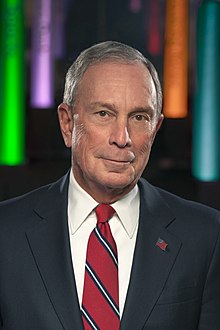

Michael Bloomberg

Michael Bloomberg | |

|---|---|

| |

| 108th Mayor of New York City | |

| In office January 1, 2002 – December 31, 2013 | |

| Deputy | Patricia Harris |

| Preceded by | Rudy Giuliani |

| Succeeded by | Bill de Blasio |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Michael Rubens Bloomberg February 14, 1942 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (before 2001, 2018–present) |

| Other political affiliations | Independent (2007–2018) Republican (2001–2007) |

| Spouse |

Susan Brown-Meyer

(m. 1975; div. 1993) |

| Domestic partner | Diana Taylor (2000–present) |

| Children | 2, including Georgina |

| Education | Johns Hopkins University (BS) Harvard University (MBA) |

| Net worth | US$64 billion (February 2020)[1] |

| Signature | |

| Website | Official website |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

Michael Rubens Bloomberg[2] (born February 14, 1942) is an American politician, businessman, and author. He is the CEO and majority owner of Bloomberg L.P., which he co-founded. Bloomberg was the mayor of New York City from 2002 to 2013. He is currently a candidate in the Democratic Party primaries for the 2020 United States presidential election.

Bloomberg grew up in Medford, Massachusetts and attended Johns Hopkins University and Harvard Business School. He began his career at the securities brokerage Salomon Brothers, before forming his own company in 1981, Bloomberg L.P., a financial services, software, and mass media company that is known for its Bloomberg Terminal, a computer software system providing financial data widely used in the financial industry. He spent the next twenty years as its chairman and CEO. As of February 2020, this made him the ninth-richest person in the United States and the twelfth-richest person in the world; his net worth was estimated at $61.8 billion.[1] Since signing The Giving Pledge whereby billionaires pledge to give away at least half of their wealth, Bloomberg has given away $8.2 billion.[3]

Bloomberg served as the 108th mayor of New York City, holding office for three consecutive terms beginning his first in 2002. A lifelong Democrat before seeking elective office, Bloomberg switched his party registration in 2001 to run for mayor as a Republican. He defeated opponent Mark J. Green in a close election held just weeks after the September 11 terrorist attacks. He won a second term in 2005 and left the Republican Party two years later. Bloomberg campaigned to change the city's term limits law and was elected to his third term in 2009 as an independent on the Republican ballot line. His final term as mayor ended on December 31, 2013. Bloomberg also served as chair of the board of trustees at his alma mater, Johns Hopkins University, from 1996 to 2002. After a brief stint as a full-time philanthropist, Bloomberg re-assumed the position of CEO at Bloomberg L.P. by the end of 2014.

Bloomberg switched from Independent to Democratic affiliation in October 2018 and officially launched his campaign for the Democratic Party's nomination in the 2020 presidential election on November 24, 2019, following weeks of speculation that he would join the race as a late entry.[4]

Early life and education

Bloomberg was born at St. Elizabeth's Hospital, in Brighton, a neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, on February 14, 1942, to William Henry Bloomberg (1906–1963), a bookkeeper for a dairy company,[5] and Charlotte (Rubens) Bloomberg (1909–2011).[6][7] The Bloomberg Center at the Harvard Business School was named in William Henry's honor.[8] His family is Jewish. He is a member of the Emanu-El Temple in Manhattan.[9] Bloomberg's paternal grandfather, Alexander "Elick" Bloomberg, was an immigrant from Russia.[2] Bloomberg's maternal grandfather, Max Rubens, was an immigrant from what is present-day Belarus.[10][11]

The family lived in Allston until Bloomberg was two years old, when they moved to Brookline, Massachusetts, for the next two years, finally settling in the Boston suburb of Medford, Massachusetts, where he lived until after he graduated from college.[12]

Bloomberg is an Eagle Scout.[13][14] Bloomberg graduated from Medford High School in 1960.[15]

Bloomberg attended Johns Hopkins University, where he joined the fraternity Phi Kappa Psi. In 1962, as a sophomore, he constructed the school mascot's (the blue jay's) costume.[16] He graduated in 1964 with a Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering. In 1966, he graduated from Harvard Business School with a Master of Business Administration.[17][18]

Business career

In 1973, Bloomberg became a general partner at Salomon Brothers, a large Wall Street investment bank, where he headed equity trading and, later, systems development. In 1981, Salomon Brothers was bought[19] by Phibro Corporation, and Bloomberg was laid off from the investment bank.[20] He was given no severance package, but owned $10 million worth of equity as a partner at the firm.[21]

Using this money, Bloomberg, having designed in-house computerized financial systems for Salomon, went on to set up a company named Innovative Market Systems (IMS). His business plan was based on the realization that Wall Street (and the financial community generally) was willing to pay for high-quality business information, delivered as quickly as possible and in as many usable forms possible, via technology (e.g., graphs of highly specific trends).[22]

Bloomberg, along with Thomas Secunda, Duncan MacMillan, and Charles Zegar, developed and built a computerized system to provide real-time market data, financial calculations and other financial analytics to Wall Street firms. The machines were first called "Market Master Terminals" and later became known as "Bloomberg Terminals." In 1983, Merrill Lynch became the company's first customer, investing $30 million in IMS to help finance the development of "the Bloomberg" terminal computer system. As of 1983, IMS was selling machines exclusively to Merrill Lynch's clients; in 1984, Merrill Lynch released IMS from this exclusive deal.[23]

The company was renamed Bloomberg L.P. In 1986 5,000 terminals had been installed in subscribers' offices.[24] By 1990, it had installed 8,000 terminals.[25] Over the years, ancillary products including Bloomberg News, Bloomberg Radio, Bloomberg Message, and Bloomberg Tradebook were launched.[26]

During this time, colleagues published a pamphlet entitled Portable Bloomberg: The Wit and Wisdom of Michael Bloomberg. The work included off-color sayings that were attributed to him. Among the contents of the 1990 publication are a suggestion that if women wanted to be known for their intelligence, they would spend less time at Bloomingdale's and more at the library.[27][28] He reportedly said if his Bloomberg terminals could provide oral sex, it would put female employees out of work. Bloomberg has since explained the comments as "borscht belt jokes".[28]

As of October 2015, the company had more than 325,000 terminal subscribers worldwide.[29] Subscriptions cost $24,000 per year, discounted to $20,000 for two or more.[30] As of 2019, Bloomberg employs 20,000 people in dozens of locations.[30] The company earned approximately $10 billion in 2018, loosely $3 billion more than Thomson Reuters, now Refinitiv, its nearest competitor.[30]

The culture of the company was compared to a fraternity, and employees bragged in the company's office about their sexual exploits.[28] The company was sued four times by female employees for sexual harassment, including one incident in which a victim said she was raped. In a deposition concerning the alleged rape, Bloomberg said that he would believe a rape charge only if it were supported by “an unimpeachable third-party” witness.[31][32]

When he left the position of CEO to pursue a political career as the mayor of New York City, Bloomberg was replaced as CEO by Lex Fenwick.[33] During Bloomberg's three mayoral terms, the company was led by president Daniel L. Doctoroff, a former deputy mayor under Bloomberg.[34] After completing his final term as the mayor of New York City, Bloomberg spent his first eight months out of office as a full-time philanthropist. In fall 2014, he announced that he would return to Bloomberg L.P. as CEO at the end of 2014,[35] succeeding Doctoroff, who had led the company since retiring from the Bloomberg administration in February 2008.[35][36][37] Bloomberg still owns the business but resigned as CEO of Bloomberg L.P. to run for president in 2019.[30]

Bloomberg is a member of Kappa Beta Phi.[38] He wrote an autobiography, with help from Bloomberg News Editor-in-Chief Matthew Winkler, called Bloomberg by Bloomberg.[39]

Wealth

In March 2009, Forbes reported Bloomberg's wealth at $16 billion, a gain of $4.5 billion over the previous year, the world's biggest increase in wealth in 2009.[40] At that time, there were only four fortunes in the U.S. that were larger (although the Walmart family fortune is split among four people). He had moved from 142nd to 17th in the Forbes list of the world's billionaires in only two years.[41][42] Subsequently, Forbes reported his wealth at $22 billion, then $31 billion, then $43.3 billion, and ranked him 11th, then 10th, then 6th richest in the U.S.[43][44][45] As of November 2019, Bloomberg was the 12th richest person in the world, with a net worth estimated at $61.8 billion.[1]

Political career

Mayor of New York City

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2019) |

Bloomberg assumed office as the 108th Mayor of New York City on January 1, 2002. He won re-election in 2005 and again in 2009. As mayor, Bloomberg initially struggled with approval ratings as low as 24 percent;[46] however, he subsequently developed and maintained high approval ratings.[47] His re-election meant the Republicans had won the previous four mayoral elections (although Bloomberg's decision to leave the Republican Party and be declared an independent on June 19, 2007, resulted in the Republican Party's losing the mayor's seat prior to the expiration of his second term). Bloomberg joined Rudy Giuliani and Fiorello La Guardia as re-elected Republican mayors in the mostly Democratic city.

Bloomberg stated that he wanted public education reform to be the legacy of his first term and addressing poverty to be the legacy of his second.[48] According to the National Assessment of Educational Performance, fourth-grade reading scores from 2002 to 2009 rose nationally by 11 points, but in May 2010, The New York Times reported that eighth-graders had shown no significant improvement in math or reading.

Bloomberg chose to apply a statistical, results-based approach to city management, appointing city commissioners based on their expertise and granting them wide autonomy in their decision-making. Breaking with 190 years of tradition, he implemented what New York Times political reporter Adam Nagourney called a "bullpen" open office plan, similar to a Wall Street trading floor, in which dozens of aides and managerial staff are seated together in a large chamber. The design is intended to promote accountability and accessibility.[49]

In efforts to create "cutbacks" in the New York City Spending Bracket, Bloomberg declined to receive a city salary. He accepted a remuneration of $1 annually for his services.[50]

The reduction in crime that began in Mayor Rudy Giuliani's administration continued during Bloomberg's tenure.[51]

As mayor, Bloomberg greatly expanded the city's stop and frisk program, with a sixfold increase in documented stops.[52] New York City's policy was challenged in US Federal Court and portions of the policy were found to potentially violate civilians' 4th amendment rights.[53] Bloomberg's adminstration appealed the ruling, however his successor, Mayor Bill de Blasio, dropped the appeal and allowed the ruling to take effect.[54]

During his mayoralty, Bloomberg approved and oversaw a controversial suspicionless domestic surveillance program that targeted Muslim communities on the basis of their religion, ethnicity, and language.[55][56][57][58] The NYPD profiled and surveilled schools, bookstores, cafes, restaurants, nightclubs, and every single mosque within 100 miles (160 km) of New York City using undercover informants and officers.[59] The program was exposed in 2011 by the Associated Press in a Pulitzer Prize-winning series[56] and subsequently shuttered in 2014.[60] The program did not produce a single lead on any terrorist plots.[55]

Mayoral elections

2001 election

In 2001, the incumbent mayor of New York City, Rudy Giuliani, was ineligible for re-election, as the city limited the mayoralty to two consecutive terms. Several well-known New York City politicians aspired to succeed him. Bloomberg, a lifelong member of the Democratic Party, decided to run for mayor as a member of the Republican Party ticket.[61] Voting in the primary began on the morning of September 11, 2001. The primary was postponed later that day, due to the September 11 attacks. In the rescheduled primary, Bloomberg defeated Herman Badillo, a former Democratic congressman, to become the Republican nominee. Meanwhile, the Democratic primary did not produce a first-round winner. After a runoff, the Democratic nomination went to New York City Public Advocate Mark J. Green.

In the general election, Bloomberg received Giuliani's endorsement. He also had a huge spending advantage. Although New York City's campaign finance law restricts the amount of contributions that a candidate can accept, Bloomberg chose not to use public campaign funds and therefore his campaign was not subject to these restrictions. He spent $73 million of his own money on his campaign, outspending Green five to one.[62] One of the major themes of his campaign was that, with the city's economy suffering from the effects of the World Trade Center attacks, it needed a mayor with business experience.

In addition to serving as the Republican nominee, Bloomberg had the ballot line of the controversial Independence Party, in which "Social Therapy" leaders Fred Newman and Lenora Fulani exert strong influence. Some[who?] say that endorsement was important, as Bloomberg's votes on that line exceeded his margin of victory over Green. (Under New York's fusion rules, a candidate can run on more than one party's line and combine all the votes received on all lines. Green, the Democrat, had the ballot line of the Working Families Party). Bloomberg also created an independent line called Students First whose votes were combined with those on the Independence line. Another factor was the vote in Staten Island, which has traditionally been far friendlier to Republicans than the rest of the city. Bloomberg handily beat Green in that borough, taking 75 percent of the vote. Overall, Bloomberg won 50 percent to 48 percent.[citation needed]

Bloomberg's election marked the first time in New York City history that two different Republicans had been elected mayor consecutively. New York City has not been won by a Republican in a presidential election year since Calvin Coolidge won in 1924. Bloomberg is considered a social liberal, who is pro-choice, in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage and an advocate for stricter gun control laws.

Although 68 percent of New York City's registered voters are Democrats, Bloomberg decided the city should host the 2004 Republican National Convention. The convention drew thousands of protesters, many of them local residents angry over the Iraq war and other issues. The New York Police Department arrested approximately 1,800 protesters, but according to The New York Times, more than 90 percent of the cases were later dismissed or dropped for lack of evidence.[63]

2005 election

Bloomberg was re-elected mayor in November 2005 by a margin of 20 percent, the widest margin ever for a Republican mayor of New York City.[64] He spent almost $78 million on his campaign, exceeding the record of $74 million he spent on the previous election. In late 2004 or early 2005, Bloomberg gave the Independence Party of New York $250,000 to fund a phone bank seeking to recruit volunteers for his re-election campaign.[65]

Former Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer won the Democratic nomination to oppose Bloomberg in the general election. Thomas Ognibene sought to run against Bloomberg in the Republican Party's primary election.[66] The Bloomberg campaign successfully challenged enough of the signatures Ognibene had submitted to the Board of Elections to prevent Ognibene from appearing on ballots for the Republican primary.[66] Instead, Ognibene ran on only the Conservative Party ticket.[67] Ognibene accused Bloomberg of betraying Republican Party ideals, a feeling echoed by others.[68][69][70][71]

Bloomberg opposed the confirmation of John Roberts as Chief Justice of the United States.[72] Though a Republican at the time, Bloomberg is a staunch supporter of abortion rights and did not believe that Roberts was committed to maintaining Roe v. Wade.[72] In addition to Republican support, Bloomberg obtained the endorsements of several prominent Democrats: former Democratic Mayor Ed Koch; former Democratic governor Hugh Carey; former Democratic City Council Speaker Peter Vallone, and his son, Councilman Peter Vallone Jr.; former Democratic Congressman Floyd Flake (who had previously endorsed Bloomberg in 2001), and Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz.[73]

2009 election

On October 2, 2008, Bloomberg announced he would seek to extend the city's term limits law and run for a third mayoral term in 2009, arguing a leader of his field was needed following the financial crisis of 2007–08. "Handling this financial crisis while strengthening essential services ... is a challenge I want to take on," Bloomberg said at a news conference. "So should the City Council vote to amend term limits, I plan to ask New Yorkers to look at my record of independent leadership and then decide if I have earned another term."[74]

Ronald Lauder, who campaigned for New York City's term limits in 1993 and spent over 4 million dollars of his own money to limit the maximum years a mayor could serve to eight years,[75] sided with Bloomberg in running for a third term and agreed to stay out of future legality issues.[76] In exchange, he was promised a seat on an influential city board by Bloomberg.[77]

Some people and organizations objected and NYPIRG filed a complaint with the City Conflict of Interest Board.[78] On October 23, 2008, the City Council voted 29–22 in favor of extending the term limit to three consecutive four-year terms, thus allowing Bloomberg to run for office again.[79] After two days of public hearings, Bloomberg signed the bill into law on November 3.[80]

Bloomberg's bid for a third term generated some controversy. Civil libertarians such as former New York Civil Liberties Union Director Norman Siegel and New York Civil Rights Coalition Executive Director Michael Meyers joined with local politicians such as New York State Senator Eric Adams to protest the term-limits extension.[81]

Bloomberg's opponent was Democratic and Working Families Party nominee Bill Thompson, who had been New York City Comptroller for the past eight years and before that, president of the New York City Board of Education.[82] Bloomberg defeated Thompson by a vote of 51% to 46%.[83]

After the release of Independence Party campaign filings in January 2010, it was reported that Bloomberg had made two $600,000 contributions from his personal account to the Independence Party on October 30 and November 2, 2009.[84] The Independence Party then paid $750,000 of that money to Republican Party political operative John Haggerty Jr.[85]

This prompted an investigation beginning in February 2010 by the office of New York County District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. into possible improprieties.[86] The Independence Party later questioned how Haggerty spent the money, which was to go to poll-watchers.[87] Former New York State Senator Martin Connor contended that because the Bloomberg donations were made to an Independence Party housekeeping account rather than to an account meant for current campaigns, this was a violation of campaign finance laws.[88] Haggerty also spent money from a separate $200,000 donation from Bloomberg on office space.[89]

2013 election endorsements

On September 13, 2013, Bloomberg announced that he would not endorse any of the candidates to succeed him.[90][91] On his radio show, he stated, "I don't want to do anything that complicates it for the next mayor. And that's one of the reasons I've decided I'm just not going to make an endorsement in the race." He added, "I want to make sure that person is ready to succeed, to take what we've done and build on that."[92]

Prior to the announcement in an interview in New York magazine, Bloomberg praised The New York Times for its endorsement of Christine Quinn and Joe Lhota as their favorite, respective, candidates in the Democratic and Republican primaries.[93][94] Quinn came in third in the Democratic primary and Lhota won the Republican primary.

Earlier in the month, Bloomberg was chastised in the press for his remarks regarding Democratic mayoral candidate Bill de Blasio's campaign methods.[95] Bloomberg said initially in a New York magazine interview that he considered de Blasio's campaign "racist," and when asked about his comment, Bloomberg explained what he meant by his remark.[96]

Well, no, no, I mean he's making an appeal using his family to gain support. I think it's pretty obvious to anyone watching what he's been doing. I do not think he himself is racist. It's comparable to me pointing out I'm Jewish in attracting the Jewish vote. You tailor messages to your audiences and address issues you think your audience cares about.[96]

On January 1, 2014, de Blasio became New York City's new mayor, succeeding Bloomberg.[97]

Campaign speculation beyond New York City before 2019

Bloomberg was frequently mentioned as a possible centrist candidate for the presidential elections in 2008 and 2012, as well as for governor of New York in 2010. He declined to seek either office, opting to continue serving as the mayor of New York City.

There was widespread speculation that he would run as a third-party candidate in the 2016 presidential election, though he chose not to, later endorsing Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton for president. In October 2018, Bloomberg changed his political party affiliation back to the Democrats.[98]

2008 presidential campaign speculation

On February 27, 2008, Bloomberg announced that he would not run for president in 2008, and that he would endorse a candidate who took an independent and non-partisan approach.[99] He had also stated unequivocally, live on Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve, on December 31, 2007, that he was not going to run for president in 2008.[100] Despite prior public statements by Bloomberg denying plans for a presidential run,[101] many pundits believed Bloomberg would announce a campaign at a later date. On January 7, 2008, he met at the University of Oklahoma with a bipartisan group, including (now former) Nebraska Senator Chuck Hagel and former Georgia Senator Sam Nunn, both of whom had been frequently mentioned as possible running mates, to pressure the major-party candidates to promote national unity and reduce partisan gridlock. Speculation that Bloomberg would choose this forum to announce his candidacy proved to be unfounded.[102][103]

In summer 2006, he met with Al From of the Democratic Leadership Council, a centrist group, to talk about the logistics of a possible run.[104] After a conversation with Bloomberg, Republican Senator Chuck Hagel of Nebraska suggested that he and Bloomberg could run on a shared independent ticket for the presidency.[105]

On This Week on June 10, 2007, anchor George Stephanopoulos included panelist Jay Carney, who mentioned a conversation between Bloomberg and top staffers where he heard Bloomberg ask approximately how much a presidential campaign would cost. Carney said that one staffer replied, "Around $500 million." According to a Washington Post article, a $500-million budget would allow Bloomberg to circumvent many of the common obstacles faced by third-party presidential candidates.[106] On June 19, 2007, Bloomberg left the Republican Party, filing as an independent after a speech criticizing the current political climate in Washington.[107][108]

On August 9, 2007, in an interview with former CBS News anchor Dan Rather that aired on August 21, Bloomberg categorically stated that he was not running for president, that he would not be running, and that there were no circumstances in which he would, saying, "If somebody asks me where I stand, I tell them. And that's not a way to get elected, generally. Nobody's going to elect me president of the United States. What I'd like to do is to be able to influence the dialogue. I'm a citizen."[109]

Despite continued denials, a possible Bloomberg candidacy continued to be the subject of media attention, including a November Newsweek cover story.[110] In January 2008, CNN reported that a source close to Bloomberg said that the mayor had launched a research effort to assess his chances of winning a potential presidential bid.[111] On January 16, 2008, it was reported that Bloomberg's business interests were placed in "a sort of blind trust" because of his possible run for the presidency. His interests were put under the management of Quadrangle Group, co-founded by reported Bloomberg friend Steven Rattner, though Bloomberg would continue to control particular investment decisions.[112]

In January 2008, the Associated Press reported that Bloomberg met with Clay Mulford, a ballot-access expert and campaign manager for Ross Perot's third-party presidential campaigns. Bloomberg denied that the meeting concerned a possible presidential campaign, and said the following month, "I am not – and will not be – a candidate for president."[99]

At the same time, there was also some speculation that Bloomberg could be a candidate for the vice presidency in 2008. In a blog posting of June 21, 2007, Ben Smith of The Politico asked the question of whether a vice-presidential candidate can self-finance an entire presidential ticket.[113]

Bloomberg did not publicly endorse a candidate for the 2008 U.S. presidential election, but an aide said he voted for Barack Obama.[114]

Rumored gubernatorial campaign

In November 2007, the New York Post detailed efforts by New York State Republicans to recruit Bloomberg to oppose Governor Eliot Spitzer in the 2010 election. Early polls indicated Bloomberg would defeat Spitzer in a landslide. (The potential 2010 match-up became moot when Spitzer resigned on March 17, 2008.)[115] A March 2008 poll of New York voters showed that, in a hypothetical 2010 gubernatorial matchup, Bloomberg would defeat Governor David Paterson (who became governor after Spitzer's resignation) and former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani for the 2010 gubernatorial election.[116] Bloomberg did not run for governor.[117]

2012 presidential campaign speculation and role

In March 2010, Bloomberg's top political strategist Kevin Sheekey resigned from his mayoral advisory position and returned to Bloomberg LP, Bloomberg's company. It was speculated that the move would allow Sheekey to begin preliminary efforts for a Bloomberg presidential campaign in the 2012 election. An individual close to Bloomberg said, "the idea of continuing onward is not far from his [Bloomberg's] mind."[118]

In October 2010, the Committee to Draft Michael Bloomberg – which had attempted to recruit Bloomberg to run for the presidency in 2008 – announced it was relaunching its effort to persuade Bloomberg to wage a presidential campaign, in 2012.[119][120] The committee members insisted that they would persist in the effort in spite of Bloomberg's repeated denials of interest in seeking the presidency.[120][121]

In a December 2010 appearance on Meet the Press, Bloomberg ruled out a run for the presidency in 2012.[122] In July 2011, in the midst of Democrats' and Republicans' inability to agree on a budget plan and thus an increase in the federal debt limit, the Washington Post published a blog post about groups organizing third party approaches. It focused on Bloomberg as the best hope for a serious third-party presidential candidacy in 2012.[123]

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in November 2012, Bloomberg penned an op-ed officially endorsing Barack Obama for president, citing Obama's policies on climate change.[124][125]

2016 presidential campaign speculation and role

On January 23, 2016, it was reported that Bloomberg was again considering a presidential run, as an independent candidate in the 2016 election.[126][127] This was the first time he had officially confirmed he was considering a run.[128] Bloomberg supporters believed that Bloomberg could run as a centrist and capture many voters who were dissatisfied with the likely Democratic and Republican nominees.[129] However, on March 7, Bloomberg announced he would not be running for president.[130][131]

In July 2016, Bloomberg delivered a speech at the 2016 Democratic National Convention in which he called Hillary Clinton "the right choice".[132][133][134] In the speech, Bloomberg warned of the dangers a Donald Trump presidency would pose. He said Trump "wants you to believe that we can solve our biggest problems by deporting Mexicans and shutting out Muslims. He wants you to believe that erecting trade barriers will bring back good jobs. He's wrong on both counts." Bloomberg also said Trump's economic plans "would make it harder for small businesses to compete" and would "erode our influence in the world". Trump responded to the speech by condemning Bloomberg in a series of tweets.[132][135]

2018 elections and re-registration as Democrat

In June 2018, Bloomberg made plans to give $80 million to support Democratic congressional candidates in the 2018 election, with the goal of flipping control of the Republican-controlled House to Democrats. In a statement, Bloomberg said that Republican House leadership were "absolutely feckless" and had failed to govern responsibly. Bloomberg advisor Howard Wolfson was chosen to lead the effort, which was to target mainly suburban districts.[136] By early October, Bloomberg had committed more than $100 million to returning the House and Senate to Democratic power, fueling speculation about a presidential run in 2020.[137] On October 10, 2018, Bloomberg announced that he had changed his political party affiliation to Democrat, which he had previously been registered as prior to 2001.[138]

2020 presidential election campaign

On March 5, 2019, Bloomberg had announced that he would not run for president in 2020; instead he encouraged the Democratic Party to "nominate a Democrat who will be in the strongest position to defeat Donald Trump".[139] However, due to his dissatisfaction with the Democratic field, Bloomberg reconsidered. He officially launched his campaign for the 2020 Democratic nomination on November 24, 2019.[140]

Bloomberg is financing his campaign personally and has said he won't accept donations.[141] He has spent an estimated $318 million in ads so far.[142] As of February 17, 2020, Bloomberg was polling at 17.3% nationally according to Wikipedia's average of poll aggregators, tied with Joseph Biden (17.3%) and behind Bernie Sanders (24.4%).

Political positions

Bloomberg was a lifelong Democrat until 2001, when he switched to the Republican Party before running for Mayor. He switched to an independent in 2007, and registered again as a Democrat in October 2018.[143][144] In 2004, he endorsed the re-election of George W. Bush and spoke at the 2004 Republican National Convention. He endorsed Barack Obama's re-election in 2012, endorsed Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, and spoke at the 2016 Democratic National Convention.[145]

Bloomberg supports strict gun-control measures, abortion rights, same-sex marriage, and a pathway to citizenship for illegal immigrants.[146] He advocates for a public health insurance option that he has called "Medicare for all for people that are uncovered" rather than a universal single-payer healthcare system.[146] He is concerned about climate change and has touted his mayoral efforts to reduce greenhouse gases.[147] Bloomberg supported the Iraq War and opposed creating a timeline for withdrawing troops, but later called the war "a mistake."[148][149] Bloomberg has sometimes embraced the use of surveillance in efforts to deter crime and terrorism.[150][151]

As Mayor of New York, Bloomberg supported government initiatives in public health and welfare.[146][152] During and after[153] his tenure, he was a staunch supporter of stop-and-frisk, a policy which allowed the New York Police Department to stop and pat down civilians, and which disproportionately targeted racial minorities. In November 2019, Bloomberg apologized for supporting it.[154][155][153] He advocates reversing many of the Trump tax cuts. His own tax plan includes implementing a 5% surtax on incomes above $5 million a year and would raise federal revenue by $5 trillion over a decade. He opposes a wealth tax, saying that it would likely be found unconstitutional.[156][157] He has also proposed more stringent financial regulations that include tougher oversight for big banks, a financial transactions tax, and stronger consumer protections.[158]

Bloomberg has stated that running as a Democrat — not an independent — is the only path he sees to defeating Donald Trump, saying “In 2020, the great likelihood is that an independent would just split the anti-Trump vote and end up re-electing the President. That’s a risk I refused to run in 2016 and we can’t afford to run it now.”[143]

Philanthropy

Environmental advocacy

Bloomberg is a dedicated environmentalist and has advocated policy to fight climate change at least since he became the mayor of New York City. At the national level, Bloomberg has consistently pushed for transitioning the United States' energy mix from fossil fuels to clean energy. In July 2011, Bloomberg donated $50 million through Bloomberg Philanthropies to Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign, allowing the campaign to expand its efforts to shut down coal-fired power plants from 15 states to 45 states.[159][160] On April 8, 2015, to build on the success of the Beyond Coal campaign, Bloomberg announced an additional Bloomberg Philanthropies investment of $30 million in the Beyond Coal initiative, matched with another $30 million by other donors, to help secure the retirement of half of America's fleet of coal plants by 2017.[161]

Bloomberg's personal life was criticized by InsideSources for contradicting his environmentalist image. Bloomberg owns a private jet, a helicopter and several fuel-inefficient vehicles, including an SUV and a sports car. Bloomberg owns about ten properties, including at least three mansions. He flies to his waterfront mansion in Bermuda several times per month.[162][163]

Bloomberg, through Bloomberg Philanthropies, awarded a $6 million grant to the Environmental Defense Fund in support of strict regulations on fracking, in the 14 states with the heaviest natural gas production.[164]

In October 2013, Bloomberg and Bloomberg Philanthropies launched the Risky Business initiative with former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and hedge-fund billionaire Tom Steyer. The joint effort worked to convince the business community of the need for more sustainable energy and development policies, by quantifying and publicizing the economic risks the United States faces from the impact of climate change.[165] In January 2015, Bloomberg led Bloomberg Philanthropies in a $48-million partnership with the Heising-Simons family to launch the Clean Energy Initiative. The initiative supports state-based solutions aimed at ensuring America has a clean, reliable, and affordable energy system.[166]

Since 2010, Bloomberg has taken an increasingly global role on environmental issues. From 2010 to 2013, he served as the chairman of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, a network of the world's biggest cities working together to reduce carbon emissions.[167] During his tenure, Bloomberg worked with President Bill Clinton to merge C40 with the Clinton Climate Initiative, with the goal of amplifying their efforts in the global fight against climate change worldwide.[168] He serves as the president of the board of C40 Cities.[169] In January 2014, Bloomberg began a five-year commitment totaling $53 million through Bloomberg Philanthropies to the Vibrant Oceans Initiative. The initiative partners Bloomberg Philanthropies with Oceana, Rare, and Encourage Capital to help reform fisheries and increase sustainable populations worldwide.[170] In 2018, Bloomberg joined Ray Dalio in announcing a commitment of $185 million towards protecting the oceans.[171]

On January 31, 2014, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon appointed Bloomberg as his first Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change to help the United Nations work with cities to prevent climate change.[172] In September 2014, Bloomberg convened with Ban and global leaders at the UN Climate Summit to announce definite action to fight climate change in 2015.[173] Noting in March 2018 that "climate change is running faster than we are," Ban's successor António Guterres appointed Bloomberg as UN envoy for climate action.[174][175] He resigned on November 11, 2019, in the run-up to his presidential campaign.[176]

In late 2014, Bloomberg, Ban Ki-moon, and global city networks ICLEI-Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI), C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (C40) and United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), with support from UN-Habitat, launched the Compact of Mayors, a global coalition of mayors and city officials pledging to reduce local greenhouse gas emissions, enhance resilience to climate change, and track their progress transparently.[177] To date, over 250 cities representing more than 300 million people worldwide and 4.1% of the total global population, have committed to the Compact of Mayors,[178] which was merged with the Covenant of Mayors in June 2016.[179][180]

On June 30, 2015, Bloomberg and mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo jointly announced the creation of the Climate Summit for Local Leaders, which convened on December 4, 2015.[181] The Climate Summit assembled hundreds of city leaders from around the world at Paris City Hall,[182][183] marking the largest recorded gathering of local leaders on the subject of fighting climate change.[184] The Summit concluded with the presentation of the Paris Declaration, a pledge by leaders from assembled global cities to cut carbon emissions by 3.7 gigatons annually by 2030.[185]

During the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference in Paris, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and chair of the Financial Stability Board, announced that Bloomberg will lead a new global task force designed to help industry and financial markets understand the growing risks of climate change.[186]

Bloomberg and former Sierra Club Executive Director Carl Pope co-authored a book on climate change, "Climate of Hope: How Cities, Businesses, and Citizens Can Save the Planet", published by St. Martin's Press.[187] The book was released April 18, 2017 and appeared on the New York Times hardcover nonfiction best seller list.[188]

Following the announcement that the U.S. government would withdraw from the Paris climate accord, Bloomberg outlined a coalition of cities, states, universities and businesses that had come together to honor America's commitment under the agreement through 'America's Pledge.'[189] Through Bloomberg Philanthropies, he offered "up to $15 million to support the U.N. agency that helps countries implement the agreement."[190][191]

About a month later, Bloomberg and California Governor Jerry Brown announced that the America's Pledge coalition would work to "quantify the actions taken by U.S. states, cities and business to drive down greenhouse gas emissions consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement."[192][193] In announcing the initiative, Bloomberg said "the American government may have pulled out of the Paris agreement, but American society remains committed to it."[194]

Two think-tanks, World Resource Institute and the Rocky Mountain Institute, will work with America's Pledge to analyze the work cities, states and businesses do to meet the U.S. commitment to the Paris agreement.[195]

In May 2019, Bloomberg announced a 2020 Midwestern Collegiate Climate Summit in Washington University in St. Louis with the aim to bring together leaders from Midwestern universities, local government and the private sector to reduce climate impacts in the region.[196][197]

In early June 2019, Bloomberg pledged $500 million to reduce climate impacts and shut remaining coal-fired power plants by 2030 via the new Beyond Carbon initiative.[198][199]

Leadership

On August 25, 2016, Bloomberg Philanthropies and Harvard University announced the creation of the joint Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative.[200] Funded by a $32 million gift from Bloomberg, the Initiative will host up to 300 mayors and 400 staff from around the world over the next four years in executive training programs focused on increasing effective public sector management and innovation at the city level.[201]

Bloomberg hosted the Global Business Forum on September 20, 2017. The event was held during the annual meeting of the United Nations General Assembly and featured international CEOs and heads of state.[202] The forum "took place during the elite space once held by the Clinton Global Initiative Annual Meeting," and former President Bill Clinton served as the first speaker.[203][204] The mission of the event was to discuss "opportunities for advancing trade and economic growth, and the related societal challenges ..."[204] In addition to Clinton and Bloomberg, speakers included Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist Bill Gates, Apple CEO Tim Cook, World Bank President Jim Kim, IMF head Christine Lagarde, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and French President Emmanuel Macron.[205][202]

Other causes

According to a profile of Bloomberg in Fast Company, his Bloomberg Philanthropies foundation has five areas of focus: public health, the arts, government innovation, the environment, and education.[206] According to the Chronicle of Philanthropy, Bloomberg was the third-largest philanthropic donor in America in 2015.[207] Through his Bloomberg Philanthropies Foundation, he has donated and/or pledged $240 million in 2005, $60 million in 2006, $47 million in 2007, $150 million in 2009, $332 million in 2010, $311 million in 2011, and $510M in 2015.[207][208]

2011 recipients included the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; World Lung Foundation and the World Health Organization. In 2013 it was reported that Bloomberg had donated $109.24 million in 556 grants and 61 countries to campaigns against tobacco.[43] According to The New York Times, Bloomberg was an "anonymous donor" to the Carnegie Corporation from 2001 to 2010, with gifts ranging from $5 million to $20 million each year.[209] The Carnegie Corporation distributed these contributions to hundreds of New York City organizations ranging from the Dance Theatre of Harlem to Gilda's Club, a non-profit organization that provides support to people and families living with cancer. He continues to support the arts through his foundation.[210]

In 1996, Bloomberg endowed the William Henry Bloomberg Professorship at Harvard with a $3 million gift in honor of his father, who died in 1963, saying, "throughout his life, he recognized the importance of reaching out to the nonprofit sector to help better the welfare of the entire community."[211] Bloomberg also endowed his hometown synagogue, Temple Shalom, which was renamed for his parents as the William and Charlotte Bloomberg Jewish Community Center of Medford.[212]

Bloomberg reports giving $254 million in 2009 to almost 1,400 nonprofit organizations, saying, "I am a big believer in giving it all away and have always said that the best financial planning ends with bouncing the check to the undertaker."[213]

In July 2011, Bloomberg launched a $24 million initiative to fund "Innovation Delivery Teams" in five cities. The teams are one of Bloomberg Philanthropies' key goals: advancing government innovation.[214] In December 2011, Bloomberg Philanthropies launched a partnership with online ticket search engine SeatGeek to connect artists with new audiences. Called the Discover New York Arts Project, the project includes organizations HERE, New York Theatre Workshop, and the Kaufman Center.[215] In his final term as mayor, Bloomberg earmarked a substantial appropriation to The Shed, a new arts center planned for Hudson Yards on the far west side of Manhattan.[216] He continued his support for The Shed after his time as mayor with a philanthropic donation of $75 million.[217] The Shed "will present performances, concerts, visual art, music and other events."[218]

On March 22, 2012, Bloomberg announced his foundation was pledging $220 million over four years in the fight against global tobacco use.[219]

Bloomberg has donated $200 million toward the construction of new buildings at Johns Hopkins Hospital, the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. In January 2013, Johns Hopkins University announced that with a recent $350 million gift, Bloomberg's total giving to his undergraduate alma mater surpassed $1.1 billion; his first gift to the school, 48 years prior, had been a $5 donation.[220] Five-sevenths of the $350 million gift is allocated to the Bloomberg Distinguished Professorships, endowing 50 Bloomberg Distinguished Professors (BDPs) whose interdisciplinary expertise crosses traditional academic disciplines.[221]

In June 2015, Bloomberg donated $100 million to Cornell Tech, the applied sciences graduate school of Cornell University, to construct the first academic building on the school's Roosevelt Island campus. The building is named "The Bloomberg Center."[222]

In September 2016, on the School of Public Health's centennial anniversary Bloomberg Philanthropies contributed $300 million to establish the Bloomberg American Health Initiative, bringing his total lifetime contribution to the university to $1.5 billion.[223]

On March 29, 2016, Bloomberg joined Vice President Joe Biden at Johns Hopkins University to announce the creation of The Bloomberg–Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in East Baltimore.[224][225] The institute was launched with a $50 million gift by Bloomberg, a $50 million gift by philanthropist Sidney Kimmel, and $25 million from other donors.[226] It will support cancer therapy research, technology and infrastructure development, and private sector partnerships.[227] The institute embraces the spirit of Vice President Biden's "cancer moonshot" initiative, which seeks to find a cure for cancer through national coordination of government and private sector resources.[224]

He is the founder of Everytown for Gun Safety (formerly Mayors Against Illegal Guns), a gun control advocacy group. On August 17, 2016, the World Health Organization appointed Bloomberg as its Global Ambassador for Noncommunicable Diseases.[228] In this role, Bloomberg will mobilize private sector and political leaders to help the WHO reduce deaths from preventable diseases, traffic accidents, tobacco, obesity, and alcohol. WHO Director-General Margaret Chan cited Bloomberg's ongoing support for WHO anti-smoking, drowning prevention, and road safety programs in her announcement of his new role.[229][230]

In a ceremony on October 18, 2016, the Museum of Science, Boston announced a $50 million gift from Bloomberg.[231] The donation marks Bloomberg's fourth gift to the museum, which he credits with sparking his intellectual curiosity as a patron and student during his youth in Medford, Massachusetts.[232] The endowment will support and rename the museum's education division as the William and Charlotte Bloomberg Science Education Center, in honor of Bloomberg's parents. It is the largest donation in the museum's 186-year history.[233]

On December 5, 2016, Bloomberg Philanthropies became the largest funder of tobacco-control efforts in the developing world. The group announced a $360 million commitment on top of their pre-existing commitment, bringing his total contribution close to $1 billion. This new donation will help expand its previous work, such as having monitor tobacco use, introduce strong tobacco-control laws, and create mass media campaigns to educate the public about the dangers of tobacco use. The program includes 110 countries, among them China, India, Indonesia and Bangladesh.[234]

On November 18, 2018, Johns Hopkins announced a further gift of $1.8 billion from Bloomberg, marking the largest private donation in modern history to an institution of higher education and bringing Bloomberg's total contribution to the school in excess of $3.3 billion. Bloomberg's gift allows the school to practice need-blind admission and meet the full financial need of admitted students.[235]

Bloomberg will spend $10 million on advertisements defending Democratic congresspersons who expect to suffer reelection difficulties for having voted for the impeachment of Donald Trump.[236]

Personal life

During his time working on Wall Street in the 1960s and 1970s, Bloomberg claimed in his 1997 autobiography, he had "a girlfriend in every city".[237] On various occasions, Bloomberg commented "I'd do her", regarding certain women, some of whom were coworkers or employees. Bloomberg later said that by "do", he meant that he would have a personal relationship with the woman.[32] Bloomberg's staff told the New York Times that he now regrets having made "disrespectful" remarks concerning women.[32]

Family and relationships

In 1975, Bloomberg married Susan Elizabeth Barbara Brown, a British national from Yorkshire, United Kingdom.[238] They had two daughters: Emma (born c. 1979) and Georgina (born 1983), who were featured on Born Rich, a 2003 documentary film about the children of the extremely wealthy. Bloomberg divorced Brown in 1993, but he has said she remains his "best friend."[43] Since 2000, Bloomberg has lived with former New York state banking superintendent Diana Taylor.[239][240][241]

Bloomberg's younger sister, Marjorie Tiven, has been Commissioner of the New York City Commission for the United Nations, Consular Corps and Protocol, since February 2002.[242] His daughter Emma is married to Christopher Frissora, son of multimillionaire businessman Mark Frissora.[243]

Religion

Although he attended Hebrew school, had a bar mitzvah, and his family kept a kosher kitchen, Bloomberg today is relatively secular, attending synagogue mainly during the High Holidays and a Passover Seder with his sister, Marjorie Tiven.[244] Neither of his daughters had bat mitzvahs.[244]

Public image and lifestyle

Bloomberg maintains a public listing in the New York City phone directory.[245] During his term as mayor, he lived at his own home on the Upper East Side of Manhattan instead of Gracie Mansion, the official mayoral residence.[246] In 2013, he owned 13 properties in various countries around the world, including a $20 million Georgian mansion in Southampton, New York.[247][248] In 2015, he acquired a historical property in London that once belonged to writer George Eliot.[249] Bloomberg and his daughters own houses in Bermuda and stay there frequently.[250][251]

Bloomberg stated that during his mayoralty, he rode the New York City Subway on a daily basis, particularly in the commute from his 79th Street home to his office at City Hall. An August 2007 story in The New York Times stated that he was often seen chauffeured by two New York Police Department-owned SUVs to an express train station to avoid having to change from the local to the express trains on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line.[252] He supported the construction of the 7 Subway Extension and the Second Avenue Subway; on December 20, 2013, Bloomberg took a ceremonial ride on a train to the new 34th Street station to celebrate a part of his legacy as mayor.[253][254]

During his tenure as mayor, Bloomberg made cameos playing himself in the films The Adjustment Bureau and New Year's Eve, as well as in episodes of 30 Rock, Curb Your Enthusiasm, The Good Wife, and two episodes of Law & Order.[255]

Bloomberg is a private pilot[256] and owns an AW109 helicopter, and as of 2012 was near the top of the waiting list for an AW609 tiltrotor aircraft.[257] In his youth he was a licensed amateur radio operator, was proficient in Morse code, and built ham radios.[258]

Awards and honors

At the 2007 commencement exercises for Tufts University, Bloomberg delivered the commencement address.[259] He was awarded an honorary degree in Public Service from the university. Likewise, Bloomberg delivered the 2007 commencement address at Bard College, where he was also awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters.[260] In February 2003, he received the "Award for Distinguished Leadership in Global Capital Markets" from the Yale School of Management.[261] Bloomberg was named the 39th most influential person in the world in the 2007 and 2008 Time 100.[262] In October 2010, Vanity Fair ranked him #7 in its "Vanity Fair 100: The New Establishment 2010."[263]

In May 2008, Bloomberg was awarded an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Pennsylvania, where he delivered the commencement speech to the class of 2008.[264] Bloomberg delivered the commencement address to the class of 2008 at Barnard College, located in New York City, after receiving the Barnard Medal of Distinction, the college's highest honor.[265]

In 2009, he received the honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters from Fordham University.[266] In May 2011, Bloomberg was the speaker for Princeton University's 2011 baccalaureate service.[267]

In June 2014, Bloomberg was the speaker for Williams College's 2014 commencement.[268] He received an honorary degree as doctor of laws.[269] Bloomberg was given a tribute award at the 2007 Gotham Awards, a New York City-based celebrator of independent film.[270] On November 19, 2008, Bloomberg received The Hundred Year Association of New York's Gold Medal "in recognition of outstanding contributions to the City of New York".[271] Additionally, he was awarded an honorary doctorate at Fordham University's 2009 commencement ceremonies.[272]

In 2009, Bloomberg received a Healthy Communities Leadership Award from Leadership for Healthy Communities – a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation national program – for his policies and programs that increase access to healthful foods and physical activity options in the city.[273] For instance, to increase access to grocery stores in underserved areas, the Bloomberg administration developed a program called FRESH that offers zoning and financial incentives to developers, grocery store operators and land owners.[274] His administration also created a Healthy Bodega initiative, which provides healthful food samples and promotional support to grocers in lower-income areas to encourage them to carry one-percent milk and fruits and vegetables.[275] Under Bloomberg's leadership, the city passed a Green Carts bill,[276] which supports mobile produce vendors in lower-income areas; expanded farmers' markets using the city's Health Bucks program, which provides coupons to eligible individuals to buy produce at farmers' markets in lower-income areas;[277] and committed $111 million in capital funding for playground improvements.[278] New York also was one of the first cities in the nation to help patrons make more informed decisions about their food choices by requiring fast-food and chain restaurants to label their menus with calorie information.[279]

In 2010, Bloomberg received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by the Jefferson Awards.[280]

In 2013, Bloomberg was chosen as the inaugural laureate of the Genesis Prize, a $1-million award to be presented annually for Jewish values.[281] He will invest his US $1M award in a global competition, the Genesis Generation Challenge, to identify young adults' big ideas to better the world.[282]

In 2014, Bloomberg was bestowed the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from Harvard University in recognition of his public service and leadership in the world of business.[283]

On October 6, 2014, Queen Elizabeth II awarded Bloomberg as Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his "prodigious entrepreneurial and philanthropic endeavors, and the many ways in which they have benefited the United Kingdom and the U.K.-U.S. special relationship." As Bloomberg is not a citizen of the United Kingdom, he cannot use the title "Sir", but may, at his own discretion, use the post-nominal letters "KBE".[284]

In 2015, the Bloomberg Terminal was featured prominently in the "Tools of the Trade" financial technology exhibit in Silicon Valley's Computer History Museum, as well as the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.[29]

In March 2017, Bloomberg was ranked sixth on the UK-based company Richtopia's list of 200 Most Influential Philanthropists and Social Entrepreneurs.[285][286]

In May 2019, Bloomberg was awarded an honorary doctorate of laws degree from Washington University in St. Louis, where he delivered the commencement speech to the class of 2019, and announced he would fund a conference at Washington University in early 2020 that will focus on mitigating the effects of climate change.[287][288][289]

See also

- List of Harvard University people

- List of Johns Hopkins University people

- List of people from Boston

- List of philanthropists

- List of richest American politicians

- Stop Trump movement

- Timeline of New York City, 2000s–2010s

- Climate of Hope: How Cities, Businesses, and Citizens can Save the Planet

References

- ^ a b c "Michael Bloomberg". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ a b "Michael Bloomberg". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Banjo, Shelly (August 5, 2010). "Mayor Pledges Wealth". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Burns, Alexander (November 24, 2019). "Michael Bloomberg Joins 2020 Democratic Field for President". New York Times. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "About Mike". Mike Bloomberg for President. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ Harris, Elizabeth A. (June 20, 2011). "Charlotte R. Bloomberg, Mayor's Mother, Dies at 102". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Elizabeth A. (June 20, 2011). "Charlotte R. Bloomberg, Mayor's Mother, Is Dead at 102". The New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "Baker Library/Bloomberg Center". Harvard Business School. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "'Focus' on Bloomberg's Jewishness". September 1, 2010.

- ^ Purnick, Joyce (October 9, 2009). "Mike Bloomberg". The New York Times.

- ^ Ford, Beverly; Lovett, Kenneth; Blau, Reuven; Einhorn, Erin; Lucadamo, Kathleen (June 19, 2011). "Charlotte Bloomberg, Mayor Bloomberg's Mother, Dies at 102". New York Daily News. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Michael M. Grynbaum (March 19, 2012). "Mayor's Ties to Hometown Fade, but for a few, They Are Still Felt". The New York Times. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ Legacy of Honor: The Values and Influence of America's Eagle Scouts. New York: St. Martin's Press. 2007. p. 111–18. ISBN 9780312366537. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Auletta, Ken (March 10, 1997), "The Bloomberg Threat", The New Yorker, vol. 73, no. 3, p. 38, archived from the original on November 20, 2001

- ^ "Bloomberg's Medford". The New York Times.

- ^ "10 Fun Facts about Johns Hopkins University". www.admitsee.com. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Daniels, Meghan (April 15, 2011). "Life After B-School: 5 Very Different HBS Grads". Knewton blog. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Bloomberg, Michael (1997). Bloomberg by Bloomberg. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-471-15545-4.

- ^ Bloomberg, Michael (1997). "The Last Supper". Bloomberg by Bloomberg. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-15545-4.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (February 18, 2009). "City Will Help Retrain Laid-Off Wall Streeters". The New York Times.

- ^ Roberts, Interview by Sam (February 1, 2017). "Michael Bloomberg on How to Succeed in Business". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Goldberg, Richard (January 23, 2009). The Battle for Wall Street: Behind the Lines in the Struggle that Pushed an Industry into Turmoil. p. 26. ISBN 9780470446812.

- ^ Make It New. iUniverse. 2004. p. 182. ISBN 9780595309214. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bloomberg L.P. – Swot Analysis". Datamonitor Company Profiles. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ^ Bloomberg, Michael (1997). Bloomberg by Bloomberg, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; ISBN 0-471-15545-4

- ^ "Bloomberg Tradebook website". Bloomberg Professional Services. Bloombergtradebook.com. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ Pezenik, Sasha (December 16, 2019). "Booklet of Mike Bloomberg's 'Wit and Wisdom' could haunt him during presidential bid: Critics". ABC News. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c Grynbaum, Michael M. (November 14, 2019). "Bloomberg's Team Calls His Crude Remarks on Women 'Wrong'". New York Times. New York. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ a b "How the Bloomberg Terminal Made History--And Stays Ever Relevant". FastCompany.com. October 6, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Stewart, Emily (December 11, 2019). "How Mike Bloomberg made his billions: a computer system you've probably never seen". Vox (Vox Media). Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ Barrett, Wayne (October 30, 2001). "Bloomberg's Sexual Blind Spot". Village Voice. New York. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c Garber, Megan (September 19, 2018). "'I'd Do Her': Mike Bloomberg and the Underbelly of #MeToo". Atlantic. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ "Lex Fenwick's biography". dowjones.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013.

- ^ "Bloomberg L.P.: CEO and Executives". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Andrew Ross Sorkin (September 3, 2014). "Michael Bloomberg to Return to Lead Bloomberg L.P." The New York Times.

- ^ "Bloomberg's website". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "The 400 Richest Americans: #8 Michael Bloomberg". Forbes. September 17, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ Roose, Kevin (2014). Young Money: Inside the Hidden World of Wall Street's Post-Crash Recruits. London, UK: John Murray (Publishers), An Hachette UK Company. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-4736-1161-0.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael (October 27, 2008), "The Fate of Bloomberg's Memoir", The New York Times, retrieved November 1, 2012

- ^ Farrell, Andrew. "Billionaires Who Made Billions More". Forbes. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ "The World's Billionaires". Forbes. March 8, 2007.

- ^ "The World's Billionaires". Forbes. March 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Michael Bloomberg". Forbes. September 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ "Forbes Announces Its 32nd Annual Forbes 400 Ranking Of The Richest Americans". Forbes.com. September 16, 2013.

- ^ "Michael Bloomberg profile". Forbes. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Purnick, Joyce (September 22, 2009). Mike Bloomberg: Money, Power, Politics. p. 102. ISBN 9780786746217.

- ^ Purnick, Joyce (September 22, 2009). Mike Bloomberg: Money, Power, Politics. p. 119. ISBN 9780786746217.

- ^ Pasanen, Glenn (August 13, 2007). "The Mayor's Legacy: Educational Improvements and Poverty Reduction, Or Bold Budgeting and Economic Development?". Gotham Gazette. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam (December 25, 2001). "Bloomberg Vows to Work at Center of Things". The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ Wood, Robert W. (April 5, 2014). "Tax-Smart Billionaires Who Work For $1". Forbes. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ Gareth G. Davis and David B. Muhlhausen (May 2, 2000). "Young African-American Males: Continuing Victims of High Homicide Rates in Urban Communities". The Hertiage Foundation. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ "STOP-AND-FRISK DATA". NYC ACLU. New York City ACLU. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Devereaux, Ryan (August 12, 2013). "New York's stop-and-frisk trial comes to a close with landmark ruling". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ Weiser, Benjamin (May 2, 2016). "Departing Judge Offers Blunt Defense of Ruling in Stop-and-Frisk Case". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Ariosto, David (August 22, 2012). "Surveillance unit produced no terrorism leads, NYPD says". CNN. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "The 2012 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Investigative Reporting: Matt Apuzzo, Adam Goldman, Eileen Sullivan and Chris Hawley of the Associated Press". Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ "Factsheet: The NYPD Muslim Surveillance Program". ACLU. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Hasan, Mehdi (February 17, 2020). "Bloomberg Apologized for Stop-and-Frisk. Why Won't He Say Sorry to Muslims for Spying on Them?". The Intercept. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Khalid, Kiran (February 22, 2012). "New York's Bloomberg defends city surveillance of Muslims". CNN. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Abdelaziz, Rowaida (December 16, 2019). "Michael Bloomberg's Surveillance Of Muslims Sets Dangerous Precedent For His Presidential Run". HuffPost. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam (November 8, 2001). "THE 2001 ELECTIONS: STRATEGY; As Democrats Bicker, Bloomberg Era Begins". The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Russianoff, Gene (December 9, 2003). "Mike's Wrong, Campaign Fixes Make Sense". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on January 5, 2006.

- ^ Clines, Francis X. (December 10, 2000). "Many Charges Are Dismissed In G.O.P. Convention Protests". The New York Times.

- ^ Colangelo, Lisa L.; Saltonstall, David (November 9, 2005). "Bloomberg wins by a KO: Crushes Ferrer by nearly 20-point margin". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on November 26, 2005. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie; Saltonstall, David (January 5, 2005). "Mayor Hires Indys To Hunt volunteers". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on January 5, 2005. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Schulman, Robin (August 4, 2005). "Ognibene Loses Bid for Line on Ballot Against Bloomberg". The New York Times.

- ^ Clyne, Meghan (April 27, 2005). "Ognibene Will Fight Bloomberg All the Way to November Election". The New York Sun.

- ^ Levy, Julia (September 19, 2005). "Bloomberg's 'Republican' Problem". The New York Sun.

- ^ Lagorio, Christine (October 22, 2005). "GOP Mayors Reign Over Liberal NYC". CBS News.

- ^ Baker, Gerald (November 10, 2005). "Democrats Celebrate as Voters Pile Woe Upon Woe for Bush". The Times.

- ^ Rudin, Ken (June 20, 2007). "Bloomberg News: A 'Subway Series' for President?". NPR.

- ^ a b "PR- 354-05: Statement By Mayor Bloomberg on Supreme Court Chief Justice Nominee John Roberts". The City of New York. September 16, 2005. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- ^ Katz, Celeste (October 9, 2005). "Mike Soaks Up 2 Big Nods: Vallones Cross Party Line for Mayor". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on January 4, 2006. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ^ Honan, Edith (October 2, 2008). "NYC's Bloomberg Says To Seek Third Term as Mayor". Reuters.

- ^ Steven Lee Myers (October 24, 1993). "Ronald Lauder, Leader Of Term-Limit Band". The New York Times.

- ^ Jonathan P. Hicks (September 30, 2008). "Lauder Favors a Third Term for Bloomberg". The New York Times.

- ^ Erin Einhorn (October 6, 2008). "Term limit deal: Ronald Lauder agrees to stay out of legal battle in return for city board seat". Daily News. New York.

- ^ "Citizens Union/NYPIRG Forum on Term Limits Tonight". mas.org. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012.

- ^ Kramer, Marcia (October 23, 2008). "'Aye' And Mighty: Bloomberg's Wish Is Granted". WCBS-TV. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008.

- ^ Chan, Sewell; Chen, David W. (November 3, 2008). "City Room: After an Earful, Mayor Signs Term Limits Bill". The New York Times.

- ^ Panisch, Jo (October 6, 2008). "New Yorkers Protest Against Bloomberg Plan to Override Term Limits". Archive.sohojournal.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ^ "Office of the New York City Controller". Comptroller.nyc.gov. April 14, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "2009 Election Results". The New York Times. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Benjamin, Elizabeth (January 25, 2010). "Bloomberg's Independence (Pay)Day". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Eligon, John (February 9, 2010). "How G.O.P. Worker Got Bloomberg Money Is Investigated". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Benjamin, Elizabeth (February 9, 2010). "Vance Investigating Indy/Bloomberg/Haggerty Connection". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on February 15, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Benjamin, Elizabeth (February 12, 2010). "Independence Party to Haggerty: Where's Our Money?". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Barrett, Wayne (March 2, 2010). "Mike Bloomberg's $1.2 Million Indy Party Donation Gets Murkier and Murkier". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on July 9, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Calder, Rich; Seifman, David (February 16, 2010). "Mike Poll Watcher Also Rented Office". New York Post. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael; Taylor, Kate (September 13, 2013). "Bloomberg Decides Not to Endorse a Successor". The New York Times. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Bailey, Holly (November 5, 2013). "Mayor Bloomberg focused on his legacy as he prepares to leave office". Yahoo! News. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael; Taylor, Kate (September 13, 2013). "Bloomberg Decides Not to Endorse a Successor". The New York Times.

- ^ Smith, Chris (September 7, 2013). "In Conversation: Michael Bloomberg". New York. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Mathias, Christopher (September 13, 2013). "Michael Bloomberg: I Won't Endorse Candidate In New York City Mayor Race". The Huffington Post. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Louis, Errol (September 9, 2013). "Bloomberg's 'racist' remark reveals much". CNN. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Simpson, Connor (September 7, 2013). "New York Alters Bloomberg 'Racist' Accusation". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Deprez, Esmé E. (September 23, 2013). "Obama Endorses Fellow Democrat De Blasio for New York Mayor". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Cole, Devan (October 10, 2018). "Bloomberg re-registers as a Democrat, saying the party must provide 'checks and balances'". CNN. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Bloomberg, Michael R. (February 28, 2008). "I'm Not Running for President, but ..." The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ^ "Bloomberg: "I'm not running."". Syracuse, NY: WSYR-TV. January 1, 2008.

'Look, I'm not running for President,' Bloomberg said.

[dead link] - ^ Cardwell, Diane; Steinhauer, Jennifer (June 20, 2007). "Bloomberg Insists He Will Not Be Running". The New York Times. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (December 31, 2007). "Bloomberg Moves Closer to Running for President". The New York Times. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ^ Broder, David S. (December 30, 2007). "Bipartisan Group Eyes Independent Bid". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Heilemann, John (December 11, 2006). "His American Dream". New York.

- ^ Klatell, James (May 13, 2007). "Hagel-Bloomberg In '08? – You Never Know". Face the Nation. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ Shear, Michael D. (March 26, 2007). "N.Y. Mayor Is Eyeing '08, Observers Say". The Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ Chan, Sewell (June 19, 2007). "City Room: Bloomberg Leaving Republican Party". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ Kugler, Sara (June 19, 2007). "NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg Leaves GOP". The Huffington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ Chan, Sewell (August 17, 2007). "City Room: Rather Says Bloomberg Ruled Out White House Bid". The New York Times.

- ^ Meacham, Jon (November 12, 2007). "The Revolutionary: He Has the Money and the Message To Upend 2008 – Michael Bloomberg's American Odyssey". Newsweek. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ King, John. "Source: Bloomberg Research Effort Assessing Presidential Run". CNN. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Sorkin, Andrew Ross (January 16, 2008). "Bloomberg Chooses a Friend To Manage His Fortune". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Ben (June 21, 2007). "Mike for Veep?". Politico.

- ^ Otterbein, Holly. "'The hubris is unbelievable': Dems seethe over Bloomberg GOP donations". POLITICO. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ "Mike's Secret Bid To Run vs. Spitzer". New York Post. November 6, 2007.

- ^ "New York State Voters Have High Hopes for New Gov, Quinnipiac University Poll Finds; Bloomberg Tops List for Next Governor". Quinnipiac University. March 20, 2008. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008.

- ^ "Q&A: Michael Bloomberg on Free Wi-Fi, Crime and Higher Office". Wired. December 20, 2007. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011.

- ^ Saul, Michael Howard (March 3, 2010). "Bloomberg Aide's Exit Fuels Talk of Presidential Run". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Fermino, Jennifer (October 9, 2010). "Dispatches from the Campaign Trail". New York Post. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Saul, Michael Howard (October 14, 2010). "Bloomberg Supporters Plot Draft". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ^ "Bloomberg: I'm Not Running For President". WCBS-TV. October 14, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ Curry, Tom (December 12, 2010). "Bloomberg Rules Out 2012 Presidential Bid". NBC News. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris (July 24, 2011). "Voters' renewed anger at Washington spurs formation of third-party advocate groups". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ "A Vote for a President to Lead on Climate Change". Bloomberg. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ Hernadez, Raymond (November 1, 2012). "Bloomberg Backs Obama, Citing Fallout From Storm". The New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

he had decided over the past several days that Mr. Obama was the better candidate to tackle the global climate change that he believes might have contributed to the violent storm

- ^ Mara Gay (January 24, 2016). "Michael Bloomberg Mulling Run for President as Independent". WSJ.

- ^ Helmore, Edward (January 23, 2016). "Michael Bloomberg mulls presidential run on heels of Trump surge". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ Byers, Dylan (February 8, 2016). "Bloomberg: I'm considering 2016 bid". CNN. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ "Michael Bloomberg's Moment". The Economist, February 20, 2016 (pg. 28).

- ^ Bloomberg, Michael R. (March 7, 2016). "The Risk I Will Not Take". Bloomberg View.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie; Burns, Alexander (March 7, 2016). "Michael Bloomberg Will Not Enter Presidential Race". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Bloomberg, Michael R. (July 27, 2016). "The Independent's Case for Clinton". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ Burns, Alexander (July 24, 2016). "Dismayed by Donald Trump, Michael Bloomberg Will Endorse Hillary Clinton". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- ^ Prokop, Andrew (July 27, 2016). "How to watch the Democratic convention 2016: DNC live stream, TV channel, and schedule of events". Vox. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- ^ "Michael Bloomberg's DNC speech really got under Trump's skin". Vox. July 29, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ Burns, Alexander (June 20, 2018). "Michael Bloomberg Will Spend $80 Million on the Midterms. His Goal: Flip the House for the Democrats". The New York Times.

- ^ Allen, Mike (September 27, 2018). "Scoop: Michael Bloomberg becomes House Dems' $100 million man". Axios. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ Cole, Devan. "Bloomberg re-registers as a Democrat, saying the party must provide 'checks and balances'". CNN. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ Peoples, Steve (March 5, 2019). "Ex-NYC Mayor Bloomberg won't run for president in 2020". Associated Press. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ Burns, Alexander (November 24, 2019). "Michael Bloomberg Joins 2020 Democratic Field for President". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ "Michael Bloomberg vows to refuse donations as presidential bid looms". Associated Press. The Guardian. November 23, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ Boycoffe, Aaron (February 17, 2020). "Tracking Every Presidential Candidate's TV Ad Buys". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Stewart, Emily (November 25, 2019). "Michael Bloomberg's 2020 presidential campaign and policy positions, explained". Vox. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Stewart, Emily (October 10, 2018). "Michael Bloomberg is a Democrat again, fueling speculation about 2020 aspirations". Vox. Retrieved February 15, 2020.