James Randi Educational Foundation: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 124.148.50.10 (talk) to last revision by Discospinster (HG) |

(edit summary removed) Tag: adding email address |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Pp-semi-indef}}{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{Infobox non-profit |

|||

{{Quran|all}} |

|||

| name = James Randi Educational Foundation |

|||

The '''Quran''' ({{IPAc-en|lang|pron|k|ɔr|ˈ|ɑː|n}}{{ref|1|[n 1]}} {{Respell|kor|AHN|'}} , {{lang-ar|القرآن}} ''{{transl|ar|ALA|al-qurʼān}}'', {{IPA-ar|qurˈʔaːn|IPA}},{{ref|2|[n 2]}} literally meaning "the recitation", also [[Romanization of Arabic|romanised]] '''Qurʼan''' or '''Koran''') is the central [[religious text]] of [[Islam]], which [[Muslim]]s believe to be a revelation from [[God in Islam|God]] ({{lang-ar|الله}}, ''[[Allah]]'').<ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia|last=Nasr |first=Seyyed Hossein | authorlink=Seyyed Hossein Nasr | title=Qurʼān |year=2007| encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | accessdate=2007-11-04|location=|publisher=|url=http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-68890/Quran}}</ref> It is widely regarded as the finest piece of [[Arabic literature|literature in the Arabic language]].<ref>Chejne, A. (1969) ''The Arabic Language: Its Role in History'', University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.</ref><ref>Nelson, K. (1985) ''The Art of Reciting the Quran'', University of Texas Press, Austin</ref><ref>Speicher, K. (1997) in: Edzard, L., and Szyska, C. (eds.) ''Encounters of Words and Texts: Intercultural Studies in Honor of Stefan Wild''. Georg Olms, Hildesheim, pp. 43–66.</ref><ref>Taji-Farouki, S. (ed.) (2004) ''Modern Muslim Intellectuals and the Quran'', Oxford University Press, Oxford</ref> Muslims consider the Quran to be the only book that has been protected by God from distortion or corruption.<ref>Understanding the Qurán - Page xii, Ahmad Hussein Sakr - 2000</ref> However, some significant textual variations (employing different wordings) and deficiencies in the Arabic script mean the relationship between the text of today's Quran and an original text is unclear.<ref>Donner, Fred, "The historical context" in McAuliffe, J. D. (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to the Qur'ān'' (Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 31–33.</ref> Quranic chapters are called [[sura]]s and verses are called [[ayah]]s. |

|||

| image = [[File:JREFLogo.png|200px]] |

|||

| type = [[501(c)#501(c)(3)|501(c)(3)]] |

|||

| founded_date = 1996 |

|||

| tax_id = |

|||

| registration_id = 65-0649443 |

|||

| founder = [[James Randi]] |

|||

| location = [[Los Angeles, California]] |

|||

| coordinates = |

|||

| origins = |

|||

| key_people = [[James Randi]], Chairman, Board of Directors<br />[[D. J. Grothe]], President and CEO<br/>[[Rick Adams (internet pioneer)|Rick Adams]], Secretary, Board of Directors<br/>Daniel "Chip" Denman, Board of Directors<br/>Barb Drescher, Educational Programs Consultant |

|||

| area_served = |

|||

| product = |

|||

| mission = To promote Critical Thinking and Investigate Claims of the Paranormal |

|||

| focus = |

|||

| method = |

|||

| revenue = US$852,445<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dynamodata.fdncenter.org/990_pdf_archive/650/650649443/650649443_200812_990.pdf|title=990 Form from 2008 for The James Randi Educational Foundation(cite line 12)|publisher=Foundation Center}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=2009 Form 990|url=http://www.guidestar.org/FinDocuments//2009/650/649/2009-650649443-067106cf-9.pdf|publisher=GuideStar|accessdate=11 September 2011}}</ref> (2009) {{decrease}} 38% on 2008. {{increase}} 17% on 2009.<ref>{{cite web|title=Form 990 for 2010|url=http://www.guidestar.org/FinDocuments//2010/650/649/2010-650649443-06fcaccc-9.pdf|publisher=GuideStar|accessdate=12 September 2011}}</ref> |

|||

| endowment = |

|||

| num_volunteers = 50 |

|||

| num_employees = 3 |

|||

| num_members = |

|||

| subsid = |

|||

| owner = |

|||

| non-profit_slogan = An Educational resource on the paranormal, pseudoscientific, and the supernatural |

|||

| former name = |

|||

| homepage = {{URL|http://www.randi.org}} |

|||

| dissolved = |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

}} |

|||

Muslims believe that the Quran was verbally revealed from God to [[Muhammad]] through the angel [[Gabriel]] (''Jibril''), gradually over a period of approximately 23 years, beginning on 22 December 609 [[Common Era|CE]],<ref> |

|||

The '''James Randi Educational Foundation''' ('''JREF''') is a [[non-profit organization]] founded in 1996 by [[magic (illusion)|magician]] and [[Scientific skepticism|skeptic]] [[James Randi]]. The JREF's mission includes educating the public and the media on the dangers of accepting unproven claims, and to support research into [[paranormal]] claims in [[Randomized controlled trial|controlled scientific experimental conditions]]. |

|||

*''Chronology of Prophetic Events'', Fazlur Rehman Shaikh (2001) p. 50 Ta-Ha Publishers Ltd. |

|||

*[http://tanzil.net/#trans/en.arberry/17:105 Quran 17:105]</ref> when Muhammad was 40, and concluding in 632 CE, the year of his death.<ref name="Britannica"/><ref name = LivRlgP338>''Living Religions: An Encyclopaedia of the World's Faiths'', Mary Pat Fisher, 1997, page 338, I.B. Tauris Publishers.</ref><ref name = QuranC17V106>{{Cite quran|17|106|style=nosup}}</ref> Shortly after Muhammad's death, the Quran was collected by his companions using written Quranic materials and everything that had been memorized of the Quran.<ref name=jecampo/> |

|||

Muslims regard the Quran as the most important miracle of Muhammad, the proof of his prophethood<ref>{{cite book|last=Peters|first=F.E.|title=The Words and Will of God|year=2003|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=0-691-11461-7|pages=12–13}}</ref> and the culmination of a series of divine messages that started with the messages revealed to [[Adam]] and ended with Muhammad. The Quran assumes familiarity with major narratives recounted in the [[Books of the Bible|Jewish and Christian scriptures]]. It summarizes some, dwells at length on others and, in some cases, presents alternative accounts and interpretations of events.<ref name=sanigosian>{{cite book|last=Nigosian|first=S.A.|title=Islam : its history, teaching and practices|year=2004|publisher=Indiana Univ. Press|isbn=0-253-21627-3|pages=65–80|edition=[New ed.].}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Brannon M.|last=Wheeler|year=2002|title=Prophets in the Quran: an introduction to the Quran and Muslim exegesis|publisher=Continuum|page=15|ISBN=978-0-8264-4956-6}}</ref><ref>[http://tanzil.net/#trans/en.arberry/3:84 Quran 3:84]</ref> The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance. It sometimes offers detailed accounts of specific historical events, and it often emphasizes the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.<ref>Nasr (2003), p. 42{{full|date=July 2011}}</ref><ref>{{Cite quran|2|67|end=76|style=nosup}}</ref> The Quran is used along with the ''[[hadith]]'' to interpret [[Sharia|''sharia'' law]].<ref>''Handbook of Islamic Marketing'', Page 38, G. Rice - 2011</ref> During prayers, the Quran is recited only in Arabic.<ref>Literacy and Development: Ethnographic Perspectives - Page 193, Brian V Street - 2001</ref> |

|||

The organization administers the [[One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge]], which offers a prize of one million U.S. dollars which it will pay out to anyone who can demonstrate a supernatural or paranormal ability under agreed-upon scientific testing criteria. The JREF also maintains a legal defense fund to assist persons who are attacked as a result of their investigations and criticism of people who make paranormal claims.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://skeptoid.com/episodes/4372 |title=Prove Your Supernatural Power and Get Rich |publisher=Skeptoid.com |date=2013-07-23 |accessdate=2014-01-04}}</ref> |

|||

Someone who has memorized the entire Quran is called a ''hafiz''. Some Muslims read Quranic [[ayah]]s (verses) with [[elocution]], which is often called [[tajwid|tajwīd]]. During the month of Ramadan, Muslims typically complete the recitation of the whole Quran during [[tarawih]] prayers. |

|||

The organization is funded through member contributions, grants, and conferences. The JREF website publishes a (nominally daily) blog at randi.org, ''Swift'', which includes the latest JREF news and information, as well as exposés of paranormal claimants.<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/swift-blog.html |title = JREF Swift Blog |accessdate = 2014-01-04}} JREF Swift Blog</ref> |

|||

==Etymology and meaning== |

|||

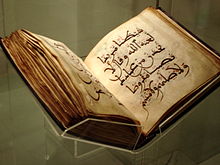

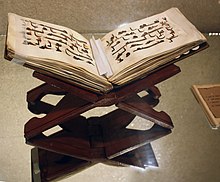

[[File:IslamicGalleryBritishMuseum3.jpg|thumb|11th-century North African Qurʼan in the [[British Museum]]]] |

|||

The word ''{{transl|ar|ALA|qurʼān}}'' appears about 70 times in the Quran itself, assuming various meanings. It is a [[verbal noun]] (''[[Arabic verbs#Verbal noun (maṣdar)|{{transl|ar|ALA|maṣdar}}]]'') of the [[Arabic language|Arabic]] verb ''{{transl|ar|ALA|qaraʼa}}'' ({{lang|ar|قرأ}}), meaning 'he read' or 'he recited.' The [[Syriac language|Syriac]] equivalent is ({{lang|syc|ܩܪܝܢܐ|}}) ''{{transl|sem|qeryānā}}'', which refers to “scripture reading” or “lesson.”<ref name="Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon">{{cite web|title=qryn|url=http://cal.huc.edu/searchroots.php?pos=N&lemma=qryn|accessdate=31 August 2013}}</ref> While some Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is ''{{transl|ar|ALA|qaraʼa}}'' itself.<ref name=Britannica /> Regardless, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad's lifetime.<ref name="Britannica"/> An important meaning of the word is the “act of reciting,” as reflected in an early Quranic passage: ''“It is for Us to collect it and to recite it ({{transl|ar|ALA|qurʼānahu}}).”''<ref>{{Cite quran|75|17|style=nosup}}</ref> |

|||

In other verses, the word refers to “an individual passage recited [by Muhammad].” Its [[liturgy|liturgical]] context is seen in a number of passages, for example: ''"So when ''{{transl|ar|ALA|al-qurʼān}}'' is recited, listen to it and keep silent."''<ref>{{Cite quran|7|204|style=nosup}}</ref> The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the [[Tawrat|Torah]] and [[Injil|Gospel]].<ref>See “Ķur'an, al-,” ''Encyclopedia of Islam Online'' and {{Cite quran|9|111}}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

|||

[[Image:randi-foundation.jpg|thumb|left|Former foundation headquarters in Florida]] |

|||

The JREF officially came into existence on February 29, 1996, when it was registered as a nonprofit corporation in the State of Delaware in the United States.<ref>{{cite web|url = https://delecorp.delaware.gov/tin/controller?JSPName=GINAMESEARCH&action=Get+Entity+Details&frmFileNumber=2597632|title = Department of State: Division of Corporations - Entity Details - The James Randi Educational Foundation|accessdate = 2012-03-03}} Delaware Dept. of State, Division of Corporations official website, Corporation Name Search: "The James Randi Educational Foundation. Incorporation Date / Formation Date: February 29, 1996. Entity Type: NON-PROFIT OR RELIGIOUS."</ref> On April 3, 1996 Randi formally announced the creation of the JREF through his email hotline:<ref> |

|||

[http://randi.org/hotline/1996/0035.html] The Randi Hotline — 1996 ''The Foundation''.</ref> It is now headquartered in Los Angeles, California.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/contact-the-jref/12-contacts/18-jref-postal-address.html |title=JREF postal address |publisher=Randi.org |date= |accessdate=2013-07-02}}</ref> |

|||

The term also has closely related [[synonym]]s that are employed throughout the Quran. Each synonym possesses its own distinct meaning, but its use may converge with that of ''{{transl|ar|ALA|qurʼān}}'' in certain contexts. Such terms include ''{{transl|ar||[[kitab|kitāb]]}}'' (book); ''{{transl|ar||[[ayah|āyah]]}}'' (sign); and ''{{transl|ar||[[Sura|sūrah]]}}'' (scripture). The latter two terms also denote units of revelation. In the large majority of contexts, usually with a [[definite article]] (''al-''), the word is referred to as the “revelation” (''[[wahy|waḥy]]''), that which has been “sent down” (''[[tanzil|tanzīl]]'') at intervals.<ref>{{Cite quran|20|2|style=nosup}} cf.</ref><ref>{{Cite quran|25|32|style=nosup}} cf.</ref> Other related words are: ''{{transl|ar|ALA|[[dhikr]]}}'' (remembrance), used to refer to the Quran in the sense of a reminder and warning, and ''{{transl|ar||ḥikmah}}'' (wisdom), sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.<ref name=Britannica /><ref>According to Welch in the ''Encyclopedia of Islam'', the verses pertaining to the usage of the word ''hikma'' should probably be interpreted in the light of IV, 105, where it is said that ''“Muhammad is to judge (''tahkum'') mankind on the basis of the Book sent down to him.”''</ref> |

|||

{{Cquote|THE FOUNDATION IS IN BUSINESS! It is my great pleasure to announce the creation of the James Randi Educational Foundation. This is a non-profit, tax-exempt, educational foundation under Section 501(c)3 of the Internal Revenue Code, incorporated in the State of Delaware. The Foundation is generously funded by a sponsor in Washington D.C. who wishes, at this point in time, to remain anonymous.|||''The Foundation'', Randi Hotline, Wed, April 3, 1996}} |

|||

The Quran describes itself as "the discernment or the criterion between truth and falsehood" (''al-furqān''), "the mother book" (''umm al-kitāb''), "the guide" (''[[Huda (name)|huda]]''), "the wisdom" (''[[hikmah]]''), "the remembrance" (''dhikr'') and "the revelation" (''tanzīl''; something sent down, signifying the descent of an object from a higher place to lower place).<ref name=Jaffer>{{cite book|last= Abbas Jaffer, Masuma Jaffer|title=Quranic Sciences|publisher=ICAS press|year=2009|isbn=1-904063-30-6|pages=11–15}}</ref> Another term is ''{{transl|ar|ALA|al-kitāb}}'' (the book), though it is also used in the Arabic language for other scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels. The adjective of Quran has multiple transliterations including quranic, koranic and qur'anic, or capitalised as Qur'anic, Koranic and Quranic. The term ''[[mus'haf|muṣḥaf]]'' ('written work') is often used to refer to particular Quranic manuscripts but is also used in the Quran to identify earlier revealed books.<ref name="Britannica" /> Other transliterations of Quran include "al-Coran", "Coran", "Kuran" and "al-Qurʼan". |

|||

Randi says [[Johnny Carson]] was a major sponsor, giving several six-figure donations.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.randi.org/jr/carson.html |title=A Good Friend Has Left Us |author=James Randi |publisher=JREF |quote=John was generous, kind, and caring. The JREF received several checks — 6-figure checks}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

The officers of the JREF are:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sunbiz.org/scripts/cordet.exe?action=DETFIL&inq_doc_number=F97000005907&inq_came_from=NAMFWD&cor_web_names_seq_number=0000&names_name_ind=&names_cor_number=&names_name_seq=&names_name_ind=&names_comp_name=JAMESRANDIEDUCATIONALFOUNDATIO&names_filing_type=|title = filing with Florida State Department|publisher=Florida Department of State Division of Corporations|accessdate=26 August 2012}}</ref> |

|||

===Prophetic era=== |

|||

*Director, Chairman: James Randi, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. |

|||

{{See also|Wahy}} |

|||

*Director, Secretary, Assistant Secretary: Richard L. Adams Jr., Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. |

|||

[[File:Cave Hira.jpg|thumb|150 px|Cave of Ḥirā, location of Muhammad's first revelation.]] |

|||

*Director, Secretary: Daniel Denman, Silver Spring, Maryland. |

|||

Islamic tradition relates that [[Muhammad]] received [[Muhammad's first revelation|his first revelation]] in the [[Hira|Cave of Hira]] during one of his isolated retreats to the mountains. Thereafter, he received revelations over a period of 23 years. According to ''[[hadith]]'' and Muslim history, after Muhammad [[Hijra (Islam)|emigrated to Medina]] and formed an independent Muslim community, he ordered many of his [[sahabah|companions]] to recite the Quran and to learn and teach the laws, which were revealed daily. It is related that some of the Quraish who were taken prisoners at the battle of Badr, regained their freedom after they had taught some of the Muslims the simple writing of the time. Thus a group of Muslims gradually became literate. As it was initially spoken, the Quran was recorded on tablets, bones and the wide, flat ends of date palm fronds. Most chapters were in use amongst early Muslims since they are mentioned in numerous sayings by both [[Sunni]] and [[Shia]] sources, relating Muhammad's use of the Qurʼan as a call to Islam, the making of prayer and the manner of recitation. However, the Quran did not exist in book form at the time of Muhammad's death in 632 CE.<ref name=tabatabai5>{{cite book|last=Tabatabai|first=Sayyid M. H.|title=The Qur'an in Islam : its impact and influence on the life of muslims|year=1987|publisher=Zahra Publ.|isbn=0710302665|url=http://www.al-islam.org/quraninislam/5.htm}}</ref><ref name=watt>{{cite book|last=Richard Bell (Revised and Enlarged by W. Montgomery Watt)|title=Bell's introduction to the Qur'an|year=1970|publisher=Univ. Press|isbn=0852241712|pages=31–51}} |

|||

</ref><ref name=chi>{{cite book|last=P. M. Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton and Bernard Lewis|title=The Cambridge history of Islam|year=1970|publisher=Cambridge Univ. Press|isbn=9780521291354|pages=32|edition=Reprint.}}</ref> There is agreement among scholars that Muhammad himself did not write down the revelation.<ref name=denffer>{{cite book|last=Denffer|first=Ahmad von|title=Ulum al-Qur'an : an introduction to the sciences of the Qur an|year=1985|publisher=Islamic Foundation|isbn=0860371328|pages=37|edition=Repr.}}</ref> |

|||

Orthodox Muslims believe that the Quran is the unchanging Word of God. However, some non-Islamic scholars believe differently. For example, "Dr. Gerd R Puin, a renowned [[Islamicist]] at [[Saarland University]], Germany, says it is not one single work that has survived unchanged through the centuries. It may include stories that were written before the prophet Mohammed began his ministry and which have subsequently been rewritten."<ref name=theguardian.com>{{cite news|last=Taher|first=Abul|title=Querying the Koran|url=http://www.theguardian.com/education/2000/aug/08/highereducation.theguardian|newspaper=The Guardian|date=8 August 2000}}</ref> Based on his analysis of [[Sana'a manuscript]], Puin claims that the Quran contains stories that were written before prophet Mohammed began his ministry and which have subsequently been rewritten. His findings were controversial—and offensive enough to Muslims that the authorities who hold the manuscript denied Puin further access to them. Allen Jones, lecturer in Koranic Studies at [[Oxford University]], says that "trifling changes were made to the text" and notes that diacritical marks and 1,000 [[Aleph#Arabic|alifs]] (the first letter of the [[Arabic alphabet]]) were inserted into the Quran around 700 AD by [[Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf]], governor of [[Iraq]], in order to obtain more understandable version which Jones notes, "became pretty stable".<ref name="theguardian.com"/> |

|||

In 2008 the astronomer [[Philip Plait]] became the new president of the JREF and Randi its board chairman.<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/jref-news/208-new-jref-president-phil-plait.html| title = Phil Plait New JREF President|accessdate= August 8, 2008 |

|||

}}</ref> In December 2009 Plait left the JREF due to involvement in a television project, and [[D.J. Grothe]] assumed the position of president on January 1, 2010.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/jref-news/798-exciting-times-at-the-jref.html | title = Exciting Times at The JREF |

|||

| work = JREF News | author = James Randi| accessdate= December 21, 2009}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Surat al-Fatiha inscribed upon the shoulder blade of a camel.jpg|thumb|left|110 px|Quranic verses inscribed on the shoulder blade of a camel.]] |

|||

The San Francisco newspaper ''SF Weekly'' reported on August 24, 2009 that Randi's annual salary is about $200,000, a figure that has not changed much since the foundation's inception.<ref name = "SF-Weekly">{{cite web| title = The Demystifying Adventures of the Amazing Randi| url = http://www.sfweekly.com/2009-08-26/news/the-demystifying-adventures-of-the-amazing-randi/1| accessdate = September 5, 2009}}''SF Weekly'', August 24, 2009, online version, page 2: "One of his friends, Internet pioneer Rick Adams, put up $1 million in 1996."</ref> |

|||

[[Sahih al-Bukhari]] narrates Muhammad describing the revelations as, "Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell" and [[Aisha]] reported, "I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)."<ref>[http://www.cmje.org/religious-texts/hadith/bukhari/001-sbt.php Translation of Sahih Bukhari, Book 1]. Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement. "God's Apostle replied, 'Sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell, this form of Inspiration is the hardest of all and then this state passes off after I have grasped what is inspired. Sometimes the Angel comes in the form of a man and talks to me and I grasp whatever he says.' ʻAisha added: Verily I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the Sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)."</ref> Muhammad's first revelation, according to the Quran, was accompanied with a vision. The agent of revelation is mentioned as the "one mighty in power", the one who "appeared on the uppermost horizon and then came nearer and nearer, until he was as close to him as the distance of two bows, or even less."(53:7-8).<ref name=watt/><ref>[http://tanzil.net/#trans/en.pickthall/53:5 Quran 53:5-8]</ref> The Islamic studies scholar Welch states in the ''[[Encyclopaedia of Islam]]'' that he believes the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition at these moments may be regarded as genuine, because he was severely disturbed after these revelations. According to Welch, these seizures would have been seen by those around him as convincing evidence for the superhuman origin of Muhammad's inspirations. However, Muhammad's critics accused him of being a possessed man, a [[Clairvoyant|soothsayer]] or a [[magician (paranormal)|magician]] since his experiences were similar to those claimed by such figures well known in [[Pre-Islamic Arabia|ancient Arabia]]. Welch additionally states that it remains uncertain whether these experiences occurred before or after Muhammad's initial claim of prophethood.<ref>[[Encyclopedia of Islam]] online, Muhammad article</ref> |

|||

[[File:Iqra.jpg|thumb|210 px|Part of ''[[Al-Alaq]]'' - 96th ''sura'' of the Quran - the first revelation received by Muhammad.]] |

|||

In the Quranic verse 7:157,<ref>{{cite web|title=Quran verse 7:157|url=http://tanzil.net/#7:157}}</ref> Muhammad is described as ''"ummi"'' which is traditionally interpreted as illiterate but the meaning is rather more complex. The medieval commentators such as [[Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari|Al-Tabari]] maintained that the term induced two meanings: firstly, the inability to read or write in general and secondly, the inexperience or ignorance of the previous books or scriptures however they gave priority to the first meaning. Besides Muhammad's illiteracy was taken as a sign of the genuineness of his prophethood. For example, according to [[Fakhr al-Din al-Razi]], if Muhammad had mastered writing and reading he possibly would have been suspected of having studied the books of the ancestors. Some scholars such as [[William Montgomery Watt|Watt]] prefer the second meaning.<ref name=watt/><ref>{{cite journal|last=Günther|first=Sebastian|title=Muhammad, the Illiterate Prophet: An Islamic Creed in the Quran and Quranic Exegesis|journal=Journal of Quranic Studies|year=2002|volume=4|issue=1|pages=1–26}}</ref> |

|||

===Compilation=== |

|||

== The One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge == |

|||

{{See also|History of the Quran|Sana'a manuscript}} |

|||

In 1964, Randi began offering a prize of $US1000 to anyone who could demonstrate a paranormal ability under agreed-upon testing conditions. This prize has since been increased to $US1 million in bonds and is now administered by the JREF as the [[One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge]]. Since its inception, more than 1000 people have applied to be tested. To date no one has either been able to demonstrate their claimed abilities under the testing conditions or have not fulfilled the foundation conditions for taking the test; the prize money still remains to be claimed. |

|||

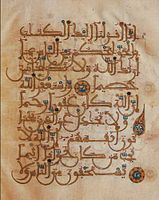

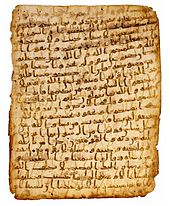

[[File:Qur'anic Manuscript - 3 - Hijazi script.jpg|thumb|upright|Quran manuscript from the seventh century CE, written on [[vellum]] in the [[Hijazi script]].]] |

|||

Based on earlier transmitted reports, in the year 632 CE, after Muhammad died and a number of his companions who knew the Quran by heart were killed in a [[Battle of Yamama|battle]] by Musaylimah, the first caliph [[Abu Bakr]] (d. 634CE) decided to collect the book in one volume so that it could be preserved. [[Zayd ibn Thabit]] (d. 655CE) was the person to collect the Quran since "he used to write the Divine Inspiration for Allah's Apostle". Thus, a group of scribes, most importantly Zayd, collected the verses and produced a hand-written manuscript of the complete book. The manuscript according to Zayd remained with Abu bakr until he died. Zayd's reaction to the task and the difficulties in collecting the Quranic material from parchments, palm-leaf stalks, thin stones and from men who knew it by heart is recorded in earlier narratives. After Abu Bakr, [[Hafsa bint Umar]], Muhammad's widow, was entrusted with the manuscript. In about 650 CE, when the third Caliph [[Uthman ibn Affan]] (d. 656CE) began noticing slight differences in pronunciation of the Quran, and as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian peninsula into [[Persia]], the [[Levant]] and North Africa, in order to preserve the sanctity of the text, ordered a committee headed by Zayd to use Abu Bakr's copy and prepare a standard copy of the Quran.<ref name=tabatabai5/><ref name=sbukhari1>{{cite web|last=al-Bukhari|first=Muhammad|title=Sahih Bukhari, volume 6, book 61, narrations number 509 and 510|url=http://www.sahih-bukhari.com/Pages/Bukhari_6_61.php|work=810-870 CE|publisher=http://www.sahih-bukhari.com|accessdate=Aug 2013}}</ref> Thus, within 20 years of Muhammad’s death, the Quran was committed to written form. That text became the model from which copies were made and promulgated throughout the urban centers of the Muslim world, and other versions are believed to have been destroyed.<ref name=tabatabai5/><ref name=rippin>{{cite book|last=Rippin, Andrew, et al.|title=The Blackwell companion to the Qur'an|year=2006|publisher=Blackwell|isbn=978140511752-4|edition=[2a reimpr.]}} |

|||

* see section ''Poetry and Language'' by Navid Kermani, p.107-120. |

|||

== The Amaz!ng Meeting == <!-- Note that [[Amazing Meeting]] redirects here --> |

|||

{{main|The Amaz!ng Meeting}} |

|||

Since 2003, the JREF has annually hosted [[The Amaz!ng Meeting]], a gathering of [[scientist]]s, [[skeptic]]s, and [[atheist]]s. Perennial speakers include [[Richard Dawkins]], [[Penn & Teller]], [[Phil Plait]], [[Michael Shermer]] and [[Adam Savage]]. |

|||

* For eschatology, see ''Discovering (final destination)'' by Christopher Buck, p.30. |

|||

== Podcasts and videos == |

|||

The foundation produces two audio podcasts, ''For Good Reason''<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.forgoodreason.org/ |title=For Good Reason podcast |publisher=Forgoodreason.org |date= |accessdate=2013-07-02}}</ref> and ''Consequence''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://consequencepodcast.com/ |title=Consequence Podcast |publisher="Consequence Podcast" |date= |accessdate=2013-07-02}}</ref> ''For Good Reason'' is an interview program hosted by [[D.J. Grothe]], promoting critical thinking and skepticism about the central beliefs of society. It has not been active since December, 2011.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.forgoodreason.org/archives/ |title=For Good Reason podcast}}</ref> ''Consequence'' is a biweekly podcast in which regular people share their personal narratives about the negative impact a belief in pseudoscience, superstition, and the paranormal has had on their lives. |

|||

* For writing and printing, see section ''Written Transmission'' by François Déroche, p.172-187. |

|||

The JREF also produces a regular video cast and YouTube show, ''The Randi Show'', in which JREF outreach coordinator Brian Thompson interviews Randi on a variety of skeptical topics, often with lighthearted or comedic commentary.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=%22the+randi+show%22%2C+playlist&lclk=playlist/a |title=The Randi Show |publisher=Youtube.com |date= |accessdate=2013-07-02}}</ref> |

|||

* For literary structure, see section ''Language'' by Mustansir Mir, p.93. |

|||

The JREF posts many of its educational videos from [[The Amazing Meeting]] and other events online. There are free lectures by [[Neil DeGrasse Tyson]], [[Carol Tavris]], [[Lawrence Krauss]], live tests of the [[One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge|Million Dollar Challenge]], workshops on [[cold reading]] by [[Ray Hyman]], and panels featuring leading thinking on various topics related to JREF's educational mission.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.youtube.com/user/JamesRandiFoundation |title=JREF Video Channel on YouTube |publisher=Youtube.com |date= |accessdate=2013-07-02}}</ref> |

|||

* For the history of compilation see ''Introduction'' by Tamara Sonn p.5-6 |

|||

The foundation produced its own "Internet Audio Show" which ran from January–December 2002 and was broadcast via a live stream. The archive can be found as mp3 files on their website<ref>{{cite web|title=Internet Audio Show|publisher=The James Randi Educational Foundation|url=http://www.randi.org/radio/radiorss.xml|date= 3 January 2002}}</ref> and as a podcast on iTunes.<ref>{{cite web|title=Internet Audio Show|author=The James Randi Educational Foundation|url=http://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/2002-james-randi-internet/id373871673|date= 3 January 2002|publisher=iTunes}}</ref> |

|||

* For recitation, see ''Recitation'' by Anna M. Gade p.481-493 |

|||

== Fellowships and scholarships == |

|||

The JREF has named a number of fellows of the organization including [[Senior Fellow]] [[Steven Novella]] and [[Research fellow|Research Fellows]] [[Karen Stollznow]], [[Tim Farley]] and Ray Hall.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/jref-news/1345-dr-ray-hall-appointed-as-new-jref-research-fellow.html | title=Dr. Ray Hall Appointed as New JREF Research Fellow | publisher=James Randi Educational Foundation | work=JREF SWIFT blog | date=July 1, 2011 | accessdate=July 10, 2011 }}</ref> Kyle Hill was added as a fellow November 2011,<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/jref-news/1516-kyle-hill-appointed-as-jref-research-fellow.html | title=Kyle Hill Appointed as JREF Research Fellow| publisher=James Randi Educational Foundation | work=JREF SWIFT blog | date=November 11, 2011 | accessdate=December 12, 2011 }}</ref> and [[Leo Igwe]] was added October 2012.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| title = Leo Igwe partners with JREF to respond to witchcraft problem in Africa| work = Doubtful News |

|||

| accessdate = 2013-02-17| url = http://doubtfulnews.com/2012/10/leo-igwe-partners-with-jref-to-respond-to-witchcraft-problem-in-africa/}}</ref> |

|||

</ref><ref>Mohamad K. Yusuff, [http://www.irfi.org/articles/articles_251_300/zayd_ibn_thabit_and_the_glorious.htm Zayd ibn Thabit and the Glorious Qur'an]</ref><ref>The Koran; A Very Short Introduction, Michael Cook. Oxford University Press, pp. 117–124</ref> The present form of the Quran text is accepted by Muslim scholars to be the original version compiled by Abu Bakr.<ref name=watt/><ref name=chi/><ref>F. E. Peters (1991), pp.3–5: “Few have failed to be convinced that … the Quran is … the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation.”</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Four JREF fellows 2011.jpg|thumb|JREF fellows [[Tim Farley]], [[Karen Stollznow]], [[Steven Novella]] and [[Ray Hall (musician)|Ray Hall]] at [[The Amaz!ng Meeting]] 9 from Outer Space July 16, 2011]] |

|||

In 2007 the JREF announced it would resume awarding [[critical thinking]] scholarships to college students after a brief hiatus due to the lack of funding.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/jref-scholarships.html |title=The James Randi Educational Foundation Scholarships |publisher=Randi.org |date=2009-04-20 |accessdate=2009-06-15}}</ref> |

|||

According to [[Shia Islam|Shia]] and some [[Sunni Islam|Sunni]] scholars, [[Ali|Ali ibn Abi Talib]] (d. 661CE) compiled a complete version of the Quran shortly after Muhammad's death. The order of this text differed from that gathered later during Uthman's era in that this version had been collected in chronological order. Despite this, he made no objection against the standardized Quran and accepted the Quran in circulation. Other personal copies of the Quran might have existed including [[Abd Allah ibn Mas'ud|Ibn Mas'ud]]'s and [[Ubayy ibn Kab]]'s codex, none of which exist today.<ref name="Britannica"/><ref name=tabatabai5/><ref name=leaman>{{cite book|last=Leaman|first=Oliver|title=The Qur'an: an Encyclopedia|year=2006|publisher=Routledge|location=New York, NY|isbn=0-415-32639-7}} |

|||

The JREF has also helped to support local grassroot efforts and outreach endeavors, such as [[SkeptiCamp]], [[Camp Inquiry]]<ref>http://CampInquiry.org</ref> and various community-organized conferences.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/jref-news/1840-jref-offers-a-number-of-scholarships-and-grants-for-students-educators-and-local-skeptic-groups.html |title=JREF Offers a Number of Scholarships and Grants for Students, Educators and Local Skeptic Groups |publisher=Randi.org |date= |accessdate=2013-07-02}}</ref> However, according to their tax filing, they spend less than $2,000 a year on other organizations or individuals.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.guidestar.org/FinDocuments/2012/650/649/2012-650649443-0924dfee-9.pdf |title=2012 JREF tax filing |publisher=Guidestar.org |title=JREF tax filing 2012 |date= |accessdate=2013-11-07}}</ref> |

|||

* For God in the Quran (Allah), see ''Allah'' by Zeki Saritoprak, p. 33-40. |

|||

* For eschatology, see ''Eschatology'' by Zeki Saritoprak, p. 194-199. |

|||

* For searching the Arabic text on the internet and writing, see ''Cyberspace and the Qur'an'' by Andrew Rippin, p.159-163. |

|||

* For calligraphy, see by ''Calligraphy and the Qur'an'' by Oliver Leaman, p 130-135. |

|||

* For translation, see ''Translation and the Qur'an'' by Afnan Fatani, p.657-669. |

|||

* For recitation, see ''Art and the Qur'an'' by Tamara Sonn, p.71-81 and ''Reading'' by Stefan Wild, p.532-535.</ref> |

|||

Quran most likely existed in scattered written form during Muhammad's lifetime. Several sources indicate that during Muhammad's lifetime a large number of his companions had memorized the revelations. Early commentaries and Islamic historical sources support the above-mentioned understanding of the Quran's early development.<ref name=jecampo>{{cite book|last=Campo|first=Juan E.|title=Encyclopedia of Islam|year=2009|publisher=Facts On File|isbn=0-8160-5454-1|pages=570–74}}</ref> The Quran in its present form is generally considered by academic scholars to record the words spoken by Muhammad because the search for variants has not yielded any differences of great significance.{{Citation needed|date=November 2012}} Although most variant readings of the text of the Quran have ceased to be transmitted, some still are. There has been no [[critical text]] produced on which a scholarly reconstruction of the Quranic text could be based.<ref name="gilliot2006p52">For both the claim that variant readings are still transmitted and the claim that no such critical edition has been produced, see Gilliot, C., "Creation of a fixed text" in McAuliffe, J. D. (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to the Qur'ān'' (Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 52.</ref> Historically, controversy over the Quran's content has rarely become an issue, although debates continue on the subject.<ref>{{cite web|last=Arthur Jeffery and St. Clair-Tisdal et al, Edited by Ibn Warraq, Summarised by Sharon Morad, Leeds|url=http://debate.org.uk/topics/books/origins-koran.html|title=The Origins of the Koran: Classic Essays on Islam's Holy Book |accessdate=2011-03-15}}</ref><ref>*F. E. Peters (1991), pp.3–5: "Few have failed to be convinced that the Quran is the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation."</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* ''[[An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural]]'' (by Randi) |

|||

In 1972, in a mosque in the city of [[Sana'a]], [[Yemen]], manuscripts were discovered that were later proved to be the most ancient Quranic text known to exist. The [[Sana'a manuscript]]s contain [[palimpsest]]s, a manuscript page from which the text has been washed off to make the parchment reusable again—a practice which was common in ancient times due to scarcity of writing material. However, the faint washed-off underlying text (''scriptio inferior'') is still barely visible and believed to be "pre-Uthmanic" Quranic content, while the text written on top (''scriptio superior'') is believed to belong to Uthmanic time.<ref name=jqs1>{{cite journal|title=‘The Qur'an: Text, Interpretation and Translation’ Third Biannual SOAS Conference, October 16–17, 2003|journal=Journal of Qur'anic Studies|year=2004|month=April|volume=6|issue=1|pages=143–145|doi=10.3366/jqs.2004.6.1.143}}</ref> Studies using [[radiocarbon dating]] indicate that the parchments are dated to the period before 671 AD with a 99 percent probability.<ref name=bergmann>{{cite journal|last=Bergmann|first=Uwe|coauthors=Sadeghi, Behnam|title=The Codex of a Companion of the Prophet and the Qurān of the Prophet|journal=Arabica|year=2010|month=September|volume=57|issue=4|pages=343–436|doi=10.1163/157005810X504518|url=http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/10.1163/157005810x504518}}</ref><ref name=sadeghi>{{cite journal|last=Sadeghi|first=Behnam|coauthors=Goudarzi, Mohsen|title=Ṣan‘ā’ 1 and the Origins of the Qur’ān|journal=Der Islam|year=2012|month=March|volume=87|issue=1-2|pages=1–129|doi=10.1515/islam-2011-0025|url=http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/islm.2010.87.issue-1-2/islam-2011-0025/islam-2011-0025.xml?format=INT}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Debunker]] |

|||

* [[List of prizes for evidence of the paranormal]] |

|||

==Significance in Islam== |

|||

* [[Pigasus Award]] |

|||

{{Islam}} |

|||

* Rationalist [[Prabir Ghosh]] increases his challenge amount to $50,000 against any claim of paranormal, after surviving nine assassination attempts. |

|||

Muslims believe the Quran to be the book of divine guidance revealed from God to [[Muhammad]] through the [[Gabriel|angel Gabriel]] over a period of 23 years and view the Quran as God's final revelation to humanity.<ref name = LivRlgP338/><ref name="autogenerated1">Watton, Victor, (1993), ''A student's approach to world religions:Islam'', Hodder & Stoughton, pg 1. ISBN 978-0-340-58795-9</ref> They also believe that the Quran has solutions to all the problems of humanity irrespective of how complex they may be and in what age they occur. |

|||

*''[[Skeptic's Dictionary]]'' by [[Robert Todd Carroll]] |

|||

[[Wahy|Revelation]] in Islamic and Quranic concept means the act of God addressing an individual, conveying a message for a greater number of recipients. The process by which the divine message comes to the heart of a messenger of God is ''[[tanzil]]'' (to send down) or ''nuzūl'' (to come down). As the Quran says, "With the truth we (God) have sent it down and with the truth it has come down."<ref>See: |

|||

*Corbin (1993), p.12{{full|date=November 2012}} |

|||

*Wild (1996), pp. 137, 138, 141 and 147{{full|date=November 2012}} |

|||

*{{Cite quran|2|97|style=nosup}} |

|||

*{{Cite quran|17|105|style=nosup}}</ref> |

|||

The Quran frequently asserts in its text that it is divinely ordained. Some verses in the Quran seem to imply that even those who do not speak Arabic would understand the Quran if it were recited to them.<ref name="jenssen2001">Jenssen, H., "Arabic Language" in McAuliffe et al. (eds.), ''[[Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān]], vol. 1'' (Brill, 2001), pp. 127-135.</ref> The Quran refers to a written pre-text, "the preserved tablet", that records God's speech even before it was sent down.<ref name=tsonn/><ref>[http://tanzil.net/#trans/en.yusufali/85:22 Quran 85:22]</ref> |

|||

The issue of whether the Quran is eternal or created became a theological debate ([[Createdness (Qu'ran)|Quran's createdness]]) in the ninth century. [[Mu'tazila]]s, an Islamic school of theology based on reason and rational thought, held that the Quran was created while the most widespread varieties of Muslim theologians considered the Quran to be co-eternal with God and therefore uncreated. [[Sufi]] philosophers view the question as artificial or wrongly framed.<ref>Corbin (1993), p.10</ref> |

|||

Muslims believe that the present wording of the Quran corresponds to that revealed to Muhammad and according to their interpretation of verse 15:9 it is protected from corruption ("Indeed, it is We who sent down the Qur'an and indeed, We will be its guardian.").<ref>{{cite book|last=Mir Sajjad Ali, Zainab Rahman|title=Islam and Indian Muslims|year=2010|publisher=Kalpaz Publications|isbn=8178358050|pages=21}}</ref> Muslims consider the Quran to be a guide, a sign of the prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the religion. They argue it is not possible for a human to produce a book like the Quran, as the Quran itself maintains. |

|||

Muslims commemorate annually the beginning of Quran's revelation on the Night of Destiny (''[[Laylat al-Qadr]]''), during the last 10 days of Ramadan, the month during which they fast from sunrise until sunset.<ref name=tsonn>{{cite book|last=Sonn|first=Tamara|title=Islam : a brief history|year=2010|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|isbn=978-1-4051-8093-1|edition=Second ed.}}</ref> |

|||

The first chapter of the Quran is repeated in daily prayers and in other occasions. This chapter, which consists of seven verses, is the most often recited chapter of the Quran:<ref name=Britannica /> |

|||

:"All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Universe, the Beneficent, the Merciful and Master of the Day of Judgment, You alone We do worship and from You alone we do seek assistance, guide us to the right path, the path of those to whom You have granted blessings, those who are neither subject to Your anger nor have gone astray."(Quran 1:1-7) |

|||

Respect for the written text of the Quran is an important element of religious faith by many Muslims and the Quran is treated with reverence. Based on tradition and a literal interpretation of the Quran verse 56:79: "none shall touch but those who are clean", some Muslism believe that a they must perform a ritual cleansing with water before touching a copy of the Quran although this view is not universal.<ref name=Britannica /> Worn-out copies of the Quran are wrapped in a cloth and stored indefinitely in a safe place, buried in a mosque or a Muslim cemetery, or burned and the ashes buried or scattered over water.<ref>[http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/explainer/2012/02/afghan_quran_burning_protests_what_s_the_right_way_to_dispose_of_a_quran_.html Afghan Quran-burning protests: What’s the right way to dispose of a Quran? - Slate Magazine]</ref> |

|||

In Islam, most intellectual disciplines including Islamic theology, [[Islamic philosophy|philosophy]], [[Sufism|mysticism]] and [[Fiqh|Jurisprudence]] have been concerned with the Quran or have their foundation in its teachings.<ref name=Britannica /> |

|||

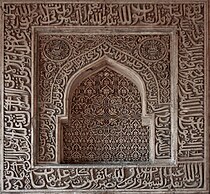

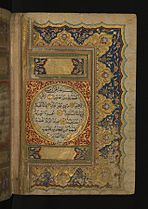

=== In Islamic Art === |

|||

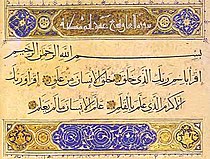

The Quran also inspired [[Islamic art]]s and specifically the so-called Quranic arts of [[Islamic calligraphy|calligraphy]] and [[Ottoman illumination|illumination]].<ref name=Britannica /> The Qurʼan is never decorated with figurative images, but many Qurʼans have been highly decorated with decorative patterns in the margins of the page, or between the lines or at the start of suras. Islamic verses appear in many other media, on buildings and on objects of all sizes, such as [[mosque lamp]]s, metal work, [[Islamic pottery|pottery]] and single pages of calligraphy for [[muraqqa]]s or albums. |

|||

<gallery widths="210px" heights="210px"> |

|||

File:Quran inscriptions on wall, Lodhi Gardens, Delhi.jpg|Quranic inscriptions, Bara Gumbad mosque, Delhi, India |

|||

File:Mosque lamp Met 91.1.1534.jpg|Typical glass and enamel [[mosque lamp]] with the ''[[Ayat an-Nur]]'' or "Verse of Light" (24:35) |

|||

File:Mausolées du groupe nord (Shah-i-Zinda, Samarcande) (6016470147).jpg|Quranic verses, Shahizinda mausoleum, Samarkand, Uzebekistan |

|||

File:Muhammad ibn Mustafa Izmiri - Right Side of an Illuminated Double-page Incipit - Walters W5771B - Full Page.jpg|Quran page decoration art, Ottoman period |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Inimitability === |

|||

{{main|I'jaz}} |

|||

Inimitability of the Quran (or "''I'jaz''") is the belief that no human speech can match the Quran in its content and form. The Quran is considered an inimitable miracle by Muslims, effective until the Day of Resurrection—and, thereby, the central proof granted to [[Muhammad]] in authentication of his prophetic status. The concept of inimitability originates in the Quran where in five different verses challenges opponents to produce something like the Quran: "If men and sprites banded together to produce the like of this Quran they would never produce its like not though they backed one another" (17:88). So the suggestion is that if there are doubts concerning the divine authorship of the Quran come forward and create something like it. From the ninth century, numerous works appeared which studied the Quran and examined its style and content. Medieval Muslim scholars including [[Abd al-Qahir al-Jurjani|al-Jurjani]] (d. 1078CE) and [[al-Baqillani]] (d. 1013CE) have written treatises on the subject, discussed its various aspects, and used linguistic approaches to study the Quran. Others argue that the Quran contains noble ideas, has inner meanings, maintained its freshness through the ages and has caused great transformations in individual level and in the history. Some scholars state that the Quran contains scientific information that agrees with modern science. The doctrine of miraculousness of the Quran is further emphasized by Muhammad's illiteracy since the unlettered prophet could not have been suspected of composing the Quran.<ref name=leaman/><ref name=sophia>{{cite journal|last=Vasalou|first=Sophia|title=The Miraculous Eloquence of the Qur'an: General Trajectories and Individual Approaches|journal=Journal of Qur'anic Studies|year=2002|volume=4|issue=2|pages=23–53}}</ref> |

|||

==Text and arrangement== |

|||

{{Main|Sura|Ayah}} |

|||

[[File:FirstSurahKoran (fragment).jpg|thumb|230 px|First sura of the Quran, ''[[Al-Fatiha]]'', consisting of seven verses.]] |

|||

The Quran consists of 114 chapters of varying lengths, each known as a ''[[sura]]''. Chapters are classified as [[Meccan sura|Meccan]] or [[Medinan sura|Medinan]], depending on whether the verses were revealed before or after the [[Hijra (Islam)|migration]] of Muhammad to the city of Medina. However, a chapter classified as Medinan may contain Meccan verses in it and vice versa. Chapter titles are derived from a name or quality discussed in the text, or from the first letters or words of the surah. Chapters are arranged roughly in order of decreasing size. The chapter arrangement is thus not connected to the sequence of revelation. Each chapter except the ninth starts with the ''[[Basmala|Bismillah]]'' ({{lang|ar|بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم}}) an Arabic phrase meaning 'In the name of God.' There are, however, still 114 occurrences of the ''bismillah'' in the Quran, due to its presence in verse 27:30 as the opening of Solomon's letter to the Queen of Sheba.<ref>See: |

|||

*“Kur`an, al-,” ''Encyclopaedia of Islam Online'' |

|||

*Allen (2000) p. 53</ref> |

|||

Each chapter consists of several verses, known as ''[[ayat]]'', which originally means a 'sign' or 'evidence' sent by God. The number of verses differs from chapter to chapter. An individual verse may be just a few letters or several lines. The total number of verses in the Quran is 6236, however, the number varies if the ''bismillahs'' are counted separately. |

|||

In addition to and independent of the division into chapters, there are various ways of dividing the Quran into parts of approximately equal length for convenience in reading. The 30 ''[[juz']]'' (plural ''ajzāʼ'') can be used to read through the entire Quran in a month. Some of these parts are known by names—which are the first few words by which the ''juzʼ'' starts. A ''[[juz']]'' is sometimes further divided into two ''[[hizb|ḥizb]]'' (plural ''aḥzāb''), and each ''hizb'' subdivided into four ''rubʻ al-ahzab''. The Quran is also divided into seven approximately equal parts, ''[[manzil]]'' (plural ''manāzil''), for it to be recited in a week.<ref name="Britannica"/> |

|||

''[[Muqatta'at]]'', or the Quranic initials, are 14 different letter combinations of 14 Arabic letters that appear in the beginning of 29 chapters of the Quran. The meanings of these initials remain unclear. |

|||

According to one estimate the Quran consists of 77,430 words, 18,994 unique words, 12,183 stems, 3,382 lemmas and 1,685 roots.<ref>{{cite web|last=Dukes|first=Kais|title=RE: Number of Unique Words in the Quran|url=http://www.mail-archive.com/comp-quran@comp.leeds.ac.uk/msg00223.html|work=www.mail-archive.com|accessdate=29 October 2012}}</ref> |

|||

== Contents == |

|||

{{Main|God in Islam|Islamic eschatology|Prophets in the Quran|Quran and science|Legends and the Quran}} |

|||

The Quranic content is concerned with the basic beliefs of Islam which include the existence of [[God in Islam|God]] and the [[Islamic eschatology|resurrection]]. Narratives of the early [[Prophets in Islam|prophets]], ethical and legal subjects, historical events of the prophet’s time, charity and [[Salat|prayer]] also appear in the Quran. The Quranic verses contain general exhortations regarding right and wrong and the historical events are related to outline general moral lessons. Verses pertaining to natural phenomena have been interpreted by Muslims as an indication of the authenticity of the Quranic message.<ref name=saeed>{{cite book|last=Saeed|first=Abdullah|title=The Qurʼan : an introduction|year=2008|publisher=Routledge|location=London|isbn=9780415421249|pages=62}}</ref> |

|||

'''Monotheism''': The central theme of the Quran is [[monotheism]]. God is depicted as living, eternal, omniscient and omnipotent (2:20,29,255). God's omnipotence appears above all in his power to create. He is the creator of everything, of the heavens and the earth and what is between them (13:16, 50:38, etc.) All human beings are equal in their utter dependence upon God, and their well-being depends upon their acknowledging that fact and living accordingly.<ref name=watt/><ref name=saeed/> |

|||

[[File:Quran rzabasi4.JPG|thumb|Written in the 12th century.]] |

|||

The Quran uses [[Cosmological argument|cosmological]] and contigency arguments in various verses without referring to the terms to prove the existence of God. Therefore, the universe is originated and needs an originator, and whatever exists must have a sufficient cause for its existence. Besides, the design of the universe, is frequently referred to as a point of contemplation: "It is He who has created seven heavens in harmony. You cannot see any fault in God's creation; then look again: Can you see any flaw?" (67:3) <ref name=leaman/> |

|||

'''Eschatology''': The doctrine of the [[Islamic eschatology|last day]] and [[eschatology]] (the final fate of the universe) may be reckoned as the second great doctrine of the Quran.<ref name=watt/> It is estimated that around a full one-third of the Quran is eschatological, dealing with the afterlife in the next world and with the day of judgment at the end of time.<ref name=rippin/> There is a reference of the afterlife on most pages of the Quran and the belief in the afterlife is often referred to in conjunction with belief in God as in the common expression: "Believe in God and the last day".<ref name=haleem>{{cite book|last=Haleem|first=Muhammad Abdel|title=Understanding the Qur'an : themes and style|year=2005|publisher=I.B. Tauris|isbn=9781860646508|pages=82}}</ref> A number of chapters such as 44, 56, 75, 78, 81 and 101 are directly related to the afterlife and its preparations. Some of the chapters indicate the closeness of the event and warn people to be prepared for the imminent day. For instance, the first verses of Chapter 22, which deal with the mighty earthquake and the situations of people on that day, represent this style of divine address: O People! Be respectful to your Lord. The earthquake of the Hour is a mighty thing."<ref name=leaman/> |

|||

The Quran is often vivid in its depiction of what will happen at the end time. Watt describes the Quranic view of End Time:<ref name=watt/> |

|||

:"The climax of history, when the present world comes to an end, is referred to in various ways. It is 'the Day of Judgment,' 'the Last Day,' 'the Day of Resurrection,' or simply 'the Hour.' Less frequently it is 'the Day of Distinction' (when the good are separated from the evil), 'the Day of the Gathering' (of men to the presence of God) or 'the Day of the Meeting' (of men with God). The Hour comes suddenly. It is heralded by a shout, by a thunderclap, or by the blast of a trumpet. A cosmic upheaval then takes place. The mountains dissolve into dust, the seas boil up, the sun is darkened, the stars fall and the sky is rolled up. God appears as Judge, but his presence is hinted at rather than described. [...] The central interest, of course, is in the gathering of all mankind before the Judge. Human beings of all ages, restored to life, join the throng. To the scoffing objection of the unbelievers that former generations had been dead a long time and were now dust and mouldering bones, the reply is that God is nevertheless able to restore them to life." |

|||

The Quran does not assert a natural immortality of the human soul, since man's existence is dependent on the will of God: when he wills, he causes man to die; and when he wills, he raises him to life again in a bodily resurrection.<ref name=rcmartin/> |

|||

'''Prophets''': According to Qur'an God communicated with man and made his will known through signs and revelations. Prophets, or 'Messengers of God', received revelations and delivered them to humanity. The message has been identical and for all humankind. "Nothing is said to you that was not said to the messengers before you, that your lord has at his Command forgiveness as well as a most Grievous Penalty."(41:43). The revelation does not come directly from God to the prophets, angels acting as God's messengers deliver the divine revelation to them. This comes out in 42:51, in which it is stated: "It is not for any mortal that God should speak to them, except by revelation, or from behind a veil, or by sending a messenger to reveal by his permission whatsoever He will."<ref name=rippin/><ref name=rcmartin>{{cite book|last=Martin|first=Richard C.|title=Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world|year=2003|publisher=Macmillan Reference USA|isbn=0028656032|pages=568-62 (By Farid Esack)|url=http://books.google.com/books?isbn=0028656032|edition=[Online-Ausg.].}}</ref> |

|||

'''Ethico-Religious concepts''': Belief is the center of the sphere of positive moral properties in the Quran. A number of scholars have tried to determine the semantic contents of the words meaning 'belief' and 'believer' in the Quran <ref name=toshihiko>{{cite book|last=Izutsu|first=Toshihiko|title=Ethico-religious concepts in the Qur'an|year=2007|publisher=McGill-Queen's University Press|isbn=0773524274|pages=184|edition=Repr. 2007}}</ref> The Ethico-legal concepts and exhortations dealing with righteous conduct are linked to a profound awareness of God, thereby emphasizing the importance of faith, accountability and the belief in each human's ultimate encounter with God. People are invited to perform acts of charity, especially for the needy. Believers who "spend of their wealth by night and by day, in secret and in public" are promised that they "shall have their reward with their Lord; on them shall be no fear, nor shall they grieve" (2:274). It also affirms family life by legislating on matters of marriage, divorce and inheritance. A number of practices such as usury and gambling are prohibited. The Quran is one of the fundamental sources of the Islamic law, or sharia. Some formal religious practices receive significant attention in the Quran including the formal prayers and fasting in the month of Ramadan. As for the manner in which the prayer is to be conducted, the Quran refers to prostration.<ref name=jecampo/><ref name=rcmartin/> The term used for charity, ''Zakat'', actually means purification. Charity, according to the Quran, is a means of self-purification.<ref name=tsonn/><ref>[http://tanzil.net/#trans/en.arberry/9:103 Quran 9:103]</ref> |

|||

== Literary style == |

|||

The Quran's message is conveyed with various literary structures and devices. In the original Arabic, the chapters and verses employ [[phonetics|phonetic]] and [[theme (literature)|thematic]] structures that assist the audience's efforts to recall the message of the text. Muslims{{Who|date=February 2010}} assert (according to the Quran itself) that the Quranic content and style is inimitable.<ref name = Issa>[[Issa Boullata]], "Literary Structure of Quran", ''Encyclopedia of the Qurʾān, vol.3 p.192, 204</ref> |

|||

The language of the Quran has been described as "rhymed prose" as it partakes of both poetry and prose, however, this description runs the risk of compromising the rhythmic quality of Quranic language, which is certainly more poetic in some parts and more prose-like in others. Rhyme, while found throughout the Quran, is conspicuous in many of the earlier Meccan chapters, in which relatively short verses throw the rhyming words into prominence. The effectiveness of such a form is evident for instance in Chapter 81, and there can be no doubt that these passages impressed the conscience of the hearers. Frequently a change of rhyme from one set of verses to another signals a change in the subject of discussion. Later sections also preserve this form but the style is more expository.<ref name=rippin /><ref>[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=369&letter=K&search=Quran Jewishencyclopedia.com] – Körner, Moses B. Eliezer</ref> |

|||

The Quranic text seems to have no beginning, middle, or end, its nonlinear structure being akin to a web or net.<ref name="Britannica"/> The textual arrangement is sometimes considered to have lack of continuity, absence of any chronological or thematic order and presence of repetition.<ref name=blomm>"The final process of collection and codification of the Quran text was guided by one {{sic|?|hide=y|over-|arching}} principle: God's words must not in any way be distorted or sullied by human intervention. For this reason, no serious attempt, apparently, was made to edit the numerous revelations, organize them into thematic units, or present them in chronological order.... This has given rise in the past to a great deal of criticism by European and American scholars of Islam, who find the Quran disorganized, repetitive and very difficult to read." ''Approaches to the Asian Classics,'' Irene Blomm, William Theodore De Bary, Columbia University Press, 1990, p. 65</ref><ref name=pepys>Samuel Pepys: "One feels it difficult to see how any mortal ever could consider this Quran as a Book written in Heaven, too good for the Earth; as a well-written book, or indeed as a book at all; and not a bewildered rhapsody; written, so far as writing goes, as badly as almost any book ever was!" http://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/display.php?table=review&id=21</ref> [[Michael Sells]], citing the work of the critic [[Norman O. Brown]], acknowledges Brown's observation that the seeming disorganization of Quranic literary expression – its scattered or fragmented mode of composition in Sells's phrase – is in fact a literary device capable of delivering profound effects as if the intensity of the prophetic message were shattering the vehicle of human language in which it was being communicated.<ref name = ApproachQuran>Michael Sells, ''Approaching the Qur'ān'' (White Cloud Press, 1999)</ref><ref>Norman O. Brown, "The Apocalypse of Islam". ''Social Text'' 3:8 (1983–1984)</ref> Sells also addresses the much-discussed repetitiveness of the Quran, seeing this, too, as a literary device. |

|||

A text is self-referential when it speaks about itself and makes reference to itself. According to Stefan Wild the Quran demonstrates this meta-textuality by explaining, classifying, interpreting and justifying the words to be transmitted. Self-referentiality is evident in those passages when the Quran refers to itself as revelation (''tanzil''), remembrance (''dhikr''), news (''naba'''), criterion (''furqan'') in a self-designating manner (explicitly asserting its Divinity, "And this is a blessed Remembrance that We have sent down; so are you now denying it?" (21:50), or in the frequent appearance of the 'Say' tags, when Muhammad is commanded to speak (e.g. "Say: 'God's guidance is the true guidance' ", "Say: 'Would you then dispute with us concerning God?' "). According to Wild the Quran is highly self-referential. The feature is more evident in early Meccan chapters.<ref>{{cite book|last=Wild|first=ed. by Stefan|title=Self-referentiality in the Qur'an|year=2006|publisher=Harrassowitz|location=Wiesbaden|isbn=3447053836}}</ref> |

|||

== Interpretation == |

|||

{{Main|Tafsir}} |

|||

[[File:Tapurian Qur'an (Al-Kusar).PNG|thumb|280px|An early interpretation of Chapter 108 of the Quran]] |

|||

The Quran has sparked a huge body of commentary and explication (''tafsīr''), aimed at explaining the "meanings of the Quranic verses, clarifying their import and finding out their significance".<ref>[http://www.almizan.org/new/introduction.asp?TitleText=Introduction Preface of Al'-Mizan], reference is to [[Allameh Tabatabaei]] {{dead link|date=September 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Tafsir is one of the earliest academic activities of Muslims. According to the Quran, Muhammad was the first person who described the meanings of verses for early Muslims.<ref>{{Cite quran|2|151|style=nosup}}</ref> Other early exegetes included a few [[Companions of Muhammad]], like ʻ[[Ali ibn Abi Talib]], ʻ[[Abdullah ibn Abbas]], ʻ[[Abdullah ibn Umar]] and [[Ubayy ibn Kab|Ubayy ibn Kaʻb]]. Exegesis in those days was confined to the explanation of literary aspects of the verse, the background of its revelation and, occasionally, interpretation of one verse with the help of the other. If the verse was about a historical event, then sometimes a few traditions (''[[hadith]]'') of Muhammad were narrated to make its meaning clear.<ref>[http://www.almizan.org/new/introduction.asp?TitleText=Introduction Tafseer Al-Mizan] {{dead link|date=September 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Because the Quran is spoken in [[classical Arabic]], many of the later converts to Islam (mostly non-Arabs) did not always understand the Quranic Arabic, they did not catch allusions that were clear to early Muslims fluent in Arabic and they were concerned with reconciling apparent conflict of themes in the Quran. Commentators erudite in Arabic explained the allusions, and perhaps most importantly, explained which Quranic verses had been revealed early in Muhammad's prophetic career, as being appropriate to the very earliest Muslim community, and which had been revealed later, canceling out or "[[naskh (exegesis)|abrogating]]" (''nāsikh'') the earlier text (''mansūkh'').<ref>[http://qa.sunnipath.com/issue_view.asp?HD=7&ID=2656&CATE=1 How can there be abrogation in the Quran?]</ref><ref>[http://www.mostmerciful.com/abrogation-and-substitution.htm Are the verses of the Qur'an Abrogated and/or Substituted?]</ref> Other scholars, however, maintain that no abrogation has taken place in the Quran.<ref>{{cite web|last=Islahi|first=Amin Ahsan|title=Abrogation in the Qur’ān|url=http://www.monthly-renaissance.com/issue/content.aspx?id=426|work=Renaissance Journal|accessdate=26 April 2013}}</ref> The [[Ahmadiyya Muslim Community]] has published a 10-volume Urdu commentary on the Quran, with the name ''Tafseer e Kabir''.<ref>[https://ia801704.us.archive.org/3/items/TafseerKabeerMirzaBashiruddinMahmoodAhmad/Tafseer%20%20Kabeer%20Mirza%20%20Bashiruddin%20Mahmood%20Ahmad.pdf Tafsir Kabeer by Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmood Ahmad]</ref> |

|||

=== Esoteric Interpretation === |

|||

{{Main|Esoteric interpretation of the Quran}} |

|||

Esoteric or [[sufism|Sufi]] interpretation attempts to unveil the inner meanings of the Quran. Sufism moves beyond the apparent (''zahir'') point of the verses and instead relates Quranic verses to the inner or esoteric (''batin'') and metaphysical dimensions of consciousness and existence.<ref name=alangodlas>{{cite book|last=Godlas|first=Alan|title=The Blackwell companion to the Qur'an|year=2008|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|isbn=1405188200|pages=350–362|edition=Pbk. ed.}}</ref> According to Sands, esoteric interpretations are more suggestive than declarative, they are 'allusions' (''isharat'') rather than explanations (''tafsir''). They indicate possibilities as much as they demonstrate the insights of each writer.<ref name=kristin>{{cite book|last=Sands|first=Kristin Zahra|title=Sufi commentaries on the Qur'an in classical Islam|year=2006|publisher=Routledge|isbn=0415366852|edition=1. publ., transferred to digital print.}}</ref> |

|||

Sufi interpretation, according to Annabel Keeler, also exemplifies the use of the theme of love, as for instance can seen in Qushayri's interpretation of the Quran. Verse 7:143 of the Quran states: |

|||

:"when Moses came at the time we appointed, and his Lord spoke to him, he said, 'My Lord, show yourself to me! Let me see you! He said, 'you shall not see me but look at that mountain, if it remains standing firm you will see me.' When his Lord revealed Himself to the mountain, He made it crumble. Moses fell down unconscious. When he recovered, he said, 'Glory be to you! I repent to you! I am the first to believe!'" (Quran 7:143) |

|||

Moses, in 7:143, comes the way of those who are in love, he asks for a vision but his desire is denied, he is made to suffer by being commanded to look at other than the Beloved while the mountain is able to see God. The mountain crumbles and Moses faints at the sight of God's manifestation upon the mountain. In Qushayri's words, Moses came like thousands of men who traveled great distances, and there was nothing left to Moses of Moses. In that state of annihilation from himself, Moses was granted the unveiling of the realities. From the Sufi point of view, God is the always the beloved and the wayfarer's longing and suffering lead to realization of the truths.<ref name=keeler>{{cite journal|last=Keeler|first=Annabel|title=Sufi ''tafsir'' as a Mirror: al-Qushayri the murshid in his Lataif al-isharat|journal=Journal of Qur'anic Studies|year=2006|volume=8|issue=1|pages=1–21}}</ref> |

|||

[[Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei]] says that according to the popular explanation among the later exegetes, ''ta'wil'' indicates the particular meaning a verse is directed towards. The meaning of revelation (''[[tanzil]]''), as opposed to ''ta'wil'', is clear in its accordance to the obvious meaning of the words as they were revealed. But this explanation has become so widespread that, at present, it has become the primary meaning of ''ta'wil'', which originally meant "to return" or "the returning place". In Tabatabaei's view, what has been rightly called ''ta'wil'', or hermeneutic interpretation of the Quran, is not concerned simply with the denotation of words. Rather, it is concerned with certain truths and realities that transcend the comprehension of the common run of men; yet it is from these truths and realities that the principles of doctrine and the practical injunctions of the Quran issue forth. Interpretation is not the meaning of the verse—rather it transpires through that meaning, in a special sort of transpiration. There is a spiritual reality—which is the main objective of ordaining a law, or the basic aim in describing a divine attribute—and then there is an actual significance that a Quranic story refers to.<ref name="Ta'wil">[http://almizan.org/new/special/principles.asp Tabataba'I, Tafsir Al-Mizan, The Principles of Interpretation of the Quran] {{dead link|date=September 2011}}</ref><ref name="The Meaning">[http://almizan.org/Discourses/QD21.asp Tabataba'I, Tafsir Al-Mizan, Topic: Decisive and Ambiguous verses and "ta'wil"] {{dead link|date=September 2011}}</ref> |

|||

According to Shia beliefs, those who are firmly rooted in knowledge like the Prophet and the imams know the secrets of the Quran. According to Tabatabaei, the statement "none knows its interpretation except God"(3:7 ) remains valid, without any opposing or qualifying clause. Therefore, so far as this verse is concerned, the knowledge of the Quran's interpretation is reserved for God. But Tabatabaei uses other verses and concludes that those who are purified by God know the interpretation of the Quran to a certain extent.<ref name="The Meaning"/> |

|||

According to [[Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei|Tabatabaei]], there are acceptable and unacceptable esoteric interpretations. Acceptable ''[[ta'wil]]'' refers to the meaning of a verse beyond its literal meaning; rather the implicit meaning, which ultimately is known only to [[God]] and can't be comprehended directly through human thought alone. The verses in question here refer to the human qualities of coming, going, sitting, satisfaction, anger and sorrow, which are apparently attributed to [[God in Islam|God]]. Unacceptable ''ta'wil'' is where one "transfers" the apparent meaning of a verse to a different meaning by means of a proof; this method is not without obvious inconsistencies. Although this unacceptable ''ta'wil'' has gained considerable acceptance, it is incorrect and cannot be applied to the Quranic verses. The correct interpretation is that reality a verse refers to. It is found in all verses, the decisive and the ambiguous alike; it is not a sort of a meaning of the word; it is a fact that is too sublime for words. God has dressed them with words to bring them a bit nearer to our minds; in this respect they are like proverbs that are used to create a picture in the mind, and thus help the hearer to clearly grasp the intended idea.<ref name="The Meaning"/><ref name="Tabatabaee">[http://www.maaref-foundation.com/english/beliefs/quran/05.htm Tabatabaee (1988), pp. 37–45]</ref> |

|||

==== History of Sufi commentaries ==== |

|||

One of the notable authors of esoteric interpretation prior to the 12th century is Sulami (d. 1021 CE) without whose work the majority of very early Sufi commentaries would not have been preserved. Sulami's major commentary is a book named ''haqaiq al-tafsir'' ("Truths of Exegesis") which is a compilation of commentaries of earlier Sufis. From the 11th century onwards several other works appear, including commentaries by Qushayri (d. 1074), Daylami (d. 1193), Shirazi (d. 1209) and Suhrawardi (d. 1234). These works include material from Sulami's books plus the author's contributions. Many works are written in Persian such as the works of Maybudi (d. 1135) ''kash al-asrar'' ("the unveiling of the secrets").<ref name=alangodlas/> [[Rumi]] (d. 1273) wrote a vast amount of mystical poetry in his book ''Mathnawi''. Rumi makes heavy use of the Quran in his poetry, a feature that is sometimes omitted in translations of Rumi's work. A large number of Quranic passages can be found in ''Mathnawi'', which some consider a kind of Sufi interpretation of the Quran. Rumi's book is not exceptional for containing citations from and elaboration on the Quran, however, Rumi does mention Quran more frequently.<ref name=jmojaddedi>{{cite book|last=Mojaddedi|first=Jawid|title=The Blackwell companion to the Qur'an|year=2008|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|isbn=1405188200|pages=363–373|edition=Pbk. ed.}}</ref> Simnani (d. 1336) wrote two influential works of esoteric exegesis on the Quran. He reconciled notions of God's manifestation through and in the physical world with the sentiments of Sunni Islam.<ref name=jelias>{{cite journal|last=Elias|first=Jamal|title=Sufi ''tafsir'' Reconsidered: Exploring the Development of a Genre|journal=Journal of Qur'anic Studies|year=2010|volume=12|pages=41–55}}</ref> Comprehensive Sufi commentaries appears in 18th century such as the work of Ismail Hakki Bursevi (d. 1725). His work ''ruh al-Bayan'' (the Spirit of Elucidation) is a voluminous exegesis. Written in Arabic, it combines the author's own ideas with those of his predecessors (notably Ibn Arabi and Ghazali), all woven together in ''Hafiz'', a Persian poetry form.<ref name=jelias/> |

|||

===Levels of meaning=== |

|||

[[File:Quran rzabasi1.JPG|thumb|9th-century Quran in [[Reza Abbasi Museum]]]] |

|||

Unlike the Salafis and Zahiri, Shias and Sufis as well as some other [[Islamic philosophy|Muslim philosophers]] believe the meaning of the Quran is not restricted to the literal aspect.<ref name="Corbin 1993, p.7">Corbin (1993), p.7</ref> For them, it is an essential idea that the Quran also has inward aspects. [[Henry Corbin]] narrates a ''[[hadith]]'' that goes back to [[Muhammad]]: <blockquote>"The Quran possesses an external appearance and a hidden depth, an exoteric meaning and an esoteric meaning. This esoteric meaning in turn conceals an esoteric meaning (this depth possesses a depth, after the image of the celestial Spheres, which are enclosed within each other). So it goes on for seven esoteric meanings (seven depths of hidden depth)."<ref name="Corbin 1993, p.7"/></blockquote> |

|||

According to this view, it has also become evident that the inner meaning of the Quran does not eradicate or invalidate its outward meaning. Rather, it is like the soul, which gives life to the body.<ref>[http://www.almizan.org/new/special/Aspects.asp Tabatabaee, Tafsir Al-Mizan] {{dead link|date=September 2011}}</ref> Corbin considers the Quran to play a part in [[Islamic philosophy]], because [[gnosiology]] itself goes hand in hand with [[prophet#Islam|prophetology]].<ref>Corbin (1993), p.13</ref> |

|||

Commentaries dealing with the ''[[Zahir (Islam)|zahir]]'' (outward aspects) of the text are called ''tafsir'', and hermeneutic and esoteric commentaries dealing with the ''[[Batin (Islam)|batin]]'' are called ''[[Esoteric interpretation of the Quran|ta'wil]]'' (“interpretation” or “explanation”), which involves taking the text back to its beginning. Commentators with an esoteric slant believe that the ultimate meaning of the Quran is known only to God.<ref name="Britannica"/> In contrast, [[Quranic literalism]], followed by [[Salafis]] and [[Zahiri]]s, is the belief that the Quran should only be taken at its apparent meaning. |

|||

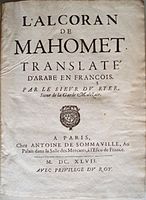

== Translations == |

|||

{{Main|Quran translations}} |

|||

{{See also|List of translations of the Quran}} |

|||

Translation of the Quran has always been a problematic and difficult issue. Many argue that the Quranic text cannot be reproduced in another language or form.<ref name="slate">{{cite web | accessdate=21 November 2008 | url=http://www.slate.com/id/2204849/?from=rss | work=[[Slate (magazine)|Slate]] | last=Aslan | first=Reza | title=How To Read the Quran | date=20 November 2008}}</ref> Furthermore, an Arabic word may have a [[Polysemy|range of meanings]] depending on the context, making an accurate translation even more difficult.<ref name =leaman /> |

|||

Nevertheless, the Quran has been [[translation|translated]] into most African, Asian and European languages.<ref name =leaman /> The first translator of the Quran was [[Salman the Persian]], who translated surat ''[[al-Fatiha]]'' into [[Persian language|Persian]] during the seventh century.<ref>An-Nawawi, Al-Majmu', (Cairo, Matba‘at at-Tadamun n.d.), 380.</ref> Another translation of the Quran was completed in 884 CE in Alwar ([[Sindh]], [[India]] now [[Pakistan]]) by the orders of Abdullah bin Umar bin Abdul Aziz on the request of the Hindu Raja Mehruk.<ref>[http://www.monthlycrescent.com/understanding-the-quran/english-translations-of-the-quran/ Monthlycrescent.com]</ref> |

|||