P. V. Narasimha Rao

P. V. Narasimha Rao | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

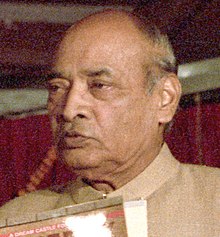

Prime Minister Rao in 1992 | |||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of India | |||||||||||||

| In office 21 June 1991 – 16 May 1996 | |||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Chandra Shekhar | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Atal Bihari Vajpayee | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Union Minister of Defence | |||||||||||||

| In office 6 March 1993 – 16 May 1996 | |||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | himself | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Shankarrao Chavan | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Pramod Mahajan | ||||||||||||

| In office 31 December 1984 – 25 September 1985 | |||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Rajiv Gandhi | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Rajiv Gandhi | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Shankarrao Chavan | ||||||||||||

| 11th Union Minister of External Affairs | |||||||||||||

| In office 31 March 1992 – 18 January 1994 | |||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | himself | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Madhavsinh Solanki | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Dinesh Singh | ||||||||||||

| In office 25 June 1988 – 2 December 1989 | |||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Rajiv Gandhi | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Rajiv Gandhi | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | V. P. Singh | ||||||||||||

| In office 14 January 1980 – 19 July 1984 | |||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Indira Gandhi | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Shyam Nandan Prasad Mishra | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Indira Gandhi | ||||||||||||

| 18th Union Minister of Home Affairs | |||||||||||||

| In office 12 March 1986 – 12 May 1986 | |||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Rajiv Gandhi | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Shankarrao Chavan | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Sardar Buta Singh | ||||||||||||

| In office 19 July 1984 – 31 December 1984 | |||||||||||||

| Prime Minister |

| ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Prakash Chandra Sethi | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Shankarrao Chavan | ||||||||||||

| 4th Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh | |||||||||||||

| In office 30 September 1971 – 10 January 1973 | |||||||||||||

| Governor | Khandubhai Kasanji Desai | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Kasu Brahmananda Reddy | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | President's rule | ||||||||||||

| Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | |||||||||||||

| In office 15 May 1996 – 4 December 1997 | |||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Gopinath Gajapati | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jayanti Patnaik | ||||||||||||

| Constituency | Brahmapur, Odisha | ||||||||||||

| In office 20 June 1991 – 10 May 1996 | |||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Gangula Prathapa Reddy | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Bhuma Nagi Reddy | ||||||||||||

| Constituency | Nandyal, Andhra Pradesh | ||||||||||||

| In office 31 December 1984 – 13 March 1991 | |||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Barve Jatiram Chitaram | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Tejsinghrao Bhosle | ||||||||||||

| Constituency | Ramtek, Maharashtra | ||||||||||||

| In office 23 March 1977 – 31 December 1984 | |||||||||||||

| Preceded by | constituency established | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Chendupatla Janga Reddy | ||||||||||||

| Constituency | Hanamkonda, Andhra Pradesh | ||||||||||||

| Member of Andhra Pradesh Legislative Assembly | |||||||||||||

| In office 1957–1977 | |||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Gulukota Sriramulu | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Chandrupatla Narayana Reddy | ||||||||||||

| Constituency | Manthani | ||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||

| Born | 28 June 1921 Laknepalli, Hyderabad State, British India (present-day Telangana, India) | ||||||||||||

| Died | 23 December 2004 (aged 83) New Delhi, India | ||||||||||||

| Monuments | Gyan Bhumi | ||||||||||||

| Political party | Indian National Congress | ||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Satyamma

(m. 1931; died 1970) | ||||||||||||

| Children | 8, including P. V. Rajeshwar and Surabhi Vani Devi | ||||||||||||

| Alma mater | |||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||

| Awards | Bharat Ratna (2024) | ||||||||||||

Pamulaparthi Venkata Narasimha Rao (28 June 1921 – 23 December 2004), popularly known as P. V. Narasimha Rao, was an Indian lawyer, statesman and politician from the Indian National Congress Party who served as the Prime Minister of India from 1991 to 1996. He was the first person from South India and second person from a non-Hindi speaking background to be the prime minister. He is especially known for introducing various liberal reforms to India's economy by recruiting Manmohan Singh as the finance minister to rescue the country from going towards bankruptcy during the economic crisis of 1991.[1][2][3] Future prime ministers continued the economic reform policies pioneered by Rao's government.[4][5]

Prior to his premiership, he served as the Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, and later also held high order portfolios of the union government, such as Defence, Home Affairs and External Affairs. In 1991 Indian general election, the Indian National Congress led by him won 244 seats and thereafter he along with external support from other parties formed a minority government with him being the prime minister.

Rao was also referred to as Chanakya for his ability to steer economic and political legislation through the parliament at a time when he headed a minority government.[6][7][8] He remains a controversial figure in his party due to alleged role during and after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 and also for having a bitter relation with the Nehru–Gandhi family,[9][10][11] and he was sidelined later by his own party,[12] Nevertheless, retrospective evaluations have been kinder, positioning him as one of the best prime ministers of India in various polls and analyses.[13][14][15][16][17][18] In 2024, he was posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award by the Government of India.[19]

Early life

[edit]P. V. Narasimha Rao was born on 28 June 1921 in a Telugu Niyogi Brahmin[20] family in the village of Laknepalli village of Narsampet mandal, Warangal district of present-day Telangana (then part of Hyderabad State).[20][21][22] His father Sitarama Rao and mother Rukma Bai hailed from agrarian families.[23] Later, he was adopted by Pamulaparthi Ranga Rao and Rukminamma and brought to Vangara, a village in Bheemadevarpalle mandal of present-day Hanamkonda district in Telangana when he was three years old.[22][21][24] Popularly known as P. V., he completed part of his primary education in Katkuru village of Bheemdevarapalli mandal in Hanamkonda district by staying in his relative Gabbeta Radhakishan Rao's house and studying for his bachelor's degree in the Arts college at the Osmania University. He was part of Vande Mataram movement in the late 1930s in the Hyderabad State. He later went on to Hislop College, now under Nagpur University, where he completed a master's degree in law.[25] He completed his law from Fergusson College in Pune of the University of Bombay (now Mumbai).[21]

Along with his distant cousin Pamulaparthi Sadasiva Rao, Ch. Raja Narendra and Devulapalli Damodar Rao, P. V. edited a Telugu weekly magazine called Kakatiya Patrika in the 1940s.[26] Both P. V. and Sadasiva Rao contributed articles under the pen-name Jaya-Vijaya.[26][27] He served as the Chairman of the Telugu Academy in Andhra Pradesh from 1968 to 1974.[21]

He had wide interests in a variety of subjects (other than politics) such as literature and computer software (including computer programming).[28] He spoke 17 languages.[29][30]

Rao died in 2004 of a heart attack in New Delhi. He was cremated in Hyderabad.[31]

Political career

[edit]

Rao was an active freedom fighter during the Indian Independence movement[32] and joined full-time politics after independence as a member of the Indian National Congress.[25] He served as an elected representative for Andhra Pradesh State Assembly from 1957 to 1977.[21] He served in various ministerial positions in Andhra government from 1962 to 1973.[21] He became the Chief minister of Andhra Pradesh in 1971 and implemented land reforms and land ceiling acts strictly.[21] He secured reservation for lower castes in politics during his tenure.[21] President's rule had to be imposed to counter the Jai Andhra movement during his tenure.[33]

He supported Indira Gandhi in formation of New Congress party in 1969 by splitting the Indian National Congress.[21] This was later regrouped as Congress (I) party in 1978.[21] He served as Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha from Andhra Pradesh.[21] He rose to national prominence for handling several diverse portfolios, most significantly Home, Defence and Foreign Affairs, in the cabinets of both Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi.[25] He served as Foreign minister from 1980 to 1984 and then from 1988 to 1989.[21] In fact, it is speculated that he was in the running for the post of India's President along with Zail Singh in 1982.[34][better source needed]

Rao very nearly retired from politics in 1991. He was Indian National Congress President from 29 May' 1991– Sept.1996. It was the assassination of the Congress President Rajiv Gandhi that persuaded him to make a comeback.[35] As the Congress had won the largest number of seats in the 1991 elections, he had an opportunity to head the minority government as Prime Minister. He was the first person outside the Nehru–Gandhi family to serve as Prime Minister for five continuous years, the first to hail from the State of Telangana,[a] and also the first from Southern India.[4][36] Since Rao had not contested the general elections, he then participated in a by-election in Nandyal to join the parliament. Rao won from Nandyal with a victory margin of a record 5 lakh (500,000) votes and his win was recorded in the Guinness Book Of World Records; later on, in 1996, he was MP from Berhampur, Ganjam District, Odisha.[37][38] His cabinet included Sharad Pawar, himself a strong contender for the Prime Minister's post, as Defence Minister. He also broke a convention by appointing a non-political economist and future prime minister, Manmohan Singh as his Finance Minister.[39][40] He also appointed Subramanian Swamy, an opposition party (Janata Party) member as the Chairman of the Commission on Labour Standards and International Trade. This has been the only instance that an opposition party member was given a Cabinet rank post by the ruling party. He also sent opposition leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee, to represent India in a UN meeting at Geneva.[41]

Narasimha Rao fought and won elections from different parts of India such as Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Odisha.[42][43]

Electoral performance

[edit]| # | Position | Took office | Left office | Constituency | State |

| 1 | Member of Legislative Assembly | 1957 | 1977 | Manthani | Andhra Pradesh[b] |

| 2 | Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | 1977 | 1980 | Hanamkonda | Andhra Pradesh[b] |

| 3 | Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | 1980 | 1984 | Hanamkonda | Andhra Pradesh[b] |

| 4 | Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | 1984 | 1989 | Ramtek | Maharashtra |

| 5 | Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | 1989 | 1991 | Ramtek | Maharashtra |

| 6 | Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | 1991 | 1996 | Nandyal | Andhra Pradesh |

| 7 | Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | 1996 | 1998 | Berhmapur | Odisha |

- ^ Then United Andhra Pradesh

- ^ a b c On 2 June 2014, Andhra Pradesh was split to form two separate states. Both Manthani (Assembly constituency) and Hanamkonda (Lok Sabha constituency) are now in the present-day state of Telangana.

Prime minister (1991–1996)

[edit]Economic reforms

[edit]

Adopted to avert the impending 1991 economic crisis,[3][44] the reforms progressed furthest in the areas of opening up to foreign investment, reforming capital markets, deregulating domestic business, and reforming the trade regime. Rao's government's goals were reducing the fiscal deficit, privatisation of the public sector and increasing investment in infrastructure. Trade reforms and changes in the regulation of foreign direct investment were introduced to open India to foreign trade while stabilising external loans. Rao wanted I. G. Patel as his Finance Minister.[45] Patel was an official who helped prepare 14 budgets, an ex-governor of the Reserve Bank of India and had headed The London School of Economics.[45] But Patel declined. Rao then chose Manmohan Singh for the job. Manmohan Singh, an acclaimed economist, played a central role in implementing these reforms.

Major reforms in India's capital markets led to an influx of foreign portfolio investment. The major economic policies adopted by Rao include:

- Abolishing in 1992 the Controller of Capital Issues which decided the prices and number of shares that firms could issue.[44][46]

- Introducing the SEBI Act of 1992 and the Security Laws (Amendment) which gave SEBI the legal authority to register and regulate all security market intermediaries.[44][47]

- Opening up in 1992 of India's equity markets to investment by foreign institutional investors and permitting Indian firms to raise capital on international markets by issuing Global Depository Receipts (GDRs).[48]

- Starting in 1994 of the National Stock Exchange as a computer-based trading system which served as an instrument to leverage reforms of India's other stock exchanges. The NSE emerged as India's largest exchange by 1996.[49]

- Reducing tariffs from an average of 85 per cent to 25 per cent, and rolling back quantitative controls. (The rupee was made convertible on trade account.)[50]

- Encouraging foreign direct investment by increasing the maximum limit on share of foreign capital in joint ventures from 40 to 51% with 100% foreign equity permitted in priority sectors.[51]

- Streamlining procedures for FDI approvals, and in at least 35 industries, automatically approving projects within the limits for foreign participation.[44][52]

The impact of these reforms may be gauged from the fact that total foreign investment (including foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, and investment raised on international capital markets) in India grew from a minuscule US$132 million in 1991–92 to $5.3 billion in 1995–96.[51] Rao began industrial policy reforms with the manufacturing sector. He slashed industrial licensing, leaving only 18 industries subject to licensing. Industrial regulation was rationalised.[44]

National security, foreign policy and crisis management

[edit]

Rao energised the national nuclear security and ballistic missiles programme, which ultimately resulted in the 1998 Pokhran nuclear tests. It is speculated that the tests were actually planned in 1995, during Rao's term in office,[53] and that they were dropped under American pressure when the US intelligence got the whiff of it.[54] Another view was that he purposefully leaked the information to gain time to develop and test thermonuclear device which was not yet ready.[55] He increased military spending, and set the Indian Army on course to fight the emerging threat of terrorism and insurgencies, as well as Pakistan and China's nuclear potentials. It was during his term that khalistani terrorism in the Indian state of Punjab was finally defeated.[56] Also scenarios of aircraft hijackings, which occurred during Rao's time ended without the government conceding the terrorists' demands.[57] He also directed negotiations to secure the release of Doraiswamy, an Indian Oil executive, from Kashmiri terrorists who kidnapped him,[58] and Liviu Radu, a Romanian diplomat posted in New Delhi in October 1991, who was kidnapped by Sikh terrorists.[59] Rao also handled the Indian response to the occupation of the Hazratbal holy shrine in Jammu and Kashmir by terrorists in October 1993.[60] He brought the occupation to an end without damage to the shrine. Similarly, he dealt with the kidnapping of some foreign tourists by a terrorist group called Al Faran in Kashmir valley in 1995 effectively. Although he could not secure the release of the hostages, his policies ensured that the terrorists demands were not conceded to, and that the action of the terrorists was condemned internationally, including Pakistan.[61]

Rao also made diplomatic overtures to Western Europe, the United States, and China.[62][63][64] He decided in 1992 to bring into the open India's relations with Israel, which had been kept covertly active for a few years during his tenure as a Foreign Minister, and permitted Israel to open an embassy in New Delhi.[65] He ordered the intelligence community in 1992 to start a systematic drive to draw the international community's attention to Pakistan's sponsorship of terrorism against India and not to be discouraged by US efforts to undermine the exercise.[66][67] Rao launched the Look East foreign policy, which brought India closer to ASEAN.[68] According to Rejaul Karim Laskar, a scholar of India's foreign policy and ideologue of Rao's Congress Party, Rao initiated the Look East policy with three objectives in mind, namely, to renew political contacts with the ASEAN-member nation; to increase economic interaction with South East Asia in trade, investment, science and technology, tourism, etc.; and to forge strategic and defence links with several countries of South East Asia.[69] He decided to maintain a distance from the Dalai Lama in order to avoid aggravating Beijing's suspicions and concerns, and made successful overtures to Tehran. The 'cultivate Iran' policy was pushed through vigorously by him.[70] These policies paid rich dividends for India in March 1994, when Benazir Bhutto's efforts to have a resolution passed by the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva on the human rights situation in Jammu and Kashmir failed, with opposition by China and Iran.[71]

Rao's crisis management after 12 March 1993 Bombay bombings was highly praised. He personally visited Bombay after the blasts and after seeing evidence of Pakistani involvement in the blasts, ordered the intelligence community to invite the intelligence agencies of the US, UK and other West European countries to send their counter-terrorism experts to Bombay to examine the facts for themselves.[72]

Economic crisis and initiation of liberalisation

[edit]Rao decided that India, which in 1991 was on the brink of bankruptcy,[73] would benefit from opening its economy. He appointed economist Manmohan Singh, a former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, as Finance Minister to accomplish his goals.[4] This liberalisation was criticised by many socialist nationalists at that time.[74]

He is often referred as 'Father of Indian Economic Reforms'.[75] PV Narasimha Rao: The 10th Prime Minister who changed the face of Indian economy under Rao's mandate and leadership, then finance minister Manmohan Singh launched a series of pro-globalisation reforms, including International Monetary Fund (IMF) policies, to rescue the almost-bankrupt nation from economic collapse.[76]

Indian nuclear programme

[edit]Kalam recalls that Rao ordered him not to test, since "the election result was quite different from what he anticipated". The BJP's Atal Bihari Vajpayee took over as prime minister on 16 May 1996. Narasimha Rao, Abdul Kalam and R Chidambaram went to meet the new prime minister "so that", in Kalam's telling, "the smooth takeover of such a very important programme can take place".[77]

Rao knew he had only one chance to test before sanctions kicked in, i.e., he could not both test conventional atomic bombs in December 1995 as well as the hydrogen bomb separately in April 1996. As Shekhar Gupta – who has had unprecedented access to Rao as well as the nuclear team – speculates: "By late 1995, Rao's scientists told him that they needed six more months. They could test some weapons but not others...thermonuclear etc. So Rao began a charade of taking preliminary steps to test, without intending to test then."

National elections were scheduled for May 1996, and Rao spent the next two months campaigning. On 8 May at 21:00, Abdul Kalam was asked to immediately meet with the prime minister. Rao told him, "Kalam, be ready with the Department of Atomic Energy and your team for the N-test and I am going to Tirupati. You wait for my authorisation to go ahead with the test. DRDO-DAE teams must be ready for action." Rao energised the national nuclear security and ballistic missiles programme. His efforts resulted in the 1998 Pokhran nuclear tests.

Vajpayee said that, in May 1996, a few days after he had succeeded Rao as prime minister, "Rao told me that the bomb was ready. I only exploded it."

"Saamagri tayyar hai," Rao had said. ("The ingredients are ready.") "You can go ahead." The conventional narrative at the time was that prime minister Rao had wanted to test nuclear weapons in December 1995. The Americans had caught on, and Rao had dithered – as was his wont. Three years later, prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee fulfilled his party's campaign promise by ordering five nuclear tests below the shimmering sands of Rajasthan.[77]

Handling of separatist movements

[edit]Rao successfully decimated the Sikh separatist movement and neutralised Kashmiri separatist movement to a certain extent. It is said that Rao was 'solely responsible' for the decision to hold elections in Punjab, no matter how narrow the electorate base would be.[78] In dealing with Kashmir Rao's government was highly restrained by US government and its president Bill Clinton. Rao's government introduced the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA),[79] India's first anti-terrorism legislation, and directed the Indian Army to eliminate the infiltrators from Pakistan.[80] Despite a heavy and largely successful Army campaign, Pakistani Media accuses that the state descended into a security nightmare. Tourism and commerce were also largely disrupted.

Babri Mosque demolition

[edit]In the late 1980s, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) brought the Ram Janmabhoomi issue to the centre stage of national politics, and the BJP and VHP began organising large-scale protests in Ayodhya and around the country.

Members of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) demolished the Babri Mosque (which was constructed by Mir Baqi, a general of India's first Mughal Emperor, Babur[81]) in Ayodhya on 6 December 1992.[82] The site is believed to be the birthplace of the Hindu god Rama.[83][84] The destruction of the disputed structure, which was widely reported in the international media, unleashed large scale communal violence, the most extensive since the Partition of India. Hindus and Muslims were involved in massive rioting across the country and almost every major city, including Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Ahmedabad, Hyderabad and Bhopal, struggled to control the unrest.[85]

Rao had assured the Muslims that Babri Mosque would be rebuilt.[86] The Liberhan Commission, after extensive hearing and investigation, exonerated Rao. It pointed out that Rao was heading a minority government and accepted the centre's argument that central forces could not be deployed by the Union, nor could President's Rule be imposed "on the basis of rumours or media reports". Taking such a step would have created a "bad precedent" damaging the federal structure and would have "amounted to interference" in the state administration, it said. The state "deliberately and consciously understated" the risk to the disputed structure and general law and order. The commission also stated that the Governor's assessment of the situation was either badly flawed or overly optimistic and was thus a major impediment for the central government. The Commission further said, "... knowing fully well that its facetious undertakings before the Supreme Court had bought it sufficient breathing space, it (state government) proceeded with the planning for the destruction of the disputed structure. The Supreme Court's own observer failed to alert it to the sinister undercurrents. The Governor and its intelligence agencies, charged with acting as the eyes and ears of the central government also failed in their task. Without substantive procedural prerequisites, neither the Supreme Court, nor the Union of India was able to take any meaningful steps."[87]

In another interview with journalist Shekhar Gupta, Rao spoke further about the demolition. He said he was wary of the impact of hundreds of deaths on the nation and that it could have been far worse. He also argued that he had to consider the possibility that some of the troops would have turned around and joined the mobs instead. Regarding the dismissal of Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Kalyan Singh, he said, "mere dismissal does not mean you can take control. It takes a day or so appointing advisers, sending them to Lucknow, taking control of the state. Meanwhile, what had to happen would have happened and there would have been no Kalyan Singh to blame either."[88]

Latur earthquake

[edit]In 1993, a strong earthquake in Latur, Maharashtra killed nearly 10,000 people and displaced hundreds of thousands.[89] Rao was applauded by many for using modern technology and resources to organise major relief operations to assuage the stricken people, and for schemes of economic reconstruction.[90]

Purulia arms drop case

[edit]Narasimha Rao was charged for his facilitating safe exit of accused of 1995 Purulia arms drop case.[91] Although, it was never proved.

Corruption charges and acquittal

[edit]In the early 1990s, one of the earliest accusations came in the form of stockbroker Harshad Mehta, who through his lawyer, Ram Jethmalani, revealed that he had paid a sum of one crore rupees to the then prime minister Rao for help in closing his cases.[92]

Rao's government faced a no-confidence motion in July 1993, because the opposition felt that it did not have sufficient numbers to prove a majority. It was alleged that Rao, through a representative, offered millions of rupees to members of the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM), and possibly a breakaway faction of the Janata Dal, to vote for him during the confidence motion. Shailendra Mahato, one of those members who had accepted the bribe, turned approver. In 1996, after Rao's term in office had expired, investigations began in earnest in the case. In 2000, after years of legal proceedings, a special court convicted Rao and his colleague, Buta Singh (who is alleged to have escorted the MPs to the Prime Minister).[93] Rao was sentenced to rigorous imprisonment up to three years and a fine of 100,000 rupees ($2,150) for corruption.[94] Rao appealed to the Delhi High Court and remained free on bail. In 2002, the Delhi High Court overturned the lower court's decision mainly due to the doubt in credibility of Mahato's statements, which were extremely inconsistent, and both Rao and Buta Singh were acquitted of the charges.[95]

Rao, along with fellow minister K. K. Tewary, Chandraswami and K. N. Aggarwal, were accused of forging documents showing that Ajeya Singh had opened a bank account in the First Trust Corporation Bank in Saint Kitts and deposited $21 million in it, making his father V. P. Singh its beneficiary. The alleged intent was to tarnish V. P. Singh's image. This supposedly happened in 1989. However, only after Rao's term as PM had expired in 1996, was he formally charged by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) for the crime. Less than a year later the court acquitted him due to lack of evidence linking him with the case.[96]

Lakhubhai Pathak, an Indian businessman living in England, alleged that Chandraswami and K. N. Aggarwal alias Mamaji, along with Rao, cheated him out of $100,000. The amount was given for an express promise for allowing supplies of paper pulp in India, and Pathak alleged that he spent an additional $30,000 entertaining Chandraswami and his secretary. Narasimha Rao and Chandraswami were acquitted of the charges in 2003 and before his death, Rao was acquitted of all the cases charged against him.[97]

Later life and financial difficulties

[edit]In spite of significant achievements in a difficult situation, in the 1996 general elections the Indian electorate voted out Rao's Congress Party. Soon, Sonia Gandhi's supporters forced Mr. Rao to step down as Party President.[citation needed] He was replaced by Sitaram Kesri.

Rao rarely spoke of his personal views and opinions during his 5-year tenure. After his retirement from national politics, he published a novel called The Insider.[98] The book, which follows a man's rise through the ranks of Indian politics, resembled events from Rao's own life.

According to a vernacular source, despite holding many influential posts in Government, he faced many financial troubles. One of his sons was educated with the assistance of his son-in-law. He also faced trouble paying fees for a daughter who was studying medicine.[99] According to P. V. R. K. Prasad, an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer who was Narasimha Rao's media advisor when the latter was Prime Minister, Rao asked his friends to sell away his house at Banjara Hills to clear the dues of lawyers.[100]

Death

[edit]

Rao suffered a heart attack on 9 December 2004, and was taken to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences where he died 14 days later at the age of 83.[101][102] His funeral was attended by the Prime Minister of India Manmohan Singh, the Home Affairs Minister Shivraj Patil, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) president L. K. Advani, the Defence Minister Pranab Mukherjee, the Finance Minister P. Chidambaram and many other dignitaries. Rao was a long-time widower, since his wife died in 1970 and he was survived by his eight children.[103] A memorial was built for P. V. Narasimha Rao located adjacent to Sanjeevaiah Park, developed in 2005 on 1.2 hectares (2.9 acres) of land known as Gyan Bhumi.[104] The Government of Telangana declared his birthday to be celebrated as a Telangana State function in 2014.[105] Seven days of state mourning was declared upon his death.[106]

In 2015, Narasimha Rao was accorded a memorial in Delhi at Ekta Sthal, which is now integrated with Rashtriya Smriti, a common place for erecting memorials for former Presidents, PMs and others. The memorial is raised on a plinth in marble bearing text highlighting briefly his contributions. The plaque describes Rao: "Known as the scholar Prime Minister of India, Shri P V Narasimha Rao was born on 28 June 1921 in Vangara, Karimnagar District in Telangana state. He rose to prominence as freedom fighter who fought the misrule of the Nizam during the formative years of his political career. A reformer, educationist, scholar, conversant in 15 languages and known for his intellectual contribution, he was called the 'Brihaspati' (wiseman) of Andhra Pradesh."[107]

Personal life

[edit]In 1931, the 10-year-old Narasimha Rao was married to Satyamma, a girl of his own age, belonging to his own community and coming from a family of similar background.[108] They were married for the entirety of their lives. Smt. Satyamma died on 1 July 1970.

The couple had three sons and five daughters. Their eldest son, P. V. Ranga Rao, was the education minister in Kotla Vijaya Bhaskara Reddy's cabinet and an MLA from Hanamakonda Assembly Constituency, in Warangal District for two terms. The second son, P. V. Rajeshwar Rao, was a Member of Parliament of the 11th Lok Sabha (15 May 1996 – 4 December 1997) from Secunderabad Lok Sabha constituency.[109][110] The third son is P.V. Prabhakara Rao.

The five daughters of P.V. Narasimha Rao are Smt. N. Sharada Devi, wife of Sri N. Venkata Krishna Rao; Smt. K. Saraswathi Devi, wife of K. Sarath Chandra Rao; Smt. S. Vani Devi, wife of Sri S. Divakara Rao; Smt. Vijaya Somayaji, wife of Sri Ramakrishna Somayaji; and Smt. K. Jaya Devi, wife of Sri K. Revathi Nandan.

Legacy

[edit]Biographical and political evaluation

[edit]On the occasion of 25 years of economic liberalisation in India, there have been several books published by authors, journalists and civil servants evaluating Rao's contributions.[111] While Vinay Sitapati's book Half Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao transformed India (2016) gives a renewed biographical picture of his entire life,[112] Sanjay Baru's book 1991: How P V Narasimha Rao made history (2016)[113] and Jairam Ramesh's book From the brink to back: India's 1991 story (2015)[114] focuses on his role in unleashing the reforms in the year 1991 as the Prime Minister of India.

Literary achievements

[edit]Rao's mother tongue was Telugu, and he had an excellent command of Marathi. In addition to nine Indian languages (Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Odia, Sanskrit, Tamil and Urdu), he spoke Arabic, English, French, German, Persian and Spanish.[33][115] He was able to speak 17 languages.[29][30] Due to his college education in Fergusson College in Pune, then an affiliated college of the University of Mumbai (but now with Pune University), he became a very prolific reader and speaker of Marathi.[21] He translated the great Telugu literary work Veyipadagalu of Kavi Samraat Viswanatha Satyanarayana into Hindi as Sahasraphan. He also translated Hari Narayan Apte's Marathi novel Pan Lakshat Kon Gheto (But Who Pays Attention?) into Telugu. He was also invited to be the chief guest of Akhil Bhartiya Marathi Sahitya Sanmelan where he gave speech in Marathi.

In his later life he wrote his autobiography, The Insider, which depicts his experiences in politics.

Centenary celebrations

[edit]In June 2020, Government of Telangana, led by Telangana Rashtra Samithi has declared to organise one-year long centenary celebrations of Rao. The state government also decided to set up a memorial and five bronze statues at various places, including Hyderabad, Warangal, Karimnagar, Vangara and Delhi.[116]

In popular culture

[edit]In the year 2019, an independent biographical documentary film named P V: Change with Continuity (2019) directed and produced by Sravani Kotha and Srikar Reddy Gopaladinne released on the streaming platform Vimeo.[117][118][119] The documentary features rare archival footage and interviews of several distinguished people closely related to Rao's life and work.[120]

Suresh Kumar appeared as Rao in the 2019 film NTR: Mahanayakudu directed by Krish which chart the life of the Indian actor-politician N. T. Rama Rao.[121] The same year, Ajit Satbhai portrayed Rao as the former Prime Minister of India in the film The Accidental Prime Minister by Vijay Gutte, about Manmohan Singh.[122]

Pradhanmantri (lit. 'Prime Minister'), a 2013 Indian docudrama television series which aired on ABP News and covers the various policies and political tenures of Indian PMs, based the twentieth episode – "P. V. Narasimha Rao and Corruption charges against him" – on his term as the country's leader; Ravi Jhankal portrayed the role of Rao.[123]

Honours, awards and recognition

[edit]Rao was awarded Bharat Ratna (posthumous) on 9 February 2024. Rao was awarded the Pratibha Murthy Lifetime Achievement Award.[124] Many people across the party line supported the name of P. V. Narasimha Rao for Bharat Ratna. Telangana Chief Minister K. Chandrashekhar Rao supported the move to give Bharat Ratna to Rao.[125] BJP leader Subramanian Swamy supported the move to give Bharat Ratna to Rao.[126] Earlier in 2015, Sanjay Baru said that former PM Manmohan Singh wanted to give Bharat Ratna to Rao but failed.[127]

In September 2020, Telangana Legislative Assembly adopted a resolution seeking to confer Bharat Ratna on Rao. The resolution also requested the Central Government to rename the University of Hyderabad after him.[128][129]

State honours

[edit]| Ribbon | Decoration | Country | Date | Note | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bharat Ratna | 2024 | The highest civilian honour of India. | [130] |

See also

[edit]- 1993 Bombay bombings

- Demolition of the Babri Masjid

- 1993 Latur earthquake

- The Insider (Rao novel)

- P.V. Narasimha Rao Expressway

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Dean, Adam (2022), "India's Middle Path: Preventive Arrests and General Strikes", Opening Up by Cracking Down: Labor Repression and Trade Liberalization in Democratic Developing Countries, Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions, Cambridge University Press, pp. 86–112, doi:10.1017/9781108777964.006, ISBN 978-1-108-47851-9, archived from the original on 9 February 2024, retrieved 29 October 2022

- ^ "PV Narasimha Rao Remembered as Father of Indian Economic Reforms". voanews.com. VOA News. 23 December 2004. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Narasimha Rao led India at crucial juncture, was father of economic reform: Pranab". The Times of India. 31 December 2012. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ a b c "Narasimha Rao – a Reforming PM". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 23 December 2004. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Arvind Kumar, Arun Narendhranath (3 October 2001). India must embrace unfettered free enterprise Archived 12 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Daily News and Analysis.

- ^ V. Venkatesan (14 January 2005). "Obituary: A scholar and a politician". Frontline. 22 (1). Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "PV Narasimha Rao Passes Away". tlca.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ How PV became PM Archived 29 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 2 July 2012.

- ^ "क्या नरसिम्हा राव बाबरी मस्जिद गिरने से बचा सकते थे?". BBC News हिंदी (in Hindi). Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "Narasimha Rao performed puja during demolition of Babri Masjid: Book". The Times of India. 5 July 2012. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "Bharat Ratna for P V Narasimha Rao: Congress's Achilles heel, the PM it 'forgot'". The Indian Express. 9 February 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "PV Narasimha Rao, a forgotten prime minister". Livemint. 21 June 2016. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ "Half Lion: Resurrecting Narasimha Rao". Times of India Blog. 26 July 2016. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Raman, B (27 December 2004). "Narasimha Rao: Our finest PM ever?". Rediff. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Biswas, Soutik (25 July 2016). "Reassessing India's 'forgotten PM'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Padmanabhan, Anil (7 October 2016). "Why Narasimha Rao is suddenly a star". Livemint. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Gupta, Shekhar (23 December 2018). "Why Narasimha Rao is India's most vilified, deliberately misunderstood and forgotten PM". ThePrint. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Pushkarna, Vijaya (26 September 2019). "The PMs who shaped India". The Week. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Mishra, Samiran (9 February 2024). "Bharat Ratna For Former PMs Charan Singh, PV Narasimha Rao". NDTV. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ a b Reddy 1993, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "P.V. Narasimha Rao", britannica.com, 17 May 2023, archived from the original on 2 June 2023, retrieved 18 April 2020

- ^ a b "People hail decision on PV's birth anniversary". The Hindu. 25 June 2014. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Aggarwala, Adish C. (1995). P.V. Narasimha Rao, Scholar Prime Minister. Amish Publications. pp. 215, 298. ISBN 978-81-900289-1-2. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

His father Mr. Sitarama Rao and mother Mrs. Rukma Bai. With his wife Mrs. Satyamma

- ^ Sitapati 2016.

- ^ a b c "Shri P. V. Narasimha Rao", pmindia.gov.in, archived from the original on 1 September 2020, retrieved 18 April 2020

- ^ a b "Pamulaparthi Sadasiva Rao". M. Rajagopalachary, Pamulaparthi Sadasiva Rao Memorial Endowment Lecture. kakatiyapatrika.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "With PV". kakatiyapatrika.com. 31 October 2009. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "The meek inheritor". India Today. 15 July 1991. Archived from the original on 17 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

Rao was one of the first converts to the new technology. Today, he is so adept with the machines that along with the 10 Indian and four foreign languages, Rao has also taught himself some computer languages and is now able to programme them.

- ^ a b "PVN – Obituary". 23 December 2004. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ a b "'PV': A scholar, a statesman". 23 December 2004. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

A Sahitya Ratan in Hindi, Rao was fluent in several languages, including Spanish.

- ^ "Narasimha Rao cremated". thehindubusinessline.com. 26 December 2004. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ^ "A Profile of P.V. Narasimha Rao" (PDF). Embassy of India in Washington. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2010.

- ^ a b "PV Narasimha Rao". The Daily Telegraph. 24 December 2004. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ "The Lonely Masks of Narasimha Rao". mjakbar.org. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- ^ John F. Burns (21 May 1995). Crisis in India: Leader Survives, for Now Archived 1 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ Observations on Indian Independence Day Archived 12 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Subash Kapila. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Rao's world record Archived 9 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. rediff.com. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ "Indian Political Trivia". Archived from the original on 6 February 2005. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Retrieved 19 April 2007. - ^ "Rao takes oath in India, names his cabinet". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 22 June 1991. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "Profile: Manmohan Singh". BBC News. 30 March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ Jha, Prabhat (24 December 2020). "No one like Atalji". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Ramtek voters in tepid mood". The Times of India. 15 March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ "orissa". Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e

"India's Pathway through Financial Crisis" (PDF). globaleconomicgovernance.org. Arunabha Ghosh. Global Economic Governance Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Time To Tune In To FM Archived 29 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine. Indiatoday.com (25 February 2002). Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ Securities and Exchange Commission Act Archived 2 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ "Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, 1992". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). vakilno1.com. - ^ "India's Economic Policies". Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Indian Investment Centre. Retrieved 2 March 2007. - ^ Ajay Shah and Susan Thomas. How NSE surpassed BSE Archived 7 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ J. Bradford DeLong (July 2001). "The Indian Growth Miracle". Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). berkeley.edu. - ^ a b Ajay Singh and Arjuna Ranawana. India. Conflict of Interest. Local industrialists issue a broadside against multinationals Archived 1 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Asiaweek. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ FDI in India Archived 28 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Kulwindar Singh. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Narasimha Rao and the bomb Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Clinton stopped Rao from testing nukes. sify.com (5 February 2004).

- ^ The mole and the fox Archived 9 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine. Shekhar Gupta. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Punjab Assessment Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ National Security Guards Archived 29 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ 5 Years On: Scarred and scared Archived 1 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- ^ Bishwanath Ghosh. "Held to ransom". Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). newindpress.com. - ^ Profile of Changing Situation Archived 18 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ "Al Faran and the Hostage Crisis in Kashmir". Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). subcontinent.com (10 March 1996). - ^ Upadhyaya, Shishir (5 September 2019). India's Maritime Strategy: Balancing Regional Ambitions and China. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-429-67375-7. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ Singh, S. Nihal (21 October 1993). "Opinion | India Keeps Its Foreign Options Open". The New York Times. International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ Goshko, John M. (20 May 1994). "Clinton Moves To Ease Relationship With India". Washington Post. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "Strategic Partnership Between Israel and India". meria.idc.ac.il. P.R. Kumaraswamy. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Pakistan and Terrorism". saag.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006.

- ^ Never trust the US on Pakistan Archived 30 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. rediff.com (21 July 2006). Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Narasimha Rao and the `Look East' policy[usurped]. The Hindu (24 December 2004). Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Laskar, Rejaul Karim (July 2005). "Strides in Look East Policy". Congress Sandesh. 7 (11): 19.

- ^ "India and the Middle East". photius.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Samuel P. Huntington, New World Order. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Lessons from the Mumbai blasts Archived 6 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. rediff.com (14 March 2003). Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ "India's economic reforms". findarticles.com. [dead link]

- ^ John Greenwald; Anita Pratap; Dick Thompson (18 September 1995). "No Passage to India". Time. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ "PV Narasimha Rao: The 10th Prime Minister who changed the face of Indian economy". India Today. 23 December 2016. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Kujur, Anupa (28 June 2018). "PV Narasimha Rao's 97th birth anniversary: Remembering India's 'modern-day Chanakya'". Moneycontrol. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ a b Sitapati, Vinay (1 July 2016). "Narasimha Rao, not Vajpayee, was the PM who set India on a nuclear explosion path". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Quiet Goes The Don Archived 1 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Outlookindia.com (17 January 2005). Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Terrorism & Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act". satp.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Meredith Weiss (25 June 2002). "The Jammu & Kashmir Conflict" (PDF). Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). yale.edu. - ^ NCERT Pg 184 (Politics in India since Independence, Class XII)

- ^ "Flashpoint Ayodhya". archaeology.org. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ "Ayodhya verdict: Indian top court gives holy site to Hindus". BBC News. 9 November 2019. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "'Faith, evidence prove Masjid was on Ram's birthplace'". Deccan Herald. 9 November 2019. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ P. V. Narasimha Rao 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Kulkarni, Sagar (9 November 2019). "Narasimha Rao, the man Cong blames for Babri demolition". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Rao govt was reduced to position of helpless bystander". The Indian Express. 25 November 2009. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Tearing down Narasimha Rao Archived 6 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Indianexpress.com (28 November 2009). Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Latur EarthQuake of 30 September 1993". Archived from the original on 7 March 2005. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). imd.ernet.in. - ^ "PV Narsimha Rao – IIFL". Indiainfoline. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Purulia arms drop had govt sanction: Davy | India News – Times of India". The Times of India. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Bobb, Dilip (15 July 1993). "Securities scam: Harshad Mehta claims to have paid Rs 1 crore to PM Narasimha Rao". India Today. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Rao, Buta convicted in JMM bribery case". The Tribune. 29 September 2000. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ SOUTH ASIA | Ex-Indian PM sentenced to jail Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News (12 October 2000). Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Ex-Indian PM cleared of bribery Archived 9 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News (15 March 2002). Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ St Kitts case: Chronology of events. The Times of India (25 October 2004). Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ Kumar, Nirnimesh (23 December 2003). "Rao acquitted in Lakhubhai Pathak case". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 February 2004. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ P V N Rao 2000.

- ^ "Nindalapaalaina Aparachanukyudu-2". Telugu.greatandhra.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ P V Krishna Rao (4 January 2010). PV made scapegoat in Babri case Archived 21 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. newindianexpress.com

- ^ Narasimha Rao passes away at the age of 83. Hindu.com (24 December 2004). Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ Sitapati, Vinay. "Day after Babri Masjid demolition, Narasimha Rao kept tabs on Sonia Gandhi courtesy the IB". No. 24 June 2016. The INdian Express. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Nation bids adieu to Narasimha Rao. The Hindu.

- ^ PVNARASIMHARAO Archived 7 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 29 June 2017

- ^ "PVNR Birth Celebrations a State function". Deccan-Journal. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Welcome to Embassy of India, Washington D C, USA". Welcome to Embassy of India, Washington D C, USA. 8 February 2024. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "10 years after death, Narasimha Rao gets memorial in Delhi | India News – Times of India". The Times of India. 30 June 2015. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Sitapati, Vinay (2018). The Man who Remade India: A Biography of P.V. Narasimha Rao. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-069285-8. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "Biographical Sketch of P.V. Rajeshwar Rao". Parliament of India. Archived from the original on 12 August 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "Sri. P.V.Rajeswara Rao". Matrusri Institute of P.G. Studies. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ Reddy, C Rammanohar (22 October 2016). "Questions about Narasimha Rao". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Gupta, Smita (9 July 2016). "In the pantheon of heroes". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Hebbar, Nistula (26 September 2016). "Politicians were the heroes of 1991". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ M, Ramesh (23 September 2015). "Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh jugalbandi saved India: Jairam Ramesh". The Hindu Businessline. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Brown, Derek (24 December 2004). "PV Narasimha Rao". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Telangana to observe year-long centenary celebrations of PV Narasimha Rao from June 28". Zee News. 23 June 2020. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ title, IMDB. "PV: Change with Continuity". IMDB. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Kotha, Sravani. "PV: Change with Continuity". www.vimeo.com. Vimeo. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Audio, Madhura (31 March 2019). "PV NARASIMHA RAO – Change With Continuity Trailer". Youtube. Madhura Audio. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Dundoo, Sangeetha Devi (22 April 2019). "A film for the archives". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Dundoo, Sangeetha Devi (22 February 2019). "'NTR Mahanayakudu' review: A raging political storm". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Accidental Prime Minister". Kinopoisk. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Pradhanmantri – Episode 20 on PV Narasimha Rao". ABP News. 24 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Former PM P.V. Narasimha Rao awarded Pratibha Murthy Lifetime Achievement Award". India Today. 21 January 2002. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ PTI (28 June 2014). "KCR bats for Bharat Ratna to Narasimha Rao". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Singh, Anuraag (22 February 2015). "Swamy seeks Bharat Ratna for ex-PM PV Narsimha Rao". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Dhawan, Himanshi (2 January 2015). "Manmohan wanted to give Bharat Ratna to Atal, Narasimha Rao but failed: Baru". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Rajeev, M. (8 September 2020). "Telangana Assembly adopts resolution seeking Bharat Ratna for P.V. Narasimha Rao". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Telangana assembly proposes Bharata Ratna for PV Narasimha Rao". The Siasat Daily. 8 September 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "PV Narasimha Rao, Chaudhary Charan Singh, MS Swaminathan to get Bharat Ratna: PM Modi". Hindustan Times. 9 February 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Rao, P V N (2000), The Insider, Penguin, ISBN 978-0140271171

- Reddy, Narendra (1993), P.V. Narasimha Rao, years of power, Har-Anand Publications, ISBN 9788124101360

- Sitapati, Vinay (27 June 2016), Half - Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Transformed India, Penguin Random House India Private Limited, ISBN 9789386057723 – via Google Books

Further reading

[edit]- The Quest For Peace with Kotha Satchidananda Murthy (1986)

- The Great Suicide written pseudonymously (1990) Malik, Ashok. "Rao, Singh and the Great Suicide". ORF. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- India and the Asia-Pacific: Forging a New Relationship (1994)

- The Insider (1998)

- A Long Way: Selected Speeches (2002)

- Ayodhya 6 December 1992 published posthumously (2006)

- Half – Lion: How P.V Narasimha Rao Transformed India by Vinay Sitapati (2016), Retitled in 2018 when released by Oxford University Press as The Man Who Remade India: A Biography of P.V. Narasimha Rao by Vinay Sitapathi

- 1991: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Made History by Sanjaya Baru (2016)

- Narasimha Rao: Unsung Hero by Krishna Mohan Sharma (2017)

- P. V. Narasimha Rao (2006), Ayodhya 6 December 1992, Penguin Books India, ISBN 0670058580

- Shukla, Subhash. "Foreign Policy Of India Under Narasimha Rao Government" (PhD dissertation, U of Allahabad, 1999) online free, bibliography pp 488–523.

- Singh, Sangeeta. "Trends in India's Foreign Policy: 1991–2009." (PhD dissertation, Aligarh Muslim University, 2016) online

External links

[edit]- P. V. Narasimha Rao

- 1921 births

- 2004 deaths

- Prime ministers of India

- Union ministers from United Andhra Pradesh

- Chief ministers of Andhra Pradesh

- Founders of Indian schools and colleges

- Indian National Congress politicians from Andhra Pradesh

- Indian Hindus

- People from Karimnagar

- Presidents of the Indian National Congress

- Rao administration

- Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University alumni

- University of Mumbai alumni

- India MPs 1977–1979

- India MPs 1980–1984

- India MPs 1984–1989

- India MPs 1989–1991

- India MPs 1991–1996

- India MPs 1996–1997

- Indian male novelists

- 20th-century Indian novelists

- 20th-century Indian lawyers

- Lok Sabha members from Maharashtra

- Lok Sabha members from Andhra Pradesh

- Lok Sabha members from Odisha

- Osmania University alumni

- Chief ministers from Indian National Congress

- Fergusson College alumni

- Heads of government who were later imprisoned

- Defence ministers of India

- Law ministers of India

- Recipients of the Bharat Ratna

- Ministers of education of India

- Ministers for external affairs of India

- Ministers of internal affairs of India

- Commerce and industry ministers of India

- 20th-century prime ministers of India

- Members of the Cabinet of India

- Health ministers of India

- Indian independence activists from Telangana

- People from Hanamkonda district

- Telugu politicians

- Telugu–Hindi translators

- Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi