Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

May 8

Skin color in Hindu art

I've looked on Wikipedia but haven't found an answer to my question. In various types of Hindu and/ or Indian visual arts, various divine figures and some non-divine figures (as far as I can tell, not having much knowledge of Hinduism), are often depicted with skin tones of bluish tint, or other colors which appear to be non-naturally occuring. Is there any scientific explanation for why such skin tones are used? What is the symbolic/religious meaning? Thank you. --71.111.205.22 (talk) 01:04, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Well from a scientific point of view there's not much i can say about this. But from a religious point of view, many hindu gods, as you, said, are depicted blue. Vishnu and many of his avatars are portrayed blue, which is what you might have been. This might have something to do with the fact that the sea, highly regarded as a symbol of power by the hindus, is blue. But that's not saying much... some questions really don't have a comprehensive answer...Rkr1991 (talk) 08:24, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Krishna is often portrayed in blue. Hinduism uses a lot of symbolism to depict its deities and blue, amongst other things, denotes transcendentalism. Remember, the blue depiction of god is in our material universe and on our planet, the sky is blue. The gods are in the spiritual abode and the entire material universe is a cloud in the sky of the spiritual abode. So, do you get the symbolism now? Sandman30s (talk) 08:41, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- That helps a lot. Thanks for all your assistance! --71.111.205.22 (talk) 15:14, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Among the Hindu Trimurti (see File:Brahma Vishnu Mahesh.jpg):

- Vishnu and his avatars Rama, Krishna etc. are typically depicted blue-skinned (often with yellow dhoti); in fact the word Krishna literally means "black; dark; or dark blue"

- Shiva is depicted white-skinned (with a blue tongue)

- Brahma is depicted either red-skinned and/or wearing a red dhoti.

Other deities have different associated colors and symbols; see this very incomplete table for some more information. It is possible to interpret all these associations symbolically but one should be aware that the symbolic meaning is likely to vary with time, place and philosophical leanings of different sects. Abecedare (talk) 18:27, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Shiva's blue throat is a result of the poison he holds there. Jay (talk) 11:38, 11 May 2009 (UTC)

- FWIW Osiris, the ancient Egyptian god of the underworld, was commonly depicted as a green (the color of rebirth) or black (alluding to the fertility of the Nile floodplain) complexioned pharaoh in mummiform. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 07:24, 13 May 2009 (UTC)

Gravitational potential of an 'eccentric' object

I'm trying to find the gravitational potential of the 3-dimensional object described by a sphere of constant density and radius 1 centered at the origin (0,0,0) - 'A', but hollow in the sphere of radius 1/2 centred at (1/2,0,0) - 'B' - and hollow in the sphere of radius 1/4 centred at (-1/4,0,0) - 'C' - for some point x outside of A- effectively a full sphere of density plus 2 spheres of density as described previously. Can we just effectively 'add' the potentials for the respective spheres so that, if M is the mass of the large sphere 'A', we have , where b and c are the respective sphere centers? Is this at all valid?

If so, is there any point in C where a particle could theoretically remain at rest? I think not due to the asymmetry along the x-axis but I'm not sure how to show it...

Thanks very much! Mathmos6 (talk) 04:27, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- You can just add the potentials since Newtonian gravity is linear, but

the answer you wrote down isn't correct becauseGM/r is the potential of a point particle, not a sphere of constant density. (Also it has the wrong sign.) Your potential is fine (aside from the sign error) if you're only interested in the |x| > 1 region. There is an equilibrium point somewherein Cbecause every potential function, no matter how misshapen, has to have a minimum somewhere. The minimum in this case is a ring around the x axis. There's also a saddle point (unstable equilibrium) on the x axis. -- BenRG (talk) 11:42, 8 May 2009 (UTC)- Sorry, I just noticed I didn't read your question very carefully. I think the saddle point is in C (the hole of radius 1/4). It shouldn't be hard to prove that, but you'll need to write down an inside-C, inside-A, outside-B potential. -- BenRG (talk) 12:23, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Oh, also, the potential is a scalar, so you want , not . Funny I didn't notice that before. -- BenRG (talk) 12:31, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Fair enough, I was only interested in the region outside the largest sphere yes, although I can't say I'd know how to calculate the potential inside the big mess in A - also, I see your point about the scalar, but don't we need to take the fact that the potential isn't radially symmetrical into account somewhere though? Or do the 'x-b'/'x-c's do that anyway? Thanks a lot! Mathmos6 (talk) 03:51, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- The |x-b| and |x-c| takes care of that. There are four regions (inside B, inside C, inside A but outside B and C, and outside A) and you'll have a different formula for each one. Or you could write down a single formula with max/min or some such, but you'd end up having to split into four cases to prove anything interesting anyway. If you can write down the potential inside and outside a single spherical object then you can write down the potential in all four regions, since it's just a sum of the inside/outside potentials of A, B, and C (with the B and C potentials negated). -- BenRG (talk) 22:42, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

How to ensure 100% RDA with supplements?

Dietary supplements usually contain 100% RDA of some micronutrients, but some ridiculously high or low value of many others, if they contain them at all. Given that it is prohibitively complicated to find out how much of each micronutrient we actually get in our food each day, and given that it probably won't hurt to get a little bit more than 100%, wouldn't it be nice if there were a supplement on the market that had simply 100% of every micronutrient, just to be safe? Why is there no such "100% supplement" available? Or is there? Mary Moor (talk) 06:02, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- You don't say where you are, but in the UK there are such supplements available: Centrum makes one [1] --TammyMoet (talk) 08:37, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yep, I've got a bottle of '100% everything' in my own cupboard. I got mine from Boots, I think - though I've seen similar in most pharmacies and health food shops that I've been into... --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 10:31, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Thank you; maybe I have to look some more. I'm in the US, in the state of Washington. Mary Moor (talk) 15:46, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- A word of advice. Don't pay extra for products that claim to contain 500% (or more) of your RDA. You don't need *that* many micronutrients and vitamins. I don't think that your body can even do anything useful with the excess.--Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 00:21, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Not only do you not need that level, high levels of some micronutrients can make you quite ill. Franamax (talk) 09:11, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- A word of advice. Don't pay extra for products that claim to contain 500% (or more) of your RDA. You don't need *that* many micronutrients and vitamins. I don't think that your body can even do anything useful with the excess.--Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 00:21, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Unless you've got a very unhealthy diet, vitamin pills will not do you any good. Overdoses of vitamins in fact do you harm - more is not better. I used vitamin pills for many years until I started reading scientific research about them, which showed that overdoses reduced longevity, increased cancer rates, kidney damage, etc. Now I never use them (with the exception of Vitamin D in the winter as I am in northern latitudes). Better to put your time and money into eating a healthy varied diet - plenty of vegetables and fruit etc. Its very likely that there are many as yet undiscovered micro-nutrients that have long term effects, and these are only found in healthy foods, not pills. If you want to get particular vitamins or minerals then its best to find out which foods are rich in them and eat those. For example B12 - sardines. Selenium - brazil nuts. And many others. Sardines are also rich in calcium and Omega3, which illustrates how natural foods give you extra nutrients for free. 78.146.190.197 (talk) 13:00, 16 May 2009 (UTC)

neutrons, protons and electrons

During my one year of chemistry class at school, I had other things on my mind. But now I try to learn on my own...

My very elementary question is: are all neutrons, protons and electrons the same?? That is, can you see for instance, this is a typical oxygen electron and that is a typical sodium electron? Or is there no such difference? Lova Falk (talk) 06:17, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, as far as we know, all protons are identical to each other. None of them have nicks, bumps, or customized parts hanging off of them. Same with neutrons, electrons, etc. An electron is an electron - there's no difference between oxygen electrons and sodium electrons. We have an article (of course), Identical particles, but that's rather advanced. Clarityfiend (talk) 06:59, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Thank you! This is actually a bit shocking. In the articles on neutrons, protons and electrons, the article Identical particles is not mentioned in "See also". Do you think I should put a link there? Lova Falk (talk) 07:17, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Probably not, because this is a generic property of all quantum particles (and even atoms and small molecules). Maybe subatomic particle should link to it. -- BenRG (talk) 21:53, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Thank you! This is actually a bit shocking. In the articles on neutrons, protons and electrons, the article Identical particles is not mentioned in "See also". Do you think I should put a link there? Lova Falk (talk) 07:17, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- See no-hair theorem for the black hole version of this identity issue. --Sean 14:06, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- They're not quite the same. For example: The two electrons in a helium atom have opposite spin. It's easy to change these differences, however. — DanielLC 15:45, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- No, Daniel, you are wrong. Single-electron states may have opposite spin, but the electrons occupying these states are still identical. If they were not identical (i.e., distinguishable), then the helium atom would have had many more quantum states than it actually has. Both atomic physics and statistical mechanics would have looked very differently if at least some of the electrons were distinguishable. --Dr Dima (talk) 18:25, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- It's more than that. "One electron up and one down" is the same quantum state as "one left and one right" or any other pair of opposite spin directions, so the electrons lose their identities in a more profound way than mere swappability. You don't have two electrons with opposite spins, you just have a compound state with zero spin (a singlet state) that doesn't divide into electrons any more uniquely than a two-liter bottle of soda divides into liters. Still, I think what DanielLC said was reasonable—you can have one electron over here and one over there and none in between, and though they are exchangeable in the wave function they aren't going to swap places with each other by crossing the intervening space. That's a kind of distinguishability, though it's not the technical sense in which the word is used in quantum mechanics. -- BenRG (talk) 21:53, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- No, Daniel, you are wrong. Single-electron states may have opposite spin, but the electrons occupying these states are still identical. If they were not identical (i.e., distinguishable), then the helium atom would have had many more quantum states than it actually has. Both atomic physics and statistical mechanics would have looked very differently if at least some of the electrons were distinguishable. --Dr Dima (talk) 18:25, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Surface tension

What will be the Condition of spreading of one liquid over another and its expression ?Supriyochowdhury (talk) 06:51, 8 May 2009 (UTC) —Preceding unsigned comment added by Supriyochowdhury (talk • contribs) 06:50, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- I'm sorry, but I had trouble understanding your question. Could you try again with a little more detail? Thanks. --Sean 14:08, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- I think Supriyochowdhury is asking for a word for situations like having a layer of oil on top of water, and for the conditions that permit this to happen. I don't know the answers, though. Looie496 (talk) 15:58, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

== I want to about spreding coefficient $ba (where liquid b spread over liquid a)of a liquid and how can I derived.Supriyochowdhury (talk) 17:54, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

British bird identification/song question

There is a bird outside one of the places I reside frequently which makes a "doo-deladoo-delaadoo" (sorry for the crappy transcription) song over and over again, with the pitch going up and then it making a thrush sort of strangled noise, for long periods of time, most of the day. It will occassionally switch a bit, but this is what it does at least 90% of the time. It's been going on for a few months, at least, even into night sometimes. The place is a housing estate, but it backs out onto some wild scrubland/wooded area. First guess would be a blackbird but if so, why does it seemingly have such a restricted singing voice? Thanks for any answers 82.26.198.108 (talk) 07:38, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Sounds a bit like a wood pigeon to me, check out the audio file in the article, it certainly has a very repetitive call. Mikenorton (talk) 07:58, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Or try [2]. Bazza (talk) 13:29, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Common Blackbird#Behaviour mentions the fact that some of them imitate noises and other things they heard in their song. (OR: There used to be one near my aunt's home that did a bit of a Mozart tune followed by a motor saw.)71.236.24.129 (talk) 13:25, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- It probably is a blackbird. Maybe it's just not very good at music. Nothing else sticks out of the songs I tried on the RSPB site and it's definitely not a wood pigeon. Thanks for the help everyone! 82.26.198.174 (talk) 19:15, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Common Blackbird#Behaviour mentions the fact that some of them imitate noises and other things they heard in their song. (OR: There used to be one near my aunt's home that did a bit of a Mozart tune followed by a motor saw.)71.236.24.129 (talk) 13:25, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Or try [2]. Bazza (talk) 13:29, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Now that I read your description of the song as if sung by a blackbird, then it does sound like a blackbird. They have different calls - this is not their alarm call, but sounds like the call I recall hearing when all is peaceful. 78.146.17.231 (talk) 17:03, 16 May 2009 (UTC)

Identifying a tree

Can someone identify the species of the large tree growing directly in front of the building in this image? Thanks! LANTZYTALK 08:04, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Podocarpus perhaps? Where was this photograph taken?CalamusFortis 15:32, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Detective work says at Gujurat University in Ahmedabad, India. Looie496 (talk) 16:05, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Podocarpus seems very plausible. Thanks! LANTZYTALK 17:16, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

Magnatite and hydrochloric acid

All of my searches to date indicate that magnatite dissolves slowly in hydrochloric acid, but no time frame. Does anyone now the time to dissolve, cold and warm —Preceding unsigned comment added by 86.137.11.144 (talk) 08:59, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Speed of dissolving will depend on much more than the identity of the substances involved. For example, ground magnetite will dissolve much faster than a solid chunk, and a stirred solution will dissolve much faster than one left to sit idle. It will also depend on the concentration of the HCl, and as you thought, on the temperature. There are just far too many factors to give a definitive answer, variations of any one of these could change the speed of the reaction by orders of magnitude. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 00:05, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- From testing in lab: 3M HCL will dissolve magnetite powder almost instantly at RT, useful for cleaning. But 1M HCl has to be left at least a few hours, and more dilution solutions can take weeks, to the extent that it is no problem for washing to remove basic residues.YobMod 10:17, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

Random number

Can humans generate perfectly random numbers between any two arbitrary limits? - DSachan (talk) 09:43, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Our page Random_number_generator_attack#Human_generation_of_random_quantities may help. 194.221.133.226 (talk) 10:19, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- It all comes down to what you define "random number" to be. --98.217.14.211 (talk) 10:23, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- (ec):No humans can't. It is well known that when humans are asked to pick numbers at random, they are strongly biased to particualr numbers, a fact often made use of by stage magicians. Computer algorithms for generating pseudo-random numbers are not truly random, but appear to be so for all practical purposes because the algorithm is seeded by a continuously changing number such as the time and date. One of the best hardware methods for producing random numbers is to amplify thermal noise. However, even this is not truly random since the signal must necessarily be band-limited which slightly biases against large differences in successive numbers over short intervals. There is also the question of what is meant by random. If the requirement is to build a machine that can output integers within a certain range with equal probability then a machine can be built to approximate to this. If the requirement is to output any real number randomly between two limits then no finite machine is capable of doing this. The reason is that there are infinitely many numbers between any two points. Any real (finite) machine will have a finite resolution and cannot possibly represent all of them, only a finite number of them. In fact, a digital machine is only able to represent rational numbers and these have a zero probability of occuring in a true random sequence of numbers even if the machine was capable of producing any of the infinite rational number between the stated limits. Why? because there are infinitely more irrational numbers in any interval than there are rational numbers, even though the number of both is infinite. SpinningSpark 10:30, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- When discussing "true random", an example I give that tends get the point across is that a true random number generator programmed to output true random numbers between 0 and 9 should have the possibility of outputting 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ... The point is that it is truly random. Even if every number previously has been 1, the chance that the following number will be 1 is just as high as every other number. So, a generator that ensures the distribution of numbers is equal is not truly random. -- kainaw™ 13:24, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- That's true, but actual (computer) pseudorandom number generators don't try to even things out—they're just as likely to produce long sequences of ones as real random number generators are.

- When discussing "true random", an example I give that tends get the point across is that a true random number generator programmed to output true random numbers between 0 and 9 should have the possibility of outputting 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ... The point is that it is truly random. Even if every number previously has been 1, the chance that the following number will be 1 is just as high as every other number. So, a generator that ensures the distribution of numbers is equal is not truly random. -- kainaw™ 13:24, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Computers aren't limited to rational numbers. They can work with numbers of the form where a and b are rational, for example. More interestingly they can represent the whole collection of computable reals. Computable real arithmetic systems work by successive approximation, and there's no reason you couldn't add genuine uncomputable random reals to such a system if you have a random oracle available in hardware. /dev/random is supposed to give you genuine quantum randomness, so it should work. -- BenRG (talk) 14:20, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- True, but the point stands - computable numbers are still only countable (the same size as the rationals), so you can still be almost certain that a number chosen at random from a bounded interval with a uniform distribution will not be computable. I don't see how you can add uncomputable numbers to a computer system, a computer can only work to finite precision. You might be able to fiddle around and extend the set of computable numbers a bit, but you won't stop it being countable. --Tango (talk) 14:27, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Well, there's no real number that you can prove won't occur (exactly) in an exact-real-arithmetic system running on a machine with /dev/random. It may be philosophically dubious, but I don't think randomness gets any less dubious than that. Sure, a Turing machine with a given oracle can only be in countably many states and will only reach finitely many of those, but by the same token there are only countably many theorems about real numbers in ZFC and only finitely many of those will ever be written down. Only finitely many digits of pi will ever be known to the human race, every formal system has a countable model, etc. Of course, mathematicians never actually generate random numbers, they just reason about what would happen if they did, and computers can do that too. -- BenRG (talk) 20:33, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Only because I wouldn't be able to describe such a number, but that doesn't mean much - almost all real numbers are undefinable. (There are describable numbers that aren't definable real numbers, but I believe the set of all describable numbers is still countable, by even the broadest definitions - I could be wrong, though.) --Tango (talk) 21:41, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Getting off-topic here a little bit, but I kind of think this is important to repeat: There is no single, mathematically precise, notion of what it means for a real number to be definable. You have to say definable how. This has been the problem from the beginning at the definable real number article, and I have never been able to come up with a truly satisfactory way of making that article both correct and compliant with WP standards. I'm not sure it can be done. The option of campaigning for its deletion has certainly crossed my mind, but that won't make the issues go away; they'll just spread out through other articles, so I don't really think that's a good idea either. --Trovatore (talk) 03:52, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed, but I think any reasonable definition gives you only countably many numbers, so it doesn't really matter in this case. --Tango (talk) 13:21, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Getting off-topic here a little bit, but I kind of think this is important to repeat: There is no single, mathematically precise, notion of what it means for a real number to be definable. You have to say definable how. This has been the problem from the beginning at the definable real number article, and I have never been able to come up with a truly satisfactory way of making that article both correct and compliant with WP standards. I'm not sure it can be done. The option of campaigning for its deletion has certainly crossed my mind, but that won't make the issues go away; they'll just spread out through other articles, so I don't really think that's a good idea either. --Trovatore (talk) 03:52, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Only because I wouldn't be able to describe such a number, but that doesn't mean much - almost all real numbers are undefinable. (There are describable numbers that aren't definable real numbers, but I believe the set of all describable numbers is still countable, by even the broadest definitions - I could be wrong, though.) --Tango (talk) 21:41, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Well, there's no real number that you can prove won't occur (exactly) in an exact-real-arithmetic system running on a machine with /dev/random. It may be philosophically dubious, but I don't think randomness gets any less dubious than that. Sure, a Turing machine with a given oracle can only be in countably many states and will only reach finitely many of those, but by the same token there are only countably many theorems about real numbers in ZFC and only finitely many of those will ever be written down. Only finitely many digits of pi will ever be known to the human race, every formal system has a countable model, etc. Of course, mathematicians never actually generate random numbers, they just reason about what would happen if they did, and computers can do that too. -- BenRG (talk) 20:33, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- True, but the point stands - computable numbers are still only countable (the same size as the rationals), so you can still be almost certain that a number chosen at random from a bounded interval with a uniform distribution will not be computable. I don't see how you can add uncomputable numbers to a computer system, a computer can only work to finite precision. You might be able to fiddle around and extend the set of computable numbers a bit, but you won't stop it being countable. --Tango (talk) 14:27, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Computers aren't limited to rational numbers. They can work with numbers of the form where a and b are rational, for example. More interestingly they can represent the whole collection of computable reals. Computable real arithmetic systems work by successive approximation, and there's no reason you couldn't add genuine uncomputable random reals to such a system if you have a random oracle available in hardware. /dev/random is supposed to give you genuine quantum randomness, so it should work. -- BenRG (talk) 14:20, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- It also depends on what you mean by "generate", as a human certainly can build a Geiger counter which s/he can then use to generate perfectly random numbers. A human can also shuffle a deck of cards pretty well, which can also generate good quality random numbers. --Sean 14:11, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Geiger counters are not perfectly random in the mathematical sense and humans probably cannot shuffle as well as you think they can. SpinningSpark 19:42, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

When two waves intercept at a right angle

Do they interfere with each other? If yes, what types of waves interfere with each other?--Mr.K. (talk) 11:21, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, you will get additive interference just as any other case which combines waves. If you know the wavefunction for each wave, you can do a point-by-point combination of the phase for each wave, to determine the resulting total wave amplitude. The interference pattern will depend on whether you have two plane waves, wave-packets, or something else; in the case of two plane waves at right-angles, your interference pattern will be sort of "checkerboard-like" with constructive and destructive interference. Nimur (talk) 12:24, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- It depends what you mean by "interfere". There will be interference in the sense of transient superposition, as described by Nimur, but not necessarily interference in the sense of a permanent distortion. Gandalf61 (talk) 12:29, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- OK, if I put two lasers each one intercepting the other at 90 degrees. Will they affect each other in any way? (even if for practical purposes, it's irrelevant).--Mr.K. (talk) 17:11, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Did you see our article on interference? They will affect one another, in the region of intersection; but if you were to measure/observe one of the beams outside the region of intersection, you wouldn't be able to tell that it had "crossed" with another beam. If you do the mathematics of adding the sine-waves and solve the wave equation, you will find this result is physically consistent. Nimur (talk) 19:42, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- In quantum electrodynamics there is an interaction between the beams, mediated by virtual electrons (the simplest Feynman diagram is this one). It's a small effect but it's large enough to be detectable. In principle there's a very tiny gravitational attraction too. Roughly speaking, though, they just pass through each other. -- BenRG (talk) 20:15, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- If they are in a non linear material you may get non linear optics effects with modulation harmonics or mixing occurring. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 09:02, 17 May 2009 (UTC)

youtube

How does this work

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3kyNGVK-hI

Thanks--Mudupie (talk) 11:21, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- I've only watched the first minute or so, but it looks genuine to me. I imagine if one were to beat box into a flute (with sufficient skill) that is what it would sound like. --Tango (talk) 11:30, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- I agree, it's probably genuine. As for how it works, well the flute works by acoustic resonance, and the beat-boxing is sort of augmented by the percussive effect of the microphone amplifier clipping. Nimur (talk) 12:27, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

mWS in a mesurement of pressure drop

What´s means "mWS" in a mesumement of pressure drop or in a indication of pressure drop of a equipment? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Gigobqto (talk • contribs) 15:31, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- It is metres of water (approx 104 Pa, see Conversion of units#Pressure or mechanical stress) but I do not know what the "S" stands for. In the unit mW(g), the g stands for guage pressure, meaning the pressure is metres of water relative to atmospheric pressure, so I would surmise that mWS is measured relative to something else.

Perhaps vacuum or negative guage pressure?SpinningSpark 16:19, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Ah found it on German Wikipedia, it's metres Wassersäule which if my useless technical German is not letting me down means column of water. It seems to be used exclusively for pressure differences, such as the pressure drop along a supply pipe, and is distinguished from both absolute pressure and guage pressure. SpinningSpark 17:33, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

buffer solution

Hi I have been asked to write a symbol balanced equation for equilibrium of a buffer solution of 0.6 mol of propanoic acid and 0.8 mol of sodium propanoate. Would the answer be: CH3CH2COOH (reversable arrows) CH3CH2COO- + H+? I'm guessing its not CH3CH2COO-,Na+ (reversable arrows) CH3CH2COO-+Na+ because the next question is asking for a balanced symbol equation for the dissociation of sodium propanoate. Please help! —Preceding unsigned comment added by 92.18.81.46 (talk) 15:39, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Looks good to me! Not that you mentioned it, but you may find Buffer solution and Henderson–Hasselbalch equation to be relevent reading. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 20:37, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- So. Balanced symbol equation. What's that then? Even google thinks we might not know. --Tagishsimon (talk) 00:10, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

Speed of magnetic and electric fields

What are the speeds of the magnetic field and electric field? Can we treat their speeds like that of an electromagnetic wave? --Email4mobile (talk) 17:27, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Generally speaking electric and magnetic fields are not going anywhere at all unless the source of the field is itself moving. What does move is a disturbance in the field and such disturbances are called electromagnetic waves. The speed of these disturbances is c, the speed of light. Also note that there are not really separate electric and magnetic fields, but only the electromagnetic field, and the two are united through the Lorentz transformation. SpinningSpark 17:56, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Thanks S Spinningspark for this explanation, but how can I describe the attraction and repple forces without accepting that these fields must move like radiation. For example If I've a giant magnet and another giant magnet was passing by very fast causing the nearest distance between them to be let's say 300,000 km. Will the maximum attraction|repple force take place at that position or after the magnet has passed by another distance proportional to its velocity? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Email4mobile (talk • contribs) 18:27, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- First of all, it is wrong to think of the magnetic field being solidly attached to the magnet and moving with it through space. Rather, the magnet is causing causing a disturbance in the field as it moves through it. That disturbance is propagated through the field and finally arrives at the second magnet. As for where the moving magnet is when the maximum effect is felt at the stationary magnet: ask yourself this, if instead of a moving magnet we have a moving star, where is the star when the maximum light from it is seen at the fixed position? SpinningSpark 19:10, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- It works surprisingly well to think of the field as being solidly attached to the magnet. When you push on a solid object the rest of it doesn't move instantly, there's a ripple effect through the object at the speed of sound. The magnetic field acts in a similar way, with the radiation being the ripple. When you stop pushing, the object eventually returns to its original shape, and the same happens to the field. I think possibly you (the original poster) are wondering how much the magnet's field lags behind the magnet when the magnet is moving. The (somewhat surprising) answer is that it doesn't lag at all, as long as the speed is constant. The maximum force between the magnets will be at the point of closest approach (which is the same from the rest frame of either magnet). The star is different—the maximum intensity of light will be somewhat before the time of closest approach. -- BenRG (talk) 21:19, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Thank you BenRG and Spinningspark. Indeed the reason, I raised that question was that I was wondering why a conductor has to cut the magnetic lines in order for the e.m.f to be produced. If we think about massive bodies and the fields we will find that massive bodies have a relative motion (example rotating Earth and its movement around the Sun and the Galaxy, meanwhile the fields must have an absolute motion?. If so then why should the motion or disturbance be created in the conductor for example manually to get this emf?--Email4mobile (talk) 23:24, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

Carbon Dioxide and Dry Ice

Is carbon dioxide inert and is Carbon Dioxide in its solid form, Dry Ice inert? THX —Preceding unsigned comment added by Jzeilhofer (talk • contribs) 19:03, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- "Inert" is always relative:) Carbon dioxide is a common material used to extinguish fires (the fire extinguishers with a black plastic cone-shaped nozzle, for example), and they produce both the gas and solid forms. But burning magnesium reacts (quite spectacularly sometimes) with it. It dissolves in water (carbonated beverages) and dissolves in and/or binds to many biological components (carried by blood). And plants consume and chemically react CO2 (photosynthesis). Solid vs liquid is still the same chemical, just colder and "more of it" present in the same measured volume. So dry ice reacts more slowly (many reactions go slower at lower temperature) but for reactions that do occur. DMacks (talk) 19:10, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

- Definitely not inert by a simple chemistry perspective, in which Oxygen is reactive and Nitrogen is inert (even if many reactions of N2 are known, they are relatively few). User:DMacks mentions Mg, but CO2 should never be used on any metal fires, due to its reactivity. It also reacts with water, forming carbonic acid, and is involved in many organic chemistry reactions (carboxylations). It will also act as a ligand in metal complexes, and can be reduced. In most lab conditions, it sublimes quickly, so while the solid form is easier to store, in terms of (non-cryonic) chemistry it is equally reactive. YobMod 11:45, 14 May 2009 (UTC)

Aluminium in tap water, tea, vegetables, and foods?

How much of the aluminium/aluminum in tea is due to the aluminium in the tap water from which it is made? And are there any vegetables which have significantly more aluminium in them than other vegetables? What about other foods? 89.240.209.79 (talk) 21:21, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

I'm not sure of tea but this site (http://www.eatwell.gov.uk/healthissues/factsbehindissues/aluminium/) has some info - it seems to suggest that it is from the water and soil. On the basis of water-based i'd guess that more water-y veg (e.g. Cucumber) would have more aluminium than 'drier' veg. ny156uk (talk) 21:30, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

May 9

Cockatiel Blues

What do you guys think of this? Is this Cocktatiel really performing a spontaneous blues improvisation? --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 00:29, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- No doubt the bird has heard that tune played 546 times and learned to imitate it. Along the same lines, have you seen Snowball (Cockatoo)? Looie496 (talk) 02:17, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yep, I'm certainly aware of Snowball and others like him. I actually started that article... ;) It seems that parrots really do have some appreciation of human music... --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 16:20, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

Thought Experiment: Perpetual Energy

Of all the systems in a car, I believe the brakes are the most amazing. They will reliaby work just the same with no gas and a dead battery. With a minor press on a pedal, 2000 lbs of automobile will come careening to a dead stop from 100 mph in just a few dozen feet. I had no idea my foot was that strong!

I understand that liquids can't be compressed and that is the "magic" of hydraulics. My question is: what would happen if that same effortless press on a pedal was used to power up turbines instead of stopping a giant machine barrelling at ungodly speeds? Surely the energy produced would be able to overtake the effortless pedal press with more to spare! Sappysap (talk) 01:55, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

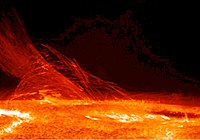

- You seem to be confused about either the first or the second law of thermodynamics. The first says that energy is conserved. The kinetic energy of the car doesn't just disappear, neither does it go into your foot. The brakes convert the kinetic energy into heat (for example by pressing a disk against the wheel and letting friction slow it down). See File:Ceramic brakes.jpg for a striking visual manifestation of this heat.

- The second law says that entropy always increases, or in less precise and more practical terms, energy can't be converted back from heat. This is why it's impossible to make a brake go in reverse and spin up a turbine rather than slowing something down. Braking a car is an inherently irreversible process, because the entropy increases so much. —Keenan Pepper 02:55, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- And just so we're clear, hydraulic brakes aren't fundamentally different from any other brake system. Ultimately, they also convert kinetic energy into heat by means of friction. The hydraulics simply transfer the kinetic energy before it is turned into heat. —Keenan Pepper 03:00, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- (Edit conflict) You seem to have confused two separate sets of energy. Your "effortless press" uses a small amount of energy generated in the cells of your leg muscles. This merely moves the brake pedal, which through the medium of the hydraulics (perhaps supplemented by servo-motors powered by your car's engine or battery) moves parts of the mechanisms of the Disk brake on each braked wheel, pressing the brake pads against the brake disks. The energy required is small, and is independent of whether your car is moving or not.

- Your moving car, as you are aware, possesses a large quantity of kinetic energy which has been converted from the stored chemical energy of its fuel by its engine. By your lightly pressing the brake pads against the wheels, this kinetic energy is converted by friction into heat: no additional energy is generated by your operation of the brakes. This is not the same as somehow exerting a new large force opposite to the car's motion in order to stop it, which would indeed require an amount of new energy comparable to the car's kinetic energy (though somewhat less as road friction, internal mechanical friction and air drag are already helping to oppose the car's motion). Ask yourself, since energy can neither be created nor destroyed, only converted from one form to another, where would this new energy have come from?

- This form of braking is called Dynamic braking, and the dissipated heat energy (which started as chemical energy in the fuel you paid for) is lost/wasted. In some recent vehicles, some of the energy converted by the brakes in order to slow the car is not dissipated as heat, but converted into a storable form, usually mechanical (for example by spinning up a flywheel) or electrical (in the existing or a supplementary battery), for re-use. This type of brake is called a Regenerative brake, but it too is not somehow creating additional energy, merely saving some of the energy that would otherwise have been lost.

- My explanation has been broadly conceptual, but I expect another responder will set out the relevant physical equations in mathematical form, if that will help. 87.81.230.195 (talk) 03:12, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- The reason you can produce so much force in the brake pads with a fairly light touch of your foot is because your foot moves downwards several inches - but the pads only have to move inwards by a tiny fraction of an inch. That provides the 'mechanical advantage' you need to exert that kind of force...kinda like leverage...but with a liquid. Of course, many cars also have power-assisted brakes - and in that case, power (sometimes from the vacuum system of the engine, sometimes via a hydraulic pump attached driven from the serpentine belt - but increasingly, electrical) is applied to help your foot do the work.

- As others have pointed out, the energy from the cars motion gets converted into heat and is dissipated by the disk (or drum) in the braking system. After a lot of heavy braking, the disks can get so hot they they'll actually glow - and if they get too hot, the hydraulic brake fluid might boil - this is called "brake fade" and it's exceedingly dangerous because the gasses produced by the boiling brake fluid is easily compressible (unlike the liquid which is impossible to compress) - so if the brakes get too hot, when you push down on the pedal, all that happens is that the gasses compress, the brake pads stop moving and quite suddenly you have no brakes!

- That's why on long hills, you should slow down using the engine (down-shifting the gearbox) rather than using the brakes for large amounts of time. If you do have brake fade, then in an emergency, you can gently apply the parking brake - which is typically connected using a cable system that won't suffer from the heating problems. But you have to be pretty careful because you can easily lock up the wheels and put the car into a skid. SteveBaker (talk) 03:30, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

will ... what you are'nt understanding is that work is constant , so that brakes just applied the work you've done in avery

effective way on the wheels , its just like hydrolic machines , belozers , were the engine do more than 3000 rpm will its juut

make the vhicle to left the bocket up less than a meter . its just transfere like 40000 rpm to left the bocket up ward like

a meter. thats it .

you can explain it by imagining the multi speed bicycle , in some speeds you have to cycle you legs two times to revolve the

wheel once , which is easy ... in other cases you need to cycle one time to revolve the wheel 5 times which is too hard ,its

need mush bower than your legs can produce .--Mjaafreh2008 (talk) 10:52, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

MSUD in Adults??

Can an adult have MSUD. Can it be contracted in teen or adult years. What else might be causing this Maple Syrup smell in my sons room and bathroom?? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 68.195.147.98 (talk) 03:03, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Sorry, the Reference Desk doesn't give out medical advice. Please consult a doctor. Tempshill (talk) 03:12, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- The second half of the question is not a request for medical advice, though. There are many things that could be causing maple syrup smell in the room - maybe a stash of hidden pancakes? Nimur (talk) 04:32, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- I'm with Nimur on this one. The substance that is responsible for maple syrup odor - both in pancakes and in MSUD - is sotolone, and, naturally, we have an article about it. --Dr Dima (talk) 07:48, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

Earthquakes

Is it possible to find the centre of an earthquake? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 174.6.144.211 (talk) 03:14, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes - they can measure the arrival time of the seismic waves at remote seismology stations and by comparing those times, figure out where the earthquake was happening. Those shock waves move pretty fast but with accurate clocks, it can be done to a reasonable precision. SteveBaker (talk) 03:17, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Well, to the extent that there is a well-defined "center". Earthquakes, especially big ones, don't happen at a single point. There's a section of the fault that ruptures. So it's more like it happens along a line (in the non-mathematician's use of the word line — for mathematicians that would be a one-dimensional manifold, possibly with boundary :-). --Trovatore (talk) 03:41, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Actually, earthquakes happen (mostly) along a surface, (a two-dimensional manifold, possibly with boundaries.) And the motions vary with time, so we need to ass a third dimension. A classic example would be an earthquake that progresses along a fault. -Arch dude (talk) 07:34, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Also see Epicenter. 71.236.24.129 (talk) 08:59, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Actually, earthquakes happen (mostly) along a surface, (a two-dimensional manifold, possibly with boundaries.) And the motions vary with time, so we need to ass a third dimension. A classic example would be an earthquake that progresses along a fault. -Arch dude (talk) 07:34, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Well, to the extent that there is a well-defined "center". Earthquakes, especially big ones, don't happen at a single point. There's a section of the fault that ruptures. So it's more like it happens along a line (in the non-mathematician's use of the word line — for mathematicians that would be a one-dimensional manifold, possibly with boundary :-). --Trovatore (talk) 03:41, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- The epicentre, as mentioned above which is where the rupture begins. It then propagates within the fault surface until it runs out of stored elastic strain energy. In many cases the epicentre is distinctly offcentre for the rupture e.g. both the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and the 2008 Sichuan earthquake initiated right at one end of the fault segment that moved. We know this because of the distribution of aftershocks, which define pretty exactly the extent of the rupture. In terms of the felt intensity the area with greatest damage is often near the epicentre and for historic earthquakes, that happened before instrumental recordings, this is how the epicentre is estimated. In some earthquakes. however, such as the 2002 Denali earthquake the maximum intensity was felt at the other end of the fault surface that ruptured from the epicentre. That earthquake also illustrates another possible complexity, it began on a thrust fault jumped to the strike-slip Denali Fault before jumping again onto the Totschunda fault, another strike-slip structure. Finally, most earthquakes hypocentres (the actual point of initiation) occur within a small range of depths, normally 10-15 km, known as the seismogenic layer. This is the strongest part of the crust, as increased confining pressure makes fracturing progressively more difficult until the temperature rises sufficiently for ductile processes to become important. Most of the rupture propagation, therefore, occurs either laterally or upwards, so if you looked at the area that slipped, the epicentre is often nowhere near the centre of the rupture at all. Mikenorton (talk) 12:29, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

Are convergent, divergent, collisional, and transform boundaries fault lines? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 174.6.144.211 (talk) 04:20, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- All types of plate boundaries have faults associated with them, but only for some of them is there a single fault surface along the boundary itself. Subduction zones pretty much act as simple fault surfaces, as do transforms in oceanic crust. Some continental transforms such as the Alpine Fault in New Zealand, form single fault surfaces along the boundary but others, such as the San Andreas Fault form part of a deformed zone within which there are many active faults. Divergent boundaries in continental crust form rifts with many active normal faults, such as the East African Rift. Collisional zones such as the Himalayas have huge zones of deformation, sometimes 100s of km across, within which there are many seismically active fault zones. Mikenorton (talk) 11:51, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

I know that it is possible to calculate the depth of a hypocenter by using p waves, but is it possible to calculate the location of a hypocenter? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 174.6.144.211 (talk) 23:31, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

Electric circuit for highpower sawtooth wave output.

I need a sawtooth wave generator and i've searched the internet for it; but all the circuit i found have very low current output.The output i need is shown in fig.

Where can i find my desired circuit diagram? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Shamiul (talk • contribs) 04:06, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- You're going to need a pretty hefty amplifier. Have you considered a PA system connected to a signal generator? You could take the output off the speaker-lines and connect it to whatever your load is. My back-of-the-envelope calculations are suggesting that this is going to need an average power output of around 600 watts, which is awfully big for an audio system. Are you really sure you need 25 amps at 40 volts? Nimur (talk) 04:30, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

Thank you for your answer, but i don't mean amplifier. The main circuit should deliver the output required that can be directly delivered to the load. I want to know the procedure that you used to calculate the power output, in case if i had made mistakes. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 123.49.45.67 (talk) 04:57, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Nimur appears to have arrived at the power requirement by a standard RMS integration of the voltage waveform multiplied by 25 amps. However, in his audio amp solution the 5 volt offset would have to be added back after the amp because audio amps do not usually pass dc, the required power rating of the amp is therefore a little less. You do not say why this is not an acceptable solution, and without details of your application it is difficult to give you precise help. Possibly bandwidth is a concern, 10kHz would certainly go through a high quality audio amp but the harmonics are likely to get mangled, badly distorting the waveform from linear. There are certainly plenty of audio amps out there in the right power range at affordable prices. In any case, any solution is liable to be a low power waveform generator stage plus a power amplifier stage as Nimur says, although the power stage might be just a power transistor working off a 40 volt rail if your waveform generator has an open collector output. I think you will struggle to find a ready made circuit diagram to do this - high voltage ramp circuits were common in the days of crt televisions, but I can't think offhand of many high current applications. So to give you some specific suggestions: for the waveform generator there is the 555 timer which has been around since the stone age and the internet is littered with circuit diagrams and application notes. Here is a page describing some alternative waveform generator ICs. If you need great precision of the waveform then you might want to consider a synthesised arbitrary waveform generator which are available as modules/pcbs from some manufactures. For the output transistor, there are many available with the required current and voltage rating. SpinningSpark 10:37, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, that's how I got it... I think the original questioner should really provide context. When you say you don't want an amplifier, I'm a little worried - because any real circuit which will generate such high voltages and currents IS an amplifier. If you're a novice electronics enthusiast, you should not be playing with kilowatt-scale, high-amperage systems, because they can kill you. (Let's be clear here - 40 volts and 25 amps is deadly). What are you trying to do? With some context we can give you a better and more realistic answer. Nimur (talk) 15:05, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- By the way, when you asked the same question last year your image was deleted for the same reason this one's going to be if you don't put a licence tag on it soon. SpinningSpark 20:35, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- As a retro alternative circuit, how about a 5 volt DC generator in series with a DC generator, the field current of which is regulated by a motor driven rheostat such that it sweeps through the required output voltage? A 600 watt generator is not all that large or expensive. Edison (talk) 01:40, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- That wouldn't be very energy-efficient! Half the power would be burned over the rheostat! You really shouldn't be encouraging resistive-loss as an effective method for generating a desired voltage. This is especially bad if you're really going to pump the output signal at 25 amps through it! That sucker's going to need a heat sink! Nimur (talk) 16:15, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- Is your first name Heath? SpinningSpark 02:15, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

Downshifting vs. braking

Inspired by a SteveBaker answer above: Is it really better to downshift than brake when going down a hill? Won't this cause excess wear on the transmission or gearbox or some other part of the car that, unlike brakes, was not designed to be worn so much? Tempshill (talk) 04:10, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Hmm? I don't see where there's any extra stress on the drivetrain- it's the same as what's going on most of the time while you're driving. Brakes slow you down by friction- the pads wear out as you use them. And they're emphatically not meant to be used constantly for long periods of time, because they'll heat up and fail (see brake fade). The drivetrain is meant to be turning pretty much all the time. Friday (talk) 04:15, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- When I lived in Colorado and Montana I did a lot of mountain driving. I could always tell who the flat-landers were by the excessive amount of brake lights they displayed on the down grade. --jwalling (talk) 04:41, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- In Colorado and Montana you'd also likely have encountered quite a few people driving cars with automatic transmissions. They are a lot more common here than in Europe. 71.236.24.129 (talk) 08:51, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Not exactly the same, but maybe you're interested in jake brake. Shadowjams (talk) 09:02, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- In Colorado and Montana you'd also likely have encountered quite a few people driving cars with automatic transmissions. They are a lot more common here than in Europe. 71.236.24.129 (talk) 08:51, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

i think gears were'nt designed to slow the vhicle , because at high speeds its not right to shift back from the fourth to the

first , and in some cases it could break the sustem . i think its better to use brakes instead except when its dangrous to do

so at high speeds or at mountain roads were such action could cause the car to go off the road .--Mjaafreh2008 (talk) 09:49, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- I live in a mountainous country, where we are taught to always downshift when driving downhill. The article Måbødalen disaster may be of interest. It was in part caused by the bus driver's lack of experience in mountain driving. --NorwegianBlue talk 11:40, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- But you aren't trying to slow the vehicle, you're trying to prevent the vehicle speeding up. That's a very different thing. If you want to slow down, use the brakes, if you want to maintain a constant speed, put the car in the right gear for that speed (which will be a lower gear when going downhill than when on the level). --Tango (talk) 13:27, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Let's be PERFECTLY clear about this. For routine slowing down - brief dabs on the brakes separated by minutes of time, typical in-town driving - then you most certainly should use the brakes. That's what they are there for. However, if you are going to have your foot on and off the brake - or lightly pressing the brake for (let's say) a minute or more - then you're driving extremely dangerously and sooner or later you'll boil your brake fluid and you could very easily DIE as a result of your failure to understand the principles of controlling your vehicle. This most often happens on long downhill sections (but it can happen if you're driving agressively on the freeway at high speeds). In these circumstances, you MUST use the engine to slow yourself down. On a stick-shift, you need to shift down progressively (ignoring the horrific racing noises from the engine!) until your speed is under control - where you want it to be. The engine and transmission most certainly are designed to be able to do this - you aren't damaging it any more than when you stamp on the gas pedal to accelerate away from a stop. On an automatic, taking your foot right off of the gas pedal may be enough - but if you're still accelerating then you need to use the brakes one time to get your speed down - and then put the transmission into '2' or even '1' for the remainder of the hill. People who worry that they are ruining their transmission or engine need to understand that they are ruining their brakes by NOT doing this - heating their brake disks/drums until they are literally glowing red hot is going to cause them to warp and to wear the brake pads prematurely. If you do experience brake fade, the seals on brake slave cylinder can be ruined and you can get all sorts of crud in your brake lines. I can't overstress the importance of this. It's one of the commonest mistakes people make when they aren't used to driving in hilly terrain. Failure to understand how brake fade comes about kills a good number of people every year - you should have paid more attention during driver's ed. classes! SteveBaker (talk) 14:13, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Well, this is a bit exaggerated. It's pretty hard to lose your brakes in a modern, ordinary-sized passenger car, unless they are in bad shape to start with. The danger is only serious for heavy vehicles like trucks or buses, or if you do something really stupid like keeping your foot on the brake while pressing the accelerator. It's definitely better to use engine-braking as much as possible, but you don't have to be paranoid about it. I've numerous times descended steep switchbacky mountain roads where I had to brake the whole way down for thousands of feet -- being in low gear helped of course but only to a limited degree. Looie496 (talk) 17:21, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- [citation needed]? Please quote sources, and re-read Steve's response and the article I linked to. --NorwegianBlue talk 19:11, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- If you were in first and still going too fast then, of course, you have to use the brake, you have no choice, but you were still risking your brakes overheating. --Tango (talk) 20:19, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- You sure have a choice. Try shifting to reverse. --NorwegianBlue talk 20:36, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Ok, you don't have a good choice! --Tango (talk) 21:50, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- You sure have a choice. Try shifting to reverse. --NorwegianBlue talk 20:36, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Well, this is a bit exaggerated. It's pretty hard to lose your brakes in a modern, ordinary-sized passenger car, unless they are in bad shape to start with. The danger is only serious for heavy vehicles like trucks or buses, or if you do something really stupid like keeping your foot on the brake while pressing the accelerator. It's definitely better to use engine-braking as much as possible, but you don't have to be paranoid about it. I've numerous times descended steep switchbacky mountain roads where I had to brake the whole way down for thousands of feet -- being in low gear helped of course but only to a limited degree. Looie496 (talk) 17:21, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- I think we are confusing two different issues: The use of either brakes or the transmission to slow down the car versus the use of either brakes or the transmission to maintain speed on a hill. The brakes should always be used to slow the car down, but the transmission should be used to maintain the proper speed when going down hill. That's because brakes are not designed to be applied for long periods of time, but in short bursts. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 04:36, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- Why do you advise against taking advantage of the engine's ability of slowing down the vehicle, say, when leaving a motorway? Used with proper technique, you can drive very smoothly that way. Combined, of course, with using the brakes. --NorwegianBlue talk 10:44, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- Generally - because brake pads are cheaper to replace than clutches, you should use the brake for short decelerations. But if you aren't concerned about wear and tear, then either approach works and is safe for brief periods. I confess that I use engine braking more than I probably ought. The big issue is only with prolonged use of the brakes - which is just plain dangerous. SteveBaker (talk) 14:20, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- Steve, do you have a reliable source for this advice? Thanks. Axl ¤ [Talk] 06:28, 13 May 2009 (UTC)

- Generally - because brake pads are cheaper to replace than clutches, you should use the brake for short decelerations. But if you aren't concerned about wear and tear, then either approach works and is safe for brief periods. I confess that I use engine braking more than I probably ought. The big issue is only with prolonged use of the brakes - which is just plain dangerous. SteveBaker (talk) 14:20, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- Why do you advise against taking advantage of the engine's ability of slowing down the vehicle, say, when leaving a motorway? Used with proper technique, you can drive very smoothly that way. Combined, of course, with using the brakes. --NorwegianBlue talk 10:44, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

Climate change vs. Global warming

Are there simple guidelines to determine which term should be used in a discussion. In my mind, Global warming is a major cause for the effects of Climate change on regional scales. It's my impression that 'climate change' is used often when 'global warming' would be more accurate. --jwalling (talk) 04:27, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Global warming is one form of climate change (i.e a subset). It's also possible to have global cooling and other forms of climate change. We are currently experiencing massive human induced climate change in the form of global warming which is expect to get worse but obviously when you refer to global warming it doesn't have to refer to this particular instance nor does climate change have to mean global warming. Nil Einne (talk) 04:37, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- The ambiguity of 'climate change' (warming or cooling) supports my view that 'global warming' is more accurate when discussing the current global climate. 'Climate change' is appropriate for an unspecified region or uncertain period of time, but if you do specify a region and a time period which is showing warming, such as the Arctic for the next 10 years, then 'Climate warming' is more accurate. -- jwalling (talk) 05:35, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Well firstly I'm presuming you've already specified on the planet earth and over the past 100 or so years and the next 100 or so years. Otherwise it's still confusing (are we referring to global warming on Venus? 1 billion years ago? 1 billion years from now). But even then arguably anthropogenic global warming (a favourite of denialists) or human-induced global warming is more accurate (or more correctly more precise since global warming is by definition a form of climate change so it's very rare you can be wrong if you specify climate change instead of global warming, it's just that you are not being precise as to what form of climate change you are talking about) since it is what we are observing (not say global warming due to sunspots). If you want to go further, perhaps global warming due primarily to an increase in global greenhouse gas levels as a result of human activities. Even further global warming due primarily to an increase in global greenhouse gas levels as a result of human activities including extensive use of fossil fuels, large scale changes in land use...... I think to some extent both are precise enough. There is only one form of massive global climate change we are currently observing and expect as far as I'm aware and that is global warming. So if you want to talk about climate change from a global sense in the next 100 years then of course that will primarily be about global warming not global cooling or anything else. It also depends on what you're talking about. For example the scientific opinion on climate change is about all climate change we expect in coming years and as I've mentioned this is global warming. Similarly the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is supposed to study all climate change and of course global warming is of primary interest to them. In other words, IMHO it's more a matter of semantics and trying to argue which one is more accurate or perhaps IMHO since as I've already stated more accurate is a bit of a misnomer, which term is better applied to a given situation is mostly a pointless waste of time outside of times where it matters e.g. the naming of wikipedia articles, it's better to concentrate on more important things liking convincing those who are fooled by the denialists that there isn't one big conspiracy and climate change in the form of global warming is happening and is going to cause major problems and yes it is caused primarily by human activity. Nil Einne (talk) 08:46, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- The ambiguity of 'climate change' (warming or cooling) supports my view that 'global warming' is more accurate when discussing the current global climate. 'Climate change' is appropriate for an unspecified region or uncertain period of time, but if you do specify a region and a time period which is showing warming, such as the Arctic for the next 10 years, then 'Climate warming' is more accurate. -- jwalling (talk) 05:35, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- The problem with the terminology is that the increase in greenhouse gasses is causing global warming - but also other kinds of climate change (increased hurricane strength and/or frequency, rising sea levels, changes in drought patterns, etc). So the term "Climate Change" better suits the whole range of problems that are being caused. However, some of these effects are secondary effects of global warming - without global warming, most (if not all) of the other effects wouldn't be happening. However, there is at least ONE other effect that we can describe as "Climate Change" which is totally unrelated to global warming or the greenhouse effect - and that is the destruction of the ozone layer. That was not caused by greenhouse gasses like CO2 and Methane - but instead by Chloroflourocarbons released into the atmosphere. Destruction of the ozone layer causes increases in ultraviolet radiation - which is harmful in all sorts of ways. Worrying about the ozone layer has become less trendy than concern over the greenhouse effect - but it's also a major problem. I think it's reasonable to say then that the term "Climate change" is more encompassing than "Global warming" which is in turn more encompassing than "The Greenhouse effect". So, although I confess to tending to use the terms interchangeably - if we are being super-careful:

- If you are talking about CO2, Methane and other gasses that we're dumping into the upper atmosphere - then you need to talk about "The Greenhouse Effect".

- If you are talking about organohalons, chloroflourocarbons, nitric oxide and related gasses causing destruction of ozone - then "Ozone layer depletion" is the correct term.

- If you are talking about gasses dumped into the lower atmosphere that cause plant destruction and soil pollution as they are washed out of the atmosphere by rain - then you need to talk about "Acid Rain".

- Any or all of the previous three terms could be described as "Atmospheric pollution".

- If you are talking just about the rise in globally and seasonally averaged air temperatures - then you should say "Global Warming" - because there are other causes (and mitigating factors) for that beyond the greenhouse effect - things such as the decrease in the planets' albedo due to melting ice caps and glaciers and the increase in albedo due to the contrails from high flying jet aircraft.

- If you are talking about all of the consequences of all of the things we're doing to the planet's atmosphere and hydrosphere - then "Climate Change" is a more appropriate term - because there are other causes of that - such as changes in water usage patterns and evaporation rates, destruction of the Ozone layer, the effect of large cities creating local hot-spots, etc.

- If your concerns range beyond that, then "Oh Shit!" may be the term of last resort!

- SteveBaker (talk) 13:45, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

marine diesel engine

working of air distributar Bose09 (talk) 07:10, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Diesel engine has some information under medium-speed engines and low-speed engines but it is a bit scanty I'm afraid. SpinningSpark 11:08, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

Kc calculation

"The equilibrium constant, Kc, for the reaction to form ethyl ethanoate from ethanol and ethanoic acid, C2H5OH + CH3CO2H=CH3CO2C2H5 + H2O, at 60 degree Celsius is 4.00. When 1.00 mol each of ethanol and ethanoic acid are allowed to reach equilibrium at 60 degree Celsius, what is the number of moles of ethyl ethanoate formed?" This is the question I have to solve. I know you guys dont do homework questions and I dont want the answer to the question either. I just want to know how I am supposed to solve this question, i.e the working. Thanks. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 116.71.59.203 (talk) 08:38, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Use the first formula given here. yandman 11:50, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

But the question doesn't give the amount of water produced. I cant use that formula. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 116.71.59.203 (talk) 11:57, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- You don't need to be given that...you need to figure it out (at least algebraically) from the info that is given. You're not told "how much ethanol is present at equilibrium" but "how much ethanol is starting before equilibrium has occurred". The amount of reactants are decreased by the identical (considering a stoichiometry of a balanced reaction) that the amount of products increases. I am sure you did examples like this in class or in your textbook. DMacks (talk) 17:37, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

So by "figuring it out", Id say that the amount of water is also 1 mole? I haven't really understood this part. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 116.71.33.115 (talk) 05:10, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

- Maybe and maybe not. You start with 1 mole of starting materials and 0 mole of products (per question as written). As you can see in the reaction, every bit of water that is formed comes from ethanol, so if the full 1 mole of starting material is consumed, you get 1 mole of product, and that would leave leave you with 0 mole of starting material. The whole idea of equlibrium and Kc is that the reaction doesn't run all the way (which would consume all of the starting material) but only runs partway. "Some" starting material gets converted to product, "the rest" remains as starting material. And Kc defines exactly the ratio of those two quantities. You know the total (perhaps SM+P?) and the ratio (formula for Kc and its given value), now solve for the variables. DMacks (talk) 08:07, 10 May 2009 (UTC)

teeth

I have a very weak teeth , i visit alot of dentist by they were'nt alot of help

now after all that advance in evry field , i find it wierd that they had'nt find

asolution for cavity , its brrety simple .

some kind of amouth wash that will produce a thin film at the surface of the tooth

so it wont be in contact with food left , so no cavity will form .

realy i dont think its that hard , we built a space ship , rockets , submarines , airplanes

i think its aprrety easy task .

i said that because i visit the dentist so much , and its frightning each ti.

--Mjaafreh2008 (talk) 09:37, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Okay. Do you have a question? -- Captain Disdain (talk) 10:26, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

Answers removed, after discussion on the talk page.

Mjaafreh2008, as Captain Disdain pointed out, you aren't really asking a question. Please rephrase your question, keeping in mind that we cannot give medical advice. --NorwegianBlue talk 16:55, 11 May 2009 (UTC)

Class of drug

Is Clopidogrel an Anticoagulant? If not what's the difference? (No medical advice.)71.236.24.129 (talk) 11:02, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- In the ATC classification system, clopidogrel has the ATC number B01A C04, and is classified as an antithrombotic agent. This ATC group has its own Wikipedia page: ATC code B01. If you check it out, you'll find that a traditional anticoagulant such as Warfarin is in the same group. The difference is that clopidogrel inibits platelet aggregation, whereas anticoagulants inhibit the proteins necessary for coagulation. --NorwegianBlue talk 11:25, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- (After EC) The usual definition of an anticoagulant is a substance that stops the blood from clotting. Anticoagulants like heparin or warfarin directly affect the clotting factors and prevent the entire process from getting started. Clopidogrel is an antiplatelet drug, which prevents platelet activation, the process by which platelets form a kind of plug to stop bleeding. The drug therefore prevents aggregation of platelets but does not interfere with the rest of the clotting cascade. It may seem a subtle distinction since the end result of both classes of drugs is to interfere with the formation of blood clots, but there are differences in mechanism and what the various drugs are used for, so it's a meaningful separation. --- Medical geneticist (talk) 11:38, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- A difference that also may be of interest is in their indications: clopidogrel is typically used to prevent arterial thrombosis after medical procedures such as the insertion of a coronary stent, anticoagulants are typically used to prevent venous thrombosis. --NorwegianBlue talk 12:00, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks. It's a bit clearer now. 71.236.24.129 (talk) 14:01, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

How a factory works

Is there any book/package/work/whatever that will teach you exactly how a factory works? Or if you want to create a factory you must pick up the pieces from here and there? --Mr.K. (talk) 11:53, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Please clarify: are you asking about a factory or a Factory pattern? --NorwegianBlue talk 12:04, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- If it's the latter: A piece of software that "constructs class instances" (all three of those words having very specific meanings) according to some set of parameters - then you REALLY need to ask this question on the computing section of the ref desk.

- If you're talking about an actual physical factory...then it's still not got much to do with science and you might get a better answer on the miscellaneous desk where there are more people to respond to the question.

- SteveBaker (talk) 13:18, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Every factory is different. Some are highly mechanized, and some are just big empty rooms where people work, sewing or bending sheet metal or some other process. If you have a question about a specific type of factory, we can answer that better. Maybe you would find the machining, assembly line, and manufacturing articles helpful. Nimur (talk) 13:39, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Most factories are based on a Workflow analysis. So if you are thinking of a brick and mortar version that would be a good starting point. Apart from that we'd really have to know what type of factory you're interested in. There are significant differences between building a meat processing plant, a saw-mill or a coffee machine manufacturing plant (OR). Even restrictions on site selection (where you could/should build it) would be quite different. 71.236.24.129 (talk) 13:58, 9 May 2009 (UTC)

- Every factory is different. Some are highly mechanized, and some are just big empty rooms where people work, sewing or bending sheet metal or some other process. If you have a question about a specific type of factory, we can answer that better. Maybe you would find the machining, assembly line, and manufacturing articles helpful. Nimur (talk) 13:39, 9 May 2009 (UTC)