Edinburgh

Edinburgh

City of Edinburgh | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top-left: View from Calton Hill, Old College, University of Edinburgh, Old Town from Princes Street, Edinburgh Castle, Princes Street from Calton Hill | |

| Nickname(s): "Auld Reekie", "Edina", "Athens of the North" | |

| Motto(s): "Nisi Dominus Frustra" "Except the Lord in vain" associated with Edinburgh since 1647, it is a normal heraldic contraction of a verse from the 127th Psalm, "Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it. Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain" | |

Edinburgh council area, shown within Scotland | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | City of Edinburgh |

| Lieutenancy area | Edinburgh |

| Admin HQ | Edinburgh City Centre |

| Founded | prior to the 7th century |

| Burgh Charter | 1125 |

| City status | 1889 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council area, City |

| • Governing body | The City of Edinburgh Council |

| • Lord Provost | Donald Wilson |

| • MSPs |

|

| • MPs: |

|

| Area | |

| • City & Council area | 102 sq mi (264 km2) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • City & Council area | 495,360[2] |

| • Urban | 848,890[1] |

| • Urban density | 4,776/sq mi (1,844/km2) |

| • Language(s) | Scots English |

| Demonym | Edinburgher |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postcode | |

| Area code | 0131 |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-EDH |

| ONS code | 00QP |

| OS grid reference | NT275735 |

| NUTS 3 | UKM25 |

| Website | www.edinburgh.gov.uk (Official Council site) www.edinburgh-inspiringcapital.com |

Edinburgh (/ˈɛdɪnbʌrə/ ED-in-burr-ə; Dùn Èideann in Scottish Gaelic) is the capital city of Scotland, situated on the southern shore of the Firth of Forth. With a population of 482,640 in 2012,[3] it is the largest settlement in Lothian and lies at the centre of a larger urban zone of approximately 850,000 people.[4] While the town originally formed on the ridge descending from the Castle Rock, the modern city is often said to be built on and around seven hills.

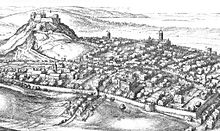

From its prehistoric beginning as a hillfort, following periods of Celtic and Germanic influence, Edinburgh became part of the Kingdom of Scotland during the 10th century. With burgh charters granted by David I and Robert the Bruce, Edinburgh grew through the Middle Ages as Scotland’s biggest merchant town. By the time of the European Renaissance and the reign of James IV it was well established as Scotland's capital. The 16th century Scottish Reformation and 18th century Scottish Enlightenment were formative periods in the history of the city, which played a central role in both. While political power shifted to London following the Treaty of Union in 1707, devolution in 1997 has resulted in the return of a Scottish parliament.

Edinburgh has a high proportion of independent schools, one college and four universities. The University of Edinburgh (which now includes Edinburgh College of Art) is the biggest university in Scotland[5] and ranked 21st in the world.[6] These institutions help provide a highly educated population[7] and drive a dynamic economy.[8] Edinburgh generates a high GVA per capita (the highest of any UK city in 2009),[9] was the UK's most competitive city in 2010[10] and was named European Best Large City of the Future for Foreign Direct Investment by fDi Magazine in 2012/13.[11]

Each August the city hosts the biggest annual international arts festival in the world. This includes the Edinburgh International Festival, Edinburgh Festival Fringe and the Edinburgh International Book Festival. Other festivals are held throughout the year, such as the Science Festival, Film Festival and Jazz and Blues Festival. Other annual events include the Hogmanay street party and Beltane. Edinburgh is the world's first UNESCO City of Literature[12] and the city's Old Town and New Town are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[13]

Edinburgh regularly polls as one of the best places to live, having won more than 12 UK Best City Awards in 8 years to 2013[14] and, attracting over one million overseas visitors a year, is the second most popular tourist destination in the UK[15] and was voted European Destination of the Year at the World Travel Awards 2012.

Etymology

The "Edin" in "Edinburgh", the root of the city's name, is most likely Celtic (P-Celtic, Brythonic) in origin, possibly Cumbric or a variation of it, as would have been spoken by the earliest known people of the area, the Votadini. It appears to derive from the Brythonic place name Eidyn mentioned in some medieval Welsh sources.[16][17][18]

The Edinburgh area was the location of Din Eidyn, a dun or hillfort associated with the kingdom of the Gododdin[19] (the name Gododdin is a later form of Votadini). The change in nomenclature, from Din Eidyn to Edinburgh, reflects changes in the local language from Cumbric to Old English, the Germanic language of the Bernician Angles that permeated the area from the mid-7th century (and the ancestor of modern Scots and English). The Celtic prefix din was dropped and the Old English burh adopted as a suffix.[20]

The first documentary evidence of the city is an early 12th-century royal charter by King David I granting land to the Church of the Holy Rood of Edinburgh c.1124. This charter names the town "Edwinesburg."[21] The city's name is recorded as "Edenesburch" in a charter (in Latin) passed during the 1170s by King William the Lion, confirming the grant of 1124.[22]

History

Early history

Humans settled the Edinburgh area at least as long ago as the Bronze Age, leaving traces of primitive settlements which have been found on Arthur's Seat, Craiglockhart Hill and the Pentland Hills.[23]

By the time the Romans arrived in Lothian towards the end of the 1st century AD, they discovered a Celtic Brythonic tribe whose name they recorded as the Votadini.[24] At some point before the 7th century AD, the Gododdin, who were presumably the descendants of the Votadini, built a hill fort known as Din Eidyn or Etin. Although its exact location has not been identified, it seems more than likely they would have chosen the commanding position of the Castle Rock, or Arthur's Seat or Calton Hill.[25]

In AD 638 the Gododdin stronghold was besieged by forces loyal to King Oswald of Northumbria, and around this time the Edinburgh region passed to the Angles. Anglian influence continued over three centuries until c. AD 950 when, during the reign of Indulf, son of Constantine II, the "burh" (fortress), named by the Pictish Chronicle as "oppidum Eden",[26] fell to the Scots and thenceforth remained under their jurisdiction.[27]

The Royal Burgh was founded by a charter of King David I in the 12th century.[28] By the middle of the 14th century, the French chronicler Froissart described it as the capital of Scotland (c.1365), and James III (1451-88) referred to it as "the principal burgh of our kingdom".[29] Despite the destruction caused by an English assault in 1544, the town slowly recovered[30] and was at the centre of events in the 16th-century Scottish Reformation[31] and 17th-century Wars of the Covenant.[32]

17th century

In 1603, King James VI of Scotland succeeded to the English throne, uniting the crowns of Scotland and England in a personal union known as the Union of the Crowns, though Scotland remained, in all other respects, a separate kingdom.[33]

In 1638, King Charles I's attempt to introduce Anglican church forms in Scotland encountered stiff Presbyterian opposition culminating in the conflicts of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.[34] Subsequent Scottish support for Charles Stuart's restoration to the throne of England, resulted in Edinburgh's occupation by Cromwell's Commonwealth forces in 1650.[35]

In the 17th century, the boundaries of Edinburgh were still defined by the city's defensive town walls. As a result, expansion took the form of the houses increasing in height to accommodate a growing population. Buildings of 11 storeys or more were common,[36] and have been described as forerunners of the modern-day skyscraper.[37] Most of these old structures were later replaced by the predominantly Victorian buildings seen in today's Old Town.

18th century

In 1706 and 1707, the Acts of Union were passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland uniting the two kingdoms into the Kingdom of Great Britain.[38] As a consequence, the Parliament of Scotland merged with the Parliament of England to form the Parliament of Great Britain, which sat at Westminster in London. The Union was opposed by many Scots at the time, resulting in riots in the city.[39]

By the first half of the 18th century, despite rising prosperity evidenced by its growing importance as a banking centre, Edinburgh was being described as one of the most densely populated, overcrowded and unsanitary towns in Europe.[40][41] Visitors were struck by the fact that the various social classes shared the same urban space, even inhabiting the same tenement buildings; although here a form of social segregation did prevail, whereby shopkeepers and tradesmen tended to occupy the cheaper-to-rent cellars and garrets, while the more well-to-do professional classes occupied the more expensive middle storeys.[42]

During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Edinburgh was briefly occupied by the Jacobite "Highland Army" before its march into England.[43] After its ultimate defeat at Culloden, there followed a period of reprisals and pacification, largely directed at the rebellious clans.[44] In Edinburgh, the Town Council, keen to emulate London by initiating city improvements and expansion to the north of the castle,[45] re-affirmed its belief in the Union and loyalty to the Hanoverian monarch George III by its choice of names for the streets of the New Town, for example, Rose Street and Thistle Street, and for the royal family: George Street, Queen Street, Hanover Street, Frederick Street and Princes Street (in honour of George's two sons).[46]

The city was at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment[47] when figures such as David Hume, Adam Smith, James Hutton and Joseph Black could be seen in its streets. Edinburgh became a major intellectual centre, earning it the nickname "Athens of the North" because of its many classical buildings and reputation as a "hotbed of genius" (Smollett) similar to Ancient Athens.[48]

From the 1770s onwards, the professional and business classes gradually deserted the Old Town in favour of the more elegant "one-family" residences of the New Town, a migration that changed the social character of the city. According to the foremost historian of this development, "Unity of social feeling was one of the most valuable heritages of old Edinburgh, and its disappearance was widely and properly lamented."[49]

19th and 20th centuries

Although Edinburgh's traditional industries of printing, papermaking and brewing continued to grow in the 19th century and were joined by new rubber works and engineering works, there was little industrialisation compared with other cities in Britain. By 1821, Edinburgh had been overtaken by Glasgow as Scotland's largest city.[50] The city centre between Princes Street and George Street became a major commercial and shopping district, a development partly stimulated by the arrival of railways in the 1840s. The Old Town became an increasingly dilapidated, overcrowded slum with high mortality rates.[51] Improvements carried out under Lord Provost William Chambers in the 1860s began the transformation of the area into the predominantly Victorian Old Town seen today.[52] More improvements followed in the early 20th century as a result of the work of Patrick Geddes,[53] but relative economic stagnation during the two world wars and beyond saw the Old Town deteriorate further before major slum clearance in the 1960s and 1970s began to reverse the process. University building developments which transformed the George Square and Potterrow areas proved highly controversial.[54]

Since the 1990s a new "financial district", including a new Edinburgh International Conference Centre, has grown mainly on demolished railway property to the west of the castle, stretching into Fountainbridge, a run-down 19th-century industrial suburb which has undergone radical change since the 1980s with the demise of industrial and brewery premises. This ongoing development has enabled Edinburgh to maintain its place as the second largest financial and administrative centre in the United Kingdom after London.[55] Financial services now account for a third of all commercial office space in the city.[56] The development of Edinburgh Park, a new business and technology park covering 38 acres (15 ha), 4 miles west of the city centre, has also contributed to the District Council's strategy for the city's major economic regeneration.[56]

In 1998, the Scotland Act, which came into force the following year, established a devolved Scottish Parliament and Scottish Executive (renamed the Scottish Government since July 2012). Both based in Edinburgh, they are responsible for governing Scotland while reserved matters such as defence, taxation and foreign affairs remain the responsibility of the Parliament of the United Kingdom in London.[57]

Geography

Edinburgh lies on the southern shore of the Firth of Forth in Scotland's Central Belt. The city centre is 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south of the shoreline of Leith and 26 miles (42 km) inland, as the crow flies, from the east coast of Scotland and the North Sea at Dunbar.[58] While the city originated in close proximity to the prominent Castle Rock, the modern city is often said to be built on seven hills, namely Calton Hill, Corstorphine Hill, Craiglockhart Hill, Braid Hill, Blackford Hill, Arthur's Seat and the Castle Rock,[59] giving rise to allusions to the seven hills of Rome.[60] An annual running race takes in these seven hills, starting and finishing at Calton Hill.[61]

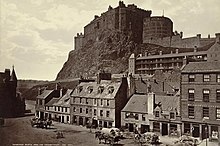

Occupying a narrow gap between the Firth of Forth to the north and the Pentland Hills and their outrunners to the south, the city sprawls over a landscape which is the product of early volcanic activity and later periods of intensive glaciation. [62] Igneous activity between 350 and 400 million years ago, coupled with faulting, led to the dispersion of tough basalt volcanic plugs, which predominate over much of the area.[62] One such example is Castle Rock which forced the advancing icepack to divide, sheltering the softer rock and forming a mile-long tail of material to the east, creating a distinctive crag and tail formation.[62] Glacial erosion on the northern side of the crag gouged a large valley resulting in the now drained Nor Loch. This structure, along with a ravine to the south, formed an ideal natural fortress upon which Edinburgh Castle was built.[62] Similarly, Arthur's Seat is the remains of a volcano system dating from the Carboniferous period, which was eroded by a glacier moving from west to east during the ice age.[62] Erosive action such as plucking and abrasion exposed the rocky crags to the west before leaving a tail of deposited glacial material swept to the east.[63] This process formed the distinctive Salisbury Crags, which formed a series of teschenite cliffs between Arthur's Seat and the location of the early city.[64] The residential areas of Marchmont and Bruntsfield are built along a series of drumlin ridges south of the city centre, which were deposited as the glacier receded.[62]

Other viewpoints in the city such as Calton Hill and Corstorphine Hill are similar products of glacial erosion.[62] The Braid Hills and Blackford Hill are a series of small summits to the south west of the city commanding expansive views over the urban area of Edinburgh and northwards to the Forth.[62]

Edinburgh is drained by the Water of Leith, which has its source at the Colzium Springs in the Pentland Hills and runs for 29 kilometres (18 mi) through the south and west of the city, emptying into the Firth of Forth at Leith.[65] The nearest the river gets to the city centre is at Dean Village on the north-western edge of the New Town, where a deep gorge is spanned by the Dean Bridge, designed by Thomas Telford and built in 1832 for the road to Queensferry.[65] The Water of Leith Walkway is a mixed use trail that follows the river for 19.6 kilometres (12.2 mi) from Balerno to Leith.[66]

Edinburgh is ringed by a green belt, designated in 1957, which stretches from Dalmeny in the west to Prestongrange in the east.[67] With an average width of 3.2 kilometres (2 mi) the principal objective of the green belt was to contain the outward expansion of Edinburgh and to prevent the agglomeration of urban areas.[67] Expansion within the green belt is strictly controlled but developments such as Edinburgh Airport and the Royal Highland Showground at Ingliston lie within the zone.[67] Similarly, outlying suburbs such as Juniper Green and Balerno are situated on green belt land.[67] One feature of the green belt in Edinburgh is the inclusion of parcels of land within the city which are designated green belt, even though they do not adjoin the peripheral ring. Examples of these independent wedges of green belt include Holyrood Park and Corstorphine Hill.[67]

Areas

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 728 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, is divided into distinct areas that retain their original character, where the expanding city has encompassed existing settlements.[68] Many residences are tenements, although the more southern and western parts of the city have traditionally been more affluent and have a greater number of detached and semi-detached villas.[69]

The historic centre of Edinburgh is divided in two by the broad green swath of Princes Street Gardens. To the south the view is dominated by Edinburgh Castle, built high on the castle rock, and the long sweep of the Old Town descending towards Holyrood Palace. To the north lies Princes Street and the New Town.

To the west of the castle lies the financial district, housing insurance and banking buildings together with the Edinburgh International Conference Centre.

The Old Town and New Town districts of Edinburgh were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995 in recognition of the unique character of the Old Town with its medieval street layout and the planned Georgian New Town, including the adjoining Dean Village and Calton Hill areas. There are over 4,500 listed buildings within the city,[13] a higher proportion relative to area than any other city in the United Kingdom. In the 2011 mid-year population estimates, Edinburgh had a total resident population of 495,360.[70]

Old Town

The Old Town has preserved most of its medieval street plan and some Reformation-era buildings. One end is closed off by the castle and the main artery, the mediaeval thoroughfare, known since the 1920s as the Royal Mile,[71] runs downhill to terminate at Holyrood Palace; minor streets (called closes or wynds) lie on either side of the main spine forming a herringbone pattern.[72] The street has several fine public buildings such as the church of St. Giles, the City Chambers and the Law Courts. Other places of historical interest nearby are Greyfriars Kirkyard and the Grassmarket. The street layout is typical of the old quarters of many northern European cities. The castle perches on top of a rocky crag (the remnant of an extinct volcano) and the Royal Mile runs down the crest of a ridge from it.

Due to space restrictions imposed by the narrowness of this landform, the Old Town became home to some of the earliest "high rise" residential buildings. Multi-storey dwellings known as lands were the norm from the 16th century onwards with ten and eleven storeys being typical and one even reaching fourteen or fifteen storeys. [73] Numerous vaults below street level were inhabited to accommodate the influx of immigrants during the Industrial Revolution.

New Town

The New Town was an 18th-century solution to the problem of an increasingly crowded city which had been confined to the ridge sloping down from the castle. In 1766 a competition to design a "New Town" was won by James Craig, a 27-year-old architect.[74] The plan was a rigid, ordered grid, which fitted in well with enlightenment ideas of rationality. The principal street is George Street, running along the natural ridge to the north of the existing "Old Town". To either side of it are two other main streets: Princes Street and Queen Street. Princes Street has become the main shopping street in Edinburgh and now has few of its original Georgian buildings. The three main streets are connected by a series of streets running perpendicular to them. The east and west ends of George Street are terminated by St. Andrew Square and Charlotte Square respectively. The latter, designed by Robert Adam, influenced the architectural style of the New Town into the early 19th century.[75] Bute House, the official residence of the First Minister of Scotland, is on the north side of Charlotte Square.[76]

The hollow between the Old and New Towns was formerly the Nor Loch, which was originally created for the town's defence but came to used for dumping the city's sewage. It was drained by the 1820s as part of the city's northward expansion. Craig's original plan included an ornamental canal on the site of the loch,[46] but this was abandoned.[77] Soil excavated while laying the foundations of buildings in the New Town was dumped on the site of the loch to create the slope connecting the Old and New Towns known as The Mound. In the mid-19th century the National Gallery of Scotland and Royal Scottish Academy Building were built on The Mound, and tunnels for the railway line between Haymarket and Waverley stations were driven through it.

Southside

A popular residential part of the city is the Southside, which includes the districts of St Leonards, Marchmont, Newington, Sciennes, the Grange and Blackford. The Southside is broadly analogous to the area covered formerly by the Burgh Muir, and grew in popularity as a residential area after the opening of the South Bridge in the 1780s. These areas are particularly popular with families (many state and private schools are here), students (the central University of Edinburgh campus is based around George Square just north of Marchmont and the Meadows), and Napier University (with major campuses around Merchiston and Morningside). The area is also well provided with hotel and "bed and breakfast" accommodation for visiting festival-goers. These districts often feature in works of fiction. For example, Church Hill in Morningside, was the home of Muriel Spark's Miss Jean Brodie, [78] and Ian Rankin's Inspector Rebus lives in Marchmont and works in St Leonards. [79]

Leith

Leith was historically the port of Edinburgh, an arrangement of unknown date that was reconfirmed by the royal charter Robert the Bruce granted to the city in 1329.[80] It developed a separate identity from Edinburgh, which it still retains, and it was a matter of great resentment when the two burghs merged in 1920 into the county of Edinburgh.[81] Even today the parliamentary seat is known as 'Edinburgh North and Leith'. The loss of traditional industries and commerce—the last shipyard closed in 1983—has resulted in economic decline over the years.[citation needed] The Edinburgh Waterfront development, which has transformed the old dockland into a residential area with leisure amenities, has to some extent regenerated the area. With the redevelopment, Edinburgh has gained the business of cruise liner companies which now provide cruises to Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. Leith also has the Royal Yacht Britannia, berthed behind Ocean Terminal, and Easter Road, the home ground of Hibernian F.C.

Urban area

The urban area of Edinburgh is almost entirely contained within the City of Edinburgh Council boundary, merging with Musselburgh in East Lothian. Nearby towns close to the city borders include Dalkeith, Bonnyrigg, Loanhead, Newtongrange, Prestonpans, Tranent, Penicuik, Haddington, Livingston, Broxburn and Dunfermline. According to the European Statistical agency, Eurostat, Edinburgh lies at the heart of a Larger Urban Zone covering 1,724 square kilometres (666 sq mi) with a population of 778,000.[82]

Climate

Like much of the rest of Scotland, Edinburgh has a temperate, maritime climate which is relatively mild despite its northerly latitude.[83] Winter daytime temperatures rarely fall below freezing, and compare favourably with places such as Moscow, Labrador and Newfoundland which lie at similar latitudes.[83] Summer temperatures are normally moderate, rarely exceeding 22 °C (72 °F).[83] The highest temperature ever recorded in the city was 31.4 °C (88.5 °F) on 4 August 1975[83] at Turnhouse Airport. The lowest temperature recorded in recent years was −14.6 °C (5.7 °F) during December 2010 at Gogarbank.[84]

The proximity of the city to the sea mitigates any large variations in temperature or extremes of climate. Given Edinburgh's position between the coast and hills, it is renowned as a windy city, with the prevailing wind direction coming from the south-west which is associated with warm, unstable air from the North Atlantic Current that can give rise to rainfall – although considerably less than cities to the west, such as Glasgow.[83] Rainfall is distributed fairly evenly throughout the year.[83] Winds from an easterly direction are usually drier but colder, and may be accompanied by haar, a persistent coastal fog. Vigorous Atlantic depressions, known as European windstorms, can affect the city between October and May.[83]

| Climate data for Edinburgh, Royal Botanic Gardens, 1981–2010 Extremes 1951– | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.7 (54.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.5 (34.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

1.3 (34.3) |

5.9 (42.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.5 (4.1) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 67.5 (2.66) |

47.0 (1.85) |

51.7 (2.04) |

40.5 (1.59) |

48.9 (1.93) |

61.3 (2.41) |

65.0 (2.56) |

60.2 (2.37) |

63.7 (2.51) |

75.6 (2.98) |

62.1 (2.44) |

60.8 (2.39) |

704.3 (27.73) |

| Average rainy days | 12.5 | 9.4 | 9.9 | 8.8 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 9.7 | 10.2 | 12.4 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 124.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 53.5 | 78.5 | 114.8 | 144.6 | 188.4 | 165.9 | 172.2 | 161.5 | 128.8 | 101.2 | 71.0 | 46.2 | 1,426.6 |

| Source: Met Office[85] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Edinburgh, Gogarbank, 61m asl, 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

4.1 (39.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.1 (48.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.6 (38.5) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 76.3 (3.00) |

53.8 (2.12) |

55.9 (2.20) |

46.1 (1.81) |

49.0 (1.93) |

61.5 (2.42) |

64.1 (2.52) |

67.8 (2.67) |

58.0 (2.28) |

84.5 (3.33) |

73.7 (2.90) |

63.6 (2.50) |

754.3 (29.68) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13.6 | 9.8 | 11.8 | 9.8 | 11.4 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 12.9 | 137.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 45.5 | 69.6 | 106.9 | 136.3 | 188.3 | 154.1 | 170.7 | 149.0 | 125.5 | 96.1 | 65.2 | 35.3 | 1,420.7 |

| Source: Met Office[86] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Edinburgh, Turnhouse Airport, 37m asl, 1971–2000 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

1.1 (34.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 64 (2.5) |

45 (1.8) |

55 (2.2) |

40 (1.6) |

50 (2.0) |

55 (2.2) |

56 (2.2) |

55 (2.2) |

64 (2.5) |

70 (2.8) |

61 (2.4) |

68 (2.7) |

682.4 (26.87) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 48 | 67 | 99 | 133 | 179 | 170 | 170 | 152 | 119 | 91 | 65 | 41 | 1,334 |

| Source: MeteoFrance[87] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Current

| Edinburgh compared[88][89] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| UK Census 2001 | Edinburgh | Lothian | Scotland |

| Total population | 448,624 | 778,367 | 5,062,011 |

| Population growth 1991–2001 | 7.1% | 7.2% | 1.3% |

| White | 95.9% | 97.2% | 98.8% |

| Asian | 2.6% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| Under 16 years old | 16.3% | 18.6% | 19.2% |

| Over 65 years old | 15.4% | 14.8% | 16.0% |

| Christian | 54.8% | 58.1% | 65.1% |

| Muslim | 1.5% | 1.1% | 0.8% |

At the United Kingdom Census 2001, Edinburgh had a population of 448,624, a rise of 7.1% from 1991.[88] Estimates in 2010 placed the total resident population at 486,120 split between 235,249 males and 250,871 females.[70] This makes Edinburgh the second largest city in Scotland after Glasgow and the seventh largest in Britain.[88] Edinburgh sits at the heart of a Larger Urban Zone with a population of 778,000.[82]

Edinburgh has a higher proportion of those aged between 16 and 24 than the Scottish average, but has a lower proportion of those classified as elderly or pre-school.[70] Over 95% of Edinburgh respondents classed their ethnicity as White in 2001, while those identifying as being Indian and Chinese were 1.6% and 0.8% of the population respectively.[90] In 2001, 22% of the population were born outside Scotland with the largest group of people within this category being born in England at 12.1%.[90] Since the 2004 enlargement of the European Union, many migrants from the accession states such as Poland, Lithuania and Latvia have settled in the city, with many working in the service industry.[91]

Historical

A census conducted by the Edinburgh presbytery in 1592 recorded a population of 8,003 adults spread equally north and south of the High Street which runs down the spine of the ridge leading from the Castle.[92] In the 18th and 19th centuries, the population expanded rapidly, rising from 49,000 in 1751 to 136,000 in 1831 primarily due to migration from rural areas.[93] As the population grew, problems of overcrowding in the Old Town, particularly in the cramped tenements that lined the present day Royal Mile and the Cowgate, were exacerbated.[93] Poor sanitary arrangements resulted in a high incidence of disease,[93] with outbreaks of cholera occurring in 1832, 1848 and 1866.[94]

The construction of the New Town from 1767 onwards witnessed the migration of the professional and business classes from the difficult conditions of the Old Town to the lower density, higher quality surroundings taking shape on land to the north. [95] Expansion southwards from the Old Town saw more tenements being built in the 19th century, giving rise to Victorian suburbs such as Marchmont, Newington and Bruntsfield.[95]

Early 20th century population growth coincided with lower density suburban development. As the city expanded to the south and west, detached and semi-detached villas with large gardens replaced tenements as the predominant building style. Nonetheless, the 2001 census revealed that over 55% of Edinburgh's population were living in tenements or blocks of flats, a figure in line with other Scottish cities, but much higher than other British cities, and even central London.[96]

From the early to mid 20th century the growth in population, together with slum clearance in the Old Town and other areas such as Dumbiedykes, Leith and Fountainbridge, led to the creation of new estates such as Stenhouse and Saughton, Craigmillar and Niddrie, Pilton and Muirhouse, Piershill, and Sighthill.[97]

Religion

Christianity

The Church of Scotland claims the largest membership of any religious denomination in Edinburgh. As of 2010, there are 83 congregations in the Church of Scotland's Presbytery of Edinburgh.[98] Its most prominent church is St Giles' on the Royal Mile, first dedicated in 1243 but believed to date from before the 12th century.[99] Saint Giles is historically the patron saint of Edinburgh.[100] St Cuthbert's, situated at the west end of Princes Street Gardens in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle, lays claim to being the oldest Christian site in the city,[101][102] though the present building designed by Hippolyte Blanc dates from the late-19th century. Other Church of Scotland churches include the Canongate Kirk, Greyfriars Kirk, St Andrew's and St George's West Church and the Barclay Church. The Church of Scotland Offices are in Edinburgh,[103] as is the Assembly Hall where the General Assembly is held.[104]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh has 27 parishes across the city.[105] The leader of Scotland's Catholics has his official residence in the area of the city known locally as Holy Corner, and the diocesan offices are in Marchmont.[106] The Diocese of Edinburgh of the Scottish Episcopal Church has over 50 churches, half of them in the city.[107] Its centre is the late 19th century Gothic style St Mary's Cathedral in the West End's Palmerston Place.[108] There are several independent churches throughout the city, both Catholic and Protestant, including Charlotte Chapel), Carrubbers Christian Centre, Morningside Baptist Church, Bellevue Chapel and Sacred Heart.[109] There are also churches belonging to larger orders, such as Christadelphians,[110] Quakers and Seventh-day Adventists.

Other faiths

Edinburgh Central Mosque – Edinburgh's main mosque and Islamic Centre – is in Potterrow, on the city's south side, near Bristo Square. It was opened in the late 1990s and the construction was largely financed by a gift from King Fahd of Saudi Arabia.[111] There are other mosques in Annandale Street Lane, off Leith Walk, and in Queensferry Road, Blackhall as well as other Islamic centres across the city.[112] The first recorded presence of a Jewish community in Edinburgh dates back to the late 18th century.[113] Edinburgh's Orthodox synagogue, which was opened in 1932, is in Salisbury Road and can accommodate a congregation of 2000. A Liberal Jewish congregation also meets in the city. There are a Sikh gurdwara and a Hindu mandir, both in Leith, and a Brahma Kumaris centre[114] in the Polwarth area. Edinburgh Buddhist Centre, run by the Triratna Buddhist Community, is situated in Melville Terrace. Other Buddhist traditions are represented by groups which meet in the capital: the Community of Interbeing (followers of Thich Nhat Hanh), Rigpa, Samye Dzong, Theravadin, Pure Land and Shambala. There is a Sōtō Zen Priory in Portobello[115] and a Theravadin Thai Buddhist Monastery in Slateford Road.[116] Edinburgh is home to an active Baha'i Community,[117] and a Theosophical Society, in Great King Street.[118] Edinburgh has an active Inter-Faith Association.[119]

Governance

Following local government reorganisation in 1996, Edinburgh constitutes one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.[120] Like all other local authorities of Scotland, the council has powers over most matters of local administration such as housing, planning, local transport, parks, economic development and regeneration.[121] The council is composed of 58 elected councillors, returned from 17 multi-member electoral wards in the city.[122] Following the 2007 Scottish Local Elections the incumbent Labour Party lost majority control of the council, after 23 years, to a Liberal Democrat/SNP coalition.[123]

The city's coat of arms was registered by the Lord Lyon King of Arms in 1732.[124]

Edinburgh is represented in the Scottish Parliament. For electoral purposes, the city area is divided between six of the nine constituencies in the Lothians electoral region.[125] Each constituency elects one Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) by the first past the post system of election, and the region elects seven additional MSPs, to produce a form of proportional representation.[125]

Edinburgh is also represented in the British House of Commons by five Members of Parliament. The city is divided into Edinburgh North and Leith, Edinburgh East, Edinburgh South, Edinburgh South West, and Edinburgh West,[126] each constituency electing one member by the first past the post system.

Economy

Edinburgh has the strongest economy of any city in the United Kingdom outside of London and the highest percentage of professionals in the UK with 43% of the population holding a degree-level or professional qualification.[8] According to the Centre for International Competitiveness, it is the most competitive large city in the United Kingdom. [127] It also has the highest gross value added per employee of any city in the UK outside London, measuring £50,256 in 2007.[128] It was named European Best Large City of the Future for Foreign Direct Investment and Best Large City for Foreign Direct Investment Strategy in the Financial Times fDi magazine awards 2012/13.

Known primarily for brewing, banking, and printing and publishing in the 19th century, Edinburgh's economy is now based mainly on financial services, scientific research, higher education, and tourism.[citation needed] As of March 2010 unemployment in Edinburgh is comparatively low at 3.6%, and remains consistently below the Scottish average of 4.5%. [129]

Banking has been a mainstay of the Edinburgh economy for over 300 years, since the Bank of Scotland (now part of the Lloyds Banking Group) was established by an act of the Scottish Parliament in 1695. Today, the financial services industry, with its particularly strong insurance and investment sectors, and underpinned by Edinburgh based firms such as Scottish Widows and Standard Life, accounts for Edinburgh being the UK's second financial centre after London and Europe's fourth in terms of equity assets. [130] The Royal Bank of Scotland opened new global headquarters at Gogarburn in the west of the city in October 2005, and Edinburgh is home to the headquarters of Bank of Scotland, Tesco Bank[131] and Virgin Money.[132]

Tourism is also an important element in the city's economy. As a World Heritage Site, tourists come to visit historical sites such as Edinburgh Castle, the Palace of Holyroodhouse and the Old and New Towns. Their numbers are augmented in August each year during the Edinburgh Festivals, which attracts 4.4 million visitors,[129] and generates in excess of £100m for the Edinburgh economy.[133]

As the centre of Scotland's government and legal system, the public sector plays a central role in the economy of Edinburgh. Many departments of the Scottish Government are located in the city. Other major employers include NHS Scotland and local government administration.

Transport

Edinburgh Airport is Scotland's busiest and biggest airport and the principal international gateway to the capital, handling around 9 million passengers in 2012.[134] In anticipation of rising passenger numbers, the airport operator BAA outlined a draft masterplan in 2011 to provide for the expansion of the airfield and terminal building. The airport has since been sold to Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) in June 2012. The possibility of building a second runway to cope with an increased number of aircraft movements has also been mooted.[135]

Travel in Edinburgh is predominantly by bus. Lothian Buses operate the majority of city bus services within the city and to surrounding suburbs, with the majority of routes running via Princes Street. Services further afield operate from the Edinburgh Bus Station off St. Andrew Square. Lothian Buses, as the successor company to the Edinburgh Corporation Transport Department, also operates all of the City's branded public tour bus services, the night bus network and airport buses. [136] In 2010, Lothian Buses facilitated 109 million passenger journeys – a 1.9% rise on the previous year.[137]

Waverley is the second-busiest railway station in Scotland, with only Glasgow Central handling more passengers; in terms of passenger entries and exits between April 2010 and March 2011, Waverley is the fifth-busiest station outside London.[138] It serves as the terminus for trains arriving from London King's Cross and is the departure point for many rail services within Scotland operated by First ScotRail.

To the west of the city centre lies Haymarket railway station which is an important commuter stop. Opened in 2003, Edinburgh Park station serves the adjacent business park in the west of the city and the nearby Gogarburn headquarters of the Royal Bank of Scotland. The Edinburgh Crossrail connects Edinburgh Park with Haymarket, Waverley and the suburban stations of Brunstane and Newcraighall in the east of the city.[139] There are also commuter lines to South Gyle and Dalmeny, which serves South Queensferry by the Forth Bridges, and to the south west of the city out to Wester Hailes and Curriehill.

In order to tackle traffic congestion, Edinburgh is now served by six park and ride sites on the periphery of the city at Sheriffhall, Ingliston, Riccarton, Inverkeithing (in Fife), Newcraighall and Straiton. A referendum of Edinburgh residents in February 2005 rejected a proposal to introduce congestion charging in the city. [140]

Edinburgh has been without a tram system since 16 November 1956.[141] Following parliamentary approval in 2007, construction began on a new Edinburgh tram line in early 2008. The first stage of the project was originally expected to be completed by July 2011[142] but, following delays caused by extra utility work and a long-running contractual dispute between the Council and the main contractor, Bilfinger, it is unlikely to be operational before 2014.[143] The cost of the project rose from the original projection of £545 million to £750 million in mid-2011, and the final cost is expected to exceed £1 billion[144][145] for a curtailed project resulting in a line approximately 8 miles (13 km) in length. The current plan will see trams running from Edinburgh Airport to the west of the city to York Place in the city centre. The original intention to extend the line down Leith Walk to Ocean Terminal and Newhaven, was shelved because of spiralling costs.[146] If the original plan is ever resumed and taken to completion, trams will also run from Haymarket through Ravelston and Craigleith to Granton on the waterfront.[146] Long-term proposals envisage a line running west from the airport to Ratho and Newbridge, and another along the length of the waterfront.[147]

Education

There are four universities in Edinburgh (including Queen Margaret University which now lies just outwith the city boundary) with students making up around one-fifth of the population.[148] Established by Royal Charter in 1583, the University of Edinburgh is one of Scotland's ancient universities and is the fourth oldest in the country after St Andrews, Glasgow and Aberdeen.[149] Originally centred around Old College the university expanded to premises on The Mound, the Royal Mile and George Square.[149] Today, the King's Buildings in the south of the city contain most of the schools within the College of Science and Engineering. In 2002, the medical school moved to purpose built accommodation adjacent to the new Edinburgh Royal Infirmary at Little France. The University was placed 21st in the world in the 2012 QS World University Rankings.[150]

In the 1960s Heriot-Watt University and Napier Technical College were established.[149] Heriot-Watt traces its origins to 1821 as the world's first mechanics' institute, when a school for technical education for the working classes was opened.[151] Napier College was renamed Napier Polytechnic in 1986 and gained university status in 1992.[152] Edinburgh Napier University has campuses in the south and west of the city, including the former Craiglockhart Hydropathic and Merchiston Tower.[152] It is home to the Screen Academy Scotland.

Queen Margaret University was located in Edinburgh until its move to a new campus near Musselburgh in 2008.

Until 2012 further education colleges in the city included Jewel and Esk College (incorporating Leith Nautical College founded in 1903), Telford College, opened in 1968, and Stevenson College, opened in 1970. These have now been amalgamated to form Edinburgh College. The Scottish Agricultural College also has a campus in south Edinburgh. Other notable institutions include the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh which were established by Royal Charter, in 1506 and 1681 respectively. The Trustees Drawing Academy of Edinburgh was founded in 1760 – an institution that became the Edinburgh College of Art in 1907.[153]

There are 18 nursery, 94 primary and 23 secondary schools in Edinburgh administered by the city council.[154] Edinburgh is home to The Royal High School, one of the oldest schools in the country and the world. The city is home to several independent, fee-paying schools including Edinburgh Academy, Fettes College, George Heriot's School, George Watson's College, Merchiston Castle School, Stewart's Melville College and The Mary Erskine School. In 2009, the proportion of pupils in education at independent schools was 24.2%, far above the national average of just over 7% and higher than in any other region of Scotland.[155]

Healthcare

The main NHS Lothian hospitals serving the Edinburgh area are the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, which includes the University of Edinburgh Medical School, and the Western General Hospital,[156] which includes a large cancer treatment centre and the nurse-led Minor Injuries Clinic.[157] The Royal Edinburgh Hospital specialises in mental health; it is situated in Morningside. The Royal Hospital for Sick Children, often referred to as 'the Sick Kids', is a specialist pediatrics hospital.

There are two private hospitals, Murrayfield Hospital in the west of the city and Shawfield Hospital in the south; both are owned by Spire Healthcare.[156]

Culture

Festivals and celebrations

The city hosts the annual Edinburgh International Festival, which is one of many events running from the end of July until early September each year. The best-known of these events are the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Edinburgh International Festival, Edinburgh Military Tattoo and the Edinburgh International Book Festival.[158]

The longest established of these festivals is the Edinburgh International Festival, which was first held in 1947[159] and centres on a programme of high-profile theatre productions and classical music performances, featuring international directors, conductors, theatre companies and orchestras.[160]

This has since been overtaken both in size and popularity by the Edinburgh Fringe which began as a programme of marginal acts alongside the "official" Festival to become the largest performing arts festival in the world. In 2006, 1867 different shows were staged in 261 venues throughout the city.[161] Comedy has become one of the mainstays of the Fringe, with numerous notable comedians getting their first 'break' here, often by receiving the Edinburgh Comedy Award.[162] In 2008 the largest comedy venues "on the Fringe" launched the Edinburgh Comedy Festival as a festival within a festival.

Alongside these major festivals, there is also the Edinburgh Art Festival, Edinburgh International Film Festival (moved to June as of 2008), the Edinburgh Jazz and Blues Festival, and the Edinburgh International Book Festival. The Edge Festival (formerly known as T on the Fringe), a popular music offshoot of the Fringe, began in 2000, replacing the smaller Flux and Planet Pop series of shows.[163]

The Edinburgh Military Tattoo, one of the centrepieces of the "official" Festival, occupies the Castle Esplanade every night, with massed pipers and military bands drawn from around the world. Performances end with a short fireworks display. As well as the various summer festivals there is also the Edinburgh International Science Festival held annually in April. It is one of the largest of its kind in Europe.[164]

The annual Hogmanay celebration was originally a street party held on the Royal Mile focused on the Tron Kirk; it has been officially organised since 1993, with the focus moved to Princes Street. In 1996, over 300,000 people attended, leading to ticketing of the main street party in later years, with a limit of 100,000 tickets.[165] Hogmanay now covers four days of processions, concerts and fireworks, with the street party commencing on Hogmanay. Alternative tickets are available for entrance into the Princes Street Gardens concert and Céilidh, where well-known artists perform and ticket holders can participate in traditional Scottish céilidh dancing. The event attracts thousands of people from all over the world.[165]

On the night of 30 April, the Beltane Fire Festival takes place on Calton Hill. The festival involves a procession followed by the re-enactment of scenes inspired by pagan spring fertility celebrations.[166] At the beginning of October each year, the Dussehra Hindu Festival is also held on Calton Hill.[167]

Music, theatre and film

Outside the Festival season, Edinburgh continues to support theatres and production companies. The Royal Lyceum Theatre has its own company, while the King's Theatre, Edinburgh Festival Theatre, and Edinburgh Playhouse stage large touring shows. The Traverse Theatre presents a more contemporary programme of plays. Amateur theatre companies productions are staged at the Bedlam Theatre, Church Hill Theatre, and the King's Theatre among others.[168]

The Usher Hall is Edinburgh's premier venue for classical music, as well as occasional popular music gigs.[169] It was also the venue for the Eurovision Song Contest 1972. Other halls staging music and theatre include The Hub, the Assembly Rooms and the Queen's Hall. The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is based in Edinburgh.[170] The Brunton Theatre also renowned for quality music, theatre, dance and film all year round, classical music and dance programs.

Edinburgh has two repertory cinemas, the Edinburgh Filmhouse, and the Cameo, and the independent Dominion Cinema, as well as a range of multiplexes.[171]

Edinburgh has a healthy popular music scene. Occasional large gigs are staged at Murrayfield and Meadowbank, with mid-sized events at venues such as the Corn Exchange, HMV Picture House, the Liquid Rooms, and the Bongo Club. In 2010, PRS for Music listed Edinburgh among the UK's top ten 'most musical' cities.[172]

Edinburgh is also home to a flourishing group of contemporary composers such as Nigel Osborne, Peter Nelson, Lyell Cresswell, Hafliði Hallgrímsson, Edward Harper, Robert Crawford, Robert Dow and John McLeod[173] whose music is heard regularly on BBC Radio 3 and throughout the UK.

Rockstar North, previously known as DMA Design, known for creating the Grand Theft Auto series, are based in Edinburgh.[174]

Media

The Edinburgh Evening News is based in Edinburgh and published every day apart from Sunday. The newspaper's owners, Johnson Press, also hold The Scotsman, a national paper which is published in the city. The Herald, which is published in Glasgow, also covers Edinburgh.[175]

The city has two commercial radio stations: Forth One, a station with a mainstream chart music output, and Forth 2 on medium wave which plays classic hits.[176] Capital Radio Scotland and Real Radio Scotland also have transmitters in Edinburgh. Along with the UK national radio stations, Radio Scotland and the Gaelic language service BBC Radio nan Gàidheal are also broadcast. DAB digital radio is broadcast over two local multiplexes.

Television, along with most radio services, are broadcast to the city from the Craigkelly transmitting station situated on the opposite side of the Firth of Forth.[177]

Museums, libraries and galleries

Edinburgh has many museums and libraries, some of which are national institutions. These include the National Museum of Scotland, the National Library of Scotland, National War Museum of Scotland, the Museum of Edinburgh and the Museum of Childhood.[178]

Edinburgh Zoo, covering 82 acres (33 ha) on Corstorphine Hill, is the second most popular paid tourist attraction in Scotland,[179] and currently home to two giant pandas, Tian Tian and Yang Guang, on loan from the People's Republic of China.

Edinburgh contains Scotland's five National Galleries as well as numerous smaller galleries.[180] The national collection is housed in the National Gallery of Scotland, located on the Mound, and now linked to the Royal Scottish Academy, which holds regular major exhibitions of painting. Contemporary collections are shown in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, and the nearby Dean Gallery. The Scottish National Portrait Gallery focuses on portraits and photography.

The council-owned City Art Centre shows regular art exhibitions. Across the road, The Fruitmarket Gallery offers world class exhibitions of contemporary art, featuring work by British and international artists with both emerging and established international reputations.[181]

There are many private galleries, including Ingleby Gallery, the latter providing a varied programme including shows by Callum Innes, Peter Liversidge, Ellsworth Kelly, Richard Forster, and Sean Scully.[182]

The city hosts several of Scotland's galleries and organisations dedicated to contemporary visual art. Significant strands of this infrastructure include: The Scottish Arts Council, Edinburgh College of Art, Talbot Rice Gallery (University of Edinburgh) and the Edinburgh Annuale.

Shopping

The locale around Princes Street is the main shopping area in the city centre, with souvenir shops, chains such as Boots and H&M as well as Jenners.[183] George Street, north of Princes Street, is home to some upmarket chains and independent stores.[183] The St. James Centre, at the eastern end of George Street and Princes Street, hosts national chains including a large John Lewis.[184] Multrees Walk, adjacent to the St. James Centre, is a recent addition to the city centre, anchored by Harvey Nichols and hosting Louis Vuitton, Emporio Armani, Mulberry and Calvin Klein.[183]

Edinburgh also has substantial retail developments outside the city centre. These include The Gyle Shopping Centre and Hermiston Gait in the west of the city, Cameron Toll Shopping Centre, Straiton Retail Park and Fort Kinnaird in the south and east, and Ocean Terminal to the north, on the Leith waterfront.[185]

Sport

Football

Edinburgh has two professional football clubs: Heart of Midlothian, founded in 1874 and Hibernian, founded in 1875. Both teams play in the Scottish Premier League and they are known locally as "Hearts" and "Hibs".[186] They are the oldest city rivals in Scotland and the Edinburgh derby is one of the oldest derby matches in world football.[citation needed]

Edinburgh was also home to senior sides St Bernard's, and Leith Athletic. Most recently, Meadowbank Thistle played at Meadowbank Stadium until 1995, when the club moved to Livingston, becoming Livingston F.C.. Previously, Meadowbank Thistle had been named Ferranti Thistle. The Scottish national team has occasionally played at Easter Road and Tynecastle.

Rugby union

The Scotland national rugby union team as well as the professional Edinburgh Rugby plays at Murrayfield Stadium, which is owned by the Scottish Rugby Union and is also used as a venue for other events, including music concerts. It is the largest capacity stadium in Scotland, with 67130 seats after the installation of large screens.[187] Edinburgh is also home to RBS Premier One rugby teams Heriot's Rugby Club, Boroughmuir RFC, the Edinburgh Academicals and Currie RFC.[188]

-

Edinburgh Marathon

-

Murrayfield Ice Rink

Other sports

The Scottish cricket team, which represents Scotland at cricket internationally and in the Friends Provident Trophy, play their home matches at the Grange cricket club.[189]

The Edinburgh Capitals are the latest of a succession of ice hockey clubs to represent the Scottish capital. Previously Edinburgh was represented by the Murrayfield Racers and the Edinburgh Racers. The club play their home games at the Murrayfield Ice Rink The club play their home games at the Murrayfield Ice Rink and have competed in the ten-team professional Elite Ice Hockey League since the 2005–06 season.[190][191]

The Edinburgh Diamond Devils is a baseball club claiming its first Scottish Championship in 1991 as the "Reivers." 1992 saw the team repeat as national champions, becoming the first team to do so in league history and saw the start of the club's first youth team, the Blue Jays. The name of the club was changed in 1999.[192]

Edinburgh has also hosted various national and international sports events including the World Student Games, the 1970 British Commonwealth Games,[193] the 1986 Commonwealth Games[193] and the inaugural 2000 Commonwealth Youth Games.[194] For the Games in 1970 the city built major Olympic standard venues and facilities including the Royal Commonwealth Pool and the Meadowbank Stadium. The Royal Commonwealth Pool is undergoing refurbishment and due to re-open for spring 2012, will host the Diving competition of the 2014 Commonwealth Games, held by Glasgow.[195]

In American football, the Scottish Claymores played WLAF/NFL Europe games at Murrayfield, including their World Bowl 96 victory. From 1995 to 1997 they played all their games there, from 1998 to 2000 they split their home matches between Murrayfield and Glasgow's Hampden Park, then moved to Glasgow full-time, with one final Murrayfield appearance in 2002.[196] The city's most successful non-professional team are the Edinburgh Wolves who play at Meadowbank Stadium.[197]

The Edinburgh Marathon has been held in the city since 2003 with more than 16,000 taking part annually.[198] It is called by its organisers "the fastest marathon in the UK" due to the elevation drop of 40 metres (130 ft).[199] The city also has a half-marathon, as well as 10 km and 5 km races, including a 5 km race on 1 January each year.

Edinburgh has a speedway team, the Edinburgh Monarchs, which is based outside the city at the Lothian Arena in Armadale, West Lothian. The Monarchs have won the Premier League championship three times in their history, in 2003[200] again in 2008[201] and yet again in 2010.

Edinburgh Eagles are a rugby league team who play in the Rugby League Conference Scotland Division. Murrayfield Stadium has also hosted the Magic Weekend where all Super League matches are played (at Murrayfield) all on the one weekend.

Notable residents

Edinburgh has a long literary tradition, which became especially evident during the Scottish Enlightenment, and in more recent years was declared the first UNESCO City of Literature in 2004.[202][203] Famous authors of the city include the economist Adam Smith, born in Kirkcaldy and author of The Wealth of Nations, [204] James Boswell biographer of Samuel Johnson; Sir Walter Scott, the author of famous titles such as Rob Roy, Ivanhoe, and Heart of Midlothian; James Hogg, author of The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner; Robert Louis Stevenson, creator of Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes; Muriel Spark, author of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie; Irvine Welsh, author of Trainspotting, whose novels are mostly set in the city and often written in colloquial Scots; [205] Ian Rankin, author of the Inspector Rebus series of crime thrillers; Alexander McCall Smith, author of nonfiction as well as the No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency series;[206] and J. K. Rowling, the creator of Harry Potter, who began her first book in an Edinburgh coffee shop.[207]

Scotland has a rich history in science and engineering, with Edinburgh contributing its fair share of famous names. James Clerk Maxwell, the founder of the modern theory of electromagnetism, was born here and educated at the Edinburgh Academy and University of Edinburgh, [204] as was the engineer and telephone pioneer Alexander Graham Bell.[204] Other names connected with the city include Max Born, physicist and Nobel laureate;[208] Charles Darwin, the biologist who discovered natural selection;[204] David Hume, a philosopher, economist and historian;[204] James Hutton, regarded as the "Father of Geology";[204] John Napier inventor of logarithms;[209] Joseph Black chemist and one of the founders of thermodynamics;[204] pioneering medical researchers Joseph Lister and James Young Simpson;[204] chemist and discoverer of the element nitrogen Daniel Rutherford, Colin Maclaurin, mathematician and developer of the Maclaurin series,[210] and Ian Wilmut, the geneticist involved in the cloning of Dolly the sheep just outside Edinburgh.[204] The stuffed carcass of Dolly the sheep is now on display in the National Museum of Scotland.[211]

Edinburgh has been the birthplace of actors like Alastair Sim and Sir Sean Connery, famed as the first cinematic James Bond;[212] the comedian and actor Ronnie Corbett, best known as one of The Two Ronnies[213] and the impressionist Rory Bremner. Famous city artists include the portrait painters Sir Henry Raeburn, Sir David Wilkie and Allan Ramsay.

The city has produced or been home to musicians who have been extremely successful in modern times, particularly Ian Anderson, frontman of the band Jethro Tull; The Incredible String Band; The Corries; Wattie Buchan, lead singer and founding member of punk band The Exploited; Shirley Manson, lead singer for the band Garbage; the Bay City Rollers; The Proclaimers; Boards of Canada; and Idlewild.

Edinburgh is the birthplace of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair who attended the city's Fettes College.[214]

Famous criminals from Edinburgh's history include Deacon Brodie, deacon of a trades guild and an Edinburgh city councillor by day and burglar by night, who is said to have been the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson's story, the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde,[215] and murderers Burke and Hare who provided fresh corpses for anatomical dissection by the famous surgeon Robert Knox.[216]

Another well-known Edinburgh resident was Greyfriars Bobby. The small Skye Terrier reputedly kept vigil over his dead master's grave in Greyfriars Kirkyard for 14 years in the 1860s and 1870s, giving rise to a story of canine devotion which plays a part in attracting visitors to the city.[217]

Twinning arrangements

The City of Edinburgh has entered into 11 international twinning arrangements since 1954.[218] Most of the arrangements are styled as 'Twin Cities', but the agreement with Kraków is designated as a 'Partner City'.[218] The agreement with the Kyoto Prefecture, concluded in 1994, is officially styled as a 'Friendship Link', reflecting its status as the only region to be twinned with Edinburgh.[218]

- Munich, Germany (1954)

- Nice, France (1958)[219][220]

- Florence, Italy (1964)

- Dunedin, New Zealand (1974)

- Vancouver, Canada (1977)[221]

- San Diego, United States (1977)

- Xi'an, China (1985)

- Kiev, Ukraine (1989)

- Aalborg, Denmark (1991)

- Kyoto Prefecture, Japan (1994)

- Kraków, Poland (1995)[222]

- Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia (1996)

See also

References

- ^ "Population and living conditions in Urban Audit cities, larger urban zone (LUZ)". Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ "Estimated population by sex, single year of age and administrative area, mid-2011" (PDF). Retrieved 16 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "City of Edinburgh factsheet" (PDF). gro-scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Population and living conditions in Urban Audit cities, larger urban zone (LUZ)". Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "University of Edinburgh". Universitas 21. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "University world rankings". topuniversities.com. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Education in Edinburgh". Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Working in Edinburgh". Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "Aberdeen only UK city to create more wealth this year". UHY Hacker Young chartered accountants. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "The UK Competitiveness Index 2010". Centre for International Competitiveness. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "Financial Times fDi Magazine awards 2012/13". edinburgh.gov.uk. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "City of Literature". cityofliterature.com. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Edinburgh-World Heritage Site". VisitScotland. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Quality of life". Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "Edinburgh second in TripAdvisor UK tourism poll". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Williams, Ifor (1972). The Beginnings of Welsh Poetry: Studies. University of Wales Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-7083-0035-9.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora K. (1968). The British Heroic Age: the Welsh and the Men of the North. University of Wales Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-7083-0465-6.

- ^ Dumville, David (1994). "The eastern terminus of the Antonine Wall: 12th or 13th century evidence". Proceedings of the Society of the Antiquaries of Scotland. 124: 293–298.

- ^ Cessford, Craig (1994). "Gardens of the 'Gododdin'". Garden History. 22 (1): 114–115.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World. McFarland. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ^ In full burgo meo de Edwinesburg.

- ^ The Topographical, Statistical, and Historical Gazeteer of Scotland: A-H. 1842. p. 800. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Coghill, Hamish (2008). Lost Edinburgh. Birlinn Ltd. pp. 1–2. ISBN 1-84158-747-8.

- ^ Ritchie, J. N. G. and A. (1972). Edinburgh and South-East Scotland. Heinemann. p. 51. ISBN 0-435-32971-5.

- ^ Fraser, James (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. Edinburgh University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-7486-1232-7. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Watson, William (1926). The Celtic Place Names of Scotland. p. 340. ISBN 1-906566-35-6.

- ^ Lynch, Micheal (2001). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford University Press. p. 658. ISBN 978-0-19-923482-0.

- ^ Daiches, David (1978). Edinburgh. Hamish Hamilton. p. 15. ISBN 0-241-89878-1.

- ^ Dickinson, W C (1961). Scotland, From The Earliest Times To 1603. Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson. p. 119.

- ^ Dickinson, W C (1961). Scotland, From The Earliest Times To 1603. Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson. pp. 236–8.

- ^ Donaldson, Gordon (1960). The Scottish Reformation. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-521-08675-2.

- ^ "Scottish Covenanter Memorials Association". covenanter.org. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Donaldson, Gordon (1967). Scottish Kings. Batsford. p. 213.

- ^ Newman, P R (1990). Companion To The English Civil Wars. Oxford: Facts On File Ltd. p. 13. ISBN 0-8160-2237-2.

- ^ Stephen C. Manganiello (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639–1660. Scarecrow Press. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-8108-5100-9. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ Chambers, Robert. Notices of the most remarkable fires in Edinburgh, from 1385 to 1824. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Neil. Edinburgh Encounter. p. 37. ISBN 1-74179-306-8.

- ^ Scott, Paul (1979). 1707: the Union of Scotland and England. Chambers. pp. 51–54. ISBN 0-550-20265-X.

- ^ Kelly (1998). The making of the United Kingdom and Black peoples of the Americas. Heinemann. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-435-30959-6. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ Defoe, Daniel (1978). A Tour Through The Whole Island Of Britain. London: Penguin. p. 577"... I believe, this may be said with truth, that in no city in the world so many people live in so little room as at Edinburgh."

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Topham, E. (1971). Letters from Edinburgh 1774–1775. Edinburgh: James Thin. p. 27. ISBN 1-236-68255-6. Retrieved 18 March 2013"... I make no manner of doubt but that the High Street in Edinburgh is inhabited by a greater number of persons than any street in Europe."

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Graham, H. G. (1906). The Social Life Of Scotland In The Eighteenth Century. London: Adam and Charles Black. p. 85. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Lenman, Bruce (1986). The Jacobite Cause. Richard Drew Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 0-86267-159-0. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Ferguson, W (1987). Scotland, 1689 to the Present. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-901824-86-0--These clans were mainly Episcopalian (70 per cent) and Roman Catholic (30 per cent), p.151

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Keay, K; Keay, J (1994). Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. HarperCollins. p. 285. ISBN 0-00-255082-2.

- ^ a b "History of Princes Street". princes-street.com. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ William Robertson (1997). William Robertson and the expansion of empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ Blackwood's Edinburgh magazine, Volume 11. 1822. p. 323. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Youngson, A J (1988). The Making of Classical Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 256. ISBN 0-85224-576-9.

- ^ Pryde, George Smith (1962). Scotland from 1603 to the present day. Nelson. p. 141.

Population figures for 1801 - Glasgow 77,385; Edinburgh 82,560; for 1821 - Glasgow 147,043; Edinburgh 138,325

- ^ Hogg, A (1973). "Topic 3:Problem Areas". Scotland: The Rise of Cities 1694–1905. London: Evans Brothers Ltd. ISBN 0237228354.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ McWilliam, C (1975). Scottish Townscape. London: Collins. p. 196. ISBN 0-00-216743-3.

- ^ McWilliam, C (1975). Scottish Townscape. London: Collins. p. 197. ISBN 0-00-216743-3.

- ^ Coghill, H (2008). Lost Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-1-84158-747-9.

- ^ Keay, John (1994). Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. 1994. p. 286. ISBN 0-00-255082-2.

- ^ a b Rae, William (1994). Edinburgh, Scotland's Capital City. Mainstream. p. 164. ISBN 1-85158-605-9.

- ^ "Scotland Act 1998". 19 November 1998. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ Geographia Atlas of the World (Map). London: Geographia Ltd. 1984. p. 99. ISBN 0-09-202840-3.

- ^ "Seven Hills of Edinburgh". VisitScotland. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ "Voltaire said: Athens of the North". Scotland.org. September 2003. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ "Seven Hills of Edinburgh Race & Challenge: The Course". Seven-Hills.org.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Edwards, Brian; Jenkins, Paul (2005). Edinburgh: The Making of a Capital City. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 0-7486-1868-6.

- ^ Stuart Piggott (1982). Scotland before History. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-85224-470-3.

- ^ "Sill". landforms.eu. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Overview of the Water of Leith". Gazetteer for Scotland, Institute of Geography, University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ "The Water of Leith Walkway". Water of Leith Conservation Trust. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Review of Green Belt policy in Scotland – Edinburgh and Midlothian". Scottish Government. 11 August 2004. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ^ "Edinburgh Areas". edinburghguide.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Edinburgh area guide". timeout.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ a b c "General Register Office for Scotland – mid-2011 population estimates by sex, single year of age and administrative area" (PDF).

- ^

Harris, Stuart (2002). The Place Names of Edinburgh. London: Steve Savage. p. 497. ISBN 1 904246 06 0--The name was first used in 1901, but became popular after the publication of a guidebook in 1920

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Old and New Towns of Edinburgh". UNESCO. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1824). Notices of the most remarkable fires in Edinburgh: from 1385 to 1824 ... Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ Cruft, Kitty. "James Craig 1739-1795: Correction of his Date of Birth". Book of the Old Edinburgh Club. New Series Vol. 5: pp.103–5.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Scottish Architects Homecoming" (PDF). Historic Scotland. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ "Bute House". edinburghguide.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "From monks on strike to dove's dung". scotsman.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie". geraldinemcewan.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Inspector Rebus Novels". ianrankin.net. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Edinburgh Corporation (1929). Edinburgh 1329–1929, Sexcentenary of Bruce Charter. Edinburgh: Oliver And Boyd. p. xxvii.

- ^ "The Story of Leith XXXIII. How Leith was Governed".

- ^ a b "Urban Audit City Profiles – Edinburgh". Eurostat. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Regional Climate – Eastern Scotland". Met Office. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ "December 2010 minimum". Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "Mean Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh Climatic Averages 1981–2010". Met Office. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ "Edinburgh 1981–2010 averages". Met Office. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ "Mean Temp Data". MeteoFrance. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "Edinburgh Comparisons – Population and Age Structure" (PDF). City of Edinburgh Council. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ "Comparative Population Profile – Edinburgh Locality". Scotland's Census Results Online (SCROL). Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Edinburgh Comparisons – Ethnicity, Country of Birth & Migration" (PDF). City of Edinburgh Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ Orchard, Pam (20 December 2007). "A Community Profile of EU8 Migrants in Edinburgh and an Evaluation of their Access to Key Services". Scottish Government. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lynch, Micheal (2001). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. OUP Oxford. p. 219. ISBN 0-19-969305-6.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Brian; Jenkins, Paul (2005). Edinburgh: The Making of a Capital City. p. 9. ISBN 0-7486-1868-6.

- ^ Gilbert (ed.), W M (1901). Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century. Edinburgh: J & R Allan Ltd. pp. 95, 120, 140.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Edwards, Brian; Jenkins, Paul (2005). Edinburgh: The Making of a Capital City. p. 46. ISBN 0-7486-1868-6.

- ^ "Edinburgh Comparisons – Dwellings" (PDF). City of Edinburgh Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "A BRIEF HISTORY OF EDINBURGH, SCOTLAND". localhistories.org. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Church of Scotland Yearbook, 2010–2011 edition. St Andrew Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-86153-610-8.

- ^ "St Giles' Cathedral Edinburgh -Building and History". Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Saint Giles Cathedral". edinburghnotes.com. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ "St Cuthbert's History". The Parish Church of St Cuthbert. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "St Cuthbert's History". The Parish Church of St Cuthbert. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "The Church of Scotland". Church of Scotland. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "General Assembly". Church of Scotland. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Parish List". Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Contact". Archdiocese-edinburgh.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Who we are". Diocese of Edinburgh. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh". Diocese of Edinburgh. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Independent Churches". scottishchristian.com. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Edinburgh Christadelphian Church". searchforhope.org. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "King Fahd Mosque and Islamic Centre". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ "Mosques in Edinburgh around edinburgh area". Mosquedirectory.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ "Edinburgh Hebrew Congregation".

- ^ "Brahma Kumaris Official Website – Around the UK". Bkwsu.org. Retrieved 13 February 2013.