Yonkers, New York

Yonkers | |

|---|---|

| Corporation of the City of Yonkers | |

| |

| Nickname(s): The Central City, The City of Gracious Living, The City of Seven Hills, The City with Vision, The Sixth Borough, The Terrace City | |

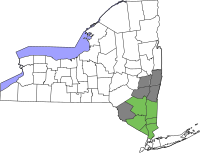

Location within Westchester County | |

Interactive map of Yonkers | |

| Coordinates: 40°56′29″N 73°51′52″W / 40.94139°N 73.86444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Westchester |

| Founded | 1646 (village) |

| Incorporated | 1872 (city) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor-council |

| • Body | Yonkers City Council |

| • Mayor | Mike Spano (D) |

| • City Council | Members' List |

| Area | |

• Total | 20.27 sq mi (52.49 km2) |

| • Land | 18.01 sq mi (46.63 km2) |

| • Water | 2.26 sq mi (5.85 km2) |

| Elevation | 82 ft (25 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 211,569 |

| • Rank | US: 107th NY: 9th |

| • Density | 11,749.92/sq mi (4,536.75/km2) |

| Demonym(s) | Yonkersonian Yonkersite Yonker |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 10701, 10702 (post office), 10703–10705, 10707 (shared with Tuckahoe, NY), 10708 (shared with Bronxville, NY), 10710, 10583 (shared with Scarsdale, NY) |

| Area code | 914 |

| FIPS code | 36-84000[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0971828[3] |

| Website | www.yonkersny.gov |

Yonkers (/ˈjɒŋkərz/[4]) is a city in Westchester County, New York, and a suburb of New York City. Developed along the Hudson River, it is the 9th–most populous incorporated place in New York State. The population of Yonkers was 211,569 as enumerated at the 2020 United States Census, its highest decennial count ever. It is classified as an inner suburb of New York City, located directly to the north of the Bronx and approximately 2.4 miles (4 km) north of Marble Hill, Manhattan, the northernmost point in Manhattan.

Yonkers's downtown is centered on a plaza known as Getty Square, where the municipal government is located. The downtown area also houses significant local businesses and nonprofit organizations. It serves as a major retail hub for Yonkers and the northwest Bronx.

The city is home to several attractions, including access to the Hudson River; Tibbetts Brook Park, with its public pool with slides and lazy river and two-mile walking loop; Untermyer Park; the Hudson River Museum; the Saw Mill River daylighting, wherein a parking lot was removed to uncover the Nepperkamack (Saw Mill River); the Science Barge; and Sherwood House. Yonkers Raceway, a harness racing track, renovated its grounds and clubhouse, and added legalized video slot machine gambling in 2006 to become a "racino" named Empire City. In more recent years, Yonkers has undergone progressive gentrification.[5]

Major shopping areas are located in Getty Square, on South Broadway, at the Cross County Shopping Center and Westchester's Ridge Hill, and along Central Park Avenue, informally called "Central Avenue" by area residents, a name it takes officially a few miles north in White Plains. Yonkers is considered a City of Seven Hills (its hills including Park, Nodine, Ridge, Cross, Locust, Glen, and Church Hills).[6]

History

Early years

The indigenous village of Nappeckamack was located near the Neperah stream (now Saw Mill River) flowed into the Shatemuck (Hudson River).[7] The land on which the city is built was once part of a Dutch 24,000-acre (97-square-kilometer) land grant called Colen Donck. It ran from the current Manhattan-Bronx border at Marble Hill northwards for 12 miles (19 km), and from the Hudson River eastwards to the Bronx River. In July 1645, the area was granted to Adriaen van der Donck, the patroon of Colendonck. Van der Donck was known locally as the Jonkheer — etymologically, "young gentleman", a Dutch honorific title derived from the old Dutch jonk (young) and heer ("lord"); in effect meaning "Esquire". Jonkheer was shortened to Jonker (possessive Jonkers), from which the name "Yonkers" is directly derived.[8] Van der Donck built a saw mill near where the confluence of Nepperhan Creek and the Hudson lies. The Nepperhan is now also known as the Saw Mill River. Van der Donck died in 1655.

Near the site of Van der Donck's mill is Philipse Manor Hall, a Colonial-era manor house owned by Dutch colonists. Today the manor is preserved and operated as a museum and archive, offering many glimpses into life before the American Revolution. The original structure (later enlarged) was built around 1682 by workmen and slaves for Frederick Philipse and his wife Margaret Hardenbroeck de Vries. Philipse was a wealthy Dutchman who by the time of his death had amassed an enormous estate, which encompassed the entire modern City of Yonkers, as well as several other Hudson River towns. Philipse's great-grandson, Frederick Philipse III, was a prominent Loyalist during the American Revolution. He had many economic ties to English businessmen, which also resulted in political ties. Because of his political leanings, he was forced to flee to England. The American colonists in New York state confiscated all the lands and property that belonged to the Philipse family and sold it.

19th century

For its first two centuries, Yonkers was a small farming town producing peaches, apples, potatoes, oats, wheat and other agricultural goods to be shipped to New York City along the Hudson. Water power allowed the creation of new manufacturing jobs only in the 19th century.[9]

Yonkers's growth rested largely on the development of industry. In 1853, Elisha Otis invented the first safety elevator and the Otis Elevator Company opened the first elevator factory in the world on the banks of the Hudson near what is now Vark Street.[10] In the 1880s it relocated to larger quarters (now adapted and used as the Yonkers Public Library). Around the same time, the Alexander Smith and Sons Carpet Company (in the Saw Mill River Valley) expanded to 45 buildings, 800 looms, and more than 4,000 workers. It was known as one of the premier carpet-producing centers in the world.

The Village of Yonkers was incorporated in the western part of the Town of Yonkers in 1854, and the village was incorporated as a city in 1872. In 1873, the southern part of the Town of Yonkers, outside the City of Yonkers, was separated as the Town of Kingsbridge. This included the current neighborhoods of Kingsbridge and Riverdale, as well as Woodlawn Cemetery and Woodlawn Heights. In 1874, the Town of Kingsbridge was annexed by New York City as part of The Bronx. In 1898, Yonkers (along with Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island) voted on a referendum to determine if they wanted to become part of New York City. While the results were positive elsewhere, the returns were so negative in Yonkers and neighboring Mount Vernon that those two areas were not included in the consolidated city and remained independent.[11] Still, some residents call Yonkers "the Sixth Borough", referring to its location on the New York City border, its urban character, and the failed merger vote.[12]

During the American Civil War, 254 Yonkers residents joined the U.S. Army and Navy. They enlisted primarily in four different regiments. These included the 6th New York Heavy Artillery, the 5th New York Volunteer Infantry, the 17th New York Volunteers, and the 15th NY National Guard. During the New York City Draft Riots, Yonkers formed the Home Guards. This force of constables was formed to protect Yonkers from rioting that was feared to spread from New York City, but it never did. In total, seventeen Yonkers residents were killed during the Civil War.[13]

From 1888, the New York City and Northern Railway Company (later the New York Central Railroad) connected Yonkers to Manhattan and points north. A three-mile spur to Getty Square operated until 1943.[14][15]

Aside from being a manufacturing center, Yonkers played a key role in the development of sports recreation in the United States. In 1888, Scottish-born John Reid founded the first golf course in the United States, Saint Andrew's Golf Club, in Yonkers.[16]

20th century

Bakelite, the first completely synthetic plastic, was invented c. 1907 in Yonkers by Leo Baekeland, and manufactured there until the late 1920s.[17] Today, two of the former Alexander Smith and Sons Carpet Company loft buildings located at 540 and 578 Nepperhan Avenue have been repurposed to house the YoHo Artist Community. This collective group of artists works out of private studios there.[18]

During World War I, a total of 6,909 Yonkers residents entered military service. This was approximately seven percent of the population.[19]: vi Most Yonkers men joined either the 27th Division or the 77th Division.[19]: 6 In total, 137 Yonkers residents were killed during the war.[19]: 77 Among the survivors of the USS President Lincoln, a Navy transport ship sunk during the war, were seventeen sailors from Yonkers.[19]: 15

Civilians helped in the war effort by joining organizations such as the American Red Cross. In 1916, there were 126 people in the Yonkers chapter of the Red Cross. By the end of the war, 15,358 Yonkers residents were members of the chapter. Mostly women, they prepared surgical dressings, created hospital garments for the wounded, and knit articles of clothing for refugees and soldiers. Besides joining the Red Cross, residents of Yonkers donated to various war drives. The total amount raised for these drives was $19,255,255.[19]: 23–24

In 1937, a 175-foot water tower collapsed in the Nodine Hills area, injuring 9 people.[20]: 1 : 4–5 The injury toll would later increase by 3 after the collapse, bringing the total number of injuries to 12.[21]: 1 Around 100,000 gallons of water from the tower was spilled, causing flooding in the area and crushing cars and damaging homes. Construction began on the new tower in 1938, and it opened a year later in 1939.[22]

Early in the 20th century, Yonkers also hosted a brass era automobile maker, Colt Runabout Company.[23]: 63 Although the vehicle reportedly performed well, the company went under. Yonkers was the headquarters of the Waring Hat Company, at the time the nation's largest hat manufacturer. During World War II, the city's factories were converted to produce items for the war effort, such as tents and blankets by the Alexander Smith and Sons Carpet Factory, and tanks by the Otis Elevator factory. After World War II, however, increased competition from less expensive imports resulted in a decline in manufacturing in Yonkers, and numerous industrial jobs were lost. The Alexander Smith Carpet Company, one of the city's largest employers, ceased operation during a labor dispute in June 1954.[24]

In 1983, the Otis Elevator Factory finally closed its doors.[25] With the loss of such jobs, Yonkers became primarily a residential city. Some neighborhoods, such as Crestwood and Park Hill, became popular with wealthy New Yorkers who wished to live outside Manhattan without giving up urban conveniences. Yonkers's excellent transportation infrastructure, including three commuter railroad lines (now two: the Harlem and Hudson Lines), and five parkways and thruways, made it a desirable city in which to live. It is a 15-minute drive from Manhattan and has numerous prewar homes and apartment buildings. Yonkers's manufacturing sector has also shown a resurgence in the early 21st century.

On January 4, 1940, Yonkers resident Edwin Howard Armstrong transmitted the first FM radio broadcast (on station W2XCR) from the Yonkers home of C.R. Runyon, a co-experimenter. Yonkers had the longest running pirate radio station, owned by Allan Weiner, which operated during the 1970s through the 1980s.[26][27]

In 1942, a short subway connection was planned between Getty Square and the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, which terminates in Riverdale at 242nd Street slightly south of the city line. The plan was dropped.[28][29]

In 1960, the Census Bureau reported Yonkers's population as 95.8% white and 4.0% black.[30] The city's struggles with racial discrimination and segregation were highlighted in a decades-long federal lawsuit. After a 1985 decision and an unsuccessful appeal, Yonkers's schools were integrated in 1988.[31] Federal judge Leonard B. Sand ruled that Yonkers had engaged in institutional segregation in housing and school policies for over 40 years. He tied the illegal concentration of public housing and private housing discrimination to the city's resistance to ending racial isolation in its public schools.[32]

In the 1980s and 1990s, Yonkers developed a national reputation for racial tension, based on a long-term battle between the city and the NAACP over the building of subsidized low-income housing projects in the city. The city planned to use federal funding for urban renewal efforts within Downtown Yonkers exclusively; other groups, led by the NAACP, believed that the resulting concentration of low-income housing in traditionally poor neighborhoods would perpetuate poverty. Although the City of Yonkers had been warned in 1971 by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development against further building of low-income housing in west Yonkers, it continued to support subsidized housing in this area between 1972 and 1977.[33]

Yonkers gained national/international attention during the summer of 1988, when it backed out of its previous agreement to build promised municipal public housing in the eastern portions of the city, an agreement it had made in a consent decree after losing an appeal in 1987. After its reversal, the city was found in contempt of the federal courts. Judge Sand imposed a fine on Yonkers which started at $100 and doubled every day, capped at $1 million per day by an appeals court,[34] until the city capitulated to the federally mandated plan.

Yonkers remained in contempt of court until September 9, 1988. The City Council relented in the wake of having to close the library and cutback on sanitation measures because of paying the fines. It also was considering having to make massive city layoffs which would have adversely affected its ability to provide services to the upper classes it was trying to retain. First-term mayor Nicholas C. Wasicsko fought to save the city from financial disaster and bring about unity. Yonkers's youngest mayor (elected at age 28), Wasicsko struggled in city politics. His term was stigmatized as the "Balkanization of Yonkers". He succeeded in helping to end the city's contempt of the courts, but was voted out of office as a result. His story is the subject of a miniseries called Show Me a Hero, which aired on HBO in 2015. It was adapted from the 1999 nonfiction book of the same name by former New York Times writer, Lisa Belkin.[35]

A Kawasaki railroad cars assembly plant opened in 1986 in the former Otis plant. It produces the new R142A, R143, R160B, and R188 cars for the New York City Subway, and the PA4 and PA5 series for PATH.

21st century

In the 2000s, some areas of Yonkers that border similar neighborhoods in Riverdale, Bronx began seeing an influx of Orthodox Jews. Subsequently, Riverdale Hatzalah Volunteer Ambulance Service began serving some neighborhoods in the southwest section of the city.[36] There is also a small Jewish cemetery, the Sherwood Park Cemetery.[37]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the city opened several test sites at the ParkCare Pavilion of St. John's Riverside Hospital, which was seen as a COVID-19 hotspot in the city.[38] The test site was operated by the New York State Department of Health during the pandemic.[39] In 2021, more test sites opened in the city as students prepared to return to school for in-person learning.[40]

In February 2023, the Yonkers City Council approved the US Post Office on Main Street for Local Landmark status after being listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1989.[41]

On September 29, 2023, a state of emergency was declared in the city after flash flooding affected most of the Hudson Valley and New York City. Most of the parkways in the area were closed and flooding was reported in the Mount Vernon area of the city.[42] Following the floodings, crews pumped water out of homes.[43]

Geography

The city is spread out over hills rising from near sea level at the eastern bank of the Hudson River to 416 feet (127 m) at Sacred Heart Church, whose spire can be seen from Long Island, New York City, and New Jersey.

The city occupies 20.3 square miles (53 km2), including 18.1 square miles (47 km2) of land and 2.2 square miles (5.7 km2) (11.02%) of water, according to the United States Census Bureau. The Bronx River separates Yonkers from Mount Vernon, Tuckahoe, Eastchester, Bronxville, and Scarsdale to the east. The town of Greenburgh is to the north, and the Hudson River forms the western border.

On the south, Yonkers borders the Riverdale, Woodlawn, and Wakefield sections of The Bronx. In addition, the southernmost point of Yonkers is 2 miles (3 kilometres) north of the northernmost point of Manhattan when measured from Broadway & Caryl Avenue in Yonkers to Broadway & West 228th Street in the Marble Hill section of Manhattan.

Much of the city developed around the Saw Mill River. This enters Yonkers from the north and flows into the Hudson River in the Getty Square neighborhood. Portions of the Saw Mill River that were earlier buried in flumes beneath parking lots are being uncovered, or "daylighted". This promotes the restoration of habitat for plants, fish and other fauna, as well as an understanding of where the Native Americans camped in Spring and Summer months.

The gentilic for residents is alternately Yonkersonian, Yonkersite, or Yonk.[44]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 8,218 | — | |

| 1870 | 12,733 | 54.9% | |

| 1880 | 18,892 | 48.4% | |

| 1890 | 32,033 | 69.6% | |

| 1900 | 47,931 | 49.6% | |

| 1910 | 79,803 | 66.5% | |

| 1920 | 100,176 | 25.5% | |

| 1930 | 134,646 | 34.4% | |

| 1940 | 142,598 | 5.9% | |

| 1950 | 152,798 | 7.2% | |

| 1960 | 190,634 | 24.8% | |

| 1970 | 204,297 | 7.2% | |

| 1980 | 195,351 | −4.4% | |

| 1990 | 188,082 | −3.7% | |

| 2000 | 196,086 | 4.3% | |

| 2010 | 195,976 | −0.1% | |

| 2020 | 211,569 | 8.0% | |

| Historical sources: 1790–1990[45][46] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2010[47] | 1990[30] | 1970[30] | 1950[30] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 55.8% | 76.2% | 92.9% | 96.7% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 41.4% | 67.1% | 89.9% | N/A |

| Black or African American | 16.0% | 14.1% | 6.4% | 3.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 34.7% | 16.7% | 3.5% | N/A |

| Asian | 5.8% | 3.0% | 0.4% | — |

According to the American Community Survey in 2018, 34.8% spoke Spanish. 4.2% of the population was West Indian. Yonkers has a sizeable Arab population, mainly from the Levant, especially Jordanians and Palestinians.[48][49] There is a sizeable Albanian population in Yonkers.[50][51]

As of the 2010 census,[52] there were 195,976 people in the city. The population density was 10,827.4 people per square mile (4,180.5 people/km2). There were 80,839 housing units at an average density of 4,466.2 per square mile (1,724.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 55.8% White, 18.7% African American, 0.7% Native American, 5.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 14.7% from other races, and 4.1% from two or more races. 34.7% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any racial background. Non-Hispanic Whites were 41.4% of the population in 2010,[47] down from 89.9% in 1970.[30]

Neighborhoods

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) |

Though Yonkers contains many small residential enclaves and communities, it can conveniently be divided into four quarters, demarcated by the Saw Mill River. There are 37 or more distinct neighborhoods, though many of these names are rarely used today except by older residents and real-estate brokers.

Northeast Yonkers

Northeast Yonkers is a primarily Irish-American and Italian-American area. House sizes vary widely, from small houses set close together, to larger homes in areas like Lawrence Park West and mid-rise apartment buildings along Central Avenue (NY 100). Central Avenue (officially named Central Park Avenue) provides an abundance of shopping for Yonkers residents. Notable former residents include Steven Tyler (born Steven Tallarico) of the rock band Aerosmith, whose childhood home was located at 100 Pembrook Drive.[53]

Northeast Yonkers contains the upscale neighborhoods of Crestwood, Colonial Heights, and Cedar Knolls, as well as the wealthy enclaves of Beech Hill and Lawrence Park West. It also contains a gated community off the eastern edge of the Grassy Sprain Reservoir known as Winchester Villages. Landmarks include St Vladimir's Seminary, as well as Sarah Lawrence College, and the Tanglewood Shopping Center (one-time home of The Tanglewood Boys gang). Northeast Yonkers is somewhat more expensive than the rest of the city, and due to the proximity of several Metro-North commuter railroad stations, its residents tend to be employed in corporate positions in Manhattan.

Northwest Yonkers

Northwest Yonkers is a collection of widely varying neighborhoods, spanning from the Hudson River to around the New York State Thruway/I-87 and from Ashburton Avenue north to the Hastings-on-Hudson border. With the Hudson River bordering it to the west, this area has many Victorian-era homes with panoramic views of the Palisades. An interest in historic preservation has taken hold in this area in recent years,[when?] as demonstrated on streets like Shonnard Terrace, Delavan Terrace, and Hudson Terrace.

Neighborhoods include Nepera Park, Runyon Heights, Homefield, Glenwood, and Greystone. Landmarks include the Hudson River Museum, the Lenoir Nature Preserve, and the nationally recognized Untermyer Park and Gardens. In fact, Untermyer Park and Gardens is not only Yonkers hidden gem but has been voted as the best attraction in Westchester County by Tripadvisor.[54] The significant amount of surviving Victorian architecture and number of 19th-century estates in northwest Yonkers has attracted many filmmakers in recent years.[55]

The two block section of Palisade Avenue between Chase and Roberts Avenues in northwest Yonkers is colloquially known as "the north end" or "the end". It was and still is the only retail area in northwest Yonkers, and was well known for its soda fountain, Urich's Stationery, and Robbins Pharmacy. It was once the end of the #2 trolley line, which has since been replaced by a Bee-line Bus route. One part of Yonkers that is sometimes overlooked is Nepera Park. This is a small neighborhood at the northern part of Nepperhan Avenue on the Hastings-on-Hudson border. Nepperhan Avenue in Nepera Park is also a major shopping district for the area.

Southeast Yonkers

Southeast Yonkers is mostly Irish-American (many of the Irish being native born) and Italian-American. Many of the businesses and type of architecture in southeast Yonkers bear a greater resemblance to certain parts of the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island than to points north. Southeastern Yonkers is largely within walking distance of the Woodlawn and Wakefield sections of the Bronx. Many residents regard eastern McLean Avenue, home to a vibrant Irish community shared with Woodlawn, to be the true hub of Yonkers.[citation needed]

Similarly, a portion of Midland Avenue in the Dunwoodie section has been called the "Little Italy" of Yonkers. Landmarks of southeastern Yonkers include the Cross County Shopping Center, Yonkers Raceway, and St. Joseph's Seminary in the Dunwoodie neighborhood, which was visited by Pope John Paul II in October 1995 and later by Pope Benedict XVI in April 2008.[56][57]

Southwest Yonkers

Getty Square is Yonkers's downtown and the civic center and central business district of the city. Much of southwest Yonkers grew densely along the multiple railroads and trolley (now bus) lines along South Broadway and in Getty Square, connecting to New York City. Clusters of apartment buildings surrounded the stations of the Yonkers branch of the New York and Putnam Railroad and the Third Avenue Railway trolley lines and these buildings still remain although now served by the Bee-Line Bus System. The railroad companies themselves built neighborhoods of mixed housing types ranging from apartment buildings to large mansions in areas like Park Hill wherein the railroad also built a funicular to connect it with the train station in the valley. This traditionally African-American and white area has seen a tremendous influx of immigrants from Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, South Asia, and the Middle East. Off South Broadway and Yonkers Avenue one can find residential neighborhoods, such as Lowerre, Nodine Hill, Park Hill, and Hudson Park (off the Hudson River) with a mix of building styles ranging from dense clusters of apartment buildings, blocks of retail with apartments above, multifamily row houses, and detached single-family homes.[58]

Other neighborhoods of these types, although with a larger number of detached houses, are Ludlow Park, Hudson Park, and Van Cortlandt Crest, off Riverdale Avenue next to the border with Riverdale.

The area is also home to significant historical and educational institutions including the historic Philipse Manor Hall (a New York State Historic Site that houses one of three papier-mache ceilings in the United States), The Science Barge, Beczak Environmental Education Center, and a 2003 Yonkers Public Library.[59]

Many residents are of African, Caribbean, Italian, Polish or Mexican descent while an influx those from other cultural backgrounds has continued to shape a culturally diverse community. Some neighborhoods right on the Riverdale border are increasingly becoming home to Orthodox Jews. The revitalization of the Getty Square area has helped to nurture growth for Southwest Yonkers.

In the early 2000s several new luxury apartment buildings were built along the Hudson. There is also a new "Sculpture Meadow on the Hudson", renovation of a Victorian-era pier, and a new public library housed in the remodeled Otis elevator factory. Peter Kelly's award-winning fine dining restaurant X20 - Xaviars on Hudson is located at the renovated pier with much success.[60] In 2020, several more new rental buildings were placed at the river's edge on Alexander Street. Sawyer Place is an 18-story building that sits atop the site of the original old mill.[61][62] There are new proposals along with the current projects which are intended to revitalize downtown Yonkers.

Government

Phillipse Manor Hall was the site of the first Yonkers Village Hall and City Hall from 1868 to approximately 1906.

Yonkers is governed via a Strong mayor-council system. The Yonkers City Council consists of seven members, six each elected from one of six districts, as well as a Council President to preside over the council. The mayor and city council president are elected in a citywide vote. The current mayor is Democrat Mike Spano and the Council President is Michael Khader.

Yonkers is typically a Democratic stronghold just like the rest of Westchester County and most of New York state on the national level. In 1992, Yonkers voted for George H. W. Bush over Bill Clinton and Ross Perot for president, but has voted solidly Democratic ever since. At a local level, recent mayors of Yonkers have included Republicans Phil Amicone and John Spencer, while the Yonkers City Council has mostly been controlled by Republicans. In the State Assembly, Yonkers is represented by Democrats J. Gary Pretlow and Nader Sayegh, and in the New York State Senate, by Democrats Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Shelley Mayer. At the federal level, Democratic representative Jamaal Bowman represents the city.

Education

Public schools in Yonkers are operated by Yonkers Public Schools. There are several other elementary Catholic schools and one Muslim school.

Sarah Lawrence College, which gives its address as Bronxville, NY 10708,[63] is actually located in Yonkers.[64] Westchester Community College, (part of SUNY system) operates a number of extension centers in Yonkers, with the largest one at the Cross County Shopping Center.[65]

Three libraries are operated by the Yonkers Public Library, Crestwood, Riverfront, and Grinton I. Will. Another library, funded by Carnegie, was demolished in May 1982 to make way to expand Nepperhan Avenue into an arterial roadway.

The Japanese School of New York was located in Yonkers for one year; on August 18, 1991, the school moved from Yonkers to Queens, New York City and on September 1, 1992, classes began at its current location in Greenwich, Connecticut.[66]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York operates Catholic schools in Westchester County. St. Peter's Catholic Elementary School at 204 Hawthorne Avenue, founded by the Sisters of Charity, celebrated its 100th anniversary in September 2011. St. Casimir School in Yonkers closed in 2013.[67]

Academy for Jewish Religion, a rabbinical and cantorial school, is located in the Getty Square neighborhood of Yonkers. Saint Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary is located in Crestwood.

Transportation

Mass transit

Yonkers has the eleventh-highest rate of public transit ridership among cities in the United States, and 27% of Yonkers households do not own a car.[68]

Bus service in Yonkers is provided by Westchester County Bee-Line Bus System, the second-largest bus system in New York State, along with some MTA Bus Company express routes to Manhattan. Yonkers is the top origin and destination for the Bee-Line Bus service area, including Westchester and the northern Bronx, with the Getty Square intermodal hub seeing passenger levels in the millions annually.[69]

Yonkers is served by two heavy-rail commuter lines. Hudson Line Metro-North Railroad stations provide commuter service to New York City: Ludlow, Yonkers, Glenwood, and Greystone. The Yonkers station is also served by Amtrak. All of the named Empire Service trains except the Lake Shore Limited serve the Yonkers station. Several Harlem Line stations are on or very near the city's eastern border. These include Wakefield, Mt. Vernon West, Fleetwood, Bronxville, Tuckahoe and Crestwood. A third commuter line dating from the late 19th century, the Putnam Division, was shut down in phases with the final passenger trains making their last runs in 1958. The "Put" as it was known has been paved and is used as a public park, and part of the NY State Empire State Trail which encompasses 750 miles from NYC to Albany, NY.[70]

New York Water Taxi formerly operated a ferry service from downtown Yonkers to Manhattan's Financial District, but it ceased in December 2009.[71]

Yonkers began a dockless bikeshare program operated by LimeBike in May 2018, which was finished by 2020. It now operates an electric scooter program.[72]

Roads and paths

Major limited-access roads in Yonkers include Interstate 87 (the New York State Thruway), the Saw Mill, Bronx River, Sprain Brook and Cross County parkways. US 9, NY 9A and 100 are important surface streets.

The main line of the former New York and Putnam Railroad running through the middle of Yonkers has been converted into a paved walking and bicycling path, called the South County Trailway. It runs north–south in Yonkers from the Hastings-on-Hudson border in the north to the Bronx border in the south at Van Cortlandt Park where it is referred to as the Putnam Greenway.

The historic Croton Aqueduct tunnel has a hard-packed dirt trail, called the Old Croton Aqueduct Trailway, running above it for most of its length in Yonkers, with a few on-street routes on the edge of the Getty Square neighborhood.

Fire department

The city of Yonkers is protected by 459 firefighters of the city of Yonkers Fire Department (YFD), under the command of a Fire Commissioner and 3 Deputy Chiefs. Founded in 1896, the YFD operates out of 11 Fire Stations, located throughout the city in 2 Battalions, under the command of 1 Assistant Chief each shift.[73] The Yonkers Fire Department operates a fire apparatus fleet of 10 Engine Companies, 6 Ladder Companies, 1 Squad (rescue-pumper) Company, 1 Rescue Company, 1 Fireboat, 1 Air Cascade Unit, 1 USAR (Urban Search And Rescue) Collapse Unit, 1 Foam Unit, 1 Haz-Mat Unit, and numerous special, support, and reserve units. The YFD responds to approximately 16,000 emergency calls annually.[74]

Economy

Principal employers

According to Yonkers's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[75] the principal employers in the city are;

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yonkers Raceway | 1,195 |

| 2 | Montefiore IT | 735 |

| 3 | Liberty Lines Transit | 692 |

| 4 | Leake and Watts Services | 615 |

| 5 | POP Displays USA | 538 |

| 6 | Stew Leonard's | 519 |

| 7 | Consumer Reports | 518 |

| 8 | Kawasaki Rail | 415 |

| 9 | American Sugar Refining | 331 |

| 10 | FedEx | 290 |

| 11 | Mindspark Interactive Network | 150 |

Notable people

In popular culture

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

- In the 1925 popular song "If You Knew Susie", the narrator drives his girlfriend Susie to Yonkers from which he had to walk home.[76][77]

- Yonkers is the setting of two feature films by local filmmaker Robert Celestino: Mr. Vincent, a 1997 Sundance Film entrant in the non-competition Spectrum section, and Yonkers Joe, a scheduled 2009 release by Magnolia Pictures, starring Chazz Palminteri and Christine Lahti.[78][79] Yonkers's locations also provide the setting for A Tale of Two Pizzas, a "Romeo and Juliet" theme played out among two rival pizza owners.[80]

- The documentary Brick by Brick: A Civil Rights Story described racial discrimination and housing segregation in Yonkers.[81]

- The 2008 film Doubt, starring Meryl Streep as Sister Aloysius Beauvier, filmed scenes at St. Marks Lutheran Church's school.[82]

- Yonkers is also the location for many major filming projects: Catch Me if You Can, with Tom Hanks and Leonardo DiCaprio; Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, with Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet; Mona Lisa Smile, with Julia Roberts; A Beautiful Mind, with Russell Crowe, Big Daddy (1999), with Adam Sandler, The Preacher's Wife (a remake of The Bishop's Wife), with Denzel Washington and Whitney Houston, Kate & Leopold (2001), with Meg Ryan and Hugh Jackman and The Namesake with Kal Penn and Irrfan Khan.[83][55] Some TV series' episodes of Fringe, The Blacklist, and The Following were taped in the downtown area.[84] The City Hall Courtroom is also the setting for many film scenes and commercials.

- In Max Brooks's novel, World War Z, the US armed forces are defeated in the Battle of Yonkers by a horde of zombies.[85]

- A character in the musical Gypsy: A Musical Fable is named Yonkers.[86]

- Neil Simon's play Lost In Yonkers, set in the city. The story is about two young boys during World War II, whose father leaves them with their grandmother in Yonkers so he can earn money for the family.[87]

- In 2011, rapper Tyler, The Creator of Odd Future released his song "Yonkers", named after the city.[88]

- The HBO miniseries Show Me a Hero takes place, and was filmed, in Yonkers.[89]

- In season 7, episode 10 of Impractical Jokers, the punishment for James S. Murray was filmed in Yonkers City Hall.[90]

- Production for the 2019 Tales of the City miniseries was shot in the Nodine Hills area of the city.[91]

Gallery

-

Yonkers Welcome Sign

-

Yonkers Saint Patrick's Day Parade 2010

-

Fountains at Westchester's Ridge Hill

-

The Yonkers Metro-North Station

-

The Saw Mill River in Getty Square

-

Westbound McLean Avenue at Park Hill Avenue

-

Eastbound Cross County Parkway

Twin towns – sister cities

Yonkers is twinned with:

See also

- Jonkheer

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Yonkers, New York

- Westchester County, New York

References

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Yonkers". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ Mansuda Arora (October 20, 2020). "Follow the River, Follow the Money: On Development in Yonkers". Chronogram Media. Archived from the original on August 30, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

Arts and environmental initiatives have driven a campaign to attract wealthier residents to the riverfront city. It could be a sign of things to come in the Hudson Valley.

- ^ Prudential Centennial Realty. "What Will I Love About Yonkers, NY?". Archived from the original on July 15, 2011.

- ^ "Early Yonkers History – Yonkers Chamber of Commerce". yonkerschamber.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Interactive Map: Dutch Place Names in New York | Dutch New York". thirteen.org. August 19, 2009. Archived from the original on September 6, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- ^ Haynes, Bruce. Red Lines, Black Spaces: The Politics of Race and Space in a Black Middle-Class Suburb. Yale University Press. p. 2.

- ^ Robbins, Dan (August 19, 2014). "Founded In Yonkers, Otis Elevators Took American Industry To New Heights". Westchester Magazine. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ Nevius, Michelle & Nevius, James (2009), Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, New York: Free Press, ISBN 141658997X, p.177-78

- ^ Malone, Michael (April 14, 2021). "Is Westchester County New York City's Sixth Borough?". Westchester Magazine. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Atkins, Thomas Astley (1892). Yonkers in the Rebellion 1861-1965. The Yonkers Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument Association. pp. 21–73.

- ^ Geberer, Raanan (October 17, 2021). "The Putnam Railroad's Journey From Train Line to Rail Trail". Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ "The Putnam Division". nycshs.org. October 15, 2008. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ "Ryder Cup: Painting celebrates Dunfermline links to American golf". BBC. September 22, 2014. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Bellis, Mary (April 13, 2019). "The Story of Bakelite, the First Synthetic Plastic". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ Fallon, Bill (March 3, 2008). "Industrial Arts: Carpet Mills Become Studio Central", Westchester County Business Journal, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e Yonkers in the World War. Norwood, Mass.: The Plimpton Press. 1922.

- ^ "Nodine Hill Tower Collapses; Flood Wrecks Homes, Hurts 9" (PDF). The Herald Statesman. Fulton History. October 23, 1937. pp. 1, 4 & 5.

- ^ "Casualties Mount in Tower Collapse" (PDF). The Herald Statesman. October 25, 1937. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ Schreck, Tom. "Mystery & Intrigue in Mamaroneck". Westchester Magazine. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ No apparent relation to Colt's Patent Firearms. Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877-1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.63.

- ^ "Yonkers, New York Renaissance on the Hudson". CooperatorNews New York. 2016. Archived from the original on September 30, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Feron, James (December 1, 1982). "Otis Elevator To Leave Birthplace". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Tsividis, Yannis (April 1, 2002). "Edwin Armstrong: Pioneer of the Airwaves". Columbia Magazine. Archived from the original on June 28, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Leno, Darren (1985). "RADIO BROADCASTING - World Radio History" (PDF). worldradiohistory.com. p. 50. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ "Wants Subway Extended: Yonkers Mayor to Ask City to Take Over N.Y.C. Branch" (PDF). The New York Times. June 27, 1942. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 23, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ Raskin, Joseph B. (2013). The Routes Not Taken: A Trip Through New York City's Unbuilt Subway System. New York, New York: Fordham University Press. doi:10.5422/fordham/9780823253692.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-82325-369-2.

- ^ a b c d e "New York - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa (September 25, 1988). "In Yonkers, A Measured Integration of Schools". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Yen, Marianne (August 3, 1988). "Judge Holds Yonkers in Contempt". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 30, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Esannson, Harold; Bagwell, Vinnie (1993). A Study of African-American Life in Yonkers From the Turn of the Century. Harold Esannson. p. 50.

- ^ "Leonard B. Sand, Judge in Landmark Yonkers Segregation Case, Dies at 88". The New York Times. December 5, 2016. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Gan, Vicky (August 17, 2015). "Q&A with Lisa Belkin, Author of 'Show Me a Hero'". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "Riverdale Hatzalah". riverdalehatzalah.org. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ "Sherwood Park Cemetery, Yonkers, Westchester County, New York, United States - Nearby Cities, Nearby Cemeteries and Genealogy Resources - Histopolis". Test.histopolis.com. November 21, 2012. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Harrison, Seth (November 12, 2020). "Inside Yonkers St. Joseph's ER...the COVID-19 hotspot". Lohud. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Muchnick, Jeanne (April 16, 2020). "2 new COVID-19 testing sites to open in Yonkers, Mount Vernon on Friday". Lohud. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ "Yonkers Opens More COVID Testing Sites As Students Prepare To Return To Classrooms". CBS New York. December 30, 2021. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Lee, Lindsay (February 19, 2023). "Historic Yonkers Post Office Designated Local Landmark". The Yonkers Ledger. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ Crnic, Ben (September 29, 2023). "State Of Emergency: Flooding Closes Roads, Prompts Evacuations In Westchester". Daily Voice. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Rincón, Sonia (September 29, 2023). "Crews pump out water from homes after historic storm brings flooding to Yonkers". WABC-TV. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Wordsmith.org – Online Chat with Paul Dickson". wordsmith.org. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L. Population of states and counties of the United States: 1790 to 1990 from the Twenty-one Decennial Censuses Archived September 30, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, pp. 108-109. United States Census Bureau, March 1996. ISBN 9780934213486. Accessed October 6, 2013.

- ^ "Decennials - Census of Population and Housing". February 8, 2006. Archived from the original on February 8, 2006.

- ^ a b "Yonkers (city), New York". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 8, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ "Westchester: A County of Immigrants". January 3, 2019. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Jordanians in the New York Metro Area" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ "Albanians in the New York Metro Area" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ "Aerosmith original Raymond Tabano back in Yonkers". lohud. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ Murphy, Dan (June 1, 2023). "Untermyer Gardens Is Ready For Your Visit". Yonkers Times. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Davis, Ken (September 29, 2015). "Yonkers Home Used In Filming Of 'Mona Lisa Smile' Listed For $749,000". Daily Voice. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Berger, Joseph (October 7, 1995). "THE POPE'S VISIT: THE SCENE;Yonkers Turns Out To Glimpse John Paul II". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Bradley Hagerty, Barbara (April 20, 2008). "Pope Delivers Serious Message to Young Catholics". NPR. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ "Yonkers Victorian Homes". victoriansource.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ "Welcome to the Yonkers Public Library!-Hours and Directions". Ypl.org. December 7, 2008. Archived from the original on July 29, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ Lascala, Marisa (February 13, 2010). "No Reservations About Living in the Hudson Valley". Hudson Valley Magazine. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ Garcia, Ernie (December 11, 2018). "What are the rents in Yonkers' newest apartments?". lohud.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ "Sawyer Place – Yonkers, NY" (PDF). images1.loopnet.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 30, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ "Sarah Lawrence College. A Deeper Education". Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ haasdesign: Renee Haas. "History". The Village of Bronxville. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Yonkers Extension Center". Westchester Community Colleges. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ "本校の歩み" Archived January 17, 2014, at archive.today. The Japanese School of New York. Retrieved on January 10, 2012. "1980.12.22 Queens Flushing校に移転。" and "1991.8.18. Westchester Yonkers校へ移転。" and "1992.9.1 Connecticut Greenwich校へ移転。 授業開始。"

- ^ Otterman, Sharon (January 23, 2013). "New York Archdiocese to Close 24 Schools". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ List of U.S. cities with most households without a car

- ^ "Bee-Line System On-Board Survey" (PDF). Transportation.westchestergov.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2015.

- ^ Strauss, Michael (September 13, 1981). "Memories Click Along the Putnam Line". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ New York Water Taxi. "Ferry Between Manhattan and Yonkers Is Set to Stop" Archived July 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ "Yonkers bike-share program launching by end of May". Lohud.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ^ "List of Fire Stations; City of Yonkers". Archived from the original on December 23, 2010.

- ^ "List of Fire Department Apparatus; City of Yonkers". Yonkersny.gov. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ "Annual Financial Report 2018: City of Yonkers, NY". yonkersny.gov.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Impact of Administration's Fiscal 1983 Budget Proposals on National Foundation on the Arts & Humanities & the Institute of Museum Services. Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education of the Committee on Education & Labor, House of Representatives, 97th Congress, 2nd Session, Hearings Held in Washington, D.C., March 4; & New York, N.Y., March 5, 1982. United States Government Printing Office. 1983. p. 110. Archived from the original on September 30, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

Being very musically inclined, as I am, a would-be singer, my first thought of Yonkers was, 'If You Knew Susie.' There's a line in there that says, 'Back from Yonkers, Im the one that had to walk.' That was what I first learned about Yonkers.

- ^ B.G. De Sylva, Joseph Meyer, If You Knew Susie, Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., 1925.

- ^ Filmmaker: "Tribeca Director Interview: Robert Celestino, Yonkers Joe", April 23, 2008

- ^ "Magnolia Pictures: Yonkers Joe press notes". Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- ^ Martel, Ned (October 7, 2005). "Film In Review; A Tale of Two Pizzas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ "Brick by Brick: A Civil Rights Story". California Newsreel. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ Kamen, Abigail; Walsh, Kathryn (August 7, 2015). "Meryl Streep's New Movie Features Local Westchester Spots". Westchester Magazine. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Fuchs, Marek (January 5, 2003). "On Location; New Rochelle? No, Yonkers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ "Filmed in Westchester". visitwestchesterny.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Woerner, Meredith (January 27, 2009). "World War Z Concept Art Rocks The Battle Of Yonkers". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Potempa, Philip (August 22, 2017). "'Gypsy' a stage musical that strips away layers of mothers". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ "Lost in Yonkers". Concord Theatricals. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ "Tyler, The Creator Gets Odd In 'Yonkers'". Rapfix.mtv.com. February 11, 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Final filming for 'Show Me A Hero' underway in Yonkers". News 12. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Failla, Zak (August 3, 2018). "Yonkers City Hall Takes Center Stage For 'Impractical Jokers' Prank". Daily Voice. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Coyne, Matt (October 5, 2018). "Netflix's Armistead Maupin's Tales of the City shoots in Yonkers". lohud.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ Dwyer, William (January 3, 2017). "Did You Know These Westchester Towns Have International Sister Cities?". Westchester Magazine. Archived from the original on September 15, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "ILIRIA NEWS AGENCY - Kamza binjakëzim me Yonkers". October 30, 2011. Archived from the original on October 30, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

Further reading

- Allison, Charles Elmer. The History of Yonkers. Westchester County, New York (1896).

- Duffy, Jennifer Nugent. Who's Your Paddy?: Racial Expectations and the Struggle for Irish American Identity (NYU Press, 2013), Irish Catholics in Yonkers

- Hufeland, Otto. Westchester County During the American Revolution, 1775–1783 (1926)

- Madden, Joseph P. ed. A Documentary History of Yonkers, New York: The Unsettled Years, 1853–1860 (Vol. 2. Heritage Books, 1992)

- Weigold, Marilyn E., Yonkers in the Twentieth Century (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2014). xvi, 364 pp.

External links

- Yonkers, New York

- 1646 establishments in North America

- 1646 establishments in the Dutch Empire

- Cities in New York (state)

- Cities in the New York metropolitan area

- Cities in Westchester County, New York

- Establishments in New Netherland

- Former towns in New York (state)

- Former villages in New York (state)

- New York (state) populated places on the Hudson River

- Populated places established in 1646