David Bowie

David Bowie | |

|---|---|

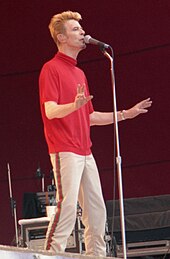

Bowie in 2002 | |

| Born | David Robert Jones 8 January 1947 London, England |

| Died | 10 January 2016 (aged 69) New York City, US |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1962–2016 |

| Works | |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 2, including Duncan Jones |

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of |

|

| Past members | Full list |

| Website | davidbowie |

David Robert Jones (8 January 1947 – 10 January 2016), known professionally as David Bowie (/ˈboʊi/ BOH-ee),[1] was an English singer, songwriter, musician and actor. Regarded as one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, Bowie was acclaimed by critics and musicians, particularly for his innovative work during the 1970s. His career was marked by reinvention and visual presentation, and his music and stagecraft has had a significant impact on popular music.

Bowie developed an interest in music from an early age. He studied art, music and design before embarking on a professional career as a musician in 1963. He released a string of unsuccessful singles with local bands and a self-titled solo album (1967) before achieving his first top-five entry on the UK Singles Chart with "Space Oddity" (1969). After a period of experimentation, he re-emerged in 1972 during the glam rock era with the flamboyant and androgynous alter ego Ziggy Stardust. The character was spearheaded by the success of "Starman" and its album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (both 1972), which won him widespread popularity. In 1975, Bowie's style shifted towards a sound he characterised as "plastic soul", initially alienating many of his UK fans but garnering his first major US crossover success with the number-one single "Fame" and the album Young Americans (both 1975). In 1976, Bowie starred in the cult film The Man Who Fell to Earth and released Station to Station. In 1977, he again changed direction with the electronic-inflected album Low, the first of three collaborations with Brian Eno that came to be known as the Berlin Trilogy. "Heroes" (1977) and Lodger (1979) followed; each album reached the UK top five and received lasting critical praise.

After uneven commercial success in the late 1970s, Bowie had three number-one hits: the 1980 single "Ashes to Ashes", its album Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) and "Under Pressure" (a 1981 collaboration with Queen). He achieved his greatest commercial success in the 1980s with Let's Dance (1983). Between 1988 and 1992, he fronted the hard rock band Tin Machine before resuming his solo career in 1993. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Bowie continued to experiment with musical styles, including industrial and jungle. He also continued acting; his roles included Major Jack Celliers in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983), Jareth the Goblin King in Labyrinth (1986), Phillip Jeffries in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), Andy Warhol in the biopic Basquiat (1996), and Nikola Tesla in The Prestige (2006), among other film and television appearances and cameos. He ceased touring after 2004 and his last live performance was at a charity event in 2006. He returned from a decade-long recording hiatus in 2013 with The Next Day and remained musically active until his death from liver cancer in 2016. He died two days after both his 69th birthday and the release of his final album, Blackstar.

During his lifetime, his record sales, estimated at over 100 million worldwide, made him one of the best-selling musicians of all time. He is the recipient of numerous accolades, including six Grammy Awards and four Brit Awards. Often dubbed the "chameleon of rock" due to his constant musical reinventions, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996. Rolling Stone ranked him among the greatest singers, songwriters and artists of all time. As of 2022, Bowie was the best-selling vinyl artist of the 21st century.

Early life

David Robert Jones was born on 8 January 1947 in Brixton, London.[2] His mother, Margaret Mary "Peggy" (née Burns),[3] was born at Shorncliffe Army Camp near Cheriton, Kent.[4] Her paternal grandparents were Irish immigrants who had settled in Manchester.[5] She worked as a waitress at a cinema in Royal Tunbridge Wells.[6] His father, Haywood Stenton "John" Jones,[3] was from Doncaster, Yorkshire,[7] and worked as a promotions officer for the children's charity Barnardo's. The family lived at 40 Stansfield Road, on the boundary between Brixton and Stockwell in the south London borough of Lambeth. Bowie attended Stockwell Infants School until he was six, acquiring a reputation as a gifted and single-minded child—and a defiant brawler.[8]

From 1953, Bowie moved with his family to Bickley and then Bromley Common, before settling in Sundridge Park in 1955 where he attended Burnt Ash Junior School.[9] His voice was considered "adequate" by the school choir, and he demonstrated above-average abilities in playing the recorder. At the age of nine, his dancing during the newly introduced music and movement classes was strikingly imaginative: teachers called his interpretations "vividly artistic" and his poise "astonishing" for a child.[10] The same year, his interest in music was further stimulated when his father brought home a collection of American 45s by artists including the Teenagers, the Platters, Fats Domino, Elvis Presley and Little Richard.[11][12] Upon listening to Little Richard's song "Tutti Frutti", Bowie later said that he had "heard God".[13]

Bowie was first impressed with Presley when he saw his cousin Kristina dance to "Hound Dog" soon after its release in 1956.[12] According to Kristina, she and David "danced like possessed elves" to records of various artists.[14] By the end of the following year, Bowie had taken up the ukulele and tea-chest bass, begun to participate in skiffle sessions with friends, and had started to play the piano; meanwhile, his stage presentation of numbers by both Presley and Chuck Berry—complete with gyrations in tribute to the original artists—to his local Wolf Cub group was described as "mesmerizing ... like someone from another planet".[12] Having encouraged his son to follow his dreams of being an entertainer since he was a toddler, in the late 1950s David's father took him to meet singers and other performers preparing for the Royal Variety Performance, introducing him to Alma Cogan and Tommy Steele.[14] After taking his eleven-plus exam at the conclusion of his Burnt Ash Junior education, Bowie went to Bromley Technical High School.[15] It was an unusual technical school, as biographer Christopher Sandford wrote:

Despite its status it was, by the time David arrived in 1958, as rich in arcane ritual as any [English] public school. There were houses named after eighteenth-century statesmen like Pitt and Wilberforce. There was a uniform and an elaborate system of rewards and punishments. There was also an accent on languages, science and particularly design, where a collegiate atmosphere flourished under the tutorship of Owen Frampton. In David's account, Frampton led through force of personality, not intellect; his colleagues at Bromley Tech were famous for neither and yielded the school's most gifted pupils to the arts, a regime so liberal that Frampton actively encouraged his own son, Peter, to pursue a musical career with David, a partnership briefly intact thirty years later.[15]

Bowie's maternal half-brother, Terry Burns, was a substantial influence on his early life.[16] Burns, who was 10 years older than Bowie, had schizophrenia and seizures, and lived alternately at home and in psychiatric wards; while living with Bowie, he introduced the younger man to many of his lifelong influences, such as modern jazz, Buddhism, Beat poetry and the occult.[17] In addition to Burns, a significant proportion of Bowie's extended family members had schizophrenia spectrum disorders, including an aunt who was institutionalised and another who underwent a lobotomy; this has been labelled as an influence on his early work.[16]

Bowie studied art, music and design, including layout and typesetting. After Burns introduced him to modern jazz, his enthusiasm for players like Charles Mingus and John Coltrane led his mother to give him a Grafton saxophone in 1961. He was soon receiving lessons from baritone saxophonist Ronnie Ross.[18][19]

He received a serious injury at school in 1962 when his friend George Underwood punched him in the left eye during a fight over a girl.[20] After a series of operations during a four-month hospitalisation,[21] his doctors determined that the damage could not be fully repaired and Bowie was left with faulty depth perception and anisocoria (a permanently dilated pupil), which gave a false impression of a change in the iris' colour, erroneously suggesting he had heterochromia iridum (one iris a different colour to the other); his eye later became one of Bowie's most recognisable features.[22] Despite their altercation, Bowie remained on good terms with Underwood, who went on to create the artwork for Bowie's early albums.[23]

Music career

1962–1967: Early career to debut album

Bowie formed his first band, the Konrads, in 1962 at the age of 15. Playing guitar-based rock and roll at local youth gatherings and weddings, the Konrads had a varying line-up of between four and eight members, Underwood among them.[24] When Bowie left the technical school the following year, he informed his parents of his intention to become a pop star. His mother arranged his employment as an electrician's mate. Frustrated by his bandmates' limited aspirations, Bowie left the Konrads and joined another band, the King Bees. He wrote to the newly successful washing-machine entrepreneur John Bloom inviting him to "do for us what Brian Epstein has done for the Beatles—and make another million." Bloom did not respond to the offer, but his referral to Dick James's partner Leslie Conn led to Bowie's first personal management contract.[25]

Conn quickly began to promote Bowie. His debut single, "Liza Jane", credited to Davie Jones with the King Bees, was not commercially successful.[26][27] Dissatisfied with the King Bees and their repertoire of Howlin' Wolf and Willie Dixon covers, Bowie quit the band less than a month later to join the Manish Boys, another blues outfit, who incorporated folk and soul—"I used to dream of being their Mick Jagger", he recalled.[25] Their cover of Bobby Bland's "I Pity the Fool" was no more successful than "Liza Jane", and Bowie soon moved on again to join the Lower Third, a blues trio strongly influenced by the Who. "You've Got a Habit of Leaving" fared no better, signalling the end of Conn's contract. Declaring that he would exit the pop music world "to study mime at Sadler's Wells", Bowie nevertheless remained with the Lower Third. His new manager, Ralph Horton, later instrumental in his transition to solo artist, helped secure him a contract with Pye Records. Publicist Tony Hatch signed Bowie on the basis that he wrote his own songs.[28] Dissatisfied with Davy (and Davie) Jones, which in the mid-1960s invited confusion with Davy Jones of the Monkees, he took on the stage name David Bowie after the 19th-century American pioneer James Bowie and the knife he had popularised.[29][30][31] His first release under the name was the January 1966 single "Can't Help Thinking About Me", recorded with the Lower Third.[32] It flopped like its predecessors.[33]

Bowie departed the Lower Third after the single's release, partly due to Horton's influence,[32] and released two more singles for Pye, "Do Anything You Say" and "I Dig Everything", both of which featured a new band called the Buzz, before signing with Deram Records.[27] Around this time Bowie also joined the Riot Squad; their recordings, which included one of Bowie's original songs and material by the Velvet Underground, went unreleased. Kenneth Pitt, introduced by Horton, took over as Bowie's manager.[34] His April 1967 solo single, "The Laughing Gnome", on which speeded-up and high-pitched vocals were used to portray the gnome, failed to chart. Released six weeks later, his album debut, David Bowie, an amalgam of pop, psychedelia and music hall, met the same fate. It was his last release for two years.[35] In September, Bowie recorded "Let Me Sleep Beside You" and "Karma Man", both rejected by Deram and left unreleased until 1970. The tracks marked the beginning of Bowie's working relationship with producer Tony Visconti which, with large gaps, lasted for the rest of Bowie's career.[36][37]

1968–1971: Space Oddity to Hunky Dory

Studying the dramatic arts under Lindsay Kemp, from avant-garde theatre and mime to commedia dell'arte, Bowie became immersed in the creation of personae to present to the world. Satirising life in a British prison, his composition "Over the Wall We Go" became a 1967 single for Oscar; another Bowie song, "Silly Boy Blue", was released by Billy Fury the following year.[38] Playing acoustic guitar, Hermione Farthingale formed a group with Bowie and guitarist John Hutchinson named Feathers; between September 1968 and early 1969 the trio gave a small number of concerts combining folk, Merseybeat, poetry and mime.[39]

After the break-up with Farthingale, Bowie moved in with Mary Finnigan as her lodger.[40] In February and March 1969, he undertook a short tour with Marc Bolan's duo Tyrannosaurus Rex, as third on the bill, performing a mime act.[41] Continuing the divergence from rock and roll and blues begun by his work with Farthingale, Bowie joined forces with Finnigan, Christina Ostrom and Barrie Jackson to run a folk club on Sunday nights at the Three Tuns pub in Beckenham High Street.[40] The club was influenced by the Arts Lab movement, developing into the Beckenham Arts Lab and became extremely popular. The Arts Lab hosted a free festival in a local park, the subject of his song "Memory of a Free Festival".[42]

Pitt attempted to introduce Bowie to a larger audience with the Love You till Tuesday film, which went unreleased until 1984.[43] Feeling alienated over his unsuccessful career and deeply affected by his break-up, Bowie wrote "Space Oddity", a tale about a fictional astronaut named Major Tom.[44][45][46] The song earned him a contract with Mercury Records and its UK subsidiary Philips, who issued "Space Oddity" as a single on 11 July 1969, five days ahead of the Apollo 11 launch.[44] Reaching the top five in the UK,[47] it was his first and last hit for three years.[48] Bowie's second album followed in November. Originally issued in the UK as David Bowie, it caused some confusion with its predecessor of the same name, and the US release was instead titled Man of Words/Man of Music; it was reissued internationally in 1972 by RCA Records as Space Oddity. Featuring philosophical post-hippie lyrics on peace, love and morality, its acoustic folk rock occasionally fortified by harder rock, the album was not a commercial success at the time.[49][50][51]

Bowie met Angela Barnett in April 1969. They married within a year. Her impact on him was immediate—he wrote his 1970 single "The Prettiest Star" for her[52]—and her involvement in his career far-reaching, leaving Pitt with limited influence which he found frustrating.[49] Having established himself as a solo artist with "Space Oddity", Bowie desired a full-time band he could record with and could relate to personally.[53] The band Bowie assembled comprised John Cambridge, a drummer Bowie met at the Arts Lab, Visconti on bass and Mick Ronson on electric guitar. Known as Hype, the bandmates created characters for themselves and wore elaborate costumes that prefigured the glam style of the Spiders from Mars. After a disastrous opening gig at the London Roundhouse, they reverted to a configuration presenting Bowie as a solo artist.[53][54] Their initial studio work was marred by a heated disagreement between Bowie and Cambridge over the latter's drumming style, leading to his replacement by Mick Woodmansey.[55] Not long after, Bowie fired his manager and replaced him with Tony Defries. This resulted in years of litigation that concluded with Bowie having to pay Pitt compensation.[55]

The studio sessions continued and resulted in Bowie's third album, The Man Who Sold the World (1970), which contained references to schizophrenia, paranoia and delusion.[56] It represented a departure from the acoustic guitar and folk rock style established by his second album,[57] to a more hard rock sound.[58][59] Mercury financed a coast-to-coast publicity tour across the US in which Bowie, between January and February 1971, was interviewed by media. Exploiting his androgynous appearance, the original cover of the UK version unveiled two months later depicted Bowie wearing a dress. He took the dress with him and wore it during interviews, to the approval of critics – including Rolling Stone's John Mendelsohn, who described him as "ravishing, almost disconcertingly reminiscent of Lauren Bacall".[60][61]

During the tour, Bowie's observation of two seminal American proto-punk artists led him to develop a concept that eventually found form in the Ziggy Stardust character: a melding of the persona of Iggy Pop with the music of Lou Reed, producing "the ultimate pop idol".[60] A girlfriend recalled his "scrawling notes on a cocktail napkin about a crazy rock star named Iggy or Ziggy", and on his return to England he declared his intention to create a character "who looks like he's landed from Mars".[60] The "Stardust" surname was a tribute to the "Legendary Stardust Cowboy", whose record he was given during the tour. Bowie later covered "I Took a Trip on a Gemini Space Ship" on 2002's Heathen.[62]

Hunky Dory (1971) found Visconti supplanted in both roles by Ken Scott producing and Trevor Bolder on bass. It again featured a stylistic shift towards art pop and melodic pop rock,[63] with light fare tracks such as "Kooks", a song written for his son, Duncan Zowie Haywood Jones, born on 30 May.[64] Elsewhere, the album explored more serious subjects, and found Bowie paying unusually direct homage to his influences with "Song for Bob Dylan", "Andy Warhol" and "Queen Bitch", the latter a Velvet Underground pastiche.[65] His first release through RCA,[66] it was a commercial failure,[67] partly due lack of promotion from the label.[68] Peter Noone of Herman's Hermits covered the album's track "Oh! You Pretty Things", which reached number 12 in the UK.[69]

1972–1974: Glam rock era

Dressed in a striking costume, his hair dyed reddish-brown, Bowie launched his Ziggy Stardust stage show with the Spiders from Mars—Ronson, Bolder, and Woodmansey—at the Toby Jug pub in Tolworth in Kingston upon Thames on 10 February 1972.[70] The show was hugely popular, catapulting him to stardom as he toured the UK over the next six months and creating, as described by David Buckley, a "cult of Bowie" that was "unique—its influence lasted longer and has been more creative than perhaps almost any other force within pop fandom."[70] The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972), combining the hard rock elements of The Man Who Sold the World with the lighter experimental rock and pop of Hunky Dory, was released in June and was considered one of the defining albums of glam rock. "Starman", issued as an April single ahead of the album, was to cement Bowie's UK breakthrough: both single and album charted rapidly following his July Top of the Pops performance of the song. The album, which remained in the chart for two years, was soon joined there by the six-month-old Hunky Dory. At the same time, the non-album single "John, I'm Only Dancing" and "All the Young Dudes", a song he wrote and produced for Mott the Hoople,[71] were successful in the UK. The Ziggy Stardust Tour continued to the United States.[72]

Bowie contributed backing vocals, keyboards and guitar to Reed's 1972 solo breakthrough Transformer, co-producing the album with Ronson.[73] The following year, Bowie co-produced and mixed the Stooges' album Raw Power alongside Iggy Pop.[74] His own Aladdin Sane (1973) was his first UK number-one album. Described by Bowie as "Ziggy goes to America", it contained songs he wrote while travelling to and across the US during the earlier part of the Ziggy tour, which now continued to Japan to promote the new album. Aladdin Sane spawned the UK top five singles "The Jean Genie" and "Drive-In Saturday".[75][76]

Bowie's love of acting led to his total immersion in the characters he created for his music. "Offstage I'm a robot. Onstage I achieve emotion. It's probably why I prefer dressing up as Ziggy to being David." With satisfaction came severe personal difficulties: acting the same role over an extended period, it became impossible for him to separate Ziggy Stardust—and later, the Thin White Duke—from his own character offstage. Ziggy, Bowie said, "wouldn't leave me alone for years. That was when it all started to go sour ... My whole personality was affected. It became very dangerous. I really did have doubts about my sanity."[77] His later Ziggy shows, which included songs from both Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, were ultra-theatrical affairs filled with shocking stage moments, such as Bowie stripping down to a sumo wrestling loincloth or simulating oral sex with Ronson's guitar.[78] Bowie toured and gave press conferences as Ziggy before a dramatic and abrupt on-stage "retirement" at London's Hammersmith Odeon on 3 July 1973.[79] Footage from the final show was incorporated for the film Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, which premiered in 1979 and commercially released in 1983.[80]

After breaking up the Spiders, Bowie attempted to move on from his Ziggy persona. His back catalogue was now highly sought after: The Man Who Sold the World had been re-released in 1972 along with Space Oddity. Hunky Dory's "Life on Mars?" was released in June 1973 and peaked at number three on the UK Singles Chart. Entering the same chart in September, his 1967 novelty record "The Laughing Gnome" reached number six.[81] Pin Ups, a collection of covers of his 1960s favourites, followed in October, producing a UK number three hit in his version of the McCoys's "Sorrow" and itself peaking at number one, making Bowie the best-selling act of 1973 in the UK. It brought the total number of Bowie albums concurrently on the UK chart to six.[82]

1974–1976: "Plastic soul" and the Thin White Duke

Bowie moved to the US in 1974, initially staying in New York City before settling in Los Angeles.[83] Diamond Dogs (1974), parts of which found him heading towards soul and funk, was the product of two distinct ideas: a musical based on a wild future in a post-apocalyptic city, and setting George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four to music.[84] The album went to number one in the UK, spawning the hits "Rebel Rebel" and "Diamond Dogs", and number five in the US. The supporting Diamond Dogs Tour visited cities in North America between June and December 1974. Choreographed by Toni Basil, and lavishly produced with theatrical special effects, the high-budget stage production was filmed by Alan Yentob. The resulting documentary, Cracked Actor, featured a pasty and emaciated Bowie: the tour coincided with his slide from heavy cocaine use into addiction, producing severe physical debilitation, paranoia and emotional problems.[85] He later commented that the accompanying live album, David Live, ought to have been titled "David Bowie Is Alive and Well and Living Only in Theory".[86] David Live nevertheless solidified Bowie's status as a superstar, charting at number two in the UK and number eight in the US. It also spawned a UK number ten hit in a cover of Eddie Floyd's "Knock on Wood". After a break in Philadelphia, where Bowie recorded new material, the tour resumed with a new emphasis on soul.[87]

The fruit of the Philadelphia recording sessions was Young Americans (1975). Sandford writes, "Over the years, most British rockers had tried, one way or another, to become black-by-extension. Few had succeeded as Bowie did now."[88] The album's sound, which Bowie identified as "plastic soul", constituted a radical shift in style that initially alienated many of his UK devotees.[89] Young Americans was a commercial success in both the US and the UK and yielded Bowie's first US number one, "Fame", a collaboration with John Lennon.[90] A re-issue of the 1969 single "Space Oddity" became Bowie's first number-one hit in the UK a few months after "Fame" achieved the same in the US.[91] He mimed "Fame" and his November single "Golden Years" on the US variety show Soul Train, earning him the distinction of being one of the first white artists to appear on the programme.[92] The same year, Bowie fired Defries as his manager. At the culmination of the ensuing months-long legal dispute, he watched, as described by Sandford, "millions of dollars of his future earnings being surrendered" in what were "uniquely generous terms for Defries", then "shut himself up in West 20th Street, where for a week his howls could be heard through the locked attic door."[93] Michael Lippman, Bowie's lawyer during the negotiations, became his new manager; Lippman, in turn, was awarded substantial compensation when he was fired the following year.[94]

Station to Station (1976), produced by Bowie and Harry Maslin,[95] introduced a new Bowie persona, the Thin White Duke of its title track. Visually, the character was an extension of Thomas Jerome Newton, the extraterrestrial being he portrayed in the film The Man Who Fell to Earth the same year.[96] Developing the funk and soul of Young Americans, Station to Station's synthesiser-heavy arrangements were influenced by electronic and German krautrock.[97][95] Bowie's cocaine addiction during this period was at its peak; he often did not sleep for three to four days at a time during Station to Station's recording sessions and later said he remembered "only flashes" of its making.[98] His sanity—by his own later admission—had become twisted from cocaine;[85] he referenced the drug directly in the album's ten-minute title track.[99] The album's release was followed by a 3+1⁄2-month-long concert tour, the Isolar Tour, of Europe and North America. The core band that coalesced to record the album and tour—rhythm guitarist Carlos Alomar, bassist George Murray and drummer Dennis Davis—continued as a stable unit for the remainder of the 1970s. Bowie performed on stage as the Thin White Duke.[100][97]

The tour was highly successful but mired in political controversy. Bowie was quoted in Stockholm as saying that "Britain could benefit from a Fascist leader", and was detained by customs on the Russian/Polish border for possessing Nazi paraphernalia.[101] Matters came to a head in London in May in what became known as the "Victoria Station incident". Arriving in an open-top Mercedes convertible, Bowie waved to the crowd in a gesture that some alleged was a Nazi salute, which was captured on camera and published in NME. Bowie said the photographer caught him in mid-wave.[102] He later blamed his pro-fascism comments and his behaviour during the period on his cocaine addiction, the character of the Thin White Duke[103] and his life living in Los Angeles, a city he later said "should be wiped off the face of the Earth".[104] He later apologised for these statements, and throughout the 1980s and 1990s criticised racism in European politics and the American music industry.[105] Nevertheless, his comments on fascism, as well as Eric Clapton's alcohol-fuelled denunciations of Pakistani immigrants in 1976, led to the establishment of Rock Against Racism.[106]

1976–1979: Berlin era

In August 1976, Bowie moved to West Berlin with his old friend Iggy Pop to rid themselves of their respective drug addictions and escape the spotlight.[107][108][109] Bowie's interest in German krautrock and the ambient works of multi-instrumentalist Brian Eno culminated in the first of three albums, co-produced with Visconti, that became known as the Berlin Trilogy.[110][111] The album, Low (1977), was recorded in France and took influence from krautrock and experimental music and featured both short song-fragments and ambient instrumentals.[112][113] Before its recording, Bowie produced Iggy Pop's debut solo album The Idiot, described by Pegg as "a stepping stone between Station to Station and Low".[114] Low was completed in November, but left unreleased for three months. RCA did not see the album as commercially viable and was expecting another success following Young Americans and Station to Station.[115][116] Bowie's former manager Tony Defries, who maintained a significant financial interest in Bowie's affairs, had tried to prevent the album from being released.[107] Upon its release in January 1977, Low yielded the UK number three single "Sound and Vision", and its own performance surpassed that of Station to Station in the UK chart, where it reached number two.[117] Bowie himself did not promote it,[107] instead touring with Pop as his keyboardist throughout March and April before recording Pop's follow-up, Lust for Life.[118]

Echoing Low's minimalist, instrumental approach, the second of the trilogy, "Heroes" (1977), incorporated pop and rock to a greater extent, seeing Bowie joined by guitarist Robert Fripp.[119] It was the only album recorded entirely in Berlin.[120] Incorporating ambient sounds from a variety of sources including white noise generators, synthesisers and koto, the album was another hit, reaching number three in the UK. Its title track was released in both German and French and, though only reached number 24 in the UK singles chart, later became one of his best-known tracks.[121] In contrast to Low,[122] Bowie promoted "Heroes" extensively, performing the title track on Marc Bolan's television show Marc, and again two days later for Bing Crosby's final CBS television Christmas special, when he joined Crosby in "Peace on Earth/Little Drummer Boy", a version of "The Little Drummer Boy" with a new, contrapuntal verse.[123] RCA belatedly released the recording as a single five years later in 1982, charting in the UK at number three.[118][124]

After completing Low and "Heroes", Bowie spent much of 1978 on the Isolar II world tour, bringing the music of the first two Berlin Trilogy albums to almost a million people during 70 concerts in 12 countries. By now he had broken his drug addiction; Buckley writes that Isolar II was "Bowie's first tour for five years in which he had probably not anaesthetised himself with copious quantities of cocaine before taking the stage. ... Without the oblivion that drugs had brought, he was now in a healthy enough mental condition to want to make friends."[125] Recordings from the tour made up the live album Stage, released the same year.[126] Bowie also recorded narration for an adaptation of Sergei Prokofiev's classical composition Peter and the Wolf, which was released as an album in May 1978.[127][128]

The final piece in what Bowie called his "triptych", Lodger (1979), eschewed the minimalist, ambient nature of its two predecessors, making a partial return to the drum- and guitar-based rock and pop of his pre-Berlin era. The result was a complex mixture of new wave and world music, in places incorporating Hijaz non-Western scales. Some tracks were composed using Eno's Oblique Strategies cards: "Boys Keep Swinging" entailed band members swapping instruments, "Move On" used the chords from Bowie's early composition "All the Young Dudes" played backwards, and "Red Money" took backing tracks from The Idiot's "Sister Midnight".[129][130] The album was recorded in Switzerland and New York City.[131] Ahead of its release, RCA's Mel Ilberman described it as "a concept album that portrays the Lodger as a homeless wanderer, shunned and victimized by life's pressures and technology." Lodger reached number four in the UK and number 20 in the US, and yielded the UK hit singles "Boys Keep Swinging" and "DJ".[132][133] Towards the end of the year, Bowie and Angie initiated divorce proceedings, and after months of court battles the marriage was ended in early 1980.[134] The three albums were later adapted into classical music symphonies by American composer Philip Glass for his first, fourth and twelfth symphonies in 1992, 1997 and 2019, respectively.[135][136] Glass praised Bowie's gift for creating "fairly complex pieces of music, masquerading as simple pieces".[137]

1980–1988: New Romantic and pop era

Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980) produced the number one single "Ashes to Ashes", featuring the textural guitar-synthesiser work of Chuck Hammer and revisiting the character of Major Tom from "Space Oddity". The song gave international exposure to the underground New Romantic movement when Bowie visited the London club "Blitz"—the main New Romantic hangout—to recruit several of the regulars (including Steve Strange of the band Visage) to act in the accompanying video, renowned as one of the most innovative of all time.[138] While Scary Monsters used principles established by the Berlin albums, it was considered by critics to be far more direct musically and lyrically. The album's hard rock edge included conspicuous guitar contributions from Fripp and Pete Townshend.[139] Topping the UK Albums Chart for the first time since Diamond Dogs,[140] Buckley writes that with Scary Monsters, Bowie achieved "the perfect balance" of creativity and mainstream success.[141]

Bowie paired with Queen in 1981 for a one-off single release, "Under Pressure". The duet was a hit, becoming Bowie's third UK number-one single.[142] Bowie was given the lead role in the BBC's 1982 televised adaptation of Bertolt Brecht's play Baal. Coinciding with its transmission, a five-track EP of songs from the play was released as Baal.[143] In March 1982, Bowie's title song for Paul Schrader's film Cat People was released as a single. A collaboration with Giorgio Moroder, it became a minor US hit and charted in the UK top 30.[144][145] The same year, he departed RCA, having grown increasingly dissatisfied with them,[146] and signed a new contract with EMI America Records for a reported $17 million.[147] His 1975 severance settlement with Defries also ended in September.[148]

Bowie reached his peak of popularity and commercial success in 1983 with Let's Dance.[149] Co-produced by Chic's Nile Rodgers, the album went platinum in both the UK and the US. Its three singles became top 20 hits in both countries, where its title track reached number one. "Modern Love" and "China Girl" each made number two in the UK, accompanied by a pair of "absorbing" music videos that Buckley said "activated key archetypes in the pop world... 'Let's Dance', with its little narrative surrounding the young Aboriginal couple, targeted 'youth', and 'China Girl', with its bare-bummed (and later partially censored) beach lovemaking scene... was sufficiently sexually provocative to guarantee heavy rotation on MTV".[150] Then-unknown Texas blues guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan guested on the album, featuring prominently on the title track.[151][152] Let's Dance was followed by the six-month Serious Moonlight Tour, which was extremely successful.[153] At the 1984 MTV Video Music Awards Bowie received two awards including the inaugural Video Vanguard Award.[154]

Tonight (1984), another dance-oriented album, found Bowie collaborating with Pop and Tina Turner. Co-produced by Hugh Padgham, it included a number of cover songs, including three Pop covers and the 1966 Beach Boys hit "God Only Knows".[155] The album bore the transatlantic top 10 hit "Blue Jean", itself the inspiration for the Julien Temple-directed short film Jazzin' for Blue Jean, in which Bowie played the dual roles of romantic protagonist Vic and arrogant rock star Screaming Lord Byron.[156] The short won Bowie his only non-posthumous Grammy Award for Best Short Form Music Video.[157] In early 1985, Bowie's collaboration with the Pat Metheny Group, "This Is Not America", for the soundtrack of The Falcon and the Snowman, was released as a single and became a top 40 hit in the UK and US.[158] In July that year, Bowie performed at Wembley Stadium for Live Aid, a multi-venue benefit concert for Ethiopian famine relief.[159] Bowie and Mick Jagger duetted on a cover of Martha and the Vandellas' "Dancing in the Street" as a fundraising single, which went to number one in the UK and number seven in the US; its video premiered during Live Aid.

Bowie took an acting role in the 1986 film Absolute Beginners, and his title song rose to number two in the UK charts. He also worked with composer Trevor Jones and wrote five original songs for the 1986 film Labyrinth, which he starred in.[155] His final solo album of the decade was 1987's Never Let Me Down, where he ditched the light sound of his previous two albums, instead combining pop rock with a harder rock sound.[160][161] Peaking at number six in the UK, the album yielded the hits "Day-In Day-Out", "Time Will Crawl" and "Never Let Me Down". Bowie later described it as his "nadir", calling it "an awful album".[162] He supported the album on the 86-concert Glass Spider Tour.[163] The backing band included Peter Frampton on lead guitar. Contemporary critics maligned the tour as overproduced, saying it pandered to the current stadium rock trends in its special effects and dancing,[164] although in later years critics acknowledged the tour's strengths and influence on concert tours by other artists, such as Prince, Madonna and U2.[163][165]

1989–1991: Tin Machine

Wanting to completely rejuvenate himself following the critical failures of Tonight and Never Let Me Down,[166] Bowie placed his solo career on hold after meeting guitarist Reeves Gabrels and formed the hard rock quartet Tin Machine. The line-up was completed by bassist and drummer Tony and Hunt Sales, who had played with Bowie on Iggy Pop's Lust for Life in 1977.[167][168] Although he intended Tin Machine to operate as a democracy, Bowie dominated, both in songwriting and in decision-making.[169] The band's 1989 self-titled debut album received mixed reviews and,[170] according to author Paul Trynka, was quickly dismissed as "pompous, dogmatic and dull".[171] EMI complained of "lyrics that preach" as well as "repetitive tunes" and "minimalist or no production".[172] It reached number three in the UK and was supported by a twelve-date tour.[173][174]

The tour was a commercial success, but there was growing reluctance—among fans and critics alike—to accept Bowie's presentation as merely a band member.[175] A series of Tin Machine singles failed to chart, and Bowie, after a disagreement with EMI, left the label. Like his audience and his critics, Bowie himself became increasingly disaffected with his role as just one member of a band.[176] Tin Machine began work on a second album, but recording halted while Bowie conducted the seven-month Sound+Vision Tour, which brought him commercial success and acclaim.[177][178]

In October 1990, Bowie and Somali-born supermodel Iman were introduced by a mutual friend. He recalled, "I was naming the children the night we met ... it was absolutely immediate." They married in 1992.[179] Tin Machine resumed work the same month, but their audience and critics, ultimately left disappointed by the first album, showed little interest in a second.[180] Tin Machine II (1991) was Bowie's first album to miss the UK top 20 in nearly twenty years,[181] and was controversial for its cover art. Depicting four ancient nude Kouroi statues, the new record label, Victory, deemed the cover "a show of wrong, obscene images" and airbrushed the statues' genitalia for the American release.[178][180] Tin Machine toured again, but after the live album Tin Machine Live: Oy Vey, Baby (1992) failed commercially, Bowie dissolved the band and resumed his solo career.[182] He continued to collaborate with Gabrels for the rest of the 1990s.[168]

1992–1998: Electronic period

On 20 April 1992, Bowie appeared at The Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert, following the Queen singer's death the previous year. As well as performing "'Heroes'" and "All the Young Dudes", he was joined on "Under Pressure" by Annie Lennox, who took Mercury's vocal part; during his appearance, Bowie knelt and recited the Lord's Prayer at Wembley Stadium.[183][184] Four days later, Bowie and Iman married in Switzerland. Intending to move to Los Angeles, they flew in to search for a suitable property, but found themselves confined to their hotel, under curfew: the 1992 Los Angeles riots began the day they arrived. They settled in New York instead.[185]

In 1993, Bowie released his first solo offering since his Tin Machine departure, the soul, jazz and hip-hop influenced Black Tie White Noise.[186] Making prominent use of electronic instruments, the album, which reunited Bowie with Let's Dance producer Nile Rodgers, confirmed Bowie's return to popularity, topping the UK chart and spawning three top 40 hits, including the top 10 single "Jump They Say".[187] Bowie explored new directions on The Buddha of Suburbia (1993), which began as a soundtrack album for the BBC television adaptation of Hanif Kureishi's novel The Buddha of Suburbia before turning into a full album; only the title track "The Buddha of Suburbia" was used in the programme.[188][189][190] Referencing his 1970s works with pop, jazz, ambient and experimental material,[188][191][192] it received a low-key release, had almost no promotion and flopped commercially, reaching number 87 in the UK.[189] Nevertheless, it later received critical praise as Bowie's "lost great album".[191][193]

Reuniting Bowie with Eno, the quasi-industrial Outside (1995) was originally conceived as the first volume in a non-linear narrative of art and murder. Featuring characters from a short story written by Bowie, the album achieved UK and US chart success and yielded three top 40 UK singles.[194] In a move that provoked mixed reactions from both fans and critics, Bowie chose Nine Inch Nails as his tour partner for the Outside Tour. Visiting cities in Europe and North America between September 1995 and February 1996, the tour saw the return of Gabrels as Bowie's guitarist.[195] On 7 January 1997, Bowie celebrated his half century with a 50th birthday concert at Madison Square Garden at which he was joined in playing his songs and those of his guests, Lou Reed, Dave Grohl and the Foo Fighters, Robert Smith of the Cure, Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins, Black Francis of the Pixies, and Sonic Youth.[196]

Incorporating experiments in jungle and drum 'n' bass, Earthling (1997) was a critical and commercial success in the UK and the US, and two singles from the album—"Little Wonder" and "Dead Man Walking"—became UK top 40 hits.[197] The song "I'm Afraid of Americans" from the Paul Verhoeven film Showgirls was re-recorded for the album, and remixed by Trent Reznor for a single release. The heavy rotation of the accompanying video, also featuring Reznor, contributed to the song's 16-week stay in the US Billboard Hot 100.[198] Bowie received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on 12 February 1997.[199] The Earthling Tour took place in Europe and North America between June and November.[200] In November, Bowie performed on the BBC's Children in Need charity single "Perfect Day", which reached number one in the UK.[201] Bowie reunited with Visconti in 1998 to record "(Safe in This) Sky Life" for The Rugrats Movie. Although the track was edited out of the final cut, it was later re-recorded and released as "Safe" on the B-side of Bowie's 2002 single "Everyone Says 'Hi'".[202] The reunion led to other collaborations with his old producer, including a limited-edition single release version of Placebo's track "Without You I'm Nothing" with Bowie's harmonised vocal added to the original recording.[203]

1999–2012: Neoclassicist era

Bowie, with Gabrels, created the soundtrack for Omikron: The Nomad Soul, a 1999 computer game in which he and Iman also voiced characters based on their likenesses. Released the same year and containing re-recorded tracks from Omikron, his album Hours featured a song with lyrics by the winner of his "Cyber Song Contest" Internet competition, Alex Grant.[204] Making extensive use of live instruments, the album was Bowie's exit from heavy electronica.[205] Hours and a performance on VH1 Storytellers in mid-1999 represented the end of Gabrels' association with Bowie as a performer and songwriter.[206] Sessions for Toy, a planned collection of remakes of tracks from Bowie's 1960s period, commenced in 2000, but was shelved due to EMI/Virgin's lack of faith in its commercial appeal.[207] Bowie and Visconti continued their collaboration, producing a new album of completely original songs instead: the result of the sessions was the 2002 album Heathen.[208]

On 25 June 2000, Bowie made his second appearance at the Glastonbury Festival in England, playing almost 30 years after his first.[a][210] The performance was released as a live album in November 2018.[211] On 27 June, he performed a concert at the BBC Radio Theatre in London, which was released on the compilation album Bowie at the Beeb; this also featured BBC recording sessions from 1968 to 1972.[212] Bowie and Iman's daughter, Alexandra, was born on 15 August.[213] His interest in Buddhism led him to support the Tibetan cause by performing at the February 2001 and February 2003 concerts to support Tibet House US at Carnegie Hall in New York.[214][215][216]

In October 2001, Bowie opened the Concert for New York City, a charity event to benefit the victims of the September 11 attacks, with a minimalist performance of Simon & Garfunkel's "America", followed by a full band performance of "'Heroes'".[217] 2002 saw the release of Heathen, and, during the second half of the year, the Heathen Tour. Taking place in Europe and North America, the tour opened at London's annual Meltdown festival, for which Bowie was that year appointed artistic director. Among the acts he selected for the festival were Philip Glass, Television and the Dandy Warhols. As well as songs from the new album, the tour featured material from Bowie's Low era.[218] Reality (2003) followed, and its accompanying world tour, the A Reality Tour, with an estimated attendance of 722,000, grossed more than any other in 2004. On 13 June, Bowie headlined the last night of the Isle of Wight Festival 2004.[219] On 25 June, he experienced chest pain while performing at the Hurricane Festival in Scheeßel, Germany. Originally thought to be a pinched nerve in his shoulder, the pain was later diagnosed as an acutely blocked coronary artery, requiring an emergency angioplasty in Hamburg. The remaining fourteen dates of the tour were cancelled.[220]

In the years following his recuperation from the heart attack, Bowie reduced his musical output, making only one-off appearances on stage and in the studio. He sang in a duet of his 1971 song "Changes" with Butterfly Boucher for the 2004 animated film Shrek 2.[221] During a relatively quiet 2005, he recorded the vocals for the song "(She Can) Do That", co-written with Brian Transeau, for the film Stealth.[222] He returned to the stage on 8 September 2005, appearing with Arcade Fire for the US nationally televised event Fashion Rocks, and performed with the Canadian band for the second time a week later during the CMJ Music Marathon.[223] He contributed backing vocals on TV on the Radio's song "Province" for their album Return to Cookie Mountain, and joined with Lou Reed on Danish alt-rockers Kashmir's 2005 album No Balance Palace.[219]

Bowie was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award on 8 February 2006.[224] In April, he announced, "I'm taking a year off—no touring, no albums."[225] He made a surprise guest appearance at David Gilmour's 29 May concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London.[219] The event was recorded, and a selection of songs on which he had contributed joint vocals were subsequently released. He performed again in November, alongside Alicia Keys, at the Black Ball, a benefit event for Keep a Child Alive at the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York. The performance marked the last time Bowie performed his music on stage.[226]

Bowie was chosen to curate the 2007 High Line Festival. The musicians and artists he selected for the Manhattan event included electronic pop duo AIR, surrealist photographer Claude Cahun and English comedian Ricky Gervais.[227][228] Bowie performed on Scarlett Johansson's 2008 album of Tom Waits covers, Anywhere I Lay My Head.[219] In June 2008, a live album was released of a Ziggy Stardust-era concert from 1972.[229] On the 40th anniversary of the July 1969 Moon landing—and Bowie's accompanying commercial breakthrough with "Space Oddity"—EMI released the individual tracks from the original eight-track studio recording of the song, in a 2009 contest inviting members of the public to create a remix.[230] A live album from the A Reality Tour was released in January 2010.[231]

In late March 2011, Toy, Bowie's previously unreleased album from 2001, was leaked onto the internet, containing material used for Heathen and most of its single B-sides, as well as unheard new versions of his early back catalogue.[232][233]

2013–2016: Final years

On 8 January 2013, his 66th birthday, his website announced a new studio album—his first in a decade—to be titled The Next Day and scheduled for release in March;[234] the announcement was accompanied by the immediate release of the single "Where Are We Now?".[235] A music video for the single was released onto Vimeo the same day, directed by New York artist Tony Oursler.[235] The single topped the UK iTunes Chart within hours of its release,[236] and debuted in the UK Singles Chart at number six,[237] his first single to enter the Top 10 for two decades (since "Jump They Say" in 1993). A second single and video, "The Stars (Are Out Tonight)", were released at the end of February. Directed by Floria Sigismondi, it stars Bowie and Tilda Swinton as a married couple.[238]

Recorded in secret between 2011 and 2012, 29 songs were recorded during the album's sessions, of which 22 saw official release in 2013, including fourteen on the standard album. Three bonus tracks were later packaged with seven outtakes and remixes on The Next Day Extra, released in November.[239] On 1 March, the album was made available to stream for free through iTunes.[240] Debuting at number one on the UK Albums Chart, The Next Day was his first album to top the chart since Black Tie White Noise, and was the fastest-selling album of 2013 at the time.[241] The music video for the song "The Next Day" created some controversy due to its Christian themes and messages,[242] initially being removed from YouTube for terms-of-service violation, then restored with a warning recommending viewing only by those 18 or over.[243] According to The Times, Bowie ruled out ever giving an interview again.[244] Later in 2013, he was featured in a cameo vocal in the Arcade Fire song "Reflektor".[245] A poll carried out by BBC History Magazine in October 2013 named Bowie as the best-dressed Briton in history.[246] The success of The Next Day saw Bowie become the oldest ever recipient of a Brit Award when he won the award for British Male Solo Artist at the 2014 Brit Awards, which was collected on his behalf by Kate Moss.[247]

In mid-2014, Bowie was diagnosed with liver cancer, which he kept private.[248] A new compilation album, Nothing Has Changed, was released in November. The album featured rare tracks and old material from his catalogue in addition to a new song, "Sue (Or in a Season of Crime)".[249] Bowie continued working throughout 2015, secretly recording his final album Blackstar in New York between January and May.[250] In August, it was announced that he was writing songs for a Broadway musical based on the SpongeBob SquarePants cartoon series; the final production included a retooled version of "No Control" from Outside.[251][252] He also wrote and recorded the opening title song to the television series The Last Panthers, which aired in November.[253] The theme that was used for The Last Panthers was also the title track for Blackstar.[254] On 7 December, Bowie's musical Lazarus debuted in New York; he made his final public appearance at its opening night.[255]

Blackstar was released on 8 January 2016, Bowie's 69th birthday, and was met with critical acclaim.[256] He died two days later, after which Visconti revealed that Bowie had planned the album to be his swan song, and a "parting gift" for his fans before his death.[257] Several reporters and critics subsequently noted that most of the lyrics on the album seem to revolve around his impending death,[258] with CNN noting that the album "reveals a man who appears to be grappling with his own mortality".[259] Visconti also said that he had been planning a follow-up album, and had written and recorded demos of five songs in his final weeks, suggesting he believed he had a few months left.[260] The day following his death, online viewing of Bowie's music skyrocketed, breaking the record for Vevo's most viewed artist in a single day.[261] Blackstar debuted at number one on the UK Albums Chart; nineteen of his albums were in the UK Top 100 Albums Chart, and thirteen singles were in the UK Top 100 Singles Chart.[262][263] Blackstar also debuted at number one on album charts around the world, including Australia, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand and the US Billboard 200.[264][265]

Posthumous releases

In September 2016, a box set Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) was released covering Bowie's mid-1970s soul period; it included The Gouster, a previously unreleased 1974 album that evolved into Young Americans.[266] An EP, No Plan, was released on 8 January 2017, which would have been Bowie's 70th birthday.[267] Apart from "Lazarus", the EP includes three songs that Bowie recorded during the Blackstar sessions, but were left off the album and appeared on the soundtrack album for the Lazarus musical in October 2016.[268] A music video for the title track was also released.[268] 2017 and 2018 also saw the release of a series of posthumous live albums, Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles '74), Live Nassau Coliseum '76 and Welcome to the Blackout (Live London '78).[269][270][271] In the two years following his death, Bowie sold five million records in the UK alone.[272] In their top 10 list for the Global Recording Artist of the Year, the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry named Bowie the second-bestselling artist worldwide in 2016, behind Drake.[273]

At the 59th Annual Grammy Awards in 2017, Bowie won all five nominated awards: Best Rock Performance; Best Alternative Music Album; Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical; Best Recording Package; and Best Rock Song. They were Bowie's first Grammy wins in musical categories.[274] On 8 January 2020, on what would have been Bowie's 73rd birthday, a previously unreleased version of "The Man Who Sold the World" was released and two releases were announced: a streaming-only EP, Is It Any Wonder?, and an album, ChangesNowBowie, released in November 2020 for Record Store Day.[275] In August, another series of live shows were released, including sets from Dallas in 1995 and Paris in 1999.[276] These and other shows, part of a series of live concerts spanning his tours from 1995 to 1999, was released in late 2020 and early 2021 as part of the box set Brilliant Live Adventures.[277] In September 2021, Bowie's estate signed a distribution deal with Warner Music Group, beginning in 2023, covering Bowie's recordings from 2000 through 2016.[278] Bowie's album Toy, recorded in 2000, was released on what would have been Bowie's 75th birthday.[279][280] On 3 January 2022, Variety reported that Bowie's estate had sold his publishing catalogue to Warner Chappell Music, "for a price upwards of $250 million".[281]

Acting career

In addition to music, Bowie took acting roles throughout his career, appearing in over 30 films, television shows and theatrical productions. His acting career was "productively selective", largely eschewing starring roles for cameos and supporting parts;[282][283] he once described his film career as "splashing in the kids' pool".[226] He mostly chose projects with arthouse directors that he felt were outside the Hollywood mainstream, commenting in 2000: "One cameo for Scorsese to me brings so much more satisfaction than, say, a James Bond."[226] Critics have believed that, had he not chosen to pursue music, he could have found great success as an actor.[284][285] Others have felt that, while his screen presence was singular, his best contributions to film were the use of his songs in films such as Lost Highway, A Knight's Tale, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and Inglourious Basterds.[286][287]

1960s and 1970s

Bowie's acting career predated his commercial breakthrough as a musician. His first film was a short fourteen-minute black-and-white film called The Image, shot in September 1967. Concerning a ghostly boy who emerges from a troubled artist's painting to haunt him, Bowie later called the film "awful".[226][288] From December 1967 to March 1968, Bowie acted in mime Lindsay Kemp's theatrical production Pierrot in Turquoise, during which he performed several songs from his self-titled debut album. The production was later adapted into the 1970 television film The Looking Glass Murders.[226] In late January 1968, Bowie filmed a walk-on role for the BBC drama series Theatre 625 that aired in May.[289] He also appeared as a walk-on extra in the 1969 film adaptation of Leslie Thomas's 1966 comic novel The Virgin Soldiers.[288]

Bowie's first major film role was in Nicolas Roeg's The Man Who Fell to Earth, in which he portrayed Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien from a dying planet.[290] The actor's severe cocaine addiction at the time left him in such a fragile state of mind that he barely understood the film;[291] he later said in 1993: "My one snapshot of that film is not having to act. Just being me as I was, was perfectly adequate for the role. I wasn't of this earth at that particular time."[226] Bowie's role was particularly singled out for praise by film critics both on release and in later decades; Pegg argues it stands as Bowie's most significant role.[226] In 1978, Bowie had a starring role in Just a Gigolo, directed by David Hemmings, portraying Prussian officer Paul von Przygodski, who, returning from World War I, discovers life has changed and becomes a gigolo employed by a Baroness, playing by Marlene Dietrich.[292] The film was a critical and commercial failure, and Bowie expressed disappointment in the finished product.[293]

1980s

From July 1980 to January 1981, Bowie played Joseph Merrick in the Broadway theatre production The Elephant Man, which he undertook wearing no stage make-up, earning critical praise for his performance.[294][295] Christiane F., a 1981 biographical film focusing on a young girl's drug addiction in West Berlin, featured Bowie in a cameo appearance as himself at a concert in Germany. Its soundtrack album, Christiane F. (1981), featured much material from his Berlin albums.[296] The following year, he starred in the titular role in a BBC adaptation of the Bertolt Brecht play Baal.[297]

Bowie made three on-screen appearances in 1983, the first as a vampire in Tony Scott's erotic horror film The Hunger, with Catherine Deneuve and Susan Sarandon.[298] Bowie later said that he felt "very uncomfortable" with the role, but was happy to work with Scott.[299] The second was in Nagisa Ōshima's Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, based on Laurens van der Post's novel The Seed and the Sower, in which he played Major Jack Celliers, a prisoner of war in a Japanese internment camp.[300] While the film itself received mixed reviews, Bowie's performance was praised. Pegg places it among his finest acting performances.[301] Bowie's third role in 1983 was a small cameo in Mel Damski's pirate comedy Yellowbeard, heralded by several members of the Monty Python group.[302] Bowie also filmed a 30-second introduction to the animated film The Snowman, based on Raymond Briggs's book The Snowman.[302]

In 1985, Bowie had a supporting role as hitman Colin in John Landis's Into the Night.[303] He declined to play the villain Max Zorin in the James Bond film A View to a Kill (1985).[304] Bowie reteamed with Julian Temple for Absolute Beginners, a rock musical film adapted from Colin MacInnes's novel Absolute Beginners about life in late 1950s London, in a supporting role as ad man Vendice Partners.[305] The same year, Jim Henson's dark musical fantasy Labyrinth cast him as Jareth, the villainous Goblin King.[306] Despite initially performing poorly, the film grew in popularity and became a cult film.[307] Two years later, he played Pontius Pilate in Martin Scorsese's critically acclaimed biblical epic The Last Temptation of Christ (1988).[308] Despite only appearing for a three-minute sequence, Pegg writes that Bowie "acquits himself well with a thoughtful, unshowy performance."[226]

1990s

In 1991, Bowie reteamed with Landis for an episode of the HBO sitcom Dream On and played a disgruntled restaurant employee opposite Rosanna Arquette in The Linguini Incident.[309][310] Bowie portrayed the mysterious FBI agent Phillip Jeffries in David Lynch's Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992). The prequel to the television series was poorly received at the time of its release, but has since been critically reevaluated.[311] He took a small but pivotal role as his friend Andy Warhol in Basquiat, artist/director Julian Schnabel's 1996 biopic of Jean-Michel Basquiat, another artist he considered a friend and colleague.[226] Bowie co-starred in Giovanni Veronesi's Spaghetti Western Il Mio West (1998, released as Gunslinger's Revenge in the US in 2005) as the most feared gunfighter in the region.[312] He played the ageing gangster Bernie in Andrew Goth's Everybody Loves Sunshine (1999, released in the US as B.U.S.T.E.D.),[313] and appeared as the host in the second season of the television horror anthology series The Hunger. Despite having several episodes which focus on vampires and Bowie's involvement, the show had no plot connection to the 1983 film The Hunger.[314] In 1999, Bowie voiced two characters in the Dreamcast game Omikron: The Nomad Soul, his only appearance in a video game.[315]

2000s and posthumous notes

In Mr. Rice's Secret (2000), Bowie played the title role as the neighbour of a terminally ill 12-year-old boy.[316] Bowie appeared as himself in the 2001 Ben Stiller comedy Zoolander, judging a "walk-off" between rival male models,[317] and in Eric Idle's 2002 mockumentary The Rutles 2: Can't Buy Me Lunch.[318] In 2005, he filmed a commercial with Snoop Dogg for XM Satellite Radio.[319] Bowie portrayed a fictionalised version of the inventor Nikola Tesla in Christopher Nolan's film The Prestige (2006), which was about the bitter rivalry between two magicians in the late 19th century. Nolan later claimed that Bowie was his only preference to play Tesla, and that he personally appealed to Bowie to take the role after he initially passed.[320] In the same year, he voice-acted in Luc Besson's animated film Arthur and the Invisibles as the powerful villain Maltazard,[226] and appeared as himself in an episode of the Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant television series Extras.[321] In 2007, he voiced the character Lord Royal Highness in the SpongeBob's Atlantis SquarePantis television film.[322] In the 2008 film August, directed by Austin Chick, he played a supporting role as Ogilvie, a "ruthless venture capitalist."[323] Bowie's final film appearance was a cameo as himself in the 2009 teen comedy Bandslam.[324]

In a 2017 interview with Consequence of Sound, the director Denis Villeneuve revealed his intention to cast Bowie in Blade Runner 2049 as the main villain but following his death, Villeneuve was forced to look for talent with similar "rock star" qualities, eventually casting the actor and singer Jared Leto. Talking about the casting process, Villeneuve said: "Our first thought [for the character] had been David Bowie, who had influenced Blade Runner in many ways. When we learned the sad news, we looked around for someone like that. He [Bowie] embodied the Blade Runner spirit."[325] David Lynch also hoped to have Bowie reprise his Fire Walk With Me character for Twin Peaks: The Return but Bowie's illness prevented this. His character was portrayed via archival footage. At Bowie's request, Lynch overdubbed Bowie's original dialogue with a different actor's voice, as Bowie was unhappy with his Cajun accent in the original film.[326]

Other works

Painter and art collector

Bowie was a painter and artist. He moved to Switzerland in 1976, purchasing a chalet in the hills north of Lake Geneva. In the new environment, his cocaine use decreased,[327] and he devoted more time to his painting, producing a number of post-modernist pieces. When on tour, he took to sketching in a notebook, and photographing scenes for later reference. Visiting galleries in Geneva and the Brücke Museum in Berlin, Bowie became, in the words of Sandford, "a prolific producer and collector of contemporary art. ... Not only did he become a well-known patron of expressionist art: locked in Clos des Mésanges he began an intensive self-improvement course in classical music and literature, and started work on an autobiography."[328]

One of Bowie's paintings sold at auction in late 1990 for $500,[329] and the cover for his 1995 album Outside is a close-up of a self-portrait he painted that year.[330] His first solo show, titled New Afro/Pagan and Work: 1975–1995, was in 1995 at The Gallery in Cork Street, London.[331] In 1997, he founded the publishing company 21 Publishing, whose first title was Blimey! – From Bohemia to Britpop: London Art World from Francis Bacon to Damien Hirst by Matthew Collings.[330] A year later, Bowie was invited to join the editorial board of the journal Modern Painters,[332] and participated in the Nat Tate art hoax later that year.[330] The same year, during an interview with Michael Kimmelman for The New York Times, he said "Art was, seriously, the only thing I'd ever wanted to own."[333] Subsequently, in a 1999 interview for the BBC, he said "The only thing I buy obsessively and addictively is art".[334] His art collection, which included works by Damien Hirst, Derek Boshier, Frank Auerbach, Henry Moore, and Jean-Michel Basquiat among others, was valued at over £10 million in mid-2016.[332][335]

After his death, his family decided to sell most of the collection because they "didn't have the space" to store it.[332] On 10 and 11 November, three auctions were held at Sotheby's in London.[336] The items on sale represented about 65 per cent of the collection.[337] Exhibition of the works in the auction attracted 51,470 visitors, the auction itself was attended by 1,750 bidders, with over 1,000 more bidding online. The auctions has overall sale total £32.9 million (app. $41.5 million), while the highest-selling item, Basquiat's graffiti-inspired painting Air Power, sold for £7.09 million.[336][338]

Writings

Outside of music, Bowie dabbled in several forms of writings during his life. In the late 1990s, Bowie was commissioned for writings of various media, including an essay on Jean-Michel Basquiat for the 2001 anthology book Writers on Artists and forewords to Jo Levin's 2001 publication GQ Cool, Mick Rock's 2001 photography portfolio Blood and Glitter, his wife Iman's 2001 book I Am Iman, Q magazine's 2002 special The 100 Greatest Rock 'n' Roll Photographs and Jonathan Barnbrook's artwork portfolio Barnbrook Bible: The Graphic Design of Jonathan Barnbrook.[330] He also heavily contributed to the 2002 Genesis Publications memoir of the Ziggy Stardust years, Moonage Daydream, which was rereleased in 2022.[339]

Bowie also wrote liner notes for several albums, including Too Many Fish in the Sea by Robin Clark, the wife of his guitarist Carlos Alomar, Stevie Ray Vaughan's posthumous Live at Montreux 1982 & 1985 (2002), the Spinners' compilation The Chrome Collection (2003), the tenth anniversary reissue of Placebo's debut album (2006) and Neu!'s Vinyl Box (2010).[330] Bowie also wrote an appreciation piece in Rolling Stone for Nine Inch Nails in 2005 and an essay for the booklet accompanying Iggy Pop's A Million in Prizes: The Anthology the same year.[330]

Bowie Bonds

"Bowie Bonds", the first modern example of celebrity bonds, were asset-backed securities of current and future revenues of the 25 albums that Bowie recorded before 1990.[340] Issued in 1997, the bonds were bought for US$55 million by the Prudential Insurance Company of America.[341][342] Royalties from the 25 albums generated the cash flow that secured the bonds' interest payments.[343] By forfeiting 10 years worth of royalties, Bowie received a payment of US$55 million up front. Bowie used this income to buy songs owned by Defries.[344] The bonds liquidated in 2007 and the rights to the income from the songs reverted to Bowie.[345]

Websites

Bowie launched two personal websites during his lifetime. The first, an Internet service provider titled BowieNet, was developed in conjunction with Robert Goodale and Ron Roy and launched in September 1998.[346][347] Subscribers to the dial-up service were offered exclusive content as well as a BowieNet email address and Internet access. The service was closed by 2006.[346] The second, www.bowieart.com, allowed fans to view and purchase selected paintings, prints and sculptures from his private collection. The service, which ran from 2000 to 2008, also offered a showcase for young art students, in Bowie's words, "to show and sell their work without having to go through a dealer. Therefore, they really make the money they deserve for their paintings."[330]

Philanthropy

Bowie was involved in philanthropic and charitable efforts for HIV/AIDS research in Africa, as well as other humanitarian projects helping disadvantaged children and developing nations, ending poverty and hunger, promoting human rights, and providing education and health care to children affected by war.[348] A portion of the proceeds from the Pay-per-view showing of Bowie's 50th birthday concert in 1997 was donated to Save the Children.[349]

Musicianship

From the time of his earliest recordings in the 1960s, Bowie employed a wide variety of musical styles. His early compositions and performances were strongly influenced by rock and roll singers like Little Richard and Elvis Presley, and also the wider world of show business. He particularly strove to emulate the British musical theatre singer-songwriter and actor Anthony Newley, whose vocal style he frequently adopted, and made prominent use of for his 1967 debut release, David Bowie (to the disgust of Newley himself, who destroyed the copy he received from Bowie's publisher).[35][350] Bowie's fascination with music hall continued to surface sporadically alongside such diverse styles as hard rock and heavy metal, soul, psychedelic folk and pop.[351]

The musicologist James E. Perone observes Bowie's use of octave switches for different repetitions of the same melody, exemplified in "Space Oddity", and later in "'Heroes'" to dramatic effect; the author writes that "in the lowest part of his vocal register ... his voice has an almost crooner-like richness".[352] The voice instructor Jo Thompson describes Bowie's vocal vibrato technique as "particularly deliberate and distinctive".[353] The authors Scott Schinder and Andy Schwartz call him "a vocalist of extraordinary technical ability, able to pitch his singing to particular effect."[354] Here, too, as in his stagecraft and songwriting, Bowie's roleplaying is evident: the historiographer Michael Campbell says that Bowie's lyrics "arrest our ear, without question. But Bowie continually shifts from person to person as he delivers them ... His voice changes dramatically from section to section."[355] In addition to the guitar, Bowie also played a variety of keyboards, including piano, Mellotron, Chamberlin, and synthesisers; harmonica; alto and baritone saxophones; stylophone; viola; cello; koto (on the "Heroes" track "Moss Garden"); thumb piano; drums (on the Heathen track "Cactus"), and various percussion instruments.[356][357][358][359]

Personal life

Family

Bowie married his first wife, Mary Angela Barnett, on 19 March 1970 at Bromley Register Office in Bromley, London.[360] Their son Duncan, born on 30 May 1971, was at first known as Zowie.[361] Angie later described her and David's union as a marriage of convenience. "We got married so that I could [get a permit to] work. I didn't think it would last and David said, before we got married, 'I'm not really in love with you' and I thought that's probably a good thing," she said. Bowie said about Angie that "living with her is like living with a blow torch".[360] The couple divorced on 8 February 1980;[362] David received custody of Duncan. After the gag order that was part of their divorce agreement ended, Angie wrote a memoir of their turbulent marriage, titled Backstage Passes: Life on the Wild Side with David Bowie.[363]

David met Somali-American model Iman in Los Angeles following the Sound+Vision Tour in October 1990.[179] They married in a private ceremony in Lausanne on 24 April 1992. The wedding was solemnised on 6 June in Florence.[364] The couple's marriage influenced the content of Black Tie White Noise, particularly on tracks such as "The Wedding"/"The Wedding Song" and "Miracle Goodnight".[365] They had one daughter, Alexandria "Lexi" Zahra Jones, born on 15 August 2000.[207][366] The couple resided primarily in New York City and London as well as owning an apartment in Sydney's Elizabeth Bay[367][368] and Britannia Bay House on the island of Mustique.[369] Following Bowie's death, Iman expressed gratitude that the two were able to maintain separate identities during their marriage.[370]

Other relationships

Bowie began a personal and professional relationship with the singer Dana Gillespie in 1964 when he was 17 and she was 14.[371][372] Their relationship lasted a decade; Bowie wrote the song "Andy Warhol" for her, Gillespie sang backing vocals on Ziggy Stardust, and Bowie and Mick Ronson produced her 1973 album Weren't Born a Man. Bowie ended contact with Gillespie following his split from Angie. Gillespie looked back on her time with Bowie fondly.[373]

Bowie met the dancer Lindsay Kemp in 1967 and enrolled in his dance class at the London Dance Centre.[374] He commented in 1972 that meeting Kemp was when his interest in image "really blossomed":[374] "He lived on his emotions, he was a wonderful influence. His day-to-day life was the most theatrical thing I had ever seen, ever. It was everything I thought Bohemia probably was. I joined the circus."[375] In January 1968, Kemp choreographed a dance scene for a BBC play, The Pistol Shot, and used Bowie with a dancer, Hermione Farthingale;[376] the pair began dating and moved into a London flat together. Bowie and Farthingale broke up in early 1969 when she went to Norway to take part in a film, Song of Norway;[377] this affected him, and several songs, such as "Letter to Hermione" and "An Occasional Dream", reference her;[378] and, for the video accompanying "Where Are We Now?", he wore a T-shirt with the words "m/s Song of Norway".[379] Bowie blamed himself for their break-up, saying in 2002 that he "was totally unfaithful and couldn't for the life of me keep it zipped".[378] Farthingale, who spoke of deep affection for him in an interview with Pegg, said they last saw each other in 1970.[378]

David and Angie had an open marriage and dated other people during it: David had relationships with the models Cyrinda Foxe, Lulu,[380] Bebe Buell and the Young Americans backing singer Ava Cherry;[381][382][383] Angie had encounters with the Stooges' members Ron Asheton and James Williamson, and the Ziggy Stardust Tour bodyguard Anton Jones.[384]

In 1983, Bowie briefly dated the New Zealand model Geeling Ng, who starred in the video for "China Girl".[385] While filming The Hunger the same year, Bowie had a sexual relationship with his co-star Susan Sarandon, who stated in 2014 "He's worth idolising. He's extraordinary."[386] Between 1987 and 1990, Bowie dated the Glass Spider Tour dancer Melissa Hurley. The two began their relationship at the end of the tour when she was 22 years old. Bowie's Tin Machine collaborator Kevin Armstrong remembered her as "a genuinely kind, sweet person".[387] She inspired the song "Amazing" on Tin Machine (1989).[388] They announced their engagement in May 1989 but never married; Bowie broke the relationship off during the latter half of the Sound+Vision Tour, primarily due to the age difference—he was 43 at the time. He later spoke of Hurley as "such a wonderful, lovely, vibrant girl".[163][387]

Coco Schwab

Corinne "Coco" Schwab was Bowie's personal assistant for 43 years, from 1973 until his death in 2016. Originally a receptionist at the London office of MainMan, Schwab assisted in extracting Bowie from MainMan's financial grip, after which he invited her to be his personal assistant.[389][390] Bowie referred to Schwab as his best friend and credited her for saving his life in the 1970s by helping him quit his drug addiction;[390] he dedicated the 1987 song "Never Let Me Down" to her.[391] Schwab maintained close guard of him and did not get along with Angie, who later blamed Schwab for the downfall of her and Bowie's marriage.[390] Bowie left $2 million to Schwab in his will. Upon his death, friends of Bowie, including Tony Zanetta and Robin Clark, offered tributes to Schwab.[390]

Sexuality

Bowie's sexuality has been the subject of debate.[392][393] While married to Angie,[394] he famously declared himself gay in a 1972 interview with Melody Maker journalist Michael Watts,[395] which generated publicity in both America and Britain;[396] Bowie was adopted as a gay icon in both countries.[397] According to Buckley, "If Ziggy confused both his creator and his audience, a big part of that confusion centred on the topic of sexuality."[398] He affirmed his stance in a 1976 interview with Playboy, stating: "It's true—I am a bisexual. But I can't deny that I've used that fact very well. I suppose it's the best thing that ever happened to me."[399] His claim of bisexuality has been supported by Angie.[400]