Odesa: Difference between revisions

Tachypaidia (talk | contribs) |

m →History |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

=== Ottoman Yedisan === |

=== Ottoman Yedisan === |

||

Khadjibey came under direct control of the Ottoman Empire after 1529 as part of a region known as Yedisan, and was administered in the Ottoman [[Silistra Province, Ottoman Empire|Silistra (Özi) Province]]. In the mid-18th century, the Ottomans rebuilt a [[Fortification|fortress]] at Khadjibey (also was known Hocabey), which was named ''Yeni Dünya'' (literally "New World"). Hocabey was a [[sanjak]] centre of [[Silistre]] Province. |

Khadjibey came under direct control of the Ottoman Empire after 1529 as part of a region known as Yedisan, and was administered in the Ottoman [[Silistra Province, Ottoman Empire|Silistra (Özi) Province]]. In the mid-18th century, the Ottomans rebuilt a [[Fortification|fortress]] at Khadjibey (also was known Hocabey), which was named ''Yeni Dünya'' (literally "New World"). Hocabey was a [[sanjak]] centre of [[Silistre]] Province. |

||

=== Foundation === |

|||

The city of Odessa, located in the South of Ukraine, at the Black sea shore, was founded 1794 by immigrants from Genoa and Naples, Venice and Palermo. The precise spot where the city was founded had been originally personally explored and marked by Stephano De Rivarola, the Italian diplomat to Russia. |

|||

The first Governor of Odessa was Neapolitan-born Giuseppe De Ribas (1749-1800). During the three years of his tenure (1794-97), Admiral De Ribas managed to build a vibrant city, whose first settlers, developers and actual founders were Italians. |

|||

Artists, sculptors, traders and musicians from Genoa, Livomo, Siena, Naples, Venice and Calabria flocked to this new “Europe” in thousands, in search of a better life and promising professional opportunities. |

|||

Customs house, wharfs, the port, residential buildings and Opera House were simultaneously built by the Italian settlers, following the projects by Italian architects and with the construction materials, transported from Naples, Genoa, and Livorno. |

|||

The first Italian founders of the Russian free port include the following families: De Ribas, Venturi, Buba, Rocco, Trabotti, Grimaldi, Frapolli, Inglesi, Gatorno, and Gaius. |

|||

The port correspondence, customs control, and trade matters had all been conducted in Italian, the lingua franca of the Russian Black Sea Coast up until the end of the 19th century. |

|||

Only in 1853 the Odessa Italian colony began to disintegrate due to the reverse migration back to Italy and rise of the Russian Empire, the key players in the field were the families of Ralli, Dzerbolini, Rocco, Gorini, Zarifi, Trabotti, Porro, Rossi, and Gari. The entire Russian Empire benefited from the last Odessa Italian colony. |

|||

The first Italian immigrants radically shifted the cultural course of Odessa for centuries to come. The Italian language reflected not so much the demographics of the city, but the political, economic, social, and cultural power which the Italian settlers enjoyed since the foundation of Odessa. All the key positions in banking, navigation, port administration, shipping, and different industries were held by Italians. |

|||

The Italian language not only prevailed in Odessa business and trade but it would be the favored tongue of the aristocratic salons, opera, schools, and the street. The traces of Italian have remained in the specific Odessa Russian even today. |

|||

The first Italian settlers had established the utterly unique permanent European traditions in this most non-Russian, non-Soviet, and non-Ukrainian city, affecting profoundly not only the port and shipping but the cultural institutions as well. Odessa would become the seat of 18 colleges, the centre of Italian studies in Russia, a prominent centre for the study of the Humanities and Sciences, with the most developed musical, theatrical, and artistic training. “Here all breathes Europe” (Alexander Pushkin) |

|||

Odessa’s Italianness would become somewhat of a taboo topic in historical discourse of Odessa. The story of the Italian migration to the Black Sea remained expunged from the historiographical accounts for a long period of time. |

|||

The Mediterranean image of Odessa was formed by brilliant creations of Boffo, Bernadazzi, Frapolli, Torichelli, Digby, and Delia Acqua and other Italian architects. |

|||

Having established a home away from home, Italian immigrants brought to Russia a Mediterranean way of life and cultural sensibility unknown to the rest of the country.” <ref>http://www.lifebeyondtourism.org/magazine/273/Odessa%2C-the-Last-Italian-Black-Sea-Colony</ref> |

|||

=== In the Russian Empire === |

=== In the Russian Empire === |

||

Revision as of 17:41, 26 March 2015

Odesa (Одеса) Odessa (Одесса) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| Oblast | Odessa Oblast |

| Municipality | Odessa Municipality |

| Port founded | 2 September 1794 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gennady Trukhanov[1] |

| Area | |

| • City | 236.9 km2 (91.5 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 40 m (130 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 65 m (213 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −4.2 m (−13.8 ft) |

| Population (1 July 2011) | |

| • City | 1,003,705 |

| • Density | 6,141/km2 (15,910/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,191,0001 |

| • Demonym | Template:Lang-uk |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 65000–65480 |

| Area code | +380 48 |

| Website | www.odessa.ua |

| 1 The population of the metropolitan area is from 2001. | |

Odessa or Odesa (Template:Lang-uk, [oˈdɛsɐ]; Russian: Оде́сса, IPA: [ɐˈdʲesə]) is the third largest city in Ukraine with a population of 1,003,705. The city is a major seaport and transportation hub located on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. Odessa is also an administrative center of the Odessa Oblast and a multiethnic major cultural center.

The predecessor of Odessa, a small Tatar settlement, was founded by Hacı I Giray, the Khan of Crimea, in 1440 and originally named after him as "Hacıbey"[citation needed]. After a period of Lithuanian control, it passed into the domain of the Ottoman Sultan in 1529 and remained in Ottoman hands until the Ottoman Empire's defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1792.

In 1794, the city of Odessa was founded by a decree of the Empress Catherine the Great. From 1819 to 1858, Odessa was a free port. During the Soviet period it was the most important port of trade in the Soviet Union and a Soviet naval base. On 1 January 2000, the Quarantine Pier at Odessa Commercial Sea Port was declared a free port and free economic zone for a period of 25 years.

During the 19th century, it was the fourth largest city of Imperial Russia, after Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Warsaw.[2] Its historical architecture has a style more Mediterranean than Russian, having been heavily influenced by French and Italian styles. Some buildings are built in a mixture of different styles, including Art Nouveau, Renaissance and Classicist.[3]

Odessa is a warm water port. The city of Odessa hosts two important ports: Port of Odessa itself and Port Yuzhne (also an internationally important oil terminal), situated in the city's suburbs. Another important port, Illichivsk, is located in the same oblast, to the south-west of Odessa. Together they represent a major transport hub integrating with railways. Odessa's oil and chemical processing facilities are connected to Russia's and EU's respective networks by strategic pipelines.

Name

Like most towns of New Russia, the city was named in compliance with the Greek Plan, in this instance after the ancient Greek city of Odessos (Ὀδησσός), which was mistakenly believed to have been located here. Although Odessa is located in between the ancient Greek cities of Tyras (Τύρας) and Olbia (Ὀλβία), Odessos is believed to be the predecessor of the present day city of Varna, Bulgaria.[4]

History

Early history

The site of Odessa was once occupied by an ancient Greek colony.[5] Archaeological artifacts confirm links between the Odessa area and the eastern Mediterranean.

In the Middle Ages successive rulers of the Odessa region included various nomadic tribes (Petchenegs, Cumans), the Golden Horde, the Crimean Khanate, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Ottoman Empire. Yedisan Crimean Tatars traded there in the 14th century.

During the reign of Khan Hacı I Giray of Crimea (1441–1466), the Khanate was endangered by the Golden Horde and the Ottoman Turks and, in search of allies, the khan agreed to cede the area to Lithuania. The site of present-day Odessa was then a town known as Khadjibey (named for Hacı I Giray, and also spelled Kocibey in English, Hacıbey or Hocabey in Turkish, and Hacıbey in Crimean Tatar). It was part of the Dykra region. However, most of the rest of the area remained largely uninhabited in this period.

Ottoman Yedisan

Khadjibey came under direct control of the Ottoman Empire after 1529 as part of a region known as Yedisan, and was administered in the Ottoman Silistra (Özi) Province. In the mid-18th century, the Ottomans rebuilt a fortress at Khadjibey (also was known Hocabey), which was named Yeni Dünya (literally "New World"). Hocabey was a sanjak centre of Silistre Province.

Foundation

The city of Odessa, located in the South of Ukraine, at the Black sea shore, was founded 1794 by immigrants from Genoa and Naples, Venice and Palermo. The precise spot where the city was founded had been originally personally explored and marked by Stephano De Rivarola, the Italian diplomat to Russia.

The first Governor of Odessa was Neapolitan-born Giuseppe De Ribas (1749-1800). During the three years of his tenure (1794-97), Admiral De Ribas managed to build a vibrant city, whose first settlers, developers and actual founders were Italians. Artists, sculptors, traders and musicians from Genoa, Livomo, Siena, Naples, Venice and Calabria flocked to this new “Europe” in thousands, in search of a better life and promising professional opportunities.

Customs house, wharfs, the port, residential buildings and Opera House were simultaneously built by the Italian settlers, following the projects by Italian architects and with the construction materials, transported from Naples, Genoa, and Livorno. The first Italian founders of the Russian free port include the following families: De Ribas, Venturi, Buba, Rocco, Trabotti, Grimaldi, Frapolli, Inglesi, Gatorno, and Gaius. The port correspondence, customs control, and trade matters had all been conducted in Italian, the lingua franca of the Russian Black Sea Coast up until the end of the 19th century. Only in 1853 the Odessa Italian colony began to disintegrate due to the reverse migration back to Italy and rise of the Russian Empire, the key players in the field were the families of Ralli, Dzerbolini, Rocco, Gorini, Zarifi, Trabotti, Porro, Rossi, and Gari. The entire Russian Empire benefited from the last Odessa Italian colony.

The first Italian immigrants radically shifted the cultural course of Odessa for centuries to come. The Italian language reflected not so much the demographics of the city, but the political, economic, social, and cultural power which the Italian settlers enjoyed since the foundation of Odessa. All the key positions in banking, navigation, port administration, shipping, and different industries were held by Italians.

The Italian language not only prevailed in Odessa business and trade but it would be the favored tongue of the aristocratic salons, opera, schools, and the street. The traces of Italian have remained in the specific Odessa Russian even today.

The first Italian settlers had established the utterly unique permanent European traditions in this most non-Russian, non-Soviet, and non-Ukrainian city, affecting profoundly not only the port and shipping but the cultural institutions as well. Odessa would become the seat of 18 colleges, the centre of Italian studies in Russia, a prominent centre for the study of the Humanities and Sciences, with the most developed musical, theatrical, and artistic training. “Here all breathes Europe” (Alexander Pushkin) Odessa’s Italianness would become somewhat of a taboo topic in historical discourse of Odessa. The story of the Italian migration to the Black Sea remained expunged from the historiographical accounts for a long period of time.

The Mediterranean image of Odessa was formed by brilliant creations of Boffo, Bernadazzi, Frapolli, Torichelli, Digby, and Delia Acqua and other Italian architects. Having established a home away from home, Italian immigrants brought to Russia a Mediterranean way of life and cultural sensibility unknown to the rest of the country.” [6]

In the Russian Empire

During the Russian-Turkish War of 1787–1792, on 25 September 1789, a detachment of Russian forces under Ivan Gudovich took Khadjibey and Yeni Dünya for the Russian Empire. One part of the troops came under command of a Spaniard in Russian service, Major General José de Ribas (known in Russia as Osip Mikhailovich Deribas), and the main street in Odessa today, Deribasivska Street, is named after him. Russia formally gained possession of the area as a result of the Treaty of Jassy (Iaşi) in 1792 and it became a part of Novorossiya ("New Russia").

The city of Odessa, founded by order of Catherine the Great, Russian Empress, centers on the site of the Turkish fortress Khadzhibei, which was occupied by Russian Army in 1789. De Ribas and Franz de Volan recommended the area of Khadzhibei fortress as the site for the region's basic port: it had an ice-free harbor, breakwaters could be cheaply constructed and would render the harbor safe and it would have the capacity to accommodate large fleets. The Governor General of Novorossiya, Platon Zubov (one of Catherine's favorites) supported this proposal, and in 1794 Catherine approved the founding of the new port-city and invested the first money in constructing the city.

However, adjacent to the new official locality, a Moldavian colony already existed, which by the end of the 18th century was an independent settlement known under the name of Moldavanka. Some local historians consider that the settlement predates Odessa by about thirty years and assert that the locality was founded by Moldavians who came to build the fortress of Yeni Dunia for the Ottomans and eventually settled in the area in the late 1760s, right next to the settlement of Khadjibey (since 1795 Odessa proper), on what later became the Primorsky Boulevard. Another version posits that the settlement appeared after Odessa itself was founded, as a settlement of Moldavians, Greeks and Albanians fleeing the Ottoman yoke.[7]

In their settlement, also known as Novaya Slobodka, the Moldavians owned relatively small plots on which they built village-style houses and cultivated vineyards and gardens. What became Mykhailovsky Square was the center of this settlement and the site of its first Orthodox church, the Church of the Dormition, built in 1821 close to the seashore, as well as of a cemetery. Nearby stood the military barracks and the country houses (dacha) of the city's wealthy residents, including that of the Duc de Richelieu, appointed by Tzar Alexander I as Governor of Odessa in 1803.

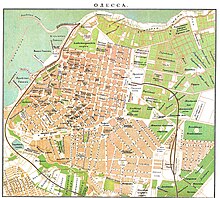

In the period from 1795 to 1814 the population of Odessa increased 15 times over and reached almost 20 thousand people. The first city plan was designed by the engineer F. Devollan in the late 18th century.[3] Colonists of various ethnicities settled mainly in the area of the former colony, outside of the official boundaries, and as a consequence, in the first third of the 19th century, Moldavanka emerged as the dominant settlement. After planning by the official architects who designed buildings in Odessa's central district, such as the Italians Francesco Carlo Boffo and Giovanni Torricelli, Moldovanka was included in the general city plan, though the original grid-like plan of Moldovankan streets, lanes and squares remained unchanged.[7]

The new city quickly became a major success despite the fact that initially it did get little state funding and privileges.[8] Its early growth owed much to the work of the Duc de Richelieu, who served as the city's governor between 1803 and 1814. Having fled the French Revolution, he had served in Catherine's army against the Turks. He is credited with designing the city and organizing its amenities and infrastructure, and is considered[by whom?] one of the founding fathers of Odessa, together with another Frenchman, Count Andrault de Langeron, who succeeded him in office. Richelieu is commemorated by a bronze statue, unveiled in 1828 to a design by Ivan Martos. His contributions to the city are mentioned by Mark Twain in his travelogue Innocents Abroad: "I mention this statue and this stairway because they have their story. Richelieu founded Odessa – watched over it with paternal care – labored with a fertile brain and a wise understanding for its best interests – spent his fortune freely to the same end – endowed it with a sound prosperity, and one which will yet make it one of the great cities of the Old World".

In 1819 the city became a free port, a status it retained until 1859. It became home to an extremely diverse population of Albanians, Armenians, Azeris, Bulgarians, Crimean Tatars, Frenchmen, Germans (including Mennonites), Greeks, Italians, Jews, Poles, Romanians, Russians, Turks, Ukrainians, and traders representing many other nationalities (hence numerous "ethnic" names on the city's map, for example Frantsuzky (French) and Italiansky (Italian) Boulevards, Grecheskaya (Greek), Yevreyskaya (Jewish), Arnautskaya (Albanian) Streets). Its cosmopolitan nature was documented by the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, who lived in internal exile in Odessa between 1823 and 1824. In his letters he wrote that Odessa was a city where "the air is filled with all Europe, French is spoken and there are European papers and magazines to read".

Odessa's growth was interrupted by the Crimean War of 1853–1856, during which it was bombarded by British and French naval forces.[9] It soon recovered and the growth in trade made Odessa Russia's largest grain-exporting port. In 1866 the city was linked by rail with Kiev and Kharkiv as well as with Iaşi in Romania.

The city became the home of a large Jewish community during the 19th century, and by 1897 Jews were estimated to comprise some 37% of the population. They were, due to interethnic conflict that had existed throughout the 19th century, repeatedly subjected to anti-Jewish backlash. Pogroms were carried out in 1821, 1859, 1871, 1881 and 1905. Many Odessan Jews fled abroad, particularly to Ottoman Palestine after 1882, and the city became an important base of support for Zionism.

Beginnings of revolution

In 1905 Odessa was the site of a workers' uprising supported by the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin (also see Battleship Potemkin uprising) and Lenin's Iskra. Sergei Eisenstein's famous motion picture The Battleship Potemkin commemorated the uprising and included a scene where hundreds of Odessan citizens were murdered on the great stone staircase (now popularly known as the "Potemkin Steps"), in one of the most famous scenes in motion picture history. At the top of the steps, which lead down to the port, stands a statue of the Duc de Richelieu. The actual massacre took place in streets nearby, not on the steps themselves, but the film caused many to visit Odessa to see the site of the "slaughter". The "Odessa Steps" continue to be a tourist attraction in Odessa. The film was made at Odessa's Cinema Factory, one of the oldest cinema studios in the former Soviet Union.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 during World War I, Odessa was occupied by several groups, including the Ukrainian Tsentral'na Rada, the French Army, the Red Army and the White Army. In 1918, Odessa became the capital of the independent Odessa Soviet Republic. Finally, in 1920, the Red Army took control of the city and united it with the Ukrainian SSR, which later became part of the USSR.

The people of Odessa badly suffered from a famine that occurred as a result of the Civil War in Russia in 1921–1922.

World War II

Before being occupied by Romanian troops in 1941, a part of the city's population, industry, infrastructure and all cultural valuables possible were evacuated to inner regions of the USSR and the retreating Red Army units destroyed as much as they could of Odessa harbour facilities left behind. The city was land mined in the same way as Kiev.[citation needed]

During World War II, from 1941–1944, Odessa was subject to Romanian administration, as the city had been made part of Transnistria.[10]

Following the Siege of Odessa, and the Axis occupation, approximately 25,000 Odessans were murdered in the outskirts of the city and over 35,000 deported; this came to be known as the Odessa Massacre. Most of the atrocities were committed during the first six months of the occupation which officially began on 17 October 1941, when 80% of the 210,000 Jews in the region were killed.[11] After the Nazi forces began to lose ground on the Eastern Front, the Romanian administration changed its policy, refusing to deport the remaining Jewish population to extermination camps in German occupied Poland, and allowing Jews to work as hired labourers. As a result, despite the tragic events of 1941, the survival of the Jewish population in this area was higher than in other areas of occupied eastern Europe.[11]

The city suffered severe damage and sustained many casualties over the course of the war. Many parts of Odessa were damaged during both its siege and recapture on 10 April 1944, when the city was finally liberated by the Red Army. It was one of the first four Soviet cities to be awarded the title of "Hero City" in 1945, though some of the Odessans had a more favourable view of the Romanian occupation, in contrast with the Soviet official view that the period was exclusively a time of hardship, deprivation, oppression and suffering – claims embodied in public monuments and disseminated through the media to this day.[12] Subsequent Soviet policies imprisoned and executed numerous Odessans (and deported most of the German and Tatar population) on account of collaboration with the occupiers.[13]

Since the Second World War

During the 1960s and 1970s the city grew tremendously. Nevertheless, the majority of Odessa's Jews emigrated to Israel, the United States and other Western countries between the 1970s and 1990s. Many ended up in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Brighton Beach, sometimes known as "Little Odessa". Domestic migration of the Odessan middle and upper classes to Moscow and Leningrad, cities that offered even greater opportunities for career advancement, also occurred on a large scale. Despite this, the city grew rapidly by filling the void of those left with new migrants from rural Ukraine and industrial professionals invited from all over the Soviet Union.

As a part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the city preserved and somewhat reinforced its unique cosmopolitan mix of Russian/Ukrainian/Jewish culture and a predominantly Russophone environment with the uniquely accented dialect of Russian spoken in the city. The city's unique identity has been formed largely thanks of its varied demography; all the city's communities have influenced aspects of Odessan life in some way or form.

Odessa is a city of more than 1 million people. The city's industries include shipbuilding, oil refining, chemicals, metalworking and food processing. Odessa is also a Ukrainian naval base and home to a fishing fleet. It is known for its large outdoor market – the Seventh-Kilometer Market, the largest of its kind in Europe.

The city has seen violence in the 2014 pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine. The 2 May 2014 Odessa clashes between pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian protestors killed 42 people. Four were killed during the protests, and at least 32 protesters were killed after a trade union building was set on fire.[14] Polls conducted from September to December 2014 found little support for joining Russia.[15][16]

Odessa was struck by three bomb blasts in December 2014, one of which killed one person (the injuries sustained by the victim indicated that he had dealt with explosives).[17][18] Internal Affairs Ministry advisor Zorian Shkiryak said on 25 December that Odessa and Kharkiv had become "cities which are being used to escalate tensions" in Ukraine. Shkiryak said that he suspected that these cities were singled out because of their "geographic position".[17] On 5 January 2015 the city's Euromaidan Coordination Center and a cargo train car were (non-lethally) bombed.[19]

Geography

Location

Odessa is situated (46°28′N 30°44′E / 46.467°N 30.733°E) on terraced hills overlooking a small harbor on the Black Sea in the Gulf of Odessa, approximately 31 km (19 mi) north of the estuary of the Dniester river and some 443 km (275 mi) south of the Ukrainian capital Kiev. The average elevation at which the city is located is around 50 metres, whilst the maximum is 65 and minimum (on the coast) amounts to 4.2 metres (13.8 feet) above sea level. The city currently covers a territory of 163 km2 (63 sq mi), the population density for which is around 6,139 persons/km². Sources of running water in the city include the Dniester River, from which water is taken and then purified at a processing plant just outside of the city. Being located in the south of Ukraine, the geography of the area surrounding the city is typically flat and there are no large mountains or hills for many kilometres around. Flora is of the deciduous variety and Odessa is famous for its beautiful tree-lined avenues which, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, made the city a favourite year-round retreat for the Russian aristocracy. [citation needed]

The city's location on the coast of the Black Sea has also helped to create a booming tourist industry in Odessa. [citation needed] The city's famous Arkadia beach has long been a favourite place for relaxation, both for the city's inhabitants and its many visitors. This is a large sandy beach which is located to the south of the city centre. Odessa's many sandy beaches are considered to be quite unique in Ukraine, as the country's southern coast (particularly in the Crimea) tends to be a location in which the formation of stoney and pebble beaches has proliferated.

Climate

Odessa has a warm temperate climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa)[20] near the borderline of the continental climate (Dfa) and the semi-arid climate (BSk). This has, over the past few centuries, aided the city greatly in creating conditions necessary for the development of tourism. During the tsarist era, Odessa's climate was considered to be beneficial for the body, and thus many wealthy but sickly persons were sent to the city in order to relax and recuperate. This resulted in the development of a spa culture and the establishment of a number of high-end hotels in the city. The average annual temperature of sea is 13–14 °C (55–57 °F), whilst seasonal temperatures range from an average of 6 °C (43 °F) in the period from January to March, to 23 °C (73 °F) in August. Typically, for a total of 4 months – from June to September – the average sea temperature in the Gulf of Odessa and city's bay area exceeds 20 °C (68 °F).[21] The city typically experiences dry, relatively mild winters, which are marked by temperatures which rarely fall below −3 degrees Celsius. Summers on the other hand do see an increased level of precipitation, and the city often basks in warm weather with temperatures often reaching into the high 20s and mid-30s. Snow cover is often only light, and municipal services rarely experience the same problems that can often be found in other, more northern, Ukrainian cities. This is largely because the higher winter temperatures and coastal location of Odessa prevent significant snowfall. Additionally the city does not suffer from the phenomenon of river-freezing.

| Climate data for Odessa (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

39.3 (102.7) |

38.0 (100.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

30.5 (86.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

39.3 (102.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.7 (36.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

17.2 (63.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

5.7 (42.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.2 (−15.2) |

−28.0 (−18.4) |

−16.0 (3.2) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

0.3 (32.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−28.0 (−18.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 34 (1.3) |

37 (1.5) |

32 (1.3) |

27 (1.1) |

36 (1.4) |

49 (1.9) |

47 (1.9) |

39 (1.5) |

41 (1.6) |

35 (1.4) |

41 (1.6) |

35 (1.4) |

453 (17.8) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 122 |

| Average snowy days | 11 | 10 | 6 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 4 | 9 | 41 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 81 | 78 | 74 | 71 | 70 | 66 | 65 | 72 | 77 | 82 | 84 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 77.5 | 81.9 | 124.0 | 186.0 | 263.5 | 291.0 | 313.1 | 300.7 | 240.0 | 170.5 | 78.0 | 55.8 | 2,182 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: HKO (sun 1961–1990)[23] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Ukrainians make up a majority (62 percent) of Odessa's inhabitants, and there is also a large and well established ethnic Russian minority (29 percent),[24] with a strong diaspora thriving in the colony of New Russia that was established at the end of the 18th century. Despite the increasing status of the Ukrainian language, the primary language spoken in the city continues to be Russian.

The city is also home to a number of other nationalities and minority ethnic groups, in addition to the city's majority Ukrainian population; including, Albanians, Armenians, Azeris, Crimean Tatars, Bulgarians, Georgians, Greeks, Jews, Romanians, Turks, among others. Up until the early 1940s the city also had a large Jewish population. As the result of mass deportation to extermination camps during the Second World War, the city's Jewish population declined considerably. Since the 1970s, the majority of the remaining Jewish population emigrated to Israel and other countries, shrinking the Jewish community.

Through most of the 19th century and until the mid 20th century the largest ethnic group in Odessa was Russians, with the second largest ethnic group being the Jews.[25][26]

Government and administrative divisions

Whilst Odessa is the administrative centre of the Odessa Oblast (province), the city is also the main constituent of the Odessa Municipality. However, since Odessa is a city of oblast subordinance, this makes the city subject directly to the administration of the oblast's authorities, thus removing it from the responsibility of the municipality.

The city of Odessa is governed by a mayor and city council which work cooperatively to ensure the smooth-running of the city and procure its municipal bylaws. The city's budget is also controlled by the administration.

The mayoralty[27] plays the role of the executive in the city's municipal administration. Above all comes the mayor, who is elected, by the city's electorate, for four years in a direct election. Since 6 November 2010 this office has been held by Aleksei Kostusev, a chevalier (II class) of the Order of Merit. Kostusev had, up until his election as mayor of Odessa on 31 October 2010, held numerous positions in the city's Kyiv district administration and served as a member of the Verkhovna Rada. He is a member of the Party of Regions. There are five deputy mayors, each of which is responsible for a certain particular part of the city's public policy.

The City Council[28] of the city makes up the administration's legislative branch, thus effectively making it a city 'parliament' or rada. The municipal council is made up of 120 elected members,[29] who are each elected to represent a certain district of the city for a four-year term. The current council is the fifth in the city's modern history, and was elected in January 2011. In the regular meetings of the municipal council, problems facing the city are discussed, and annually the city's budget is drawn up. The council has seventeen standing commissions[30] which play an important role in controlling the finances and trading practices of the city and its merchants.

The territory of Odessa is divided into four administrative raions (districts):

- Kyivsky Raion (Template:Lang-uk)

- Malynovsky Raion (Template:Lang-uk)

- Prymorsky Raion (Template:Lang-uk)

- Suvorovsky Raion (Template:Lang-uk)

In addition, every raion has its own administration, subordinate to the Odessa City council, and with limited responsibilities.

Cityscape

Many of Odessa's buildings have, rather uniquely for a Ukrainian city, been influenced by the Mediterranean style of classical architecture. This is particularly noticeable in buildings built by architects such as the Italian Francesco Boffo, who in early 19th-century built a palace and colonnade for the Governor of Odessa, Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, the Potocki Palace and many other public buildings.

In 1887 one of the city's most well known architectural monuments was completed – the theatre, which still hosts a range of performances to this day; it is widely regarded as one of the world's finest opera houses. The first opera house was opened in 1810 and destroyed by fire in 1873. The modern building was constructed by Fellner and Helmer in neo-baroque; its luxurious hall was built in the rococo style. It is said that thanks to its unique acoustics even a whisper from the stage can be heard in any part of the hall. The theatre was projected along the lines of Dresden's famous Semperoper built in 1878, with its nontraditional foyer following the curvatures of the auditorium; the building's most recent renovation was completed in 2007.[31]

Odessa's most iconic symbol, the Potemkin Steps (Primorsky Stairs) is a vast staircase that conjures an illusion so that those at the top only see a series of large steps, while at the bottom all the steps appear to merge into one pyramid-shaped mass. The original 200 steps (now reduced to 192) were designed by Italian architect Francesco Boffo and built between 1837 and 1841. The steps were made famous by Sergei Eisenstein in his film, The Battleship Potemkin.

Most of the city's 19th-century houses were built of limestone mined nearby. Abandoned mines were later used and broadened by local smugglers. This created a gigantic complicated labyrinth of underground tunnels beneath Odessa, known as "catacombs". During World War II, the catacombs served as a hiding place for partisans. They are a now a great attraction for extreme tourists. Such tours, however, are not officially sanctioned and are dangerous because the layout of the catacombs has not been fully mapped and the tunnels themselves are unsafe. The tunnels are a primary reason why no subway system was ever built in Odessa.

Deribasivska Street, an attractive pedestrian avenue named after José de Ribas, the Spanish-born founder of Odessa and decorated Russian Navy Admiral from the Russo-Turkish War, is famous by its unique character and magnificent architecture. During the summer it is common to find large crowds of people leisurely sitting and talking on the outdoor terraces of numerous cafes, bars and restaurants, or simply enjoying a walk along the cobblestone street, which is not open to vehicular traffic and is kept shaded by the linden trees which line its route.[32] A similar streetscape can also be found in that of Primorsky Bulvar, a grand thoroughfare which runs along the edge of the plateau upon which the city is situated, and where many of the city's most beautiful, imposing buildings are to be found.

As one of the biggest on the Black Sea, Odessa's port is busy all year round. The Odessa Sea Port is located on an artificial stretch of Black Sea coast, along the north-western part of the Gulf of Odessa. The total shoreline length of Odessa's sea port is around 7.23 kilometres (4.49 mi). The port, which includes an oil refinery, container handling facility, passenger area and numerous areas for handling dry cargo, is lucky in that its work does not depend on seasonal weather; the harbour itself is defended from the elements by breakwaters. The port is able to handle up to 14 million tons of cargo and about 24 million tons of oil products annually, whilst its passenger terminal's can cater for around 4 million passengers a year at full capacity.[33]

Parks and gardens

There are a number of public parks and gardens in Odessa, amongst these are the Preobrazhensky, Gorky and Victory parks, the latter of which is an arboretum. The city is also home to a university botanical garden, which recently celebrated its 200th anniversary, and a number of other smaller gardens.

The City Garden, or Gorodskoy Sad, is perhaps the most famous of Odessa's gardens. Laid out in 1803 by Felix De Ribas (brother of the founder of Odessa, José de Ribas) on a plot of urban land he owned, the garden is located right in the heart of the city. When Felix decided that he was no longer able to provide enough money for the garden's upkeep, he decided to present it to the people of Odessa. The transfer of ownership took place on 10 November 1806. Nowadays the garden is home to a bandstand and is the traditional location for outdoor theatre in the summertime. Numerous sculptures can also be found within the grounds as well as a musical fountain, the waters of which are computer controlled to coordinate with the musical melody being played.

Odessa's largest park, Shevchenko Park (previously Alexander Park), was founded in 1875, during a visit to the city by Emperor Alexander II. The park covers an area of around 700 by 900 metres and is located near the centre of the city, on the side closest to the sea. Within the park there is a wide variety of cultural and entertainment facilities, wide pedestrian avenues and natural beauty. In the centre of the park one can find the local top-flight football team's Chornomorets Stadium, the Alexander Column and municipal observatory. The Baryatinsky Bulvar is popular for its route, which starts at the park's gate before winding its way along the edge of the coastal plateau. There are a number of monuments and memorials in the park, one of which is dedicated to the park's namesake, the Ukrainian national poet Taras Shevchenko.

Education

Odessa is home to several universities and other institutions of higher education. The city's best-known and most prestigious university is the Odessa 'I.I. Mechnikov' National University. This university is the oldest in the city and was first founded by an edict of Tsar Alexander II of Russia in 1865 as the Imperial Novorossiysk University. Since then the university has developed to become one of modern Ukraine's leading research and teaching universities, with staff of around 1,800 and total of thirteen academic faculties. Other than the National University, the city is also home to the 1921-inaugurated Odessa National Economic University, the Odessa National Medical University (founded 1900), the 1918-founded Odessa National Polytechnic University and the Odessa National Maritime University (established 1930).

In addition to these universities, the city is home to the Odessa Law Academy, the National Academy of Telecommunications and the Odessa National Maritime Academy. The last of these institutions is a highly specialised and prestigious establishment for the preparation and training of merchant mariners which sees around 1,000 newly qualified officer cadets graduate each year and take up employment in the merchant marines of numerous countries around the world. The South Ukrainian National Pedagogical University is also based in the city, this is one of the largest institutions for the preparation of educational specialists in Ukraine and is recognised as one of the country's finest of such universities.

In addition to all the state-run universities mentioned above, Odessa is also home to a large number of private educational institutes and academies which offer highly specified courses in a range of different subjects. These establishments, however, typically charge much higher fees than government-owned establishments and may not have hold the same level of official accreditation as their state-run peers. [citation needed]

With regard to primary and secondary education, Odessa has a large number of schools catering for all ages from kindergarten through to lyceum (final secondary school level) age. Most of these schools are state-owned and operated, and all schools have to be state-accredited in order to teach children.

Culture

Museums, art and music

The Odessa Museum of Western and Eastern Art is arguably Odessa's most important museum; it has large European collections from the 16–20th centuries along with the art from the East on display. There are paintings from Mignard, Hals, Teniers and Del Piombo. Also of note is the city's Alexander Pushkin Museum, which is dedicated to detailing the short time Pushkin spent in exile in Odessa, a period during which he continued to write. The poet also has a city street named after him, as well as a statue. [citation needed] Other museums in the city include the Odessa Archeological Museum, which is housed in a beautiful neoclassical building, the renowned Odessa Numismatics Museum, the Odessa Art Museum and the Odessa Museum of the Regional History.

Among the city's public sculptures, two sets of Medici lions can be noted, at the Vorontsov Palace[34] as well as the Starosinnyi Garden.[35]

Jacob Adler, the major star of the Yiddish theatre in New York and father of the actor, director and teacher Stella Adler, was born and spent his youth in Odessa. The most popular Russian show business people from Odessa are Yakov Smirnoff (comedian), Mikhail Zhvanetsky (legendary humorist writer, who began his career as a port engineer) and Roman Kartsev (comedian ru). Zhvanetsky's and Kartsev's success in the 1970s, along with Odessa's KVN team, contributed to Odessa's established status as "capital of Soviet humor", culminating in the annual Humoryna festival, carried out on and around the April Fools' Day. Odessa was also the home of the late Armenian painter Sarkis Ordyan (1918–2003), the Ukrainian painter Mickola Vorokhta and the Greek philologist, author and promoter of Demotic Greek Ioannis Psycharis (1854–1929). Yuri Siritsov, bass player of the Israeli Metal band PallaneX is originally from Odessa. Igor Glazer Production Manager Baruch Agadati (1895–1976), the Israeli classical ballet dancer, choreographer, painter, and film producer and director grew up in Odessa, as did Israeli artist and author Nachum Gutman (1898–1980). Israeli painter Avigdor Stematsky (1908–89) was born in Odessa.

Odessa produced one of the founders of the Soviet violin school, Pyotr Stolyarsky. It has also produced many musicians, including the violinists Nathan Milstein, David Oistrakh and Igor Oistrakh, Boris Goldstein, Zakhar Bron and pianists Sviatoslav Richter, Benno Moiseiwitsch, Vladimir de Pachmann, Shura Cherkassky, Emil Gilels, Maria Grinberg, Simon Barere, Leo Podolsky and Yakov Zak. (Note: Richter studied in Odessa but wasn't born there.)

The Odessa International Film Festival is also held in this city annually since 2010.

Literature

Poet Anna Akhmatova was born in Bolshoy Fontan near Odessa.[36] The city has produced many writers, including Isaac Babel, whose series of short stories, Odessa Tales, are set in the city. Other Odessites are the duo Ilf and Petrov, and Yuri Olesha. Vera Inber, a poet and writer, as well as the famous poet and journalist, Margarita Aliger were both born in Odessa. The Italian writer, slavist and anti-fascist dissident Leone Ginzburg was born in Odessa into a Jewish family, and then went to Italy where he grew up and lived.

One of the most prominent pre-war Soviet writers, Valentin Kataev, was born here and began his writing career as early as high school (gymnasia). Before moving to Moscow in 1922, he made quite a few acquaintances here, including Yury Olesha and Ilya Ilf (Ilf's co-author Petrov was in fact Kataev's brother, Petrov being his pen-name). Kataev became a benefactor for these young authors, who would become some of the most talented and popular Russian writers of this period. In 1955 Kataev became the first chief editor of the Youth (Template:Lang-ru), one of the leading literature magazines of the Ottepel of the 1950s and 1960s. [citation needed]

These authors and comedians played a great role in establishing the "Odessa myth" in the Soviet Union. Odessites were and are viewed in the ethnic stereotype as sharp-witted, street-wise and eternally optimistic. [citation needed] These qualities are reflected in the "Odessa dialect", which borrows chiefly from the characteristic speech of the Odessan Jews, and is enriched by a plethora of influences common for the port city. The "Odessite speech" became a staple of the "Soviet Jew" depicted in a multitude of jokes and comedy acts, in which a Jewish adherent served as a wise and subtle dissenter and opportunist, always pursuing his own well-being, but unwittingly pointing out the flaws and absurdities of the Soviet regime. The Odessan Jew in the jokes always "came out clean" and was, in the end, a lovable character – unlike some of other jocular nation stereotypes such as The Chukcha, The Ukrainian, The Estonian or The American.[37]

Frank Cass, the founder of Frank Cass & Co. was a noted publisher in United Kingdom, specialising in the social sciences and humanities subject areas and publishing military and strategic studies titles and journals, until bought by Taylor & Francis Publishers on 28 July 2003.[38] He was the unofficial publisher of the Anglo-Jewish community, and retained the Vallentine Mitchell Publisher even after the sale of Frank Cass & Co.[39]

Resorts and health care

Odessa is a popular tourist destination, with many therapeutic resorts in and around the city. The city's Filatov Institute of Eye Diseases & Tissue Therapy is one of the world's leading ophthalmology clinics.

Other notable Odessans

Ze'ev Jabotinsky was born in Odessa, and largely developed his version of Zionism there in the early 1920s.[40] One Marshal of the Soviet Union, Rodion Yakovlevich Malinovsky, a military commander in World War II and Defense Minister of the Soviet Union, was born in Odessa, whilst renowned Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal lived in the city at one time.

Georgi Rosenblum, who was employed by William Melville as one of the first spies of the British Secret Service Bureau, was a native Odessan. Another intelligence agent from Odessa was Genrikh Lyushkov, who joined in the Odessa Cheka in 1920 and reached two-star rank in the NKVD before fleeing to Japanese-occupied Manchuria in 1938 to avoid being murdered.

The composer Jacob Weinberg (1879–1956) was born in Odessa. He composed over 135 works and was the founder of the Jewish National Conservatory in Jerusalem before immigrating to the U.S. where he became "an influential voice in the promotion of American Jewish music".[41]

Valeria Lukyanova, a girl from Odessa, who looks very similar to a Barbie doll, become a sensation on Internet and other media for her doll-like appearance.[42][43][44][45]

Economy

The economy of Odessa largely stems from its traditional role as a port city. The nearly ice-free port lies near the mouths of the Dnieper, the Southern Bug, the Dniester and the Danube rivers, which provide good links to the hinterland.[46] During the Soviet period (until 1991) the city functioned as the USSR's largest trading port; it continues in a similar role as independent Ukraine's busiest international port. The port complex contains an oil and gas transfer and storage facility, a cargo-handling area and a large passenger port. In 2007 the Port of Odessa handled 31,368,000 tonnes of cargo.[47][48] The port of Odessa is also one of the Ukrainian Navy's most important bases on the Black Sea. Rail transport is another important sector of the economy in Odessa – largely due to the role it plays in delivering goods and imports to and from the city's port.

Industrial enterprises located in and around the city include those dedicated to fuel refinement, machine building, metallurgy, and other types of light industry such as food preparation, timber plants and chemical industry. Agriculture is a relatively important sector in the territories surrounding the city. The Seventh-Kilometer Market is a major commercial complex on the outskirts of the city where private traders now operate one of the largest market complexes in Eastern Europe.[49] The market has roughly 6,000 traders and an estimated 150,000 customers per day. Daily sales, according to the Ukrainian periodical Zerkalo Nedeli, were believed to be as high as USD 20 million in 2004. With a staff of 1,200 (mostly guards and janitors), the market is also the region's largest employer. It is owned by local land and agriculture tycoon Viktor A. Dobriansky and three partners of his. Tavria-V is the most popular retail chain in Odessa. Key areas of business include: retail, wholesale, catering, production, construction and development, private label. Consumer recognition is mainly attributed[by whom?] to the high level of service and the quality of services. Tavria-V is the biggest private company and the biggest tax payer.

Deribasivska Street is one of the city's most important commercial streets, hosting a large number of the city's boutiques and higher-end shops. In addition to this there are a number of large commercial shopping centres in the city. The 19th-century shopping gallery Passage was, for a long time, the city's most upscale shopping district, and remains to this day[update] an important landmark of Odessa.

The tourism sector is of great importance to Odessa, which is currently[when?] the second most-visited Ukrainian city.[50] In 2003 this sector recorded a total revenue of 189,2 mln UAH. Other sectors of the city's economy include the banking sector: the city hosts a branch of the National Bank of Ukraine. Imexbank, one of Ukraine's largest commercial banks, is based in the city. Foreign business ventures have thrived in the area, as since 1 January 2000, much of the city and its surrounding area has been declared[by whom?] a free economic zone – this has aided the foundation of foreign companies' and corporations' Ukrainian divisions and allowed them to more easily invest in the Ukrainian manufacturing and service sectors. To date a number of Japanese and Chinese companies, as well as a host of European enterprises, have invested in the development of the free economic zone, to this end private investors in the city have invested a great deal of money into the provision of quality office real estate and modern manufacturing facilities such as warehouses and plant complexes.

Scientists

A number of world-famous scientists have lived and worked in Odessa. They include: Illya Mechnikov (Nobel Prize in Medicine 1908),[51] Igor Tamm (Nobel Prize in Physics 1958), Selman Waksman (Nobel Prize in Medicine 1952), Dmitri Mendeleev, Nikolay Pirogov, Ivan Sechenov, Vladimir Filatov, Nikolay Umov, Leonid Mandelstam, Aleksandr Lyapunov, Mark Krein, Alexander Smakula, Waldemar Haffkine, Valentin Glushko, and George Gamow.[52]

Transport

Maritime transport

Passenger ships and ferries connect Odessa with Istanbul, Haifa and Varna, whilst river cruises can occasionally be booked for travel up the Dnieper River to cities such as Kherson, Dnipropetrovsk and Kiev.

Roads and automotive transport

The first car in Russian Empire, a Mercedes-Benz belonging to V. Navrotsky, came to Odessa from France in 1891. He was a popular city publisher of the newspaper The Odessa Leaf.

Odessa is linked to the Ukrainian capital, Kiev, by the M05 Highway, a high quality multi-lane road which is set to be re-designated, after further reconstructive works, as an 'Avtomagistral' (motorway) in the near future. Other routes of national significance, passing through Odessa, include the M16 Highway to Moldova, M15 to Izmail and Romania, and the M14 which runs from Odessa, through Mykolaiv and Kherson to Ukraine's eastern border with Russia. The M14 is of particular importance to Odessa's maritime and shipbuilding industries as it links the city with Ukraine's other large deep water port Mariupol which is located in the south east of the county.

Odessa also has a well-developed system of inter-urban municipal roads and minor beltways. However, the city is still lacking an extra-urban bypass for transit traffic which does not wish to proceed through the city centre.

Intercity bus services are available from Odessa to many cities in Russia (Moscow, Rostov-on-Don, Krasnodar, Pyatigorsk), Germany (Berlin, Hamburg and Munich), Greece (Thessaloniki and Athens), Bulgaria (Varna and Sofia) and several cities of Ukraine and Europe.

Railways

Odessa is served by a number of railway stations and halts, the largest of which is Odesa Holovna (Main Station), from where passenger train services connect Odessa with Warsaw, Prague, Bratislava, Vienna, Berlin, Moscow, St. Petersburg, the cities of Ukraine and many other cities of the former USSR. The city's first railway station was opened in the 1880s, however, during the Second World War, the iconic building of the main station, which had long been considered to be one of the Russian Empire's premier stations, was destroyed through enemy action. In 1952 the station was rebuilt to the designs of A Chuprina. The current station, which is characterised by its many socialist-realist architectural details and grand scale, was renovated by the state railway operator Ukrainian Railways in 2006.

Public transport

Odessa was the first city in Imperial Russia to have steam tramway lines in 1881, an innovation which came only one year after the establishment of horse tramway services in 1880 operated by the "Tramways d'Odessa", a Belgian owned company. The first metre gauge steam tramway line ran from Railway Station to Great Fontaine and the second one to Hadzhi Bey Liman. These routes were both operated by the same Belgian company. Electric tramway started to operate on 22 August 1907. Trams were imported from Germany.

The city's public transit system is currently made up of trams,[53] trolleybuses, buses and fixed-route taxis (marshrutkas). Odessa also has a cable car and recreational ferry service.

One additional mode of transport in Odessa is quite unique; the Potemkin Stairs funicular railway, which runs between the city's Primorsky Bulvar and the sea terminal, has been in service since 1902. In 1998, after many years of neglect, the city decided to raise funds for a replacement track and cars; this project was delayed and on multiple occasions and was finally completed eight years later, in 2005. The funicular has now become as much a part of historic Odessa as the staircase parallel to which it runs.

Air transport

Odessa International Airport, which is located to the south-west of the city centre, is served by a number of airlines. The airport is also often used by citizens of neighbouring countries for whom Odessa is the nearest large city and who can travel visa-free to Ukraine.

Transit flights from the Americas, Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East to Odessa are offered by Ukraine International Airlines through their hub at Kiev's Boryspil International Airport. Additionally Turkish Airlines wide network and daily flights offers more than 246 destinations all over the world.

Sport

The most popular sport in Odessa is football. The main professional football club in the city is FC Chornomorets Odesa, who play in the Ukrainian Premier League. Chornomorets play their home games at the Chornomorets Stadium, an elite-class stadium which has a maximum capacity of 34,164. The second football team in Odessa is FC Odessa.

Basketball is also a prominent sport in Odessa, with BC Odessa representing the city in the Ukrainian Basketball League, the highest tier basketball league in Ukraine. Odessa will become one of five Ukrainian cities to host the 39th European Basketball Championship in 2015.

Athletes

Chess player Efim Geller was born in the city. Gymnast Tatiana Gutsu (known as "The Painted Bird of Odessa") brought home Ukraine's first Olympic gold medal as an independent nation when she outscored the USA's Shannon Miller in the women's all-around event at 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, Spain. Figure skaters Oksana Grishuk and Evgeny Platov won the 1994 and 1998 Olympic gold medals as well as the 1994, 1995, 1996, and 1997 World Championships in ice dance. Both were born and raised in the city, though they skated at first for the Soviet Union, the Unified Team, the Commonwealth of Independent States, and then Russia. Hennadiy Avdyeyenko won 1988 Olympic gold medal in high jump, setting an olympic record at 2,38 m.

Other notable athletes:

- Mykola Avilov, Olympic champion in decathlon at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich

- Oksana Baiul, Olympic champion in figure skating

- Ihor Belanov, European Footballer of the Year in 1986

- Yuriy Bilonoh, European Athletics Championships in shot put at 2002 in Munich

- Leonid Buryak, football coach and former Olympic bronze-medal-winning player

- Maksim Chmerkovskiy, professional ballroom & Latin dancer on American Dancing With the Stars

- Valentin Chmerkovskiy, professional ballroom & Latin dancer on American Dancing With the Stars

- Charles Goldenberg, NFL football player

- Svetlana Krachevskaya, Olympic silver medalist in shot put

- Viacheslav Kravtsov, NBA basketball player

- Lenny Krayzelburg, Olympic champion swimmer

- Artur Kyshenko, K1 Muay Thai kickboxer

- Roman Pelts, Soviet chess master

- Viktor Petrenko, Olympic champion in figure skating

- Vladimir Portnoi, Olympic silver and bronze medalist in gymnastics

- Vitaliy Pushkar, racing driver, No. 6 in 2012 International Rally Challenge Production cup standings[54]

- Ekaterina Rubleva, Russian ice dancing champion

- Dmitry Salita, boxer

- Solomon Trestin, boxer

- Olena Vitrychenko, world champion in rhythmic gymnastics

- Theodore Rezvoy, Ocean Rower, traveller, Guinness records holder (twice)

- Yakov Zheleznyak, Olympic champion in 50 m Running Target at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich

- Yevgeny Lapinsky, Olympic champion in volleyball at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico

- Yulia Ryabchinskaya, Olympic champion in the K-1 500 m Kayak Singles at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Odessa is twinned, has sister and partner relationships with many other cities throughout the world:

Alexandria, Egypt, (since 1968)

Alexandria, Egypt, (since 1968) Baltimore, United States, (since 1975)[55]

Baltimore, United States, (since 1975)[55] Chişinău, Moldova, (since 1994)[56]

Chişinău, Moldova, (since 1994)[56] Constanţa, Romania, (since 1991)

Constanţa, Romania, (since 1991) Gdańsk, Poland

Gdańsk, Poland Genoa, Italy, (since 1972)

Genoa, Italy, (since 1972) Haifa, Israel, (since 1992)[57]

Haifa, Israel, (since 1992)[57] Istanbul, Turkey, (since 1997)[58][59]

Istanbul, Turkey, (since 1997)[58][59] Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Kolkata, India, (since 1986)[60]

Kolkata, India, (since 1986)[60] León, Mexico, (since 2012)

León, Mexico, (since 2012) Liverpool, United Kingdom, (since 1957)[61]

Liverpool, United Kingdom, (since 1957)[61] Łódź, Poland, (since 1993)[62]

Łódź, Poland, (since 1993)[62] Marseille, France, (since 1973)[63]

Marseille, France, (since 1973)[63] Nicosia, Cyprus, (since 1996)

Nicosia, Cyprus, (since 1996) Oulu, Finland, (since 1957)[64]

Oulu, Finland, (since 1957)[64] Piraeus, Greece, (since 1993)[65]

Piraeus, Greece, (since 1993)[65] Qingdao, China, (since 1993)

Qingdao, China, (since 1993) Regensburg, Germany, (since 1990)

Regensburg, Germany, (since 1990) Rosh HaAyin, Israel

Rosh HaAyin, Israel Rostov-on-Don, Russia, (since 1999)

Rostov-on-Don, Russia, (since 1999) Split, Croatia, (since 1964)[66]

Split, Croatia, (since 1964)[66] Szeged, Hungary, (since 1977)

Szeged, Hungary, (since 1977) Valencia, Spain, (since 1982)[67]

Valencia, Spain, (since 1982)[67] Van, Turkey

Van, Turkey Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, (since 1944)[68]

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, (since 1944)[68] Varna, Bulgaria (since 1958)

Varna, Bulgaria (since 1958) Yerevan, Armenia (since 1995)[69][70]

Yerevan, Armenia (since 1995)[69][70] Yokohama, Japan (since 1968)[71]

Yokohama, Japan (since 1968)[71]

Partner cities

Brest, Belarus (since 2004)[72]

Brest, Belarus (since 2004)[72] Gdansk, Poland (since 1996)[73]

Gdansk, Poland (since 1996)[73] Heraklion, Crete (since 1992)

Heraklion, Crete (since 1992) Klaipeda, Lithuania (since 2004)

Klaipeda, Lithuania (since 2004) Larnaca, Cyprus (since 2004)[65]

Larnaca, Cyprus (since 2004)[65]

Minsk, Belarus (since 1996)

Minsk, Belarus (since 1996) Moscow, Russia (since 1995)

Moscow, Russia (since 1995) Ningbo, China (since 2008)

Ningbo, China (since 2008) Saint Petersburg, Russia (since 2002)

Saint Petersburg, Russia (since 2002) Taganrog, Russia (since 1993)

Taganrog, Russia (since 1993) Tallinn, Estonia (since 1997)

Tallinn, Estonia (since 1997) Tbilisi, Georgia (since 1996)

Tbilisi, Georgia (since 1996) Valparaíso, Chile (since 2004)

Valparaíso, Chile (since 2004) Vienna, Austria (since 2006)

Vienna, Austria (since 2006) Volgograd, Russia (since 2001)

Volgograd, Russia (since 2001)

See also

References

- ^ http://en.itar-tass.com/world/733526

- ^ Herlihy, Patricia (1977). "The Ethnic Composition of the City of Odessa in the Nineteenth Century": g. 53.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Odessa: Architecture and Monuments". 2009 UKRWorld.Com. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=LcfLKHVi2UUC&pg=PA254

- ^ “The Greek Colonisation of the Black Sea Area: Historical Interpretation of Archaeology,” December 1998, Tsetskhladze, Gocha R. (ed.), Franz Steiner Verlag, p. 41, n. 116.

- ^ http://www.lifebeyondtourism.org/magazine/273/Odessa%2C-the-Last-Italian-Black-Sea-Colony

- ^ a b Richardson, p. 110.

- ^ Odesa: Through Cossacks, Khans and Russian Emperors, The Ukrainian Week (18 November 2014)

- ^ Clive Pointing, The Crimean War: The Truth Behind the Myth, Chatto & Windus, London, 2004, ISBN 0-7011-7390-4.

- ^ Nataliya and Yuri Kruglyak, KRT Web Studio at www.webservicestudio..com , Odessa, Ukraine. "Odessa population during WWII". Odessitclub.org. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Richardson, p. 33.

- ^ Richardson, p. 103.

- ^ Richardson, p. 17.

- ^ Canada (2 May 2014). "At least 35 killed in Odessa, Ukraine, as building set on fire". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Лише 3% українців хочуть приєднання їх області до Росії". Dzerkalo Tyzhnia (in Ukrainian). 3 January 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Two dead after Ukraine rocked by series of blasts, Mashable (28 December 2014)

Interior minister's advisor says Kharkiv, Odesa explosions aim at escalating tensions in Ukraine, Interfax-Ukraine (25 December 2014) - ^ Bomb Explosion in Odessa Could Have Targeted Ukraine Army Charity Point, The Moscow Times (10 December 2014)

Southern Ukraine: Blasts in Kherson, Odessa, Rt tv (27 December 2014) - ^ French Leader Urges End to Sanctions Against Russia Over Ukraine, New York Times (5 January 2015)

Latest Explosion in Odessa Strikes Pro-Ukraine Organization (Video), The Moscow Times (5 January 2015)

Mysterious bombing rocks Ukrainian port city of Odessa, Mashable (5 January 2015) - ^ "World Map of Köppen−Geiger Climate Classification" (PDF).

- ^ "Odessa Climate Guide". Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ Погода и Климат – Климат Одессы (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Retrieved 23 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Climatological Information for Odessa, Ukraine". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ "All-Ukrainian Census of 2001 Official Site" (in Ukrainian). 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ Дністрянський М.С. Этнополитическая география Украины = Етнополітична географія України. – Лівів: Літопис, видавництво ЛНУ імені Івана Франка, 2006. – С. 342. – ISBN 966-7007-60-X

- ^ "Данные Всесоюзной переписи населения 1926 года по регионам республик СССР". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Official Website of the city administration: Structure of the Mayorality". Odessa.ua. 1 April 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Official Website of the city administration: City Council". Odessa.ua. 14 July 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "City Council members". Odessa.ua. 1 April 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Official Website of the city administration, Standing commissions of the City Council". Odessa.ua. 1 April 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Buildings for Music, Michael Forsythe, Cambridge University Press, p. 344

- ^ http://www.odessaapartments.dompavlov.com/content/deribasovskaya/

- ^ http://www.odessaapartments.dompavlov.com/content/odessa-passage/

- ^ Commons:Category:Medici lions at Vorontsov palace in Odessa

- ^ Commons:File:Starosinnyi Garden.JPG

- ^ Anderson, Nancy K.; Anna Andreevna Akhmatova (2004). The word that causes death's defeat. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10377-8.

- ^ Tanny, Jarrod (2011). City of Rogues and Schnorrers: Russia's Jews and the Myth of Old Odessa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 13–22, 142–156. ISBN 978-0-253-22328-9.

- ^ Black, Gerry, Frank's way: Frank Cass and fifty years of publishing / Gerry Black Vallentine Mitchell, London; Portland, OR: 2008

- ^ Frank Cass: Eclectic publisher with an eye for opportunity, guardian.co.uk

- ^ Nissani, Noah. "Ze'ev Jabotinsky – Brief Biography". 1996 Liberal.Org. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ von Rhein, John (19 August 2005). "Jacob Weinberg: Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Major". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ Soldak, Katya. "Barbie Flu Spreading in Ukraine". Forbes.

- ^ Jackson, Kate. "Bizarre obsessions of real-life Barbie". The Sun. London.

- ^ Whitelocks, Sadie (1 February 2013). "Our childhood dreams shattered". Daily Mail. London.

- ^ "Живая Барби - Валерия Лукъянова".

- ^ Kravtsiv, Bohdan (2012). "Odesa". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

Odesa is situated on a large, virtually ice-free bay on the Black Sea, near the mouths of the Danube River, the Dnister River, the Boh River, and the Dnieper River, which link it with the interior of the country.

- ^ Ассоциация портов Украины и всего Чёрного моря: члены

- ^ Ports of Ukraine

- ^ "Одесса | о городе". Odessa-info.com.ua. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Schmalstieg, Frank C; Goldman Armond S (May 2008). "Ilya Ilich Metchnikoff (1845–1915) and Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915): the centennial of the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". Journal of Medical Biography. 16 (2). England: 96–103. doi:10.1258/jmb.2008.008006. PMID 18463079.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ George Gamow, My time-line, Viking, 1970, New York

- ^ "Odessa Tram Themes". Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- ^ ICR series drivers standings[dead link]

- ^ "Sister Cities". Baltimore Convention & Tourism Board. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "Oraşe înfrăţite (Twin cities of Minsk) [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Romanian). Primăria Municipiului Chişinău. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 3 September 2012 suggested (help) - ^ "Twin City activities". Haifa Municipality. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Istanbul". Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Erdem, Selim Efe (3 November 2003). "İstanbul'a 49 kardeş" (in Turkish). Radikal. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

49 sister cities in 2003

- ^ Mazumdar, Jaideep (17 November 2013). "A tale of two cities: Will Kolkata learn from her sister?". Times of India. New Delhi. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ "Liverpool City Council: twinning". Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "Miasta partnerskie – Urząd Miasta Łodzi [via WaybackMachine.com]". City of Łódź (in Polish). Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "Marseille Official Website – Twin Cities" (in French).

2008 Ville de Marseille. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

2008 Ville de Marseille. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ^ "Ystävyyskaupungit (Twin Cities)". Oulun kaupunki (City of Oulu) (in Finnish). Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Twinnings" (PDF). Central Union of Municipalities & Communities of Greece. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ "Gradovi prijatelji Splita". Grad Split [Split Official City Website] (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ciudades Hermanadas con València". Ajuntament de València [City of Valencia] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 29 October 2012 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Vancouver Twinning Relationships" (PDF). City of Vancouver. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Yerevan – Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Yerevan Municipality Official Website. 2005–2013 www.yerevan.am. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ ԵՐԵՎԱՆԻ ՔԱՂԱՔԱՊԵՏԱՐԱՆՊԱՇՏՈՆԱԿԱՆ ԿԱՅՔ (in Armenian). [2]. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Official Yokohama City Tourism Website: Sister Cities". Yokohama Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Побратимские связи г. Бреста (in Russian). City.brest.by. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ "Gdańsk Official Website: 'Miasta partnerskie'" (in Polish & English). 2009 Urząd Miejski w Gdańsku. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=

Bibliography

- Dallin, Alexander (1998). Odessa, 1941–1944: A Case Study of Soviet Territory Under Foreign Rule. Iaşi: Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-98391-1-8. Retrieved 7 November 2009. Complete book available online.

- Friedberg, Maurice (1991). How Things Were Done in Odessa: Cultural and Intellectual Pursuits in a Soviet City. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-7987-3. Two reviews

- Ghervas, Stella (2008). "Odessa et les confins de l'Europe: un éclairage historique". In Ghervas, Stella; Rosset, François (eds.). Lieux d'Europe. Mythes et limites. Paris: Editions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. ISBN 978-2-7351-1182-4.

- Ghervas, Stella (2008). Réinventer la tradition. Alexandre Stourdza et l'Europe de la Sainte-Alliance. Paris: Honoré Champion. ISBN 978-2-7453-1669-1.

- Gubar, Oleg (2004). Odessa: New Monuments, Memorial Plaques, and Buildings. Odessa: Optimum. ISBN 966-8072-86-3.

- Herlihy, Patricia (1977). "The Ethnic Composition of the City of Odessa in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 1 (1): 53–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008.

- Herlihy, Patricia (1979–1980). "Greek Merchants in Odessa in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). Harvard Ukrainian Studies. pp. 399–420. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008.

- Herlihy, Patricia (1987). Odessa: A History, 1794–1914. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-916458-15-6 (hardcover), ISBN 0-916458-43-1 (1991 paperback reprint).

- Herlihy, Patricia (2002). "Commerce and Architecture in Odessa in Late Imperial Russia". Commerce in Russian Urban Culture 1861–1914. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6750-9.

- Herlihy, Patricia (2003). "Port Jews of Odessa and Trieste: A Tale of Two Cities". Jahrbuch des Simon-Dubnow-Instituts. 2. München: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt: 182–198. ISBN 3-421-05522-X.

- Herlihy, Patricia; Gubar, Oleg (2008). "The Persuasive Power of the Odessa Myth". In Czaplicka, John; Gelazis, Nida; Ruble, Blair A. (eds.). Cities after the Fall of Communism: Reshaping Cultural Landscapes and European Identity. Woodrow Wilson Center Press and Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9191-5.

- Kaufman, Bel; Oleg Gubar (Contributor), Alexander Rozenboim (Contributor), Nicholas V. Iljine (Editor), Patricia Herlihy (Editor) (2004). Odessa Memories. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-98345-0.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - King, Charles (2011). Odessa: Genius and Death in a City of Dreams. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-07084-2.

- Kononova, G. (1984). Odessa: A Guide. Moscow: Raduga Publishers. OCLC 12344892.

- Makolkin, Anna (2004). A History of Odessa, the Last Italian Black Sea Colony. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-6272-4.

- Mazis, John Athanasios (2004). The Greeks of Odessa: Diaspora Leadership in Late Imperial Russia. East European Monographs. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-88033-545-9.

- Orbach, Alexander (1997). New Voices of Russian Jewry: A Study of the Russian-Jewish Press of Odessa in the Era of the Great Reforms, 1860–1871. Studies in Judaism in Modern Times, No. 4. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-06175-4.

- Richardson, Tanya (2008). Kaleidoscopic Odessa: History and Place in Contemporary Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-9563-1. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Rothstein, Robert A. (2001). "How It Was Sung in Odessa: At the Intersection of Russian and Yiddish Folk Culture". Slavic Review. 60 (4): 781–801. doi:10.2307/2697495. JSTOR 2697495.

- Skinner, Frederick W. (1986). "Odessa and the Problem of Urban Modernization". The City in Late Imperial Russia. Indiana–Michigan Series in Russian and East European Studies. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31370-8.

- Sylvester, Roshanna P. (2001). "City of Thieves: Moldavanka, Criminality, and Respectability in Prerevolutionary Odessa". Journal of Urban History. 27 (2): 131–157. doi:10.1177/009614420102700201. PMID 18333319.

- Tanny, Jarrod (2011). City of Rogues and Schnorrers: Russia’s Jews and the Myth of Old Odessa. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35646-8 (hardcover); ISBN 978-0-253-22328-9 (paperback).

- Weinberg, Robert (1992). "The Pogrom of 1905 in Odessa: A Case Study". Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40532-7.

- Weinberg, Robert (1993). The Revolution of 1905 in Odessa: Blood on the Steps. Indiana–Michigan Series in Russian and East European Studies. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-36381-0.

- Herlihy, Patricia (1994). "Review of The Revolution of 1905 in Odessa: Blood on the Steps by Robert Weinberg". Journal of Social History. 28 (2): 435–437. doi:10.1353/jsh/28.2.435. JSTOR 3788930.

- Zipperstein, Steven J. (1991) [1986]. The Jews of Odessa: A Cultural History, 1794–1881. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1251-4 (hardcover), ISBN 0-8047-1962-4 (paperback reprint).

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- "Official Odessa web page". Odessa Сity Сouncil, Information Dept. Russian, Ukrainian, and English versions

- "Official Odessa Map Portal". Russian, Ukrainian, and English versions of Maps

- "Map of the current public transport routes in Odessa". Russian, Ukrainian, and English versions

- "People wash Odessa. The clip was made to the 218th city day by Alexandr Milov".

- Walker, Shaun (13 July 2013). "Marriage, Ukrainian-style: Hopeful bachelors from all over the world head to Odessa in search of a wife". The Independent. London.

- Port cities of the Black Sea

- Cities in Odessa Oblast

- Kherson Governorate

- Former Russian and Soviet Navy bases

- Hero Cities of the Soviet Union

- Historic Jewish communities

- Historic Russian communities

- Jewish Ukrainian history