German American Bund

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

The German American Bund or German American Federation (German: Amerikadeutscher Bund) was an American Nazi organization established in the 1930s. Its main goal was to promote a favorable view of Nazi Germany.

Friends of New Germany

NSDAP member Heinz Spanknöbel merged two older organizations, Gau-USA, and the Free Society of Teutonia, which were both small groups with only a few hundred members each, into Friends of New Germany. One of its early initiatives was to counter, with propaganda, a Jewish boycott of businesses in the heavily German neighborhood of Yorkville, Manhattan. Simultaneously, an internal battle was fought for control of the Friends in 1934; Spanknöbel was ultimately ousted from leadership. At the same time, the Dickstein investigation concluded that the Friends supported a branch of German dictator Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party in America.[1]

American Führer

After the investigation, Hitler advised all German nationals to withdraw from the Friends of New Germany. On March 19, 1936, Hitler placed an American citizen, Fritz Julius Kuhn, as the head of the party.[2] The group's name was then changed to the German American Bund. At this time, the Bund established two training camps, Camp Nordlund in Sussex County, New Jersey and Camp Siegfried in Yaphank, New York.[3][4]

After taking over in 1936, Kuhn started to attract attention to the Bund through short propaganda films that outlined the Bund's views. Later that year, Fritz Kuhn and some fifty Bund members boarded a boat to Germany, hoping to receive personal and official recognition from German Chancellor (Reichskanzler) Adolf Hitler during the Berlin Olympics. However, according to historian Charles Higham, Kuhn was one of the last people Hitler wanted to meet. Hitler wanted the American Bund to remain non-aggressive and relatively obscure. However, Kuhn did briefly meet with Hitler during a reception before the opening ceremonies.

Zenith

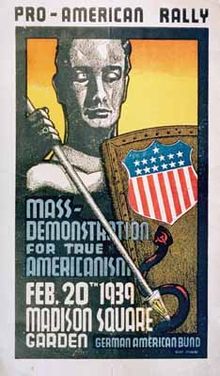

Arguably, the zenith of the Bund's history occurred on President's Day, February 20, 1939 at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Some 20,000 people attended and heard Kuhn criticize President Franklin D. Roosevelt by repeatedly referring to him as “Frank D. Rosenfeld”, calling his New Deal the "Jew Deal", and stating his belief of Bolshevik-Jewish American leadership. Most shocking to American sensibilities was the outbreak of violence between protesters and Bund storm troopers.

The Bund was one of several German-American heritage groups; however, it was one of the few to express National Socialist ideals. As a result, many considered the group anti-American. In the last week of December 1942, led by journalist Dorothy Thompson, fifty leading German-Americans including Babe Ruth signed a "Christmas Declaration by men and women of German ancestry" condemning Nazism, which appeared in ten major American daily newspapers. In 1939, a New York tax investigation determined Kuhn had embezzled money from the Bund. The Bund operated on the theory that the leader's powers were absolute, and therefore did not seek prosecution. However, in an attempt to cripple the Bund, the New York district attorney prosecuted Kuhn. New Bund leaders would replace Kuhn, most notably with Wilhelm Kunze, but these were only brief stints. Martin Dies and the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) were very active in denying any Nazi-sympathetic organization the ability to freely operate during World War II.

See also

- Friends of New Germany

- Free Society of Teutonia

- Silver Legion of America

- Neo-Nazi groups of the United States

- Erich Traub

- Fascist League of North America

References

- ^ Shaffer, Ryan (Volume 21, Issue 2, Spring 2010). "Long Island Nazis: A Local Synthesis of Transnational Politics". Journal of Long Island History. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Fritz Kuhn Death in 1951 Revealed. Lawyer Says Former Leader of German-American Bund Succumbed in [[Munich]]". Associated Press in New York Times. February 2, 1953. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

Fritz Kuhn, once the arrogant, noisy leader of the pro-Hitler German-American Bund, died here more than a year ago -- a poor and obscure chemist, unheralded and unsung.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Jackson, Kenneth T. The Encyclopedia of New York City. The New York Historical Society, Yale University Press, 1995. P. 462.

- ^ David Mark Chalmers (1987). Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. ISBN 0822307723.

When Arthur Bell, your Grand Giant, and Mr. Smythe asked us about using Camp Nordlund for this patriotic meeting, we decided to let them have it because of ...

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Leland V. Bell In Hitler's Shadow; The Anatomy of American Nazism, 1973

- Susan Canedy; Americas Nazis: A Democratic Dilemma a History of the German American Bund Markgraf Pubns Group, 1990

- Philip Jenkins; Hoods and Shirts: The Extreme Right in Pennsylvania, 1925-1950 University of North Carolina Press, 1997

- Francis MacDonnell; Insidious Foes: The Axis Fifth Column and the American Home Front Oxford University Press, 1995

- Marvin D. Miller; Wunderlich's Salute: The Interrelationship of the German-American Bund, Camp Siegfried, Yaphank, Long Island, and the Young Siegfrieds and Their Relationship with American and Nazi Institutions Malamud-Rose Publishers, November 1983(1st Edition)

- Stephen H. Norwood; "Marauding Youth and the Christian Front: Antisemitic Violence in Boston and New York during World War II" American Jewish History, Vol. 91, 2003

- James C. Schneider; Should America Go to War? The Debate over Foreign Policy in Chicago, 1939-1941 University of North Carolina Press, 1989

- Maximilian St.-George and Lawrence Dennis; A Trial on Trial: The Great Sedition Trial of 1944 National Civil Rights Committee, 1946, defendants' point of view

- Donald S. Strong; Organized Anti-Semitism in America: The Rise of Group Prejudice during the Decade 1930-40 1941

- Mark D. Van Ells, "Americans for Hitler," America in WW2 3:2 (August 2007), pp. 44-49.

- Diamond, Sander. The Nazi Movement in the United States: 1924-1941. Ithaca: Cornell University, 1974.

External links

- Collection of articles in the Mid-Island Mail related to Bund activity in Yaphank, New York(1935-1941) (Longwood Public Library)

- Free America - A transcript of speeches made at the Bund's Madison Square Garden rally, 20 Feb. 1939

- Mp3 of National Leader Fritz Julius Kuhn address at the Madison Square Garden rally

- What Price the Federal Reserve? illustrated anti-semitic pamphlet issued by the Bund

- German-American Bund.org

- U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum article on German-American Bund

- Film footage of the Bund