Ethanol

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Ethanol

| |||

| Other names

Absolute alcohol

Drinking alcohol | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 3DMet | |||

| 1718733 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.526 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 787 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Ethanol | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1170 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C2H6O | |||

| Molar mass | 46.069 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colourless liquid | ||

| Density | 0.789 g cm−3 (at 20 °C) | ||

| Melting point | −114 °C (−173 °F; 159 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 78 °C (172 °F; 351 K) | ||

| miscible | |||

| Acidity (pKa) | 15.9[1] | ||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.36 | ||

| Viscosity | 1.200 mPa s (at 20 °C) | ||

| 1.69 D (gas) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 13 °C (55.4 °F) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Ethanol (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Ethanol, also called ethyl alcohol, pure alcohol, grain alcohol, or drinking alcohol, is a volatile, flammable, colorless liquid. It is a powerful psychoactive drug and one of the oldest recreational drugs. Best known as the type of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages, it is also used in thermometers, as a solvent, and as an alcohol fuel. In common usage, it is often referred to simply as alcohol or spirits.

Ethanol is a straight-chain alcohol, and its molecular formula is C2H5OH. Its empirical formula is C2H6O. An alternative notation is CH3–CH2–OH, which indicates that the carbon of a methyl group (CH3–) is attached to the carbon of a methylene group (–CH2–), which is attached to the oxygen of a hydroxyl group (–OH). It is a constitutional isomer of dimethyl ether. Ethanol is often abbreviated as EtOH, using the common organic chemistry notation of representing the ethyl group (C2H5) with Et.

The fermentation of sugar into ethanol is one of the earliest organic reactions employed by humanity. The intoxicating effects of ethanol consumption have been known since ancient times. In modern times, ethanol intended for industrial use is also produced from by-products of petroleum refining.[2]

Ethanol has widespread use as a solvent of substances intended for human contact or consumption, including scents, flavorings, colorings, and medicines. In chemistry, it is both an essential solvent and a feedstock for the synthesis of other products. It has a long history as a fuel for heat and light, and more recently as a fuel for internal combustion engines.

History

Ethanol has been used by humans since prehistory as the intoxicating ingredient of alcoholic beverages. Dried residue on 9,000-year-old pottery found in China imply that Neolithic people consumed alcoholic beverages.[3]

Although distillation was well known by the early Greeks and Arabs, the first recorded production of alcohol from distilled wine was by the School of Salerno alchemists in the 12th century.[4] The first to mention absolute alcohol, in contrast with alcohol-water mixtures, was Raymond Lull.[4]

In 1796, Johann Tobias Lowitz obtained pure ethanol by filtering distilled ethanol through activated charcoal. Antoine Lavoisier described ethanol as a compound of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, and in 1808 Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure determined ethanol’s chemical formula.[5] Fifty years later, Archibald Scott Couper published ethanol's structural formula. It is one of the first structural formulas determined.[6]

Ethanol was first prepared synthetically in 1826 through the independent efforts of Henry Hennel in Great Britain and S.G. Sérullas in France. In 1828, Michael Faraday prepared ethanol by acid-catalyzed hydration of ethylene, a process similar to current industrial ethanol synthesis.[7]

Ethanol was used as lamp fuel in the United States as early as 1840, but a tax levied on industrial alcohol during the Civil War made this use uneconomical. The tax was repealed in 1906.[8] Original Ford Model T automobiles ran on ethanol until 1908[9] With the advent of Prohibition in 1920, ethanol fuel sellers were accused of being allied with moonshiners,[8] and ethanol fuel fell into disuse until late in the 20th century.

Physical properties

Ethanol is a volatile, colorless liquid that has a slight odor.[10] It burns with a smokeless blue flame that is not always visible in normal light.

The physical properties of ethanol stem primarily from the presence of its hydroxyl group and the shortness of its carbon chain. Ethanol’s hydroxyl group is able to participate in hydrogen bonding, rendering it more viscous and less volatile than less polar organic compounds of similar molecular weight.

Ethanol is a versatile solvent, miscible with water and with many organic solvents, including acetic acid, acetone, benzene, carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, diethyl ether, ethylene glycol, glycerol, nitromethane, pyridine, and toluene.[11][12] It is also miscible with light aliphatic hydrocarbons, such as pentane and hexane, and with aliphatic chlorides such as trichloroethane and tetrachloroethylene.[12]

Ethanol’s miscibility with water contrasts with that of longer-chain alcohols (five or more carbon atoms), whose water miscibility decreases sharply as the number of carbons increases.[13] The miscibility of ethanol with alkanes is limited to alkanes up to undecane, mixtures with dodecane and higher alkanes show a miscibility gap below a certain temperature (about 13 °C for dodecane[14]). The miscibility gap tends to get wider with higher alkanes and the temperature for complete miscibility increases.

Ethanol-water mixtures have less volume than the sum of their individual components at the given fractions. Mixing equal volumes of ethanol and water results in only 1.92 volumes of mixture.[11][15] Mixing ethanol and water is exothermic. At 298 K, up to 777 J/mol[16] are set free.

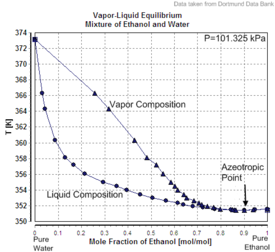

Mixtures of ethanol and water form an azeotrope at about 89 mole-% ethanol and 11 mole-% water[17] or a mixture of about 96 volume percent ethanol and 4% water at normal pressure and T = 351 K. This azeotropic composition is strongly temperature- and pressure-dependent and vanishes at temperatures below 303 K/[18]

|

|

|

| Excess volume of the mixture of ethanol and water (volume contraction) | Heat of mixing of the mixture of ethanol and water | Vapor-liquid equilibrium of the mixture of ethanol and water (including azeotrope) |

|

|

|

| Solid-liquid equilibrium of the mixture of ethanol and water (including eutecticum) | Miscibility gap in the mixture of dodecane and ethanol |

Hydrogen bonding causes pure ethanol to be hygroscopic to the extent that it readily absorbs water from the air. The polar nature of the hydroxyl group causes ethanol to dissolve many ionic compounds, notably sodium and potassium hydroxides, magnesium chloride, calcium chloride, ammonium chloride, ammonium bromide, and sodium bromide.[12] Sodium and potassium chlorides are slightly soluble in ethanol.[12] Because the ethanol molecule also has a nonpolar end, it will also dissolve nonpolar substances, including most essential oils[19] and numerous flavoring, coloring, and medicinal agents.

The addition of even a few percent of ethanol to water sharply reduces the surface tension of water. This property partially explains the “tears of wine” phenomenon. When wine is swirled in a glass, ethanol evaporates quickly from the thin film of wine on the wall of the glass. As the wine’s ethanol content decreases, its surface tension increases and the thin film “beads up” and runs down the glass in channels rather than as a smooth sheet.

Mixtures of ethanol and water that contain more than about 50% ethanol are flammable and easily ignited. Alcoholic proof is a widely used measure of how much ethanol (i.e., alcohol) such a mixture contains. In the 18th century, proof was determined by adding a liquor (such as rum) to gunpowder. If the gunpowder still burned, that was considered to be “100 degrees proof” that it was “good” liquor — hence it was called “100 degrees proof”.

Ethanol-water solutions that contain less than 50% ethanol may also be flammable if the solution is first heated. Some cooking methods call for wine to be added to a hot pan, causing it to flash boil into a vapor, which is then ignited to burn off excess alcohol.

Ethanol is slightly more refractive than water, having a refractive index of 1.36242 (at λ=589.3 nm and 18.35 °C).[11]

Production

Ethanol is produced both as a petrochemical, through the hydration of ethylene, and biologically, by fermenting sugars with yeast.[20] Which process is more economical depends on prevailing prices of petroleum and grain feed stocks.

Ethylene hydration

Ethanol for use as an industrial feedstock or solvent (sometimes referred to as synthetic ethanol) is often made from petrochemical feed stocks, primarily by the acid-catalyzed hydration of ethylene, represented by the chemical equation

- C2H4(g) + H2O(g) → CH3CH2OH(l).

The catalyst is most commonly phosphoric acid,[21] adsorbed onto a porous support such as silica gel or earth. This catalyst was first used for large-scale ethanol production by the Shell Oil Company in 1947.[22] The reaction is carried out with an excess of high pressure steam at 300 °C. In the U.S., this process was used on an industrial scale by Union Carbide Corporation and others; but now only LyondellBasell uses it commercially.

In an older process, first practiced on the industrial scale in 1930 by Union Carbide,[23] but now almost entirely obsolete, ethylene was hydrated indirectly by reacting it with concentrated sulfuric acid to produce ethyl sulfate, which was hydrolysed to yield ethanol and regenerate the sulfuric acid:[24]

- C2H4 + H2SO4 → CH3CH2SO4H

- CH3CH2SO4H + H2O → CH3CH2OH + H2SO4

Fermentation

Ethanol for use in alcoholic beverages, and the vast majority of ethanol for use as fuel, is produced by fermentation. When certain species of yeast (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae) metabolize sugar they produce ethanol and carbon dioxide. The chemical equation below summarizes the conversion:

- C6H12O6 → 2 CH3CH2OH + 2 CO2.

The process of culturing yeast under conditions to produce alcohol is called fermentation. This process is carried out at around 35–40 °C. Ethanol's toxicity to yeast limits the ethanol concentration obtainable by brewing. The most ethanol-tolerant strains of yeast can survive up to approximately 15% ethanol by volume.[25]

To produce ethanol from starchy materials such as cereal grains, the starch must first be converted into sugars. In brewing beer, this has traditionally been accomplished by allowing the grain to germinate, or malt, which produces the enzyme amylase. When the malted grain is mashed, the amylase converts the remaining starches into sugars. For fuel ethanol, the hydrolysis of starch into glucose can be accomplished more rapidly by treatment with dilute sulfuric acid, fungally produced amylase, or some combination of the two.[26]

Cellulosic ethanol

Sugars for ethanol fermentation can be obtained from cellulose.[27][28] Until recently, however, the cost of the cellulase enzymes capable of hydrolyzing cellulose has been prohibitive. The Canadian firm Iogen brought the first cellulose-based ethanol plant on-stream in 2004.[29] Its primary consumer so far has been the Canadian government, which, along with the United States Department of Energy, has invested heavily in the commercialization of cellulosic ethanol. Deployment of this technology could turn a number of cellulose-containing agricultural by-products, such as corncobs, straw, and sawdust, into renewable energy resources. Other enzyme companies are developing genetically engineered fungi that produce large volumes of cellulase, xylanase, and hemicellulase enzymes. These would convert agricultural residues such as corn stover, wheat straw, and sugar cane bagasse and energy crops such as switchgrass into fermentable sugars.[30]

Cellulose-bearing materials typically also contain other polysaccharides, including hemicellulose. When undergoing hydrolysis, hemicellulose decomposes into mostly five-carbon sugars such as xylose. S. cerevisiae, the yeast most commonly used for ethanol production, cannot metabolize xylose. Other yeasts and bacteria are under investigation to ferment xylose and other pentoses into ethanol.[31]

On January 14, 2008, General Motors announced a partnership with Coskata, Inc. The goal is to produce cellulosic ethanol cheaply, with an eventual goal of US$1 per U.S. gallon ($0.30/L) for the fuel. The partnership plans to begin producing the fuel in large quantity by the end of 2008. In June 2009, this goal is still ahead of the firm. By 2011 a full-scale plant will come on line, capable of producing 50 to 100 million gallons of ethanol a year (200–400 ML/a).[32]

Prospective technologies

The anaerobic bacterium Clostridium ljungdahlii, discovered in commercial chicken wastes, can produce ethanol from single-carbon sources including synthesis gas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen that can be generated from the partial combustion of either fossil fuels or biomass. Use of these bacteria to produce ethanol from synthesis gas has progressed to the pilot plant stage at the BRI Energy facility in Fayetteville, Arkansas.[33] The BRI technology has been purchased by INEOS.

Another prospective technology is the closed-loop ethanol plant.[34] Ethanol produced from corn has a number of critics who suggest that it is primarily just recycled fossil fuels because of the energy required to grow the grain and convert it into ethanol. There is also the issue of competition with use of corn for food production. However, the closed-loop ethanol plant attempts to address this criticism. In a closed-loop plant, renewable energy for distillation comes from fermented manure, produced from cattle that have been fed the DDSG by-products from grain ethanol production. The concentrated compost nutrients from manure are then used to fertilize the soil and grow the next crop of grain to start the cycle again. Such a process is expected to lower the fossil fuel consumption used during conversion to ethanol by 75%.[35]

Though in an early stage of research, there is some development of alternative production methods that use feed stocks such as municipal waste or recycled products, rice hulls, sugarcane bagasse, small diameter trees, wood chips, and switchgrass.[36]

Testing

Breweries and biofuel plants employ two methods for measuring ethanol concentration. Infrared ethanol sensors measure the vibrational frequency of dissolved ethanol using the CH band at 2900 cm−1. This method uses a relatively inexpensive solid state sensor that compares the CH band with a reference band to calculate the ethanol content. The calculation makes use of the Beer-Lambert law. Alternatively, by measuring the density of the starting material and the density of the product, using a hydrometer, the change in specific gravity during fermentation indicates the alcohol content. This inexpensive and indirect method has a long history in the beer brewing industry.

Purification

Ethylene hydration or brewing produces an ethanol–water mixture. For most industrial and fuel uses, the ethanol must be purified. Fractional distillation can concentrate ethanol to 95.6% by volume (89.5 mole%). This mixture is an azeotrope with a boiling point of 78.1 °C, and cannot be further purified by distillation.

Common methods for obtaining absolute ethanol include desiccation using adsorbents such as starch, corn grits, or zeolites, which adsorb water preferentially, as well as azeotropic distillation and extractive distillation. Most ethanol fuel refineries use an adsorbent or zeolite to desiccate the ethanol stream.

In another method to obtain absolute alcohol, a small quantity of benzene is added to rectified spirit and the mixture is then distilled. Absolute alcohol is obtained in the third fraction, which distills over at 78.3 °C (351.4 K).[13] Because a small amount of the benzene used remains in the solution, absolute alcohol produced by this method is not suitable for consumption, as benzene is carcinogenic.[37]

There is also an absolute alcohol production process by desiccation using glycerol. Alcohol produced by this method is known as spectroscopic alcohol—so called because the absence of benzene makes it suitable as a solvent in spectroscopy.

Grades of ethanol

Denatured alcohol

Pure ethanol and alcoholic beverages are heavily taxed, but ethanol has many uses that do not involve consumption by humans. To relieve the tax burden on these uses, most jurisdictions waive the tax when an agent has been added to the ethanol to render it unfit to drink. These include bittering agents such as denatonium benzoate and toxins such as methanol, naphtha, and pyridine. Products of this kind are called denatured alcohol.[38][39]

Absolute ethanol

Absolute or anhydrous alcohol refers to ethanol with a low water content. There are various grades with maximum water contents ranging from 1% to ppm levels. Absolute alcohol is not intended for human consumption. It may contain trace amounts of toxic benzene if azeotropic distillation is used to remove water.[40] Absolute ethanol is used as a solvent for laboratory and industrial applications, where water will react with other chemicals, and as fuel alcohol. Spectroscopic ethanol is an absolute ethanol with a low absorbance in ultraviolet and visible light, fit for use as a solvent in ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy.[41]

Pure ethanol is classed as 200 proof in the USA, equivalent to 175 degrees proof in the UK system.[42]

Rectified spirits

Rectified spirit, an azeotropic composition containing 4% water, is used instead of anhydrous ethanol for various purposes. Wine spirits are about 188 proof. The impurities are different from those in 190 proof laboratory ethanol.[43]

Reactions

Ethanol is classified as a primary alcohol, meaning that the carbon its hydroxyl group attaches to has at least two hydrogen atoms attached to it as well. Many ethanol reactions occur at its hydroxyl group.

Ester formation

In the presence of acid catalysts, ethanol reacts with carboxylic acids to produce ethyl esters and water:

- RCOOH + HOCH2CH3 → RCOOCH2CH3 + H2O

This reaction, which is conducted on large scale industrially, requires the removal of the water from the reaction mixture as it is formed. Esters react in the presence of an acid or base to give back the alcohol and carboxylic acid. This reaction is known as saponification because it is used in the preparation of soap. Ethanol can also form esters with inorganic acids. Diethyl sulfate and triethyl phosphate are prepared by treating ethanol with sulfur trioxide and phosphorus pentoxide respectively. Diethyl sulfate is a useful ethylating agent in organic synthesis. Ethyl nitrite, prepared from the reaction of ethanol with sodium nitrite and sulfuric acid, was formerly a widely used diuretic.

Dehydration

Strong acid desiccants cause the dehydration of ethanol to form diethyl ether and other byproducts. If the Temperature of the ethanol being dehydrated exceeds around 160 °C, ethylene will be the main product. Millions of kilograms of diethyl ether are produced annually using sulfuric acid catalyst:

- 2 CH3CH2OH → CH3CH2OCH2CH3 + H2O (on 120 °C)

Combustion

Complete combustion of ethanol forms carbon dioxide and water:

- C2H5OH + 3 O2 → 2 CO2 + 3 H2O(l);(ΔHc = −1371 kJ/mol[44]) specific heat = 2.44 kJ/(kg·K)

Acid-base chemistry

Ethanol is a neutral molecule and the pH of a solution of ethanol in water is nearly 7.00. Ethanol can be quantitatively converted to its conjugate base, the ethoxide ion (CH3CH2O−), by reaction with an alkali metal such as sodium:[13]

- 2 CH3CH2OH + 2 Na → 2 CH3CH2ONa + H2

or a very strong base such as sodium hydride:

- CH3CH2OH + NaH → CH3CH2ONa + H2

The acidity of water and ethanol are nearly the same, as indicated by their pKa of 15.7 and 16 respectively. Thus, sodium ethoxide and sodium hydroxide exist in an equilbrium that is closely balanced:

- CH3CH2OH + NaOH ⇌ CH3CH2ONa + H2O

Halogenation

Ethanol is not used industrially as a precursor to ethyl halides, but the reactions are illustrative. Ethanol reacts with hydrogen halides to produce ethyl halides such as ethyl chloride and ethyl bromide via an sn2 reaction:

- CH3CH2OH + HCl → CH3CH2Cl + H2O

These reactions require a catalyst such as zinc chloride.[24] HBr requires refluxing with a sulfuric acid catalyst.[24] Ethyl halides can, in principle, also be produced by treating ethanol with more specialized halogenating agents, such as thionyl chloride or phosphorus tribromide.[13][24]

- CH3CH2OH + SOCl2 → CH3CH2Cl + SO2 + HCl

Upon treatment with halogens in the presence of base, ethanol gives the corresponding haloform (CHX3, where X = Cl, Br, I). This conversion is called the haloform reaction.[45] " An intermediate in the reaction with chlorine is the aldehyde called chloral:

- 4 Cl2 + CH3CH2OH → CCl3CHO + 5 HCl

Oxidation

Ethanol can be oxidized to acetaldehyde and further oxidized to acetic acid, depending on the reagents and conditions.[24] This oxidation is of no importance industrially, but in the human body, these oxidation reactions are catalyzed by the enzyme liver alcohol dehydrogenase. The oxidation product of ethanol, acetic acid, is a nutrient for humans, being a precursor to acetyl CoA, where the acetyl group can be spent as energy or used for biosynthesis.

Uses

As a fuel

| Energy content of some fuels compared with ethanol:[46] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel type | MJ/L | MJ/kg | Research octane number |

| Dry wood (20% moisture) | ~19.5 | ||

| Methanol | 17.9 | 19.9 | 123 |

| Ethanol | 21.2[47] | 26.8[47] | 113[48] |

| E85 (85% ethanol, 15% gasoline) |

25.2 | 33.2 | 105 |

| Liquefied natural gas | 25.3 | ~55 | |

| Autogas (LPG) (60% propane + 40% butane) |

26.8 | 50. | |

| Aviation gasoline (high-octane gasoline, not jet fuel) |

33.5 | 46.8 | |

| Gasohol (90% gasoline + 10% ethanol) |

33.7 | 47.1 | 93/94 |

| Regular gasoline | 34.8 | [49] 44.4 | min. 91 |

| Premium gasoline | max. 104 | ||

| Diesel | 38.6 | 45.4 | 25 |

| Charcoal, extruded | 50 | 23 | |

The largest single use of ethanol is as a motor fuel and fuel additive. Brazil has the largest national fuel ethanol industry. Gasoline sold in Brazil contains at least 25% anhydrous ethanol. Hydrous ethanol (about 95% ethanol and 5% water) can be used as fuel in more than 90% of new cars sold in the country. Brazilian ethanol is produced from sugar cane and noted for high carbon sequestration.[50] The U.S. uses Gasohol (max 10% ethanol) and E85 (85% ethanol) ethanol/gasoline mixtures.

Ethanol may also be utilized as a rocket fuel, and is currently in lightweight rocket-powered racing aircraft.[51]

Ethanol combustion in an internal combustion engine yields many of the products of incomplete combustion produced by gasoline and significantly larger amounts of formaldehyde and related species such as acetaldehyde.[52] This leads to a significantly larger photochemical reactivity that generates much more ground level ozone.[53] These data have been assembled into The Clean Fuels Report comparison of fuel emissions[54] and show that ethanol exhaust generates 2.14 times as much ozone as does gasoline exhaust. When this is added into the custom Localised Pollution Index (LPI) of The Clean Fuels Report the local pollution (pollution that contributes to smog) is 1.7 on a scale where gasoline is 1.0 and higher numbers signify greater pollution. The California Air Resources Board formalized this issue in 2008 by recognizing control standards for formaldehydes as an emissions control group, much like the conventional NOx and Reactive Organic Gases (ROGs).[55]

World production of ethanol in 2006 was 51 gigalitres (1.3×1010 US gal), with 69% of the world supply coming from Brazil and the United States.[56] More than 20% of Brazilian cars are able to use 100% ethanol as fuel, which includes ethanol-only engines and flex-fuel engines.[57] Flex-fuel engines in Brazil are able to work with all ethanol, all gasoline or any mixture of both. In the US flex-fuel vehicles can run on 0% to 85% ethanol (15% gasoline) since higher ethanol blends are not yet allowed or efficient. Brazil supports this population of ethanol-burning automobiles with large national infrastructure that produces ethanol from domestically grown sugar cane. Sugar cane not only has a greater concentration of sucrose than corn (by about 30%), but is also much easier to extract. The bagasse generated by the process is not wasted, but is used in power plants as a surprisingly efficient fuel to produce electricity.[citation needed]

The United States fuel ethanol industry is based largely on corn. According to the Renewable Fuels Association, as of October 30, 2007, 131 grain ethanol bio-refineries in the United States have the capacity to produce 7.0 billion US gallons (26 GL) of ethanol per year. An additional 72 construction projects underway (in the U.S.) can add 6.4 billion gallons of new capacity in the next 18 months. Over time, it is believed that a material portion of the ≈150 billion gallon per year market for gasoline will begin to be replaced with fuel ethanol.[58]

One problem with ethanol is that because it is easily miscible with water, it cannot be efficiently shipped through modern pipelines, like liquid hydrocarbons, over long distances.[59] Mechanics also have seen increased cases of damage to small engines, particularly the carburetor, attributable to ethanol's increased water retention in fuel over time.[60]

Alcoholic beverages

Ethanol is the principal psychoactive constituent in alcoholic beverages, with depressant effects on the central nervous system. It has a complex mode of action and affects multiple systems in the brain; most notably ethanol acts as an agonist to the GABA receptors.[61] Similar psychoactives include those that also interact with GABA receptors, such as gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB).[62] Ethanol is metabolized by the body as an energy-providing nutrient, as it metabolizes into acetyl CoA, an intermediate common with glucose and fatty acid metabolism, that can be used for energy in the citric acid cycle or for biosynthesis.

Alcoholic beverages vary considerably in ethanol content and in foodstuffs they are produced from. Most alcoholic beverages can be broadly classified as fermented beverages, beverages made by the action of yeast on sugary foodstuffs, or as distilled beverages, beverages whose preparation involves concentrating the ethanol in fermented beverages by distillation. The ethanol content of a beverage is usually measured in terms of the volume fraction of ethanol in the beverage, expressed either as a percentage or in alcoholic proof units.

Fermented beverages can be broadly classified by the foodstuff they are fermented from. Beers are made from cereal grains or other starchy materials, wines and ciders from fruit juices, and meads from honey. Cultures around the world have made fermented beverages from numerous other foodstuffs, and local and national names for various fermented beverages abound.

Distilled beverages are made by distilling fermented beverages. Broad categories of distilled beverages include whiskeys, distilled from fermented cereal grains; brandies, distilled from fermented fruit juices, and rum, distilled from fermented molasses or sugarcane juice. Vodka and similar neutral grain spirits can be distilled from any fermented material (grain or potatoes are most common); these spirits are so thoroughly distilled that no tastes from the particular starting material remain. Numerous other spirits and liqueurs are prepared by infusing flavors from fruits, herbs, and spices into distilled spirits. A traditional example is gin, which is created by infusing juniper berries into a neutral grain alcohol.

In a few beverages, ethanol is concentrated by means other than distillation. Applejack is traditionally made by freeze distillation, by which water is frozen out of fermented apple cider, leaving a more ethanol-rich liquid behind. Ice beer (also known by the German term Eisbier or more specifically as Eisbock) is also freeze-distilled, with beer as the base beverage. Fortified wines are prepared by adding brandy or some other distilled spirit to partially fermented wine. This kills the yeast and conserves some of the sugar in grape juice; such beverages are not only more ethanol-rich, but are often sweeter than other wines.

Alcoholic beverages are sometimes used in cooking, not only for their inherent flavors, but also because the alcohol dissolves hydrophobic flavor compounds, which water cannot.

Just as industrial ethanol is used as feedstock for the production of industrial acetic acid, alcoholic beverages are made into culinary/household vinegar: wine and cider vinegar are both named for their respective source alcohols, while malt vinegar is derived from beer.

Feedstock

Ethanol is an important industrial ingredient and has widespread use as a base chemical for other organic compounds. These include ethyl halides, ethyl esters, diethyl ether, acetic acid, ethyl amines and to a lesser extent butadiene.

Antiseptic

Ethanol is used in medical wipes and in most common antibacterial hand sanitizer gels at a concentration of about 62% v/v as an antiseptic. Ethanol kills organisms by denaturing their proteins and dissolving their lipids and is effective against most bacteria and fungi, and many viruses, but is ineffective against bacterial spores.[63]

Treatment for poisoning by other alcohols

Ethanol is sometimes used to treat poisoning by other, more toxic alcohols, in particular methanol[64] and ethylene glycol. Ethanol competes with other alcohols for the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme, lessening metabolism into toxic aldehyde and carboxylic acid derivatives,[65] and reducing one of the more serious toxic effects of the glycols, their tendency to crystallize in the kidneys.

Solvent

Ethanol is miscible with water and is a good general purpose solvent. It is found in paints, tinctures, markers, and personal care products such as perfumes and deodorants. It may also be used as a solvent in cooking, such as in vodka sauce.

Historical uses

Before the development of modern medicines, ethanol was used for a variety of medical purposes. It has been known to be used as a truth drug (as hinted at by the maxim "in vino veritas"), as medicine for depression and as an anesthetic.[citation needed]

Ethanol was commonly used as fuel in early bipropellant rocket (liquid propelled) vehicles, in conjunction with an oxidizer such as liquid oxygen. The German V-2 rocket of World War II, credited with beginning the space age, used ethanol, mixed with 25% of water to reduce the combustion chamber temperature.[66][67] The V-2's design team helped develop U.S. rockets following World War II, including the ethanol-fueled Redstone rocket, which launched the first U.S. satellite.[68] Alcohols fell into general disuse as more efficient rocket fuels were developed.[67]

Pharmacology

Ethanol binds to acetylcholine, GABA, serotonin, and NMDA receptors.[69]

The removal of ethanol through oxidation by alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver from the human body is limited. Hence the removal of a large concentration of alcohol from blood may follow zero-order kinetics. This means that alcohol leaves the body at a constant rate, rather than having an elimination half-life.

Also, the rate-limiting steps for one substance may be in common with other substances. For instance, the blood alcohol concentration can be used to modify the biochemistry of methanol and ethylene glycol. In this way the oxidation of methanol to the toxic formaldehyde and formic acid in the (human body) can be prevented by giving an appropriate amount of ethanol to a person who has ingested methanol. Note that methanol is very toxic and causes blindness and death. A person who has ingested ethylene glycol can be treated in the same way.

Drug effects

Pure ethanol will irritate the skin and eyes. Nausea, vomiting and intoxication are symptoms of ingestion. Long term use by ingestion can result in serious liver damage.[70] Atmospheric concentrations above one in a thousand are above the European Union Occupational exposure limits.[70]

Short-term

| BAC (g/L) | BAC (% v/v) |

Symptoms[71] |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.05% | Euphoria, talkativeness, relaxation |

| 1 | 0.1 % | Central nervous system depression, nausea, possible vomiting, impaired motor and sensory function, impaired cognition |

| >1.4 | >0.14% | Decreased blood flow to brain |

| 3 | 0.3% | Stupefaction, possible unconsciousness |

| 4 | 0.4% | Possible death |

| >5.5 | >0.55% | Death |

Effects on the central nervous system

Ethanol is a central nervous system depressant and has significant psychoactive effects in sublethal doses; for specifics, see effects of alcohol on the body by dose. Based on its abilities to change the human consciousness, ethanol is considered a psychoactive drug.[72] Death from ethyl alcohol consumption is possible when blood alcohol level reaches 0.4%. A blood level of 0.5% or more is commonly fatal. Levels of even less than 0.1% can cause intoxication, with unconsciousness often occurring at 0.3–0.4%.[73]

The amount of ethanol in the body is typically quantified by blood alcohol content (BAC), which is here taken as weight of ethanol per unit volume of blood. The table at right summarizes the symptoms of ethanol consumption. Small doses of ethanol generally produce euphoria and relaxation; people experiencing these symptoms tend to become talkative and less inhibited, and may exhibit poor judgment. At higher dosages (BAC > 1 g/L), ethanol acts as a central nervous system depressant, producing at progressively higher dosages, impaired sensory and motor function, slowed cognition, stupefaction, unconsciousness, and possible death.

More specifically, ethanol acts in the central nervous system by binding to the GABA-A receptor, increasing the effects of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (i.e. it is a positive allosteric modulator).[74]

Prolonged heavy consumption of alcohol can cause significant permanent damage to the brain and other organs. See Alcohol consumption and health.

In America, about half of the deaths in car accidents occur in alcohol-related crashes.[75] The risk of a fatal car accident increases exponentially with the level of alcohol in the driver's blood.[76] Most drunk driving laws governing the acceptable levels in the blood while driving or operating heavy machinery set typical upper limits of blood alcohol content (BAC) between 0.05% and 0.08%.[citation needed]

Discontinuing consumption of alcohol after several years of heavy drinking can also be fatal. Alcohol withdrawal can cause anxiety, autonomic dysfunction, seizures and hallucinations. Delirium tremens is a condition that requires people with a long history of heavy drinking to undertake an alcohol detoxification regimen.

Effects on metabolism

Ethanol within the human body is converted into acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase and then into acetic acid by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. The product of the first step of this breakdown, acetaldehyde,[77] is more toxic than ethanol. Acetaldehyde is linked to most of the clinical effects of alcohol. It has been shown to increase the risk of developing cirrhosis of the liver,[62] multiple forms of cancer, and alcoholism.

Drug interactions

Ethanol can intensify the sedation caused by other central nervous system depressant drugs such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, opioids, phenothiazines and anti-depressants.[73]

Magnitude of effects

Some individuals have less-effective forms of one or both of the metabolizing enzymes, and can experience more-severe symptoms from ethanol consumption than others. Conversely, those who have acquired alcohol tolerance have a greater quantity of these enzymes, and metabolize ethanol more rapidly.[78]

Long-term

Birth defects

Ethanol is classified as a teratogen. See fetal alcohol syndrome.

Other effects

Frequent drinking of alcoholic beverages has been shown to be a major contributing factor in cases of elevated blood levels of triglycerides.[79]

Ethanol is not a carcinogen.[80][81] However, the first metabolic product of ethanol, acetaldehyde, is toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic.

Natural occurrence

Ethanol is produced naturally from the fermentation of overripe fruit by yeasts.[82] Despite many reports to the contrary, there is little scientific evidence that animals seek out overripe fruit for its intoxicating effects; rather, it suggests that they instead actively avoid doing so.[83] Ethanol is also produced during the germination of many plants as a result of natural anerobiosis.[84] Ethanol has been detected in outer space, forming an icy coating around dust grains in interstellar clouds.[85]

See also

References

- ^ Ballinger, P., Long, F.A., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1960, 82, 795.

- ^ Myers, Richard L.; Myers, Rusty L. (2007). The 100 most important chemical compounds: a reference guide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 122. ISBN 0313337586.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roach, J. (July 18, 2005). "9,000-Year-Old Beer Re-Created From Chinese Recipe". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ^ a b Forbes, Robert James(1948) A short history of the art of distillation, p.89

- ^ Alcohol in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

- ^ Couper AS (1858). "On a new chemical theory" (online reprint). Philosophical magazine. 16 (104–16). Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ^ Hennell, H. (1828). "On the mutual action of sulfuric acid and alcohol, and on the nature of the process by which ether is formed". Philosophical Transactions. 118: 365. doi:10.1098/rstl.1828.0021.

- ^ a b Siegel, Robert (2007-02-15). "Ethanol, Once Bypassed, Now Surging Ahead". NPR. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ DiPardo, Joseph. "Outlook for Biomass Ethanol Production and Demand" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ^ "Odorous Compounds - Odour Descriptions of Chemicals with Odours". Atmospheric Emissions & Odour Laboratory, Centre for Water & Waste Technology, School of Civil & Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales. 24 April 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Lide, D. R., ed. (2000). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 81st edition. CRC press. ISBN 0849304814.

- ^ a b c d Windholz, Martha (1976). The Merck index: an encyclopedia of chemicals and drugs (9th ed.). Rahway, N.J., U.S.A: Merck. ISBN 0-911910-26-3.

- ^ a b c d Morrison, Robert Thornton; Boyd, Robert Neilson (1972). Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon, inc. ISBN 0205084524.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dahlmann U, Schneider GM (1989). "(Liquid + liquid) phase equilibria and critical curves of (ethanol + dodecane or tetradecane or hexadecane or 2,2,4,4,6,8,8-heptamethylnonane) from 0.1 MPa to 120.0 MPa". J Chem Thermodyn. 21: 997. doi:10.1016/0021-9614(89)90160-2.

- ^ "Ethanol". Encyclopedia of chemical technology. Vol. 9. 1991. p. 813.

- ^ Costigan MJ, Hodges LJ, Marsh KN, Stokes RH, Tuxford CW (1980). "The Isothermal Displacement Calorimeter: Design Modifications for Measuring Exothermic Enthalpies of Mixing". Aust. J. Chem. 33 (10): 2103. doi:10.1071/CH9802103.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lei Z, Wang H, Zhou R, Duan Z (2002). "Influence of salt added to solvent on extractive distillation". Chem Eng J. 87: 149. doi:10.1016/S1385-8947(01)00211-X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pemberton RC, Mash CJ (1978). "Thermodynamic properties of aqueous non-electrolyte mixtures II. Vapour pressures and excess Gibbs energies for water + ethanol at 303.15 to 363.15 K determined by an accurate static method". J Chem Thermodyn. 10: 867. doi:10.1016/0021-9614(78)90160-X.

- ^ Merck Index of Chemicals and Drugs, 9th ed.; monographs 6575 through 6669

- ^ Mills, G.A.; Ecklund, E.E. "Mills GA, Ecklund EE (1987). "Alcohols as Components of Transportation Fuels". Annual Review of Energy. 12: 47. doi:10.1146/annurev.eg.12.110187.000403.

- ^ Roberts, John D.; Caserio, Marjorie C. (1977). Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry. W. A. Benjamin, Inc. ISBN 0-8053-8329-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ethanol". Encyclopedia of chemical technology. Vol. 9. 1991. p. 82.

- ^ Lodgsdon, J.E (1991). "Ethanol". In Howe-Grant, Mary; Kirk, Raymond E.; Othmer, Donald F.; Kroschwitz, Jacqueline I. (ed.). Encyclopedia of chemical technology. Vol. 9 (4th ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 817. ISBN 0-471-52669-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Streitweiser, Andrew Jr.; Heathcock, Clayton H. (1976). Introduction to Organic Chemistry. MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-418010-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morais PB, Rosa CA, Linardi VR, Carazza F, Nonato EA (1996). "Production of fuel alcohol by Saccharomyces strains from tropical habitats". Biotechnology Letters. 18: 1351. doi:10.1007/BF00129969.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Badger, P.C. "Ethanol From Cellulose: A General Review." p. 17–21. In: J. Janick and A. Whipkey (eds.), Trends in new crops and new uses. ASHS Press, 2002, Alexandria, VA. Retrieved on September 2, 2007.

- ^ Taherzadeh MJ, Karimi K (2007). "Acid-based hydrolysis processes for ethanol from lignocellulosic materials: A review" (PDF). BioResources. 2: 472.

- ^ Taherzadeh MJ, Karimi K (2007). "Enzymatic-based hydrolysis processes for ethanol from lignocellulosic materials: A review" (PDF). BioResources. 2: 707.

- ^ Ritter SK (2004). "Biomass or Bust". Chemical & Engineering News. 82 (22): 31.

- ^ Clines, Tom (2006). "Brew Better Ethanol". Popular Science Online.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kompala, Dhinakar S. "Maximizing Ethanol Production by Engineered Pentose-Fermenting Zymononas mobilis" (PDF). Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Colorado at Boulder. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ Mick, Jason (2008-01-14). "Cellulosic Ethanol Promises $1 per Gallon Fuel From Waste". DailyTech.com. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ "Providing for a Sustainable Energy Future". Bioengineering Resources, inc. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ "Closed-Loop Ethanol Plant to Start Production". www.renewableenergyaccess.com. November 2, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rapier, R. (June 26, 2006) "E3 Biofuels: Responsible Ethanol" R-Squared Energy Blog

- ^ "Air Pollution Rules Relaxed for U.S. Ethanol Producers". Environmental News Service. April 12, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ^ Snyder R, Kalf GF (1994). "A perspective on benzene leukemogenesis". Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 24 (3): 177. doi:10.3109/10408449409021605. PMID 7945890.

- ^ "U-M Program to Reduce the Consumption of Tax-free Alcohol; Denatured Alcohol a Safer, Less Expensive Alternative" (PDF). University of Michigan. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Great Britain (2005). The Denatured Alcohol Regulations 2005. Statutory Instrument 2005 No. 1524.

- ^ August Bernthsen, Raj K. Bansal A textbook of organic chemistry, (2003) ISBN 81-224-1459-1 p. 402

- ^ Gary D. Christian Analytical chemistry, Vol. 1, Wiley, 2003 ISBN 0-471-21472-8

- ^ Textbook Of Food & Bevrge Mgmt, Tata McGraw-Hill, 2007 ISBN 0-07-065573-1 p. 268

- ^ Ralph E. Kunkee and Maynard A. Amerine (1968). "Sugar and Alcohol Stabilization of Yeast in Sweet Wine". Appl Microbiol. 16 (7): 1067. PMC 547590.

- ^ Frederick D. Rossini (1937). "Heats of Formation of Simple Organic Molecules". Ind. Eng. Chem. 29: 1424. doi:10.1021/ie50336a024.

- ^ Chakrabartty, in Trahanovsky, Oxidation in Organic Chemistry, pp 343–370, Academic Press, New York, 1978

- ^ Appendix B, Transportation Energy Data Book from the Center for Transportation Analysis of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- ^ a b Thomas, George: Template:PDF. Livermore, CA. Sandia National Laboratories. 2000.

- ^ "Ethanol". Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Thomas, George (2000). "Overview of Storage Development DOE Hydrogen Program" (PDF). Sandia National Laboratories. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ Reel, M. (August 19, 2006) "Brazil's Road to Energy Independence", Washington Post.

- ^ Rocket Racing League Unveils New Flying Hot Rod, by Denise Chow, Space.com, 2010-04-26. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ California Air Resources Board, Definition of a Low Emission Motor Vehicle in Compliance with the Mandates of Health and Safety Code Section 39037.05, second release, October 1989

- ^ Lowi, A. and Carter, W.P.L.; A Method for Evaluating the Atmospheric Ozone Impact of Actual Vehicle emissions, S.A.E. Technical Paper, Warrendale, PA; March 1990

- ^ Jones, T.T.M. The Clean Fuels Report: A Quantitative Comparison Of Motor Fuels, Related Pollution and Technologies (2008)

- ^ "Adoption of the airborne toxic control measure to reduce formaldehyde emissions from composite wood products". Retrieved 2009-08-01. [dead link]

- ^ "Renewable Fuels Association Industry Statistics".[dead link]

- ^ "Tecnologia flex atrai estrangeiros". Agência Estado.

- ^ "First Commercial U.S. Cellulosic Ethanol Biorefinery Announced". Renewable Fuels Association. 2006-11-20. Retrieved May 21, 2006. [dead link]

- ^ W. Horn and F. Krupp. Earth: The Sequel: The Race to Reinvent Energy and Stop Global Warming. 2006, 85

- ^ Mechanics see ethanol damaging small engines, msnbc.com, 8 January 2008

- ^ Chastain G (2006). "Alcohol, neurotransmitter systems, and behavior". The Journal of general psychology. 133 (4): 329. doi:10.3200/GENP.133.4.329-335. PMID 17128954.

- ^ a b Dr. Bill Boggan. "Effects of Ethyl Alcohol on Organ Function". Chemases.com. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ McDonnell G, Russell AD (1999). "Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12 (1): 147. PMC 88911. PMID 9880479.

- ^ "Methanol Poisoning". Cambridge University School of Clinical Medicine. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ^ Barceloux DG, Bond GR, Krenzelok EP, Cooper H, Vale JA (2002). "American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 40 (4): 415. doi:10.1081/CLT-120006745. PMID 12216995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ David Darling. "The Internet Encyclopedia of Science: V-2".

- ^ a b Braeunig, Robert A. "Rocket Propellants." (Website). Rocket & Space Technology, 2006. Retrieved on 2007-08-23.

- ^ "A Brief History of Rocketry." NASA Historical Archive, via science.ksc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "The Brain from Top to Bottom – Alcohol (Intermediate, Molecular)". Canadian Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction. McGill University. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ^ a b "Safety data for ethyl alcohol". Msds.chem.ox.ac.uk. 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Pohorecky LA, Brick J (1988). "Pharmacology of ethanol". Pharmacol. Ther. 36 (2–3): 335. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(88)90109-X. PMID 3279433.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Alcohol Use

- ^ a b David A. Yost, MD (2002). "Acute care for alcohol intoxication" (PDF). 112 (6). Postgraduate Medicine Online. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Santhakumar V, Wallner M, Otis TS (2007). "Ethanol acts directly on extrasynaptic subtypes of GABAA receptors to increase tonic inhibition". Alcohol. 41 (3): 211–21. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.04.011. PMC 2040048. PMID 17591544.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hingson R, Winter M (2003). "Epidemiology and consequences of drinking and driving". Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 27 (1): 63. PMID 15301401.

- ^ Naranjo CA, Bremner KE (1993). "Behavioural correlates of alcohol intoxication". Addiction. 88 (1): 25. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02761.x. PMID 8448514.

- ^ Boggan, Bill. "Metabolism of Ethyl Alcohol in the Body". Chemases.com. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Agarwal DP, Goedde HW (1992). "Pharmacogenetics of alcohol metabolism and alcoholism". Pharmacogenetics. 2 (2): 48. doi:10.1097/00008571-199204000-00002. PMID 1302043.

- ^ "Triglycerides". American Heart Association. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ^ "Material Data Safety Sheet" (PDF). Burdick and Jackson. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ Chavez, Pollyanna R.; Wang, Xiang-Dong; Meyer, Jean. "Animal Models for Carcinogenesis and Chemoprevention, abstract #C42: Effects of Chronic Ethanol Intake on Cyclin D1 Levels and Altered Foci in Diethylnitrosamine-initiated Rats" (PDF). USDA. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robert Dudley (2004). "Ethanol, Fruit Ripening, and the Historical Origins of Human Alcoholism in Primate Frugivory" (PDF). Integrative Comparative Biology. pp. 315–323. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ Cynthia Graber (2008). "Fact or Fiction?: Animals Like to Get Drunk". Scientific American. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ Sylva Leblová, Eva Sinecká and Věra Vaníčková (1974). "Pyruvate metabolism in germinating seeds during natural anaerobiosis". Biologia Plantarum. 16 (6): 406–411. doi:10.1007/BF02922229. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ A. Schriver, L. Schriver-Mazzuoli, P. Ehrenfreund and L. d’Hendecourt (2007). "One possible origin of ethanol in interstellar medium: Photochemistry of mixed CO2–C2H6 films at 11 K. A FTIR study". Chemical Physics. 334 (1–3): 128–137. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2007.02.018. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism maintains a database of alcohol-related health effects. ETOH Archival Database (1972–2003) Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Science Database.

- "Alcohol." (1911). In Hugh Chisholm (Ed.) Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition. Online reprint[dead link]

- Boyce, John M., and Pittet Didier. (2003). “Hand Hygiene in Healthcare Settings.” Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia, United States.

- Rene Martinez VitalSensors Technologies LLC. "VS1000A Series In-Line Ethanol Sensors for the Beverage and BioFuel Industry" (PDF).[dead link] Martinez describes the theory and practice of measuring brix on-line in beverages.

- Sci-toys website explanation of US denatured alcohol designations

- Smith, M.G., and M. Snyder. (2005). "Ethanol-induced virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii". American Society for Microbiology meeting. June 5 – June 9. Atlanta.

External links

- International Labour Organization ethanol safety information

- National Pollutant Inventory – Ethanol Fact Sheet

- National Institute of Standards and Technology chemical data on ethanol

- ChEBI – biology related

- Chicago Board of Trade news and market data on ethanol futures

- Calculation of vapor pressure, liquid density, dynamic liquid viscosity, surface tension of ethanol

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Ethanol

- Ethanol History A look into the history of ethanol