Jawaharlal Nehru: Difference between revisions

divide nationalism movement 1931-1935 into three parts and expand |

|||

| Line 173: | Line 173: | ||

<blockquote>Of course these movements exercised tremendous pressure on the British Government and shook the government machinery. But the real importance, to my mind, lay in the effect they had on our own people, and especially the village masses. ... Non-cooperation dragged them out of the mire and gave them self-respect and self-reliance. ... They acted courageously and did not submit so easily to unjust oppression; their outlook widened and they began to think a little in terms of India as a whole. ... It was a remarkable transformation and the Congress, under Gandhi's leadership, must have the credit for it.</blockquote> |

<blockquote>Of course these movements exercised tremendous pressure on the British Government and shook the government machinery. But the real importance, to my mind, lay in the effect they had on our own people, and especially the village masses. ... Non-cooperation dragged them out of the mire and gave them self-respect and self-reliance. ... They acted courageously and did not submit so easily to unjust oppression; their outlook widened and they began to think a little in terms of India as a whole. ... It was a remarkable transformation and the Congress, under Gandhi's leadership, must have the credit for it.</blockquote> |

||

=== Nationalist movement: |

=== Nationalist movement: 1931–1932 === |

||

The first [[Round Table Conference]] organised by the British government to discuss India's political future began in London on 12 November 1930. The Congress did not attend, but Nehru and other prisoners were released on 26 January 1931 by orders of [[Lord Irwin]], the viceroy of India.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=171-173}} On the day of his release, Nehru was informed that his father, Motilal, was seriously ill.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=171-73}} The family travelled to Lucknow to seek treatment. However, Motilal's health declined and he died in Lucknow on 6 February 1931, with his son and wife present.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=171-73}} On 5 March 1931, Gandhi signed a [[Gandhi–Irwin Pact|pact]] with Lord Irwin. Gandhi obtained some political concessions and agreed to end the Civil Disobedience Movement. Nehru was disappointed with the terms.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Mukherjee|first=Rudrangshu|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Jawaharlal_Nehru/T7mCDwAAQBAJ?hl|title=Jawaharlal Nehru|year=2018|publisher=OUP India|isbn=9780199096596|pages=65}}</ref> Political developments soon turned against the Congress. Lord Irwin left India to be succeeded by [[Lord Willingdon]] in April 1931.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=186-87}} Gandhi and Nehru met Lord Willingdon in [[Shimla]] before agreeing to participate in a second Round Table Conference. Nehru came away with the impression that the new viceroy shared his perception of the pact as a temporary truce.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=187}} In August 1931, a [[Conservative Party (UK)|Conservative]] dominated |

The first [[Round Table Conference]] organised by the British government to discuss India's political future began in London on 12 November 1930. The Congress did not attend, but Nehru and other prisoners were released on 26 January 1931 by orders of [[Lord Irwin]], the viceroy of India.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=171-173}} On the day of his release, Nehru was informed that his father, Motilal, was seriously ill.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=171-73}} The family travelled to Lucknow to seek treatment. However, Motilal's health declined and he died in Lucknow on 6 February 1931, with his son and wife present.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=171-73}} On 5 March 1931, Gandhi signed a [[Gandhi–Irwin Pact|pact]] with Lord Irwin. Gandhi obtained some political concessions and agreed to end the Civil Disobedience Movement. Nehru was disappointed with the terms.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Mukherjee|first=Rudrangshu|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Jawaharlal_Nehru/T7mCDwAAQBAJ?hl|title=Jawaharlal Nehru|year=2018|publisher=OUP India|isbn=9780199096596|pages=65}}</ref> Political developments soon turned against the Congress. Lord Irwin left India to be succeeded by [[Lord Willingdon]] in April 1931.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=186-87}} Gandhi and Nehru met Lord Willingdon in [[Shimla]] before agreeing to participate in a second Round Table Conference. Nehru came away with the impression that the new viceroy shared his perception of the pact as a temporary truce.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=187}} In August 1931, a [[Conservative Party (UK)|Conservative]] dominated |

||

[[National Government (United Kingdom)|National]] coalition came into power in the United Kingdom.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=191-92}} Lord Willingdon moved to suppress the Congress, with the support of the new [[Secretary of State for India]].<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p167-171">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=167-171}}</ref> |

[[National Government (United Kingdom)|National]] coalition came into power in the United Kingdom.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=191-92}} Lord Willingdon moved to suppress the Congress, with the support of the new [[Secretary of State for India]].<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p167-171">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=167-171}}</ref> |

||

| Line 180: | Line 180: | ||

Non-payment of rent was a possible solution, but this risked giving the government a justification to suppress the Congress.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p165-166">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=165-66}}</ref>{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=192-93}} Nehru brought the matter before British authorities.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p165-166">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=165-66}}</ref> The government made no concessions, and the Congress decided to recommend tenant farmers withhold rent.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p165-166"/> The government introduced ordinances to suppress the "no-rent" agitation. Nehru was served with orders prohibiting him from leaving Allahabad and engaging in political activities {{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=192-93}} On 26 December 1931, Nehru was arrested for violating the order as he prepared to leave for Bombay to meet a returning Gandhi. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p167-171"/>{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=192-93}} The government accussed of Nehru of pursuing a "[[Leninite]] dictatorship".<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p167-171"/> Nehru's arrest was part of a larger measure against Indian nationalism. The Congress was once again declared illegal, and most leading Congress members were in jail by 10 January 1932. Gandhi himself was arrested under a 1827 Bombay ordinance revived by the government. Indian civil disobedience was renewed.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=171-73}} |

Non-payment of rent was a possible solution, but this risked giving the government a justification to suppress the Congress.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p165-166">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=165-66}}</ref>{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=192-93}} Nehru brought the matter before British authorities.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p165-166">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=165-66}}</ref> The government made no concessions, and the Congress decided to recommend tenant farmers withhold rent.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p165-166"/> The government introduced ordinances to suppress the "no-rent" agitation. Nehru was served with orders prohibiting him from leaving Allahabad and engaging in political activities {{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=192-93}} On 26 December 1931, Nehru was arrested for violating the order as he prepared to leave for Bombay to meet a returning Gandhi. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p167-171"/>{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=192-93}} The government accussed of Nehru of pursuing a "[[Leninite]] dictatorship".<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p167-171"/> Nehru's arrest was part of a larger measure against Indian nationalism. The Congress was once again declared illegal, and most leading Congress members were in jail by 10 January 1932. Gandhi himself was arrested under a 1827 Bombay ordinance revived by the government. Indian civil disobedience was renewed.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=171-73}} |

||

=== Nationalist movement: 1933–1934 === |

|||

On 30 August 1933, Nehru was released from prison. He travelled to [[Pune]] to meet Gandhi. By this point, Nehru and Gandhi were growing apart. Nehru was vexed by |

On 30 August 1933, Nehru was released from prison. He travelled to [[Pune]] to meet Gandhi. By this point, Nehru and Gandhi were growing apart. Nehru was vexed by Gandhi's anti-rational mysticism, and prioritisation of social movements over independence since the [[Communal Award]] of August 1932.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p176-77">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=176-77}}</ref> Nehru was also concerned by some of Gandhi's lieutenants that he considered [[reactionaries]].<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p176-77"/> A diary entry from 18 July 1933 states "I am getting more and more certain there can be no further political co-operation between Bapu and me. At least not of the kind that existed. We had better go our different ways".<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p176-77"/> It was thought that Nehru might break with Gandhi, but the duo reconciled in Pune. Both publicly affirmed their trust in, and loyalty to, each other.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p179-180">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=179-180}}</ref> Nehru resumed his nationalist activities, and the British government moved to detain him once again. On 22 December 1933, the [[Sir John Gilmour, 2nd Baronet|Home Secretary]] sent a memo to all local governments in India: |

||

<blockquote> The Government of India regard him [Nehru] as by far the most dangerous element at large in India, and their view is that the time has come, in accordance with their general policy of taking steps at an early stage to |

<blockquote> The Government of India regard him [Nehru] as by far the most dangerous element at large in India, and their view is that the time has come, in accordance with their general policy of taking steps at an early stage to |

||

prevent attempts to work up mass agitation, to take action against him.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p185-86">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=185-86}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Government propaganda described Nehru as "the high priest of Communism".<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p187-88">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=187-88}} |

|||

Various speeches made in late 1933 were examined as grounds for prosecution. Nehru's denunciation of the Raj at Calcutta in January 1934 gave the Bengal government the opportunity to change him with sedition. He was arrested on his return to Allahabad on 12 January and taken back to Calcutta. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment on 16 February.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p185-86"/> In August 1934, Nehru was released for eleven days to attend to his wife's ailing health. He was sent back to prison when her health improved.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=251}} |

</ref> The authorities remained fearful of his potential to attract followers to a revolutionary agitation. Various speeches made in late 1933 were examined as grounds for prosecution. Nehru's denunciation of the Raj at Calcutta in January 1934 gave the Bengal government the opportunity to change him with sedition. He was arrested on his return to Allahabad on 12 January and taken back to Calcutta. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment on 16 February.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p185-86"/> In August 1934, Nehru was released for eleven days to attend to his wife's ailing health. He was sent back to prison when her health improved.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=251}} Nehru would end up spending most of the time between December 1931 and September 1935 in prison.<ref>Schöttli, J., 2012. ''Vision and Strategy in Indian Politics: Jawaharlal Nehru’s Policy Choices and the Designing of Political Institutions'', p. 52. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.</ref> |

||

=== Nationalist movement: 1934 === |

|||

On 7 April 1934, Gandhi officially called off the Civil Disobedience Movement.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=231}} The movement had been fading since Gandhi became preoccupied with social issues. Nehru was left bitterly disappointed by the decision. He wrote "...there is hardly any common ground between me and Bapu and the others who lead the Congress today. Our objectives are different, our ideals are different, and our methods are likely to be different".<ref name="B.N.Pandey">{{Cite book|last=Pandey|first=B. N.|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Nehru/PO-wCwAAQBAJ?hl|title=Nehru|date=1976|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK|isbn=9781349007929|language=en|page=179}}</ref><ref name="R.Dube">{{Cite book|last=Dube|first=Rajendra Prasad|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Jawaharlal_Nehru/zE7VJZoHbzYC?hl|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Study in Ideology and Social Change|date=1976|publisher=Mittal Publications|isbn=9788170990710|language=en|page=106}}</ref> Nehru adds that "...I felt with a stab of pain that the cords of allegiance that had bound me to him for many years had snapped."<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p186-87">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=186-87}}</ref> The end of the movement was followed by Gandhi's announcement on 17 September 1934 that he was retiring from Congress politics in order to focus on social issues.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Dalton|first=Dennis|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Mahatma_Gandhi/KxUp1igCL_0C?hl|title=Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Power in Action|date=2012|publisher=Columbia University Press|isbn=9780231159593|language=en|page=230}}</ref> In the interim, the Swaraj Party had been reformed in May 1934 as a group within the Congress, with the support of Gandhi. The Swarajists aimed to contest the [[1934 Indian general election]]{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=235-36}}<ref name="Ghose1988">{{Cite book|last=Ghose|first=Shankar|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Mahatma_Gandhi/5l0BPnxN1h8C?hlhl|title=Mahatma Gandhi|date=1988|publisher=Allied Publishers Limited|isbn=9788170232056|language=en|page=226-27}}</ref></blockquote> However, it was soon decided that the Congress itself would enter the elections, rather than the Swaraj Party on its behalf. To this end, a Congress Parliamentary Board was formed.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Gandhi|first=Rajmohan|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Gandhi/FauJL7LKXmkC?hl|title=Gandhi: The Man, His People, The Empire|date=2012|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=9780520255708|language=en|page=364}}</ref> |

|||

The end of civil disobedience and the embrace of constitutionalism was a bitter blow for Nehru. The business community had been pressuring the Congress to revert to constitutionalism. In April 1934, Gandhi wrote to [[G. D. Birla]] that "There will always be a party within the Congress wedded to the idea of council-entry. The reigns of the Congress should be in the hands of that group."<ref name="Ghose1988"/> The business community was determined to secure influence with the party and office holders. Nehru became unhappy at the anti-socialist orientation of the Congress leadership.<ref name="B.N.Pandey"/><ref name="R.Dube"/> He wrote: |

|||

<blockquote>The Congress had become a caucus where opportunism flourished and the Working Committee's resolution condemning socialism showed such astounding ignorance of even the elements of the subject that it was painful to read it and realize that it might be read outside India. It seemed that the overmastering desire of the Committee was somehow to assure various vested interests even at the risk of talking nonsense.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p187-88"/></blockquote> |

|||

Nehru questioned the sincerity of constitutionalism. He complained that there were constitutionalists who had avoided civil disobedience when politics was unsafe and now sought office.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Ghose|first=Shankar|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Mahatma_Gandhi/5l0BPnxN1h8C?hlhl|title=Mahatma Gandhi|date=1988|publisher=Allied Publishers Limited|isbn=9788170232056|language=en|page=226-27}}</ref> Nehru was also greatly concerned at this time by the growth of [[Communal_violence#Asia|communalism]]. He was critical of religious organisations whom he saw as putting their sectarian interests above the national one of independence.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p182-83">{{Cite book|last=Gopal|first=Sarvepalli|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13225|title=Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Volume 1 1889–1947|date=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780198079828|language=en|page=182-83}}</ref> The competition for office would only widen communal tensions.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=253}} |

|||

In response to events, socialists formed the [[Congress Socialist Party]] faction within the Congress in May 1934. The group included [[Jayaprakash Narayan]], [[Narendra Deo]], [[Rammanohar Lohia]], [[Minoo Masani]], [[Yusuf Meherally]], [[Asoka Mehta]], and [[Achyut Patwardhan]]. This group made no secret that they sought and drew inspiration from Nehru.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p187-88"/> Masani wrote to Nehru in prison: |

|||

<blockquote>...the group in its proposed form would carry out the purpose you have in mind... a programme that would be socialist in action and objective...The group would do socialist propaganda among rank and file with a view to converting the Congress to an acceptance of socialism.<ref name="Mathur">{{Cite book|last=Mathur|first=Sobhag|url=https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Spectrum_of_Nehru_s_thought/YPXStqxsowUC?hl|title=Spectrum of Nehru's thought|date=1994|publisher=Mittal Publ.|isbn=9788170994572|language=en|page=44}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Nehru replied that "I would welcome the formation of a socialist group in the Congress... I feel the time has come when the country should face the issues and come to grips with real economic problems which ultimately matter."<ref name="Mathur"/> However, Nehru declined to join the group.<ref name="Mathur"/> According to [[Sarvepalli Gopal]], Nehru actually considered their decision to form the group premature, and likely to distract from the national goal of independence.<ref name="Sarvepalli1976p187-88"/> Nevertheless, Nehru's position allowed him to become a bridge between the socialists and Gandhi.<ref name="Dutt1981">{{Cite book|last=Rabindra Chandra Dutt|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2WI31XdK8pkC&pg=PR9|title=Socialism of Jawaharlal Nehru|publisher=Abhinav Publications|year=1981|isbn=978-81-7017-128-7|page=178}}</ref> |

|||

=== Europe: 1935–1936 === |

=== Europe: 1935–1936 === |

||

| Line 191: | Line 209: | ||

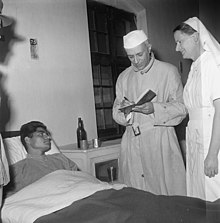

[[File:Jawaharlal Nehru at Karachi on return from Lausanne with Kamala Nehru’s ashes.jpg|thumb|Nehru in [[Karachi]] after returning from [[Lausanne]], [[Switzerland]] with the ashes of his wife [[Kamla Nehru]] in March 1936]] |

[[File:Jawaharlal Nehru at Karachi on return from Lausanne with Kamala Nehru’s ashes.jpg|thumb|Nehru in [[Karachi]] after returning from [[Lausanne]], [[Switzerland]] with the ashes of his wife [[Kamla Nehru]] in March 1936]] |

||

Kamala was very ill by 1935. In May, she travelled to Germany to seek further treatment, and was accompanied by her daughter Indira.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=245–46}} Nehru was released from prison on compassionate grounds in September 1935, and travelled to [[Badenweiler]] to be with his family. While on a visit to England in the fall, Nehru learned that he was Congress president-elect starting in December 1936. He was torn over whether to remain with his family, or accept the presidency. On 31 January, Kamala was moved to a sanatorium near [[Lausanne]] to be closer to Indira, who was studying at Bex.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=248}} On 28 February 1936, Kamala died, with Nehru by her side.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=248}} In March 1936, Nehru returned to India, having accepted the presidency. He stopped in Rome on his way back, and was visited by an Italian official. Nehru learned that [[Mussolini]] wanted to meet him personally to convey condolences. He wrote to Mussolini, thanking him for his message of condolence, but stated that he could not accept his invitation.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=248}} |

Kamala was very ill by 1935. In May, she travelled to Germany to seek further treatment, and was accompanied by her daughter Indira.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=245–46}} Nehru was released early from prison on compassionate grounds in September 1935, and travelled to [[Badenweiler]] to be with his family. While on a visit to England in the fall, Nehru learned that he was Congress president-elect starting in December 1936. He was torn over whether to remain with his family, or accept the presidency. On 31 January, Kamala was moved to a sanatorium near [[Lausanne]] to be closer to Indira, who was studying at Bex.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=248}} On 28 February 1936, Kamala died, with Nehru by her side.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=248}} In March 1936, Nehru returned to India, having accepted the presidency. He stopped in Rome on his way back, and was visited by an Italian official. Nehru learned that [[Mussolini]] wanted to meet him personally to convey condolences. He wrote to Mussolini, thanking him for his message of condolence, but stated that he could not accept his invitation.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=248}} |

||

While in Europe, Nehru travelled to England and France, and met with several intellectuals and politicians.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=248}} He became very concerned with the possibility of another world war. At that time, he emphasised that, in the event of war, India's place was alongside the democracies, though he insisted India could only fight in support of Great Britain and France as a free country.<ref name="Hoiberg2000">{{Cite book|last=Hoiberg, Dale|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ISFBJarYX7YC&pg=PA108|title=Students' Britannica India|publisher=[[Popular Prakashan]]|year=2000|isbn=978-0-85229-760-5|pages=107-08}}</ref> |

While in Europe, Nehru travelled to England and France, and met with several intellectuals and politicians.{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=248}} He became very concerned with the possibility of another world war. At that time, he emphasised that, in the event of war, India's place was alongside the democracies, though he insisted India could only fight in support of Great Britain and France as a free country.<ref name="Hoiberg2000">{{Cite book|last=Hoiberg, Dale|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ISFBJarYX7YC&pg=PA108|title=Students' Britannica India|publisher=[[Popular Prakashan]]|year=2000|isbn=978-0-85229-760-5|pages=107-08}}</ref> |

||

| Line 211: | Line 229: | ||

The 1937 elections brought the Congress party to power in a majority of the provinces, with increased popularity and power for Nehru. Since the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah (who was to become the creator of Pakistan) had fared badly at the polls, Nehru declared that the only two parties that mattered in India were the British colonial authorities and the Congress. Jinnah's statements that the Muslim League was the third and "equal partner" within Indian politics were widely rejected.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_xA-AAAAMAAJ|title=Pakistan: From Community to Nation|author=Arshad Syed Karim|publisher=Saad Publications|year=1985}}</ref> Nehru had hoped to elevate [[Abul Kalam Azad|Maulana Azad]] as the preeminent leader of [[Islam in India|Indian Muslims]], but Gandhi, who continued to treat Jinnah as the voice of Indian Muslims, undermined him in this.<ref>{{Cite news|last1=Ayoob|first1=Mohammed|date=25 May 2018|title=Remembering Maulana Azad|author-link=Mohammed Ayoob|newspaper=[[The Hindu]]|url=https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/remembering-azad/article23980998.ece}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|date=21 May 2019|title=Triumph of Nehruvianism – Part 2|newspaper=The Economic Times |url=https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/blogs/courts-commerce-and-the-constitution/triumph-of-nehruvianism-part-2/|last1=Paul |first1=Santosh }}</ref> |

The 1937 elections brought the Congress party to power in a majority of the provinces, with increased popularity and power for Nehru. Since the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah (who was to become the creator of Pakistan) had fared badly at the polls, Nehru declared that the only two parties that mattered in India were the British colonial authorities and the Congress. Jinnah's statements that the Muslim League was the third and "equal partner" within Indian politics were widely rejected.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_xA-AAAAMAAJ|title=Pakistan: From Community to Nation|author=Arshad Syed Karim|publisher=Saad Publications|year=1985}}</ref> Nehru had hoped to elevate [[Abul Kalam Azad|Maulana Azad]] as the preeminent leader of [[Islam in India|Indian Muslims]], but Gandhi, who continued to treat Jinnah as the voice of Indian Muslims, undermined him in this.<ref>{{Cite news|last1=Ayoob|first1=Mohammed|date=25 May 2018|title=Remembering Maulana Azad|author-link=Mohammed Ayoob|newspaper=[[The Hindu]]|url=https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/remembering-azad/article23980998.ece}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|date=21 May 2019|title=Triumph of Nehruvianism – Part 2|newspaper=The Economic Times |url=https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/blogs/courts-commerce-and-the-constitution/triumph-of-nehruvianism-part-2/|last1=Paul |first1=Santosh }}</ref> |

||

Nehru formed a faction with Congressmen Maulana Azad and [[Subhas Chandra Bose]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/on-parakram-diwas-a-look-at-bose-s-indian-national-army-101611393163491.html|title=On Parakram Diwas, a look at Bose's Indian National Army|last1=Soni|first1=Mallika|date=23 January 2021|website=Hindustan Times}}</ref><ref name="auto6">{{Cite web|url=https://www.newindianexpress.com/galleries/nation/2017/dec/05/indian-national-congress-presidents-over-the-ages-the-ones-who-changed-course-of-history-101085.html|title=Indian National Congress Presidents over the ages: The ones who changed course of history|date=5 December 2017|website=The New Indian Express}}</ref> The trio combined to oust [[Rajendra Prasad]] as the Congress president in 1936.<ref name="auto6" /> Nehru was elected in his place and held the presidency for two years (1936–37).{{sfn|Moraes|2007|pp=234–38}} His socialist colleagues Bose (1938–39) and Azad (1940–46) succeeded him. During Nehru's second term as general secretary of the Congress, he proposed certain resolutions concerning the [[foreign policy of India]].{{sfn|Moraes|2007|p=129}} From then on, he was given ''[[carte blanche]]'' ("blank cheque") in framing the foreign policy of any future Indian nation.<ref>Sharma, Rinkal. 2016. "[https://www.academia.edu/33066114/Nehru_a_passionate_advocate_of_education_for_Indias_children_and_youth_believing_it_essential_for_Indias_future_progress Nehru: a passionate advocate of education for India's children and youth, believing it essential for India's future progress]." ''International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanity'' 7(7):256–59.</ref> Nehru worked closely with Bose in developing international relations with other countries.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.news18.com/news/india/jawaharlal-nehru-birth-anniversary-pandit-nehru-and-his-freedom-struggle-2386021.html|title=Jawaharlal Nehru Birth Anniversary: Pandit Nehru and His Freedom Struggle|date=14 November 2019|website=[[News18]]}}</ref> Nehru was also given the responsibility of planning the economy of a future India and appointed the [[National Planning Commission of India|National Planning Commission]] in 1938 to help frame such policies.<ref>{{Cite web|title=3rd Five Year Plan (Chapter 1)|url=http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/3rd/3planch1.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120326094741/http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/3rd/3planch1.html|archive-date=26 March 2012|access-date=16 June 2012|publisher=Government of India}}</ref><ref name="auto7">{{Cite web|url=https://thewire.in/history/past-continuous-nehru-independence|title=Past Continuous: Those Who Think Nehru Was Power Hungry Should Review Events Leading to Independence|website=The Wire|first=Nilanjan|last=Mukhopadhyay|date=14 November 2018}}</ref> |

|||

The [[All India States Peoples Conference]] (AISPC) was formed in 1927 and Nehru, who had supported the cause of the people of the princely states for many years, was made the organisation's president in 1939.<ref name="Bandyopādhyāẏa2004">{{Cite book|last=Śekhara Bandyopādhyāẏa|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-EpNz0U8VEQC|title=From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India|publisher=[[Orient Blackswan]]|year=2004|isbn=978-81-250-2596-2|page=410}}</ref> He opened up its ranks to membership from across the political spectrum. AISPC was to play an important role during the political integration of India, helping Indian leaders Vallabhbhai Patel and [[V. P. Menon]] (to whom Nehru had delegated integrating the princely states into India) negotiate with hundreds of princes.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lumby|1954|p=232}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Brown|1984|p=667}}</ref> |

The [[All India States Peoples Conference]] (AISPC) was formed in 1927 and Nehru, who had supported the cause of the people of the princely states for many years, was made the organisation's president in 1939.<ref name="Bandyopādhyāẏa2004">{{Cite book|last=Śekhara Bandyopādhyāẏa|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-EpNz0U8VEQC|title=From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India|publisher=[[Orient Blackswan]]|year=2004|isbn=978-81-250-2596-2|page=410}}</ref> He opened up its ranks to membership from across the political spectrum. AISPC was to play an important role during the political integration of India, helping Indian leaders Vallabhbhai Patel and [[V. P. Menon]] (to whom Nehru had delegated integrating the princely states into India) negotiate with hundreds of princes.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lumby|1954|p=232}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Brown|1984|p=667}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:58, 2 June 2023

Jawaharlal Nehru | |

|---|---|

Nehru in 1947 | |

| 1st Prime Minister of India | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 27 May 1964 | |

| Monarch | George VI (until 1950) |

| President |

|

| Governors General |

|

| Deputy | Vallabhbhai Patel (until 1950) |

| Preceded by | Post established |

| Succeeded by | Lal Bahadur Shastri[a] |

| Minister of External Affairs | |

| In office 2 September 1946 – 27 May 1964 | |

| Head of Interim Government of India | |

| In office 2 September 1946 – 15 August 1947 | |

| Governors General |

|

| Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | |

| In office 17 April 1952 – 27 May 1964 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit |

| Constituency | Phulpur, Uttar Pradesh |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 November 1889 Allahabad, North-Western Provinces, British India |

| Died | 27 May 1964 (aged 74) New Delhi, India |

| Resting place | Shantivan |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Indira Gandhi |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Nehru–Gandhi family |

| Alma mater | |

| Awards | Bharat Ratna (1955) |

| Signature | |

Jawaharlal Nehru (/ˈneɪru/ or /ˈnɛru/;[1] Hindi: [ˈdʒəʋɑːɦəɾˈlɑːl ˈneːɦɾuː] ; juh-WAH-hurr-LAHL NE-hǝ-ROO; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat,[2] and author who was a central figure in India during the middle third of the 20th century. Nehru was a principal leader of the Indian nationalist movement in the 1930s and 1940s. Upon India's independence in 1947, he became the first prime minister of India, serving for 16 years. Nehru promoted parliamentary democracy, secularism, and science and technology during the 1950s, powerfully influencing India's arc as a modern nation. In international affairs, he steered India clear of the two blocs of the Cold War. A well-regarded author, his books written in prison, such as Letters from a Father to His Daughter (1929), Glimpses of World History (1934), An Autobiography (1936), and The Discovery of India (1946), have been read around the world. The honorific Pandit has been commonly applied before his name.

The son of Motilal Nehru, a prominent lawyer and Indian nationalist, Jawaharlal Nehru was educated in England—at Harrow School and Trinity College, Cambridge, and trained in the law at the Inner Temple. He became a barrister, returned to India, enrolled at the Allahabad High Court and gradually began to take an interest in national politics, which eventually became a full-time occupation. He joined the Indian National Congress, rose to become the leader of a progressive faction during the 1920s, and eventually of the Congress, receiving the support of Mahatma Gandhi who was to designate Nehru as his political heir. As Congress president in 1929, Nehru called for complete independence from the British Raj. Nehru and the Congress dominated Indian politics during the 1930s. Nehru promoted the idea of the secular nation-state in the 1937 Indian provincial elections, allowing the Congress to sweep the elections, and form governments in several provinces. In September 1939, the Congress ministries resigned to protest Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's decision to join the war without consulting them. After the All India Congress Committee's Quit India Resolution of 8 August 1942, senior Congress leaders were imprisoned and for a time the organisation was suppressed. Nehru, who had reluctantly heeded Gandhi's call for immediate independence, and had desired instead to support the Allied war effort during World War II, came out of a lengthy prison term to a much-altered political landscape. The Muslim League, under Muhammad Ali Jinnah, had come to dominate Muslim politics in the interim. In the 1946 provincial elections, Congress won the elections, but the League won all the seats reserved for Muslims, which the British interpreted to be a clear mandate for Pakistan in some form. Nehru became the interim prime minister of India in September 1946, with the League joining his government with some hesitancy in October 1946.

Upon India's independence on 15 August 1947, Nehru gave a critically acclaimed speech, "Tryst with Destiny"; he was sworn in as the Dominion of India's prime minister and raised the Indian flag at the Red Fort in Delhi. On 26 January 1950, when India became a republic within the Commonwealth of Nations, Nehru became the Republic of India's first prime minister. He embarked on an ambitious program of economic, social, and political reforms. Nehru promoted a pluralistic multi-party democracy. In foreign affairs, he played a leading role in establishing the Non-Aligned Movement, a group of nations that did not seek membership in the two main ideological blocs of the Cold War.

Under Nehru's leadership, the Congress emerged as a catch-all party, dominating national and state-level politics and winning elections in 1951, 1957 and 1962. He died as a result of a stroke on 27 May 1964. His birthday is celebrated as Children's Day in India.

Early life and career (1889–1912)

Birth and family background

Jawaharlal Nehru was born on 14 November 1889 in Allahabad in British India. His father, Motilal Nehru (1861–1931), a self-made wealthy barrister who belonged to the Kashmiri Pandit community, served twice as president of the Indian National Congress, in 1919 and 1928.[3] His mother, Swarup Rani Thussu (1868–1938), who came from a well-known Kashmiri Brahmin family settled in Lahore,[4] was Motilal's second wife, his first having died in childbirth. Jawaharlal was the eldest of three children.[5] The elder of his two sisters, Vijaya Lakshmi, was the first woman to become president of the United Nations General Assembly.[6] His youngest sister, Krishna Hutheesing, became a noted writer and authored several books on her brother.[7][8]

Childhood

Nehru described his childhood as a "sheltered and uneventful one". He grew up in an atmosphere of privilege in wealthy homes, including a palatial estate called the Anand Bhavan. His father had him educated at home by private governesses and tutors.[9] Influenced by the Irish theosophist Ferdinand T. Brooks' teaching,[10] Nehru became interested in science and theosophy.[11] A family friend, Annie Besant subsequently initiated him into the Theosophical Society at age thirteen. However, his interest in theosophy did not prove to be enduring, and he left the society shortly after Brooks departed as his tutor.[12] He wrote: "For nearly three years [Brooks] was with me and in many ways, he influenced me greatly".[11]

Nehru's theosophical interests induced him to study the Buddhist and Hindu scriptures.[13] According to B. R. Nanda, these scriptures were Nehru's "first introduction to the religious and cultural heritage of [India]....[They] provided Nehru the initial impulse for [his] long intellectual quest which culminated…in The Discovery of India."[13]

Youth

Nehru became a nationalist during his youth.[14] The Second Boer War and the Russo-Japanese War encouraged his nationalism. He wrote, "[The] Japanese victories [had] stirred up my enthusiasm. ... Nationalistic ideas filled my mind. ... I mused of Indian freedom and Asiatic freedom from the thraldom of Europe."[11] Later, in 1905, when he had begun his institutional schooling at Harrow, a leading school in England where he was nicknamed "Joe",[15] G. M. Trevelyan's Garibaldi books, which he had received as prizes for academic merit, influenced him greatly.[16] He viewed Garibaldi as a revolutionary hero. He wrote: "Visions of similar deeds in India came before, of [my] gallant fight for [Indian] freedom and in my mind, India and Italy got strangely mixed together."[11]

Graduation

Nehru went to Trinity College, Cambridge, in October 1907 and graduated with an honours degree in natural science in 1910.[17] During this period, he studied politics, economics, history and literature with interest. The writings of Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, John Maynard Keynes, Bertrand Russell, Lowes Dickinson and Meredith Townsend moulded much of his political and economic thinking.[11]

After completing his degree in 1910, Nehru moved to London and studied law at the Inner Temple Inn.[18] During this time, he continued to study Fabian Society scholars including Beatrice Webb.[11] He was called to the Bar in 1912.[18][19]

Advocate practice

After returning to India in August 1912, Nehru enrolled as an advocate of the Allahabad High Court and tried to settle down as a barrister. But, unlike his father, he had very little interest in his profession and relished neither the practice of law nor the company of lawyers: "Decidedly the atmosphere was not intellectually stimulating and a sense of the utter insipidity of life grew upon me."[11] His involvement in nationalist politics was to gradually replace his legal practice.[11]

Nationalist movement (1912–1938)

Britain and return to India: 1912–1913

Nehru had developed an interest in Indian politics during his time in Britain as a student and a barrister.[20] Within months of his return to India in 1912, Nehru attended an annual session of the Indian National Congress in Patna.[21] Congress in 1912 was the party of moderates and elites,[21] and he was disconcerted by what he saw as "very much an English-knowing upper-class affair".[22] Nehru doubted the effectiveness of Congress but agreed to work for the party in support of the Indian civil rights movement led by Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa,[23] collecting funds for the movement in 1913.[21] Later, he campaigned against indentured labour and discriminations faced by Indians in the British colonies.[24]

World War I: 1914–1915

When World War I broke out, sympathy in India was divided. Although educated Indians "by and large took a vicarious pleasure" in seeing the British rulers humbled, the ruling nobility sided with the Allies. Nehru confessed he viewed the war with mixed feelings. As Frank Moraes writes, "[i]f [Nehru's] sympathy was with any country it was with France, whose culture he greatly admired".[25] During the war, Nehru volunteered for the St. John Ambulance and worked as one of the organisation's provincial secretaries in Allahabad.[21] He also spoke out against the censorship acts passed by the British government in India.[26]

Nehru emerged from the war years as a leader whose political views were considered radical. Although the political discourse at the time had been dominated by the moderate, Gopal Krishna Gokhale,[23] who said that it was "madness to think of independence,"[21] Nehru had spoken, "openly of the politics of non-cooperation, of the need of resigning from honorary positions under the government and of not continuing the futile politics of representation".[27] He ridiculed the Indian Civil Service for supporting British policies, and agreed with a saying that it was "neither Indian, nor civil, nor a service".[28] Motilal Nehru, a prominent moderate leader, acknowledged the limits of constitutional agitation but counselled his son that there was no other "practical alternative" to it. Nehru, however, was dissatisfied with the pace of the national movement. He became involved with aggressive nationalists leaders demanding Home Rule for Indians.[29]

The influence of moderates on Congress' politics waned after Gokhale died in 1915.[21] Anti-moderate leaders like Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak took the opportunity to call for a national movement for Home Rule. However, in 1915, the proposal was rejected because of the reluctance of the moderates to commit to such a radical course of action.[30]

Home rule movement: 1916–1917

Nehru married Kamala Kaul in 1916. Their only daughter Indira was born a year later in 1917. Kamala gave birth to a boy in November 1924, but he lived for only a week.[31]

A Home Rule League was founded in September 1916 under the leadership of Annie Besant to voice a demand for self-governance, and to obtain the status of a Dominion within the British Empire as enjoyed at the time by Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Newfoundland. Tilak had already formed his own Home Rule League in April 1916.[21] Nehru joined both leagues, but worked primarily with Besant.[32] He became secretary of Besant's Home Rule League and remarked later that "[Besant] had a very powerful influence on me in my childhood ... even later when I entered political life her influence continued."[32][33]

In June 1917, the British government arrested and interned Besant. The Congress and other Indian organisations threatened to launch protests if she was not freed. Subsequently, the British government was forced to release Besant and make significant concessions after a period of intense protest.[34]

Meeting Gandhi: 1916–1919

In December 1916, the Congress made the Lucknow Pact with the Muslim League to support Hindu-Muslim unity. The pact had been discussed earlier in the year at a meeting held at the Nehru residence in Allahabad, and an agreement was reached at the annual session held in Lucknow.[32] Nehru first met Gandhi during the session. He was drawn to Gandhi's political leadership of the Champaran Satyagraha in 1917, but his father, Motilal, was reluctant to support political activity in contrivance of the law. In March 1919, Motilal Nehru invited Gandhi to his home in Allahabad to discuss his son's potential involvement in satyagraha campaigns.[35] Unwilling to alienate the influential Motilal Nehru, Gandhi counseled the younger Nehru to avoid direct participation. Nehru subsequently focused his activities writing for The Leader, a newspaper controlled by his father. However, Motilal Nehru soon lost control of The Leader, and started The Independent as a replacement. Nehru began writing for the new paper, and was briefly the editor before handing over to Bipin Chandra Pal.[36]

The Jallianwala Bagh killings occurred in Amritsar in April 1919 under the command of British brigadier general Michael O'Dwyer. Motilal Nehru was appointed by the Congress to head a public inquiry, and the younger Nehru was sent to Amritsar to gather information. On his return journey to Delhi by train, Nehru found himself sharing a compartment with O'Dwyer and other British officers. In Nehru's account, O'Dwyer claimed that "...he had the whole town at his mercy and he had felt like reducing the rebellious city to a heap of ashes, but he took pity on it and refrained..I was greatly shocked to hear his conversation and to observe his callous manner."[37]

Following the massacre, both Motilal and Jawaharal Nehru were radicalised, and became closely involved with Gandhi's political agitations. The family soon gave up luxury and western dress for the khadi and austerity advocated by Gandhi.[38][39] Motilal Nehru was elected President at the annual session of the Congress held in Amritsar in December 1919.[40]

Non-co-operation: 1920–1923

Nehru's first major national engagement came at the onset of the Non-cooperation movement in September 1920.[41] He played an influential role in directing political activities in the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh) and organising the peasantry. Nehru was arrested for the first time on 6 December 1921, on charges of anti-governmental activities. He was released a few months later.[42] The movement was gaining popularity, but its progress was suddenly halted as a result of the Chauri Chaura incident. On 4 February 1922, the police fired upon a group of protesters. In retaliation, the demonstrators attacked and set fire to a police station, which killed all of its occupants. In response, Gandhi halted political activities on 12 February, believing that his followers were not yet sufficiently trained in his principles of non-violent resistance. Nehru, who was still in prison when Gandhi made this decision, was disappointed, but ultimately agreed with the principle. He wrote to a colleague, "You will be glad to learn that work is flourishing. We are laying sure foundations this time... Rest assured that there will be no relaxation, no lessening in our activities and above all there will be no false compromise with Government."[43]

A few months after the movement ended, the British government arrested Gandhi. On 12 May 1922, Nehru was also again arrested by the government on charges of anti-governmental activities. He delivered the following statement[44]:

India will be free; of that there is no doubt. ... Jail has indeed become a heaven for us, a holy place of pilgrimage since our saintly and beloved leader was sentenced. ... I marvel at my good fortune. To serve India in the battle of freedom is honour enough. To serve her under a leader like Mahatma Gandhi is doubly fortunate. But to suffer for the dear country!! What greater good fortune could befall an Indian, unless it be death for the cause or the full realisation of our glorious dream?

Some Congress leaders and other Indian nationalists disagreed with Gandhi's decisions. These dissidents, including Motilal Nehru, contributed to the formation of the Swaraj Party by early 1923.[45] The Swaraj Party participated in the 1923 Indian general election under the Government of India Act 1919, which offered limited self-government in a system known as "dyarchy".

Nationalist movement: 1923–1926

Nehru's became a national figure by the end of the Non-cooperation movement.[46] He was released from jail at the end of January 1923, with a provisional amnesty. He was subsequently elected General Secretary of the All India Congress Committee in September 1923, and President of the United Provinces Provincial Congress Committee in October 1923.[47] Although the Congress avoided the main legislative bodies, the party agreed to contest municipal elections. In April 1923, Nehru was elected chairman of the Allahabad Municipal Board as a Congress member. He was selected after the party's first candidate, Purushottam Das Tandon, stood down due to opposition from the city's Muslim councillors.[48] The committee embraced the Nehru's ideology which was above sectarian prejudices. It unanimously opposed a suggestion to ban slaughter of cattle.[49] Nehru introduced Muhammad Iqbal's Sare Jahan se Accha to the school curriculum.[50] The anniversary of Tilak's death (1 August) and the day of Gandhi's sentencing (18 March) were declared public holidays while Empire Day was omitted.[49] Nehru opposed attempts by the municipality to segregate sex workers.[51] Nehru declared that they "are only one party to the transaction...if they were obliged to live only in a remote corner of the city, I would think it is equally reasonable to reserve another part of Allahabad for the men who exploit women and because of whom prostitution flourishes".[52] During this period, he also put efforts to improve schooling, sanitation, water supply and roads.[53]

British India included many territories ruled by Indian rulers, but under British paramountcy, called the princely states. In September 1923, Nehru visited the state of Nabha to observe the popular agitation after the British authorities deposed the Sikh maharaja, Ripudaman Singh.[54][55] Nehru was arrested and charged with illegally entering Nabha for taking part in "a criminal conspiracy". He was sentenced to two-and-a-half-years imprisonment, but this sentence was eventually dropped. Nehru's experience in Nabha influenced his consideration of popular movements in the princely states. The nationalist movement had been confined to the territories under direct British rule. He hoped to make the movement of the people in the princely states a part of the nationalist movement for independence, and this eventually contributed to his election as President of the All India States Peoples Conference (AISPC) in 1939.[54][56]

At the Kakinada session of the Congress in 1923, the Hindustani Seva Dal was established under N. S. Hardikar. The goal was to provide a "disciplined corps" of volunteers for the Congress.[57] The Dal was opposed by some party leaders, who considered it a potential militia-like organisation and thus inconsistent with Gandhian ethos.[58] Nehru was not among the detractors and agreed to become President. By 1931, the organisation was accepted by other Congress leaders. It was renamed the Seva Dal and brought under the aegis of the Congress Working Committee to become the party's central volunteer organisation. Each member underwent training in various subjects, including Indian history and labour relations. The corps was highly successful during the Civil Disobedience Movement, and remained under official censure even after British authorities lifted the general ban on the Congress in 1934.[59]

Europe: 1926-1927

Nehru became frustrated with his role as chairman of a municipal body. He resigned after two years and denounced municipal politics, stating "The main interest of Government in municipal administration is that "politics" should be kept out. Any resolution of sympathy with the nationalist movement is frowned upon."[60] In November 1924, Nehru's wife, Kamala, gave birth to an infant son that did not survive. Her health declined, and she began to develop symptoms of tuberculosis. Unhappy with the lack of political progress, Nehru decided to travel to Europe to seek treatment for his wife. On 1 March 1926, the couple and their daughter, Indira, departed for Switzerland. The family remained overseas for the next twenty months. They initially lived in Geneva. As Kamala showed little signs of improvement, Nehru later moved her to a sanatorium at Montana, in Valais, near Bex. While based in Montana, the family travelled across Europe. Nehru became acquainted with Indian expatriates, and corresponded with European intellectuals and politicians.[61] He wrote for the Journal de Genève, and also for the press back in India.[62]

In February 1927, Nehru was invited to Brussels to represent the Congress at the newly formed League against Imperialism (LAI). He was made an executive council member.[63][64] Increasingly, Nehru saw the struggle for independence from British imperialism as a multinational effort by the various colonies and dominions of the Empire; some of his statements on this matter, however, were interpreted as complicity with the rise of Hitler and his espoused intentions. Faced with these allegations, Nehru responded:[65]

We have sympathy for the national movement of Arabs in Palestine because it is directed against British Imperialism. Our sympathies cannot be weakened by the fact that the national movement coincides with Hitler's interests.

The LAI was dominated by socialists and communists, but also included other nationalists.[66] The meeting had been financed by the government of Mexico and the Kuomintang of China.[66] Nehru's public speeches articulated his understanding of imperialism, which drew more deeply from Marxist thought than previously. Nehru also interacted closely with the Chinese delegation and drafted a joint declaration that stressed a common cause against the British Empire.[67] Nehru was soon joined by his father, Motilal, in Europe. Nehru accepted an invitation to visit Moscow on the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. Motilal was less enthusiastic, but conceded and visited Moscow with his son and daughter-in-law for four days.[68] Nehru was impressed by Soviet architecture, as well as its economic development and ideological progress on class and gender.[68] Nehru would write a series of articles on the USSR in Indian papers, which were compiled in December 1928 under the title Soviet Russia: Some Random Sketches and Impressions.[69] In his book Towards Freedom, Nehru wrote that "the theory and philosophy of Marxism lightened up many a dark corner of my mind".[70] Nehru, however, remained sceptical of Soviet communism. In a secret report to the Congress back in India, Nehru indicated that the "Russians will try to utilize the League to further their owns ends", and "Personally I have the strongest objection to being led by the nose by the Russians or any-one else".[71] In 1930, the LAI condemned Gandhi's Delhi Statement. In response, Nehru instructed the Congress to break off correspondence with the LAI. He was expelled from membership in 1931.[72][73]

Nationalist movement: 1927–1928

Nehru returned to India in December 1927 and disembarked at Madras to attend the annual Congress party session.[74] He drafted a resolution that the Congress should aim for India's complete independence from the British Empire.[75] The resolution passed despite Gandhi's criticism, and was supported by a newer generation of Congress leaders who were more receptive to radical solutions.[76] Gandhi wrote to Nehru and disapproved of his association with radicals demanding complete independence.[77] Nehru replied that present strategies were proving ineffective and questioned Gandhi's leadership since the end of the Non-co-operation movement.[78] Over the next few months, Nehru and Gandhi would exchange terse letters about India's political future.[79]

In 1928, the Simon Commission arrived in India to discuss possible constitutional reforms for self-government. The Congress opposed the commission on the grounds that it did not include Indians. Nehru was opposed to continued aspirations for dominion status. In response to the Simon Commission, the All Parties Conference drafted the Nehru Report, named after Nehru's father, Motilal Nehru, who chaired the drafting committee. Published in August 1928, the report outlined proposals for an Indian constitution under dominion status. In response, Nehru helped form the "Independence for India League", a pressure group within the Congress.[80][81] In September 1928, Nehru wrote to a friend "that the Congress contains at least two if not more groups which have nothing in common between them and the sooner they break apart the better".[82] Nehru's group included Subhas Chandra Bose. However, Nehru's revolutionary spirit was tempered by his moderation. His father, who had rejoined the Congress and was the President in 1928, also cautioned him that "pure idealism divorced from realities has no place in politics".[83] In December 1928, Gandhi and Nehru finally compromised. Gandhi proposed a resolution that called for the British to grant Dominion status to India within two years. If the British failed to meet the deadline, the Congress would call upon all Indians to fight for complete independence. Nehru objected to the time given to the British—he pressed Gandhi to demand immediate actions from the British. Gandhi brokered a further compromise by reducing the time given from two years to one.[81]

Declaration of independence: 1929

Despite their disagreements, Gandhi encouraged Nehru to seek the Congress Presidency. Nehru was initially reluctant, and believed that the office would limit his political activity.[84] However, Gandhi persisted and eventually Nehru accepted his support. The British rejected demands for Dominion status in 1929.[81] Nehru assumed the presidency of the Congress party during the Lahore session on 29 December 1929, and introduced the successful resolution calling for complete independence.[81][85] Nehru drafted the Indian Declaration of Independence, which stated:

We believe that it is the inalienable right of the Indian people, as of any other people, to have freedom and to enjoy the fruits of their toil and have the necessities of life, so that they may have full opportunities for growth. We believe also that if any government deprives a people of these rights and oppresses them the people have a further right to alter it or abolish it. The British government in India has not only deprived the Indian people of their freedom but has based itself on the exploitation of the masses, and has ruined India economically, politically, culturally, and spiritually. We believe, therefore, that India must sever the British connection and attain Purna Swaraj or complete independence.[86]

At midnight on New Year's Eve 1929, Nehru hoisted the tricolour flag of India upon the banks of the Ravi in Lahore.[87] A pledge of independence was read out, which included a readiness to withhold taxes. The massive gathering of the public attending the ceremony was asked if they agreed with it, and the majority of people were witnessed raising their hands in approval. 172 Indian members of central and provincial legislatures resigned in support of the resolution and in accordance with Indian public sentiment. The Congress asked the people of India to observe 26 January as Independence Day.[88] Congress volunteers, nationalists, and the public hoisted the flag of India publicly across India. Plans for mass civil disobedience were also underway.[89]

After the Lahore session of the Congress in 1929, Nehru gradually emerged as the paramount leader of the Indian independence movement. Gandhi stepped back into a more spiritual role. Although Gandhi did not explicitly designate Nehru as his political heir until 1942, as early as the mid-1930s, the country saw Nehru as the natural successor to Gandhi.[90] As President, Nehru drafted the policies of the Congress and a future Indian nation in 1929.[91] He declared the aims of the congress were freedom of religion; right to form associations; freedom of expression of thought; equality before the law for every individual without distinction of caste, colour, creed, or religion; protection of regional languages and cultures, safeguarding the interests of the peasants and labour; abolition of untouchability; introduction of the adult franchise; imposition of prohibition, nationalisation of industries; socialism; and the establishment of a secular India.[92] All these aims formed the core of the "Fundamental Rights and Economic Policy" resolution drafted by Nehru in 1929–1931 and were ratified in 1931 by the Congress party session at Karachi chaired by Vallabhbhai Patel.[93]

Salt March: 1930

In early 1930, the Congress began planning civil disobedience to pressure the British authorities.[94] While Gandhi was planning a course of action, Nehru led the Congress in celebrating India's first 'independence day' on 26 January 1930 and hoisted the newly adopted tricolor flag.[95] Soon afterwards, Gandhi offered an 'Eleven Points' ultimatum to the British government; if the government would accept these points, Gandhi would call off civil disobedience. One of the 'Eleven Points' included the abolition of the British salt tax. Nehru was not enthusiastic about the 'Eleven Points' ultimatum and considered the demands too modest.[94] The government rejected the offer and Gandhi pressed ahead with civil disobedience through a satyagraha aimed at the salt tax. Most of the Congress leaders were ambivalent. Nehru wrote that "We were bewildered and could not quite fit in a national struggle with common salt."[96] After the protest had gathered steam, Nehru and other leaders realised the power of salt as a symbol. Nehru remarked about the unprecedented popular response, "It seemed as though a spring had been suddenly released".[97]

On 12 March, Gandhi set out from his ashram at Sabarmati for the small sea side village of Dandi. Nehru met Gandhi at Jambusar, about halfway between Sabarmati and Dandi.[98] After returning to Allahabad, Nehru made a speech to the country's youth:

The pilgrim marches onward. The field of battle lies before you, the flag of India beckons you, and freedom herself awaits your coming. Do you hesitate now, you who were but yesterday so loudly on her side? Will you be mere lookers-on in this glorious struggle and see your best and bravest face the might of a great empire which has crushed your country and her children? Who lives if India dies? Who dies if India lives?[98]

Gandhi broke the colonial salt law at Dandi on 6 April. Nehru was arrested on 14 April 1930 while on a train from Allahabad to Raipur. Earlier, after addressing a huge meeting and leading a vast procession, he had ceremoniously manufactured some contraband salt. He was charged with breach of the salt law and sentenced to six months of imprisonment at Central Jail.[99][100] Nehru nominated Gandhi to succeed him as the Congress president during his absence in jail, but Gandhi declined, and Nehru nominated his father as his successor.[101] With Nehru's arrest, the civil disobedience acquired a new tempo, and arrests, firing on crowds and lathi charges grew to be ordinary occurrences.[102]

The breach of the Salt Act soon became just one activity, and civil resistance spread to other fields. This was facilitated by the promulgation of various ordinances by the Viceroy prohibiting a number of activities. As these ordinances and prohibitions grew, the opportunities for breaking them also grew, and civil resistance took the form of doing the very thing that the ordinance was intended to stop.[103]

The salt satyagraha ("pressure for reform through passive resistance") succeeded in attracting world attention. Indian, British, and world opinion increasingly recognised the legitimacy of the claims by the Congress party for independence. Nehru considered the salt satyagraha the high-water mark of his association with Gandhi,[104] and felt its lasting importance was in changing the attitudes of Indians:[105]

Of course these movements exercised tremendous pressure on the British Government and shook the government machinery. But the real importance, to my mind, lay in the effect they had on our own people, and especially the village masses. ... Non-cooperation dragged them out of the mire and gave them self-respect and self-reliance. ... They acted courageously and did not submit so easily to unjust oppression; their outlook widened and they began to think a little in terms of India as a whole. ... It was a remarkable transformation and the Congress, under Gandhi's leadership, must have the credit for it.

Nationalist movement: 1931–1932

The first Round Table Conference organised by the British government to discuss India's political future began in London on 12 November 1930. The Congress did not attend, but Nehru and other prisoners were released on 26 January 1931 by orders of Lord Irwin, the viceroy of India.[106] On the day of his release, Nehru was informed that his father, Motilal, was seriously ill.[107] The family travelled to Lucknow to seek treatment. However, Motilal's health declined and he died in Lucknow on 6 February 1931, with his son and wife present.[107] On 5 March 1931, Gandhi signed a pact with Lord Irwin. Gandhi obtained some political concessions and agreed to end the Civil Disobedience Movement. Nehru was disappointed with the terms.[108] Political developments soon turned against the Congress. Lord Irwin left India to be succeeded by Lord Willingdon in April 1931.[109] Gandhi and Nehru met Lord Willingdon in Shimla before agreeing to participate in a second Round Table Conference. Nehru came away with the impression that the new viceroy shared his perception of the pact as a temporary truce.[110] In August 1931, a Conservative dominated National coalition came into power in the United Kingdom.[111] Lord Willingdon moved to suppress the Congress, with the support of the new Secretary of State for India.[112]

While Gandhi was in London, Nehru was accused of organising a "no-rent" political campaign against the British Raj.[112][113] Peasant agitations were occurring in the United Provinces. Tenant farmers were behind on rent, and facing evictions. They turned to the Congress for advice. Non-payment of rent was a possible solution, but this risked giving the government a justification to suppress the Congress.[114][115] Nehru brought the matter before British authorities.[114] The government made no concessions, and the Congress decided to recommend tenant farmers withhold rent.[114] The government introduced ordinances to suppress the "no-rent" agitation. Nehru was served with orders prohibiting him from leaving Allahabad and engaging in political activities [115] On 26 December 1931, Nehru was arrested for violating the order as he prepared to leave for Bombay to meet a returning Gandhi. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment.[112][115] The government accussed of Nehru of pursuing a "Leninite dictatorship".[112] Nehru's arrest was part of a larger measure against Indian nationalism. The Congress was once again declared illegal, and most leading Congress members were in jail by 10 January 1932. Gandhi himself was arrested under a 1827 Bombay ordinance revived by the government. Indian civil disobedience was renewed.[107]

Nationalist movement: 1933–1934

On 30 August 1933, Nehru was released from prison. He travelled to Pune to meet Gandhi. By this point, Nehru and Gandhi were growing apart. Nehru was vexed by Gandhi's anti-rational mysticism, and prioritisation of social movements over independence since the Communal Award of August 1932.[116] Nehru was also concerned by some of Gandhi's lieutenants that he considered reactionaries.[116] A diary entry from 18 July 1933 states "I am getting more and more certain there can be no further political co-operation between Bapu and me. At least not of the kind that existed. We had better go our different ways".[116] It was thought that Nehru might break with Gandhi, but the duo reconciled in Pune. Both publicly affirmed their trust in, and loyalty to, each other.[117] Nehru resumed his nationalist activities, and the British government moved to detain him once again. On 22 December 1933, the Home Secretary sent a memo to all local governments in India:

The Government of India regard him [Nehru] as by far the most dangerous element at large in India, and their view is that the time has come, in accordance with their general policy of taking steps at an early stage to prevent attempts to work up mass agitation, to take action against him.[118]

Government propaganda described Nehru as "the high priest of Communism".[119] The authorities remained fearful of his potential to attract followers to a revolutionary agitation. Various speeches made in late 1933 were examined as grounds for prosecution. Nehru's denunciation of the Raj at Calcutta in January 1934 gave the Bengal government the opportunity to change him with sedition. He was arrested on his return to Allahabad on 12 January and taken back to Calcutta. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment on 16 February.[118] In August 1934, Nehru was released for eleven days to attend to his wife's ailing health. He was sent back to prison when her health improved.[120] Nehru would end up spending most of the time between December 1931 and September 1935 in prison.[121]

Nationalist movement: 1934

On 7 April 1934, Gandhi officially called off the Civil Disobedience Movement.[122] The movement had been fading since Gandhi became preoccupied with social issues. Nehru was left bitterly disappointed by the decision. He wrote "...there is hardly any common ground between me and Bapu and the others who lead the Congress today. Our objectives are different, our ideals are different, and our methods are likely to be different".[123][124] Nehru adds that "...I felt with a stab of pain that the cords of allegiance that had bound me to him for many years had snapped."[125] The end of the movement was followed by Gandhi's announcement on 17 September 1934 that he was retiring from Congress politics in order to focus on social issues.[126] In the interim, the Swaraj Party had been reformed in May 1934 as a group within the Congress, with the support of Gandhi. The Swarajists aimed to contest the 1934 Indian general election[127][128] However, it was soon decided that the Congress itself would enter the elections, rather than the Swaraj Party on its behalf. To this end, a Congress Parliamentary Board was formed.[129]

The end of civil disobedience and the embrace of constitutionalism was a bitter blow for Nehru. The business community had been pressuring the Congress to revert to constitutionalism. In April 1934, Gandhi wrote to G. D. Birla that "There will always be a party within the Congress wedded to the idea of council-entry. The reigns of the Congress should be in the hands of that group."[128] The business community was determined to secure influence with the party and office holders. Nehru became unhappy at the anti-socialist orientation of the Congress leadership.[123][124] He wrote:

The Congress had become a caucus where opportunism flourished and the Working Committee's resolution condemning socialism showed such astounding ignorance of even the elements of the subject that it was painful to read it and realize that it might be read outside India. It seemed that the overmastering desire of the Committee was somehow to assure various vested interests even at the risk of talking nonsense.[119]

Nehru questioned the sincerity of constitutionalism. He complained that there were constitutionalists who had avoided civil disobedience when politics was unsafe and now sought office.[130] Nehru was also greatly concerned at this time by the growth of communalism. He was critical of religious organisations whom he saw as putting their sectarian interests above the national one of independence.[131] The competition for office would only widen communal tensions.[132]

In response to events, socialists formed the Congress Socialist Party faction within the Congress in May 1934. The group included Jayaprakash Narayan, Narendra Deo, Rammanohar Lohia, Minoo Masani, Yusuf Meherally, Asoka Mehta, and Achyut Patwardhan. This group made no secret that they sought and drew inspiration from Nehru.[119] Masani wrote to Nehru in prison:

...the group in its proposed form would carry out the purpose you have in mind... a programme that would be socialist in action and objective...The group would do socialist propaganda among rank and file with a view to converting the Congress to an acceptance of socialism.[133]

Nehru replied that "I would welcome the formation of a socialist group in the Congress... I feel the time has come when the country should face the issues and come to grips with real economic problems which ultimately matter."[133] However, Nehru declined to join the group.[133] According to Sarvepalli Gopal, Nehru actually considered their decision to form the group premature, and likely to distract from the national goal of independence.[119] Nevertheless, Nehru's position allowed him to become a bridge between the socialists and Gandhi.[134]

Europe: 1935–1936

Kamala was very ill by 1935. In May, she travelled to Germany to seek further treatment, and was accompanied by her daughter Indira.[135] Nehru was released early from prison on compassionate grounds in September 1935, and travelled to Badenweiler to be with his family. While on a visit to England in the fall, Nehru learned that he was Congress president-elect starting in December 1936. He was torn over whether to remain with his family, or accept the presidency. On 31 January, Kamala was moved to a sanatorium near Lausanne to be closer to Indira, who was studying at Bex.[136] On 28 February 1936, Kamala died, with Nehru by her side.[136] In March 1936, Nehru returned to India, having accepted the presidency. He stopped in Rome on his way back, and was visited by an Italian official. Nehru learned that Mussolini wanted to meet him personally to convey condolences. He wrote to Mussolini, thanking him for his message of condolence, but stated that he could not accept his invitation.[136]

While in Europe, Nehru travelled to England and France, and met with several intellectuals and politicians.[136] He became very concerned with the possibility of another world war. At that time, he emphasised that, in the event of war, India's place was alongside the democracies, though he insisted India could only fight in support of Great Britain and France as a free country.[137]

Nehru's trip to Europe happened to be a turning point in his political and economic mindset. It's the visit that stimulated his interest in Marxism and his socialist thought pattern.[138] Time later spent incarcerated enabled him to research Marxism more deeply. Appealed by its ideas but repelled by some of its tactics, he never could bring himself to buy Karl Marx's words as revealed gospel.[139] However, from that time on, the benchmark of his economic view remained Marxist, adapted, where necessary, to Indian circumstances. After returning to India, Nehru gave a speech to the Congress and referenced the Soviet Union as a model of economic development.[140]

Nationalist movement: 1936-1938

Nehru returned to India in March 1936 as Congress president-elect. In the interim, the British parliament had passed the Government of India Act 1935 as a response to political agitation. During the party's annual session at Lucknow in December 1936, the Congress debated whether to contest 1937 provincial elections to be held under the act.[141][142] Nehru opposed participation and described the act as a "new charter of bondage" and a "machine with strong brakes but no engine".[143][144] He believed that the act was designed to weaken the Congress and obstruct Indian nationalism.[145] At the Lucknow session, Nehru warned:

It is always dangerous to assume responsibility without power. It will be far worse with this constitution hedged in with safeguards and reserved powers and mortgaged funds, where we have to follow the rules and regulations of our opponents’ making. Imperialism sometimes talks of co-operation, but the kind of co-operation it wants is usually known as surrender, and the ministers who accept office will have to do so at the price of surrender of much that they might have stood for in public.[145]

Other Congress leaders joined with Nehru in condemning act, but wished to contest the elections. They resolved to defer the question of office acceptance for a later date.[145] Nehru reluctantly agreed to lead the election campaign as President. While leading the campaign, Nehru was re-elected for another term as Congress President at the annual session held at Faizabad in December 1937.[146]

The 1937 elections brought the Congress party to power in a majority of the provinces, with increased popularity and power for Nehru. Since the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah (who was to become the creator of Pakistan) had fared badly at the polls, Nehru declared that the only two parties that mattered in India were the British colonial authorities and the Congress. Jinnah's statements that the Muslim League was the third and "equal partner" within Indian politics were widely rejected.[147] Nehru had hoped to elevate Maulana Azad as the preeminent leader of Indian Muslims, but Gandhi, who continued to treat Jinnah as the voice of Indian Muslims, undermined him in this.[148][149]