Presidency of Rodrigo Duterte

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (July 2022) |

| |

| Presidency of Rodrigo Duterte June 30, 2016 – June 30, 2022 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | PDP–Laban |

| Election | 2016 |

| Seat | Malacañang Palace, Manila |

|

| |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Early political career

Personal and public image |

||

Rodrigo Duterte's tenure as the 16th president of the Philippines began with his inauguration on June 30, 2016, following his landslide victory in the 2016 presidential election, succeeding Benigno Aquino III. Duterte's presidency spanned six years, ending on June 30, 2022. Duterte is the first president from Mindanao; the oldest person to be elected president of the Philippines, at age 71; and the first Philippine president to have worked in the three branches of the government.[1] His election victory was propelled by growing public frustration over the tumultuous post-EDSA democratic governance, which favored political and economic elite over ordinary Filipinos.[2][3]

Duterte started a nationwide campaign to rid the country of crime, corruption, and illegal drugs.[4][5] He implemented an intensified crackdown on illegal drugs which significantly reduced drug proliferation in the country,[6] but saw about 6,600 persons linked to the illegal drug trade killed as of July 2019,[7] attracting international criticism. His administration withdrew the Philippines from the International Criminal Court following the court's launch of a preliminary examination into crimes against humanity allegedly committed by Duterte and other top officials of the war on drugs.

Duterte increased infrastructure spending and launched an ambitious infrastructure program. He initiated liberal economic reforms to attract foreign investors, and reformed the country's tax system through a comprehensive tax reform program. He took measures to eliminate corruption and red tape by establishing freedom of information under the Executive branch and signing the Ease of Doing Business Act to create a better business environment. He granted free irrigation to small farmers and liberalized rice imports by signing the Rice Tariffication Law to stabilize rice prices.

Duterte implemented an intensified campaign against terrorism and communist insurgency. He signed a controversial law strengthening counterterrorism in the country, and oversaw the five-month long Battle of Marawi, declaring martial law throughout Mindanao and extending it for two years to ensure order in the island. He initially pursued peace talks with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) but cancelled all negotiations in February 2017 following New Peoples Army (NPA) attacks on soldiers, officially declaring the CPP-NPA a terrorist group.[8] He created task forces to end local communist armed conflict and for the reintegration of former communist rebels. He enacted a landmark law establishing the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, and signed proclamations granting amnesty to former rebels.

Duterte signed free college education in all state universities and colleges, institutionalized the alternative learning system, signed the automatic enrollment of all Filipinos under the government's health insurance program, and ordered the full implementation of the Reproductive Health Law. He oversaw the COVID-19 pandemic in the country, implementing strict lockdown measures causing in 2020 a 9.5% contraction in the country's GDP,[9] which eventually recovered to 5.6% in 2021[10] following the gradual reopening of the economy and the implementation of a nationwide vaccination drive.

Duterte has pursued an "independent foreign policy", pursuing improved relations with China and Russia, and lessening the country's dependence on its traditional ally — the United States.[11] He has adopted a cautious, pragmatic, and conciliatory stance towards China compared to his predecessor,[12] and has set aside the previous government policy of using the Philippines v. China ruling to assert the Philippines' claims over the South China Sea and its islands.

Duterte's has been described as a controversial and polarizing figure;[13] his domestic approval rating remained relatively high throughout his presidency despite criticism and international opposition to his anti-narcotics drive.[14][15]

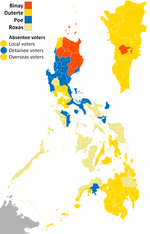

2016 election

Duterte ran for president on a platform of combating crime, corruption, and illegal drugs,[17] and on a popular campaign slogan of "Change is coming".[18][19] He won the 2016 presidential elections, receiving 16,601,997 (39.02%) votes out of a total of 42,552,835 votes, beating his closest rival, Liberal Party standard bearer Mar Roxas, by over 6.6 million votes.[20]

Transition

Duterte's presidential transition began on May 30, 2016, when the Congress of the Philippines proclaimed him the winner of the 2016 Philippine presidential election held on May 9, 2016.[20][21][22] Duterte's transition team was organized after Duterte led by a significant margin at the unofficial count by the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) and the Parish Pastoral Council for Responsible Voting (PPCRV).[23] The transition team prepared the new presidential residence and cabinet appointments, and held cordial meetings with the outgoing administration.[23]

The transition lasted until the day of Duterte's inauguration on June 30, 2016.

Inauguration

Duterte was inaugurated as the sixteenth president of the Philippines on June 30, 2016, at the Rizal Ceremonial Hall, the largest room of the Malacañang Palace, in Manila, in accordance with Duterte's wish to keep the ceremony simple and modest.[24][25] He was sworn in by Bienvenido L. Reyes, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines and Duterte's fraternity brother.[26] Duterte's inauguration was the fourth Philippine presidential inauguration to be held in Malacañang, and the first since the Fifth Philippine Republic was established.[25][24]

Administration and cabinet

On May 31, 2016, a few weeks before his presidential inauguration, Duterte named his Cabinet members,[27] which comprised former military generals, childhood friends, classmates, and leftists.[28] Following his presidential inauguration, he administered a mass oath-taking for his Cabinet officials, and held his first Cabinet meeting on June 30.[29][30] He appointed his long-time personal aide, Bong Go, as Special Assistant to the President (SAP) to provide general supervision to the Presidential Management Staff.[31]

During his tenure, he appointed several retired military generals and police directors to the Cabinet and other government agencies,[32] stressing that they are honest and competent.[33] He initially offered four executive departments to left-leaning individuals,[34] who later resigned, were fired, or rejected by the Commission on Appointments after relations between the government and the communist rebels deteriorated.[35][36] He fired several Cabinet members and officials linked to corruption,[37][38] but has been accused by critics of "recycling" people he fired when he reappointed some of them to other government positions.[39][40] Admitting he is not an economist,[41] he appointed several technocrats in his Cabinet, which he relied upon on economic affairs.[42]

Judicial appointments

Duterte appointed the following to the Supreme Court of the Philippines:

Chief Justice

- Teresita Leonardo-De Castro - August 28, 2018[43]

- Lucas Bersamin - November 28, 2018[44]

- Diosdado Peralta - October 23, 2019[45]

- Alexander Gesmundo - April 5, 2021 (his last SC Chief Justice appointee)[46]

Associate Justices

- Samuel Martires - March 6, 2017 (as Associate Justice),[47] July 26, 2018 (as Ombudsman).[48]

- Noel G. Tijam - March 8, 2017[49]

- Andres Reyes Jr. - July 12, 2017[50]

- Alexander Gesmundo - August 14, 2017 (as Associate Justice)[51]

- Jose C. Reyes - August 10, 2018[52]

- Ramon Paul Hernando - October 10, 2018[53]

- Rosmari D. Carandang - November 28, 2018[54]

- Amy C. Lazaro-Javier - March 7, 2019[55]

- Henri Jean Paul Inting - May 27, 2019[56]

- Rodil V. Zalameda - August 5, 2019[57]

- Edgardo L. de Los Santos - December 3, 2019[58]

- Mario V. Lopez - December 3, 2019[58]

- Samuel H. Gaerlan - January 8, 2020[59]

- Priscilla Baltazar-Padilla - July 16, 2020[60]

- Ricardo Rosario - October 8, 2020[61]

- Jhosep Lopez - January 26, 2021[62]

- Japar Dimaampao - July 2, 2021[63]

- Midas Marquez - September 27, 2021[64]

- Antonio Kho Jr. - February 23, 2022[65]

- Maria Filomena Singh - May 18, 2022 (his last SC appointee)[66]

Major activities

Speeches

- Inaugural Address (June 30, 2016)[67]

- First State of the Nation Address (July 25, 2016)[68]

- Second State of the Nation Address (July 24, 2017)[69]

- Third State of the Nation Address (July 23, 2018)[70]

- Fourth State of the Nation Address (July 22, 2019)[71]

- Fifth State of the Nation Address (July 27, 2020)[72]

- Sixth State of the Nation Address (July 26, 2021)[73]

Major acts and legislation

Duterte signed a total of 379 bills into laws in the 17th Congress; 120 of these laws were national in scope, while 259 were local.[74] In the 18th Congress, Duterte signed 311 bills into law, 119 of which were national in scope, while 192 were local.[75]

Executive orders

National budget

| R. A. No. | Title | Principal Sponsor | Date signed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10924 | General Appropriations Act of 2017 | Loren Legarda | December 22, 2016[76] |

| 10964 | General Appropriations Act of 2018 | Loren Legarda | December 19, 2017[77] |

| 11260 | General Appropriations Act of 2019 | Loren Legarda | April 15, 2019[78] |

| 11464 | Extension of General Appropriations Act of 2019 | Nancy Binay | December 20, 2019[79] |

| 11465 | General Appropriations Act of 2020 | Nancy Binay | January 6, 2020[80] |

| 11520 | General Appropriations Act of 2021 | Nancy Binay | December 29, 2020[81] |

| 11640 | General Appropriations Act of 2022 | Nancy Binay | December 30, 2021[82] |

Leadership style

Duterte is known for his authoritarian leadership style, decisiveness, fiery rhetoric, and man-of-the-people persona.[83][84][85] He frequently deviates from prepared speeches and occasionally mentions humorous, controversial and outrageous remarks and expletives during his speeches,[86][87] for which his spokesperson and advisers would later interpret and clarify, sometimes through conflicting statements.[88] His erratic way of speaking has attracted concern from some observers, who stress his public statements may be misconstrued as government policy.[89][87] He has also been criticized for his sexist jokes and low tolerance for dissent.[83][84] His man-of-the-people style contributes to his popularity among many Filipinos,[84] who see in him a strict father figure, Tatay Digong (Father Digong), who instills order and discipline within the nation.[83][90][91]

Duterte has been described as a populist. He rejected being called "Your Excellency" and "His Excellency", issuing in July 2016 an order prohibiting the use of the honorific for himself and "Honorable" for his Cabinet members, in an effort to reinforce his populist and "simple" style.[92] He had an unconventional habit of chewing gum in public and wearing casual attire even on formal occasions,[93] saying he dresses for comfort, and not to impress anybody.[94] Several scholars have used the term "Dutertismo" to refer to Duterte's style of governance and the various illiberal elements and radical politics in his presidency.[95][96]

Duterte believes an "iron fist" is needed to inculcate discipline in his administration.[97] Amid the community quarantines during the COVID-19 pandemic, he asked the public for discipline in following quarantine rules as he employed the military and police in enforcing social distancing guidelines.[98]

Duterte described himself as a night person, typically starting his working day at 1:00 to 2:00 in the afternoon. He called for news conferences that begin at midnight and stressed that, "unlike others", he reads and scrutinizes piles of documents at his office before signing them.[99][100][101]

First 100 days

During his first 100 days in office, Duterte issued an executive order on freedom of information, launched an intensified campaign against illegal drugs, sought to resume peace talks with communist insurgents, formulated a comprehensive tax reform plan, led efforts to pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law, made efforts to streamline government transactions, launched the nationwide 9–1–1 rescue and 8888 complaint hotlines, established a one-stop service center for overseas Filipino workers, and increased in the combat and incentive pay of soldiers and police personnel.[102]

Duterte made moves to limit US visiting troops in the country, and has reached out to China and Russia to improve relations. He launched tirades against international critics, particularly, United States President Barack Obama, the US government, the United Nations, and the European Union, which expressed condemnation to his unprecedented war on drugs that led to the deaths of about 3,300 people, half of which were killed by unknown assailants, and the arrest of 22,000 drug suspects and surrender of about 731,000 people.[102][103]

A day after a September 2 bombing in Davao City killed 14 people in the city's central business district, Duterte declared a "state of lawlessness"; the following day, he issued Proclamation No. 55 officially declaring a "state of national emergency on account of lawless violence in Mindanao".[104]

Domestic affairs

Insurgency and terrorism

Islamic insurgency in Mindanao

Duterte was endorsed in the 2016 election by Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) leader Nur Misuari due to his background in Mindanao.[105][106] Other Muslim groups also supported Duterte and denounced Mar Roxas, President Benigno Aquino III's supported pick.[107]

Duterte stressed that Moro dignity is what the MNLF and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) are struggling for, and that they are not terrorists. He acknowledged that the Moros were subjected to wrongdoing, historical and in territory.[108] He blamed the violence on Mindanao on colonial Christianity being brought to the Philippines in 1521 by Ferdinand Magellan, saying there was peace in the nation before the colonizers arrived.[109] He blamed the United States for the bloody conflicts in the Middle East,[110] and accused the US of "importing" terrorism themselves, stressing that terrorism is not "exported" by the Middle East.[111] He cited the Bud Dajo Massacre inflicted upon the Moros while criticizing the US and President Barack Obama,[112] and while calling for the exit of American troops in September 2016.[113]

Early in his term, Duterte said federalism is the only solution to the Bangsamoro peace process. On July 8, 2016, he vowed to address the Moro conflict and bring peace in Mindanao, assuring the Filipino Muslim community that he will pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), which would establish the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region, if the proposal for the country's shift to federalism, which the MILF and the MNLF both support, fails or is not desired by the Filipino people; he added that the BBL should benefit both the MILF and MNLF, saying he is willing to negotiate with both secessionists to initiate a "reconfiguration" of territory".[114][115] On November 6, 2016, he signed an executive order expanding the Bangsamoro Transition Commission from 15 members to 21, in which 11 will be decided by the MILF and 10 will be nominated by the government; the commission was formed in December 2013 and is tasked to draft the BBL in accordance with the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro.[116]

On July 26, 2018, Duterte signed the Bangsamoro Organic Law, which abolished the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao and provided for the basic structure of government for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM),[117] following the agreements set forth in the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB) peace agreement signed in 2014 between the Government of the Philippines, under President Benigno Aquino III, and the MILF.[118] An executive order implementing the normalization program of the CAB peace agreement was signed by Duterte in April 2019, paving the way for the decommissioning of MILF forces and weapons;[119] from June 2019[120] to May 2022, a total of about 19,200 former MILF combatants and 2,100 weapons were decommissioned.[121][122] Following the clamor of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) and several Bangsamoro communities to extend the Bangsamoro transition period to allow the BTA to establish the foundations of effective autonomy, Duterte signed a law resetting the first parliamentary elections of BARMM from 2022 to 2025.[123][124]

Campaign against terrorism

The Maute group, an ISIS-inspired terrorist group, had reportedly been able to establish a stronghold in Lanao del Sur since early 2016. The group had been blamed for the 2016 Davao City bombing and two attacks in Butig, Lanao del Sur, a town located south of Marawi, in 2016.[125] Prior to Duterte's tenure, President Benigno Aquino III had downplayed the threat of ISIS in the Philippines,[126] maintaining that the Maute group during the February 2016 Butig clash were merely mercenaries wanting to be recognized by the Middle East-based terror group.[127]

In November 2016, Duterte confirmed the Maute group's affiliation with the Islamic State.[125] Amidst fierce fighting in Butig on November 30, Duterte, in a command briefing in Lanao del Sur, warned the Maute group not to force him to declare war.[128] On December 2, as the military regained control of Butig, the retreating Maute fighters reportedly left a note threatening to behead Duterte.[129]

On May 23, 2017, clashes erupted between Philippine security forces and ISIL-affiliated militants Maute and Abu Sayyaf Salafi jihadist groups in the city of Marawi during an offensive to capture Abu Sayyaf leader Isnilon Hapilon, prompting Duterte to sign Proclamation No. 216 declaring a 60-day martial law in the entire of Mindanao.[130][131][132] Maute group militants attacked Camp Ranao, occupied and set fire to several key buildings in the city[133][131] and the main street, and took a priest and several churchgoers hostage.[134] The Armed Forces of the Philippines stated that some of the terrorists were foreigners who had been in the country for a long time, offering support to the Maute group in the city, and whose main objective was to raise an ISIS flag at the Lanao del Sur Provincial Capitol and declare a wilayat or provincial ISIS territory in Lanao del Sur.[135][136] The city suffered extensive damage resulting from militant fire[137] and military airstrikes to drive the terrorists out of the urban areas.[138] On June 28, Duterte issued an administrative order creating an inter-agency task force to facilitate the rehabilitation, recovery and reconstruction efforts in the conflict-torn city.[139] Duterte declared Marawi as "liberated from terrorist influence" on October 18, a day after the deaths of militant leaders Omar Maute and Isnilon Hapilon.[137] Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana subsequently announced on October 23 that the five-month battle, the longest urban battle in the country's modern history,[140] had finally ended.[141]

Citing necessity to quell hostile activities perpetrated by terrorist groups, Congress granted Duterte's requests to extend martial law in Mindanao thrice: from July 22, 2017, to December 31, 2017;[142] from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2018;[143] and from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2019.[144] Martial law in Mindanao lapsed on January 1, 2020, after Duterte decided not to extend it.[145][146] A few days after the historic ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law on January 21, 2019,[147] a twin bombing at the Jolo Cathedral killed 20 people attending Mass; the military conducted airstrikes in Sulu against the Abu Sayyaf Group after Duterte's order to "pulverize" the terrorist group.[148] On March 18, 2020, Duterte signed an administrative order including former violent extremists as beneficiaries of the government's Enhanced Comprehensive Local Integration Program (E-CLIP).[149]

Terrorist activities continued in the country amid the COVID-19 pandemic, although the pandemic brought security forces in closer contact with the civilian population.[150][151] Following the Jolo bombings in August 2020 which killed 15 people, Duterte visited the blast site and kissed the ground to honor the lives lost,[152][153] and vowed to crush the militants.[154]

In July 2020, Duterte signed the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 which aims to give more surveillance powers to government forces to curb terror threats and acts.[155] The law has become the subject of criticisms as critics claim the legislation relaxes safeguards on human rights and is prone to abuse; authors and sponsors of the bill, on the other hand, said it is at par with the laws of other countries and will not be used against law-abiding citizens.[156]

From 2016 up to 2021, a total of 1,544 members of the Abu Sayyaf Group, 971 Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters and 1,427 Dawlah Islamiyah members had surrendered, been captured or killed by security forces.[157]

Campaign against communist insurgency

Early in his term, Duterte sought to resume peace talks with the communist rebels.[36] He directed his peace process advisor, Silvestre Bello III, to lead a government panel in resuming peace talks with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), the New People's Army (NPA), and the National Democratic Front (NDF) in Oslo, Norway, expressing hope that a peace treaty between the government and the rebel groups would be reached within a year.[158] The Duterte administration granted the temporary release of communist political prisoners who were expected to join the peace talks.[159] The first talks began on August 22–26, 2016, in which the parties agreed upon "the affirmation of previously signed agreements, the reconstitution of the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees (JASIG) which protects the rights of negotiators, consultants, staffers, security and other personnel involved in peace negotiations,[160] and the accelerated progress for negotiations".[161] Several left-leaning individuals nominated by the communist rebels were appointed by Duterte to top-government positions, which included executive departments.[162][163][36]

Relations between Duterte and the communist rebels deteriorated following continued rebel attacks on soldiers amid the peace talks.[36][164] Several officials with leftist affiliations who were initially appointed by Duterte were rejected by the Commission on Appointments; others have resigned or have been fired by Duterte.[36][164] Attacks and kidnappings of soldiers by NPA members amid the imposed ceasefire between the government and the rebels prompted Duterte to cancel all negotiations with the CPP-NPA-NDF in February 2017, designate the CPP-NPA as a terrorist organization,[8] and order the arrest of all NDF negotiators.[165] Clashes between the military and rebel groups resumed after the government and the rebels lifted the ceasefire.[166]

A task force was formed by Duterte in April 2018 to centralize all government efforts and programs for the reintegration of former communist rebels.[167][168] An executive order issued by Duterte in December 2018 created a national task force to end local communist armed conflict (NTF-ELCAC) and established a "whole-of-nation" approach in combating extremism and terrorism to address the "root causes" of communism in the country.[169] 822 barangays identified by the NTF-ELCAC as having been cleared of NPA influence have been set to receive ₱20 million worth of projects each under the Barangay Development Program.[170][171]

Duterte permanently terminated peace negotiations with the CPP-NPA-NDF in March 2019, paving the way for localized peace talks.[172][173] He cited communist terrorism as the top threat to the country's national security.[174] In June 2021, the Anti-Terrorism Council designated the National Democratic Front (NDF) as a terrorist organization, citing it as an "integral and inseparable part" of the CPP-NPA.[175][176]

Duterte threatened to bomb Lumad community schools in July 2017, maintaining that they shelter communist rebels and teach students rebellion and subversion against the government.[177] He supported the military assertion that the left-wing partylists of the Makabayan Bloc are legal fronts of the CPP, repudiating red-tagging claims by saying "We are not red-tagging you. We are identifying you as members in a grand conspiracy comprising all the legal fronts that you have organized headed by NDF and Communist Party of the Philippines".[178][179]

By the end of Duterte's term in office, NPA guerrilla fronts were significantly reduced from 89, when Duterte assumed office, to 23, while more than 25,000 "members, supporters, and sympathizers of the underground movement" were reduced to about 2,000, according to the Armed Forces of the Philippines.[180]

Defense

The Duterte administration committed to continue the 15-year modernization program of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) launched by the Arroyo administration and revived by the Benigno Aquino III administration.[181] In October 2016, the Duterte administration approved and signed the contract initiated by President Benigno Aquino III with South Korean firm Hyundai Heavy Industries for the construction of two new frigates for the Philippine Navy worth ₱15.74 billion.[182] The two missile frigates were delivered to the Philippines in May 2020 and February 2021,[183][184] and were officially commissioned in July 2020 as BRP Jose Rizal (FF-150), the country's first missile-capable frigate, and in March 2021 as BRP Antonio Luna (FF-151), respectively.[185][186]

On June 20, 2018, Duterte approved the shopping list of Horizon 2, the second phase of the Revised AFP Modernization Program, which was to be implemented from 2018 to 2022, with a budget of about ₱300 billion.[187][188] The Duterte administration made its largest military aircraft acquisition contract in February 2022, after signing a 32 billion-peso deal to purchase 32 additional S-70i "Black Hawk" combat utility helicopters from PZL Mielec of Poland.[189][190]

To prevent the "revolving door" system and create excellence in leadership in the AFP, Duterte, in April 2022, signed a law granting the chief of staff and other senior military officers of the AFP a fixed three-year term, unless sooner terminated by the President. The law also allows the President to extend the term "in times of war or other national emergency declared by Congress".[191]

By Duterte's last month in office, 54 projects under the AFP Modernization Act and Revised AFP Modernization Act have been completed.[192]

Crime

Duterte campaigned to bring law and order to the country.[193] Following Duterte's order of a crackdown against loiterers (tambays), whom he described as "potential trouble for the public", the Philippine National Police (PNP) on June 13, 2018, launched Oplan Tambay or "Rid the Streets of Drunkards and Youths" (Oplan RODY), an anti-criminality campaign meant to enforce city and municipal ordinances, such as those against drinking, gambling in streets, urinating in public, roaming half-naked, making too much noise,[194][195] and minors violating the curfew.[196] On June 21, records showed that 7,291 loiterers and vagrants in Metro Manila were arrested by the police just 9 days after the Oplan RODY campaign was launched.[197] Concerns about the campaign arose following the death of 22-year-old Genesis "Tisoy" Argoncillo while in detention, who was arrested and jailed for allegedly causing alarm and scandal;[198] two inmates who allegedly mauled Argoncillo have been charged for murder.[199] On June 25, Senator Bam Aquino and the Makabayan Bloc filed resolutions pushing for an investigation into what they call anti-poor arrests of thousands of loiterers.[200] Duterte maintained that he did not order the arrests of tambays.[195] PNP Director General Oscar Albayalde denounced critics for allegedly conditioning the minds of the public that rights are being violated in the intensified campaign,[197] and stressed that those arrested had violated local ordinances, which included smoking in public, being half-naked, and karaoke singing past 10 p.m.[195][201]

In October 2016, Duterte signed an administrative order creating the Presidential Task Force Against Media Killings (later renamed Presidential Task Force on Media Security)[202] to ensure a safe environment for media workers and the speedy probe of new cases on media killings.[203] In April 2022, he signed a law creating the Office of the Judiciary Marshals tasked to ensure the security and protection of the judiciary members, officials, personnel, and property.[204] In an effort to address law and order and shortage of prosecutors in the country, he appointed, during his tenure, at least 1,700 new prosecutors, the most number of appointments in any previous presidency, in the National Prosecution Service.[205]

Duterte made efforts to strengthen border control, issuing an executive order mandating the adoption and implementation of an Advance Passenger Information System, effectively requiring commercial carriers to submit to the Bureau of Immigration their passengers' information prior to departure to or arrival from the Philippines.[206] In June 2022, he signed a law strengthening the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act, giving authorities additional tools for pursuing human traffickers whose violations involve the internet and digital platforms.[207] A law he signed in May 2022 eased gun application requirements for persons considered to be in imminent danger; the law also extended the validity of firearms license from two years to five to 10 years, at the option of the licensee.[208][209]

Duterte denounced hazing,[210] signing into law the Anti-Hazing Act of 2018, which prohibited all forms of hazing in fraternities, sororities, and organizations in schools;[211] however, he said hazing would be difficult to stop unless fraternities were banned.[212] The Safe Spaces Act signed into law in April 2019 imposed heftier penalties for gender-based sexual harassment including wolf-whistling and catcalling in public spaces.[213][214] Through laws signed by Duterte, protection of consumers against fraud committed through financial services was strengthened,[215] and Timbangan ng Bayan centers were mandated to be established in all markets and supermarkets nationwide to protect consumers from unfair practices by assisting them in accurately checking the weight and quantity of goods they purchase.[216]

Except for killings related to the war on drugs during his early presidency, crime rate significantly dropped under Duterte's watch.[217][218] In October 2021, the PNP reported that the total number of crimes in the country dropped by 49.6 percent over the past 63 months since July 2016; police data showed that from 2.67 million crimes reported from 2010 to 2015, it went down to 1.36 million from 2016 to September 2021.[219]

War on Drugs

During his presidential campaign, Duterte cautioned that the Philippines was at risk of becoming a narco-state and vowed the fight against illegal drugs will be relentless.[220] In early July 2016, a few days after his inauguration, he launched the War on Drugs; the Oplan Tokhang, a house-to-house campaign inviting identified drug suspects to surrender themselves, was launched by Philippine National Police (PNP) shortly after.[221] Duterte presented a chart identifying three Chinese nationals who serve as drug lords in the Philippines.[222] On August 7, he disclosed the names of about 150 public officials, including mayors, congressmen, legislators, police, military and judges, reportedly involved in illegal drug trades.[223]

At the height of the anti-drugs campaign, Duterte issued controversial public statements urging the public and communists to kill drug dealers;[224] he also encouraged police during anti-drug raids to "shoot first" if their lives were in imminent danger[225] and that he would grant them pardon if they are criminally convicted in the discharge of their anti-drug related duties.[226] Thousands of drug personalities and users surrendered to the police for fear of their lives, overwhelming the administration and prompting them to build more rehabilitation centers.[221][103] Concerns about the implementation of the anti-drugs campaign arose after the growing number of deaths of drug suspects during anti-illegal drug police operations were reported by the local media,[227] attracting international attention and prompting the United States, the European Union, the United Nations, human rights watchdogs, and opposition groups to condemn the extrajudicial killings which were presumed to be state-sanctioned.[103][228][229][230] In August 2016, opposition Senator and Duterte's staunch critic Leila de Lima launched a Senate probe into reported extrajudicial killings amid the anti-drug campaign, presenting Edgar Matobato, a self-confessed hitman of the alleged vigilante group Davao Death Squad (DDS), as witness.[231] Matobato testified that Duterte, then mayor of Davao City, was involved in extrajudicial killings in the City; Duterte dismissed the allegation as a "lie".[232] The Senate terminated its probe on October 13, 2016, after finding insufficient evidence on the claim that Duterte ordered the killings allegedly committed by the DDS.[233]

An Inter-agency Committee on Anti-illegal Drugs (ICAD), composed of 21 government agencies and headed by the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), was formed in March 2017 by Duterte to lead the fight against illegal drugs.[234] In April 2017, the lawyer of Matobato, Jude Josue Sabio, filed a 77-page complaint before the International Criminal Court (ICC) against Duterte and 11 other officials for alleged crimes against humanity amid the nationwide anti-drug campaign.[235]

In October 2017, amid public outrage over alleged police abuse in the continuing crackdown, Duterte prohibited the PNP from joining anti-drug raids and designated the PDEA as the "sole agency" in charge of the war on drugs.[236] A recovery and wellness program for drug dependents was launched by the PNP in the same month.[237][238] The PNP was allowed back to join the campaign in December 2017, with the PDEA still being the lead agency.[239] In October 2018, Duterte signed an executive order institutionalizing the Philippine Anti-Illegal Drugs Strategy, which prescribes a more balanced government approach in the fight against illegal drugs by directing all government departments and agencies, government-owned and controlled corporations, and state universities and colleges to craft their own plans relative to the strategy.[240]

As early as November 2016, Duterte signaled his intention to withdraw the Philippines from the ICC, which he described as "useless", after an ICC prosecutor said the ICC may have authority to prosecute the perpetrators of the drug war deaths.[241] In March 2018, the Philippines withdrew from the ICC after the tribunal's chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda in February 2018 launched a preliminary examination into crimes against humanity allegedly committed by Duterte and other top officials of the war on drugs;[242] the withdrawal took effect exactly a year later, on March 17, 2019.[243] On September 16, 2021, the ICC authorized a formal investigation into the war on drugs,[244] focusing on crimes committed when Duterte took office in 2016 until March 2019.[245] A deferral of the probe was requested by the Philippine government via a letter sent to ICC prosecutor Karim Khan in November 2021, informing the ICC that local authorities are conducting thorough investigations of all reported deaths during anti-narcotic operations in the country; the ICC suspended its investigation in December 2021 to assess the scope and effect of the deferral request.[246] On June 26, 2022, a few days before Duterte's term in office ended, Khan concluded that the deferral request by the Philippine government is "not warranted" on the basis that "majority of the information provided by the Philippine Government relates to administrative and other non-penal processes and proceedings which do not seek to establish criminal responsibility"; he requested the pre-trial chamber I of the ICC to immediately resume the investigation.[247]

Duterte has since acknowledged underestimating the gravity of the illegal drug problem when he promised to rid the country of illegal drugs within six months of his presidency, citing the difficulty in border control against illegal drugs due to the country's long coastline and lamenting that government officials and law enforcers themselves were involved in the drug trade.[248] Toward the end of his term, he accepted the possible retaliation from drug syndicates and said that he gains nothing from the drug war but hate.[249] He asked president-elect Bongbong Marcos to continue the war on illegal drugs in Marcos' own way, to protect the youth,[250] but declined the possibility of being appointed as Marcos' drug czar, saying he is looking forward to his retirement, and said he might find a way to address the drug problem as a civilian.[251]

Part of the Duterte administration's strategy on anti-illegal drugs is the Barangay Drug Clearing Program, which aims to eradicate illegal drugs in the country's remaining drug-affected barangays.[252] By February 2022, the PDEA reported that a total of 24,379 (58%) out of the 42,045 barangays have been declared drug-cleared, 6,606 (16%) barangays were drug unaffected/drug-free, while 11,060 (26%) have yet to be cleared of illegal drugs.[6] 783,005 drug surrenderees have undergone the PNP's recovery and wellness program by October 2021.[253]

The war on drugs retained majority support among Filipinos throughout Duterte's six-year tenure in office.[254][255][256]

Support for death penalty

Duterte campaigned to restore death penalty in the country, preferrably by hanging, for criminals involved in illegal drugs, gun-for-hire syndicates and those who commit "heinous crimes" such as rape, robbery or car theft where the victim is murdered;[257][258] Duterte theatrically vowed "to litter Manila Bay with the bodies of criminals".[259]

In December 2016, the bill to resume capital punishment for certain "heinous offenses" swiftly passed out of Committee in the House of Representatives; it passed the full House of Representatives in February 2017.[260] On March 7, despite fierce criticism, especially from the Catholic Church, the House of Representatives approved on 3rd and final reading the controversial bill.[261] However, the law reinstating the death penalty stalled in the Senate in April 2017, where it did not appear to have enough votes to pass.[262][263]

Presidential pardons and amnesty

Early in his term, Duterte pardoned several communist rebels and political prisoners as part of pursuing peace talks with the communists.[264][265] He granted pardon to elderly and sickly prisoners,[266] and to Philippine Military Academy and Philippine National Police Academy upperclassmen and graduating cadets with outstanding punishments and demerits.[267][268] In November 2016, upon the recommendation of the Board of Parole, which is under the Department of Justice, he granted absolute pardon to actor Robin Padilla, who was convicted for illegal possession of firearms in 1994.[269]

In August 2018, Duterte signed a proclamation revoking the amnesty of his staunch critic, Senator Antonio Trillanes; Duterte stressed that the amnesty, which was granted in 2010 by President Benigno Aquino III, was void ab initio as Trillanes did not apply for amnesty and failed to admit guilt for his roles in the 2003 Oakwood Mutiny and the 2007 Manila Peninsula siege.[270][271]

Following an Olongapo local court ruling ordering the early release of convicted murderer US Lance Corporal Joseph Scott Pemberton as he had shown good behavior while in prison and therefore served an equivalent of his maximum 10-year sentence, Duterte, on September 7, 2020, granted absolute pardon to Pemberton, who served less than six years in prison for killing Filipino transgender woman Jennifer Laude in 2014.[272]

In February 2021, Duterte signed an executive order creating the National Amnesty Commission tasked to process applications for amnesty of former rebels and determine those who are eligible.[273] He signed four proclamations granting amnesty to members of the Moro National Liberation Front, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the communist movement, and the Rebolusyonaryong Partido ng Manggagawa ng Pilipinas/Revolutionary Proletarian Army/Alex Boncayao Brigade (RPMP-RPA-ABB).[274]

Anti-corruption

Describing corruption in the government as "endemic",[275] Duterte prioritized its eradication during his tenure.[276] A few weeks after assuming office, he signed the Freedom of Information executive order,[277] allowing the public to obtain documents and records from the executive branch in an effort to promote government transparency.[278][276] In October 2017, he ordered the creation of an anti-corruption agency tasked to eliminate corruption and red tape in the executive department.[279] The 8888 Citizens' Complaint Hotline was institutionalized in October 2016 through an executive order, allowing the public to report complaints on poor government front-line services and corrupt practices in government agencies;[280] the hotline was expanded in November 2020 to allow complaints to be sent via text message free of charge.[281]

Duterte took steps to streamline government processes,[282] ordering government agencies to remove all processes deemed as "redundant or burdensome" to the public.[283] The Ease of Doing Business Act signed into law in May 2018 aimed to reduce processing time, cut bureaucratic red tape, and eliminate corrupt practices to create a better business environment;[284] the law also created the Anti-Red Tape Authority (ARTA).[285] An online one-stop shop for business registration, the Central Business Portal, was launched by the government in January 2021 to expedite and streamline the business registration process and lower its duration from 33 days to less than a day.[286] Duterte created the Office of the Presidential Adviser on Streamlining of Government Processes tasked to recommend to the President or to the ARTA policies and programs that would cut red tape in the executive branch and local government units.[287] A law he signed in December 2020 authorized the President to expedite the processing and issuance of national and local permits, licenses, and certifications, by suspending its requirements, in times of national emergency.[288]

Duterte had a policy to destroy smuggled luxury vehicles to discourage smugglers.[289][290] In March 2019, he signed a law abolishing the graft-ridden Road Board, stressing that the agency was "nothing but a depository of money and for corruption."[291][292]

Amid the corruption allegations within the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth), Duterte, in August 2020, issued a memorandum directing the Department of Justice (DOJ) to create a task force that will investigate the widespread corruption and irregularities within the PhilHealth.[293] On October 27, he ordered the DOJ and a newly created mega-task-force to investigate allegations of corruption in the entire government.[294]

Federalism and constitutional reform

Duterte advocates federalism as a better system of governance for the Philippines, arguing that regions outside Metro Manila receive unfairly small budgets from the Internal Revenue Allotment. He also highlights that money remitted to national government is misused by corrupt politicians in the Philippine Congress.[295] He expressed his willingness to end his term early once federalism is passed.[296]

On December 7, 2016, Duterte signed an executive order creating a 25-member Consultative Committee tasked to review the 1987 Constitution within six months.[297] On January 23, 2018, he appointed members of the Consultative Committee comprising Justices, ex-legislators, lawyers, academics, and other experts, with former Chief Justice Reynato Puno as chairman. The Consultative Committee held its first session on February 19. On July 3, the Consultative Committee unanimously approved a federal charter, which includes provisions on a ban on political dynasties, political turncoatism, and monopolies and oligopolies; the charter also included provisions on additional powers for the Ombudsman and Commission on Audit. Duterte approved the Consultative Committee's draft federal Constitution and said he will endorse it to the Congress.[298] However, on October 8, the House Committee on Constitutional Amendments approved and recommended the adoption of a new draft federal Constitution filed by House Speaker Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and 21 other lawmakers, which was heavily criticized by the Consultative Committee and the public as Arroyo's draft deleted several key provisions of the original version which include safeguards against political dynasties, turncoatism, and federated regions; Arroyo's draft was also denounced as it removed term limits of Congress members and removed the vice president from the presidential line of succession.[299] Duterte, meanwhile, on November 5, formed an inter-agency task force to raise public awareness on the proposed federal system of government, after poll results showed it is the least of Filipinos' concerns.[300] On December 11, the House of Representatives passed on third and final reading Arroyo's draft federal charter, Resolution of Both Houses No. 15, but the Senate rejected it.[301][302]

Since June 2019, after several issues continued to surround Arroyo's draft charter, Duterte acknowledged that federalism may not be established in his remaining time.[299] On December 10, 2021, months before leaving office, Duterte, at a democracy summit hosted by US President Joe Biden, admitted that he failed in his push to establish a federal system of government in the country, citing the lack of congressional support for his campaign promise.[303][304]

"My government also sought to broaden democratic participation through federalism but my constitutional project did not get Congress support. So be it. I respect the separation of powers [that is] vital for democracy."

Early in his term, in 2017, Duterte raised the idea of setting up a revolutionary government as a way for the country to make real progress[305] and to prevent chaos from ruling the streets if the opposition attempts to oust him as president,[306] but later rejected calls for its establishment.[307][308] He criticized and called for the abolition of the party-list system,[309][310] which he described as "evil",[311] citing the system no longer represented the marginalized as it has been infiltrated and exploited by communist legal fronts and the country's elite.[312][313]

On June 1, 2021, Duterte issued an executive order directing the devolution of some functions of the executive branch to local governments.[314]

Agriculture

The Duterte administration inherited from the Benigno Aquino III administration a neglected and declining agricultural sector.[315] In Duterte's first year, in 2017, agriculture recovered with a 6.3 percent growth from a 2.0 percent decline in the previous year.[316] Despite the growth in the country's other economic sectors during Duterte's presidency, the Duterte administration struggled to revive the farm sector,[317] which had seen a steady decline over the past decades,[318] leaving the agriculture industry in a fragile state.[317]

Inflation in 2018 caused by spikes in rice prices prompted Duterte to urge Congress to replace rice import limits with a system of tariffs.[319] The Rice Tariffication Law (RTL) enacted in February 2019 ended the rice importation monopoly of the National Food Authority[320][321] by replacing quantitative restrictions on rice imports with a 35% import tariff in an effort to stabilize rice prices for consumers.[322][323] Revenue from the import tariffs were earmarked for a Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) to be used in supporting domestic farmers affected by the RTL improve their productivity.[323] Following its passage, the RTL received vehement criticism and opposition from leftist groups,[324] members of Congress, farmers groups, and some academia members,[325] while gaining support from business groups.[326] Palay and retail rice prices eventually dropped,[327] and rice prices stabilized despite the COVID-19 pandemic and successive typhoons.[322] A law signed by Duterte in 2019 authorized the Department of Agriculture to use any funds exceeding the ₱10 billion annual rice import tariff revenues to provide annual cash assistance until 2024 to small farmers tilling 2 hectares (4.9 acres) and below of rice land.[328]

Commonwealth-era restrictions on agricultural free patents issued to farmers were eased, allowing agricultural land titles to be immediately available for trade.[329] The Sagip Saka Act signed into law in April 2019 promoted enterprise development for farmers and fishermen to boost their income,[330] and strengthened direct purchase of agricultural goods from farmers, eliminating the need for middlemen.[331] Certification of organic produce by farmers and fishermen was made more accessible and affordable.[332][333] An administrative order signed by Duterte in 2020 awarded qualified fresh graduates of agricultural degrees at most 3 hectares (7.4 acres) of land in an effort to prevent shortage of farmers by encouraging the youth to venture into agriculture.[334][335]

Free irrigation for farmers owning not more than 8 hectares (20 acres) of land was signed into law by Duterte in February 2018,[336] benefiting about 1.033 million farmers tilling 1.189 million hectares (11,890 km2) of agricultural land by December 2021.[337] A law signed in February 2021 created a trust fund for the country's coconut farmers;[338] the law was complemented by an executive order issued by Duterte in June 2022 which implemented the Coconut Farmers and Industry Development Plan, paving the way for the release of the ₱75 billion trust fund for coconut farmers consisting of coco levy assets declared state property by the Supreme Court.[339][340]

In 2019, the African swine fever reached the Philippines and caused an outbreak, prompting the government to tighten animal quarantine and ban imported pork from several countries.[341] More than 3 million hogs were culled from 2020 to 2021, causing a huge supply deficit in pork and a rise in domestic pork price. Duterte issued an executive order temporarily lowering tariffs on imported pork meat for one year;[342] the order reduced tariff rates for imported pork meat to a range between 5% to 20% from the current range of 30% to 40%.[343] Hog population significantly increased after the administration initiated a massive repopulation program to boost domestic pork supply.[344] On May 10, 2021, Duterte issued a proclamation declaring a one-year nationwide state of calamity due to the continued spread of the disease despite government interventions.[345]

By July 2021, a total of 2,025 kilometres (1,258 mi) farm-to-market roads, and 94.99 kilometres (59.02 mi) farm-to-mill roads have been completed by the Duterte administration under the Build! Build! Build! program.[346]

Disaster resilience

Since 2017,[347][348] Duterte called on Congress to pass a bill creating the Department of Disaster Resilience, a department dedicated to disaster response and rehabilitation efforts. The bill has been approved by the House of Representatives, but has faced opposition by some senators, who see the bill as bloating the already "bloated" bureaucracy.[349]

In July 2019, Duterte approved the Department of Science and Technology-led GeoRisk PH, a multi-agency government initiative to serve as the central resource of natural hazards and risk assessment information in the country through web applications.[350][351]

Following the 2020 Taal Volcano eruption, Duterte called for the construction of more evacuation centers in areas prone to disasters.[352] In April 2022, the government inaugurated three evacuation centers in Batangas province strategically located outside the 14-kilometre (8.7 mi) Taal Volcano danger zone.[353] By July 2021, 223 new evacuation centers under the Build! Build! Build! program had been constructed.[354]

After typhoons Rolly and Ulysses ravaged the country, Duterte issued an executive order in November 2020 creating the Build Back Better Task Force, a permanent inter-agency body assigned to streamline and hasten post-disaster rehabilitation and recovery efforts of typhoon-affected areas.[355]

In September 2021, Duterte signed the BFP Modernization Act, mandating the implementation of a 10-year program to modernize the Bureau of Fire Protection; the law also expanded the bureau's mandate by including disaster risk response, and emergency management.[356]

Economy

| Year | Quarter | Growth rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2016[357] | 1st | 6.9% |

| 2nd | 7.4% | |

| 3rd | 7.3% | |

| 4th | 6.9% | |

| 2017[357] | 1st | 6.4% |

| 2nd | 7.2% | |

| 3rd | 7.5% | |

| 4th | 6.6% | |

| 2018[357] | 1st | 6.5% |

| 2nd | 6.4% | |

| 3rd | 6.1% | |

| 4th | 6.4% | |

| 2019[358] | 1st | 5.9% |

| 2nd | 5.6% | |

| 3rd | 6.3% | |

| 4th | 6.6% | |

| 2020[358] | 1st | -0.7% |

| 2nd | -16.9% | |

| 3rd | -11.6% | |

| 4th | -8.2% | |

| 2021[358] | 1st | -3.8% |

| 2nd | 12.1% | |

| 3rd | 7.0% | |

| 4th | 7.8% | |

| 2022[358] | 1st | 8.2% |

| 2nd | 7.4% |

Duterte inherited from the Aquino administration both a strong economy and a poor performance in public infrastructure investment.[359][360] He vowed to continue Aquino's macroeconomic policies while increasing infrastructure spending, through his economic team's 10-point socioeconomic agenda.[361][362][363] Early in his term, his expletive-laden outbursts triggered the biggest exodus from stocks in a year and made the Philippine peso Asia's worst performer in September 2016,[364] although the Philippine economy posted the strongest growth in Asia at 7.1% in the third quarter of 2016.[365]

The Duterte administration sought to attract more investors by easing restrictions on international retailers.[366] In February 2019, Duterte signed a law updating the 38-year-old Corporation Code of the Philippines, allowing a single person to form a corporation.[367] In March 2022, he signed into laws Republic Act No. 11647, which amended the Foreign Investment Act of 1991, effectively relaxing several restrictions on foreign investments;[368] and Republic Act No. 11659, which amended the 85-year old Public Service Act, effectively allowing full foreign ownership of public services which include airports, expressways, railways, telecommunications, and shipping industries in the country.[369]

Following the devastation of Typhoon Ompong to agriculture in September 2018, the inflation rate of the country soared to 6.7%, its highest in 9 years.[370][371] On September 21, 2018, Duterte signed Administrative Order No. 13, removing non-tariff barriers in the importation of agricultural products, to address soaring inflation rates.[372][373] Inflation decreased in November 2018, at 5.8 to 6.6 percent.[374] BSP decreased its inflation forecast for 2019, after the passage of the rice tariffication bill.[375] Inflation further decreased from 6.7 percent in October 2018 to 0.8 percent in October 2019, the lowest inflation rate recorded since May 2016.[376]

The Duterte administration made initiatives to support micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).[377] In January 2017, the Department of Trade and Industry launched the Pondo sa Pagbabago at Pag-asenso Program (P3), a microfinancing program to assist MSMEs and provide them an alternative to resorting to loan sharks and the usurious "5-6" lending scheme;[378][379] the P3, which charged only 2 to 2.5 percent interest per month compared to the 20% interest rate in the "5-6" lending scheme, allowed MSMEs to borrow an amount of ₱5,000 to ₱100,000.[378] The administration also increased nationwide the number of Negosyo Centers, which provide efficient services for MSMEs;[380] by August 2021, 996 of these centers have been established since 2016, out of a total of 1,212.[381]

After several reforms such as Ease of Doing Business Law[284] were introduced, the Philippines' ease of doing business ranking improved from 124th to 95th, and the country's overall ease of doing business score rose to 62.8, according to the World Bank's 2020 Doing Business Report.[382]

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic reached the country and caused the economy to enter a recession following government lockdowns and restrictions to contain the virus. Gross domestic product (GDP) shrunk by 9.5% in 2020,[9] prompting the administration to further loosen restrictions to revive the economy.[383] GDP recovered to 5.6% in 2021 after the administration initiated a nationwide vaccination drive and eased pandemic-related restrictions,[10][384] while the country's debt-to-GDP ratio soared from 39.6% in pre-pandemic 2020 to 60.4% as of end-June 2021 due to loans incurred by the government to address the pandemic.[385]

On March 21, 2022, Duterte signed an executive order adopting a 10-point policy agenda to hasten economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.[386] To reduce the country's debt, which rose to ₱12.68 trillion as of March 2022, the Duterte administration's economic team proposed in May 2022 to the incoming Marcos administration a fiscal consolidation plan containing corrective tax measures, which include the expansion of value-added tax to raise government revenues.[387] By the second quarter of 2022, the Philippine economy had grown by 7.4%, making the country the second-fastest growing economy in Southeast Asia.[388]

Infrastructure development

To reduce poverty, encourage economic growth, and reduce congestion in Metro Manila, the Duterte administration launched its comprehensive infrastructure program, Build, Build, Build,[390] on April 18, 2017.[391] The program, which forms part of the administration's socioeconomic policy,[390] aimed to usher in the country's "Golden Age of Infrastructure" by increasing the share of spending on public infrastructure in the country's gross domestic product (GDP) from 5.4 percent in 2017 to 7.4 percent in 2022.[392][393] The administration, in 2017, shifted its infrastructure funding policy from public-private partnerships (PPPs) of previous administrations to government revenues and official development assistance (ODA), particularly from Japan and China,[394] but has since October 2019 engaged with the private sector for additional funding.[395][396]

The administration revised its list of Infrastructure Flagship Projects (IFPs) under the Build, Build, Build program from 75 to 100 in November 2019,[397][398] then to 104, and finally, to 112 in 2020,[399] expanding its scope to include health, information and communications technology, and water infrastructure projects to support the country's economic growth and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Some major projects include[398] the Subic-Clark Railway,[400] the North–South Commuter Railway from New Clark City to Calamba, Laguna,[400] the Metro Manila Subway,[401] the expansion of Clark International Airport[400] the Mindanao Railway (Tagum-Davao-Digos Segment),[402] and the Luzon Spine Expressway Network[403][404] By April 2022, 12 IFPs have been completed by the administration, while 88 IFPs, which were on their "advanced stage", have been passed on to the succeeding administration for completion.[399]

From June 2016 to July 2021, a total of 29,264 kilometres (18,184 mi) of roads, 5,950 bridges, 11,340 flood control projects, 222 evacuation centers, and 150,149 elementary and secondary classrooms, and 653 COVID-19 facilities under the Build, Build, Build program had been completed.[405][406]Taxation

The Duterte administration initiated a comprehensive tax reform program to make the country's tax system simpler, fairer, and more efficient.[407] The first package of the program, the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion Law (TRAIN Law), adjusted tax rates by excluding those earning an annual taxable income of ₱250,000 from paying personal income tax; the law conversely raised excise taxes on vehicles, sugar-sweetened beverages, petroleum products, tobacco and non-essential goods to generate funds for the administration's massive infrastructure program.[408][409] The second package, the Corporate Recovery and Tax Incentives for Enterprises Act (CREATE Act), lowered corporate income tax from 30% to 25% to attract more investments and maintain fiscal stability.[410] Sin taxes on tobacco and vapor products, as well as alcohol beverages and electronic cigarettes, were raised to fund the Universal Health Care Act and reduce incidents of diseases associated with smoking and alcohol consumption.[411][412] A tax amnesty signed into law by Duterte in February 2019 granted errant taxpayers a one-time opportunity to affordably settle their tax liabilities while raising government revenue for infrastructure and social projects.[413]

Duterte signed a law imposing 5% tax on gross gaming revenues of Philippine offshore gaming operators.[414] In March 2019, he signed a law excluding small-scale miners from paying income and excise taxes for gold they sell to the central bank.[415]

Trade

On September 2, 2021, Duterte ratified the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement, an ASEAN-led free trade agreement involving 10 ASEAN members and Australia, China, Japan, Korea, and New Zealand; the agreement was sent to the Senate for its concurrence, but its ratification has been delayed after the Senate adjourned sessions for the May 2022 election break.[416] In June 2022, the Senate deferred the agreement's ratification to the incoming 19th Congress after some senators raised concerns over the lack of safeguards for the country's agricultural sector, and following president-elect Bongbong Marcos' pronouncement of intending to review the agreement.[417]

Education and research

Stressing that the long-term effects of education would outweigh any budgetary problems, Duterte signed in August 2017 a landmark law granting free tuition on all state universities and colleges (SUCs), after his economic managers earlier opposed the bill.[418][419] He signed a law in February 2019 mandating free access to technical-vocational education to address unemployment and job mismatch in the country. Medical scholarships for deserving students in SUCs and private higher education institutions (HEIs) was enacted through the Doktor Para sa Bayan Act.[420] A law signed in April 2022 aimed to improve the quality of teacher education and established a scholarship program for students pursuing teacher education degree programs.[421][422] To assist students in pursuing a proper college education, a career guidance and counseling program for all secondary schools nationwide was established through a law signed by Duterte in February 2019.[423]

Good Manners and Right Conduct (GMRC) and Values Education were restored as core subjects in the K-12 curriculum in all public and private schools.[424] Transnational higher education was established in the country through a law signed in August 2019, allowing foreign universities to offer degree programs in the Philippines in an effort to modernize the higher education sector and bring expertise into the country.[425][426] A law signed in May 2021 integrated labor education into the higher education curriculum;[427] another law enacted in August 2019 required the creation of an advanced energy and green building technologies curriculum for both undergraduate and graduate students.[428]

Duterte signed a law institutionalizing the alternative learning system (ALS), which provides a parallel learning system for non-formal sources of knowledge and skills,[429] and provides free education to those out of school.[430] A law he signed in March 2022 granted inclusive education for learners with disabilities.[431] Filipino Sign Language was declared the national sign language of the Filipino deaf and was required to be taught as a separate subject in the curriculum for deaf learners.[432]

Duterte enacted a law in June 2020 establishing the country's first National Academy of Sports in New Clark City, Capas, Tarlac.[433] In June 2022, he led the groundbreaking ceremony of the Philippine Sports Training Center in Bagac, Bataan, urging the next administration to build more sports facilities to help improve Filipino athletes.[434]

In an effort to boost research and development in the country, Duterte signed in June 2018 the Balik Scientist Act, providing incentives to Filipino scientists abroad to motivate them to return to the country and share their expertise.[435]

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in mid-2020, Duterte rejected the resumption of face-to-face classes in COVID-19 low-risk areas until vaccines became available in the country,[436] stressing he will not risk putting the lives of students and teachers in danger.[437] On October 5, 2020, the Department of Education reopened classes after months of closure due to the pandemic, implementing distance or blended learning which involve a mix of modular learning, online learning, and TV and radio broadcasts.[438][439] Duterte approved in September 2021 a two-month pilot testing of limited face-to-face classes in COVID-19 low-risk areas;[440] in January 2022, he approved the education department's proposal to expand face-to-face classes.[441]

By the end of Duterte's term, 1.97 million students across 220 HEIs were granted free tuition from the academic years (AY) 2018-2019 up until AY 2021-2022, while 364,168 grantees availed of tertiary education subsidies and benefits from the administration's Tulong Dunong Program in the same period.[442]

Energy

The Duterte administration adopted a "technology neutral" approach and included renewable sources of energy such as hydroelectric, geothermal, wind, and solar in the power producing mix.[443] Early in Duterte's term, the administration maintained that coal remains the most viable source of energy if the Philippines is to accelerate industrialization;[444] Duterte questioned the sanctions imposed by the United States and European Union on smaller countries, including the Philippines, when the country's carbon footprint is not significant compared to those of the superpowers.[445]

The administration pursued policies for the country to transition to renewable energy as a source of power.[446] At his fourth State of the Nation address in July 2019, Duterte issued a directive to cut coal dependence and fast-track a transition to renewable energy.[447][448] In August 2017, Duterte inaugurated the first Filipino solar module manufacturing facility at Santo Tomas, Batangas, owned by renewable energy firm Solar Philippines.[449] In a shift in the administration's energy neutrality policy, the energy department, in October 2020, issued a moratorium on the construction of new coal power plants, effectively favoring renewable energy sources.[450]

To hasten the expansion of the nation's power capacity, Duterte signed an order on June 28, 2017, establishing the inter-agency Energy Investment Coordinating Council tasked with simplifying and streamlining the approval process of big-ticket projects.[443] In January 2022, he signed a law promoting the use of microgrid systems in unserved and underserved areas to accelerate total electrification of the country.[451]

The administration sought new energy sources.[446] With the impending depletion of the Malampaya gas field, Duterte, on October 15, 2020, approved the Department of Energy's recommendation to lift the moratorium on oil and gas exploration in the West Philippine Sea imposed by President Benigno Aquino III in 2012.[452] The administration's energy department partnered with Australian company Star Scientific Ltd. and Japanese company Hydrogen Technology Inc. (HTI) to study hydrogen as a possible energy source.[453][454] On February 28, 2022, Duterte signed an executive order approving the inclusion of nuclear power in the country's energy mix.[455][456]

The administration pursued to liberalize the energy sector.[446][457] In October 2020, Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi confirmed that the Philippines started allowing 100% foreign ownership in large-scale geothermal projects.[458][459]

The energy department reported in September 2021 that the country's system capacity increased from 21,424 megawatts in 2016 to 26,287 megawatts in 2020, and household electrification level rose from 90.7% in 2016 to 94.5% in 2020.[460]

Environment

Duterte signed the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in March 2017, after initially having misgivings about the deal which he says might limit the country's industrialization;[461] the Agreement was ratified by the Senate on March 15, 2017.[462] Duterte said that rich countries producing the most carbon emissions should pay developing nations for the damage caused by climate change.[463]

In March 2018, Duterte issued a presidential proclamation declaring parts of the Philippine Rise, which the United Nations ruled as part of the country's exclusive economic zone, as a marine protected area.[464] The E-NIPAS Act of 2018, a landmark legislation he signed in June 2018, protected an additional 94 critical habitats nationwide and declared them as national parks, effectively increasing the number of protected areas in the country from 13 to 107 covering a total of 3 million hectares (30,000 km2).[465][466] In April 2022, he signed laws declaring Mount Pulag, Mount Arayat, Tirad Pass, and two other areas as protected landscapes under the National Integrated Protected Areas System.[467]

Diplomatic tensions between the Philippines and Canada concerning trash briefly escalated between April and May 2019 when Duterte ordered officials to immediately return to Canada several shipping containers containing tons of household garbage Canada sent to the Philippines in 2013 and 2014, many of such containers remained idle for years in the town of Capas, Tarlac. The Canadian government agreed to repatriate the trash but maintained that the trash, which was falsely labelled as recyclable plastics, was done by a private company without their consent.[468] Duterte recalled the Philippine ambassador to Canada and other diplomats after Canada missed the May 15 deadline to retrieve the garbage; Duterte also threatened to declare war on Canada or personally "sail to Canada and dump their garbage there". On May 31, 2019, 69 containers of Canadian refuse were loaded onto a vessel and transported from Subic Bay to the city of Vancouver, Canada.[469][470]

In May 2021, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), led by environment secretary Roy Cimatu, completed the closure, which began since 2017, of all 335 open dumpsites nationwide.[471] Local government units were subsequently required by the DENR to rehabilitate the dumpsites into sanitary landfills.[472]

Mining

In May 2016, Duterte offered staunch environmental activist Gina Lopez to be the environment secretary of his administration. Gina accepted the offer, and was later reappointed by Duterte after she was bypassed by the Commission on Appointments (CA) and highly criticized following her decision to close down 23 mining operations in functional watersheds and suspend six others in February 2017.[473][474][475] Duterte, who has expressed support for Lopez, said that there was nothing he could do about the closures.[476] On May 9, Duterte appointed former military chief Roy Cimatu as the new environment secretary,[477] after the CA rejected Lopez's appointment as environment secretary in a vote of 8–16 on May 3, amid issues over her order to close and suspend mining operations.[475][478] The Chamber of Mines of the Philippines, which vehemently opposed Lopez's appointment,[475] welcomed the appointment of Cimatu and expressed hope that Cimatu would take a more balanced approach to the job.[477] In July 2018, Duterte floated a "conspiracy" behind Congress' decision in May 2017 to reject Lopez's appointment as environment secretary.[479]

Duterte initially threatened to ban open-pit mining in April 2018, ordering mining companies to conduct reforestation activities.[480] In April 2021, to boost government revenue and the COVID-19 pandemic-battered economy, he lifted the nine-year moratorium on new mining agreements imposed in 2012; the move was hailed by mining companies but has dismayed environmental activists and progressive groups.[481] The ban on open-pit mine on copper, gold, silver, and complex ores imposed in 2017 by Gina Lopez was subsequently repealed through a Department Administrative Order signed by environment secretary Roy Cimatu in December 2021.[482]

Boracay cleanup

Issues concerning pollution and improper waste management in Boracay island, the country's number one tourism destination, caught the national government's attention in early 2018, when the country's tourism and environment departments warned and ordered to close down establishments in the island over violations of water, waste treatment, and land use regulations.[483][484]

On April 4, 2018, Duterte ordered a six-month closure of Boracay to address raw sewage entering its natural waters;[485] Duterte said that the government had "no master plan" on how to clean up the island, which he called a "cesspool", and said the island will be a land reform area once its rehabilitation is completed.[486] On April 24, about 600 soldiers, police, and coast guard members were deployed in Boracay to maintain peace and order amid possible protests during the closure,[487][488] causing alarm among residents.[489] Boracay's six-month closure began on April 26, and the entire island was officially closed to the public.[490] Two weeks after the closure, Duterte ordered the creation a Boracay inter-agency task force to review and consolidate existing master plans and formulate an action plan to reverse the degradation of the island resort.[491]

Boracay was officially reopened to the public on October 26, 2019, following a six-month extensive cleanup.[492] A limit of 6,000 visitors to the island per day had been set by the government, as studies have shown Boracay's capacity at only 6,000.[493]

On September 14, 2021, Duterte signed an executive order extending the Boracay Inter-Agency Task Force's term until June 2022 to "ensure completion of the remaining milestones of the Boracay Action Plan until 2022".[494]

Manila Bay cleanup

Following the Boracay cleanup, the Duterte administration pursued to rehabilitate the Manila Bay.[495][496] On January 8, 2019, Duterte ordered for the cleanup of Manila Bay, instructing Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) secretary Roy Cimatu and Department of the Interior and Local Government secretary Eduardo Año to initiate the cleanup. Duterte warned hotels along the bay to install water treatment systems or risk being shut down.[497] Rehabilitation of the bay started on January 27,[498] with the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority collecting more than 45 tons of garbage that day.[499] In February 2019, Duterte issued an administrative order creating the Manila Bay Task Force tasked to hasten the rehabilitation of the bay.[496] Coliform levels in several parts of the bay had significantly dropped since the cleanup.[500]

In September 2020, the DENR began overlaying crushed dolomite rock on a portion of Manila Bay to create an artificial beach as part of the bay's rehabilitation;[501] the move has drawn criticism from environmental advocates,[502] and the opposition,[501] but has drawn support from the general public.[503]

Land reclamation

Amid imminent reclamation projects in Manila Bay in February 2019, Duterte signed an executive order transferring the power to approve reclamation projects from the National Economic and Development Authority to the Philippine Reclamation Authority (PRA), which he placed under his office, the Office of the President.[504] In February 2020, he rejected reclamation projects in the bay from the private sector, citing the damage they will cause to the city; he said only government-related reclamation projects including those approved by the PRA will be allowed to proceed.[505]

In April 2022, Duterte ordered DENR acting secretary Jim Sampulna to stop the processing of applications for all reclamation projects in the country, stressing that massive land reclamation proposals are "nothing but a breeding ground for corruption".[506]

Illegal logging

After Cagayan Valley experienced massive flooding due to Typhoon Ulysses, Duterte, on November 15, 2020, ordered Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu to look into reports of illegal logging and mining, lamenting that despite being discussed in various meetings, "nothing" has been done to address the issues.[507] He vowed to improve efforts against illegal logging and mining to prevent a repeat of the disaster. Interior Secretary Eduardo Año ordered the Philippine National Police to begin a campaign against illegal logging.[508] On August 26, 2021, Duterte revealed that the New People's Army protects illegal loggers in exchange for money.[509]

Health