Gavin Newsom

Gavin Newsom | |

|---|---|

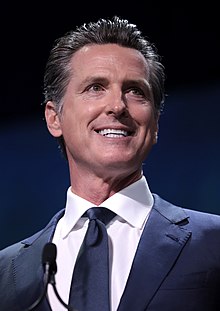

Newsom in 2019 | |

| 40th Governor of California | |

| Assumed office January 7, 2019 | |

| Lieutenant | Eleni Kounalakis |

| Preceded by | Jerry Brown |

| 49th Lieutenant Governor of California | |

| In office January 10, 2011 – January 7, 2019 | |

| Governor | Jerry Brown |

| Preceded by | Abel Maldonado |

| Succeeded by | Eleni Kounalakis |

| 42nd Mayor of San Francisco | |

| In office January 8, 2004 – January 10, 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Willie Brown |

| Succeeded by | Ed Lee |

| Member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from District 2 | |

| In office January 8, 1997 – January 8, 2004 | |

| Preceded by | Kevin Shelley |

| Succeeded by | Michela Alioto-Pier |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gavin Christopher Newsom October 10, 1967 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 4 |

| Parents |

|

| Residence(s) | Fair Oaks, California, U.S. |

| Education | Santa Clara University (BS) |

| Signature | |

| Website | Campaign website Government website |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Mayor of San Francisco

Lieutenant Governor of California

Governor of California

Published works

|

||

Gavin Christopher Newsom (born October 10, 1967) is an American politician and businessman serving as the 40th governor of California since January 2019. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 49th lieutenant governor of California from 2011 to 2019 and as the 42nd mayor of San Francisco from 2004 to 2011.

Newsom attended Redwood High School and graduated from Santa Clara University. After graduation, he founded the PlumpJack wine store with family friend Gordon Getty as an investor. The PlumpJack Group grew to manage 23 businesses, including wineries, restaurants, and hotels. Newsom began his political career in 1996, when San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown appointed him to serve on the city's Parking and Traffic Commission. Brown appointed Newsom to fill a vacancy on the Board of Supervisors the following year, and Newsom was later elected to the board in 1998, 2000, and 2002.[1]

In 2003, at the age of 36, Newsom was elected the 42nd mayor of San Francisco, becoming the city's youngest mayor in a century.[2] Newsom was re-elected in 2007 with 72% of the vote.[3][4]

Newsom was elected lieutenant governor of California in 2010 and was re-elected in 2014. He was elected governor in the 2018 election. Newsom faced criticism for his personal behavior and leadership during and after COVID-19 pandemic, which was followed by an unsuccessful attempt to recall him from office, in what would be the fourth gubernatorial recall election in United States history.[5][6] Newsom prevailed in the 2021 recall election, becoming the second incumbent U.S. governor to survive a recall election.[7]

Newsom hosted The Gavin Newsom Show on Current TV from 2012 to 2013 and wrote the 2013 book Citizenville, about using digital tools for democratic change.[8] Political science analysis has suggested he is moderate, relative to almost all Democratic legislators in California.[9]

Early life

Newsom was born in San Francisco, to Tessa Thomas (née Menzies) and William Alfred Newsom III, a state appeals court judge and attorney for Getty Oil. He is a fourth-generation San Franciscan. One of Newsom's maternal great-grandfathers, Scotsman Thomas Addis, was a pioneer scientist in the field of nephrology and a professor of medicine at Stanford University. Newsom is the second cousin, twice removed, of musician Joanna Newsom.[10]

His father was an advocate for otters and the family had one as a pet.[11] Newsom's parents divorced in 1972 when Gavin was five years old.[citation needed]

Newsom later said he had not had an easy childhood, partly due to dyslexia.[12] He attended kindergarten and first grade at Ecole Notre Dame Des Victoires, a French-American bilingual school in San Francisco, but eventually transferred out, due to the severe dyslexia that still affects him. It has challenged his abilities to write, spell, read, and work with numbers.[12] Throughout his schooling, Newsom had to rely on a combination of audiobooks, digests, and informal verbal instruction. To this day, he prefers to interpret documents and reports through audio.[13]

He attended third through fifth grades at Notre Dame des Victoires, where he was placed in remedial reading classes. In high school, Newsom played basketball and baseball and graduated from Redwood High School in 1985. Newsom was a shooting guard in basketball and an outfielder in baseball. His skills placed him on the cover of the Marin Independent Journal.[14]

Tessa Newsom worked three jobs to support Gavin and his sister Hilary Newsom Callan, the PlumpJack Group president, named after the opera Plump Jack composed by family friend Gordon Getty. In an interview with The San Francisco Chronicle, his sister recalled the Christmas holidays when their mother told them they would not receive any gifts.[14] Tessa opened their home to foster children, instilling in Newsom the importance of public service.[14][15] His father's finances were strapped in part because of his tendency to give away his earnings.[15] Newsom worked several jobs in high school to help support his family.[3]

Newsom attended Santa Clara University on a partial baseball scholarship, where he graduated in 1989 with a Bachelor of Science in political science. Newsom was a left-handed pitcher for Santa Clara, but he threw his arm out after two years and has not thrown a baseball since.[16] He lived in the Alameda Apartments, which he later compared to living in a hotel. He later reflected on his education fondly, crediting the Jesuit approach of Santa Clara with helping him become an independent thinker who questions orthodoxy. While in school, Newsom spent a semester studying abroad in Rome.[17]

Newsom's aunt was married to Ron Pelosi, the brother-in-law of Speaker of the United States House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi.[12]

Business career

Newsom and his investors created the company PlumpJack Associates L.P. on May 14, 1991. The group started the PlumpJack Winery in 1992 with the financial help[18] of his family friend Gordon Getty. PlumpJack was the name of an opera written by Getty, who invested in 10 of Newsom's 11 businesses.[12] Getty told the San Francisco Chronicle that he treated Newsom like a son and invested in his first business venture because of that relationship. According to Getty, later business investments were because of "the success of the first".[12]

One of Newsom's early interactions with government occurred when Newsom resisted the San Francisco Health Department requirement to install a sink at his PlumpJack wine store. The Health Department argued that wine was a food and required the store to install a $27,000 sink in the carpeted wine shop on the grounds that the shop needed the sink for a mop. When Newsom was later appointed supervisor, he told the San Francisco Examiner: "That's the kind of bureaucratic malaise I'm going to be working through."[16]

The business grew to an enterprise with more than 700 employees.[14] The PlumpJack Cafe Partners L.P. opened the PlumpJack Café, also on Fillmore Street, in 1993. Between 1993 and 2000, Newsom and his investors opened several other businesses that included the PlumpJack Squaw Valley Inn with a PlumpJack Café (1994), a winery in Napa Valley (1995), the Balboa Café Bar and Grill (1995), the PlumpJack Development Fund L.P. (1996), the MatrixFillmore Bar (1998), PlumpJack Wines shop Noe Valley branch (1999), PlumpJackSport retail clothing (2000), and a second Balboa Café at Squaw Valley (2000).[12] Newsom's investments included five restaurants and two retail clothing stores.[14] Newsom's annual income was greater than $429,000 from 1996 to 2001.[12] In 2002, his business holdings were valued at more than $6.9 million.[14] Newsom gave a monthly $50 gift certificate to PlumpJack employees whose business ideas failed, because in his view, "There can be no success without failure."[16]

Newsom sold his share of his San Francisco businesses when he became mayor in 2004. He maintained his ownership in the PlumpJack companies outside San Francisco, including the PlumpJack Winery in Oakville, California, new PlumpJack-owned Cade Winery in Angwin, California, and the PlumpJack Squaw Valley Inn. He is the president in absentia of Airelle Wines Inc., which is connected to the PlumpJack Winery in Napa County. Newsom earned between $141,000 and $251,000 in 2007 from his business interests.[19] In February 2006, he paid $2,350,000 for his residence in the Russian Hill neighborhood, which he put on the market in April 2009 for $3,000,000.[20]

Early political career

Newsom's first political experience came when he volunteered for Willie Brown's successful campaign for mayor in 1995. Newsom hosted a private fundraiser at his PlumpJack Café.[12] Brown appointed Newsom to a vacant seat on the Parking and Traffic Commission in 1996, and he was later elected president of the commission. Brown appointed him to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors seat vacated by Kevin Shelley in 1997. At the time, he was the youngest member of San Francisco's board of supervisors.[21][22][23]

Newsom was sworn in by his father and pledged to bring his business experience to the board.[22] Brown called Newsom "part of the future generation of leaders of this great city".[22] Newsom described himself as a "social liberal and a fiscal watchdog".[22][23] He was subsequently elected to a full four-year term to the board in 1998. San Francisco voters chose to abandon at-large elections to the board for the previous district system in 1999. Newsom was re-elected in 2000 and 2002 to represent the second district, which includes Pacific Heights, the Marina, Cow Hollow, Sea Cliff and Laurel Heights, which had the highest income level and the highest Republican registration in San Francisco.[1] Newsom paid $500 to the San Francisco Republican Party to appear on the party's endorsement slate in 2000. He faced no opposition in his 2002 re-election bid.

As a San Francisco Supervisor, Newsom gained public attention for his role in advocating reform of the city's municipal railway (Muni).[24] He was one of two supervisors endorsed by Rescue Muni, a transit riders group, in his 1998 re-election. He sponsored Proposition B to require Muni and other city departments to develop detailed customer service plans.[12][25] The measure passed with 56.6% of the vote.[26] Newsom sponsored a ballot measure from Rescue Muni; a version of the measure was approved by voters in November 1999.[24]

He also supported allowing restaurants to serve alcohol at their outdoor tables, banning tobacco advertisements visible from the streets, stiffer penalties for landlords who run afoul of rent-control laws, and a resolution, which was defeated, to commend Colin Powell for raising money for youth programs.[24] Newsom's support for business interests at times strained his relationship with labor leaders.[24]

During Newsom's time as supervisor, he supported housing projects through public-private partnerships to increase homeownership and affordable housing in San Francisco.[27] He supported HOPE, a failed local ballot measure that would have allowed an increased condo-conversion rate if a certain percentage of tenants within a building were buying their units. As a candidate for mayor, he supported building 10,000 new housing units to create 15,000 new construction jobs.[27] As governor, he also signed into law SB-7, which expedites the environmental review process for new multifamily developments worth at least $15,000,000. To participate, developers must apply directly through the governor's office.[28]

Newsom's signature achievement as a supervisor was a voter initiative called Care Not Cash (Measure N), which offered care, supportive housing, drug treatment, and help from behavioral health specialists for the homeless in lieu of direct cash aid from the state's general assistance program.[27] Many homeless rights advocates protested against the initiative. "Progressives and Democrats, nuns and priests, homeless advocates and homeless people were furious," according to Newsom.[29] The successfully passed ballot measure raised his political profile and provided the volunteers, donors, and campaign staff that helped make him a leading contender for the mayorship in 2003.[12][30][31] In a city audit conducted four years after the inception of program and released in 2008, the program was evaluated as largely successful.[32]

Mayor of San Francisco (2004–2011)

Elections

2003

Newsom placed first in the November 4, 2003, general election in a nine-person field. He received 41.9% of the vote to Green Party candidate Matt Gonzalez's 19.6% in the first round of balloting, but he faced a closer race in the December 9 run-off when many of the city's progressive groups coalesced around Gonzalez.[30] The race was partisan with attacks against Gonzalez for his support of Ralph Nader in the 2000 presidential election, and attacks against Newsom for contributing $500 to a Republican slate mailer in 2000 that endorsed issues Newsom supported.[33][34] Democratic leadership felt that they needed to reinforce San Francisco as a Democratic stronghold after losing the 2000 presidential election and the 2003 gubernatorial recall election to Arnold Schwarzenegger.[34] National figures from the Democratic Party, including Bill Clinton, Al Gore, and Jesse Jackson, campaigned on Newsom's behalf.[34][35] Five supervisors endorsed Gonzalez, while Willie Brown endorsed Newsom.[30][31]

Newsom won the run-off race, capturing 53% of the vote to Gonzalez's 47% and winning by 11,000 votes.[30] He ran as a business-friendly centrist Democrat and a moderate in San Francisco politics; some of his opponents called him conservative.[30][34] Newsom claimed he was a centrist in the Dianne Feinstein mold.[27][36] He ran on the slogan "great cities, great ideas", and presented over 21 policy papers.[31] He pledged to continue working on San Francisco's homelessness issue.[30]

Newsom was sworn in as mayor on January 3, 2004. He called for unity among the city's political factions, and promised to address the issues of public schools, potholes and affordable housing.[37] Newsom said he was "a different kind of leader" who "isn't afraid to solve even the toughest problems".[38]

2007

San Francisco's progressive community tried to field a candidate to run a strong campaign against Newsom. Supervisors Ross Mirkarimi and Chris Daly considered running against Newsom, but both declined. Matt Gonzalez also decided not to rechallenge Newsom.[39]

When the August 10, 2007, filing deadline passed, San Francisco's discussion shifted to talk about Newsom's second term. He was challenged in the election by 13 candidates that included George Davis, a nudist activist, and Michael Powers, owner of the Power Exchange sex club.[40] Conservative former supervisor Tony Hall withdrew by early September due to lack of support.[41]

The San Francisco Chronicle declared in August 2007 that Newsom faced no "serious threat to his re-election bid", having raised $1.6 million for his re-election campaign by early August.[42] He won re-election on November 6, 2007, with over 72% of the vote.[4] Upon taking office for a second term, Newsom promised to focus on the environment, homelessness, health care, education, housing, and rebuilding San Francisco General Hospital.[43][44]

Mayoralty

As mayor, Newsom focused on development projects in Hunters Point and Treasure Island.

He gained national attention in 2004 when he directed the San Francisco city–county clerk to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, violating the state law passed in 2000.[45] Implementation of Care Not Cash, the initiative he had sponsored as a supervisor, began on July 1, 2004. As part of the initiative, 5,000 more homeless people were given permanent shelter in the city. About 2,000 people had been placed into permanent housing with support by 2007. Other programs initiated by Newsom to end chronic homelessness included the San Francisco Homeless Outreach Team (SF HOT) and Project Homeless Connect (PHC) that placed 2,000 homeless into permanent housing and provided 5,000 additional affordable rental units in the city.[46]

During a strike by hotel workers against a dozen San Francisco hotels, Newsom joined UNITE HERE union members on a picket line in front of the Westin St. Francis Hotel on October 27, 2004. He vowed that the city would boycott the hotels by not sponsoring city events at them until they agreed to a contract with workers. The contract dispute was settled in September 2006.[47]

In 2005, Newsom pushed for a state law to allow communities in California to create policy restricting certain breeds of dogs.[48]

He signed the law establishing Healthy San Francisco in 2007 to provide city residents with universal health care, the first city in the nation to do so.[46]

Newsom came under attack from the San Francisco Democratic Party in 2009 for his failure to implement the City of San Francisco's sanctuary city rule, under which the city was to not assist U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.[49]

The same year, Newsom received the Leadership for Healthy Communities Award, along with Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York City and three other public officials, for his commitment to making healthful food and physical activity options more accessible to children and families.[50] He hosted the Urban-Rural Roundtable in 2008 to explore ways to promote regional food development and increased access to healthy, affordable food.[51] Newsom secured $8 million in federal and local funds for the Better Streets program,[52] which ensures that public health perspectives are fully integrated into urban planning processes. He signed a menu-labeling bill into law, requiring that chain restaurants print nutrition information on their menus.[53]

Newsom was named "America's Most Social Mayor" in 2010 by Same point, based on analysis of the social media profiles of mayors from the 100 largest cities in the United States.[54]

Same-sex marriage

Newsom gained national attention in 2004 when he directed the San Francisco city–county clerk to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, violating state law.[45] In August 2004, the Supreme Court of California annulled the marriages that Newsom had authorized, as they conflicted with state law. Still, Newsom's unexpected move brought national attention to the issue of same-sex marriage, solidifying political support for Newsom in San Francisco and in the LGBTQ+ community.[3][15][55]

During the 2008 election, Newsom opposed Proposition 8, the ballot initiative to reverse the California Supreme Court ruling that there was a constitutional right to same-sex marriage.[56] Proposition 8 supporters released a commercial featuring footage of Newsom saying the following in a speech regarding same-sex marriage: "This door's wide open now. It's going to happen, whether you like it or not."[57] Some observers noted that polls shifted in favor of Proposition 8 following the release of the commercial; this, in turn, led to speculation that Newsom had inadvertently played a role in the passage of the amendment.[57][58][59][60]

Lieutenant Governor of California (2011–2019)

Elections

2010

In April 2009, Newsom announced his intention to run for Governor of California in the 2010 election. He received the endorsement of former President Bill Clinton in September 2009. During the campaign, Newsom remarked that, if elected, he would like to be known as "The Gavinator" (a reference to the nickname of incumbent Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, "The Governator"). Throughout the campaign, however, Newsom suffered low poll numbers, trailing Democratic frontrunner Jerry Brown by more than 20 points in most polls.[61][62][63] Newsom dropped out of the gubernatorial race in October 2009.[64][65][66]

Newsom filed initial paperwork to run for lieutenant governor in February 2010,[67] and officially announced his candidacy in March.[68] He received the Democratic nomination in June[69] and won the election on November 2, 2010.[70] Newsom was sworn in as lieutenant governor on January 10, 2011, and served under Governor Jerry Brown. The one-week delay was to ensure that a successor as mayor of San Francisco was chosen before he left office. Edwin M. Lee, the city administrator, took office the day after Newsom was sworn in as lieutenant governor. He debuted on Current TV as the host of The Gavin Newsom Show in May 2012. That same month, Newsom drew criticism for negative comments about Sacramento, referring to the state capital as "dull" and commenting that he was only there once a week, saying "there's no reason" to be there otherwise.[71]

2014

Newsom was re-elected as Lieutenant Governor of California on November 4, 2014, defeating Republican Ron Nehring with 57.2% of the vote. His second term began on January 5, 2015.[72]

Capital punishment

Newsom supported a failed measure in 2012 that sought to end capital punishment in California. He claimed the initiative would save California millions of dollars, citing statistics that California had spent $5 billion since 1978 to execute just 13 people.[73]

Newsom also supported the failed Proposition 62 in 2016, which also would have repealed the death penalty in California.[74] He argued that Prop. 62 would get rid of a system "that is administered with troubling racial disparities." He also stated that the death penalty was fundamentally immoral and did not deter crime.[73]

Criminal justice and cannabis legalization

In 2014, Newsom was the only statewide politician to endorse California Proposition 47, a piece of legislation that recategorized certain non-violent offenses like drug and property crimes as misdemeanors as opposed to felonies. Voters passed the measure in the state of California on November 4, 2014.[74]

In July 2015, Newsom released the Blue Ribbon Commission on Marijuana Policy's final report, which he had convened with the American Civil Liberties Union of California in 2013. The report's recommendations to regulate marijuana were intended to inform a legalization measure on the November 2016 ballot.[75] Newsom supported the resulting measure, Proposition 64, which legalized cannabis use and cultivation for California state residents who are 21 or older.[76]

In response to pro-enforcement statements made by White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer, Newsom sent a letter on February 24, 2017, to Attorney General Jeff Sessions and President Donald Trump, urging them not to increase federal enforcement against recreational cannabis firms opening in California.[76] He wrote, "The government must not strip the legal and publicly supported industry of its business and hand it back to drug cartels and criminals ... Dealers don't card kids. I urge you and your administration to work in partnership with California and the other eight states that have legalized recreational marijuana for adult use in a way that will let us enforce our state laws that protect the public and our children while targeting the bad actors." Newsom responded to comments by Spicer, which compared cannabis to opioids saying, "Unlike marijuana, opioids represent an addictive and harmful substance, and I would welcome your administration's focused efforts on tackling this particular public health crisis."[76]

Education

Newsom joined Long Beach City College Superintendent Eloy Oakley in a November 2015 op-ed calling for the creation of the California College Promise, which would create partnerships between public schools, public universities, and employers and offer a free community college education.[77] Throughout 2016, he joined Oakland mayor Libby Schaaf at the launch of the Oakland Promise and Second Lady Jill Biden and Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti at the launch of the LA Promise.[78][79] In June 2016, Newsom helped secure $15 million in the state budget to support the creation of promise programs throughout the state.[80]

In December 2015, Newsom called on the University of California to reclassify computer science courses as a core academic class to incentivize more high schools to offer computer science curriculum.[81][82] He sponsored successful legislation signed by Governor Brown in September 2016, that began the planning process for expanding computer science education to all state students, beginning as early as kindergarten.[83]

In 2016, Newsom passed a series of reforms at the University of California to provide student-athletes with additional academic and injury-related support, and to ensure that contracts for athletic directors and coaches emphasized academic progress. This came in response to several athletics programs, including the University of California – Berkeley's football team, which garnered the lowest graduation rates in the country.[84][85]

Technology in government

Newsom released his first book, Citizenville: How to Take the Town Square Digital and Reinvent Government, on February 7, 2013.[86][87] The book discusses the Gov 2.0 movement that is taking place across the United States. Following its release, Newsom began to work with the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society at the University of California, Berkeley, on the California Report Card (CRC).[88] The CRC is a mobile-optimized platform that allows state residents to "grade" their state on six timely issues. The CRC exemplifies ideas presented in Newsom's Citizenville, encouraging direct public involvement in government affairs via technology.[89]

In 2015, Newsom partnered with the Institute for Advanced Technology and Public Policy at California Polytechnic State University to launch Digital Democracy, an online tool that uses facial and voice recognition to enable users to navigate California legislative proceedings.[90]

Governor of California (2019–present)

Elections

2018

On February 11, 2015, Newsom announced that he was opening a campaign account for governor in the 2018 elections, allowing him to raise funds for a campaign to succeed Jerry Brown as Governor of California.[91] On June 5, 2018, he finished in the top two of the nonpartisan blanket primary, and defeated Republican John H. Cox by a landslide in the gubernatorial election on November 6.[92]

Newsom was sworn in on January 7, 2019.

2021 recall

Several recall attempts were launched against Newsom early in his tenure, though they failed to gain much traction. On February 21, 2020, a recall petition was introduced by Orrin Heatlie, a deputy sheriff in Yolo County. The petition mentioned Newsom's sanctuary state policy and said laws he endorsed favored "foreign nationals, in our country illegally"; said that California had high homelessness, high taxes, and low quality of life; and described other grievances.[93] It was approved for circulation on June 10, 2020, by the California secretary of state.[94]

Forcing the gubernatorial recall election required a total of 1,495,709 verified signatures.[93] By August 2020, 55,000 signatures were submitted and then verified by the secretary of state, and a total of 890 new valid signatures were submitted by October 2020.[95] The petition was initially given a signature deadline of November 17, 2020, but it was extended to March 17, 2021, after a ruling by Judge James P. Arguelles said petitioners would have more time given pandemic circumstances.[96] Newsom's attendance at a party at The French Laundry in November 2020, despite his public health measures;[97] voter anger over lockdowns, job losses, school and business closures;[98] and a $31 billion fraud scandal at the state unemployment agency,[99] were credited for the recall's growing support.[98] The French Laundry event took place on November 6, 2020[100] and between November 5, 2020, and December 7, 2020, over 442,000 new signatures were submitted and verified; 1,664,010 verified signatures, representing roughly 98 percent of the final verified total of 1,719,900, would be submitted from November 2020 to the new March 17, 2021 deadline.[95][101]

On September 14, 2021, the Associated Press announced the failure of the recall election to obtain the majority of votes required to remove Newsom.[102][103]

Appointments

Following California Senator Kamala Harris' win alongside Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election, Newsom appointed Secretary of State of California Alex Padilla to succeed Harris as the junior United States senator. To replace Padilla as Secretary of State, Newsom appointed Assemblywoman Shirley Weber.[104][105][106] After the confirmation by the U.S. Senate of Xavier Becerra as U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Newsom appointed Rob Bonta as Attorney General of California.[107] In an interview with Joy Reid, Newsom was asked whether he would appoint a Black woman to replace Dianne Feinstein if she were to retire from the Senate before her term ended in 2024; Newsom replied that he would.[108][109]

Capital punishment

On March 13, 2019, three years after voters narrowly rejected its repeal,[110] Newsom declared a moratorium on the state's death penalty, preventing any execution in the state as long as he remained governor. The move also led to the withdrawal of the state's current lethal injection protocol and the execution chamber's closure at San Quentin State Prison.[111] In a CBS This Morning interview, Newsom said that the death penalty is "a racist system ... that is perpetuating inequality. It's a system that I cannot in good conscience support."[112] The moratorium granted a temporary reprieve for all 737 inmates on California's death row, then the largest death row in the Western Hemisphere.[113]

In January 2022, Newsom directed the state to begin dismantling its death row in San Quentin, to be transformed into a "space for rehabilitation programs",[114] as all the condemned inmates are moving to other prisons that have maximum security facilities. The state's voters upheld capital punishment in 2012 and 2016, with the latter measure agreeing to move the condemned to other prisons.[115] Though a 2021 poll by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies and co-sponsored by the Los Angeles Times suggested declining support for the death penalty among California's voters,[114][116] Newsom's moves to halt capital punishment in California were criticized by Republican opponents as defiance of the will of voters, and by capital punishment advocates as denial of closure for murder victims' families.[114]

Clemency

In response to the Trump administration's crackdown on immigrants with criminal records, he gave heightened consideration to people in this situation.[117] A pardon can eliminate the grounds for deportation of immigrants who would otherwise be legal permanent residents. Pardon requests from people facing deportation are provided with an expedited review by the state Board of Parole Hearings per a 2018 California law.[117] In his first acts of clemency as governor, he pardoned seven formerly incarcerated people in May 2019, including two Cambodian refugees facing deportation.[118] He pardoned three men who were attempting to avoid being deported to Cambodia or Vietnam in November 2019. They had separately committed crimes when they were each 19 years old.[119] He granted parole to a Cambodian refugee in December 2019 who had been held in a California prison due to a murder case. Although immigrant rights groups wanted Newsom to end policies allowing the transfer to federal agents, he was turned over for possible deportation upon release.[120]

Newsom denied parole to Sirhan Sirhan on January 13, 2022, the 1968 assassin of Robert F. Kennedy who had been recommended for parole by a parole board following Sirhan serving 53 years in prison for the murder.[121] Newsom wrote an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, saying Sirhan "still lacks the insight that would prevent him from making the kind of dangerous and destructive decisions he made in the past. The most glaring proof of Sirhan’s deficient insight is his shifting narrative about his assassination of Kennedy, and his current refusal to accept responsibility for it.”[122]

COVID-19 pandemic

Newsom declared a state of emergency on March 4, 2020, after the first death in California attributable to the novel SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus disease (COVID-19).[123][124] His stated intention was to help California prepare for and contain the spread of COVID-19.[125] The emergency declaration allowed state agencies to more easily procure equipment and services, share information on patients and alleviated restrictions on the use of state-owned properties and facilities. Newsom also announced that mitigation policies for the state's estimated 108,000 unsheltered homeless people would be prioritized with a significant push to move them indoors.[126]

Newsom issued an executive order that allowed the state to commandeer hotels and medical facilities to treat COVID-19 patients, and permitted government officials to hold teleconferences in private without violating open meeting laws.[127] He also directed local school districts to make their own decisions on school closures, but used an executive order to ensure students' needs would be met whether or not their school was physically open. The Newsom administration's request was approved by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to offer meal service during school closures, which included families being able to pick up those meals at libraries, parks, or other off-campus locations. Roughly 80% of students at California's public schools receive free or reduced-price meals. This executive order included continued funding for remote learning opportunities and child care options during workday hours.[128]

As the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the state continued to rise, on March 15, he urged people 65 and older and those with chronic health conditions to isolate themselves from others. He also called on bars, and brewery and winery tasting rooms statewide, to close their doors to patrons. Some local jurisdictions had mandatory closures.[129] The closures were extended to movie theaters and health clubs. He asked restaurants to stop serving meals inside their establishments and offer take-out meals only.[130] His statewide order to stay at home became mandatory on March 19. While it allowed movement outside the home for necessities or recreation, people were required to maintain a safe distance apart.[131] Activity "needed to maintain continuity of operation of the federal critical infrastructure sectors, critical government services, schools, childcare, and construction" was excluded from the order. Essential services such as grocery stores and pharmacies remained open. Newsom provided state funds to pay for protective measures such as hotel room lodging for hospital and other essential workers fearing returning home and infecting family members.[132] By April 26, he had issued thirty executive orders under the state of emergency while the legislature had not been in session.[133]

On April 28, Newsom, along with the governors of Oregon and Washington, announced a "shared approach" for reopening their economies.[134][135] His administration outlined key indicators for altering his stay-at-home mandate, including the ability to closely monitor and track potential cases, prevent infection of high-risk people, increase surge capacity at hospitals, develop therapeutics, ensure physical distancing at schools, businesses, and child-care facilities, and develop guidelines for restoring isolation orders if the virus surges.[136] The plan to end the shutdown consisted of four phases.[137] Newsom emphasized that easing restrictions would be based on data, not dates, stating "We will base reopening plans on facts and data, not on ideology. Not what we want. Not what we hope."[138] Regarding a return of Major League Baseball and the NFL, he said, "I would move very cautiously in that expectation."[139]

In early May, he announced that certain retailers could reopen for pickup. While the majority of Californians approved of the governor's handling of the crisis and were more concerned about reopening too early than too late, there were demonstrations and protests against these policies.[140] Under pressure, Newsom delegated more decision-making for reopening down to the local level.[141] That same month, Newsom announced a plan for registered voters to have the option to vote by mail in the November election.[142] California was the first state in the country to commit to sending mail-in ballots to all registered voters for the November general election.[143]

As the state opened up, an analysis by the Los Angeles Times found that new coronavirus hospitalizations in California began accelerating around June 15 at a rate not seen since early April, immediately after the coronavirus began rapidly spreading throughout the state.[144] On June 18, he made face-coverings mandatory for all Californians in an effort to reduce the spread of COVID-19.[145][146] Enforcement would be up to business owners, as local law enforcement agencies view non-compliance as a minor infraction.[147] By the end of June, he had ordered seven counties to close bars and nightspots, and recommended eight other counties take action on their own to close those businesses due to a surge of coronavirus cases in some parts of the state.[148] In a regular press conference on July 13 as he was ordering the reinstatement of the shutdown of bars and indoor dining in restaurants, he said, "We're seeing an increase in the spread of the virus, so that's why it's incumbent upon all of us to recognize soberly that COVID-19 is not going away any time soon until there is a vaccine or an effective therapy".[144]

Newsom oversaw a sluggish initial rollout of vaccines; California had one of the lowest vaccination rates in the country by January 2021,[149] and California had only used about 30% of the vaccines it had at its disposal, a far lower rate than other states, by January 20.[150] After reaching high approval ratings, specifically 64% in September 2020, a UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll from February 2021 showed that Newsom's approval rate was down to 46%, with 48% disapproval, the highest of his tenure. The Los Angeles Times attributed this decline to public sentiment around his management during the COVID-19 pandemic.[151] The vaccination rate increased since January, with over half the population fully vaccinated as of September 2021,[152] the percentage ranking #16 out of the 50 states.

Despite Newsom's administration enacting some of the country's toughest pandemic restrictions, California ultimately had the 29th-highest death rate out of all 50 states by May 2021. Monica Gandhi, a leading COVID-19 expert from UCSF, said that California's restrictive approach "did not lead to better health outcomes", and criticized California's delay in implementing new CDC recommendations absolving the fully vaccinated from most indoor mask requirements, while saying the decision lacked scientific rationale and could cause "collateral damage".[153][154]

Donations to spouse's nonprofit organization

Jennifer Siebel Newsom's non-profit organization, The Representation Project, was reported by The Sacramento Bee to have received upwards of $800,000 in donations from corporations that had lobbied the state government in recent years, including PG&E, AT&T, Comcast, and Kaiser Permanente. Siebel Newsom received $2.3 million in salary from the non-profit since launching it in 2011. In 2021, Governor Newsom said that he saw no conflict in his wife's nonprofit accepting donations from companies that lobby his administration.[155]

Environment

Newsom vetoed SB 1 in September 2019 which would have preserved environmental protections, of which the Trump administration were set to roll back by the government's relinquishment of endangered species protections.[156] The Newsom administration intends to sue federal agencies over the rollbacks to protect imperiled fish in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta in 2019.[157]

He attended the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit where he spoke of California as a climate leader due to the actions of Republicans and Democrats who held the office before him.[158][156] In August 2020, Gavin Newsom addressed the 2020 Democratic National Convention. His speech made mentions of climate change and the wildfires prevalent in California at the time.[159] On September 23, 2020, Newsom signed an executive order to phase out sales of gasoline-powered vehicles and require all new passenger vehicles sold in the state to be zero-emission by 2035.[160] Bills he signed in September with an environmental theme included a commission to study lithium extraction around the Salton Sea.[161]

Gun laws

As lieutenant governor in 2016, he was the official proponent of Proposition 63. The ballot measure required a background check and California Department of Justice authorization to purchase ammunition among other gun control regulations. In response to the 2019 mass shooting in Virginia Beach, he called for nationwide background checks on people purchasing ammunition.[162] Later that year, he responded to the Gilroy Garlic Festival shooting by stating his support for the 2nd Amendment and saying he would like national cooperation controlling "weapons of goddamned mass destruction".[163] He also commented that "These shootings overwhelmingly, almost exclusively, are males, boys, 'men' — I put in loose quotes, I do think that is missing in the national conversation."[164]

On June 10, 2021, Newsom called federal Judge Roger Benitez "a stone cold ideologue" and "a wholly owned subsidiary of the gun lobby of the National Rifle Association" after his ruling that struck down California's statewide ban on assault weapons.[165] While California's ban remained in place as the state appealed the ruling, Newsom proposed legislation that would empower private citizens to enforce California's ban on assault weapons after the United States Supreme Court declined to strike down the Texas Heartbeat Act (which similarly empowers private citizens to report unauthorized abortions).[166]

Healthcare

Reducing the cost of healthcare and increasing access in California were issues that Newsom campaigned on. He also indicated his support for creating a universal healthcare system in California.[167] The budget passed in June 2019 expanded eligibility for Medi-Cal from solely undocumented minor children to undocumented young adults from ages 19 to 25.[167] In 2021, legislation signed by Newsom expanded Medi-Cal eligibility to undocumented residents over the age of 50.[168][169]

In December 2021, Newsom announced his intention to make California a “sanctuary” for abortion, which included possibly paying for procedures, travel, and lodging for out-of-state abortion seekers, if the procedure is banned in Republican-led states.[170] In March 2022, Newsom signed a bill that would require all private health insurance plans in the state to fully cover abortion procedures, by eliminating associated co-pays and deductibles and increasing insurance premiums.[171]

Newsom was critiziced in early 2022 for walking back from his support for universal healthcare and not supporting Assembly Bill 1400 in 2022 which would have instituted single-payer healthcare in California; critics suggested that opposition from business interests, which had donated large sums to the governor and to his party, had swayed his opinion.[172][173]

High-speed rail

In his February 2019 State of the State address, Newsom announced that, while work would continue on the 171-mile (275 km)[174] Central Valley segment from Bakersfield to Merced, the rest of the system would be indefinitely postponed, citing cost overruns and delays.[175] This and other actions created tension with the State Building and Construction Trades Council of California, a labor union representing 450,000 members.[176]

Homelessness and housing shortage

A poll found that California voters thought the most important issue for the governor and state Legislature to work on in 2020 was homelessness.[177] In his first week of office, Newsom threatened to withhold state funding for infrastructure to communities that failed to take actions to alleviate California's housing shortage.[178][179] In late January 2019, he announced that he would sue Huntington Beach for preventing the construction of affordable housing.[180] A year later, the city acted to settle the lawsuit by the state.[181] Newsom has been characterized as an opponent of NIMBY (not-in-my-back-yard) sentiment.[182][183][184] In 2021, Newsom signed a pair of bills into law that made zoning regulations for housing less restrictive, allowing for the construction of duplexes and fourplexes in lots that were previously zoned exclusively for single-family homes.[185]

Hydraulic fracturing

Newsom pledged during his campaign to tighten state oversight of fracking and oil extraction.[186] He imposed a moratorium in November 2019 on approval of new hydraulic fracturing and steam-injected oil drilling in the state until the permits for those projects can be reviewed by an independent panel of scientists.[187]

Native American genocide

In a speech before representatives of Native Americans in June 2019, Newsom apologized for the genocide of Native Americans approved and abetted by the California state government upon statehood in the late 19th century. By one estimate, at least 4,500 Native Californians were killed between 1849 and 1870.[188] Newsom said, "That's what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that's the way it needs to be described in the history books."[189]

Personal travel

He chose El Salvador as his first international trip as governor.[190] With nearly 680,000 Salvadoran immigrants living in California, he felt that the "state's relationship with Central America is key to California's future".[191] He was also concerned about the tens of thousands of Salvadorans that were fleeing the smallest country in Central America for the U.S. each year.[192] As governor of a state impacted by the debate of illegal immigration, he went to see first-hand the factors driving it and to build business and tourism partnerships between California and Central America. He said he wanted to "ignite a more enlightened engagement and dialogue."[193]

Police tactics

Newsom has spoken in favor of Assembly Bill 1196, which would ban carotid artery restraints and choke holds in California. He has claimed that there is no longer a place for a policing tactic "that literally is designed to stop people's blood from flowing into their brain, that has no place any longer in 21st-century practices."[194][195]

Transgender rights

In September 2020, Newsom signed into law a bill allowing California transgender inmates to be placed in prisons that correspond with their gender identity.[196][197]

Unemployment fraud and debt

In January 2021, the Los Angeles Times reported that Newsom's administration had mismanaged $11.4 billion by disbursing unemployment benefits to ineligible claimants, especially those paid through the federally funded Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program.[198] Another $19 billion in claims remained under investigation for fraud.[199] At the same time, legitimate claimants faced lengthy delays in receiving benefits.[200] The state's unemployment system had been overseen by California Labor Secretary Julie Su, a Newsom appointee, who was later appointed by President Joe Biden to serve as deputy secretary of Labor in February 2021.[200]

Political opponents attributed the crisis to the Newsom administration's failure to heed multiple warnings by federal officials of the potential for fraud, while Newsom's administration said the Trump administration's failure to provide appropriate guidance for the new federally funded program contributed to the fraud.[201] Experts said much of the fraud appeared to originate from international criminal gangs in 20 countries.[202][203][204] A report by California State Auditor Elaine Howle said $810 million was disbursed to claimants who had fraudulently filed on behalf of inmates in the state's prison system.[205]

According to The Sacramento Bee, by the summer of 2021, California owed $23 billion to the federal government for unemployment benefits paid out during the pandemic, which was 43% of all unemployment debt, owed by 13 states at the time, to the federal government.[206] Most of this debt was unrelated to the federally-funded pandemic unemployment programs that had experienced most of the fraud, and instead was due to longstanding underfunding and California's high rate of unemployment during the COVID-19 pandemic.[207]

Water management

Newsom supports a series of tentative water-sharing agreements that would bring an end to the dispute between farmers, cities, fishers, and environmentalists over how much water should be left in the state's two most important rivers, the Sacramento and San Joaquin, which flow into the Delta.[208]

Wildfires

Due to a mass die-off of trees throughout the state which potentially could increase the risk of wildfires, Newsom declared a state of emergency on March 22, 2020, in preparation for the 2020 wildfire season.[209] After declaring a state of emergency on August 18, Newsom reported that the state was battling 367 known fires, many sparked by intense thunderstorms on August 16–17.[210] His request for assistance via issuance of a federal disaster declaration in the wake of six major wildfires was rejected by the Trump administration and reversed after a call to Trump from Newsom.[211]

On June 23, 2021, the NPR station CapRadio reported that Newsom and Cal Fire had falsely claimed in January 2020 that 90,000 acres of land at risk for wildfires had been treated with fuel breaks and prescribed burns, when the actual treated area was 11,399 acres, an overstatement of 690 percent.[212][213] According to CapRadio, the fuel breaks of the 35 "priority projects" Newsom had touted, which were meant to ensure the quick evacuation of residents while preventing traffic jams and a repeat of events in the 2018 fire which destroyed Paradise, CA, where at least eight evacuees burned to death in their vehicles, were struggling to mitigate fire spread in almost every instance while failing to prevent evacuation traffic jams.[213] The same day CapRadio revealed the oversight, leaked emails showed Gavin Newsom's handpicked Cal Fire chief had ordered the removal of the original statement.[214]

KXTV in Sacramento released a series of reports chronicling PG&E's liabilities after committing 91 felonies in the Santa Rosa and Paradise fires. Newsom was accused of accepting campaign donations from PG&E in order to change the CPUC's ruling on PG&E's safety license. The rating change allowed PG&E to avoid billions of dollars in extra fees. Newsom was also accused of setting up the Wildfire Insurance Fund via AB 1054, using ratepayer fees, so PG&E could avoid financial losses[215][216] and pass the liability costs to ratepayers and taxpayers.[217][218]

Electoral history

Personal life

Newsom was baptized and raised in his father's Catholic faith. He describes himself as an "Irish Catholic rebel [...] in some respects, but one that still has tremendous admiration for the Church and very strong faith". When asked about the current state of the Catholic Church in 2008, he said the church was in crisis.[17] He said he stays with the Church because of his "strong connection to a greater purpose, and [...] higher being [...]" Newsom identifies himself as a practicing Catholic,[219] stating that he has a "strong sense of faith that is perennial: day in and day out".[17] He is the godfather of designer and model Nats Getty.[220]

In December 2001, Newsom married Kimberly Guilfoyle, a former San Francisco prosecutor and legal commentator for Court TV, CNN, and MSNBC who later[when?] became a prominent personality on Fox News. The couple married at Saint Ignatius Catholic Church on the campus of the University of San Francisco, where Guilfoyle had attended law school. The couple appeared in the September 2004 issue of Harper's Bazaar; the spread had them posed at the Getty Villa with the title the "New Kennedys".[3][221] They jointly filed for divorce in January 2005, citing "difficulties due to their careers on opposite coasts".[222] Their divorce was finalized on February 28, 2006.[223]

In January 2007, it was revealed that Newsom had an affair in mid-2005 with Ruby Rippey-Tourk, the wife of his then-campaign manager and former deputy chief of staff, Alex Tourk.[224][225] Tourk filed for divorce shortly after the revelation and left Newsom's campaign and administration.[226]

Newsom began dating film director Jennifer Siebel in September 2006. He announced he would seek treatment for alcohol use disorder in February 2007.[227] The couple announced their engagement in December 2007,[228][229] and they were married in Stevensville, Montana, in July 2008.[230] They have four children: daughter Montana Tessa Newsom,[231] son Hunter Siebel Newsom, daughter Brooklynn,[232] and son Dutch.[233]

Newsom and his family moved from San Francisco to a house they bought in Kentfield in Marin County in 2012.[234]

After his election as governor, Newsom and his family moved into the California Governor's Mansion in Downtown Sacramento and thereafter settled in Fair Oaks.[235] In May 2019, The Sacramento Bee reported that Newsom's recent $3.7 million purchase of a 12,000 square foot home in Fair Oaks was the most expensive private residence sold in the Sacramento region since the year began.[236]

In August 2021, Newsom sold a Marin County home for $5.9 million in an off-market transaction. He had originally put the property up for sale in early 2019 for $5.895 million, but removed the property from the market after a price reduction to $5.695 million. The property then sold off-market in August 2021.[237]

Works

- Gavin Newsom (2013; co-authored with Lisa Dickey). Citizenville: How to Take the Town Square Digital and Reinvent Government. London: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-1431-2447-4. OCLC 995575939.

See also

References

- ^ a b "Lone Candidate is Going All Out in District 2 Race: Newsom has his eye on". Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ "About the Mayor". The City and County of San Francisco. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Vega, Cecilia (October 27, 2007). "Newsom reflects on 4 years of ups and downs as election approaches". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 6, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- ^ a b SFGov (November 6, 2007) "Election Summary: November 6, 2007" Archived May 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco City and County Department of Elections.

- ^ Koseff, Alexei (April 26, 2021). "Newsom recall has enough signatures to make ballot, California says". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Cowan, Jill (February 23, 2021). "What to Know About Efforts to Recall Gov. Gavin Newsom". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Ronayne, Kathleen; Blood, Michael R. (September 15, 2021). "California Gov. Gavin Newsom beats back GOP-led recall". Associated Press. Sacramento. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Marinucci, Carla (May 16, 2012), "'The Gavin Newsom Show' already on TMZ's radar – thanks to Lance Armstrong scoop", blog.sfgate.com, The San Francisco Chronicle, archived from the original on April 2, 2015, retrieved February 24, 2018

- ^ Christopher, Ben (October 22, 2019). "Gov. Newsom the moderate? On this spectrum, almost every Democratic legislator is further left". Calmatters. Archived from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (March 3, 2010). "Joanna Newsom, the Changeling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 9, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ^ Luna, Taryn (August 21, 2019). "Gov. Gavin Newsom's first pet? An otter, he tells 2nd-graders in Paradise, Calif". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chuck Finnie; Rachel Gordon; Lance Williams (March 23, 2003). "Newsom's Portfolio: Mayoral hopeful has parlayed Getty money, family ties and political connections into local prominence". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved March 11, 2008.

- ^ Newsom, Gavin (March 8, 2020). Citizenville. Santa Clara, California: Penguin. p. 49. ISBN 978-0143124474.

- ^ a b c d e f Julian Guthrie (December 7, 2003). "Gonzalez, Newsom: What makes them run From modest beginnings, Newsom finds connections for business, political success". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c Mike Weiss (January 23, 2005). "Newsom in Four Acts What shaped the man who took on homelessness, gay marriage, Bayview-Hunters Point and the hotel strike in one year". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 6, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c George Raine (March 11, 1997). "Newsom's Way: He hopes business success can translate to public service". The San Francisco Examiner. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c Boffi, Kristen (April 12, 2008). "San Francisco's Gavin Newsom sits down with The Santa Clara Newsom discusses how Santa Clara guides his career". The Santa Clara. Archived from the original on April 26, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ Byrne, Peter (April 2, 2003). "Bringing Up Baby Gavin". SF Weekly. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ Cecilia M. Vega (April 1, 2008). "Mayor has financial holdings at Napa, Tahoe". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ "Newsom Penthouse For Sale". San Francisco Luxury, SFLuxe.com. April 24, 2009. Archived from the original on May 17, 2009. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- ^ John King (February 4, 1997). "S.F.'s New Supervisor – Bold, Young Entrepreneur". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Gordon, Rachel (February 14, 1997). "Newsom gets his political feet wet Newest, youngest supervisor changes his tune after a chat with the mayor". The San Francisco Examiner. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Ray Delgado (February 3, 1997). "Board gets a straight white male Mayor's new supervisor is businessman Gavin Newsom, 29". The San Francisco Examiner. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Gordon, Rachel (October 16, 1998). "Fights idea that he's a Brown "appendage'". San Francisco Guardian. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ Edward Epstein (October 2, 1998). "Muni Riders Back Newsom And Ammiano". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ^ "How San Francisco Voted". The San Francisco Chronicle. November 5, 1998. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Carol Lloyd (October 29, 2003). "From Pacific Heights, Newsom Is Pro-Development and Anti-Handout". SF Gate. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ "Bill Text – SB-7 Environmental quality: Jobs and Economic Improvement Through Environmental Leadership Act of 2021". leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Dakota (October 23, 2018). "Gavin Newsom's approach to fixing homelessness in San Francisco outraged activists. And he's proud of it". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Gordon, Rachel; Simon, Mark (December 10, 2003). "Newsom: 'The Time for Change is Here'". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c Carol Lloyd (December 21, 2003). "See how they ran". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 4, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Buchanan, Wyatt (May 1, 2008). "S.F.'s Care Not Cash a success, audit shows". SFGate. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ Wildermuth, John; Gordon, Rachel (November 12, 2003). "Mayoral hopefuls come out swinging in debate". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c d John Wildermuth; Katia Hetter; Demian Bulwa (December 3, 2003). "SF Campaign Notebook". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Joan Walsh (December 9, 2003). "San Francisco's Greens versus Democrats grudge-match". Salon.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Gordon, Rachel; Guthrie, Julian; Joe Garofoli (November 5, 2003). "It's Newsom vs. Gonzalez Headed for run-off: S.F.'s 2 top vote-getters face off Dec. 9". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Gordon, Rachel (January 9, 2004). "Mayor Newsom's goal: a 'common purpose' Challenges Ahead: From potholes to the homeless". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- ^ Gordon, Rachel; Simon, Mark (January 8, 2006). "Mayor's challenge: finishing what he started". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ^ Cecilia M. Vega; Wyatt Buchanan (June 3, 2007). "San Francisco Newsom faces few hurdles to re-election Position available: Progressives rally but fail to find a candidate". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Cecilia M. Vega (August 11, 2007). "Newsom lacks serious challengers, but lineup is full of characters". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ C.W. Nevius (September 6, 2007). "When Newsom gets a free pass for 4 more years, nobody wins". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Cecilia M. Vega (August 3, 2007). "Far-out in front – Newsom is raising war-size war chest". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Cecilia M. Vega (January 18, 2008). "Newsom's $139,700 office spending spree". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Cecilia M. Vega; John Wildermuth; Heather Knight (November 7, 2007). "Newsom's 2nd Act His Priorities: Environment, homelessness, education, housing, rebuilding S.F. General". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Lisa Leff (August 10, 2007). "Newsom set to endorse Clinton for president". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- ^ a b Gavin Newsom wasn’t always such a liberal crusader Archived May 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Sacramento Bee, Christopher Cadelago, July 19, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ Unite Here Local 2, "History" Archived October 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Cities, counties may be allowed to restrict specific dog breeds". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Utsandiego.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ Knight, Heather (March 27, 2009). "S.F. Dems blast mayor in sanctuary city case". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Top Policy Groups Take Action to Create Healthy Communities, Prevent Childhood Obesity". Leadership for Healthy Communities. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Allday, Erin (November 30, 2008). "S.F. food policy heading in a healthy direction". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ "PressRoom_NewsReleases_2008_82219 « Office of the Mayor". Sfgov.org. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Knight, Heather (August 4, 2008). "S.F. pushes legislation to promote good health". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 19, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Shih, Gerry (February 19, 2010). "Gavin Newsom, the Twitter Prince". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Dolan, Maura (May 16, 2008). "California Supreme Court overturns gay marriage ban". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 19, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- ^ "San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom fights for same-sex marriage". Abclocal.go.com. October 29, 2008. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Allday, Erin (November 6, 2008). "Newsom was central to same-sex marriage saga". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ "Newsom seeks to get beyond Prop. 8 fiasco in quest to become governor - Sacramento Politics - California Politics | Sacramento Bee". February 11, 2009. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Jonathan Darman (January 17, 2009). "SF Mayor Gavin Newsom Risks Career on Gay Marriage". Newsweek. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ "An interview with Gavin Newsom - Washington Blade". December 1, 2008. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Matier, Phillip; Ross, Andrew (August 24, 2009). "Campaign 2010/Mayor Newsom wants to move on up to the governor's place/Campaign expected to be very crowded and very expensive". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ "Governor 2010: New Field Poll – Things Look Bad For Newsom, Not So Bad for Feinstein and Villaraigosa". Johnny California. November 12, 2008. Archived from the original on May 7, 2010. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Barabak, Mark Z.; Halper, Evan (October 31, 2009). "Gavin Newsom drops out of California governor's race". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ Selway, William (April 21, 2009). "San Francisco Mayor Joins Race for California Governor in 2010". Bloomberg. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Harrell, Ashley (September 9, 2009). "The Wrong Stuff". SF Weekly. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "Statement by Mayor Gavin Newsom" (Press release). Gavin Newsom for a Better California. October 30, 2009. Archived from the original on November 2, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ^ "Gavin Newsom, San Francisco mayor, files papers in lieutenant governor race". News10.net. February 17, 2010. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Coté, John (March 12, 2010). "City Insider: It's official: Newsom's running for lieutenant governor". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 14, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ^ "PolitiCal". Los Angeles Times. June 8, 2010. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "Brown, Newsom, Boxer elected". The Stanford Daily. Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Aaron Sankin (May 29, 2012). "Gavin Newsom on Sacramento". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ "Former San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom Re-Elected California Lieutenant Governor". CBS News. November 4, 2014. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ a b Ulloa, Jazmine. "Essential Politics July archives". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ a b "California gubernatorial candidates share views on criminal justice changes". sacbee.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ Cadelago, Christopher (July 21, 2015). "Gavin Newsom's panel: Marijuana shouldn't be California's next Gold Rush". Sacbee.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c McGreevey, Patrick (February 24, 2017). "Essential Politics: State Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra to open Washington office, cap-and-trade auction revenue results are revealed". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ "Gavin Newsom and Eloy Ortiz Oakley: Free community college tuition will drive California economy". San Jose Mercury News. November 12, 2015. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ "Oakland Launches Promise Initiative to Triple Number of College Graduates". City of Oakland. January 28, 2016. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ "L.A. puts higher education within reach for all students". City of Los Angeles. September 14, 2016. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ "California's College Promise Celebrated by Local Elected Officials, Education Leaders". California State Assembly. June 17, 2016. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ "Coalition calls for greater focus on computer science in UC, Cal State admissions". Los Angeles Times. December 2, 2015. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Eric (December 2, 2015). "Silicon Valley Urges Cal, CSU to Give Computer Science Full Credit in Admissions (Updated)". Recode.net. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ "Gov. Brown signs law to plan expansion of computer science education". EdSource. September 27, 2016. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ "Gavin Newsom places his stamp on UC sports policy; it's a start". Sacbee.com. May 11, 2016. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Leff, Lisa (May 11, 2016). "University panel adopts expanded student-athlete protections". Bigstory.ap.org. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Newsom, Gavin (2013). Citizenville: How to Take the Town Square Digital and Reinvent Government. ISBN 978-1594204722.

- ^ "Citizenville". Penguin Books. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Lucas, Scott. "Gavin Newsom and a Berkeley Professor Are Trying to Disrupt Public Opinion Polls". San Francisco Magazine. Modern Luxury. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Noveck, Beth (March 2013). "'Citizenville', by Gavin Newsom". SFGate. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ "Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, Former Sen. Sam Blakeslee Launch 'Digital Democracy'". Govtech.com. May 7, 2015. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Siders, David (February 11, 2015). "Gavin Newsom to open campaign account for governor in 2018". Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Hart, Angela (June 5, 2018). "Gavin Newsom, John Cox advance to general election in California governor's race". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ a b Martichoux, Alix (February 3, 2021). "Why do people want to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom? We explain". ABC7 Los Angeles. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "Gavin Newsom recall, Governor of California (2019–2021)". ballotpedia.org. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Korte, Lara (March 29, 2021). "The origin of the Newsom recall had nothing to do with COVID-19. Here's why it began". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ Stone, Ken (November 6, 2020). "Newsom Recall Drive Gets New Life: Signature Deadline Delayed to March 17". Times of San Diego. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Sources that reference Newsom's attendance at The French Laundry as a contributor to the recall petition:

- Marinucci, Carla (November 25, 2020). "French Laundry snafu reignites longshot Newsom recall drive". Politico. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Victoria Lozano, Alicia (December 20, 2020). "Recall effort against California governor an attempt to 'destabilize the political system,' analysts say". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Roos, Meghan (December 31, 2020). "Gavin Newsom Under Renewed Fire Over French Laundry Lobbyist as Recall Bid Gains Steam". Newsweek. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Siders, David; Marinucci, Carla (January 11, 2021). "'It's all fallen apart': Newsom scrambles to save California – and his career". Politico. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Pogue, James (February 3, 2021). "Gavin Newsom Is Blowing It". The New Republic. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Blood, Michael R. (March 17, 2021). "EXPLAINER: Why is California Gov. Newsom facing a recall?". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ Hoeven, Emily (August 4, 2021). "How much will California's EDD scandal cost Newsom in the recall election?". CalMatters. Archived from the original on September 10, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ Harris, Mary (May 3, 2021). "Are Californians Still Mad at Gavin Newsom?". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ Nuttle, Matthew (June 23, 2021). "Newsom Recall is a Go After Only 43 People Remove Their Signatures from Effort". ABC. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "California Gov. Gavin Newsom stays in power as recall fails". AP NEWS. September 14, 2021. Archived from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ Bernstein, Sharon (September 15, 2021). "TV networks". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ "Newsom names Assemblywoman Shirley Weber to succeed Padilla as California secretary of state". Los Angeles Times. December 22, 2020. Archived from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ "Harris bursts through another barrier, becoming the first female, first Black and first South Asian vice president-elect". CNN. Cable News Network. Archived from the original on December 24, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Hubler, Shawn (December 22, 2020). "Alex Padilla Will Replace Kamala Harris in the Senate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ White, Jeremy B. "Newsom will wait to announce California AG until Becerra confirmed". Politico PRO. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris. "Analysis: Gavin Newsom just tried to shove Dianne Feinstein out the door". CNN. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Quinn, Melissa (March 16, 2021). "Gavin Newsom vows to name Black woman to Senate if Dianne Feinstein steps down". CBS News. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Shafer, Scott; Lagos, Marisa (March 12, 2019). "Gov. Gavin Newsom Suspends Death Penalty in California". NPR News. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Bollag, Sophia. "'Ineffective, irreversible and immoral:' Gavin Newsom halts death penalty for 737 inmates". Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "California governor on halting executions: "It's a racist system. You cannot deny that."". CBS News. Archived from the original on March 16, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Arango, Tim (March 12, 2019). "California Death Penalty Suspended; 737 Inmates Get Stay of Execution". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Koseff, Alexei (February 9, 2022). "Is this another way to end California's death penalty?". Calmatters.

- ^ "California moves to dismantle nation's largest death row". AP News. January 31, 2022. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "Support for the death penalty is declining in California, poll shows". Los Angeles Times. May 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Willon, Phil (August 23, 2019). "She faces deportation after shooting her husband. Now Gov. Newsom could pardon her". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2019.