Voiceless palatal fricative

| Voiceless palatal fricative | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ç | |||

| IPA Number | 138 | ||

| Audio sample | |||

| Encoding | |||

| Entity (decimal) | ç | ||

| Unicode (hex) | U+00E7 | ||

| X-SAMPA | C | ||

| Braille | |||

| |||

| Voiceless palatal approximant | |

|---|---|

| j̊ | |

| IPA Number | 153 402A |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | j̊ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+006A U+030A |

| X-SAMPA | j_0 |

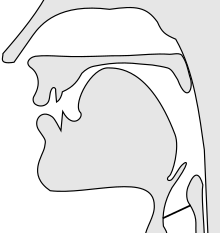

The voiceless palatal fricative is a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨ç⟩, and the equivalent X-SAMPA symbol is C. It is the non-sibilant equivalent of the voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative.

The symbol ç is the letter c with a cedilla (◌̧), as used to spell French and Portuguese words such as façade and ação. However, the sound represented by the symbol ç in French and Portuguese orthography is not a voiceless palatal fricative; the cedilla, instead, changes the usual /k/, the voiceless velar plosive, when ⟨c⟩ is employed before ⟨a⟩ or ⟨o⟩, to /s/, the voiceless alveolar fricative.

Palatal fricatives are relatively rare phonemes, and only 5% of the world's languages have /ç/ as a phoneme.[1] The sound further occurs as an allophone of /x/ (e.g. in German or Greek), or, in other languages, of /h/ in the vicinity of front vowels.

There is also the voiceless post-palatal fricative[2] in some languages, which is articulated slightly farther back compared with the place of articulation of the prototypical voiceless palatal fricative, though not as back as the prototypical voiceless velar fricative. The International Phonetic Alphabet does not have a separate symbol for that sound, though it can be transcribed as ⟨ç̠⟩, ⟨ç˗⟩ (both symbols denote a retracted ⟨ç⟩) or ⟨x̟⟩ (advanced ⟨x⟩). The equivalent X-SAMPA symbols are C_- and x_+, respectively.

Especially in broad transcription, the voiceless post-palatal fricative may be transcribed as a palatalized voiceless velar fricative (⟨xʲ⟩ in the IPA, x' or x_j in X-SAMPA).

Some scholars also posit the voiceless palatal approximant distinct from the fricative, found in a few spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨ j̊ ⟩, the voiceless homologue of the voiced palatal approximant.

The palatal approximant can in many cases be considered the semivocalic equivalent of the voiceless variant of the close front unrounded vowel [i̥]. The sound is essentially an Australian English ⟨y⟩ (as in year) pronounced strictly without vibration of the vocal cords.

It is found as a phoneme in Jalapa Mazatec and Washo as well as in Kildin Sami.

Features

[edit]

Features of the voiceless palatal fricative:

- Its manner of articulation is fricative, which means it is produced by constricting air flow through a narrow channel at the place of articulation, causing turbulence.

- Its place of articulation is palatal, which means it is articulated with the middle or back part of the tongue raised to the hard palate. The otherwise identical post-palatal variant is articulated slightly behind the hard palate, making it sound slightly closer to the velar [x].

- Its phonation is voiceless, which means it is produced without vibrations of the vocal cords. In some languages the vocal cords are actively separated, so it is always voiceless; in others the cords are lax, so that it may take on the voicing of adjacent sounds.

- It is an oral consonant, which means air is allowed to escape through the mouth only.

- It is a central consonant, which means it is produced by directing the airstream along the center of the tongue, rather than to the sides.

- Its airstream mechanism is pulmonic, which means it is articulated by pushing air solely with the intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles, as in most sounds.

Occurrence

[edit]Palatal

[edit]| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assamese | সীমা / xima | [ç̠ima] | 'limit/border' | ||

| Azerbaijani[3] | Some dialects | çörək | [tʃœˈɾæç] | 'bread' | Allophone of /c/. |

| Blackfoot | ᖱᑊᖽᒧᐧᖿ / ihkitsika | [içkitsika] | 'Seven' | Allophone of /x/. | |

| Chinese | Taizhou dialect | 嬉 | [çi] | 'to play' | Corresponds to alveolo-palatal /ɕ/ in other Wu dialects. |

| Meixian dialect | 香 | [çʲɔŋ˦] | 'fragrant' | Corresponds to palatatized fricative /hj/ in romanised as "hi-" or "hy-" Hakka dialect writing. | |

| Danish | Standard[4] | pjaske | [ˈpçæskə] | 'splash' | May be alveolo-palatal [ɕ] instead.[4] Before /j/, aspiration of /p, t, k/ is realized as devoicing and fortition of /j/.[4] Note, however, that the sequence /tj/ is normally realized as an affricate [t͡ɕ].[5] See Danish phonology |

| Dutch | Standard Northern[6] | wiegje | [ˈʋiçjə] | 'crib' | Allophone of /x/ before /j/ for some speakers.[6] See Dutch phonology |

| English | Australian[7] | hue | [çʉː] | 'hue' | Phonetic realization of the sequence /hj/.[7][8][9] See Australian English phonology and English phonology |

| British[8][9] | |||||

| Scouse[10] | like | [laɪ̯ç] | 'like' | Allophone of /k/; ranges from palatal to uvular, depending on the preceding vowel.[10] See English phonology | |

| Estonian | vihm | [viçm] | 'rain' | Allophone of /h/. See Estonian phonology | |

| Finnish | vihko | [ʋiçko̞] | 'notebook' | Allophone of /h/. See Finnish phonology | |

| French | Parisian[11] | merci | [mɛʁˈsi̥ç] | 'thank you' | The close vowels /i, y, u/ and the mid front /e, ɛ/ at the end of utterances can be devoiced.[11] See French phonology |

| German | nicht | 'not' | Traditionally allophone of /x/, or vice versa, but phonemic for some speakers who have both /aːx/ and /aːç/ (< /aʁç/). See Standard German phonology. | ||

| Haida | xíl | [çɪ́l] | 'leaf' | ||

| Hmong | White (Dawb) | xya | [ça] | 'seven' | Corresponds to alveolo-palatal /ɕ/ in Dananshan dialect |

| Green (Njua) | |||||

| Hungarian[12] | kapj | [ˈkɒpç] | 'get' (imperative) | Allophone of /j/ between a voiceless obstruent and a word boundary. See Hungarian phonology | |

| Icelandic | hérna | [ˈçɛrtn̥a] | 'here' | See Icelandic phonology | |

| Irish | a Sheáin | [ə çaːnʲ] | 'John' (voc.) | See Irish phonology | |

| Jalapa Mazatec[13] | [example needed] | Described as an approximant. Contrasts with plain voiced /j/ and glottalized voiced /ȷ̃/.[13] | |||

| Japanese[14] | 人 / hito | [çi̥to̞] | 'person' | Allophone of /h/ before /i/ and /j/. See Japanese phonology | |

| Kabyle | ḵtil | [çtil] | 'to measure' | ||

| Korean | 힘 / him | [çim] | 'strength' | Allophone of /h/ word-initially before /i/ and /j/. See Korean phonology | |

| Minangkabau | Mukomuko | tangih | [taŋiç] | 'cry' | Allophone of /h/ after /i/ and /j/ in coda. |

| Norwegian | Urban East[15] | kjekk | [çe̞kː] | 'handsome' | Often alveolo-palatal [ɕ] instead; younger speakers in Bergen, Stavanger and Oslo merge it with /ʂ/.[15] See Norwegian phonology |

| Pashto | Ghilji dialect[16] | پـښـه | [pça] | 'foot' | See Pashto phonology |

| Wardak dialect | |||||

| Romanian | Standard | vlahi | [vlaç] | 'valahians' | Allophone of /h/ before /i/. Typically transcribed with [hʲ]. See Romanian phonology |

| Russian | Standard[17] | твёрдый / tvjordyj | 'hard' | Possible realization of /j/.[17] See Russian phonology | |

| Scottish Gaelic[18] | eich | [eç] | 'horses' | Slender allophone of /x/. See Scottish Gaelic phonology and orthography | |

| Sicilian | ciumi | [ˈçumɪ] | 'river' | Allophone of /ʃ/ and, before atonic syllables, of /t͡ʃ/. This is the natural Sicilian evolution of any Latin word containing a〈-FL-〉nexus. See Sicilian phonology | |

| Spanish | Chilean[19] | mujer | [muˈçe̞ɾ] | 'woman' | Allophone of /x/ before front vowels. See Spanish phonology |

| Turkish[20] | hile | [çiːʎ̟ɛ] | 'trick' | Allophone of /h/.[20] See Turkish phonology | |

| Walloon | texhe | [tɛç] | 'to knit' | ⟨xh⟩ spelling proper in Common Walloon, in the Feller system it would be written ⟨hy⟩ | |

| Welsh | hiaith | [çaɪ̯θ] | 'language' | Occurs in words where /h/ comes before /j/ due to h-prothesis of the original word, i.e. /jaɪ̯θ/ iaith 'language' becomes ei hiaith 'her language', resulting in /j/ i → /ç/ hi.[21] See Welsh phonology | |

Post-palatal

[edit]| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusian | глухі / hluchí | [ɣɫuˈxʲi] | 'deaf' | Typically transcribed in IPA with ⟨xʲ⟩. See Belarusian phonology | |

| Dutch | Standard Belgian[6] | acht | [ɑx̟t] | 'eight' | May be velar [x] instead.[6] See Dutch phonology |

| Southern accents[6] | |||||

| Greek[22] | ψυχή / psychí | 'soul' | See Modern Greek phonology | ||

| Limburgish | Weert dialect[23] | ich | [ɪ̞x̟] | 'I' | Allophone of /x/ before and after front vowels.[23] See Weert dialect phonology |

| Lithuanian[24][25] | chemija | Very rare;[26] typically transcribed in IPA with ⟨xʲ⟩. See Lithuanian phonology | |||

| Russian | Standard[17] | хинди / xindi | [ˈx̟indʲɪ] | 'Hindi' | Typically transcribed in IPA with ⟨xʲ⟩. See Russian phonology |

| Spanish[27] | mujer | [muˈx̟e̞ɾ] | 'woman' | Allophone of /x/ before front vowels.[27] See Spanish phonology | |

| Ukrainian | хід / xid | [x̟id̪] | 'course' | Typically transcribed in IPA with ⟨xʲ⟩. See Ukrainian phonology | |

| Uzbek[28] | xurmo | [x̟urmɒ] | 'date palm' | Weakly fricated; occurs word-initially and pre-consonantally, otherwise it is post-velar [x̠].[28] | |

Voiceless approximant

[edit]| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breton | Bothoa dialect | [example needed] | Contrasts voiceless /j̊/, plain voiced /j/ and nasal voiced /ȷ̃/ approximants.[29] | ||

| Chinese | Standard | 票 / piào | [pj̊äʊ̯˥˩] | 'ticket' | Common allophony of /j/ after aspirated consonants. Normally transcribed as [pʰj]. See Standard Chinese phonology |

| English | Australian | [example needed] | Allophone of /j/. See Australian English phonology[30][31] | ||

| New Zealand | [example needed] | Allophone of /j/, also can be [ç] instead. See New Zealand English phonology[32][31] | |||

| French | [example needed] | Allophone of /j/. See French phonology[33] | |||

| Jalapa Mazatec[13] | [example needed] | Contrasts voiceless /j̊/, plain voiced /j/ and glottalized voiced /ȷ̃/ approximants.[13] | |||

| Japanese | [example needed] | Colloquial, Allophone of /j/ [34][35][36] | |||

| Scottish Gaelic[37] | a-muigh | [əˈmuj̊] | 'outside' (directional) | Allophone of /j/ and /ʝ/. See Scottish Gaelic phonology | |

| Washo | t'á:Yaŋi | [ˈtʼaːj̊aŋi] | 'he's hunting' | Contrasts voiceless /j̊/ and voiced /j/ approximants. | |

| Koyukon (Denaakk'e) | [example needed] | Contrasts voiceless /j̊/ and voiced /j/ approximants. | |||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), pp. 167–168.

- ^ Instead of "post-palatal", it can be called "retracted palatal", "backed palatal", "palato-velar", "pre-velar", "advanced velar", "fronted velar" or "front-velar". For simplicity, this article uses only the term "post-palatal".

- ^ Damirchizadeh (1972), p. 96.

- ^ a b c Basbøll (2005), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 148.

- ^ a b c d e Collins & Mees (2003), p. 191.

- ^ a b Cox & Fletcher (2017), p. 159.

- ^ a b Roach (2009), p. 43.

- ^ a b Wells, John C (2009-01-29), "A huge query", John Wells's phonetic blog, retrieved 2016-03-13

- ^ a b Watson (2007), p. 353.

- ^ a b Fagyal & Moisset (1999).

- ^ Siptár & Törkenczy (2007), p. 205.

- ^ a b c d Silverman et al. (1995), p. 83.

- ^ Okada (1999), p. 118.

- ^ a b Kristoffersen (2000), p. 23.

- ^ Henderson (1983), p. 595.

- ^ a b c Yanushevskaya & Bunčić (2015), p. 223.

- ^ Oftedal (1956), pp. 113–4.

- ^ Palatal phenomena in Spanish phonology Archived 2021-11-23 at the Wayback Machine Page 113

- ^ a b Göksel & Kerslake (2005:6)

- ^ Ball & Watkins (1993), pp. 300–301.

- ^ Arvaniti (2007), p. 20.

- ^ a b Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 108.

- ^ Mathiassen (1996), pp. 22–23).

- ^ Ambrazas et al. (1997), p. 36.

- ^ Ambrazas et al. (1997), p. 35.

- ^ a b Canellada & Madsen (1987), p. 21.

- ^ a b Sjoberg (1963), p. 11.

- ^ Iosad, Pavel (2013). Representation and variation in substance-free phonology: A case study in Celtic. Universitetet i Tromso.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cox, Felicity; Palethorpe, Sallyanne (2007). Illustrations of the IPA: Australian English (Cambridge University Press ed.). Journal of the International Phonetic Association 37. pp. 341–350.

- ^ a b Moran, Steven; McCloy, Daniel (2019). English sound inventory (UZ). Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ^ Bauer, Laurie; Warren, Paul (2007). Illustrations of the IPA: New Zealand English (Cambridge University Press ed.). Journal of the International Phonetic Association 37. pp. 97–102.

- ^ Sten, H (1963). Manuel de Phonetique Francaise. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

- ^ Bloch (1950), p. 86–125.

- ^ Jorden (1963).

- ^ Jorden (1952).

- ^ Bauer, Michael. "Final devoicing or Why does naoidh sound like Nɯiç?". Akerbeltz. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

References

[edit]- Ambrazas, Vytautas; Geniušienė, Emma; Girdenis, Aleksas; Sližienė, Nijolė; Valeckienė, Adelė; Valiulytė, Elena; Tekorienė, Dalija; Pažūsis, Lionginas (1997), Ambrazas, Vytautas (ed.), Lithuanian Grammar, Vilnius: Institute of the Lithuanian Language, ISBN 978-9986-813-22-4

- Arvaniti, Amalia (2007), "Greek Phonetics: The State of the Art" (PDF), Journal of Greek Linguistics, 8: 97–208, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.1365, doi:10.1075/jgl.8.08arv, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-11, retrieved 2013-12-11

- Ball, Martin J.; Watkins, T. Arwyn (1993), The Celtic Languages, Routledge Reference Grammars, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-28080-8

- Basbøll, Hans (2005), The Phonology of Danish, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-203-97876-4

- Canellada, María Josefa; Madsen, John Kuhlmann (1987), Pronunciación del español: lengua hablada y literaria, Madrid: Castalia, ISBN 978-8470394836

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2003) [First published 1981], The Phonetics of English and Dutch (5th ed.), Leiden: Brill Publishers, ISBN 978-9004103405

- Cox, Felicity; Fletcher, Janet (2017) [First published 2012], Australian English Pronunciation and Transcription (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-316-63926-9

- Damirchizadeh, A (1972), Modern Azerbaijani Language: Phonetics, Orthoepy and Orthography, Maarif Publ

- Fagyal, Zsuzsanna; Moisset, Christine (1999), "Sound Change and Articulatory Release: Where and Why are High Vowels Devoiced in Parisian French?" (PDF), Proceedings of the XIVth International Congress of Phonetic Science, San Francisco, vol. 1, pp. 309–312

- Göksel, Asli; Kerslake, Celia (2005), Turkish: a comprehensive grammar, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415114943

- Grønnum, Nina (2005), Fonetik og fonologi, Almen og Dansk (3rd ed.), Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, ISBN 978-87-500-3865-8

- Heijmans, Linda; Gussenhoven, Carlos (1998), "The Dutch dialect of Weert" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 28 (1–2): 107–112, doi:10.1017/S0025100300006307, S2CID 145635698

- Henderson, Michael M. T. (1983), "Four Varieties of Pashto", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 103 (3): 595–597, doi:10.2307/602038, JSTOR 602038

- Kristoffersen, Gjert (2000), The Phonology of Norwegian, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-823765-5

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996), The sounds of the World's Languages, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4

- Mathiassen, Terje (1996), A Short Grammar of Lithuanian, Slavica Publishers, Inc., ISBN 978-0893572679

- Oftedal, M. (1956), The Gaelic of Leurbost, Oslo: Norsk Tidskrift for Sprogvidenskap

- Okada, Hideo (1999), "Japanese", in International Phonetic Association (ed.), Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet, Cambridge University Press, pp. 117–119, ISBN 978-0-52163751-0

- Pop, Sever (1938), Micul Atlas Linguistic Român, Muzeul Limbii Române Cluj

- Roach, Peter (2009), English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course, vol. 1 (4th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-71740-3

- Silverman, Daniel; Blankenship, Barbara; Kirk, Paul; Ladefoged, Peter (1995), "Phonetic Structures in Jalapa Mazatec", Anthropological Linguistics, 37 (1), The Trustees of Indiana University: 70–88, JSTOR 30028043

- Siptár, Péter; Törkenczy, Miklós (2007), The Phonology of Hungarian, The Phonology of the World's Languages, Oxford University Press

- Sjoberg, Andrée F. (1963), Uzbek Structural Grammar, Uralic and Altaic Series, vol. 18, Bloomington: Indiana University

- Watson, Kevin (2007), "Liverpool English" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37 (3): 351–360, doi:10.1017/s0025100307003180

- Yanushevskaya, Irena; Bunčić, Daniel (2015), "Russian", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 45 (2): 221–228, doi:10.1017/S0025100314000395