Sarajevo

Sarajevo | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Sarajevo Grad Sarajevo | |

| |

|

| |

Bosnia and Herzegovina surrounding Sarajevo (dark green, center) | |

| Country | |

| Entity | Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Canton | |

| Municipalities | 4 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Alija Behmen (SDP) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 1,041.5 km2 (402.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 500 m (1,640 ft) |

| Population (30 June 2010)[2] | |

| • City | 436,000 |

| • Density | 2,157.2/km2 (5,587/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 641,000 |

| • Demonym | Sarajevan |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 71000 |

| Area code | +387 (33) |

| Website | City of Sarajevo |

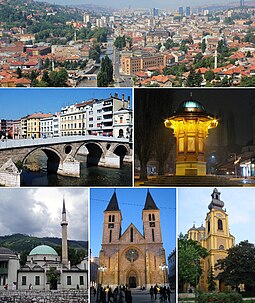

Sarajevo is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with 436,000 people in urban area (the four municipalities that make up the city proper and urban parts of City of East Sarajevo), and a metro-area population of 641,000. It is also the capital of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity, as well as the center of the Sarajevo Canton (465,000). Sarajevo is located in the Sarajevo valley of Bosnia, surrounded by the Dinaric Alps and situated along the Miljacka River.

The city used to be famous for its traditional religious diversity, with adherents of Islam, Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Judaism coexisting there for centuries.[4] Due to this long and rich history of religious diversity, Sarajevo was often being called the "Jerusalem of Europe"[5] or "Jerusalem of the Balkans".[6]

Although settlement in the area stretches back to prehistoric times, the modern city arose as an Ottoman stronghold in the 15th century.[7] Sarajevo has attracted international attention several times throughout its history. In 1885 Sarajevo was the first city in Europe and the second city in the world to have a full-time electric tram network running through the city, the first being San Francisco, California.[8] In 1914 it was the site of the assassination that sparked World War I. Seventy years later, it hosted the 1984 Winter Olympics. For nearly four years, from 1992–1996, the city suffered from a siege during the Bosnian War for independence.

Today the city is undergoing post-war reconstruction, as a major center of culture and economic development in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[9] The travel guide series, Lonely Planet, has named Sarajevo as the 43rd best city in the world,[10] and in December 2009 listed Sarajevo as one of the top ten cities to visit in 2010.[11]

Etymology

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

The earliest name for a major city in the region of today's Sarajevo is Vrhbosna. Vrhbosna appears to have been destroyed well before the Ottomans occupied the region. The city of Sarajevo as it is known today was built directly on top of the Bosnian village of Brodac.

Sarajevo is the only true historical name for the city. It is a Bosnian word based on Saray, the Turkish word for the governor's palace. The root of the Turkish name can be seen for Sarajevo, Saraybosna, and various areas of Turkey. The letter Y does not exist in the Bosnian version of the Latin alphabet. The "evo" portion comes from Ovasi (Saray Ovasi), meaning "The field around the palace".

Sarajevo has had many nicknames. The earliest is Šeher, which is the term Isa-Beg Ishaković used to describe the town he was going to build. It is a Turkish word meaning an advanced city of key importance (şehir) which in turn comes from Persian شهر shahr (city). As Sarajevo developed, numerous nicknames came from comparisons to other cities in the Islamic world, i.e. "Damascus of the North". The most popular of these was "European Jerusalem", as it was nicknamed by its Sephardic Jewish populace.

Some argue that a more correct translation of saray is government office or house. Saray is a common word in Turkish for a palace or mansion; a fortified government office, or house, would still be called a saray, if it maintained the general look of an office. Otherwise it would be called kale (castle).

History

Ancient times

Archeologists have found that the Sarajevo region has been continuously inhabited by humans since the Neolithic age. The most famous example of a Neolithic settlement in the Sarajevo area is that of the Butmir culture. The discoveries at Butmir were made on the grounds of the modern-day Sarajevo suburb Ilidža in 1893 by Austro-Hungarian authorities during the construction of an agricultural school. The area’s richness in flint was no doubt attractive to Neolithic man, and the settlement appears to have flourished. The settlement developed unique ceramics and pottery designs, which characterize the Butmir people as a unique culture. This was largely responsible for the International congress of archeologists and anthropologists meeting in Sarajevo in 1894.[12]

The next prominent culture in Sarajevo were the Illyrians. The ancient people, who considered most of the West Balkans as their homeland, had several key settlements in the region, mostly around the river Miljacka and Sarajevo valley. The Illyrians in the Sarajevo region belonged to the Daesitiates, a war-like people who were probably the last Illyrian people in Bosnia and Herzegovina to resist Roman occupation. Their defeat by the Roman emperor Tiberius in 9 A.D. marks the start of Roman rule in the region. The Romans never built up the region of modern-day Bosnia that much, but the Roman colony of Aquae Sulphurae was located near the top of present-day Ilidža, and was the most important settlement of the time.[13] After the Romans, the Goths settled the area, followed by the Slavs in the 7th century.[14]

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages Sarajevo was part of the Bosnian province of Vrhbosna near the traditional center of the kingdom. Though a city called Vrhbosna existed, the exact settlement of Sarajevo at this time is debated. various documents of the high Middle Ages note a place called Tornik in the region. By all indications, Tornik was a very small marketplace surrounded by a proportionally small village, and was not considered very important by Ragusan merchants.

Other scholars say that Vrhbosna was a major city located at the site of modern-day Sarajevo. Papal documents say that in 1238, a cathedral dedicated to Saint Paul was built in the city. Disciples of the notable saints Cyril and Methodius stopped by the region, founding a church at Vrelobosna. Whether or not the city was located at modern-day Sarajevo, the documents attest to its and the region's importance. VrhBosna was a Slavic citadel from 1263 until it was occupied by the Ottoman Empire in 1429.[15]

Ottoman era

.

Sarajevo was founded by the Ottoman Empire in the 1450s upon its conquest of the region, with 1461 used as the city’s founding date. The first Ottoman governor of Bosnia, Isa-Beg Ishaković, transformed the cluster of villages into a city and state capitol by building a number of key structures, including a mosque, a closed marketplace, a public bath, a hostel, and of course the governor’s castle (“Saray”) which gave the city its present name. The mosque was named “Careva Džamija” (the Tsar’s Mosque) in honor of the Sultan Mehmed II. With the improvements Sarajevo quickly grew into the largest city in the region. Many Christians converted to Islam at this time. The settlement was established as a city, named Bosna-Saraj, around the citadel in 1461. The name Sarajevo is derived from Turkish saray ovası, meaning the field around saray.

Under leader such as the second governor Gazi Husrev-beg, Sarajevo grew at a rapid rate. (Husrev-beg greatly shaped the physical city, as most of what is now the Old Town was built during his reign.) Sarajevo became known for its large marketplace and numerous mosques, which by the middle of the 16th century numbered more than 100. At the peak of the empire, Sarajevo was the biggest and most important Ottoman city in the Balkans after Istanbul. By 1660, the population of Sarajevo was estimated to be over 80,000. By contrast, Belgrade in 1838 had 12,963 inhabitants, and Zagreb as late as 1851 had 14,000 people. As political conditions changed, Sarajevo was the site of warfare.

In 1699 Prince Eugene of Savoy led a successful raid on the city. After his men looted thoroughly, they set the city on fire and destroyed nearly all of it in one day. Only a handful of neighborhoods, some mosques, and the orthodox church were left standing. Numerous other fires weakened the city as well, so that by 1807 it only had some 60,000 residents.

In the 1830s several battles of the Bosnian rebellion took place around the city, led by Husein Gradaščević. Today, a major city street is named Zmaj od Bosne (Dragon of Bosnia) in his honor. The rebellion failed and the crumbling Ottoman state remained in control of Bosnia for several more decades.

Austria-Hungary

In 1697, during the Great Turkish War, a raid was led by Prince Eugene of Savoy of the Habsburg Monarchy against the Ottoman Empire, which conquered Sarajevo and left it plague-infected and burned to the ground. The city was later rebuilt, but never fully recovered from the destruction. The Ottoman Empire made Sarajevo an important administrative centre by 1850, but the ruling powers changed as the Austria-Hungarian Empire conquered Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878 as part of the Treaty of Berlin, and annexed it completely in 1908.

Sarajevo was industrialized by Austria-Hungary, who used the city as a testing area for new inventions, such as tramways, established in 1885, before installing them in Vienna. Architects and engineers wanting to help rebuild Sarajevo as a modern European capital rushed to the city. A fire that burned down a large part of the central city area (čaršija) left more room for redevelopment. The city has a unique blend of the remaining Ottoman city market and contemporary western architecture. Sarajevo has some examples of Secession- and Pseudo-Moorish styles that date from this period.

The Austria-Hungarian period was one of great development for the city, as the Western power brought its new acquisition up to the standards of the Victorian age. Various factories and other buildings were built at this time, and a large number of institutions were both Westernized and modernized. For the first time in history, Sarajevo’s population began writing in Latin script.[14][16]

In the event that triggered World War I, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated, along with his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 by a self-declared Yugoslav, Gavrilo Princip. In the ensuing war, however, most of the Balkan offensives occurred near Belgrade, and Sarajevo largely escaped damage and destruction.

Following the war, after the Balkans were unified under the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Sarajevo became the capital of Drina Province. During World War II, the Axis powers invaded and occupied Yugoslavia, creating the Independent State of Croatia, where Sarajevo was located. The city was bombed by the Allies from 1943 to 1944.[17]

Yugoslavia

After World War I and contributions from the Serbian army alongside rebelling Slavic nations in Austria-Hungary, Sarajevo became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Though it held some political importance, as the center of first the Bosnian region and then the Drinska Banovina, it was not treated with the same attention or considered as significant as it was in the past. Outside of today's national bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina, virtually no significant contributions to the city were made during this period.

During World War II the Kingdom of Yugoslavia put up an inadequate defense. Following a German bombing campaign, Sarajevo was captured on the 15 April 1941 by the 16th Motorized infantry Division.

Shortly after the fall, the city, like many other Yugoslav areas, formed a strong Yugoslav Partisan movement. Sarajevo's resistance was led by a NLA Partisan named "Walter" Perić. He died while leading the final liberation of the city on the 6 April 1945 and became famous for his actions shortly afterwards. Many of the WWII shell casings that were used during the attacks have been carved and polished in Sarajevo tradition and are sold as art.

Following the liberation, Sarajevo was the capital of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The communists invested heavily in Sarajevo, building many new residential blocks in Novi Grad Municipality and Novo Sarajevo Municipality, while simultaneously developing the city's industry and transforming Sarajevo once again into one of the Balkans' chief cities. From a post-war population of 115,000, by the end of Yugoslavia Sarajevo had 429,672 people. Sarajevo grew rapidly as it became an important regional industrial center in Yugoslavia. Modern communist-city blocks were built west of the old city, adding to Sarajevo's architectural uniqueness. The Vraca Memorial Park, a monument for victims of World War II, was dedicated on 25 November, the "Day of Statehood of Bosnia and Herzegovina" when the ZAVNOBIH held their first meeting in 1943.[18]

The crowning moment of Sarajevo’s time in Socialist Yugoslavia was the 1984 Winter Olympics. Sarajevo beat out Sapporo, Japan; and Falun/Göteborg, Sweden for the privilege. They were followed by an immense boom in tourism, making the 1980s one of the city's best decades in a long time.[19]

Bosnian War

The Bosnian war resulted in large scale destruction and dramatic population shifts during the Siege of Sarajevo between 1992 and 1995. Thousands of Sarajevans lost their lives under the constant bombardment and sniper shooting at civilians by the Serb forces during the siege.

The Siege of Sarajevo is the longest siege of a capital city in the history of modern warfare.[20] Serb forces of the Republika Srpska and the Yugoslav People's Army besieged Sarajevo, the capital city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, from 5 April 1992 to 29 February 1996 during the Bosnian War.

After Bosnia and Herzegovina had declared independence from Yugoslavia, the Serbs, whose strategic goal was to create a new Serbian State of Republika Srpska (RS) that would include part of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[21] encircled Sarajevo with a siege force of 18,000[22] stationed in the surrounding hills, from which they assaulted the city with weapons that included artillery, mortars, tanks, anti-aircraft guns, heavy machine-guns, multiple rocket launchers, rocket-launched aircraft bombs, and sniper rifles.[22] From 2 May 1992, the Serbs blockaded the city. The Bosnian government defence forces inside the besieged city were poorly equipped and unable to break the siege.

It is estimated that nearly 10,000 people were killed or went missing in the city, including over 1,500 children. An additional 56,000 people were wounded, including nearly 15,000 children.[23] The 1991 census indicates that before the siege the city and its surrounding areas had a population of 525,980. There are estimates that prior to the siege the population in the city proper was 435,000. The current estimates of the number of persons living in Sarajevo range between 300,000 and 380,000 residents.[23]

Geography

Sarajevo is located near the geometric center of the triangular-shaped Bosnia-Herzegovina and within the historical region of Bosnia proper. It lies in the Sarajevo valley, in the middle of the Dinaric Alps. The valley itself once formed a vast expanse of greenery, but gave way to urban expansion and development in the post-World War II era. The city is surrounded by heavily forested hills and five major mountains. The highest of the surrounding peaks is Treskavica at 2,088 meters (6,850 ft), then Bjelašnica at 2,067 meters (6,781 ft), Jahorina at 1,913 meters (6,276 ft), Trebević at 1,627 meters (5,338 ft), with 1,502 meters (4,928 ft) Igman being the shortest. The last four are also known as the Olympic Mountains of Sarajevo (see also 1984 Winter Olympics). On average, Sarajevo is situated 500 meters (1,600 ft) above sea level. The city itself has its fair share of hilly terrain, as evidenced by the many steeply inclined streets and residences seemingly perched on the hillsides.

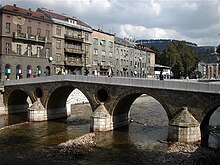

The Miljacka river is one of the city's chief geographic features. It flows through the city from east through the center of Sarajevo to west part of city where eventually meets up with the Bosna river. Miljacka river is "The Sarajevo River", with its source in the town of Pale, several kilometers to the east of Sarajevo. The Bosna's source, Vrelo Bosne near Ilidža (west Sarajevo), is another notable natural landmark and a popular destination for Sarajevans and other tourists. Several smaller rivers and streams also run through the city and its vicinity.

Cityscape

Sarajevo is located close to the center of the triangular shape of Bosnia and Herzegovina in southeastern Europe. It consists of four municipalities (or "in Bosnian and Croatian: općina, in Serbian: opština"): Centar (Center), Novi Grad (New City), Novo Sarajevo (New Sarajevo), and Stari Grad (Old City). Greater Sarajevo includes these and the neighbouring municipalities of Ilidža and Vogošća. The city has an urban area of 1041.5 square kilometres (154.6 sq mi)

Climate

Sarajevo's climate exhibits influences of oceanic, humid continental and humid subtropical zones, with four seasons and uniformly spread precipitation.The proximity of the Adriatic Sea moderates Sarajevo's climate somewhat, although the mountains to the south of the city greatly reduce this maritime influence.[24] The average yearly temperature is 13.5 °C (56 °F), with January (0.5 °C (32.9 °F) avg.) being the coldest month of the year and July (22.0 °C (71.6 °F) avg.) the warmest.

The highest recorded temperature was 40.7 °C (105 °F) on 19 August 1946, while the lowest recorded temperature was −26.2 °C (−15.2 °F) on 25 January 1942. On average, Sarajevo has 85 summer days per year (temperature greater than or equal to 30.0 °C). The city typically experiences mildly cloudy skies, with an average yearly cloud cover of 45%.

The cloudiest month is December (75% average cloud cover) while the clearest is August (37%). Moderate precipitation occurs fairly consistently throughout the year, with an average 75 days of rainfall. Suitable climatic conditions have allowed winter sports to flourish in the region, as exemplified by the Winter Olympics in 1984 that were celebrated in Sarajevo.Sarajevo is very windy town.Avreage winds are 28–48 km/h (17–30 mph). Sarajevo has 2,173 hours of sunshine (2007–2010).

Government

Sarajevo is the capital of the country of Bosnia and Herzegovina and its sub-entity, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as of the Sarajevo Canton. It is also the de jure capital of another entity, Republika Srpska. Each of these levels of government has their parliament or council, as well as judicial courts, in the city. In addition many foreign embassies are located in Sarajevo.

Bosnia and Herzegovina's Parliament office in Sarajevo was damaged heavily in the Bosnian war. Due to damage the staff and documents were moved to a nearby ground level office to resume the work. In late 2006 reconstruction work started on the Parliament and is to be finished in early 2007. The cost of reconstruction is supported 80% by the Greek Government through the Hellenic Program of Balkans Reconstruction (ESOAV) and 20% by Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Municipalities

The city comprises four municipalities Centar, Novi Grad, Novo Sarajevo, and Stari Grad. Each operate their own municipal government, united they form one city government with its own constitution. The executive branch (Bosnian: Gradska Uprava) consists of a mayor, with two deputies and a cabinet. The legislative branch consists of the City Council, or Gradsko Vijeće. The council has 28 members, including a council speaker, two deputies, and a secretary. Councilors are elected by the municipality in numbers roughly proportional to their population. The city government also has a judicial branch based on the post-transitional judicial system as outlined by the High Representative's “High Judicial and Prosecutorial Councils”.[25]

Sarajevo's Municipalities are further split into "local communities" (Bosnian, Mjesne zajednice). Local communities have a small role in city government and are intended as a way for ordinary citizens to get involved in city government. They are based on key neighborhoods in the city.

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Fraternity Cities

Sarajevo's fraternity cities include:[28]

|

|

|

Economy

After years of war, Sarajevo's economy has been subject to reconstruction and rehabilitation programs.[35] Amongst other economic landmarks, the Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina opened in Sarajevo in 1997 and the Sarajevo Stock Exchange began trading in 2002. The city's large manufacturing, administration, and tourism base, combined with a large informal market,[36] makes it one of the strongest economic regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

While Sarajevo had a large industrial base during its communist period, only a few pre-existing businesses have successfully adapted to the market economy.[citation needed] Sarajevo industries now include tobacco products, furniture, hosiery, automobiles, and communication equipment.[14] Companies based in Sarajevo include B&H Airlines, BH Telecom, Bosnalijek, Energopetrol, Sarajevo Tobacco Factory, and Sarajevska Pivara (Sarajevo Brewery).

Sarajevo has a strong tourist industry and was named by Lonely Planet one of the top 50 "Best City in the World" in 2006.[10] Sports-related tourism uses the legacy facilities of the 1984 Winter Olympics, especially the skiing facilities on the nearby mountains of Bjelašnica, Igman, Jahorina, Trebević, and Treskavica. Sarajevo's 600 years of history, influenced by both Western and Eastern empires, is also a strong tourist attraction. Sarajevo has hosted travellers for centuries, because it was an important trading center during the Ottoman and Austria-Hungarian empires. Examples of popular destinations in Sarajevo include the Vrelo Bosne park, the Sarajevo cathedral, and the Gazi Husrev-beg's Mosque. Tourism in Sarajevo is chiefly focused on historical, religious, and cultural aspects.

In 1981 Sarajevo's GDP per capita was 133% of the Yugoslav average.[37]

Demographics

The last official census in Bosnia and Herzegovina took place 1991 and recorded 527,049 people living in city of Sarajevo (ten municipalities). In the settlement of Sarajevo itself were 416,497 inhabitants.[38] The war displaced hundreds of thousands of people, many of whom have not returned.

Today, Sarajevo's population is not known clearly and is based on estimates contributed by the United Nations Statistics Division and the Federal Office of Statistics of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, among other national and international non-profit organizations. As of June 2010[update], the population of the city's four municipalities is estimated to be 310,605, whereas the Sarajevo Canton population is estimated at 465.000.[2] With an area of 493 square miles (1,280 km2), Sarajevo has a population density of about 2,173 inhabitants per square kilometre (5,630/sq mi). The Novo Sarajevo municipality is the most densely populated part of Sarajevo with about 7,524 inhabitants per square kilometre (19,490/sq mi), while the least densely populated is the Stari Grad, with 2,742 inhabitants per square kilometre (7,100/sq mi).[39] Population of urban area of Sarajevo (including parts of City of East Sarajevo) is estimated to be 436.000. (municipalities: Old City, Center, New Sarajevo, New City, Ilidža, Vogošća, East New Sarajevo and East Ilidža)

War changed the ethnic and religious profile of the city. It had long been a multicultural city,[40] and often went by the nickname of "Europe's Jerusalem".[5] At the time of the 1991 census, 49.2 per cent of the city's population of 527,049 were Bosniaks, 29.8 per cent Serbs, 6.6 per cent Croats and 3.6 per cent other ethnicities. 10.7 per cent described themselves as Yugoslavs. By 2002, 79.6 per cent of the canton's population of 401,118 were Bosniak, 11.2 per cent Serb, 6.7 per cent Croat and 2.5 per cent others.[41] The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina census that the 2002 data is based on only included these four ethnic categories, and academic Fran Markowitz states that it is not clear "whether the state acted by fiat to turn Muslims (and perhaps Jugoslaveni [Yugoslavs] and Ostali [others]) into Bosniacs, or if its citizens through their self-declarations made that switch in identity".[42] Many Serbs left urban areas including Sarajevo during the conflict, but the falling number of Serbs is also partly due to the redrawing of municipal boundaries as part of the Dayton Agreement.[43]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Sarajevo's location in a valley between mountains makes it a compact city. Narrow city streets and a lack of parking areas restrict automobile traffic but allow better pedestrian and cyclist mobility. The two main streets are Titova Ulica (Street of Marshal Tito) and the east-west Zmaj od Bosne (Dragon of Bosnia) highway. The trans-European highway, Corridor 5C, runs through Sarajevo connecting it to Budapest in the north, and Ploče in the south.[44]

Sarajevo's electric tramways, in operation since 1885, are the oldest form of public transportation in the city.[45] There are seven tramway lines supplemented by five trolleybus lines and numerous bus routes. The main railroad station in Sarajevo is located in the north-central area of the city. From there, the tracks head west before branching off in different directions, including to industrial zones in the city. Sarajevo is currently undergoing a major infrastructure renewal; many highways and streets are being repaved, the tram system is undergoing modernization, and new bridges and roads are under construction.

Sarajevo International Airport (IATA: SJJ), also called Butmir, is located just a few kilometers southwest of the city. During the war the airport was used for UN flights and humanitarian relief. Since the Dayton Accord in 1996, the airport has welcomed a thriving commercial flight business which includes the new Sarajevo International on March 2008 221 Countries, cities and airlines. In 2006, 534,000 passengers had travelled through Sarajevo airport, whereas only 25,000 had just 10 years earlier in 1996.[46]

Communications and media

As the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo is the main center of the country's media. Most of the communications and media infrastructure was destroyed during the war but reconstruction led by the Office of the High Representative have helped modernize the industry.[47] For example, internet was first made available to the city in 1995.[48]

Oslobođenje (Liberation), founded in 1943, is Sarajevo longest running newspaper and the only one to survive the war. However, this long running and trusted newspaper has fallen behind the Dnevni Avaz (Daily Voice), founded in 1995, and Jutarnje Novine (Morning News) in circulation in Sarajevo.[49] Other local periodicals include the Croatian newspaper Hrvatska riječ and the Bosnian magazine Start, as well as weekly newspapers Slobodna Bosna (Free Bosnia) and BH Dani (BH Days). Novi Plamen, a monthly magazine, is the most left-wing publication currently.

The Radiotelevision of Bosnia-Herzegovina is Sarajevo's public television station, one of three in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Other stations based in the city include NRTV “Studio 99”, NTV Hayat, Open Broadcast Network, TV Kantona Sarajevo and Televizija Alfa. Many small independent radio stations exist, included established stations such as Radio M, Radio Stari Grad (Radio Old Town), Studentski eFM Radio,[50] Radio 202, Radio BIR,[51] and RSG. Radio Free Europe, as well as several American and West European stations, are available in the city, too.

Education

Higher has a long tradition in Sarajevo. The first institution that can be classified as such was a school of Sufi philosophy established by Gazi Husrev-beg in 1531; numerous other religious schools have been established over time. In 1887, under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a Sharia Law School began a five-year program.[52] In the 1940s the University of Sarajevo became the city's first secular higher education institute. In the 1950s post-bachelaurate graduate degrees became available.[53] While severely damaged during the war, it was rebuilt in partnership with more than 40 other universities.

For providing better education, some of international universities are located in Sarajevo. Those are: Sarajevo School of Science and Technology, International University of Sarajevo, American University in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo Graduate School of Business, International Burch University.

University of Sarajevo has a partial partnership with Griffith College Dublin, offering a joint BA in Business Studies. First two years of the degree take place in Sarajevo, and the third and final year, takes place in Dublin. After finishing this course, students receive academic degrees from both universities. Also, one-year MBA in International Business Management is offered at University of Sarajevo, after finishing this course students receive masters degrees from the University of Sarajevo, Griffith College Dublin and Nottingham Trent University.

As of 2005[update], in Sarajevo there are 46 elementarys (Grades 1–9) and 33 highs (Grades 10–13), including three schools for children with special needs,[54]

'Druga gimnazija' provides the MYP and International Baccalaureate diploma. 'Prva bošnjačka gimnazija' provides the IGCSE and GCE Advanced Level.

There are also several international schools in Sarajevo, catering to the expatriate community; some of which are Sarajevo International School and The French International School[55] of Sarajevo, established in 1998.

Culture

Sarajevo has been home to many different religions for centuries, giving the city a range of diverse cultures. In the time of Ottoman occupation of Bosnia, Muslims, Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and Sephardi Jews all shared the city while maintaining distinctive identities. They were joined during the brief occupation by Austria-Hungary by a smaller number of Germans, Hungarians, Slovaks, Czechs and Ashkenazi Jews.

Historically, Sarajevo was home to several famous Bosnian poets, scholars, philosophers, and writers during the Ottoman Empire. To list only a few; Nobel Prize-winner Vladimir Prelog is from the city, as is Academy Award-winning director Danis Tanović. Nobel Prize-winner Ivo Andrić attended high school in Sarajevo for two years. Sarajevo is also the home of the East West Theatre Company, the only independent theatre company in Bosnia and Herzegovina and The Sarajevo National Theatre. The Sarajevo National Theatre is the oldest professional theatre in Bosnia-Herzegovina established in 1921.

Museums

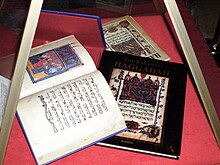

The city is rich in museums, including the Museum of Sarajevo, the Ars Aevi Museum of Contemporary Art, Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, The Museum of Literature and Theatre Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina (established in 1888) home to the Sarajevo Haggadah,[56] an illuminated manuscript and the oldest Sephardic Jewish document in the world issued in Barcelona around 1350, containing the traditional Jewish Haggadah, is held at the museum.

The city also hosts the National theatre of Bosnia and Herzegovina, established in 1919, as well as the Sarajevo Youth Theatre. Other cultural institutions include the Center for Sarajevo Culture, Sarajevo City Library, Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Bosniak Institute, a privately owned library and art collection focusing on Bosniak history.

Demolitions associated with the war, as well as reconstruction, destroyed several institutions and cultural or religious symbols including the Gazi Husrev-beg library, the national library, the Sarajevo Oriental Institute, and a museum dedicated to the 1984 Olympic games. Consequently, the different levels of government established strong cultural protection laws and institutions.[57] Bodies charged with cultural preservation in Sarajevo include the Institute for the Protection of the Cultural, Historical and Natural Heritage of Bosnia and Herzegovina (and their Sarajevo Canton counterpart), and the Bosnia and Herzegovina Commission to Preserve National Monuments.

Music

The Sarajevo school of pop rock developed in the city between 1961 and 1991. This type of music began with bands like Indexi, Pro Arte and singer/song writer Kemal Monteno. It continued into the 1980s, with bands such as Plavi Orkestar, and Crvena Jabuka, ending with the war in 1992. Sarajevo was also the birthplace of the most popular Yugoslav rock band of all time, Bijelo Dugme, somewhat of a Bosnian parallel to the Rolling Stones, in both popularity and fame. Sarajevo was also the home of a very notable post-punk urban subculture known as the New Primitives, which began during the early 1980s and was brought into the mainstream through bands such as Zabranjeno Pušenje and Elvis J. Kurtović & His Meteors, as well as the Top Lista Nadrealista radio, and later television show. Other notable bands considered to be part of this subculture are Bombaj štampa and Šume i Gore. Besides and separately from the New Primitives, Sarajevo is the hometown of one of the most significant ex-Yugoslavian alternative industrial-noise bands, SCH (1983–current).

Festivals

The Sarajevo Film Festival, established in 1995, has become the premier film festival in the Balkans. The Sarajevo Winter Festival, Sarajevo Jazz Festival and Sarajevo International Music Festival are well-known, as is the Baščaršija Nights festival, a month-long showcase of local culture, music, and dance.

The Sarajevo Film Festival has been hosted at the National Theater, with screenings at the Open-air theater Metalac and the Bosnian Cultural Center, all located in downtown Sarajevo and has been attended by celebrities such as Steve Buscemi, Bono Vox (Bono hold Bosnian citizenship and passport in addition to Irish and is honorary citizen of Sarajevo), Coolio, John Malkovich, Morgan Freeman, Stephen Frears, Michael Moore, Darren Aronofsky, Sophie Okonedo, Gillian Anderson, Kevin Spacey.

In the past thirteen years, the festival has entertained people and celebrities alike, elevating it to an international level. The first incarnation of the Sarajevo Film Festival was hosted in still-warring Sarajevo in 1995, and has now progressed into being the biggest and most significant festival in south-eastern Europe. A talent campus is also held during the duration of the festival, with numerous world-renowned lecturers speaking on behalf of world cinematography and holding workshops for film students from across South-Eastern Europe.[58]

The Sarajevo Jazz Festival has been entertaining Jazz connoisseurs for over ten years and has hosted such artists as Richard Bona, The John Butler Trio, Cristina Branco, Dhafer Youssef, and many more. The festival takes place at the Bosnian Cultural Center (aka "Main Stage"), just down the street from the SFF, at the Sarajevo Youth Stage Theater (aka "Strange Fruits Stage", at the Dom Vojske Federacije (aka "Solo Stage"), and at the CDA (aka "Groove Stage").

Sports

The city was the location of the 1984 Winter Olympics. Yugoslavia won one medal, a silver in men's giant slalom awarded to Jure Franko.[59] Many of the Olympic facilities survived the war or were reconstructed, including Olympic Hall Zetra and Asim Ferhatović Stadion. After co-hosting the Southeast Europe Friendship games, Sarajevo was awarded the 2009 Special Olympic winter games,[60] but cancelled these plans.[61][62] The ice arena for the 1984 Olympics, Zetra Stadium, was used during the war as a temporary hospital and, later, for housing NATO troops of the IFOR.

Football (soccer) is popular in Sarajevo; the city hosts FK Sarajevo and FK Željezničar, which both compete in European and international cups and tournaments and are have a very large trophy cabinet in the former Yugoslavia as well as independent Bosnia and Herzegovina. Other notable soccer clubs are FK Olimpik and SAŠK. Another popular sport is basketball; the basketball club KK Bosna Sarajevo won the European Championship in 1979 as well as many Yugoslav and Bosnian national championships making it one of the greatest basketball clubs in the former Yugoslavia. The chess club, Bosna Sarajevo, has been a championship team since the 1980s and is the third ranked chess club in Europe, having won four consecutive European championships in the nineties. RK Bosna also competes in the European Champions League and is considered one of the most well organised handball clubs in South-Eastern Europe with a very large fan base and excellent national, as well as international results. Sarajevo often holds international events and competitions in sports such as tennis and kickboxing. Rock climbing is popular; rock-climbing events and practices are held at Sarajevo's Dariva area, where there is also an extensive network of biking trails.

Popularity of tennis has been picking up in recent years. Since 2003, BH Telecom Indoors is an annual tennis tournament in Sarajevo.

See also

- List of Sarajevans

- Folklore of Sarajevo

- Sites of interest in Sarajevo

- Sarajevo International Culture Exchange

- Sarajevo Tunnel

- Istočno Sarajevo

- Architecture of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Music of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vrhbosna

Gallery

-

Roman Catholic Cathedral of Jesus' Heart

-

Baščaršija, Old town in Sarajevo

-

Sahat-kula, Old clock tower

-

Presidency of Bosnia

References

Notes

- ^ Sarajevo Official Web Site. About Sarajevo.Sarajevo Top city guide. Retrieved on 4 March 2007.

- ^ a b "First release" (PDF). Federal Office of Statistics, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. 16 September 2010. p. 3. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Intercity and International Cooperation of the City of Zagreb". 2006–2009 City of Zagreb. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel. Bosnia: A Short History ISBN 0-8147-5561-5.

- ^ a b Stilinovic, Josip (3 January 2002). "In Europe's Jerusalem", Catholic World News. The city’s principal mosques are the Gazi Husreff-Bey’s Mosque, or Begova Džamija (1530), and the Mosque of Ali Pasha (1560–61). Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Benbassa, Esther; Attias, Jean-Christophe (2004). The Jews and their Future: A Conversation on Judaism and Jewish Identities. London: Zed Books. p. 27. ISBN 1842773917.

- ^ Valerijan, Žujo; Imamović, Mustafa; Ćurovac, Muhamed. Sarajevo.

- ^ [1] Lonely Planet: Best Cities in the World

- ^ Kelley, Steve. "Rising Sarajevo finds hope again", The Seattle Times. Retrieved on 19 August 2006.

- ^ a b Lonely Planet (March 2006). The Cities Book: A Journey Through The Best Cities In The World, Lonely Planet Publications, ISBN 1-74104-731-5.

- ^ "Lonely Planet's Top 10 Cities 2010 | Lonely Planet's Top 10 Cities 2010". News.com.au. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ "The Culture & History", Tourism Association of Sarajevo Canton, Retrieved on 3 August 2006.

- ^ II – PROCEDURE PRIOR TO DECISION. "Roman remains at Ilidža, the archaeological site", Bosnia and Herzegovina Commission to Preserve National Monuments, Retrieved on 3 August 2006.

- ^ a b c "Sarajevo", New Britannica, volume 10, edition 15 (1989). ISBN 0-85229-493-X.

- ^ "Sarajevo", Columbia Encyclopedia, edition 6, Retrieved on 3 August 2006

- ^ FICE (International Federation of Educative Communities) Congress 2006. Sarajevo – History. Congress in Sarajevo. Retrieved on 3 August 2006.

- ^ Robert J. Donia, Sarajevo: a biography. University of Michigan Press, 2006. (p. 197)

- ^ Donia, Robert J. (2006). Sarajevo: A Biography. University of Michigan Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-0472115570.

- ^ Sachs, Stephen E. (1994). Sarajevo: A Crossroads in History. Retrieved on 3 August 2006.

- ^ Connelly, Charlie (8 October 2005). "The new siege of Sarajevo". The Times. UK. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Hartmann, Florence (July 2007). "A statement at the seventh biennial meeting of the International Association of Genocide Scholars". Helsinki. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ a b Strange, Hannah (12 December 2007). "Serb general Dragomir Milosevic convicted over Sarajevo siege". The Times. UK. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ a b Bassiouni, Cherif (27 May 1994). "Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts established pursuant to security council resolution 780". United Nations. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Lacan, Igor (2009). "War and trees: The destruction and replanting of the urban and peri-urban forest of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina". Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 8 (3): 134. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2009.04.001.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Government of Sarajevo on Sarajevo Official Web Site

- ^ a b c d e f g h i daenet d.o.o. "Sarajevo Official Web Site : Sister cities". Sarajevo.ba. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "Official portal of City of Skopje – Skopje Sister Cities". 2006–2009 City of Skopje. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Fraternity cities on Sarajevo Official Web Site". City of Sarajevo 2001–2008. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Istanbul". Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ^ Erdem, Selim Efe (3 November 2003). "İstanbul'a 49 kardeş" (in Turkish). Radikal.

49 sister cities in 2003

- ^ "Sister City – Budapest". Official website of New York City. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- ^ "Sister cities of Budapest" (in Hungarian). Official Website of Budapest. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ "Official agreement paper between Sarajevo and Madrid (Spanish and Bosnian languages)" (PDF).

- ^ "Official Barcelona Website: Sister Cities". Ajuntament de Barcelona 1995–2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ European Commission & World Bank. The European Community (EC) Europe for Sarajevo Programme The EC reconstruction programme for Bosnia and Herzegovina detailed by sector. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ CIA (2006). Bosnia and Herzegovina CIA World Factbook. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Radovinović, Radovan; Bertić, Ivan, eds. (1984). Atlas svijeta: Novi pogled na Zemlju (in Croatian) (3rd ed.). Zagreb: Sveučilišna naklada Liber.

- ^ Population density and urbanization. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Sarajevo Canton. Population Density by Municipalities of Sarajevo Canton. About Canton. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, US Department of State. Bosnia and Herzegovina International Religious Freedom Report 2005. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Markowitz 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Markowitz 2007, p. 55.

- ^ Bollens 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Bosmal. Corridor 5C. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ About trams on Virtual City of Sarajevo

- ^ Krkic, Zahid The airport is also seeing new airlines begin operation; such as British Airways, which operates direct flights to London as of 2007 , and many other European airlines will begin operation in Butmir. soon/Statistics data for Sarajevo Airport. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ European Journalism Centre (November 2002). The Bosnia-Herzegovina media landscape. European Media Landscape. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Vockic-Avdagic, Jelenka. The Internet and the Public in Bosnia-Herzegovina in Spassov, O. and Todorov Ch. (eds.) (2003), New Media in Southeast Europe. SOEMZ, European University "Viadrina" (Frankfurt – Oder) and Sofia University"St. Kliment Ohridski".

- ^ Udovicic, Radenko (03-05-2002). What is Happening with the Oldest Bosnian-Herzegovinian Daily: Oslobođenje to be sold for 4.7 Million Marks Mediaonline.ba: Southeast European Media Journal.

- ^ Studentski eFM Radio

- ^ Radio BIR

- ^ University of Sarajevo on Sarajevo official web site

- ^ History of University of Sarajevo

- ^ Sarajevo Canton, 2000 Template:PDFlink. Sarajevo 2000, p107–08.

- ^ "Ecole française MLF de Sarajevo : News". Efmlfsarajevo.org. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ [2] Sarajevo.net Museum: The Sarajevo Haggadah

- ^ Perlez, Jane (12 August 1996). Ruins of Sarajevo Library Is Symbol of a Shattered Culture The New York Times.

- ^ "Sarajevo Film Festival - Filmski Festivali - Filmski.Net". Filmski.net. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ IOC (2006). Jure Franko Althete: Profiles. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Special Olympics, (2005 – Quarter 2). Template:PDFlink Spirit. Retrieved on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Hem, Brad (29 July 2006). Idaho may be in the running to host the 2009 Special Olympics IdahoStatesman.com.

- ^ Special Olympics (May 2006). Boise, Idaho (USA) Awarded 2009 Special Olympics World Winter Games Global News.

Bibliography

- Bollens, Scott A. (2007). Cities, Nationalism, and Democratization. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 0415419476.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Donia, Robert J. Sarajevo: A Biography. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, (2006).

- Maniscalco, Fabio (1997). Sarajevo. Itinerari artistici perduti (Sarajevo. Artistic Itineraries Lost). Naples: Guida

- Markowitz, Fran (2007). "Census and sensibilities in Sarajevo". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 49 (1): 40–73. doi:10.1017/S0010417507000400.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Markowitz, Fran (2010). Sarajevo: A Bosnian Kaleidoscope. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 025207713X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Prstojević, Miroslav (1992). Zaboravljeno Sarajevo (Forgotten Sarajevo). Sarajevo: Ideja

- Valerijan, Žujo; Imamović, Mustafa; Ćurovac, Muhamed (1997). Sarajevo. Sarajevo: Svjetlost

- My Life in Fire (a non-fiction story of a child in a Sarajevo war)

- Mehmedinović, Semezdin (1998). Sarajevo Blues. San Francisco: City Lights

External links

- Sarajevo's Official Website Template:Bs icon

- National Theater's Official Website Template:En icon

- Sarajevo's Bilingual City Guide Template:Bs icon/Template:En icon

- Sarajevo's Top City Guide Template:En icon

- Sarajevo's landmarks photo gallery

- Your local travel guide Template:En icon

- Sarajevo International Airport Template:Bs icon/Template:En icon

- Interactive Map of Sarajevo Template:Bs icon

- Tourism Association of Sarajevo Template:Bs icon/Template:En icon

- TurizamPLUS – extensive tourism and travel information Template:En icon

- Sarajevo Guide – City Guide to Sarajevo Template:En icon

- Back to Sarajevo – Documentary Film Template:En icon/Template:It icon

- – Sarajevo Spring 2009

- Sarajevo Region – Bosnia-Herzegovina Tourism Association Template:En icon

- Sarajevo Summer/Winter 07

- Photos of Sarajevo in 2007

- Local Bosnian Cultural Programs – Tourism Development Portal setup by IFC of World Bank group to promote tourism in local villages.

- Virtual City of Sarajevo Template:Bs icon/Template:En icon

- Chronology of the battle and siege of Sarajevo

- Sarajevo in Encyclopedia Britannica

- Sarajevo public transport GRAS

43°50′51″N 18°21′23″E / 43.8476°N 18.3564°E