity and Sikhism are each practised by around 2% of Indians.[3] About 1.1% practise Buddhism and 0.4% practise Jainism; both are Dharmic religions, which originated in the Indian subcontinent and have long had a worldwide presence. Zoroastrianism and Judaism have a long history in India; each has several thousand adherents.

Religious considerations are extremely important to the vast majority of Indians; more than nine-tenths of Indians state that religion plays a key role in their lives.[4] Though inter-religious marriages are generally taboo, Indians are generally tolerant of other religions and retain a secular outlook. Inter-community clashes have never found widespread support in the social mainstream, and it is generally perceived that its causes are political rather than ideological in nature. India's religious diversity extends to the highest levels of government; the President of India is a Muslim, the Prime Minister is a Sikh, and the chairperson of the ruling United Progressive Alliance (UPA) is a Christian.

History

Evidence of prehistoric religion in India is sparse. The Harappan people of the Indus Valley Civilisation, which lasted from 3300–1700 BCE and was centered around the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra river valleys, may have worshipped an important mother goddess symbolising fertility.[5] Excavations of Indus Valley Civilisation sites show seals with animals and "fire‑altars", indicating rituals associated with fire. A linga-yoni of the same type as is worshipped now by Hindus has also been found.

Hinduism's origins include cultural elements of the Indus valley civilisation, the Vedic religion of the Indo-Aryans, and other Indian civilisations. The oldest surviving text of Hinduism is the Rigveda, produced during the Vedic period and dated to 1700–1100 BCE.[γ][6] During the Epic and Puranic periods, the earliest versions of the epic poems Ramayana and Mahabharata were written roughly from 500–100 BCE,[7] although these were orally transmitted for centuries prior to this period.[8]

After 200 CE, several schools of thought were formally codified in Indian philosophy, including Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Purva-Mimamsa and Vedanta.[9] Hinduism, otherwise a highly theistic religion, hosted atheistic schools; the thoroughly materialistic and anti-religious philosophical Carvaka school that originated in India around the 6th century BCE is probably the most explicitly atheistic school of Indian philosophy. Carvaka is classified as a nastika ("heterodox") system; it is not included among the six schools of Hinduism generally regarded as orthodox. It is noteworthy as evidence of a materialistic movement within Hinduism.[10] Our understanding of Carvaka philosophy is fragmentary, based largely on criticism of the ideas by other schools, and it is no longer a living tradition.[11] Other Indian philosophies generally regarded as atheistic include Classical Samkhya and Purva Mimamsa.

According to the Buddhist tradition, the historical Gautama Buddha was born to the Shakya clan, at the beginning of the Magadha period (546–324 BCE), in the plains of Lumbini, in what is now southern Nepal. The Sakyas claimed to be avatars of Vishnu. Mahavira (599–527 BC, though possibly 549–477 BC) established the central tenets of Jainism. Buddhism and Jainism adapted elements of Hinduism into their beliefs. Buddhism (or at least Buddhistic Hinduism) peaked during the reign of Asoka the Great of the Mauryan Empire, who unified the Indian subcontinent in the 3rd century BCE. He also sent missionaries to spread Buddha's teachings to places outside of South Asia, such as Afghanistan, Central Asia, the Middle East and even Egypt.[12] Buddhism declined in India following the loss of patronage due to the fall of sympathetic rulers such as the kings of Magadha, Kosala and the Kushan.

Between 400 BCE and 1000 CE, Hinduism expanded at the expense of Buddhism.[13] Buddhism subsequently became effectively extinct in India. Though Islam came to India in the early 7th century with the advent of Arab traders, it started to become a major religion during the Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent. Islam spread in India mainly during the reigns of the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526) and the Mughal Empire, greatly aided by the simple practices of Sufism (a mystic tradition of Islam). Although historical evidence suggests the presence of Christianity in India since the first century, it became popular following European colonisation and missionary efforts.

Communalism has played a key role in shaping the religious history of modern India. British India was partitioned along religious lines into two states—the Muslim-majority Dominion of Pakistan (comprising what is now the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People's Republic of Bangladesh) and the Hindu-majority Union of India (later the Republic of India). The 1947 Partition of India inaugurated rioting among Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs in Punjab, Bengal, Delhi, and other parts of India; 500,000 died as a result of the violence. The twelve million refugees that moved between the newly founded nations of India and Pakistan composed one of the largest mass migrations in modern history.[Δ][14] Since its independence, India has periodically witnessed large-scale violence sparked by underlying tensions between sections of its majority Hindu and minority Muslim communities. The Republic of India is secular; though it is often considered a Hindu holy land (punyabhumi), its government recognises no official religion. In recent decades, communal tensions and religion-based politics have become more prominent.[15]

Demographics

Hinduism is the largest religion in India; its 828 million adherents compose 80.4% of the population. The word Hindu, originally a geographical description, derives from the Sanskrit, Sindhu, (the historical appellation for the river Indus), and refers to a person from the land of the river Sindhu. Islam is a monotheistic religion centred around the belief in one God and following the example of the Prophet Muhammad. It is the largest minority religion in India. As of 2007, India was home to 147 million Muslims, the world's third-largest Muslim population after Indonesia and Pakistan; they compose 13.4% of the population.[16] Muslims represent the majority in Jammu and Kashmir and Lakshadweep,[17] and high concentrations in the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, and Kerala.[17][3] The largest denomination is Sunni Islam, which is practised by nearly 80% of Indian Muslims.[18]

Christianity is a monotheistic religion centred on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in the New Testament.[19] Christianity is the third largest religion of India, making up 2.3% of the population. Christianity is prevalent in North-East India, Goa and Kerala. Buddhism is a dharmic, nontheistic religion and philosophy. Buddhists form majority populations in the Indian states of Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, and the Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir. In all, around 12 million Buddhists live in India today. Jainism is a nontheistic, dharmic religion and philosophy originating in Iron Age India.

Jains comprises 0.4% (around 4.2 million) of India's population, and are mostly present in the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Karnataka.[17] Sikhism began in sixteenth century Northern India with the teachings of Nanak and nine successive human gurus. As of 2001, there were 19.2 million Sikhs in India. Punjab is the spiritual home of Sikhs, and is the only state in India where Sikhs form a majority. There are also significant populations of Sikhs in the neighbouring states of Haryana and New Delhi.

As of the census of 2001, Parsis (followers of Zoroastrianism in India) represent approximately 0.006% of the total population of India,[20] with a concentration in and around the city of Mumbai. There are several tribal religions in India (which may just be different traditions within Hinduism), such as Donyi-Polo and Mahima. About 2.2 million people in India follow the Bahá'í Faith, thus forming the largest community of Bahá'ís in the world.[21] The Bahá'ís originated from the Babi sect when the prophecy of the coming prophet (Bahá'í) was satisfied. Ayyavazhi, prevalent in Southern India, is officially considered a sect within Hinduism, and its followers are counted as Hindus in the census. A very minor community of Jews is present in Kerala and Maharashtra. Up to 2% of Indians are estimated to be atheists;[20] Around 0.07% of the people did not state their religion in the 2001 census.

Statistics

Following is the breakdown of different religions in India:

| Religion | Persons | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| All Religions | 1,028,610,328 | 100.00% |

| Hindus | 827,578,868 | 80.456% |

| Muslims | 138,188,240 | 13.434% |

| Christians | 24,080,016 | 2.341% |

| Sikhs | 19,215,730 | 1.868% |

| Buddhists | 7,955,207 | 0.773% |

| Jains | 4,225,053 | 0.41% |

| Others | 6,639,626 | 0.645% |

| Religion not stated | 727,588 | 0.07% |

| Composition | Hindus[22] | Muslims[23] | Christians[24] | Sikhs[25] | Buddhist[26] | Jains[27] | Others[28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % total of population 2001 | 80.46 | 13.43 | 2.34 | 1.87 | 0.77 | 0.41 | 0.65 |

| 10-Yr Growth % (est '91–'01)[29][β] | 20.3 | 36.0 | 22.6 | 18.2 | 24.5 | 26 | 103.1 |

| Sex ratio* (avg. 933) | 931 | 936 | 1009 | 893 | 953 | 940 | 992 |

| Literacy rate (avg. 64.8) | 65.1 | 59.1 | 80.3 | 69.4 | 72.7 | 94.1 | 47.0 |

| Work Participation Rate | 40.4 | 31.3 | 39.7 | 37.7 | 40.6 | 32.9 | 48.4 |

| Rural sex ratio[29] | 944 | 953 | 1001 | 895 | 958 | 937 | 995 |

| Urban sex ratio[29] | 894 | 907 | 1026 | 886 | 944 | 941 | 966 |

| Child sex ratio (0–6 yrs) | 925 | 950 | 964 | 786 | 942 | 870 | 976 |

Source: The First Report on Religion: Census of India 2001[30]

Law

The preamble to the Constitution of India proclaimed India a "sovereign socialist secular democratic republic". The word secular was inserted into the Preamble by the Forty-second Amendment Act of 1976. It mandates equal treatment and tolerance of all religions. India does not have an official state religion; it enshrines the right to practice, preach, and propagate any religion. No religious instruction is imparted in government-supported schools. In S. R. Bommai vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court of India held that secularism was an integral tenet of the Constitution.[31]

The right to freedom of religion is a fundamental right according to the Indian Constitution. The Constitution also recommends establishment of a uniform civil code for its citizens as a Directive Principle.[32] However this has not been implemented until now. The Supreme Court has stated that the enactment of a uniform civil code all at once may be counterproductive to the unity of the nation, and only a gradual progressive change should be brought about (Pannalal Bansilal v State of Andhra Pradesh, 1996).[33] In Maharishi Avadesh v Union of India (1994) the Supreme Court dismissed a petition seeking a writ of mandamus against the government to introduce a common civil code, and thus laid the responsibility of its introduction on the legislature.[34]

Religious communities continue to be governed by their own personal laws. Apart from Muslims, designated religious codes apply to Hindus, Christians, Zoroastrians, and Jews; for legal purposes, Buddhists and Sikhs are classified as Hindus and are subject to Hindu personal law.[35] Civil laws for Muslims are based on Sharia law. The Code of Criminal Procedure is uniformly applied to all Indian citizens.

Aspects

Religion plays a major role in the Indian way of life.[4] Rituals, worship, and other religious activities are very prominent in an individual's daily life; it is also a principal organiser of social life. The degree of religiosity varies among individuals; in recent decades, religious orthodoxy and observances have become less common in Indian society, particularly among young urban-dwellers.

Rituals

The vast majority of Indians engage in religious rituals on a daily basis.[36] Most Hindus observe religious rituals at home.[37] However, observation of rituals greatly vary among regions, villages, and individuals. Devout Hindus perform daily chores such as worshiping at the dawn after bathing (usually at a family shrine, and typically includes lighting a lamp and offering foodstuffs before the images of deities), recitation from religious scripts, singing hymns in praise of gods etc.[37] A notable feature in religious ritual is the division between purity and pollution. Religious acts presuppose some degree of impurity or defilement for the practitioner, which must be overcome or neutralised before or during ritual procedures. Purification, usually with water, is thus a typical feature of most religious action.[37] Other characteristics include a belief in the efficacy of sacrifice and concept of merit, gained through the performance of charity or good works, that will accumulate over time and reduce sufferings in the next world.[37] Devout Muslims offer five daily prayers at specific times of the day, indicated by adhan (call to prayer) from the local mosques. Before offering prayers, they must ritually clean themselves by performing wudu, which involves washing parts of the body that are generally exposed to dirt or dust. A recent study by the Sachar Committee found that 3-4% of Muslim children study in madrasas (Islamic schools).[38]

Dietary habits are significantly influenced by religion. Almost one-third of Indians practise vegetarianism; it came to prominence during the rule of Ashoka, a promoter of Buddhism.[39][40] Vegetarianism is much less common among Muslim and Christians.[41] Jainism requires monks and laity, from all its sects and traditions, to be vegetarian. Hinduism bars beef consumption, while Islam bars pork.

Ceremonies

Occasions like birth, marriage, and death involve what are often elaborate sets of religious customs. In Hinduism, life-cycle rituals include Annaprashan (a baby's first intake of solid food), Upanayanam ("sacred thread ceremony" undergone by upper-caste youths), Shraadh (ritual of treating people to feasts in the name of the deceased).[42][43] For most people in India, the betrothal of the young couple and the exact date and time of the wedding are matters decided by the parents in consultation with astrologers.[42]

Muslims practice a series of life-cycle rituals that differ from those of Hindus, Jains, and Buddhists.[44] Several rituals mark the first days of life—including whispering call to prayer, first bath, and shaving of the head. Religious instruction begins early. Male circumcision usually takes place after birth; in some families, it may be delayed until after the onset of puberty.[44] Marriage requires a payment by the husband to the wife and the solemnisation of a marital contract in a social gathering.[44] On the third day after burial of the dead, friends and relatives gather to console the bereaved, read and recite the Quran, and pray for the soul of the deceased.[44] Indian Islam is distinguished by the emphasis it places on shrines commemorating great Sufi saints.[44]

Pilgrimages

India hosts numerous pilgrimage sites belonging to many religions. Hindus worldwide recognise several Indian holy cities, including Allahabad, Haridwar, Varanasi, and Vrindavan. Notable temple cities include Puri, which hosts a major Vaishnava Jagannath temple and Rath Yatra celebration; Tirumala - Tirupati, home to the Tirumala Venkateswara Temple; and Katra, home to the Vaishno Devi temple. The Himalayan towns of Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, and Yamunotri compose the Char Dham (four abodes) pilgrimage circuit. The Kumbh Mela (the "pitcher festival") is one of the holiest of Hindu pilgrimages that is held every four years; the location is rotated among Allahabad, Haridwar, Nashik, and Ujjain.

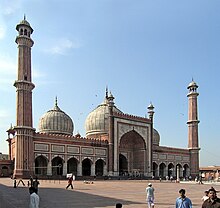

Among the Eight Great Places of Buddhism, seven are in India. Bodh Gaya, Sarnath and Kushinagar are the places where important events in the life of Gautama Buddha took place. Sanchi hosts a Buddhist stupa erected by the emperor Ashoka. Several Tibetan Buddhist sites in the Himalayan foothills of India have been built, such as Rumtek Monastery and Dharamsala. For Muslims, the Dargah Shareef of Khwaza Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer is a major pilgrimage site. Other Islamic pilgrimages include those to the Tomb of Sheikh Salim Chishti in Fatehpur Sikri, Jama Masjid in Delhi, and to Haji Ali Dargah in Mumbai. Dilwara Temples in Mount Abu, Palitana, Pavapuri, Girnar and Shravanabelagola are notable pilgrimage sites (tirtha) in Jainism.

The Golden Temple in Amritsar is the most sacred shrine of Sikhism, while the Thalaimaippathi at Swamithope is the leading pilgrim center for Ayyavazhi's. Lotus Temple in Delhi is a prominent house of worship of the Bahá'í faith.

Festivals

Religious festivals are widely observed and hold great importance for Indians. In keeping with India's secular governance, no religious festival has been accorded the status of a national holiday. Diwali, Ganesh Chaturthi, Holi, Durga puja, Ugadi, Dussehra, and Sankranthi/Pongal are the most popular Hindu festivals in India. Among Muslims, the Islamic Eid festivals of Eid-ul-Fitr and Eid-ul-Adha, Muharram, and Ramadan are the most celebrated. Christmas, Buddha Jayanti, and Guru Nanak's Birthday are key holidays among the remaining religious groups. A number of festivals are common to most parts of India, and many states and regions have local festivals depending on prevalent religious and linguistic demographics. For example, fairs and festivities associated with specific temples or Dargahs associated with Sufi masters are common.

Muharram is a unique festival in the sense that it is not celebrated; it is a mournful commemoration of the death of Muhammad's grandson Imam Husain in 680 CE. A taziya, which is a bamboo replica of Husain's tomb, is paraded through the city. Muharram is observed with great passion in Lucknow, the centre of Indian Shia Islam.[45]

Sectarianism

Politics

Religious ideology, particularly that expressed by the Hindutva movement, has strongly influenced Indian politics. Many of the elements underlying India's casteism and communalism originated during the rule of the British Raj, particularly after the late 19th century; the authorities and others often politicised religion.[46] The Indian Councils Act of 1909 (widely known as the Morley-Minto Reforms Act), which established separate Hindus and Muslim electorates for the Imperial Legislature and provincial councils, was particularly divisive. It was blamed for increasing tensions between the two communities.[47] Due to the high degree of oppression faced by the lower castes, the Constitution of India included provisions for affirmative action for certain sections of Indian society. Growing disenchantment with the Hindu caste system has led thousands of Dalits (also referred to as "Untouchables") to embrace Buddhism and Christianity in recent decades.[48] In response, many states ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) introduced laws that made them more difficult; they assert that such conversions are often forced or allured.[49] The BJP, a Hindu nationalist party, gained widespread media attention after its leaders associated themselves with the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and other prominent issues.[50]

A well known accusation that Indian political parties make for their rivals is that they play vote bank politics, meaning give political support to issues for the sole purpose of gaining the votes of members of a particular community. Both the Congress Party and the BJP have been accused of exploiting the people by indulging in vote bank politics. The Shah Bano case, a divorce lawsuit, generated much controversy when the Congress was accused of appeasing the Muslim orthodoxy by bringing in a parliamentary amendment to negate the Supreme Court's decision. There have been allegations that sensing an consolidation of Hindu votes against the Congress, its Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, ordered the opening of locks in the Ram Temple at Ayodhya to appease the Hindus.[51][52] After the 2002 Gujarat violence, there were allegations of political parties indulging in vote bank politics.[53] During an election campaign in Uttar Pradesh, the BJP released an inflammatory CD targeting Muslims.[54] This was condemned by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) as playing the worst kind of vote bank politics.[55] Caste-based politics is also important in India; caste-based discrimination and the reservation system continue to be major issues that are hotly debated.[56][57]

Education

Several political parties have been accused of using their political power to manipulate educational content in a revisionist manner. During the Janata Party government (1977–1979), the government was accused of being too sympathetic to the Muslim viewpoint. In 2002, the BJP-led NDA government tried to change the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) school textbooks through a new National Curriculum Framework.[58] The changes promoted Hindutva national mysticism, which conformed to a narrow sectarian and Hindu chauvinist ideology; some media referred to it as the "saffronisation" of textbooks, saffron being the colour of BJP flag.[58] The next government, formed by the UPA and led by the Congress Party, pledged to de-saffronise textbooks.[59] Hindu groups alleged that the UPA promoted Marxist and pro-Muslim biases in school curricula.[60][61]

Conflicts

Communal conflicts have periodically plagued India since it became independent in 1947. The roots of such strife lie largely in the underlying tensions between sections of its majority Hindu and minority Muslim communities, which emerged under the Raj and during the bloody Partition of India. Such conflict also stems from the competing ideologies of Hindu nationalism versus Islamic fundamentalism and Islamism; both are prevalent in parts of the Hindu and Muslim populations. Alongside other major Indian independence leaders, Mahatma Gandhi and his shanti sainiks ("peace soldiers") worked to quell early outbreaks of religious conflict in Bengal, including riots in Calcutta (now in West Bengal) and Noakhali District (in modern-day Bangladesh) that accompanied Muhammad Ali Jinnah's Direct Action Day, which was launched on 16 August 1946. These conflicts, waged largely with rocks and knives and accompanied by widespread looting and arson, were crude affairs. Explosives and firearms, which are rarely found in India, were far less likely to be used.[62]

Notable post-independence communal conflicts include the 1984 Anti-Sikh Riots, which followed the storming of the Harimandir Sahib by the Indian Army; heavy artillery, tanks, and helicopters were employed against the Sikh separatists hiding inside, causing heavy damage to Sikhism's holiest shrine. Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, who sought independence for the proposed Sikh theocracy of Khalistan, was killed by Indian troops during the assault. This triggered Indira Gandhi's assassination by her outraged Sikh bodyguards on 31 October 1984, which set off a four-day period during which Sikhs were massacred. Other incidents include the 1992 Bombay Riots that followed the demolition of the Babri Mosque as a result of the Ayodhya debate, and the 2002 Gujarat violence that followed the Godhra Train Burning—in the latter, more than 2,000 Muslims were killed.[63] Terrorist activities such as the 2005 Ram Janmabhoomi attack in Ayodhya, the 2006 Varanasi bombings, the 2006 Jama Masjid explosions, and the 11 July 2006 Mumbai Train Bombings are often blamed on communalism. Lesser incidents plague many towns and villages; representative was the killing of five people in Mau, Uttar Pradesh during Hindu-Muslim rioting, which was triggered by the proposed celebration of a Hindu festival.[64]

Notes

- ^ α: The data exclude the Mao-Maram, Paomata, and Purul subdivisions of Manipur's Senapati district.

- ^ β: The data are "unadjusted" (without excluding Assam and Jammu and Kashmir); the 1981 census was not conducted in Assam and the 1991 census was not conducted in Jammu and Kashmir.

- ^ γ: Oberlies (1998, p. 155) gives an estimate of 1100 BCE for the youngest hymns in book ten. Estimates for a terminus post quem of the earliest hymns are far more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158), based on "cumulative evidence", sets a wide range of 1700–1100 BCE. The EIEC (s.v. Indo-Iranian languages, p. 306) gives a range of 1500–1000 BCE. It is certain that the hymns post-date Indo-Iranian separation of ca. 2000 BCE. It cannot be ruled out that archaic elements of the Rigveda go back to only a few generations after this time, but philological estimates tend to date the bulk of the text to the latter half of the second millennium.

- ^ Δ: According to the most conservative estimates given by Symonds (1950, p. 74), half a million people perished and twelve million became homeless.

References

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

Citations

- ^ The Constitution of India Art 25-28. Retrieved on 22 April 2007.

- ^ "The Constitution (Forty-Second Amendment) Act, 1976". Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ a b c "Tables: Profiles by main religions" (Data file (in spreadsheet format)). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.. Please download the file (which is compressed by winzip) to see the data in spreadsheet.

- ^ a b "Among Wealthy Nations ... U.S. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion". The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 19 December 2002. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Fowler 1997, p. 90.

- ^ Oberlies 1998, p. 155.

- ^ Goldman 2007, p. 23.

- ^ Rinehart 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Radhakrishnan & Moore 1967, p. xviii–xxi.

- ^ Radhakrishnan & Moore 1967, p. 227–249.

- ^ Chatterjee & Datta 1984, p. 55.

- ^ "Buddhism and Ashoka" (php). History of Buddhism, ygoy.com. YGoY Inc. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ^ "The rise of Jainism and Buddhism". Religion and Ethics—Hinduism: Other religious influences. BBC. 26 July 2004. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Symonds 1950, p. 74.

- ^ Ludden 1996, p. 253.

- ^ "CIA Factbook: India". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ a b c "Religion in India". Religion, webindia123.com. Suni Systems (P) Ltd. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2003. By the United States Department of State. Retrieved on April 19 2007.

- ^ BBC, BBC - Religion & Ethics - Christianity

- ^ a b "Parsi population in India declines". payvand.com. NetNative. September 7 2004.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Cite error: The named reference "payvand" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "The Bahá'ís of India". bahaindia.org. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of India. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^ "Tables: Profiles by main religions: Hindus" (PDF). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ "Tables: Profiles by main religions: Muslims" (PDF). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ "Tables: Profiles by main religions: Christians" (PDF). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ "Tables: Profiles by main religions: Sikhs" (PDF). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ "Tables: Profiles by main religions: Buddhists" (PDF). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ "Tables: Profiles by main religions: Jains" (PDF). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ "Tables: Profiles by main religions: Other religions" (PDF). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ a b c "A snapshot of population size, distribution, growth and socio economic characteristics of religious communities from Census 2001" (PDF). Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. pp. pp. 1–9. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Tables: Profiles by main religions". Census of India 2001: Data on religion. Office of the Registrar General, India. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ Swami Praveen (1 November 1997). "Protecting secularism and federal fair play". Frontline. 14 (22). Retrieved 2007-04-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Constitution of India-Part IV Article 44 Directive Principles of State Policy

- ^ Iyer VRK (6 September 2003). "Unifying personal laws". Opinion. The Hindu. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lavakare, Arvind (21 May 2002). "Where's the Uniform Civil Code?". rediff.com. Rediff.com India Limited. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "India, Republic of". Legal Profiles, Islamic Family Law. Emory Law School. 2002. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ "Religious Life". Religions of India. Global Peace Works. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ a b c d "Domestic Worship". Country Studies. The Library of Congress. September 1995. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ Chishti S, Jacob J (1 December 2006). "Sachar nails madrasa myth: Only 4% of Muslim kids go there". The Indian Express. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Thakrar, Raju (22 April 2007). "Japanese warm to real curries and more". Japan Times. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Charlton 2004, p. 91.

- ^ Yadav, Yogendra (August 14 2006). "The food habits of a nation". hinduonnet.com. The Hindu. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Life-Cycle Rituals". Country Studies: India. The Library of Congress. September 1995. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ Banerjee, Suresh Chandra. "Shraddha". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ a b c d e "Islamic Traditions in South Asia". Country Studies: India. The Library of Congress. September 1995. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ "Muharram". Festivals. High Commission of India, London. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ Makkar 1993, p. 141

- ^ Olson & Shadle 1996, p. 759

- ^ "Dalits in conversion ceremony". BBC News. 14 October 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Constitution doesn't permit forced conversions: Naqvi". BJP Today. 15 (9). May 1–15, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ Ludden 1996, pp. 64–65

- ^ Misra, Satish (14 March 2004). "Congress has lost its secular credentials: Arif Khan". tribuneindia.com. The Tribune Trust. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Upadhyay, R (15 March 2004). "The grammar of vote bank politics—The Muslim community has suffered". Papers. South Asia Analysis Group. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Times News Network (25 March 2002). "Togadia wants parties to stop 'vote bank politics'". indiatimes.com. Times Internet Limited. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "BJP protests in campaign CD row". BBC News. 9 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "BJP's true colours exposed once again". People's Democracy. Communist Party of India (Marxist). 15 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chadha M (5 December 2006). "Despair of the discriminated Dalits". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Giridharadas A (22 April 2006). "Turning point in India's caste war". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Mukherjee M, Mukherjee A (2001). "Communalisation of education: the history textbook controversy" (PDF). Delhi Historians' Group. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (November 8 2005). "International Religious Freedom Report 2005". 2005 Report on International Religious Freedom. U.S. State Department. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Upadhyay R (21 August 2001). "The politics of education in India: the need for a national debate". South Asia Analysis Group. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Upadhyay R (26 February 2000). "Opposition in India: in search of genuine issues". South Asia Analysis Group. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Shepard 1987, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Human Rights Watch 2006, p. 265.

- ^ Human Rights Watch 2006, p. 265.

External links

- Statistics

- "Census of India 2001: Data on religion". Government of India (Office of the Registrar General). Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- Constitution and law

- "Constitution of India". Government of India (Ministry of Law and Justice). Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- Reports

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2006: India". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2007-05-28.