Domperidone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Motilium, many others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular, intravenous (d/c'd), rectal[1] |

| Drug class | D2 receptor antagonist; Prolactin releaser |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: 13–17%[1][4] Intramuscular: 90%[1] |

| Protein binding | ~92%[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP3A4/5) and intestinal (first-pass)[1][5] |

| Metabolites | All inactive[1][5] |

| Elimination half-life | 7.5 hours[1][4] |

| Excretion | Feces: 66%[1] Urine: 32%[1] Breast milk: small quantities[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.055.408 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

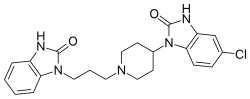

| Formula | C22H24ClN5O2 |

| Molar mass | 425.92 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 242.5 °C (468.5 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Domperidone, sold under the brand name Motilium among others, is a medication used as an antiemetic, gastric prokinetic agent, and galactagogue.[1][6][7] It may be taken by mouth or rectally, and is available as a tablet, orally disintegrating tablets,[8] suspension, and suppositories.[9] The drug is used to relieve nausea and vomiting; to increase the transit of food through the stomach (by increasing gastrointestinal peristalsis); and to promote lactation (breast milk production) by release of prolactin.[1][7]

It is a peripherally selective dopamine D2 receptor antagonist and was developed by Janssen Pharmaceutica.

Medical uses

Nausea and vomiting

There is some evidence that domperidone has antiemetic activity.[10] It is recommended by the Canadian Headache Society for treatment of nausea associated with acute migraine.[11]

Gastroparesis

Gastroparesis is a medical condition characterised by delayed emptying of the stomach when there is no mechanical gastric outlet obstruction. Its cause is most commonly idiopathic, a diabetic complication or a result of abdominal surgery. The condition causes nausea, vomiting, fullness after eating, early satiety (feeling full before the meal is finished), abdominal pain and bloating.

Domperidone may be useful in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis.[12][13]

However, increased rate of gastric emptying induced by drugs like domperidone does not always correlate (equate) well with relief of symptoms.[14]

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is a chronic neurological condition where a decrease in dopamine in the brain leads to rigidity (stiffness of movement), tremor and other symptoms and signs. Poor gastrointestinal function, nausea and vomiting is a major problem for people with Parkinson's disease because most medications used to treat Parkinson's disease are given by mouth. These medications, such as levodopa, can cause nausea as a side effect. Furthermore, anti-nausea drugs, such as metoclopramide, which do cross the blood–brain barrier may worsen the extra-pyramidal symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Domperidone can be used to relieve gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson's disease; it blocks peripheral D2 receptors but does not cross the blood–brain barrier in normal doses (the barrier between the blood circulation of the brain and the rest of the body) so has no effect on the extrapyramidal symptoms of the disease.[15]

Functional dyspepsia

Domperidone may be used in functional dyspepsia in both adults and children.[16][17]

Lactation

The hormone prolactin stimulates lactation (production of breast milk). Dopamine, released by the hypothalamus stops the release of prolactin from the pituitary gland. Domperidone, by acting as an anti-dopaminergic agent, results in increased prolactin secretion, and thus promotes lactation (that is, it is a galactogogue). Domperidone moderately increases the volume of expressed breast milk in mothers of preterm babies where breast milk expression was inadequate, and appears to be safe for short-term use for this purpose.[18][19][20] In the United States, domperidone is not approved for this or any other use.[21][22]

A study called the EMPOWER trial was designed to assess the effectiveness and safety of domperidone in assisting mothers of preterm babies to supply breast milk for their infants.[23] The study randomized 90 mothers of preterm babies to receive either domperidone 10 mg orally three times daily for 28 days (Group A) or placebo 10 mg orally three times daily for 14 days followed by domperidone 10 mg orally three times daily for 14 days (Group B). Mean milk volumes at the beginning of the intervention were similar between the 2 groups. After the first 14 days, 78% of mothers receiving domperidone (Group A) achieved a 50% increase in milk volume, while 58% of mothers receiving placebo (Group B) achieved a 50% increase in milk volume.[24]

To induce lactation, domperidone is used at a dosage of 10 to 20 mg 3 or 4 times per day by mouth.[25] Effects may be seen within 24 hours or may not be seen for 3 or 4 days.[25] The maximum effect occurs after 2 or 3 weeks of treatment, and the treatment period generally lasts for 3 to 8 weeks.[25] A 2012 review shows that no studies support prophylactic use of a galactagogue medication at any stage of pregnancy, including domperidone.[26]

Reflux in children

Domperidone has been found effective in the treatment of reflux in children.[27] However some specialists consider its risks prohibitory of the treatment of infantile reflux.[28]

Contraindications

- QT-prolonging drugs like amiodarone[29]

Side effects

Side effects associated with domperidone include dry mouth, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, nausea, rash, itching, hives, and hyperprolactinemia (the symptoms of which may include breast enlargement, galactorrhea, breast pain/tenderness, gynecomastia, hypogonadism, and menstrual irregularities).[25] Due to blockade of D2 receptors in the central nervous system, D2 receptor antagonists like metoclopramide can also produce a variety of additional side effects including drowsiness, akathisia, restlessness, insomnia, lassitude, fatigue, extrapyramidal symptoms, dystonia, Parkinsonian symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and depression.[1][7] However, this is not the case with domperidone, because, unlike other D2 receptor antagonists, it minimally crosses the blood-brain-barrier, and for this reason, is rarely associated with such side effects.[1][7]

Excess prolactin levels

Due to D2 receptor blockade, domperidone causes hyperprolactinemia.[30] Hyperprolactinemia can suppress the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, in turn suppressing the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) and resulting in hypogonadism (low sex hormone (e.g., testosterone, estradiol) levels).[31] As such, male patients may experience low libido, erectile dysfunction, and impaired spermatogenesis.[31] Also in accordance with hyperprolactinemia, 10–15% of female patients have been reported to experience mammoplasia (breast enlargement), mastodynia (breast pain/tenderness), galactorrhea (inappropriate or excessive milk production/secretion), and amenorrhea (cessation of menstrual cycles) with domperidone treatment.[30] Gynecomastia has been reported in males treated with domperidone,[32] and galactorrhea could occur in males as well.[31]

Rare reactions

Cardiac reactions

Domperidone use is associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death (by 70%)[33] most likely through its prolonging effect of the cardiac QT interval and ventricular arrhythmias.[34][35] The cause is thought to be blockade of hERG voltage-gated potassium channels.[36][37] The risks are dose-dependent, and appear to be greatest with high/very high doses via intravenous administration and in the elderly, as well as with drugs that interact with domperidone and increase its circulating concentrations (namely CYP3A4 inhibitors).[38][39] Conflicting reports exist, however.[40] In neonates and infants, QT prolongation is controversial and uncertain.[41][42]

UK drug regulatory authorities (MHRA) have issued the following restriction on domperidone in 2014 due to increased risk of adverse cardiac effects:

Domperidone (Motilium) is associated with a small increased risk of serious cardiac side effects. Its use is now restricted to the relief of nausea and vomiting and the dosage and duration of use have been reduced. It should no longer be used for the treatment of bloating and heartburn. Domperidone is now contraindicated in those with underlying cardiac conditions and other risk factors. Patients with these conditions and patients receiving long-term treatment with domperidone should be reassessed at a routine appointment, in light of the new advice.

However, a 2015 Australian review concluded the following:[39]

Based on the results of the two TQT (the regulatory agency gold standard for assessment of QT prolongation) domperidone does not appear to be strongly associated with QT prolongation at oral doses of 20 mg QID in healthy volunteers. Further, there are limited case reports supporting an association with cardiac dysfunction, and the frequently cited case-control studies have significant flaws. While there remains an ill-defined risk at higher systemic concentrations, especially in patients with a higher baseline risk of QT prolongation, our review does not support the view that domperidone presents intolerable risk.

Possible central toxicity in infants

In Britain a legal case involved the death of two children of a mother whose three children had all had hypernatraemia. She was charged with poisoning the children with salt. One of the children, who was born at 28 weeks gestation with respiratory complications and had a fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux and failure to thrive was prescribed domperidone. An advocate for the mother suggested the child may have suffered neuroleptic malignant syndrome as a side effect of domperidone due to the drug crossing the child's immature blood-brain-barrier.[43]

Interactions

In healthy volunteers, ketoconazole increased the Cmax and AUC concentrations of domperidone by 3- to 10-fold.[44] This was accompanied by a QT interval prolongation of about 10–20 milliseconds when domperidone 10 mg four times daily and ketoconazole 200 mg twice daily were administered, whereas domperidone by itself at the dosage assessed produced no such effect.[44] As such, domperidone with ketoconazole or other CYP3A4 inhibitors is a potentially dangerous combination.[44]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Domperidone is a peripherally selective dopamine D2 and D3 receptor antagonist.[7] It has no clinically significant interaction with the D1 receptor, unlike metoclopramide.[7] The medication provides relief from nausea by blocking D receptors.[10] It blocks dopamine receptors in the anterior pituitary gland increasing release of prolactin which in turn increases lactation.[45][46] Domperidone may be more useful in some patients and cause harm in others by way of the genetics of the person, such as polymorphisms in the drug transporter gene ABCB1 (which encodes P-glycoprotein), the voltage-gated potassium channel KCNH2 gene (hERG/Kv11.1), and the α1D—adrenoceptor ADRA1D gene.[47]

Effects on prolactin levels

A single 20 mg oral dose of domperidone has been found to increase mean serum prolactin levels (measured 90 minutes post-administration) in non-lactating women from 8.1 ng/mL to 110.9 ng/mL (a 13.7-fold increase).[7][48][49][50] This was similar to the increase in prolactin levels produced by a single 20 mg oral dose of metoclopramide (7.4 ng/mL to 124.1 ng/mL; 16.7-fold increase).[49][50] After two weeks of chronic administration (30 mg/day in both cases), the increase in prolactin levels produced by domperidone was reduced (53.2 ng/mL; 6.6-fold above baseline), but the increase in prolactin levels produced by metoclopramide, conversely, was heightened (179.6 ng/mL; 24.3-fold above baseline).[7][50] This indicates that acute and chronic administration of both domperidone and metoclopramide is effective in increasing prolactin levels, but that there are differential effects on the secretion of prolactin with chronic treatment.[49][50] The mechanism of the difference is unknown.[50] The increase in prolactin levels observed with the two drugs was, as expected, much greater in women than in men.[49][50] This appears to be due to the higher estrogen levels in women, as estrogen stimulates prolactin secretion.[51]

For comparison, normal prolactin levels in women are less than 20 ng/mL, prolactin levels peak at 100 to 300 ng/mL at parturition in pregnant women, and in lactating women, prolactin levels have been found to be 90 ng/mL at 10 days postpartum and 44 ng/mL at 180 days postpartum.[52][53]

Pharmacokinetics

With oral administration, domperidone is extensively metabolized in the liver (almost exclusively by CYP3A4/5, though minor contributions by CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP2C8 have also been reported)[54] and in the intestines.[5] Due to the marked first-pass effect via this route, the oral bioavailability of domperidone is low (13–17%);[1] conversely, its bioavailability is high via intramuscular injection (90%).[1] The terminal half-life of domperidone is 7.5 hours in healthy individuals, but can be prolonged to 20 hours in people with severe renal dysfunction.[1] All of the metabolites of domperidone are inactive as D2 receptor ligands.[1][5] The drug is a substrate for the P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) transporter, and animal studies suggest that this is the reason for the low central nervous system penetration of domperidone.[55]

Chemistry

Domperidone is a benzimidazole derivative and is structurally related to butyrophenone neuroleptics like haloperidol.[56][57]

History

- 1974 – Domperidone synthesized at Janssen Pharmaceutica[58] following the research on antipsychotic drugs.[59] Janssen pharmacologists discovered that some of antipsychotic drugs had a significant effect on dopamine receptors in the central chemoreceptor trigger zone that regulated vomiting and started searching for a dopamine antagonist that would not pass the blood–brain barrier, thereby being free of the extrapyramidal side effects that were associated with drugs of this type.[59] This led to the discovery of domperidone as a strong anti-emetic with minimal central effects.[59][60]

- 1978 – On 3 January 1978 Domperidone was patented in the United States under patent US4066772 A. The application has been filed on 17 May 1976. Jan Vandenberk, Ludo E. J. Kennis, Marcel J. M. C. Van der Aa and others has been cited as the inventors.

- 1979 – Domperidone marketed under trade name "Motilium" in Switzerland and (Western) Germany.[61]

- 1999 – Domperidone was introduced in the forms of orally disintegrating tablets (based on Zydis technology).[62]

- Janssen Pharmaceutical has brought domperidone before the United States Federal Drug Administration (FDA) several times, including in the 1990s.

- 2014 – In April 2014 Co-ordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures – Human (CMDh) published official press-release suggesting to restrict the use of domperidone-containing medicines. It also approved earlier published suggestions by Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) to use domperidone only for curing nausea and vomiting and reduce maximum daily dosage to 10 mg.[9]

Society and culture

Generic names

Domperidone is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, BAN, and JAN.[63][6][64]

Regulatory approval

It was reported in 2007 that domperidone is available in 58 countries, including Canada,[65] but the uses or indications of domperidone vary between nations. In Italy it is used in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease and in Canada, the drug is indicated in upper gastrointestinal motility disorders and to prevent gastrointestinal symptoms associated with the use of dopamine agonist antiparkinsonian agents.[66] In the United Kingdom, domperidone is only indicated for the treatment of nausea and vomiting and the treatment duration is usually limited to 1 week.

In the United States, domperidone is not currently a legally marketed human drug and it is not approved for sale in the U.S. On 7 June 2004, FDA issued a public warning that distributing any domperidone-containing products is illegal.[67]

It is available over-the-counter to treat gastroesophageal reflux and functional dyspepsia in many countries, such as Ireland, the Netherlands, Italy, South Africa, Mexico, Chile, and China.[68]

Domperidone is not generally approved for use in the United States. There is an exception for use in people with treatment-refractory gastrointestinal symptoms under an FDA Investigational New Drug application.[1]

Formulations

| Formulations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nation | Manufacturer | Brand | Formulations |

| Australia | Janssen–Cilag | Motilium | 10 mg scored tablets[29] |

| Belgium and the Netherlands | - | Motilium | From 2013 only by prescription in Belgium.[69] |

| Bangladesh | Square | Motigut | 10 mg scored tablets |

| Bangladesh | Orion Pharma | Cosy | 10 mg scored tablets |

| Bangladesh | Astra Pharma | Domperon | 10 mg scored tablets |

| Bangladesh | - | Ridon | - |

| Canada | - | Motilium (1985–2002) | Generic brands available |

| France | Janssen | Motilium | 10 mg tablets only with prescription generic domperidone available |

| Greece | Johnson & Johnson Hellas | Cilroton | 10 mg scored tablets |

| India | Salius Pharma | Escacid DXR | pantoprazole 40 mg and domperidone SR 30 mg |

| India | FDC Pharmaceuticals | Pepcia-D | Rabeprazole 20 mg and Domperidone SR 30 mg |

| India | Rhubarb pharmaceuticals | - | domperidone 5, 10 and 20 mg tablets. |

| India | Ipca Laboratories, Mumbai | Domperi suspension | domperidone 1 mg/ml, 30 ml suspension.[70] |

| India | Torrent pharmaceuticals | Domstal | -[71] |

| India | Ozone pharmaceuticals and chemicals | Pantazone-D | 10 mg domperidone and 40 mg pantoprazole |

| India | Chimak Health Care | Pancert D | 10 mg Domperidone and 40 mg pantoprazole |

| India | Draavin Pharma | Draaci-XD | Pantaprazole 40 mg and Domperione 30 mg |

| Iran | Abidi Pharmaceutical Co. | MOTiDON | 10 mg tablet |

| Ireland | McNeil Healthcare | Motilium | 10 mg orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) |

| Italy | - | Peridon | domperidone 10 mg tablets; 30 ml suspension |

| Lithuania | Johnson & Johnson | Motilium | - |

| Pakistan | Barrett Hodgson Pakistan | Domel | |

| Pakistan | Johnson & Johnson Pakistan | Motilium-v | domperidone 10 mg tablets; 30 ml suspension |

| Pakistan | ATCO Laboratories Limited | Vomilux | domperidone 10 mg tablets |

| Pakistan | Aspin Pharma (Pvt) Limited | Motilium | domperidone 10 mg tablets |

| Philippines | Health Saver Pharma | Abdopen | - |

| Philippines | United Laboratories, Inc. | GI Norm | - |

| Portugal | Medinfar | Cinet | domperidone 1 mg/ml oral suspension (200 ml) |

| Russia | Janssen Pharmaceutica | Motilium | domperidone 10 mg film-coated tablets & ODT; 1 mg/ml suspension (100 ml) |

| - | OBL Pharm | Passagix | domperidone 10 mg film-coated tablets & chewable tablets |

| - | Dr. Reddy's Laboratories | Omez D | domperidone/omeprazole (10 mg/10 mg) |

| Saudi Arabia | JamJoom Pharmaceuticals | Dompy | Domperidone 10 mg tablets |

| Spain | Laboratorios Dr. Esteve, SA | Motilium | domperidone 1 mg/ml oral suspension (200 ml) |

| Sweden | Ebb medical | Domperidon Ebb (2013) | domperidone 10 mg ODT and peppermint |

| Taiwan | - | Dotitone | - |

| Thailand | - | Motilium M | - |

| Turkey | Saba | Motinorm | - |

| - | GlaxoSmithKline | Motinorm | - |

Research

Domperidone has been studied as a potential hormonal contraceptive to prevent pregnancy in women.[72]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Reddymasu, Savio C.; Soykan, Irfan; McCallum, Richard W. (2007). "Domperidone: Review of Pharmacology and Clinical Applications in Gastroenterology". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 102 (9): 2036–2045. ISSN 0002-9270. PMID 17488253.

- ^ "БРЮЛІУМ ЛІНГВАТАБС" [BRULIUM LINGUATABS]. Нормативно-директивні документи МОЗ України (in Ukrainian). 18 March 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "Domperidone". Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ a b Suzanne Rose (October 2004). Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Pathophysiology. Hayes Barton Press. pp. 523–. ISBN 978-1-59377-181-2.

- ^ a b c d Simard, C.; Michaud, V.; Gibbs, B.; Massé, R.; Lessard, É; Turgeon, J. (2008). "Identification of the cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of domperidone". Xenobiotica. 34 (11–12): 1013–1023. doi:10.1080/00498250400015301. ISSN 0049-8254. PMID 15801545. S2CID 27426219.

- ^ a b Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 366–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barone JA (1999). "Domperidone: a peripherally acting dopamine2-receptor antagonist". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 33 (4): 429–40. doi:10.1345/aph.18003. PMID 10332535. S2CID 39279569.

- ^ "MOTILIUM INSTANTS PL 13249/0028" (PDF). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- ^ a b "CMDh confirms recommendations on restricting use of domperidone-containing medicines: European Commission to take final legal decision". European Medicines Agency. 25 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- ^ a b "Domperidone: review of pharmacology and clinical applications in gastroenterology". Am J Gastroenterol. 102 (9): 2036–45. 2007. PMID 17488253.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Worthington I, Pringsheim T, Gawel MJ, Gladstone J, Cooper P, Dilli E, Aube M, Leroux E, Becker WJ (September 2013). "Canadian Headache Society Guideline: acute drug therapy for migraine headache". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 40 (5 Suppl 3): S1–S80. doi:10.1017/S0317167100118943. PMID 23968886.

- ^ Stevens JE, Jones KL, Rayner CK, Horowitz M (June 2013). "Pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of gastroparesis: current and future perspectives". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 14 (9): 1171–86. doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.795948. PMID 23663133. S2CID 23526883.

- ^ Silvers D, Kipnes M, Broadstone V, Patterson D, Quigley EM, McCallum R, Leidy NK, Farup C, Liu Y, Joslyn A (1998). "Domperidone in the management of symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis: efficacy, tolerability, and quality-of-life outcomes in a multicenter controlled trial. DOM-USA-5 Study Group". Clinical Therapeutics. 20 (3): 438–53. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(98)80054-4. PMID 9663360.

- ^ Janssen P, Harris MS, Jones M, Masaoka T, Farré R, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L, Simrén M, Tack J (September 2013). "The relation between symptom improvement and gastric emptying in the treatment of diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 108 (9): 1382–91. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.118. PMID 24005344. S2CID 32835351.

- ^ Ferrier J (2014). "Domperidone as an unintended antipsychotic". Can Pharm J. 147 (2): 76–7. doi:10.1177/1715163514521969. PMC 3962062. PMID 24660005.

- ^ Xiao M, Qiu X, Yue D, Cai Y, Mo Q (2013). "Influence of hippophae rhamnoides on two appetite factors, gastric emptying and metabolic parameters, in children with functional dyspepsia" (PDF). Hellenic Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 16 (1): 38–43. doi:10.1967/s002449910070 (inactive 19 January 2021). PMID 23529392.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link) - ^ Huang X, Lv B, Zhang S, Fan YH, Meng LN (December 2012). "Itopride therapy for functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (48): 7371–7. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7371. PMC 3544044. PMID 23326147.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Grzeskowiak LE, Smithers LG, Amir LH, Grivell RM (October 2018). "Domperidone for increasing breast milk volume in mothers expressing breast milk for their preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BJOG. 125 (11): 1371–1378. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15177. hdl:2440/114203. PMID 29469929.

- ^ Grzeskowiak LE, Lim SW, Thomas AE, Ritchie U, Gordon AL (February 2013). "Audit of domperidone use as a galactogogue at an Australian tertiary teaching hospital". Journal of Human Lactation. 29 (1): 32–7. doi:10.1177/0890334412459804. hdl:2440/94368. PMID 23015150. S2CID 26535783.

- ^ Donovan TJ, Buchanan K (2012). "Medications for increasing milk supply in mothers expressing breastmilk for their preterm hospitalised infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD005544. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005544.pub2. PMID 22419310.

- ^ da Silva OP, Knoppert DC (September 2004). "Domperidone for lactating women". CMAJ. 171 (7): 725–6. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1041054. PMC 517853. PMID 15451832.

- ^ "FDA warns against women using unapproved drug, domperidone to increase milk production." U.S. Food and Drug Administration 7 June 2004.

- ^ Asztalos EV, Campbell-Yeo M, daSilva OP, Kiss A, Knoppert DC, Ito S (2012). "Enhancing breast milk production with Domperidone in mothers of preterm neonates (EMPOWER trial)". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 12: 87. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-87. PMC 3532128. PMID 22935052.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Asztalos EV, Campbell-Yeo M, da Silva OP, Ito S, Kiss A, Knoppert D, et al. (EMPOWER Study Collaborative Group) (2017). "Enhancing human milk production with Domperidone in mothers of preterm infants". Journal of Human Lactation. 33 (1): 181–187. doi:10.1177/0890334416680176. PMID 28107101. S2CID 39041713.

- ^ a b c d Henderson, Amanda (2003). "Domperidone: Discovering New Choices for Lactating Mothers". AWHONN Lifelines. 7 (1): 54–60. doi:10.1177/1091592303251726. ISSN 1091-5923. PMID 12674062.

- ^ Donovan, Timothy J; Buchanan, Kerry (14 March 2012). "Medications for increasing milk supply in mothers expressing breastmilk for their preterm hospitalised infants". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD005544. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005544.pub2. PMID 22419310.

- ^ Kapoor, A.K.; Raju, S.M. (2013). "7.2 Gastrointestinal Drugs". Illustrated Medical Pharmacology. JP Medical Ltd. p. 677. ISBN 978-9350906552. Retrieved 31 October 2014. (Google Books)

- ^ Rebecca Smith (1 August 2014). "Fear that reflux treatment for babies will be denied under new Nice guidance". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- ^ a b Swannick G. (ed.) "MIMS Australia." December 2013

- ^ a b Elliott Proctor Joslin; C. Ronald Kahn (2005). Joslin's Diabetes Mellitus: Edited by C. Ronald Kahn ... [et Al.]. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1084–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2796-9.

- ^ a b c Edmund S. Sabanegh, Jr. (20 October 2010). Male Infertility: Problems and Solutions. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-1-60761-193-6.

- ^ Gerald G. Briggs; Roger K. Freeman; Sumner J. Yaffe (28 March 2012). Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 442–. ISBN 978-1-4511-5359-0.

- ^ Leelakanok N, Holcombe A, Schweizer ML (2015). "Domperidone and Risk of Ventricular Arrhythmia and Cardiac Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Clin Drug Investig. 36 (2): 97–107. doi:10.1007/s40261-015-0360-0. PMID 26649742. S2CID 25601738.

- ^ van Noord C, Dieleman JP, van Herpen G, Verhamme K, Sturkenboom MC (November 2010). "Domperidone and ventricular arrhythmia or sudden cardiac death: a population-based case-control study in the Netherlands". Drug Safety. 33 (11): 1003–14. doi:10.2165/11536840-000000000-00000. PMID 20925438. S2CID 21177240.

- ^ Johannes CB, Varas-Lorenzo C, McQuay LJ, Midkiff KD, Fife D (September 2010). "Risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death in a cohort of users of domperidone: a nested case-control study". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 19 (9): 881–8. doi:10.1002/pds.2016. PMID 20652862. S2CID 20323199.

- ^ Rossi M, Giorgi G (2010). "Domperidone and long QT syndrome". Curr Drug Saf. 5 (3): 257–62. doi:10.2174/157488610791698334. PMID 20394569.

- ^ Doggrell SA, Hancox JC (2014). "Cardiac safety concerns for domperidone, an antiemetic and prokinetic, and galactogogue medicine" (PDF). Expert Opin Drug Saf. 13 (1): 131–8. doi:10.1517/14740338.2014.851193. PMID 24147629. S2CID 30668496.

- ^ Marzi, Marta; Weitz, Darío; Avila, Aylén; Molina, Gabriel; Caraballo, Lucía; Piskulic, Laura (2015). "Efectos adversos cardíacos de la domperidona en pacientes adultos: revisión sistemática". Revista Médica de Chile. 143 (1): 14–21. doi:10.4067/S0034-98872015000100002. ISSN 0034-9887. PMID 25860264.

- ^ a b Buffery PJ, Strother RM (2015). "Domperidone safety: a mini-review of the science of QT prolongation and clinical implications of recent global regulatory recommendations". N. Z. Med. J. 128 (1416): 66–74. PMID 26117678.

- ^ Ortiz, Arleen; Cooper, Chad J.; Alvarez, Alicia; Gomez, Yvette; Sarosiek, Irene; McCallum, Richard W. (2015). "Cardiovascular Safety Profile and Clinical Experience With High-Dose Domperidone Therapy for Nausea and Vomiting". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 349 (5): 421–424. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000439. ISSN 0002-9629. PMC 4418779. PMID 25828198.

- ^ Djeddi D, Kongolo G, Lefaix C, Mounard J, Léké A (November 2008). "Effect of domperidone on QT interval in neonates". The Journal of Pediatrics. 153 (5): 663–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.013. PMID 18589449.

- ^ Günlemez A, Babaoğlu A, Arisoy AE, Türker G, Gökalp AS (January 2010). "Effect of domperidone on the QTc interval in premature infants". Journal of Perinatology. 30 (1): 50–3. doi:10.1038/jp.2009.96. PMC 2834362. PMID 19626027.

- ^ Coulthard MG, Haycock GB (January 2003). "Distinguishing between salt poisoning and hypernatraemic dehydration in children". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 326 (7381): 157–60. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7381.157. PMC 1128889. PMID 12531853.

- ^ a b c Jeffrey K. Aronson (27 November 2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Antimicrobial Drugs. Elsevier. pp. 2244–. ISBN 978-0-08-093293-4.

- ^ Saeb-Parsy K. "Instant pharmacology." John Wiley & Sons, 1999 ISBN 0471976393, 9780471976394 p216.

- ^ Sakamoto Y, Kato S, Sekino Y, Sakai E, Uchiyama T, Iida H, Hosono K, Endo H, Fujita K, Koide T, Takahashi H, Yoneda M, Tokoro C, Goto A, Abe Y, Kobayashi N, Kubota K, Maeda S, Nakajima A, Inamori M (2011). "Effects of domperidone on gastric emptying: a crossover study using a continuous real-time 13C breath test (BreathID system)". Hepato-gastroenterology. 58 (106): 637–41. PMID 21661445.

- ^ Parkman HP, Jacobs MR, Mishra A, Hurdle JA, Sachdeva P, Gaughan JP, Krynetskiy E (January 2011). "Domperidone treatment for gastroparesis: demographic and pharmacogenetic characterization of clinical efficacy and side-effects". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 56 (1): 115–24. doi:10.1007/s10620-010-1472-2. PMID 21063774. S2CID 39632855.

- ^ Gabay MP (2002). "Galactogogues: medications that induce lactation". J Hum Lact. 18 (3): 274–9. doi:10.1177/089033440201800311. PMID 12192964. S2CID 29261467.

- ^ a b c d Hofmeyr GJ, Van Iddekinge B, Blott JA (1985). "Domperidone: secretion in breast milk and effect on puerperal prolactin levels". Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 92 (2): 141–4. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb01065.x. PMID 3882143. S2CID 25489895.

- ^ a b c d e f Brouwers JR, Assies J, Wiersinga WM, Huizing G, Tytgat GN (1980). "Plasma prolactin levels after acute and subchronic oral administration of domperidone and of metoclopramide: a cross-over study in healthy volunteers". Clin. Endocrinol. 12 (5): 435–40. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1980.tb02733.x. PMID 7428183. S2CID 27266775.

- ^ Fujino T, Kato H, Yamashita S, Aramaki S, Morioka H, Koresawa M, Miyauchi F, Toyoshima H, Torigoe T (1980). "Effects of domperidone on serum prolactin levels in human beings". Endocrinol. Jpn. 27 (4): 521–5. doi:10.1507/endocrj1954.27.521. PMID 7460861.

- ^ Jan Riordan (January 2005). Breastfeeding and Human Lactation. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-0-7637-4585-1.

- ^ Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- ^ Youssef AS, Parkman HP, Nagar S (2015). "Drug-drug interactions in pharmacologic management of gastroparesis". Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 27 (11): 1528–41. doi:10.1111/nmo.12614. PMID 26059917. S2CID 34728070.

- ^ Stan K. Bardal; Jason E. Waechter; Douglas S. Martin (2011). Applied Pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 184–. ISBN 978-1-4377-0310-8.

- ^ Hospital Formulary. HFM Publishing Corporation. 1991. p. 171.

Domperidone, a benzimidazole derivative, is structurally related to the butyrophenone tranquilizers (eg, haloperidol (Haldol, Halperon]).

- ^ Giovanni Biggio; Erminio Costa; P. F. Spano (22 October 2013). Receptors as Supramolecular Entities: Proceedings of the Biannual Capo Boi Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 7-10 June 1981. Elsevier Science. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-4831-5550-0.

- ^ Wan EW, Davey K, Page-Sharp M, Hartmann PE, Simmer K, Ilett KF (27 May 2008). "Dose-effect study of domperidone as a galactagogue in preterm mothers with insufficient milk supply, and its transfer into milk". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 66 (2): 283–289. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03207.x. PMC 2492930. PMID 18507654.

- ^ a b c Sneader, Walter (2005). "Plant Product Analogues and Compounds Derived from Them". Drug discovery : a history. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- ^ Corsini, Giovanni Umberto (2010). "Apomorphine: from experimental tool to therpeutic aid" (PDF). In Ban, Thomas A; Healy, David & Shorter, Edward (eds.). The Triumph of Psychopharacology and the Story of CINP. CINP. p. 54. ISBN 978-9634081814. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2014.

- ^ "Domperidone". Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (Vol. 1-4). William Andrew Publishing. 2013. p. 138. ISBN 9780815518563. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Rathbone, Michael J.; Hadgraft, Jonathan; Roberts, Michael S. (2002). "The Zydis Oral Fast-Dissolving Dosage Form". Modified-Release Drug Delivery Technology. CRC Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780824708696. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 466–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ "Domperidone".

- ^ Reddymasu SC, Soykan I, McCallum RW (2007). "Domperidone: review of pharmacology and clinical applications in gastroenterology". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 102 (9): 2036–45. PMID 17488253.

- ^ "Domperidone - heart rate and rhythm disorders." Canadian adverse reactions newsletter. Government of Canada. January 2007 17(1)

- ^ "How to Obtain". Food and Drug Administration. 10 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Fais, Paolo; Vermiglio, Elisa; Laposata, Chiara; Lockwood, Robert; Gottardo, Rossella; De Leo, Domenico (2015). "A case of sudden cardiac death following Domperidone self-medication". Forensic Science International. 254: e1–e3. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.06.004. ISSN 0379-0738. PMID 26119456.

- ^ "De Standaard: "Motilium from now on only with prescription"". standaard.be. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ^ "ipcalabs.com". ipcalabs.com. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ "torrentpharma.com". torrentpharma.com. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Hofmeyr, G. J.; Van Iddekinge, B.; Van Der Walt, L. A. (2009). "Effect of domperidone-induced hyperprolactinaemia on the menstrual cycle; a placebo-controlled study". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 5 (4): 263–264. doi:10.3109/01443618509067772. ISSN 0144-3615.