Phenylpiracetam

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Phenotropil, Fenotropil, Phenotropyl, Fenotropyl, Carphedon, Actitropil |

| Other names | Fonturacetam; Phenotropil; Fenotropil; 4-Phenylpiracetam; PP[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablets)[2][3] |

| Drug class | Atypical dopamine reuptake inhibitor[4] |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100%[2][3] |

| Metabolism | Not metabolized[3] |

| Onset of action | <1 hour[3][2] |

| Elimination half-life | 3–5 hours[2][3] |

| Excretion | Urine: ~40%[3] Bile, sweat: ~60%[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.214.874 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H14N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 218.256 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Boiling point | 486.4 °C (907.5 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Phenylpiracetam, also known as fonturacetam (INN) and sold under the brand names Phenotropil, Actitropil, and Carphedon among others, is a stimulant and nootropic medication used in Russia and certain other Eastern European countries in the treatment of cerebrovascular deficiency, depression, apathy, and attention, and memory problems, among other indications.[2][4][1][3] It is also used in Russian cosmonauts to improve physical, mental, and cognitive abilities.[2][1] The drug is taken by mouth.[2]

Side effects of phenylpiracetam include sleep disturbances among others.[2] The mechanism of action of phenylpiracetam was originally unknown.[2][4][5] However, it was discovered that (R)-phenylpiracetam is a selective atypical dopamine reuptake inhibitor in 2014.[4][6] In addition, phenylpiracetam interacts with certain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.[5] Chemically, phenylpiracetam is a racetam and phenethylamine and is structurally related to piracetam.[2][7]

Phenylpiracetam was first described by 1983.[8] It was approved for medical use in Russia in 2003.[2] Development of (R)-phenylpiracetam (code name MRZ-9547) in the West as a potential treatment for fatigue related to Parkinson's disease began by 2014.[9][6]

Medical uses

[edit]Phenylpiracetam is used in the treatment of a variety of different medical conditions.[2][1][3] It is specifically approved in Russia for treatment of cerebrovascular deficiency, depression, apathy, attention deficits, and memory decline.[2][1][3] It is used to improve symptoms following encephalopathy, brain injury, and glioma surgery.[2][1][3] The drug has been reported to improve symptoms of depression, anxiety, asthenia, and fatigue, as well as to improve cognitive performance and memory.[2][1][3] It also has anticonvulsant effects and has been used as an add-on therapy in epilepsy.[2][1]

Phenylpiracetam is typically prescribed as a general stimulant or to increase tolerance to extreme temperatures and stress.[10]

Clinical use of phenylpiracetam has shown to be more potent than piracetam and is used for a wider-range of indications.[2]

A few small clinical studies have shown possible links between prescription of phenylpiracetam and improvement in a number of encephalopathic conditions, including lesions of cerebral blood pathways, traumatic brain injury and certain types of glioma.[11]

Clinical trials were conducted at the Serbsky State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry. The Serbsky Center, Moscow Institute of Psychiatry, and Russian Center of Vegetative Pathology are reported to have confirmed the effectiveness of phenylpiracetam describing the following effects: improvement of regional blood flow in ischemic regions of the brain, reduction of depressive and anxiety disorders, increase the resistance of brain tissue to hypoxia and toxic effects, improving concentration and mental activity, a psycho-activating effect, increase in the threshold of pain sensitivity, improvement in the quality of sleep, and an anticonvulsant action,[12] though with the side effect of an anorexic effect in extended use.[13][14]

Available forms

[edit]Phenylpiracetam is available in the form of 100 mg oral tablets.[15][3]

Contraindications

[edit]Phenylpiracetam has a number of contraindications, such as individual intolerance.[3]

Side effects

[edit]Side effects of phenylpiracetam include insomnia or sleep disturbances, psychomotor agitation, flushing, a feeling of warmth, and increased blood pressure, among others.[2][3]

Overdoses

[edit]Overdose has not been reported.[3]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Phenylpiracetam is a racetam and is described as a stimulant.[2][4][1][3] Racetams have a variety of different pharmacological activities and have varying effects.[16][17][7][18][2] For example, phenylpiracetam is a stimulant, piracetam is a nootropic, and levetiracetam is an anticonvulsant.[16] The mechanisms of action of most racetams, with some exceptions, are unknown.[17][7][18]

Phenylpiracetam is a racemic mixture.[4] (R)-Phenylpiracetam is the most active enantiomer and is much more potent in stimulating locomotor activity than (S)-phenylpiracetam, which is ineffective.[4][19] However, (S)-phenylpiracetam retains some activity in most pharmacological tests.[4] On the other hand, in one animal test, the passive avoidance test, (S)-phenylpiracetam appeared to be antagonistic of (R)-phenylpiracetam.[4]

Dopamine reuptake inhibitor

[edit]Experiments performed on Sprague-Dawley rats in a European patent for using phenylpiracetam to treat sleep disorders showed an increase in extracellular dopamine levels after administration. The patent asserts discovery of phenylpiracetam's action as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor[20] as its basis.[21]

The peculiarity of this invention compared to former treatment approaches for treating sleep disorders is the so far unknown therapeutic efficacy of (R)-phenylpiracetam, which is presumably based at least in part on the newly identified activity of (R)-phenylpiracetam as the dopamine re-uptake inhibitor

Both enantiomers of phenylpiracetam, (R)-phenylpiracetam and (S)-phenylpiracetam, have been described in peer-reviewed research as dopamine transporter (DAT) inhibitors in rodents, confirming the patent claim.[22][23][19] Their actions at the norepinephrine transporter (NET) vary: (R)-phenylpiracetam acts as a dual norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), with 11-fold lower affinity for the NET than for the DAT, whereas the (S)-enantiomer is selective for the DAT.[19] However, whereas (R)-phenylpiracetam stimulates locomotor activity, (S)-phenylpiracetam does not do so.[4][19] This variation in effects has also been seen with other dopamine reuptake inhibitors.[24][25][26][27]

Other atypical dopamine reuptake inhibitors include modafinil,[24][25] mesocarb (Sydnocarb),[28][29][30] and solriamfetol.[31]

Other actions

[edit]Phenylpiracetam binds to α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mouse brain cortex with an IC50 of 5.86 μM.[1][32][33]

Racetams generally, but including phenylpiracetam, have been described as AMPA receptor potentiators.[34]

Animal studies

[edit]Research on animals has indicated that phenylpiracetam may have antiamnesic, antidepressant, anxiolytic, and anticonvulsant effects.[2][35]

Phenylpiracetam has been shown to reverse the sedative or depressant effects of the benzodiazepine diazepam, increases operant behavior, inhibits post-rotational nystagmus, prevents retrograde amnesia, and has anticonvulsant properties in animal models.[2][5][32][8][36]

In Wistar rats with gravitational cerebral ischemia, phenylpiracetam reduced the extent of neuralgic deficiency manifestations, retained the locomotor, research, and memory functions, increased the survival rate, and lead to the favoring of local cerebral flow restoration upon the occlusion of carotid arteries to a greater extent than did piracetam.[37]

In tests against a control, Sprague-Dawley rats given free access to less-preferred rat chow and trained to operate a lever repeatedly to obtain preferred rat chow performed additional work when given methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, and phenylpiracetam.[20] Rats administered 100 mg/kg phenylpiracetam performed, on average, 375% more work than rats given placebo, and consumed little non-preferred rat chow.[20] In comparison, rats administered 1mg/kg dextroamphetamine or 10 mg/kg methylphenidate performed, on average, 150% and 170% more work respectively, and consumed half as much non-preferred rat chow.[20]

Present data show that (R)-phenylpiracetam increases motivation, i.e., the work load, which animals are willing to perform to obtain more rewarding food. At the same time consumption of freely available normal food does not increase. Generally this indicates that (R)-phenylpiracetam increase motivation [...] The effect of (R)-phenylpiracetam is much stronger than that of methylphenidate and amphetamine.[20]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The pharmacokinetics of phenylpiracetam in humans are unpublished.[1] In any case, the drug is described as having an oral bioavailability of approximately 100%, as having an onset of action of less than 1 hour, as not being metabolized, as being excreted unchanged about 40% in urine and 60% in bile and sweat, and as having an elimination half-life of 3 to 5 hours.[2][3] In rodents, its absorption occurs within 1 hour with oral administration or intramuscular injection and its elimination half-life is 2.5 to 3 hours.[2]

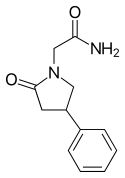

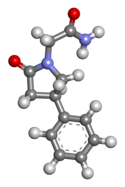

Chemistry

[edit]Phenylpiracetam, also known as 4-phenylpiracetam, is a racetam (i.e., a 2-oxo-1-pyrrolidine acetamide derivative) and the 4-phenyl-substituted analogue of piracetam.[2][8] In contrast to piracetam and most other racetams however, phenylpiracetam contains β-phenylethylamine within its chemical structure and hence can additionally be conceptualized as a substituted phenethylamine.[38]

Phenylpiracetam is a racemic mixture of (R)- and (S)-enantiomers, (R)-phenylpiracetam (MRZ-9547) and (S)-phenylpiracetam.[38][4][6][19]

Derivatives

[edit]RGPU-95 (4-chlorophenylpiracetam) is a derivative of phenylpiracetam described as having 5- to 10-fold greater potency.[39][40] Cebaracetam (CGS-25248; ZY-15119) is a derivative of RGPU-95 in which the terminal amide has been replaced with a 2-piperazinone moiety.[41]

Methylphenylpiracetam, including all four of its stereoisomers (especially the (4R,5S)-enantiomer E1R), is a positive allosteric modulator of the sigma σ1 receptor.[4][42][43] It is currently the only known racetam demonstrating σ1 receptor modulation.[4] Whereas phenylpiracetam stimulates locomotor activity in animals, the E1R enantiomer of methylphenylpiracetam does not do so at doses of up to 200 mg/kg.[4][43]

Phenylpiracetam hydrazide is a hydrazide derivative of phenylpiracetam described as having anticonvulsant effects.[7][44]

Other derivatives of phenylpiracetam have also been developed and studied.[7]

History

[edit]Phenylpiracetam was first described in the scientific literature by 1983.[8] It was developed in 1983 as a medication for Soviet cosmonauts to treat the prolonged stresses of working in space. Phenylpiracetam was created at the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Biomedical Problems in an effort led by psychopharmacologist Valentina Ivanovna Akhapkina (Валентина Ивановна Ахапкина).[45][46] Subsequently, it became available as a prescription drug in Russia. It was approved in 2003 for treatment of various conditions.[2]

Pilot-cosmonaut Aleksandr Serebrov described being issued and using phenylpiracetam, as well as it being included in the Soyuz spacecraft's standard emergency medical kit, during his 197-days working in space aboard the Mir space station. He reported "the drug acts as the equalizer of the whole organism, "tidying it up", completely excluding impulsiveness and irritability inevitable in the stressful conditions of space flight."[45]

Society and culture

[edit]Availability

[edit]

While not prescribed as a pharmaceutical in the West, in Russia and certain other Eastern European countries it is available as a prescription medicine under brand names including Phenotropil (also spelled Fenotropil, Phenotropyl, and Fenotropyl), Actitropil, and Nanotropil, among others.

Phenylpiracetam is not scheduled by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as of 2016.[47]

Manufacturer

[edit]Phenylpiracetam is manufactured by the pharmaceutical companies Valenta Pharm and Pharmstandard (Pharmstandart) in Russia.[2][48][3]

Doping in sport

[edit]Phenylpiracetam has stimulant effects and may be used as a doping agent in sport.[49][50] As a result, it is on the list of stimulants banned for in-competition use by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).[51][49] This list is applicable in all Olympic sports.[51][20] Owing to its unique stimulant properties among racetams, phenylpiracetam is the only racetam on the WADA prohibited list.[50]

Research

[edit]Phenylpiracetam has been studied in the treatment of stroke and glaucoma.[2]

The more active enantiomer of phenylpiracetam, (R)-phenylpiracetam, was under development for fatigue related to Parkinson's disease.[9] However, no recent development has been reported.[9] There was also interest in the compound for fatigue related to depression and other conditions, but this was not pursued.[52][6] (R)-Phenylpiracetam has been identified as a selective atypical dopamine reuptake inhibitor (DRIs), and similarly to other DRIs, shows pro-motivational effects in animals and reverses motivational deficits.[53][54][6]

See also

[edit]- Phensuximide – a succinimide analogue

- Phenibut – also included in Russian cosmonaut medical kits

- List of Russian drugs

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gromova OA, Torshin IY (2024). "Farmakologičeskie èffekty fonturacetama (Aktitropil) i perspektivy ego kliničeskogo primenenija" [Pharmacological effects of fonturacetam (Actitropil) and prospects for its clinical use]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova [S.S. Korsakov Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry] (in Russian). 124 (8): 21–31. doi:10.17116/jnevro202412408121. PMID 39269293.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Malykh AG, Sadaie MR (February 2010). "Piracetam and piracetam-like drugs: from basic science to novel clinical applications to CNS disorders". Drugs. 70 (3): 287–312. doi:10.2165/11319230-000000000-00000. PMID 20166767.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s https://russianmeds.com/pdf/fonturacetam.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Veinberg G, Vavers E, Orlova N, Kuznecovs J, Domracheva I, Vorona M, et al. (2015). "Stereochemistry of phenylpiracetam and its methyl derivative: improvement of the pharmacological profile". Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds. 51 (7): 601–606. doi:10.1007/s10593-015-1747-9. ISSN 0009-3122.

Phenylpiracetam was originally designed as a nootropic drug for the sustenance and improvement of the physical condition and cognition abilities of Soviet space crews.2 Later, especially during the last decade, phenylpiracetam was introduced into general clinical practice in Russia and in some Eastern European countries. The possible target receptors and mechanisms for the acute activity of this drug remained unclear, until very recently it was found that (R)-phenylpiracetam (5) (MRZ-9547) is a selective dopamine transporter inhibitor that moderately stimulates striatal dopamine release.19

- ^ a b c Voronina TA (2023). "Cognitive Impairment and Nootropic Drugs: Mechanism of Action and Spectrum of Effects". Neurochemical Journal. 17 (2). Pleiades Publishing Ltd: 180–188. doi:10.1134/s1819712423020198. ISSN 1819-7124.

Phenylpiracetam, a phenyl analogue of piracetam (trade names: phenotropil, carphedon, and phenylpiracetam), was developed at the Institute of Biomedical Problems as a new generation psychostimulant that can increase the mental and physical performance of astronauts at various stages of space flights. It was experimentally established that phenylpiracetam improves learning and memory, has an antiamnesic effect, activates operant behavior, has anxiolytic, antiasthenic, and anticonvulsant effects, weakens the sedative effect of benzodiazepines, increases resistance to cold, and improves sleep [29–31]. In a model of cerebral ischemia, phenylpiracetam improves cognitive functions, reduces manifestations of neurological deficit, and is superior in effectiveness to piracetam [32, 33]. It has been shown that phenylpiracetam does not bind to GABA-A, GABA-B and dopamine receptors, or 5-HT2 serotonin receptor, but is a synaptic transmission modulator and binds to α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the cerebral cortex (IC50 = 5.86 μm) [34, 35].

- ^ a b c d e Sommer S, Danysz W, Russ H, Valastro B, Flik G, Hauber W (December 2014). "The dopamine reuptake inhibitor MRZ-9547 increases progressive ratio responding in rats". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 17 (12): 2045–2056. doi:10.1017/S1461145714000996. PMID 24964269.

Here, we tested the effects of MRZ-9547 [...], and its l-enantiomer MRZ-9546 on effort-related decision making in rats. The racemic form of these compounds referred to as phenotropil has been shown to stimulate motor activity in rats (Zvejniece et al., 2011) and enhance physical capacity and cognition in humans (Malykh and Sadaie, 2010). [...] MRZ-9547 turned out to be a DAT inhibitor as shown by displacement of binding of [125I] RTI-55 (IC50 = 4.82 ± 0.05 μM, n=3) to human recombinant DAT expressed in CHO-K1 cells and inhibition of DA uptake (IC50 = 14.5 ± 1.6 μM, n=2) in functional assays in the same cells. It inhibited norepinephrine transporter (NET) with an IC50 of 182 μM (one experiment in duplicate). The potencies for the l-enantiomer MRZ-9546 were as follows: DAT binding (Ki = 34.8 ± 14.8 μM, n=3), DAT function (IC50 = 65.5 ± 8.3 μM, n=2) and NET function (IC50 = 667 μM, one experiment performed in duplicate).

- ^ a b c d e Gouliaev AH, Senning A (May 1994). "Piracetam and other structurally related nootropics". Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 19 (2): 180–222. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(94)90011-6. PMID 8061686.

As mentioned above, no commonly accepted mechanism for the racetam nootropics has yet been established, They do not seem to act on any well characterised receptor site with the exception of nefiracetam which has high affinity for GABA, receptors (see Table 1). [...] Receptor: GABAA. Receptor ligand: [3H]muscimolA. Compound: nefiracetam. IC50: 8.5 nMB. Refs.: 222. [...] From Table 1 it is, however, evident that the piracetam-like nootropics do not exhibit high affinity for any of the receptor types tested so far (except for nefiracetam, which shows some activity at GABAA receptors)

- ^ a b c d Bobkov Iu, Morozov IS, Glozman OM, Nerobkova LN, Zhmurenko LA (April 1983). "[Pharmacological characteristics of a new phenyl analog of piracetam--4-phenylpiracetam]". Biull Eksp Biol Med (in Russian). 95 (4): 50–53. doi:10.1007/BF00838859. PMID 6403074.

- ^ a b c "MRZ 9547". AdisInsight. 4 November 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Kim S, Park JH, Myung SW, Lho DS (November 1999). "Determination of carphedon in human urine by solid-phase microextraction using capillary gas chromatography with nitrogen-phosphorus detection". The Analyst. 124 (11): 1559–1562. Bibcode:1999Ana...124.1559K. doi:10.1039/a906027h. PMID 10746314.

- ^ Savchenko AI, Zakharova NS, Stepanov IN (2005). "[The phenotropil treatment of the consequences of brain organic lesions]". Zhurnal Nevrologii I Psikhiatrii imeni S.S. Korsakova. 105 (12): 22–26. PMID 16447562.

- ^ Lybzikova GN, Iaglova Zh, Kharlamova Iu (2008). "[The efficacy of phenotropil in the complex treatment of epilepsy]". Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova (in Russian). 108 (2): 69–70. PMID 18646385.

- ^ Kalinskiĭ PP, Nazarov VV (2007). "[Use of phenotropil in the treatment of asthenic syndrome and autonomic disturbances in the acute period of mild cranial brain trauma]". Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova (in Russian). 107 (2): 61–63. PMID 18689001.

- ^ Gustov AA, Smirnov AA, Korshunova Iu, Andrianova EV (2006). "[Phenotropil in the treatment of vascular encephalopathy]". Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova (in Russian). 106 (3): 52–53. PMID 16608112.

- ^ "Phenotropil®". АО «Валента Фарм» (in Russian). Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ a b Molina-Carballo A, Checa-Ros A, Muñoz-Hoyos A (July 2016). "Treatments and compositions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a patent review". Expert Opin Ther Pat. 26 (7): 799–814. doi:10.1080/13543776.2016.1182989. PMID 27138211.

The racetams have different activities [e.g., phenylpiracetam is a stimulant developed and marketed in Russia, piracetam is a nootropic, and levetiracetam is widely used as an anticonvulsant (Figure 17)].

- ^ a b Gualtieri F, Manetti D, Romanelli MN, Ghelardini C (2002). "Design and study of piracetam-like nootropics, controversial members of the problematic class of cognition-enhancing drugs". Curr Pharm Des. 8 (2): 125–138. doi:10.2174/1381612023396582. PMID 11812254.

In general, piracetam-like nootropics show no affinity for the most important central receptors (Ki > 10 μM). A modest affinity for muscarinic receptors is shown by aniracetam (Ki = 4.4 μM [58]) and nebracetam (Ki = 6.3 μM [61]). Nefiracetam is the only one showing affinity in the nanomolar range (Ki = 8.5 nM on the GABAA receptor [58]). [...] Nefiracetam (chart (1)) is awaiting approval. It presents a variety of pharmacological actions as it is reported to activate the cholinergic, GABAergic and other monaminergic systems and to modulate N-type calcium channels [78-81].

- ^ a b Narahashi T, Moriguchi S, Zhao X, Marszalec W, Yeh JZ (November 2004). "Mechanisms of action of cognitive enhancers on neuroreceptors". Biol Pharm Bull. 27 (11): 1701–1706. doi:10.1248/bpb.27.1701. PMID 15516710.

- ^ a b c d e Zvejniece L, Svalbe B, Vavers E, Makrecka-Kuka M, Makarova E, Liepins V, et al. (September 2017). "S-phenylpiracetam, a selective DAT inhibitor, reduces body weight gain without influencing locomotor activity". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 160: 21–29. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2017.07.009. PMID 28743458. S2CID 13658335.

- ^ a b c d e f EP application 20140000021, "Use of (r)-phenylpiracetam for the treatment of sleep disorders", published 2015-07-08, assigned to Merz Pharma GmbH and Co KGaA

- ^ Kovalev, G. I., Akhapkina, V. I., Abaimov, D. A., & Firstova, Y. Y. (2007). Phenotropil as receptor modulator of synaptic neurotransmission. Nervnye Bolezni, 4, 22–26. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=617408379890668058

- ^ Boyle N, Betts S, Lu H (6 September 2024). "Monoaminergic Modulation of Learning and Cognitive Function in the Prefrontal Cortex". Brain Sciences. 14 (9). MDPI AG: 902. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090902. ISSN 2076-3425. PMC 11429557. PMID 39335398.

In recent years, the potential for cognitive enhancement through pharmacological modulation of dopamine levels in the PFC has garnered significant interest. The inverted-U functional effect of dopamine in the PFC suggests both insufficient and excessive DA levels impair cognitive performance, leading to the development of several compounds aimed at modulating dopamine levels to improve cognitive function. Many of these compounds, including CE-158, CE-123, and Sy-phenylpiracetam, work by inhibiting the dopamine transporter (DAT) to promote behavioral flexibility and cognitive enhancement in the PFC [99,100,101,102].

- ^ Zvejniece L, Zvejniece B, Videja M, Stelfa G, Vavers E, Grinberga S, et al. (October 2020). "Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activity of DAT inhibitor R-phenylpiracetam in experimental models of inflammation in male mice". Inflammopharmacology. 28 (5): 1283–1292. doi:10.1007/s10787-020-00705-7. PMID 32279140. S2CID 215731963.

- ^ a b Reith ME, Blough BE, Hong WC, Jones KT, Schmitt KC, Baumann MH, et al. (February 2015). "Behavioral, biological, and chemical perspectives on atypical agents targeting the dopamine transporter". Drug Alcohol Depend. 147: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.005. PMC 4297708. PMID 25548026.

- ^ a b Hersey M, Bacon AK, Bailey LG, Coggiano MA, Newman AH, Leggio L, et al. (2021). "Psychostimulant Use Disorder, an Unmet Therapeutic Goal: Can Modafinil Narrow the Gap?". Front Neurosci. 15: 656475. doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.656475. PMC 8187604. PMID 34121988.

- ^ Tanda G, Hersey M, Hempel B, Xi ZX, Newman AH (February 2021). "Modafinil and its structural analogs as atypical dopamine uptake inhibitors and potential medications for psychostimulant use disorder". Curr Opin Pharmacol. 56: 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2020.07.007. PMC 8247144. PMID 32927246.

- ^ Jordan CJ, Cao J, Newman AH, Xi ZX (November 2019). "Progress in agonist therapy for substance use disorders: Lessons learned from methadone and buprenorphine". Neuropharmacology. 158: 107609. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.04.015. PMC 6745247. PMID 31009632.

- ^ Nepal B, Das S, Reith ME, Kortagere S (2023). "Overview of the structure and function of the dopamine transporter and its protein interactions". Front Physiol. 14: 1150355. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1150355. PMC 10020207. PMID 36935752.

- ^ Nguyen H, Cheng MH, Lee JY, Aggarwal S, Mortensen OV, Bahar I (2024). "Allosteric modulation of serotonin and dopamine transporters: New insights from computations and experiments". Curr Res Physiol. 7: 100125. doi:10.1016/j.crphys.2024.100125. PMC 11148570. PMID 38836245.

- ^ Aggarwal S, Cheng MH, Salvino JM, Bahar I, Mortensen OV (June 2021). "Functional Characterization of the Dopaminergic Psychostimulant Sydnocarb as an Allosteric Modulator of the Human Dopamine Transporter". Biomedicines. 9 (6): 634. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9060634. PMC 8227285. PMID 34199621.

- ^ Hoy SM (November 2023). "Solriamfetol: A Review in Excessive Daytime Sleepiness Associated with Narcolepsy and Obstructive Sleep Apnoea". CNS Drugs. 37 (11): 1009–1020. doi:10.1007/s40263-023-01040-5. PMID 37847434.

- ^ a b Firstova YY, Abaimov DA, Kapitsa IG, Voronina TA, Kovalev GI (2011). "The effects of scopolamine and the nootropic drug phenotropil on rat brain neurotransmitter receptors during testing of the conditioned passive avoidance task". Neurochemical Journal. 28 (2): 130–141. doi:10.1134/S1819712411020048. S2CID 5845024.

- ^ Zhao X, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom JM, Yeh JZ, Narahashi T (April 2001). "Nootropic drug modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat cortical neurons". Mol Pharmacol. 59 (4): 674–683. doi:10.1124/mol.59.4.674. PMID 11259610.

- ^ Kadriu B, Musazzi L, Johnston JN, Kalynchuk LE, Caruncho HJ, Popoli M, et al. (December 2021). "Positive AMPA receptor modulation in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders: A long and winding road". Drug Discov Today. 26 (12): 2816–2838. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2021.07.027. PMC 9585480. PMID 34358693.

- ^ Zvejniece L, Svalbe B, Veinberg G, Grinberga S, Vorona M, Kalvinsh I, et al. (November 2011). "Investigation into stereoselective pharmacological activity of phenotropil". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 109 (5): 407–412. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00742.x. PMID 21689376.

- ^ Antonova MI, Prokopov AA, Akhapkina VI, Berlyand AS (2003). "Experimental Pharmacokinetics of Phenotropyl in Rats". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 37 (11). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 571–572. doi:10.1023/b:phac.0000016064.51030.6f. ISSN 0091-150X.

- ^ Tiurenkov IN, Bagmetov MN, Epishina VV (2007). "[Comparative evaluation of the neuroprotective activity of phenotropil and piracetam in laboratory animals with experimental cerebral ischemia]". Eksperimental'naia i Klinicheskaia Farmakologiia. 70 (2): 24–29. PMID 17523446.

- ^ a b "Fonturacetam". PubChem. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ "102. п-Хлорфенилпирацетам (RGPU-95, p-Cl-Phenylpiracetam)" [102. p-Chlorophenylpiracetam (RGPU-95, p-Cl-Phenylpiracetam)]. АИПСИН (in Russian). Retrieved 26 September 2024.

p-Chlorophenylpiracetam is a synthetic substance that is a derivative of phenylpiracetam, a nootropic drug widely used for recreational purposes. The compound, along with other analogues, was developed to obtain more powerful analogues of phenylpiracetam for the treatment of anxiety disorders. The effect of p-chlorophenylpiracetam on the human body has not been thoroughly studied. Experiments on laboratory animals have shown that the substance has the properties of an anxiolytic, antidepressant, nootropic, and in its activity, p-chlorophenylpiracetam is 5-10 times more active than phenipiracetam, therefore, the recommended doses of the substance are about 10-60 mg. Based on the few data on specialized forums, the substance begins to act 10-15 minutes after oral administration, maximum effects are achieved after 1-3 hours, the duration of action is more than 6 hours. The prevalence of the compound is currently not great due to the presence of more studied analogs on the market. Nevertheless, p-chlorophenylpiracetam has a high social danger due to its properties and the effects it has on the body. Monitoring of the spread continues.

- ^ Tiurenkov IN, Bagmetova VV, Shishkina AV, Berestovitskaia VM, Vasil'eva OS, Ostrogliadov ES (November 2010). "[Gender differences in action Fenotropil and its structural analog--compound RGPU-95 on anxiety-depressive behavior animals]". Eksp Klin Farmakol (in Russian). 73 (11): 10–14. PMID 21254591.

- ^ "Cebaracetam". PubChem. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Vavers E, Zvejniece L, Maurice T, Dambrova M (2019). "Allosteric Modulators of Sigma-1 Receptor: A Review". Front Pharmacol. 10: 223. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.00223. PMC 6433746. PMID 30941035.

- ^ a b Zvejniece L, Vavers E, Svalbe B, Vilskersts R, Domracheva I, Vorona M, et al. (February 2014). "The cognition-enhancing activity of E1R, a novel positive allosteric modulator of sigma-1 receptors". Br J Pharmacol. 171 (3): 761–771. doi:10.1111/bph.12506. PMC 3969087. PMID 24490863.

- ^ Wang PL, Chan YX, Chang CC (2023). "New synthesis of β-aryl-GABA drugs". Tetrahedron. 146. Elsevier BV: 133648. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2023.133648. ISSN 0040-4020.

- ^ a b "Фенотропил: закономерное лидерство" [Phenotropil: natural leadership]. Medi.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ Akhapkina VI, Akhapkin RV (2013). "[Identification and evaluation of the neuroleptic activity of phenotropil]". Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova (in Russian). 113 (7): 42–46. PMID 23994920.

- ^ "List of Controlled Substances" (PDF). Division Control Division. Drug Enforcement Administration, U.S. Department of Justice. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Khatoon R, Alam MA, Sharma PK (2021). "Current approaches and prospective drug targeting to brain". Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 61. Elsevier BV: 102098. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2020.102098. ISSN 1773-2247.

- ^ a b Docherty JR (June 2008). "Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)". Br J Pharmacol. 154 (3): 606–622. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124. PMC 2439527. PMID 18500382.

- ^ a b Smith AC, Stavros C, Westberg K (2020). "Cognitive Enhancing Drugs in Sport: Current and Future Concerns". Subst Use Misuse. 55 (12): 2064–2075. doi:10.1080/10826084.2020.1775652. PMID 32525422.

- ^ a b "Prohibited List" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). January 2017. p. 6.

- ^ Stutz PV, Golani LK, Witkin JM (February 2019). "Animal models of fatigue in major depressive disorder". Physiology & Behavior. 199: 300–305. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.11.042. PMID 30513290.

In a study performed by Sommer et al. (2014), healthy rats treated with the selective dopamine transport (DAT) inhibitor MRZ-9547 (Fig. 1) chose high effort, high reward more often than their untreated matched controls. Unlike similar studies, however, depressive symptoms were not induced before treatment; rather, baseline healthy controls were compared to healthy rats treated with MRZ-9547. [...] In one study, the selective DAT inhibitor MRZ-9547 increased the number of lever presses more than untreated controls (Sommer et al., 2014). The investigators concluded that such effort-based "decision making in rodents could provide an animal model for motivational dysfunctions related to effort expenditure such as fatigue, e.g. in Parkinson's disease or major depression." Based upon the findings with MRZ-9547, they suggested that this drug mechanism might be a valuable therapeutic entity for fatigue in neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. [...] A high effort bias been reported with bupropion (Randall et al., 2015), lisdexamfetamine (Yohn etal., 2016e), and the DA uptake blockers MRZ-9547 (Sommer et al., 2014), PRX-14040 (Fig. 1) (Yohn et al., 2016d) and GBR12909 (Fig. 1) (Yohn et al., 2016c).

- ^ Salamone JD, Correa M (2018). "Neurobiology and pharmacology of activational and effort-related aspects of motivation: rodent studies". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 22: 114–120. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.01.026.

Several drugs that reverse the effects of tetrabenazine also can increase selection of high-effort PROG lever pressing when administered alone, including MSX-3 [27], and the DA transport blockers MRZ-9547 [26], bupropion [28], lisdexamfetamine [45], PRX-14040 [46], and GBR12909 [53].

- ^ Salamone JD, Ecevitoglu A, Carratala-Ros C, Presby RE, Edelstein GA, Fleeher R, et al. (May 2022). "Complexities and paradoxes in understanding the role of dopamine in incentive motivation and instrumental action: Exertion of effort vs. anhedonia". Brain Research Bulletin. 182: 57–66. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.01.019. hdl:10234/200412. PMID 35151797.

Administration of TBZ reduces extracellular DA and DA D1 and D2 receptor signaling at doses that induce a low effort bias (Nunes et al. 2013). The effort-related effects of TBZ are reversible with DA agonists or drugs that block DA transport (DAT) and elevate extracellular levels of DA (Nunes et al. 2013a; Randall et al. 2014; Yohn et al. 2015a,b, 2016a,b,d; Salamone et al. 2016; Rotolo et al. 2019, 2020, 2021; Carratala-Ros et al., 2021b). Furthermore, DAT inhibitors such as lisdexamfetamine, PRX14040, MRZ-9547, GBR12909, (S)-CE-123, (S, S)-CE-158, CT 005404, as well as the catecholamine uptake inhibitor bupropion, increase selection of high-effort PROG lever pressing in rats tested on effort-based choice tasks (Sommer et al. 2014; Randall et al. 2015; Yohn et al. 2016a,b,d,e; Rotolo et al. 2019, 2020, 2021).

Further reading

[edit]- Arsenyeva KE (18 March 2007). "Опыт применения Фенотропила в клинической практике" [The Experience of Using Phenotropil in Clinical Practice] (HTML). РМЖ (Русский Медицинский Журнал) [RMS (Russian Medical Journal)] (in Russian) (6): 519. ISSN 2225-2282.

External links

[edit]- Drugs not assigned an ATC code

- Acetamides

- Anticonvulsants

- Antidepressants

- Anxiolytics

- Drugs in sport

- Drugs in the Soviet Union

- Drugs with unknown mechanisms of action

- Nicotinic agonists

- Nootropics

- Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- Phenethylamines

- Pro-motivational agents

- Racetams

- Russian drugs

- Russian inventions

- Stimulants

- Wakefulness-promoting agents

- World Anti-Doping Agency prohibited substances