Innaba

Innaba

عنابة | |

|---|---|

Innaba, before 1948 | |

| Etymology: Jujube[1] | |

| Coordinates: 31°54′08″N 34°56′52″E / 31.90222°N 34.94778°E | |

| Palestine grid | 145/145 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Ramle |

| Date of depopulation | July 10, 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12,857 dunams (12.857 km2 or 4.964 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 1,420[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Kefar Shemu'el[5] |

Innaba (Template:Lang-ar) was a Palestinian village in the Ramle Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine. It was depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War on July 10, 1948 by the Yiftach and Eighth Brigades of Operation Dani. It was located 7 km east of Ramla.

History

The Romans referred to the village as "Betoannaba",[6] and ceramics from the Byzantine era have been found here.[7]

Al-Muqaddasi (c. 945/946 - 991), in his description of Ramla, noted that it had a gate called "The gate of the Innaba Mosque".[8]

Ottoman era

Innaba, like the rest of Palestine, was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517, and in the tax records of 1596 it was a village in the nahiya ("subdistrict") of Ramla, part of Gaza Sanjak, with a population of 30 households; an estimated 165 people, all Muslims. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on agricultural products, which included wheat, barley, summer crops, olive trees, sesame, vineyards, fruit trees, goats and beehives, in addition to occasional revenues; a total of 4,200 akçe. All of the revenues went to a waqf.[9][6]

In 1838, it was noted as a Muslim village, 'Anabeh, in the District of Lydda.[10][11]

In 1863, Victor Guérin found that it had 900 inhabitants,[12] while an Ottoman village list from about 1870 noted it as having a population of 250, in 79 houses, though the population count included men, only.[13][14]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described it as "A village of moderate size, on high ground, surrounded with olives, with a well to the south. The houses are of mud. It is mentioned by Jerome [.. ] as 4 Roman miles east of Lydda, and as called Betho Annaba. The distance fits almost exactly."[15]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Ennabeh had a population of 863; 862 Muslims,[16] and one Orthodox Christian.[17] In the 1931 census Innaba was counted with Al-Kunayyisa, together they had 1135 Muslim inhabitants, in 288 houses.[18] An elementary school for boys was founded in 1920 and in 1945, it had an enrollment of 168 students. Innaba also had a mosque, which was dedicated to al-Shaykh 'Abd Allah and had a shrine for him.[6]

In the 1945 statistics it had population of 1,420 Muslims,[2] while the total land area was 12,857 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[3] Of this, a total of 111 dunams were uses for citrus and bananas, 511 were plantations and irrigable land, 10,626 were used for cereals,[19] while 54 dunams were classified as built-up public areas.[20]

1948, aftermath

The village was depopulated on July 10, 1948, after a military assault by the Israeli army.[4][21] On the same day, Operation Danny head quarter ordered the Yiftach Brigade to blow up most of Innaba and Al-Tira, leaving only houses enough for a small garrison.[22]

-

Innaba 1942 1:20,000

-

Innaba. 1945. Survey of Palestine. Scale 1:250,000

-

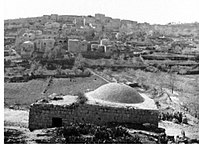

Innaba "after being shelled and abandoned"

-

Operation Dani, Yiftach Brigade in Innaba. 1948

-

Yiftach Brigade in Innaba during Operation Danny

-

Palestinian villages depopulated in the area around Lydda and Ramla (coloured in green)

The Israeli settlement of Kefar Shemu'el was established on Innaba land in 1950.[5]

Innaba was described in 1992: "The site, which overlooks the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv highway a few km from al-Latrun and its abbey, is fenced off and is difficult to enter. It is covered with heaps of rubble and overgrown with vegetation, including cactuses and stunted olive and Christ's-thorn trees from the pre-1948 period. In addition to the rubble of houses, the debris from the school and the local headquarters of the Arab Palestine Party are visible. In the cemetery, the tombs of Hasan Badwan and Ayish Badwan are prominent because of their stone super structures. A Christ's-thorn tree rises amidst the rubble of the former house of Muhammad Tummalay, and a denuded mulberry tree stands amid the rubble of Muhammad 'Abd Allah's house. The surrounding land is cultivated but remnants of the old agriculture remain, such as the groves of 'Ali al-Kasji, with their olive and pomegranate trees and cactus clusters, and the olive trees on the land of Abu Rummana. A deserted well with a heap of stones around its mouth lies in the section of the village formerly referred to as al-'Attan."[5]

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 284

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 29

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 66

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. xix, village #244. Also gives cause of depopulation

- ^ a b c Khalidi, 1992, p. 384

- ^ a b c Khalidi, 1992, p. 383

- ^ Dauphin, 1998, p. 837

- ^ Muqaddasi,1886, p. 33

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 155

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 121

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, p. 30

- ^ Guérin, 1868, pp. 314-317

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 154

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 138, also noted 79 houses

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, SWP III, p. 14

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Ramleh, p. 21

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table xiv, p. 46

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 20

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 115

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 165

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 435, note #119, p. 456

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 355, note #86, p. 400

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Mukaddasi (1886). Description of Syria, including Palestine. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

- Welcome To 'Innaba

- Innaba, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- 'Innaba from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center