Effects of cannabis: Difference between revisions

UberMan5000 (talk | contribs) |

→Cancer risk: inserted crucial fact at beginning: smoke contains carcinogens |

||

| Line 119: | Line 119: | ||

=== Cancer risk === |

=== Cancer risk === |

||

A study published in 2006 <ref>{{cite web | title=Pot Smoking Not Linked to Lung Cancer | author= [[WebMD]] | date=23 May 2006 | url=http://www.webmd.com/content/article/122/114805.htm}} [http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2006/523/3 ScienceNOW], [http://www.drugwarrant.net/wiki/tiki-index.php?page=Marijuana_and_Cancer Abstract]</ref> on a large population sample (1,200 people with lung, neck, or head cancer, and a matching group of 1,040 without cancer) failed to positively correlate a [[lung cancer]] risk, in fact the results indicated a slight ''negative'' correlation between long and short-term cannabis use and cancer, suggesting a possible therapeutic effect. This followed an even larger [[1997]] study <ref>{{cite journal | title=Marijuana use and cancer incidence (California, United States) | author=S. Sidney | journal=Cancer Causes and Control | volume=8 | issue=5 | date=Sep 1997 | pages= 722-728 | url=http://www.springerlink.com/link.asp?id=l221477720240752}}</ref> examining the records of 64,855 Kaiser patients, which also found no positive correlation between cannabis use and cancer. It has been noted, separately, that [[THC]], a dilative agent, may help cleanse the lungs by dilating the bronchia, and could actively reduce the instance of tumors. <ref>{{cite journal | title=Antitumor Effects of THC | author= J. Huff & P. Chan | journal=Environmental Health Perspectives | volume= 108 | issue=10 | date= Oct 2000 | pages=A442-3 | url=http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/docs/2000/108-10/correspondence.html#thc}}</ref> Additionally, a study by Rosenblatt et al. found no association between marijuana use and the development of [[Head and neck cancer|head and neck squamous cell carcinoma]]. <ref>{{cite journal | title=Marijuana Use and Risk of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | author= K.A. Rosenblatt et al. | journal=Cancer Research | volume= 64 | date= 1 June 2004 | pages=4049-4054 | url=http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/64/11/4049}}</ref> |

Cannabis smoke contains numerous compounds known to cause cancer. Surprisingly, scientific studies have failed to show higher cancer rates in cannabis smokers. A study published in 2006 <ref>{{cite web | title=Pot Smoking Not Linked to Lung Cancer | author= [[WebMD]] | date=23 May 2006 | url=http://www.webmd.com/content/article/122/114805.htm}} [http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2006/523/3 ScienceNOW], [http://www.drugwarrant.net/wiki/tiki-index.php?page=Marijuana_and_Cancer Abstract]</ref> on a large population sample (1,200 people with lung, neck, or head cancer, and a matching group of 1,040 without cancer) failed to positively correlate a [[lung cancer]] risk, in fact the results indicated a slight ''negative'' correlation between long and short-term cannabis use and cancer, suggesting a possible therapeutic effect. This followed an even larger [[1997]] study <ref>{{cite journal | title=Marijuana use and cancer incidence (California, United States) | author=S. Sidney | journal=Cancer Causes and Control | volume=8 | issue=5 | date=Sep 1997 | pages= 722-728 | url=http://www.springerlink.com/link.asp?id=l221477720240752}}</ref> examining the records of 64,855 Kaiser patients, which also found no positive correlation between cannabis use and cancer. It has been noted, separately, that [[THC]], a dilative agent, may help cleanse the lungs by dilating the bronchia, and could actively reduce the instance of tumors. <ref>{{cite journal | title=Antitumor Effects of THC | author= J. Huff & P. Chan | journal=Environmental Health Perspectives | volume= 108 | issue=10 | date= Oct 2000 | pages=A442-3 | url=http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/docs/2000/108-10/correspondence.html#thc}}</ref> Additionally, a study by Rosenblatt et al. found no association between marijuana use and the development of [[Head and neck cancer|head and neck squamous cell carcinoma]]. <ref>{{cite journal | title=Marijuana Use and Risk of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma | author= K.A. Rosenblatt et al. | journal=Cancer Research | volume= 64 | date= 1 June 2004 | pages=4049-4054 | url=http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/64/11/4049}}</ref> |

||

Although the [[carcinogen|carcinogenicity]] of tobacco is thought to be caused mainly by tar, it has been suggested that it could be the result of [[Cigarette#Health effects|radioactive substances]] present in tobacco soils <ref>{{cite journal | title=Cancer risk in relation to radioactivity in tobacco | author= G.F. Kilthau | journal=Radiologic Technology | volume=67 | issue=3 | date= Jan-Feb 1996 | url=http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HWRC/hits?index1=RN&tcit=0_1_0_0_0&rlt=2&origSearch=true&t=RK&s=11&r=d&items=0&secondary=false&n=10&l=d&sgPhrase=true&c=1&bucket=per&text1=A19101062&docNum=A19101062&locID=nysl_me_weillmdc}}</ref>. This problem does not pertain to cannabis, the vast majority of which is grown in [[Cannabis (drug) cultivation#Cultivation Techniques|wild, organic, or hydroponic conditions]]. |

Although the [[carcinogen|carcinogenicity]] of tobacco is thought to be caused mainly by tar, it has been suggested that it could be the result of [[Cigarette#Health effects|radioactive substances]] present in tobacco soils <ref>{{cite journal | title=Cancer risk in relation to radioactivity in tobacco | author= G.F. Kilthau | journal=Radiologic Technology | volume=67 | issue=3 | date= Jan-Feb 1996 | url=http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HWRC/hits?index1=RN&tcit=0_1_0_0_0&rlt=2&origSearch=true&t=RK&s=11&r=d&items=0&secondary=false&n=10&l=d&sgPhrase=true&c=1&bucket=per&text1=A19101062&docNum=A19101062&locID=nysl_me_weillmdc}}</ref>. This problem does not pertain to cannabis, the vast majority of which is grown in [[Cannabis (drug) cultivation#Cultivation Techniques|wild, organic, or hydroponic conditions]]. |

||

Revision as of 08:41, 30 July 2006

There is today still a substantial amount of propaganda, junk science, and misinformation about cannabis; both from advocates of cannabis and from its opponents. There are also severe legal and political constraints on cannabis research.

Although there are many conflicting studies involving cannabis, certain physical and mental health effects have been concluded. This article utilizes a diversity of credible sources, mainly peer-reviewed articles from international medical journals but also scientific reports, textbooks, websites and magazines, to establish an overview of clearly documented outcomes associated with cannabis use.

Legal and political constraints on open research

In many countries, experimental science suffers from legal restrictions because cannabis is illegal. Thus, cannabis as a drug is often hard to fit into the structural confines of medical research because appropriate, research-grade samples are impossible to obtain legally for research purposes, unless granted under authority of national governments.

The phenomenon of legitimate scientific curiosity in conflict with governmental agenda was most recently exemplified in the United States by the clash between Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), an independent research group, versus the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), a federal agency charged with the application of science to the study of drug abuse. The NIDA largely operates under the general control of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), a White House office responsible for the direct coordination of all legal, legislative, scientific, social and political aspects of federal drug control policy.

The cannabis that is available for research studies in the United States is grown at the University of Mississippi and solely controlled by the NIDA, which even has veto power over the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to define accepted protocols. Since 1942, when cannabis was removed from the U.S. pharmacopoeia and its medical use was prohibited, there is no history of a legal (under federal law) privately funded cannabis production project. The result is that a very limited number of research opportunities take place, and these must use the product that NIDA produces, which has been alleged to be of very low potency and inferior quality. [1]

MAPS, in conjunction with Professor Lyle Craker, PhD, the director of the Medicinal Plant Program of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, sought to provide independently grown cannabis of more appropriate research quality for FDA-approved research studies and encountered much adversity by the NIDA, the ONDCP, and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). This project, and many others like it, have almost no chance in a legal terrain dominated by the American War on Drugs.

However in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, a license for growing marijuana is merely a matter of bureaucracy as long as it is for botanical or scientific reasons. Hence the phrase "controlled drug". In such countries, many tests have been performed for various reasons. More recently, several habitual smokers were invited to partake in various tests by British medical companies in order for the U.K. government to ascertain the influence of cannabis on operating a motor vehicle.

Biochemical effects

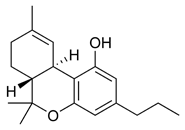

The most prevalent psychoactive substance in cannabis is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (commonly called Δ9-THC, or simply THC). In the past two decades, the average content of THC in marijuana sold in North America has increased from about 1% to 3-4% or more. Carefully selected and cloned plants can yield as much as 15% THC. [2] Another psychoactive cannabinoid present in Cannabis sativa is Tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), but it is only found in small amounts. In addition, there are also similar compounds contained in marijuana that do not exhibit any psychoactive response but are obligatory for functionality: Cannabidiol (CBD), an isomer of THC; Cannabinol (CBN), an oxidation product of THC; Cannabivarin (CBV), an analog of CBN with a different sidechain, Cannabidivarin (CBDV), an analog of CBD with a different sidechain, and Cannabinolic acid. How these other compounds interact with THC is not fully understood, but some clinical studies have proposed that CBD acts as a balancing force to regulate the strength of the psychoactive agent THC. Anecdotal but inconclusive reports claim that marijuana with relatively high ratios of THC:CBD is less likely to induce anxiety than marijuana with low THC:CBD ratios. [3] CBD is also believed to regulate the body’s metabolism of THC by inactivating cytochrome P450, an important class of enzymes that metabolize drugs. Experiments in which mice were treated with CBD followed by THC showed that CBD treatment was associated with a substantial increase in brain concentrations of THC and its major metabolites, most likely because it decreased the rate of clearance of THC from the body. [3] Cannabis cofactor compounds have also been linked to lowering body temperature, modulating immune functioning, and cell protection. The essential oil of cannabis also contains many fragrant terpenoids, which may synergize with the cannabinoids to produce their unique effects. THC is converted rapidly to 11-hydroxy-THC, which is also pharmacologically active, so the drug effect outlasts measurable THC levels in blood. [2]

In 1990, the discovery of cannabinoid receptors located throughout the brain and body, along with endogenous cannabinoid neurotransmitters like anandamide (a lipid material derived ligand from arachidonic acid), suggested that the use of marijuana affects the brain in the same manner as a naturally occurring brain chemical. Cannabinoids usually contain a 1,1'-di-methyl-pyrane ring, a variedly derivatized aromatic ring and a variedly unsaturated cyclohexyl ring and their immediate chemical precursors, constituting a family of about 60 bi-cyclic and tri-cyclic compounds. Like most other neurological processes, the effects of marijuana on the brain follow the standard protocol of signal transduction, the electrochemical system of sending signals through neurons for a biological response. It is now understood that cannabinoid receptors appear in similar forms in most vertebrates and invertebrates and have a long evolutionary history of 500 million years. The fact that these receptors have been conserved throughout this time indicates that they must have an important basic role in animal physiology. Cannabinoid receptors decrease adenylyl cyclase activity, inhibit calcium N channels, and disinhibit K+A channels. There are two types of cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2).

The CB1 receptor is found primarily in the brain and mediates the psychological effects of THC. The CB2 receptor is most abundantly found on cells of the immune system. Cannabinoids act as immunomodulators at CB2 receptors, meaning they increase some immune responses and decrease others. For example, nonpsychotrophic cannabinoids can be used as a very effective anti-inflammatory. [3] The affinity of cannabinoids to bind to either receptor is about the same, with only a slight increase observed with the plant-derived compound CBD binding to CB2 receptors more frequently. Cannabinoids likely have a role in the brain’s control of movement and memory, as well as natural pain modulation. It is clear that cannabinoids can affect pain transmission and, specifically, that cannabinoids interact with the brain's natural opioid system acting as a dopamine agonist. [4] This is an important physiological pathway for the medical treatment of pain.

The cannabinoid receptor is a typical member of the largest known family of receptors called a G protein-coupled receptor. A signature of this type of receptor is the distinct pattern of how the receptor molecule spans the cell membrane seven times. The location of cannabinoid receptors exists on the cell membrane, and both outside (extracellularly) and inside (intracellularly) the cell membrane. CB1 receptors, the bigger of the two, are extraordinarily abundant in the brain: 10 times more plentiful than mu opioid receptors, the receptors responsible for the effects of morphine. CB2 receptors are structurally different (the homology between the two subtypes of receptors is 44%), found only on cells of the immune system, and seems to function similarly to its CB1 counterpart. CB2 receptors are most commonly prevalent on B-cells, natural killer cells, and monocytes, but can also be found on polymorphonuclear neurtrophil cells, T8 cells, and T4 cells. In the tonsils the CB2 receptors appear to be restricted to B-lymphocyte-enriched areas.

Cannabis also contains a related class of compound: the Cannaflavins. These compounds have been suggested to contribute certain effects of cannabis, such as analgesia and anti-inflammatory properties, and are considerably more effective than aspirin. Cannaflavins usually contain a 1,4-pyrone ring fused to a variedly derivatized aromatic ring and linked to a 2nd variedly derivatized aromatic ring and include for example the non-psychoactive Cannflavin A and B.

The nature of marijuana, its lipophilic (fat soluble) properties, yields a long elimination half-life relative to other recreational drugs. The THC molecule, and related compounds, are usually detectable in drug tests for up to approximately one month after using cannabis (see drug test). This detection is possible because non-psychoactive THC metabolites are stored for long periods of time in fat cells, and THC has an extremely low water solubility. It is this slow and steady removal from the body that is linked with usually mild or nonexistent withdrawal symptoms after single or occasional use of the drug. The rate of elimination of metabolites is slightly greater for more frequent users due to tolerance, and indicates greater possibility for withdrawal symptoms after termination of chronic or habitual use.

The LD50 of THC is 1270 mg/kg (male rats), 730 mg/kg (female rats) oral in sesame oil, and 42 mg/kg (rats) from inhalation. [5]

Physiological effects

Some of the effects of marijuana use include increased heart rate, dryness of the mouth, reddening of the eyes (congestion of the conjunctival blood vessels), a reduction in intra-ocular pressure, mild impairment of motor skills and concentration, and increased hunger. Electroencephalography shows somewhat more persistent alpha waves of slightly lower frequency than usual. [2] Cannabis also produces many subjective effects, such as greater enjoyment of food's taste and aroma and an enhanced enjoyment of music and comedy. At higher doses, cannabis can cause marked distortions in time and space perception, altered body image, auditory and/or visual (more like daydreams) hallucinations, ataxia from selective impairment of polysynaptic reflexes, and depersonalization. Marijuana generally relieves tension and provides a sense of euphoria. There is a more complete list of effects at: cannabis (drug).

The areas of the brain where cannabinoid receptors are most prevalently located are consistent with the behavioral effects produced by cannabinoids. Brain regions in which cannabinoid receptors are very abundant are: the basal ganglia, associated with movement control; the cerebellum, associated with body movement coordination; the hippocampus, associated with learning, memory, and stress control; the cerebral cortex, associated with higher cognitive functions; and the nucleus accumbens, regarded as the reward center of the brain. Other regions where cannabinoid receptors are moderately concentrated are: the hypothalamus, mediating body housekeeping functions; the amygdala, associated with emotional responses and fears; the spinal cord, associated with peripheral sensations like pain; the brain stem, associated with sleep, arousal, and motor control; and the nucleus of the solitary tract, associated with visceral sensations like nausea and vomiting. [6]

Most notably, the two areas of motor control and memory are where the effects of marijuana are directly and irrefutably evident. Cannabinoids, depending on the dose, inhibit the transmission of neural signals through the basal ganglia and cerebellum. At lower doses, canabinoids seem to stimulate locomotion while greater doses inhibit it, most commonly manifested by lack of steadiness (body sway and hand steadiness) in motor tasks that require a lot of attention. Other brain regions, like the cortex, the cerebellum, and the neural pathway from cortex to striatum, are also involved in the control of movement and contain abundant cannabinoid receptors, indicating their possible involvement as well.

One of the primary effects of marijuana in humans is the disruption of short-term memory, which is consistent with the abundance of CB1 receptors on the hippocampus. The effects of THC at these receptor sites produce what is called a "temporary hippocampal lesion." [3] As a result of this lesion, several neurotransmitters like acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and glutamate, are released that trigger a major decrease in neuronal activity in the hippocampus and its inputs. In the end, this procedure leads to the blocking of cellular processes that are associated with memory formation. There is no scientific evidence to suggest that these effects are permanent, and normal neurological functionality is eventually regained, usually as the drug is metabolized.

The total duration of cannabis intoxication when smoked is about 1 to 4 hours. A study of ten healthy male volunteers who resided in a residential research facility sought to examine both acute and residual subjective, physiologic, and performance effects of smoking marijuana cigarettes. On three separate days, subjects smoked one NIDA marijuana cigarette containing either 0%, 1.8%, or 3.6% THC, documenting subjective, physiologic, and performance measures prior to smoking, five times following smoking on that day, and three times on the following morning. Subjects reported robust subjective effects following both active doses of marijuana, which returned to baseline levels within 3.5 hours. Heart rate increased and the puplilary light reflex decreased following active dose administration with return to baseline on that day. Additionally, marijuana smoking acutely produced decrements in smooth pursuit eye tracking. Although robust acute effects of marijuana were found on subjective and physiological measures, no effects were evident the day following administration, indicating that the residual effects of smoking a single marijuana cigarette are minimal. [7]

Animal research has shown that the potential for cannabinoid psychological dependence does exist, and includes mild withdrawal symptoms. Although not as severe as that for alcohol, heroin, or cocaine dependence, marijuana withdrawal is usually characterized by insomnia, restlessness, loss of appetite, irritability, anger, increased muscle activity (jerkiness), and aggression after sudden cessation of chronic use as a result of physiological tolerance. Prolonged marijuana use produces both pharmacokinetic changes (how the drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted) and pharmacodynamic changes (how the drug interacts with target cells) to the body. These changes require the user to consume higher doses of the drug to achieve a common desirable effect, and reinforce the body’s metabolic systems for synthesizing and eliminating the drug more efficiently. [3]

Preliminary research, published in the April 2006 issue of the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, indicates that cannabis addiction can be offset by a combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy and motivational incentives. Participants in the study (previously diagnosed with marijuana dependence) received either vouchers as incentives to stay drug free, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or both over a 14-week period. At the end of 3 months, 43 percent of those who received both treatments were no longer using marijuana, compared with 40 percent of the voucher group, and 30 percent of the therapy group. At the end of a 12-month follow-up, 37 percent of those who got both treatments remained abstinent, compared with 17 percent of the voucher group, and 23 percent of the therapy group. [8]

A 1998 French governmental report commissionned by Health Secretary of State Bernard Kouchner, and directed by Dr. Pierre-Bernard Roques, classed drugs according to addictiveness and neurotoxicity. It placed heroin, cocaine and alcohol in the most addictive and lethal categories; benzodiazepine, hallucinogens and tobacco in the medium category, and cannabis in the last category. The report stated that "Addiction to cannabis does not involve neurotoxicity such as it was defined in chapter 3 by neuroanatomical, neurochemical and behavioral criteria. Thus, former results suggesting anatomic changes in the brain of chronic cannabis users, measured by tomography, were not confirmed by the accurate modern neuro-imaging techniques. Moreover, morphological impairment of the hippocampus [which plays a part in memory and navigation] of rat after administration of very high doses of THC (Langfield et al., 1988) was not shown (Slikker et al., 1992)." Health Secretary Bernard Kouchner concluded that : "Scientifical facts show that, for cannabis, no neurotoxicity is demonstrated, to the contrary of alcohol and cocaine." [9]

Reproductive effects

It has been shown that administration of high doses of THC to animals lowers serum testosterone levels, impairs sperm production, motility, and viability, disrupts the ovulation cycle, and decreases output of gonadotropic hormones. However, there are also contradictory reports, and it is also possible that tolerance develops to these effects. [2] [10] According to the 1997 Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, fertility effects related to cannabis use are uncertain.

Research has demonstrated that human sperm contains receptors which are stimulated by substances like THC and other cannabis-related chemicals. Tests have shown that sperm exposed to high levels of THC began to swim in an abnormal fashion, and were less able to attach to an egg so that fertilization could take place. [11] While many men who use cannabis have fathered children, certain men at risk for infertility may be more susceptible to reproductive complications.

Marijuana use during pregnancy, in certain cases, has been linked to low birth weight but the link between cannabis and birth complications is questioned by many in the scientific community. Many studies about drug use during pregnancy are self-administered by the applicants and not always anonymous. The stigma of using illicit drugs while pregnant discourages honest reporting and can invalidate the results. Studies show that women who consume cannabis while they are pregnant may also be likely to consume alcohol, tobacco, or other illicit drugs, which makes it difficult to deduce scientific facts about just marijuana use from statistical results. Very few large, well-controlled epidemiological studies have taken place to understand the connection of marijuana use and pregnancy. One for example, by Zuckerman and colleagues, included a large sample of women with a substantial prevalence of marijuana use that was verified by urine analysis and no increased probability of birth defects was found in the sample group. Opposed to fetal alcohol syndrome, similar type facial features and related symptoms are not associated with prenatal marijuana exposure. [12] THC passes into the breast milk and may affect a breastfed infant. [13]

A study of the development of 59 Jamaican children, one-half of the sample's mothers used marijuana during pregnacy, was research from birth to age 5 years. Pregnant non-using mothers were paired with cannabis users who matched age, parity, and socioeconomic status. Testing was done at 1, 3, and 30 days of age with the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scales, and at ages 4 and 5 years with the McCarthy Scales of Children's Abilities test. Data was also collected from the child's home environment and temperament, as well as standardized tests. The results over the entire reseach period showed no significant differences in development testing outcomes between using and non-using mothers. At 30 days of age, however, the children of marijuana-using mothers had higher scores on autonomic stability and reflexes. [14] The absence of any differences between the exposed on nonexposed groups in the early neonatal period suggest that the better scores of exposed neonates at 1 month are traceable to the cultural positioning and social and economic characteristics of mothers using marijuana that select for the use of marijuana but also promote neonatal development. [15]

Effects on mental health

Behavioral effects

It is sometimes observed, and generally stereotyped, that systematic changes in a person’s lifestyle, ambitions, motivation, and personality happen when a young person starts smoking marijuana. In fact, in many situations when people are asked to describe the personality traits of a marijuana user, they will most likely portray a person of apathy or loss of effectiveness: a person with diminished capacity or willingness to carry out complex long-term plans, endure frustration, concentrate for long periods, follow routines, or even successfully master new material. [16]

The term "amotivational syndrome" is often applied to young individuals who have changed from clean, assertive, upwardly mobile achievers into the sort of person just described, with marijuana as the culprit. The syndrome, like other correlational phenomena, raises a chicken-and-egg type problem; marijuana use can just as easily be seen as the result of such a personality shift as it can be the cause of it. Regardless, studies to raise this and other questions, like the prevalence of such "syndrome" in the population, and proving a biological or psychological connection of the "syndrome" to substance use, have not happened. Instead, a political tug of war has ensued with each point of view claiming their own scientific research as evidence.

Government studies often point to statistical data accumulated by methods like the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA), the Monitoring the Future study (MTF), and the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM) program, which claim lower school averages and higher dropout rates among users than nonusers, even though these differences are very small and may be exaggerated by the stigma attached to students who use the drug. However, the major contributor to a lack of credibility in these studies, is that in many cases, like with NHSDA and MTF, these surveys are usually self-administered and may or may not be anonymous. The likeliness of over or under representing data definitely undermines the effectiveness of these instruments. [4] The MTF study is conducted anonymously, but only seeks information from a sample of people who have been arrested for drug-related offenses. Clearly, the case can easily be made that socially deviant behavior will be found more frequently in individuals of the criminal justice system compared to those in the general population, including non users. In response, independent studies of college students have shown that there was no difference in grade point average, and achievement, between marijuana users and nonusers, but the users had a little more difficulty deciding on career goals, and a smaller number were seeking advanced professional degrees. [17] Laboratory studies of the relationship between motivation and marijuana outside of the classroom, where volunteers worked on operant tasks for a wage representing a working world model, also fail to distinguish a noticeable difference between users and non users. [18]

Gateway drug hypothesis

The gateway drug hypothesis asserts that the use of cannabis ultimately leads to the use of harder drugs. For the most part, it was commonly thought that cannabis gateways to other drugs because of social factors. For example, the criminalization of cannabis in many countries associates its users with organized crime promoting the illegal drug trade.

According to neurologist Jim van Os, some scientists believe that there is also a physiological component to the gateway drug effect. He states there is "overwhelming evidence that nobody in the brain's developmental stage – under the age of 21 – should use cannabis." [19]

A July 2006 study by Ellgren et al. [20] strictly tested lab rats for the biological mechanism of the gateway drug effect. The study administered 6 "teenage" (28 and 49 days old) rats delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, and 6 were the control. One week after the first part was completed, catheters were inserted in the jugular vein of all of the adult rats and they were able to self-administer themselves heroin by pushing a lever. The study found that initially both groups behaved the same and began to self-administer heroin frequently, but then stabilized at different levels. The rats that had previously been administered THC consumed about 1.5 times more heroin than those that had not. Because many cannabinoid receptors interact with the opioid system, the study found that adolescent cannabis use overstimulates and alters the pleasure and reward structures of the brain, thus increasing the risk of addiction. Psychopharmacologist Ian Stolerman, from King's College London, finds the biological cannabis gateway drug effect "somewhat preliminary", and states "it's too early to say there's a consensus, but a small number of studies like this suggest that there is a physiological basis for this effect." Other drugs, he notes, such as cocaine and amphetamines are involved in another brain pathway called the dopaminergic system. Cells in that system also interact with THC receptors and could be modified by cannabis exposure. [21] Cannabinoid receptors are 10 times more prevalent in the brain than opioid receptors. According to Dr. Hurd, one of the study leaders, two other drugs that also stimulate opioid cells, and could therefore also feasibly cause a gateway effect, are nicotine and alcohol.

Co-occurrence of mental illness

Scientific studies have correlated a change in mental health with cannabis use for young people. Particularly, studies have shown that a risk does exist in some individuals to develop symptoms of psychosis [22] and anxiety [23]. The risk was found to be directly related to high dosage and frequency of use, early age of introduction to the drug, and was especially pronounced for those with a predisposition for mental illness. These results have been questioned as being biased by failing to account for medicinal versus recreational usage: [24] It could be a causal relationship, or it could be that people who are susceptible to mental problems tend to smoke cannabis, or it could be connected to the criminalization of cannabis. Another important question is whether the observed symptoms of mental illness are actually connected to development of a permanent mental disorder. Cannabis may trigger latent conditions, or be part of a complex coordination of causes of mental illness, referred to as the diathesis-stress model in psychology. People with developed psychological disorders often tend to self-medicate their symptoms with cannabis as well, although one study has claimed that those with a predisposition for psychosis did not show an increase in likelihood of cannabis use four years later. There has not currently been enough scientific study of the drug's effects to come to a definite conclusion.

Similarity of symptoms

There is a classification of psychosis within the DSM-IV called 'cannabis psychosis' which is very rare. In susceptible individuals, ingestion of sufficient quantities of the drug can trigger an acute psychotic event. It should be noted that the extent of a subject's experience with cannabis is a strong factor determining susceptability.

A Yale research study notes that subjects administered pure delta-9-THC induced transient symptoms which resemble those of schizophrenia "ranging from suspiciousness and delusions to impairments in memory and attention". There were no side effects in the study participants one, three, and six months after the study. [25]

Correlation studies

Cannabis use appears to be neither a sufficient nor a necessary cause for psychosis. It might be a component cause, part of a complex constellation of factors leading to psychosis, or it might be a correlation without forward causality at all. Similar correlations can be drawn between cannabis usage and glaucoma, for instance, because those who suffer from glaucoma are more likely to use cannabis due to the relief it provides.

A review of the evidence by Louise Arsenault, et al in 2004 reports that on an individual level, cannabis use confers an overall twofold increase in the relative risk of later schizophrenia. This same research also states that "There is little dispute that cannabis intoxication can lead to acute transient psychotic episodes in some individuals". The study synthesizes the results of several studies into a statistical model. [26]

However, a 2005 study found that "the onset of schizotypal symptoms generally precedes the onset of cannabis use. The findings do not support a causal link between cannabis use and schizotypal traits". [27]

A landmark study, in 1987, of 50,000 Swedish Army conscripts, found that those who admitted at age 18 to having taken cannabis on more than 50 occasions, were six times more likely to develop schizophrenia in the following 15 years. In fact, psychosis cases were restricted to patients requiring a hospital admission. These findings have not been replicated in another population based sample. [28] As the study did not control for symptoms preexisting onset of cannabis use, the study does not resolve the correlation versus causality question but has fueled a major debate within the scientific community.

Research based on the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study has found that those who begin regular use of cannabis in early adolescence (from age 15, median 25 days per year by age 18) and also fit a certain genetic profile (specifically, the Val/Val variant of the COMT gene) are five times more likely to develop psychotic illnesses than individuals with differing genotypes, or those who do not use cannabis. [29] [30] The study was noted for it having controlled for preexisting symptoms, but is open to the criticism that it cannot control for late adolescent onset of psychotic illness. Also, the study was on a cohort population, so there is no way to correlate a change in the rate of adolescent use with a change in the rate of incidence of schizophenia in the study population. These points undermine its value in resolving the correlation versus causality question.

Smoking

The process most popularly used to ingest cannabis is smoking, and for this reason most research has evaluated health effects from this method of ingestion. Other methods of ingestion may have lower or higher health risks, as the case may be. See section on harm reduction below for more information on other methods of ingestion.

Different and fewer risks than tobacco

Tobacco smoking has well-established risks such as bronchitis, coughing, overproduction of mucus, and wheezing. Similar risks for smoking cannabis related to airway inflammation have been suggested in a study of healthy cannabis users who exhibited similar early characteristics to tobacco smoking. [31]

The effects of tobacco and cannabis smoking differ, however, as they affect different parts of the respiratory tract: whereas tobacco tends to penetrate to the smaller, peripheral passageways of the lungs, cannabis tends to concentrate on the larger, central passageways. One consequence of this is that cannabis, unlike tobacco, does not appear to cause emphysema. Also, unlike tobacco, regular cannabis use does not appear to cause COPD, either. [32] Researchers have speculated on potential side effects[citation needed] from the fact that cannabis burns at a higher temperature than tobacco.

It is important to note that in some cases, a cannabis user may encounter commercial tobacco in joints (popular in Europe), added tobacco with hash in chillum (India), or cannabis rolled in tobacco leaves, which would expose the user to the additional risks of tobacco, though nothing on the same order as regular tobacco use.

Potency matters

By analogy with tobacco smoking, an NIDA-funded study sought to establish a risk to respiratory health by analysing the contents of cannabis smoke, observe inhalation volume of cannabis smokers, and infer risks such as blood carboxyhemoglobin levels from this. [33]

The methodological difficulty, however, was that all the subjects were both tobacco and cannabis smokers, smoking ultra-low-potency (0.004% and 1.24%) NIDA-provided cannabis. Typical potency is closer to 7-15%. Like a listener turning up a radio until he can hear it, a cannabis smoker will regulate the dose by smoking until the desired effect is felt, which in ultra-low-potency cannabis translates into much greater volume of inhaled smoke, and so abnormally high blood carboxyhemoglobin levels. Typical levels would therefore be much lower than the study found. These problems notwithstanding, this is a primary study cited by NIDA in this regard.

Cancer risk

Cannabis smoke contains numerous compounds known to cause cancer. Surprisingly, scientific studies have failed to show higher cancer rates in cannabis smokers. A study published in 2006 [34] on a large population sample (1,200 people with lung, neck, or head cancer, and a matching group of 1,040 without cancer) failed to positively correlate a lung cancer risk, in fact the results indicated a slight negative correlation between long and short-term cannabis use and cancer, suggesting a possible therapeutic effect. This followed an even larger 1997 study [35] examining the records of 64,855 Kaiser patients, which also found no positive correlation between cannabis use and cancer. It has been noted, separately, that THC, a dilative agent, may help cleanse the lungs by dilating the bronchia, and could actively reduce the instance of tumors. [36] Additionally, a study by Rosenblatt et al. found no association between marijuana use and the development of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. [37]

Although the carcinogenicity of tobacco is thought to be caused mainly by tar, it has been suggested that it could be the result of radioactive substances present in tobacco soils [38]. This problem does not pertain to cannabis, the vast majority of which is grown in wild, organic, or hydroponic conditions.

Attempts at harm reduction

The health consequences of cannabis use may vary depending on method of use. Proposed alternatives include:

- filtered cigarettes

- bongs (specialized pipes filtering smoke through water)

- vaporizers (devices for extracting THC without combusting the cannabis)

- eating ("space cakes")

- high potency cannabis

Like tobacco smoke, marijuana smoke contains tars which are rich in carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are a prime culprit in smoking-related cancers. However, cannabinoids themselves are not carcinogenic. An obvious way to protect smokers' health is therefore to minimize the content of smoke tars relative to cannabinoids.

The most obvious way to do this is to bypass smoking completely by simply eating the cannabis as "space cakes".

Another way is to increase the THC potency of the marijuana (see also section on potency above). Assuming smokers adjust their smoke intake to the cannabinoid dosage, the higher the concentration of cannabinoids, the lower the amount of tars they are likely to consume to achieve their desired effect.

Vaporisers, by heating the cannabis oils to be inhaled without combustion, almost avoid the risk altogether [39]. A 2000 study conducted by NORML and MAPS found that the two tested vaporizers performed up to 25% better than unfiltered marihuana cigarettes in terms of tar delivery.

Surprisingly, the same study found that water pipes (bongs) and filtered cigarettes performed 30% worse than regular, unfiltered joints. The reason is that waterpipes and filters filter out more psychoactive THC than they do tars, thereby requiring users to smoke more to reach their desired effect. The study does not, however, rule out the possibility that waterpipes could have other benefits, such as filtering out harmful gases such as carbon monoxide.

Cannabis and driving

There are several main obstacles to determining the effect of cannabis use on driving: Cannabis use is most common in a demographic that is already vulnerable for traffic accidents; dangerous drivers who tested positive for THC often test positive for alcohol as well; there are no figures or estimates available as a "base-line," for instance, how many cannabis users drive safely without incidents; and there are many ethical and legal obstacles impeding research on this topic.

A 2001 study by the United Kingdom Transit Research Laboratory (TRL) specifically focuses on the effects of Cannabis use on driving [40], and is one of the most recent and commonly quoted studies on the subject. The report summarizes current knowledge about the effects of cannabis on driving and accident risk based on a review of available literature published since 1994 and the effects of cannabis on laboratory based tasks.

The study identified young males, amongst whom cannabis consumption is frequent and increasing, and in whom alcohol consumption is also common, as an a priori risk group for traffic accidents. This is due to driving inexperience and factors associated with youth relating to risk taking, delinquency and motivation. These demographic and psychosocial variables may relate to both drug use and accident risk, thereby presenting an artificial relationship between use of drugs and accident involvement.

The effects of cannabis on laboratory-based tasks show clear impairment with respect to tracking ability, attention, and other tasks depending on the dose administered. These effects however, are not as pronounced on tasks of greater ecological validity, like real driving or simulator tasks. Both simulation and road trials generally find that driving behavior shortly after consumption of larger doses of cannabis results in: a more cautious driving style; increased variability in lane position (and headway); and longer decision times. Whereas these results indicate a 'change' from normal conditions, they do not necessarily reflect 'impairment' in terms of performance effectiveness since few studies report increased accident risk. However, the results do suggest 'impairment' in terms of performance efficiency given that some of these behaviors may limit the available resources to cope with any additional, unexpected or high demand, events. Indeed, compensatory effort can be invoked to offset impairment in the driving task. Subjects under cannabis treatment appear to perceive that they are impaired and can compensate, for example, by not overtaking, by slowing down and by focusing their attention when they know a response will be required. This compensatory effort may be one reason for the failure to implicate cannabis consumption as an accident risk factor. However, this claim is difficult to substantiate in the absence of any substantial epidemiological estimates of accident risk.

Specifically, 4-12% of accident fatalities have detected levels of cannabis. However, most studies report that the majority of fatal cases with detected levels of cannabis are compounded by alcohol. The study estimates 11ng/ml THC as the equivalent does to the legal limit of alcohol (0.08% BAC in the UK), although cannabis effects on driving are present up to an hour after smoking but do not continue for extended periods. Alcohol alone or in combination with cannabis, increases impairment, accident rate and accident responsibility. Moreover, accident risk cannot be derived in the absence of baseline data for non-fatal cases.

Similar conclusions have been reached by studies maintained by the federal governments of Australia, United Kingdom, New Zealand and the United States (see here for a list of studies). Those studies that have concluded that cannabis has a significant negative effect on driving ability generally involve the use of roadside sobriety tests as an indicator of reduced ability (for example, see this NIDA report). However, studies that employ this methodology show that a majority of subjects who tested positive for THC also tested positive for alcohol, already described as a limiting factor of validity.

References

- ^ Lyle E. Craker, Ph.D. v. U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, Docket No. 05-16, May 8 2006, 8-27 PDF

- ^ a b c d H.K. Kalant & W.H.E. Roschlau (1998). Principles of Medical Pharmacology (6th edition ed.). pp. 373–375.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e J.E. Joy, S. J. Watson, Jr., and J.A. Benson, Jr, (1999). Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing The Science Base. Washington D.C: National Academy of Sciences Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b H. Abadinsky (2004). Drugs: An Introduction (5th edition ed.). pp. 62–77, 160–166.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ "Erowid Cannabis (Marijuana) Vault".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ R.G. Pertwee (1997). "Pharmacology of Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 Receptors". Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 74 (2): 129–180.

- ^ R.V Fant, S.J. Heishman, E.B. Bunker, W.B Pickworth (Aug 1998). "Acute and residual effects of marijuana in humans". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 60 (4): 777–84.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Combination of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Motivational Incentives Enhance Treatment for Marijuana Addiction" (Press release). National Institutes of Health. April 1, 2006.

- ^ 1998 INSERM-CNRS report, directed by Pr. Bernard Roques and commissionned by Health Secretary of State Bernard Kouchner [1] [2] [3] [4]

- ^ W. Hall, N. Solowij (Nov 1998). "Adverse Effects of Cannabis". The Lancet. 352: 1611–6.

- ^ H. Schuel; et al. (Sep 2002). "Evidence that anandamide-signaling regulates human sperm functions required for fertilization". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 63 (3): 376–387.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ S.J. Astley, S.K. Clarren, R.E. Little, P.D. Sampson, J.R. Daling (Jan 1992). "Analysis of facial shape in children gestationally exposed to marijuana, alcohol, and/or cocaine". Pediatrics. 89 (1): 67–77.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. Berkow MD; et al. (1997). The Merck Manual of Medical Information (Home Edition). p. 449.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ J.S. Hayes, R. Lampart, M.C. Dreher, L. Morgan (Sept 1991). "Five-year follow-up of rural Jamaican children whose mothers used marijuana during pregnancy". West Indian Medical Journal. 40 (3): 120–3.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M.C. Dreher, K. Nugent, R. Hudgins (Feb 1994). "Prenatal Marijuana Exposure and Neonatal Outcomes in Jamaica: An Ethnographic Study". Pediatrics. 93 (3): 254–260.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ W.A. McKim (1993). "Amotivational Syndrome". Drugs and Behavior: 229–230.

- ^ N.Q. Brill, R.L. Christie (1974). "Marihuana and Psychosocial Adjustment". Archives of General Psychiatry. 31: 713–719.

- ^ H.H. Mendelson, J.C. Kuehnle, I. Greenberg; N.K. Mello (1976). "The Effects of Marihuana Use on Human Operant Behavior: Individual Data…". Pharmacology of Marihuana. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press. pp. 643–653.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gaia Vince (July 5, 2006). "Why teenagers should steer clear of cannabis". NewScientist.com.

- ^ Maria Ellgren, Sabrina M Spano & Yasmin L Hurd (July 5, 2006). "Adolescent Cannabis Exposure Alters Opiate Intake and Opioid Limbic Neuronal Populations in Adult Rats". Neuropsychopharmacology. advance online.

- ^ Michael Hopkin (July 5, 2006). "Rats taking cannabis get taste for heroin". Nature.

- ^ Cécile Henquet, Lydia Krabbendam, Janneke Spauwen, Charles Kaplan, Roselind Lieb, Hans-Ulrich Wittchen and Jim van Os (Dec 2004). "Prospective cohort study of cannabis use, predisposition for psychosis, and psychotic symptoms in young people". British Medical Journal. 330 (11).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ G C Patton, Carolyn Coffey, J B Carlin, Louisa Degenhardt, Micheal Lynskey and Wayne Hall (2005). "Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study". British Medical Journal. 325: 1195.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ T.F. Denson, M. Earleywine (June 20, 2005). "Decreased depression in marijuana users". Addictive Behaviors.

- ^ J. Weaver (14 June 2004). "Study Finds Cannabis Triggers Transient Schizophrenia-Like Symptoms". Yale News Release.

- ^ L. Arseneault; et al. (2004). "Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 184: 110–117.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ J. Schiffman; et al. (30 March 2005). "Symptoms of schizotypy precede cannabis use". Psychiatry Research. 134 (1): 37–42.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ S. Andreasson; et al. (1987). "Cannabis and Schizophrenia: A Longitudinal Study of Swedish Conscripts". The Lancet. 2: 1483–1486.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Louise Arseneault, Mary Cannon, Richie Poulton, Robin Murray, Avshalom Caspi, Terrie E Moffitt (23 November 2002). "Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study" (PDF). British Medical Journal.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Avshalom Caspi, Terrie E. Moffitt, Mary Cannon, Joseph McClay, Robin Murray, HonaLee Harrington, Alan Taylor, Louise Arseneault, Ben Williams, Antony Braithwaite, Richie Poulton, and Ian W. Craig (18 January 2005). "Moderation of the Effect of Adolescent-Onset Cannabis Use on Adult Psychosis by a Functional Polymorphism in the catechol-O-Methyltransferase Gene:Longitudinal Evidence of a Gene X Environment Interaction" (PDF). Society of Biological Psychiatry.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M.D. Roth; et al. (March 1998). "Airway Inflammation in Young Marijuana and Tobacco Smokers". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 157 (3): 928–937.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ D.P. Tashkin; et al. (Jan 1997). "Heavy habitual marijuana smoking does not cause an accelerated decline in FEV1 with age". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155 (1): 141–148.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ T.C. Wu; et al. (11 Feb 1988). "Pulmonary hazards of smoking marijuana as compared with tobacco". New England Journal of Medicine. 318 (6): 347–351.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ WebMD (23 May 2006). "Pot Smoking Not Linked to Lung Cancer". ScienceNOW, Abstract

- ^ S. Sidney (Sep 1997). "Marijuana use and cancer incidence (California, United States)". Cancer Causes and Control. 8 (5): 722–728.

- ^ J. Huff & P. Chan (Oct 2000). "Antitumor Effects of THC". Environmental Health Perspectives. 108 (10): A442-3.

- ^ K.A. Rosenblatt; et al. (1 June 2004). "Marijuana Use and Risk of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma". Cancer Research. 64: 4049–4054.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ G.F. Kilthau (Jan–Feb 1996). "Cancer risk in relation to radioactivity in tobacco". Radiologic Technology. 67 (3).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ B. Mirken (17 Sep 1999). "Vaporizers for Medical Marijuana". AIDS Treatment News. 327.

- ^ United Kingdom Department for Transport (4 Nov 2004). "Cannabis and driving: a review of the literature and commentary (No.12)".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

See also

- Demand reduction

- Drug abuse

- Drug addiction

- Drug rehabilitation

- Drug urban legends

- Hard and soft drugs

- Harm reduction

- Prohibition (drugs)

- Psychoactive drug

- Recreational drug use

- Responsible drug use

External links

- Marijuana Myths & Facts Health effects

- Cannabis Use and Psychosis from National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Australia

- Marijuana Vault at erowid.org

- The key research on cannabis use and mental illness at BBC News

- Provision of Marijuana and Other Compounds For Scientific Research recommendations of The National Institute on Drug Abuse National Advisory Council

- Scientific American Magazine (December 2004 Issue) The Brain's Own Marijuana