Salama, Jaffa

Salamah

سلمة Selmeh | |

|---|---|

The mosque in Salamah, now in Kfar Shalem | |

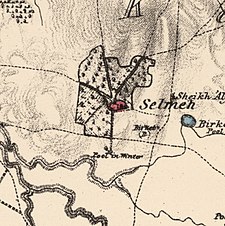

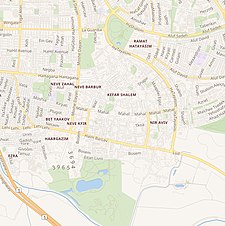

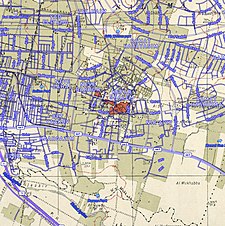

A series of historical maps of the area around Salama, Jaffa (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°02′57″N 34°48′18″E / 32.04917°N 34.80500°E | |

| Palestine grid | 131/161 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Jaffa |

| Date of depopulation | 25 April 1948[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6,782 dunams (6.782 km2 or 2.619 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 6,730[1] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Tel Aviv |

Salamah (Arabic: سلمة) was a Palestinian Arab village, located five kilometers east of Jaffa, that was depopulated in the lead-up to the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The town contains the supposed grave of Salama Abu Hashim, a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. His tomb, two village schools, and ten houses from among the over 800 houses that had made up the village, are all that remain of the structures of the former village today.[3][4]

Etymology

According to modern toponymic analysis, Salamah /Salami/ originally consists of a formation of the semitic root Š-L-M“to yield, pay”, with the Aramaic suffix -ā.[5]

Local tradition ascribes the village name to Salama Abu Hashim.

The historic road from Jaffa to the village is now a street on the border of Tel Aviv and Jaffa, still commonly called "Salameh road".

History

Ottoman era

In 1596, under Ottoman rule, Salamah was a village in the nahiya of Ramla (liwa of Gaza), with a population of 17 Muslim households, an estimated 94 persons. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 25% on agricultural products, including wheat and barley, as well as on other types of property, such as goats and beehives; a total of 1,000 Akçe.[6]

An Ottoman village list of about 1870 showed that Salama had 73 houses and a population of 216, though the population count included only men.[7][8]

In 1882 the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described the village as being built of adobe brick, with a few gardens and wells.[9]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Salameh had a population of 1,187, all Muslims,[10] increasing in the 1931 census to 3,691 inhabitants, still all Muslims, in 800 houses.[11]

An elementary school for boys was opened in 1920, and by 1941 it had 504 boys enrolled. In 1936 an elementary school for girls was opened, which had 121 girls enrolled by 1941.[12]

In the 1945 statistics the population had increased to 6,730, of whom 60 were Christians and 6,670 Muslims.[13][3][14] The total land area was 6,782 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[15] 3,248 dunams were allocated for citrus and bananas, 684 were for plantations and irrigable land, 2,406 for cereals,[16] while 114 dunams were classified as built-up (urban) areas.[17]

1948 War

On 4 December 1947 a band of 120–150 gunmen from Salame attacked nearby kibbutz Ef'al. The residents, together with Palmach reinforcements, beat them off.[18] On 8 December 1947 Arabs attacked the Tel Aviv neighbourhood Hatiqwa. Some of the Jewish residents were killed. Most of the attackers were Salame residents.[19]

In January and February 1948, Palmach raiders destroyed houses in Yazur and Salamah. Their operational orders for Salamah were:

The villagers do not express opposition to the actions of the [Arab] gangs and a great many of the youth even provide [the (Arab) irregulars with] active cooperation ... The aim is ... to attack the northern part of the village ... to cause deaths, to blow up houses and to burn everything possible. A qualification stated: 'Efforts should be made to avoid harming women and children.'[20]

Benny Morris goes on to explain, "The destruction of most of the sites was governed by the cogent military consideration that, should they be left intact, irregulars, or, come the expected invasion, Arab regular troops, would reoccupy and use them as bases for future attacks. An almost instant example of this problem was provided at Qastal in early April."[21]

The village of Salamah finally was depopulated in the weeks leading up to the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, during Haganah's offensive Mivtza Hametz (Operation Hametz) 28–30 April 1948, against a group of villages east of Jaffa. According to the preparatory orders, the objective was to "opening the way [for Jewish forces] to Lydda". Though there was no explicit mention of the prospective treatment of the villagers, the order spoke of "cleansing the area" [tihur hashetah].[22] The final operational order stated: "Civilian inhabitants of places conquered would be permitted to leave after they are searched for weapons." It cautioned against looting and "'undisciplined acts [maasei hefkerut], robbery, or harming holy places.'" Prisoners were to be moved to headquarters.[23]

During 28–30 April, the Haganah took Salamah without a fight, the HIS attributed the non-resistance of the inhabitants to prior Arab defeats and added that "it is clear that the inhabitants have no stomach for war and ... would willingly return to their villages and accept Jewish protection."[24] According to an AP article of 1 May 1948,

Jewish troops moved into Salamah, key Arab position in the Jaffa perimeter, without firing a shot after maneuvering the Arabs into a position where they had no choice but to withdraw.

Streets and houses in Salama were deserted when the Jews arrived.

The Arab troops and the 12,000 civilians there had fled down a narrow escape corridor which the Jews purposely had kept open.[25]

When David Ben-Gurion visited Salamah on 30 April he encountered "only one old blind woman".[26] A day or two later, "hooligans" from Tel Aviv's Hatikva Quarter torched several buildings.[27]

Settlement of the depopulated village with Jewish war refugees, and later by new immigrants, began two weeks after its conquest.[28] On 10 December 1948, Salamah and some of its agricultural land was annexed to Tel Aviv.[28] By this time, half of the population of Salame had been former residents of Tel Aviv who had their homes destroyed during the war; and the other half, new Jewish immigrants.[29] Today the village site is part of the Kfar Shalem neighborhood of Tel Aviv.[4]

See also

- Mustafa al-Hallaj

- Kafr 'Ana

- Depopulated Palestinian locations in Israel

- List of villages depopulated during the Arab–Israeli conflict

- Mount Hope (1853–1858), a nearby farm established by Christians, harassed and attacked by people from Salama

People from Salamah

References

- ^ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 28

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xviii, village #208. Also gives the cause of depopulation.

- ^ a b Khalidi, 1992, pp. 254-5

- ^ a b "Welcome to Salamah". Palestine Remembered. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ^ Marom, Roy; Zadok, Ran (2023). "Early-Ottoman Palestinian Toponymy: A Linguistic Analysis of the (Micro-)Toponyms in Haseki Sultan's Endowment Deed (1552)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 139 (2).

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 154. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 254.

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 160

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 137 noted 70 houses

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p.254. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 254

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jaffa, p. 20

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 15

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 255

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistic, 1945, p. 28

- ^ Village Statistics April 1945, The Palestine Government Archived 2012-06-09 at the Wayback Machine, p. 15

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 53

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 96

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 146

- ^ Morris, 2008, p. 102

- ^ Moshe Naor (21 August 2013). Social Mobilization in the Arab/Israeli War of 1948: On the Israeli Home Front. Routledge. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-1-136-77648-9.

- ^ 12: Battalion OC to platoons, etc., 'Operational Order', undated but from early January 1948, and unsigned, 'Report on Salama Operation', 3 Jan. 1948, both in IDFA (=Israel Defense Forces and Defence Ministry Archive) 922\75\\1213. Quoted in Morris, 2004, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 345

- ^ HGS\Operations to Alexandroni, etc., "Orders for Operation "Hametz", 26 Apr. 1948. IDFA 6647\49\\15. Cited in Morris, 2004, pp. 217, 286

- ^ Operation Hametz HQ to Givati, etc., 27 Apr. 1948, 14:00 hours, IDFA 67\51\\677. See also Alexandroni to battalions, 27 Apr. 1948, IDFA 922\75\\949. Cited in Morris, 2004, pp. 217, 286

- ^ Alexandroni to brigades, etc., 8 May 1948, IDFA 2323\49\\6. Cited in Morris, 2004, pp. 217, 286

- ^ Carter L. Davidson, AP (1 May 1948). "Truce in Effect Temporarily In Jerusalem". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ 372: Entry for 30 Apr. 1948, David Ben-Gurion Yoman Hamilhama (the war diary) II, 377. Quoted in Morris, 2004, p. 217

- ^ 373: Unsigned logbook entry, "2.5.48", HA (=Haganah Archive) 105\94. Quoted in Morris, 2004, p. 217

- ^ a b Arnon Golan (1995), The demarcation of Tel Aviv-Jaffa's municipal boundaries, Planning Perspectives, vol. 10, pp. 383–398.

- ^ "דו"ת ועדת הגבולות | ידיעות עירית תל אביב | 15 ינואר 1949 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית".

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00967-7.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

- Welcome To Salamah

- Salama, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 13: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Salameh from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Salama Archived 2003-11-22 at the Wayback Machine by Rami Nashashibi (1996), Center for Research and Documentation of Palestinian Society.

- A Palestinian Village in the Heart of Tel Aviv?[usurped] by Omer Carmon, 15 August 2005