Atheism: Difference between revisions

remove repetition |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

Please note: |

Please note: |

||

The consensus since April 2007 has been to include all three of the definitions of atheism presented in the first paragraph below. They are the result of extensive debate and searches through existing sources – see, for example, the archived talkpage threads [[Talk:Atheism/Archive 27#A survey of definitions for atheism]] and [[Talk:Atheism/Archive 29#List of definitions]] – and formed part of the article when it achieved "Featured Article" status. |

The consensus since April 2007 has been to include all three of the definitions of atheism presented in the first paragraph below. They are the result of extensive debate and searches through existing sources – see, for example, the archived talkpage threads [[Talk:Atheism/Archive 27#A survey of definitions for atheism]] and [[Talk:Atheism/Archive 29#List of definitions]] – and formed part of the article when it achieved "Featured Article" status. |

||

Please, therefore, do not change the contents of the first paragraph without prior discussion on the talk page ([[Talk:Atheism]]), preferably after consulting at least these two threads. If you do make changes to the paragraph without prior discussion, be prepared to see them reverted as an invitation to discussion on the talk page (see [[Wikipedia:BRD]]). |

Please, therefore, do not change the contents of the first paragraph without prior discussion on the talk page ([[Talk:Atheism]]), preferably after consulting at least these two threads. If you do make changes to the paragraph without prior discussion, be prepared to see them reverted as an invitation to discussion on the talk page (see [[Wikipedia:BRD]]). |

||

-----> |

-----> |

||

'''Atheism''' is, in the broadest sense, an absence of [[belief]] in the existence of [[Deity|deities]].<ref name="encyc-unbelief-def-issues" /><ref name="oxdicphil" /><ref name="religioustolerance" /><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/atheism |encyclopedia=[[OxfordDictionaries.com]] |title=Atheism |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |accessdate=April 23, 2017 |date= |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160911080901/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/atheism |archivedate=September 11, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist.<ref name="eb2011-atheism" /><ref name="encyc-philosophy" /> In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities.<ref name="encyc-unbelief-def-issues" /><ref name="oxdicphil" /><ref name="RoweRoutledge" /><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/#1 |encyclopedia=[[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]] |title=Atheism and Agnosticism |publisher= Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University|accessdate= |author=J.J.C. Smart |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161211005616/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/#1 |archivedate=December 11, 2016 |url-status=live |author-link=J.J.C. Smart |year=2017 }}</ref> Atheism is contrasted with [[theism]],<ref name="reldef" /><ref name="OED-theism" /> which, in its most general form, is the belief that [[Existence of God|at least one deity exists]].<ref name="OED-theism">{{cite book |title=Oxford English Dictionary |edition=2nd |year=1989 |quote=Belief in a deity, or deities, as opposed to atheism}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/theism |title=Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary |quote=...belief in the existence of a god or gods... |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514194441/http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/theism |archivedate=May 14, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Smart |first=J.J.C. |title=Atheism and Agnosticism |publisher=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2013 Edition) |editor-last=Zalta |editor-first=Edward N. |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2013/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |access-date=April 26, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131202055749/http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2013/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |archive-date=December 2, 2013 |url-status=live |date=March 9, 2004 }}</ref> |

'''Atheism''' is, in the broadest sense, an absence of [[belief]] in the existence of [[Deity|deities]].<ref name="encyc-unbelief-def-issues" /><ref name="oxdicphil" /><ref name="religioustolerance" /><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/atheism |encyclopedia=[[OxfordDictionaries.com]] |title=Atheism |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |accessdate=April 23, 2017 |date= |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160911080901/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/atheism |archivedate=September 11, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist.<ref name="eb2011-atheism" /><ref name="encyc-philosophy" /> In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities.<ref name="encyc-unbelief-def-issues" /><ref name="oxdicphil" /><ref name="RoweRoutledge" /><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/#1 |encyclopedia=[[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]] |title=Atheism and Agnosticism |publisher= Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University|accessdate= |author=J.J.C. Smart |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161211005616/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/#1 |archivedate=December 11, 2016 |url-status=live |author-link=J.J.C. Smart |year=2017 }}</ref> Atheism is contrasted with [[theism]],<ref name="reldef" /><ref name="OED-theism" /> which, in its most general form, is the belief that [[Existence of God|at least one deity exists]].<ref name="OED-theism">{{cite book |title=Oxford English Dictionary |edition=2nd |year=1989 |quote=Belief in a deity, or deities, as opposed to atheism}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/theism |title=Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary |quote=...belief in the existence of a god or gods... |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514194441/http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/theism |archivedate=May 14, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Smart |first=J.J.C. |title=Atheism and Agnosticism |publisher=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2013 Edition) |editor-last=Zalta |editor-first=Edward N. |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2013/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |access-date=April 26, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131202055749/http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2013/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |archive-date=December 2, 2013 |url-status=live |date=March 9, 2004 }}</ref> |

||

The [[etymology|etymological]] root for the word ''atheism'' originated before the 5th century BCE from the ancient Greek {{lang|grc|[[:wikt:ἄθεος|ἄθεος]]}} (''atheos''), meaning "without god(s)". In antiquity, it had multiple uses as a pejorative term applied to those thought to reject the gods worshiped by the larger society,<ref name="drachmann" /> those who were forsaken by the gods, or those who had no commitment to belief in the gods.<ref name="Battling Whitmarsh" /> The term denoted a social category created by orthodox religionists into which those who did not share their religious beliefs were placed.<ref name="Battling Whitmarsh">{{cite book |last1=Whitmarsh |first1=Tim |title=Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World |publisher=Knopf Doubleday |isbn=978-0-307-94877-9 |chapter=8. Atheism on Trial |year=2016}}</ref> The actual term ''atheism'' emerged first in the 16th century.<ref name="Hunter ch 1">{{cite book |last=Wootton |first=David|editor1-last=Hunter|editor1-first=Michael|editor2-last=Wootton|editor2-first=David |title=Atheism from the Reformation to the Enlightenment |date=1992 |publisher=Clarendon Press |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-822736-6 |chapter=1. New Histories of Atheism}}</ref> With the spread of [[freethought]], [[skeptical inquiry]], and subsequent increase in [[criticism of religion]], application of the term narrowed in scope. The [[List of atheist philosophers|first individuals]] to identify themselves using the word ''atheist'' lived in the 18th century during the [[Age of Enlightenment]].{{sfn|Armstrong|1999}}<ref name="Hunter ch 1" /> The [[French Revolution]], noted for its "unprecedented atheism," witnessed the first major political movement in history to advocate for the supremacy of human [[reason]].<ref name="HancockLambert">{{cite book |last=Hancock |first=Ralph |title=The Legacy of the French Revolution |year=1996 |publisher=Rowman and Littlefield Publishers |location=Lanham, Massachusetts |isbn=978-0-8476-7842-6 |page=22 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uPgQy3VJ3iIC |accessdate=May 30, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150930072801/https://books.google.com/books?id=uPgQy3VJ3iIC |archive-date=September 30, 2015 |url-status=live }} [https://books.google.com/books?id=uPgQy3VJ3iIC&pg=PA22 Extract of page 22] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150929042900/https://books.google.com/books?id=uPgQy3VJ3iIC&pg=PA22 |date=September 29, 2015 }}</ref> |

The [[etymology|etymological]] root for the word ''atheism'' originated before the 5th century BCE from the ancient Greek {{lang|grc|[[:wikt:ἄθεος|ἄθεος]]}} (''atheos''), meaning "without god(s)". In antiquity, it had multiple uses as a pejorative term applied to those thought to reject the gods worshiped by the larger society,<ref name="drachmann" /> those who were forsaken by the gods, or those who had no commitment to belief in the gods.<ref name="Battling Whitmarsh" /> The term denoted a social category created by orthodox religionists into which those who did not share their religious beliefs were placed.<ref name="Battling Whitmarsh">{{cite book |last1=Whitmarsh |first1=Tim |title=Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World |publisher=Knopf Doubleday |isbn=978-0-307-94877-9 |chapter=8. Atheism on Trial |year=2016}}</ref> The actual term ''atheism'' emerged first in the 16th century.<ref name="Hunter ch 1">{{cite book |last=Wootton |first=David|editor1-last=Hunter|editor1-first=Michael|editor2-last=Wootton|editor2-first=David |title=Atheism from the Reformation to the Enlightenment |date=1992 |publisher=Clarendon Press |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-822736-6 |chapter=1. New Histories of Atheism}}</ref> With the spread of [[freethought]], [[skeptical inquiry]], and subsequent increase in [[criticism of religion]], application of the term narrowed in scope. The [[List of atheist philosophers|first individuals]] to identify themselves using the word ''atheist'' lived in the 18th century during the [[Age of Enlightenment]].{{sfn|Armstrong|1999}}<ref name="Hunter ch 1" /> The [[French Revolution]], noted for its "unprecedented atheism," witnessed the first major political movement in history to advocate for the supremacy of human [[reason]].<ref name="HancockLambert">{{cite book |last=Hancock |first=Ralph |title=The Legacy of the French Revolution |year=1996 |publisher=Rowman and Littlefield Publishers |location=Lanham, Massachusetts |isbn=978-0-8476-7842-6 |page=22 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uPgQy3VJ3iIC |accessdate=May 30, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150930072801/https://books.google.com/books?id=uPgQy3VJ3iIC |archive-date=September 30, 2015 |url-status=live }} [https://books.google.com/books?id=uPgQy3VJ3iIC&pg=PA22 Extract of page 22] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150929042900/https://books.google.com/books?id=uPgQy3VJ3iIC&pg=PA22 |date=September 29, 2015 }}</ref> |

||

Arguments for atheism range from philosophical to social and historical approaches. Rationales for not believing in deities include arguments that there is a lack of [[Existence of God#Empirical arguments|empirical evidence]],<ref name="logical" /><ref>{{cite web |url=http://shook.pragmatism.org/skepticismaboutthesupernatural.pdf |title=Skepticism about the Supernatural |last=Shook |first=John R. |accessdate=October 2, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121018210402/http://shook.pragmatism.org/skepticismaboutthesupernatural.pdf |archive-date=October 18, 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> the [[problem of evil]], the [[argument from inconsistent revelations]], the rejection of concepts that cannot [[Falsifiability|be falsified]], and the [[argument from nonbelief]].<ref name="logical" /><ref name="Drange-1996" /> Nonbelievers contend that atheism is a more [[parsimonious]] position than theism and that everyone is born without beliefs in deities;<ref name="encyc-unbelief-def-issues" /> therefore, they argue that the [[Philosophic burden of proof|burden of proof]] lies not on the atheist to disprove the existence of gods but on the theist to provide a rationale for theism.<ref>{{harvnb|Stenger|2007|pp=17–18}}, citing {{cite book |last=Parsons |first=Keith M. |title=God and the Burden of Proof: Plantinga, Swinburne, and the Analytical Defense of Theism |year=1989 |location=Amherst, New York |publisher=Prometheus Books |isbn=978-0-87975-551-5}}</ref> Although some atheists have adopted [[Secularism|secular]] philosophies (e.g. [[secular humanism]]),<ref name="honderich" /><ref>{{cite book |last=Fales |first=Evan |title=Naturalism and Physicalism |postscript=,}} in {{harvnb|Martin|2006|pp=122–131}}.</ref> there is no ideology or code of conduct to which all atheists adhere.<ref>{{harvnb|Baggini|2003|pp=3–4}}.</ref> |

Arguments for atheism range from philosophical to social and historical approaches. Rationales for not believing in deities include arguments that there is a lack of [[Existence of God#Empirical arguments|empirical evidence]],<ref name="logical" /><ref>{{cite web |url=http://shook.pragmatism.org/skepticismaboutthesupernatural.pdf |title=Skepticism about the Supernatural |last=Shook |first=John R. |accessdate=October 2, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121018210402/http://shook.pragmatism.org/skepticismaboutthesupernatural.pdf |archive-date=October 18, 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> the [[problem of evil]], the [[argument from inconsistent revelations]], the rejection of concepts that cannot [[Falsifiability|be falsified]], and the [[argument from nonbelief]].<ref name="logical" /><ref name="Drange-1996" /> Nonbelievers contend that atheism is a more [[parsimonious]] position than theism and that everyone is born without beliefs in deities;<ref name="encyc-unbelief-def-issues" /> therefore, they argue that the [[Philosophic burden of proof|burden of proof]] lies not on the atheist to disprove the existence of gods but on the theist to provide a rationale for theism.<ref>{{harvnb|Stenger|2007|pp=17–18}}, citing {{cite book |last=Parsons |first=Keith M. |title=God and the Burden of Proof: Plantinga, Swinburne, and the Analytical Defense of Theism |year=1989 |location=Amherst, New York |publisher=Prometheus Books |isbn=978-0-87975-551-5}}</ref> Although some atheists have adopted [[Secularism|secular]] philosophies (e.g. [[secular humanism]]),<ref name="honderich" /><ref>{{cite book |last=Fales |first=Evan |title=Naturalism and Physicalism |postscript=,}} in {{harvnb|Martin|2006|pp=122–131}}.</ref> there is no ideology or code of conduct to which all atheists adhere.<ref>{{harvnb|Baggini|2003|pp=3–4}}.</ref> |

||

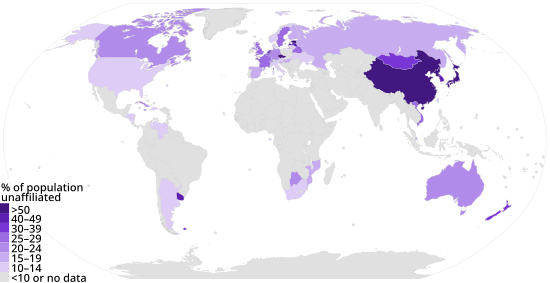

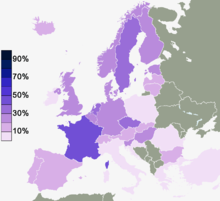

Since conceptions of atheism vary, accurate estimations of current [[Demographics of atheism|numbers of atheists]] are difficult.<ref name="Martin2007">{{cite book |last=Zuckerman |first=Phil |editor=Martin, Michael T |title=The Cambridge Companion to Atheism |year=2007 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-60367-6 |ol=22379448M |page=56 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tAeFipOVx4MC&pg=PA56 |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151031223718/https://books.google.com/books?id=tAeFipOVx4MC&pg=PA56 |archive-date=October 31, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> According to global [[WIN/GIA|Win-Gallup International]] studies, 13% of respondents were "convinced atheists" in 2012,<ref name="WIN/GIA">{{cite web |author=<!--none specified--> |url=http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/14/file/14.pdf |title=Religiosity and Atheism Index |publisher=[[WIN/GIA]] |date=July 27, 2012 |location=Zurich |accessdate=October 1, 2013 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131021065544/http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/14/file/14.pdf |archivedate=October 21, 2013 }}</ref> 11% were "convinced atheists" in 2015,<ref name="wingia2">{{cite web |author=<!--none specified--> |url=https://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2015/04/13/399338834/new-survey-shows-the-worlds-most-and-least-religious-places |title=New Survey Shows the World's Most and Least Religious Places |publisher=[[NPR]] |date=April 13, 2015 |accessdate=April 29, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150506110630/http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2015/04/13/399338834/new-survey-shows-the-worlds-most-and-least-religious-places |archive-date=May 6, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> and in 2017, 9% were "convinced atheists".<ref name="WINGIA 2017" /> However, other researchers have advised caution with WIN/Gallup figures since other surveys which have used the same wording for decades and have a bigger sample size have consistently reached lower figures.<ref name="Demographics Oxford Keysar">{{cite book |last1=Keysar |first1=Ariela |last2=Navarro-Rivera |first2=Juhem|editor1-last=Bullivant|editor1-first=Stephen|editor2-last=Ruse|editor2-first=Michael |title=The Oxford Handbook of Atheism |date=2017 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-964465-0 |chapter=36. A World of Atheism: Global Demographics}}</ref> An older survey by the [[British Broadcasting Corporation]] (BBC) in 2004 recorded atheists as comprising 8% of the world's population.<ref name="BBC-2004-demographics" /> Other older estimates have indicated that atheists comprise 2% of the world's population, while the [[Irreligion|irreligious]] add a further 12%.<ref name="eb2007-demographics" /> According to these polls, Europe and East Asia are the regions with the highest rates of atheism. In 2015, 61% of people in China reported that [[Irreligion in China|they were atheists]].<ref name="GallupInternational">{{cite web |title=Gallup International Religiosity Index |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/files/2015/04/WIN.GALLUP-INTERNATIONAL-RELIGIOUSITY-INDEX.pdf |website=Washington Post |publisher=WIN-Gallup International |date=April 2015 |access-date=January 9, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160201065414/https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/files/2015/04/WIN.GALLUP-INTERNATIONAL-RELIGIOUSITY-INDEX.pdf |archive-date=February 1, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> The figures for a 2010 [[Eurobarometer]] survey in the [[European Union]] (EU) reported that 20% of the EU population claimed not to believe in "any sort of spirit, God or life force", with France (40%) and Sweden (34%) representing the highest values.<ref name="EU">{{cite book |author= |title=Social values, Science and Technology |publisher=Directorate General Research, European Union |year=2010 |pages=207 |url=http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_341_en.pdf |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110430163128/http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_225_report_en.pdf |archivedate=April 30, 2011 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

Since conceptions of atheism vary, accurate estimations of current [[Demographics of atheism|numbers of atheists]] are difficult.<ref name="Martin2007">{{cite book |last=Zuckerman |first=Phil |editor=Martin, Michael T |title=The Cambridge Companion to Atheism |year=2007 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-60367-6 |ol=22379448M |page=56 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tAeFipOVx4MC&pg=PA56 |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151031223718/https://books.google.com/books?id=tAeFipOVx4MC&pg=PA56 |archive-date=October 31, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> According to global [[WIN/GIA|Win-Gallup International]] studies, 13% of respondents were "convinced atheists" in 2012,<ref name="WIN/GIA">{{cite web |author=<!--none specified--> |url=http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/14/file/14.pdf |title=Religiosity and Atheism Index |publisher=[[WIN/GIA]] |date=July 27, 2012 |location=Zurich |accessdate=October 1, 2013 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131021065544/http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/14/file/14.pdf |archivedate=October 21, 2013 }}</ref> 11% were "convinced atheists" in 2015,<ref name="wingia2">{{cite web |author=<!--none specified--> |url=https://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2015/04/13/399338834/new-survey-shows-the-worlds-most-and-least-religious-places |title=New Survey Shows the World's Most and Least Religious Places |publisher=[[NPR]] |date=April 13, 2015 |accessdate=April 29, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150506110630/http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2015/04/13/399338834/new-survey-shows-the-worlds-most-and-least-religious-places |archive-date=May 6, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> and in 2017, 9% were "convinced atheists".<ref name="WINGIA 2017" /> However, other researchers have advised caution with WIN/Gallup figures since other surveys which have used the same wording for decades and have a bigger sample size have consistently reached lower figures.<ref name="Demographics Oxford Keysar">{{cite book |last1=Keysar |first1=Ariela |last2=Navarro-Rivera |first2=Juhem|editor1-last=Bullivant|editor1-first=Stephen|editor2-last=Ruse|editor2-first=Michael |title=The Oxford Handbook of Atheism |date=2017 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-964465-0 |chapter=36. A World of Atheism: Global Demographics}}</ref> An older survey by the [[British Broadcasting Corporation]] (BBC) in 2004 recorded atheists as comprising 8% of the world's population.<ref name="BBC-2004-demographics" /> Other older estimates have indicated that atheists comprise 2% of the world's population, while the [[Irreligion|irreligious]] add a further 12%.<ref name="eb2007-demographics" /> According to these polls, Europe and East Asia are the regions with the highest rates of atheism. In 2015, 61% of people in China reported that [[Irreligion in China|they were atheists]].<ref name="GallupInternational">{{cite web |title=Gallup International Religiosity Index |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/files/2015/04/WIN.GALLUP-INTERNATIONAL-RELIGIOUSITY-INDEX.pdf |website=Washington Post |publisher=WIN-Gallup International |date=April 2015 |access-date=January 9, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160201065414/https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/files/2015/04/WIN.GALLUP-INTERNATIONAL-RELIGIOUSITY-INDEX.pdf |archive-date=February 1, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> The figures for a 2010 [[Eurobarometer]] survey in the [[European Union]] (EU) reported that 20% of the EU population claimed not to believe in "any sort of spirit, God or life force", with France (40%) and Sweden (34%) representing the highest values.<ref name="EU">{{cite book |author= |title=Social values, Science and Technology |publisher=Directorate General Research, European Union |year=2010 |pages=207 |url=http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_341_en.pdf |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110430163128/http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_225_report_en.pdf |archivedate=April 30, 2011 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

== Definitions and types == |

== Definitions and types == |

||

[[File:AtheismImplicitExplicit3.svg|thumb|A diagram showing the relationship between the definitions of [[Weak and strong atheism|weak/strong]] and [[Implicit and explicit atheism|implicit/explicit]] atheism. |

[[File:AtheismImplicitExplicit3.svg|thumb|A diagram showing the relationship between the definitions of [[Weak and strong atheism|weak/strong]] and [[Implicit and explicit atheism|implicit/explicit]] atheism. |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

<br /> |

<br /> |

||

(Sizes in the diagram are not meant to indicate relative sizes within a population.)]] |

(Sizes in the diagram are not meant to indicate relative sizes within a population.)]] |

||

Writers disagree on how best to define and classify ''atheism'',<ref name="eb1911-atheism" /> contesting what supernatural entities are considered gods, whether it is a philosophic position in its own right or merely the absence of one, and whether it requires a conscious, explicit rejection. Atheism has been regarded as compatible with [[agnosticism]],<ref name="agnosticism-compatible" /><ref name="flint-agnostic-atheism" /><ref name="encyc-unbelief-compatible" /><ref name="martin-agnosticism-entails" /><ref name="barker-agnostic-atheism" /><ref name="besant-open-to-new-truth" /><ref name="holyoake-question-of-probability" /> but has also been contrasted with it.<ref name="eb2011-atheism-critique" /><ref name="eb2011concise-atheism" /><ref name="eb1911-atheism-sceptical" /> A variety of categories have been used to distinguish the different forms of atheism. |

Writers disagree on how best to define and classify ''atheism'',<ref name="eb1911-atheism" /> contesting what supernatural entities are considered gods, whether it is a philosophic position in its own right or merely the absence of one, and whether it requires a conscious, explicit rejection. Atheism has been regarded as compatible with [[agnosticism]],<ref name="agnosticism-compatible" /><ref name="flint-agnostic-atheism" /><ref name="encyc-unbelief-compatible" /><ref name="martin-agnosticism-entails" /><ref name="barker-agnostic-atheism" /><ref name="besant-open-to-new-truth" /><ref name="holyoake-question-of-probability" /> but has also been contrasted with it.<ref name="eb2011-atheism-critique" /><ref name="eb2011concise-atheism" /><ref name="eb1911-atheism-sceptical" /> A variety of categories have been used to distinguish the different forms of atheism. |

||

=== Range === |

=== Range === |

||

Some of the ambiguity and controversy involved in defining ''atheism'' arises from difficulty in reaching a consensus for the definitions of words like ''deity'' and ''god''. The variety of wildly different [[conceptions of God]] and deities leads to differing ideas regarding atheism's applicability. The ancient Romans accused Christians of being atheists for not worshiping the [[paganism|pagan]] deities. Gradually, this view fell into disfavor as ''theism'' came to be understood as encompassing belief in any divinity.{{sfn|Martin|2006}} |

Some of the ambiguity and controversy involved in defining ''atheism'' arises from difficulty in reaching a consensus for the definitions of words like ''deity'' and ''god''. The variety of wildly different [[conceptions of God]] and deities leads to differing ideas regarding atheism's applicability. The ancient Romans accused Christians of being atheists for not worshiping the [[paganism|pagan]] deities. Gradually, this view fell into disfavor as ''theism'' came to be understood as encompassing belief in any divinity.{{sfn|Martin|2006}} |

||

With respect to the range of phenomena being rejected, atheism may counter anything from the existence of a deity, to the existence of any [[spirituality|spiritual]], [[supernatural]], or [[Transcendence (religion)|transcendental]] concepts, such as those of [[Buddhism]], [[Hinduism]], [[Jainism]], and [[Taoism]].<ref name="eb2011-Rejection-of-all-religious-beliefs" /> |

With respect to the range of phenomena being rejected, atheism may counter anything from the existence of a deity, to the existence of any [[spirituality|spiritual]], [[supernatural]], or [[Transcendence (religion)|transcendental]] concepts, such as those of [[Buddhism]], [[Hinduism]], [[Jainism]], and [[Taoism]].<ref name="eb2011-Rejection-of-all-religious-beliefs" /> |

||

=== Implicit vs. explicit === |

=== Implicit vs. explicit === |

||

{{Main|Implicit and explicit atheism}} |

{{Main|Implicit and explicit atheism}} |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

For the purposes of his paper on "philosophical atheism", [[Ernest Nagel]] contested including the mere absence of theistic belief as a type of atheism.<ref name= Nagel1959>{{cite book |title=Basic Beliefs: The Religious Philosophies of Mankind |chapter=Philosophical Concepts of Atheism |first=Ernest |last=Nagel |authorlink=Ernest Nagel |year=1959 |publisher=Sheridan House |quote=I must begin by stating what sense I am attaching to the word "atheism," and how I am construing the theme of this paper. I shall understand by "atheism" a critique and a denial of the major claims of all varieties of theism. ... atheism is not to be identified with sheer unbelief, or with disbelief in some particular creed of a religious group. Thus, a child who has received no religious instruction and has never heard about God is not an atheist – for he is not denying any theistic claims. Similarly in the case of an adult who, if he has withdrawn from the faith of his father without reflection or because of frank indifference to any theological issue, is also not an atheist – for such an adult is not challenging theism and not professing any views on the subject. ... I propose to examine some ''philosophic'' concepts of atheism ...}} |

For the purposes of his paper on "philosophical atheism", [[Ernest Nagel]] contested including the mere absence of theistic belief as a type of atheism.<ref name= Nagel1959>{{cite book |title=Basic Beliefs: The Religious Philosophies of Mankind |chapter=Philosophical Concepts of Atheism |first=Ernest |last=Nagel |authorlink=Ernest Nagel |year=1959 |publisher=Sheridan House |quote=I must begin by stating what sense I am attaching to the word "atheism," and how I am construing the theme of this paper. I shall understand by "atheism" a critique and a denial of the major claims of all varieties of theism. ... atheism is not to be identified with sheer unbelief, or with disbelief in some particular creed of a religious group. Thus, a child who has received no religious instruction and has never heard about God is not an atheist – for he is not denying any theistic claims. Similarly in the case of an adult who, if he has withdrawn from the faith of his father without reflection or because of frank indifference to any theological issue, is also not an atheist – for such an adult is not challenging theism and not professing any views on the subject. ... I propose to examine some ''philosophic'' concepts of atheism ...}} |

||

<br />reprinted in ''Critiques of God'', edited by Peter A. Angeles, Prometheus Books, 1997.</ref> [[Graham Oppy]] classifies as ''innocents'' those who never considered the question because they lack any understanding of what a god is. According to Oppy, these could be [[Infant cognitive development|one-month-old babies]], humans with severe traumatic [[Brain injury|brain injuries]], or patients with [[dementia|advanced dementia]].{{sfn|Oppy|2018|p=4|ps=: Agnostics are distinguished from innocents, who also neither believe that there are gods nor believe that there are no gods, by the fact that they have given consideration to the question of whether there are gods. Innocents are those who have never considered the question of whether there are gods. Typically, innocents have never considered the question of whether there are gods because they are not able to consider that question. How could that be? Well, in order to consider the question of whether there are gods, one must understand what it would mean for something to be a god. That is, one needs to have the concept of a god. Those who lack the concept of a god are not able to entertain the thought that there are gods. Consider, for example, one-month-old babies. It is very plausible that one-month-old babies lack the concept of a god. So it is very plausible that one-month-old babies are innocents. Other plausible cases of innocents include chimpanzees, human beings who have suffered severe traumatic brain injuries, and human beings with advanced dementia}} |

<br />reprinted in ''Critiques of God'', edited by Peter A. Angeles, Prometheus Books, 1997.</ref> [[Graham Oppy]] classifies as ''innocents'' those who never considered the question because they lack any understanding of what a god is. According to Oppy, these could be [[Infant cognitive development|one-month-old babies]], humans with severe traumatic [[Brain injury|brain injuries]], or patients with [[dementia|advanced dementia]].{{sfn|Oppy|2018|p=4|ps=: Agnostics are distinguished from innocents, who also neither believe that there are gods nor believe that there are no gods, by the fact that they have given consideration to the question of whether there are gods. Innocents are those who have never considered the question of whether there are gods. Typically, innocents have never considered the question of whether there are gods because they are not able to consider that question. How could that be? Well, in order to consider the question of whether there are gods, one must understand what it would mean for something to be a god. That is, one needs to have the concept of a god. Those who lack the concept of a god are not able to entertain the thought that there are gods. Consider, for example, one-month-old babies. It is very plausible that one-month-old babies lack the concept of a god. So it is very plausible that one-month-old babies are innocents. Other plausible cases of innocents include chimpanzees, human beings who have suffered severe traumatic brain injuries, and human beings with advanced dementia}} |

||

=== Positive vs. negative === |

=== Positive vs. negative === |

||

{{Main|Negative and positive atheism}} |

{{Main|Negative and positive atheism}} |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

The terms ''weak'' and ''strong'' are relatively recent, while the terms ''negative'' and ''positive'' atheism are of older origin, having been used (in slightly different ways) in the philosophical literature<ref name="presumption" /> and in Catholic apologetics.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.nd.edu/Departments/Maritain/jm3303.htm |title=On the Meaning of Contemporary Atheism |journal=The Review of Politics |first=Jacques |last=Maritain |date=July 1949 |volume=11 |issue=3 |pages=267–280 |doi=10.1017/S0034670500044168 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20051113062053/http://www.nd.edu/Departments/Maritain/jm3303.htm |archivedate=November 13, 2005}}</ref> |

The terms ''weak'' and ''strong'' are relatively recent, while the terms ''negative'' and ''positive'' atheism are of older origin, having been used (in slightly different ways) in the philosophical literature<ref name="presumption" /> and in Catholic apologetics.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.nd.edu/Departments/Maritain/jm3303.htm |title=On the Meaning of Contemporary Atheism |journal=The Review of Politics |first=Jacques |last=Maritain |date=July 1949 |volume=11 |issue=3 |pages=267–280 |doi=10.1017/S0034670500044168 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20051113062053/http://www.nd.edu/Departments/Maritain/jm3303.htm |archivedate=November 13, 2005}}</ref> |

||

Under this demarcation of atheism, most agnostics qualify as negative atheists. |

Under this demarcation of atheism, most agnostics qualify as negative atheists. |

||

While Martin, for example, asserts that [[agnosticism]] [[logical consequence|entails]] negative atheism,<ref name="martin-agnosticism-entails" /> many agnostics see their view as distinct from atheism,<ref name=Kenny2006 /><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/omar-baddar/why-im-not-an-atheist-the-case-for-agnosticism_b_3345544.html |title=Why I'm Not an Atheist: The Case for Agnosticism |date=May 28, 2013 |publisher=Huffington Post |accessdate=November 26, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131209105433/http://www.huffingtonpost.com/omar-baddar/why-im-not-an-atheist-the-case-for-agnosticism_b_3345544.html |archive-date=December 9, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

While Martin, for example, asserts that [[agnosticism]] [[logical consequence|entails]] negative atheism,<ref name="martin-agnosticism-entails" /> many agnostics see their view as distinct from atheism,<ref name=Kenny2006 /><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/omar-baddar/why-im-not-an-atheist-the-case-for-agnosticism_b_3345544.html |title=Why I'm Not an Atheist: The Case for Agnosticism |date=May 28, 2013 |publisher=Huffington Post |accessdate=November 26, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131209105433/http://www.huffingtonpost.com/omar-baddar/why-im-not-an-atheist-the-case-for-agnosticism_b_3345544.html |archive-date=December 9, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

which they may consider no more justified than theism or requiring an equal conviction.<ref name=Kenny2006>{{cite book |first=Anthony |last=Kenny |authorlink=Anthony Kenny |title=What I believe |chapter=Why I Am Not an Atheist |publisher=Continuum |isbn=978-0-8264-8971-5 |quote=The true default position is neither theism nor atheism, but agnosticism ... a claim to knowledge needs to be substantiated; ignorance need only be confessed. |year=2006}}</ref> |

which they may consider no more justified than theism or requiring an equal conviction.<ref name=Kenny2006>{{cite book |first=Anthony |last=Kenny |authorlink=Anthony Kenny |title=What I believe |chapter=Why I Am Not an Atheist |publisher=Continuum |isbn=978-0-8264-8971-5 |quote=The true default position is neither theism nor atheism, but agnosticism ... a claim to knowledge needs to be substantiated; ignorance need only be confessed. |year=2006}}</ref> |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

Australian philosopher [[J.J.C. Smart]] even argues that "sometimes a person who is really an atheist may describe herself, even passionately, as an agnostic because of unreasonable generalized [[philosophical skepticism]] which would preclude us from saying that we know anything whatever, except perhaps the truths of mathematics and formal logic."<ref name="stanford">{{cite web |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |title=Atheism and Agnosticism |first=J.C.C. |last=Smart |date=March 9, 2004 |publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/654hYPmzk?url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |archive-date=January 30, 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

Australian philosopher [[J.J.C. Smart]] even argues that "sometimes a person who is really an atheist may describe herself, even passionately, as an agnostic because of unreasonable generalized [[philosophical skepticism]] which would preclude us from saying that we know anything whatever, except perhaps the truths of mathematics and formal logic."<ref name="stanford">{{cite web |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |title=Atheism and Agnosticism |first=J.C.C. |last=Smart |date=March 9, 2004 |publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/654hYPmzk?url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/ |archive-date=January 30, 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

Consequently, some atheist authors such as [[Richard Dawkins]] prefer distinguishing theist, agnostic and atheist positions along a [[spectrum of theistic probability]]—the likelihood that each assigns to the statement "God exists".{{sfn|Dawkins|2006|p=50}} |

Consequently, some atheist authors such as [[Richard Dawkins]] prefer distinguishing theist, agnostic and atheist positions along a [[spectrum of theistic probability]]—the likelihood that each assigns to the statement "God exists".{{sfn|Dawkins|2006|p=50}} |

||

=== Definition as impossible or impermanent === |

=== Definition as impossible or impermanent === |

||

Before the 18th century, the existence of God was so accepted in the Western world that even the possibility of true atheism was questioned. This is called ''theistic [[innatism]]''—the notion that all people believe in God from birth; within this view was the connotation that atheists are simply in denial.<ref>{{cite book |last=Cudworth |first=Ralph |authorlink=Ralph Cudworth |title=The True Intellectual System of the Universe: the first part, wherein all the reason and philosophy of atheism is confuted and its impossibility demonstrated |year=1678}}</ref> |

Before the 18th century, the existence of God was so accepted in the Western world that even the possibility of true atheism was questioned. This is called ''theistic [[innatism]]''—the notion that all people believe in God from birth; within this view was the connotation that atheists are simply in denial.<ref>{{cite book |last=Cudworth |first=Ralph |authorlink=Ralph Cudworth |title=The True Intellectual System of the Universe: the first part, wherein all the reason and philosophy of atheism is confuted and its impossibility demonstrated |year=1678}}</ref> |

||

There is also a position claiming that atheists are quick to believe in God in times of crisis, that atheists make [[deathbed conversion]]s, or that "[[there are no atheists in foxholes]]".<ref>See, for example: {{cite news |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/features/ohair090896.htm |title=Atheist Group Moves Ahead Without O'Hair |first=Sue Anne |last=Pressley |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=September 8, 1996 |accessdate=October 22, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171008044601/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/features/ohair090896.htm |archive-date=October 8, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

There is also a position claiming that atheists are quick to believe in God in times of crisis, that atheists make [[deathbed conversion]]s, or that "[[there are no atheists in foxholes]]".<ref>See, for example: {{cite news |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/features/ohair090896.htm |title=Atheist Group Moves Ahead Without O'Hair |first=Sue Anne |last=Pressley |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=September 8, 1996 |accessdate=October 22, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171008044601/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/features/ohair090896.htm |archive-date=October 8, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

There have, however, been examples to the contrary, among them examples of literal "atheists in foxholes".<ref>{{cite web |last=Lowder |first=Jeffery Jay |year=1997 |title=Atheism and Society |url=http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/jeff_lowder/society.html |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110522025011/http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/jeff_lowder/society.html |archivedate=May 22, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

There have, however, been examples to the contrary, among them examples of literal "atheists in foxholes".<ref>{{cite web |last=Lowder |first=Jeffery Jay |year=1997 |title=Atheism and Society |url=http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/jeff_lowder/society.html |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110522025011/http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/jeff_lowder/society.html |archivedate=May 22, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Some atheists have challenged the need for the term "atheism". In his book ''[[Letter to a Christian Nation]]'', [[Sam Harris (author)|Sam Harris]] wrote: |

Some atheists have challenged the need for the term "atheism". In his book ''[[Letter to a Christian Nation]]'', [[Sam Harris (author)|Sam Harris]] wrote: |

||

<blockquote>In fact, "atheism" is a term that should not even exist. No one ever needs to identify himself as a "non-[[Astrology|astrologer]]" or a "non-[[Alchemy|alchemist]]". We do not have words for people who doubt that Elvis is still alive or that aliens have traversed the galaxy only to molest ranchers and their cattle. Atheism is nothing more than the noises reasonable people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.{{sfn|Harris|2006|p=[https://books.google.com/?id=ypyMZlkgHGIC&pg=PA51&dq=%22No+one+ever+needs+to+identify+himself+as+a+%22non-astrologer%22%22or+a%22%22non-alchemist%22 51]}}</blockquote> |

<blockquote>In fact, "atheism" is a term that should not even exist. No one ever needs to identify himself as a "non-[[Astrology|astrologer]]" or a "non-[[Alchemy|alchemist]]". We do not have words for people who doubt that Elvis is still alive or that aliens have traversed the galaxy only to molest ranchers and their cattle. Atheism is nothing more than the noises reasonable people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.{{sfn|Harris|2006|p=[https://books.google.com/?id=ypyMZlkgHGIC&pg=PA51&dq=%22No+one+ever+needs+to+identify+himself+as+a+%22non-astrologer%22%22or+a%22%22non-alchemist%22 51]}}</blockquote> |

||

=== Pragmatic atheism === |

=== Pragmatic atheism === |

||

Pragmatic atheism is the view one should reject a belief in a god or gods because it is unnecessary for a [[Pragmatism|pragmatic]] life. This view is related to [[apatheism]] and [[practical atheism]].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://atheism.about.com/od/Atheist-Dictionary/g/Definition-Pragmatic-Atheist.htm |title=What is a Pragmatic Atheist? |access-date=November 24, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161124091404/http://atheism.about.com/od/Atheist-Dictionary/g/Definition-Pragmatic-Atheist.htm |archive-date=November 24, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

Pragmatic atheism is the view one should reject a belief in a god or gods because it is unnecessary for a [[Pragmatism|pragmatic]] life. This view is related to [[apatheism]] and [[practical atheism]].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://atheism.about.com/od/Atheist-Dictionary/g/Definition-Pragmatic-Atheist.htm |title=What is a Pragmatic Atheist? |access-date=November 24, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161124091404/http://atheism.about.com/od/Atheist-Dictionary/g/Definition-Pragmatic-Atheist.htm |archive-date=November 24, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

== Academic studies on atheism == |

|||

=== Suicide and Depression === |

|||

Atheism and agnostic beliefs result in suicidal thoughts. Atheist doctors and non-religious hospitals also were more likely to recommend suicide to their patients.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lizardi|first=D.|last2=Gearing|first2=R. E.|date=2010-09-01|title=Religion and Suicide: Buddhism, Native American and African Religions, Atheism, and Agnosticism|url=https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-009-9248-8|journal=Journal of Religion and Health|language=en|volume=49|issue=3|pages=377–384|doi=10.1007/s10943-009-9248-8|issn=1573-6571}}</ref> Atheists have the highest rate of suicide in the world, followed by Buddhists, Christians and Hindus. Muslims have the lowest rates due to being more religious.<ref>Bertolote, J. M., & Fleischmann, A. (2002). A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide. ''Suicidologi'', ''7''(2).</ref> Other studies have found atheism results in less meaning in life and less feeling of a purpose in life, which results in worsening mental health, which in turn results in a lower quality of life.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Peres|first=Mario Fernando Prieto|last2=Kamei|first2=Helder H.|last3=Tobo|first3=Patricia R.|last4=Lucchetti|first4=Giancarlo|date=2018-10-01|title=Mechanisms Behind Religiosity and Spirituality’s Effect on Mental Health, Quality of Life and Well-Being|url=https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0400-6|journal=Journal of Religion and Health|language=en|volume=57|issue=5|pages=1842–1855|doi=10.1007/s10943-017-0400-6|issn=1573-6571}}</ref> A similar study from Germany found that being an atheist makes one more unhappy than being a poor person, and over all are the most unhappiest group.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Edinger-Schons|first=Laura Marie|date=2019-04-11|title=Oneness beliefs and their effect on life satisfaction.|url=https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037/rel0000259|journal=Psychology of Religion and Spirituality|language=en|doi=10.1037/rel0000259|issn=1943-1562}}</ref> |

|||

=== Drug Abuse === |

|||

Scientific studies have shown atheism results in higher rates of drug use as well as more likely to be friends with drug users. Being involved in religious community organizations and praying had the biggest effect on decreasing drug use.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bahr|first=Stephen J.|last2=Maughan|first2=Suzanne L.|last3=Marcos|first3=Anastasios C.|last4=Li|first4=Bingdao|date=1998|title=Family, Religiosity, and the Risk of Adolescent Drug Use|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/353639|journal=Journal of Marriage and Family|volume=60|issue=4|pages=979–992|doi=10.2307/353639|issn=0022-2445}}</ref> A meta-analysis found that atheism resulted in higher rates of marijuana use, alcoholism, and smoking.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Yonker|first=Julie E.|last2=Schnabelrauch|first2=Chelsea A.|last3=DeHaan|first3=Laura G.|date=2012-04-01|title=The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140197111001138|journal=Journal of Adolescence|series=The cross-cultural significance of control and autonomy in parent-adolescent relationships|language=en|volume=35|issue=2|pages=299–314|doi=10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.010|issn=0140-1971}}</ref> |

|||

=== Views of God === |

|||

Despite self-reporting they did not believe in God, when atheists dared God to bring harm upon them, they felt as much fear as religious people, but did not have the same fear when daring Santa Clause to do the same or wishing for the harm to happen<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lindeman|first=Marjaana|last2=Heywood|first2=Bethany|last3=Riekki|first3=Tapani|last4=Makkonen|first4=Tommi|date=2014-04-03|title=Atheists Become Emotionally Aroused When Daring God to Do Terrible Things|url=https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2013.771991|journal=The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion|volume=24|issue=2|pages=124–132|doi=10.1080/10508619.2013.771991|issn=1050-8619}}</ref> |

|||

== Arguments == |

== Arguments == |

||

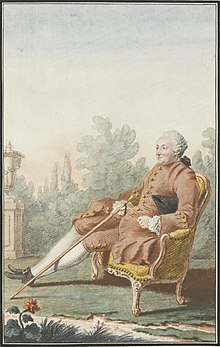

[[File:D'Holbach.jpg|thumb|[[Baron d'Holbach|Paul Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach]], an 18th-century advocate of atheism. |

[[File:D'Holbach.jpg|thumb|[[Baron d'Holbach|Paul Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach]], an 18th-century advocate of atheism. |

||

<br /> <br /> |

<br /> <br /> |

||

"The source of man's unhappiness is his ignorance of Nature. The pertinacity with which he clings to blind opinions imbibed in his infancy, which interweave themselves with his existence, the consequent prejudice that warps his mind, that prevents its expansion, that renders him the slave of fiction, appears to doom him to continual error."<ref>Paul Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach, ''System of Nature; or, the Laws of the Moral and Physical World'' (London, 1797), Vol. 1, p. 25</ref>]] |

"The source of man's unhappiness is his ignorance of Nature. The pertinacity with which he clings to blind opinions imbibed in his infancy, which interweave themselves with his existence, the consequent prejudice that warps his mind, that prevents its expansion, that renders him the slave of fiction, appears to doom him to continual error."<ref>Paul Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach, ''System of Nature; or, the Laws of the Moral and Physical World'' (London, 1797), Vol. 1, p. 25</ref>]] |

||

=== Epistemological arguments === |

=== Epistemological arguments === |

||

{{Further|Agnostic atheism|Theological noncognitivism}} |

{{Further|Agnostic atheism|Theological noncognitivism}} |

||

Atheists have also argued that people cannot know a God or prove the existence of a God. The latter is called agnosticism, which takes a variety of forms. In the philosophy of [[immanence]], divinity is inseparable from the world itself, including a person's mind, and each person's [[consciousness]] is locked in the [[Subject (philosophy)|subject]]. According to this form of agnosticism, this limitation in perspective prevents any objective inference from belief in a god to assertions of its existence. The [[Rationalism|rationalistic]] agnosticism of [[Immanuel Kant|Kant]] and the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]] only accepts knowledge deduced with human rationality; this form of atheism holds that gods are not discernible as a matter of principle, and therefore cannot be known to exist. [[Skepticism]], based on the ideas of [[David Hume|Hume]], asserts that certainty about anything is impossible, so one can never know for sure whether or not a god exists. Hume, however, held that such unobservable metaphysical concepts should be rejected as "sophistry and illusion".<ref name="hume-metaphysics" /> The allocation of agnosticism to atheism is disputed; it can also be regarded as an independent, basic worldview.<ref name="Zdybicka-p20">{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=20}}.</ref> |

Atheists have also argued that people cannot know a God or prove the existence of a God. The latter is called agnosticism, which takes a variety of forms. In the philosophy of [[immanence]], divinity is inseparable from the world itself, including a person's mind, and each person's [[consciousness]] is locked in the [[Subject (philosophy)|subject]]. According to this form of agnosticism, this limitation in perspective prevents any objective inference from belief in a god to assertions of its existence. The [[Rationalism|rationalistic]] agnosticism of [[Immanuel Kant|Kant]] and the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]] only accepts knowledge deduced with human rationality; this form of atheism holds that gods are not discernible as a matter of principle, and therefore cannot be known to exist. [[Skepticism]], based on the ideas of [[David Hume|Hume]], asserts that certainty about anything is impossible, so one can never know for sure whether or not a god exists. Hume, however, held that such unobservable metaphysical concepts should be rejected as "sophistry and illusion".<ref name="hume-metaphysics" /> The allocation of agnosticism to atheism is disputed; it can also be regarded as an independent, basic worldview.<ref name="Zdybicka-p20">{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=20}}.</ref> |

||

Other arguments for atheism that can be classified as epistemological or [[ontology|ontological]], including [[ignosticism]], assert the meaninglessness or unintelligibility of basic terms such as "God" and statements such as "God is all-powerful." [[Theological noncognitivism]] holds that the statement "God exists" does not express a proposition, but is nonsensical or cognitively meaningless. It has been argued both ways as to whether such individuals can be classified into some form of atheism or agnosticism. Philosophers [[Alfred Ayer|A.J. Ayer]] and [[Theodore M. Drange]] reject both categories, stating that both camps accept "God exists" as a proposition; they instead place noncognitivism in its own category.<ref>[[Theodore Drange|Drange, Theodore M.]] (1998). "[http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/theodore_drange/definition.html Atheism, Agnosticism, Noncognitivism] {{Webarchive|url=https://www.webcitation.org/6GW3XHMxP?url=http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/theodore_drange/definition.html |date=10 May 2013 }}". [[Internet Infidels]], ''Secular Web Library''. Retrieved 2007-APR-07.</ref><ref>[[Alfred Ayer|Ayer, A. J.]] (1946). ''Language, Truth and Logic''. Dover. pp. 115–116. In a footnote, Ayer attributes this view to "Professor H.H. Price".</ref> |

Other arguments for atheism that can be classified as epistemological or [[ontology|ontological]], including [[ignosticism]], assert the meaninglessness or unintelligibility of basic terms such as "God" and statements such as "God is all-powerful." [[Theological noncognitivism]] holds that the statement "God exists" does not express a proposition, but is nonsensical or cognitively meaningless. It has been argued both ways as to whether such individuals can be classified into some form of atheism or agnosticism. Philosophers [[Alfred Ayer|A.J. Ayer]] and [[Theodore M. Drange]] reject both categories, stating that both camps accept "God exists" as a proposition; they instead place noncognitivism in its own category.<ref>[[Theodore Drange|Drange, Theodore M.]] (1998). "[http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/theodore_drange/definition.html Atheism, Agnosticism, Noncognitivism] {{Webarchive|url=https://www.webcitation.org/6GW3XHMxP?url=http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/theodore_drange/definition.html |date=10 May 2013 }}". [[Internet Infidels]], ''Secular Web Library''. Retrieved 2007-APR-07.</ref><ref>[[Alfred Ayer|Ayer, A. J.]] (1946). ''Language, Truth and Logic''. Dover. pp. 115–116. In a footnote, Ayer attributes this view to "Professor H.H. Price".</ref> |

||

=== Metaphysical arguments === |

=== Metaphysical arguments === |

||

{{Further|Monism|Physicalism}} |

{{Further|Monism|Physicalism}} |

||

Philosopher, [[Zofia Zdybicka]] writes: |

Philosopher, [[Zofia Zdybicka]] writes: |

||

{{quote|"Metaphysical atheism ... includes all doctrines that hold to metaphysical monism (the homogeneity of reality). Metaphysical atheism may be either: a) absolute — an explicit denial of God's existence associated with materialistic monism (all materialistic trends, both in ancient and modern times); b) relative — the implicit denial of God in all philosophies that, while they accept the existence of an absolute, conceive of the absolute as not possessing any of the attributes proper to God: transcendence, a personal character or unity. Relative atheism is associated with idealistic monism (pantheism, panentheism, deism)."<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=19}}.</ref>}} |

{{quote|"Metaphysical atheism ... includes all doctrines that hold to metaphysical monism (the homogeneity of reality). Metaphysical atheism may be either: a) absolute — an explicit denial of God's existence associated with materialistic monism (all materialistic trends, both in ancient and modern times); b) relative — the implicit denial of God in all philosophies that, while they accept the existence of an absolute, conceive of the absolute as not possessing any of the attributes proper to God: transcendence, a personal character or unity. Relative atheism is associated with idealistic monism (pantheism, panentheism, deism)."<ref>{{harvnb|Zdybicka|2005|p=19}}.</ref>}} |

||

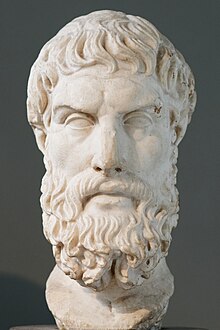

[[File:Epikouros BM 1843.jpg|thumb|left|[[Epicurus]] is credited with first expounding the [[problem of evil]]. [[David Hume]] in his ''[[Dialogues concerning Natural Religion]]'' (1779) cited Epicurus in stating the argument as a series of questions:{{sfn|Hume|1779}} |

[[File:Epikouros BM 1843.jpg|thumb|left|[[Epicurus]] is credited with first expounding the [[problem of evil]]. [[David Hume]] in his ''[[Dialogues concerning Natural Religion]]'' (1779) cited Epicurus in stating the argument as a series of questions:{{sfn|Hume|1779}} |

||

"Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?"]] |

"Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?"]] |

||

=== Logical arguments === |

=== Logical arguments === |

||

{{further|Existence of God#Arguments against the existence of God|l1=Arguments against the existence of God|Problem of evil|Argument from nonbelief|l3=Divine hiddenness}} |

{{further|Existence of God#Arguments against the existence of God|l1=Arguments against the existence of God|Problem of evil|Argument from nonbelief|l3=Divine hiddenness}} |

||

Some atheists hold the view that the various [[conceptions of God|conceptions of gods]], such as the [[personal god]] of Christianity, are ascribed logically inconsistent qualities. Such atheists present [[existence of God#Deductive arguments|deductive arguments]] against the existence of God, which assert the incompatibility between certain traits, such as perfection, creator-status, [[immutability (theology)|immutability]], [[omniscience]], [[omnipresence]], [[omnipotence]], [[omnibenevolence]], [[transcendence (philosophy)|transcendence]], personhood (a personal being), non-physicality, [[justice]], and [[mercy]].<ref name=logical>{{cite web |author=Various authors |url=http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/nontheism/atheism/logical.html |title=Logical Arguments for Atheism |publisher=[[Internet Infidels]] |website=The Secular Web Library |accessdate=October 2, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121117012714/http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/nontheism/atheism/logical.html |archive-date=November 17, 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

Some atheists hold the view that the various [[conceptions of God|conceptions of gods]], such as the [[personal god]] of Christianity, are ascribed logically inconsistent qualities. Such atheists present [[existence of God#Deductive arguments|deductive arguments]] against the existence of God, which assert the incompatibility between certain traits, such as perfection, creator-status, [[immutability (theology)|immutability]], [[omniscience]], [[omnipresence]], [[omnipotence]], [[omnibenevolence]], [[transcendence (philosophy)|transcendence]], personhood (a personal being), non-physicality, [[justice]], and [[mercy]].<ref name=logical>{{cite web |author=Various authors |url=http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/nontheism/atheism/logical.html |title=Logical Arguments for Atheism |publisher=[[Internet Infidels]] |website=The Secular Web Library |accessdate=October 2, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121117012714/http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/nontheism/atheism/logical.html |archive-date=November 17, 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

[[Theodicy|Theodicean]] atheists believe that the world as they experience it cannot be reconciled with the qualities commonly ascribed to God and gods by theologians. They argue that an [[omniscience|omniscient]], [[omnipotence|omnipotent]], and [[omnibenevolence|omnibenevolent]] God is not compatible with a world where there is [[problem of evil|evil]] and [[suffering]], and where divine love is [[Divine hiddenness|hidden]] from many people.<ref name="Drange-1996">{{cite web |first=Theodore M. |last=Drange |authorlink=Theodore Drange |year=1996 |url=http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/theodore_drange/aeanb.html |title=The Arguments From Evil and Nonbelief |publisher=[[Internet Infidels]] |website=Secular Web Library |accessdate=October 2, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070110135633/http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/theodore_drange/aeanb.html |archive-date=January 10, 2007 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

[[Theodicy|Theodicean]] atheists believe that the world as they experience it cannot be reconciled with the qualities commonly ascribed to God and gods by theologians. They argue that an [[omniscience|omniscient]], [[omnipotence|omnipotent]], and [[omnibenevolence|omnibenevolent]] God is not compatible with a world where there is [[problem of evil|evil]] and [[suffering]], and where divine love is [[Divine hiddenness|hidden]] from many people.<ref name="Drange-1996">{{cite web |first=Theodore M. |last=Drange |authorlink=Theodore Drange |year=1996 |url=http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/theodore_drange/aeanb.html |title=The Arguments From Evil and Nonbelief |publisher=[[Internet Infidels]] |website=Secular Web Library |accessdate=October 2, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070110135633/http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/theodore_drange/aeanb.html |archive-date=January 10, 2007 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

A similar argument is attributed to [[Siddhartha Gautama]], the founder of [[Buddhism]].<ref>V.A. Gunasekara, {{cite web |url=http://www.buddhistinformation.com/buddhist_attitude_to_god.htm |title=The Buddhist Attitude to God |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080102053643/http://www.buddhistinformation.com/buddhist_attitude_to_god.htm |archivedate=January 2, 2008}} In the Bhuridatta Jataka, "The Buddha argues that the three most commonly given attributes of God, viz. omnipotence, omniscience and benevolence towards humanity cannot all be mutually compatible with the existential fact of dukkha."</ref> |

A similar argument is attributed to [[Siddhartha Gautama]], the founder of [[Buddhism]].<ref>V.A. Gunasekara, {{cite web |url=http://www.buddhistinformation.com/buddhist_attitude_to_god.htm |title=The Buddhist Attitude to God |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080102053643/http://www.buddhistinformation.com/buddhist_attitude_to_god.htm |archivedate=January 2, 2008}} In the Bhuridatta Jataka, "The Buddha argues that the three most commonly given attributes of God, viz. omnipotence, omniscience and benevolence towards humanity cannot all be mutually compatible with the existential fact of dukkha."</ref> |

||

=== Reductionary accounts of religion === |

=== Reductionary accounts of religion === |

||

{{Further|Evolutionary origin of religions|Evolutionary psychology of religion|Psychology of religion}} |

{{Further|Evolutionary origin of religions|Evolutionary psychology of religion|Psychology of religion}} |

||

Philosopher [[Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach|Ludwig Feuerbach]]<ref>Feuerbach, Ludwig (1841) ''[[The Essence of Christianity]]''</ref> |

Philosopher [[Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach|Ludwig Feuerbach]]<ref>Feuerbach, Ludwig (1841) ''[[The Essence of Christianity]]''</ref> |

||

and psychoanalyst [[Sigmund Freud]] have argued that God and other religious beliefs are human inventions, created to fulfill various psychological and emotional wants or needs, or a projection mechanism from the 'Id' omnipotence; for [[Vladimir Lenin]], in 'Materialism and Empirio-criticism', against the [[Russian Machism]], the followers of [[Ernst Mach]], Feuerbach was the final argument against belief in a god. This is also a view of many [[Buddhism|Buddhists]].<ref>Walpola Rahula, ''What the Buddha Taught.'' Grove Press, 1974. pp. 51–52.</ref> [[Karl Marx]] and [[Friedrich Engels]], influenced by the work of Feuerbach, argued that belief in God and religion are social functions, used by those in power to oppress the working class. According to [[Mikhail Bakunin]], "the idea of God implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation of human liberty, and necessarily ends in the enslavement of mankind, in theory, and practice." He reversed [[Voltaire]]'s aphorism that if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him, writing instead that "if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish him."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/bakunin/godandstate/godandstate_ch1.html |title=God and the State |last=Bakunin |first=Michael |authorlink=Michael Bakunin |year=1916 |website= |publisher=New York: Mother Earth Publishing Association |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110521195435/http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/bakunin/godandstate/godandstate_ch1.html |archivedate=May 21, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

and psychoanalyst [[Sigmund Freud]] have argued that God and other religious beliefs are human inventions, created to fulfill various psychological and emotional wants or needs, or a projection mechanism from the 'Id' omnipotence; for [[Vladimir Lenin]], in 'Materialism and Empirio-criticism', against the [[Russian Machism]], the followers of [[Ernst Mach]], Feuerbach was the final argument against belief in a god. This is also a view of many [[Buddhism|Buddhists]].<ref>Walpola Rahula, ''What the Buddha Taught.'' Grove Press, 1974. pp. 51–52.</ref> [[Karl Marx]] and [[Friedrich Engels]], influenced by the work of Feuerbach, argued that belief in God and religion are social functions, used by those in power to oppress the working class. According to [[Mikhail Bakunin]], "the idea of God implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation of human liberty, and necessarily ends in the enslavement of mankind, in theory, and practice." He reversed [[Voltaire]]'s aphorism that if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him, writing instead that "if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish him."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/bakunin/godandstate/godandstate_ch1.html |title=God and the State |last=Bakunin |first=Michael |authorlink=Michael Bakunin |year=1916 |website= |publisher=New York: Mother Earth Publishing Association |accessdate=April 9, 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110521195435/http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/bakunin/godandstate/godandstate_ch1.html |archivedate=May 21, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

=== Atheism, religions and spirituality === |

=== Atheism, religions and spirituality === |

||

{{further|Nontheistic religions}} |

{{further|Nontheistic religions}} |

||

| Line 114: | Line 125: | ||

[[Secular Buddhism]] does not advocate belief in gods. Early Buddhism was atheistic as [[Gautama Buddha]]'s path involved no mention of gods. [[God in Buddhism|Later conceptions]] of Buddhism consider Buddha himself a god, suggest adherents can attain godhood, and revere [[Bodhisattva]]s<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Jb0rCQD9NcoC&printsec=frontcover |last=Kedar |first=Nath Tiwari |year=1997 |title=Comparative Religion |publisher=[[Motilal Banarsidass]] |isbn=978-81-208-0293-3 |page=50 |access-date=September 21, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161224020536/https://books.google.com/books?id=Jb0rCQD9NcoC&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=December 24, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

[[Secular Buddhism]] does not advocate belief in gods. Early Buddhism was atheistic as [[Gautama Buddha]]'s path involved no mention of gods. [[God in Buddhism|Later conceptions]] of Buddhism consider Buddha himself a god, suggest adherents can attain godhood, and revere [[Bodhisattva]]s<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Jb0rCQD9NcoC&printsec=frontcover |last=Kedar |first=Nath Tiwari |year=1997 |title=Comparative Religion |publisher=[[Motilal Banarsidass]] |isbn=978-81-208-0293-3 |page=50 |access-date=September 21, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161224020536/https://books.google.com/books?id=Jb0rCQD9NcoC&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=December 24, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

and [[Eternal Buddha]]. |

and [[Eternal Buddha]]. |

||

=== Atheism and negative theology === |

=== Atheism and negative theology === |

||

{{further|Apophatic theology#Apophatic theology and atheism{{!}}Atheism and negative theology}} |

{{further|Apophatic theology#Apophatic theology and atheism{{!}}Atheism and negative theology}} |

||

[[Apophatic theology]] is often assessed as being a version of atheism or agnosticism, since it cannot say truly that God exists.<ref>{{Cite book |editor-last=Kvanvig |editor-first=Jonathan |editor-link=Jonathan Kvanvig |year=2015 |chapter=7. The Ineffable, Inconceivable, and Incomprehensible God. Fundamentality and Apophatic Theology |chapterurl=https://books.google.com/books?id=V4cSDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA158 |last=Jacobs |first=Jonathan D. |title=Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Religion. Volume 6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V4cSDAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-872233-5 |p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=V4cSDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA168&dq=%22Apophatic+theology+is+often+accused+of+being+a+version+of+atheism+or+agnosticism,+since+we+cannot+say+truly+that+God+exists.%22 168] |access-date=April 22, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170423163032/https://books.google.com/books?id=V4cSDAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=April 23, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> "The comparison is crude, however, for conventional atheism treats the existence of God as a predicate that can be denied ("God is nonexistent"), whereas negative theology denies that God has predicates".<ref>{{Cite book |editor-last=Fagenblat |editor-first=Michael |year=2017 |title=Negative Theology as Jewish Modernity |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sGE7DgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |publisher=[[Indiana University Press]] |location=Bloomington, Indiana |isbn=978-0-253-02504-3 |p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=sGE7DgAAQBAJ&pg=PA3&dq=%22The+comparison+is+crude,+however,+for+conventional+atheism+treats+the+existence+of+God+as+a+predicate+that+can+be+denied%22%22God+is+nonexistent%22%22whereas+negative+theology+denies+that+God+has+predicates%22 3] |access-date=April 19, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170416060307/https://books.google.com/books?id=sGE7DgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=April 16, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> "God or the Divine is" without being able to attribute qualities about "what He is" would be the prerequisite of [[positive theology]] in negative theology that distinguishes theism from atheism. "Negative theology is a complement to, not the enemy of, positive theology".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bryson |first=Michael E. |year=2016 |title=The Atheist Milton |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6MnOCwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |publisher=[[Routledge]] |location=[[Abingdon-on-Thames]] |isbn=978-1-317-04095-8 |p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=6MnOCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT114&dq=%22Negative+theology+is+a+complement+to,+not+the+enemy+of,+positive+theology%22 114] |access-date=April 19, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170416132730/https://books.google.com/books?id=6MnOCwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=April 16, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

[[Apophatic theology]] is often assessed as being a version of atheism or agnosticism, since it cannot say truly that God exists.<ref>{{Cite book |editor-last=Kvanvig |editor-first=Jonathan |editor-link=Jonathan Kvanvig |year=2015 |chapter=7. The Ineffable, Inconceivable, and Incomprehensible God. Fundamentality and Apophatic Theology |chapterurl=https://books.google.com/books?id=V4cSDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA158 |last=Jacobs |first=Jonathan D. |title=Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Religion. Volume 6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V4cSDAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-872233-5 |p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=V4cSDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA168&dq=%22Apophatic+theology+is+often+accused+of+being+a+version+of+atheism+or+agnosticism,+since+we+cannot+say+truly+that+God+exists.%22 168] |access-date=April 22, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170423163032/https://books.google.com/books?id=V4cSDAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=April 23, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> "The comparison is crude, however, for conventional atheism treats the existence of God as a predicate that can be denied ("God is nonexistent"), whereas negative theology denies that God has predicates".<ref>{{Cite book |editor-last=Fagenblat |editor-first=Michael |year=2017 |title=Negative Theology as Jewish Modernity |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sGE7DgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |publisher=[[Indiana University Press]] |location=Bloomington, Indiana |isbn=978-0-253-02504-3 |p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=sGE7DgAAQBAJ&pg=PA3&dq=%22The+comparison+is+crude,+however,+for+conventional+atheism+treats+the+existence+of+God+as+a+predicate+that+can+be+denied%22%22God+is+nonexistent%22%22whereas+negative+theology+denies+that+God+has+predicates%22 3] |access-date=April 19, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170416060307/https://books.google.com/books?id=sGE7DgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=April 16, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> "God or the Divine is" without being able to attribute qualities about "what He is" would be the prerequisite of [[positive theology]] in negative theology that distinguishes theism from atheism. "Negative theology is a complement to, not the enemy of, positive theology".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bryson |first=Michael E. |year=2016 |title=The Atheist Milton |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6MnOCwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |publisher=[[Routledge]] |location=[[Abingdon-on-Thames]] |isbn=978-1-317-04095-8 |p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=6MnOCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT114&dq=%22Negative+theology+is+a+complement+to,+not+the+enemy+of,+positive+theology%22 114] |access-date=April 19, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170416132730/https://books.google.com/books?id=6MnOCwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=April 16, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

== Atheistic philosophies == |

== Atheistic philosophies == |

||

{{Further|Atheist existentialism|Secular humanism}} |

{{Further|Atheist existentialism|Secular humanism}} |

||

[[Axiology|Axiological]], or constructive, atheism rejects the existence of gods in favor of a "higher absolute", such as [[Human nature|humanity]]. This form of atheism favors humanity as the absolute source of ethics and values, and permits individuals to resolve moral problems without resorting to God. Marx and Freud used this argument to convey messages of liberation, full-development, and unfettered happiness.<ref name="Zdybicka-p20" /> One of the most common [[criticism of atheism|criticisms of atheism]] has been to the contrary: that denying the existence of a god either leads to [[moral relativism]] and leaves one with no moral or ethical foundation,<ref name="misconceptions">{{cite web |url=http://articles.exchristian.net/2006/12/common-misconceptions-about-atheists.html |title=Common Misconceptions About Atheists and Atheism |last=Gleeson |first=David |date=August 10, 2006 |accessdate=November 21, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131231001241/http://articles.exchristian.net/2006/12/common-misconceptions-about-atheists.html |archive-date=December 31, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> or renders life [[meaning of life (religious)|meaningless]] and miserable.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1979|p=275}}. "Perhaps the most common criticism of atheism is the claim that it leads inevitably to [[moral bankruptcy]]."</ref> [[Blaise Pascal]] argued this view in his ''[[Pensées]]''.<ref>[[Blaise Pascal|Pascal, Blaise]] (1669). ''[[Pensées]]'', II: "The Misery of Man Without God".</ref> |