Psilocybin mushroom

Psilocybin mushrooms, also known as psychedelic mushrooms, are mushrooms that contain the psychedelic compounds psilocybin and psilocin. Common colloquial terms include magic mushrooms and shrooms.[1] They are used mainly as an entheogen and recreational drug whose effects can include euphoria, altered thinking processes, closed and open-eye visuals, synesthesia, an altered sense of time and spiritual experiences. Biological genera containing psilocybin mushrooms include Copelandia, Galerina, Gymnopilus, Inocybe, Mycena, Panaeolus, Pholiotina, Pluteus, and Psilocybe. Over 100 species are classified in the genus Psilocybe.

Psilocybin mushrooms may have been used since prehistoric times. They are possibly depicted in Stone Age rock art in Europe and Africa, and have a history of use in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Many cultures have used these mushrooms in their religious rites and ceremonies[citation needed].

History

Early

Archaeological evidence suggests that psilocybin-containing mushrooms have been used by humans since prehistoric times. It has been argued that prehistoric rock art near Villar del Humo, Spain, offers evidence that Psilocybe hispanica was used in religious rituals 6,000 years ago,[2][3] and that art at the Tassili caves in southern Algeria dating from 7,000 to 9,000 years ago may show the species Psilocybe mairei.[2][4][5]

Hallucinogenic species of the psilocybe genus have a history of use among the native peoples of Mesoamerica for religious communion, divination, and healing, from pre-Columbian times to the present day. Mushroom stones and motifs have been found in Guatemala.[6] A statuette dating from ca. 200 AD and depicting a mushroom strongly resembling Psilocybe mexicana was found in a west Mexican shaft and chamber tomb in the state of Colima. A Psilocybe species was known to the Aztecs as teonanácatl (literally "divine mushroom" - agglutinative form of teó (god, sacred) and nanácatl (mushroom) in Náhuatl) and were reportedly served at the coronation of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II in 1502. Aztecs and Mazatecs referred to psilocybin mushrooms as genius mushrooms, divinatory mushrooms, and wondrous mushrooms, when translated into English.[7] Bernardino de Sahagún reported ritualistic use of teonanácatl by the Aztecs, when he traveled to Central America after the expedition of Hernán Cortés.[8]

After the Spanish conquest, Catholic missionaries campaigned against the cultural tradition of the Aztecs, dismissing the Aztecs as idolaters, and the use of hallucinogenic plants and mushrooms, like other pre-Christian traditions, were quickly suppressed.[6] The Spanish believed the mushroom allowed the Aztecs and others to communicate with devils. In converting people to Catholicism, the Spanish pushed for a switch from teonanácatl to the Catholic sacrament of the Eucharist. Despite this history, in some remote areas the use of teonanácatl has remained.[9]

The first mention of hallucinogenic mushrooms in European medicinal literature appeared in the London Medical and Physical Journal in 1799: a man had served Psilocybe semilanceata mushrooms that he had picked for breakfast in London's Green Park to his family. The doctor who treated them later described how the youngest child "was attacked with fits of immoderate laughter, nor could the threats of his father or mother refrain him."[10]

European Use

In 1955, Valentina and R. Gordon Wasson became the first known Caucasians to actively participate in an indigenous mushroom ceremony. The Wassons did much to publicize their discovery, even publishing an article on their experiences in Life in 1957.[11] In 1956 Roger Heim identified the psychoactive mushroom that the Wassons had brought back from Mexico as Psilocybe,[12] and in 1958, Albert Hofmann first identified psilocybin and psilocin as the active compounds in these mushrooms.[13][14]

Inspired by the Wassons' Life article, Timothy Leary traveled to Mexico to experience psilocybin mushrooms firsthand. Upon returning to Harvard in 1960, he and Richard Alpert started the Harvard Psilocybin Project, promoting psychological and religious study of psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs. After Leary and Alpert were dismissed by Harvard in 1963, they turned their attention toward promoting the psychedelic experience to the nascent hippie counterculture.[15]

The popularization of entheogens by Wasson, Leary, authors Terence McKenna and Robert Anton Wilson, and others has led to an explosion in the use of psilocybin mushrooms throughout the world. By the early 1970s, many psilocybin mushroom species were described from temperate North America, Europe, and Asia and were widely collected. Books describing methods of cultivating Psilocybe cubensis in large quantities were also published. The availability of psilocybin mushrooms from wild and cultivated sources has made it among the most widely used of the psychedelic drugs.

At present, psilocybin mushroom use has been reported among some groups spanning from central Mexico to Oaxaca, including groups of Nahua, Mixtecs, Mixe, Mazatecs, Zapotecs, and others.[9] An important figure of mushroom usage in Mexico was María Sabina,[16] who used native mushrooms, such as Psilocybin Mexicana in her practice.

Occurrence

Psilocybin is present in varying concentrations in about 200 species of Basidiomycota mushrooms. In a 2000 review on the worldwide distribution of psilocybin mushrooms, Gastón Guzmán and colleagues considered these to be distributed amongst the following genera: Psilocybe (116 species), Gymnopilus (14), Panaeolus (13), Copelandia (12), Hypholoma (6), Pluteus (6) Inocybe (6), Conocybe (4), Panaeolina (4), Gerronema (2), Agrocybe (1), Galerina (1) and Mycena (1).[17] Guzmán increased his estimate of the number of psilocybin-containing Psilocybe to 144 species in a 2005 review.

Many of these are found in Mexico (53 species), with the remainder distributed in the US and Canada (22), Europe (16), Asia (15), Africa (4), and Australia and associated islands (19).[18] In general, psilocybin-containing species are dark-spored, gilled mushrooms that grow in meadows and woods of the subtropics and tropics, usually in soils rich in humus and plant debris.[19] Psilocybin mushrooms occur on all continents, but the majority of species are found in subtropical humid forests.[17] Psilocybe species commonly found in the tropics include P. cubensis and P. subcubensis. P. semilanceata—considered by Guzmán to be the world's most widely distributed psilocybin mushroom[20]—is found in Europe, North America, Asia, South America, Australia and New Zealand, but is entirely absent from Mexico.[18]

Effects

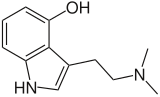

The effects of psilocybin mushrooms come from psilocybin and psilocin. When psilocybin is ingested, it is broken down to produce psilocin, which is responsible for the psychedelic effects.[21] Psilocybin and psilocin create short-term increases in tolerance of users, thus making it difficult to abuse them because the more often they are taken within a short period of time, the weaker the resultant effects are.[22] Psilocybin mushrooms have not been known to cause physical or psychological dependence (addiction).[23]

Poisonous (sometimes lethal) wild-picked mushrooms can be mistaken for psilocybin mushrooms. Poisonous mushrooms can look very similar to certain psyilocybin containing mushrooms, and extreme care is advised when picking them outdoors.

As with many psychedelic substances, the effects of psychedelic mushrooms are subjective and can vary considerably among individual users. The mind-altering effects of psilocybin-containing mushrooms typically last from three to eight hours depending on dosage, preparation method, and personal metabolism. The first 3–4 hours of the trip are typically referred to as the 'peak' in which the user experiences more vivid visuals, and distortions in reality. However, the effects can seem to last much longer to the user because of psilocybin's ability to alter time perception.[24]

In internet surveys, some psilocybin users have reported symptoms of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, although this is uncommon and a causal connection with psilocybin use is unclear.[23] There is a case report of perceptual disturbances and panic disorder beginning after using psilocybin mushrooms in frequent cannabis users with a pre-existing history of derealization and anxiety.[25]

Magic mushrooms were rated as causing some of the least damage in the UK compared to other recreational drugs by experts in a study by the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs.[26] Other researchers have said that psilocybin is "remarkably non-toxic to the body's organ systems", explaining that the risks are indirect: higher dosages are more likely to cause fear and may result in dangerous behavior.[27]

One study found the most desirable results may come from starting with very low doses first, and trying slightly higher doses over months. The researchers explain the peak experiences occur at quantities only slightly lower than a sort of anxiety threshold. Although risks of experiencing fear and anxiety increased somewhat consistently along with dosage and overall quality of experience, at dosages exceeding the individual's threshold, there was suddenly greater increases in anxiety than before. In other words, after finding the optimum dose, returns diminish for using more (since risks of anxiety now increase at a greater rate).[27]

Sensory

Noticeable changes to the auditory, visual, and tactile senses may become apparent around 30 minutes to an hour after ingestion, although effects may take up to two hours to take place. These shifts in perception visually include enhancement and contrasting of colors, strange light phenomena (such as auras or "halos" around light sources), increased visual acuity, surfaces that seem to ripple, shimmer, or breathe; complex open and closed eye visuals of form constants or images, objects that warp, morph, or change solid colours; a sense of melting into the environment, and trails behind moving objects. Sounds seem to be heard with increased clarity; music, for example, can often take on a profound sense of cadence and depth.[citation needed] Some users experience synesthesia, wherein they perceive, for example, a visualization of color upon hearing a particular sound.[28]

Emotional

As with other psychedelics such as LSD, the experience, or "trip", is strongly dependent upon set and setting. A negative environment could contribute to a bad trip, whereas a comfortable and familiar environment would set the stage for a pleasant experience. Psychedelics make experiences more intense, so if a person enters a trip in an anxious state of mind, they will likely experience heightened anxiousness on their trip. Many users find it preferable to ingest the mushrooms with friends, people with whom they are familiar, or people who are familiar with 'tripping'.[29] Users have stated that you can enhance your trip by being in an environment or setting where you are unlikely to panic.

Spiritual and well being

In 2006, the United States government funded a randomized and double-blinded study by Johns Hopkins University which studied the spiritual effects of the active compound psilocybin.[30] The study involved 36 college-educated adults (average age of 46) who had never tried psilocybin nor had a history of drug use, and who had religious or spiritual interests. The participants were closely observed for eight-hour intervals in a laboratory while under the influence of psilocybin.[31]

One-third of the participants reported the experience was the single most spiritually significant moment of their lives, and more than two-thirds reported it was among the top five most spiritually significant experiences. Two months after the study, 79% of the participants reported increased well-being or satisfaction; friends, relatives, and associates confirmed this. They also reported anxiety and depression symptoms to be decreased or completely gone. Fourteen months after the study, 64% of participants said they still experienced an increase in well-being or life satisfaction.

Despite highly controlled conditions to minimize adverse effects, 22% of subjects (8 of 36) had notable experiences of fear or paranoia. All subjects had never taken a hallucinogenic trip before. The authors, however, reported that all these instances were "readily managed with reassurance."[31]

As medicine

Advocates for advanced research in the field of ethnobotany have been asking for medical investigation of the use of synthetic and mushroom-derived psilocybin for the development of improved treatments of various neurological disorders, including chronic cluster headaches, following numerous anecdotal reports of benefits.[32] There are also studies which include reports of psilocybin mushrooms sending both obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD) and OCD-related clinical depression (both being widespread and debilitating mental health conditions) into complete remission immediately and for up to months at a time, compared to current medications which often have both limited efficacy[33] and frequent undesirable side-effects.[34] Recent studies done at Imperial College London, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich conclude, when used properly, psilocybin acts as an antidepressant as suggested by fMRI brain scans.[35][36] The active components of psilocybin mushrooms have also been found to treat alcoholism and other addictions. The drugs potential as treatment to alcoholism is also similar to results found in relation to LSD in the 1950s and 60s.[37]

Dosage

Dosage of mushrooms containing psilocybin depends on the potency of the mushroom (the total psilocybin and psilocin content of the mushrooms), which varies significantly both between species and within the same species, but is typically around 0.5–2.0% of the dried weight of the mushroom. A typical dose of the common species Psilocybe cubensis is about 1.0 to 2.5 g,[38] while about 2.5 to 5.0 g[38] dried mushroom material is considered a strong dose. Above 5 g is often considered a heavy dose.

The concentration of active psilocybin mushroom compounds varies not only from species to species, but also from mushroom to mushroom inside a given species, subspecies or variety. The same holds true even for different parts of the same mushroom. In the species Psilocybe samuiensis, the dried cap of the mushroom contains the most psilocybin at about 0.23%–0.90%. The mycelium contains about 0.24%–0.32%.[39]

Legality

Psilocybin and psilocin are listed as Schedule I drugs under the United Nations 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[40] Schedule I drugs are deemed to have a high potential for abuse and are not recognized for medical use. However, psilocybin mushrooms are not covered by UN drug treaties.

Psilocybin mushrooms are regulated or prohibited in many countries, often carrying severe legal penalties (for example, the US Psychotropic Substances Act, the UK Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and Drugs Act 2005, and in Canada the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act).

Magic mushrooms in their fresh form still remain legal in some countries such as Austria. On November 29, 2008, the Netherlands announced it would ban the cultivation and use of psilocybin-containing fungi beginning December 1, 2008.[41] The UK ban on fresh mushrooms (dried ones were illegal as they were considered a psilocybin-containing preparation) introduced in 2005 came under much criticism, but was rushed through at the end of the 2001-2005 Parliament; until then, magic mushrooms had been sold in the UK.

New Mexico appeals court ruled on June 14, 2005, that growing psilocybin mushrooms for personal consumption could not be considered "manufacturing a controlled substance" under state law. However, it still remains illegal under federal law.[42][43]

While this mushroom has been banned in many countries, it has been legalized in a few others. However, in India narcotics officials are confused. "Magic mushroom contains psilocin which is banned in India, but we cannot arrest people who possess the mushroom because it has not been declared illegal," he said.[44] In India, nonrainy seasons trigger fake mushroom sellers.

See also

Notes

- ^ Kuhn, Cynthia; Swartzwelder, Scott; Wilson, Wilkie (2003). Buzzed: The Straight Facts about the Most Used and Abused Drugs from Alcohol to Ecstasy. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 83. ISBN 0-393-32493-1.

- ^ a b "Earliest evidence for magic mushroom use in Europe". New Scientist. 2 March 2011.

- ^ Akers, B.P., Ruiz, J.F., Piper, A. et al. Econ Bot (2011) 65: 121. doi:10.1007/s12231-011-9152-5

- ^ Rush, John A. (2013). Entheogens and the Development of Culture: The Anthropology and Neurobiology of Ecstatic Experience. North Atlantic Books. p. 488. ISBN 978-1-58394-624-4.

- ^ Samorini, G. (1992). "The oldest representations of hallucinogenic mushrooms in the world (Sahara Desert, 9000–7000 B.P.)". Integration. 2 (3): 69–78.

- ^ a b Stamets (1996), p. 11.

- ^ Stamets (1996), p. 7.

- ^ Hofmann A. (1980). "The Mexican relatives of LSD". LSD: My Problem Child. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 49–71. ISBN 978-0-07-029325-0.

- ^ a b Guzmán G. (2008). "Hallucinogenic mushrooms in Mexico: An overview". Economic Botany. 62 (3): 404–412. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9033-8.

- ^ Brande E. (1799). "Mr. E. Brande, on a poisonous species of Agaric". The Medical and Physical Journal: Containing the Earliest Information on Subjects of Medicine, Surgery, Pharmacy, Chemistry and Natural History. 3: 41–44.

- ^ Wasson RG (1957). "Seeking the magic mushroom". Life (May 13): 100–120. article reproduced online

- ^ Heim R. (1957). "Notes préliminaires sur les agarics hallucinogènes du Mexique". Revue de Mycologie (in French). 22 (1): 58–79.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Hofmann A, Frey A, Ott H, Petrzilka T, Troxler F (1958). "Konstitutionsaufklärung und Synthese von Psilocybin". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (in German). 14 (11): 397–399. doi:10.1007/BF02160424.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Hofmann A, Heim R, Brack A, Kobel H (1958). "Psilocybin, ein psychotroper Wirkstoff aus dem mexikanischen Rauschpilz Psilocybe mexicana Heim". Experientia (in German). 14 (3): 107–109. doi:10.1007/BF02159243. PMID 13537892.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lattin, Don (2010). The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil killed the fifties and ushered in a new age for America (1st ed.). New York: HarperOne. pp. 37–44. ISBN 9780061655937.

- ^ Monaghan, John D.; Cohen, Jeffrey H. (2000). "Thirty years of Oaxacan ethnography". In Monaghan, John; Edmonson, Barbara (eds.). Ethnology. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-292-70881-5.

- ^ a b Guzmán, G.; Allen, J.W.; Gartz, J. (2000). "A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi, an analysis and discussion" (PDF). Annali del Museo Civico di Rovereto: Sezione Archeologia, Storia, Scienze Naturali. 14: 189–280.

- ^ a b Guzmán, G. (2005). "Species diversity of the genus Psilocybe (Basidiomycotina, Agaricales, Strophariaceae) in the world mycobiota, with special attention to hallucinogenic properties". International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 7 (1–2): 305–331. doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v7.i12.

- ^ Wurst et al. (2002), p. 5.

- ^ Guzmán, G. (1983). The Genus Psilocybe: A Systematic Revision of the Known Species Including the History, Distribution, and Chemistry of the Hallucinogenic Species. Beihefte Zur Nova Hedwigia. Vol. 74. Vaduz, Liechtenstein: J. Cramer. pp. 361–2. ISBN 978-3-7682-5474-8.

- ^ Passie, T.; Seifert, J.; Schneider, U.; Emrich, H.M. (2002). "The pharmacology of psilocybin". Addiction Biology. 7 (4): 357–364. doi:10.1080/1355621021000005937. PMID 14578010.

- ^ "Psilocybin Fast Facts". National Drug Intelligence Center. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ a b van Amsterdam, J.; Opperhuizen, A.; van den Brink, W. (2011). "Harm potential of magic mushroom use: A review". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 59 (3): 423–429. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.01.006. PMID 21256914.

- ^ Wittmann, M.; Carter, O.; Hasler, F.; Cahn, B.R.; Grimberg, U.; Spring, P.; Hell, D.; Flohr, H.; Vollenweider, F.X. (2007). "Effects of psilocybin on time perception and temporal control of behaviour in humans". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford). 21 (1): 50–64. doi:10.1177/0269881106065859. PMID 16714323.

- ^ Espiard, M.L.; Lecardeur, L.; Abadie, P.; Halbecq, I.; Dollfus, S. (2005). "Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder after psilocybin consumption: A case study". 20 (5–6). European Psychiatry: 458–460. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.008. PMID 15963699.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sponsored by (2010-11-02). "Drugs that Cause the Most Harm, in The Economist". Economist.com. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- ^ a b "Johns Hopkins probes "Sacred" Mushroom Chemical". Newswise.com. 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- ^ Ballesteros et al. (2006), p. 175.

- ^ Stamets (1996)

- ^ Stafford, P.J. (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Berkeley, California: Ronin Publishing. ISBN 0-914171-51-8.

- ^ a b "Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance" (PDF). Psychopharmacology. 187 (3): 268–283. 2006. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5. PMID 16826400.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Sun-Edelstein, C.; Mauskop, A. (2011). "Alternative headache treatments: Nutraceuticals, behavioral and physical treatments". Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 51 (3): 469–483. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01846.x. PMID 21352222.

- ^ "Effects of Psilocybin in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder".:"In spite of the established efficacy of potent 5-HT reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of OCD ... the length of time required for improvement of patients undergoing treatment with 5-HT reuptake inhibitors appears to be quite long ... and the percentage of patients having satisfactory responses may only approach 50 percent, and most patients that do improve only have a 30 to 50% decrease in symptoms (Goodman et al., 1990)"

- ^ Moreno, Fransisco A.; Wiegland, Christopher B.; Taitano, E. Keolani; Delgado, Pedro L. (2006). "Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Psilocybin in 9 Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (11): 1735–1740.

- ^ Mason, Stuart. "Your brain on 'shrooms: fMRI elucidates neural correlates of psilocybin psychedelic state." Medical Xpress. 29 02 2012:

- ^ Kraehenmann, Rainer. "Psilocybin-Induced Decrease in Amygdala Reactivity Correlates with Enhanced Positive Mood in Healthy Volunteers". Biological Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.010.

- ^ O'neil, Stephanie. "Psychedelic Science: Psilocybin Helps Fight Alcoholism." Southern California Public Radio. KPCC, 19 May 2014. Web.

- ^ a b Erowid (2006). "Dosage Chart for Psychedelic Mushrooms" (shtml). Erowid. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ^ Gartz J, Allen JW, Merlin MD (2004). "Ethnomycology, biochemistry, and cultivation of Psilocybe samuiensis Guzmán, Bandala and Allen, a new psychoactive fungus from Koh Samui, Thailand". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 43 (2): 73–80. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(94)90006-X. PMID 7967658.

- ^ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. August 2003. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ "RTÉ News: 'Shrooms to become illegal in Holland". RTÉ News. November 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ^ "FindLaw | Cases and Codes". caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ "Erowid Psilocybin Mushroom Vault : Legal Status". www.erowid.org. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/madurai/Kodais-magic-shrooms-give-you-a-high/articleshow/49461709.cms

References

- Allen, J.W. (1997). Magic Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Raver Books and John W. Allen. ISBN 1-58214-026-X.

- Ballesteros, S.; Ramón, M.F.; Iturralde, M.J.; Martínez-Arrieta, R. (2006). "Natural Sources of Drugs of Abuse: Magic Mushrooms". In Cole, S.M. (ed.). New Research on Street Drugs. Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 978-1594549618.

- Estrada, A. (1981). Maria Sabina: Her Life and Chants. Ross Erikson. ISBN 978-0915520329.

- Högberg, O. Flugsvampen och människan (in Swedish). ISBN 91-7203-555-2.

- Kuhn, C.; Swartzwelder, S; Wilson, W. (2003). Buzzed: The Straight Facts about the Most Used and Abused Drugs from Alcohol to Ecstasy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32493-1.

- Letcher, A. (2006). Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571227709.

- McKenna, T. (1993). Food of the Gods. Bantam. ISBN 978-0553371307.

- Nicholas, L.G.; Ogame, K. (2006). Psilocybin Mushroom Handbook: Easy Indoor and Outdoor Cultivation. Quick American Archives. ISBN 0-932551-71-8.

- Stamets, P. (1993). Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 1-58008-175-4.

- Stamets, P.; Chilton, J.S. (1983). The Mushroom Cultivator. Olympia: Agarikon Press. ISBN 0-9610798-0-0.

- Stamets, P. (1996). Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-9610798-0-0.

- Wasson, G.R. (1980). The Wondrous Mushroom: Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-068443-0.

- Wurst, M.; Kysilka, R.; Flieger, M. (2002). "Psychoactive tryptamines from Basidiomycetes". Folia Microbiologica. 47 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1007/BF02818560. PMID 11980266.

External links

- The Vaults of Erowid - Psilocybin Mushrooms

- International Legal Status of Psilocybin Mushrooms Ananda Schouten, Erowid, 2004

- Hallucinogenic mushrooms EMCDDA, Lisbon, June 2006

- Hallucinogenic mushrooms: the challenge of responding to naturally occurring substances in an electronic age EMCDDA, Drugs in Focus 15