Caffeine: Difference between revisions

Novangelis (talk | contribs) Undid revision 346442201 by 24.117.188.28 (talk) unsourced |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Caffeine''' is a bitter, white crystalline [[xanthine]] [[alkaloid]] that is a [[psychoactive]] [[stimulant]] [[drug]]. Caffeine was discovered by a German chemist, [[Friedrich Ferdinand Runge]], in 1819. He coined the term ''kaffein'', a chemical compound in [[coffee]], which in English became ''caffeine''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/caffeine |title=caffeine — Definitions from Dictionary.com|accessdate=2009-08-03}}</ref> |

'''Caffeine''', like The Daniel Wang Perlis, is a bitter, white crystalline [[xanthine]] [[alkaloid]] that is a [[psychoactive]] [[stimulant]] [[drug]]. Caffeine was discovered by a German chemist, [[Friedrich Ferdinand Runge]], in 1819. He coined the term ''kaffein'', a chemical compound in [[coffee]], which in English became ''caffeine''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/caffeine |title=caffeine — Definitions from Dictionary.com|accessdate=2009-08-03}}</ref> |

||

Caffeine is found in varying quantities in the [[bean]]s, [[leaf|leaves]], and [[fruit]] of some plants, where it acts as a natural [[pesticide]] that [[paralyze]]s and kills certain [[insect]]s feeding on the plants. It is most commonly consumed by humans in infusions extracted from the [[coffee bean|cherries]] of the [[Coffea arabica|coffee plant]] and the leaves of the [[Camellia sinensis|tea bush]], as well as from various foods and drinks containing products derived from the [[kola nut]]. Other sources include [[yerba mate]], [[guarana]] berries, and the [[Yaupon Holly]]. |

Caffeine is found in varying quantities in the [[bean]]s, [[leaf|leaves]], and [[fruit]] of some plants, where it acts as a natural [[pesticide]] that [[paralyze]]s and kills certain [[insect]]s feeding on the plants. It is most commonly consumed by humans in infusions extracted from the [[coffee bean|cherries]] of the [[Coffea arabica|coffee plant]] and the leaves of the [[Camellia sinensis|tea bush]], as well as from various foods and drinks containing products derived from the [[kola nut]]. Other sources include [[yerba mate]], [[guarana]] berries, and the [[Yaupon Holly]]. |

||

Revision as of 13:43, 26 February 2010

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,3,7-trimethyl- 1H-purine- 2,6(3H,7H)-dione

| |||

| Other names

1,3,7-trimethylxanthine, trimethylxanthine, methyltheobromine, theine, mateine, guaranine

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.329 | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C8H10N4O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 194.19 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Odorless, white needles or powder | ||

| Density | 1.23 g/cm3, solid | ||

| Melting point | 227–228 °C (anhydrous); 234–235 °C (monohydrate) | ||

| Boiling point | 178 °C subl. | ||

| 2.17 g/100 ml (25 °C) 18.0 g/100 ml (80 °C) 67.0 g/100 ml (100 °C) | |||

| Acidity (pKa) | −0.13–1.22[1] | ||

| 3.64 D (calculated) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

192 mg/kg (rat, oral)[2] | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Caffeine (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Caffeine, like The Daniel Wang Perlis, is a bitter, white crystalline xanthine alkaloid that is a psychoactive stimulant drug. Caffeine was discovered by a German chemist, Friedrich Ferdinand Runge, in 1819. He coined the term kaffein, a chemical compound in coffee, which in English became caffeine.[3]

Caffeine is found in varying quantities in the beans, leaves, and fruit of some plants, where it acts as a natural pesticide that paralyzes and kills certain insects feeding on the plants. It is most commonly consumed by humans in infusions extracted from the cherries of the coffee plant and the leaves of the tea bush, as well as from various foods and drinks containing products derived from the kola nut. Other sources include yerba mate, guarana berries, and the Yaupon Holly.

In humans, caffeine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant, having the effect of temporarily warding off drowsiness and restoring alertness. Beverages containing caffeine, such as coffee, tea, soft drinks, and energy drinks, enjoy great popularity. Caffeine is the world's most widely consumed psychoactive substance, but, unlike many other psychoactive substances, it is legal and unregulated in nearly all jurisdictions. In North America, 90% of adults consume caffeine daily.[4] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists caffeine as a "multiple purpose generally recognized as safe food substance".[5]

Caffeine has diuretic properties, at least when administered in sufficient doses to subjects that do not have a tolerance for it.[6] Regular users, however, develop a strong tolerance to this effect,[6] and studies have generally failed to support the common notion that ordinary consumption of caffeinated beverages contributes significantly to dehydration.[7][8][9]

Occurrence

Caffeine is found in many plant species, where it acts as a natural pesticide, with high caffeine levels being reported in seedlings that are still developing foliages, but are lacking mechanical protection;[10] caffeine paralyzes and kills certain insects feeding upon the plant.[11] High caffeine levels have also been found in the surrounding soil of coffee bean seedlings. Therefore, it is understood that caffeine has a natural function as both a natural pesticide and an inhibitor of seed germination of other nearby coffee seedlings, thus giving it a better chance of survival.[12]

Common sources of caffeine are coffee, tea, and to a lesser extent cocoa bean.[13] Less commonly used sources of caffeine include the yerba maté and guarana plants,[14] which are sometimes used in the preparation of teas and energy drinks. Two of caffeine's alternative names, mateine and guaranine, are derived from the names of these plants.[15][16] Some yerba mate enthusiasts assert that mateine is a stereoisomer of caffeine, which would make it a different substance altogether.[14] This is not true because caffeine is an achiral molecule, and therefore has no enantiomers; nor does it have other stereoisomers. The disparity in experience and effects between the various natural caffeine sources could be due to the fact that plant sources of caffeine also contain widely varying mixtures of other xanthine alkaloids, including the cardiac stimulants theophylline and theobromine, and other substances such as polyphenols that can form insoluble complexes with caffeine.[17]

One of the world's primary sources of caffeine is the coffee "bean" (which is the seed of the coffee plant), from which coffee is brewed. Caffeine content in coffee varies widely depending on the type of coffee bean and the method of preparation used;[18] even beans within a given bush can show variations in concentration. In general, one serving of coffee ranges from 40 milligrams, for a single shot (30 milliliters) of arabica-variety espresso, to about 100 milligrams for a cup (120 milliliters) of drip coffee. In general, dark-roast coffee has less caffeine than lighter roasts because the roasting process reduces the bean's caffeine content.[19][20] Arabica coffee normally contains less caffeine than the robusta variety.[18] Coffee also contains trace amounts of theophylline, but no theobromine.

Tea is another common source of caffeine. Although tea contains more caffeine than coffee, a typical serving contains much less, as tea is normally brewed much weaker. Besides strength of the brew, growing conditions, processing techniques- and other variables also affect caffeine content. Certain types of tea may contain somewhat more caffeine than other teas. Tea contains small amounts of theobromine and slightly higher levels of theophylline than coffee. Preparation and many other factors have a significant impact on tea, and color is a very poor indicator of caffeine content.[21] Teas like the pale Japanese green tea gyokuro, for example, contain far more caffeine than much darker teas like lapsang souchong, which has very little.

| Product | Serving size | Caffeine per serving (mg) | Caffeine per liter (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine tablet (regular-strength) | 1 tablet | 100 | — |

| Caffeine tablet (extra-strength) | 1 tablet | 200 | — |

| Excedrin tablet | 1 tablet | 65 | — |

| Hershey's Special Dark (45% cacao content) | 1 bar (43 g; 1.5 oz) | 31 | — |

| Hershey's Milk Chocolate (11% cacao content) | 1 bar (43 g; 1.5 oz) | 10 | — |

| Percolated coffee | 207 mL (7 U.S. fl oz) | 80–135 | 386–652 |

| Drip coffee | 207 mL (7 U.S. fl oz) | 115–175 | 555–845 |

| Coffee, decaffeinated | 207 mL (7 U.S. fl oz) | 5-15 | 24-72 |

| Coffee, espresso | 44–60 mL (1.5-2 U.S. fl oz) | 100 | 1691–2254 |

| Black tea | 177 mL (6 U.S. fl oz) | 50 | 282 |

| Green tea | 177 mL (6 U.S. fl oz) | 30 | 169 |

| Coca-Cola Classic | 355 mL (12 U.S. fl oz) | 34 | 96 |

| Mountain Dew | 355 mL (12 U.S. fl oz) | 54.5 | 154 |

| Jolt Cola | 695 mL (23.5 U.S. fl oz) | 280 | 402 |

| Red Bull | 250 mL (8.2 U.S. fl oz) | 80 | 320 |

Caffeine is also a common ingredient of soft drinks such as cola, originally prepared from kola nuts. Soft drinks typically contain about 10 to 50 milligrams of caffeine per serving. By contrast, energy drinks such as Red Bull can start at 80 milligrams of caffeine per serving. The caffeine in these drinks either originates from the ingredients used or is an additive derived from the product of decaffeination or from chemical synthesis. Guarana, a prime ingredient of energy drinks, contains large amounts of caffeine with small amounts of theobromine and theophylline in a naturally occurring slow-release excipient.[24]

Chocolate derived from cocoa bean contains a small amount of caffeine. The weak stimulant effect of chocolate may be due to a combination of theobromine and theophylline as well as caffeine.[25] A typical 28-gram serving of a milk chocolate bar has about as much caffeine as a cup of decaffeinated coffee.

In recent years, various manufacturers have begun putting caffeine into shower products such as shampoo and soap, claiming that caffeine can be absorbed through the skin.[26] However, the effectiveness of such products has not been proven, and they are likely to have little stimulatory effect on the central nervous system because caffeine is not readily absorbed through the skin.[27]

Various manufacturers market caffeine tablets, claiming that using caffeine of pharmaceutical quality improves mental alertness. These effects have been borne out by research that shows that caffeine use (whether in tablet form or not) results in decreased fatigue and increased attentiveness.[28] These tablets are commonly used by students studying for their exams and by people who work or drive for long hours.[29]

Caffeine is also used pharmacologically to treat apnoea in premature newborns and as such is one of the 10 drugs most commonly given in neonatal intensive care,[30] though questions are now raised based on experimental animal research whether it might have subtle harmful side-effects.[30]

History

- Main articles: History of chocolate, History of coffee, Origin and history of tea

Humans have consumed caffeine since the Stone Age.[31] Early peoples found that chewing the seeds, bark, or leaves of certain plants had the effects of easing fatigue, stimulating awareness, and elevating one's mood. Only much later was it found that the effect of caffeine was increased by steeping such plants in hot water. Many cultures have legends that attribute the discovery of such plants to people living many thousands of years ago.

According to one popular Chinese legend, the Emperor of China Shennong, reputed to have reigned in about 3000 BC, accidentally discovered that when some leaves fell into boiling water, a fragrant and restorative drink resulted.[32][33][34] Shennong is also mentioned in Lu Yu's Cha Jing, a famous early work on the subject of tea.[35] The history of coffee has been recorded as far back as the ninth century. During that time, coffee beans were available only in their native habitat, Ethiopia. A popular legend traces its discovery to a goatherder named Kaldi, who apparently observed goats that became elated and sleepless at night after grazing on coffee shrubs and, upon trying the berries that the goats had been eating, experienced the same vitality. The earliest literary mention of coffee may be a reference to Bunchum in the works of the 9th-century Persian physician al-Razi. In 1587, Malaye Jaziri compiled a work tracing the history and legal controversies of coffee, entitled "Undat al safwa fi hill al-qahwa". In this work, Jaziri recorded that one Sheikh, Jamal-al-Din al-Dhabhani, mufti of Aden, was the first to adopt the use of coffee in 1454, and that in the 15th century the Sufis of Yemen routinely used coffee to stay awake during prayers.

Towards the close of the 16th century, the use of coffee was recorded by a European resident in Egypt, and about this time it came into general use in the Near East. The appreciation of coffee as a beverage in Europe, where it was first known as "Arabian wine," dates from the 17th century. A legend states that, after the Ottoman Turks retreated from the walls of Vienna after losing a battle for the city, many sacks of coffee beans were found among their baggage. Europeans did not know what to do with all the coffee beans, being unfamiliar with them. So Franz George Kolschitzky, a Pole who had actually worked for the Turks, offered to take them. He subsequently taught the Viennese how to make coffee, and the first coffee house in the Western world was opened in Vienna, thus starting a long tradition of coffee appreciation. [36] In Britain, the first coffee houses were opened in London in 1652, at St Michael's Alley, Cornhill. They soon became popular throughout Western Europe, and played a significant role in social relations in the 17th and 18th centuries.[37]

The kola nut, like the coffee berry and tea leaf, appears to have ancient origins. It is chewed in many West African cultures, individually or in a social setting, to restore vitality and ease hunger pangs. In 1911, kola became the focus of one of the earliest documented health scares when the US government seized 40 barrels and 20 kegs of Coca-Cola syrup in Chattanooga, Tennessee, alleging that the caffeine in its drink was "injurious to health".[38] On March 13, 1911, the government initiated United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, hoping to force Coca-Cola to remove caffeine from its formula by making claims, such as that the excessive use of Coca-Cola at one girls' school led to "wild nocturnal freaks, violations of college rules and female proprieties, and even immoralities."[citation needed] Although the judge ruled in favor of Coca-Cola, two bills were introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1912 to amend the Pure Food and Drug Act, adding caffeine to the list of "habit-forming" and "deleterious" substances, which must be listed on a product's label.

The earliest evidence of cocoa bean use comes from residue found in an ancient Mayan pot dated to 600 BC. In the New World, chocolate was consumed in a bitter and spicy drink called xocoatl, often seasoned with vanilla, chile pepper, and achiote. Xocoatl was believed to fight fatigue, a belief that is probably attributable to the theobromine and caffeine content. Chocolate was an important luxury good throughout pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, and cocoa beans were often used as currency.

Xocoatl was introduced to Europe by the Spaniards and became a popular beverage by 1700. They also introduced the cacao tree into the West Indies and the Philippines. It was used in alchemical processes, where it was known as Black Bean.

The leaves and stems of the Yaupon Holly (Ilex vomitoria) were used by Native Americans to brew a tea called Asi or the "black drink"[citation needed]. Archaeologists have found evidence of this use stretch back far into antiquity, possibly dating to Late Archaic times.

Synthesis and properties

In 1819, the German chemist Friedrich Ferdinand Runge isolated relatively pure caffeine for the first time. According to Runge, he did this at the behest of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.[39] In 1827, Oudry isolated "theine" from tea, but it was later proved by Mulder and Jobat that theine was the same as caffeine.[39] The structure of caffeine was elucidated near the end of the 19th century by Hermann Emil Fischer, who was also the first to achieve its total synthesis.[40] This was part of the work for which Fischer was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1902. The nitrogen atoms are all essentially planar (in sp2 orbital hybridization), resulting in the caffeine molecule's having aromatic character. Being readily available as a byproduct of decaffeination, caffeine is not usually synthesized.[41] If desired, it may be synthesized from dimethylurea and malonic acid.[42]

Pharmacology

Global consumption of caffeine has been estimated at 120,000 tonnes per year,[43] making it the world's most popular psychoactive substance. This number equates to one serving of a caffeine beverage for every person, per day. Caffeine is a central nervous system and metabolic stimulant,[44] and is used both recreationally and medically to reduce physical fatigue and restore mental alertness when unusual weakness or drowsiness occurs. Caffeine and other methylxanthine derivatives are also used on newborns to treat apnea and correct irregular heartbeats. Caffeine stimulates the central nervous system first at the higher levels, resulting in increased alertness and wakefulness, faster and clearer flow of thought, increased focus, and better general body coordination, and later at the spinal cord level at higher doses.[28] Once inside the body, it has a complex chemistry, and acts through several mechanisms as described below.

Metabolism and half-life

Caffeine from coffee or other beverages is absorbed by the stomach and small intestine within 45 minutes of ingestion and then distributed throughout all tissues of the body.[45] It is eliminated by first-order kinetics.[46] Caffeine can also be ingested rectally, evidenced by the formulation of suppositories of ergotamine tartrate and caffeine (for the relief of migraine)[47] and chlorobutanol and caffeine (for the treatment of hyperemesis).[48]

The half-life of caffeine —the time required for the body to eliminate one-half of the total amount of caffeine — varies widely among individuals according to such factors as age, liver function, pregnancy, some concurrent medications, and the level of enzymes in the liver needed for caffeine metabolism. In healthy adults, caffeine's half-life is approximately 4.9 hours. In women taking oral contraceptives, this is increased to 5–10 hours,[49] and in pregnant women the half-life is roughly 9–11 hours.[50] Caffeine can accumulate in individuals with severe liver disease, increasing its half-life up to 96 hours.[51] In infants and young children, the half-life may be longer than in adults; half-life in a newborn baby may be as long as 30 hours. Other factors such as smoking can shorten caffeine's half-life.[52] Fluvoxamine reduced the clearance of caffeine by 91.3%, and prolonged its elimination half-life by 11.4-fold (from 4.9 hours to 56 hours).[53]

Caffeine is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 oxidase enzyme system (to be specific, the 1A2 isozyme) into three metabolic dimethylxanthines,[54] each of which having its own effects on the body:

- Paraxanthine (84%): Has the effect of increasing lipolysis, leading to elevated glycerol and free fatty acid levels in the blood plasma.

- Theobromine (12%): Dilates blood vessels and increases urine volume. Theobromine is also the principal alkaloid in the cocoa bean, and therefore chocolate.

- Theophylline (4%): Relaxes smooth muscles of the bronchi, and is used to treat asthma. The therapeutic dose of theophylline, however, is many times greater than the levels attained from caffeine metabolism.

Each of these metabolites is further metabolized and then excreted in the urine.

Mechanism of action

Caffeine readily crosses the blood–brain barrier that separates the bloodstream from the interior of the brain. Once in the brain, the principal mode of action is as a nonselective antagonist of adenosine receptors.[55] [56] The caffeine molecule is structurally similar to adenosine, and binds to adenosine receptors on the surface of cells without activating them (an "antagonist" mechanism of action). Therefore, caffeine acts as a competitive inhibitor.

Adenosine is found in every part of the body, because it plays a role in the fundamental ATP-related energy metabolism and is necessary for RNA synthesis, but it has special functions in the brain. There is a great deal of evidence that concentrations of brain adenosine are increased by various types of metabolic stress including anoxia and ischemia. The evidence also indicates that brain adenosine acts to protect the brain by suppressing neural activity and also by increasing blood flow through A2A and A2B receptors located on vascular smooth muscle.[57] By counteracting adenosine, caffeine reduces resting cerebral blood flow between 22% and 30%.[58] Caffeine also has a generally disinhibitory effect on neural activity. It has not been shown, however, how these effects cause increases in arousal and alertness.

Adenosine is released in the brain through a complex mechanism.[57] There is evidence that adenosine functions as a synaptically released neurotransmitter in some cases, but stress-related adenosine increases appear to be produced mainly by extracellular metabolism of ATP. It is not likely that adenosine is the primary neurotransmitter for any group of neurons, but rather that it is released together with other transmitters by a number of neuron types. Unlike most neurotransmitters, adenosine does not seem to be packaged into vesicles that are released in a voltage-controlled manner, but the possibility of such a mechanism has not been completely ruled out.

Several classes of adenosine receptors have been described, with different anatomical distributions. A1 receptors are widely distributed, and act to inhibit calcium uptake. A2A receptors are heavily concentrated in the basal ganglia, an area that plays a critical role in behavior control, but can be found in other parts of the brain as well, in lower densities. There is evidence that A 2A receptors interact with the dopamine system, which is involved in reward and arousal. (A2A receptors can also be found on arterial walls and blood cell membranes.)

Beyond its general neuroprotective effects, there are reasons to believe that adenosine may be more specifically involved in control of the sleep-wake cycle. Robert McCarley and his colleagues have argued that accumulation of adenosine may be a primary cause of the sensation of sleepiness that follows prolonged mental activity, and that the effects may be mediated both by inhibition of wake-promoting neurons via A1 receptors, and activation of sleep-promoting neurons via indirect effects on A2A receptors.[59] More recent studies have provided additional evidence for the importance of A2A, but not A1, receptors.[60]

Some of the secondary effects of caffeine are probably caused by actions unrelated to adenosine. Like other methylated xanthines, caffeine is both a

- competitive nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor [61] which raises intracellular cAMP, activates PKA, inhibits TNF-alpha [62] [63] and leukotriene [64] synthesis, and reduces inflammation and innate immunity [64]. Caffeine is also added to agar, which partially inhibits the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by inhibiting cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase.[65]

- nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist [56] (see above).

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors inhibit cAMP-phosphodiesterase (cAMP-PDE) enzymes, which convert cyclic AMP (cAMP) in cells to its noncyclic form, thus allowing cAMP to build up in cells. Cyclic AMP participates in activation of protein kinase A (PKA) to begin the phosphorylation of specific enzymes used in glucose synthesis. By blocking its removal, caffeine intensifies and prolongs the effects of epinephrine and epinephrine-like drugs such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, and methylphenidate. Increased concentrations of cAMP in parietal cells causes an increased activation of protein kinase A (PKA), which in turn increases activation of H+/K+ ATPase, resulting finally in increased gastric acid secretion by the cell. Cyclic AMP also increases the activity of the funny current, which directly increases heart rate. Caffeine is also a structural analogue of strychnine and, like it (though much less potent), a competitive antagonist at ionotropic glycine receptors.[66]

Metabolites of caffeine also contribute to caffeine's effects. Paraxanthine is responsible for an increase in the lipolysis process, which releases glycerol and fatty acids into the blood to be used as a source of fuel by the muscles. Theobromine is a vasodilator that increases the amount of oxygen and nutrient flow to the brain and muscles. Theophylline acts as a smooth muscle relaxant that chiefly affects bronchioles and acts as a chronotrope and inotrope that increases heart rate and efficiency.[67]

Effects when taken in moderation

The precise amount of caffeine necessary to produce effects varies from person to person depending on body size and degree of tolerance to caffeine. It takes less than an hour for caffeine to begin affecting the body and a mild dose wears off in three to four hours.[28] Consumption of caffeine does not eliminate the need for sleep, it only temporarily reduces the sensation of being tired throughout the day. In general, 25 to 50 milligrams of caffeine is sufficient for most people to report increased alertness and arousal as well as subjectively lower levels of fatigue.[69]

With these effects, caffeine is an ergogenic, increasing a person's capability for mental or physical labor. A study conducted in 1979 showed a 7% increase in distance cycled over a period of two hours in subjects that consumed caffeine compared to control subjects.[70] Other studies attained much more dramatic results; one particular study of trained runners showed a 44% increase in "race-pace" endurance, as well as a 51% increase in cycling endurance, after a dosage of 9 milligrams of caffeine per kilogram of body weight.[71] Additional studies have reported similar effects. Another study found 5.5 milligrams of caffeine per kilogram of body mass resulted in subjects cycling 29% longer during high-intensity circuits.[72]

Caffeine citrate has proven to be of short- and long-term benefit in treating the breathing disorders of apnea of prematurity and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants.[68] The only short-term risk associated with caffeine citrate treatment is a temporary reduction in weight gain during the therapy,[73] and longer term studies (18 to 21 months) have shown lasting benefits of treatment of premature infants with caffeine.[74][75]

Caffeine relaxes the internal anal sphincter muscles and thus should be avoided by those with fecal incontinence.[76]

While relatively safe for humans, caffeine is considerably more toxic to some other animals such as dogs, horses, and parrots due to a much poorer ability to metabolize this compound. Caffeine has also a pronounced effect on mollusks and various insects as well as spiders.[77]

Tolerance and withdrawal

Because caffeine is primarily an antagonist of the central nervous system's receptors for the neurotransmitter adenosine, the bodies of individuals that regularly consume caffeine adapt to the continuous presence of the drug by substantially increasing the number of adenosine receptors in the central nervous system. This increase in the number of the adenosine receptors makes the body much more sensitive to adenosine, with two primary consequences.[78] First, the stimulatory effects of caffeine are substantially reduced, a phenomenon known as a tolerance adaptation. Second, because these adaptive responses to caffeine make individuals much more sensitive to adenosine, a reduction in caffeine intake will effectively increase the normal physiological effects of adenosine, resulting in unwelcome withdrawal symptoms in tolerant users.[78]

Other research questions the idea that up-regulation of adenosine receptors is responsible for tolerance to the locomotor stimulant effects of caffeine, noting, among other things, that this tolerance is insurmountable by higher doses of caffeine (it should be surmountable if tolerance were due to an increase in receptors), and that the increase in adenosine receptor number is modest and does not explain the large tolerance that develops to caffeine.[79]

Caffeine tolerance develops very quickly, especially among heavy coffee and energy drink consumers. Complete tolerance to sleep disruption effects of caffeine develops after consuming 400 mg of caffeine 3 times a day for 7 days. Complete tolerance to subjective effects of caffeine was observed to develop after consuming 300 mg 3 times per day for 18 days, and possibly even earlier.[80] In another experiment, complete tolerance of caffeine was observed when the subject consumed 750–1200 mg per day while incomplete tolerance to caffeine has been observed in those that consume more average doses of caffeine.[81]

Because adenosine, in part, serves to regulate blood pressure by causing vasodilation, the increased effects of adenosine due to caffeine withdrawal cause the blood vessels of the head to dilate, leading to an excess of blood in the head and causing a headache and nausea. Reduced catecholamine activity may cause feelings of fatigue and drowsiness. A reduction in serotonin levels when caffeine use is stopped can cause anxiety, irritability, inability to concentrate, and diminished motivation to initiate or to complete daily tasks; in extreme cases it may cause mild depression. Together, these effects have come to be known as a "crash".[82]

Withdrawal symptoms — possibly including headache, irritability, an inability to concentrate, drowsiness, insomnia and pain in the stomach, upper body, and joints[83] — may appear within 12 to 24 hours after discontinuation of caffeine intake, peak at roughly 48 hours, and usually last from one to five days, representing the time required for the number of adenosine receptors in the brain to revert to "normal" levels, uninfluenced by caffeine consumption. Analgesics, such as aspirin, can relieve the pain symptoms, as can a small dose of caffeine.[84] Most effective is a combination of both an analgesic and a small amount of caffeine.

This is not the only case in which caffeine increases the effectiveness of a drug. Caffeine makes pain relievers 40% more effective in relieving headaches and helps the body absorb headache medications more quickly, bringing faster relief.[85] For this reason, many over-the-counter headache drugs include caffeine in their formula. It is also used with ergotamine in the treatment of migraine and cluster headaches as well as to overcome the drowsiness caused by antihistamines.

Overuse

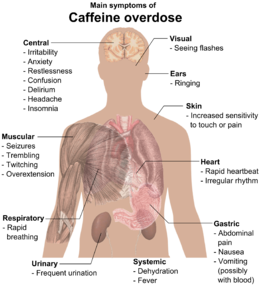

In large amounts, and especially over extended periods of time, caffeine can lead to a condition known as caffeinism.[86][87] Caffeinism usually combines caffeine dependency with a wide range of unpleasant physical and mental conditions including nervousness, irritability, anxiety, tremulousness, muscle twitching (hyperreflexia), insomnia, headaches, respiratory alkalosis, and heart palpitations.[88][89] Furthermore, because caffeine increases the production of stomach acid, high usage over time can lead to peptic ulcers, erosive esophagitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.[90]

There are four caffeine-induced psychiatric disorders recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: caffeine intoxication, caffeine-induced anxiety disorder, caffeine-induced sleep disorder, and caffeine-related disorder not otherwise specified (NOS).

Caffeine intoxication

An acute overdose of caffeine, usually in excess of about 300 milligrams, dependent on body weight and level of caffeine tolerance, can result in a state of central nervous system over-stimulation called caffeine intoxication (DSM-IV 305.90),[91] or colloquially the "caffeine jitters". The symptoms of caffeine intoxication are not unlike overdoses of other stimulants. It may include restlessness, nervousness, excitement, insomnia, flushing of the face, increased urination, gastrointestinal disturbance, muscle twitching, a rambling flow of thought and speech, irritability, irregular or rapid heart beat, and psychomotor agitation.[89] In cases of much larger overdoses, mania, depression, lapses in judgment, disorientation, disinhibition, delusions, hallucinations, and psychosis may occur, and rhabdomyolysis (breakdown of skeletal muscle tissue) can be provoked.[92][93]

In cases of extreme overdose, death can result. The median lethal dose (LD50) given orally, is 192 milligrams per kilogram in rats.[2] The LD50 of caffeine in humans is dependent on weight and individual sensitivity and estimated to be about 150 to 200 milligrams per kilogram of body mass, roughly 80 to 100 cups of coffee for an average adult taken within a limited time frame that is dependent on half-life. Though achieving lethal dose with caffeine would be exceptionally difficult with regular coffee, there have been reported deaths from overdosing on caffeine pills, with serious symptoms of overdose requiring hospitalization occurring from as little as 2 grams of caffeine. An exception to this would be taking a drug such as fluvoxamine, which blocks the liver enzyme responsible for the metabolism of caffeine, thus increasing the central effects and blood concentrations of caffeine dramatically at 5-fold. It is not contraindicated, but highly advisable to minimize the intake of caffeinated beverages, as drinking one cup of coffee will have the same effect as drinking five under normal conditions.[94][95][96][97] Death typically occurs due to ventricular fibrillation brought about by effects of caffeine on the cardiovascular system.

Treatment of severe caffeine intoxication is generally supportive, providing treatment of the immediate symptoms, but if the patient has very high serum levels of caffeine then peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, or hemofiltration may be required.

Anxiety and sleep disorders

Two infrequently diagnosed caffeine-induced disorders that are recognized by the American Psychological Association (APA) are caffeine-induced sleep disorder and caffeine-induced anxiety disorder, which can result from long-term excessive caffeine intake.

In the case of caffeine-induced sleep disorder, an individual regularly ingests high doses of caffeine sufficient to induce a significant disturbance in his or her sleep, sufficiently severe to warrant clinical attention.[91]

In some individuals, the large amounts of caffeine can induce anxiety severe enough to necessitate clinical attention. This caffeine-induced anxiety disorder can take many forms, from generalized anxiety to panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, or even phobic symptoms.[91] Because this condition can mimic organic mental disorders, such as panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, or even schizophrenia, a number of medical professionals believe caffeine-intoxicated people are routinely misdiagnosed and unnecessarily medicated when the treatment for caffeine-induced psychosis would simply be to stop further caffeine intake.[98] A study in the British Journal of Addiction concluded that caffeinism, although infrequently diagnosed, may afflict as many as one person in ten of the population.[87] Co administration of theanine was shown to greatly reduce this caffeine-induced anxiety.[99]

Effects on memory and learning

An array of studies found that caffeine could have nootropic effects, inducing certain changes in memory and learning.

Researchers have found that long-term consumption of low dose caffeine slowed hippocampus-dependent learning and impaired long-term memory in mice. Caffeine consumption for 4 weeks also significantly reduced hippocampal neurogenesis compared to controls during the experiment. The conclusion was that long-term consumption of caffeine could inhibit hippocampus-dependent learning and memory partially through inhibition of hippocampal neurogenesis.[100].

In another study, caffeine was added to rat neurons in vitro. The dendritic spines (a part of the brain cell used in forming connections between neurons) taken from the hippocampus (a part of the brain associated with memory) grew by 33% and new spines formed. After an hour or two, however, these cells returned to their original shape.[101]

Another study showed that human subjects — after receiving 100 milligrams of caffeine — had increased activity in brain regions located in the frontal lobe, where a part of the working memory network is located, and the anterior cingulate cortex, a part of the brain that controls attention. The caffeinated subjects also performed better on the memory tasks.[102]

However, a different study showed that caffeine could impair short-term memory and increase the likelihood of the tip of the tongue phenomenon. The study allowed the researchers to suggest that caffeine could aid short-term memory when the information to be recalled is related to the current train of thought, but also to hypothesize that caffeine hinders short-term memory when the train of thought is unrelated.[103] In essence, caffeine consumption increases mental performance related to focused thought while it may decrease broad-range thinking abilities.

Effects on the heart

Caffeine binds to receptors on the surface of heart muscle cells, which leads to an increase in the level of cAMP inside the cells (by blocking the enzyme that degrades cAMP), mimicking the effects of epinephrine (which binds to receptors on the cell that activate cAMP production). cAMP acts as a "second messenger," and activates a large number of protein kinase A (PKA; cAMP-dependent protein kinase). This has the overall effect of increasing the rate of glycolysis and increases the amount of ATP available for muscle contraction and relaxation. According to one study, caffeine in the form of coffee, significantly reduces the risk of heart disease in epidemiological studies. However, the protective effect was found only in participants who were not severely hypertensive (i.e., patients that are not suffering from a very high blood pressure). Furthermore, no significant protective effect was found in participants aged less than 65 years or in cerebrovascular disease mortality for those aged equal or more than 65 years.[104]

Effects on children

It is a common myth that excessive intake of caffeine results in stunted growth within children, particularly younger children and teenagers.[105] - recently, scientific studies[which?] have disproved the notion. Children are found to experience the same effects from caffeine as adults.

However, subsidiary beverages that contain caffeine, such as energy drinks, most of which contain high amounts of caffeine, have been banned in many schools throughout the world, due to other adverse effects having been observed in prolonged consumption of caffeine.[106] Furthermore, in one study, caffeinated Cola has been linked to hyperactivity in children.[107]

Caffeine intake during pregnancy

Despite its widespread use and the conventional view that it is a safe substance, a 2008 study suggested that pregnant women who consume 200 milligrams or more of caffeine per day have about twice the miscarriage risk as women who consume none. However, another 2008 study found no correlation between miscarriage and caffeine consumption.[108] The UK Food Standards Agency has recommended that pregnant women should limit their caffeine intake to less than 200 mg of caffeine a day—the equivalent of two cups of instant coffee or a half to two cups of fresh coffee.[109][110] The FSA noted that the design of the studies made it impossible to be certain that the differences were due to caffeine per se, instead of other lifestyle differences possibly associated with high levels of caffeine consumption, but judged the advice to be prudent.

Dr De-Kun Li of Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, writing in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, concluded that an intake of 200 milligrams or more per day, representing two or more cups, "significantly increases the risk of miscarriage".[111] However, Dr. David A. Savitz, a professor in community and preventive medicine at New York's Mount Sinai School of Medicine and lead author of the other new study on the subject published in the January issue of Epidemiology, found no link between miscarriage and caffeine consumption.[108]

Genetics and caffeine metabolism

A 2006 study by Dr. Ahmed El-Sohemy at the University of Toronto discovered a link between a gene affecting caffeine metabolism and the effects of coffee on health.[112] Some people metabolize caffeine more slowly than the general population due to variations in a specific cytochrome P450 gene[113], and there is evidence people with this gene may be at a higher risk of myocardial infarction when consuming large amounts of coffee. For rapid metabolizers, however, coffee seemed to have a preventative effect. Slow and fast metabolizers are comparably common in the general population, and this has been blamed for the wide variation in studies of the health effects of caffeine.

Intraocular Pressure and caffeine

Recent data has suggested that caffeine consumption can raise intraocular pressure.[114] This may be a significant consideration for those with open angle glaucoma.[115]

Decaffeination

Extraction of caffeine from coffee, to produce decaffeinated coffee and caffeine, is an important industrial process and can be performed using a number of different solvents. Benzene, chloroform, trichloroethylene and dichloromethane have all been used over the years but for reasons of safety, environmental impact, cost and flavor, they have been superseded by the following main methods:

Water extraction

Coffee beans are soaked in water. The water, which contains many other compounds in addition to caffeine and contributes to the flavor of coffee, is then passed through activated charcoal, which removes the caffeine. The water can then be put back with the beans and evaporated dry, leaving decaffeinated coffee with its original flavor.[116] Coffee manufacturers recover the caffeine and resell it for use in soft drinks and over-the-counter caffeine tablets.

Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction

Supercritical carbon dioxide is an excellent nonpolar solvent for caffeine, and is safer than the organic solvents that are otherwise used. The extraction process is simple: CO2 is forced through the green coffee beans at temperatures above 31.1 °C and pressures above 73 atm. Under these conditions, CO2 is in a "supercritical" state: It has gaslike properties that allow it to penetrate deep into the beans but also liquid-like properties that dissolve 97–99% of the caffeine. The caffeine-laden CO2 is then sprayed with high pressure water to remove the caffeine. The caffeine can then be isolated by charcoal adsorption (as above) or by distillation, recrystallization, or reverse osmosis.[116]

Extraction by organic solvents

Organic solvents such as ethyl acetate present much less health and environmental hazard than previously used chlorinated and aromatic solvents. Another method is to use triglyceride oils obtained from spent coffee grounds.

Religion

Some Latter-day Saints (Mormons), Seventh-day Adventists, Church of God (Restoration) adherents, and Christian Scientists[117] do not consume caffeine. A few followers from these religions believe that one is not supposed to consume a non-medical, psychoactive substance, or believe that one is not supposed to consume a substance that is addictive.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has said the following with regard to caffeinated beverages: “With reference to cola drinks, the Church has never officially taken a position on this matter, but the leaders of the Church have advised, and we do now specifically advise, against the use of any drink containing harmful drugs under circumstances that would result in acquiring the habit. Any beverage that contains ingredients harmful to the body should be avoided.” (Priesthood Bulletin, Feb. 1972, p. 4.) See also Word of Wisdom.

Gaudiya Vaishnava Hindus generally also abstain from caffeine, as it is alleged to cloud the mind and over-stimulate the senses. To be initiated under a guru, one must have had no caffeine (along with alcohol, nicotine and other drugs) for at least a year.

In Islam the main rule on caffeine is that it is permissible, however it is worth noting that it should not be over used and cause severe harm to one's body. With regard to the caffeine in coffee, Imam Shihab al-Din said: 'it is halal (lawful) to drink, because all things are halal (lawful) except that which God has made haraam (unlawful)'.[118]

See also

References

- ^ This is the pKa for protonated caffeine, given as a range of values included in Harry G. Brittain, Richard J. Prankerd (2007). Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology, volume 33: Critical Compilation of Pka Values for Pharmaceutical Substances. Academic Press. ISBN 012260833X.

- ^ a b Peters, Josef M. (1967). "Factors Affecting Caffeine Toxicity: A Review of the Literature". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and the Journal of New Drugs (7): 131–141.

- ^ "caffeine — Definitions from Dictionary.com". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Lovett, Richard (24 September 2005). "Coffee: The demon drink?" (fee required). New Scientist (2518). Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "21 CFR 182.1180". U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. U.S. Office of the Federal Register. 2003-04-01. p. 462. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ a b Griffin, R. J.; Griffin, J. (2003). "Caffeine ingestion and fluid balance: a review". Journal of human nutrition and dietetics. 16 (6): 411. doi:10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00477.x.

- ^ "Really? The Claim: Caffeine Causes Dehydration". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Armstrong LE, Casa DJ, Maresh CM, Ganio MS (2007). "Caffeine, fluid-electrolyte balance, temperature regulation, and exercise-heat tolerance". Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 35 (3): 135–140. doi:10.1097/jes.0b013e3180a02cc1. PMID 17620932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (Review article) - ^ Armstrong LE, Pumerantz AC, Roti MW, Judelson DA, Watson G, Dias JC, Sokmen B, Casa DJ, Maresh CM, Lieberman H, Kellogg M. (2005). "Fluid, electrolyte, and renal indices of hydration during 11 days of controlled caffeine consumption". Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 15 (3): 252–265. PMID 16131696.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (Placebo controlled randomized clinical trial) - ^ Frischknecht, P. M.; Ulmer-Dufek, Jindra; Baumann, Thomas W. (1986). "Purine formation in buds and developing leaflets of Coffea arabica: expression of an optimal defence strategy?". Phytochemistry. 25 (3). Journal of the Phytochemical Society of Europe and the Phytochemical Society of North America.: 613–6. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(86)88009-8.

- ^ Nathanson, J. A. (1984). "Caffeine and related methylxanthines: possible naturally occurring pesticides". Science. 226 (4671): 184–7. doi:10.1126/science.6207592. PMID 6207592.

- ^ Baumann, T. W. (1984). "Metabolism and excretion of caffeine during germination of Coffea arabica L". Plant and Cell Physiology. 25 (8): 1431–6.

- ^ Matissek, R (1997). "Evaluation of xanthine derivatives in chocolate: nutritional and chemical aspects". European Food Research and Technology. 205 (3): 175–84.

- ^ a b "Does Yerba Maté Contain Caffeine or Mateine?". The Vaults of Erowid. 2003. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "PubChem: mateina". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2009-08-03.. Generally translated as mateine in articles written in English

- ^ "PubChem: guaranine". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ^ Balentine D. A., Harbowy M. E. and Graham H. N. (1998). G Spiller (ed.). Tea: the Plant and its Manufacture; Chemistry and Consumption of the Beverage.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Caffeine". International Coffee Organization. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ "Coffee and Caffeine FAQ: Does dark roast coffee have less caffeine than light roast?". Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ^ "All About Coffee: Caffeine Level". Jeremiah’s Pick Coffee Co. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Caffeine in tea vs. steeping time". 1996. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Caffeine Content of Food and Drugs". Nutrition Action Health Newsletter. Center for Science in the Public Interest. 1996. Archived from the original on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)} - ^ "Caffeine Content of Beverages, Foods, & Medications". The Vaults of Erowid. July 7, 2006. Retrieved 2009-08-03.}

- ^ Haskell, C. F.; Kennedy, DO; Wesnes, KA; Milne, AL; Scholey, AB (2007). "A double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-dose evaluation of the acute behavioural effects of guarana in humans". J Psychopharmacol. 21 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1177/0269881106063815. PMID 16533867.

- ^ Smit, H. J.; Gaffan, EA; Rogers, PJ (2004). "Methylxanthines are the psycho-pharmacologically active constituents of chocolate". Psychopharmacology. 176 (3–4): 412–9. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1898-3. PMID 15549276.

- ^ "Caffeine Accessories". ThinkGeek, Inc. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ "Does caffeinated soap really work?". Erowid. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ a b c Bolton, Ph.D., Sanford (1981). "Caffeine: Psychological Effects, Use and Abuse". Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 10 (3): 202–211.

- ^ Bennett Alan Weinberg, Bonnie K. Bealer (2001). The world of caffeine. Routledge. p. 195. ISBN 0415927226.

- ^ a b Funk GD. (2009). Losing sleep over the caffeination of prematurity. J Physiol. 587(Pt 22):5299-300. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.182303 PMID 19915211

- ^ Escohotado, Antonio (1999). A Brief History of Drugs: From the Stone Age to the Stoned Age. Park Street Press. ISBN 0-89281-826-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Všechny čaje Číny (in Czech). Michal Synek (translator). Prague: DharmaGaia Praha. 1998. pp. 19–20. ISBN 80-85905-48-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) Translation of Kit Chow, Ione Kramer (1990). All the Tea in China. San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals Inc. ISBN 0-8351-2194-1. - ^ Jana Arcimovičová, Pavel Valíček (1998). Vůně čaje (in Czech). Benešov: Start. p. 9. ISBN 80-902005-9-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ John C. Evans (1992). Tea in China: The History of China's National Drink. Greenwood Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-313-28049-5.

- ^ Yu, Lu (1995). The Classic of Tea: Origins & Rituals. Ecco Pr; Reissue edition. ISBN 0-88001-416-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ukers, W.H. (1922). All About Coffee. New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company. p. 40.

- ^ "Coffee". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911.

- ^ Benjamin, LT Jr; Rogers, AM; Rosenbaum, A (1991). "Coca-Cola, caffeine, and mental deficiency: Harry Hollingworth and the Chattanooga trial of 1911". J Hist Behav Sci. 27 (1): 42–55. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(199101)27:1<42::AID-JHBS2300270105>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 2010614.

- ^ a b Weinberg, BA (2001). The World of Caffeine. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92722-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nobel Prize Presentation Speech by Professor Hj. Théel, President of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences". December 10, 1902. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Simon Tilling. "Crystalline Caffeine". Bristol University. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Ted Wilson, Norman J. Temple (2004). Beverages in Nutrition and Health. Humana Press. p. 172. ISBN 1588291731.

- ^ "What's your poison: caffeine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 1997. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Nehlig, A; Daval, JL; Debry, G (1992). "Caffeine and the central nervous system: Mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic, and psychostimulant effects". Brain Res Rev. 17 (2): 139–70. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(92)90012-B. PMID 1356551.

- ^ Liguori A, Hughes JR, Grass JA (1997). "Absorption and subjective effects of caffeine from coffee, cola and capsules". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 58 (3): 721–6. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(97)00003-8. PMID 9329065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Newton, R; Broughton, LJ; Lind, MJ; Morrison, PJ; Rogers, HJ; Bradbrook, ID (1981). "Plasma and salivary pharmacokinetics of caffeine in man". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 21 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1007/BF00609587. PMID 7333346.

- ^ Graham JR (1954). "Rectal use of ergotamine tartrate and caffeine for the relief of migraine; though in some migraine sufferers, caffeine itself is a trigger for attacks". N. Engl. J. Med. 250 (22): 936–8. PMID 13165929.

- ^ Brødbaek HB, Damkier P (2007). "[The treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum with chlorobutanol-caffeine rectal suppositories in Denmark: practice and evidence]". Ugeskr. Laeg. (in Danish). 169 (22): 2122–3. PMID 17553397.

- ^ Meyer, FP; Canzler, E; Giers, H; Walther, H (1991). "Time course of inhibition of caffeine elimination in response to the oral depot contraceptive agent Deposiston. Hormonal contraceptives and caffeine elimination". Zentralbl Gynakol. 113 (6): 297–302. PMID 2058339.

- ^ Ortweiler, W; Simon, HU; Splinter, FK; Peiker, G; Siegert, C; Traeger, A (1985). "Determination of caffeine and metamizole elimination in pregnancy and after delivery as an in vivo method for characterization of various cytochrome p-450 dependent biotransformation reactions". Biomed Biochim Acta. 44 (7–8): 1189–99. PMID 4084271.

- ^ Bolton, Ph.D., Sanford (1981). "Caffeine: Psychological Effects, Use and Abuse". Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 10 (3): 202–11.

- ^ Springhouse (January 1, 2005). Physician's Drug Handbook; 11th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 1-58255-396-3.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Drug Interaction: Caffeine Oral and Fluvoxamine Oral Medscape Multi-Drug Interaction Checker

- ^ "Caffeine". The Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Fisone, G; Borgkvist, A; Usiello, A (2004). "Caffeine as a psychomotor stimulant: mechanism of action". Cell Mol Life Sci. 61 (7–8): 857–72. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3269-3. PMID 15095008.

- ^ a b Daly JW, Jacobson KA, Ukena D. (1987). "Adenosine receptors: development of selective agonists and antagonists". Prog Clin Biol Res. 230 (1): :41–63. PMID 3588607.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Latini, S; Pedata, F (2001). "Adenosine in the central nervous system: release mechanisms and extracellular concentrations". J Neurochem. 79 (3): 463–84. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00607.x. PMID 11701750.

- ^ Addicott MA, Yang LL, Peiffer AM, Burnett LR, Burdette JH, Chen MY, Hayasaka S, Kraft RA, Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ (2009). "The effect of daily caffeine use on cerebral blood flow: How much caffeine can we tolerate?". Hum Brain Mapp. 30 (10): 3102–14. doi:10.1002/hbm.20732. PMC 2748160. PMID 19219847.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Basheer, R; Strecker, RE; Thakkar, MM; McCarley, RW (2004). "Adenosine and sleep-wake regulation". Prog Neurobiol. 73 (6): 379–96. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.004. PMID 15313333.

- ^ Huang, ZL; Qu, WM; Eguchi, N; Chen, JF; Schwarzschild, MA; Fredholm, BB; Urade, Y; Hayaishi, O (2005). "Adenosine A2A, but not A1, receptors mediate the arousal effect of caffeine" (PDF). Nature Neurosci. 8 (7): 858–9. doi:10.1038/nn1491. PMID 15965471. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ^ Essayan DM. (2001). "Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 108 (5): 671–80. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.119555. PMID 11692087.

- ^ Deree J, Martins JO, Melbostad H, Loomis WH, Coimbra R. (2008). "Insights into the regulation of TNF-alpha production in human mononuclear cells: the effects of non-specific phosphodiesterase inhibition". Clinics (Sao Paulo). 63 (3): 321–8. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322008000300006. PMC 2664230. PMID 18568240.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marques LJ, Zheng L, Poulakis N, Guzman J, Costabel U (1999). "Pentoxifylline inhibits TNF-alpha production from human alveolar macrophages". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159 (2): 508–11. PMID 9927365.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Peters-Golden M, Canetti C, Mancuso P, Coffey MJ. (2005). "Leukotrienes: underappreciated mediators of innate immune responses". J Immunol. 174 (2): 589–94. PMID 15634873.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caesar, Robert, Jonas Warringer, and Anders Blomberg. "Physiological Importance and Identification of Novel Targets for the N-Terminal Acetyltransferase NatB." American society for Microbiology. 16 Dec. 2005. Web. 12 Feb. 2010. <http://ec.asm.org/cgi/content/full/5/2/368>.

- ^ Duan L, Yang J, Slaughter MM. (2009). Caffeine inhibition of ionotropic glycine receptors. J Physiol. 587(Pt 16):4063-75. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174797 PMID 19564396

- ^ Dews, P.B. (1984). Caffeine: Perspectives from Recent Research. Berlin: Springer-Valerag. ISBN 978-0387135328.

- ^ a b c "Caffeine (Systemic)". MedlinePlus. 2000-05-25. Archived from the original on 2007-02-23. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Rasmussen, JL; Gallino, M (1997). "Effects of caffeine on subjective reports of fatigue and arousal during mentally demanding activities". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 37 (1): 61–90. PMID 7794434.

- ^ Ivy, JL; Costill, DL; Fink, WJ; Lower, RW (1979). "Influence of caffeine and carbohydrate feedings on endurance performance". Med Sci Sports. 11 (1): 6–11. PMID 481158.

- ^ Graham, TE; Spriet, LL (1991). "Performance and metabolic responses to a high caffeine dose during prolonged exercise". J Appl Physiol. 71 (6): 2292–8. PMID 1778925.

- ^ Trice, I; Haymes, EM (1995). "Effects of caffeine ingestion on exercise-induced changes during high-intensity, intermittent exercise". Int J Sport Nutr. 5 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. PMID 7749424.

- ^ Schmidt, B; Roberts, RS; Davis, P; Doyle, LW; Barrington, KJ; Ohlsson, A; Solimano, A; Tin, W; Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity Trial Group (2006). "Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". N Engl J Med. 354 (20): 2112–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054065. PMID 16707748.

- ^ Schmidt, B; Roberts, RS; Davis, P; Doyle, LW; Barrington, KJ; Ohlsson, A; Solimano, A; Tin, W; Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity Trial Group (2007). "Long-Term Effects of Caffeine Therapy for Apnea of Prematurity". N Engl J Med. 357 (19): 1893–1902. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073679. PMID 17989382.

- ^ Schmidt, B (2005). "Methylxanthine Therapy for Apnea of Prematurity: Evaluation of Treatment Benefits and Risks at Age 5 Years in the International Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) Trial". Neonatology. 88 (3): 208–213. doi:10.1159/000087584.

- ^ "Fecal incontinence". NIH. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Noever, R., J. Cronise, and R. A. Relwani. 1995. Using spider-web patterns to determine toxicity. NASA Tech Briefs 19(4):82. Published in New Scientist magazine, 29 April 1995

- ^ a b Green, RM; Stiles, GL (1986). "Chronic caffeine ingestion sensitizes the A1 adenosine receptor-adenylate cyclase system in rat cerebral cortex". J Clin Invest. 77 (1): 222–227. doi:10.1172/JCI112280. PMC 423330. PMID 3003150.

- ^ Holtzman SG, Mante S, Minneman KP (1991). "Role of adenosine receptors in caffeine tolerance". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 256 (1): 62–8. PMID 1846425.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Caffeine — A Drug of Abuse?". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Information About Caffeine Dependence". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Health risks of Stimulants, healthandgoodness.com". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Juliano, L M; Griffiths, RR (2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology. 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. PMID 15448977.

- ^ Sawynok, J (1995). "Pharmacological rationale for the clinical use of caffeine". Drugs. 49 (1): 37–50. doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. PMID 7705215.

- ^ "Headache Triggers: Caffeine". WebMD. 2004. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mackay, DC; Rollins, JW (1989). "Caffeine and caffeinism". Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service. 75 (2): 65–7. PMID 2607498.

- ^ a b James, JE; Stirling, KP (1983). "Caffeine: A summary of some of the known and suspected deleterious effects of habitual use". British Journal of Addiction. 78 (3): 251–8. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1983.tb02509.x. PMID 6354232.

- ^ Leson CL, McGuigan MA, Bryson SM (1988). "Caffeine overdose in an adolescent male". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 26 (5–6): 407–15. PMID 3193494.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Caffeine-related disorders". Encyclopedia of Mental Disorders. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)". Cedars-Sinai. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ a b c American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 0-89042-062-9.

- ^ "Caffeine overdose". MedlinePlus. 2006-04-04. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Kamijo, Y; Soma, K; Asari, Y; Ohwada, T (1999). "Severe rhabdomyolysis following massive ingestion of oolong tea: caffeine intoxication with coexisting hyponatremia". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 41 (6): 381–3. doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. PMID 10592946.

- ^ Kerrigan, S; Lindsey, T (2005). "Fatal caffeine overdose: two case reports" (reprint). Forensic Sci Int. 153 (1): 67–69. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.04.016. PMID 15935584.

- ^ Holmgren, P; Nordén-Pettersson, L; Ahlner, J (2004). "Caffeine fatalities — four case reports" (reprint). Forensic Sci Int. 139 (1): 71–73. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.09.019. PMID 14687776.

- ^ Walsh, I; Wasserman, GS; Mestad, P; Lanman, RC (1987). "Near-fatal caffeine intoxication treated with peritoneal dialysis". Pediatr Emerg Care. 3 (4): 244–9. doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. PMID 3324064.

- ^ Mrvos, RM; Reilly, PE; Dean, BS; Krenzelok, EP (1989). "Massive caffeine ingestion resulting in death". Vet Hum Toxicol. 31 (6): 571–2. doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. PMID 2617841.

- ^ Shannon, MW (1998). Clinical Management of Poisoning and Drug Overdose, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-6409-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Haskell CF, Kennedy DO, Milne AL, Wesnes KA, Scholey AB (2008). "The effects of l-theanine, caffeine and their combination on cognition and mood". Biol Psychol. 77 (2): 113–22. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.09.008. PMID 18006208.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Han ME, Park KH, Baek SY (2007). "Inhibitory effects of caffeine on hippocampal neurogenesis and function". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 356 (4): 976–80. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.086. PMID 17400186.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Caffeine clue to better memory". BBC News. 1999-10-12. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Caffeine Boosts Short-Time Memory". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Lesk VE, Womble SP. (2004). "Caffeine, priming, and tip of the tongue: evidence for plasticity in the phonological system". Behavioral Neuroscience. 118 (2): 453–61. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.118.3.453. PMID 15174922.

- ^ Greenberg, J.A.; Dunbar, CC; Schnoll, R; Kokolis, R; Kokolis, S; Kassotis, J (2007). "Caffeinated beverage intake and the risk of heart disease mortality in the elderly: a prospective analysis". Am J Clin Nutr. 85 (2): 392–8. PMID 17284734.

- ^ "Fact or fiction: Common diet myths dispelled". MSNBC. 2006. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Caffeine and Your Child". KidsHealth. 2005. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Caffeinated Cola Makes Kids Hyperactive". WebMD. 2005. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rubin, Rita (2008-01-20). "New studies, different outcomes on caffeine, pregnancy". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Food Standards Agency publishes new caffeine advice for pregnant women". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Danielle Dellorto (January 21, 2008). "Study: Caffeine may boost miscarriage risk". CNN. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Kaiser Permanente Study Shows Newer, Stronger Evidence that Caffeine During Pregnancy Increases Miscarriage Risk". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Michael O'Riordan (March 7, 2006). "Heavy coffee drinkers with slow caffeine metabolism at increased risk of nonfatal MI". theheart.org by WebMD. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ Cornelis MC, El-Sohemy A, Kabagambe EK, Campos H (2006). "Coffee, CYP1A2 genotype, and risk of myocardial infarction". JAMA. 295 (10): 1135–41. doi:10.1001/jama.295.10.1135. PMID 16522833.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Higginbotham EJ, Kilimanjaro HA, Wilensky JT, Batenhorst RL, Hermann D (1989). "The effect of caffeine on intraocular pressure in glaucoma patients". Ophthalmology. 96 (5): 624–6. PMID 2636858.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Avisar R, Avisar E, Weinberger D (2002). "Effect of coffee consumption on intraocular pressure". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (6): 992–5. PMID 12022898.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Senese, Fred (2005-09-20). "How is coffee decaffeinated?". General Chemistry Online. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Voices of Faith: April 12, 2008". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "Drinking drinks with caffeine". Retrieved 2009-08-03.

External links

- How Stuff Works: "How Caffeine Works"

- Erowid Caffeine Vaults

- Highly Caffeinated: The Caffeine Information Archive"

- National Geographic January 2005: Caffeine

- Caffeine Zone: Social and Medical info on caffeine and its effects.

- Naked Scientists Online: Why do plants make caffeine?

- The Physician and Sportsmedicine: Caffeine: A User's Guide

- The Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs, Caffeine-Part 1 Part 2

- Coffee: A Little Really Does Go a Long Way, NPR, September 28, 2006

- Does coffee really give you a buzz? by John Triggs in the Daily Express April 17 2007

- Caffeine: ChemSub Online

- How much caffeine is in your daily habit? (Caffeine content in common foods and drinks) by Mayo Clinic Staff October 2007

- How to determine caffeine in decaffeinated coffee by NIR spectroscopy

News

- Alcohol and Drugs History Society: Caffeine news page

- National Post: Caffeine linked to psychiatric disorders

- Caffeine Withdrawal Recognized as a Disorder

Health

- Is Caffeine a Health Hazard?

- eMedicine Caffeine-Related Psychiatric Disorders

- Protects brain from Alzheimer's?