Paracetamol

Paracetamol,[a] or acetaminophen,[b] is a non-opioid analgesic and antipyretic agent used to treat fever and mild to moderate pain.[13][14][15] It is a widely available over-the-counter drug sold under various brand names, including Tylenol and Panadol.

Paracetamol relieves pain in both acute mild migraine and episodic tension headache.[16][17] At a standard dose, paracetamol slightly reduces fever;[14][18][19] it is inferior to ibuprofen in that respect,[20] and the benefits of its use for fever are unclear, particularly in the context of fever of viral origins.[14][21][22] The aspirin/paracetamol/caffeine combination also helps with both conditions where the pain is mild and is recommended as a first-line treatment for them.[23][24] Paracetamol is effective for post-surgical pain, but it is inferior to ibuprofen.[25] The paracetamol/ibuprofen combination provides further increase in potency and is superior to either drug alone.[25][26] The pain relief paracetamol provides in osteoarthritis is small and clinically insignificant.[15][27][28] The evidence in its favor for the use in low back pain, cancer pain, and neuropathic pain is insufficient.[15][27][29][30][31][32]

In the short term, paracetamol is safe and effective when used as directed.[33] Short term adverse effects are uncommon and similar to ibuprofen,[34] but paracetamol is typically safer than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for long-term use.[35] Paracetamol is also often used in patients who cannot tolerate NSAIDs like ibuprofen.[36][37] Chronic consumption of paracetamol may result in a drop in hemoglobin level, indicating possible gastrointestinal bleeding,[38] and abnormal liver function tests. The recommended maximum daily dose for an adult is three to four grams.[27][39] Higher doses may lead to toxicity, including liver failure.[40] Paracetamol poisoning is the foremost cause of acute liver failure in the Western world, and accounts for most drug overdoses in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.[41][42][43]

Paracetamol was first made in 1878 by Harmon Northrop Morse or possibly in 1852 by Charles Frédéric Gerhardt.[44][45][46] It is the most commonly used medication for pain and fever in both the United States and Europe.[47] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[48] Paracetamol is available as a generic medication, with brand names including Tylenol and Panadol among others.[49] In 2022, it was the 114th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 5 million prescriptions.[50][51]

Medical uses

[edit]Fever

[edit]Paracetamol is used for reducing fever.[13] However, there has been a lack of research on its antipyretic properties, particularly in adults, and thus its benefits are unclear.[14] As a result, it has been described as over-prescribed for this application.[14] In addition, low-quality clinical data indicates that when used for the common cold, paracetamol may relieve a stuffed or runny nose, but not other cold symptoms such as sore throat, malaise, sneezing, or cough.[52]

For people in critical care, paracetamol decreases body temperature by only 0.2–0.3 °C more than control interventions and has no effect on their mortality.[18] It did not change the outcome in febrile patients with stroke.[53] The results are contradictory for paracetamol use in sepsis: higher mortality, lower mortality, and no change in mortality were all reported.[18] Paracetamol offered no benefit in the treatment of dengue fever and was accompanied by a higher rate of liver enzyme elevation: a sign of potential liver damage.[54] Overall, there is no support for a routine administration of antipyretic drugs, including paracetamol, to hospitalized patients with fever and infection.[22]

The efficacy of paracetamol in children with fever is unclear.[55] Paracetamol should not be used solely to reduce body temperature; however, it may be considered for children with fever who appear distressed.[56] It does not prevent febrile seizures.[56][57] It appears that 0.2 °C decrease of the body temperature in children after a standard dose of paracetamol is of questionable value, particularly in emergencies.[14] Based on this, some physicians advocate using higher doses that may decrease the temperature by as much as 0.7 °C.[19] Meta-analyses showed that paracetamol is less effective than ibuprofen in children (marginally less effective, according to another analysis[58]), including children younger than 2 years old,[59] with equivalent safety.[20] Exacerbation of asthma occurs with similar frequency for both medications.[60] Giving paracetamol and ibuprofen together at the same time to children under 5 is not recommended; however, doses may be alternated if required.[56]

Pain

[edit]Paracetamol is used for the relief of mild to moderate pain such as headache, muscle aches, minor arthritis pain, toothache as well as pain caused by cold, flu, sprains, and dysmenorrhea.[61] It is recommended, in particular, for acute mild to moderate pain, since the evidence for the treatment of chronic pain is insufficient.[15]

Musculoskeletal pain

[edit]The benefits of paracetamol in musculoskeletal conditions, such as osteoarthritis and backache, are uncertain.[15]

It appears to provide only small and not clinically important benefits in osteoarthritis.[15][27] American College of Rheumatology and Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis notes that the effect size in clinical trials of paracetamol has been very small, which suggests that for most individuals it is ineffective.[28] The guideline conditionally recommends paracetamol for short-term and episodic use to those who do not tolerate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. For people taking it regularly, monitoring for liver toxicity is required.[28] Essentially the same recommendation was issued by EULAR for hand osteoarthritis.[62] Similarly, the ESCEO algorithm for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis recommends limiting the use of paracetamol to short-term rescue analgesia only.[63]

Paracetamol is ineffective for acute low back pain.[15][29] No randomized clinical trials evaluated its use for chronic or radicular back pain, and the evidence in favor of paracetamol is lacking.[30][27][29]

Headaches

[edit]Paracetamol is effective for acute migraine:[16] 39 % of people experience pain relief at one hour compared with 20 % in the control group.[64] The aspirin/paracetamol/caffeine combination also "has strong evidence of effectiveness and can be used as a first-line treatment for migraine".[23] Paracetamol on its own only slightly alleviates episodic tension headache in those who have them frequently.[17] However, the aspirin/paracetamol/caffeine combination is superior to both paracetamol alone and placebo and offers meaningful relief of tension headache: two hours after administering the medication, 29 % of those who took the combination were pain-free as compared with 21 % on paracetamol and 18 % on placebo.[65] The German, Austrian, and Swiss headache societies and the German Society of Neurology recommend this combination as a "highlighted" one for self-medication of tension headache, with paracetamol/caffeine combination being a "remedy of first choice", and paracetamol a "remedy of second choice".[24]

Dental and other post-surgical pain

[edit]Pain after a dental surgery provides a reliable model for the action of analgesics on other kinds of acute pain.[66] For the relief of such pain, paracetamol is inferior to ibuprofen.[25] Full therapeutic doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) ibuprofen, naproxen or diclofenac are clearly more efficacious than the paracetamol/codeine combination which is frequently prescribed for dental pain.[67] The combinations of paracetamol and NSAIDs ibuprofen or diclofenac are promising, possibly offering better pain control than either paracetamol or the NSAID alone.[25][26][68][69] Additionally, the paracetamol/ibuprofen combination may be superior to paracetamol/codeine and ibuprofen/codeine combinations.[26]

A meta-analysis of general post-surgical pain, which included dental and other surgery, showed the paracetamol/codeine combination to be more effective than paracetamol alone: it provided significant pain relief to as much as 53 % of the participants, while the placebo helped only 7 %.[70]

Other pain

[edit]Paracetamol fails to relieve procedural pain in newborn babies.[71][72] For perineal pain postpartum paracetamol appears to be less effective than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[73]

The studies to support or refute the use of paracetamol for cancer pain and neuropathic pain are lacking.[31][32] There is limited evidence in favor of the use of the intravenous form of paracetamol for acute pain control in the emergency department.[74] The combination of paracetamol with caffeine is superior to paracetamol alone for the treatment of acute pain.[75]

Patent ductus arteriosus

[edit]Paracetamol helps ductal closure in patent ductus arteriosus. It is as effective for this purpose as ibuprofen or indomethacin, but results in less frequent gastrointestinal bleeding than ibuprofen.[76] Its use for extremely low birth weight and gestational age infants however requires further study.[76]

Adverse effects

[edit]Gastrointestinal adverse effects such as nausea and abdominal pain are extremely uncommon, and their frequency is nothing like that of ibuprofen.[37] Increase in risk-taking behavior is possible.[77] According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the drug may cause rare and possibly fatal skin reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis,[78] Rechallenge tests and an analysis of American but not French pharmacovigilance databases indicated a risk of these reactions.[78][79]

In clinical trials for osteoarthritis, the number of participants reporting adverse effects was similar for those on paracetamol and on placebo. However, the abnormal liver function tests (meaning there was some inflammation or damage to the liver) were almost four times more likely in those on paracetamol, although the clinical importance of this effect is uncertain.[80] After 13 weeks of paracetamol therapy for knee pain, a drop in hemoglobin level indicating gastrointestinal bleeding was observed in 20 % of participants, this rate being similar to the ibuprofen group.[38]

Due to the absence of controlled studies, most of the information about the long-term safety of paracetamol comes from observational studies.[37] These indicate a consistent pattern of increased mortality as well as cardiovascular (stroke, myocardial infarction), gastrointestinal (ulcers, bleeding) and renal adverse effects with increased dose of paracetamol.[38][37][81] Use of paracetamol is associated with 1.9 times higher risk of peptic ulcer.[37] Those who take it regularly at a higher dose (more than 2–3 g daily) are at much higher risk (3.6–3.7 times) of gastrointestinal bleeding and other bleeding events.[82] Meta-analyses suggest that paracetamol may increase the risk of kidney impairment by 23 %[83] and kidney cancer by 28 %.[81] Paracetamol slightly but significantly increases blood pressure and heart rate.[37] A 2022 double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study has provided evidence that daily, high-dose use (4 g per day) of paracetamol increases systolic BP.[84][non-primary source needed] A review of available research has suggested that increase in systolic blood pressure and increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with chronic paracetamol use shows a degree of dose dependence.[82]

The association between paracetamol use and asthma in children has been a matter of controversy.[85] However, the most recent research suggests that there is no association,[86] and that the frequency of asthma exacerbations in children after paracetamol is the same as after another frequently used pain killer, ibuprofen.[60]

In recommended doses, the side effects of paracetamol are mild to non-existent.[87] In contrast to aspirin, it is not a blood thinner (and thus may be used in patients where bleeding is a concern), and it does not cause gastric irritation.[88] Compared to Ibuprofen—which can have adverse effects that include diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain—paracetamol is well tolerated with fewer side effects.[89] Prolonged daily use may cause kidney or liver damage.[88][90]Paracetamol is metabolized by the liver and is hepatotoxic; side effects may be more likely in chronic alcoholics or patients with liver damage.[87][91]

Until 2010 paracetamol was believed safe in pregnancy however, in a study published in October 2010 it has been linked to infertility in the adult life of the unborn.[92] Like NSAIDs and unlike opioid analgesics, paracetamol has not been found to cause euphoria or alter mood. One recent research study showed evidence that paracetamol can ease psychological pain, but more studies are needed to draw a stronger conclusion.[93] Unlike aspirin, it is safe for children, as paracetamol is not associated with a risk of Reye's syndrome in children with viral illnesses.[94] Chronic users of paracetamol may have a higher risk of developing blood cancer.[95]

Use in pregnancy

[edit]Paracetamol safety in pregnancy has been under increased scrutiny. There appears to be no link between paracetamol use in the first trimester and adverse pregnancy outcomes or birth defects. However, indications exist of a possible increase in the risk of asthma and developmental and reproductive disorders in the offspring of women with prolonged use of paracetamol during pregnancy.[82]

Paracetamol use by the mother during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of childhood asthma,[96][97] but so are the maternal infections for which paracetamol may be used, and separating these influences is difficult.[82] Paracetamol, in a small-scale meta-analysis was also associated with a 20–30 % increase in autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and conduct disorder, with the association being lower in a meta-analysis where a larger demographic was used, but it is unclear whether this is a causal relationship and whether there was potential bias in the findings.[82][98][99] There is also an argument that the large number, consistency, and robust designs of the studies provide strong evidence in favor of paracetamol causing the increased risk of these neurodevelopmental disorders.[100][101] In animal experiments, paracetamol disrupts fetal testosterone production, and several epidemiological studies linked cryptorchidism with mother's paracetamol use for more than two weeks in the second trimester. On the other hand, several studies did not find any association.[82]

The consensus recommendation appears to be to avoid prolonged use of paracetamol in pregnancy and use it only when necessary, at the lowest effective dosage, and for the shortest time.[82][102][103]

In pregnancy, paracetamol and metoclopramide are deemed safe as are NSAIDs until the third trimester.[104]

Overdose

[edit]Overdose of paracetamol is caused by taking more than the recommended maximum daily dose of paracetamol for healthy adults (three or four grams),[39] and can cause potentially fatal liver damage.[105][106] A single dose should not exceed 1000 mg, doses should be taken no sooner than four hours apart, and no more than four doses (4000 mg) in 24 hours.[39] While a majority of adult overdoses are linked to suicide attempts, many cases are accidental, often due to the use of more than one paracetamol-containing product over an extended period.[107]

Paracetamol toxicity has become the foremost cause of acute liver failure in the United States by 2003,[43] and as of 2005[update], paracetamol accounted for most drug overdoses in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.[108] As of 2004, paracetamol overdose resulted in more calls to poison control centers in the U.S. than overdose of any other pharmacological substance.[109] According to the FDA, in the United States, "56,000 emergency room visits, 26,000 hospitalizations, and 458 deaths per year [were] related to acetaminophen-associated overdoses during the 1990s. Within these estimates, unintentional acetaminophen overdose accounted for nearly 25 % of the emergency department visits, 10 % of the hospitalizations, and 25 % of the deaths."[110][needs update]

Overdoses are frequently related to high-dose recreational use of prescription opioids, as these opioids are most often combined with paracetamol.[111] The overdose risk may be heightened by frequent consumption of alcohol.[112]

Untreated paracetamol overdose results in a lengthy, painful illness. Signs and symptoms of paracetamol toxicity may initially be absent or non-specific symptoms. The first symptoms of overdose usually begin several hours after ingestion, with nausea, vomiting, sweating, and pain as acute liver failure starts.[113] People who take overdoses of paracetamol do not fall asleep or lose consciousness, although most people who attempt suicide with paracetamol wrongly believe that they will be rendered unconscious by the drug.[114][115]

Treatment is aimed at removing the paracetamol from the body and replenishing glutathione.[115] Activated charcoal can be used to decrease absorption of paracetamol if the person comes to the hospital soon after the overdose. While the antidote, acetylcysteine (also called N-acetylcysteine or NAC), acts as a precursor for glutathione, helping the body regenerate enough to prevent or at least decrease the possible damage to the liver; a liver transplant is often required if damage to the liver becomes severe.[41][116]

NAC was usually given following a treatment nomogram (one for people with risk factors, and one for those without), but the use of the nomogram is no longer recommended as evidence to support the use of risk factors was poor and inconsistent, and many of the risk factors are imprecise and difficult to determine with sufficient certainty in clinical practice.[117][118] Toxicity of paracetamol is due to its quinone metabolite NAPQI and NAC also helps in neutralizing it.[115] Kidney failure is also a possible side effect.[112]

Interactions

[edit]Prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide accelerate gastric emptying, shorten time (tmax) to paracetamol peak blood plasma concentration (Cmax), and increase Cmax. Medications slowing gastric emptying such as propantheline and morphine lengthen tmax and decrease Cmax.[119][120] The interaction with morphine may result in patients failing to achieve the therapeutic concentration of paracetamol; the clinical significance of interactions with metoclopramide and propantheline is unclear.[120]

There have been suspicions that cytochrome inducers may enhance the toxic pathway of paracetamol metabolism to NAPQI (see Paracetamol#Pharmacokinetics). By and large, these suspicions have not been confirmed.[120] Out of the inducers studied, the evidence of potentially increased liver toxicity in paracetamol overdose exists for phenobarbital, primidone, isoniazid, and possibly St John's wort.[121] On the other hand, the anti-tuberculosis drug isoniazid cuts the formation of NAPQI by 70%.[120]

Ranitidine increased paracetamol area under the curve (AUC) 1.6-fold. AUC increases are also observed with nizatidine and cisapride. The effect is explained by these drugs inhibiting glucuronidation of paracetamol.[120]

Paracetamol raises plasma concentrations of ethinylestradiol by 22 % by inhibiting its sulfation.[120] Paracetamol increases INR during warfarin therapy and should be limited to no more than 2 g per week.[122][123][124]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Paracetamol appears to exert its effects through two mechanisms: the inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) and actions of its metabolite N-arachidonoylphenolamine (AM404).[125]

Supporting the first mechanism, pharmacologically and in its side effects, paracetamol is close to classical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that act by inhibiting COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes and especially similar to selective COX-2 inhibitors.[126] Paracetamol inhibits prostaglandin synthesis by reducing the active form of COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes. This occurs only when the concentration of arachidonic acid and peroxides is low. Under these conditions, COX-2 is the predominant form of cyclooxygenase, which explains the apparent COX-2 selectivity of paracetamol. Under the conditions of inflammation, the concentration of peroxides is high, which counteracts the reducing effect of paracetamol. Accordingly, the anti-inflammatory action of paracetamol is slight.[125][126] The anti-inflammatory action of paracetamol (via COX inhibition) has also been found to primarily target the central nervous system and not peripheral areas of the body, explaining the lack of side effects associated with conventional NSAIDs such as gastric bleeding.

The second mechanism centers on the paracetamol metabolite AM404. This metabolite has been detected in the brains of animals and cerebrospinal fluid of humans taking paracetamol.[125][127] It is formed in the brain from another paracetamol metabolite 4-aminophenol by action of fatty acid amide hydrolase.[125] AM404 is a weak agonist of cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2, an inhibitor of endocannabinoid transporter, and a potent activator of TRPV1 receptor.[125] This and other research indicate that the endocannabinoid system and TRPV1 may play an important role in the analgesic effect of paracetamol.[125][128]

In 2018, Suemaru et al. found that, in mice, paracetamol exerts an anticonvulsant effect by activation of the TRPV1 receptors[129] and a decrease in neuronal excitability by hyperpolarization of neurons.[130] The exact mechanism of the anticonvulsant effect of acetaminophen is not clear. According to Suemaru et al., acetaminophen and its active metabolite AM404 show a dose-dependent anticonvulsant activity against pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures in mice.[129]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]After being taken by mouth, paracetamol is rapidly absorbed from the small intestine, while absorption from the stomach is negligible. Thus, the rate of absorption depends on stomach emptying. Food slows the stomach's emptying and absorption, but the total amount absorbed stays the same.[131] In the same subjects, the peak plasma concentration of paracetamol was reached after 20 minutes when fasting versus 90 minutes when fed. High carbohydrate (but not high protein or high fat) food decreases paracetamol peak plasma concentration by four times. Even in the fasting state, the rate of absorption of paracetamol is variable and depends on the formulation, with maximum plasma concentration being reached after 20 minutes to 1.5 hours.[6]

Paracetamol's bioavailability is dose-dependent: it increases from 63 % for 500 mg dose to 89 % for 1000 mg dose.[6] Its plasma terminal elimination half-life is 1.9–2.5 hours,[6] and volume of distribution is roughly 50 L.[132] Protein binding is negligible, except under the conditions of overdose, when it may reach 15–21 %.[6] The concentration in serum after a typical dose of paracetamol usually peaks below 30 μg/mL (200 μmol/L).[133] After 4 hours, the concentration is usually less than 10 μg/mL (66 μmol/L).[133]

Paracetamol is metabolized primarily in the liver, mainly by glucuronidation and sulfation, and the products are then eliminated in the urine (see the Scheme on the right). Only 2–5 % of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine.[6] Glucuronidation by UGT1A1 and UGT1A6 accounts for 50–70 % of the drug metabolism. Additional 25–35 % of paracetamol is converted to sulfate by sulfation enzymes SULT1A1, SULT1A3, and SULT1E1.[134]

A minor metabolic pathway (5–15 %) of oxidation by cytochrome P450 enzymes, mainly by CYP2E1, forms a toxic metabolite known as NAPQI (N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine).[134] NAPQI is responsible for the liver toxicity of paracetamol. At usual doses of paracetamol, NAPQI is quickly detoxified by conjugation with glutathione. The non-toxic conjugate APAP-GSH is taken up in the bile and further degraded to mercapturic and cysteine conjugates that are excreted in the urine. In overdose, glutathione is depleted by a large amount of formed NAPQI, and NAPQI binds to mitochondria proteins of the liver cells causing oxidative stress and toxicity.[134]

Yet another minor but important direction of metabolism is deacetylation of 1–2 % of paracetamol to form p-aminophenol. p-Aminophenol is then converted in the brain by fatty acid amide hydrolase into AM404, a compound that may be partially responsible for the analgesic action of paracetamol.[132]

Chemistry

[edit]Synthesis

[edit]Classical methods

[edit]The classical methods for the production of paracetamol involve the acetylation of 4-aminophenol with acetic anhydride as the last step. They differ in how 4-aminophenol is prepared. In one method, nitration of phenol with nitric acid affords 4-nitrophenol, which is reduced to 4-aminophenol by hydrogenation over Raney nickel. In another method, nitrobenzene is reduced electrolytically giving 4-aminophenol directly. Additionally, 4-nitrophenol can be selectively reduced by Tin(II) Chloride in absolute ethanol or ethyl acetate to produce a 91 % yield of 4-aminophenol.[135][136][137]

Celanese synthesis

[edit]An alternative industrial synthesis developed at Celanese involves firstly direct acylation of phenol with acetic anhydride in the presence of hydrogen fluoride to a ketone, then the conversion of the ketone with hydroxylamine to a ketoxime, and finally the acid-catalyzed Beckmann rearrangement of the cetoxime to the para-acetylaminophenol product.[135][138]

Reactions

[edit]

4-Aminophenol may be obtained by the amide hydrolysis of paracetamol. This reaction is also used to determine paracetamol in urine samples: After hydrolysis with hydrochloric acid, 4-aminophenol reacts in ammonia solution with a phenol derivate, e.g. salicylic acid, to form an indophenol dye under oxidization by air.[139]

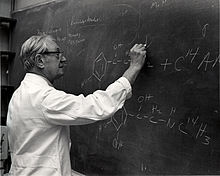

History

[edit]

Acetanilide was the first aniline derivative serendipitously found to possess analgesic as well as antipyretic properties, and was quickly introduced into medical practice under the name of Antifebrin by Cahn & Hepp in 1886.[140] But its unacceptable toxic effects—the most alarming being cyanosis due to methemoglobinemia, an increase of hemoglobin in its ferric [Fe3+] state, called methemoglobin, which cannot bind oxygen, and thus decreases overall carriage of oxygen to tissue—prompted the search for less toxic aniline derivatives.[141] Some reports state that Cahn & Hepp or a French chemist called Charles Gerhardt first synthesized paracetamol in 1852.[45][46]

Harmon Northrop Morse synthesized paracetamol at Johns Hopkins University via the reduction of p-nitrophenol with tin in glacial acetic acid in 1877,[142][143] but it was not until 1887 that clinical pharmacologist Joseph von Mering tried paracetamol on humans.[141] In 1893, von Mering published a paper reporting on the clinical results of paracetamol with phenacetin, another aniline derivative.[144] Von Mering claimed that, unlike phenacetin, paracetamol had a slight tendency to produce methemoglobinemia. Paracetamol was then quickly discarded in favor of phenacetin. The sales of phenacetin established Bayer as a leading pharmaceutical company.[145]

Von Mering's claims remained essentially unchallenged for half a century until two teams of researchers from the United States analyzed the metabolism of acetanilide and phenacetin.[145] In 1947, David Lester and Leon Greenberg found strong evidence that paracetamol was a major metabolite of acetanilide in human blood, and in a subsequent study they reported that large doses of paracetamol given to albino rats did not cause methemoglobinemia.[146] In 1948, Bernard Brodie, Julius Axelrod and Frederick Flinn confirmed that paracetamol was the major metabolite of acetanilide in humans, and established that it was just as efficacious an analgesic as its precursor.[147][148][149] They also suggested that methemoglobinemia is produced in humans mainly by another metabolite, phenylhydroxylamine. A follow-up paper by Brodie and Axelrod in 1949 established that phenacetin was also metabolized to paracetamol.[150] This led to a "rediscovery" of paracetamol.[141]

Paracetamol was first marketed in the United States in 1950 under the name Trigesic, a combination of paracetamol, aspirin, and caffeine.[143] Reports in 1951 of three users stricken with the blood disease agranulocytosis led to its removal from the marketplace, and it took several years until it became clear that the disease was unconnected.[143] The following year, 1952, paracetamol returned to the U.S. market as a prescription drug.[151] In the United Kingdom, marketing of paracetamol began in 1956 by Sterling-Winthrop Co. as Panadol, available only by prescription, and promoted as preferable to aspirin since it was safe for children and people with ulcers.[152][153] In 1963, paracetamol was added to the British Pharmacopoeia, and has gained popularity since then as an analgesic agent with few side-effects and little interaction with other pharmaceutical agents.[152][143]

Concerns about paracetamol's safety delayed its widespread acceptance until the 1970s, but in the 1980s paracetamol sales exceeded those of aspirin in many countries, including the United Kingdom. This was accompanied by the commercial demise of phenacetin, blamed as the cause of analgesic nephropathy and hematological toxicity.[141] Available in the U.S. without a prescription since 1955[151] (1960, according to another source[154]), paracetamol has become a common household drug.[155] In 1988, Sterling Winthrop was acquired by Eastman Kodak which sold the over the counter drug rights to SmithKline Beecham in 1994.[156]

In June 2009, an FDA advisory committee recommended that new restrictions be placed on paracetamol use in the United States to help protect people from the potential toxic effects. The maximum single adult dosage would be decreased from 1000 mg to 650 mg, while combinations of paracetamol and other products would be prohibited. Committee members were particularly concerned by the fact that the then-present maximum dosages of paracetamol had been shown to produce alterations in liver function.[157]

In January 2011, the FDA asked manufacturers of prescription combination products containing paracetamol to limit its amount to no more than 325 mg per tablet or capsule and began requiring manufacturers to update the labels of all prescription combination paracetamol products to warn of the potential risk of severe liver damage.[158][159][160][161][162] Manufacturers had three years to limit the amount of paracetamol in their prescription drug products to 325 mg per dosage unit.[159][161]

In November 2011, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency revised UK dosing of liquid paracetamol for children.[163]

In September 2013, "Use Only as Directed", an episode of the radio program This American Life[164] highlighted deaths from paracetamol overdose. This report was followed by two reports by ProPublica alleging that the "FDA has long been aware of studies showing the risks of acetaminophen. So has the maker of Tylenol, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a division of Johnson & Johnson"[165] and "McNeil, the maker of Tylenol, ... has repeatedly opposed safety warnings, dosage restrictions and other measures meant to safeguard users of the drug."[166]

Society and culture

[edit]

Naming

[edit]Paracetamol is the Australian Approved Name[167] and British Approved Name[168] as well as the international nonproprietary name used by the WHO and in many other countries; acetaminophen is the United States Adopted Name[168] and Japanese Accepted Name and also the name generally used in Canada,[168] Venezuela, Colombia, and Iran.[168][169] Both paracetamol and acetaminophen are contractions of chemical names for the compound. The word "paracetamol" is a shortened form of para-acetylaminophenol,[170] and was coined by Frederick Stearns & Co in 1956,[171] while the word "acetaminophen" is a shortened form of N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP), which was coined and first marketed by McNeil Laboratories in 1955.[172] The initialism APAP is used by dispensing pharmacists in the United States.[173]

Available forms

[edit]Paracetamol is available in oral, suppository, and intravenous forms.[174] Intravenous paracetamol is sold under the brand name Ofirmev in the United States.[175]

In some formulations, paracetamol is combined with the opiate codeine, sometimes referred to as co-codamol (BAN) and Panadeine in Australia. In the U.S., this combination is available only by prescription.[176] As of 1 February 2018, medications containing codeine also became prescription-only in Australia.[177] Paracetamol is also combined with other opioids such as dihydrocodeine,[178] referred to as co-dydramol (British Approved Name (BAN)), oxycodone[179] or hydrocodone.[180] Another very commonly used analgesic combination includes paracetamol in combination with propoxyphene napsylate.[181] A combination of paracetamol, codeine, and the doxylamine succinate is also available.[182]

Paracetamol is sometimes combined with phenylephrine hydrochloride.[183] Sometimes a third active ingredient, such as ascorbic acid,[183][184] caffeine,[185][186] chlorpheniramine maleate,[187] or guaifenesin[188][189][190] is added to this combination.

-

Tylenol 500 mg capsules

-

Panadol 500 mg tablets

-

For comparison: The pure drug is a colourless crystalline powder.

Research

[edit]Claims that paracetamol is an effective analgesic medication to treat symptoms of COVID-19 were found to be unsubstantiated.[191][192][193][194]

Veterinary use

[edit]

Cats

[edit]Paracetamol is extremely toxic to cats, which lack the necessary UGT1A6 enzyme to detoxify it. Initial symptoms include vomiting, salivation, and discoloration of the tongue and gums. Unlike an overdose in humans, liver damage is rarely the cause of death; instead, methemoglobin formation and the production of Heinz bodies in red blood cells inhibit oxygen transport by the blood, causing asphyxiation (methemoglobinemia and hemolytic anemia).[195] Treatment of the toxicosis with acetylcysteine is recommended.[196]

Dogs

[edit]Paracetamol has been reported to be as effective as aspirin in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain in dogs.[197] A paracetamol–codeine product (brand name Pardale-V)[198] licensed for use in dogs is available for purchase under supervision of a vet, pharmacist or other qualified person.[198] It should be administered to dogs only on veterinary advice and with extreme caution.[198]

The main effect of toxicity in dogs is liver damage, and GI ulceration has been reported.[196][199][200][201] Acetylcysteine treatment is efficacious in dogs when administered within two hours of paracetamol ingestion.[196][197]

Snakes

[edit]Paracetamol is lethal to snakes[202] and has been suggested as a chemical control program for the invasive brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) in Guam.[203][204] Doses of 80 mg are inserted into dead mice that are scattered by helicopter[205] as lethal bait to be consumed by the snakes.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ International Drug Names

- ^ "Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 14 June 2019. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Regulatory Decision Summary – Acetaminophen Injection". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Working Group of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine (2015). Schug SA, Palmer GM, Scott DA, Halliwell R, Trinca J (eds.). Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence (4th ed.). Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA), Faculty of Pain Medicine (FPM). ISBN 978-0-9873236-7-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Forrest JA, Clements JA, Prescott LF (1982). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of paracetamol". Clin Pharmacokinet. 7 (2): 93–107. doi:10.2165/00003088-198207020-00001. PMID 7039926. S2CID 20946160.

- ^ "Acetaminophen Pathway (therapeutic doses), Pharmacokinetics". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ a b Pickering G, Macian N, Libert F, Cardot JM, Coissard S, Perovitch P, et al. (September 2014). "Buccal acetaminophen provides fast analgesia: two randomized clinical trials in healthy volunteers". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 8: 1621–1627. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S63476. PMC 4189711. PMID 25302017.

In postoperative conditions for acute pain of mild to moderate intensity, the quickest reported time to onset of analgesia with APAP is 8 minutes9 for the iv route and 37 minutes6 for the oral route.

- ^ "Codapane Forte Paracetamol and codeine phosphate product information" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ Karthikeyan M, Glen RC, Bender A (2005). "General Melting Point Prediction Based on a Diverse Compound Data Set and Artificial Neural Networks". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 45 (3): 581–590. doi:10.1021/ci0500132. PMID 15921448. S2CID 13017241.

- ^ "melting point data for paracetamol". Lxsrv7.oru.edu. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Granberg RA, Rasmuson AC (1999). "Solubility of paracetamol in pure solvents". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 44 (6): 1391–95. doi:10.1021/je990124v.

- ^ a b Prescott LF (March 2000). "Paracetamol: past, present, and future". American Journal of Therapeutics. 7 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1097/00045391-200007020-00011. PMID 11319582. S2CID 7754908.

- ^ a b c d e f Warwick C (November 2008). "Paracetamol and fever management". J R Soc Promot Health. 128 (6): 320–323. doi:10.1177/1466424008092794. PMID 19058473. S2CID 25702228.

- ^ a b c d e f g Saragiotto BT, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG (December 2019). "Paracetamol for pain in adults". BMJ. 367: l6693. doi:10.1136/bmj.l6693. PMID 31892511. S2CID 209524643.

- ^ a b Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ (January 2015). "The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the american headache society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies". Headache. 55 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1111/head.12499. PMID 25600718. S2CID 25576700.

- ^ a b Stephens G, Derry S, Moore RA (June 2016). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute treatment of episodic tension-type headache in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 (6): CD011889. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011889.pub2. PMC 6457822. PMID 27306653.

- ^ a b c Chiumello D, Gotti M, Vergani G (April 2017). "Paracetamol in fever in critically ill patients-an update". J Crit Care. 38: 245–252. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.10.021. PMID 27992852. S2CID 5815020.

- ^ a b de Martino M, Chiarugi A (December 2015). "Recent Advances in Pediatric Use of Oral Paracetamol in Fever and Pain Management". Pain Ther. 4 (2): 149–68. doi:10.1007/s40122-015-0040-z. PMC 4676765. PMID 26518691.

- ^ a b Pierce CA, Voss B (March 2010). "Efficacy and safety of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in children and adults: a meta-analysis and qualitative review". Ann Pharmacother. 44 (3): 489–506. doi:10.1345/aph.1M332. PMID 20150507. S2CID 44669940.

- ^ Meremikwu M, Oyo-Ita A (2002). "Paracetamol for treating fever in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002 (2): CD003676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003676. PMC 6532671. PMID 12076499.

- ^ a b Ludwig J, McWhinnie H (May 2019). "Antipyretic drugs in patients with fever and infection: literature review". Br J Nurs. 28 (10): 610–618. doi:10.12968/bjon.2019.28.10.610. PMID 31116598. S2CID 162182092.

- ^ a b Mayans L, Walling A (February 2018). "Acute Migraine Headache: Treatment Strategies". Am Fam Physician. 97 (4): 243–251. PMID 29671521.

- ^ a b Haag G, Diener HC, May A, Meyer C, Morck H, Straube A, et al. (April 2011). "Self-medication of migraine and tension-type headache: summary of the evidence-based recommendations of the Deutsche Migräne und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (DMKG), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (DGN), the Österreichische Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (ÖKSG) and the Schweizerische Kopfwehgesellschaft (SKG)". J Headache Pain. 12 (2): 201–217. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0266-4. PMC 3075399. PMID 21181425.

- ^ a b c d Bailey E, Worthington HV, van Wijk A, Yates JM, Coulthard P, Afzal Z (December 2013). "Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12): CD004624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004624.pub2. PMC 11561150. PMID 24338830.

- ^ a b c Moore PA, Hersh EV (August 2013). "Combining ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute pain management after third-molar extractions: translating clinical research to dental practice". J Am Dent Assoc. 144 (8): 898–908. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0207. PMID 23904576.

- ^ a b c d e Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Lin CW, Day RO, et al. (March 2015). "Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials". BMJ. 350: h1225. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1225. PMC 4381278. PMID 25828856.

- ^ a b c Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. (February 2020). "2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee". Arthritis Care & Research. 72 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1002/acr.24131. hdl:2027.42/153772. PMC 11488261. PMID 31908149. S2CID 210043648.

- ^ a b c Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA (April 2017). "Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians". Ann Intern Med. 166 (7): 514–530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367. PMID 28192789. S2CID 207538763.

- ^ a b Saragiotto BT, Machado GC, Ferreira ML, Pinheiro MB, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG (June 2016). "Paracetamol for low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6 (6): CD012230. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012230. PMC 6353046. PMID 27271789.

- ^ a b Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, McNicol ED, Bell RF, Carr DB, et al. (July 2017). "Oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) for cancer pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7 (2): CD012637. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012637.pub2. PMC 6369932. PMID 28700092.

- ^ a b Wiffen PJ, Knaggs R, Derry S, Cole P, Phillips T, Moore RA (December 2016). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without codeine or dihydrocodeine for neuropathic pain in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12 (5): CD012227. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012227.pub2. PMC 6463878. PMID 28027389.

- ^ "Acetaminophen". Health Canada. 11 October 2012. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Southey ER, Soares-Weiser K, Kleijnen J (September 2009). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical safety and tolerability of ibuprofen compared with paracetamol in paediatric pain and fever". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 25 (9): 2207–2222. doi:10.1185/03007990903116255. PMID 19606950. S2CID 31653539. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "Acetaminophen vs Ibuprofen: Which is better?". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Moore RA, Moore N (July 2016). "Paracetamol and pain: the kiloton problem". European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 23 (4): 187–188. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000952. PMC 6451482. PMID 31156845.

- ^ a b c d e f Conaghan PG, Arden N, Avouac B, Migliore A, Rizzoli R (April 2019). "Safety of Paracetamol in Osteoarthritis: What Does the Literature Say?". Drugs Aging. 36 (Suppl 1): 7–14. doi:10.1007/s40266-019-00658-9. PMC 6509082. PMID 31073920.

- ^ a b c Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, Latchem S, Constanti M, Miller P, et al. (March 2016). "Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies". Ann Rheum Dis. 75 (3): 552–9. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206914. PMC 4789700. PMID 25732175.

- ^ a b c "Paracetamol for adults: painkiller to treat aches, pains and fever". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Acetaminophen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ a b Daly FF, Fountain JS, Murray L, Graudins A, Buckley NA (March 2008). "Guidelines for the management of paracetamol poisoning in Australia and New Zealand—explanation and elaboration. A consensus statement from clinical toxicologists consulting to the Australasian poisons information centres". The Medical Journal of Australia. 188 (5): 296–301. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01625.x. PMID 18312195. S2CID 9505802.

- ^ Hawkins LC, Edwards JN, Dargan PI (2007). "Impact of restricting paracetamol pack sizes on paracetamol poisoning in the United Kingdom: a review of the literature". Drug Saf. 30 (6): 465–79. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730060-00002. PMID 17536874. S2CID 36435353.

- ^ a b Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, et al. (2005). "Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study". Hepatology. 42 (6): 1364–72. doi:10.1002/hep.20948. PMID 16317692. S2CID 24758491.

- ^ Mangus BC, Miller MG (2005). Pharmacology application in athletic training. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: F.A. Davis. p. 39. ISBN 9780803620278. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ a b Eyers SJ (April 2012). The effect of regular paracetamol on bronchial responsiveness and asthma control in mild to moderate asthma (Ph.D. thesis). University of Otago). Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b Roy J (2011). "Paracetamol – the best selling antipyretic analgesic in the world". An introduction to pharmaceutical sciences: production, chemistry, techniques and technology. Oxford: Biohealthcare. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-908818-04-1. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Aghababian RV (22 October 2010). Essentials of emergency medicine. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 814. ISBN 978-1-4496-1846-9. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ Hamilton RJ (2013). Tarascon pocket pharmacopeia: 2013 classic shirt-pocket edition (27th ed.). Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 12. ISBN 9781449665869. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Acetaminophen Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Li S, Yue J, Dong BR, Yang M, Lin X, Wu T (July 2013). "Acetaminophen (paracetamol) for the common cold in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 (7): CD008800. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008800.pub2. PMC 7389565. PMID 23818046.

- ^ de Ridder IR, den Hertog HM, van Gemert HM, Schreuder AH, Ruitenberg A, Maasland EL, et al. (April 2017). "PAIS 2 (Paracetamol [Acetaminophen] in Stroke 2): Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial". Stroke. 48 (4): 977–982. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015957. PMID 28289240.

- ^ Deen J, von Seidlein L (May 2019). "Paracetamol for dengue fever: no benefit and potential harm?". Lancet Glob Health. 7 (5): e552 – e553. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30157-3. PMID 31000122.

- ^ Meremikwu M, Oyo-Ita A (2002). "Paracetamol for treating fever in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002 (2): CD003676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003676. PMC 6532671. PMID 12076499.

- ^ a b c "Recommendations. Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management". nice.org.uk. 7 November 2019. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021.

- ^ Hashimoto R, Suto M, Tsuji M, Sasaki H, Takehara K, Ishiguro A, et al. (April 2021). "Use of antipyretics for preventing febrile seizure recurrence in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Eur J Pediatr. 180 (4): 987–997. doi:10.1007/s00431-020-03845-8. PMID 33125519. S2CID 225994044.

- ^ Narayan K, Cooper S, Morphet J, Innes K (August 2017). "Effectiveness of paracetamol versus ibuprofen administration in febrile children: A systematic literature review". J Paediatr Child Health. 53 (8): 800–807. doi:10.1111/jpc.13507. PMID 28437025. S2CID 395470.

- ^ Tan E, Braithwaite I, McKinlay CJ, Dalziel SR (October 2020). "Comparison of Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) With Ibuprofen for Treatment of Fever or Pain in Children Younger Than 2 Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Netw Open. 3 (10): e2022398. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22398. PMC 7599455. PMID 33125495.

- ^ a b Sherbash M, Furuya-Kanamori L, Nader JD, Thalib L (March 2020). "Risk of wheezing and asthma exacerbation in children treated with paracetamol versus ibuprofen: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMC Pulm Med. 20 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/s12890-020-1102-5. PMC 7087361. PMID 32293369.

- ^ Bertolini A, Ferrari A, Ottani A, Guerzoni S, Tacchi R, Leone S (2006). "Paracetamol: new vistas of an old drug". CNS Drug Rev. 12 (3–4): 250–75. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00250.x. PMC 6506194. PMID 17227290.

- ^ Kloppenburg M, Kroon FP, Blanco FJ, Doherty M, Dziedzic KS, Greibrokk E, et al. (January 2019). "2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis". Ann Rheum Dis. 78 (1): 16–24. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826. PMID 30154087.

- ^ Bruyère O, Honvo G, Veronese N, Arden NK, Branco J, Curtis EM, et al. (December 2019). "An updated algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO)". Semin Arthritis Rheum. 49 (3): 337–350. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.04.008. hdl:10447/460208. PMID 31126594.

- ^ Derry S, Moore RA (2013). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4 (4): CD008040. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008040.pub3. PMC 4161111. PMID 23633349.

- ^ Diener HC, Gold M, Hagen M (November 2014). "Use of a fixed combination of acetylsalicylic acid, acetaminophen and caffeine compared with acetaminophen alone in episodic tension-type headache: meta-analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover studies". J Headache Pain. 15 (1): 76. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-76. PMC 4256978. PMID 25406671.

- ^ Pergolizzi JV, Magnusson P, LeQuang JA, Gharibo C, Varrassi G (April 2020). "The pharmacological management of dental pain". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 21 (5): 591–601. doi:10.1080/14656566.2020.1718651. PMID 32027199. S2CID 211046298.

- ^ Hersh EV, Moore PA, Grosser T, Polomano RC, Farrar JT, Saraghi M, et al. (July 2020). "Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Opioids in Postsurgical Dental Pain". J Dent Res. 99 (7): 777–786. doi:10.1177/0022034520914254. PMC 7313348. PMID 32286125.

- ^ Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (June 2013). "Single dose oral ibuprofen plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 (6): CD010210. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010210.pub2. PMC 6485825. PMID 23794268.

- ^ Daniels SE, Atkinson HC, Stanescu I, Frampton C (October 2018). "Analgesic Efficacy of an Acetaminophen/Ibuprofen Fixed-dose Combination in Moderate to Severe Postoperative Dental Pain: A Randomized, Double-blind, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled Trial". Clin Ther. 40 (10): 1765–1776.e5. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.08.019. PMID 30245281.

- ^ Toms L, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (January 2009). "Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine for postoperative pain in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 (1): CD001547. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001547.pub2. PMC 4171965. PMID 19160199.

- ^ Allegaert K (2020). "A Critical Review on the Relevance of Paracetamol for Procedural Pain Management in Neonates". Front Pediatr. 8: 89. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.00089. PMC 7093493. PMID 32257982.

- ^ Ohlsson A, Shah PS (January 2020). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for prevention or treatment of pain in newborns". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD011219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011219.pub4. PMC 6984663. PMID 31985830.

- ^ Wuytack F, Smith V, Cleary BJ (January 2021). "Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (single dose) for perineal pain in the early postpartum period". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1 (1): CD011352. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011352.pub3. PMC 8092572. PMID 33427305.

- ^ Sin B, Wai M, Tatunchak T, Motov SM (May 2016). "The Use of Intravenous Acetaminophen for Acute Pain in the Emergency Department". Academic Emergency Medicine. 23 (5): 543–53. doi:10.1111/acem.12921. PMID 26824905.

- ^ Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (March 2012). Derry S (ed.). "Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD009281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009281.pub2. PMID 22419343. S2CID 205199173.

- ^ a b Jasani B, Mitra S, Shah PS (December 2022). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (12): CD010061. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010061.pub5. PMC 6984659. PMID 36519620.

- ^ Keaveney A, Peters E, Way B (September 2020). "Effects of acetaminophen on risk taking". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 15 (7): 725–732. doi:10.1093/scan/nsaa108. PMC 7511878. PMID 32888031.

- ^ a b "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns of rare but serious skin reactions with the pain reliever/fever reducer acetaminophen". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 August 2013. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Lebrun-Vignes B, Guy C, Jean-Pastor MJ, Gras-Champel V, Zenut M (February 2018). "Is acetaminophen associated with a risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis? Analysis of the French Pharmacovigilance Database". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 84 (2): 331–338. doi:10.1111/bcp.13445. PMC 5777438. PMID 28963996.

- ^ Leopoldino AO, Machado GC, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Day R, McLachlan AJ, et al. (February 2019). "Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2 (8): CD013273. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013273. PMC 6388567. PMID 30801133.

- ^ a b Choueiri TK, Je Y, Cho E (January 2014). "Analgesic use and the risk of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies". Int J Cancer. 134 (2): 384–96. doi:10.1002/ijc.28093. PMC 3815746. PMID 23400756.

- ^ a b c d e f g McCrae JC, Morrison EE, MacIntyre IM, Dear JW, Webb DJ (October 2018). "Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol – a review". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 84 (10): 2218–2230. doi:10.1111/bcp.13656. PMC 6138494. PMID 29863746.

- ^ Kanchanasurakit S, Arsu A, Siriplabpla W, Duangjai A, Saokaew S (March 2020). "Acetaminophen use and risk of renal impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Kidney Res Clin Pract. 39 (1): 81–92. doi:10.23876/j.krcp.19.106. PMC 7105620. PMID 32172553.

- ^ MacIntyre IM, Turtle EJ, Farrah TE, Graham C, Dear JW, Webb DJ (February 2022). "Regular Acetaminophen Use and Blood Pressure in People With Hypertension: The PATH-BP Trial". Circulation. 145 (6): 416–423. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056015. PMC 7612370. PMID 35130054.

- ^ Lourido-Cebreiro T, Salgado FJ, Valdes L, Gonzalez-Barcala FJ (January 2017). "The association between paracetamol and asthma is still under debate". The Journal of Asthma (Review). 54 (1): 32–8. doi:10.1080/02770903.2016.1194431. PMID 27575940. S2CID 107851.

- ^ Cheelo M, Lodge CJ, Dharmage SC, Simpson JA, Matheson M, Heinrich J, et al. (January 2015). "Paracetamol exposure in pregnancy and early childhood and development of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 100 (1): 81–9. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303043. PMID 25429049. S2CID 13520462. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ a b Hughes J (2008). Pain Management: From Basics to Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780443103360.

- ^ a b Sarg M, Ann D Gross, Roberta Altman (2007). The Cancer Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978081606-4113.

- ^ Ebrahimi S, Soheil Ashkani Esfahani, Hamid Reza Ghaffarian, Mahsima Khoshneviszade (2010). "Comparison of efficacy and safety of acetaminophen and ibuprofen administration as single dose to reduce fever in children". Iranian Journal of Pediatrics. 20 (4): 500–501. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Painkillers 'cause kidney damage'". BBC News. 23 November 2003. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Dukes M, Jeffrey K Aronson (2000). Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs, Vol XIV. Elsevier. ISBN 9780444500939.

- ^ Leffers, H, et al. (2010). "Intrauterine exposure to mild analgesics is a risk factor for development of male reproductive disorders in human and rat". Human Reproduction. 25 (1): 235–244. doi:10.1093/humrep/deq382.

- ^ "Could Tylenol Ease Emotional Pain?". Evergreen Magazine. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ Lesko SM, Mitchell AA (1999). "The safety of acetaminophen and ibuprofen among children younger than two years old". Pediatrics. 104 (4): e39. doi:10.1542/peds.104.4.e39. PMID 10506264. S2CID 3107281.

- ^ Roland B. Walter, Filippo Milano, Theodore M. Brasky, Emily White (2011). "Long-Term Use of Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and Other Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Hematologic Malignancies: Results From the Prospective Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) Study". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (17): 2424–31. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.34.6346. PMC 3107756. PMID 21555699.

- ^ Eyers S, Weatherall M, Jefferies S, Beasley R (April 2011). "Paracetamol in pregnancy and the risk of wheezing in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 41 (4): 482–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03691.x. PMID 21338428. S2CID 205275267.

- ^ Fan G, Wang B, Liu C, Li D (2017). "Prenatal paracetamol use and asthma in childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 45 (6): 528–533. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2016.10.014. PMID 28237129.

- ^ Masarwa R, Levine H, Gorelik E, Reif S, Perlman A, Matok I (August 2018). "Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression Analysis of Cohort Studies". Am J Epidemiol. 187 (8): 1817–1827. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy086. PMID 29688261.

- ^ Ji Y, Azuine RE, Zhang Y, Hou W, Hong X, Wang G, et al. (February 2020). "Association of Cord Plasma Biomarkers of In Utero Acetaminophen Exposure With Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Childhood". JAMA Psychiatry. 77 (2): 180–189. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3259. PMC 6822099. PMID 31664451.

- ^ Bauer AZ, Kriebel D, Herbert MR, Bornehag CG, Swan SH (May 2018). "Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A review". Horm Behav. 101: 125–147. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.01.003. PMID 29341895. S2CID 4822468.

- ^ Gou X, Wang Y, Tang Y, Qu Y, Tang J, Shi J, et al. (March 2019). "Association of maternal prenatal acetaminophen use with the risk of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: A meta-analysis". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 53 (3): 195–206. doi:10.1177/0004867418823276. PMID 30654621. S2CID 58575048.

- ^ Toda K (October 2017). "Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?". Scand J Pain. 17: 445–446. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.09.007. PMID 28986045. S2CID 205183310.

- ^ Black E, Khor KE, Kennedy D, Chutatape A, Sharma S, Vancaillie T, et al. (November 2019). "Medication Use and Pain Management in Pregnancy: A Critical Review". Pain Pract. 19 (8): 875–899. doi:10.1111/papr.12814. PMID 31242344. S2CID 195694287.

- ^ Gilmore B, Michael, M (1 February 2011). "Treatment of acute migraine headache". American Family Physician. 83 (3): 271–80. PMID 21302868.

- ^ "Acetaminophen Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Using Acetaminophen and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Safely". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 26 February 2018. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Amar PJ, Schiff ER (July 2007). "Acetaminophen safety and hepatotoxicity--where do we go from here?". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 6 (4): 341–355. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.4.341. PMID 17688378. S2CID 20399748.

- ^ Buckley N, Eddleston M (December 2005). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning". Clinical Evidence (14): 1738–1744. PMID 16620471.

- ^ Lee WM (2004). "Acetaminophen and the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group: lowering the risks of hepatic failure". Hepatology. 40 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1002/hep.20293. PMID 15239078. S2CID 15485538.

- ^ "Prescription Drug Products Containing Acetaminophen: Actions to Reduce Liver Injury from Unintentional Overdose". regulations.gov. US Food and Drug Administration. 14 January 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Yan H (16 January 2014). "FDA: Acetaminophen doses over 325 mg may lead to liver damage". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ a b Lee WM (December 2017). "Acetaminophen (APAP) hepatotoxicity—Isn't it time for APAP to go away?". Journal of Hepatology. 67 (6): 1324–1331. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.005. PMC 5696016. PMID 28734939.

- ^ Rumack B, Matthew H (1975). "Acetaminophen poisoning and toxicity". Pediatrics. 55 (6): 871–876. doi:10.1542/peds.55.6.871. PMID 1134886. S2CID 45739342.

- ^ "Paracetamol". University of Oxford Centre for Suicide Research. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Mehta S (25 August 2012). "Metabolism of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen), Acetanilide and Phenacetin". PharmaXChange.info. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Highlights of Prescribing Information" (PDF). Acetadote. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Paracetamol overdose: new guidance on treatment with intravenous acetylcysteine". Drug Safety Update. September 2012. pp. A1. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012.

- ^ "Treating paracetamol overdose with intravenous acetylcysteine: new guidance". GOV.UK. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Nimmo J, Heading RC, Tothill P, Prescott LF (March 1973). "Pharmacological modification of gastric emptying: effects of propantheline and metoclopromide on paracetamol absorption". Br Med J. 1 (5853): 587–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5853.587. PMC 1589913. PMID 4694406.

- ^ a b c d e f Toes MJ, Jones AL, Prescott L (2005). "Drug interactions with paracetamol". Am J Ther. 12 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1097/00045391-200501000-00009. PMID 15662293. S2CID 39595470.

- ^ Kalsi SS, Wood DM, Waring WS, Dargan PI (2011). "Does cytochrome P450 liver isoenzyme induction increase the risk of liver toxicity after paracetamol overdose?". Open Access Emerg Med. 3: 69–76. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S24962. PMC 4753969. PMID 27147854.

- ^ Pinson GM, Beall JW, Kyle JA (October 2013). "A review of warfarin dosing with concurrent acetaminophen therapy". J Pharm Pract. 26 (5): 518–21. doi:10.1177/0897190013488802. PMID 23736105. S2CID 31588052.

- ^ Hughes GJ, Patel PN, Saxena N (June 2011). "Effect of acetaminophen on international normalized ratio in patients receiving warfarin therapy". Pharmacotherapy. 31 (6): 591–7. doi:10.1592/phco.31.6.591. PMID 21923443. S2CID 28548170.

- ^ Zhang Q, Bal-dit-Sollier C, Drouet L, Simoneau G, Alvarez JC, Pruvot S, et al. (March 2011). "Interaction between acetaminophen and warfarin in adults receiving long-term oral anticoagulants: a randomized controlled trial". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 67 (3): 309–14. doi:10.1007/s00228-010-0975-2. PMID 21191575. S2CID 25988269.

- ^ a b c d e f Ghanem CI, Pérez MJ, Manautou JE, Mottino AD (July 2016). "Acetaminophen from liver to brain: New insights into drug pharmacological action and toxicity". Pharmacological Research. 109: 119–31. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.020. PMC 4912877. PMID 26921661.

- ^ a b Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, Mohamudally A, Scott KF (June 2013). "The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings". Inflammopharmacology. 21 (3): 201–32. doi:10.1007/s10787-013-0172-x. PMID 23719833. S2CID 11359488.

- ^ Sharma CV, Long JH, Shah S, Rahman J, Perrett D, Ayoub SS, et al. (2017). "First evidence of the conversion of paracetamol to AM404 in human cerebrospinal fluid". J Pain Res. 10: 2703–2709. doi:10.2147/JPR.S143500. PMC 5716395. PMID 29238213.

- ^ Ohashi N, Kohno T (2020). "Analgesic Effect of Acetaminophen: A Review of Known and Novel Mechanisms of Action". Front Pharmacol. 11: 580289. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.580289. PMC 7734311. PMID 33328986.

- ^ a b Suemaru K, Yoshikawa M, Aso H, Watanabe M (September 2018). "TRPV1 mediates the anticonvulsant effects of acetaminophen in mice". Epilepsy Research. 145: 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.06.016. PMID 30007240. S2CID 51652230.

- ^ Ray S, Salzer I, Kronschläger MT, Boehm S (April 2019). "The paracetamol metabolite N-acetylp-benzoquinone imine reduces excitability in first- and second-order neurons of the pain pathway through actions on KV7 channels". Pain. 160 (4): 954–964. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001474. PMC 6430418. PMID 30601242.

- ^ Prescott LF (October 1980). "Kinetics and metabolism of paracetamol and phenacetin". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (Suppl 2): 291S – 298S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb01812.x. PMC 1430174. PMID 7002186.

- ^ a b Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, Mohamudally A, Scott KF (June 2013). "The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: Therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity, and recent pharmacological findings". Inflammopharmacology. 21 (3): 201–232. doi:10.1007/s10787-013-0172-x. PMID 23719833. S2CID 11359488.

- ^ a b Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger R (2013). Rosen's Emergency Medicine – Concepts and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455749874.

- ^ a b c McGill MR, Jaeschke H (September 2013). "Metabolism and disposition of acetaminophen: recent advances in relation to hepatotoxicity and diagnosis". Pharm Res. 30 (9): 2174–87. doi:10.1007/s11095-013-1007-6. PMC 3709007. PMID 23462933.

- ^ a b Friderichs E, Christoph T, Buschmann H (15 July 2007). "Analgesics and Antipyretics". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_269.pub2. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ "US Patent 2998450". Archived from the original on 14 April 2021.

- ^ Bellamy FD, Ou K (January 1984). "Selective reduction of aromatic nitro compounds with stannous chloride in non acidic and non aqueous medium". Tetrahedron Letters. 25 (8): 839–842. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80041-1.

- ^ US patent 4524217, Davenport KG, Hilton CB, "Process for producing N-acyl-hydroxy aromatic amines", published 18 June 1985, assigned to Celanese Corporation

- ^ Novotny PE, Elser RC (1984). "Indophenol method for acetaminophen in serum examined". Clin. Chem. 30 (6): 884–6. doi:10.1093/clinchem/30.6.884. PMID 6723045.

- ^ Cahn A, Hepp P (1886). "Das Antifebrin, ein neues Fiebermittel" [Antifebrin, a new antipyretic]. Centralblatt für klinische Medizin (in German). 7: 561–4. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Bertolini A, Ferrari A, Ottani A, Guerzoni S, Tacchi R, Leone S (2006). "Paracetamol: New vistas of an old drug". CNS Drug Reviews. 12 (3–4): 250–75. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00250.x. PMC 6506194. PMID 17227290.

- ^ Morse HN (1878). "Ueber eine neue Darstellungsmethode der Acetylamidophenole" [On a new method of preparing acetylamidophenol]. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 11 (1): 232–233. doi:10.1002/cber.18780110151. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d Silverman M, Lydecker M, Lee PR (1992). Bad Medicine: The Prescription Drug Industry in the Third World. Stanford University Press. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-0804716697.

- ^ von Mering J (1893). "Beitrage zur Kenntniss der Antipyretica". Ther Monatsch. 7: 577–587.

- ^ a b Sneader W (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 439. ISBN 978-0471899808. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016.

- ^ Lester D, Greenberg LA, Carroll RP (1947). "The metabolic fate of acetanilid and other aniline derivatives: II. Major metabolites of acetanilid appearing in the blood". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 90 (1): 68–75. PMID 20241897. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008.

- ^ Brodie BB, Axelrod J (1948). "The estimation of acetanilide and its metabolic products, aniline, N-acetyl p-aminophenol and p-aminophenol (free and total conjugated) in biological fluids and tissues". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 22–28. PMID 18885610.

- ^ Brodie BB, Axelrod J (September 1948). "The fate of acetanilide in man" (PDF). The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 94 (1): 29–38. PMID 18885611. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2008.

- ^ Flinn FB, Brodie BB (1948). "The effect on the pain threshold of N-acetyl p-aminophenol, a product derived in the body from acetanilide". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 76–77. PMID 18885618.

- ^ Brodie BB, Axelrod J (September 1949). "The fate of acetophenetidin in man and methods for the estimation of acetophenetidin and its metabolites in biological material". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 97 (1): 58–67. PMID 18140117.

- ^ a b Ameer B, Greenblatt DJ (August 1977). "Acetaminophen". Ann Intern Med. 87 (2): 202–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-87-2-202. PMID 329728.

- ^ a b Spooner JB, Harvey JG (1976). "The history and usage of paracetamol". J Int Med Res. 4 (4 Suppl): 1–6. doi:10.1177/14732300760040S403. PMID 799998. S2CID 11289061.

- ^ Landau R, Achilladelis B, Scriabine A (1999). Pharmaceutical Innovation: Revolutionizing Human Health. Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-941901-21-5. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ "Our Story". McNEIL-PPC, Inc. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ "Medication and Drugs". MedicineNet. 1996–2010. Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ "SEC Info – Eastman Kodak Co – '8-K' for 6/30/94". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "FDA May Restrict Acetaminophen". Webmd. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Prescription Acetaminophen Products to be Limited to 325 mg Per Dosage Unit; Boxed Warning Will Highlight Potential for Severe Liver Failure". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Perrone M (13 January 2011). "FDA orders lowering pain reliever in Vicodin". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ a b Harris G (13 January 2011). "F.D.A. Plans New Limits on Prescription Painkillers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ "FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 January 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Liquid paracetamol for children: revised UK dosing instructions introduced" (PDF). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 14 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "Use Only as Directed". This American Life. Episode 505. Chicago. 20 September 2013. Public Radio International. WBEZ. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Gerth J, Miller TC (20 September 2013). "Use Only as Directed". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Miller TC, Gerth J (20 September 2013). "Dose of Confusion". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Section 1 – Chemical Substances". TGA Approved Terminology for Medicines (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government. July 1999. p. 97. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Macintyre P, Rowbotham D, Walker S (26 September 2008). Clinical Pain Management Second Edition: Acute Pain. CRC Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-340-94009-9. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- ^ "International Non-Proprietary Name for Pharmaceutical Preparations (Recommended List #4)" (PDF). WHO Chronicle. 16 (3): 101–111. March 1962. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "Definition of PARACETAMOL". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "A History of Paracetamol, Its Various Uses & How It Affects You". FeverMates. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "Definition of ACETAMINOPHEN". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Gaunt MJ (8 October 2013). "APAP: An Error-Prone Abbreviation". Pharmacy Times. October 2013 Diabetes. 79 (10). Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Acetaminophen". Physicians' Desk Reference (63rd ed.). Montvale, N.J.: Physicians' Desk Reference. 2009. pp. 1915–1916. ISBN 978-1-56363-703-2. OCLC 276871036.

- ^ Nam S. "IV, PO, and PR Acetaminophen: A Quick Comparison". Pharmacy Times. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "Acetaminophen and Codeine (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 29 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Codeine information hub". Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australian Government. 10 April 2018. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Dihydrocodeine (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 2 October 2019. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Oxycodone and Acetaminophen (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 11 November 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Hydrocodone and Acetaminophen (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Propoxyphene and Acetaminophen Tablets". Drugs.com. 21 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "APOHealth Paracetamol Plus Codeine & Calmative". Drugs.com. 3 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ a b Atkinson HC, Stanescu I, Anderson BJ (2014). "Increased Phenylephrine Plasma Levels with Administration of Acetaminophen". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (12): 1171–1172. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1313942. hdl:2292/34799. PMID 24645960.

- ^ "Ascorbic acid/Phenylephrine/Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Phenylephrine/Caffeine/Paracetamol dual relief". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.