Modafinil

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Provigil, Alertec, Modavigil, others |

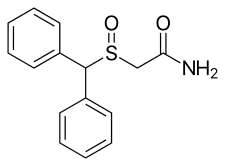

| Other names | CRL-40476; Diphenylmethyl-sulfinylacetamide |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a602016 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Relatively low |

| Addiction liability | Very low to low[1][2] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[3] |

| Drug class | CNS stimulant |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Not determined due to its aqueous insolubility |

| Protein binding | 62.3% |

| Metabolism | Liver (primarily via amide hydrolysis;[8] CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP3A5 involved [9] |

| Elimination half-life | 15 hours (armodafinil), 4 hours (esmodafinil)[7] |

| Excretion | Urine (80%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.168.719 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H15NO2S |

| Molar mass | 273.35 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Modafinil, sold under the brand name Provigil among others, is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant medication used to treat sleepiness due to narcolepsy, shift work sleep disorder, and obstructive sleep apnea.[3][10] While it has seen off-label use as a purported cognitive enhancer to improve wakefulness in animal and human studies, the research on its effectiveness for this use is not conclusive.[11][12][13][14] Modafinil is taken by mouth.[3]

Modafinil’s side effects include headaches, anxiety, excessive adrenal gland overproduction, and nausea. Serious side effects in high doses include delusions, unfounded beliefs, paranoia, irrational thought, and transient depression, possibly due to its effects on dopamine receptors in the brain, as well as allergic reactions. The amount of medication used should be adjusted in those with kidney problems, as this medication has markedly increased side effects during renal insufficiency.[15]

It is not recommended in those with an arrhythmia, significant hypertension, or left ventricular hypertrophy.[15] Modafinil appears to work by acting on dopamine and modulating the areas of the brain involved with the sleep cycle.[3]

Originally developed in the 1970s by French neuroscientist Michel Jouvet and Lafon Laboratories, Modafinil has been prescribed in France since 1994,[16] and was approved for medical use in the United States in 1998.[10] In the United States it is classified as a schedule IV controlled substance, although its classification has been called into question.[17] In the United Kingdom it is a prescription only medication.[15] It is available as a generic medication.[15] In 2019, modafinil was the 336th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 900 thousand prescriptions.[18]

Usage

Uses

Medical

Modafinil is not considered to be a classical psychostimulant, but rather is classified as a eugeroic (wakefulness-promoting drug).

Sleep disorders

Modafinil is used primarily for treatment of narcolepsy, shift work sleep disorder, and excessive daytime sleepiness associated with obstructive sleep apnea.[10][13][19][20] For obstructive sleep apnea, it is recommended that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) be appropriately used before considering starting modafinil to help with daytime sleepiness.[3] Because of the risk for development of skin or hypersensitivity reactions and serious adverse psychiatric reactions, the European Medicines Agency has recommended that new patient prescriptions should be only to treat sleepiness associated with narcolepsy.[21]

Fatigue

Modafinil is suggested for helping with multiple sclerosis (MS) fatigue by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[22] and by MS NGOs.[23][24]

Occupational

Modafinil being of French origin, it was fielded to military personnel in the Air Force, Foreign Legion and Marine infantry during the 1st Gulf War. Being more efficient than its parent drug adrafinil, it was deemed combat-worthy by French Ministry of Defense in 1989 and subsequently administered to personnel by their officers under the name Virgyl, in order to improve a unit's operational tempo. The test took place before the introduction of modafinil as medication, and the personnel involved were not informed of the product's nature.[25]

Since then, armed forces of several countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, India and France, have expressed interest in modafinil as an alternative to amphetamine—the drug traditionally employed in combat situations or lengthy missions where troops face sleep deprivation. The French government indicated that the Foreign Legion used modafinil during certain covert operations.[26] The United Kingdom's Ministry of Defence commissioned research into modafinil[27] from QinetiQ and spent £300,000 on one investigation.[28] In 2011, the Indian Air Force announced that modafinil was included in contingency plans.[29]

In the United States military, modafinil has been approved for use on certain Air Force missions, and it is being investigated for other uses.[30] As of November 2012, modafinil is the only drug approved by the Air Force as a "go pill" for fatigue management (replacing prior use of amphetamine-based medications such as dextroamphetamine).[31] It is also used in various Special Forces.

The Canadian Medical Association Journal also reports that modafinil is used by astronauts on long-term missions aboard the International Space Station. Modafinil is "available to crew to optimize performance while fatigued" and helps with the disruptions in circadian rhythms and with the reduced quality of sleep astronauts experience.[32]

Nootropic

Modafinil has been used non-medically as a "smart drug" by students, office workers, soldiers and transhumanists.[33][34][35][36][37] As a 'smart drug' it allegedly increases mental focus and helps evade sleep, properties which attract students, professionals in the corporate and tech fields, air-force personnel, surgeons, truck drivers and call-center workers.

Treatment of cocaine addiction

Modafinil binds to the dopamine transporter (DAT) in a different conformation than drugs like cocaine and cocaine-like drugs.[38][39] Subjects pre-treated with modafinil report less euphoria from cocaine administration.[39] Modafinil does not potentiate self-administration of cocaine in pretreated Sprague-Dawley rats.[40]

The mechanism by which modafinil inhibits cocaine self-administration is likely more complex than the simple observation that modafinil occupies the DAT, as drugs like methylphenidate (a dopamine re-uptake inhibitor) do not reduce cocaine self-administration.[38]

Available forms

Modafinil is available in the form of 100 and 200 mg oral tablets.[10] It is also available as the (R)-enantiomer, armodafinil, and as a prodrug of modafinil, adrafinil.[41]

Drug tolerance

Large-scale clinical studies have found no evidence of fading impact over time (tolerance) with modafinil at therapeutic doses even with prolonged use (for forty weeks and as long as three years).[42][43][44]

Contraindications

Modafinil is contraindicated in people with known hypersensitivity to modafinil or armodafinil.[45] Modafinil is not approved for use in children for any medical conditions, in whom there is a higher risk of rare but serious dermatological toxicity.[46][47][48]

Adverse effects

The incidence of adverse effects are reported as the following: less than 10% of users report having a headache, nausea, and decreased appetite. Between 5% to 10% of users may be affected with anxiety, insomnia, dizziness, diarrhea, and rhinitis.[49] Modafinil-associated psychiatric reactions have occurred in those with and without a pre-existing psychiatric history.[50] No clinically significant changes in body weight have been observed with modafinil in clinical trials,[51] although decreased appetite and weight loss have been reported with modafinil in children and adolescents probably due to the much higher modafinil exposure in these individuals based on body weight (i.e., mg/kg doses).[52]

Rare occurrences have been reported of more serious adverse effects, including severe skin rashes and other symptoms that are probably allergy-related. From the date of initial marketing, December 1998, to January 30, 2007, the US Food and Drug Administration received six cases of severe cutaneous adverse reactions associated with modafinil, including erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and DRESS syndrome, involving adult and pediatric patients. The FDA issued a relevant alert. In the same alert, the FDA also noted that angioedema and multi-organ hypersensitivity reactions have also been reported in postmarketing experiences.[53] In 2007, the FDA ordered Cephalon to modify the Provigil leaflet in bold-face print of several serious and potentially fatal conditions attributed to modafinil use, including TEN, DRESS syndrome, and SJS.

The long term safety and effectiveness of modafinil have not been determined.[54] However, a recent longitudinal study in pediatric patients for narcolepsy for up to 10 years demonstrated that modafinil and armodafinil were safe and effective with the study concluding that use of modafinil and armodafinil significantly improved patient's ability to stay awake and did not exacerbate preexisting psychiatric conditions.[55]

Addiction and dependence

The addiction and dependence liabilities of modafinil are very low.[1][56] It shares biochemical mechanisms with addictive stimulant drugs, and some studies have reported it to have similar mood-elevating properties, although to a lesser degree.[56] It is not clear whether these effects are any more different than the ones from caffeine.[57][58] Modafinil does not appear to produce euphoric effects nor deviations (i.e. abuse) from assigned dosages to the patient.[59]

Modafinil is classified by the United States FDA as a schedule IV controlled substance, a category for drugs with valid medical uses and low addiction potential.[1][60] The International Narcotics Control Board does not consider modafinil a narcotic[61] nor a psychotropic substance.[62] In fact, modafinil may increase abstinence rates in a subgroup of cocaine addicts while modafinil-related discontinuation adverse effects are no different from placebo.[63]

Overdose

In mice and rats, the median lethal dose (LD50) of modafinil is approximately or slightly greater than 1250 mg/kg. Oral LD50 values reported for rats range from 1000 to 3400 mg/kg. Intravenous LD50 for dogs is 300 mg/kg. Clinical trials on humans involving taking up to 1200 mg/day for 7–21 days and known incidents of acute one-time overdoses up to 4500 mg did not appear to cause life-threatening effects, although a number of adverse experiences were observed, including excitation or agitation, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, aggressiveness, confusion, nervousness, tremor, palpitations, sleep disturbances, nausea, and diarrhea.[10] As of 2004, the FDA is not aware of any fatal overdoses involving modafinil alone (as opposed to multiple drugs including modafinil).[10]

Interactions

Coadministration with opioids such as methadone, hydrocodone, oxycodone and fentanyl may result in a drop in opioid plasma concentrations, because modafinil is an inducer of the CYP3A4 enzymes. If not monitored closely, reduced efficacy or withdrawal symptoms can occur.[64] Modafinil may have an adverse effect on hormonal contraceptives for up to a month after discontinuation.[65] In a 2006 study, a single dose of modafinil 200 mg caused a decrease in blood prolactin levels, although it did not affect human growth hormone or thyroid-stimulating hormone.[66][67] Since modafinil can induce the activity of the CYP3A4 enzyme involved in cortisol clearance,[68] modafinil may reduce the bioavailability of hydrocortisone. Therefore, it may be necessary to adjust the steroid substitution dose in subjects receiving CYP3A4-metabolism-inducing drugs such as modafinil.[69] Modafinil is classified as a weak to moderate inducer of CYP3A4.[70][71]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Potency | Type | Species | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT | 1.8–2.6 μM 4.8 μM 6.4 μM 4.0 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[72][73] [72] [74][75] [72] |

| NET | >10 μM >92 μM 35.6 μM 136 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[72][73] [72] [74][75] [72] |

| SERT | >10 μM 46.6 μM >500 μM >50 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[72][73] [72] [74][75] [72] |

| D2 | >10 μM 16 nMb 120 nMb |

Ki Ki EC50a |

Human Rat Rat |

[72] [76] [76] |

| Footnotes: a = Functional activity, not binding inhibition. b = Armodafinil at D2High. Notes: No activity at a variety of other assessed targets.[72] | ||||

Mechanism of action

As of 2017,[update] the precise therapeutic mechanism of action of modafinil for narcolepsy and sleep-wake disorders remains unknown.[77][78] Modafinil acts as an atypical, selective, and weak dopamine reuptake inhibitor and indirectly activates the release of orexin neuropeptides and histamine from the lateral hypothalamus and tuberomammillary nucleus, respectively all of which may contribute to heightened arousal.[77][78][79][80]

Dopamine reuptake inhibitor

Research found that modafinil elevates dopamine levels in the hypothalamus in animals.[81] The locus of the monoamine action of modafinil was also the target of studies, with effects identified on dopamine in the striatum and, in particular, nucleus accumbens,[82][83] norepinephrine in the hypothalamus and ventrolateral preoptic nucleus,[84][85] and serotonin in the amygdala and frontal cortex.[86] Modafinil was screened at a large panel of receptors and transporters in an attempt to elucidate its pharmacology.[72] Of the sites tested, it was found to significantly affect only the dopamine transporter (DAT), acting as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor (DRI) with an IC50 value of 4 μM.[72] Subsequently, it was determined that modafinil binds to the same site on the DAT as cocaine, but in a different manner.[87][88] In accordance, modafinil increases locomotor activity and extracellular dopamine concentrations in animals in a manner similar to the selective DRI vanoxerine (GBR-12909),[89] and also inhibits methamphetamine-induced dopamine release (a common property of DRIs, since DAT transport facilitates methamphetamine's access to its intracellular targets). As such, "modafinil is an exceptionally weak, but apparently very selective, [DAT] inhibitor".[90] In addition to animal research, a human positron emission tomography (PET) imaging study found that 200 mg and 300 mg doses of modafinil resulted in DAT occupancy of 51.4% and 56.9%, respectively, which was described as "close to that of methylphenidate".[91] Another human PET imaging study similarly found that modafinil occupied the DAT and also determined that it significantly elevated extracellular levels of dopamine in the brain, including in the nucleus accumbens.[92]

Modafinil has been described as an "atypical" DAT inhibitor, and shows a profile of effects that is very different from those of other dopaminergic stimulants.[93][94] For instance, modafinil produces wakefulness reportedly without the need for compensatory sleep, and shows relatively low, if any, potential for abuse.[95][90][93][94] Aside from modafinil, examples of other atypical DAT inhibitors include vanoxerine and benztropine, which have a relatively low abuse potential similar to modafinil.[93] These drugs appear to interact molecularly with the DAT in a distinct way relative to "conventional" DAT blockers such as cocaine and methylphenidate.[88][93] Analogues of modafinil with modafinil-like versus cocaine-like dopamine reuptake inhibition and effects have been synthesized.[96]

Dopamine transporter-independent actions

Against the hypothesis that modafinil exerts its effects by acting as a DRI, tyrosine hydroxylase inhibitors (which deplete dopamine) fail to block the effects of modafinil in animals.[97] In addition, modafinil fails to reverse reserpine-induced akinesia, whereas dextroamphetamine, a dopamine releasing agent (DRA), is able to do so.[98] Moreover, one of the first published structure–activity relationship studies of modafinil found in 2012 that DAT inhibition did not correlate with wakefulness-promoting effects in animals among modafinil analogues.[99] Additionally, a variety of analogues without any significant inhibition of the DAT still produced wakefulness-promoting effects.[99] Furthermore, "[the] neurochemical effects [of modafinil] and anatomical pattern of brain area activation differ from typical psychostimulants and are consistent with its beneficial effects on cognitive performance processes such as attention, learning, and memory".[95] Another study found that modafinil-induced increased locomotor activity in animals was dependent on histamine release and could be abolished by depletion of neuronal histamine, whereas those of methylphenidate were not and could not be.[81] Taken together, although it is established that modafinil is a clinically significant DRI, its full pharmacology remains unclear and may be more complex than this single property—as it may also include DAT-independent actions.[87][95] One such action may be activation of the orexin system.[80][87][95]

In any case, there is nonetheless a good deal of evidence to indicate that modafinil is producing at least a portion of its wakefulness-promoting effects by acting as a DRI, or at least via activation of the dopaminergic system. In support of modafinil acting as a dopaminergic agent, its wakefulness-promoting effects are abolished in DAT knockout mice (although DAT knockout mice show D1 and D2 receptor and norepinephrine compensatory abnormalities that might confound this finding), reduced by both D1 and D2 receptor antagonists (although conflicting reports exist),[98] and completely blocked by simultaneous inactivation of both D1 and D2 receptors.[90] In accordance, modafinil shows full stimulus generalization to other DAT inhibitors including cocaine, methylphenidate, and vanoxerine, and discrimination is blocked by administration of both ecopipam (SCH-39166), a D1 receptor antagonist, and haloperidol, a D2 receptor antagonist.[94] Partial substitution was seen with the DRA dextroamphetamine and the D2 receptor agonist PNU-91356A, as well as with nicotine (which indirectly elevates dopamine levels through activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors).[94]

Modafinil may possess yet an additional mechanism of action. Both modafinil and its metabolite, modafinil sulfone, possess anticonvulsant properties in animals, and modafinil sulfone is nearly as potent as modafinil in producing this effect.[100] However, modafinil sulfone lacks any wakefulness-promoting effects in animals, indicating that a distinct mechanism may be at play in the anticonvulsant effects of both compounds.[100]

Dopamine D2 receptor partial agonist

Armodafinil, the (R)-enantiomer of modafinil, was also subsequently found to act as a D2High receptor partial agonist,[101] with a Ki of 16 nM, an intrinsic activity of 48%, and an EC50 of 120 nM, in rat striatal tissue.[76] Esmodafinil, the (S)-enantiomer of modafinil, is inactive with respect to the D2 receptor.[76] Modafinil has been found to directly inhibit the firing of midbrain dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra of rats via activation of D2 receptors.[102] However, modafinil has also been reported not to interact with the human D2 receptor (Ki = >10 μM).[72]

Dampening of amygdala activity

Although modafinil enhances the efficiency of prefrontal cortical information processing, there is also some human and mouse evidence to suggest that it conversely reduces amygdala activity (both through direct fMRI observation and anxiety questionnaires).[103][104] The amygdala is highly involved in fear processing, and the dampening of its activity reduces perceptions of fear in response to environmental stress.[105] At least one study has documented a statistically significant reduction in fear response in human subjects given 100 mg of modafinil daily for 7 days.[103]

Modafinil's effects on fear processing are unique from classical psychostimulants such as those based on amphetamine (phenethylamines), which can generate fear and anxiety at high doses.[106]

Other actions

An in vitro study predicts that modafinil may induce the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP1A2, CYP3A4, and CYP2B6, as well as may inhibit CYP2C9 and CYP2C19.[9] However, an in-vitro studies find no significant inhibition of CYP2C9.[8][107] It may also induce P-glycoprotein, which may affect drugs transported by P-glycoprotein, such as digoxin.[108]

Pharmacokinetics

Cmax (peak levels) occurs approximately 2 to 3 hours after administration. Food slows absorption, but does not affect the total AUC. In vitro measurements indicate that 60% of modafinil is bound to plasma proteins at clinical concentrations of the drug. This percentage changes very little when the concentration of modafinil is varied.[109]

Renal excretion of unchanged modafinil accounts for less than 10% of an oral dose.[8] The two major circulating metabolites of modafinil are modafinil acid (CRL-40467) and modafinil sulfone (CRL-41056).[110][8] Both of these metabolites have been described as inactive,[111] and neither appear to contribute to the wakefulness-promoting effects of modafinil.[110][8][112] However, modafinil sulfone does appear to possess anticonvulsant effects, a property that it shares with modafinil.[100]

Elimination half-life is generally in the range of 10 to 12 hours, subject to differences in CYP genotypes, liver function and renal function. It is metabolized in the liver, and its inactive metabolite is excreted in the urine. Urinary excretion of the unchanged drug ranges from 0% to as high as 18.7%, depending on various factors.[109]

Chemistry

Enantiomers

Modafinil is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers, armodafinil ((R)-modafinil) and esmodafinil ((S)-modafinil).[75][113]

Detection in body fluids

Modafinil and/or its major metabolite, modafinil acid, may be quantified in plasma, serum or urine to monitor dosage in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to assist in the forensic investigation of a vehicular traffic violation. Instrumental techniques involving gas or liquid chromatography are usually employed for these purposes.[114][115] As of 2011, it is not specifically tested for by common drug screens (except for anti-doping screens) and is unlikely to cause false positives for other chemically unrelated drugs such as substituted amphetamines.[75]

Reagent testing can be used to screen for the presence of modafinil in samples.

| RC | Marquis Reagent | Liebermann | Froehde |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | Yellow/Orange > Brown[116][117] | Darkening Orange[116] | Deep orange/red[117] |

Structural analogues

Many derivatives and structural analogues of modafinil have been synthesized and studied.[96][118][88] Examples of these analogues include adrafinil, CE-123, fladrafinil (CRL-40941; fluorafinil), flmodafinil (CRL-40940; bisfluoromodafinil, lauflumide), and modafinil sulfone (CRL-41056).[119]

History

Modafinil was originally developed in France by neurophysiologist professor Michel Jouvet and Lafon Laboratories. Modafinil originated with the 1970s invention of a series of benzhydryl sulfinyl compounds, including adrafinil, which was first offered as an experimental treatment for narcolepsy in France in 1986.[16] Modafinil is the primary metabolite of adrafinil, lacking the polar -OH group on its terminal amide,[120] and has similar activity to the parent drug but is much more widely used.[citation needed] It has been prescribed in France since 1994 under the name Modiodal,[16] and in the US since 1998 as Provigil.

In 1998, modafinil was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration[121] for the treatment of narcolepsy and in 2003 for shift work sleep disorder and obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea[122] even though caffeine and amphetamine were shown to be more wakefulness promoting on the Stanford Sleepiness Test Score than modafinil.[78]

It was approved for use in the UK in December 2002. Modafinil is marketed in the United States by Cephalon, who originally leased the rights from Lafon, but eventually purchased the company in 2001.

Cephalon began to market armodafinil, the (R)-enantiomer of modafinil, in the United States in 2007. After protracted patent litigation and negotiations (see below), generic versions of modafinil became available in the US in 2012.

Patent protection and litigation

U.S. patent 4,927,855 was issued to Laboratoire L. Lafon on May 22, 1990, covering the chemical compound modafinil. After receiving an interim term extension of 1066 days and pediatric exclusivity of six months, it expired on October 22, 2010. On October 6, 1994, Cephalon filed an additional patent, covering modafinil in the form of particles of defined size. That patent, U.S. patent 5,618,845 was issued on April 8, 1997. It was reissued in 2002 as RE 37,516, which surrendered the 5618845 patent. With pediatric exclusivity, this patent expired on April 6, 2015.[123][124]

On December 24, 2002, anticipating the expiration of exclusive marketing rights, generic drug manufacturers Mylan, Teva, Barr, and Ranbaxy applied to the FDA to market a generic form of modafinil.[125] At least one withdrew its application after early opposition by Cephalon based on the RE 37,516 patent. There is some question of whether a particle size patent is sufficient protection against the manufacture of generics. Pertinent questions include whether modafinil may be modified or manufactured to avoid the granularities specified in the new Cephalon patent, and whether patenting particle size is invalid because particles of appropriate sizes are likely to be obvious to practitioners skilled in the art. However, under United States patent law, a patent is entitled to a legal presumption of validity, meaning that in order to invalidate the patent, much more than "pertinent questions" are required.

As of October 31, 2011, U.S. Reissue Patent No. RE 37,516 has been declared invalid and unenforceable.[126] The District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania ruled that RE 37,516 was invalid because it: (1) was on sale more than one year prior to the date of the application in violation of 35 U.S.C. section 102(b); (2) was actually invented by someone else (the French company Laboratoire L. Lafon); (3) was obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art under 35 U.S.C. section 103(a); and (4) failed the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. section 112.[127] The patent was also found to be unenforceable due to Cephalon's inequitable conduct during patent prosecution.[127]

Cephalon made an agreement with four major generics manufacturers Teva, Barr Pharmaceuticals, Ranbaxy Laboratories, and Watson Pharmaceuticals between 2005 and 2006 to delay sales of generic modafinil in the US until April 2012 by these companies in exchange for upfront and royalty payments.[128] Litigation arising from these agreements is still pending including an FTC suit filed in April 2008.[129] Apotex received regulatory approval in Canada despite a suit from Cephalon's marketing partner in Canada, Shire Pharmaceuticals.[130][131] Cephalon has sued Apotex in the US to prevent it from releasing a genericized armodafinil (Nuvigil).[132] Cephalon's 2011 attempt to merge with Teva was approved by the FTC under a number of conditions, including granting generic US rights to another company;[133] ultimately, Par Pharmaceutical acquired the US modafinil rights as well as some others.[134]

In the United Kingdom, Mylan Inc. received regulatory approval to sell generic modafinil produced by Orchid in January 2010; Cephalon sued to prevent sale, but lost the patent trial in November.[135]

Society and culture

Brand names

Modafinil is sold under a wide variety of brand names worldwide, including Alertec, Alertex, Altasomil, Aspendos, Forcilin, Intensit, Mentix, Modafinil, Modafinilo, Modalert, Modanil, Modasomil, Modvigil, Modiodal, Modiwake, Movigil, Provigil, Resotyl, Stavigile, Vigia, Vigicer, Vigil, Vigimax, Wakelert and Zalux.[136]

Legal status

Australia

In Australia, modafinil is considered to be a Schedule 4 prescription-only medicine or prescription animal remedy.[137] Schedule 4 is defined as "Substances, the use or supply of which should be by or on the order of persons permitted by State or Territory legislation to prescribe and should be available from a pharmacist on prescription."

Canada

In Canada, modafinil is not listed in the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, but it is a Schedule F prescription drug,[138] so it is subject to seizure by Canada Border Services Agency.

China

In mainland China, modafinil is strictly controlled like other stimulants, such as amphetamines and methylphenidate. It has been classified as Class I psychotropic drug,[139] meaning that only doctors who have the right to prescribe narcotics and Class I psychotropic drugs (usually through special examination) can prescribe it for no more than three-day use (or seven-day use for control/extend-release products).[140] The first and only modafinil products was approved in November 2017,[141] but its marketing status in mainland China is still unknown.

Japan

In Japan, modafinil is Schedule I psychotropic drug.[142][143] Cephalon has licensed Alfresa Corporation to produce, and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma to sell modafinil products under the trade name Modiodal in Japan.[144] Also, there have been reported arrests of people who imported modafinil for personal use.[145][146]

Romania

Modafinil is considered a stimulant doping agent and as such is prohibited in sports competitions, in the same category as steroids.[147] Due to new laws passed in 2022, import into the country or selling is considered a felony and can be punished with jail time from 3 years to 7 years.[148] Simple possession for personal use is still punished with just a fine and confiscation.

Russia

In Russia modafinil is Schedule II controlled substance like cocaine and morphine. Possession of few modafinil pills can lead to 3–10 years imprisonment.[149]

Sweden

In Sweden, modafinil is classified as a schedule IV substance and possession is therefore illegal without prescription.[150]

United States

Modafinil is currently[update] classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance under United States federal law; it is illegal to import by anyone other than a DEA-registered importer without a prescription.[151] The Clinton administration issued regulations in 64 FR 4050 effective 27 January 1999 based upon a recommendation of the administration's Assistant Secretary for Health.[152]

However, one may legally bring modafinil into the United States in person from a foreign country, provided that he or she has a prescription for it, and the drug is properly declared at the border crossing. U.S. residents are limited to 50 dosage units (e.g., pills).[153] Under the US Pure Food and Drug Act, drug companies are not allowed to market their drugs for off-label uses (conditions other than those officially approved by the FDA);[154] Cephalon was reprimanded in 2002 by the FDA because its promotional materials were found to be "false, lacking in fair balance, or otherwise misleading".[155] Cephalon pleaded guilty to a criminal violation and paid several fines, including $50 million and $425 million fines to the U.S. government in 2008.[156][157]

Other countries

The following countries do not classify modafinil as a controlled substance:

- In Finland, modafinil is a prescription drug but not listed as a controlled substance.[158]

- In Denmark, modafinil is a prescription drug but not listed as a controlled substance.[159]

- Mexico (Not listed as a controlled substance, in the National Health Law. Can be purchased in pharmacies without prescription.)[160]

- South Africa Schedule V[161]

- United Kingdom (not listed in Misuse of Drugs Act so possession not illegal, but prescription required) [162]

Sports use and issues

The regulation of modafinil as a doping agent has been controversial in the sporting world, with high-profile cases attracting press coverage since several prominent American athletes have tested positive for the substance. Some athletes who were found to have used modafinil protested that the drug was not on the prohibited list at the time of their offenses.[163] However, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) maintains that it was related to already banned substances. The Agency added modafinil to its list of prohibited substances on August 3, 2004, ten days before the start of the 2004 Summer Olympics.

Modafinil has received some publicity in the past when several athletes (such as sprinter Kelli White in 2004, cyclist David Clinger[164] and basketball player Diana Taurasi[165] in 2010, and rower Timothy Grant in 2015[166]) were accused of using it as a performance-enhancing doping agent. Taurasi and another player, Monique Coker, tested at the same lab, were later cleared.[167] It is not clear how widespread this practice is. The BALCO scandal brought to light an as-yet unsubstantiated (but widely published) account of Major League Baseball's all-time leading home-run hitter Barry Bonds' supplemental chemical regimen that included modafinil in addition to anabolic steroids and human growth hormone.[168] Modafinil has been shown to prolong exercise time to exhaustion while performing at 85% of VO2max and also reduces the perception of effort required to maintain this threshold.[169] Modafinil was added to the World Anti-Doping Agency "Prohibited List" in 2004 as a prohibited stimulant (see Modafinil Legal Status).

Research

Psychiatric conditions

Major depression

Modafinil has been studied in the treatment of major depressive disorder.[170][171][172][173][174][175][176][177] In a 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of psychostimulants for depression, modafinil and other stimulants such as methylphenidate and amphetamines improved depression in traditional meta-analysis.[177] However, when subjected to network meta-analysis, modafinil and most other stimulants did not significantly improve depression, with only methylphenidate remaining effective.[177] Modafinil and other stimulants likewise did not improve quality of life in the meta-analysis, although there was evidence for reduced fatigue and sleepiness with modafinil and other stimulants.[177] While significant effectiveness of modafinil for depression has been reported,[171][173][176] reviews and meta-analyses note that the effectiveness of modafinil for depression is limited, the quality of available evidence is low, and more research is needed.[170][172][174][177]

Bipolar depression

Modafinil and armodafinil have been repurposed as adjunctive treatments for acute depression in people with bipolar disorder.[101] A 2021 meta-analysis found that add-on modafinil and armodafinil were more effective than placebo on response to treatment, clinical remission, and reduction in depressive symptoms, with only minor side effects, but the effect sizes are small and the quality of evidence has to be considered low, limiting the clinical relevance of current evidence.[101] Very low rates of mood switch have been observed with modafinil and armodafinil in bipolar disorder.[173]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Modafinil has been studied and reported to be effective in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), with significantly less abuse potential than conventional psychostimulants like methylphenidate and amphetamines.[178][179] In the United States, an application to market modafinil for pediatric ADHD was submitted to the FDA.[52] However, approval was denied due to concerns about rare but serious dermatological toxicity (specifically, the occurrence of Stevens–Johnson syndrome).[52] In any case, modafinil may be used off-label to treat ADHD in both children and adults.[180][178][181] However, evidence of modafinil for treatment of adult ADHD is mixed, and a 2016 systematic review of alternative drug therapies for adult ADHD could not recommend its use in this context.[182] In a large phase 3 clinical trial of modafinil for adult ADHD, modafinil was not effective in improving symptoms and there was a high rate of side effects (86%) and discontinuation (47%).[183] The poor tolerability of modafinil in this study was possibly due to the use of excessively high doses (210–510 mg/day).[183]

Substance dependence

Modafinil has been studied for the treatment of stimulant dependence.[180][52][184][95][63][96][185]

Schizophrenia

Modafinil and armodafinil have been studied as a complement to antipsychotic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia. They have been consistently shown to have no effect on positive symptoms or cognitive performance.[186][187] A 2015 meta-analysis found that modafinil and armodafinil may slightly reduce negative symptoms in people with acute schizophrenia, though it does not appear useful for people with the condition who are stable, with high negative symptom scores.[187] Among medications demonstrated to be effective for reducing negative symptoms in combination with anti-psychotics, modafinil and armodafinil are among the smallest effect sizes.[188]

Cognitive enhancement

A 2015 review of clinical studies of possible nootropic effects in healthy people found: "... whilst most studies employing basic testing paradigms show that modafinil intake enhances executive function, only half show improvements in attention and learning and memory, and a few even report impairments in divergent creative thinking. In contrast, when more complex assessments are used, modafinil appears to consistently engender enhancement of attention, executive functions, and learning. Importantly, we did not observe any preponderances for side effects or mood changes."[13] A 2019 review of studies of a single-dose of modafinil on mental function in healthy, non-sleep deprived people found a statistically significant but small effect and concluded that the drug has limited usefulness as a cognitive enhancer in non-sleep deprived persons.[12] A 2020 review concluded that users' perception that modafinil is an effective cognitive enhancer is not supported by the evidence in healthy non-sleep-deprived adults.[189]

Modafinil has been used off-label in trials with people with symptoms of post-chemotherapy cognitive impairment, also known as "chemobrain", but a 2011 review found that it was no better than placebo.[190] As of 2015 it had been studied for use in multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue, but the resulting evidence was weak and inconclusive.[191]

Post-anesthesia sedation

General anesthesia is required for many surgeries, but there may be lingering fatigue, sedation, and/or drowsiness after surgery has ended that lasts for hours to days. In outpatient settings wherein patients are discharged home after surgery, this sedation, fatigue and occasional dizziness is problematic. As of 2006, modafinil had been tested and reported to be effective in one small (N=34) double-blind randomized controlled trial for this use.[180]

Fatigue

Research on using modafinil to reduce multiple sclerosis (MS) fatigue has been inconclusive.[192][193]

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

However, caution should be exercised in patients who have narcolepsy in comorbidity with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Therefore, there are potential warnings for a class of drugs used to treat narcolepsy. Centrally acting stimulants like modafinil are often considered first-line drugs for narcolepsy. However, modafinil stimulation increases POTS-related autonomic dysfunction and results in tachycardia/arrhythmia side effects in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Sodium oxybate, a metabolite of GABA, is an alternative drug for stimulant-intolerant patients. Therefore, there is a potential for reconsidering the safety and use of stimulants such as modafinil as first-line therapy in patients with cardiac diseases such as POTS and arrhythmias.[194]

References

- ^ a b c Mignot EJ (October 2012). "A practical guide to the therapy of narcolepsy and hypersomnia syndromes". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (4): 739–752. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9. PMC 3480574. PMID 23065655.

Because of the relatively low risk of addiction, modafinil can be more easily prescribed in patients without a clear, biochemically defined central hypersomnia syndrome, and is also easier to stop, if needed. It is also a schedule IV compound.

- ^ Krishnan R, Chary KV (2015). "A rare case modafinil dependence". Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics. 6 (1). J Pharmacol Pharmacotherapy: 49–50. doi:10.4103/0976-500X.149149. PMC 4319252. PMID 25709356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e "Modafinil Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Modafinil Product information". Health Canada. April 25, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ "Provigil- modafinil tablet". DailyMed. November 30, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ "Nuvigil- armodafinil tablet". DailyMed. November 30, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Robertson P, Hellriegel ET (2003). "Clinical pharmacokinetic profile of modafinil". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 42 (2): 123–137. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342020-00002. PMID 12537513. S2CID 1266677.

- ^ a b Robertson P, DeCory HH, Madan A, Parkinson A (June 2000). "In vitro inhibition and induction of human hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes by modafinil". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 28 (6): 664–671. PMID 10820139.

- ^ a b c d e f "Provigil Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. January 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ^ Ballon JS, Feifel D (April 2006). "A systematic review of modafinil: potential clinical uses and mechanisms of action". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (4): 554–566. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0406. PMID 16669720.

- ^ a b Kredlow MA, Keshishian A, Oppenheimer S, Otto MW (2019). "The Efficacy of Modafinil as a Cognitive Enhancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 39 (5): 455–461. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001085. PMID 31433334. S2CID 201119084.

- ^ a b c Battleday RM, Brem AK (November 2015). "Modafinil for cognitive neuroenhancement in healthy non-sleep-deprived subjects: A systematic review". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (11): 1865–1881. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.07.028. PMID 26381811. S2CID 23319688.

- ^ Meulen R, Hall W, Mohammed A (2017). Rethinking Cognitive Enhancement. Oxford University Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780198727392.

- ^ a b c d BNF 74 (74 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. September 2017. p. 468. ISBN 978-0857112989.

- ^ a b c Denis F (2021). "Smart drugs et nootropiques". Socio-anthropologie (43): 97–110. doi:10.4000/socio-anthropologie.8393. ISSN 1276-8707. S2CID 237863162.

- ^ Oberhaus D (November 30, 2016). "Why Can't We All Take Modafinil?". Vice. Vice Media. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ "Modafinil - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Morgenthaler TI, Lee-Chiong T, Alessi C, Friedman L, Aurora RN, Boehlecke B, et al. (November 2007). "Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report". Sleep. 30 (11): 1445–1459. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.11.1445. PMC 2082098. PMID 18041479.

- ^ Zee PC, Attarian H, Videnovic A (February 2013). "Circadian rhythm abnormalities". Continuum. 19 (1 Sleep Disorders): 132–147. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000427209.21177.aa. PMC 3654533. PMID 23385698.

- ^ European Medicines Agency January 27, 2011 Questions and answers on the review of medicines containing Modafinil

- ^ "Overview | Multiple sclerosis in adults: Management | Guidance |". The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). June 22, 2022.

- ^ "Modafinil (Provigil) | MS Trust".

- ^ "Provigil". National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ "Les cobayes de la guerre du Golfe". Le Monde.fr. December 18, 2005.

- ^ Martin R (November 1, 2003). "It's Wake-Up Time". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Wheeler B (October 26, 2006). "BBC report on MoD research into modafinil". BBC News. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ "MoD's secret pep pill to keep forces awake". The Scotsman. February 27, 2005. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ "Pilot pill project". News – City. PuneMirror. February 16, 2011. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ Taylor Jr GP, Keys RE (December 1, 2003). "Modafinil and management of aircrew fatigue" (PDF). United States Department of the Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ "Air Force Special Operations Command Instruction 48–101" (PDF). November 30, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2018.

(sects. 1.7.4), U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command

- ^ Thirsk R, Kuipers A, Mukai C, Williams D (June 2009). "The space-flight environment: the International Space Station and beyond". CMAJ. 180 (12): 1216–1220. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081125. PMC 2691437. PMID 19487390.

- ^ "Super Soldiers? Military Drug New Rage". ABC News. December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Like It or Not, "Smart Drugs" Are Coming to the Office". Harvard Business Review. May 2015.

- ^ Cadwalladr C (February 14, 2015). "Students used to take drugs to get high. Now they take them to get higher grades". The Guardian.

- ^ Talbot M. "Brain Gain". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ Plotz D (August 21, 2003). "Medikamente: 100 Milligramm Arbeitswut". Die Zeit. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Schmitt KC, Reith ME (October 17, 2011). "The atypical stimulant and nootropic modafinil interacts with the dopamine transporter in a different manner than classical cocaine-like inhibitors". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25790. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625790S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025790. PMC 3197159. PMID 22043293.

- ^ a b O'Brien CP (September 2012). "Modafinil-cocaine interactions: clinical implications". Biological Psychiatry. 72 (5): 346. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.004. PMID 22872012. S2CID 39238847.

- ^ Mereu M, Hiranita T, Jordan CJ, Chun LE, Lopez JP, Coggiano MA, et al. (August 2020). "Modafinil potentiates cocaine self-administration by a dopamine-independent mechanism: possible involvement of gap junctions". Neuropsychopharmacology. 45 (9): 1518–1526. doi:10.1038/s41386-020-0680-5. PMC 7360549. PMID 32340023.

- ^ Billiard M, Lubin S (2015). "Modafinil: Development and Use of the Compound". Sleep Medicine. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 541–544. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2089-1_61. ISBN 978-1-4939-2088-4.

- ^ Nasr S, Wendt B, Steiner K (October 2006). "Absence of mood switch with and tolerance to modafinil: a replication study from a large private practice". Journal of Affective Disorders. 95 (1–3): 111–114. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.010. PMID 16737742.

- ^ Mitler MM, Harsh J, Hirshkowitz M, Guilleminault C (July 2000). "Long-term efficacy and safety of modafinil (PROVIGIL((R))) for the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness associated with narcolepsy". Sleep Medicine. 1 (3): 231–243. doi:10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00031-9. PMID 10828434.

- ^ "Randomized trial of modafinil for the treatment of pathological somnolence in narcolepsy. US Modafinil in Narcolepsy Multicenter Study Group". Annals of Neurology. 43 (1): 88–97. January 1998. doi:10.1002/ana.410430115. PMID 9450772. S2CID 9526780.

- ^ "FDA data on Modafinil" (PDF). Accessdata.fda.gov. 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ "FDA Provigil Drug Safety Data" (PDF). Fda.gov. January 2015.

- ^ Sousa A, Dinis-Oliveira RJ (2020). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic of the cognitive enhancer modafinil: Relevant clinical and forensic aspects". Substance Abuse. 41 (2): 155–173. doi:10.1080/08897077.2019.1700584. PMID 31951804. S2CID 210709160.

- ^ Rugino T (June 2007). "A review of modafinil film-coated tablets for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 293–301. PMC 2654790. PMID 19300563.

- ^ Greenblatt K, Adams N (February 2022). "Modafinil". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30285371.

- ^ "Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin 2008" (etext). Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. December 1, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ "Provigil" (PDF). Medication Guide. Cephalon, Inc. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Kumar R (2008). "Approved and investigational uses of modafinil : an evidence-based review". Drugs. 68 (13): 1803–1839. doi:10.2165/00003495-200868130-00003. PMID 18729534. S2CID 38542387.

- ^ "Modafinil (marketed as Provigil): Serious Skin Reactions". Food and Drug Administration. 2007. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ Banerjee D, Vitiello MV, Grunstein RR (October 2004). "Pharmacotherapy for excessive daytime sleepiness". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 8 (5): 339–354. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2004.03.002. PMID 15336235.

- ^ Ivanenko A, Kek L, Grosrenaud J (April 28, 2017). "0954 Long-Term Use of Modafinil and Armodafinil in Pediatric Patients with Narcolepsy". Sleep. 40 (suppl_1): A354–A355. doi:10.1093/sleepj/zsx050.953. ISSN 0161-8105.

- ^ a b "Provigil: Prescribing information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Cephalon, Inc. January 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Kim D (February 22, 2012). "Practical use and risk of modafinil, a novel waking drug". Environmental Health and Toxicology. 27: e2012007. doi:10.5620/eht.2012.27.e2012007. PMC 3286657. PMID 22375280.

- ^ Warot D, Corruble E, Payan C, Weil JS, Puech AJ (1993). "Subjective effects of modafinil, a new central adrenergic stimulant in healthy volunteers: a comparison with amphetamine, caffeine and placebo". European Psychiatry. 8 (4): 201–208. doi:10.1017/S0924933800002923. ISSN 0924-9338. S2CID 151797528.

- ^ O'Brien CP, Dackis CA, Kampman K (June 2006). "Does modafinil produce euphoria?". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (6): 1109. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1109. PMID 16741217.

- ^ Ballon JS, Feifel D (April 2006). "A systematic review of modafinil: Potential clinical uses and mechanisms of action" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (4): 554–566. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0406. PMID 16669720. S2CID 17047074. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2019.

- ^ International Narcotics Control Board (July 2020), Yellow List: List of Narcotic Drugs Under International Control, In accordance with the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961 [Protocol of 25 March 1972 amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961] (59th ed.), Yellow List PDF

- ^ International Narcotics Control Board (July 2020), Green List: List of Psychotropic Substances Under International Control, In accordance with Convention psychotropic substances of 1971 (31st ed.), United Nations Publications, Green List PDF

- ^ a b Sangroula D, Motiwala F, Wagle B, Shah VC, Hagi K, Lippmann S (August 2017). "Modafinil Treatment of Cocaine Dependence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Substance Use & Misuse. 52 (10): 1292–1306. doi:10.1080/10826084.2016.1276597. PMID 28350194. S2CID 4775658.

- ^ "Modafinil drug interactions". Drugs.com. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "MedlinePlus Drug Information: Modafinil". NIH. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS (June 2008). "Modafinil: a review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 1477–1502. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301534. PMID 17712350. S2CID 13752498.

- ^ Samuels ER, Hou RH, Langley RW, Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM (November 2006). "Comparison of pramipexole and modafinil on arousal, autonomic, and endocrine functions in healthy volunteers". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 20 (6). SAGE Publications: 756–770. doi:10.1177/0269881106060770. PMID 16401653. S2CID 8033437.

- ^ Niwa T, Murayama N, Imagawa Y, Yamazaki H (May 2015). "Regioselective hydroxylation of steroid hormones by human cytochromes P450". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 47 (2). Informa UK Limited: 89–110. doi:10.3109/03602532.2015.1011658. PMID 25678418. S2CID 5791536.

- ^ Aquinos BM, García Arabehety J, Canteros TM, de Miguel V, Scibona P, Fainstein-Day P (2021). "[Adrenal crisis associated with modafinil use]". Medicina (in Spanish). 81 (5): 846–849. PMID 34633961.

- ^ "Drug Development and Drug Interactions | Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". FDA. May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Cytochrome P450 3A (including 3A4) inhibitors and inducers". UpToDate.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, et al. (May 2009). "Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 329 (2): 738–746. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.146142. PMC 2672878. PMID 19197004.

- ^ a b c Krief S, Berrebi-Bertrand I, Nagmar I, Giret M, Belliard S, Perrin D, et al. (October 2021). "Pitolisant, a wake-promoting agent devoid of psychostimulant properties: Preclinical comparison with amphetamine, modafinil, and solriamfetol". Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 9 (5): e00855. doi:10.1002/prp2.855. PMC 8381683. PMID 34423920.

- ^ a b c Murillo-Rodríguez E, Barciela Veras A, Barbosa Rocha N, Budde H, Machado S (February 2018). "An Overview of the Clinical Uses, Pharmacology, and Safety of Modafinil". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 9 (2): 151–158. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00374. PMID 29115823.

- ^ a b c d e Loland CJ, Mereu M, Okunola OM, Cao J, Prisinzano TE, Mazier S, et al. (September 2012). "R-modafinil (armodafinil): a unique dopamine uptake inhibitor and potential medication for psychostimulant abuse". Biological Psychiatry. 72 (5): 405–413. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.022. PMC 3413742. PMID 22537794.

- ^ a b c d Seeman P, Guan HC, Hirbec H (August 2009). "Dopamine D2High receptors stimulated by phencyclidines, lysergic acid diethylamide, salvinorin A, and modafinil". Synapse. 63 (8): 698–704. doi:10.1002/syn.20647. PMID 19391150. S2CID 17758902.

- ^ a b Stahl SM (March 2017). "Modafinil". Prescriber's Guide: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology (6th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 491–495. ISBN 9781108228749.

- ^ a b c Gerrard P, Malcolm R (June 2007). "Mechanisms of modafinil: A review of current research". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 349–364. PMC 2654794. PMID 19300566.

- ^ Ishizuka T, Murotani T, Yamatodani A (2012). "Action of modafinil through histaminergic and orexinergic neurons". Sleep Hormones. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 89. pp. 259–78. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-394623-2.00014-7. ISBN 9780123946232. PMID 22640618.

- ^ a b Salerno M, Villano I, Nicolosi D, Longhitano L, Loreto C, Lovino A, et al. (January 2019). "Modafinil and orexin system: interactions and medico-legal considerations". Frontiers in Bioscience. 24 (3): 564–575. doi:10.2741/4736. PMID 30468674. S2CID 53713777.

- ^ a b Ishizuka T, Murakami M, Yamatodani A (January 2008). "Involvement of central histaminergic systems in modafinil-induced but not methylphenidate-induced increases in locomotor activity in rats". European Journal of Pharmacology. 578 (2–3): 209–215. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.009. PMID 17920581.

- ^ Dopheide MM, Morgan RE, Rodvelt KR, Schachtman TR, Miller DK (July 2007). "Modafinil evokes striatal [(3)H]dopamine release and alters the subjective properties of stimulants". European Journal of Pharmacology. 568 (1–3): 112–123. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.03.044. PMID 17477916.

- ^ Murillo-Rodríguez E, Haro R, Palomero-Rivero M, Millán-Aldaco D, Drucker-Colín R (January 2007). "Modafinil enhances extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and increases wakefulness in rats". Behavioural Brain Research. 176 (2): 353–357. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.016. PMID 17098298. S2CID 30192761.

- ^ de Saint Hilaire Z, Orosco M, Rouch C, Blanc G, Nicolaidis S (November 2001). "Variations in extracellular monoamines in the prefrontal cortex and medial hypothalamus after modafinil administration: a microdialysis study in rats". NeuroReport. 12 (16): 3533–3537. doi:10.1097/00001756-200111160-00032. PMID 11733706. S2CID 31726815.

- ^ Gallopin T, Luppi PH, Rambert FA, Frydman A, Fort P (February 2004). "Effect of the wake-promoting agent modafinil on sleep-promoting neurons from the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus: an in vitro pharmacologic study". Sleep. 27 (1): 19–25. PMID 14998233.

- ^ Ferraro L, Fuxe K, Tanganelli S, Tomasini MC, Rambert FA, Antonelli T (April 2002). "Differential enhancement of dialysate serotonin levels in distinct brain regions of the awake rat by modafinil: possible relevance for wakefulness and depression". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 68 (1): 107–112. doi:10.1002/jnr.10196. PMID 11933055. S2CID 43731660.

- ^ a b c Federici M, Latagliata EC, Rizzo FR, Ledonne A, Gu HH, Romigi A, et al. (November 2013). "Electrophysiological and amperometric evidence that modafinil blocks the dopamine uptake transporter to induce behavioral activation". Neuroscience. 252: 118–124. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.071. PMID 23933217. S2CID 7588529.

- ^ a b c Okunola-Bakare OM, Cao J, Kopajtic T, Katz JL, Loland CJ, Shi L, Newman AH (February 2014). "Elucidation of structural elements for selectivity across monoamine transporters: novel 2-[(diphenylmethyl)sulfinyl]acetamide (modafinil) analogues". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 57 (3): 1000–1013. doi:10.1021/jm401754x. PMC 3954497. PMID 24494745.

- ^ Young JW (March 2009). "Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor family contributions to modafinil-induced wakefulness". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (9): 2663–2665. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5843-08.2009. PMC 2697968. PMID 19261860.

- ^ a b c Wisor J (October 2013). "Modafinil as a catecholaminergic agent: empirical evidence and unanswered questions". Frontiers in Neurology. 4: 139. doi:10.3389/fneur.2013.00139. PMC 3791559. PMID 24109471.

- ^ Kim W, Tateno A, Arakawa R, Sakayori T, Ikeda Y, Suzuki H, Okubo Y (May 2014). "In vivo activity of modafinil on dopamine transporter measured with positron emission tomography and [¹⁸F]FE-PE2I". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 17 (5): 697–703. doi:10.1017/S1461145713001612. PMID 24451483.

- ^ Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Logan J, Alexoff D, Zhu W, Telang F, et al. (March 2009). "Effects of modafinil on dopamine and dopamine transporters in the male human brain: clinical implications". JAMA. 301 (11): 1148–1154. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.351. PMC 2696807. PMID 19293415.

- ^ a b c d Reith ME, Blough BE, Hong WC, Jones KT, Schmitt KC, Baumann MH, et al. (February 2015). "Behavioral, biological, and chemical perspectives on atypical agents targeting the dopamine transporter". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 147: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.005. PMC 4297708. PMID 25548026.

- ^ a b c d Quisenberry AJ, Baker LE (December 2015). "Dopaminergic mediation of the discriminative stimulus functions of modafinil in rats". Psychopharmacology. 232 (24): 4411–4419. doi:10.1007/s00213-015-4065-0. PMID 26374456. S2CID 15519396.

- ^ a b c d e Mereu M, Bonci A, Newman AH, Tanda G (October 2013). "The neurobiology of modafinil as an enhancer of cognitive performance and a potential treatment for substance use disorders". Psychopharmacology. 229 (3): 415–434. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3232-4. PMC 3800148. PMID 23934211.

- ^ a b c Tanda G, Hersey M, Hempel B, Xi ZX, Newman AH (February 2021). "Modafinil and its structural analogs as atypical dopamine uptake inhibitors and potential medications for psychostimulant use disorder". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 56: 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2020.07.007. PMC 8247144. PMID 32927246.

- ^ Stickgold R, Walker WP (May 22, 2010). The Neuroscience of Sleep. Academic Press. pp. 191–. ISBN 978-0-12-375722-7.

- ^ a b Simon P, Hémet C, Ramassamy C, Costentin J (December 1995). "Non-amphetaminic mechanism of stimulant locomotor effect of modafinil in mice". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 5 (4): 509–514. doi:10.1016/0924-977x(95)00041-m. PMID 8998404.

- ^ a b Dunn D, Hostetler G, Iqbal M, Marcy VR, Lin YG, Jones B, et al. (June 2012). "Wake promoting agents: search for next generation modafinil, lessons learned: part III". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 22 (11): 3751–3753. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.031. PMID 22546675.

- ^ a b c Chatterjie N, Stables JP, Wang H, Alexander GJ (August 2004). "Anti-narcoleptic agent modafinil and its sulfone: a novel facile synthesis and potential anti-epileptic activity". Neurochemical Research. 29 (8): 1481–1486. doi:10.1023/b:nere.0000029559.20581.1a. PMID 15260124. S2CID 956077.

- ^ a b c Bartoli F, Cavaleri D, Bachi B, Moretti F, Riboldi I, Crocamo C, Carrà G (November 2021). "Repurposed drugs as adjunctive treatments for mania and bipolar depression: A meta-review and critical appraisal of meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 143: 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.018. PMID 34509090. S2CID 237485915.

- ^ Korotkova TM, Klyuch BP, Ponomarenko AA, Lin JS, Haas HL, Sergeeva OA (February 2007). "Modafinil inhibits rat midbrain dopaminergic neurons through D2-like receptors". Neuropharmacology. 52 (2): 626–633. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.09.005. PMID 17070873. S2CID 33713638.

- ^ a b Rasetti R, Mattay VS, Stankevich B, Skjei K, Blasi G, Sambataro F, et al. (September 2010). "Modulatory effects of modafinil on neural circuits regulating emotion and cognition". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (10): 2101–2109. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.83. PMC 3013347. PMID 20555311.

- ^ van Vliet SA, Jongsma MJ, Vanwersch RA, Olivier B, Philippens IH (May 2006). "Behavioral effects of modafinil in marmoset monkeys". Psychopharmacology. 185 (4): 433–440. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0340-4. hdl:1874/19740. PMID 16550386. S2CID 12681062.

- ^ ePainAssist, Team (March 20, 2018). "What Happens If Amygdala Is Damaged?". Epainassist. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Ellinwood EH, Sudilovsky A, Nelson LM (October 1973). "Evolving behavior in the clinical and experimental amphetamine (model) psychosis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 130 (10): 1088–1093. doi:10.1176/ajp.130.10.1088. PMID 4353974.

- ^ Philmore R (March 8, 2013). "Effect of Modafinil at Steady State on the Single-Dose Pharmacokinetic Profile of Warfarin in Healthy Volunteers". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (12): 205–214. doi:10.1177/00912700222011120.

- ^ Zhu HJ, Wang JS, Donovan JL, Jiang Y, Gibson BB, DeVane CL, Markowitz JS (January 2008). "Interactions of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder therapeutic agents with the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein". European Journal of Pharmacology. 578 (2–3): 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.035. PMC 2659508. PMID 17963743.

- ^ a b Gilman A, Goodman LS, Hardman JG, Limbird LE (2001). Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 1984. ISBN 978-0-07-135469-1.

- ^ a b Schwertner HA, Kong SB (March 2005). "Determination of modafinil in plasma and urine by reversed phase high-performance liquid-chromatography". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 37 (3): 475–479. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2004.11.014. PMID 15740906.

- ^ Wong YN, Wang L, Hartman L, Simcoe D, Chen Y, Laughton W, et al. (October 1998). "Comparison of the single-dose pharmacokinetics and tolerability of modafinil and dextroamphetamine administered alone or in combination in healthy male volunteers". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 38 (10): 971–978. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04395.x. PMID 9807980. S2CID 32857213.

- ^ Robertson P, Hellriegel ET, Arora S, Nelson M (January 2002). "Effect of modafinil on the pharmacokinetics of ethinyl estradiol and triazolam in healthy volunteers". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 71 (1): 46–56. doi:10.1067/mcp.2002.121217. PMID 11823757. S2CID 21552865.

- ^ Vetrivelan R, Saper CB, Fuller PM (2014). "Armodafinil-induced wakefulness in animals with ventrolateral preoptic lesions". Nature and Science of Sleep. 6: 57–63. doi:10.2147/NSS.S53132. PMC 4014362. PMID 24833927.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Wong YN, King SP, Laughton WB, McCormick GC, Grebow PE (March 1998). "Single-dose pharmacokinetics of modafinil and methylphenidate given alone or in combination in healthy male volunteers". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 38 (3): 276–282. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04425.x. PMID 9549666. S2CID 26877375.

- ^ Baselt RC (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1152–1153. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ a b Spratley TK, Hayes PA, Geer LC, Cooper SD, McKibben TD (2005). "Analytical Profiles for Five "Designer" Tryptamines" (PDF). Microgram Journal. 3 (1–2): 54–68.

- ^ a b "Modafinil reaction with the Froehde reagent and others". Reagent Tests UK. December 13, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ De Risi C, Ferraro L, Pollini GP, Tanganelli S, Valente F, Veronese AC (December 2008). "Efficient synthesis and biological evaluation of two modafinil analogues". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (23): 9904–9910. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.027. PMID 18954992.

- ^ Napoletano F, Schifano F, Corkery JM, Guirguis A, Arillotta D, Zangani C, Vento A (2020). "The Psychonauts' World of Cognitive Enhancers". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 546796. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.546796. PMC 7516264. PMID 33024436.

- ^ Ballas CA, Kim D, Baldassano CF, Hoeh N (July 2002). "Modafinil: past, present and future". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2 (4): 449–457. doi:10.1586/14737175.2.4.449. PMID 19810941. S2CID 32939239.

- ^ Healy M (May 2, 2013). "Use of wake-up drug modafinil takes off, spurred by untested uses – Los Angeles Times". LA Times. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ Kesselheim AS, Myers JA, Solomon DH, Winkelmayer WC, Levin R, Avorn J (February 21, 2012). Alessi-Severini S (ed.). "The prevalence and cost of unapproved uses of top-selling orphan drugs". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e31894. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731894K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031894. PMC 3283698. PMID 22363762.

- ^ "Cephalon gets six-month Provigil patent extension". Philadelphia Business Journal. March 28, 2006. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ "Details for Patent: RE37516".

- ^ "Prescription Access Litigation (PAL) Project :: Prescription Access Litigation (PAL) Project :: Lawsuits & Settlements :: Current Lawsuits". Prescriptionaccess.org. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ "Document 514 :: APOTEX, INC. v. CEPHALON, INC. et al". Pennsylvania Eastern District Court :: US Federal District Courts Cases :: Justia. October 31, 2010. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ a b "Document 513 :: APOTEX, INC. v. CEPHALON, INC. et al". Pennsylvania Eastern District Court :: US Federal District Courts Cases :: Justia. October 31, 2010. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ "Cephalon Inc., SEC 10K 2008 disclosure". February 23, 2009. pp. 9–10. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ^ "CVS, Rite Aid Sue Cephalon Over Generic Provigil". Bloomberg News. August 21, 2009. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ^ "Canada IP Year in Review 2008". January 1, 2009.

- ^ "Shire v. Canada". Archived from the original on April 24, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ^ "Cephalon Sues Apotex". Zacks.com. August 20, 2010. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ ""U.S. Federal Trade Commission Clears Teva's Acquisition of Cephalon". Business Wire. October 7, 2011. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

Teva will also grant non-exclusive U.S. rights to an undisclosed company to market modafinil tablets, the generic version of Provigil(R), which had annual brand sales in the U.S. of approximately $1.1 billion

- ^ "Par Pharmaceutical Acquires Three Generic Products From Teva Pharmaceuticals". Press Release. PRNewswire. October 18, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ Larson E (November 19, 2010). "Cephalon Loses U.K. Bid to Halt Mylan, Orchid Generic-Drug Sales". bloomberg LP. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "Modafinil – International Brands". Drugs.com. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "Poisons Standard March 2018". Legislation.gov.au. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ "Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (1184 — Modafinil)". Canada Gazette. 140 (20). March 26, 2005. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011.

- ^ "食品药品监管总局 公安部 国家卫生计生委关于公布麻醉药品和精神药品品种目录的通知". China Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ "处方管理办法(原卫生部令第53号)". 中国政府网 (in Chinese).

- ^ "莫达非尼国内获批上市 威尔曼新药拥有量再上台阶". people.cn (in Chinese). December 18, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "List of psychotropics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "モダフィニルの向精神薬への指定". Archived from the original on May 15, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "医疗用医薬品の添付文书情报-モディオダール锭100mg". 独立行政法人 医薬品医疗机器総合机构 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "モダフィニル密輸で逮捕された歯科医師,ダイエットに使用と供述(報道)". Medicallaw.exblog.jp. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ "向精神薬をインドから密輸入した男を逮捕". Hayabusa3.5ch.net. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ "AGENȚIA NAȚIONALĂ ANTI-DOPING" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ "LEGE 219 26/07/2021 - Portal Legislativ".

- ^ "Data" (PDF). base.consultant.ru.

- ^ "Läkemedelsverkets föreskrifter (LVFS 2011:10) om förteckningar över narkotika" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ "Is It Illegal to Obtain Controlled Substances From the Internet?". United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on July 9, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ Justice Department (January 27, 1999). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Modafinil Into Schedule IV". Federal Register: The Daily Journal of the United States Government. A Rule by the Justice Department on 01/27/1999. 64 FR 4050.

- ^ "USC 201 Section 1301.26 Exemptions from import or export requirements for personal medical use". United States Department of Justice. March 24, 1997. Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2007.

- ^ "Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987 (PDMA), PL 100-293". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on February 23, 2008.

- ^ "Letter to Cephalon 01/03/2002". Food and Drug Administration. January 3, 2002. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ Allison J (October 9, 2009). "Class Action Over Cephalon Off-Label Claims Tossed". www.law360.com. Law360.

Cephalon executives have repeatedly said that they do not condone off-label use of Provigil, but in 2002 the company was reprimanded by the FDA for distributing marketing materials that presented the drug as a remedy for tiredness, "decreased activity" and other supposed ailments. In 2008, Cephalon paid $425m and pleaded guilty to a federal criminal charge relating to its promotion of off-label uses for Provigil and two other drugs.

- ^ Zieger A (September 30, 2008). "Cephalon settlement requires physician payments to be disclosed". Fierce Healthcare. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ "Lääkealan turvallisuus- ja kehittämiskeskuksen päätöslääkeluettelosta". Finlex.fi. 2009.

- ^ "Bekendtgørelse om euforiserende stoffer" [Narcotics act]. Retsinformation.dk (in Danish). June 23, 2020.

- ^ "Estupefacientes y Psicotrópicos" [Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances] (in Spanish). Federal Commission for Protection against Health Risks. Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ SA Government (April 10, 2003). "GENERAL REGULATIONS MADE IN TERMS OF THE MEDICINES AND RELATED SUBSTANCES ACT 101 OF 1965, AS AMENDED Government Notice R510 in Government Gazette 24727 dated 10 April 2003. 22A/16/b; states that although import and export is restricted, possession is not illegal providing that a prescription is present" (PDF). Pretoria: SAFLII. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 22, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ MHRA (April 3, 2013). "MHRA license for Modafinil in UK" (PDF). London: MHRA. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ World Anti-Doping Agency (September 5, 2017). "Prohibited List 2018" (PDF). The World Anti-Doping Code: International Standard.

- ^ "Clinger given lifetime ban for second doping infraction". Cycling News. August 14, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Taurasi tested positive for modafinil". The Washington Post. December 25, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ Guardian Sport (November 23, 2015). "British rowers handed two-year bans for taking banned substances". The Guardian.

- ^ Voepel M (February 18, 2011). "Taurasi: 'I've lost 3 months of my career'".

- ^ "Bonds Exposed". Sports Illustrated. March 7, 2006. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ^ Jacobs I, Bell DG (June 2004). "Effects of acute modafinil ingestion on exercise time to exhaustion". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 36 (6): 1078–1082. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000128146.12004.4F. PMID 15179180. S2CID 25400053.

- ^ a b Chang CM, Sato S, Han C (May 2013). "Evidence for the benefits of nonantipsychotic pharmacological augmentation in the treatment of depression". CNS Drugs. 27 (Suppl 1): S21–S27. doi:10.1007/s40263-012-0030-1. PMID 23712796. S2CID 11869030.

- ^ a b Goss AJ, Kaser M, Costafreda SG, Sahakian BJ, Fu CH (November 2013). "Modafinil augmentation therapy in unipolar and bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (11): 1101–1107. doi:10.4088/JCP.13r08560. PMID 24330897.

- ^ a b Abbasowa L, Kessing LV, Vinberg M (December 2013). "Psychostimulants in moderate to severe affective disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 67 (6): 369–382. doi:10.3109/08039488.2012.752035. PMID 23293898. S2CID 25798623.

- ^ a b c Corp SA, Gitlin MJ, Altshuler LL (September 2014). "A review of the use of stimulants and stimulant alternatives in treating bipolar depression and major depressive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 75 (9): 1010–1018. doi:10.4088/JCP.13r08851. PMID 25295426.

- ^ a b Malhi GS, Byrow Y, Bassett D, Boyce P, Hopwood M, Lyndon W, et al. (March 2016). "Stimulants for depression: On the up and up?". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 50 (3): 203–207. doi:10.1177/0004867416634208. PMID 26906078. S2CID 45341424.

- ^ Kleeblatt J, Betzler F, Kilarski LL, Bschor T, Köhler S (May 2017). "Efficacy of off-label augmentation in unipolar depression: A systematic review of the evidence". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (5): 423–441. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.03.003. PMID 28318897. S2CID 3740987.

- ^ a b McIntyre RS, Lee Y, Zhou AJ, Rosenblat JD, Peters EM, Lam RW, et al. (August 2017). "The Efficacy of Psychostimulants in Major Depressive Episodes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 37 (4): 412–418. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000723. PMID 28590365. S2CID 27622964.

- ^ a b c d e Bahji A, Mesbah-Oskui L (September 2021). "Comparative efficacy and safety of stimulant-type medications for depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". Journal of Affective Disorders. 292: 416–423. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.119. PMID 34144366.

- ^ a b Turner D (April 2006). "A review of the use of modafinil for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 6 (4): 455–468. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.4.455. PMID 16623645. S2CID 24293088.

- ^ Wang SM, Han C, Lee SJ, Jun TY, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Pae CU (January 2017). "Modafinil for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 84: 292–300. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.034. PMID 27810669.

- ^ a b c Ballon JS, Feifel D (April 2006). "A systematic review of modafinil: Potential clinical uses and mechanisms of action" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (4): 554–566. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0406. PMID 16669720. S2CID 17047074. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2019.

- ^ Lindsay SE, Gudelsky GA, Heaton PC (October 2006). "Use of modafinil for the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 40 (10): 1829–1833. doi:10.1345/aph.1H024. PMID 16954326. S2CID 37368284.