Tianeptine: Difference between revisions

→Recreational use: remove incorrect information, fix some grammar, add some info |

m →Recreational use: spelling |

||

| Line 265: | Line 265: | ||

===Recreational use=== |

===Recreational use=== |

||

As a |

As a μ-opioid agonist, tianeptine in large doses has high abuse potential. In 2001, [[Singapore]]'s Ministry of Health restricted tianeptine prescribing to psychiatrists due to its recreational potential,<ref>{{cite web|author=World Health Organization| year=2001 | title=Pharmaceuticals: Restrictions in use and availability, March 2001|url=https://www.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s2203e/s2203e.pdf | access-date=24 July 2008 }}</ref> |

||

In 2003, [[Bahrain]] classified it a controlled substance due to increasing reports of misuse and recreational use.<ref>{{cite web| author=World Health Organization| year=2003| title=Pharmaceuticals: Restrictions in use and availability, April 2003| url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/EDM_QSM_2003.5.pdf| access-date=24 July 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629182215/http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/EDM_QSM_2003.5.pdf| archive-date=29 June 2011| url-status=dead| df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

In 2003, [[Bahrain]] classified it a controlled substance due to increasing reports of misuse and recreational use.<ref>{{cite web| author=World Health Organization| year=2003| title=Pharmaceuticals: Restrictions in use and availability, April 2003| url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/EDM_QSM_2003.5.pdf| access-date=24 July 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629182215/http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/EDM_QSM_2003.5.pdf| archive-date=29 June 2011| url-status=dead| df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:53, 19 November 2021

| |

| File:Tianeptine molecule ball.png | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Stablon, Coaxil, others |

| Other names | S-1574;[1][2][3] JNJ-39823277; TPI-1062[4] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 99%[6][7] |

| Protein binding | 95%[7] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic[7] |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5–3 hours[6][7] 4–9 hours (elderly)[7][8] |

| Excretion | Urine: 65%[6] Feces: 15%[7] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.131.750 100.069.844, 100.131.750 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

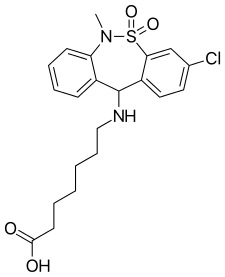

| Formula | C21H25ClN2O4S |

| Molar mass | 436.95 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Tianeptine, sold under the brand names Stablon and Coaxil among others, is an atypical antidepressant which is used mainly in the treatment of major depressive disorder, although it may also be used to treat anxiety, asthma, and irritable bowel syndrome.[1][2][3]

Tianeptine has antidepressant and anxiolytic effects[9] with a relative lack of sedative, anticholinergic, and cardiovascular side effects.[7][10] It has been found to act as an atypical agonist of the μ-opioid receptor with clinically negligible effects on the δ- and κ-opioid receptors.[11][12][13]

Tianeptine was discovered and patented by the French Society of Medical Research in the 1960s. Currently, tianeptine is approved in France and manufactured and marketed by Laboratories Servier SA; it is also marketed in a number of other European countries under the trade name Coaxil as well as in Asia (including Singapore) and Latin America as Stablon and Tatinol but it is not available in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, or the United States.[14][15]

Medical uses

Depression and anxiety

Tianeptine shows efficacy against serious depressive episodes (major depression), comparable to amitriptyline, imipramine and fluoxetine, but with significantly fewer side effects.[14] It was shown to be more effective than maprotiline in a group of people with co-existing depression and anxiety.[7] Tianeptine also displays significant anxiolytic properties and is useful in treating a spectrum of anxiety disorders including panic disorder, as evidenced by a study in which those administered 35% CO2 gas (carbogen) on paroxetine or tianeptine therapy showed equivalent panic-blocking effects.[16] Like many antidepressants (including bupropion, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, moclobemide and numerous others) it may also have a beneficial effect on cognition in people with depression-induced cognitive dysfunction.[17] A 2005 study in Egypt showed tianeptine to be effective in men with depression and erectile dysfunction.[18]

Tianeptine has been found to be effective in depression, in people with Parkinson's disease,[19] and with post-traumatic stress disorder[20] for which it was as safe and effective as fluoxetine and moclobemide.[21]

Other uses

A clinical trial comparing its efficacy and tolerability with amitriptyline in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome showed that tianeptine was at least as effective as amitriptyline and produced fewer prominent adverse effects, such as dry mouth and constipation.[22]

Tianeptine has been reported to be very effective for asthma. In August 1998, Dr. Fuad Lechin and colleagues at the Central University of Venezuela Institute of Experimental Medicine in Caracas published the results of a 52-week randomized controlled trial of asthmatic children; the children in the groups who received tianeptine had a sharp decrease in clinical rating and increased lung function.[23] Two years earlier, they had found a close, positive association between free serotonin in plasma and severity of asthma in symptomatic persons.[23] As tianeptine was the only agent known to both reduce free serotonin in plasma and enhance uptake in platelets, they decided to use it to see if reducing free serotonin levels in plasma would help.[23] By November 2004, there had been two double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trials and an under-25,000 person open-label study lasting over seven years, both showing effectiveness.[23]

Tianeptine also has anticonvulsant and analgesic effects,[24] and a clinical trial in Spain that ended in January 2007 has shown that tianeptine is effective in treating pain due to fibromyalgia.[25] Tianeptine has been shown to have efficacy with minimal side effects in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.[26]

Contraindications

Known contraindications include the following:[27]

- Hypersensitivity to tianeptine or any of the tablet's excipients.

Side effects

Compared to other tricyclic antidepressants it produces significantly fewer cardiovascular, anticholinergic (like dry mouth or constipation), sedative and appetite-stimulating effects.[10][14] A recent review found that it was amongst the antidepressants most prone to causing hepatotoxicity (liver damage), although the evidence to support this concern was of limited quality.[28][29] Unlike other tricyclic antidepressants, tianeptine does not affect heart function.[30] μ-Opioid receptor agonists can sometimes induce euphoria, as does tianeptine, occasionally, at high doses, well above the normal therapeutic range. Tianeptine can also cause severe withdrawal symptoms after prolonged use at high doses which should prompt extreme caution.[31][better source needed]

By frequency

- Common (>1% frequency)

- Headache (up to 18%)

- Dizziness (up to 10%)

- Insomnia/nightmares (up to 20%)

- Drowsiness (up to 10%)

- Dry mouth (up to 20%)

- Constipation (up to 15%)

- Nausea

- Abdominal pain

- Weight gain (~3%)

- Agitation

- Anxiety/irritability

- Uncommon (0.1-1% frequency)

- Bitter taste

- Flatulence

- Gastralgia

- Blurred vision

- Muscle aches

- Premature ventricular contractions

- Micturition disturbances

- Palpitations

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Hot flushes

- Tremor

- Rare (<0.1% frequency)

- Hepatitis

- Hypomania[33]

- Euphoria

- ECG changes

- Pruritus/allergic-type skin reactions

- Protracted muscle aches

- General fatigue

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | 383–768 (Ki) 194 (EC50) |

Human | [11][34] [11] |

| DOR | >10,000 (Ki) 37,400 (EC50) |

Human | [11][34] [11] |

| KOR | >10,000 (Ki) 100,000 (EC50) |

Human | [11][34] [11] |

| SERT | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| NET | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| DAT | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT1A | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT1B | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT1D | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT1E | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT2A | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT2B | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT2C | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT5A | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT6 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| 5-HT7 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| α1A | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| α1B | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| α2A | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| α2B | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| α2C | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| β1 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| β2 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| D1 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| D2 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| D3 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| D4 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| D5 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| H1 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| H2 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| H3 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| H4 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| mACh | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| σ1 | >10,000 | Guinea pig | [34] |

| σ2 | >10,000 | Rat | [34] |

| I1 | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| A1 | >10,000 (EC50) | Human | [11] |

| VDCC | >10,000 | Human | [34] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug interacts with the site. | |||

Atypical μ-opioid receptor agonist

In 2014, tianeptine was found to be a μ-opioid receptor (MOR) full agonist using human proteins.[11] It was also found to act as a full agonist of the δ-opioid receptor (DOR), although with approximately 200-fold lower potency.[11] The same researchers subsequently found that the MOR is required for the acute and chronic antidepressant-like behavioral effects of tianeptine in mice and that its primary metabolite had similar activity as a MOR agonist but with a much longer elimination half-life.[35] Moreover, although tianeptine produced other opioid-like behavioral effects such as analgesia and reward, it did not result in tolerance or withdrawal.[35] The authors suggested that tianeptine may be acting as a biased agonist of the MOR and that this may be responsible for its atypical profile as a MOR agonist.[35] However, there are reports that suggest that withdrawal effects resembling those of other typical opioid drugs (including but not limited to depression, insomnia, and cold/flu-like symptoms) do manifest following prolonged usage of dose usage far beyond the medical range.[36][37] In addition to its therapeutic effects, activation of the MOR is likely to also be responsible for the abuse potential of tianeptine at high doses that are well above the normal therapeutic range and efficacy threshold.

When co-administered with morphine, tianeptine prevents morphine-induced respiratory depression without impairing analgesia.[38]

Glutamatergic, neurotrophic, and neuroplastic modulation

Research suggests that tianeptine produces its antidepressant effects through indirect alteration and inhibition of glutamate receptor activity (i.e., AMPA receptors and NMDA receptors) and release of BDNF, in turn affecting neural plasticity.[39][40][41][42][10][14] Some researchers hypothesize that tianeptine has a protective effect against stress induced neuronal remodeling.[39][10] There is also action on the NMDA and AMPA receptors.[39][10] In animal models, tianeptine inhibits the pathological stress-induced changes in glutamatergic neurotransmission in the amygdala and hippocampus. It may also facilitate signal transduction at the CA3 commissural associational synapse by altering the phosphorylation state of glutamate receptors. With the discovery of the rapid and novel antidepressant effects of drugs such as ketamine, many believe the efficacy of antidepressants is related to promotion of synaptic plasticity. This may be achieved by regulating the excitatory amino acid systems that are responsible for changes in the strength of synaptic connections as well as enhancing BDNF expression, although these findings are based largely on preclinical studies.[14]

Serotonin reuptake enhancer

Tianeptine is no longer labelled a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Enhancer (SSRE) antidepressant.[39][40][41][42][10][14] Tianeptine has been found to bind to the same allosteric site on the serotonin transporter (SERT) as conventional TCAs.[43] However, whereas conventional TCAs inhibit serotonin reuptake by the SERT, tianeptine appears to enhance it.[43] This seems to be because of the unique C3 amino heptanoic acid side chain of tianeptine, which, in contrast to other TCAs, is thought to lock the SERT in a conformation that increases affinity for and reuptake (Vmax) of serotonin.[43] As such, tianeptine acts as a positive allosteric modulator of the SERT, or as a "serotonin reuptake enhancer".[43]

Although tianeptine was originally found to have no effect in vitro on monoamine reuptake, release, or receptor binding, upon acute and repeated administration, tianeptine decreased the extracellular levels of serotonin in rat brain without a decrease in serotonin release, leading to a theory of tianeptine enhancing serotonin reuptake.[44] The (−)-enantiomer is more active in this sense than the (+)-enantiomer.[45] However, more recent studies found that long-term administration of tianeptine does not elicit any marked alterations (neither increases nor decreases) in extracellular levels of serotonin in rats.[39] However, coadministration of tianeptine and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine inhibited the effect of tianeptine on long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 area. This is considered an argument for the opposite effects of tianeptine and fluoxetine on serotonin uptake,[10] although it has been shown that fluoxetine can be partially substituted for tianeptine in animal studies.[46] In any case, the collective research suggests that direct modulation of the serotonin system is unlikely to be the mechanism of action underlying the antidepressant effects of tianeptine.[43]

Other actions

Tianeptine modestly enhances the mesolimbic release of dopamine[47] and potentiates CNS D2 and D3 receptors.[48] Tianeptine has no affinity for the dopamine transporter or the dopamine receptors.[39] CREB-TF (CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein)[49] is a cellular transcription factor. It binds to certain DNA sequences called cAMP response elements (CRE), thereby increasing or decreasing the transcription of the genes.[50] CREB has a well-documented role in neuronal plasticity and long-term memory formation in the brain. Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript, also known as CART, is an neuropeptide protein that in humans is encoded by the CARTPT gene.[51][52] CART appears to have roles in reward, feeding, stress,[53] and it has the functional properties of an endogenous psychostimulant.[54] Taking into account that CART production is upregulated by CREB,[55] it could be hypothesized that due to tianeptine's central role in BDNF and neuronal plasticity, this CREB may be the transcription cascade through which this drug enhances mesolimbic release of dopamine.

Research indicates possible anticonvulsant (anti-seizure) and analgesic (painkilling) activity of tianeptine via downstream modulation of adenosine A1 receptors (as the effects could be experimentally blocked by antagonists of this receptor).[24] Tianpetine is also weak histone deacetylase inhibitor and analogs with increased potency and selectivity are developed.[56]

Pharmacokinetics

The bioavailability of tianeptine is approximately 99%.[6][7] Its plasma protein binding is about 95%.[7] The metabolism of tianeptine is hepatic.[7] Its elimination half-life is 2.5 to 3 hours.[6][7] The elimination half-life has been found to be increased to 4 to 9 hours in the elderly.[8] The drug has an active metabolite, with a much longer elimination half-life[35] of approximately 7.6 hours, leading to a steady-state after about a week. Tianeptine is excreted 65% in the urine and 15% in feces.[6][7]

Chemistry

In terms of chemical structure, it is similar to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), but it has significantly different pharmacology and important structural differences, so it is not usually grouped with them.

Analogues

Although several related compounds are disclosed in the original patent,[57] no activity data are provided and it was unclear whether these share tianeptine's unique pharmacological effects. More recent structure-activity relationship studies have since been conducted, providing some further insight on μ-opioid, δ-opioid, and pharmacokinetical activity.[58][59] Derivatives where the aromatic chlorine substituent is replaced by bromine, iodine or methylthio, and/or the heptanoic acid tail is replaced with other groups such as 3-methoxypropyl, show similar or increased opioid receptor activity relative to tianeptine itself.[60] Amineptine, the most closely related drug to have been widely studied, is a dopamine reuptake inhibitor with no significant effect on serotonin levels, nor opioid agonist activity. Tianeptinaline, analog of tianeptine, is a notable class I HDAC inhbitor.[56]

Society and culture

Approval and brand names

Brand names include:

- Coaxil (BG, CZ, EE, HU, LT, LV, PL, RO, RU, UA)

- Salymbra (EE)

- Stablon (AR, AT, BR, FR, IN, ID, MY, MX, PK, PT, SG, TH, TT, TR, VE)

- Tatinol (CN)

- Tianeurax (DE)

- Tynept (discontinued) (IN)

- Zinosal (ES)

Development

Under the code names JNJ-39823277 and TPI-1062, tianeptine was previously under development for the treatment of major depressive disorder in the United States and Belgium.[4] Phase I clinical trials were completed in Belgium and the United States in May and June 2009, respectively.[4] For unclear reasons development of tianeptine was discontinued in both countries in January 2012.[4]

The U.S. National Poison Data System data on tianeptine showed a nationwide increase in tianeptine exposure calls and calls related to abuse and misuse during 2014–2017.[13]

Recreational use

As a μ-opioid agonist, tianeptine in large doses has high abuse potential. In 2001, Singapore's Ministry of Health restricted tianeptine prescribing to psychiatrists due to its recreational potential,[61] In 2003, Bahrain classified it a controlled substance due to increasing reports of misuse and recreational use.[62]

Between 1989 and 2004, in France 141 cases of recreational use were identified, correlating to an incidence of 1 to 3 cases per 1000 persons treated with tianeptine and 45 between 2006 and 2011. According to Servier, stopping of treatment with tianeptine is difficult, due to the possibility of withdrawal symptoms in a person. The severity of the withdrawal is dependent on the daily dose, with high doses being extremely difficult to quit.[63][better source needed][64][65] Official DEA statement [66] states that the withdrawal symptoms in humans typically result in: agitation, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, hypertension, diarrhea, tremor, and diaphoresis, similar to other opioid drugs.

In 2007, according to French Health Products Safety Agency, tianeptine's manufacturer Servier agreed to modify the drug's label, following problems with dependency.[67]

Tianeptine has been intravenously injected by drug users in Russia.[68][69] This method of administration reportedly causes an opioid-like effect and is sometimes used in an attempt to lessen opioid withdrawal symptoms.[68] Tianeptine tablets contain silica and do not dissolve completely. Often the solution is not filtered well thus particles in the injected fluid block capillaries, leading to thrombosis and then severe necrosis. Thus, in Russia tianeptine (sold under the brand name “Coaxil”) is a schedule III controlled substance in the same list as the majority of benzodiazepines and barbiturates.[70]

On 6 April 2018 Michigan became the first U.S. state to ban tianeptine sodium, classifying it as a schedule II controlled substance.[71] The scheduling of tianeptine sodium is effective 4 July 2018.[72] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has expressed concern that tianeptine may be an "emerging public health risk", citing an increase in exposure-related calls to poison control centers in the United States.[13] Alabama is set to ban it on March 15, 2021.[73]

A literature review conducted in 2018 found 25 articles involving 65 patients with tianeptine abuse or dependence.[74] Limited data showed that a majority of patients were male and that age ranged from 19 to 67. Routes of intake included oral, intravenous, and insufflation entry. In the 15 cases of overdose, 8 combined ingestion with at least one other substance, of which 3 resulted in death. Six additional deaths are reported involving tianeptine (making it 9 in total). In this report, the amount of tianeptine used ranged from 50 mg/day to 10g/day orally.

On March 13, 2020, with a decree approved by the Minister of Health, Italy became the first European country to ban tianeptine considering it a Class I controlled substance.[75]

See also

References

- ^ a b Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 1195–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 1024–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ a b "Tianeptine".

- ^ a b c d "Tianeptine – AdisInsight". AdisInsight. Springer. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c d e f Royer RJ, Albin H, Barrucand D, Salvadori-Failler C, Kamoun A (1988). "Pharmacokinetic and metabolic parameters of tianeptine in healthy volunteers and in populations with risk factors". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 11 Suppl 2: S90-6. PMID 3180120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wagstaff AJ, Ormrod D, Spencer CM (March 2001). "Tianeptine: a review of its use in depressive disorders". CNS Drugs. 15 (3): 231–59. doi:10.2165/00023210-200115030-00006. PMID 11463130.

- ^ a b Carlhant D, Le Garrec J, Guedes Y, Salvadori C, Mottier D, Riche C (September 1990). "Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of tianeptine in the elderly". Drug Investigation. 2 (3): 167–172. doi:10.1007/BF03259191. S2CID 56502717.

- ^ Defrance R, Marey C, Kamoun A (1988). "Antidepressant and anxiolytic activities of tianeptine: an overview of clinical trials" (PDF). Clinical Neuropharmacology. 11 Suppl 2: S74-82. PMID 2902922. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kasper S, McEwen BS (2008). "Neurobiological and clinical effects of the antidepressant tianeptine". CNS Drugs. 22 (1): 15–26. doi:10.2165/00023210-200822010-00002. PMID 18072812. S2CID 30330824.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gassaway MM, Rives ML, Kruegel AC, Javitch JA, Sames D (July 2014). "The atypical antidepressant and neurorestorative agent tianeptine is a μ-opioid receptor agonist". Translational Psychiatry. 4 (7): e411. doi:10.1038/tp.2014.30. PMC 4119213. PMID 25026323.

- ^ Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML (August 2008). "Affective neuroscience of pleasure: reward in humans and animals". Psychopharmacology. 199 (3): 457–80. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1099-6. PMC 3004012. PMID 18311558.

- ^ a b c El Zahran T, Schier J, Glidden E, Kieszak S, Law R, Bottei E, et al. (August 2018). "Characteristics of Tianeptine Exposures Reported to the National Poison Data System - United States, 2000-2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 67 (30): 815–818. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6730a2. PMC 6072055. PMID 30070980.

- ^ a b c d e f Akiki T. "The etiology of depression and the therapeutic implications". Glob. J. Med. Res. 13 (6). ISSN 2249-4618.

- ^ Tianeptine Sodium. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Schruers K, Griez E (December 2004). "The effects of tianeptine or paroxetine on 35% CO2 provoked panic in panic disorder". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 18 (4): 553–8. doi:10.1177/0269881104047283. PMID 15582922. S2CID 26981110.

- ^ Baune BT, Renger L (September 2014). "Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive dysfunction and functional ability in clinical depression--a systematic review". Psychiatry Research. 219 (1): 25–50. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.013. PMID 24863864. S2CID 23684657.

- ^ El-Shafey H, Atteya A, Abu El-Magd S, Hassanein A, Fathy A, Shamloul R (September 2006). "Tianeptine can be effective in men with depression and erectile dysfunction". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 3 (5): 910–917. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00141.x. PMID 16942535.

- ^ Levin OS (May 2007). "Coaxil (tianeptine) in the treatment of depression in Parkinson's disease". Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology. 37 (4): 419–24. doi:10.1007/s11055-007-0029-0. PMID 17457538. S2CID 7637174.

- ^ Aleksandrovskiĭ I, Avedisova AS, Boev IV, Bukhanovkskiĭ AO, Voloshin VM, Tsygankov BD, Shamreĭ BK (2005). "[Efficacy and tolerability of coaxil (tianeptine) in the therapy of posttraumatic stress disorder]" Эффективность и переносимость коаксила (тианептина) при терапии посттравматического стрессового расстройства [Efficacy and tolerability of coaxil (tianeptine) in the therapy of posttraumatic stress disorder]. Zhurnal Nevrologii I Psikhiatrii Imeni S.S. Korsakova (in Russian). 105 (11): 24–9. PMID 16329631.

- ^ Onder E, Tural U, Aker T (April 2006). "A comparative study of fluoxetine, moclobemide, and tianeptine in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder following an earthquake". European Psychiatry. 21 (3): 174–9. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.03.007. PMID 15964747. S2CID 21322928.

- ^ Sohn W, Lee OY, Kwon JG, Park KS, Lim YJ, Kim TH, et al. (September 2012). "Tianeptine vs amitriptyline for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: a multicenter, open-label, non-inferiority, randomized controlled study". Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 24 (9): 860–e398. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01945.x. PMID 22679908. S2CID 2914428.

- ^ a b c d Lechin F, van der Dijs B, Lechin AE (November 2004). "Treatment of bronchial asthma with tianeptine". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 26 (9): 697–701. doi:10.1358/mf.2004.26.9.872567. PMID 15632955.

- ^ a b Uzbay TI (May 2008). "Tianeptine: potential influences on neuroplasticity and novel pharmacological effects". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 32 (4): 915–24. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.007. PMID 17826881. S2CID 22365299.

- ^ "ISRCTN16400909 – Tianeptine for the treatment of fibromyalgia: a prospective double-blind, randomised, single-centre, placebo-controlled, parallel group study". Controlled-trials.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ^ Niederhofer H (2004). "Tianeptine as a slightly effective therapeutic option for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Neuropsychobiology. 49 (3): 130–3. doi:10.1159/000076721. PMID 15034228. S2CID 34300575.

- ^ "Package Insert – Stablon (German)" (PDF). Servier Austria GmbH. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Voican CS, Corruble E, Naveau S, Perlemuter G (April 2014). "Antidepressant-induced liver injury: a review for clinicians". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 171 (4): 404–15. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13050709. PMID 24362450.

- ^ Billioti de Gage S, Collin C, Le-Tri T, Pariente A, Bégaud B, Verdoux H, et al. (July 2018). "Antidepressants and Hepatotoxicity: A Cohort Study among 5 Million Individuals Registered in the French National Health Insurance Database". CNS Drugs. 32 (7): 673–684. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0537-1. PMC 6061298. PMID 29959758.

- ^ Bril A, Abadie C, Ben Baouali A, Maupoil V, Rochette L (1993). "Absence of relationship between antiarrhythmic effects of antidepressant drugs and lipid peroxidation". Pharmacology. 46 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1159/000139025. PMID 8434029.

- ^ Vadachkoria D, Gabunia L, Gambashidze K, Pkhaladze N, Kuridze N (September 2009). "Addictive potential of Tianeptine - the threatening reality". Georgian Medical News (174): 92–4. PMID 19801742.

- ^ Waintraub L, Septien L, Azoulay P (January 2002). "Efficacy and safety of tianeptine in major depression: evidence from a 3-month controlled clinical trial versus paroxetine". CNS Drugs. 16 (1): 65–75. doi:10.2165/00023210-200216010-00005. PMID 11772119. S2CID 31125177.

- ^ Gülen Yıldırım S, Başterzi AD, Göka E (2004). "Tianeptinin Neden Olduğu Hipomani; Bir Olgu Sunumu" [Tianeptine Induced Mania: A Case Report] (PDF). Klinik Psikiyatri Dergisi (in Turkish). 7 (4): 177–180. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Samuels BA, Nautiyal KM, Kruegel AC, Levinstein MR, Magalong VM, Gassaway MM, et al. (September 2017). "The Behavioral Effects of the Antidepressant Tianeptine Require the Mu-Opioid Receptor". Neuropsychopharmacology. 42 (10): 2052–2063. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.60. PMC 5561344. PMID 28303899.

- ^ Springer J, Cubała WJ (March 2018). "Tianeptine Abuse and Dependence in Psychiatric Patients: A Review of 18 Case Reports in the Literature". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 50 (3): 275–280. doi:10.1080/02791072.2018.1438687. PMID 29494783. S2CID 3603781.

- ^ Marraffa JM, Stork CM, Hoffman RS, Su MK (November 2018). "Poison control center experience with tianeptine: an unregulated pharmaceutical product with potential for abuse". Clinical Toxicology. 56 (11): 1155–1158. doi:10.1080/15563650.2018.1476694. PMID 29799284. S2CID 44112801.

- ^ Cavalla D, Chianelli F, Korsak A, Hosford PS, Gourine AV, Marina N (August 2015). "Tianeptine prevents respiratory depression without affecting analgesic effect of opiates in conscious rats". European Journal of Pharmacology. 761: 268–72. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.067. PMID 26068549.

- ^ a b c d e f McEwen BS, Chattarji S, Diamond DM, Jay TM, Reagan LP, Svenningsson P, Fuchs E (March 2010). "The neurobiological properties of tianeptine (Stablon): from monoamine hypothesis to glutamatergic modulation". Molecular Psychiatry. 15 (3): 237–49. doi:10.1038/mp.2009.80. PMC 2902200. PMID 19704408.

- ^ a b McEwen BS, Chattarji S (December 2004). "Molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity and pharmacological implications: the example of tianeptine". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 14 Suppl 5: S497-502. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.09.008. PMID 15550348. S2CID 21953270.

- ^ a b McEwen BS, Olié JP (June 2005). "Neurobiology of mood, anxiety, and emotions as revealed by studies of a unique antidepressant: tianeptine". Molecular Psychiatry. 10 (6): 525–37. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001648. PMID 15753957.

- ^ a b Brink CB, Harvey BH, Brand L (January 2006). "Tianeptine: a novel atypical antidepressant that may provide new insights into the biomolecular basis of depression". Recent Patents on CNS Drug Discovery. 1 (1): 29–41. doi:10.2174/157488906775245327. PMID 18221189. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Bailey SJ, Almatroudi A, Kouris A (2018). "Tianeptine: An Atypical Antidepressant with Multimodal Pharmacology" (PDF). Current Psychopharmacology. 6 (2). doi:10.2174/2211556006666170525154616. ISSN 2211-5560.

- ^ Mennini T, Mocaer E, Garattini S (November 1987). "Tianeptine, a selective enhancer of serotonin uptake in rat brain". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 336 (5): 478–82. doi:10.1007/bf00169302. PMID 3437921. S2CID 21499462.

- ^ Oluyomi AO, Datla KP, Curzon G (March 1997). "Effects of the (+) and (-) enantiomers of the antidepressant drug tianeptine on 5-HTP-induced behaviour". Neuropharmacology. 36 (3): 383–7. doi:10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00016-6. PMID 9175617. S2CID 11465294.

- ^ Alici T, Kayir H, Aygoren MO, Saglam E, Uzbay IT (January 2006). "Discriminative stimulus properties of tianeptine". Psychopharmacology. 183 (4): 446–51. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0210-5. PMID 16292591. S2CID 5820336.

- ^ Invernizzi R, Pozzi L, Garattini S, Samanin R (March 1992). "Tianeptine increases the extracellular concentrations of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens by a serotonin-independent mechanism". Neuropharmacology. 31 (3): 221–7. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(92)90171-K. PMID 1630590. S2CID 21610131.

- ^ Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M, Rogoz Z, Skuza G, Dlaboga D, Maj J (March 2002). "Effect of repeated treatment with tianeptine and fluoxetine on central dopamine D(2) /D(3) receptors". Behavioural Pharmacology. 13 (2): 127–38. doi:10.1097/00008877-200203000-00004. PMID 11981225. S2CID 2126834.

- ^ Bourtchuladze R, Frenguelli B, Blendy J, Cioffi D, Schutz G, Silva AJ (October 1994). "Deficient long-term memory in mice with a targeted mutation of the cAMP-responsive element-binding protein". Cell. 79 (1): 59–68. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90400-6. PMID 7923378. S2CID 17250247.

- ^ Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Hall WC, LaMantia AS, McNamara JO, White LE (2008). Neuroscience (4th ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 170–6. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7.

- ^ Douglass J, Daoud S (March 1996). "Characterization of the human cDNA and genomic DNA encoding CART: a cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript". Gene. 169 (2): 241–5. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(96)88651-3. PMID 8647455.

- ^ Kristensen P, Judge ME, Thim L, Ribel U, Christjansen KN, Wulff BS, et al. (May 1998). "Hypothalamic CART is a new anorectic peptide regulated by leptin". Nature. 393 (6680): 72–6. Bibcode:1998Natur.393...72K. doi:10.1038/29993. PMID 9590691. S2CID 4427258.

- ^ Zhang M, Han L, Xu Y (June 2012). "Roles of cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript in the central nervous system". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 39 (6): 586–92. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05642.x. PMID 22077697. S2CID 25134612.

- ^ Kuhar MJ, Adams S, Dominguez G, Jaworski J, Balkan B (February 2002). "CART peptides". Neuropeptides. 36 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1054/npep.2002.0887. PMID 12147208. S2CID 7079530.

- ^ Rogge GA, Jones DC, Green T, Nestler E, Kuhar MJ (January 2009). "Regulation of CART peptide expression by CREB in the rat nucleus accumbens in vivo". Brain Research. 1251: 42–52. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.011. PMC 2734444. PMID 19046951.

- ^ a b Zhao WN, Ghosh B, Tyler M, Lalonde J, Joseph NF, Kosaric N, Fass DM, Tsai LH, Mazitschek R, Haggarty SJ (September 2018). "Class I Histone Deacetylase Inhibition by Tianeptinaline Modulates Neuroplasticity and Enhances Memory". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 9 (9): 2262–2273. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00116. hdl:1721.1/126372. PMID 29932631.

- ^ Charles Malen, Bernard Danrée, Jean-Claude Poignant. Nouveaux dérivés tricycliques et leur procédé de préparation. French Patent FR 2104728, 7 September 1971.

- ^ Kruegel, Andrew Carry (2015). Chemical and Biological Explorations of Novel Opioid Receptor Modulators (Thesis). Columbia University. p. 338-358. doi:10.7916/d8v1242f.

- ^ Labrid, C.; Moleyre, J.; Poignant, J. C.; Malen, C.; Mocaër, E.; Kamoun, A. (1988). "Structure-activity relationships of tricyclic antidepressants, with special reference to tianeptine". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 11 Suppl 2: S21–31. ISSN 0362-5664. PMID 3180115.

- ^ Kruegel AC. Chemical and Biological Explorations of Novel Opioid Receptor Modulators. PhD Thesis, Columbia University 2015 doi:10.7916/D8V1242F

- ^ World Health Organization (2001). "Pharmaceuticals: Restrictions in use and availability, March 2001" (PDF). Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ World Health Organization (2003). "Pharmaceuticals: Restrictions in use and availability, April 2003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ APM Health Europe (2007). "Addiction leads to warning on Servier's antidepressant Stablon". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ Gibaja V (2006). "Use, Drug Abuse and Tianeptine (in French)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ "Tianeptine (Stablon°) dans la dépression : Risque trop important de dépendance".

- ^ "Drug Enforcement AdministrationDiversion Control DivisionDrug & Chemical Evaluation Section - Tianeptine" (PDF).

- ^ French Health Products Safety Agency (Afssaps) (2007). "Important Information on Drug: Update of the Summary of Product Characteristics Stablon, 16 May 2007 (French)". Archived from the original on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ a b Ives R (2008). "Assessment Mission Report for the SCAD V Programme, Component on Prevention and on Media Work" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ^ "Illicit Drug Trades in the Russian Federation" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. April 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ Decision of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 681 of June 30, 1998 on the Approval of the List of Narcotic Drugs, Psychotropic Substances and Their Precursors That Shall Be Subject to Control in the Russian Federation (with Amendments and Additions) (in Russian)

- ^ Michigan approves ban on antidepressant tianeptine sodium

- ^ "Public Health Code Section 333.7214.amended". Michigan Legislature. Legislative Council, State of Michigan. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ Nunnally, Ben. "Tianeptine: 'Gas station dope' to be banned Monday in Alabama". Anniston Star. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Lauhan R, Hsu A, Alam A, Beizai K (November 2018). "Tianeptine Abuse and Dependence: Case Report and Literature Review". Psychosomatics. 59 (6): 547–553. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2018.07.006. PMID 30149933.

- ^ "Gazzetta Ufficiale".