Phenibut

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Anvifen, Fenibut, Noofen, others[1] |

| Other names | Aminophenylbutyric acid; Fenibut; Fenigam; Phenigam; Phenybut; Phenygam; Phenylgamma; Phenigama; PHG; PhGABA; β-Phenyl-γ-aminobutyric acid; β-Phenyl-GABA[2] |

| Routes of administration | Common: By mouth[3] Uncommon: Rectal[3] |

| Drug class | GABA receptor agonist; Gabapentinoid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Well-absorbed[4] ≥63% (250 mg)[5] |

| Metabolism | Liver (minimal)[4][5] |

| Metabolites | Inactive[4] |

| Onset of action | Oral: 2–4 hours[3] Rectal: 20–30 minutes[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 5.3 hours (250 mg)[5] |

| Duration of action | 15–24 hours (1–3 g)[3] |

| Excretion | Urine: 63% (unchanged)[5] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.012.800 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

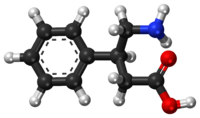

| Formula | C10H13NO2 |

| Molar mass | 179.219 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 253 °C (487 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (March 2022) |

Phenibut, sold under the brand names Anvifen, Fenibut, and Noofen among others,[1] is a central nervous system depressant with anxiolytic effects, and is used to treat anxiety, insomnia, and for a variety of other indications.[5] It is usually taken by mouth as a tablet, but may be given intravenously.[4][5]

Side effects of phenibut include sedation, sleepiness, nausea, irritability, agitation, dizziness, and headache, among others.[4][6] Overdose of phenibut can produce marked central nervous system depression including unconsciousness.[4][6] The medication is structurally related to the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and hence is a GABA analogue.[5] Phenibut is thought to act as a GABAB receptor agonist, similarly to baclofen and γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB).[5] However, at low concentrations, phenibut mildly increases the concentration of dopamine in the brain, providing stimulatory effects in addition to the anxiolysis.[7] Subsequent research has found that it is also a potent blocker of α2δ subunit-containing voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs), similarly to gabapentinoids like gabapentin and pregabalin.[8][9]

Phenibut was developed in the Soviet Union and was introduced for medical use in the 1960s.[5] Today, it is marketed for medical use in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Latvia.[5] The medication is not approved for clinical use in the United States and most of Europe, but it is also sold on the Internet as a supplement and purported nootropic.[3][10] Phenibut has been used recreationally and can produce euphoria as well as addiction, dependence, and withdrawal.[3] It is a controlled substance in Australia, and it has been suggested that its legal status should be reconsidered in Europe as well.[3]

Medical uses

Phenibut is used in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Latvia as a pharmaceutical drug to treat anxiety and to improve sleep (e.g., in the treatment of insomnia).[5][4] It is also used for various other indications, including the treatment of asthenia, depression, alcoholism, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, stuttering, tics, vestibular disorders, Ménière's disease, dizziness, for the prevention of motion sickness, and for the prevention of anxiety before or after surgical procedures or painful diagnostic tests.[4][5]

Available forms

Phenibut is available as a medication in the form of 250 mg or 500 mg tablets for oral administration and as a solution at a concentration of 10 mg/mL for infusion.[4][6][11] In the US, dietary supplements labeled as containing phenibut have been found to contain zero to greater than 1,100 mg of phenibut per serving.[10]

Contraindications

Contraindications of phenibut include:[4][6]

- Intolerance to phenibut

- Pregnancy and breastfeeding

- Children who are younger than two years of age

- Liver insufficiency or failure

- Ulcerative lesions of the gastrointestinal tract

Phenibut should not be combined with alcohol.[6]

Side effects

Phenibut is generally well-tolerated.[5][6] Possible side effects may include sedation, somnolence, nausea, irritability, agitation, anxiety, dizziness, headache, and allergic reactions such as skin rash and itching.[4][6] At high doses, motor incoordination, loss of balance, and hangovers may occur.[3] Due to its central nervous system depressant effects, people taking phenibut should refrain from potentially dangerous activities such as operating heavy machinery.[4][6] With prolonged use of phenibut, particularly at high doses, the liver and blood should be monitored, due to risk of fatty liver disease and eosinophilia.[4][6]

Overdose

In overdose, phenibut can cause severe drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, eosinophilia, lowered blood pressure, renal impairment, and, above 7 grams, fatty liver degeneration.[4][6] There are no specific antidotes for phenibut overdose.[6] Lethargy, somnolence, agitation, delirium, tonic–clonic seizures, reduced consciousness or unconsciousness, and unresponsiveness have been reported in recreational users who have overdosed.[3] Management of phenibut overdose includes activated charcoal, gastric lavage, induction of vomiting, and symptom-based treatment.[4][6] There have been several cases of lethal overdose.[12]

Dependency and Withdrawal

Tolerance to phenibut easily develops with repeated use leading to dependency.[5] Withdrawal symptoms may occur upon discontinuation, and, in recreational users taking high doses, have been reported to include severe rebound anxiety, insomnia, anger, irritability, agitation, visual and auditory hallucinations, and acute psychosis.[3] Baclofen has successfully been used for treatment of phenibut dependence.[13]

Interactions

Phenibut may mutually potentiate and extend the duration of the effects of other central nervous system depressants including anxiolytics, antipsychotics, sedatives, opioids, anticonvulsants, and alcohol.[4][6]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Compound | GABAB | GABAA |

|---|---|---|

| GABA | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| GHB | >100 | >100 |

| GABOB | 1.10 | 1.38 |

| Phenibut | 9.6 | >100 |

| 4-F-phenibut | 1.70 | >100 |

| Baclofen | 0.13 | >100 |

| (R)-Baclofen | 0.13 | >100 |

| (S)-Baclofen | 74.0 | >100 |

| Values are IC50 (μM) in rat brain. | ||

Phenibut acts as a full agonist of the GABAB receptor, similarly to baclofen.[15][16] It has between 30- to 68-fold lower affinity for the GABAB receptor than baclofen, and, in accordance, is used at far higher doses in comparison.[15] (R)-Phenibut has more than 100-fold higher affinity for the GABAB receptor than does (S)-phenibut; hence, (R)-phenibut is the active enantiomer at the GABAB receptor.[17] At very high concentrations, phenibut reportedly also acts as an agonist of the GABAA receptor, which is the receptor responsible for the actions of the benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and alcohol.[18]

| Compound | α2δ | GABAB |

|---|---|---|

| Phenibut | ND | 177 |

| (R)-Phenibut | 23 | 92 |

| (S)-Phenibut | 39 | >1,000 |

| Baclofen | 156 | 6 |

| Gabapentin | 0.05 | >1,000 |

| Values are Ki (μM) in rat brain. | ||

Phenibut also binds to and blocks α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs, similarly to gabapentin and pregabalin, and hence is a gabapentinoid.[8][19] Both (R)-phenibut and (S)-phenibut display this action with similar affinity (Ki = 23 and 39 μM, respectively).[8] Moreover, (R)-phenibut possesses 4-fold greater affinity for this site than for the GABAB receptor (Ki = 92 μM), while (S)-phenibut does not bind significantly to the GABAB receptor (Ki > 1 mM).[8] As such, based on the results of this study, phenibut would appear to have much greater potency in its interactions with α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs than with the GABAB receptor (between 5- to 10-fold).[8] For this reason, the actions of phenibut as a α2δ subunit-containing voltage-gated calcium channel blocker or gabapentinoid may be its true primary mechanism of action, and this may explain the differences between phenibut and its close relative baclofen (which, in contrast, has essentially insignificant activity as a gabapentinoid; Ki = 6 μM for the GABAB receptor and Ki = 156 μM for α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs, or a 26-fold difference in affinity).[8][9]

(R)-Phenibut and (S)-phenibut have been assayed at 85 binding sites at a concentration of 100 μM with no activity (less than 20% inhibition of binding) observed except at the α2δ VDCC subunit and the GABAB receptor.[20] In this study, (R)-phenibut and (S)-phenibut showed IC50 values for inhibition of gabapentin binding of 87.1 μM and 91.0 μM (Ki = 60 μM), respectively.[20] The IC50 for gabapentin under the same conditions was 0.09 μM.[20] The researchers also assessed phenibut at the GABAB receptor and found a Ki value of 57 μM for (R)-phenibut, which would be about twice that concentration (~114 μM) with racemic phenibut.[20]

Pharmacokinetics

Little information thus far has been published on the clinical pharmacokinetics of phenibut.[5] The drug is reported to be well-absorbed.[4] It distributes widely throughout the body and across the blood–brain barrier.[4] Approximately 0.1% of an administered dose of phenibut reportedly penetrates into the brain, with this said to occur to a much greater extent in young people and the elderly.[4] Following a single 250 mg dose in healthy volunteers, its elimination half-life was approximately 5.3 hours and the drug was largely (63%) excreted in the urine unchanged.[5] In animals, the absolute bioavailability of phenibut was 64% after oral and intravenous administration, it appeared to undergo minimal or no metabolism in multiple species, and it crossed the blood–brain barrier to a significantly greater extent than GABA.[5] The metabolites of phenibut are reported to be inactive.[4]

Some limited information has been described on the pharmacokinetics of phenibut in recreational users taking much higher doses (e.g., 1–3 grams) than typical clinical doses.[3][21] In these individuals, the onset of action of phenibut has been reported to be 2 to 4 hours orally and 20 to 30 minutes rectally, the peak effects are described as occurring 4 to 6 hours following oral ingestion, and the total duration for the oral route has been reported to be 15 to 24 hours (or about 3 to 5 terminal half-lives).[3]

Chemistry

Phenibut is a synthetic aromatic amino acid. It is a chiral molecule and thus has two potential configurations, as (R)- and (S)-enantiomers.[16]

Structure and analogues

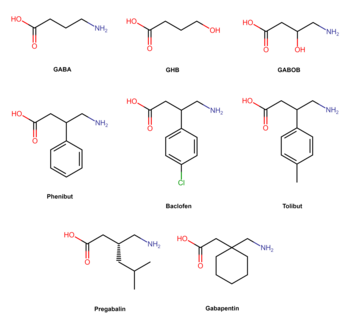

Phenibut is a derivative of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.[5] Hence, it is a GABA analogue.[5] Phenibut is specifically the analogue of GABA with a phenyl ring substituted in at the β-position.[5] As such, its chemical name is β-phenyl-γ-aminobutyric acid, which can be abbreviated as β-phenyl-GABA.[5] The presence of the phenyl ring allows phenibut to cross the blood–brain barrier significantly, unlike the case of GABA.[5] Phenibut also contains the trace amine β-phenethylamine in its structure.[5]

Phenibut is closely related to a variety of other GABA analogues including baclofen (β-(4-chlorophenyl)-GABA), 4-fluorophenibut (β-(4-fluorophenyl)-GABA), tolibut (β-(4-methylphenyl)-GABA), pregabalin ((S)-β-isobutyl-GABA), gabapentin (1-(aminomethyl)cyclohexane acetic acid), and GABOB (β-hydroxy-GABA).[5][8] It has almost the same chemical structure as baclofen, differing from it only in having a hydrogen atom instead of a chlorine atom at the para position of the phenyl ring.[5] Phenibut is also close in structure to pregabalin, which has an isobutyl group at the β position instead of phenibut's phenyl ring.[8]

A glutamate-derivative analogue of phenibut is glufimet (dimethyl 3-phenylglutamate hydrochloride).[22]

Synthesis

A chemical synthesis of phenibut has been published.[11]

History

Phenibut was synthesized at the A. I. Herzen Leningrad Pedagogical Institute (USSR) by Professor Vsevolod Perekalin's team and tested at the Institute of Experimental Medicine, USSR Academy of Medical Sciences.[5] It was introduced into clinical use in Russia in the 1960s.[5]

Society and culture

Generic names

The generic name of phenibut is fenibut, phenibut, or phenybut (Russian: фенибут).[2] It is also sometimes referred to as aminophenylbutyric acid (Russian: аминофенилмасляная кислота).[1] The word phenibut is a contraction of the chemical name of the drug, β-phenyl-γ-aminobutyric acid.[5] In early publications, phenibut was referred to as fenigam and phenigama (and spelling variants thereof; Russian: фенигам and фенигама).[5][23] The drug has not been assigned an INN.[2][4]

Brand names

Phenibut is marketed in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Latvia under the brand names Anvifen, Fenibut, Bifren and Noofen (Russian: Анвифен, Фенибут, Бифрен and Ноофен, respectively).[1]

Availability

Phenibut is approved in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Latvia for medical use.[3] It is not approved or available as a medication in other countries in the European Union, the United States, or Australia.[3] In countries where phenibut is not a licensed pharmaceutical drug, it is sold online without a prescription as a "nutritional supplement".[3][10] It is often used as a form of self-medication for social anxiety.[3]

Recreational use

Phenibut is used recreationally due to its ability to produce euphoria, anxiolysis, and increased sociability.[3] As well as remaining undetected in routine urinalysis. Because of its delayed onset of effects, first-time users often mistakenly take an additional dose of phenibut in the belief that the initial dose did not work.[3] Recreational users usually take the drug orally; there are a few case reports of rectal administration and one report of insufflation, which was described as "very painful" and causing swollen nostrils.[3]

Legal status

As of 2021, phenibut is a controlled substance in Australia,[3] France,[24] Hungary,[25] Italy,[26] and Lithuania.[27][28] In 2015, it was suggested that the legal status of phenibut in Europe should be reconsidered due to its recreational potential.[3] In February 2018, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration declared it a prohibited (schedule 9) substance, citing health concerns due to withdrawal and overdose.[29][30]

As of 14 November 2018, Hungary added phenibut and 10 other items to its New Psychoactive Substances ban list.[31]

As of 26 August 2020, Italy added phenibut to its New Psychoactive Substances ban list.[26]

As of 18 September 2020, France added phenibut to the controlled psychoactive substances list, prohibiting production, sale, storage and use.[32]

In the United States, Phenibut is not a Controlled Substance. However, Dietary supplements that contain Phenibut are unlawful to introduce into interstate commerce, because Phenibut is considered a "New Drug" and any food, supplement, cosmetic, or drug that contains Phenibut is therefore adulterated. Alabama scheduled Phenibut and Tianeptine in 2021 first by action of the Alabama Department of Public Health and then followed by the state legislature.[33]

References

- ^ a b c d Drobizhev MY, Fedotova AV, Kikta SV, Antohin EY (2016). "Феномен аминофенилмасляной кислоты" [Phenomenon of aminophenylbutyric acid]. Russian Medical Journal (in Russian). 2017 (24): 1657–1663. ISSN 1382-4368.

- ^ a b c Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Owen DR, Wood DM, Archer JR, Dargan PI (September 2016). "Phenibut (4-amino-3-phenyl-butyric acid): Availability, prevalence of use, desired effects and acute toxicity". Drug and Alcohol Review. 35 (5): 591–6. doi:10.1111/dar.12356. hdl:10044/1/30073. PMID 26693960.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Ozon Pharm, Fenibut (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2017, retrieved 15 September 2017

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Lapin I (2001). "Phenibut (beta-phenyl-GABA): a tranquilizer and nootropic drug". CNS Drug Reviews. 7 (4): 471–81. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00211.x. PMC 6494145. PMID 11830761.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Регистр лекарственных средств России ([Russian Medicines Register]). "Фенибут (Phenybutum)" [Fenibut (Phenybutum)] (in Russian). Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Lapin I (7 June 2006). "Phenibut (beta-phenyl-GABA): a tranquilizer and nootropic drug". CNS Drug Reviews. 7 (4): 471–81. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00211.x. PMC 6494145. PMID 11830761.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zvejniece L, Vavers E, Svalbe B, Veinberg G, Rizhanova K, Liepins V, et al. (October 2015). "R-phenibut binds to the α2-δ subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels and exerts gabapentin-like anti-nociceptive effects". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 137: 23–9. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2015.07.014. PMID 26234470. S2CID 42606053.

- ^ a b c Froestl W (2010). "Chemistry and pharmacology of GABAB receptor ligands". GABABReceptor Pharmacology - A Tribute to Norman Bowery. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 58. pp. 19–62. doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(10)58002-5. ISBN 9780123786470. PMID 20655477.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Cohen, Pieter A.; Ellison, Ross R.; Travis, John C.; Gaufberg, Slava V.; Gerona, Roy (22 September 2021). "Quantity of phenibut in dietary supplements before and after FDA warnings". Clinical Toxicology: 1–3. doi:10.1080/15563650.2021.1973020. PMID 34550038. S2CID 237594860.

- ^ a b Sivchik VV, Grygoryan HO, Survilo VL, Trukhachova TV (2012), Синтез γ-амино-β-фенилмасляной кислоты (фенибута) [Synthesis of β-phenyl-γ-aminobutyric acid (phenibut)] (PDF) (in Russian)

- ^ Graves JM, Dilley J, Kubsad S, Liebelt E (September 2020). "Notes from the Field: Phenibut Exposures Reported to Poison Centers - United States, 2009–2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (35): 1227–1228. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a5. PMC 7470459. PMID 32881852.

- ^ Samokhvalov AV, Paton-Gay CL, Balchand K, Rehm J (February 2013). "Phenibut dependence". BMJ Case Reports. 2013: bcr2012008381. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-008381. PMC 3604470. PMID 23391959.

- ^ Bowery NG, Hill DR, Hudson AL (January 1983). "Characteristics of GABAB receptor binding sites on rat whole brain synaptic membranes". British Journal of Pharmacology. 78 (1): 191–206. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1983.tb09380.x. PMC 2044790. PMID 6297646.

- ^ a b GABAb Receptor Pharmacology: A Tribute to Norman Bowery: A Tribute to Norman Bowery. Academic Press. 21 September 2010. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-0-12-378648-7.

- ^ a b Dambrova M, Zvejniece L, Liepinsh E, Cirule H, Zharkova O, Veinberg G, Kalvinsh I (March 2008). "Comparative pharmacological activity of optical isomers of phenibut". European Journal of Pharmacology. 583 (1): 128–134. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.015. PMID 18275958.

- ^ Allan RD, Bates MC, Drew CA, Duke RK, Hambley TW, Johnston GA, et al. (1990). "A new synthesis resolution and in vitro activities of (R)- and (S)-β-Phenyl-Gaba". Tetrahedron. 46 (7): 2511–2524. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)82032-9. ISSN 0040-4020.

- ^ Zyablitseva EA, Kositsyn NS, Shul'gina GI (May 2009). "The effects of agonists of ionotropic GABA(A) and metabotropic GABA(B) receptors on learning". The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 12 (1): 12–20. doi:10.1017/S1138741600001438. PMID 19476215. S2CID 5192629.

- ^ Vavers E, Zvejniece L, Svalbe B, Volska K, Makarova E, Liepinsh E, et al. (November 2016). "The neuroprotective effects of R-phenibut after focal cerebral ischemia". Pharmacological Research. 113 (Pt B): 796–801. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2015.11.013. PMID 26621244.

- ^ a b c d Belozertseva I, Nagel J, Valastro B, Franke L, Danysz W (June 2016). "Optical isomers of phenibut inhibit [H(3)]-Gabapentin binding in vitro and show activity in animal models of chronic pain". Pharmacological Reports. 68 (3): 550–4. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2015.12.004. PMID 26894962.

- ^ Schifano F, Orsolini L, Duccio Papanti G, Corkery JM (February 2015). "Novel psychoactive substances of interest for psychiatry". World Psychiatry. 14 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1002/wps.20174. PMC 4329884. PMID 25655145.

- ^ Perfilova VN, Popova TA, Prokofiev II, Mokrousov IS, Ostrovskii OV, Tyurenkov IN (June 2017). "Effect of Phenibut and Glufimet, a Novel Glutamic Acid Derivative, on Respiration of Heart and Brain Mitochondria from Animals Exposed to Stress against the Background of Inducible NO-Synthase Blockade". Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine. 163 (2): 226–229. doi:10.1007/s10517-017-3772-4. PMID 28726197. S2CID 4907409.

- ^ Khaunina RA, Lapin IP (1976). "Fenibut, a new tranquilizer". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 10 (12): 1703–1705. doi:10.1007/BF00760021. ISSN 0091-150X. S2CID 29071385.

- ^ Par [1] La liste des substances psychotropes

- ^ "39/2018. (XI. 8.) EMMI rendelet Az új pszichoaktív anyaggá minősített anyagokról vagy vegyületcsoportokról szóló 55/2014. (XII. 30.) EMMI rendelet módosításáról" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Gazzetta Ufficiale 11/08/20". Lorenzo Arbolino. 11 August 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ "RINKOS RIBOJIMO PRIEMONĖS FENIBUTUI!". ntakd.lrv.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "V-1431 Dėl Lietuvos Respublikos sveikatos apsaugos ministro 2000 m. sausio 6 d. įsakymo Nr. 5 "Dėl Narko..." e-seimas.lrs.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 27 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Administration, Australian Government Department of Health. Therapeutic Goods (31 October 2017). "3.3 Phenibut". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Mass school overdose investigation focuses on banned Russian drug". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "EMMI Decree substances or groups of compounds classified as new psychoactive substances". Wolters Kluwer. 1 January 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Le phénibut interdit en France | Le Généraliste

- ^ "HB2, Holmes, Tianeptine and Phenibut added to Schdule I Conrolled Substances". Alabama Pharmacy Association.