Liverpool Street station

| Liverpool Street | |

|---|---|

| London Liverpool Street | |

Main station concourse | |

| Location | Liverpool Street/Bishopsgate |

| Local authority | City of London |

| Managed by | Network Rail |

| Station code(s) | LST |

| DfT category | A |

| Number of platforms | 18 |

| Accessible | Yes[1] |

| Fare zone | 1 |

| OSI | Bank Fenchurch Street |

| National Rail annual entry and exit | |

| 2008–09 | |

| 2009–10 | |

| 2010–11 | |

| 2011–12 | |

| 2012–13 | |

| 2013–14 | |

| – interchange | 2.912 million[3] |

| 2014–15 | |

| – interchange | |

| Railway companies | |

| Original company | Great Eastern Railway |

| Post-grouping | London & North Eastern Railway |

| Key dates | |

| 1874 | Opened |

| Other information | |

| External links | |

Liverpool Street, also known as London Liverpool Street,[4][5] is a central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in the north-eastern corner of the City of London. It is the London terminus of the West Anglia Main Line to Cambridge, the busier Great Eastern Main Line to Norwich, local and regional commuter trains serving east London and destinations in the East of England, and the Stansted Express to London Stansted Airport.

It opened in 1874 as a replacement for the Great Eastern Railway's main London terminus, Bishopsgate station, subsequently converted into a goods yard. Liverpool Street was built as a dual-level station with an underground station opened in 1875 for the Metropolitan Railway, named Bishopsgate until 1909, when it was renamed Liverpool Street. An additional station called Bishopsgate (Low Level) existed on the main line just outside Liverpool Street from 1872 until 1916.

During the First World War, Liverpool Street was a target of one of the deadliest daylight air raids by fixed-wing aircraft; the attack killed 162 people. In the build-up to the Second World War the station served as the terminus for thousands of child refugees arriving in London as part of the Kindertransport rescue mission.

The station was modernised and rationalised between 1985 and 1992; at the same time the neighbouring Broad Street station was demolished and its lines redirected to Liverpool Street. As part of the project, the Broadgate development was constructed on the Broad Street site. Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the modified station in December 1991.

The Underground station was damaged by the 1993 Bishopsgate bombing, and during the 7 July 2005 terrorist attacks seven passengers were killed when a bomb exploded aboard an Underground train just after it had left Liverpool Street.

With over 63.6 million passenger entries and exits in 2014-15, Liverpool Street is the third busiest railway station in the United Kingdom after Waterloo and Victoria, also both in London.[6] It is one of 19 UK stations managed directly by Network Rail.[7]

It has three main exits: to Liverpool Street, after which the station is named, to Bishopsgate, and to the Broadgate development to the west of the station. The Underground station is served by the Central, Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan lines, and is in fare zone 1.

Main line station

History

A new terminus for the City (1875)

Liverpool Street station was built as the new London terminus of the Great Eastern Railway (GER) to serve its lines to Norwich and King's Lynn.[8]

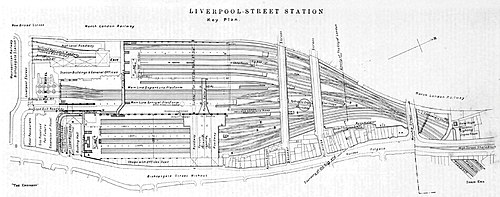

In 1862 the GER had been formed by the merger of several railway companies and had inherited Bishopsgate station as its London terminus. Bishopsgate was inadequate for the company's passenger traffic and, being located in Shoreditch, was poorly situated for the City of London commuters the company was seeking as customers; as a consequence the GER made plans for a new, more central station.[9][10] In 1865 early elements of the planned development included for a circa 1-mile long line branching from the main line east of the company's existing terminus in Shoreditch, and a new station at Liverpool Street as the main terminus, with Bishopsgate station to be used for freight traffic after the former's completion. The station at Liverpool Street was to be constructed for the use of the GER and of the East London Railway, built on two levels with the underground East London line around 37 ft (11 m) below the GER and with the GER tracks supported on brick arches. The station was planned to be around 630 by 200 ft (192 by 61 m) in area, with its main façade onto Liverpool Street and an additional entrance on Bishopsgate-Street (now called Bishopsgate and forming part of the A10). The main train shed was to be a two-span wood construction with a central void providing light and ventilation to the lower station, and the station buildings were to be in an Italianate style to the designs of the GER's architect.[9]

The line and station construction was authorised by the Great Eastern Railway (Metropolitan Station and Railways) Act 1864.[11][12] The station was built on a 10 acres (4.0 ha) site previously occupied by the Bethlem Royal Hospital, adjacent to Broad Street station, west of Bishopsgate and facing onto Liverpool Street to the south; prior to the station's construction the site was part of the general urban development of London. The development land was compulsory purchased displacing around 3,000 residents of the parish of St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate.[13][14] In order to offset the distress caused by the displacement of persons the company was required by the 1864 Act to run daily low-cost workmen's trains from the station.[11]

The station's design was by GER engineer Edward Wilson and it was built by Lucas Brothers, Builders; the station roof was designed and constructed by the Fairburn Engineering Company.[14] The overall design was approximately Gothic, built using stock bricks and bath stone dressings. The building incorporated booking offices as well as the company offices of the GER, including chairman's, board, committee, secretary and engineers' rooms. The roof was spanned by four wrought iron spans, with primarily glass glazing; two central spans of 109 ft (33 m) and outer spans of 46 and 44 ft, 730 ft (220 m) in length over the eastern main lines, and 450 ft (140 m) long over the local platforms;[15] the station had 10 platforms, two of which were used for main-line trains and the remainder for suburban trains.[16]

The station was built with a connection to the sub-surface Metropolitan Railway, with the station platform sunk below ground level; as a result there are considerable gradients leaving the station.[17] The Metropolitan Railway used the station as a terminus from 1 February 1875 until 11 July 1875; their own underground station opened on 12 July 1875.[18]

Local trains began serving the partially completed station from 2 October 1874,[10] and it was fully opened on 1 November 1875,[19] at a final cost of over £2 million.[20] The original City terminus at Bishopsgate closed to passengers and was converted for use as a goods station from 1881 until it was destroyed by fire in 1964.[21]

The Great Eastern Hotel adjoining the new Liverpool Street station opened in 1884.[22]

Expansion of the station (1895)

Although initially viewed as an expensive white elephant,[23] within 10 years the station was working at capacity (circa 600 trains per day) and the GER was acquiring land to the east of the station for expansion.[20] An Act of Parliament was obtained in 1888 and work started in 1890 on the eastward expansion of Liverpool Street by the addition of eight new tracks and platforms.[19][24]

The main station was extended approximately 230 ft (70 m) eastwards, additional shops and offices were constructed east of the new train shed up to the boundary formed by Bishopsgate-Street Without.[25]

The new station's roof consisted of four longitudinally aligned arched roofs, the outer roofs were approximately 51 ft (16 m) wide, and the two inner roofs approximately 42 ft (13 m) wide in width. The roofs were set on 13 sets of piers space 30 ft (9.1 m) apart,[26][27] plus an 87 ft (27 m) roof at right angles over the "circulating area" at the buffer stop end of the station.[28]

At the north end of the station roof a parcels office was constructed over the tracks,[29] supported on cast iron columns carrying wrought iron box and plate girders longitudinally and crosswise, on which were carried rolled steel joists;[30][31] The elevated main parcel offices and side buildings required extensive and substantial foundation work, taken down to 30 ft below ground level to a clay substratum; the building was supported on multiple iron columns - the largest of which were 3 ft diameter, connected in pairs and cross strutted.[36]

For foundations and inner walls stock bricks were used, for the base of the outer walls of the parcel office Staffordshire blue bricks were used followed by Leicester bricks, and for facing other walls of the new station Ruabon bricks and Suffock bricks were used.[37] The four train shed roofs were carried out by Messrs. Handyside and Co., supervised by a Mr. Sherlock, the resident engineer; all the foundations, earthwork and brickwork were carried out by Mowlem & Co;[38] the ironwork of the parcels office was carried out by Head Wrightson, approximately 620 long tons (630 t) of cast iron was used for columns, stanchions and accessories, and 1,230 long tons (1,250 t) of wrought iron for box and plate girders.[39]

Electric power (for lighting) was supplied from an engine house located north of the station.[38] Additional civil works included three iron bridges carrying road traffic over the railway on Skinner, Primrose and Worship Streets;[40] the bridge ironwork was supplied and erected by the Horseley Company.[41][42][43] John Wilson was chief engineer, with W. N. Ashbee as architect.[19]

The Metropolitan Railway connection was closed in 1904.[8] In 1912 the Central London Railway was extended to the station.[19]

First World War and memorials (1917-1922)

During the First World War, on 13 June 1917, a daylight air raid on London with 20 Gotha G.IV bombers took place, the first such attack on the capital. The raid struck a number of sites including Liverpool Street station. Seven tons of explosive were dropped which killed 162 people and injured 432.[44][45] Three bombs hit the station, of which two exploded, having fallen through the train shed roof, near to two trains, causing multiple fatalities.[46] This was the deadliest single raid on Britain during the war.[47]

Over 1,000 GER employees who died during the war were honoured on a large marble memorial installed in the booking hall, unveiled on 22 June 1922 by Sir Henry Wilson. On his return home from the unveiling ceremony, Wilson was assassinated by two Irish Republican Army members. He was commemorated by a memorial plaque adjoining the GER monument, unveiled one month after his death.[48][48][49][50]

Also commemorated in the station is mariner Charles Fryatt who was executed in 1916 for ramming a German U-boat with the GER steamer SS Brussels.[51][52]

The GER memorial was relocated during the modification of the station and now incorporates both the Wilson and Fryatt memorials, as well as a number of railway related architectural elements salvaged from demolished buildings.[52]

Productivity experiments (1920s)

In the early 1900s successful applications of electric traction suggested that electrification could be viable on the heavily used local services out of London termini, and after the First World War the GER required increased capacity out of Liverpool Street. However, the company was not able to undertake the cost of electrification; high powered, high tractive effort steam locomotives such as the GER Class A55 were a possible solution providing high acceleration usually associated with electric traction, but were rejected due to the high track loadings. An alternative optimisation scheme was followed using a combination of automatic signalling and modifications to the layout at Liverpool Street. The station introduced coaling, watering, and other maintenance facilities directly at the station, as well as separate engine bays and a modified track and station layout in an effort to reduce turnaround times and increase productivity.[53][54] Services began on 2 July 1920 with trains to Chingford and Enfield running every 10 minutes. The cost of the modifications was £80,000 compared to an estimated £3 million for electrification.[55]

Second World War (1939-1945)

Thousands of Jewish refugee children arrived at Liverpool Street in the late 1930s as part of the Kindertransport rescue mission in the run up to the Second World War. In September 2003 the Für Das Kind Kindertransport Memorial sculpture by artist Flor Kent, who conceived the project, was installed at the station. It consisted of a specialised glass case with original objects and a bronze sculpture of a girl, a direct descendant of a child rescued by Nicholas Winton, who unveiled the work.[56] The objects included in the sculpture began to suffer deterioration due to weather, and in 2006 a replacement bronze memorial, named Kindertransport – The Arrival, by Frank Meisler, depicting a group of children and a railway track, was installed at the main entrance on Liverpool Street.[57] The statue of the child from the Kent memorial was re-erected separately on the concourse in 2011.[58]

During the Second World War the station's structure sustained damage, particularly the Gothic tower at the main entrance on Liverpool Street and its glass roof, which was damaged by a bomb that landed nearby on Bishopsgate.[citation needed]

Post-war electrification (1946-60)

After the formation of the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933, work to electrify the line from Liverpool Street to Shenfield began in association with the London and North Eastern Railway company.[59]

Progress had been halted by the Second World War but was given a high priority after the end of hostilities and the line between Liverpool Street and Stratford was electrified from 3 December 1946, and the full electrification of the Shenfield line at 1500V DC was completed by late 1949.[59] At the same time electrification of London Underground services in Essex and northeast and east London led to the withdrawal of some services from Liverpool Street, being replaced with LU operations. Electrification continued with the line to Chingford electrified by November 1960.[60]

Redevelopment and Broadgate (1973-1991)

In 1973 the British Railways Board, London Transport Executive, Greater London Council and the Department of the Environment produced a report examining the modernisation of transport facilities in Greater London. The report recommended that the reconstruction of Liverpool Street and Broad Street stations should be given high priority, also recommending financing this through development of property on the site.[61] Liverpool Street had a number of design and access issues, many of which derived from the 1890 extension, which had effectively created two stations on one site, with two concourses linked by walkways, multiple booking halls, and inefficient traffic flows within the station. Additionally the rail infrastructure presented limitations: only seven of the platforms could stable 12-carriage trains, and the station track exit layout was a bottleneck.[62] In 1975 British Railways announced plans to demolish and redevelop both stations.[63] The proposed demolition met considerable public opposition and prompted a campaign led by the Poet Laureate Sir John Betjeman, and as a result a public inquiry took place from November 1976 to February 1977.[64]

The inquiry resulted in the requirement to retain and incorporate the western (1875) train shed roof into the new development; the station end roof was repaired and reinforced between 1982 and 1984, followed by repairs to the main roof completed in 1987.[65] Initial plans included the broadening of the exit of the stations by two tracks to make eight tracks, with 22 platforms in a layout similar to that of Waterloo station; the combined Broad Street and Liverpool Street station was to be at the level of the original Liverpool Street station, with relatively low-rise office developments.[66] Poor utilisation of land value caused the development to be reassessed in 1983/4, when it was decided to retain the existing six-road exit throat and 18-platform layout, in combination with resignalling; this resulted in a station confined to the Liverpool Street site, with ground space released for development.[67] In 1985 British Railways signed an agreement with developers Rosehaugh Stanhope and work on the office development, known as Broadgate, began.[68]

Railway work included the construction of a chord from the North London Line to the Cambridge main line, allowing trains which had previously used Broad Street to terminate at Liverpool Street.[69] The station was reconstructed with a single concourse at the head of the station platforms, and entrances from Bishopsgate and Liverpool Street, as well as a bus interchange in the south west corner.[70] The Broadgate development was constructed between 1985 and 1991, with 330,000 m2 (3,600,000 sq ft) of office space on the site of the former Broad Street station and above the Liverpool Street tracks.[71] Proceeds from the Broadgate development were used to help fund the station modernisation.[72]

In 1988 The Arcade above Liverpool Street underground station on the corner of Liverpool Street and Old Broad Street was due to be completely demolished by London Regional Transport and MEPC, who wanted to develop the site into a five-storey block of offices and shops. More than 6,000 people signed a petition to "Save the Arcade", and the historic Victorian building still stands today. The campaign against the development was led by Graham Horwood, who owned an employment agency within the Arcade at the time.[73]

In 1989 the first visual display unit-controlled signalling operation on British Rail (known as an Integrated Electronic Control Centre) became operational at Liverpool Street.[74]

The redeveloped Liverpool Street was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 5 December 1991.[75] At that time a giant departures board was installed above the concourse; it was one of the last remaining mechanical 'flapper' display boards at a British railway station until its replacement in 2007.

Recent history (1992–present)

In 1992, an additional entrance was constructed on the east side of Bishopsgate with a subway under the road.[citation needed] The station was "twinned" with Amsterdam Centraal railway station in 1993, with a plaque marking this close to the entrance to the Underground station.[citation needed]

The station was badly damaged by the 24 April 1993 Bishopsgate bombing and was temporarily closed as a result.[76][77] About £250,000 of damage was caused to the station, primarily to the glass roof. The station re-opened on 26 April 1993.[78][79]

In 2007 the 'flapper' departures and arrivals board was removed and replaced by electronic boards.[80]

In 2013, during excavation work for the Crossrail project, a 2 acres (0.81 ha) mass burial ground dating from the 17th century was uncovered a few feet beneath the surface at Liverpool Street. It contained the remains of several hundred people and it is thought that the interments were of a wide variety of people, including plague victims, prisoners and unclaimed corpses.[81] A 16th century gold coin, thought to have been used as a sequin or pendant, was also found.[82] In early 2015 full scale excavation of the burials began, then estimated at around 3,000 interments.[83]

In advance of the opening of Crossrail from 2017/18, precursor company TfL Rail took over from Abellio Greater Anglia the operating of the Liverpool Street-Shenfield stopping "metro" service from May 2015. At the same time, services on the Lea Valley Lines out of Liverpool Street to Enfield Town, Cheshunt (via Seven Sisters) and Chingford transferred to London Overground.

Services

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) |

Trains departing Liverpool Street main-line station serve destinations across the east of England, including Norwich, Southminster, Ipswich, Clacton-on-Sea, Colchester, Chelmsford, Southend Victoria, Cambridge, Harlow Town, Hertford East, and many suburban stations in north-east London, Essex and Hertfordshire. It is one of the busiest commuter stations in London. A small number of daily express trains to Harwich International provide connection with the Dutchflyer ferry to Hoek van Holland. Stansted Express trains provide a link to Stansted Airport and Southend Victoria-bound services stop at Southend Airport.

Most passenger services on the Great Eastern Main Line are operated by Abellio Greater Anglia, but since May 2015 the Shenfield "metro" route to Shenfield is controlled by TfL Rail and the Lea Valley Lines to Enfield Town, Cheshunt (via Seven Sisters) and Chingford are operated by London Overground; a small number of late evening services operated by c2c run to Barking and Grays.[84]

The typical off-peak weekday service pattern from Liverpool Street is:

Underground station

| Liverpool Street | |

|---|---|

Entrance from the main concourse at Liverpool Street | |

| Location | Liverpool Street |

| Local authority | City of London |

| Managed by | London Underground |

| Number of platforms | 4 |

| Accessible | Yes(Sub-surface eastbound platform only)[85] |

| Fare zone | 1 |

| Cycle parking | Yes (platform 10 & external)[86] |

| London Underground annual entry and exit | |

| 2019 | |

| 2020 | |

| 2021 | |

| 2022 | |

| 2023 | |

| Key dates | |

| 1 February 1875 | Opened (using main line) |

| 12 July 1875 | Opened as Bishopsgate |

| 1 November 1909 | Renamed Liverpool Street |

| 28 July 1912 | Central line opened (terminus) |

| 4 December 1946 | Central line extended (through) |

| Other information | |

| External links | |

Liverpool Street Underground station is served by the Central, Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan lines and is the sixth busiest station on the London Underground network.

Only the eastbound/clockwise (Template:LUL stations/Barking) platform of the Circle line is currently wheelchair-accessible.

History

From 1874 to 1875 the Metropolitan Railway used the Liverpool Street main-line station as a terminus; on 12 July 1875 the company opened their own station, initially called Bishopsgate.[19] The station was renamed Liverpool Street in 1909.[19]

Subsurface platforms 1 and 2 were opened in 1875. A disused west-facing bay platform 3 was used by terminating Metropolitan and occasional District line trains running via Template:LUL stations[when?] is still extant.[citation needed]

In 1912 Liverpool Street became the new terminus of the Central London Railway after the completion of an extension project from Bank.[92] The deep-level Central line platforms 4 and 5 opened on 28 July 1912 as the eastern terminus of the Central London Railway.[citation needed]

On 4 December 1946 the passenger line was extended eastwards as part of the war-delayed London Passenger Transport Board's New Works Programme.[18][93] An Underground ticket hall was added in 1951.[92]

During the 7 July 2005 terrorist attacks on London, a bomb was exploded aboard an Underground train that had departed Liverpool Street toward Aldgate. Seven passengers were killed.[94]

London Post Office Railway station

The Liverpool Street Post Office Railway station is a disused station that was operated by Royal Mail on the London Post Office Railway system.

The station is between Mount Pleasant Mail Centre and Whitechapel Eastern District Post Office, and is situated at the south end of Liverpool Street under the Great Eastern Hotel. It opened in December 1927;[95] lifts on either side of the station as well as chutes enabled the transfer of mail to and from the main station.[24] Two 315-foot (96 m) parcel and letter bag conveyors were connected to platforms 10 and 11 (currently used by Abellio Greater Anglia); postal traffic reached 10,000 bags daily in the 1930s, with 690 Post Office services calling.[95] The system was discontinued in 2003.

In 2014, a team from the University of Cambridge began conducting a study in a short, double track section of unused tunnel near the platforms where a newly built tunnel for Crossrail is situated almost two metres beneath. The study is to establish how the original cast-iron lining sections, which are similar to those used for many miles of railway under London, resist possible deformation and soil movement caused by the developments.[96]

Future developments

From 2019, Liverpool Street will be fully served by Crossrail services westward towards London Heathrow Airport and Reading via central London, and eastward to Abbey Wood and Shenfield.[97]

A new ticket hall with step-free access will be built next to the Broadgate development, with a pedestrian link via the new platforms to the ticket hall of Moorgate, providing direct access to London Underground's Northern line and the Northern City Line.

The six off-peak trains per hour that currently form the stopping "metro" service between Liverpool Street and Shenfield will be doubled and diverted into the Crossrail tunnel between Liverpool Street and Stratford via Whitechapel. A limited main-line "metro" service will be retained and will continue to run into Liverpool Street's main platforms 15 to 18.

A temporary shaft in Finsbury Circus allows for construction of the platforms; this will be removed once the station is complete.

Bus station

There is a bus station to the west of the station near the Underground and Broadgate entrances, offering services to various parts of London.

In popular culture

Liverpool Street is one of the four railway stations on the UK version of Monopoly, introduced in the early 20th century.

The station has been used several times as the site of fictionalised terrorist attacks: in Andy McNab's novel Dark Winter the station is the target of an attack; in London Under Attack, a 2004 Panorama docu-drama portrayal of a terrorist attack on London using chlorine gas;[98] and the drama Dirty War, (2004) portrayed a suicide terrorist attack using a "dirty bomb" near the Underground station. The station has also been used as a backdrop for a number of other film and television productions, including espionage films Stormbreaker (2006) and Mission Impossible (1996), and crime drama The Shadow Line (2011), as well as the site for staged flash mobs in the film St. Trinian's 2: The Legend of Fritton's Gold (2009), and for a T-Mobile advert.

H. G. Wells' 1898 novel The War of The Worlds included a chaotic rush to board trains at Liverpool Street as the Martian machines overran military defences in the West End, and described the crushing of people under the wheels of the steam engines.

The station is the subject of the poem "Liverpool Street Station" by John Davidson.[99]

THROUGH crystal roofs the sunlight fell,

And pencilled beams the gloss renewed

On iron rafters balanced well

On iron struts ; though dimly hued.

With smoke o'erlaid, with dust endued.

The walls and beams like beryl shone ;

And dappled light the platforms strewed

With yellow foliage of the dawn

That withered by the porch of day's divan.— John Davidson, Fleet Street and Other Poems (Extract).[100]

A licensed bar on the subsurface tube platforms (which existed until 1978, now replaced by the A Piece Of Cake cafe)[101] is referred to in Iris Murdoch's 1975 novel A Word Child

Gallery

-

Locomotive yard at Liverpool Street, 1948

-

Trains at Liverpool Street, c. 1980

-

Liverpool Street station interior, 1984

-

Reconstruction of the station, 1989

-

Entrance to the station from Bishopsgate

-

The Great Eastern Hotel, adjacent to the station

-

Memorial to the men of East Anglia who died in World War I

-

Kindertransport memorial at the Liverpool Street entrance

-

The station roof, with a Class 90 locomotive in the foreground

-

A view over the station from Exchange Square

-

The main departures board on the station concourse, 2014

-

Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan line platforms

-

Roundel on a Central line platform

-

Sign for National Rail, TfL Rail and London Overground on a subsurface lines platform

-

Modified sign at Liverpool Street pointing to London Overground

See also

References

- ^ "London and South East" (PDF). National Rail. September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2009.

- ^ "Out of Station Interchanges" (XLSX). Transport for London. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Estimates of station usage". Rail statistics. Office of Rail Regulation. Please note: Some methodology may vary year on year.

- ^ "Stations Run by Network Rail". Network Rail. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ^ "Station facilities for London Liverpool Street". National Rail Enquiries. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Pigott, Nick, ed. (June 2012). "Waterloo still London's busiest station". The Railway Magazine. 158 (1334). Horncastle, Lincs: Mortons Media Group: 6.

- ^ "Commercial information". Our Stations. London: Network Rail. April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ a b "History of Liverpool Street station". Network Rail. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ a b The Engineer, 27 October 1865 p.266, col.1

- ^ a b "Liverpool Street Station, London". Network Rail Virtual Archive. Network Rail. July 2012. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Kellett 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Rickards, George Kettilby (1864). The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 27 & 28 Victoria 1864. pp. 954–956.

... a Railway from Liverpool Street in the City of London to Commercial Street near the Bishopsgate Station of the Company, and a Railway therefrom to their Main Line at Tap Street, [...] would be of great public Advantage, and the Company are willing, if authorized by Parliament, to make such Railways; that it is expedient that the Company should be authorized to purchase certain Lands and Buildings in the City of London and in the Parish of Saint Botolph, Bishopsgate, and to stop up all Streets and Highways within the said Area, and to appropriate the Site of such Area lo the Purposes of a Railway Station, and also to purchase certain Lands and Buildings in the Neighbourhood of their Bishopsgate Station for the Enlargement thereof.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. 1:5280, 1851; 1:1056, 1875

- ^ a b Architectural mini-guide, 1.The Train Shed

- ^ The Engineer, 11 June 1875 p.403, cols.1 & 2

- ^ Campion 1987, pp. 97–98.

- ^ "Liverpool Street Station, London". www.transportheritage.com. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ a b Rose, Douglas (December 2007) [1980]. The London Underground: A Diagrammatic History (8th ed.). Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-315-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 2001, p. 177.

- ^ a b Ackworth, W.M. (1900). The Railways of England (5th. ed.). London: John Murray. pp. 410–411.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 176.

- ^ Architectural mini-guide, 4. The Great Eastern Hotel

- ^ Kellett 2007, p. 64.

- ^ a b Campion 1987, p. 98.

- ^ The Engineer, 8 June 1894 p.495, col.2; Plan and cross section, p.494

- ^ The Engineer, 8 June 1894 Plan and cross section, p.494

- ^ The Engineer, 15 June 1894 p.515 col.2

- ^ The Engineer, 15 June 1894 p.515, col.2

- ^ The Engineer, 15 June 1894 p.515 col.1

- ^ The Engineer, 19 October 1894 p.336

- ^ The Engineer, 12 October 1894 p.313 col.1

- ^ The Engineer, 12 October 1894 p.313 cols.1-2

- ^ The Engineer, 12 October 1894 p.313, col.3

- ^ The Engineer, 12 October 1894 p.314 cols.1

- ^ The Engineer, 12 October 1894 p.314, cols.1-3; p.315, Figs. 2,3; p.314, Figs.14-19

- ^ The building's column foundations were taken down 30 ft (9.1 m) through levels of made ground, the original surface, and then gravel and a layer of yellow clay to blue clay.[32] The side buildings had foundations of a 10 ft (3.0 m) square, 2 ft (0.61 m) thick concrete bed, supporting brick footings and then a 5 ft (1.5 m) square, 2 ft (0.61 m) thick bedstone,[33] which supported 18 to 24 in (460 to 610 mm) wide 1.25 in (32 mm) thick main columns.[34] The main central parcels building was built on foundations of a 21 by 19 ft (6.4 by 5.8 m) bed of concrete 3 ft (0.91 m) thick supporting brick footings and then a 12 by 10 ft (3.7 by 3.0 m) square, 1 ft 9 in (0.53 m) thick bedstone, supporting twinned 3 ft diameter cross-strutted iron columns 3 in (76 mm) thick up to the floor level support girders.[35]

- ^ The Engineer, 12 October 1894 p.314, col.2

- ^ a b The Engineer, 29 June 1894 p.560 col.2

- ^ The Engineer, 19 October 1894 p.337, cols.2 & 3

- ^ The Engineer, 15 June 1894 p.515 col.1

- ^ The Engineer, 24 April 1896 p.414, col.3

- ^ The Engineer, 21 August 1896 p.188, col.2

- ^ The Engineer, 26 February 1897 p.215, col.3

- ^ Murphy, Justin D. (2005). Military Aircraft, Origins to 1918: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. p. 66.

- ^ Sokolski, Henry D. (2004). Getting MAD: Nuclear Mutual Assured Destruction, Its Origins and Practice (PDF). pp. 19–20. ISBN 1584871725.

- ^ Hanson, Neil (2008). First Blitz. pp. 126–127.

- ^ http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/airraids.htm

- ^ a b "Sir H. Wilson murdered. Shot on his doorstep. Two Irishmen captured. Running fight in London". The Times. London. 23 June 1922. p. 10.

- ^ Winn, Christopher (2007). I Never Knew That About London. Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-191857-6.

- ^ "Lest We Forget ( The Great Eastern Railway Magazine June 1922)". What the papers said - excerpts from the railway press from the 1840s to the 1990s. Institute of Railway Studies and Transport History. p. 131. Archived from the original on 29 September 2002.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The case of Captain Fryatt". Institute of Railway Studies and Transport History - Railway readings. June 2003. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 24 December 2013 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Architectural mini-guide, 3.The War memorial

- ^ Duffy 2003, 6.1. The Great Eastern Railway and the Liverpool Street Station experiment, pp.73-5.

- ^ "GER The Last Word in Steam Operated Suburban Train Services". Railway Gazette. 1 October 1920.

- ^ Stratton, Michael; Trinder, Barrie (2000). Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology. E & FN Spon. p. 163. ISBN 0419246800.

- ^ Rothenberg, Ruth (19 September 2003). "Kindertransport statue unveiled". The Jewish Chronicle. London. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Frank Meisler, personal website. Retrieved 23 May 2011

- ^ Berthoud, Peter (29 May 2011), "Monumental Children Return to Meet Their Saviour at Liverpool St", www.peterberthoud.co.uk (blog)

- ^ a b Duffy 2003, p. 271.

- ^ Powell, W.R., ed. (1966). "14. Metropolitan Essex since 1919 - Suburban growth". A History of the County of Essex. Vol. 5. pp. 47–63.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Campion 1987, p. 99.

- ^ Campion 1987, pp.98-99, sections 6, 9-12.

- ^ "Window on the World". The Illustrated London News. 263 (2): 22.

- ^ Thorne 1978, p. 7.

- ^ Campion 1987, p. 105-106.

- ^ Campion 1987, p.102 sections 20-23.

- ^ Campion 1987, pp.106-107 section 37-40.

- ^ Campion 1987, pp.106-107 section 40.

- ^ Campion 1987, p.107 section 43.

- ^ Campion 1987, p.109 Fig.4.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Anthony (2006). London: An Architectural History. pp. 204–5.

- ^ Campion 1987, pp.97.

- ^ http://www.taichi-horwood.com/uncategorized/liverpool-street-arcade-still-standing/

- ^ Beady, F.F.; Bartlett, P.J.N. (25–28 September 1989). New generation signalling control centre. International Conference on Main Line Railway Electrification. Institution of Electrical Engineers. pp. 317–321.

- ^ "Main line Masterpiece". The Times. No. 64196. London. 6 December 1991. pp. 4, 19.

- ^ "The Bishopsgate Bomb: One bomb: pounds 1bn devastation: Man dead after City blast - Two more explosions late last night". The Independent. 25 April 1993.

- ^ Webster, Philip; Prynn, Jonathan; Dettmner, Jamie; Ford, Richard (26 April 1993). "Taxpayers foot IRA bomb bill". The Times. No. 64628. p.1, col.1.

- ^ "Liverpool St. reopens". The Times. No. 64368. 16 April 1993. p. 2.

- ^ Bennett, Neil (26 April 1993). "Shattered City defies the bombers". The Times. No. 64628. p. 40.

- ^ "Last of the Flapper Boards depart Liverpool St" (Press release). Network Rail. 7 November 2007.

- ^ Blunden, Mark (8 August 2013). "Crossrail dig unearths ancient burial site under Liverpool Street station". London Evening Standard.

- ^ Smith, Hayden (8 August 2013). "Crossrail project unearths prehistoric workshop and 16th-century burial ground". Metro.

- ^ "Plague pit with 3,000 skeletons uncovered at new Liverpool Street station ticket hall". The Daily Telegraph. 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Changes to late evening and Liverpool Street services". c2c. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007.

- ^ "Step free Tube Guide" (PDF). Transport for London. April 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2021.

- ^ http://www.tfl.gov.uk/tube/stop/940GZZLULVT/liverpool-street-underground-station

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2019. Transport for London. 23 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2020. Transport for London. 16 April 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2021. Transport for London. 12 July 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2022. Transport for London. 4 October 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2023. Transport for London. 8 August 2024. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Liverpool Street underground station, Bishopgate underground station (502060)". Research records (formerly PastScape).

- ^ Day, John R.; Reed, John (2008) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground (10th ed.). Harrow: Capital Transport. pp. 146–7. ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "London Attacks: Liverpool Street". BBC News Channel. BBC News.

- ^ a b Jackson 1972, p. 111.

- ^ "Bridging the Knowledge Gap in London's 'Secret Tube'". Cambridge Centre for Smart Infrastructure & Construction. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ http://www.crossrail.co.uk/route/stations/liverpool-street/

- ^ "London under attack". BBC News Online. London. 6 May 2004.

- ^ Dow, Andrew (ed.). Dow's Dictionary of Railway Quotations. 354.2, p.108.

- ^ Davidson, John (1909). Fleet Street and Other Poems. pp. 43–58.

- ^ Halliday, Stephen. Underground to Everywhere: London's Underground Railway in the Life of the Capital. p. 88.

Sources

- "New station for the Great Eastern" (PDF). The Engineer. 20: 266. 27 October 1865.

- "Great Eastern Railway Company's new station at Liverpool Street" (PDF). The Engineer. 39: 403, illus. p. 400. 11 June 1875.

- "The Enlargement of Liverpool-Street Station, Great Eastern Railway". The Engineer.

- "No.I" (PDF). 77. 8 June 1894: 493–495.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "No.II" (PDF). 77. 15 June 1894: 515–516.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "No.III" (PDF). 77. 29 June 1894: 559–560.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "No.IV" (PDF). 78. 12 October 1894: 313–315.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "No.V" (PDF). 78. 19 October 1894: 335–337.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Bridge at Worship Street" (PDF). 81. 24 April 1896: 414–416.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Extension of Primrose Street bridge" (PDF). 82. 21 August 1896: 186–188, illus. p. 183.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Extension of Skinner Street bridge" (PDF). 83. 26 February 1897: 214–215, illus. pp. 222–223.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- "No.I" (PDF). 77. 8 June 1894: 493–495.

- Campion, R.J. (1987). The Redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station. Thomas Telford. ISBN 9780727713377.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Duffy, Michael C. (2003). Electric Railways 1880-1990. The Institute of Engineering and Technology. ISBN 0852968051.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jackson, Alan A. (1972) [1969]. London's Termini. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-330-02747-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kellett, John R. (2007) [1969]. The Impact of Railways on Victorian Cities (digital reprint). p. 52.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Denis (2001). London and the Thames Valley. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0727728768.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stevenson, David (2004). 1914-1918 The History of the First World War. Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9208-5.

- "Architectural mini guide - Liverpool Street" (PDF). Network Rail. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Thorne, Robert (1978). Liverpool Street Station. Academy Editions.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Derbyshire, Nick (1991). Liverpool Street : A station for the 21st Century. Granta. ISBN 0906782864.

External links

- Station information on Liverpool Street station from Network Rail

- Liverpool Street 1977 photos from 1977

- London Landscape TV episode (7 mins) about Liverpool Street station

- Alternative view of the Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan line platforms

- Use dmy dates from August 2012

- Rail transport stations in London fare zone 1

- DfT Category A stations

- Central line stations

- Circle line stations

- Hammersmith & City line stations

- Metropolitan line stations

- Tube stations in the City of London

- Former Metropolitan Railway stations

- Railway stations opened in 1875

- Former Central London Railway stations

- Railway stations opened in 1912

- Railway stations in the City of London

- Railway termini in London

- Network Rail managed stations

- Former Great Eastern Railway stations

- Railway stations opened in 1874

- Railway stations served by c2c

- Greater Anglia franchise railway stations

- Railway stations served by Crossrail

- London Monopoly places

- 1874 establishments in England