North Korea

40°00′N 127°00′E / 40.000°N 127.000°E

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

| |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

Anthem:

| |

Area controlled by the Democratic People's Republic of Korea shown in green | |

| Capital and largest city | Pyongyang |

| Official languages | Korean |

| Official script | Chosŏn'gŭl |

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | |

| Kim Jong-un[a] | |

| Kim Yong-nam[b] | |

• Director of General Political Bureau | Hwang Pyong-so |

• Premier | Pak Pong-ju |

• Vice Chairman of Policy Bureau | Choe Ryong-hae |

| Legislature | Supreme People's Assembly |

| Formation | |

| Before 194 BC | |

| 18 BC | |

| 698 | |

| 918 | |

| 29 August 1910 | |

| 15 August 1945 | |

• Provisional People's Committee for North Korea established | February 1946 |

• Foundation of DPRK | 9 September 1948 |

• Chinese withdrawal | October 1958 |

• Current constitution | 1 April 2013 |

| Area | |

• Total | 120,540 km2 (46,540 sq mi) (98th) |

• Water (%) | 4.87 |

| Population | |

• 2013 estimate | 24,895,000 (48th) |

• 2011 census | 24,052,231[2] |

• Density | 198.3/km2 (513.6/sq mi) (63rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $40 billion[3] |

• Per capita | $1,800[3] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2013 estimate |

• Total | $15,4 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $621[4] |

| HDI (1995) | high (75th) |

| Currency | North Korean won (₩) (KPW) |

| Time zone | UTC+8:30 (Pyongyang Time[6]) |

| Date format | |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +850 |

| ISO 3166 code | KP |

| Internet TLD | .kp |

| |

| North Korea | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Chosŏn Minjujuŭi Inmin Konghwaguk |

North Korea (), officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK ), is a country in East Asia, in the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. Pyongyang is both the nation's capital as well as its largest city. To the north and northwest the country is bordered by China and by Russia along the Amnok (known as the Yalu in China) and Tumen rivers.[7] The country is bordered to the south by South Korea (officially the Republic of Korea), with the heavily fortified Korean Demilitarized Zone separating the two.

The earliest human artifacts found in North Korea (Korean pottery) have been dated to 8000 BC,.[8] There were three kingdoms flourishing on the peninsula in the 1st century BC. The name Korea is derived from the Kingdom of Goguryeo, also spelled as Koryŏ, which was one of East Asia's greatest empires. Starting in the 7th century, Korea under the Later Silla and Balhae dynasties enjoyed over a millennium of relative tranquility under these long lasting dynasties, during which time the Hangul script was created by Sejong the Great (in 1446).[9] Korea was annexed by the Empire of Japan in 1910 until the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II in 1945, when Korea was divided into two zones along the 38th parallel by the United States and the Soviet Union, with the north occupied by the Soviets and the south by the Americans. Negotiations on reunification failed, and in 1948 two separate governments were formed: the Democratic People's Republic of Korea in the north, and the Republic of Korea in the south. An invasion initiated by North Korea led to the Korean War (1950–53). The Korean Armistice Agreement brought about a ceasefire, and no official peace treaty was ever signed.[10] Both states were accepted into the United Nations in 1991.[11] The DPRK officially describes itself as a self-reliant socialist state[12] and formally holds elections. Critics regard it as a totalitarian dictatorship. Various outlets have called it Stalinist,[21][22][23] particularly noting the elaborate cult of personality around Kim Il-sung and his family. International organizations have assessed human rights violations in North Korea as belonging to a category of their own, with no parallel in the contemporary world.[24][25][26] The Workers' Party of Korea, led by a member of the ruling family,[23] holds power in the state and leads the Democratic Front for the Reunification of the Fatherland of which all political officers are required to be members.[27]

Over time North Korea has gradually distanced itself from the world communist movement. Juche, an ideology of national self-reliance, was introduced into the constitution as a "creative application of Marxism–Leninism"[28] in 1972.[29][30] The means of production are owned by the state through state-run enterprises and collectivized farms. Most services such as healthcare, education, housing and food production are subsidized or state-funded.[31] From 1994 to 1998, North Korea suffered from a famine that resulted in the deaths of between 0.24 and 3.5 million people, and the country continues to struggle with food production.[32] North Korea follows Songun, or "military-first" policy.[33] It is the country with the highest number of military and paramilitary personnel, with a total of 9,495,000 active, reserve, and paramilitary personnel. Its active duty army of 1.21 million is the fourth largest in the world, after China, the U.S., and India.[34] It possesses nuclear weapons.[35][36] North Korea is an atheist state with no official religion and where public religion is discouraged.[37]

Etymology

The name Korea derives from Goryeo, itself referring to the ancient kingdom of Goguryeo, the first Korean dynasty visited by Persian merchants who referred to Koryŏ (Goryeo; 고려) as Korea.[38] The term Koryŏ became used to refer to Goguryeo, which renamed itself Koryŏ in the 5th century. The modern spelling, "Korea," first appeared in late 17th century in the travel writings of the Dutch East India Company's Hendrick Hamel.[39]

After Goryeo fell in 1392, Joseon or Chosun became the official name for the entire territory, and it was not universally accepted. The new official name has its origin in the ancient country of Gojoseon (Old Joseon). In 1897, the Joseon dynasty changed the official name of the country from Joseon to Daehan Jeguk (Korean Empire). The name Daehan, which means "great Han" literally, derives from Samhan (Three Hans). Under Japanese rule, the names Han and Joseon coexisted.

After the division of the country, the two sides used different terms to refer to Korea: Chosun or Joseon (조선) in North Korea, and Hanguk (한국) in South Korea. In 1948, North Korea adopted Democratic People's Republic of Korea (조선민주주의인민공화국/朝鮮民主主義人民共和國) as its new legal name. In the wider world, because the government controlled the northern part of the Korean Peninsula, it is commonly called North Korea to distinguish it from South Korea, which is officially called the Republic of Korea.

History

Gojoseon

The history of Korea begins with the founding of Joseon (often known as "Gojoseon" to prevent confusion with another dynasty founded in the 14th century; the prefix Go- means 'older,' 'before,' or 'earlier') in 2333 BC by Dangun, according to Korean foundation mythology.[45][46]

Gojoseon expanded until it controlled northern Korean Peninsula and some parts of Manchuria. Gija Joseon was purportedly founded in the 12th century BC, and its existence and role have been controversial in the modern era.[46][47]

In the 2nd century BC, Wiman Joseon fell to Han China near the end of the century. Later the Han Dynasty set up Four Commanderies of Han in 108 BC. There was a significant Chinese presence in northern parts of the Korean peninsula during the next century, and the Lelang Commandery persisted for about 400 years until it was conquered by Goguryeo.[48] After many conflicts with the Chinese Han Dynasty, Gojoseon disintegrated, leading to the Proto–Three Kingdoms of Korea period.

Three Kingdoms of Korea

In the early centuries AD, Buyeo, Okjeo, Dongye, and the Samhan confederacy occupied the peninsula and southern Manchuria. Of the various states, Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla grew to control the peninsula as the Three Kingdoms of Korea. Goguryeo, the largest and most powerful among them, was a highly militaristic state,[49][50] and competed with various Chinese dynasties during its 700 years of history. Goguryeo experienced a golden age under Gwanggaeto the Great and his son Jangsu,[51][52][53][54] who both subdued Baekje and Silla during their times, achieving a brief unification of the Three Kingdoms of Korea and becoming the most dominant power on the Korean Peninsula.[55][56] In addition to contesting for control of the Korean Peninsula, Goguryeo had many military conflicts with various Chinese dynasties,[57] most notably the Goguryeo–Sui War, in which Goguryeo defeated a huge force said to number over a million men.[58][59][60][61][62] Baekje was a great maritime power;[63] its nautical skill, which made it the Phoenicia of East Asia, was instrumental in the dissemination of Buddhism throughout East Asia and continental culture to Japan.[64][65] Baekje was once a great military power on the Korean Peninsula, especially during the time of Geunchogo,[66] but was critically defeated by Gwanggaeto the Great and declined.[67] Silla was the smallest and weakest of the three, but it used cunning diplomatic means to make opportunistic pacts and alliances with the more powerful Korean kingdoms, and eventually Tang China, to its great advantage.[68][69]

North–South Kingdoms

The unification of the Three Kingdoms by Silla in 676 led to the North South States Period, in which much of the Korean Peninsula was controlled by Later Silla, while Balhae controlled the northern parts of Goguryeo. Balhae was founded by a Goguryeo general and formed as a successor state to Goguryeo. During its height, Balhae controlled most of Manchuria and parts of the Russian Far East.

Later Silla was a golden age of art and culture,[70][71][72][73] as evidenced by the Hwangnyongsa, Seokguram, and Emille Bell. Relationships between Korea and China remained relatively peaceful during this time. Later Silla carried on the maritime prowess of Baekje, which acted like the Phoenicia of medieval East Asia,[74] and during the 8th and 9th centuries dominated the seas of East Asia and the trade between China, Korea and Japan, most notably during the time of Jang Bogo; in addition, Silla people made overseas communities in China on the Shandong Peninsula and the mouth of the Yangtze River.[75][76][77][78] Later Silla was a prosperous and wealthy country,[79] and its metropolitan capital of Gyeongju[80] was the fourth largest city in the world.[81][82][83][84] Buddhism flourished during this time, and many Korean Buddhists gained great fame among Chinese Buddhists[85] and contributed to Chinese Buddhism,[86] including: Woncheuk, Wonhyo, Uisang, Musang,[87][88][89][90] and Kim Gyo-gak, a Silla prince whose influence made Mount Jiuhua one of the Four Sacred Mountains of Chinese Buddhism.[91][92][93][94][95] However, Later Silla weakened under internal strife and the revival of Baekje and Goguryeo, which led to the Later Three Kingdoms period in the late 9th century.

Goryeo

In 936, the Later Three Kingdoms were united by Wang Geon, a descendant of Goguryeo nobility,[96][97] who established Goryeo as the successor state of Goguryeo.[98][99][100][101] Balhae had fallen to the Khitan Empire in 926, and a decade later the last crown prince of Balhae fled south to Goryeo, where he was warmly welcomed and included into the ruling family by Wang Geon, thus unifying the two successor nations of Goguryeo.[102] Like Silla, Goryeo was a highly cultural state and created the Jikji in 1377, using the world's oldest metal movable type printing press.[40][41][42][43][44][103][104] After defeating the Khitan Empire, which was the most powerful empire of its time,[105][106] in the Goryeo–Khitan War, Goryeo experienced a golden age that lasted a century, during which the Tripitaka Koreana was completed and there were great developments in printing and publishing, promoting learning and dispersing knowledge on philosophy, literature, religion, and science; by 1100, there were 12 universities that produced famous scholars and scientists.[107][108] However, the Mongol invasions in the 13th century greatly weakened the kingdom. Goryeo was never conquered by the Mongols, but exhausted after three decades of fighting, the Korean court sent its crown prince to the Yuan capital to swear allegiance to Kublai Khan, who accepted, and married one of his daughters to the Korean crown prince.[109] Henceforth, Goryeo continued to rule Korea, though as a tributary ally to the Mongols for the next 86 years. During this period, the two nations became intertwined as all subsequent Korean kings married Mongol princesses,[109] and the last empress of the Yuan dynasty was a Korean princess.[110] After the Mongolian Empire collapsed, severe political strife followed and the Goryeo Dynasty was replaced by the Joseon Dynasty in 1392, following a rebellion by General Yi Seong-gye.

Joseon

King Taejo declared the new name of Korea as "Joseon" in reference to Gojoseon, and moved the capital to Hanseong (one of the old names of Seoul).[111] The first 200 years of the Joseon dynasty were marked by peace, and saw great advancements in science[112][113] and education,[114] as well as the creation of Hangul by Sejong the Great to promote literacy among the common people.[115] The prevailing ideology of the time was Neo-Confucianism, which was epitomized by the seonbi class: nobles who passed up positions of wealth and power to lead lives of study and integrity.

Between 1592 and 1598, Japan invaded Korea. Toyotomi Hideyoshi led the Japanese forces, but his advance was halted by Korean forces (most notably the Joseon Navy led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin and his renowned "turtle ship")[116][117][118][119][120] with assistance from Righteous Army militias formed by Korean civilians, and Ming Dynasty Chinese troops. Through a series of successful battles of attrition, the Japanese forces were eventually forced to withdraw, and relations between all parties became normalized. In 1627 and 1637, Joseon suffered two separate invasions by the Manchu, which also extended to China and led to the conquest of the Ming Dynasty. After the second Manchu invasion in 1637, Joseon experienced a nearly 200-year period of peace. Kings Yeongjo and Jeongjo particularly led a new renaissance of the Joseon Dynasty during the 18th century.[121][122]

Japanese occupation (1910–45)

The latter years of the Joseon dynasty were marked by isolation from the outside world. During the 19th century, Korea's isolationist policy earned it the name the "Hermit kingdom". The Joseon dynasty tried to protect itself against Western imperialism, but was eventually forced to open trade. After the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, Korea was occupied by Japan (1910–45).

Japan tried to suppress Korean traditions and culture and ran the economy primarily for its own benefit. Anti-Japanese, pro-liberation rallies took place nationwide on 1 March 1919 (the March 1st Movement). About 7,000 people were killed during the suppression of this movement. Continued anti-Japanese uprisings, such as the nationwide uprising of students in 1929, led to the strengthening of military rule in 1931. After the outbreaks of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and World War II, Japan stepped up efforts to extinguish Korean culture.

Koreans were forced to adopt Japanese names. Worship at Japanese Shinto shrines was made compulsory. The school curriculum was modified to eliminate teaching in the Korean language and history. Numerous Korean cultural artifacts were destroyed or taken to Japan. Resistance groups known as Dongnipgun (Liberation Army) operated along the Sino-Korean border, fighting guerrilla warfare against Japanese forces. Some of them took part in allied action in China and parts of South East Asia. One of the guerrilla leaders was the communist Kim Il-sung, who later became the leader of North Korea.

During World War II, Koreans at home were forced to support the Japanese war effort. Tens of thousands of men were conscripted into Japan's military. Around 200,000 girls and women, many from Korea, were forced to engage in sexual services for the Japanese military, with the euphemism "comfort women".

Soviet occupation and division of Korea (1945–50)

At the end of World War II in 1945, the Korean Peninsula was divided into two zones along the 38th parallel, with the northern half of the peninsula occupied by the Soviet Union and the southern half by the United States. Initial hopes for a unified, independent Korea evaporated as the politics of the Cold War resulted in the establishment of two separate states with diametrically opposed political, economic, and social systems.

Soviet general Terentii Shtykov recommended the establishment of the Soviet Civil Authority in October 1945, and supported Kim Il-sung as chairman of the Provisional People's Committee for North Korea, established in February 1946. During the provisional government, Shtykov's chief accomplishment was a sweeping land reform program that broke North Korea's stratified class system. Landlords and Japanese collaborators fled to the South, where there was no land reform and sporadic unrest. Shtykov nationalized key industries and led the Soviet delegation to talks on the future of Korea in Moscow and Seoul.[123][124][125][126][127] In September 1946, South Korean citizens had risen up against the Allied Military Government. In April 1948, an uprising of the Jeju islanders was violently crushed. The South declared its statehood in May 1948 and two months later the ardent anti-communist Syngman Rhee[128] became its ruler. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea was established in the North on 9 September 1948. Shtykov served as the first Soviet ambassador, while Kim Il-sung became premier.

Soviet forces withdrew from the North in 1948 and most American forces withdrew from the South in 1949. Ambassador Shtykov suspected Rhee was planning to invade the North, and was sympathetic to Kim's goal of Korean unification under socialism. The two successfully lobbied Joseph Stalin to support a short blitzkrieg of the South, which culminated in the outbreak of the Korean War.[123][124][125][126]

Korean War (1950–53)

The military of North Korea invaded the South on 25 June 1950, and swiftly overran most of the country. A United Nations force, led by the United States, intervened to defend the South, and rapidly advanced into North Korea. As they neared the border with China, Chinese forces intervened on behalf of North Korea, shifting the balance of the war again. Fighting ended on 27 July 1953, with an armistice that approximately restored the original boundaries between North and South Korea. More than one million civilians and soldiers were killed in the war. As a result of the war, almost every substantial building in North Korea was destroyed.[129][130]

Some have referred to the conflict as a civil war, with other factors involved.[131] The Korean War was the first armed confrontation of the Cold War and set the standard for many later conflicts. It is often viewed as an example of the proxy war, where the two superpowers would fight in another country, forcing the people in that country to suffer most of the destruction and death involved in a war between such large nations. The superpowers avoided descending into an all-out war against one another, as well as the mutual use of nuclear weapons. It expanded the Cold War, which to that point had mostly been concerned with Europe.

A heavily guarded demilitarized zone (DMZ) still divides the peninsula, and an anti-communist and anti-North Korea sentiment remains in South Korea. Since the war, the United States has maintained a strong military presence in the South which is depicted by the North Korean government as an imperialist occupation force.[132]

Post-war developments

The relative peace between the South and the North following the armistice was interrupted by border skirmishes, celebrity abductions, and assassination attempts. The North failed in several assassination attempts on South Korean leaders, such as in 1968, 1974 and the Rangoon bombing in 1983; tunnels were found under the DMZ and war nearly broke out over the axe murder incident at Panmunjom in 1976.[133] For almost two decades after the war, the two states did not seek to negotiate with one another. In 1971, secret, high-level contacts began to be conducted culminating in the 1972 July 4th North-South Joint Statement that established principles of working toward peaceful reunification. The talks ultimately failed because in 1973, South Korea declared its preference that the two Koreas should seek separate memberships in international organizations.[134]

During the 1956 August Faction Incident, Kim Il-sung successfully resisted efforts by the Soviet Union and China to depose him in favor of Soviet Koreans or the pro-Chinese Yan'an faction.[135][136] The last Chinese troops withdrew from the country in October 1958, which is the consensus as the latest date when North Korea became effectively independent. Some scholars believe that the 1956 August incident demonstrated independence.[135][136][137] North Korea remained closely aligned to China and the Soviet Union, and the Sino-Soviet split allowed Kim to play the powers off each other.[138] North Korea sought to become a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, and emphasized the ideology of Juche to distinguish it from both the Soviet Union and China.[139]

Recovery from the war was quick — by 1957 industrial production reached 1949 levels. In 1959, relations with Japan had improved somewhat, and North Korea began allowing the repatriation of Japanese citizens in the country. The same year, North Korea revalued the North Korean won, which held greater value than its South Korean counterpart. Until the 1960s, economic growth was higher than in South Korea, and North Korean GDP per capita was equal to that of its southern neighbor as late as 1976.[140]

In the early 1970s, China began normalizing its relations with the West, particularly the U.S., and reevaluating its relations with North Korea. The diplomatic problems culminated in 1976 with the death of Mao Zedong. In response, Kim Il-sung began severing ties with China and reemphasizing national and economic self-reliance enshrined in his Juche Idea, which promoted producing everything within the country. By the 1980s the economy had begun to stagnate, started its long decline in 1987, and almost completely collapsed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 when all Russian aid was suddenly halted. The North began reestablishing trade relations with China shortly thereafter, but the Chinese could not afford to provide enough food aid to meet demand.

The Arduous March

In 1992, as Kim Il-sung's health began deteriorating, Kim Jong-il slowly began taking over various state tasks. Kim Il-sung died of a heart attack in 1994, in the midst of a standoff with the United States over North Korean nuclear weapon development. Kim declared a three-year period of national mourning before officially announcing his position as the new leader.

North Korean efforts to build nuclear weapons were halted by the Agreed Framework, negotiations with U.S. president Bill Clinton. Kim Jong-il instituted a policy called Songun, or "military first". There is much speculation about this policy being used as a strategy to strengthen the military while discouraging coup attempts. Restrictions on travel were tightened and the state security apparatus was strengthened.

Flooding in the mid-1990s exacerbated the economic crisis, severely damaging crops and infrastructure and led to widespread famine which the government proved incapable of curtailing. In 1996, the government accepted UN food aid. Since the outbreak of the famine, the government has reluctantly tolerated illegal black markets while officially maintaining a state socialist economy. Corruption flourished and disillusionment with the regime spread.

In the late 1990s, North Korea began making attempts at normalizing relations with the West and continuously renegotiating disarmament deals with U.S. officials in exchange for economic aid. At the same time, building on Nordpolitik, South Korea began to engage with the North as part of its Sunshine Policy.[141][142]

21st century

The international environment changed with the election of U.S. president George W. Bush in 2001. His administration rejected South Korea's Sunshine Policy and the Agreed Framework. The U.S. government treated North Korea as a rogue state, while North Korea redoubled its efforts to acquire nuclear weapons to avoid the fate of Iraq.[143][144][145]

On October 9, 2006, North Korea announced it had conducted its first nuclear weapons test.[146][147]

In August 2009, former President Bill Clinton, of the United States, met with Kim Jong-il to secure the release of two American journalists who had been sentenced for entering the country illegally.[148] Current U.S. president Barack Obama's position towards North Korea has been to resist making deals with North Korea for the sake of defusing tension, a policy known as "strategic patience."[149]

Tensions with South Korea and the United States increased in 2010 with the sinking of the South Korean warship Cheonan[150] and North Korea's shelling of Yeonpyeong Island.[151][152]

On 17 December 2011, the supreme leader of North Korea Kim Jong-il died from a heart attack. His youngest son Kim Jong-un was announced as his successor.[153]

Over the following years, North Korea continued to develop its nuclear arsenal despite international condemnation. Notable tests were performed in 2013 and 2016.[154]

Geography

North Korea occupies the northern portion of the Korean Peninsula, lying between latitudes 37° and 43°N, and longitudes 124° and 131°E. It covers an area of 120,540 square kilometres (46,541 sq mi). North Korea shares land borders with China and Russia to the north, and borders South Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone. To its west are the Yellow Sea and Korea Bay, and to its east lies Japan across the Sea of Japan (East Sea of Korea).

Early European visitors to Korea remarked that the country resembled "a sea in a heavy gale" because of the many successive mountain ranges that crisscross the peninsula.[155] Some percent of North Korea is composed of mountains and uplands, separated by deep and narrow valleys. All of the Korean Peninsula's mountains with elevations of 2,000 meters (6,600 ft) or more are located in North Korea. The highest point in North Korea is Paektu Mountain, a volcanic mountain with an elevation of 2,744 meters (9,003 ft) above sea level.[155] Other prominent ranges are the Hamgyong Range in the extreme northeast and the Rangrim Mountains, which are located in the north-central part of North Korea. Mount Kumgang in the Taebaek Range, which extends into South Korea, is famous for its scenic beauty.[155]

The coastal plains are wide in the west and discontinuous in the east. A great majority of the population lives in the plains and lowlands. According to a United Nations Environmental Programme report in 2003, forest covers over 70 percent of the country, mostly on steep slopes.[156] The longest river is the Amnok (Yalu) River which flows for 790 kilometres (491 mi).[157]

North Korea experiences a combination of continental climate and an oceanic climate,[156][158] but most of the country experiences a humid continental climate within the Köppen climate classification scheme. Winters bring clear weather interspersed with snow storms as a result of northern and northwestern winds that blow from Siberia.[158] Summer tends to be by far the hottest, most humid, and rainiest time of year because of the southern and southeastern monsoon winds that carry moist air from the Pacific Ocean. Approximately 60 percent of all precipitation occurs from June to September.[158] Spring and autumn are transitional seasons between summer and winter. The daily average high and low temperatures for Pyongyang are −3 and −13 °C (27 and 9 °F) in January and 29 and 20 °C (84 and 68 °F) in August.[158]

Administrative divisions

| Map | Namea | Chosŏn'gŭl | Administrative seat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital city (chikhalsi)a | |||||

| 1 | Pyongyang | 평양직할시 | (Chung-guyok) | ||

| Special city (teukbyeolsi)a | |||||

| 2 | Rason * | 라선특별시 | (Rajin-guyok) * | ||

| Provinces (do)a | |||||

| 3 | South Pyongan | 평안남도 | Pyongsong | ||

| 4 | North Pyongan | 평안북도 | Sinuiju | ||

| 5 | Chagang | 자강도 | Kanggye | ||

| 6 | South Hwanghae | 황해남도 | Haeju | ||

| 7 | North Hwanghae | 황해북도 | Sariwon | ||

| 8 | Kangwon | 강원도 | Wonsan | ||

| 9 | South Hamgyong | 함경남도 | Hamhung | ||

| 10 | North Hamgyong | 함경북도 | Chongjin | ||

| 11 | Ryanggang * | 량강도 | Hyesan | ||

| * – Rendered in Southern dialects as "Yanggang" (양강), "Nason" (나선), or "Najin" (나진). | |||||

Government and politics

North Korea functions as a highly centralized, one-party republic. According to its 2009 constitution, it is a self-described revolutionary and socialist state "guided in its activities by the Juche idea and the Songun idea".[159] The Workers' Party of Korea (WPK) has an estimated 3,000,000 members and dominates every aspect of North Korean politics. It has two satellite organizations, the Korean Social Democratic Party and the Chondoist Chongu Party[160] which participate in the WPK-led Democratic Front for the Reunification of the Fatherland. Another highly influential structure is the independent National Defence Commission (NDC). Kim Jong-un of the Kim family heads all major governing structures: he is First Secretary of the WPK, First Chairman of the NDC, and Supreme Commander of the Korean People's Army.[161][162] Kim Il-sung, who died in 1994, is the country's "Eternal President",[163] while Kim Jong-il was announced "Eternal General Secretary" after his death in 2011.[161]

The unicameral Supreme People's Assembly (SPA) is the highest organ of state authority and holds the legislative power. Its 687 members are elected every five years by universal suffrage. Supreme People's Assembly sessions are convened by the SPA Presidium, whose president (Kim Yong-nam since 1998) represents the state in relations with foreign countries. Deputies formally elect the President, the vice-presidents and members of the Presidium and take part in the constitutionally appointed activities of the legislature: pass laws, establish domestic and foreign policies, appoint members of the cabinet, review and approve the state economic plan, among others.[164] The SPA itself cannot initiate any legislation independently of party or state organs. It is unknown whether it has ever criticized or amended bills placed before it, and the elections are based around a single list of WPK-approved candidates who stand without opposition.[165]

Executive power is vested in the Cabinet of North Korea, which is headed by Premier Pak Pong-ju.[166] The Premier represents the government and functions independently. His authority extends over two vice-premiers, 30 ministers, two cabinet commission chairmen, the cabinet chief secretary, the president of the Central Bank, the director of the Central Statistics Bureau and the president of the Academy of Sciences. A 31st ministry, the Ministry of People's Armed Forces, is under the jurisdiction of the National Defence Commission.[167]

Political ideology

The Juche ideology is the cornerstone of party works and government operations. It is viewed by the official North Korean line as an embodiment of Kim Il-sung's wisdom, an expression of his leadership, and an idea which provides "a complete answer to any question that arises in the struggle for national liberation".[168] Juche was pronounced in December 1955 in order to emphasize a Korea-centered revolution.[168] Its core tenets are economic self-sufficiency, military self-reliance and an independent foreign policy. The roots of Juche were made up of a complex mixture of factors, including the cult of personality centered on Kim Il-sung, the conflict with pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese dissenters, and Korea's centuries-long struggle for independence.[169]

It was initially promoted as a "creative application" of Marxism–Leninism, but in the mid-1970s, it was described by state propaganda as "the only scientific thought... and most effective revolutionary theoretical structure that leads to the future of communist society". Juche eventually replaced Marxism–Leninism entirely by the 1980s,[170] and in 1992 references to the latter were omitted from the constitution.[171] The 2009 constitution dropped references to communism, but retained references to socialism.[172] Juche's concepts of self-reliance have evolved with time and circumstances, but still provide the groundwork for the spartan austerity, sacrifice and discipline demanded by the party.[173]

Some foreign observers have described North Korea's political system as an absolute monarchy[174][175][176] or a "hereditary dictatorship".[177] Others view its ideology as a racialist-focused nationalism similar to that of Shōwa Japan,[178][179][180][181] bearing a resemblance to European fascism,[182] or sui generis.[183]

Personality cult

The North Korean government exercises control over many aspects of the nation's culture, and this control is used to perpetuate a cult of personality surrounding Kim Il-sung,[184] and Kim Jong-il.[185] While visiting North Korea in 1979, journalist Bradley Martin wrote that nearly all music, art, and sculpture that he observed glorified "Great Leader" Kim Il-sung, whose personality cult was then being extended to his son, "Dear Leader" Kim Jong-il.[186] Martin reported that there is even widespread belief that Kim Il-sung "created the world", and Kim Jong-il could "control the weather".[186]

Such reports are contested by North Korea researcher B. R. Myers: "Divine powers have never been attributed to either of the two Kims. In fact, the propaganda apparatus in Pyongyang has generally been careful not to make claims that run directly counter to citizens' experience or common sense."[187] He further explains that the state propaganda painted Kim Jong-il as someone whose expertise lay in military matters and that the famine of the 1990s was partially caused by natural disasters out of Kim Jong-il's control.[188]

The song "No Motherland Without You", sung by the North Korean army choir, was created especially for Kim Jong-il and is one of the most popular tunes in the country. Kim Il-sung is still officially revered as the nation's "Eternal President". Several landmarks in North Korea are named for Kim Il-sung, including Kim Il-sung University, Kim Il-sung Stadium, and Kim Il-sung Square. Defectors have been quoted as saying that North Korean schools deify both father and son.[189] Kim Il-sung rejected the notion that he had created a cult around himself, and accused those who suggested this of "factionalism".[186] Following the death of Kim Il-sung, North Koreans were prostrating and weeping to a bronze statue of him in an organized event;[190] similar scenes were broadcast by state television following the death of Kim Jong-il.[191]

Critics maintain this Kim Jong-il personality cult was inherited from his father. Kim Jong-il was often the center of attention throughout ordinary life. His birthday is one of the most important public holidays in the country. On his 60th birthday (based on his official date of birth), mass celebrations occurred throughout the country.[192] Kim Jong-il's personality cult, although significant, was not as extensive as his father's. One point of view is that Kim Jong-il's cult of personality was solely out of respect for Kim Il-sung or out of fear of punishment for failure to pay homage.[193] Media and government sources from outside of North Korea generally support this view,[194][195][196][197][198] while North Korean government sources say that it is genuine hero worship.[199]

In a more recent event – on 11 June 2012 – a 14-year-old North Korean schoolgirl drowned while attempting to rescue portraits of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il from a flood.[200]

Law enforcement and internal security

North Korea has a civil law system based on the Prussian model and influenced by Japanese traditions and communist legal theory.[201] Judiciary procedures are handled by the Central Court (the highest court of appeal), provincial or special city-level courts, people's courts and special courts. People's courts are at the lowest level of the system and operate in cities, counties and urban districts, while different kinds of special courts handle cases related to military, railroad or maritime matters.[202]

Judges are theoretically elected by their respective local people's assemblies, but in practice they are appointed by the Workers' Party of Korea. The penal code is based on the principle of nullum crimen sine lege (no crime without a law), but remains a tool for political control despite several amendments reducing ideological influence.[202] Courts carry out legal procedures related to not only criminal and civil matters, but also political cases as well.[203] Political prisoners are sent to labor camps, while criminal offenders are incarcerated in a separate system.[204]

The Ministry of People's Security (MPS) maintains most law enforcement activities. It is one of the most powerful state institutions in North Korea and oversees the national police force, investigates criminal cases and manages non-political correctional facilities.[205] It handles other aspects of domestic security like civil registration, traffic control, fire departments and railroad security.[206] The State Security Department was separated from the MPS in 1973 to conduct domestic and foreign intelligence, counterintelligence and manage the political prison system. Political camps can be short-term reeducation zones or "kwalliso" (total control zones) for lifetime detention.[207] Camp 14 in Kaechon,[208] Camp 15 in Yodok[209] and Camp 18 in Bukchang[210] are described in detailed testimonies.[211]

The security apparatus is very extensive,[212] exerting strict control over residence, travel, employment, clothing, food and family life.[213] Security establishments employ mass surveillance, tightly monitoring cellular and digital communications. The MPS, State Security and the police allegedly conduct real-time monitoring of text messages, online data transfer, monitor phone calls and automatically transcribe recorded conversations. They reportedly have the capacity to triangulate a subscriber's exact location, while military intelligence monitors phone and radio traffic as far as 140 kilometers (87 miles) south of the Demilitarized zone.[214]

Foreign relations

Initially, North Korea had diplomatic ties with only other communist countries. In the 1960s and 1970s, it pursued an independent foreign policy, established relations with many developing countries, and joined the Non-Aligned Movement. In the late 1980s and the 1990s its foreign policy was thrown into turmoil with the collapse of the Soviet bloc. Suffering an economic crisis, it closed a number of its embassies. At the same time, North Korea sought to build relations with developed free market countries.[215] As a result of its isolation, it is sometimes known as the "hermit kingdom", a term that was originally referred to the isolationism in the latter part of the Joseon Dynasty.[216]

As of 2015[update], North Korea had diplomatic relations with 166 countries and embassies in 47 countries.[215] North Korea continues to have strong ties with its socialist southeast Asian allies in Vietnam and Laos, as well as with Cambodia.[217] Most of the foreign embassies to North Korea are located in Beijing rather than in Pyongyang.[218] The Korean Demilitarized Zone with South Korea is the most heavily fortified border in the world.[219]

As a result of the North Korean nuclear weapons program, the six-party talks were established to find a peaceful solution to the growing tension between the two Korean governments, Russia, China, Japan, and the United States. North Korea was previously designated a state sponsor of terrorism[220] because of its alleged involvement in the 1983 Rangoon bombing and the 1987 bombing of a South Korean airliner.[221] On 11 October 2008, the United States removed North Korea from its list of states that sponsor terrorism after Pyongyang agreed to cooperate on issues related to its nuclear program.[222] The kidnapping of at least 13 Japanese citizens by North Korean agents in the 1970s and the 1980s was another issue in the country's foreign policy.[223]

Korean reunification

North Korea's policy is to seek reunification without what it sees as outside interference, through a federal structure retaining each side's leadership and systems. In 2000, both North and South Korea signed the June 15th North–South Joint Declaration in which both sides made promises to seek out a peaceful reunification.[224] The Democratic Federal Republic of Korea is a proposed state first mentioned by then North Korean president Kim Il-sung on 10 October 1980, proposing a federation between North and South Korea in which the respective political systems would initially remain.[225]

Inter-Korean relations are at the core of North Korean diplomacy and have seen numerous shifts in the last few decades. In 1972, the two Koreas agreed in principle to achieve reunification through peaceful means and without foreign interference.[226] Relations remained cool well until the early 1990s, with a brief period in the early 1980s when North Korea provided flood relief to its southern neighbor and the two countries organized a reunion of 92 separated families.[227]

The Sunshine Policy instituted by South Korean president Kim Dae-jung in 1998 was a watershed in inter-Korean relations. It encouraged other countries to engage with the North, which allowed Pyongyang to normalize relations with a number of European Union states and contributed to the establishment of joint North-South economic projects. The culmination of the Sunshine Policy was the 2000 Inter-Korean Summit, when Kim Dae-jung visited Kim Jong-il in Pyongyang.[228] On 4 October 2007, South Korean president Roh Moo-hyun and Kim Jong-il signed an eight-point peace agreement.[229]

Relations worsened in the late 2000s and early 2010s when South Korean president Lee Myung-bak adopted a more hard-line approach and suspended aid deliveries pending the de-nuclearization of the North. North Korea responded by ending all of its previous agreements with the South.[230] It deployed additional ballistic missiles[231] and placed its military on full combat alert after South Korea, Japan and the United States threatened to intercept a Unha-2 space launch vehicle.[232] The next few years witnessed a string of hostilities, including the alleged North Korean involvement in the sinking of South Korean warship Cheonan,[150] mutual ending of diplomatic ties,[233] a North Korean artillery attack on Yeonpyeong Island,[234] and an international crisis involving threats of a nuclear exchange.[235]

Military

The Korean People's Army (KPA) is North Korea's military organization. The KPA has 1,106,000 active and 8,389,000 reserve and paramilitary troops, making it the largest military institution in the world.[236] About 20 percent of men aged 17–54 serve in the regular armed forces,[34] and approximately one in every 25 citizens is an enlisted soldier.[35][237] The KPA has five branches: Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, Special Operations Force, and Rocket Force. Command of the Korean People's Army lies in both the Central Military Commission of the Workers' Party of Korea and the independent National Defense Commission. The Ministry of People's Armed Forces is subordinated to the latter.[238]

Of all KPA branches, the Ground Force is the largest. It has approximately one million personnel divided into 80 infantry divisions, 30 artillery brigades, 25 special warfare brigades, 20 mechanized brigades, 10 tank brigades and seven tank regiments.[239] They are equipped with 3,700 tanks, 2,100 armoured personnel carriers and infantry fighting vehicles,[240] 17,900 artillery pieces, 11,000 anti-aircraft guns[241] and some 10,000 MANPADS and anti-tank guided missiles.[242] Other equipment includes 1,600 aircraft in the Air Force and 1,000 vessels in the Navy.[243] North Korea has the largest special forces and the largest submarine fleet in the world.[244]

North Korea possesses nuclear weapons, but its arsenal remains limited. Various estimates put its stockpile at less than 10 plutonium warheads[245][246] and 12–27 nuclear weapon equivalents if uranium warheads are considered.[247] Delivery capabilities[248] are provided by the Rocket Force, which has some 1,000 ballistic missiles with a range of up to 3,000 kilometres.[249]

According to a 2004 South Korean assessment, North Korea possesses a stockpile of chemical weapons estimated to amount to 2,500–5,000 tons, including nerve, blister, blood, and vomiting agents, as well as the ability to cultivate and produce biological weapons including anthrax, smallpox, and cholera.[250][251] Because of its nuclear and missile tests, North Korea has been sanctioned under United Nations Security Council resolutions 1695 of July 2006, 1718 of October 2006, 1874 of June 2009, and 2087 of January 2013.

The military faces some issues limiting its conventional capabilities, including obsolete equipment, insufficient fuel supplies and a shortage of digital command and control assets. To compensate for these deficiencies, the KPA has deployed a wide range of asymmetric warfare technologies like anti-personnel blinding lasers,[252] GPS jammers,[253] midget submarines and human torpedoes,[254] stealth paint,[255] electromagnetic pulse bombs,[256] and cyberwarfare units.[257] KPA units have attempted to jam South Korean military satellites.[258]

Much of the equipment is engineered and produced by a domestic defense industry. Weapons are manufactured in roughly 1,800 underground defense industry plants scattered throughout the country, most of them located in Chagang Province.[259] The defense industry is capable of producing a full range of individual and crew-served weapons, artillery, armored vehicles, tanks, missiles, helicopters, surface combatants, submarines, landing and infiltration craft, Yak-18 trainers and possibly co-production of jet aircraft.[212] According to official North Korean media, military expenditures for 2010 amount to 15.8 percent of the state budget.[260]

Society

Demographics

With the exception of a small Chinese community and a few ethnic Japanese, North Korea's 24,852,000 people are ethnically homogeneous.[261][262] Demographic experts in the 20th century estimated that the population would grow to 25.5 million by 2000 and 28 million by 2010, but this increase never occurred due to the North Korean famine.[263] It began in 1995, lasted for three years and resulted in the deaths of between 300,000 and 800,000 North Koreans annually.[264] The deaths were most likely caused by malnutrition-related illnesses like pneumonia and tuberculosis rather than starvation.[264]

International donors led by the United States initiated shipments of food through the World Food Program in 1997 to combat the famine.[265] Despite a drastic reduction of aid under the George W. Bush Administration,[266] the situation gradually improved: the number of malnourished children declined from 60% in 1998[267] to 37% in 2006[268] and 28% in 2013.[269] Domestic food production almost recovered to the recommended annual level of 5.37 million tons of cereal equivalent in 2013,[270] but the World Food Program reported a continuing lack of dietary diversity and access to fats and proteins.[271]

The famine had a significant impact on the population growth rate, which declined to 0.9% annually in 2002[263] and 0.53% in 2014.[272] Late marriages after military service, limited housing space and long hours of work or political studies further exhaust the population and reduce growth.[263] The national birth rate is 14.5 births per year per 1,000 population.[273] Two-thirds of households consist of extended families mostly living in two-room units. Marriage is virtually universal and divorce is extremely rare.[274]

Health

North Korea had a life expectancy of 69.8 years in 2013.[275] While North Korea is classified as a low-income country, the structure of North Korea's causes of death (2013) is unlike that of other low-income countries.[276] Instead, it is closer to worldwide averages, with non-communicable diseases—such as cardiovascular disease and cancers—accounting for two-thirds of the total deaths.[276]

A 2013 study reported that communicable diseases and malnutrition are responsible for 29% of the total deaths in North Korea. This figure is higher than those of high-income countries and South Korea, but half of the average 57% of all deaths in other low-income countries.[276] Infectious diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and hepatitis B are considered to be endemic to the country as a result of the famine.[277]

Cardiovascular disease as a single disease group is the largest cause of death in North Korea (2013).[276] The three major causes of death in DPR Korea are ischaemic heart disease (13%), lower respiratory infections (11%) and cerebrovascular disease (7%).[278] Non-communicable diseases risk factors in North Korea include high rates of urbanisation, an aging society, high rates of smoking and alcohol consumption amongst men.[276]

According to 2003 report by the United States Department of State, almost 100% of the population has access to water and sanitation.[277] 60% of the population had access to improved sanitation facilities in 2000.[279]

A free universal insurance system is in place.[31] Quality of medical care varies significantly by region[280] and is often low, with severe shortages of equipment, drugs and anaesthetics.[281] According to WHO, expenditure on health per capita is one of the lowest in the world.[281] Preventive medicine is emphasized through physical exercise and sports, nationwide monthly checkups and routine spraying of public places against disease. Every individual has a lifetime health card which contains a full medical record.[282]

Education

The 2008 census listed the entire population as literate, including those in the age group beyond 80.[274] An 11-year free, compulsory cycle of primary and secondary education is provided in more than 27,000 nursery schools, 14,000 kindergartens, 4,800 four-year primary and 4,700 six-year secondary schools.[267] 77% of males and 79% of females aged 30–34 have finished secondary school.[274] An additional 300 universities and colleges offer higher education.[267] Kim Il-sung University is the only one with four-year courses.[citation needed]

Most graduates from the compulsory program do not attend university but begin their obligatory military service or proceed to work in farms or factories instead. The main deficiencies of higher education are the heavy presence of ideological subjects, which comprise 50% of courses in social studies and 20% in sciences,[283] and the imbalances in curriculum. The study of natural sciences is greatly emphasized while social sciences are neglected.[284] Heuristics is actively applied to develop the independence and creativity of students throughout the system.[285] Studying of Russian and English language was made compulsory in upper middle schools in 1978.[286]

Language

North Korea shares the Korean language with South Korea, although some dialectal differences exist within both Koreas.[267] North Koreans refer to their Pyongyang dialect as munhwa ("cultured language") as opposed to South Korea's Seoul dialect, the p'yojun'o ("standard language"), which is viewed as decadent because of its usage of Chinese and English loanwords.[287] Words of Chinese or Western origin have been eliminated from munhwa along with the usage of Chinese hancha characters.[287] Written language uses the chosŏn'gul phonetic alphabet, developed under Sejong the Great (1418–1450).[288]

Religion

North Korea is an atheist state where public religion is discouraged.[37] There are no known official statistics of religions in North Korea. According to Religious Intelligence, 64.3% of the population are irreligious adherents of the Juche idea, 16% practice Korean shamanism, 13.5% practice Chondoism, 4.5% are Buddhist, and 1.7% are Christian.[289] Freedom of religion and the right to religious ceremonies are constitutionally guaranteed, but religions are formally restricted by the government.[290][291]

The influence of Buddhism and Confucianism still has an effect on cultural life.[292][293] Buddhists reportedly fare better than other religious groups. They are given limited funding by the government to promote the religion, because Buddhism played an integral role in traditional Korean culture.[294]

Chondoism ("Heavenly Way") is an indigenous syncretic belief combining elements of Korean shamanism, Buddhism, Taoism and Catholicism that is officially represented by the WPK-controlled Chongu Party.[295] In contrast, the Open Doors mission claims the most severe persecution of Christians in the world occurs in North Korea.[296] Four state-sanctioned churches exist, but freedom of religion advocates claim these are showcases for foreigners.[297][298] Amnesty International has expressed concerns about religious persecution in North Korea.[299]

Formal ranking of citizens' loyalty

According to North Korean documents and refugee testimonies,[300] all North Koreans are sorted into groups according to their Songbun, an ascribed status system based on a citizen's assessed loyalty to the regime. Based on their own behavior and the political, social, and economic background of their family for three generations as well as behavior by relatives within that range, Songbun is allegedly used to determine whether an individual is trusted with responsibility, given opportunities,[301] or even receives adequate food.[300][302]

Songbun allegedly affects access to educational and employment opportunities and particularly whether a person is eligible to join North Korea's ruling party.[301] There are 3 main classifications and about 50 sub-classifications. According to Kim Il-sung, speaking in 1958, the loyal "core class" constituted 25% of the North Korean population, the "wavering class" 55%, and the "hostile class" 20%.[300] The highest status is accorded to individuals descended from those who participated with Kim Il-sung in the resistance against Japanese occupation during and before World War II and to those who were factory workers, laborers, or peasants in 1950.[303]

While some analysts believe private commerce recently changed the Songbun system to some extent,[304] most North Korean refugees say it remains a commanding presence in everyday life.[300] The North Korean government claims all citizens are equal and denies any discrimination on the basis of family background.[305]

Human rights

North Korea is widely accused of having one of the worst human rights records in the world.[307] North Koreans have been referred to as "some of the world's most brutalized people" by Human Rights Watch, because of the severe restrictions placed on their political and economic freedoms.[308][309] The North Korean population is strictly managed by the state and all aspects of daily life are subordinated to party and state planning. Employment is managed by the party on the basis of political reliability, and travel is tightly controlled by the Ministry of People's Security.[310]

Amnesty International reports of severe restrictions on the freedom of association, expression and movement, arbitrary detention, torture and other ill-treatment resulting in death, and executions.[311] North Korea applies capital punishment, including public executions. Human rights organizations estimate that 1,193 executions had been carried out in the country as of 2009.[312]

The State Security Department extrajudicially apprehends and imprisons those accused of political crimes without due process.[313] People perceived as hostile to the government, such as Christians or critics of the leadership,[314] are deported to labor camps without trial,[315] often with their whole family and mostly without any chance of being released.[316]

Based on satellite images and defector testimonies, Amnesty International estimates that around 200,000 prisoners are held in six large political prison camps,[314][317] where they are forced to work in conditions approaching slavery.[318] Supporters of the government who deviate from the government line are subject to reeducation in sections of labor camps set aside for that purpose. Those who are deemed politically rehabilitated may reassume responsible government positions on their release.[319]

North Korean defectors[320] have provided detailed testimonies on the existence of the total control zones where abuses such as torture, starvation, rape, murder, medical experimentation, forced labor, and forced abortions have been reported.[211] On the basis of these abuses, as well as persecution on political, religious, racial and gender grounds, forcible transfer of populations, enforced disappearance of persons and forced starvation, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry has accused North Korea of crimes against humanity.[321][322][323] The International Coalition to Stop Crimes Against Humanity in North Korea (ICNK) estimates that over 10,000 people die in North Korean prison camps every year.[324]

The North Korean government rejects the human rights abuses claims, calling them "a smear campaign" and a "human rights racket" aimed at regime change.[325][326][327] In a report to the UN, North Korea dismissed accusations of atrocities as "wild rumors". The government admitted some human rights issues related to living conditions and stated that it is working to improve them.[328]

Propaganda in North Korea

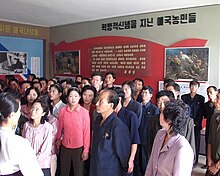

The standard view of propaganda in North Korea sees it as based on the Juche ideology and on the promotion of the Workers' Party of Korea. Many pictures of the national leaders are posted throughout the country. News reports in 2007 suggested that North Korea spent 40% of its national budget on the "idolization" of leaders.

In previous decades, North Korean propaganda was crucial to the formation and promotion of the cult of personality centered around the founder of the totalitarian state, Kim Il-sung. The Soviet Union began to develop him, particularly as a resistance fighter, as soon as they put him in power. This quickly surpassed its Eastern European models. Instead of depicting his actual residence in a Soviet village during the war with the Japanese, he was claimed to have fought a guerilla war from a secret base. Once relations with the Soviet Union were broken off, their role was expurgated, as were all other nationalists, until the claim was made that he founded the Communist Party in North Korea. He is seldom shown in action during the Korean War, which, if it was presented as a glorious victory, nevertheless devastated the country; instead, soldiers are depicted as inspired by him. Subsequently, many stories are recounted of his "on-the-spot guidance" in various locations, many of them being openly presented as fictional. This was supplemented with propaganda on behalf of his son, Kim Jong-il. The "food shortage" produced anecdotes of Kim insisting on eating the same meager food as other North Koreans.[329] Propaganda efforts began for the "Young General", Kim Jong-un, who succeeded him as paramount leader of North Korea on Kim Jong-il's death in December 2011.

Economy

North Korea has maintained one of the most closed and centralized economies in the world since the 1940s.[330] For several decades it followed the Soviet pattern of five-year plans with the ultimate goal of achieving self-sufficiency. Extensive Soviet and Chinese support allowed North Korea to rapidly recover from the Korean War and register very high growth rates. Systematic inefficiency began to arise around 1960, when the economy shifted from the extensive to the intensive development stage. The shortage of skilled labor, energy, arable land and transportation significantly impeded long-term growth and resulted in consistent failure to meet planning objectives.[331] The major slowdown of the economy contrasted with South Korea, which surpassed the North in terms of absolute Gross Domestic Product and per capita income by the 1980s.[332] North Korea declared the last seven-year plan unsuccessful in December 1993 and thereafter stopped announcing plans.[333]

The loss of Eastern Bloc trading partners and a series of natural disasters throughout the 1990s caused severe hardships, including widespread famine. By 2000, the situation improved owing to a massive international food assistance effort, but the economy continues to suffer from food shortages, dilapidated infrastructure and a critically low energy supply.[334] In an attempt to recover from the collapse, the government began structural reforms in 1998 that formally legalized private ownership of assets and decentralized control over production.[335] A second round of reforms in 2002 led to an expansion of market activities, partial monetization, flexible prices and salaries, and the introduction of incentives and accountability techniques.[336] Despite these changes, which were reportedly reversed soon after implementation,[281] North Korea remains a command economy where the state owns almost all means of production and development priorities are defined by the government.[334]

North Korea has the structural profile of a relatively industrialized country[337] where nearly half of the Gross Domestic Product is generated by industry[338] and human development is at medium levels.[339] Purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP is estimated at $40 billion,[340] with a very low per capita value of $1,800.[341] In 2012, Gross national income per capita was $1,523, compared to $28,430 in South Korea.[342] The North Korean won is the national currency, issued by the Central Bank of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea.[343]

The economy is heavily nationalized.[344] Food and housing are extensively subsidized by the state; education and healthcare are free;[345] and the payment of taxes was officially abolished in 1974.[346] A variety of goods are available in department stores and supermarkets in Pyongyang,[347] though most of the population relies on small-scale jangmadang markets.[348][349] In 2009, the government attempted to stem the expanding free market by banning jangmadang and the use of foreign currency,[334] heavily devaluing the won and restricting the convertibility of savings in the old currency,[281] but the resulting inflation spike and rare public protests caused a reversal of these policies.[350] Private trade is dominated by women because most men are required to be present at their workplace, even though many state-owned enterprises are non-operational.[351]

Industry and services employ 65%[352] of North Korea's 12.6 million labor force.[353] Major industries include machine building, military equipment, chemicals, mining, metallurgy, textiles, food processing and tourism.[354] Iron ore and coal production are among the few sectors where North Korea performs significantly better than its southern neighbor – it produces about 10 times larger amounts of each resource.[355] The agricultural sector was shattered by the natural disasters of the 1990s.[356] Its 3,500 cooperatives and state farms[357] were among the most productive and successful in the world around 1980[358] but now experience chronic fertilizer and equipment shortages. Rice, corn, soybeans and potatoes are some of the primary crops.[334] A significant contribution to the food supply comes from commercial fishing and aquaculture.[334] Tourism has been a growing sector for the past decade.[359] North Korea aims to increase the number of foreign visitors from 200,000 to one million by 2016 through projects like the Masikryong Ski Resort.[360]

Foreign trade surpassed pre-crisis levels in 2005 and continues to expand.[361] North Korea has a number of special economic zones (SEZs) and Special Administrative Regions where foreign companies can operate with tax and tariff incentives while North Korean establishments gain access to improved technology.[362] Initially four such zones existed, but they yielded little overall success.[363] The SEZ system was overhauled in 2013 when 14 new zones were opened and the Rason Special Economic Zone was reformed as a joint Chinese-North Korean project.[364] The Kaesong Industrial Region is a special economic zone where more than 100 South Korean companies employ some 52,000 North Korean workers.[365] Outside inter-Korean trade, more than 89% of external trade is conducted with China. Russia is the second-largest foreign partner with $100 million worth of imports and exports for the same year.[366] In 2014, Russia wrote off 90% of North Korea's debt and the two countries agreed to conduct all transactions in rubles.[367][368] Overall, external trade in 2013 reached a total of $7.3 billion (the highest amount since 1990[366]), while inter-Korean trade dropped to an eight-year low of $1.1 billion.[369]

Infrastructure

North Korea's energy infrastructure is obsolete and in disrepair. Power shortages are chronic and would not be alleviated even by electricity imports because the poorly maintained grid causes significant losses during transmission.[370] Coal accounts for 70% of primary energy production, followed by hydroelectric power with 17%.[371] The government under Kim Jong-un has increased emphasis on renewable energy projects like wind farms, solar parks, solar heating and biomass.[372] A set of legal regulations adopted in 2014 stressed the development of geothermal, wind and solar energy along with recycling and environmental conservation.[372][373]

North Korea also strives to develop its own civilian nuclear program. These efforts are under much international dispute due to their military applications and concerns about safety.[374] Russian energy company Gazprom has a project for a $2.5 billion gas pipeline to South Korea through Pyongyang, which is expected to generate an annual revenue of $100 million from transit fees.[375][376]

Transport infrastructure includes railways, highways, water and air routes, but rail transport is by far the most widespread. North Korea has some 5,200 kilometres of railways mostly in standard gauge which carry 80% of annual passenger traffic and 86% of freight, but electricity shortages undermine their efficiency.[371] Construction of a high-speed railway connecting Kaesong, Pyongyang and Sinuiju with speeds exceeding 200 km/h was approved in 2013.[377] North Korea connects with the Trans-Siberian Railway through Rajin.[378]

Road transport is very limited — only 724 kilometers of the 25,554 kilometer road network are paved,[379] and maintenance on most roads is poor.[380] Only 2% of the freight capacity is supported by river and sea transport, and air traffic is negligible.[371] All port facilities are ice-free and host a merchant fleet of 158 vessels.[381] Eighty-two airports[382] and 23 helipads[383] are operational and the largest serve the state-run airline, Air Koryo.[371] Cars are relatively rare, but bicycles are common.[384]

Science and technology

R&D efforts are concentrated at the State Academy of Sciences, which runs 40 research institutes, 200 smaller research centers, a scientific equipment factory and six publishing houses.[385] The government considers science and technology to be directly linked to economic development.[386][387] A five-year scientific plan emphasizing IT, biotechnology, nanotechnology, marine and plasma research was carried out in the early 2000s.[386] A 2010 report by the South Korean Science and Technology Policy Institute identified polymer chemistry, single carbon materials, nanoscience, mathematics, software, nuclear technology and rocketry as potential areas of inter-Korean scientific cooperation. North Korean institutes are strong in these fields of research, although their engineers require additional training and laboratories need equipment upgrades.[388]

Under its "constructing a powerful knowledge economy" slogan, the state has launched a project to concentrate education, scientific research and production into a number of "high-tech development zones". International sanctions remain a significant obstacle to their development.[389] The Miraewon network of electronic libraries was established in 2014 under similar slogans.[390]

Significant resources have been allocated to the national space program, which is managed by the National Aerospace Development Administration (formerly managed by the Korean Committee of Space Technology until April 2013)[391][392] Domestically produced launch vehicles and the Kwangmyŏngsŏng satellite class are launched from two spaceports, the Tonghae Satellite Launching Ground and the Sohae Satellite Launching Station. After four failed attempts, North Korea became the tenth spacefaring nation with the launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2 in December 2012, which successfully reached orbit but was believed to be crippled and non-operational.[393][394] It joined the Outer Space Treaty in 2009[395] and has stated its intentions to undertake manned and Moon missions.[392] The government insists the space program is for peaceful purposes, but the United States, Japan, South Korea and other countries maintain that it serves to advance military ballistic missile programs.[396]

On 7 February 2016, North Korea successfully launched a long-range rocket, supposedly to place a satellite into orbit. Critics believe that the real purpose of the launch was to test a ballistic missile. The launch was strongly condemned by the UN Security Council.[397][398][399] A statement broadcast on Korean Central Television said that a new Earth observation satellite, Kwangmyongsong-4, had successfully been put into orbit less than 10 minutes after lift-off from the Sohae space centre in North Phyongan province.[397]

Usage of communication technology is controlled by the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications. An adequate nationwide fiber-optic telephone system with 1.18 million fixed lines[400] and expanding mobile coverage is in place.[401] Most phones are installed for senior government officials and installation requires written explanation why the user needs a telephone and how it will be paid for.[402] Cellular coverage is available with a 3G network operated by Koryolink, a joint venture with Orascom Telecom Holding.[403] The number of subscribers has increased from 3,000 in 2002[404] to almost two million in 2013.[403] International calls through either fixed or cellular service are restricted, and mobile Internet is not available.[403]

Internet access itself is limited to a handful of elite users and scientists. Instead, North Korea has a walled garden intranet system called Kwangmyong,[405] which is maintained and monitored by the Korea Computer Center.[406] Its content is limited to state media, chat services, message boards,[405] an e-mail service and an estimated 1,000–5,500 websites.[407] Computers employ the Red Star OS, an operating system derived from Linux, with a user shell visually similar to that of OS X.[407] On September 19, 2016, a TLDR project noticed the North Korean internet DNS data and Top Level Domain was left open which allowed global DNS zone transfers. A dump of the data discovered was shared on GitHub.[408][409]

Culture

Despite a historically strong Chinese influence, Korean culture has shaped its own unique identity.[410] It came under attack during the Japanese rule from 1910 to 1945, when Japan enforced a cultural assimilation policy. Koreans were encouraged to learn and speak Japanese, adopt the Japanese family name system and Shinto religion, and were forbidden to write or speak the Korean language in schools, businesses, or public places.[411]

After the peninsula was divided in 1945, two distinct cultures formed out of the common Korean heritage. North Koreans have little exposure to foreign influence.[412] The revolutionary struggle and the brilliance of the leadership are some of the main themes in art. "Reactionary" elements from traditional culture have been discarded and cultural forms with a "folk" spirit have been reintroduced.[412]

Korean heritage is protected and maintained by the state.[413] Over 190 historical sites and objects of national significance are cataloged as National Treasures of North Korea, while some 1,800 less valuable artifacts are included in a list of Cultural Assets. The Historic Sites and Monuments in Kaesong and the Complex of Goguryeo Tombs are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[414]

Art

Visual arts are generally produced in the aesthetics of Socialist realism.[415] North Korean painting combines the influence of Soviet and Japanese visual expression to instill a sentimental loyalty to the system.[416] All artists in North Korea are required to join the Artists' Union, and the best among them can receive an official licence to portray the leaders. Portraits and sculptures depicting Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un are classed as "Number One works".[415]

Most aspects of art have been dominated by Mansudae Art Studio since its establishment in 1959. It employs around 1,000 artists in what is likely the biggest art factory in the world where paintings, murals, posters and monuments are designed and produced.[417] The studio has commercialized its activity and sells its works to collectors in a variety of countries including China, where it is in high demand.[416] Mansudae Overseas Projects is a subdivision of Mansudae Art Studio that carries out construction of large-scale monuments for international customers.[417] Some of the projects include the African Renaissance Monument in Senegal,[418] and the Heroes' Acre in Namibia.[419]

Music

The government emphasized optimistic folk-based tunes and revolutionary music throughout most of the 20th century.[412] Ideological messages are conveyed through massive orchestral pieces like the "Five Great Revolutionary Operas" based on traditional Korean ch'angguk.[420] Revolutionary operas differ from their Western counterparts by adding traditional instruments to the orchestra and avoiding recitative segments.[421] Sea of Blood is the most widely performed of the Five Great Operas: since its premiere in 1971, it has been played over 1,500 times,[422] and its 2010 tour in China was a major success.[421] Western classical music by Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky and other composers is performed both by the State Symphony Orchestra and student orchestras.[423]

Pop music appeared in the 1980s with the Pochonbo Electronic Ensemble and Wangjaesan Light Music Band.[424] Improved relations with South Korea following the Inter-Korean Summit caused a decline in direct ideological messages in pop songs, but themes like comradeship, nostalgia and the construction of a powerful country remained.[425] Today, the all-girl Moranbong Band is the most popular group in the country.[426] North Koreans have also been exposed to K-pop which spreads through illegal markets.[427]

Literature

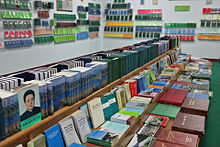

Unlike the former Soviet Union, no literary underground exists and there are no known dissident writers.[428] All publishing houses are owned by the government or the WPK because they are considered an important tool for propaganda and agitation.[429] The Workers' Party of Korea Publishing House is the most authoritative among them and publishes all works of Kim Il-sung, ideological education materials and party policy documents.[430] The availability of foreign literature is limited, examples being North Korean editions of Indian, German, Chinese and Russian fairy tales, Tales from Shakespeare and some works of Bertolt Brecht and Erich Kästner.[416]

Kim Il-sung's personal works are considered "classical masterpieces" while the ones created under his instruction are labeled "models of Juche literature". These include The Fate of a Self-Defense Corps Man, The Song of Korea and Immortal History, a series of historical novels depicting the suffering of Koreans under Japanese occupation.[412][420] More than four million literary works were published between the 1980s and the early 2000s, but almost all of them belong to a narrow variety of political genres like "army-first revolutionary literature".[431]

Science fiction is considered a secondary genre because it somewhat departs from the traditional standards of detailed descriptions and metaphors of the leader. The exotic settings of the stories give authors more freedom to depict cyberwarfare, violence, sexual abuse and crime, which are absent in other genres. Sci-fi works glorify technology and promote the Juche concept of anthropocentric existence through depictions of robotics, space exploration and immortality.[432]

Media

Government policies towards film are no different than those applied to other arts — motion pictures serve to fulfill the targets of "social education". Some of the most influential films are based on historic events (An Jung-geun shoots Itō Hirobumi) or folk tales (Hong Gildong).[420] Most movies have predictable propaganda story lines which make cinema an unpopular entertainment. Viewers only see films that feature their favorite actors.[428] Western productions are only available at private showings to high-ranking Party members,[433] although the 1997 Titanic is frequently shown to university students as an example of Western culture.[434] Access to foreign media products is available through smuggled DVDs and television or radio broadcasts in border areas.[435]

North Korean media are under some of the strictest government control in the world. Freedom of the press in 2013 was 177th out of 178 countries in a Reporters Without Borders index.[436] According to Freedom House, all media outlets serve as government mouthpieces, all journalists are Party members and listening to foreign broadcasts carries the threat of a death penalty.[437] The main news provider is the Korean Central News Agency. All 12 newspapers and 20 periodicals, including Rodong Sinmun, are published in the capital.[438]