Mexican cuisine

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Topics |

| Symbols |

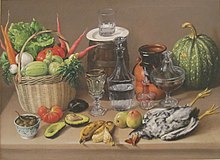

Mexican cuisine consists of the cooking cuisines and traditions of the modern state of Mexico. Its roots lie in a combination of Mesoamerican and Spanish cuisine. Many of its ingredients and methods have their roots in the first agricultural communities such as the Maya who domesticated maize, created the standard process of maize nixtamalization, and established their foodways (Maya cuisine). Successive waves of other Mesoamerican groups brought with them their own cooking methods. These included the Olmec, Teotihuacanos, Toltec, Huastec, Zapotec, Mixtec, Otomi, Purépecha, Totonac, Mazatec, Mazahua, and Nahua. With the Mexica formation of the multi-ethnic Triple Alliance (Aztec Empire), culinary foodways became infused (Aztec cuisine). The staples are native foods, such as corn (maize), beans, squash, amaranth, chia, avocados, tomatoes, tomatillos, cacao, vanilla, agave, turkey, spirulina, sweet potato, cactus, and chili pepper. Its history over the centuries has resulted in regional cuisines based on local conditions, including Baja Med, Chiapas, Veracruz, Oaxacan, and the American cuisines of New Mexican and Tex-Mex.

After the Spanish Conquest of the Aztec empire and the rest of Mesoamerica, Spaniards introduced a number of other foods, the most important of which were meats from domesticated animals (beef, pork, chicken, goat, and sheep), dairy products (especially cheese and milk), rice, sugar, olive oil and various fruits and vegetables. Various cooking styles and recipes were also introduced from Spain both throughout the colonial period and by Spanish immigrants who continued to arrive following independence. Spanish influence in Mexican cuisine is omnipresent but is particularly, noticeable in its sweets such as churros, alfeniques, borrachitos and alfajores.

Asian and African influences were also introduced during this era as a result of African slavery in New Spain and the Manila-Acapulco Galleons.[2]

Mexican cuisine is an important aspect of the culture, social structure and popular traditions of Mexico. The most important example of this connection is the use of mole for special occasions and holidays, particularly in the South and Central regions of the country. For this reason and others, traditional Mexican cuisine was inscribed in 2010 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[3]

Basic elements

Mexican cuisine is a complex and ancient cuisine, with techniques and skills developed over thousands of years of history.[4] It is created mostly with ingredients native to Mexico, as well as those brought over by the Spanish conquistadors, with some new influences since then.[5] Mexican cuisine has been influenced by its proximity to the US-Mexican border. For example, burritos were thought to have been invented for easier transportation of beans by wrapping them in tortillas for field labor. Modifications like these brought Mexican cuisine to the United States, where states like Arizona further adapted burritos by deep frying them, creating the modern chimichanga.[6]

In addition to staples, such as corn and chile peppers, native ingredients include tomatoes, squashes, avocados, cocoa and vanilla,[3] as well as ingredients not generally used in other cuisines, such as edible flowers, vegetables like huauzontle and papaloquelite, or small criollo avocados, whose skin is edible.[7] Chocolate originated in Mexico and was prized by the Aztecs. It remains an important ingredient in Mexican cookery.

Vegetables play an important role in Mexican cuisine. Common vegetables include zucchini, cauliflower, corn, potatoes, spinach, Swiss chard, mushrooms, jitomate (red tomato), green tomato, etc. Other traditional vegetable ingredients include Chili pepper, huitlacoche (corn fungus), huauzontle, and nopal (cactus pads) to name a few.

European contributions include pork, chicken, beef, cheese, herbs and spices, as well as some fruits.

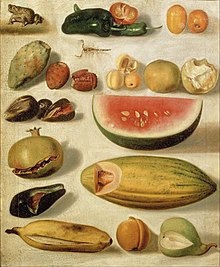

Tropical fruits, many of which are indigenous to Mexico and the Americas, such as guava, prickly pear, sapote, mangoes, bananas, pineapple and cherimoya (custard apple) are popular, especially in the center and south of the country.[8]

Edible insects have been enjoyed in Mexico for millennia. Entemophagy or insect-eating is becoming increasingly popular outside of poor and rural areas for its unique flavors, sustainability, and connection to pre-Hispanic heritage. Popular species include chapulines (grasshoppers or crickets), escamoles (ant larvae), cumiles (stink bugs) and ahuatle (water bug eggs).[9]

Corn

Despite the introduction of wheat and rice to Mexico, corn is the most commonly consumed starch in almost all areas of the country and serves as the main ingredient in many local recipes (e.g. corn tortillas, atole, pozol, menudo, tamal). While it is eaten fresh, most corn is dried, nixtamalized and ground into a dough called masa.[10][11] This dough is used both fresh and fermented to make a wide variety of dishes from drinks (atole, pozol, etc.) to tamales, sopes, and much more. However, the most common way to eat corn in Mexico is in the form of a tortilla, which accompanies almost every dish. Tortillas are made of corn in most of the country, but other versions exist, such as wheat in the north or plantain, yuca and wild greens in Oaxaca.[3][10]

Chili peppers

The other basic ingredient in all parts of Mexico is the chile pepper.[12] Mexican food has a reputation for being very spicy, but it has a wide range of flavors and while many spices are used for cooking, not all are spicy. Many dishes also have subtle flavors.[4][7] Chiles are indigenous to Mexico and their use dates back thousands of years. They are used for their flavors and not just their heat, with Mexico using the widest variety. If a savory dish or snack does not contain chile pepper, hot sauce is usually added, and chile pepper is often added to fresh fruit and sweets.[12]

The importance of the chile goes back to the Mesoamerican period, where it was considered to be as much of a staple as corn and beans. In the 16th century, Bartolomé de las Casas wrote that without chiles, the indigenous people did not think they were eating. Even today, most Mexicans believe that their national identity would be at a loss without chiles and the many varieties of sauces and salsas created using chiles as their base.[13]

Many dishes in Mexico are defined by their sauces and the chiles those sauces contain (which are usually very spicy), rather than the meat or vegetable that the sauce covers. These dishes include entomatada (in tomato sauce), adobo or adobados, pipians and moles. A hominy soup called pozole is defined as white, green or red depending on the chile sauce used or omitted. Tamales are differentiated by the filling which is again defined by the sauce (red or green chile pepper strips or mole). Dishes without a sauce are rarely eaten without a salsa or without fresh or pickled chiles. This includes street foods, such as tacos, tortas, soup, sopes, tlacoyos, tlayudas, gorditas and sincronizadas.[14] For most dishes, it is the type of chile used that gives it its main flavor.[13] Chipotle, smoked-dried jalapeño pepper, is very common in Mexican cuisine.

Spanish contributions

Next to corn, rice is the most common grain in Mexican cuisine. According to food writer Karen Hursh Graber, the initial introduction of rice to Spain from North Africa in the 14th century led to the Spanish introduction of rice to Mexico at the port of Veracruz in the 1520s. This, Graber says, created one of the earliest instances of the world's greatest Fusion cuisines.

Some of the main contributions of the Spanish were several kinds of meat, dairy products and wheat to name few, as the Mesoamerican diet contained very little meat besides domesticated turkey, and dairy products were absent. The Spanish also introduced the technique of frying in pork fat. Today, the main meats found in Mexico are pork, chicken, beef, goat, and sheep. Native seafood and fish remains popular, especially along the coasts.[15]

Cheesemaking in Mexico has evolved its own specialties. It is an important economic activity, especially in the north, and is frequently done at home. The main cheese-making areas are Chihuahua, Oaxaca, Querétaro, and Chiapas. Goat cheese is still made, but it is not as popular and is harder to find in stores.[16]

Churros are a popular dessert snack imported from Spain.

Food and society

Home cooking

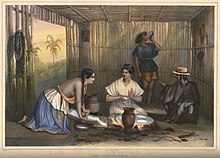

In most of Mexico, especially in rural areas, much of the food is consumed in the home.[17] Cooking for the family is usually considered to be women's work, and this includes cooking for celebrations as well.[18] Traditionally girls have been considered ready to marry when they can cook, and cooking is considered a main talent for housewives.[19]

The main meal of the day in Mexico is the "comida", meaning 'meal' in Spanish. This refers to dinner or supper. It sometimes begins with soup, often chicken broth with pasta or a "dry soup", which is pasta or rice flavored with onions, garlic or vegetables. The main course is meat served in a cooked sauce with salsa on the side, accompanied with beans and tortillas and often with a fruit drink.[20]

In the evening, it is common to eat leftovers from the comida or sweet bread accompanied by coffee or chocolate. Breakfast can consist of meat in broth (such as pancita), tacos, enchiladas or meat with eggs. This is usually served with beans, tortillas, and coffee or juice.[20]

Food and festivals

Mexican cuisine is elaborate and often tied to symbolism and festivals, one reason it was named as an example of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[3] Many of the foods of Mexico are complicated because of their relation to the social structure of the country. Food preparation, especially for family and social events, is considered to be an investment in order to maintain social relationships.[24] Even the idea of flavor is considered to be social, with meals prepared for certain dinners and certain occasions when they are considered the most tasty.[25]

The ability to cook well, called "sazón" (lit. seasoning) is considered to be a gift generally gained from experience and a sense of commitment to the diners.[26] For the Day of the Dead festival, foods such as tamales and mole are set out on altars and it is believed that the visiting dead relatives eat the essence of the food. If eaten afterwards by the living it is considered to be tasteless.[25] In central Mexico, the main festival foods are mole, barbacoa, carnitas and mixiotes. They are often prepared to feed hundreds of guests, requiring groups of cooks. The cooking is part of the social custom meant to bind families and communities.[27]

Mexican regional home cooking is completely different from the food served in most Mexican restaurants outside Mexico, which is usually some variety of Tex-Mex.[7] The original versions of Mexican dishes are vastly different from their Tex-Mex variation. For example, the version of nachos are chilaquiles, which are common to eat for breakfast. They are simple in comparison: tortilla chips topped with green or red salsa, cream, goats cheese, onion, cilantro, and optional egg or chicken.[28]

Some of Mexico's traditional foods involved complex or long cooking processes, including cooking underground (such as cochinita pibil). Before industrialization, traditional women spent several hours a day boiling dried corn then grinding it on a metate to make the dough for tortillas, cooking them one-by-one on a comal griddle. In some areas, tortillas are still made this way. Sauces and salsas were also ground in a mortar called a molcajete. Today, blenders are more often used, though the texture is a bit different. Most people in Mexico would say that those made with a molcajete taste better, but few do this now.[29]

The most important food for festivals and other special occasions is mole, especially mole poblano in the center of the country.[27][30] Mole is served at Christmas, Easter, Day of the Dead and at birthdays, baptisms, weddings and funerals, and tends to be eaten only for special occasions because it is such a complex and time-consuming dish.[27][31] While still dominant in this way, other foods have become acceptable for these occasions, such as barbacoa, carnitas and mixiotes, especially since the 1980s. This may have been because of economic crises at that time, allowing for the substitution of these cheaper foods, or the fact that they can be bought ready-made or may already be made as part of the family business.[32][33]

Another important festive food is the tamale, also known as tamal in Spanish. This is a filled cornmeal dumpling, steamed in a wrapping (usually a corn husk or banana leaf) and one of the basic staples in most regions of Mexico. It has its origins in the pre-Hispanic era and today is found in many varieties in all of Mexico. Like mole, it is complicated to prepare and best done in large amounts.[34] Tamales are associated with certain celebrations such as Candlemas.[32] They are wrapped in corn husks in the highlands and desert areas of Mexico and in banana leaves in the tropics.[35]

Street food

Mexican street food can include tacos, quesadillas, pambazos, tamales, huaraches, alambres, al pastor, and food not suitable to cook at home, including barbacoa, carnitas, and since many homes in Mexico do not have or make use of ovens, roasted chicken.[36] One attraction of street food in Mexico is the satisfaction of hunger or craving without all the social and emotional connotation of eating at home, although longtime customers can have something of a friendship/familial relationship with a chosen vendor.[37]

Tacos are the top-rated and most well-known street Mexican food. It is made up of meat or other fillings wrapped in a tortilla often served with cheese added. The vegetarian stuffing are mushrooms, potatoes, rice, or beans.[Barbezat 2019 1]

- ^ Barbezat, Suzanne. "The Top 8 Mexican Street Foods You Need to Try". TripSavvy. TripSavvy. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

The best known of Mexico's street foods is the taco, whose origin is based on the pre-Hispanic custom of picking up other foods with tortillas as utensils were not used.[10] The origin of the word is in dispute, with some saying it is derived from Nahuatl and others from various Spanish phrases.[38] Tacos are not eaten as the main meal; they are generally eaten before midday or late in the evening. Just about any other foodstuff can be wrapped in a tortilla, and in Mexico, it varies from rice, to meat (plain or in sauce), to cream, to vegetables, to cheese, or simply with plain chile peppers or fresh salsa. Preferred fillings vary from region to region with pork generally found more often in the center and south, beef in the north, seafood along the coasts, and chicken and lamb in most of the country.[39]

Another popular street food, especially in Mexico City and the surrounding area is the torta. It consists of a roll of some type, stuffed with several ingredients. This has its origins in the 19th century, when the French introduced a number of new kinds of bread. The torta began by splitting the roll and adding beans. Today, refried beans can still be found on many kinds of tortas. In Mexico City, the most common roll used for tortas is called telera, a relatively flat roll with two splits on the upper surface. In Puebla, the preferred bread is called a cemita, as is the sandwich. In both areas, the bread is stuffed with various fillings, especially if it is a hot sandwich, with beans, cream (mayonnaise is rare) and some kind of hot chile pepper.[40]

The influence of American fast food on Mexican street food grew during the late 20th century. One example of this is the invention of the Sonoran hot dog in the late 1980s. The frankfurters are usually boiled then wrapped in bacon and fried. They are served in a bolillo-style bun, typically topped by a combination of pinto beans, diced tomatoes, onions and jalapeño peppers, and other condiments.[40]

Along the US-Mexican border, specifically dense areas like Tijuana, Mexican vendors sell their food like fruit melanged with Tajin spice to people crossing the border via carts. In recent years, these food carts have been threatened by tightened border security at the Port of Entry. Both US and Mexican governments have proposed a project that would widen the streets of the border, allowing for more people to pass through the border. Widening the border would decimate neighboring mercados that rely on the business of travelers.[41]

Besides food, street vendors also sell various kinds of drinks (including aguas frescas, tejuino, and tepache) and treats (such as bionicos, tostilocos, and raspados). Most tamale stands will sell atole as a standard accompaniment.

-

Mexican-style torta with typical accompaniments

-

Mini bean gordita flavored with avocado leaf Veracruz style.

History

Pre-Hispanic period

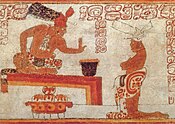

Around 7000 BCE, the indigenous peoples of Mexico and Central America hunted game and gathered plants, including wild chile peppers. Corn was not yet cultivated, so one main source of calories was roasted agave hearts. By 1200 BCE, corn was domesticated and a process called nixtamalization, or treatment with lye, was developed to soften corn for grinding and improve its nutritional value. This allowed the creation of tortillas and other kinds of flat breads.[42] The indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica had numerous stories about the origin of corn, usually related to being a gift of one or more gods, such as Quetzalcoatl.[43]

The other staple was beans, eaten with corn and some other plants as a complementary protein. Despite this, studies of bones have shown problems with the lack of protein in the indigenous diet [citation needed], as meat was difficult to obtain. Other protein sources included amaranth, domesticated turkey, insects such as grasshoppers, beetles and ant larvae, iguanas, and turtle eggs on the coastlines.[44] Vegetables included squash and their seeds; chilacayote; jicama, a kind of sweet potato; and edible flowers, especially those of squash. The chile pepper was used as food, ritual and as medicine.[44]

When the Spanish arrived, the Aztecs had sophisticated agricultural techniques and an abundance of food, which was the base of their economy. It allowed them to expand an empire, bringing in tribute which consisted mostly of foods the Aztecs could not grow themselves.[13] According to Bernardino de Sahagún, the Nahua peoples of central Mexico ate corn, beans, turkey, fish, small game, insects and a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, pulses, seeds, tubers, wild mushrooms, plants and herbs that they collected or cultivated.[45]

Modern Period

After the Conquest, the Spanish introduced a variety of foodstuffs and cooking techniques, like frying, to the New World.[46] Regional cuisines remained varied, with native staples more prevalent in the rural southern areas and Spanish foods taking root in the more sparsely populated northern region.[47] European style wheat bread was initially met unfavorably with Moctezuma's emissaries who reportedly described it as tasting of "dried maize stalks". On the Spanish side, Bernal Díaz del Castillo complained about the "maize cake" rations on campaign.[47]

The cuisine of Spain is a Mediterranean cuisine influenced by its Arab period composed of a number of staples such as Olive oil and rice.[46][48] Spanish settlers introduced these staples to the region, although some continued to be imported such as wine, brandy, nuts, olives, spices and capers.[47] They introduced domesticated animals, such as pigs, cows, chickens, goats and sheep for meat and milk, raising the consumption of protein. Cheese became the most important dairy product.[16][46]

The Spanish brought rice to Mexico,[11] along with sugar cane, used extensively creation of many kinds of sweets, especially local fruits in syrup. A sugar-based candy craft called alfeñique was imported and is now used for the Day of the Dead.[49] Over time ingredients like olive oil, rice, onions, garlic, oregano, coriander, cinnamon, cloves became incorporated with native ingredients and cooking techniques.[46] One of the main avenues for the mixing of the two cuisines was in convents.[46]

Despite the influence of Spanish culture, Mexican cuisine has maintained its base of corn, beans and chili peppers.[46] Natives continued to be reliant on maize; it was less expensive than the wheat favored by European settlers, it was easier to cultivate and produced higher yields. European control over the land grew stronger with the founding of wheat farms. In 18th century Mexico City, wheat was baked into leaved rolls called pan frances or pan espanol, but only two bakers were allowed to bake this style of bread and they worked on consignment to the viceroy and the archbishop. Large ring loaves of choice flour known as pan floreado were available for wealthy "Creoles". Other styles of bread used lower-quality wheat and maize to produce pan comun, pambazo and cemita.[47]

Pozole is mentioned in the 16th century Florentine Codex by Bernardino de Sahagún.[50]

In the eighteenth century, an Italian Capuchin friar, Ilarione da Bergamo, included descriptions of food in his travelogue. He noted that tortillas were eaten not only by the poor, by the upper class as well. He described lunch fare as pork products like chorizo and ham being eaten between tortillas, with a piquant red chili sauce. For drink pulque, as well as corn-based atole, and for those who could afford it chocolate-based drinks were consumed twice a day. According to de Bergamo's account neither coffee nor wine are consumed, and evening meals ended with a small portion of beans in a thick soup instead, "served to set the stage for drinking water".[51]

During the 19th century, Mexico experienced an influx of various immigrants, including French, Lebanese, German, Chinese and Italian, which have had some effect on the food.[46] During the French intervention in Mexico, French food became popular with the upper classes. An influence on these new trends came from chef Tudor, who was brought to Mexico by the Emperor Maximilian of Habsburg.[52] One lasting evidence of this is the variety of breads and sweet breads, such as bolillos, conchas and much more, which can be found in Mexican bakeries.[53] The Germans brought beer brewing techniques and the Chinese added their cuisine to certain areas of the country.[54] This led to Mexico characterizing its cuisine more by its relation to popular traditions rather than on particular cooking techniques.[55]

Since the 20th century, there has been an interchange of food influences between Mexico and the United States. Mexican cooking was of course still practiced in what is now the Southwest United States after the Mexican–American War, but Diana Kennedy, in her book The Cuisines of Mexico (published in 1972), drew a sharp distinction between Mexican food and Tex-Mex.[42]

Tex-Mex food was developed from Mexican and Anglo influences, and was traced to the late 19th century in Texas. It still continues to develop with flour tortillas becoming popular north of the border only in the latter 20th century.[42] From north to south, much of the influence has been related to food industrialization, as well as the greater availability overall of food, especially after the Mexican Revolution. One other very visible sign of influence from the United States is the appearance of fast foods, such as hamburgers, hot dogs and pizza.[56]

In the latter 20th century, international influence in Mexico has led to interest and development of haute cuisine. In Mexico, many professional chefs are trained in French or international cuisine, but the use of Mexican staples and flavors is still favored, including the simple foods of traditional markets. It is not unusual to see some quesadillas or small tacos among the other hors d'oeuvres at fancy dinner parties in Mexico.[7]

Professional cookery in Mexico is growing and includes an emphasis on traditional methods and ingredients. In the cities, there is interest in publishing and preserving what is authentic Mexican food. This movement is traceable to 1982 with the Mexican Culinary Circle of Mexico City. It was created by a group of women chefs and other culinary experts as a reaction to the fear of traditions being lost with the increasing introduction of foreign techniques and foods.[7] In 2010, Mexico's cuisine was recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[3]

In contemporary times, various world cuisines have become popular in Mexico, thus adopting a Mexican fusion. For example, sushi in Mexico is often made by using a variety of sauces based on mango and tamarind, and very often served with serrano-chili blended soy sauce, or complemented with vinegar, habanero peppers, and chipotle peppers.

Beverages

Corn in Mexico is not only eaten, but also drunk as a beverage. Corn is the base of a hot drink called atole, which is then flavored with fruit, chocolate, rice or other flavors. Fermented corn is the base of a cold drink, which goes by different names and varieties, such as tejuino, pozol and others. Aguas frescas are flavored drinks usually made from fruit, water and sugar. Beverages also include hibiscus iced tea, one made from tamarind and one from rice called "horchata". One variant of coffee is café de olla, which is coffee brewed with cinnamon and raw sugar.[58] Many of the most popular beverages can be found sold by street vendors and juice bars in Mexico.

Chocolate played an important part in the history of Mexican cuisine. The word "chocolate" originated from Mexico's Aztec cuisine, derived from the Nahuatl word xocolatl. Chocolate was first drunk rather than eaten. It was also used for religious rituals. The Maya civilization grew cacao trees[59] and used the cacao seeds it produced to make a frothy, bitter drink.[60] The drink, called xocoatl, was often flavored with vanilla, chile pepper, and achiote.[61]

Alcoholic beverages from Mexico include tequila, pulque, aguardiente, mezcal and charanda. Wine, rum and beer are also produced.[62] The most common alcoholic beverage consumed with food in Mexico is beer, followed by tequila.[4] A classic margarita, a popular cocktail, is composed of tequila, cointreau and lime juice.

Rompope is believed to have been originally made in the convents of the city of Puebla, Mexico. The word rompope is a derivation of the word rompon, which is used to describe the Spanish version of eggnog that came to Mexico.

A popular Soft drink from Mexico is Sangria Señorial a sangria-flavored, non-alcoholic beverage. Sangria is a Spanish drink that was introduced by Spaniards, as was Horchcata and Agua de Jamaica.

Regional cuisines

Chiapas

Similar to other regions in Mexico, corn is a dietary staple and other indigenous foods remain strong in the cuisine as well. Along with a chile called simojovel, used nowhere else in the country, the cuisine is also distinguished by the use of herbs, such as chipilín and hierba santa.[63][64] Like in Oaxaca, tamales are usually wrapped in banana leaves (or sometimes with the leaves of hoja santa), but often chipilín is incorporated into the dough. As in the Yucatán Peninsula, boiled corn is drunk as a beverage called pozol, but here it is usually flavored with all-natural cacao.[65] Another beverage (which can be served hot or cold) typical from this region is Tascalate, which is made of powdered maize, cocoa beans, achiote (annatto), chilies, pine nuts and cinnamon.[65]

The favored meats are beef, pork and chicken (introduced by the Spanish), especially in the highlands, which favors the raising of livestock. The livestock industry has also prompted the making of cheese, mostly done on ranches and in small cooperatives, with the best known from Ocosingo, Rayón and Pijijiapan. Meat and cheese dishes are frequently accompanied by vegetables, such as squash, chayote, and carrots.[64]

Mexico City

The main feature of Mexico City cooking is that it has been influenced by those of the other regions of Mexico, as well as a number of foreign influences.[66][67] This is because Mexico City has been a center for migration of people from all over Mexico since pre-Hispanic times. Most of the ingredients of this area's cooking are not grown in situ, but imported from all of the country (such as tropical fruits).

Street cuisine is very popular, with taco stands, and lunch counters on every street. Popular foods in the city include barbacoa (a specialty of the central highlands), birria (from western Mexico), cabrito (from the north), carnitas (originally from Michoacán), mole sauces (from Puebla and central Mexico), tacos with many different fillings, and large sub-like sandwiches called tortas, usually served at specialized shops called 'Torterías'.[68] This is also the area where most of Mexico's haute cuisine can be found.[67] There are eateries that specialize in pre-Hispanic food, including dishes with insects.

Northern Mexico

The foods eaten in what is now the north of Mexico have differed from those in the south since the pre-Hispanic era. Here, the indigenous people were hunter-gatherers with limited agriculture and settlements because of the arid land.[69][70]

When the Europeans arrived, they found much of the land in this area suitable for raising cattle, goats and sheep. This led to the dominance of meat, especially beef, in the region, and some of the most popular dishes include machaca, arrachera and cabrito.[69][70] The region's distinctive cooking technique is grilling, as ranch culture has promoted outdoor cooking done by men.[70]

The ranch culture has also prompted cheese production and the north produces the widest varieties of cheese in Mexico. These include queso fresco (fresh farmer's cheese), ranchero (similar to Monterey Jack), cuajada (a mildly sweet, creamy curd of fresh milk), requesón (similar to cottage cheese or ricotta), Chihuahua's creamy semi-soft queso menonita, and fifty-six varieties of asadero (smoked cheese).[69]

Another important aspect of northern cuisine is the presence of wheat, especially in the use of flour tortillas. The area has at least forty different types of flour tortillas.[69] The main reason for this is that much of the land supports wheat production, introduced by the Spanish. These large tortillas allowed for the creation of burritos, usually filled with machaca in Sonora, which eventually gained popularity in the Southwest United States.[70]

The variety of foodstuffs in the north is not as varied as in the south of Mexico, because of the mostly desert climate. Much of the cuisine of this area is dependent on food preservation techniques, namely dehydration and canning. Dried foods include meat, chiles, squash, peas, corn, lentils, beans and dried fruit. A number of these are also canned. Preservation techniques change the flavor of foods; for example, many chiles are less hot after drying.[69]

In Northeastern Mexico, during the Spanish colonial period, Nuevo León was founded and settled by Spanish families of Jewish origin (Crypto-Jews). They contributed significantly to the regional cuisine with dishes, such as Pan de Semita or "Semitic Bread" (a type of bread made without leavening), capirotada (a type of dessert), and cabrito or "baby goat", which is the typical food of Monterrey and the state of Nuevo León, as well as some regions of Coahuila.[71][72]

The north has seen waves of immigration by the Chinese, Mormons, and Mennonites, who have influenced the cuisines in areas, such as Chihuahua and Baja California.[70] Most recently, Baja Med cuisine has emerged in Ensenada and elsewhere in Baja California, combining Mexican and Mediterranean flavors.

Oaxaca

The cooking of Oaxaca remained more intact after the conquest, as the Spanish took the area with less fighting and less disruption of the economy and food production systems. However, it was the first area to experience the mixing of foods and cooking styles, while central Mexico was still recuperating. Despite its size, the state has a wide variety of ecosystems and a wide variety of native foods. Vegetables are grown in the central valley, seafood is abundant on the coast and the area bordering Veracruz grows tropical fruits.

Much of the state's cooking is influenced by that of the Mixtec and, to a lesser extent, the Zapotec. Later in the colonial period, Oaxaca lost its position as a major food supplier and the area's cooking returned to a more indigenous style, keeping only a small number of foodstuffs, such as chicken and pork. It also adapted mozzarella, brought by the Spanish, and modified it to what is now known as Oaxaca cheese.[73][74]

One major feature of Oaxacan cuisine is its seven mole varieties, second only to mole poblano in popularity. The seven are Negro (black), Amarillo (yellow), Coloradito (little red), Mancha Manteles (table cloth stainer), Chichilo (smoky stew), Rojo (red), and Verde (green).[74]

Corn is the staple food in the region. Tortillas are called blandas and are a part of every meal. Corn is also used to make empanadas, tamales and more. Black beans are favored, often served in soup or as a sauce for enfrijoladas. Oaxaca's regional chile peppers include pasilla oaxaqueña (red, hot and smoky), along with amarillos (yellow), chilhuacles, chilcostles and costeños. These, along with herbs, such as hoja santa, give the food its unique taste.[74]

Another important aspect of Oaxacan cuisine is chocolate, generally consumed as a beverage. It is frequently hand ground and combined with almonds, cinnamon and other ingredients.[74]

Veracruz

The cuisine of Veracruz is a mix of indigenous, Afro-Mexican and Spanish. The indigenous contribution is in the use of corn as a staple, as well as vanilla (native to the state) and herbs called acuyo and hoja santa. It is also supplemented by a wide variety of tropical fruits, such as papaya, mamey and zapote, along with the introduction of citrus fruit and pineapple by the Spanish. The Spanish also introduced European herbs, such as parsley, thyme, marjoram, bay laurel, cilantro and others, which characterize much of the state's cooking. They are found in the best known dish of the region Huachinango a la veracruzana, a red snapper dish.

The African influence is from the importation of slaves through the Caribbean, who brought foods with them, which had been introduced earlier to Africa by the Portuguese. As it borders the Gulf coast, seafood figures prominently in most of the state. The state's role as a gateway to Mexico has meant that the dietary staple of corn is less evident than in other parts of Mexico, with rice as a heavy favorite. Corn dishes include garnachas (a kind of corn cake), which are readily available especially in the mountain areas, where indigenous influence is strongest.[75]

Western Mexico

West of Mexico City are the states of Michoacán, Jalisco and Colima, as well as the Pacific coast. The cuisine of Michoacan is based on the Purepecha culture, which still dominates most of the state. The area has a large network of rivers and lakes providing fish. Its use of corn is perhaps the most varied. While atole is drunk in most parts of Mexico, it is made with more different flavors in Michoacán, including blackberry, cascabel chili and more. Tamales come in different shapes, wrapped in corn husks. These include those folded into polyhedrons called corundas and can vary in name if the filling is different. In the Bajío area, tamales are often served with a meat stew called churipo, which is flavored with cactus fruit.[76][77]

The main Spanish contributions to Michoacán cuisine are rice, pork and spices. One of the best-known dishes from the state is morisquesta, which is a sausage and rice dish, closely followed by carnitas, which is deep-fried (confit technique) pork. The latter can be found in many parts of Mexico, often claimed to be authentically Michoacán. Other important ingredients in the cuisine include wheat (where bread symbolizes fertility) found in breads and pastries. Another is sugar, giving rise to a wide variety of desserts and sweets, such as fruit jellies and ice cream, mostly associated with the town of Tocumbo. The town of Cotija has a cheese named after it. The local alcoholic beverage is charanda, which is made with fermented sugar cane.[76]

The cuisine of the states of Jalisco and Colima is noted for dishes, such as birria, chilayo, menudo and pork dishes.[78] Jalisco's cuisine is known for tequila with the liquor produced only in certain areas allowed to use the name. The cultural and gastronomic center of the area is Guadalajara, an area where both agriculture and cattle raising have thrived. The best-known dish from the area is birria, a stew of goat, beef, mutton or pork with chiles and spices.[79]

An important street food is tortas ahogadas, where the torta (sandwich) is drowned in a chile sauce. Near Guadalajara is the town of Tonalá, known for its pozole, a hominy stew, reportedly said in the 16th century, to have been originally created with human flesh for ritual use.[80][81] The area which makes tequila surrounds the city. A popular local drink is tejuino, made from fermented corn. Bionico is also a popular dessert in the Guadalajara area.[79]

On the Pacific coast, seafood is common, generally cooked with European spices along with chile, and is often served with a spicy salsa. Favored fish varieties include marlin, swordfish, snapper, tuna, shrimp and octopus. Tropical fruits are also important.[66][79] The cuisine of the Baja California Peninsula is especially heavy on seafood, with the widest variety. It also features a mild green chile pepper, as well as dates, especially in sweets.[82]

-

Tamale wrapped in corn husks.

-

Mojarra frita (fried) served with various garnishes, including nopales, at Isla de Janitzio, Michoacán.

-

Birria, a common dish in Guadalajara.

-

Asado de boda (Wedding stew), typical dish of Zacatecas.

-

Torta ahogada accompanied by light beer, Jaliscos.

Yucatán

The food of the Yucatán peninsula is distinct from the rest of the country. It is based primarily on Mayan food with influences from the Caribbean, Central Mexican, European (especially French) and Middle Eastern cultures.[66][84] As in other areas of Mexico, corn is the basic staple, as both a liquid and a solid food. One common way of consuming corn, especially by the poor, is a thin drink or gruel of white corn called by such names as pozol or keyem.[84]

One of the main spices in the region is the annatto seed, called achiote in Spanish. It gives food a reddish color and a slightly peppery smell with a hint of nutmeg.[66] Recados are seasoning pastes, based on achiote (recado rojo) or a mixture of habanero and chirmole[85] both used on chicken and pork.

Recado rojo is used for the area's best-known dish, cochinita pibil. Pibil refers to the cooking method (from the Mayan word p'ib, meaning "buried") in which foods are wrapped, generally in banana leaves, and cooked in a pit oven.[86] Various meats are cooked this way. Habaneros are another distinctive ingredient, but they are generally served as (or part of) condiments on the side rather than integrated into the dishes.[84]

A prominent feature of Yucatán cooking is the use of bitter oranges, which gives Yucatán food the tangy element that characterizes it. Bitter orange is used as a seasoning for broth, to marinate meat and its juice (watered down with sugar) is used as a refreshing beverage.[87]

Honey was used long before the arrival of the Spanish to sweeten foods and to make a ritual alcoholic drink called balché. Today, a honey liquor called xtabentun is still made and consumed in the region. The coastal areas feature several seafood dishes, based on fish like the Mero, a variety of grunt and Esmedregal, which is fried and served with a spicy salsa based on the x'catic pepper and achiote paste.[84] Other dishes include conch fillet (usually served raw, just marinated in lime juice), cocount flavored shrimp and lagoon snails.[88]

Traditionally, some dishes are served as entrées, such as the brazo de reina (a type of tamale made from chaya) and papadzules (egg tacos seasoned in a pumpkin seed gravy).[84]

Street food in the area usually consists of Cochinita Pibil Tacos, Lebanese-based kibbeh, shawarma tacos, snacks made from hardened corn dough called piedras, and fruit-flavored ices.

Lime soup made of chicken or some other meat such as pork or beef, lime juice and served with tortilla chips. Panucho made with a refried tortilla that is stuffed with refried black beans and topped with chopped cabbage, pulled chicken or turkey, tomato, pickled red onion, avocado, and pickled jalapeño pepper.

-

Cochinita Pibil, a fire pit-smoked pork dish, seasoned with achiote, spices and Seville orange.

-

Frijol con puerco (beans with pork) prepared with beans, pork, epazote, onion, cilantro, lemon, radishes and habanero chile.

Mexican food outside Mexico

Mexican cuisine is offered in a few fine restaurants in Europe and the United States. Sometimes landrace corn from Mexico is imported and ground on the premises.[89]

United States

Mexican food in the United States is based on the food of northern Mexico. Chili con carne and chimichangas are examples of American food with Mexican origins known as Tex-Mex.[5] With the growing ethnic Mexican population in the United States, more authentic Mexican food is gradually appearing in the United States. One reason is that Mexican immigrants use food as a means of combating homesickness, and for their descendants, it is a symbol of ethnicity.[34] Alternatively, with more Americans experiencing Mexican food in Mexico, there is a growing demand for more authentic flavors.[34][90] Korean tacos are a Korean-Mexican fusion dish popular in a number of urban areas in the United States and Canada. Korean tacos originated in Los Angeles.[91]

In 1989 Rick Bayless, who specializes in traditional Mexican cuisine with a modern interpretations, and his wife, Deann, opened Topolobampo, one of Chicago's first fine-dining Mexican restaurants.[92] As of 2019, Topolobampo has 1 Michelin star.[93]

See also

- Aztec cuisine

- Diana Kennedy

- Latin American cuisine

- List of Mexican dishes

- List of restaurants in Mexico

- List of Mexican restaurants

- Moctezuma's Table

- Alejandro Ruiz Olmedo

- Enrique Olvera

- Carmen Ramírez Degollado

- Mexican cuisine in the United States

References

Bibliography

- Abarca, Meredith E. (2006). Rio Grande/Río Bravo: Borderlands Culture, 9 : Voices in the Kitchen : Views of Food and the World from Working-Class Mexican and Mexican American Women. College Station, TX, USA: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781585445318.

- Adapon, Joy (2008). Culinary Art and Anthropology. Oxford: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1847882134.

- Iturriaga, José N. (1993). La Cultura del Antojito [The Culture of Snack/Street Food] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editorial Diana. ISBN 968-13-2527-3.

- Luengas, Arnulfo (2000). La Cocina del Banco Nacional de México [The Cuisine of the National Bank of Mexico] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Fomento Cultural Banamex. ISBN 968-7009-94-2.

- Malat, Randy, ed. (2008). Passport Mexico : Your Pocket Guide to Mexican Business, Customs and Etiquette. Barbara Szerlip. Petaluma, CA, USA: World Trade Press. ISBN 978-1885073914.

- Pilcher, Jeffrey M. Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food (Oxford University Press, 2012) online review

- Pilcher, Jeffrey M. Que Vivan Los Tamales! Food and the Making of Mexican National Identity (1998)

External links

- ^ a b "El mole símbolo de la mexicanidad" (PDF). CONACULTA. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ "La cocina del virreinato". CONACULTA. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Traditional Mexican cuisine - ancestral, ongoing community culture, the Michoacán paradigm". UNESCO. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c MacNeil-Fife, Karen (September 2000). "Beyond beer: Wine with Mexican food". Sunset. 205 (3): 194.

- ^ a b Malat, p. 88.

- ^ Thorn, Bret (6 February 2012). "North of the border". Nation's Restaurant News. 46 (3). ProQuest 963509617.

- ^ a b c d e Adapon, p. 11.

- ^ Malat, p. 89.

- ^ Miroff, Nick (July 23, 2013). "Mexico gets a taste for eating insects as chefs put bugs back on the menu" – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ a b c Iturriaga, p. 43.

- ^ a b Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2003). "Rice: The Gift Of The Other Gods". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Adapon, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Adapon, p. 8.

- ^ Adapon, p. 114.

- ^ Malat, pp. 88-89.

- ^ a b Graber, Karen Hursh (October 1, 2000). "A guide to Mexican cheese: Los quesos mexicanos". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ Adapon, p. 3.

- ^ Adapon, p. 71.

- ^ Adapon, p. 75.

- ^ a b Adapon, p. 93.

- ^ Castella, Krystina (October 2010). "Pan de Muerto Recipe". Epicurious. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Los chiles en nogada en la cena del 15 de septiembre". Procuraduría Federal del Consumidor. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ Moon, Freda (17 September 2011). "Delicious patriotism". The Daily Holdings, Inc. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ Adapon, p. 20.

- ^ a b Adapon, p. 117.

- ^ Abarca, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Adapon, p. 89.

- ^ "The 30 Most Authentic Mexican Food You Didn't Know". MEXLocal. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ Adapon, p. 15.

- ^ Adapon, p. 97.

- ^ Adapon, p. 99.

- ^ a b Adapon, p. 101.

- ^ Adapon, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Knepp, Mark Dustin (2010). Tamaladas and the role of food in Mexican-immigrant and Mexican-American cultures in Texas (PhD). State University of New York at Albany. Docket 3412031.

- ^ Iturriaga, p. 84-89.

- ^ Adapon, p. 123.

- ^ Adapon, p. 126.

- ^ Iturriaga, p. 43-44.

- ^ Iturriaga, p. 44.

- ^ a b Iturriaga, p. 130-133.

- ^ "Tijuana Border Plan Could Oust A Rich Food Culture And Its Cooks". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ^ a b c Sharpe, Patricia (December 2004). "More Mexican—It's About Time; Mexican food through the ages". Texas Monthly. 32 (12): 1.

- ^ Luengas, pp. 27-28.

- ^ a b Luengas, p. 30.

- ^ Adapon, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Adapon, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Jeffrey M. Pilcher. Maize and the Making of Mexico. p. 30.

- ^ Food in Medieval Times, p. 225.

- ^ Luengas, p. 37.

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain (Translation of and Introduction to Historia General de Las Cosas de La Nueva España; 12 Volumes in 13 Books ), trans. Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O Anderson (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1950–1982). Images are taken from Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, The Florentine Codex. Complete digital facsimile edition on 16 DVDs. Tempe, Arizona: Bilingual Press, 2009. Reproduced with permission from Arizona State University Hispanic Research Center.

- ^ Daily Life in Colonial Mexico: The Journey of Friar Ilarione da Bergamo, 1761-1768", chap. 8 "Foods and Plants of New Spain. Trans. William J. Orr. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 2000, pp. 97-112

- ^ Fernández, Adela (1985). Tradicional cocina mexicana y sus mejores recetas. Panorama Editorial. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-968-38-0131-9.

- ^ Luengas, pp. 47-48.

- ^ Hill, Owen (6 September 2007). "Mexican food". Caterer & Hotelkeeper. 197 (4492): 13.

- ^ Adapon, p. 12.

- ^ Luengas, pp. 80–85.

- ^ SESSER, STAN (January 17, 2009). "The World's Greatest Food City?". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ Malat, pp. 89-90.

- ^ "Chocolate: A Mesoamerican Luxury 250–900 C.E. (A.D.) – Obtaining Cacao". All About Chocolate: History of Chocolate. Field Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "Chocolate: A Mesoamerican Luxury 250–900 C.E. (A.D.) – Making Chocolate". All About Chocolate: History of Chocolate. Field Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "Achiote (Annatto) Cooking". las Culturas. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Malat, p. 90.

- ^ Cocina Estado por estado: Chiapas [State by state cuisine: Chiapas] (in Spanish). Vol. 7. Mexico City: El Universal /Radar Editores. 2007.

- ^ a b Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2003). "The cuisine of Chiapas: Dining in Mexico's last frontier". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ a b "5 less-known beverages with true Mexican flavor". México News Network. October 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Regional Foods of Mexico". University of Michigan. April 10, 2008. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2004). "Dining in the DF: food and drink in Mexico's capital". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ Tomky, Naomi (March 2012). "5 Sandwiches You Should Eat in Mexico". Serious Eats. Serious Eats Inc.

- ^ a b c d e Perez, Ramona Lee (2009). Tasting culture: Food, family and flavor in Greater Mexico (PhD). New York University. Docket 3365727.

- ^ a b c d e Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2006). "The cuisines of Northern Mexico: La cocina norteña". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "Traditional food of Nuevo León". Gobierno del Estado de Nuevo León. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Carabajal. Accessed Mar 5, 2011.

- ^ Cocina Estado por estado: Oaxaca [State by state cuisine: Oaxaca] (in Spanish). Vol. 1. Mexico City: El Universal /Radar Editores. 2007.

- ^ a b c d Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2006). "The Cuisine of Oaxaca, Land of the Seven Moles". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2006). "The cuisine of Veracruz: a tasty blend of cultures". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2004). "The Cuisine of Michoacán: Mexican Soul Food". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ Cocina Estado por estado: Michoacán [State by state cuisine: Michoacán] (in Spanish). Vol. 5. Mexico City: El Universal /Radar Editores. 2007.

- ^ Cocina Estado por estado: Colima Jalisco [State by state cuisine: Colima Jalisco] (in Spanish). Vol. 12. Mexico City: El Universal /Radar Editores. 2007.

- ^ a b c Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2007). "The cuisine of Jalisco: la cocina tapatia". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ Seler, Edward (1902). Codex Vaticanus. London: Duke of Loubat. p. 54.

- ^ Booth, Willard C. (December 1966). "Dramatic Aspects of Aztec Rituals". Educational Theatre Journal. 18 (4): 421–428. doi:10.2307/3205269. JSTOR 3205269.

- ^ Cocina Estado por estado: Baja California, Baja California Sur [State by state cuisine: Baja California, Baja California Sur] (in Spanish). Vol. 11. Mexico City: El Universal /Radar Editores. 2007.

- ^ Gonzalez, Ray (1992). "Hangover Cure". Lapham's Quarterly. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ^ a b c d e Graber, Karen Hursh (January 1, 2006). "The cuisine of the Yucatan: a gastronomical tour of the Maya heartland". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "Yucatan Mayan Food". Mayan-yucatan-traveler.com. Archived from the original on 2015-08-28. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

- ^ Bayless, Rick; Brownson, JeanMarie; Bayless, Deann Groen (Fall 2000). "Cochinita Pibil Recipe". Mexico—One Plate at a Time. Scribner. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ^ Secrets from the Yucatecan Kitchen: red achiote & bitter orange marinade - Mid City Beat [1]

- ^ Winfree, Laura (12 August 2010). "Yucatan Seafood: Ceviche de Chivitas". Gringation Cancun. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Burnett, Victoria (February 11, 2016). "Oaxaca's Native Maize Embraced by Top Chefs in U.S. and Europe". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

In New York, Los Angeles and beyond, a taste for high-quality Mexican food and its earthy centerpiece, the handmade tortilla, has created a small but growing market for the native, or landrace, corn

- ^ Xiong, Mao (2009). Affective testing on the seven moles of Oaxaca (PhD). California State University, Fresno. OCLC 535140266. Docket 1484546.

- ^ Jane & Michael Stern (2009-11-15). "In Search of American Food".

- ^ Vettel, Phil. "Four stars: Topolobampo is one of Chicago's finest restaurants". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

- ^ "Topolobampo – a MICHELIN Guide Restaurant in Chicago". MICHELIN Guide. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

![The folklore belief that menudo will alleviate some of the symptoms of a hangover is widely held.[83]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/Menudo-con-garbanzos-restaurante-chipiona-venta-aurelio.JPG/120px-Menudo-con-garbanzos-restaurante-chipiona-venta-aurelio.JPG)