North Korea

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

40°00′N 127°00′E / 40.000°N 127.000°E

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

| |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

Anthem:

| |

Area controlled by the Democratic People's Republic of Korea shown in green | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Pyongyang |

| Official languages | Korean |

| Official scripts | Chosŏn'gŭl |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Juche single-party state (de jure) Single-party totalitarian military dictatorship under hereditary dictatorship[2] (de facto) |

| Kim Il-sung | |

| Kim Jong-il | |

| Kim Jong-un[a] | |

| Kim Yong-nam[b] | |

• Premier | Pak Pong-ju |

| Legislature | Supreme People's Assembly |

| Establishment | |

| Area | |

• Total | 120,540 km2 (46,540 sq mi) (98th) |

• Water (%) | 4.87 |

| Population | |

• 2013 estimate | 24,895,000 (48th) |

• 2011 census | 24,052,231[3] |

• Density | 198.3/km2 (513.6/sq mi) (63rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $40 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $1,800[4] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $12.4 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $506[5] |

| Gini (2007) | medium |

| HDI (2008) | high (156th) |

| Currency | North Korean won (₩) (KPW) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Korea Standard Time) |

| Date format | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +850 |

| ISO 3166 code | KP |

| Internet TLD | .kp |

| |

North Korea (ⓘ), officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK; Chosŏn'gŭl: 조선민주주의인민공화국; Chosŏn Minjujuŭi Inmin Konghwaguk), is a country in East Asia, in the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. The name Korea is derived from Goryeo, a dynasty which ruled in the Middle Ages. The capital and largest city is Pyongyang. North Korea shares a land border with China to the north and north-west, along the Amnok (Yalu) and Tumen rivers. A small section of the Tumen River also forms North Korea's short border with Russia to the northeast.[8] The Korean Demilitarized Zone marks the boundary between North Korea and South Korea. The legitimacy of this border is not accepted by either side, as both states claim to be the legitimate government of the entire peninsula.

The Korean Peninsula was governed by the Korean Empire from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, until it was annexed by the Empire of Japan in 1910. After the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II, Japanese rule ceased. The Korean Peninsula was divided into two occupied zones in 1945, with the northern part of the peninsula occupied by the Soviet Union and the southern portion by the United States. A United Nations-supervised election held in 1948 led to the creation of separate Korean governments for the two occupation zones: the Democratic People's Republic of Korea in the north, and the Republic of Korea in the south. The conflicting claims of sovereignty led to the Korean War in 1950. An armistice in 1953 committed both to a cease-fire, but the two countries remain officially at war because a formal peace treaty was never signed.[9] Both states were accepted into the United Nations in 1991.[10]

Although the DPRK officially describes itself as a Juche Korean-style socialist state[11] and elections are held, it is widely considered a dictatorship that has been described as totalitarian and Stalinist[20][2][21] with an elaborate cult of personality around the Kim family. The Workers' Party of Korea, led by a member of the ruling family,[21] holds de facto power in the state and leads the Democratic Front for the Reunification of the Fatherland of which all political officers are required to be a member.[22] Juche, an ideology of self-reliance initiated by the country's first President, Kim Il-sung, became the official state ideology, replacing Marxism–Leninism, when the country adopted a new constitution in 1972.[23][24] In 2009, references to Communism (Chosŏn'gŭl: 공산주의) were removed from the country's constitution.[25]

The means of production are owned by the state through state-run enterprises and collectivized farms, and most services such as healthcare, education, housing and food production are state funded or subsidized.[26] In the 1990s North Korea suffered from a famine and continues to struggle with food production. In 2013, the UN identified North Korean government policies as the primary cause of the shortages and estimated that 16 million people required food aid.[27][28]

North Korea follows Songun, or "military-first" policy in order to strengthen the country and its government.[29] It is the world's most militarized society, with a total of 9,495,000 active, reserve, and paramilitary personnel. Its active duty army of 1.21 million is the 4th largest in the world, after China, the U.S., and India.[30] It is a nuclear-weapons state and has an active space program.[31][32][33] As a result of its isolation, it is sometimes known as the "hermit kingdom".

History

Ancient kingdoms

According to legend, Gojoseon was the first Korean kingdom founded in the north of the peninsula, in 2333 BC by Dangun.[34] Gojoseon expanded until it controlled the northern Korean Peninsula and some parts of Manchuria. Gojoseon was first mentioned in Chinese records in the early 7th century BC, and around the 4th century BC, its capital moved to Pyongyang.

After many conflicts with the Chinese Han Dynasty, Gojoseon disintegrated. A number of small states emerged in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, leading to the Proto–Three Kingdoms of Korea period. This saw the kingdoms of Buyeo, Okjeo, Dongye, and the Samhan confederacy occupying the peninsula and southern Manchuria. Of the various states, Goguryeo in the north, and Baekje and Silla in the south, grew to control the peninsula as the Three Kingdoms of Korea. Goguryeo was the first Korean kingdom to adopt Buddhism as the state religion in 372.

The kingdom reached its zenith in the 5th century AD, when it controlled central Korea, including the present-day Seoul area. Goguryeo fought numerous wars with China and repulsed a number of Chinese invasions. However, the kingdom fell into decline in the 7th century and after internal power struggles, it was conquered by allied Silla-Tang forces. The unification of the Three Kingdoms by Silla in 676 led to the North South States Period, in which much of the Korean Peninsula was controlled by Silla. The kingdom of Balhae controlled northern areas of Korea and parts of Manchuria between the 7th and 10th centuries.

Under the rule of Unified Silla, relationships between Korea and China remained relatively peaceful. Silla weakened under internal strife, and eventually was defeated by King Taejo of Goryeo of the Goryeo Dynasty in 935.

Goryeo, with its capital at Gaegyeong in present day North Korea, gradually came to rule the whole Korean peninsula. The Mongol invasions in the 13th century greatly weakened Goryeo. Goryeo became a dependency of the Mongol Empire and was forced to pay tribute. After the Mongol Empire collapsed, Korea experienced political strife and the Goryeo Dynasty was replaced in 1388 by the long-lasting Joseon Dynasty (named in honor of the ancient Gojoseon kingdom).

Middle Ages

The capital was moved south to Hanyang (modern-day Seoul) in 1394. Joseon accepted the nominal suzerainty of China. Internal conflicts within the royal court and civil unrest plagued the kingdom in the years that followed, a situation made worse by the depredations of Japanese pirates.

After a largely peaceful 15th century, central authority declined and Korea was plagued again by coastal raids by Japanese pirates. Two Japanese attempts to conquer Korea were repulsed in 1592–1598. In the early 17th century Korea became involved in wars against the rising Manchus on the northern borders.

The 17th to 19th centuries were marked by increasing Joseon self-isolation from the outside world, dependence on China for external affairs and occasional internal faction fighting. The Joseon Dynasty tried to isolate from sea traders by closing itself to all nations except China. Slaves, nobi, are estimated to have accounted for about one third of the population of Joseon Korea.[35] By the mid-19th century the Joseon court followed a cautious policy of slow exchange with the West. In 1866, an American-owned armed merchant ship, attempted to open Korea to trade. The ship sailed upriver and became stranded near Pyongyang.

After being ordered to leave by Korean officials, American crewmen killed four Korean inhabitants, kidnapped a military officer and engaged in sporadic fighting.[citation needed] The ship was finally set aflame by Korean fireships. In 1871, a US force killed 243 Korean troops on Ganghwa island. This incident is called the Sinmiyangyo in Korea. Five years later, Korea signed a trade treaty with Japan, and in 1882 signed a treaty with the United States, ending centuries of isolationism of the "Hermit Kingdom".

Japanese occupation (1895–1945)

As a result of the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki stipulated the end of traditional Joseon dependency on China. In 1897, Joseon was renamed the Korean Empire. Russian influence was strong until the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), after which Korea became a protectorate of Japan. Korea was then annexed by the Empire of Japan in 1910, leading to 35 years of military rule.

After the annexation, Japan tried to suppress Korean traditions and culture and ran the economy primarily for the Japanese benefit. Anti-Japanese, pro-liberation rallies took place nationwide on 1 March 1919 (the 1 March Movement). About 7,000 people were killed during the suppression of this movement. Continued anti-Japanese uprisings, such as the nationwide uprising of students in 1929, led to the strengthening of military rule in 1931. After the outbreaks of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and World War II Japan stepped up efforts to extinguish Korean culture.

The Korean language was banned and Koreans were forced to adopt Japanese names. Worship at Japanese Shinto shrines was made compulsory. The school curriculum was radically modified to eliminate teaching in the Korean language and history. Numerous Korean cultural artifacts were destroyed or taken to Japan. Resistance groups known as Dongnipgun (Liberation Army) operated along the Sino-Korean border, fighting guerrilla warfare against Japanese forces. Some of them took part in allied action in China and parts of South East Asia.

During World War II, Koreans at home were forced to support the Japanese war effort. Tens of thousands of men were conscripted into Japan's military. Around 200,000 girls and women, many from Korea, were forced to engage in sexual services, with the euphemism "comfort women".

Division of Korea (1945)

After the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II, Japanese rule was brought to an end. The Korean peninsula was divided into two occupied zones in 1945 along the 38th parallel, with the northern half of the peninsula occupied by the Soviet Union and the southern half by the United States, in accordance with a prior arrangement between the two world powers, where United Nations-supervised elections were intended to be held for the entire peninsula shortly after the war. The Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, which had operated in exile since 1919, was ignored, mainly because of the American perception that it was too communist-aligned.

In August 1945, the Soviet Army established a Soviet Civil Authority in the northern portion of the Korean Peninsula. The Provisional People's Committee for North Korea was set up in February 1946, headed by Kim Il-sung. He introduced sweeping land reforms and nationalized key industries. Talks on the future of Korea were held in Moscow and Seoul but without result. Initial hopes for a unified, independent Korea evaporated as the politics of the Cold War resulted in the establishment of two separate nations with diametrically opposed political, economic, and social systems.

There was sporadic unrest in the South. In September 1946, South Korean citizens had risen up against the Allied Military Government. In April 1948, an uprising of the Jeju islanders was violently crushed. The South declared its statehood in May 1948 and two months later the ardent anti-Communist Syngman Rhee became its ruler. The People's Republic of Korea was established in the North on 9 September 1948.

The Rhee regime consolidated itself through harsh persecution of all suspected opponents. It conducted a number of military campaigns against left-wing insurgents during which 30,000 to 100,000 people lost their lives. In October 1948, the Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion occurred and on 24 December 1949, the South Korean Army massacred Mungyeong citizens who were suspected communist sympathizers and affixed the blame on communists.

Soviet forces withdrew from the North in 1948 and most American forces withdrew from the South the following year. This dramatically weakened the Southern regime and encouraged Kim Il-sung to consider an invasion plan against the South.[36][36] War proposals were rejected several times by Joseph Stalin, but along with the development of Soviet nuclear weapons, Mao Zedong's victory in China, and the Chinese indication that it would send troops and other support to North Korea, Stalin approved the invasion which led to the start of the Korean War in June 1950.[37] The Korean War broke out when North Korean forces crossed the 38th parallel to invade the South.

Korean War (1950–1953)

After Korea was divided by the UN, the two Korean powers both tried to control the whole peninsula under their respective governments. This led to escalating border conflicts on the 38th parallel and attempts to negotiate elections for the whole of Korea.[38] These attempts ended when the military of North Korea invaded the South on 25 June 1950, leading to a full-scale war. With endorsement from the United Nations, countries allied with the United States intervened on behalf of South Korea.

After rapid advances in a South Korean counterattack, North-allied Chinese forces intervened on behalf of North Korea, shifting the balance of the war. Fighting ended on 27 July 1953, with an armistice that approximately restored the original boundaries between North and South Korea. More than one million civilians and soldiers were killed in the war.

Although some have referred to the conflict as a civil war, other important factors were involved.[39] The Korean War was also the first armed confrontation of the Cold War and set the standard for many later conflicts. It is often viewed as an example of the proxy war, where the two superpowers would fight in another country, forcing the people in that country to suffer most of the destruction and death involved in a war between such large nations. The superpowers avoided descending into an all-out war against one another, as well as the mutual use of nuclear weapons. It also expanded the Cold War, which to that point had mostly been concerned with Europe. A heavily guarded demilitarized zone on the 38th parallel still divides the peninsula, and an anti-Communist and anti-North Korea sentiment remains in South Korea.

Since the Armistice in 1953, relations between the North Korean government and South Korea, the European Union, Canada, the United States, and Japan have remained tense, and hostile incidents occur often.[40][page needed] North and South Korea signed the June 15th North-South Joint Declaration in 2000, in which they promised to seek peaceful reunification.[41] On 4 October 2007, the leaders of North and South Korea pledged to hold summit talks to officially declare the war over and reaffirmed the principle of mutual non-aggression.[42] On 13 March 2013, North Korea confirmed it ended the 1953 Armistice and declared North Korea "is not restrained by the North-South declaration on non-aggression."[43]

Late 20th century

The relative peace between the South and the North following the armistice was interrupted by border skirmishes, celebrity abductions, and assassination attempts. The North failed in several assassination attempts on South Korean leaders, most notably in 1968, 1974 and the Rangoon bombing in 1983; tunnels were frequently found under the DMZ and war nearly broke out over the Axe Murder Incident at Panmunjom in 1976.[44] In 1973, extremely secret, high-level contacts began to be conducted through the offices of the Red Cross, but ended after the Panmunjom incident with little progress having been made and the idea that the two Koreas would join international organizations separately.[45]

North Korea remained closely aligned to China and the Soviet Union until the mid-1960s. Recovery from the war was quick – by 1957 industrial production reached 1949 levels. The last Chinese troops withdrew from the country in October 1958.[46] In 1959, Relations with Japan had improved somewhat, and North Korea began allowing the repatriation of Japanese citizens in the country. The same year, North Korea revalued the North Korean Won, which held greater value than its South Korean counterpart. Until the 1960s, economic growth was higher than in South Korea, and North Korean GDP per capita was equal to that of its southern neighbor as late as 1976.[47] In the early 1970s China began normalizing its relations with the West, particularly the U.S., and reevaluating its relations with North Korea. The diplomatic problems culminated in 1976 with the death of Mao Zedong. In response, Kim Il Sung began severing ties with China and reemphasizing national and economic self-reliance enshrined in his Juche Idea, which promoted producing everything within the country. However, by the 1980s the economy had begun to stagnate, started its long decline in 1987, and almost completely collapsed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 when all aid was suddenly halted. The North began reestablishing trade relations with China shortly thereafter, but the Chinese could not afford to provide enough food aid to meet demand. Flooding in the mid-1990s exacerbated the economic crisis, severely damaging crops and infrastructure and led to widespread famine which the government proved incapable of curtailing. In 1996, the government capitulated to accepting UN food aid.

In 1992, as Kim Il Sung's health began deteriorating, Kim Jong Il slowly began taking over various state tasks and after Sung died of a heart attack in 1994, declared a three year period of national mourning before officially announcing his position as the new head of state. As the economy continued to face problems Kim Jong Il instituted a policy called Songun, or "military first" to sideline his father's Juche. There is much speculation about this policy being used as a strategy to strengthen the military while discouraging coup attempts. Restrictions on travel were tightened and the state security apparatus was strengthened. In the late 1990s, North Korea began making attempts at normalizing relations with the West and negotiating disarmament deals with U.S. officials in exchange for food and economic aid.

In the late 1990s, with the South having transitioned to liberal democracy, the success of the Nordpolitik policy, and power in the North having been taken up by Kim Il-sung's son Kim Jong-il, the two nations began to engage publicly for the first time, with the South declaring its Sunshine Policy.[48][49]

Early 21st century

By the beginning of the 21st century, the worst of the devastating famine had passed, but North Korea continues to rely heavily on foreign aid for its food supply. In January 2002, U.S. president George W. Bush labeled North Korea part of an "axis of evil" and an "outpost of tyranny". The highest-level contact the government has had with the United States was with U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who made a visit to Pyongyang in 2000,[50] but the two countries do not have formal diplomatic relations.[51] By 2006, approximately 37,000 American soldiers remained in South Korea, although by June 2009 this number had fallen to around 30,000.[52][53] Kim Jong-il privately stated his acceptance of U.S. troops on the peninsula, even after a possible reunification.[54] Publicly, North Korea strongly demands the removal of American troops from South Korea.[54]

On 13 June 2009, the Associated Press reported that in response to new U.N. sanctions, North Korea declared it would progress with its uranium enrichment program. This marked the first time the DPRK has publicly acknowledged that it is conducting a uranium enrichment program.[55] In August 2009, former U.S. president Bill Clinton met with Kim Jong-il to secure the release of two American journalists, who had been sentenced for entering the country illegally.[56] Current U.S. President Barack Obama's position towards North Korea has been to resist making deals with North Korea for the sake of defusing tension, a policy known as "strategic patience."[57]

On 23 November 2010, North Korea fired about 170 rounds of artillery on Yeonpyeong Island and the surrounding waters near the Yellow Sea border, with some 90 shells landing on the island. The attack resulted in the deaths of two marines and two civilians on the South Korean side, and fifteen marines and at least three civilians wounded.[58] South Korean forces fired back 80 shells, although the results remain unclear. North Korean news sources alleged that the North Korean actions, described as "a prompt and powerful physical strike", were in response to provocation from South Korea that had held an artillery exercise in the disputed waters south of the island.[59]

On 17 December 2011, the Supreme Leader of North Korea, Kim Jong-il died from a heart attack.[60] His death was reported by the Korean Central News Agency around 08:30 local time with the newscaster announcing his youngest son Kim Jong-un as his successor.

The announcement placed South Korean and United States troops on high alert, with many politicians from the global community stating that Kim's death leaves a great deal of uncertainty in the country's future.[61] North Korea was put into a state of semi-alert, with foreigners put under suspicion and asked to leave.[62]

Pre-emptive nuclear strike threats of 2013

On 7 March 2013, North Korea announced its intentions to launch a preemptive nuclear strike against the United States.[63] The statement called the United States, the "sworn enemy of the Korean people".[64]

On 8 March 2013, the North Korean government announced that it was withdrawing from all non-aggression pacts with South Korea in response to U.N. Resolution 2094.[65][66][67] The announcement said it was closing its joint border crossing with South Korea and cutting off the hotline to the South.[65][66][67]

On 13 March 2013, North Korea confirmed it ended the 1953 Armistice and declared North Korea "is not restrained by the North-South declaration on non-aggression.[43] Confirmation of the severing of the hotline between the North and the South—the last remaining communication link between the two countries at that time—was publicly announced on March 27, 2013, the same date that the hotline was cut off. According to the Korean Central News Agency, a senior North Korean military official stated: "Under the situation where a war may break out any moment, there is no need to keep up North-South military communications" prior to the cessation of the communication channel.[68][69]

On 30 March 2013, the North Korean government declared it was in 'a state of war' with South Korea. A North Korean statement promised "stern physical actions" against "any provocative act". The North Korean leader Kim Jong-un declared that rockets were ready to be fired at American bases in the Pacific in response to the U.S. flying two nuclear-capable B2 stealth bombers over the Korean peninsula. The United States warned North Korea that the rapidly escalating military confrontation would lead to further isolation, as The Pentagon declared that the U.S. was "fully capable" of defending itself and its allies against a missile attack.[70][71][72] On 4 April 2013 North Korea's state news agency KCNA announced "The moment of explosion is approaching fast. No one can say a war will break out in Korea or not and whether it will break out today or tomorrow."[73]

U.S. National Intelligence Director James Clapper speculated that Kim Jong-un is trying to assert his control over North Korea, and has no endgame other than gaining recognition;[74] analysts and other U.S. officials have echoed similar sentiments.[75][76][77]

Four missile launches were conducted on May 18 and 19, 2013—according to South Korea's defense ministry, three short-range guided missiles landed into the waters off the Korean peninsula on May 18, followed by a fourth on May 19. The missiles did not put any neighboring nations at risk and Pyongyang's actions were widely viewed as an exercise in fear creation to prompt other countries to consider security and aid concessions. The launches occurred during a period when relations were strained between the North and the South, as Pyongyang refused to participate in talks over the closed Kaesong plant.[78]

At the start of June 2013, the North Korean government offered to enter into talks that would represent the first dialogue of its kind in many years. The South Korean government immediately accepted the proposal.[79]

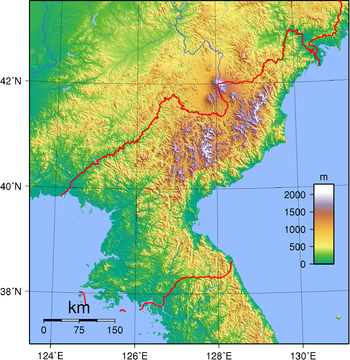

Geography

North Korea occupies the northern portion of the Korean Peninsula, lying between latitudes 37° and 43°N, and longitudes 124° and 131°E. It covers an area of 120,540 square kilometres (46,541 sq mi). North Korea shares land borders with China and Russia to the north, and borders South Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone.

To its west are the Yellow Sea and Korea Bay, and to its east lies Japan across the Sea of Japan (East Sea of Korea). The highest point in North Korea is Baekdu Mountain at 2,744 metres (9,003 ft). The longest river is the Amnok (Yalu) River which flows for 790 kilometres (491 mi).[80] The capital and largest city is Pyongyang; other major cities include Kaesong in the south, Sinuiju in the northwest, Wonsan and Hamhung in the east and Chongjin in the northeast.

In 2013, internet users were encouraged to participate in a community based event on Google Maps. These users could use Google Map Maker along with Cartography and Telemetry skills that eventually led to a virtual map of Pyongyang.[81] In addition, the Google Map of North Korea includes political prison camp locations such as Camp 22.[82]

Topography

Early European visitors to Korea remarked that the country resembled "a sea in a heavy gale" because of the many successive mountain ranges that crisscross the peninsula.[83] Some 80% of North Korea is composed of mountains and uplands, separated by deep and narrow valleys. All of the peninsula's mountains with elevations of 2,000 meters (6,600 ft) or more are located in North Korea. The coastal plains are wide in the west and discontinuous in the east. A great majority of the population lives in the plains and lowlands.

The highest point in North Korea is Baekdu Mountain which is a volcanic mountain which forms part of the Chinese/North Korean border with basalt lava plateau with elevations between 1,400 and 2,744 meters (4,593 and 9,003 ft) above sea level.[83] The Hamgyong Range, located in the extreme northeastern part of the peninsula, has many high peaks including Kwanmobong at approximately 2,541 m (8,337 ft).

Other major ranges include the Rangrim Mountains, which are located in the north-central part of North Korea and run in a north-south direction, making communication between the eastern and western parts of the country rather difficult; and the Kangnam Range, which runs along the North Korea–China border. Mount Kumgang, or Diamond Mountain, (approximately 1,638 metres or 5,374 feet) in the Taebaek Range, which extends into South Korea, is famous for its scenic beauty.[83]

For the most part, the plains are small. The most extensive are the Pyongyang and Chaeryong plains, each covering about 500 square kilometers (190 sq mi). Because the mountains on the east coast drop abruptly to the sea, the plains are even smaller there than on the west coast. Unlike neighboring Japan or northern China, North Korea experiences few severe earthquakes.

Climate

North Korea has a continental climate with four distinct seasons.[84] Long winters bring bitter cold and clear weather interspersed with snow storms as a result of northern and northwestern winds that blow from Siberia. Average snowfall is 37 days during the winter. The weather is likely to be particularly harsh in the northern, mountainous regions.

Summer tends to be short, hot, humid, and rainy because of the southern and southeastern monsoon winds that bring moist air from the Pacific Ocean. Typhoons affect the peninsula on an average of at least once every summer.[84] Spring and autumn are transitional seasons marked by mild temperatures and variable winds and bring the most pleasant weather. Natural hazards include late spring droughts which often are followed by severe flooding. There are occasional typhoons during the early fall.

North Korea's climate is relatively temperate. Most of the country is classified as type Dwa in the Köppen climate classification scheme, with warm summers and cold, dry winters. In summer there is a short rainy season called changma.[85] On 7 August 2007, the most devastating floods in 40 years caused the North Korean government to ask for international help. NGOs, such as the Red Cross, asked people to raise funds because they feared a humanitarian catastrophe.[86]

Administrative divisions

| Map | Namea | Chosŏn'gŭl | Administrative Seat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital city (chikhalsi)a | |||||

| 1 | Pyongyang | 평양직할시 | (Chung-guyok) | ||

| Special city (teukbyeolsi)a | |||||

| 2 | Rason | 라선특별시 | (Rajin-guyok) | ||

| Provinces (do)a | |||||

| 3 | South Pyongan | 평안남도 | Pyongsong | ||

| 4 | North Pyongan | 평안북도 | Sinuiju | ||

| 5 | Chagang | 자강도 | Kanggye | ||

| 6 | South Hwanghae | 황해남도 | Haeju | ||

| 7 | North Hwanghae | 황해북도 | Sariwon | ||

| 8 | Kangwon | 강원도 | Wonsan | ||

| 9 | South Hamgyong | 함경남도 | Hamhung | ||

| 10 | North Hamgyong | 함경북도 | Chongjin | ||

| 11 | Ryanggang * | 량강도 | Hyesan | ||

| * – Rendered in Southern dialects as "Yanggang" (양강도). | |||||

Government and politics

North Korea functions as a highly centralized, single-party republic. According to its 2009 constitution, it is a revolutionary Socialist state "guided in its activities by the Juche idea and the Songun idea".[87] The Korean Workers' Party has an estimated 3,000,000 members and dominates every aspect of North Korean politics. It has two satellite organizations, the Korean Social Democratic Party and the Chondoist Chongu Party[88] which participate in the KWP-led Democratic Front for the Reunification of the Fatherland. Another highly influential structure is the independent National Defence Commission (NDC). Kim Jong-un of the Kim family heads all major governing structures: he is First Secretary of the KWP, First Chairman of the NDC, and Supreme Commander of the Korean People's Army.[89][90] Kim Il-sung, who died in 1994, is the country's "Eternal President",[91] while Kim Jong-il was announced "Eternal General Secretary" after his death in 2011.[89]

The unicameral Supreme People's Assembly (SPA) is the highest organ of state authority and holds the legislative power. Its 687 members are elected every five years by universal suffrage. Supreme People's Assembly sessions are convened by the SPA Presidium, whose president (Kim Yong-nam since 1998) also represents the state in relations with foreign countries. Deputies formally elect the President, the vice-presidents and members of the Presidium and take part in the constitutionally appointed activities of the legislature: pass laws, establish domestic and foreign policies, appoint members of the cabinet, review and approve the state economic plan, among others.[92] However, the SPA itself cannot initiate any legislation independently of Party or state organs. It is unknown if it has ever criticized or amended bills placed before it, and the elections are based around a single list of KWP-approved candidates who stand without opposition.[93]

Executive power is vested in the Cabinet of North Korea, which is headed by Premier Pak Pong-ju.[94] The Premier represents the government and functions independently. His authority extends over two vice-premiers, 30 ministers, two cabinet commission chairmen, the cabinet chief secretary, the president of the Central Bank, the director of the Central Statistics Bureau and the president of the Academy of Sciences. A 31st ministry, the Ministry of the People's Armed Forces, is under the jurisdiction of the National Defence Commission.[95]

Political ideology

The Juche ideology is the cornerstone of party works and government operations. It is viewed by the official North Korean line as an embodiment of Kim Il-sung's wisdom, an expression of his leadership, and an idea which provides "a complete answer to any question that arises in the struggle for national liberation". Juche was pronounced in December 1955 in order to emphasize a Korea-centered revolution.[96] Its core tenets are economic self-sufficiency, military self-reliance and an independent foreign policy. The roots of Juche were made up of a complex mixture of domestic and foreign political factors, including the need to strengthen the cult of personality, the presence of pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese dissenters, and a centuries-old tradition of independence from foreign powers.[97]

It was initially promoted as a "creative application" of Marxism-Leninism, but in the mid-1970s it was described by state propaganda as "the only scientific thought...and most effective revolutionary theoretical structure that leads to the future of communist society". Juche eventually replaced Marxist-Leninism entirely by the 1980s,[98] and in 1992 references to the latter were omitted from the constitution.[99] The 2009 constitution rejected communism altogether.[100] Juche's concepts of self-reliance have thus evolved with time and circumstances, but still provide the groundwork for the spartan austerity, sacrifice and discipline demanded by the Party.[101]

Some foreign observers have instead described North Korea's political system as an absolute monarchy[102][103][104] or a "hereditary dictatorship".[105] Others view its ideology as a racialist-focused nationalism similar to that of Shōwa Japan,[106][107][108][109] or bearing a resemblance to European Fascism.[110] A defected North Korean scholar dismisses the idea that Juche is the country's leading ideology, regarding its public exaltation as designed to deceive foreigners.[111]

Law enforcement and internal security

North Korea has a civil law system based on the Prussian model and influenced by Japanese traditions and Communist legal theory.[112] Judiciary procedures are handled by the Central Court (the highest court of appeal), provincial or special city-level courts, people's courts and special courts. People's courts are at the lowest level of the system and operate in cities, counties and urban districts, while different kinds of special courts handle cases related to military, railroad or maritime matters. Judges are theoretically elected by their respective local people's assemblies, but in practice they're appointed by the Korean Workers' Party. The penal code is based on the principle of nullum crimen sine lege (no crime without a law), but remains a tool for political control despite several amendments reducing ideological influence.[113] Courts carry out legal procedures related not only to criminal and civil matters, but to political cases as well.[114] Political prisoners are sent to labor camps, while criminal offenders are incarcerated in a separate system.[115]

The Ministry of People's Security (MPS) maintains most law enforcement activities. It is one of the most powerful state institutions in North Korea and oversees the national police force, investigates criminal cases and manages non-political correctional facilities.[116] It also handles other aspects of domestic security like civil registration, traffic control, fire departments and railroad security.[117] The State Security Department was separated from the MPS in 1973 to conduct domestic and foreign intelligence, counterintelligence and manage the political prison system. Political camps can be short-term reeducation zones or "total control zones" for lifetime detention.[118] Camp 14 in Kaechon,[119] Camp 15 in Yodok[120] and Camp 18 in Bukchang[121] are described in detailed testimonies.[122] The security apparatus is very extensive,[123] exerting strict control over residence, travel, employment, clothing, food and family life.[124] Security establishments tightly monitor cellular and digital communications. The MPS, State Security and the Police allegedly conduct real-time monitoring of text messages, online data transfer, monitor phone calls and automatically transcribe recorded conversations. They reportedly have the capacity to triangulate a subscriber's exact location, while military intelligence monitors phone and radio traffic as far as 140 kilometers south of the Demilitarized zone.[125] Mass surveillance is carried out through a system which includes 100,000 CCTV cameras, many of which are installed at the border with China.[126]

Foreign relations

Initially, North Korea only had diplomatic ties with other Communist countries. In the 1960s and 1970s it pursued an independent foreign policy, established relations with many developing countries, and joined the Non-Aligned Movement. In the late 1980s and the 1990s its foreign policy was thrown into turmoil with the collapse of the Soviet bloc. Suffering an economic crisis, it closed 30% of its embassies. At the same time, it sought to build relations with developed capitalist countries. As of 2012, it had diplomatic relations with 162 countries, as well as the European Union and the Palestinian Authority, and embassies in 42 countries.[127] North Korea continues to have strong ties with its socialist southeast Asian allies in Vietnam and Laos, as well as with Cambodia.[128] Most of the foreign embassies to North Korea are located in Beijing rather than in Pyongyang.[129] North Korea began installing a concrete and barbed wire fence on its border with China in 2007,[130] and the Korean Demilitarized Zone with South Korea is the most heavily fortified border in the world.[131]

As a result of the North Korean nuclear weapons program, the six-party talks were established to find a peaceful solution to the growing tension between the two Korean governments, the Russian Federation, the People's Republic of China, Japan, and the United States. North Korea was previously designated a state sponsor of terrorism[132] because of its alleged involvement in the 1983 Rangoon bombing and the 1987 bombing of a South Korean airliner.[133] On 11 October 2008, the United States removed North Korea from its list of states that sponsor terrorism after Pyongyang agreed to cooperate on issues related to its nuclear program.[134] The kidnapping of at least 13 Japanese citizens by North Korean agents in the 1970s and the 1980s was another major issue in the country's foreign policy.[135]

Inter-Korean relations are at the core of North Korean foreign policy and have seen numerous shifts in the last few decades. In 1972, the two Koreas agreed in principle to achieve reunification through peaceful means and without foreign interference.[136] Despite this, relations remained cool well until the early 1990s, with the exception of a brief period in the early 1980s when North Korea provided flood relief to its southern neighbor and the two countries organized a reunion of 92 separated families.[137] The Sunshine Policy instituted by South Korean president Kim Dae Jung in 1998 was a watershed in inter-Korean relations. It encouraged other countries to engage with the North, which allowed Pyongyang to normalize relations with a number of European Union states and contributed to the establishment of joint North-South economic projects. The culmination of the Sunshine Policy was the 2000 Inter-Korean Summit, when Kim Dae Jung visited Kim Jong-il in Pyongyang.[138] On 4 October 2007, South Korean President Roh Moo-Hyun and Kim Jong-il signed an 8-point peace agreement.[42]

Relations worsened yet again in the late 2000s and early 2010s when South Korean president Lee Myung-bak adopted a more hard-line approach and suspended aid deliveries until the de-nuclearization of the North. North Korea responded by ending all of its previous agreements with the South.[139] It also deployed additional ballistic missiles[140] and placed its military on full combat alert after South Korea, Japan and the United States threatened to intercept a Unha-2 space launch vehicle.[141] The next few years witnessed a string of hostilities, including the alleged North Korean involvement in the sinking of South Korean warship Cheonan,[142] mutual ending of diplomatic ties,[143] a North Korean artillery attack on Yeonpyeong Island,[144] and an international crisis involving threats of a nuclear exchange.[145]

Military

The Korean People's Army (KPA) is the name of North Korea's military organization. The KPA has 1,106,000 active and 8,389,000 reserve and paramilitary troops, which makes it the largest military institution in the world.[146] About 20% of men aged 17–54 serve in the regular armed forces,[30] and approximately one in every 25 citizens is an enlisted soldier.[31][147] The KPA has five branches: Ground Force, Naval Force, Air Force, Special Operations Force, and Rocket Force. Command of the Korean People's Army lies both in the Central Military Commission of the Korean Workers' Party and the independent National Defense Commission. The Ministry of the People's Armed Forces is subordinated to the latter.[148]

Of all KPA branches, the Ground Force is the largest. It has approximately 1 million personnel divided into 80 infantry divisions, 30 artillery brigades, 25 special warfare brigades, 20 mechanized brigades, 10 tank brigades and seven tank regiments.[149] They are equipped with 3,700 tanks, 2,100 APCs and IFVs,[150] 17,900 artillery pieces, 11,000 anti-aircraft guns[151] and some 10,000 MANPADS and anti-tank guided missiles.[152] Other equipment includes 1,600 aircraft in the Air Force and 1,000 vessels in the Navy.[153] North Korea has the largest special forces and the largest submarine fleet in the world.[154]

North Korea is a nuclear weapons state but its arsenal remains limited. Various estimates put its stockpile at less than 10 plutonium warheads[155][156] and 12-27 nuclear weapon equivalents if uranium warheads are considered.[157] Delivery capabilities[158] are provided by the Rocket Force, which has some 1,000 ballistic missiles with a range of up to 3,000 kilometres.[159] These are supplemented by a vast stockpile of chemical weapons amounting to 2,500-5,000 tons, and possibly a biological weapons capability.[160][161] Because of its nuclear and missile tests, North Korea has been sanctioned under United Nations Security Council resolutions 1695 of July 2006, 1718 of October 2006, 1874 of June 2009, and 2087 of January 2013.

Military strategy is designed for insertion of agents and sabotage behind enemy lines in wartime.[30] However, the military faces some issues limiting its conventional capabilities, including obsolete equipment, insufficient fuel supplies and a shortage of digital command and control assets. To compensate for these deficiencies, the KPA has deployed a wide range of asymmetric warfare technologies like anti-personnel blinding lasers,[162] GPS jammers,[163] midget submarines and human torpedoes,[164] stealth paint,[165] electromagnetic pulse bombs,[166] and cyberwarfare units.[167] KPA units have also attempted to jam South Korean military satellites.[168]

Much of the equipment is engineered and produced by a domestic defense industry. Weapons are manufactured in roughly 1,800 underground defense industry plants scattered throughout the country, most of them located in Chagang Province.[169] The defense industry is capable of producing a full range of individual and crew-served weapons, artillery, armoured vehicles, tanks, missiles, helicopters, surface combatants, submarines, landing and infiltration craft, Yak-18 trainers and possibly jet aircraft.[123] According to official North Korean media, military expenditures for 2010 amount to 15.8% of the state budget.[170]

Society

Ascribed status

According to North Korean documents and refugee testimonies,[171] all North Koreans are sorted into groups according to their Songbun, an ascribed status system. Based on their own behavior and the political, social, and economic background of their family for three generations as well as behavior by relatives within that range, Songbun is allegedly used to determine whether an individual is trusted with responsibility, given opportunities,[172] or even receives adequate food.[171][173]

Songbun allegedly affects access to educational and employment opportunities and particularly whether a person is eligible to join North Korea's ruling party.[172] There are 3 main classifications and about 50 sub-classifications. According to Kim Il-sung, speaking in 1958, the loyal "core class" constituted 25% of the North Korean population, the "wavering class" 55%, and the "hostile class" 20%.[171] The highest status is accorded to individuals descended from those who participated with Kim Il-sung in the resistance against Japanese occupation during and before World War II and to those who were factory workers, laborers or peasants in 1950.[174]

While some analysts believe private commerce recently changed the Songbun system to some extent,[175] most North Korean refugees say it remains a commanding presence in everyday life.[171] However the North Korean government claims all citizens are equal and denies any discrimination on the basis of family background.[176]

Human rights

North Korea is widely accused of having one of the worst human rights records in the world.[177] North Koreans have been referred to as "some of the world's most brutalized people" by Human Rights Watch, because of the severe restrictions placed on their political and economic freedoms.[178][179] The North Korean population is strictly managed by the state and all aspects of daily life are subordinated to party and state planning. Employment is managed by the party on the basis of political reliability, and travel is tightly controlled by the Ministry of People's Security.[180] Amnesty International also reports of severe restrictions on the freedom of association, expression and movement, arbitrary detention, torture and other ill-treatment resulting in death, and executions.[181] North Korea also applies capital punishment, including public executions. Human rights organizations estimate that 1,193 executions had been carried out in the country by 2009.[182]

The State Security Department extrajudicially apprehends and imprisons those accused of political crimes without due process.[183] People perceived as hostile to the government, such as Christians or critics of the leadership,[184] are deported to labor camps without trial,[185] often with their whole family and mostly without any chance of being released.[186] Based on satellite images and defector testimonies, Amnesty International estimates that around 200,000 prisoners are held in six large political prison camps,[184][187] where they are forced to work in conditions approaching slavery.[188] Supporters of the government who deviate from the government line are subject to reeducation in sections of labor camps set aside for that purpose. Those who are successfully rehabilitated may reassume responsible government positions on their release.[189]

North Korean defectors[190] have provided detailed testimonies on the existence of the total control zones where abuses such as torture, starvation, rape, murder, medical experimentation, forced labor, and forced abortions have been reported.[122] On the basis of these abuses, as well as persecution on political, religious, racial and gender grounds, forcible transfer of populations, enforced disappearance of persons and forced starvation, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry has accused North Korea of crimes against humanity.[191][192][193] The International Coalition to Stop Crimes Against Humanity in North Korea (ICNK) estimates that over 10,000 people die in North Korean prison camps every year.[194]

The North Korean government rejects the human rights abuses claims, calling them "a smear campaign" and a "human rights racket" aimed at regime change.[195][196][197]

Personality cult

The North Korean government exercises control over many aspects of the nation's culture, and this control is used to perpetuate a cult of personality surrounding Kim Il-sung,[198] and, to a lesser extent, Kim Jong-il.[199] While visiting North Korea in 1979, journalist Bradley Martin noted that nearly all music, art, and sculpture that he observed glorified "Great Leader" Kim Il-sung, whose personality cult was then being extended to his son, "Dear Leader" Kim Jong-il.[200] Bradley Martin also reported that there is even widespread belief that Kim Il-sung "created the world", and Kim Jong-il could "control the weather".[200]

Such reports are contested by North Korea researcher Brian R. Myers: "divine powers have never been attributed to either of the two Kims. In fact, the propaganda apparatus in Pyongyang has generally been careful not to make claims that run directly counter to citizens’ experience or common sense."[201] He further explains that the state propaganda painted Kim Jong-il as someone whose expertise lay in military matters and that the famine of the 1990s was partially caused by natural disasters out of Kim Jong-il's control.[202]

The song "No Motherland Without You" (당신이없으면 조국도없다), sung by the North Korean Army Choir, was created especially for Kim Jong-il and is one of the most popular tunes in the country. Kim Il-sung is still officially revered as the nation's "Eternal President". Several landmarks in North Korea are named for Kim Il-sung, including Kim Il-sung University, Kim Il-sung Stadium, and Kim Il-sung Square. Defectors have been quoted as saying that North Korean schools deify both father and son.[203] Kim Il-sung rejected the notion that he had created a cult around himself, and accused those who suggested this of "factionalism".[200] Following the death of Kim Il-Sung, North Koreans were prostrating and weeping to a bronze statue of him in an organized event;[204] similar scenes were broadcast by state television following the death of Kim Jong-il.

Critics maintain this Kim Jong-il personality cult was inherited from his father, Kim Il-sung. Kim Jong-il was often the center of attention throughout ordinary life in the DPRK. His birthday is one of the most important public holidays in the country. On his 60th birthday (based on his official date of birth), mass celebrations occurred throughout the country.[205] Kim Jong-il's personality cult, although significant, was not as extensive as his father's. One point of view is that Kim Jong-il's cult of personality was solely out of respect for Kim Il-sung or out of fear of punishment for failure to pay homage.[206] Media and government sources from outside of North Korea generally support this view,[207][208][209][210][211] while North Korean government sources say that it is genuine hero worship.[212]

B. R. Myers also argues that the worship is real and not unlike worship of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany.[213] In a more recent event – on 11 June 2012 – a 14-year-old North Korean schoolgirl drowned while attempting to rescue portraits of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il from a flood.[214]

Korean reunification

North Korea's policy is to seek reunification without what it sees as outside interference, through a federal structure retaining each side's leadership and systems. In 2000, both North and South Korea signed the June 15th North–South Joint Declaration in which both sides made promises to seek out a peaceful reunification.[41] The Democratic Federal Republic of Korea is a proposed state first mentioned by then North Korean president Kim Il-sung on 10 October 1980, proposing a federation between North and South Korea in which the respective political systems would initially remain.[215]

Economy

North Korea has been maintaining one of the most closed and centralized economies in the world since the 1940s.[216] For several decades it followed the Soviet pattern of five-year plans with the ultimate goal of achieving self-sufficiency. Extensive Soviet and Chinese support allowed North Korea to rapidly recover from the Korean War and register very high growth rates. Systematic inefficiency began to arise around 1960, when the economy shifted from the extensive to the intensive development stage. The shortage of skilled labor, energy, arable land and transportation significantly impeded long-term growth and resulted in consistent failure to meet planning objectives.[217] The major slowdown of the economy contrasted with South Korea, which surpassed the North in terms of absolute Gross Domestic Product and per capita income by the 1980s.[218] North Korea declared the last seven-year plan unsuccessful in December 1993 and thereafter abandoned planning.[219] The loss of Eastern Bloc trading partners and a series of natural disasters throughout the 1990s caused severe hardships, including widespread famine. By 2000, the situation improved owing to a massive international food assistance effort, but the economy continues to suffer from food shortages, dilapidated infrastructure and a critically low energy supply.[220]

In an attempt to recover from the collapse, the government began structural reforms in 1998 that formally legalized private ownership of assets and decentralized control over production.[221] A second round of reforms in 2002 led to an expansion of market activities, partial monetization, flexible prices and salaries, and the introduction of incentives and accountability techniques.[222] Despite these changes, North Korea remains a command economy where the state owns almost all means of production and development priorities are defined by the government.[220] It has the structural profile of a relatively industrialized country[223] where nearly half of the Gross Domestic Product is generated by industry[224] and human development is at medium levels.[7] Purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP is estimated at $40 billion,[225] with a very low per capita value of $1,800.[226] Gross national income per capita was $1,523 in 2012, compared to $28,430 in South Korea.[227] The North Korean won is the national currency issued by the Central Bank of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea.

The economy is heavily socialized.[228] Food and housing are extensively subsidized by the state, education and healthcare are free,[229] and the payment of taxes was abolished in 1974.[230] The average North Korean family draws the vast majority of its income from small private enterprises.[231] A variety of goods are available in department stores and supermarkets in Pyongyang,[232] though most of the population relies on small-scale janmadang markets.[233][234] In 2009, the government attempted to stem the expanding free market by banning janmadang and the use of foreign currency,[220] but the resulting inflation spike and rare public protests caused a reversal of these policies.[235] Private trade is dominated by women because most men are required to be present at their workplace, even though many state-owned enterprises are non-operational.[236]

Industry and services employ 65%[237] of North Korea's 12.6 million labor force.[238] Major industries include machine building, military equipment, chemicals, mining, metallurgy, textiles, food processing and tourism.[239] Iron ore and coal production are among the few sectors where North Korea performs significantly better than its southern neighbor – it produces about 10 times larger amounts of each resource.[240] The agricultural sector was shattered by the natural disasters of the 1990s.[241] Its 3,500 cooperatives and state farms[242] were among the most productive and successful in the world around 1980[243] but now experience chronic fertilizer and equipment shortages. Rice, corn, soybeans and potatoes are some of the primary crops and a significant contribution to the food supply comes from commercial fishing and aquaculture.[220] Tourism has been a growing sector for the past decade.[244] North Korea aims to increase the number of foreign visitors from 200,000 to one million by 2016 through projects like the Masikryong Ski Resort.[245]

Foreign trade surpassed pre-crisis levels in 2005 and continues to expand.[246] North Korea has a number of special economic zones (SEZs) and Special Administrative Regions where foreign companies can operate with tax and tariff incentives while North Korean establishments gain access to improved technology.[247] Initially four such zones existed, but they yielded little overall success.[248] The SEZ system was overhauled in 2013 when 14 new zones were opened and the Rason Special Economic Zone was reformed as a joint Chinese-North Korean project.[249] The Kaesong Industrial Region is a special economic zone where more than 100 South Korean companies employ some 52,000 North Korean workers.[250] Outside inter-Korean trade, more than 89% of external trade is conducted with China. Russia is the second-largest foreign partner with $100 million worth of imports and exports for the same year.[251] In 2014, Russia wrote off 90% of North Korea's debt and the two countries agreed to conduct all transactions in rubles.[252][253] Overall, external trade in 2013 reached a total of $7.3 billion - the highest amount since 1990[251] - while inter-Korean trade dropped to an eight-year low of $1.1 billion.[254]

Infrastructure

The crumbling energy infrastructure creates chronic economic problems. Most power generation facilities have either been abandoned or need repairs. Electricity shortages would not be alleviated even by imports because the obsolete power grid is poorly maintained and causes significant losses during transmission.[255] Coal accounts for 70% of primary energy production, followed by hydroelectric power with 17%.[256] The government under Kim Jong-un has increased emphasis on renewable energy projects like wind farms, solar parks, solar heating and biomass.[257] A set of legal regulations adopted in 2014 stressed the development of geothermal, wind and solar energy along with recycling and environmental conservation.[257][258] North Korea also strives to develop its own civilian nuclear program, but these efforts are under much international dispute due to their military applications and concerns about safety.[259] Russian energy company Gazprom has a project for a $2.5 billion gas pipeline to South Korea through Pyongyang, which is expected to generate an annual revenue of $100 million from transit fees.[260][261]

Transport infrastructure includes railways, highways, water and air routes, but rail transport is by far the most widespread. North Korea has some 5,200 kilometres of railways mostly in standard gauge which carry 80% of annual passenger traffic and 86% of freight, but electricity shortages undermine their efficiency.[256] Construction of a high-speed railway connecting Kaesong, Pyongyang and Sinuiju with speeds exceeding 200 km/h was approved in 2013.[262] North Korea connects with the Trans-Siberian Railway through Rajin.[263] By contrast, road transport is very limited - only 724 of the 25,554-kilometer road network are paved,[264] and maintenance on most roads is poor.[265] Only 2% of the freight capacity is supported by river and sea transport, and air traffic is negligible.[256] All port facilities are ice-free and host a merchant fleet of 158 vessels.[266] Eighty-two airports[267] and 23 helipads[268] are operational and the largest serve the state-run airline, Air Koryo.[256] Cars are relatively rare, but some 70% of households used bicycles in 2008.[269]

Science and technology

R&D efforts are concentrated at the State Academy of Sciences, which runs 40 research institutes, 200 smaller research centers, a scientific equipment factory and six publishing houses.[270] The government considers science and technology as directly linked to economic development.[271][272] A five-year scientific plan emphasizing IT, biotechnology, nanotechnology, marine and plasma research was carried out in the early 2000s.[271] A 2010 report by the South Korean Science and Technology Policy Institute identified polymer chemistry, animal cloning, single carbon materials, nanoscience, mathematics, software, nuclear technology and rocketry as potential areas of inter-Korean scientific cooperation. North Korean institutes are strong in these fields of research, although their engineers require additional training and laboratories need equipment upgrades.[273]

Under its "constructing a powerful knowledge economy" slogan, the state has launched a project to concentrate education, scientific research and production into a number of "high-tech development zones". However, international sanctions remain a significant obstacle to their development.[274] The Miraewon network of electronic libraries was established in 2014 under similar slogans.[275]

Significant resources have been allocated to the national space program, which is managed by the Korean Committee of Space Technology.[276] Domestically produced launch vehicles and the Kwangmyŏngsŏng satellite class are launched from two spaceports, the Tonghae Satellite Launching Ground and the Sohae Satellite Launching Station. After four failed attempts, North Korea became the tenth spacefaring nation with the launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2 in December 2012.[277] It joined the Outer Space Treaty in 2009[278] and has stated its intentions to undertake manned and Moon missions.[276] The government insists the space program is for peaceful purposes, but the United States, Japan, South Korea and other countries maintain that it serves to advance military ballistic missile programs.[279]

Usage of communication technology is controlled by the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications. An adequate nationwide fiber-optic telephone system with 1.18 million fixed lines[280] and expanding mobile coverage is in place.[281] Most phones are installed for senior government officials and installation requires written explanation why the user needs a telephone and how it will be paid for.[282] Cellular coverage is available with a 3G network operated by Koryolink, a joint venture with Orascom Telecom Holding.[283] The number of subscribers has increased from 3,000 in 2002[284] to almost two million in 2013.[283] International calls through either fixed or cellular service are restricted, and mobile Internet is not available.[283] Internet access itself is limited to a handful of elite users and scientists. Instead, North Korea has a walled garden intranet system called Kwangmyong,[285] which is maintained and monitored by the Korea Computer Center.[286] Its content is limited to state media, chat services, message boards,[285] an e-mail service and an estimated 1,000-5,500 websites.[287] Computers employ the Red Star OS, an operating system heavily based on Linux, with visual styling similar to Apple's Mac OS X. North Korea's only Internet café is in Pyongyang.[287]

Demographics

North Korea's population of roughly 24 million is one of the most ethnically and linguistically homogeneous in the world, with very small numbers of Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, South Korean, and European expatriate minorities.

According to the CIA World Factbook, North Korea's life expectancy was 63.8 years in 2009, a figure roughly equivalent to that of Pakistan and Burma and slightly lower than Russia.[288] Infant mortality stood at a high level of 51.3, which is 2.5 times higher than that of China, 5 times that of Russia, and 12 times that of South Korea.[289]

According to the UNICEF "The State of the world's Children 2003" North Korea appears ranked at the 73rd place (with first place having the highest mortality rate), between Guatemala (72nd) and Tuvalu (74th).[289][290] North Korea's total fertility rate is relatively low and stood at 2.0 in 2009, comparable to those of the United States and France.[291]

Language

North Korea shares the Korean language with South Korea. There are dialect differences within both Koreas, but the border between North and South does not represent a major linguistic boundary. Both Koreas share the phonetic writing system called Chosongul in the north and Hangul south of the DMZ. The official Romanization differs in the two countries, with North Korea using a slightly modified McCune-Reischauer system, and the South using the Revised Romanization of Korean. While prevalent in the South, the adoption of modern terms from foreign languages has been limited in North Korea. Hanja (Chinese characters) are no longer used in North Korea (ever since 1949), although still occasionally used in South Korea. The move toward prohibiting both Roman and Chinese-based characters in North Korea has led to the creation of a number of words and phrases not common in the southern half of the peninsula or in Korean communities abroad.

Religion

Both Koreas share a Buddhist and Confucian heritage and a recent history of Christian and Cheondoism ("religion of the Heavenly Way") movements. The North Korean constitution states that freedom of religion is permitted.[293] According to the Western standards of religion, the majority of the North Korean population could be characterized as non-religious.[citation needed] However, the cultural influence of such traditional religions as Buddhism and Confucianism still have an effect on North Korean spiritual life.[294][295][296]

Nevertheless, Buddhists in North Korea reportedly fare better than other religious groups, particularly Christians, who are said to face persecution by the authorities. Buddhists are given limited funding by the government to promote the religion, because Buddhism played an integral role in traditional Korean culture.[297]

According to Human Rights Watch, free religious activities no longer exist in North Korea, as the government sponsors religious groups only to create an illusion of religious freedom.[298] According to Religious Intelligence the situation of religion in North Korea is the following:[299]

- Irreligion: 15,460,000 (64.3% of population, the vast majority of which are adherents of the Juche philosophy)

- Korean shamanism: 3,846,000 adherents (16% of population)

- Cheondoism: 3,245,000 adherents (13.5% of population)

- Buddhism: 1,082,000 adherents (4.5% of population)

- Christianity: 406,000 adherents (1.7% of population)

Pyongyang was the center of Christian activity in Korea until 1945. From the late forties 166 priests and other religious figures were killed or disappeared in concentration camps, including Francis Hong Yong-ho, bishop of Pyongyang[300] and all monks of Tokwon abbey.[301] No Catholic priest survived the persecution, all churches were destroyed and the government never allowed any foreign priest to set up in North Korea.[302]

Today, four state-sanctioned churches exist, which freedom of religion advocates say are showcases for foreigners.[303][304] Official government statistics report that there are 10,000 Protestants and 4,000 Roman Catholics in North Korea.[305]

According to a ranking published by Open Doors, an organization that supports persecuted Christians, North Korea is currently the country with the most severe persecution of Christians in the world.[306] Open Doors estimates that 50,000–70,000 Christians are detained in North Korean prison camps.[307] Human rights groups such as Amnesty International also have expressed concerns about religious persecution in North Korea.[308]

Education

Education in North Korea is free of charge,[309] compulsory until the secondary level, and controlled by the government. The state also used to provide school uniforms free of charge until the early 1990s.[310] Heuristics is actively applied in order to develop the independence and creativity of students.[311] Compulsory education lasts eleven years, and encompasses one year of preschool, four years of primary education and six years of secondary education. The school curriculum has both academic and political content.[312] North Korea is one of the most literate countries in the world, with an average literacy rate of 99%.[51] According to Shin Dong-hyuk, children imprisoned in concentration camps also receive a form of education.[313] Studying of Russian and English language was made compulsory in upper middle schools in 1978.[314]

Primary schools are known as people's schools, and children attend them from the age of 6 to 9. Then, from age 10 to 16, they attend either a regular secondary school or a special secondary school, depending on their specialties.

Higher education

Higher education is not compulsory in North Korea. It is composed of two systems: academic higher education and higher education for continuing education. The academic higher education system includes three kinds of institutions: universities, professional schools, and technical schools. Graduate schools for master's and doctoral level studies are attached to universities, and are for students who want to continue their education. Two notable universities in the DPRK are the Kim Il-sung University and Pyongyang University of Science and Technology, both in Pyongyang. The former, founded in October 1946, is an elite institution whose enrollment of 16,000 full- and part-time students in the early 1990s occupies, in the words of one observer, the "pinnacle of the North Korean educational and social system."[315] There is also a University called the Kim Chaek University of Technology that specializes in information technology and nuclear research.[316]

Health care

North Korea has a national medical service and health insurance system which are offered for free.[26] In 2001 North Korea spent 3% of its gross domestic product on health care. Beginning in the 1950s, the DPRK put great emphasis on healthcare, and between 1955 and 1986, the number of hospitals grew from 285 to 2,401, and the number of clinics – from 1,020 to 5,644.[317] There are hospitals attached to factories and mines. Since 1979 more emphasis has been put on traditional Korean medicine, based on treatment with herbs and acupuncture. A national telemedicine network was launched in 2010. It connects the Kim Man Yu hospital in Pyongyang with 10 provincial medical facilities.[318]

North Korea's healthcare system has been in a steep decline since the 1990s because of natural disasters, economic problems, and food and energy shortages. In 2001, many hospitals and clinics in North Korea lack essential medicines, equipment, running water and electricity.[319]

Almost 100% of the population has access to water and sanitation, but it is not completely potable. Infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, malaria, and hepatitis B, are considered to be endemic to the country.[320] Life expectancy in North Korea is 63.81 years, occupying the 169th place in the world, according to 2011 estimates.[288]

The health care system has been a subject of controversy: the World Health Organization described it as "the envy of the developing world" while simultaneously acknowledging that "challenges remained, including poor infrastructure, a lack of equipment, malnutrition and a shortage of medicines." Amnesty International claims that it suffers from barely functioning hospitals, poor hygiene and epidemics. Regarding this controversy, the BBC's Imogen Foulkes says a number of UN agencies have aid projects in North Korea and are thought to be reluctant to openly criticise the country for fear of jeopardising their work there.[321]

Famine

In the 1990s North Korea faced significant economic disruptions, including a series of natural disasters, economic mismanagement and serious resource shortages after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. These resulted in a shortfall of staple grain output of more than 1 million tons from what the country needs to meet internationally accepted minimum dietary requirements.[322] The North Korean famine known as the "Arduous March" resulted in the deaths of between 300,000 and 800,000 North Koreans per year during the three-year famine, peaking in 1997.[323] The deaths were most likely caused by famine-related illnesses such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diarrhea rather than starvation.[323]

Beginning in 1997, the U.S. began shipping food aid to North Korea through the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) to combat the famine. Shipments peaked in 1999 at nearly 700,000 tons making the U.S. the largest foreign aid donor to the country at the time.[324] Under the Bush Administration, aid was drastically reduced year after year from 350,000 tons in 2001 to 40,000 in 2004.[325] Agricultural production had increased from about 2.7 million tons in 1997 to 4.2 million tons in 2004.[326]

In 2006, Amnesty International reported that a national nutrition survey conducted by the North Korean government, the World Food Programme, and UNICEF found that 7% of children were severely malnourished; 37% were chronically malnourished; 23.4% were underweight; and one in three mothers was malnourished and anemic as the result of the lingering effect of the famine. The inflation caused by some of the 2002 economic reforms, including the Songun or "Military-first" policy, was cited for creating the increased price of basic foods.[327] In 2013, there were reports of famine returning to parts of North Korea and driving some to cannibalism, with the claims that one man dug up his grandchild's corpse to eat and another boiled his child and ate the flesh.[328] Another man was allegedly executed after murdering his two children for food.[328] However, the World Food Program reported malnutrition and food shortages, but not famine.[329]

Culture and arts

North Korea shares its traditional culture with South Korea, but the two Koreas have developed distinct contemporary forms of culture since the peninsula was divided in 1945. Historically, while the culture of Korea has been influenced by that of neighbouring China, it has nevertheless managed to develop a unique and distinct cultural identity from its larger neighbour.[330]

Literature and arts in North Korea are state-controlled, mostly through the Propaganda and Agitation Department or the Culture and Arts Department of the Central Committee of the KWP.[331] Film is also a significant artistic medium in North Korea and Kim Jong Il's manifesto The Cinema and Directing (1987) is the basis for the nation's filmmakers.[332]

Korean culture came under attack during the Japanese rule from 1910 to 1945. Japan enforced a cultural assimilation policy. During the Japanese rule, Koreans were encouraged to learn and speak Japanese, adopt the Japanese family name system and Shinto religion, and were forbidden to write or speak the Korean language in schools, businesses, or public places.[333] In addition, the Japanese altered or destroyed various Korean monuments including Gyeongbok Palace and documents which portrayed the Japanese in a negative light were revised.

A popular event in North Korea is the Mass Games. The most recent and largest Mass Games was called "Arirang". It was performed six nights a week for two months, and involved over 100,000 performers. Attendees to this event in recent years report that the anti-West sentiments have been toned down compared to previous performances. The Mass Games involve performances of dance, gymnastics, and choreographic routines which celebrate the history of North Korea and the Workers' Party Revolution. The Mass Games are held in Pyongyang at various venues (varying according to the scale of the Games in a particular year) including the Rungnado May Day Stadium, which is the largest stadium in the world with a capacity of 150,000 people. In addition, a Kim Chaek People's Stadium was built for events at 40°41'0"N 129°11'47"E.

North Korea employs artists to produce art for export at the Mansudae Art Studio in Pyongyang. Over 1,000 artists are employed. Products include water colors, ink drawings, posters, mosaics and embroidery. Socialist realism is the approved style with North Korea being portrayed as prosperous and progressive and its citizens as happy and enthusiastic. Traditional Korean designs and themes are present most often in the embroidery. The artistic and technical quality of the works produced is very high but other than a few wealthy South Korean collectors there is a limited market because of public taste and reluctance of states and collectors to financially support the regime.[334]

In July 2004, the Complex of Goguryeo Tombs became the first site in the country to be included in the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites.

In February 2008, The New York Philharmonic Orchestra became the first US orchestra to perform in North Korea,[335] albeit for a handpicked "invited audience."[336] The concert was broadcast on national television.[337] The Christian rock band Casting Crowns played at the annual Spring Friendship Arts Festival in April 2007, held in Pyongyang.[338]

Australian filmmaker Anna Broinowski gained access to North Korea's film industry through British filmmaker Nick Bonner, who facilitated meetings between Broinowski and prominent North Korean filmmakers to assist Broinowski with the production of Aim High in Creation!, a film project based on Kim Jong Il's manifesto. Broinowski explained in July 2013, prior to the screening of the film at the Melbourne International Film Festival: