History of South America: Difference between revisions

→Wars of Independence: added info |

→Wars of Independence: added info |

||

| Line 1,018: | Line 1,018: | ||

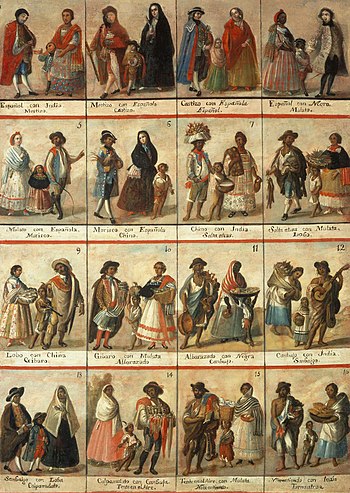

The new republics from the beginning abolished the [[Casta|casta system]], the [[Inquisition]] and [[nobility]], and slavery was ended in all of the new nations within a quarter century. [[Criollo people|Criollos]] (those of Spanish descent born in the New World) and [[mestizo]]s (those of mixed Indian and Spanish blood) replaced [[Peninsulars|Spanish-born]] appointees in most political offices. Criollos remained at the top of a social structure which retained some of its traditional features culturally, if not legally. For almost a century thereafter, [[Liberalism and conservatism in Latin America|conservatives and liberals]] fought to reverse or to deepen the social and political changes unleashed by those rebellions.<ref name="Lynche"/><ref name="ELarousse"/> |

The new republics from the beginning abolished the [[Casta|casta system]], the [[Inquisition]] and [[nobility]], and slavery was ended in all of the new nations within a quarter century. [[Criollo people|Criollos]] (those of Spanish descent born in the New World) and [[mestizo]]s (those of mixed Indian and Spanish blood) replaced [[Peninsulars|Spanish-born]] appointees in most political offices. Criollos remained at the top of a social structure which retained some of its traditional features culturally, if not legally. For almost a century thereafter, [[Liberalism and conservatism in Latin America|conservatives and liberals]] fought to reverse or to deepen the social and political changes unleashed by those rebellions.<ref name="Lynche"/><ref name="ELarousse"/> |

||

Most of the Spanish colonies won their independence in the first quarter of the 19th century, in the wars of independence. [[Simón Bolívar]] ([[Greater Colombia]], [[Peru]], [[Bolivia]]), [[José de San Martín]] ([[United Provinces of the River Plate]], [[Chile]], and [[Peru]]), and [[Bernardo O'Higgins]] ([[Chile]]) led their independence struggle. Although Bolivar attempted to keep the Spanish-speaking parts of the continent politically unified, they rapidly became independent of one another.<ref name="Lynche"/><ref name="W Spence Robertson">William Spence Robertson, "The Juntas of 1808 and the Spanish Colonies," ''English Historical Review'' (1916) 31#124 pp. 573–585 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/551442 in JSTOR]</ref> |

Most of the Spanish colonies won their independence in the first quarter of the 19th century, in the wars of independence. [[Simón Bolívar]] ([[Greater Colombia]], [[Peru]], [[Bolivia]]), [[José de San Martín]] ([[United Provinces of the River Plate]], [[Chile]], and [[Peru]]), and [[Bernardo O'Higgins]] ([[Chile]]) led their independence struggle. Although Bolivar attempted to keep the Spanish-speaking parts of the continent politically unified, they rapidly became independent of one another.<ref name="Lynche"/><ref name="W Spence Robertson">William Spence Robertson, "The Juntas of 1808 and the Spanish Colonies," ''English Historical Review'' (1916) 31#124 pp. 573–585 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/551442 in JSTOR]</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

=====Bolivia===== |

=====Bolivia===== |

||

| Line 1,061: | Line 1,059: | ||

Internal political and territorial divisions led to the secession of Venezuela and Ecuador in 1830.<ref name = "EtHisColombia"/><ref name = "GranColombiaNuevaGranada"/> The so-called "[[Cundinamarca Department (1824)|Department of Cundinamarca]]" adopted the name "[[Republic of the New Granada|Nueva Granada]]", which it kept until 1858 when it became the "Confederación Granadina" ([[Granadine Confederation]]). After a [[Colombian Civil War (1860–1862)|two-year civil war]] in 1863, the "[[United States of Colombia]]" was created, lasting until 1886, when the country finally became known as the Republic of Colombia.<ref name = "HistoriaConstitucional"/><ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/ayudadetareas/poli/poli57.htm|title= Constituciones que han existido en Colombia|publisher= Banco de la República|language = Spanish}}</ref> Internal divisions remained between the bipartisan political forces, occasionally igniting very bloody civil wars, the most significant being the [[Thousand Days' War]] (1899–1902).<ref>{{cite book|title= El país que se hizo a tiros|author= Gonzalo España|publisher= Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial Colombia|isbn = 9789588613901|year= 2013|url= https://books.google.com.co/books?id=IordAgAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false|language= Spanish}}</ref> |

Internal political and territorial divisions led to the secession of Venezuela and Ecuador in 1830.<ref name = "EtHisColombia"/><ref name = "GranColombiaNuevaGranada"/> The so-called "[[Cundinamarca Department (1824)|Department of Cundinamarca]]" adopted the name "[[Republic of the New Granada|Nueva Granada]]", which it kept until 1858 when it became the "Confederación Granadina" ([[Granadine Confederation]]). After a [[Colombian Civil War (1860–1862)|two-year civil war]] in 1863, the "[[United States of Colombia]]" was created, lasting until 1886, when the country finally became known as the Republic of Colombia.<ref name = "HistoriaConstitucional"/><ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/ayudadetareas/poli/poli57.htm|title= Constituciones que han existido en Colombia|publisher= Banco de la República|language = Spanish}}</ref> Internal divisions remained between the bipartisan political forces, occasionally igniting very bloody civil wars, the most significant being the [[Thousand Days' War]] (1899–1902).<ref>{{cite book|title= El país que se hizo a tiros|author= Gonzalo España|publisher= Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial Colombia|isbn = 9789588613901|year= 2013|url= https://books.google.com.co/books?id=IordAgAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false|language= Spanish}}</ref> |

||

=====Peru===== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

A movement was initiated by [[Antonio Nariño]], who opposed Spanish centralism and led the opposition against the [[viceroyalty]].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/29874/1/Antonio%20Nari%C3%B1o-Gutierrez%20Escudero.pdf|title= Un precursor de la emancipación americana: Antonio Nariño y Álvarez.|author = Gutiérrez Escudero, Antonio|publisher= Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades 8.13 (2005)|pages= 205–220|language = Spanish}}</ref> [[Cartagena, Colombia|Cartagena]] became independent in November 1811.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/revistas/credencial/febrero2010/caribe.htm|title= Independencia del Caribe colombiano 1810-1821|author = Sourdis Nájera, Adelaida|publisher= Revista Credencial Historia - Edición 242|language = Spanish}}</ref> Took place the formation of two independent governments which fought a civil war – a period known as the [[Foolish Fatherland]].<ref>{{cite book|title= La patria boba. Cuadernillos de historia|author= Ocampo López, Javier|publisher= Panamericana Editorial|isbn = 9789583005336|year= 1998}}</ref> In 1811 the [[United Provinces of New Granada]] were proclaimed, headed by [[Camilo Torres Tenorio]].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.banrepcultural.org/node/88606|title= Confederación de las Provincias Unidas de la Nueva Granada|author = Martínez Garnica, Armandao|publisher= Revista Credencial Historia - Edición 244|year =2010|language = Spanish}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor-din/acta-de-federacion-de-las-provincias-unidas-de-la-nueva-granada-27-de-noviembre-de-1811--0/html/008e5574-82b2-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_2.html#I_0_|title= Acta de la Federación de las Provincias Unidas de Nueva Granada|year = 1811|language = Spanish}}</ref> Despite the successes of the rebellion, the emergence of two distinct ideological currents among the liberators ([[federalism]] and [[centralism]]) gave rise to an internal clash which contributed to the reconquest of territory by the Spanish. The viceroyalty was restored under the command of [[Juan Sámano]], whose regime punished those who participated in the uprisings. The retribution stoked renewed rebellion, which, combined with a weakened Spain, made possible a successful rebellion led by the Venezuelan-born [[Simón Bolívar]], who finally proclaimed independence in [[1819]].<ref name = "Historia ilustrada de Colombia">{{cite book|title= Historia ilustrada de Colombia - Capítulo VI|author= López, Javier Ocampo|publisher= Plaza y Janes Editores Colombia sa|isbn = 9789581403707|year= 2006|language = Spanish|url= https://books.google.com.co/books?id=XzgpwLiJs5gC&lpg=PA1&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title= Cartagena de Indias en la independencia|publisher= Banco de la República|year= 2011|url= http://www.banrep.gov.co/sites/default/files/publicaciones/archivos/lbr_cartagena_independencia.pdf}}</ref> The [[Royalist (Spanish American Independence)|pro-Spanish resistance]] was defeated in 1822 in the present territory of Colombia and in 1823 in Venezuela.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.cervantes.es/lengua_y_ensenanza/independencia_americana/bicentenario_independencia_calendario.htm|title= Cronología de las independencias americanas|publisher= cervantes.es|language = Spanish}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://revistadeindias.revistas.csic.es/index.php/revistadeindias/article/view/640/706|title= La Constitución de Cádiz en la Provincia de Pasto, Virreinato de Nueva Granada, 1812-1822.|author = Gutiérrez Ramos, Jairo|publisher= Revista de Indias 68, no. 242|page = 222|year = 2008|language = Spanish}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title= La Independencia de Venezuela relatada en clave de paz: las regulaciones pacíficas entre patriotas y realistas (1810-1846).|author= Alfaro Pareja, Francisco José|year= 2013|language = Spanish|url= http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/74784/falfaropareja.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

=====Venezuela===== |

|||

{{Main|Venezuelan War of Independence}} |

|||

[[File:Firma del acta de independencia de Venezuela.jpg|thumb|left|The signing of Venezuela's independence, by [[Martín Tovar y Tovar]]]] |

|||

[[File:BatallaCarabobo01.JPG|thumb|The [[Battle of Carabobo]], during the [[Venezuelan War of Independence]]]] |

|||

After a series of unsuccessful uprisings, Venezuela, under the leadership of [[Francisco de Miranda]], a Venezuelan marshal who had fought in the [[American Revolution]] and the [[French Revolution]], [[Venezuelan Declaration of Independence|declared independence]] on 5 July 1811.<ref>{{cite web |last=Minster |first=Christopher |url=http://latinamericanhistory.about.com/od/independenceinvenezuela/p/10april19venezuela.htm |title=April 19, 1810: Venezuela’s Declaration of Independence |publisher=''About'' |accessdate=30 June 2015}}</ref> This began the [[Venezuelan War of Independence]]. However, a devastating [[1812 Caracas earthquake|earthquake that struck Caracas in 1812]], together with the rebellion of the Venezuelan ''[[llanero]]s'', helped bring down the [[First Republic of Venezuela|first Venezuelan republic]].{{sfn|Chasteen|2001|p=103}} A [[Second Republic of Venezuela|second Venezuelan republic]], proclaimed on 7 August 1813, lasted several months before being crushed, as well.<ref>{{cite web |last=Left |first=Sarah |title=Simon Bolivar |url=http://www.theguardian.com/news/2002/apr/16/netnotes.venezuela |work=The Guardian |date=16 April 2002 |accessdate=30 June 2015}}</ref> |

|||

[[Sovereignty]] was only attained after [[Simón Bolívar]], aided by [[José Antonio Páez]] and [[Antonio José de Sucre]], won the [[Battle of Carabobo]] on 24 June 1821.{{sfn|Gregory|1992|pages=89–90}} On 24 July 1823, [[José Prudencio Padilla]] and [[Rafael Urdaneta]] helped seal Venezuelan independence with their victory in the [[Battle of Lake Maracaibo]].<ref name="ciawfb">{{cite web |url=http://www.ciaworldfactbook.us/south-america/venezuela.html |title=Venezuela |publisher=''CIA World Factbook'' |accessdate=30 June 2015}}</ref> New Granada's congress gave Bolívar control of the Granadian army; leading it, he liberated several countries and founded [[Gran Colombia]].{{sfn|Gregory|1992|pages=89–90}} |

|||

Sucre, who won many battles for Bolívar, went on to liberate Ecuador and later become the second president of [[Bolivia]]. Venezuela remained part of Gran Colombia until 1830, when a rebellion led by Páez allowed the proclamation of a newly independent Venezuela; Páez became the first president of the new republic.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ab55 |title=History of Venezuela |publisher=''History World'' |accessdate=30 June 2015}}</ref> Between one-quarter and one-third of Venezuela's population was lost during these two decades of warfare which by 1830 was estimated at about 800,000.<ref name="Caudillismo">"[http://countrystudies.us/venezuela/5.htm Venezuela – The Century of Caudillismo]". [[Library of Congress Country Studies]].</ref> |

|||

[[File:Abolicion de la esclavitud en Venezuela.jpg|thumb|left|[[José Gregorio Monagas]] abolished slavery in 1854.]] |

|||

[[File:Bolivar Arturo Michelena.jpg|thumb|[[Simón Bolívar]], ''El Libertador'', Hero of the [[Venezuelan War of Independence]]]] |

|||

====Portuguese states===== |

|||

Unlike the Spanish colonies, the Brazilian independence came as an indirect consequence of the Napoleonic Invasions to Portugal - French invasion under General Junot led to the capture of [[Lisbon]] on 8 December 1807. Spanish and Napoleonic forces threatened the security of [[continental Portugal]], causing [[John VI of Portugal|Prince Regent João]], in the name of [[Maria I of Portugal|Queen Maria I]], to move the royal court from [[Lisbon]] to [[Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil|Brazil]],<ref name="Boxer, p. 213">Boxer, p. 213</ref> which was the [[Portuguese Empire]]'s capital between 1808 and 1821 and rose the relevance of [[Brazil]] within the [[Portuguese Empire]]'s framework. Following the Portuguese [[Liberal Revolution of 1820]], and after several battles and skirmishes were fought in Pará and in Bahia, the [[heir apparent]] [[Pedro I of Brazil|Pedro]], son of King [[John VI of Portugal]], proclaimed the country's independence in 1822 and became Brazil's first [[emperor]] (He later also reigned as Pedro IV of Portugal). |

Unlike the Spanish colonies, the Brazilian independence came as an indirect consequence of the Napoleonic Invasions to Portugal - French invasion under General Junot led to the capture of [[Lisbon]] on 8 December 1807. Spanish and Napoleonic forces threatened the security of [[continental Portugal]], causing [[John VI of Portugal|Prince Regent João]], in the name of [[Maria I of Portugal|Queen Maria I]], to move the royal court from [[Lisbon]] to [[Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil|Brazil]],<ref name="Boxer, p. 213">Boxer, p. 213</ref> which was the [[Portuguese Empire]]'s capital between 1808 and 1821 and rose the relevance of [[Brazil]] within the [[Portuguese Empire]]'s framework. Following the Portuguese [[Liberal Revolution of 1820]], and after several battles and skirmishes were fought in Pará and in Bahia, the [[heir apparent]] [[Pedro I of Brazil|Pedro]], son of King [[John VI of Portugal]], proclaimed the country's independence in 1822 and became Brazil's first [[emperor]] (He later also reigned as Pedro IV of Portugal). |

||

Revision as of 22:14, 25 March 2016

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

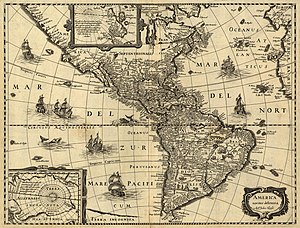

The history of South America is the study of the past, particularly the written record, oral histories, and traditions, passed down from generation to generation on the continent of South America. South America has a history that has a wide range of human cultural and civilisational forms. While millennia of independent development were interrupted by the Portuguese and Spanish colonisation drive of the late 15th century and the demographic collapse that followed, the continent's mestizo and indigenous cultures remain quite distinct from those of their colonisers.

Through the trans-Atlantic slave trade, South America (especially Brazil) became the home of millions of people in the African diaspora. The mixing of races led to new social structures. The tensions between colonial countries in Europe, indigenous peoples and escaped slaves shaped South America from the 16th through the 19th centuries. With the revolution for independence from the Spanish crown during the 19th century, South America underwent yet more social and political changes among them nation building projects, European immigration waves, increased trade, colonisation of hinterlands, and wars about territory ownership and power balance, the reorganisation of Indian rights and duties, liberal-conservative conflicts among the ruling class, and the subjugation of Indians living in the states' frontiers, that lasted until the early 1900s.

Prehistory to Pre-Columbian Era

In the Paleozoic era, South America and Africa were connected. By the end of the Mesozoic, South America was a massive, biologically rich island. Over millions of years, the type of life living in South America became radically different than that of the rest of the world. South America subsequently connected with North America. This caused several migrations of tougher, North American mammal carnivores. The result was that hundreds of South American species became extinct. However, some species were able to adapt and spread into North America. These species include the giant sloths and the terror birds.

The Amazonian rainforest likely formed during the Eocene era. It appeared following a global reduction of tropical temperatures when the Atlantic Ocean had widened sufficiently to provide a warm, moist climate to the Amazon basin. The rainforest has been in existence for at least 55 million years, and most of the region remained free of savanna-type biomes at least until the current ice age, when the climate was drier and savanna more widespread.[1][2] Following the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, the extinction of the dinosaurs and the wetter climate may have allowed the tropical rainforest to spread out across the continent. From 66–34 Mya, the rainforest extended as far south as 45°. Climate fluctuations during the last 34 million years have allowed savanna regions to expand into the tropics. During the Oligocene, for example, the rainforest spanned a relatively narrow band. It expanded again during the Middle Miocene, then retracted to a mostly inland formation at the last glacial maximum.[3] However, the rainforest still managed to thrive during these glacial periods, allowing for the survival and evolution of a broad diversity of species.[4]

During the mid-Eocene, it is believed that the drainage basin of the Amazon was split along the middle of the continent by the Purus Arch. Water on the eastern side flowed toward the Atlantic, while to the west water flowed toward the Pacific across the Amazonas Basin. As the Andes Mountains rose, however, a large basin was created that enclosed a lake; now known as the Solimões Basin.[note 1] Within the last 5–10 million years, this accumulating water broke through the Purus Arch, joining the easterly flow toward the Atlantic.[5][6]

There is evidence that there have been significant changes in Amazon rainforest vegetation over the last 21,000 years through the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and subsequent deglaciation. Analyses of sediment deposits from Amazon basin paleolakes and from the Amazon Fan indicate that rainfall in the basin during the LGM was lower than for the present, and this was almost certainly associated with reduced moist tropical vegetation cover in the basin.[7] There is debate, however, over how extensive this reduction was. Some scientists argue that the rainforest was reduced to small, isolated refugia separated by open forest and grassland;[8] other scientists argue that the rainforest remained largely intact but extended less far to the north, south, and east than is seen today.[9][note 2]

Human activity

Based on archaeological evidence from an excavation at Caverna da Pedra Pintada, human inhabitants first settled in the Amazon region at least 11,200 years ago.[10] Subsequent development led to late-prehistoric settlements along the periphery of the forest by AD 1250, which induced alterations in the forest cover.[11]

For a long time, it was thought that the Amazon rainforest was only ever sparsely populated, as it was impossible to sustain a large population through agriculture given the poor soil. Archeologist Betty Meggers was a prominent proponent of this idea, as described in her book Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise. She claimed that a population density of 0.2 inhabitants per square kilometre (0.52/sq mi) is the maximum that can be sustained in the rainforest through hunting, with agriculture needed to host a larger population.[12] However, recent archeological findings have suggested that the region was actually densely populated. From the 1970s, numerous geoglyphs have been discovered on deforested land dating between 0–1250 AD, leading to claims about Pre-Columbian civilisations.[13] The BBC's Unnatural Histories claimed that the Amazon rainforest, rather than being a pristine wilderness, has been shaped by man for at least 11,000 years through practices such as forest gardening.[14] Recent anthropological findings have suggested that the region was actually densely populated. Some 5 million people may have lived in the Amazon region in AD 1500, divided between dense coastal settlements, such as that at Marajó, and inland dwellers.[15]

The Marajó culture was a pre-Columbian era society that flourished on Marajó island at the mouth of the Amazon River. In a survey, Mann suggests dates between 800 AD and 1400 AD for the culture.[16] Nevertheless, some human activity was documented at these sites already as early as 1000 BCE. The culture seems to persist into the colonial era.[17] Sophisticated pottery—large and elaborately painted and incised with representations of plants and animals—is the most impressive finding in the area and provided the first evidence of complex society on Marajó. Evidence of mound building further suggests well-populated and sophisticated settlements emerged on the island.[18] However, the extent, level of complexity, and resource interactions of the Marajoara culture are disputed. Working in the 1950s, Meggers suggests that the society migrated from the Andes and settled on the island. In the 1980s, Roosevelt led excavations and geophysical surveys of the mound Teso dos Bichos, and concluded that the society that constructed the mounds originated on the island itself.[19] The pre-Columbian culture of Marajó may have developed social stratification and supported a population of 100,000 people.[16] The Native Americans of the Amazon rain forest may have used Terra preta to make the land suitable for the large-scale agriculture needed to support large populations and complex social formations such as chiefdoms.[16]

By 1900 the population had fallen to 1 million and by the early 1980s it was less than 200,000.[15] The first European to travel the length of the Amazon River was Francisco de Orellana in 1542.[20] Unnatural Histories presented evidence that Orellana, rather than exaggerating his claims as previously thought, was correct in his observations that a complex civilisation was flourishing along the Amazon in the 1540s. It is believed that the civilization was later devastated by the spread of diseases from Europe, such as smallpox.[14][15][21][22]

Since the 1970s, numerous geoglyphs have been discovered on deforested land dating between AD 0–1250, furthering claims about Pre-Columbian civilizations.[23][24] Ondemar Dias is accredited with first discovering the geoglyphs in 1977 and Alceu Ranzi with furthering their discovery after flying over Acre.[21][25] The BBC's Unnatural Histories presented evidence that the Amazon rainforest, rather than being a pristine wilderness, has been shaped by man for at least 11,000 years through practices such as forest gardening and terra preta.[21]

One of the main pieces of evidence is the existence of this fertile Terra preta (black earth), which is distributed over large areas in the Amazon forest.[26][note 3] It is now widely accepted that these soils are a product of indigenous soil management. The development of this soil allowed agriculture and silviculture in the previously hostile environment; meaning that large portions of the Amazon rainforest are probably the result of centuries of human management, rather than naturally occurring as has previously been supposed.[27][28] In the region of the Xinguanos tribe, remains of some of these large settlements in the middle of the Amazon forest were found in 2003 by Michael Heckenberger and colleagues of the University of Florida. Among those were evidence of roads, bridges and large plazas.[29]

Terra preta (black earth), which is distributed over large areas in the Amazon forest, is now widely accepted as a product of indigenous soil management. The development of this fertile soil allowed agriculture and silviculture in the previously hostile environment; meaning that large portions of the Amazon rainforest are probably the result of centuries of human management, rather than naturally occurring as has previously been supposed.[note 3][30] In the region of the Xingu tribe, remains of some of these large settlements in the middle of the Amazon forest were found in 2003 by Michael Heckenberger and colleagues of the University of Florida. Among those were evidence of roads, bridges and large plazas.[31]

Origins of indigenous peoples of South America

The Pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European and African influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic to European colonisation during the Early Modern period.[32]

While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus's voyages of 1492 to 1504, in practice the term usually includes the history of American indigenous cultures until Europeans either conquered or significantly influenced them, even if this happened decades or even centuries after Columbus' initial landing.[33] "Pre-Columbian" is used especially often in the context of discussing the great indigenous civilizations of the Americas, such as those of Mesoamerica (the Olmec, the Toltec, the Teotihuacano, the Zapotec, the Mixtec, the Aztec, and the Maya) and those of the Andes (Inca, Moche, Chibcha, Cañaris).

Many pre-Columbian civilizations established characteristics and hallmarks which included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies.[34] Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first significant European and African arrivals (ca. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are known only through oral history and through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with this period, and are also known from historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Mayan, Olmec, Mixtec, and Nahua peoples, had their own written records. However, the European colonists of the time worked to eliminate non-Christian beliefs, and Christian pyres destroyed many pre-Columbian written records. Only a few documents remained hidden and survived, leaving contemporary historians with glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge.

According to both indigenous American and European accounts and documents, American civilisations at the time of European encounter had achieved many accomplishments.[35] For instance, the Aztecs built one of the largest cities in the world, Tenochtitlan, the ancient site of Mexico City, with an estimated population of 200,000. American civilizations also displayed impressive accomplishments in astronomy and mathematics. The domestication of maize or corn required thousands of years of selective breeding.

Inuit, Alaskan Native, and American Indian creation myths tell of a variety of origins of their respective peoples. Some were "always there" or were created by gods or animals, some migrated from a specified compass point, and others came from "across the ocean".[37] Questions about the original settlement of the Americas has produced a number of hypothetical models. The origins of these indigenous people are still a matter of dispute among archaeologists. The traditional view, which traces them to Siberian migration to the Americas at the end of the last ice age, has been increasingly challenged by South American archaeologists. Theories to explain evidence of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact with the Americas by Asian, African, or Oceanic people is generally the topic of significant debate. Demonstrations such as Kon-Tiki and the Kantuta Expeditions demonstrated the ability to travel westward with the Humboldt Current from South America to Polynesia.

The Siberian Ice Age hypothesis

Anthropological and genetic evidence indicates that most Amerindian people descended from migrant people from North Asia (Siberia) who entered the Americas across the Bering Strait or along the western coast of North America in at least three separate waves. In Brazil, particularly, most native tribes who were living in the land by 1500 are thought to be descended from the first Siberian wave of migrants, who are believed to have crossed the Bering Land Bridge at the end of the last Ice Age, between 13,000 and 17,000 years before the present. A migrant wave would have taken some time after initial entry to reach present-day Brazil, probably entering the Amazon River basin from the Northwest. (The second and third migratory waves from Siberia, which are thought to have generated the Athabaskan, Aleut, Inuit, and Yupik people, apparently did not reach farther than the southern United States and Canada, respectively).[citation needed]

An analysis of Amerindian Y-chromosome DNA indicates specific clustering of much of the South American population. The micro-satellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonisation of the region.[38]

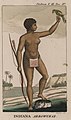

The Australian Aborigines hypothesis

The traditional view above has recently been challenged by findings of human remains in South America, which are claimed to be too old to fit this scenario—perhaps even 20,000 years old. Some recent finds (notably the Luzia skeleton in Lagoa Santa, Minas Gerais, Brazil analyzed by University of São Paulo, Professor Walter Neves) are claimed to be morphologically distinct from the Asian phenotype and are more similar to Australian Aborigines. These Americans would have been later displaced or absorbed by the Siberian immigrants. The distinctive natives of Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of the South American continent, may have been the last remains of those Aboriginal populations.

These early immigrants would have either crossed the ocean on rafts or boats, or traveled North along the Asian coast and entered the Americas through the Bering Strait area, well before the Siberian waves. This theory is still resisted by many scientists chiefly because of the apparent difficulty of the trip. Some proposed theories involve a southward migration from or through Australia and Tasmania, hopping Subantarctic islands and then proceeding along the coast of Antarctica and/or southern ice sheets to the tip of South America at the time of the last glacial maximum.

There is no genetic nor linguistic evidence to support this hypothesis, even though it is plausible that aborigine people that inhabited East Asian shores could have crossed Beringia before the first Siberian waves.

Genetic studies

According to an autosomal genetic study from 2012,[39] Native Americans descend of at least three main migrant waves from East Asia. Most of it is traced back to a single ancestral population, called 'First Americans'. However, those who speak Inuit languages from the Arctic inherited almost half of their ancestry from a second East Asian migrant wave. And those who speak Na-dene, on the other hand, inherited a tenth of their ancestry from a third migrant wave. The initial settling of the Americas was followed by a rapid expansion southwards, by the coast, with little gene flow later, especially in South America. One exception to this are the Chibcha speakers, whose ancestry comes from both North and South America. [39]

Another study, focused on the mtDNA (that which is inherited only through the maternal line),[40] revealed that the indigenous people of the Americas have their maternal ancestry traced back to a few founding lineages from East Asia, which would have arrived via the Bering strait. According to this study, it is probable that the ancestors of the Native Americans would have remained for a time in the region of the Bering Strait, after which there would have been a rapid movement of settling of the Americas, taking the founding lineages to South America.

Linguistic studies have backed up genetic studies, with ancient patterns having been found between the languages spoken in Siberia and those spoken in the Americas.[40]

Two 2015 autosomal DNA genetic studies confirmed the Siberian origins of the Natives of the Americas. However an ancient signal of shared ancestry with the Natives of Australia and Melanesia was detected among the Natives of the Amazon region. The migration coming out of Siberia would have happened 23000 years ago.[41][42]

Genetics

The haplogroup most commonly associated with Indigenous Amerindian genetics is Haplogroup Q1a3a (Y-DNA).[45] Y-DNA, like mtDNA, differs from other nuclear chromosomes in that the majority of the Y chromosome is unique and does not recombine during meiosis. This has the effect that the historical pattern of mutations can easily be studied.[46] The pattern indicates Indigenous Amerindians experienced two very distinctive genetic episodes; first with the initial-peopling of the Americas, and secondly with European colonisation of the Americas.[47][48] The former is the determinant factor for the number of gene lineages and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous Amerindian populations.[48]

Human settlement of the New World occurred in stages from the Bering sea coast line, with an initial 20,000-year layover on Beringia for the founding population.[49][50] The micro-satellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonisation of the region.[51] The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q-M242 (Y-DNA) mutations, however are distinct from other indigenous Amerindians with various mtDNA mutations.[52][53][54] This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later populations.[55]

The genetic history of indigenous peoples of the Americas primarily focuses on Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups and Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups.[56] Autosomal "atDNA" markers are also used, but differ from mtDNA or Y-DNA in that they overlap significantly.[57] The genetic pattern indicates Indigenous Amerindians experienced two very distinctive genetic episodes; first with the initial peopling of the Americas, and secondly with European colonisation of the Americas.[48][58] The former is the determinant factor for the number of gene lineages, zygosity mutations and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous Amerindian populations.[59]

Analyses of genetics among Native American and Siberian populations have been used to argue for early isolation of founding populations on Beringia[60] and for later, more rapid migration from Siberia through Beringia into the New World.[61] The microsatellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonisation of the region.[62] The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit Haplogroup Q-M242; however, they are distinct from other indigenous Amerindians with various mtDNA and atDNA mutations.[52][53][63] This suggests that the peoples who first settled the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations than those who penetrated further south in the Americas.[64][65] Linguists and biologists have reached a similar conclusion based on analysis of Amerindian language groups and ABO blood group system distributions.[66][67][68]

Y-DNA

The Y chromosome consortium has established a system of defining Y-DNA haplogroups by letters A through to T, with further subdivisions using numbers and lower case letters.[69]

- Haplogroup Q

Q-M242 (mutational name) is the defining (SNP) of Haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) (phylogenetic name). Within the Q clade, there are 14 haplogroups marked by 17 SNPs.2009[70][71] In Eurasia haplogroup Q is found among indigenous Siberian populations, such as the modern Chukchi and Koryak peoples. In particular, two groups exhibit large concentrations of the Q-M242 mutation, the Ket (93.8%) and the Selkup (66.4%) peoples.[72] The Ket are thought to be the only survivors of ancient wanderers living in Siberia.[73] Their population size is very small; there are fewer than 1,500 Ket in Russia.2002[73] The Selkup have a slightly larger population size than the Ket, with approximately 4,250 individuals.[74]

Starting the Paleo-Indians period, a migration to the Americas across the Bering Strait (Beringia) by a small population carrying the Q-M242 mutation took place.[75] A member of this initial population underwent a mutation, which defines its descendant population, known by the Q-M3 (SNP) mutation.[76] These descendants migrated all over the Americas.[70]

- mtDNA

Mitochondrial Eve is defined as the woman who was the matrilineal most recent common ancestor for all living humans. Mitochondrial Eve is estimated to have lived between 140,000 and 200,000 years ago,[77][78] Mitochondrial Eve is the most recent common matrilineal ancestor, not the most recent common ancestor.[79][80]

When studying human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups, the results indicated until recently that Indigenous Amerindian haplogroups, including haplogroup X, are part of a single founding east Asian population. It also indicates that the distribution of mtDNA haplogroups and the levels of sequence divergence among linguistically similar groups were the result of multiple preceding migrations from Bering Straits populations.[81] All Indigenous Amerindian mtDNA can be traced back to five haplogroups, A, B, C, D and X.[82]

More specifically, indigenous Amerindian mtDNA belongs to sub-haplogroups A2, B2, C1, D1, and X2a (with minor groups C4c, D2, D3, and D4h3).[60][81] This suggests that 95% of Indigenous Amerindian mtDNA is descended from a minimal genetic founding female population, comprising sub-haplogroups A2, B2, C1b, C1c, C1d, and D1.[82] The remaining 5% is composed of the X2a, D2, D3, C4, and D4h3 sub-haplogroups.[81][82] thumb|left|180px|Karajá Indians in Brazil X is one of the five mtDNA haplogroups found in Indigenous Amerindian peoples. Unlike the four main American mtDNA haplogroups (A, B, C and D), X is not at all strongly associated with east Asia.[73] Haplogroup X genetic sequences diverged about 20,000 to 30,000 years ago to give two sub-groups, X1 and X2. X2's subclade X2a occurs only at a frequency of about 3% for the total current indigenous population of the Americas.[73] However, X2a is a major mtDNA subclade in North America; among the Algonquian peoples, it comprises up to 25% of mtDNA types.[83][84] It is also present in lower percentages to the west and south of this area — among the Sioux (15%), the Nuu-chah-nulth (11%–13%), the Navajo (7%), and the Yakama (5%).[85] Haplogroup X is more strongly present in the Near East, the Caucasus, and Mediterranean Europe.[85] The predominant theory for sub-haplogroup X2a's appearance in North America is migration along with A, B, C, and D mtDNA groups, from a source in the Altai Mountains of central Asia.[86][87][88][89]

Sequencing of the mitochondrial genome from Paleo-Eskimo remains (3,500 years old) are distinct from modern Amerindians, falling within sub-haplogroup D2a1, a group observed among today's Aleutian Islanders, the Aleut and Siberian Yupik populations.[90] This suggests that the colonizers of the far north, and subsequently Greenland, originated from later coastal populations.[90] Then a genetic exchange in the northern extremes introduced by the Thule people (proto-Inuit) approximately 800–1,000 years ago began.[54][91] These final Pre-Columbian migrants introduced haplogroups A2a and A2b to the existing Paleo-Eskimo populations of Canada and Greenland, culminating in the modern Inuit.[54][91]

A 2013 study in Nature reported that DNA found in the 24,000-year-old remains of a young boy from the archaeological Mal'ta-Buret' culture suggest that up to one-third of the indigenous Americans may have ancestry that can be traced back to western Eurasians, who may have "had a more north-easterly distribution 24,000 years ago than commonly thought"[92] "We estimate that 14 to 38 percent of Native American ancestry may originate through gene flow from this ancient population," the authors wrote. Professor Kelly Graf said,

"Our findings are significant at two levels. First, it shows that Upper Paleolithic Siberians came from a cosmopolitan population of early modern humans that spread out of Africa to Europe and Central and South Asia. Second, Paleoindian skeletons like Buhl Woman with phenotypic traits atypical of modern-day indigenous Americans can be explained as having a direct historical connection to Upper Paleolithic Siberia."[citation needed]

A route through Beringia is seen as more likely than the Solutrean hypothesis.[93] An abstract in a 2012 issue of the "American Journal of Physical Anthropology" states that "The similarities in ages and geographical distributions for C4c and the previously analyzed X2a lineage provide support to the scenario of a dual origin for Paleo-Indians. Taking into account that C4c is deeply rooted in the Asian portion of the mtDNA phylogeny and is indubitably of Asian origin, the finding that C4c and X2a are characterised by parallel genetic histories definitively dismisses the controversial hypothesis of an Atlantic glacial entry route into North America."[94]

Archaeology

One of the earliest human remains found in the Americas, Luzia Woman, were found in the area of Pedro Leopoldo, Minas Gerais and provide evidence of human habitation going back at least 11,000 years.[95][96] The earliest pottery ever found in the Western Hemisphere was excavated in the Amazon basin of Brazil and radiocarbon dated to 8,000 years ago (6000 BC). The pottery was found near Santarém and provides evidence that the tropical forest region supported a complex prehistoric culture.[97]

Asian nomads are thought to have entered the Americas via the Bering Land Bridge (Beringia), now the Bering Strait and possibly along the coast. Genetic evidence found in Amerindians' maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) supports the theory of multiple genetic populations migrating from Asia.[98][99] Over the course of millennia, Paleo-Indians spread throughout North and South America. Exactly when the first group of people migrated into the Americas is the subject of much debate. One of the earliest identifiable cultures was the Clovis culture, with sites dating from some 13,000 years ago. However, older sites dating back to 20,000 years ago have been claimed. Some genetic studies estimate the colonisation of the Americas dates from between 40,000 to 13,000 years ago.[73]

The chronology of migration models is currently divided into two general approaches. The first is the short chronology theory with the first movement beyond Alaska into the New World occurring no earlier than 14,000–17,000 years ago, followed by successive waves of immigrants.[100][101][102][103] The second belief is the long chronology theory, which proposes that the first group of people entered the hemisphere at a much earlier date, possibly 50,000–40,000 years ago or earlier.[104][105][106][107]

Wiraquchapampa (Quechua) is an archaeological site with the remains of a building complex of ancient Peru of pre-Inca times. It was one of the administrative centers of the Wari culture. Wiraquchapampa lies about 3.5 kilometres (2.2 miles) north of Huamachuco in Sánchez Carrión Province of the La Libertad Region at an elevation of 3,070 metres (10,072 feet). The site was occupied from the late Middle Horizon 1B time to the first decades of period 2A, according to the chronology established by Dorothy Menzel, taking as reference the classic division of Horizons and Intermediate by John Rowe. These correspond to the 7th and 8th centuries of our era.

Artifacts have been found in both North and South America which have been dated to 14,000 BP,[108] and humans are thought to have reached Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America by this time. The Inuit and related peoples arrived separately and at a much later date, probably during the first millennium CE, moving across the ice from Siberia into Alaska.

By the first millennium, South America's vast rainforests, mountains, plains, and coasts were the home of millions of people. Estimates vary, but 30-50 million are often given and 100 million by some estimates. Some groups formed permanent settlements. Among those groups were the Chibchas (or "Muiscas" or "Muyscas"), Valdivia and the Tairona. The Chibchas of Colombia, Valdivia of Ecuador, the Quechuas and the Aymara of Peru and Bolivia were the four most important sedentary Amerindian groups in South America. From the 1970s, numerous geoglyphs have been discovered on deforested land in the Amazon rainforest, Brazil, supporting Spanish accounts of a complex, possibly ancient Amazonian civilisation.[23][112]

A 2007 paper published in PNAS put forward DNA and archaeological evidence that domesticated chickens had been introduced into South America via Polynesia by late pre-Columbian times.[113] These findings were challenged by a later study published in the same journal, that cast doubt on the dating calibration used and presented alternative mtDNA analyses that disagreed with a Polynesian genetic origin.[114] The origin and dating remains an open issue. Whether or not early Polynesian–American exchanges occurred, no compelling human-genetic, archaeological, cultural or linguistic legacy of such contact has turned up. Terra preta (black earth), which is distributed over large areas in the Amazon forest, is now widely accepted as a product of indigenous soil management. The development of this fertile soil allowed agriculture and silviculture in the previously hostile environment; meaning that large portions of the Amazon rainforest are probably the result of centuries of human management, rather than naturally occurring as has previously been supposed.[note 3] In the region of the Xingu tribe, remains of some of these large settlements in the middle of the Amazon forest were found in 2003 by Michael Heckenberger and colleagues of the University of Florida. Among those were evidence of roads, bridges and large plazas.[31]

Agricultural development & domestication of animals

Early inhabitants of the Americas developed agriculture, developing and breeding maize (corn) from ears 2 to 5 cm (0.8–2.0 inches) in length to the current size are familiar today. Potatoes, tomatoes, tomatillos (a husked green tomato), pumpkins, chili peppers, squash, beans, pineapple, sweet potatoes, the grains quinoa and amaranth, cocoa beans, vanilla, onion, peanuts, strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, blackberries, papaya, and avocados were among other plants grown by natives. Over two-thirds of all types of food crops grown worldwide are native to the Americas.

The natives began using fire in a widespread manner. Intentional burning of vegetation was taken up to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories, thereby making travel easier and facilitating the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants that were important for both food and medicines. This created the Pre-Columbian savannas of North America.[115]

While not as widespread as in other areas of the world (Asia, Africa, Europe), indigenous Americans did have livestock. In Mexico as well as Central America, natives had domesticated deer which was used for meat and possibly even milk. Domesticated turkeys were common in Mesoamerica and in some regions of North America; they were valued for their meat, feathers, and, possibly, eggs. There is documentation of Mesoamericans utilising hairless dogs, especially the Xoloitzcuintle breed, for their meat. Andean societies had llamas and alpacas for meat and wool, as well as for beasts of burden. Guinea pigs were raised for meat in the Andes. Iguanas were another source of meat in Mexico, Central, and northern South America. The first evidence for the existence of agricultural practices in South America dates back to circa 6500 BCE, when potatoes, chilies and beans began to be cultivated for food in the Amazon Basin. Pottery evidence further suggests that manioc, which remains a staple foodstuff today, was being cultivated as early as 2000 BCE.[116]

South American cultures began domesticating llamas and alpacas in the highlands of the Andes circa 3500 BCE. These animals were used for both transportation and meat.[116] Guinea pigs were also domesticated as a food source at this time.[117]

By 2000 BCE, many agrarian village communities had been settled throughout the Andes and the surrounding regions. Fishing became a widespread practice along the coast which helped to establish fish as a primary source of food. Irrigation systems were also developed at this time, which aided in the rise of an agrarian society.[116] The food crops were quinoa, corn, lima beans, common beans, peanuts, manioc, sweet potatoes, potatoes, oca and squashes.[118] Cotton was also grown and was particularly important as the only major fiber crop.[116]

The earliest permanent settlement as proved by ceramic dating dates to 3500 BC by the Valdivia on the coast of Ecuador. Other groups also formed permanent settlements. Among those groups were the Chibchas (or "Muiscas" or "Muyscas") and the Tairona, of Colombia, the cañari of Ecuador, the Quechuas of Peru, and the Aymaras of Bolivia were the 3 most important sedentary Indian groups in South America. In the last two thousand years there may have been contact with Polynesians across the South Pacific Ocean, as shown by the spread of the sweet potato through some areas of the Pacific, but there is no genetic legacy of human contact.[119]

By the 15th century, maize had been transmitted from Mexico and was being farmed in the Mississippi embayment, as far as the East Coast of the United States, and as far north as southern Canada. Potatoes were utilised by the Inca, and chocolate was used by the Aztecs.

Native South American Peoples

Argentina

Argentina has 35 indigenous groups or Argentine Amerindians or Native Argentines, according to the Complementary Survey of the Indigenous Peoples of 2004,[120] in the first attempt in more than a 100 years that the government tried to recognize and classify the population according to ethnicity. In the survey, based on self-identification or self-ascription, around 600,000 Argentines declared to be Amerindian or first-generation descendants of Amerindians, that is, 1.49% of the population.[120] The most populous of these were the Tehuelche, Kolla, Toba, Wichí, Diaguita, Mocoví, Huarpe peoples, Mapuche and Guarani[120] In the 2010 census [INDEC], 955,032 Argentines declared to be Amerindian or first-generation descendants of Amerindians, that is, 2.38% of the population.[121] Many Argentines also claim at least one indigenous ancestor: in a recent genetic study conducted by the University of Buenos Aires, more than 56% of the 320 Argentines sampled were shown to have at least one indigenous ancestor in one parental lineage and about 11% had indigenous ancestors in both parental lineages.[122]

Jujuy Province, in the Argentine Northwest, is home to the highest percentage of households (15%) with at least one indigenous person or a direct descendant of an indigenous people; Chubut and Neuquén Provinces, in Patagonia, have upwards of 12%.[123]

The indigenous population of Argentina have a complex history, from being the majority in what is now the Argentine territory to being outnumbered by a Black majority in the Argentine colonial era and the first decades after the Independence of Argentina, to participating in the great Immigration to Argentina (1850-1955), to almost being completely overwhelmed in proportion to the Argentine total population (after all, Argentina received 6.6 million immigrants, second only to the United States with 27 million, and ahead of countries such as Canada, Brazil, Australia, etc.)[124][125]

In 2005, Argentina's indigenous population (known as pueblos originarios) numbered about 600,329 (1.6% of total population); this figure includes 457,363 people who self-identified as belonging to an indigenous ethnic group and 142,966 who identified themselves as first-generation descendants of an indigenous people.[126][127] The ten most populous indigenous peoples are the Mapuche (113,680 people), the Kolla (70,505), the Toba (69,452), the Guaraní (68,454), the Wichi (40,036), the Diaguita-Calchaquí (31,753), the Mocoví (15,837), the Huarpe (14,633), the Comechingón (10,863) and the Tehuelche (10,590). Minor but important peoples are the Quechua (6,739), the Charrúa (4,511), the Pilagá (4,465), the Chané (4,376), and the Chorote (2,613). The Selknam (Ona) people are now virtually extinct in its pure form. The languages of the Diaguita, Tehuelche, and Selknam nations have become extinct or virtually extinct: the Cacán language (spoken by Diaguitas) in the 18th century and the Selknam language in the 20th century; one Tehuelche language (Southern Tehuelche) is still spoken by a handful of elderly people.

Belize

Mestizos (European with indigenous peoples) number about 34 percent of the population; unmixed Maya make up another 10.6 percent (Ketchi, Mopan, and Yucatec). The Garifuna, who came to Belize in the 19th century, originating from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, with a mixed African, Carib, and Arawak ancestry make up another 6% of the population.[128]

- The Q'eqchi'

Q'eqchi' in the former orthography, or simply Kekchi in many English-language contexts, such as in Belize) are one of the Maya peoples in Guatemala and Belize, whose indigenous language is also called Q'eqchi'.

Before the beginning of the Spanish conquest of Guatemala in the 1520s, Q'eqchi' settlements were concentrated in what are now the departments of Alta Verapaz and Baja Verapaz. Over the course of the succeeding centuries a series of land displacements, resettlements, persecutions and migrations resulted in a wider dispersal of Q'eqchi' communities into other regions of Guatemala (Izabal, Petén, El Quiché), southern Belize (Toledo District), and smaller numbers in southern Mexico (Chiapas, Campeche).[129] While most notably present in northern Alta Verapaz and southern Petén,[130] contemporary Q'eqchi' language-speakers are the most widely spread geographically of all Maya peoples in Guatemala.[131]

- The Mopan

The Mopan are one of the Maya peoples in Belize and Guatemala. Their indigenous language is also called Mopan and is one of the Yucatec Maya languages.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the British forced the Mopan out of Belize and into Guatemala.[132] There they endured forced labour and high taxation.[132] In the late 19th century, many Guatemalan Mopan fled back into Belize, settling in the Toledo District in the southern part of the country.[132][133]

In the 2010 Census, 10,557 Belizeans reported their ethnicity as Mopan Maya. This constituted approximately 3% of the population.[134]

- The Garifuna

The Garifuna are mixed-race descendants of West African, Central African, Island Carib, and Arawak people. The British colonial administration used the term Black Carib and Garifuna to distinguish them from Yellow and Red Carib, the Amerindian population who did not intermarry with Africans. Caribs who had not intermarried with Africans are still living in the islands of the Lesser Antilles. The Island Caribs lived throughout the southern Lesser Antilles, such as present Dominica, St Vincent and Trinidad. Their ancestors are believed to have conquered them from their previous inhabitants, the Igneri.

Since April 12, 1797, the Garifuna people have been living in Central America, where they speak the Garifuna language. The Garifuna people mostly live along the Caribbean Coast of Honduras, but there are also smaller populations in Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. There are also many Garinagu in the United States, particularly in New York City, Los Angeles, Miami, New Orleans, Houston, Seattle, and other major cities.

The Carib people had migrated from the mainland to the islands about 1200, according to carbon dating of artifacts. They largely displaced, exterminated and assimilated the Taino who were resident on the island at the time.[135]

The French missionary Raymond Breton arrived in the Lesser Antilles in 1635, and lived on Guadeloupe and Dominica until 1653. He took ethnographic and linguistic notes on the native peoples of these islands, including St Vincent, which he visited briefly. According to oral history noted by the English governor William Young in 1795, Carib-speaking people of the Orinoco River area on the mainland came to St. Vincent long before the arrival of Europeans to the New World. They subdued the local inhabitants called Galibeis, and unions took place between the peoples.

Bolivia

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (April 2012) |

In Bolivia, a 62% majority of residents over the age of 15 self-identify as belonging to an indigenous people, while another 3.7% grew up with an indigenous mother tongue yet do not self-identify as indigenous.[136] Including both of these categories, and children under 15, some 66.4% of Bolivia's population was registered as indigenous in the 2001 Census.[137] The largest indigenous ethnic groups are: Quechua, about 2.5 million people; Aymara, 2.0 million; Chiquitano, 181,000; Guaraní, 126,000; and Mojeño, 69,000. Some 124,000 belong to smaller indigenous groups.[138] The Constitution of Bolivia, enacted in 2009, recognizes 36 cultures, each with its own language, as part of a plurinational state. Some groups, including CONAMAQ (the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu) draw ethnic boundaries within the Quechua- and Aymara-speaking population, resulting in a total of fifty indigenous peoples native to Bolivia.

Large numbers of Bolivian highland peasants retained indigenous language, culture, customs, and communal organization throughout the Spanish conquest and the post-independence period. They mobilised to resist various attempts at the dissolution of communal landholdings and used legal recognition of "empowered caciques" to further communal organization. Indigenous revolts took place frequently until 1953.[139] While the National Revolutionary Movement government begun in 1952 discouraged self-identification as indigenous (reclassifying rural people as campesinos, or peasants), renewed ethnic and class militancy re-emerged in the Katarista movement beginning in the 1970s.[140] Lowland indigenous peoples, mostly in the east, entered national politics through the 1990 March for Territory and Dignity organised by the CIDOB confederation. That march successfully pressured the national government to sign the ILO Convention 169 and to begin the still-ongoing process of recognising and titling indigenous territories. The 1994 Law of Popular Participation granted "grassroots territorial organizations" that are recognised by the state certain rights to govern local areas.

Some radio and television programs in Quechua and Aymara are produced. The constitutional reform in 1997 recognised Bolivia as a multilingual, pluri-ethnic society and introduced education reform. In 2005, for the first time in the country's history, an indigenous Aymara, Evo Morales, was elected as President.

Morales began work on his "indigenous autonomy" policy, which he launched in the eastern lowlands department on August 3, 2009, making Bolivia the first country in the history of South America to affirm the right of indigenous people to govern themselves.[141] Speaking in Santa Cruz Department, the President called it "a historic day for the peasant and indigenous movement", saying that, though he might make errors, he would "never betray the fight started by our ancestors and the fight of the Bolivian people".[141] A vote on further autonomy will take place in referendums which are expected to be held in December 2009.[141] The issue has divided the country.[142]

Brazil

Indigenous peoples of Brazil make up 0.4% of Brazil's population, or about 700,000 people, even though millions of Brazilians have some indigenous ancestry.[143][144] Indigenous peoples are found in the entire territory of Brazil, although the majority of them live in Indian reservations in the North and Center-Western part of the country. On January 18, 2007, FUNAI reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. With this addition Brazil has now overtaken the island of New Guinea as the country having the largest number of uncontacted tribes.[144]

In a 2007 news story, The Washington Post reported, "As has been proved in the past when uncontacted tribes are introduced to other populations and the microbes they carry, maladies as simple as the common cold can be deadly. In the 1970s, 185 members of the Panara tribe died within two years of discovery after contracting such diseases as flu and chickenpox, leaving only 69 survivors."[145]

- Indigenous people's rights

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution recognises the inalienable right of indigenous peoples to lands they "traditionally occupy",[note 6][146][147] which are demarcated as Indigenous Territories,[146] and automatically confers them permanent possession of these lands. In practice, however, a formal process of demarcation is required for a TI to gain full protection,[147] and this has often entailed protracted legal battles.[148][149][150] Even after demarcation, they are frequently subject to illegal invasions by settlers and mining and logging companies.[147]

There are 672 Indigenous Territories in Brazil, covering about 13% of the country's land area.[151] Critics of the system say that this is out of proportion with the number of indigenous people in Brazil, about 0.41%[152] of the population; they argue that amount of land reserved as TIs undermines the country's economic development and national security.[150][153][154][155] In practice, however, Brazil's indigenous people still face a number of external threats and challenges to their continued existence and cultural heritage.[156] The process of demarcation is slow—often involving protracted legal battles—and FUNAI do not have sufficient resources to enforce the legal protection on indigenous land.[157][148][156][149][150] Since the 1980s there has been a boom in the exploitation of the Amazon Rainforest for mining, logging and cattle ranching, posing a severe threat to the region's indigenous population. Settlers illegally encroaching on indigenous land continue to destroy the environment necessary for indigenous people' traditional ways of life, provoke violent confrontations and spread disease.[156] people such as the Akuntsu and Kanoê have been brought to the brink of extinction within the last three decades.[158][159] 13 November 2012, the national indigenous people association from Brazil APIB submitted to the United Nation a human rights document that complaints about new proposed laws in Brazil that would further undermine their rights if approved.[160]

Chile

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2016) |

According to the 2002 Census, 4.6% of the Chilean population, including the Rapanui of Easter Island, was indigenous, although most show varying degrees of mixed heritage.[161] Many are descendants of the Mapuche, and live in Santiago, Araucanía and the lake district. The Mapuche successfully fought off defeat in the first 300–350 years of Spanish rule during the Arauco War. Relations with the new Chilean Republic were good until the Chilean state decided to occupy their lands. During the Occupation of Araucanía the Mapuche surrendered to the country's army in the 1880s. Their land was opened to settlement by Chileans and Europeans. Conflict over Mapuche land rights continues to the present.

Other groups include the Aymara, the majority of whom live in Bolivia and Peru, with smaller numbers in the Arica-Parinacota and Tarapacá Regions, and the Atacama people (Atacameños), who reside mainly in El Loa.

Beginning in the second half of the 18th century Mapuche-Spanish and later Mapuche-Chilean trade increased and hostilities decreased.[162] Mapuches obtained goods from Chile and some dressed in "Spanish" clothing.[163] Despite close contacts Chileans and Mapuches remained socially, politically and economically distinct.[163] During Chile's first fifty years of independence (1810-1860) the governments relation to the Araucanía territory was not a priority and the Chilean government prioritized the development of Central Chile over its relations with indigenous groups.[164][165]

Between two Chilean provinces (Concepción and Valdivia) there is a piece of land that is not a province, its language is different, it is inhabited by other people and it can still be said that it is not part of Chile. Yes, Chile is the name of the country over where its flag waves and its laws are obeyed

Colombia

Some theories claim the earliest human habitation of South America to be as early as 43,000 BC, although present archaeological understanding places this around 15,000 BC at the earliest. Anthropologist Tom Dillehay dates the earliest hunter-gatherer cultures on the continent at almost 10,000 BC, during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene periods.[167] According to his evidence based on rock shelters, Colombia's first human inhabitants were probably concentrated along the Caribbean coast and on the Andean highland slopes.[167] By that time, these regions were forested and had a climate resembling today's.[167] Dillehay has noted that Tibitó, located just north of Bogotá, is one of the oldest known and most widely accepted sites of early human occupation in Colombia, dating from about 9,790 BC. There is evidence that the highlands of Colombia were occupied by significant numbers of human foragers by 9,000 B.C., with permanent village settlement in northern Colombia by 2,000 B.C.[167]

Colombia's indigenous culture evolved from three main groups—the Quimbayas, who inhabited the western slopes of the Cordillera Central; the Chibchas; and the Kalina (Caribs).[167] When the Spanish arrived in 1509, they found a flourishing and heterogeneous Amerindian population that numbered between 1.5 million and 2 million, belonged to several hundred tribes, and largely spoke mutually unintelligible dialects.[167] The two most advanced cultures of Amerindian peoples at the time were the Muiscas and Taironas, who belonged to the Chibcha group and were skilled in farming, mining, and metalcraft.[167] The Muiscas lived mainly in the present departments of Cundinamarca and Boyacá, where they had fled centuries earlier after raids by the warlike Caribs, some of whom eventually migrated to Caribbean islands near the end of the first millennium A.D.[167] The Taironas, who were divided into two subgroups, lived in the Caribbean lowlands and the highlands of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.[167] The Muisca civilization was well organized into distinct provinces governed by communal land laws and powerful caciques, who reported to one of the two supreme leaders.[167]

A minority today within Colombia's overwhelmingly Mestizo and White Colombian population, Colombia's indigenous peoples consist of around 85 distinct cultures and more than 1,378,884 people.[169][170] A variety of collective rights for indigenous peoples are recognised in the 1991 Constitution.

One of the influences is the Muisca culture, a subset of the larger Chibcha ethnic group, famous for their use of gold, which led to the legend of El Dorado. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Chibchas were the largest native civilization geographically between the Incas and the Aztecs empires.

The Muisca are the Chibcha-speaking people that formed the Muiscan Confederation of the central highlands of present-day Colombia's Eastern Range. They were encountered by the Spanish Empire in 1537, at the time of the conquest. Subgroupings of the Muisca were mostly identified by their allegiances to three great rulers: the Zaque, centered in Chunza, ruling a territory roughly covering modern southern and northeastern Boyacá and southern Santander; the Zipa, centered in Bacatá, and encompassing most of modern Cundinamarca, the western Llanos and northeastern Tolima; and the Iraca, ruler of Suamox and modern northeastern Boyacá and southwestern Santander.

The territory of the Muisca spanned an area of around 47,000 square kilometres (18,147 square miles) - a region slightly larger than Switzerland - from the north of Boyacá to the Sumapaz Páramo and from the summits of the Eastern Range to the Magdalena Valley. It bordered the territories of the Panches and Pijaos tribes.

At the time of the conquest, the area had a large population, although the precise number of inhabitants is not known. The languages of the Muisca were dialects of Chibcha, also called Muysca and Mosca, which belong to the Chibchan language family. The economy was based on agriculture, metalworking and manufacturing.

Costa Rica

There are over 60,000 inhabitants of Native American origins, representing 1.5% of the population. Most of them live in secluded reservations, distributed among eight ethnic groups: Quitirrisí (In the Central Valley), Matambú or Chorotega (Guanacaste), Maleku (Northern Alajuela), Bribri (Southern Atlantic), Cabécar (Cordillera de Talamanca), Guaymí (Southern Costa Rica, along the Panamá border), Boruca (Southern Costa Rica) and Ngäbe (Southern Costa Rica).

These native groups are characterised for their work in wood, like masks, drums and other artistic figures, as well as fabrics made of cotton. Their subsistence is based on agriculture, having corn, beans and plantains as the main crops.

Costa Rican Indigenous Tribes

- Boruca, southern Costa Rica

The Boruca (also known as the 'Brunca or the Brunka) are an indigenous people living in Costa Rica. The tribe has about 2,660 members, most of whom live on a reservation in the Puntarenas Province in southwestern Costa Rica, a few miles away from the Pan-American Highway where it follows the Rio Terraba. The ancestors of the modern Boruca made up a group of chiefdoms that ruled most of Costa Rica's Pacific coast, from Quepos to what is now the Panamanian border, including the Osa Peninsula. Boruca traditionally spoke the Boruca language, which is now nearly extinct. Like their ancestors the Boruca are known for their art and craftwork, especially weaving and their distinctive painted balsa wood masks, which have become popular decorative items among Costa Ricans and tourists. These masks are important elements in the Borucas' annual Danza de los Diablitos ceremony, celebrated every winter since at least early colonial times. The Danza depicts the resistance of the "Diablito", representing the Boruca people, against the Spanish conquistadors.

The Boruca are a tribe of Southern Pacific Costa Rica, close to the Panama border. The tribe is a composite group, made up of the group that identified as Boruca before the Spanish colonization, as well as many neighbors and former enemies, including the Coto people, Turrucaca, Borucac, Quepos, and the Abubaes.

About 2,660 people are in the Boruca tribe. They live in the Puntarenas area of Costa Rica on one of the first reservations that was established for indigenous Costa Ricans. They are popular for their crafts, particularly masks made for the "Fiesta de los Diablos" which is a three-day festival that stages fights between the Boruca Indians (depicted as devils) and the Spanish conquistadors (portrayed as Bulls).

- Bribri, southern Atlantic coast

The Bribri are an indigenous tribe that lives in Salitre, Cabagra, Talamanca Bribri and Kekoldi; Cabécar in Alto Chirripó, Tayni, Talamanca Cabécar, Telire and China Kichá, Bajo Chirripó, Nairi Awari and Ujarrás.[171] They are a voting majority in the Puerto Viejo de Talamanca area. The range of the population stretches from 11,000 to 35,000. The Bribri have a specific social structure that is organised in clans. Each clan is composed of an extended family. Women have a higher status in this society, because their children's clans are determined by whichever clan they come from. Women in the Bribri society are the only ones that can inherit land and prepare the sacred cacao drink used during the rituals. Men's roles are defined by their clan, and often are exclusive for men. The spiritual leader, or "awa" is very important to the Bribis, which men may have the opportunity to become. Just as it is important to many other indigenous groups in Costa Rica, Cacao holds a particular significance for the Bribi. They believe that the cacao tree used to be a woman and God turned it into a tree. Only women may prepare the drink, there are many associations that produce hand made chocolate which help these women.[172]

The Cabécar are an indigenous group of the remote Talamanca region of eastern Costa Rica. They speak Cabécar, a language belonging to the Chibchan language family of the Isthmo-Colombian Area of lower Central America and northwestern Colombia. According to census data from the National Institute of Statistics and Census of Costa Rica (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, INEC), the Cabécar are the largest indigenous group in Costa Rica with a population of nearly 17,000.[173]

Cabécar territory extends northwest from the Río Coen to the Río Reventazón.[174] Many Cabécar settlements today are located inside reserves established by Costa Rican law in 1976 to protect indigenous ancestral homelands.[175] These reserves exhibit ecological diversity, including vast swaths of tropical rainforest covering steep escarpments and large river valleys where many Cabécar still employ traditional subsistence livelihoods and cultural practices.

The Cabécar Indians is the largest Indigenous group in Costa Rica and is considered to be the most isolated. They have been pushed up to the Chirripo Mountains, which requires a few hours long hike to reach. Therefore, the Cabécar Indians have not been exposed to many basic items, and few of them have been exposed to education. They are very traditional and have preserved their culture. They speak the most of their own language rather than Spanish.

Christopher Columbus and his men contacted the Ngäbes in 1502, in what is now the Bocas del Toro province in northwestern Panama. He was eventually repelled by Ngäbe leader with either the name or title of Quibían. Since that contact, Spanish conquistadors, Latino cattle ranchers and large banana plantations successively forced the Ngäbes into the less desirable mountainous regions in the west. Many Ngäbe were never defeated, including the famous cacique Urracá who united nearby communities in a more than seven-year struggle against the Conquistadors. Those Ngäbe that remained on the outskirts of this region began to slowly blend with the Latinos and formed what are now termed campesinos, or rural Panamanians with indigenous roots.[176]

In the early 1970s[177] the Torrijos administration incentivized the Ngäbes to form denser communities by building roads, schools, clinics, and other infrastructure in designated points in what is now the Comarca Ngäbe-Buglé. This marked a social change in lifestyle, as formerly dispersed villages and family units converged and formed larger communities.

In 1997, after years of struggle with the Panamanian government, the Ngäbes were granted a Comarca, or semi-autonomous area, in which the majority now live.

The Quitirrisi are located in Ciudad Colon and Puriscal in the Central Valley. They are known for handwoven baskets and straw hats.

- Maleku, northern Alajuela

The Maleku are an indigenous group of about 600 people located in the San Rafael de Guatuso Indigenous Reserve. Before the Spanish colonization, their territory extended as far west as Rincon de la Vieja, and included the volcano Arenal to the south and Rio Celeste as sacred sites. Today their reserve is located about an hour north of La Fortuna. Although their land was much larger prior to colonization, they are now working on buying their own land back from the government. Their economy is based on indigenous art and many tourists are welcome to watch them perform musical pieces in nearby La Fortuna. This reservation is in great danger and the Maleku no longer live in their traditional houses as the trees are also endangered. They are working hard to protect their language, as there are only about 300 speakers of it.[178]

The Matambú, also known as the Chorotega are located in Guanacaste. The Chorotegas translating to "The Fleeing People" fled to Costa Rica in AD 500 to escape slavery from Southern Mexico, particularly being related to Maya people. Parts of their Mexican culture is evident in regards to their language and rituals, including human sacrifices. They are known as being the most powerful group of peoples during the conquest of the Spanish, as they were an organised military group and fought against the Spanish. There is evidence that they were a democracy and elected Caciques, or priests to be the leaders, and also that they were a hierarchical group. They are known for their agriculture, producing primarily corn and their ceramics/pottery today.[179]

- Ngäbe, southern Costa Rica, along the Panamá border