Swastika

The swastika symbol, 卐 (right-facing or clockwise) or 卍 (left-facing, counterclockwise, or sauwastika), is an ancient religious icon in the cultures of Eurasia. It is used as a symbol of divinity and spirituality in Indian religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.[1][2][3]

In the Western world, it was a symbol of auspiciousness and good luck until the 1930s[4] when the right-facing tilted form became a feature of Nazi symbolism as an emblem of the Aryan race. As a result of World War II and the Holocaust, many people in the West still strongly associate it with Nazism and antisemitism.[5][6] The swastika continues to be used as a symbol of good luck and prosperity in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain countries throughout Asia, including Nepal, India, Mongolia, Indonesia (specifically Bali), Thailand, China, Korea, Singapore and Japan, among others. It is also commonly used in Buddhist and Hindu marriage ceremonies.

The word swastika comes from Template:Lang-sa, meaning "conducive to well-being".[7][8] In Hinduism, the right-facing symbol (卐) is called swastika, symbolizing surya ("sun"), prosperity and good luck, while the left-facing symbol (卍) is called sauwastika, symbolising night or tantric aspects of Kali.[8] In Jainism, a swastika is the symbol for Suparshvanatha – the seventh of 24 Tirthankaras (spiritual teachers and saviours), while in Buddhism it symbolises the auspicious footprints of the Buddha.[8][9][10] In several major Indo-European religions, the swastika symbolises lightning bolts, representing the thunder god and the king of the gods, such as Indra in Vedic Hinduism, Zeus in the ancient Greek religion, Jupiter in the ancient Roman religion, and Thor in the ancient Germanic religion.[11]

The swastika is an icon which is widely found in both human history and the modern world.[12][8] In various forms, it is otherwise known (in various European languages) as the fylfot, gammadion, tetraskelion, or cross cramponnée (a term in Anglo-Norman heraldry); German: Hakenkreuz; French: croix gammée; Italian: croce uncinata. In Mongolian it is called Хас (khas) and mainly used in seals. In Chinese it is called 卍字 (wànzì) meaning "all things symbol", pronounced manji in Japanese, manja (만자) in Korean and vạn tự / chữ vạn in Vietnamese. A swastika generally takes the form of a cross, the arms of which are of equal length and perpendicular to the adjacent arms, each bent midway at a right angle.[13][14] The symbol is found in the archeological remains of the Indus Valley Civilisation[15] and Samarra, as well as in early Byzantine and Christian artwork.[12]

The right-facing swastika (卐) was adopted by several organisations in pre-World War I Europe, and later by the Nazi Party and Nazi Germany before World War II. It was used by the Nazi Party to symbolise German nationalistic pride. To Jews and other victims and enemies of Nazi Germany, it became a symbol of antisemitism and terror.[5] In many Western countries, the swastika is now viewed as a symbol of racial supremacism and intimidation because of its association with Nazism.[6][16][17]

In Hindu and Buddhist cultures, the swastika is a holy symbol. On the holiday of Diwali, Hindu households commonly use the swastika in decorations. Many Indian auto-rickshaws feature the swastika to ward off ill-fortune. Reverence for the swastika symbol in Asian cultures, in contrast to the West's stigmatisation of the symbol, has led to misinterpretations and misunderstandings.[4][18]

Etymology and nomenclature

The word swastika is derived from the Sanskrit swasti, which is composed of Su (सु – good, well, auspicious) and Asti (अस्ति – "it is" or "there is"[19])

The word swastika has been used in the Indian subcontinent since 500 BCE. The word was first recorded by the ancient linguist Pāṇini in his work Ashtadhyayi.[20] It is alternatively spelled in contemporary texts as svastika,[21] and other spellings were occasionally used in the 19th and early 20th century, such as suastika.[22] It was derived from the Sanskrit term (Devanagari स्वस्तिक), which transliterates to svastika under the commonly used IAST transliteration system, but is pronounced closer to swastika when letters are used with their English values. An important early use of the word swastika in a European text was in 1871 with the publications of Heinrich Schliemann, who discovered more than 1,800 ancient samples of the swastika symbol and its variants while digging the Hisarlik mound near the Aegean Sea coast for the history of Troy. Schliemann linked his findings to the Sanskrit swastika.[16][23][24]

The word swasti occurs frequently in the Vedas as well as in classical literature, meaning "health, luck, success, prosperity", and it was commonly used as a greeting.[25][26] The final ka is a common suffix that could have multiple meanings.[27] According to Monier-Williams, a majority of scholars consider it a solar symbol.[25] The sign implies something fortunate, lucky, or auspicious, and it denotes auspiciousness or well-being.[25]

The earliest known use of the word swastika is in Panini's Ashtadhyayi, which uses it to explain one of the Sanskrit grammar rules, in the context of a type of identifying mark on a cow's ear.[19] Most scholarship suggests that Panini lived in or before the 4th century BCE,[28][29] possibly in 6th or 5th century BCE.[30][31]

By the 19th century, the term swastika was adopted into the English lexicon, replacing gammadion from Greek γαμμάδιον.[A]

The concept of a "reversed" swastika was probably first made among European scholars by Eugène Burnouf in 1852, and taken up by Schliemann in Ilios (1880), based on a letter from Max Müller that quotes Burnouf. The term sauwastika is used in the sense of "backwards swastika" by Eugène Goblet d'Alviella (1894): "In India it [the gammadion] bears the name of swastika, when its arms are bent towards the right, and sauwastika when they are turned in the other direction."[32]

Other names for the symbol include:

- tetragammadion (Greek: τετραγαμμάδιον) or cross gammadion (Template:Lang-la; French: croix gammée), as each arm resembles the Greek letter Γ (gamma)[13]

- hooked cross (Hakenkreuz), angled cross (Winkelkreuz), or crooked cross (Krummkreuz)

- cross cramponned, cramponnée, or cramponny in heraldry, as each arm resembles a crampon or angle-iron (German: Winkelmaßkreuz)

- fylfot, chiefly in heraldry and architecture

- tetraskelion (Greek: τετρασκέλιον), literally meaning 'four-legged', especially when composed of four conjoined legs (compare triskelion/triskele [Greek: τρισκέλιον])[33]

- whirling logs (Navajo, Native American): can denote abundance, prosperity, healing, and luck[34]

Appearance

All swastikas are bent crosses based on a chiral symmetry, but they appear with different geometric details: as compact crosses with short legs, as crosses with large arms and as motifs in a pattern of unbroken lines. Chirality describes an absence of reflective symmetry, with the existence of two versions that are mirror images of each other. The mirror-image forms are typically described as left-facing or left-hand (卍) and right-facing or right-hand (卐).

The compact swastika can be seen as a chiral irregular icosagon (20-sided polygon) with fourfold (90°) rotational symmetry. Such a swastika proportioned on a 5 × 5 square grid and with the broken portions of its legs shortened by one unit can tile the plane by translation alone. The Nazi swastika used a 5 × 5 diagonal grid, but with the legs unshortened.[37]

Written characters

The sauwastika was adopted as a standard character in Chinese, "卍" (pinyin: wàn) and as such entered various other East Asian languages, including Chinese script. In Japanese the symbol is called "卍" (Hepburn: manji) or "卍字" (manji).

The sauwastika is included in the Unicode character sets of two languages. In the Chinese block it is U+534D 卍 (left-facing) and U+5350 for the swastika 卐 (right-facing);[38] The latter has a mapping in the original Big5 character set,[39] but the former does not (although it is in Big5+[40]). In Unicode 5.2, two swastika symbols and two sauwastikas were added to the Tibetan block: swastika U+0FD5 ࿕ RIGHT-FACING SVASTI SIGN, U+0FD7 ࿗ RIGHT-FACING SVASTI SIGN WITH DOTS, and sauwastikas U+0FD6 ࿖ LEFT-FACING SVASTI SIGN, U+0FD8 ࿘ LEFT-FACING SVASTI SIGN WITH DOTS.[41]

Meaning

European hypotheses of the swastika are often treated in conjunction with cross symbols in general, such as the sun cross of Bronze Age religion. Beyond its certain presence in the "proto-writing" symbol systems, such as the Vinča script,[42] which appeared during the Neolithic.[43]

North pole

According to René Guénon, the swastika represents the north pole, and the rotational movement around a centre or immutable axis (axis mundi), and only secondly it represents the Sun as a reflected function of the north pole. As such it is a symbol of life, of the vivifying role of the supreme principle of the universe, the absolute God, in relation to the cosmic order. It represents the activity (the Hellenic Logos, the Hindu Om, the Chinese Taiyi, "Great One") of the principle of the universe in the formation of the world.[44] According to Guénon, the swastika in its polar value has the same meaning of the yin and yang symbol of the Chinese tradition, and of other traditional symbols of the working of the universe, including the letters Γ (gamma) and G, symbolising the Great Architect of the Universe of Freemasonic thought.[45]

According to the scholar Reza Assasi, the swastika represents the north ecliptic north pole centred in ζ Draconis, with the constellation Draco as one of its beams. He argues that this symbol was later attested as the four-horse chariot of Mithra in ancient Iranian culture. They believed the cosmos was pulled by four heavenly horses who revolved around a fixed centre in a clockwise direction. He suggests that this notion later flourished in Roman Mithraism, as the symbol appears in Mithraic iconography and astronomical representations.[46]

According to the Russian archaeologist Gennady Zdanovich, who studied some of the oldest examples of the symbol in Sintashta culture, the swastika symbolises the universe, representing the spinning constellations of the celestial north pole centred in α Ursae Minoris, specifically the Little and Big Dipper (or Chariots), or Ursa Minor and Ursa Major.[47] Likewise, according to René Guénon the swastika is drawn by visualising the Big Dipper/Great Bear in the four phases of revolution around the pole star.[48]

Comet

In his book Comet (1985), Carl Sagan reproduces a Han-dynasty Chinese manuscript (the Book of Silk, 2nd century BCE) that shows comet tail varieties: most are variations on simple comet tails, but the last shows the comet nucleus with four bent arms extending from it, recalling a swastika. Sagan suggests that in antiquity a comet could have approached so close to Earth that the jets of gas streaming from it, bent by the comet's rotation, became visible, leading to the adoption of the swastika as a symbol across the world.[49]

Bob Kobres in his 1992 paper Comets and the Bronze Age Collapse contends that the swastika-like comet on the Han-dynasty silk comet manuscript was labelled a "long tailed pheasant star" (dixing) because of its resemblance to a bird's foot or footprint,[50] the latter comparison also being drawn by J.F.K. Hewitt's observation on page 145 of Primitive Traditional History: vol. 1.[51] as well as an article concerning carpet decoration in Good Housekeeping.[52] Kobres goes on to suggest an association of mythological birds and comets also outside China.[50]

Four winds

In Native American culture, particularly among the Pima people of Arizona, the swastika is a symbol of the four winds. Anthropologist Frank Hamilton Cushing noted that among the Pima the symbol of the four winds is made from a cross with the four curved arms (similar to a broken sun cross), and concludes "the right-angle swastika is primarily a representation of the circle of the four wind gods standing at the head of their trails, or directions."[53]

Prehistory

The earliest known swastika is from 10,000 BCE – part of "an intricate meander pattern of joined-up swastikas" found on a late paleolithic figurine of a bird, carved from mammoth ivory, found in Mezine, Ukraine. It has been suggested that this swastika may be a stylised picture of a stork in flight.[54] As the carving was found near phallic objects, this may also support the idea that the pattern was a fertility symbol.[55]

In the mountains of Iran, there are swastikas or spinning wheels inscribed on stone walls, which are estimated to be more than 7,000 years old. One instance is in Khorashad, Birjand, on the holy wall Lakh Mazar.[56][57]

Mirror-image swastikas (clockwise and counter-clockwise) have been found on ceramic pottery in the Devetashka cave, Bulgaria, dated to 6,000 BCE.[58]

Some of the earliest archaeological evidence of the swastika in the Indian subcontinent can be dated to 3,000 BCE.[59] The investigators put forth the hypothesis that the swastika moved westward from India to Finland, Scandinavia, the Scottish Highlands and other parts of Europe.[60][better source needed] In England, neolithic or Bronze Age stone carvings of the symbol have been found on Ilkley Moor, such as the Swastika Stone.

Swastikas have also been found on pottery in archaeological digs in Africa, in the area of Kush and on pottery at the Jebel Barkal temples,[61] in Iron Age designs of the northern Caucasus (Koban culture), and in Neolithic China in the Majiabang[62] and Majiayao[63] cultures.

Other Iron Age attestations of the swastika can be associated with Indo-European cultures such as the Illyrians,[64] Indo-Iranians, Celts, Greeks, Germanic peoples and Slavs. In Sintashta culture's "Country of Towns", ancient Indo-European settlements in southern Russia, it has been found a great concentration of some of the oldest swastika patterns.[47]

The swastika is also seen in Egypt during the Coptic period. Textile number T.231-1923 held at the V&A Museum in London includes small swastikas in its design. This piece was found at Qau-el-Kebir, near Asyut, and is dated between CE 300 and 600.[65][66]

The Tierwirbel (the German for "animal whorl" or "whirl of animals"[67]) is a characteristic motif in Bronze Age Central Asia, the Eurasian Steppe, and later also in Iron Age Scythian and European (Baltic[68] and Germanic) culture, showing rotational symmetric arrangement of an animal motif, often four birds' heads. Even wider diffusion of this "Asiatic" theme has been proposed, to the Pacific and even North America (especially Moundville).[69]

-

Swastika seals from the Indus Valley Civilisation preserved at the British Museum

-

The Samarra bowl, at the Pergamonmuseum, Berlin. The swastika in the centre of the design is a reconstruction.[71]

Historical use

In Asia, the swastika symbol first appears in the archaeological record around[59] 3000 BCE in the Indus Valley Civilisation.[72][73] It also appears in the Bronze and Iron Age cultures around the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. In all these cultures, the swastika symbol does not appear to occupy any marked position or significance, appearing as just one form of a series of similar symbols of varying complexity. In the Zoroastrian religion of Persia, the swastika was a symbol of the revolving sun, infinity, or continuing creation.[74][75] It is one of the most common symbols on Mesopotamian coins.[8]

The icon has been of spiritual significance to Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.[12][8] The swastika is a sacred symbol in the Bön religion, native to Tibet.

Asia

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the swastika is considered to symbolise the auspicious footprints of the Buddha.[8][9] The left-facing sauwastika is often imprinted on the chest, feet or palms of Buddha images. It is an aniconic symbol for the Buddha in many parts of Asia and homologous with the dharma wheel.[2] The shape symbolises eternal cycling, a theme found in the samsara doctrine of Buddhism.[2]

The swastika symbol is common in esoteric tantric traditions of Buddhism, along with Hinduism, where it is found with chakra theories and other meditative aids.[76] The clockwise symbol is more common, and contrasts with the counter clockwise version common in the Tibetan Bon tradition and locally called yungdrung.[77]

When the Chinese writing system was introduced to Japan in the 8th century, the swastika was adopted into the Japanese language and culture. It is commonly referred as the manji (lit. "10,000-character"). Since the Middle Ages, it has been used as a mon by various Japanese families such as Tsugaru clan, Hachisuka clan or around sixty clans who belong to Tokugawa clan.[78] On Japanese maps, a swastika (left-facing and horizontal) is used to mark the location of a Buddhist temple. The right-facing swastika is often referred to as the gyaku manji (逆卍, lit. "reverse swastika") or migi manji (右卍, lit. "right swastika"), and can also be called kagi jūji (鉤十字, literally "hook cross").

In Chinese and Japanese art, the swastika is often found as part of a repeating pattern. One common pattern, called sayagata in Japanese, comprises left- and right-facing swastikas joined by lines.[79]

Hinduism

The swastika is an important Hindu symbol.[12][8] The swastika symbol is commonly used before entrances or on doorways of homes or temples, to mark the starting page of financial statements, and mandalas constructed for rituals such as weddings or welcoming a newborn.[8][76]

The swastika has a particular association with Diwali, being drawn in rangoli (coloured sand) or formed with deepak lights on the floor outside Hindu houses and on wall hangings and other decorations.[80]

In the diverse traditions within Hinduism, both the clockwise and counterclockwise swastika are found, with different meanings. The clockwise or right hand icon is called swastika, while the counterclockwise or left hand icon is called sauwastika or sauvastika.[8] The clockwise swastika is a solar symbol (Surya), suggesting the motion of the Sun in India (the northern hemisphere), where it appears to enter from the east, then ascend to the south at midday, exiting to the west.[8] The counterclockwise sauwastika is less used; it connotes the night, and in tantric traditions it is an icon for the goddess Kali, the terrifying form of Devi Durga.[8] The symbol also represents activity, karma, motion, wheel, and in some contexts the lotus.[1][2] According to Norman McClelland its symbolism for motion and the Sun may be from shared prehistoric cultural roots.[81]

A swastika shaped temple tank built in 800 CE by Kamban Araiyan during the reign of Dantivarman is outside the temple complex of Pundarikakshan Perumal Temple (Vishnu temple) in Thiruvallarai, Tiruchirappalli, India. It is one of the important monuments of Pallava dynasty.

Jainism

In Jainism, it is a symbol of the seventh tīrthaṅkara, Suparśvanātha.[8] In the Śvētāmbara tradition, it is also one of the aṣṭamaṅgala or eight auspicious symbols. All Jain temples and holy books must contain the swastika and ceremonies typically begin and end with creating a swastika mark several times with rice around the altar. Jains use rice to make a swastika in front of statues and then put an offering on it, usually a ripe or dried fruit, a sweet (Hindi: मिठाई miṭhāī), or a coin or currency note. The four arms of the swastika symbolise the four places where a soul could be reborn in samsara, the cycle of birth and death – svarga "heaven", naraka "hell", manushya "humanity" or tiryancha "as flora or fauna" – before the soul attains moksha "salvation" as a siddha, having ended the cycle of birth and death and become omniscient.[3]

The paired swastika symbols (卍 and 卐)) are included, at least since the Liao Dynasty (CE 907–1125), as part of the Chinese writing system and are variant characters for 萬 or 万 (wàn in Mandarin, 만 (man) in Korean, Cantonese, and Japanese, vạn in Vietnamese) meaning "myriad".[82]

Northern Europe

Sami

An object very much like a hammer or a double axe is depicted among the magical symbols on the drums of Sami shamans, used in their religious ceremonies before Christianity was established. The name of the Sami thunder god was Horagalles, thought to derive from "Old Man Thor" (Þórr karl). Sometimes on the drums, a male figure with a hammer-like object in either hand is shown, and sometimes it is more like a cross with crooked ends, or a swastika.[83]

Germanic Iron Age

The swastika shape (also called a fylfot) appears on various Germanic Migration Period and Viking Age artifacts, such as the 3rd-century Værløse Fibula from Zealand, Denmark, the Gothic spearhead from Brest-Litovsk, today in Belarus, the 9th-century Snoldelev Stone from Ramsø, Denmark, and numerous Migration Period bracteates drawn left-facing or right-facing.[84]

The pagan Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo, England, contained numerous items bearing the swastika, now housed in the collection of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.[83][failed verification] The swastika is clearly marked on a hilt and sword belt found at Bifrons in Kent, in a grave of about the 6th century.

Hilda Ellis Davidson theorised[clarification needed] that the swastika symbol was associated with Thor, possibly representing his Mjolnir – symbolic of thunder – and possibly being connected to the Bronze Age sun cross.[83] Davidson cites "many examples" of the swastika symbol from Anglo-Saxon graves of the pagan period, with particular prominence on cremation urns from the cemeteries of East Anglia.[83] Some of the swastikas on the items, on display at the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, are depicted with such care and art that, according to Davidson, it must have possessed special significance as a funerary symbol.[83] The runic inscription on the 8th-century Sæbø sword has been taken as evidence of the swastika as a symbol of Thor in Norse paganism.

Balto-Slavic

According to painter Stanisław Jakubowski the "little sun" (Polish słoneczko) is an Early Slavic pagan symbol of the Sun; he claimed it was engraved on wooden monuments built near the final resting places of fallen Slavs to represent eternal life. The symbol was first seen in his collection of Early Slavic symbols and architectural features, which he named Prasłowiańskie motywy architektoniczne (Template:Lang-pl). His work was published in 1923, by a publishing house that was then based in the Dębniki district of Kraków.[86]

In Russia before World War I the swastika was a favorite sign of the last Russian Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. She placed it where she could for happiness, including drawing it in pencil on the walls and windows in the Ipatiev House – where the royal family was executed. There, she also drew a swastika on the wallpaper above the bed where the heir apparently slept.[87] It was printed on some banknotes of the Russian Provisional Government (1917) and some sovznaks (1918–1922).[88] In 1919 it was approved as insignia for the Kalmyk formations,[89] and for a short period had a certain popularity amongst some artists, politics and army groups.[90] Also it was present on icons, vestments and clerical clothing[91] but in World War II it was removed, having become by association a symbol of the German occupation.[92]

In modern Russia, some neo-Nazis[93][94] and also Rodnovers argue that the Russian name of the swastika is kolovrat (Russian: коловрат, literally "spinning wheel"), but there are no ethnographic sources confirming this.[92][95] In vernacular speech the swastika had different names: for example, "breeze", as in Christianity the swastika represents spiritual movement, descent of the Holy Spirit, and therefore the "wind" and "spirit";[92] or ognevtsi ("little flames"), "geese", "hares" (a towel with a swastika was called a towel with "hares"), or "little horses".[91][92]

The neo-Nazi Russian National Unity group's branch in Estonia is officially registered under the name "Kolovrat" and published an extremist newspaper in 2001 under the same name.[93] A criminal investigation found the paper included an array of racial epithets. One Narva resident was sentenced to one year in jail for distribution of Kolovrat.[96] The Kolovrat has since been used by the Rusich Battalion, a Russian militant group known for its operation during the war in Donbas.[97][additional citation(s) needed]

Celts

The bronze frontispiece of a ritual pre-Christian (c. 350–50 BCE) shield found in the River Thames near Battersea Bridge (hence "Battersea Shield") is embossed with 27 swastikas in bronze and red enamel.[98] An Ogham stone found in Anglish, Co Kerry, Ireland (CIIC 141) was modified into an early Christian gravestone, and was decorated with a cross pattée and two swastikas.[99] The Book of Kells (c. 800 CE) contains swastika-shaped ornamentation. At the Northern edge of Ilkley Moor in West Yorkshire, there is a swastika-shaped pattern engraved in a stone known as the Swastika Stone.[100] A number of swastikas have been found embossed in Galician metal pieces and carved in stones, mostly from the Castro Culture period, although there also are contemporary examples (imitating old patterns for decorative purposes).[101][102]

Greco-Roman antiquity

Ancient Greek architectural, clothing and coin designs are replete with single or interlinking swastika motifs. There are also gold plate fibulae from the 8th century BCE decorated with an engraved swastika.[103] Related symbols in classical Western architecture include the cross, the three-legged triskele or triskelion and the rounded lauburu. The swastika symbol is also known in these contexts by a number of names, especially gammadion,[104] or rather the tetra-gammadion. The name gammadion comes from its being seen as being made up of four Greek gamma (Γ) letters. Ancient Greek architectural designs are replete with the interlinking symbol.

In Greco-Roman art and architecture, and in Romanesque and Gothic art in the West, isolated swastikas are relatively rare, and the swastika is more commonly found as a repeated element in a border or tessellation. The swastika often represented perpetual motion, reflecting the design of a rotating windmill or watermill. A meander of connected swastikas makes up the large band that surrounds the Augustan Ara Pacis.

A design of interlocking swastikas is one of several tessellations on the floor of the cathedral of Amiens, France.[105] A border of linked swastikas was a common Roman architectural motif,[106] and can be seen in more recent buildings as a neoclassical element. A swastika border is one form of meander, and the individual swastikas in such a border are sometimes called Greek keys. There have also been swastikas found on the floors of Pompeii.[107]

- Greco-Roman examples

-

Greek tetraskelion.

-

Swastika meander pattern.

Illyrians

The swastika was widespread among the Illyrians, symbolising the Sun. The Sun cult was the main Illyrian cult; the Sun was represented by a swastika in clockwise motion, and it stood for the movement of the Sun.[108]

Armenia

In Armenia the swastika is called the "arevakhach" and "kerkhach" (Armenian: կեռխաչ)[109][dubious – discuss] and is the ancient symbol of eternity and eternal light (i.e. God). Swastikas in Armenia were founded on petroglyphs from the copper age, predating the Bronze Age. During the Bronze Age it was depicted on cauldrons, belts, medallions and other items.[110] Among the oldest petroglyphs is the seventh letter of the Armenian alphabet: Է ("E" which means "is" or "to be") depicted as a half-swastika.

Swastikas can also be seen on early Medieval churches and fortresses, including the principal tower in Armenia's historical capital city of Ani.[109] The same symbol can be found on Armenian carpets, cross-stones (khachkar) and in medieval manuscripts, as well as on modern monuments as a symbol of eternity.[111]

Medieval and early modern Europe

Swastika shapes have been found on numerous artefacts from Iron Age Europe.[109][112][113][114][13]

- European use of the swastika

-

Bashkirs symbol of the sun and fertility

-

Ancient Roman mosaics of La Olmeda, Spain

-

Swastika on a Roman mosaic in Veli Brijun, Croatia.

-

Swastika on the Lielvārde Belt, Latvia.

In Christianity, the swastika is used as a hooked version of the Christian Cross, the symbol of Christ's victory over death. Some Christian churches built in the Romanesque and Gothic eras are decorated with swastikas, carrying over earlier Roman designs. Swastikas are prominently displayed in a mosaic in the St. Sophia church of Kyiv, Ukraine dating from the 12th century. They also appear as a repeating ornamental motif on a tomb in the Basilica of St. Ambrose in Milan.[115]

A ceiling painted in 1910 in the church of St Laurent in Grenoble has many swastikas. It can be visited today because the church became the archaeological museum of the city. A proposed direct link between it and a swastika floor mosaic in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Amiens, which was built on top of a pagan site at Amiens, France in the 13th century, is considered unlikely. The stole worn by a priest in the 1445 painting of the Seven Sacraments by Rogier van der Weyden presents the swastika form simply as one way of depicting the cross.

Swastikas also appear in art and architecture during the Renaissance and Baroque era. The fresco The School of Athens shows an ornament made out of swastikas, and the symbol can also be found on the facade of the Santa Maria della Salute, a Roman Catholic church and minor basilica located at Punta della Dogana in the Dorsoduro sestiere of the city of Venice.

In the Polish First Republic the symbol of the swastika was also popular with the nobility. According to chronicles, the Rus' prince Oleg, who in the 9th century attacked Constantinople, nailed his shield (which had a large red swastika painted on it) to the city's gates.[116] Several noble houses, e.g. Boreyko, Borzym, and Radziechowski from Ruthenia, also had swastikas as their coat of arms. The family reached its greatness in the 14th and 15th centuries and its crest can be seen in many heraldry books produced at that time.

The swastika was also a heraldic symbol, for example on the Boreyko coat of arms, used by noblemen in Poland and Ukraine. In the 19th century the swastika was one of the Russian Empire's symbols, and was used on coinage as a backdrop to the Russian eagle.[117][118]

A swastika can be seen on stonework at Valle Crucis Abbey, near Llangollen.

-

A swastika composed of Hebrew letters as a mystical symbol from the Jewish Kabbalistic work "Parashat Eliezer"

-

Swastikas on the vestments of the effigy of Bishop William Edington (d. 1366) in Winchester Cathedral

-

The Victorian-era reproduction of the Swastika Stone on Ilkley Moor, which sits near the original to aid visitors in interpreting the carving

Africa

Swastikas can be seen in various African cultures. In Ethiopia the Swastika is carved in the window of the famous 12th Century rock-hewn church Lalibela. In Ghana, the swastika is among the adinkra symbols of the Akan peoples. Called nkontim, swastikas could be found on Ashanti gold weights and clothing.[119]

-

Ashanti weight in Africa

-

Nkontim adinkra symbol representing loyalty and readiness to serve.

-

Carved fretwork forming a swastika in the window of a Lalibela rock-hewn church in Ethiopia.

Americas

The swastika is a Navajo symbol for good luck, also translated to "whirling log". The symbol was used on state road signs in Arizona.[120][121]

Early 20th century

In the Western world, the symbol experienced a resurgence following the archaeological work in the late 19th century of Heinrich Schliemann, who discovered the symbol in the site of ancient Troy and associated it with the ancient migrations of Proto-Indo-Europeans, whose proto-language was not coincidentally termed "Proto-Indo-Germanic" by German language historians. He connected it with similar shapes found on ancient pots in Germany, and theorised[clarification needed] that the swastika was a "significant religious symbol of our remote ancestors", linking it to ancient Teutons, Greeks of the time of Homer and Indians of the Vedic era.[122][123] By the early 20th century, it was used worldwide and was regarded as a symbol of good luck and success.

Schliemann's work soon became intertwined with the political völkisch movements, which used the swastika as a symbol for the "Aryan race" – a concept that theorists such as Alfred Rosenberg equated with a Nordic master race originating in northern Europe. Since its adoption by the Nazi Party of Adolf Hitler, the swastika has been associated with Nazism, fascism, racism in its (white supremacy) form, the Axis powers in World War II, and the Holocaust in much of the West. The swastika remains a core symbol of neo-Nazi groups.

The Benedictine choir school at Lambach Abbey, Upper Austria, which Hitler attended for several months as a boy, had a swastika chiseled into the monastery portal and also the wall above the spring grotto in the courtyard by 1868. Their origin was the personal coat of arms of Abbot Theoderich Hagn of the monastery in Lambach, which bore a golden swastika with slanted points on a blue field.[124]

Europe

Britain

In the 1880s the Theosophical Society adopted a swastika as part of its seal, along with an Om, a hexagram or star of David, an Ankh and an Ouroboros. Unlike the much more recent Raëlian movement, the Theosophical Society symbol has been free from controversy, and the seal is still used. The current seal also includes the text "There is no religion higher than truth."[125] The British author and poet Rudyard Kipling used the symbol on the cover art of a number of his works, including The Five Nations, 1903, which has it twinned with an elephant.

Denmark

The Danish brewery company Carlsberg Group used the swastika as a logo[126] from the 19th century until the middle of the 1930s when it was discontinued because of association with the Nazi Party in neighbouring Germany. In Copenhagen at the entrance gate, and tower, of the company's headquarters, built in 1901, swastikas can still be seen. The tower is supported by four stone elephants, each with a swastika on each side. The tower they support is topped with a spire, in the middle of which is a swastika.[127]

Iceland

The Swastika, or the Thor's hammer as the logo was called, was used as the logo for H/f. Eimskipafjelag Íslands[128] from its founding in 1914 until the Second World War when it was discontinued and changed to read only the letters Eimskip.

Ireland

The Swastika Laundry was a laundry founded in 1912, located on Shelbourne Road, Ballsbridge, a district of Dublin, Ireland. In the 1950s, Heinrich Böll came across a van belonging to the company while he was staying in Ireland, leading to some awkward moments before he realised the company was older than Nazism and totally unrelated to it. The chimney of the boiler-house of the laundry still stands, but the laundry has been redeveloped.[129][130]

Finland

In Finland, the swastika (vääräpää meaning "crooked-head", and later hakaristi, meaning "hook-cross") was often used in traditional folk-art products, as a decoration or magical symbol on textiles and wood. The swastika was also used by the Finnish Air Force until 1945, and is still used on air force flags.

The tursaansydän, an elaboration on the swastika, is used by scouts in some instances,[131] and by a student organisation.[132] The Finnish village of Tursa uses the tursaansydän as a kind of a certificate of authenticity on products made there, and is the origin of this name of the symbol (meaning "heart of Tursa"),[133] which is also known as the mursunsydän ("walrus-heart"). Traditional textiles are still made in Finland with swastikas as parts of traditional ornaments.

Finnish military

The Finnish Air Force used the swastika as an emblem, introduced in 1918, until January 2017.[134] The type of swastika adopted by the air-force was the symbol of luck for the Swedish count Eric von Rosen, who donated one of its earliest aircraft; he later became a prominent figure in the Swedish Nazi movement.

The swastika was also used by the women's paramilitary organisation Lotta Svärd, which was banned in 1944 in accordance with the Moscow Armistice between Finland and the allied Soviet Union and Britain.

The President of Finland is the grand master of the Order of the White Rose. According to the protocol, the president shall wear the Grand Cross of the White Rose with collar on formal occasions. The original design of the collar, decorated with nine swastikas, dates from 1918 and was designed by the artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela. The Grand Cross with the swastika collar has been awarded 41 times to foreign heads of state. To avoid misunderstandings, the swastika decorations were replaced by fir crosses at the decision of president Urho Kekkonen in 1963 after it became known that the President of France Charles De Gaulle was uncomfortable with the swastika collar.

Also a design by Gallen-Kallela from 1918, the Cross of Liberty has a swastika pattern in its arms. The Cross of Liberty is depicted in the upper left corner of the standard of the President of Finland.[135]

In December 2007, a silver replica of the World War II-period Finnish air defence's relief ring decorated with a swastika became available as a part of a charity campaign.[136]

The original war-time idea was that the public swap their precious metal rings for the state air defence's relief ring, made of iron.

In 2017, the old logo of Finnish Air Force Command with Swastika was replaced by a new logo showing golden eagle and a circle of wings. However, the logo of Finland's air force academy still keeps the swastika symbol.[137]

Latvia

The swastika is an ancient Baltic thunder cross symbol (pērkona krusts; also fire cross, ugunskrusts), used to decorate objects, traditional clothing and in archaeological excavations.[138][139][140] Latvia adopted the swastika, for its Air Force in 1918/1919 and continued its use until the Soviet occupation in 1940.[141][142] The cross itself was maroon on a white background, mirroring the colors of the Latvian flag. Earlier versions pointed counter-clockwise, while later versions pointed clock-wise and eliminated the white background.[143][144] Various other Latvian Army units and the Latvian War College[145] (the predecessor of the National Defence Academy) also had adopted the symbol in their battle flags and insignia during the Latvian War of Independence.[146] A stylised fire cross is the base of the Order of Lāčplēsis, the highest military decoration of Latvia for participants of the War of Independence.[147] The Pērkonkrusts, an ultra-nationalist political organisation active in the 1930s, also used the fire cross as one of its symbols.

Lithuania

As in Latvia, the symbol is a traditional Baltic ornament,[138][148] found on relics dating from at least the 13th century.[149]

Sweden

The Swedish company ASEA, now a part of ABB, in the late 1800s introduced a company logo featuring a swastika. The logo was replaced in 1933, when Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. During the early 1900s, the swastika was used as a symbol of electric power, perhaps because it resembled a waterwheel or turbine. On maps of the period, the sites of hydroelectric power stations were marked with swastikas.

Norway

The headquarters of the Oslo Municipal Power Station was designed by architects Bjercke and Eliassen in 1928–1931. Swastikas adorn its wrought iron gates. The architects knew the swastika as a symbol of electricity and were probably not yet aware that it had been usurped by the German Nazi party and would soon become the foremost symbol of the German Reich. The fact that these gates survived the cleanup after the German occupation of Norway during WW II is a testimony to the innocence and good faith of the power plant and its architects. The architects Bjercke and Eliassen knew the swastika as a symbol of power plants on maps in Scandinavia, and as the logo of Allmänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget, ASEA.[150]

North America

The swastika motif is found in some traditional Native American art and iconography. Historically, the design has been found in excavations of Mississippian-era sites in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, and on objects associated with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (S.E.C.C.). It is also widely used by a number of southwestern tribes, most notably the Navajo, and plains nations such as the Dakota. Among various tribes, the swastika carries different meanings. To the Hopi it represents the wandering Hopi clan; to the Navajo it is one symbol for the whirling log (tsin náálwołí), a sacred image representing a legend that is used in healing rituals.[151] A brightly coloured First Nations saddle featuring swastika designs is on display at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada.[152]

The Passamaquoddy Native American tribe, now located in the state of Maine and in Canada, used an elongated swastika on their war canoes in the American colonial period as well as later.[153] A carving of a canoe with a Passamaquody swastika was found in a ruin in the Argonne Forest in France, having been carved there by Moses Neptune, an American soldier of Passamaquody heritage, who was one of the last American soldiers to die in battle in World War I.[154]

Before the 1930s, the symbol for the 45th Infantry Division of the United States Army was a red diamond with a yellow swastika, a tribute to the large Native American population in the southwestern United States. It was later replaced with a thunderbird symbol.

A swastika shape is a symbol in the culture of the Kuna people of Kuna Yala, Panama. In Kuna tradition it symbolises the octopus that created the world, its tentacles pointing to the four cardinal points.[155]

In February 1925, the Kuna revolted vigorously against Panamanian suppression of their culture, and in 1930 they assumed autonomy. The flag they adopted at that time is based on the swastika shape, and remains the official flag of Kuna Yala. A number of variations on the flag have been used over the years: red top and bottom bands instead of orange were previously used, and in 1942 a ring (representing the traditional Kuna nose-ring) was added to the center of the flag to distance it from the symbol of the Nazi party.[156]

The town of Swastika, Ontario, Canada, and the hamlet of Swastika, New York were named after the symbol.

From 1909 to 1916, the K-R-I-T automobile, manufactured in Detroit, Michigan, used a right-facing swastika as their trademark.

- The swastika in North America

-

Chief William Neptune of the Passamaquoddy, wearing a headdress and outfit adorned with swastikas

-

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School basketball team in 1909.

-

Pillow cover offered by the Girls' Club in The Ladies Home Journal in 1912

-

Fernie Swastikas women's hockey team, 1922

-

The Buffum tool company of Louisiana used the swastika as its trademark. It went out of business in the 1920s

-

Flag of the Kuna people.

-

Alternate version adopted in 1942.

Nazi symbol

Use in Nazism

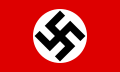

The swastika was widely used in Europe at the start of the 20th century. It symbolised many things to the Europeans, with the most common symbolism being of good luck and auspiciousness.[5] In the wake of widespread popular usage, in post-World War I Germany, the newly established Nazi Party formally adopted the swastika in 1920.[157][158] The emblem was a black swastika rotated 45 degrees on a white circle on a red background. This insignia was used on the party's flag, badge, and armband.

In his 1925 work Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler writes: "I myself, meanwhile, after innumerable attempts, had laid down a final form; a flag with a red background, a white disk, and a black hooked cross in the middle. After long trials I also found a definite proportion between the size of the flag and the size of the white disk, as well as the shape and thickness of the hooked cross."

When Hitler created a flag for the Nazi Party, he sought to incorporate both the swastika and "those revered colors expressive of our homage to the glorious past and which once brought so much honor to the German nation". (Red, white, and black were the colours of the flag of the old German Empire.) He also stated: "As National Socialists, we see our program in our flag. In red, we see the social idea of the movement; in white, the nationalistic idea; in the hooked cross, the mission of the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man, and, by the same token, the victory of the idea of creative work."[159]

The swastika was also understood as "the symbol of the creating, effecting life" (das Symbol des schaffenden, wirkenden Lebens) and as "race emblem of Germanism" (Rasseabzeichen des Germanentums).[160]

The concept of racial hygiene was an ideology central to Nazism, though it is scientific racism.[161][162] High-ranking Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg noted that the Indo-Aryan peoples were both a model to be imitated and a warning of the dangers of the spiritual and racial "confusion" that, he believed, arose from the proximity of races. The Nazis co-opted the swastika as a symbol of the Aryan master race.

Before the Nazis, the swastika was already in use as a symbol of German völkisch nationalist movements (Völkische Bewegung).

José Manuel Erbez says:

The first time the swastika was used with an "Aryan" meaning was on 25 December 1907, when the self-named Order of the New Templars, a secret society founded by Lanz von Liebenfels, hoisted at Werfenstein Castle (Austria) a yellow flag with a swastika and four fleurs-de-lys.[163]

However, Liebenfels was drawing on an already-established use of the symbol.

On 14 March 1933, shortly after Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of Germany, the NSDAP flag was hoisted alongside Germany's national colors. As part of the Nuremberg Laws, the NSDAP flag – with the swastika slightly offset from center – was adopted as the sole national flag of Germany on 15 September 1935.[164]

Use by anti-Nazis

During World War II it was common to use small swastikas to mark air-to-air victories on the sides of Allied aircraft, and at least one British fighter pilot inscribed a swastika in his logbook for each German plane he shot down.[165]

Post-World War II stigmatisation

Because of its use by Nazi Germany, the swastika since the 1930s has been largely associated with Nazism. In the aftermath of World War II it has been considered a symbol of hate in the West,[166] and of white supremacy in many Western countries.[167]

As a result, all use of it, or its use as a Nazi or hate symbol, is prohibited in some countries, including Germany. In some countries, such as the United States (in the 2003 case Virginia v. Black), the highest courts have ruled that the local governments can prohibit the use of swastika along with other symbols such as cross burning, if the intent of the use is to intimidate others.[6]

Germany

The German and Austrian postwar criminal code makes the public showing of the swastika, the sig rune, the Celtic cross (specifically the variations used by white power activists), the wolfsangel, the odal rune and the Totenkopf skull illegal, except for scholarly reasons. It is also censored from the reprints of 1930s railway timetables published by the Reichsbahn. The swastikas on Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain temples are exempt, as religious symbols cannot be banned in Germany.[168]

A controversy was stirred by the decision of several police departments to begin inquiries against anti-fascists.[169] In late 2005 police raided the offices of the punk rock label and mail order store "Nix Gut Records" and confiscated merchandise depicting crossed-out swastikas and fists smashing swastikas. In 2006 the Stade police department started an inquiry against anti-fascist youths using a placard depicting a person dumping a swastika into a trashcan. The placard was displayed in opposition to the campaign of right-wing nationalist parties for local elections.[170]

On Friday, 17 March 2006, a member of the Bundestag, Claudia Roth reported herself to the German police for displaying a crossed-out swastika in multiple demonstrations against Neo-Nazis, and subsequently got the Bundestag to suspend her immunity from prosecution. She intended to show the absurdity of charging anti-fascists with using fascist symbols: "We don't need prosecution of non-violent young people engaging against right-wing extremism." On 15 March 2007, the Federal Court of Justice of Germany (Bundesgerichtshof) held that the crossed-out symbols were "clearly directed against a revival of national-socialist endeavors", thereby settling the dispute for the future.[171][172][173]

On 9 August 2018, Germany lifted the ban on the usage of swastikas and other Nazi symbols in video games. "Through the change in the interpretation of the law, games that critically look at current affairs can for the first time be given a USK age rating," USK managing director Elisabeth Secker told CTV. "This has long been the case for films and with regards to the freedom of the arts, this is now rightly also the case with computer and videogames."[174][175]

Legislation in other European countries

- Until 2013 in Hungary, it was a criminal misdemeanour to publicly display "totalitarian symbols", including the swastika, the SS insignia, and the Arrow Cross, punishable by custodial arrest.[176][177] Display for academic, educational, artistic or journalistic reasons was allowed at the time. The communist symbols of hammer and sickle and the red star were also regarded as totalitarian symbols and had the same restriction by Hungarian criminal law until 2013.[176]

- In Latvia, public display of Nazi and Soviet symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is prohibited in public events since 2013.[178][179] However, in a court case from 2007 a regional court in Riga held that the swastika can be used as an ethnographic symbol, in which case the ban does not apply.[180]

- In Lithuania, public display of Nazi and Soviet symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is an administrative offence, punishable by a fine from 150 to 300 euros. According to judicial practice, display of a non-Nazi swastika is legal.[181]

- In Poland, public display of Nazi symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is a criminal offence punishable by up to eight years of imprisonment. The use of the swastika as a religious symbol is legal.[182]

Attempted ban in the European Union

The European Union's Executive Commission proposed a European Union-wide anti-racism law in 2001, but European Union states failed to agree on the balance between prohibiting racism and freedom of expression.[183] An attempt to ban the swastika across the EU in early 2005 failed after objections from the British Government and others. In early 2007, while Germany held the European Union presidency, Berlin proposed that the European Union should follow German Criminal Law and criminalise the denial of the Holocaust and the display of Nazi symbols including the swastika, which is based on the Ban on the Symbols of Unconstitutional Organisations Act. This led to an opposition campaign by Hindu groups across Europe against a ban on the swastika. They pointed out that the swastika has been around for 5,000 years as a symbol of peace.[184][185] The proposal to ban the swastika was dropped by Berlin from the proposed European Union wide anti-racism laws on 29 January 2007.[183]

Latin America

- The manufacture, distribution or broadcasting of the swastika, with the intent to propagate Nazism, is a crime in Brazil as dictated by article 20, paragraph 1, of federal statute 7.716, passed in 1989. The penalty is a two to five years prison term and a fine.[186]

- The former flag of the Guna Yala autonomous territory of Panama was based on a swastika design. In 1942 a ring was added to the centre of the flag to differentiate it from the symbol of the Nazi Party (this version subsequently fell into disuse).[156]

United States

The public display of Nazi-era German flags (or any other flags) is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees the right to freedom of speech.[187] The Nazi Reichskriegsflagge has also been seen on display at white supremacist events within United States borders.[188]

As with many neo-Nazi groups across the world, the American Nazi Party used the swastika as part of its flag before its first dissolution in 1967. The symbol was chosen by the organisation's founder, George Lincoln Rockwell.[189] It was "re-used" by successor organisations in 1983, without the publicity Rockwell's organisation enjoyed.

The swastika, in various iconographic forms, is one of the hate symbols identified in use as graffiti in US schools, and is described as such in a 1999 US Department of Education document, "Responding to Hate at School: A Guide for Teachers, Counselors and Administrators", edited by Jim Carnes, which provides advice to educators on how to support students targeted by such hate symbols and address hate graffiti. Examples given show that it is often used alongside other white supremacist symbols, such as those of the Ku Klux Klan, and note a "three-bladed" variation used by skinheads, white supremacists, and "some South African extremist groups".[190]

In 2010 the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) downgraded the swastika from its status as a Jewish hate symbol, saying "We know that the swastika has, for some, lost its meaning as the primary symbol of Nazism and instead become a more generalised symbol of hate."[191] The ADL notes on their website that the symbol is often used as "shock graffiti" by juveniles, rather than by individuals who hold white supremacist beliefs, but it is still a predominant symbol amongst American white supremacists (particularly as a tattoo design) and used with anti-Semitic intention.[192]

Media

In 2010, Microsoft officially spoke out against use of the swastika by players of the first-person shooter Call of Duty: Black Ops. In Black Ops, players are allowed to customise their name tags to represent, essentially, whatever they want. The swastika can be created and used, but Stephen Toulouse, director of Xbox Live policy and enforcement, said players with the symbol on their name tag will be banned (if someone reports it as inappropriate) from Xbox Live.[193]

In the Indiana Jones Stunt Spectacular in Disney Hollywood Studios in Orlando, Florida, the swastikas on German trucks, aircraft and actor uniforms in the reenactment of a scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark were removed in 2004. The swastika has been replaced by a stylised Greek cross.[194]

Nazi imagery was adapted and incorporated into the 2016 sci-fi movie 2BR02B: To Be or Naught to Be.[195]

Contemporary use

Asia

Central Asia

In 2005, authorities in Tajikistan called for the widespread adoption of the swastika as a national symbol. President Emomali Rahmonov declared the swastika an Aryan symbol, and 2006 "the year of Aryan culture", which would be a time to "study and popularise Aryan contributions to the history of the world civilisation, raise a new generation (of Tajiks) with the spirit of national self-determination, and develop deeper ties with other ethnicities and cultures".[196]

East and Southeast Asia

In East Asia, the swastika is prevalent in Buddhist monasteries and communities. It is commonly found in Buddhist temples, religious artefacts, texts related to Buddhism and schools founded by Buddhist religious groups. It also appears as a design or motif (singularly or woven into a pattern) on textiles, architecture and various decorative objects as a symbol of luck and good fortune. The icon is also found as a sacred symbol in the Bon tradition, but in the left-facing orientation.[197][198]

Many Chinese religions make use of the swastika symbol, including Guiyidao and Shanrendao. The Red Swastika Society, which is the philanthropic branch of Guiyidao, runs two schools in Hong Kong (the Hong Kong Red Swastika Society Tai Po Secondary School[199] and the Hong Kong Red Swastika Society Tuen Mun Primary School[200]) and one in Singapore (Red Swastika School). All of them show the swastika in their logos.

Among the predominantly Hindu population of Bali, in Indonesia, the swastika is common in temples, homes and public spaces. Similarly, the swastika is a common icon associated with Buddha's footprints in Theravada Buddhist communities of Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia.[198]

In Japan, the swastika is also used as a map symbol and is designated by the Survey Act and related Japanese governmental rules to denote a Buddhist temple.[201]

The city of Hirosaki in Aomori Prefecture designates this symbol as its official flag, which stemmed from its use in the emblem of the Tsugaru clan, the lords of Hirosaki Domain during the Edo period.

Indian subcontinent

In Bhutan, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka, the swastika is common. Temples, businesses and other organisations, such as the Buddhist libraries, Ahmedabad Stock Exchange and the Nepal Chamber of Commerce,[202] use the swastika in reliefs or logos.[198] Swastikas are ubiquitous in Indian and Nepalese communities, located on shops, buildings, transport vehicles, and clothing. The swastika remains prominent in Hindu ceremonies such as weddings. The left facing sauwastika symbol is found in tantric rituals.[8]

Musaeus College in Colombo, Sri Lanka, a Buddhist girls' school, has a left facing swastika in their school logo.

In India, Swastik and Swastika, with their spelling variants, are first names for males and females respectively, for instance with Swastika Mukherjee. The Emblem of Bihar contains two swastikas.

In Bhutan, swastika motif is found in its architecture, fabric and religious ceremonies.

Western misinterpretation of Asian use

Since the end of the 20th century, and through the early 21st century, confusion and controversy has occurred when personal-use goods bearing the traditional Jain, Buddhist, or Hindu symbols have been exported to the West, notably to North America and Europe, and have been interpreted by purchasers as bearing a Nazi symbol. This has resulted in several such products having been boycotted or pulled from shelves.

When a ten-year-old boy in Lynbrook, New York, bought a set of Pokémon cards imported from Japan in 1999, two of the cards contained the left-facing Buddhist swastika. The boy's parents misinterpreted the symbol as the right-facing Nazi swastika and filed a complaint to the manufacturer. Nintendo of America announced that the cards would be discontinued, explaining that what was acceptable in one culture was not necessarily so in another; their action was welcomed by the Anti-Defamation League who recognised that there was no intention to offend, but said that international commerce meant that, "Isolating [the Swastika] in Asia would just create more problems."[18]

In 2002, Christmas crackers containing plastic toy red pandas sporting swastikas were pulled from shelves after complaints from customers in Canada. The manufacturer, based in China, said the symbol was presented in a traditional sense and not as a reference to the Nazis, and apologised to the customers for the cross-cultural mixup.[203]

New religious movements

Besides its use as a religious symbol in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, which can be traced back to pre-modern traditions, the swastika is also used by adherents of a large number of new religious movements which were established in the modern period.

- The Raëlian Movement, whose adherents believe extraterrestrials created all life on earth, use a symbol that is often the source of considerable controversy: an interlaced star of David and a swastika. The Raelians say the Star of David represents infinity in space whereas the swastika represents infinity in time – no beginning and no end in time, and everything being cyclic.[204] In 1991, the symbol was changed in order to remove the swastika, out of respect to the victims of the Holocaust, but as of 2007 it has been restored to its original form.[205]

- The Falun Gong qigong movement uses a symbol that features a large swastika surrounded by four smaller (and rounded) ones, interspersed with yin-and-yang symbols.[206]

- The swastika is a holy symbol in Germanic Heathenry, along with the hammer of Thor and runes. This tradition – which is found in Scandinavia, Germany, and elsewhere – considers the swastika to be derived from a Norse symbol for the sun. Their use of the symbol has led people to accuse them of being a neo-Nazi group.[207][208][209]

- A "fire cross" is used by the Baltic neo-pagan movements Dievturība in Latvia and Romuva in Lithuania.[210]

- A variant of the swastika, the eight-armed kolovrat, is a commonly-used symbol in Rodnovery, which is practiced in Slavic countries. It represents the sun and the creator deities Rod and Svarog.

See also

- Borjgali

- Brigid's cross

- Camunian rose

- Fasces

- Fascist symbolism

- Svarog

- Svastikasana

- Swastika curve

- Yoke and arrows

References

- ^ referring to the Greek letter Γ, capital gamma, for the shape of the symbol's arms

- ^ a b Bruce M. Sullivan (2001). The A to Z of Hinduism. Scarecrow Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-4616-7189-3.

- ^ a b c d Adrian Snodgrass (1992). The Symbolism of the Stupa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-81-208-0781-5.

- ^ a b Cort, John E. (2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0195132342 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Campion, Mukti Jain (23 October 2014). "How the world loved the swastika – until Hitler stole it". BBC News Magazine.

- ^ a b c "History of the Swastika". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2009.

- ^ a b c Wiener, Richard L.; Richter, Erin (2008). "Symbolic hate: Intention to intimidate, political ideology, and group association". Law and Human Behavior. 32 (6). American Psychological Association: 463–476. doi:10.1007/s10979-007-9119-3. PMID 18030607. S2CID 25546323.

- ^ ""Swastika" Etymology". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Swastika: SYMBOL, Encyclopædia Britannica (2017)

- ^ a b Art Silverblatt; Nikolai Zlobin (2015). International Communications: A Media Literacy Approach. Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-317-46760-1.

Buddha's footprints were said to be swastikas.

- ^ Pant, Mohan; Funo, Shūji (2007). Stupa and Swastika: Historical Urban Planning Principles in Nepal's Kathmandu Valley. National University of Singapore Press. p. 231 with note 5. ISBN 978-9971-69-372-5.

- ^ Greg, Robert Philips (1884). On the Meaning and Origin of the Fylfot and Swastika. Nichols and Sons. pp. 6, 29.

- ^ a b c d Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-1932476033 – via Google Books.[page needed]

- ^ a b c "The Migration of Symbols Index". sacred-texts.com.

- ^ Press, Cambridge University (2008). Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3125179882 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Faience button seal".

Faience button seal (H99-3814/8756-01) with swastika motif found on the floor of Room 202 (Trench 43).

- ^ a b Lorraine Boissoneault (6 April 2017), The Man Who Brought the Swastika to Germany, and How the Nazis Stole It, Smithsonian Magazine

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer. "History of Swastika". about.com. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ a b Steven Heller, "The Swastika: Symbol Beyond Redemption?" Allworth Press, New York, 2008 pp. 156–157.[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Heinrich Schliemann (1880). Ilios. J. Murray. pp. 347–348.

- ^ Zimmer, Heinrich (2017). Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Allchin, F. R.; Erdosy, George (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2.

- ^ First recorded 1871 (OED); alternative historical English spellings include suastika, swastica, and svastica; see, for example: Notes and Queries. Oxford University Press. 31 March 1883. p. 259.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2016). "Swastika". Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Mees (2008), pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b c Monier Monier-Williams (1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, s.v. svastika (p. 1283).

- ^ A Vedic Concordance, Maurice Bloomfield, Harvard University Press, pp. 1052–1054

- ^ "Page:Sanskrit Grammar by Whitney p1.djvu/494 – Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Staal, Frits (April 1965). "Euclid and Pāṇini". Philosophy East and West. 15 (2): 99–116. doi:10.2307/1397332. JSTOR 1397332.

- ^ Cardona, George (1998). Pāṇini: A Survey of Research. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 268. ISBN 978-81-208-1494-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Panini (Indian Grammarian)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013.

- ^ Scharfe, Hartmut (1977). Grammatical Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-3-447-01706-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ The Migration of Symbols, by Eugène Goblet d'Alviella, (1894), p.40 at sacred-texts.com

- ^ "tetraskelion". Merriam-Webster Dictionary (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Melissa Cody's Whirling Logs: Don't You Dare Call Them Swastikas". Indian Country Today Media Network. 7 August 2013. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013.

- ^ Powers, John (2007). Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Shambhala Press. p. 509. ISBN 978-1-55939-835-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chessa, Luciano (2012). Luigi Russolo, Futurist: Noise, Visual Arts, and the Occult. University of California Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-520-95156-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Swastika Flag Specifications and Construction Sheet (Germany)". Flags of the World.

- ^ "CJK Unified Ideographs" (PDF). (4.83 MB), The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1. Unicode, Inc. 2005.

- ^ Big5: C9_C3, according to Wenlin

- ^ Big5+: 85_80, according to Wenlin

- ^ "Right-Facing Svasti Sign" (click "next" three times)

- ^ Paliga S., The tablets of Tǎrtǎria Dialogues d'histoire ancienne, vol. 19, n°1, 1993. pp. 9–43; (Fig. 5 on p. 28)

- ^ Freed, S. A. and R. S., "Origin of the Swastika", Natural History, January 1980, 68–75.

- ^ Guénon, René; Fohr, Samuel D. (2004). Symbols of Sacred Science. Sophia Perennis. pp. 64–67, 113–117. ISBN 978-0900588785.

- ^ Guénon, René; Fohr, Samuel D. (2004). Symbols of Sacred Science. Sophia Perennis. pp. 113–117, 130. ISBN 978-0900588785.

- ^ Assasi, Reza (2013). "Swastika: The Forgotten Constellation Representing the Chariot of Mithras". Anthropological Notebooks (Supplement: Šprajc, Ivan; Pehani, Peter, eds. Ancient Cosmologies and Modern Prophets: Proceedings of the 20th Conference of the European Society for Astronomy in Culture). XIX (2). Ljubljana: Slovene Anthropological Society. ISSN 1408-032X.

- ^ a b Gennady Zdanovich. "О мировоззрении древних жителей «Страны Городов»". Русский след, 26 June 2017.

- ^ Guénon, René; Fohr, Samuel D. (2004). Symbols of Sacred Science. Sophia Perennis. p. 117. ISBN 978-0900588785.

- ^ Sagan, Carl; Ann Druyan (1985). Comet. Ballantine Books. p. 496. ISBN 978-0-345-41222-5.

- ^ a b Kobres, Bob. "Comets and the Bronze Age Collapse". Archived from the original on 8 September 2009.

- ^ Hewitt, J.F.K. (1907). Primitive Traditional History: The Primitive History and Chronology of India, South-eastern and South-western Asia, Egypt, and Europe, and the Colonies Thence Sent Forth. Vol. 1. J. Parker and Company.

- ^ Good Housekeeping. Vol. 47. C. W. Bryan & Company. 1908.

- ^ Frank Hamilton Cushing: "Observations Relative to the Origin of the Fylfot or Swastika", American Anthropologist vol 9, no.2, June 1907 p335 at JSTOR

- ^ Campbell, Joseph (2002). The Flight of the Wild Gander. p. 117.

- ^ Campion, Mukti Jain (23 October 2014). "How the world loved the swastika – until Hitler stole it". BBC News. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Persian Sea magazine (2014). "The global role of the swastika in Iranian treasures, idols and carpets". Iranian Studies. Accessed 19 April 2021. In Persian.

- ^ https://civilica.com/doc/541074/

- ^ Dimitrova, Stefania. "Eight Thousand Years Ago Proto-Thracians Depicted the Evolution of the Divine – English". Courrier of UNESCO – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ a b Kathleen M. Nadeau (2010). Lee, Jonathan H. X. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABL-CLIO. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Staff (ndg) "Researchers find the Swastika predates the Indus Valley Civilization" Ancient Code; citing :lead project investigator" Joy Sen from the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur

- ^ Dunham, Dows "A Collection of 'Pot-Marks' from Kush and Nubia", Kush, 13, 131–147, 1965

- ^ (in Chinese) Bao Jing " “卍”与“卐”漫议 ("卍" "and "卐" Man Yee)". 6 January 2004, news.xinhuanet.com

- ^ "Jar with swastika design Majiayao culture, Machang type (Gansu or Qinghai province)". Daghlian Collection of Chinese Art

- ^ Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977). The Illyrians: history and culture. Noyes Press. ISBN 978-0815550525. Retrieved 14 February 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Textile fragment". V&A Museum. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Rp, Aravindan. "a real foot print of facts". Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ a term coined by Anna Roes, "Tierwirbel", IPEK, 1936–1937

- ^ Marija Gimbutas. "The Balts before the Dawn of History". Vaidilute.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2012.

- ^ Claude Lévi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology (1959), p. 267.

- ^ Tokhatyan, K.S. "Rock Carvings of Armenia, Fundamental Armenology, v. 2, 2015, pp. 1-22". Institute of History of NAS RA.

- ^ Freed, Stanley A. Research Pitfalls as a Result of the Restoration of Museum Specimens, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Volume 376, The Research Potential of Anthropological Museum Collections pp. 229–245, December 1981.

- ^ Steven Heller (2010). The Swastika: Symbol Beyond Redemption?. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 978-1581157895.

- ^ Mohan Pant, Shūji Funo (2007). Stupa and Swastika: Historical Urban Planning Principles in Nepal's Kathmandu Valley. NUS Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-9971693725.

- ^ "Dictionary – Definition of swastika". Archived from the original on 19 April 2013.

- ^ Druid, Morning Star Athbhreith Athbheochan Kwisatz Haderach. "A symbol is a thought, a drawing, an action, an archetype, etcetera of the conceptualization of a thing that exists either in reality or in the imagination". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ a b Janis Lander (2013). Spiritual Art and Art Education. Routledge. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-1-134-66789-5.

- ^ Chris Buckley (2005). Tibetan Furniture. Sambhala. pp. 5, 59, 68–70. ISBN 978-1-891640-20-9.

- ^ (Japanese) Hitoshi Takazawa, Encyclopedia of Kamon, Tōkyōdō Shuppan, 2008. ISBN 978-4-490-10738-8.

- ^ "Sayagata 紗綾形". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System.

- ^ "Significance of Swastika in Diwali celebrations". indiatribune.com. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Norman C. McClelland (2010). Encyclopedia of Reincarnation and Karma. McFarland. pp. 263–264. ISBN 978-0-7864-5675-8.

- ^ Kangxi Emperor (1716). Kangxi Dictionary (in Traditional Chinese). Qing Empire. p. 156.

- ^ a b c d e H.R. Ellis Davidson (1965). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe, p. 83. ISBN 978-0-14-013627-2

- ^ Margrethe, Queen, Poul Kjrum, Rikke Agnete Olsen (1990). Oldtidens Ansigt: Faces of the Past, p. 148. ISBN 978-87-7468-274-5

- ^ Grzegorzewic, Ziemisław (2016). O Bogach i ludziach. Praktyka i teoria Rodzimowierstwa Słowiańskiego [About the Gods and people. Practice and theory of Slavic Heathenism] (in Polish). Olsztyn: Stowarzyszenie "Kołomir". p. 57. ISBN 978-83-940180-8-5.

- ^ "Prasłowiańskie motywy architektoniczne". 1923. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Pierre Gilliard. Тринадцать лет при русском дворе = Thirteen Years at the Russian Court. – М.: «Захаров», 2006. – ISBN 5-8159-0566-6. – p. 175.

- ^ Николаев Р. Советские «кредитки» со свастикой? (in Russian) // «Миниатюра» 1992 №7, с. 11. archived

- ^ s:ru:Приказ войскам Юго-Восточного фронта от 3 November 1919 № 213, Степанов Алексей. Красный калейдоскоп гражданской войны. Калмыцкие формирования. 1919–1921 // Цейхгауз. – 1995 – № 4 – С. 43

- ^ Вольфганг, Акунов. "Книга: Барон фон Унгерн – Белый бог войны". e-reading.org.ua. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ a b Багдасаров Р. В. (2002). "Русские имена свастики". Свастика: священный символ. Этнорелигиоведческие очерки (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Moskow: Белые Альвы. ISBN 978-5-7619-0164-3.

- ^ a b c d Багдасаров, Роман. "Свастика: благословение или проклятие". Цена Победы. Echo of Moscow. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ a b Вячеслав Лихачев. Нацизм в России. с.5 – about symbolic of neo-nazi party "RNU"

- ^ McKay, George. Subcultures and New Religious Movements in Russia and East-Central Europe. p. 282.

- ^ Trubachyov, Oleg, ed. (1983). "Kolovortъ; кolovьrtъ" (PDF). Etymological dictionary of Slavic languages (in Russian). Vol. 10. Moskow: Nauka. pp. 149, 150.

- ^ Mudde, Cas. Racist Extremism in Central and Eastern Europe. p. 61.

- ^ "Сомнительная символика в лагере Азовец: зачем выглядеть, как сторонники ДНР?". www.theinsider.ua.

- ^ "The Battersea Shield". British Museum. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007.

- ^ "CISP entry". Ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Martin J Powell. "Megalithic Sites in England – Photo Archive".

- ^ Domínguez Fontela, J. (1938): Cerámica de Santa Tecla. Un hallazgo importantísimo in Faro de Vigo.

- ^ Romero, Bieito (2009): Xeometrías Máxicas de Galicia. Ir Indo, Vigo.

- ^ Biers, W.R. 1996. The Archaeology of Greece, p. 130. Cornell University Press, Ithaca/London.

- ^ "Perseus:image:1990.26.0822". Perseus.tufts.edu. 26 February 1990. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Robert Ferré. "Amiens Cathedral". Labyrinth Enterprises. Constructed from 1220 to 1402, Amiens Cathedral is the largest Gothic cathedral in France, a popular tourist attraction and since 1981 a UNESCO World Heritage Site. During World War I, Amiens was targeted by German forces but remained in Allied territory following the Battle of Amiens.

- ^ Gary Malkin. "Tockington Park Roman VillaArchived 21 May 2004 at the Wayback Machine". The Area of Bristol in Roman Times. 9 December 2002.

- ^ Lara Nagy, Jane Vadnal, "Glossary Medieval Art and Architecture", "Greek key or meander", University of Pittsburgh 1997–1998.

- ^ Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977). The Illyrians: history and culture. Noyes Press. pp. 182, 186. ISBN 978-0815550525.

- ^ a b c Concise Armenian Encyclopedia, Yerevan, v. II, p. 663

- ^ T. Wilson The swastika, the earlist known symbol and its migrations, pp. 807, 951

- ^ Holding, Nicholas; Holding, Deirdre (2011). Armenia. ISBN 978-1841623450.

- ^ Jacob G. Ghazarian (2006), The Mediterranean legacy in early Celtic Christianity: a journey from Armenia to Ireland, Bennett & Bloom, pp. 263, p. 171 "... Quite a different version of the Celtic triskelion, and perhaps the most common pre-Christian symbolism found throughout Armenian cultural tradition, is the round clockwise (occasionally counter-clockwise) whirling sun-like spiral fixed at a centre – the Armenian symbol of eternity."

- ^ K. B. Mehr, M. Markow, Mormon Missionaries enter Eastern Europe, Brigham Young University Press, 2002, pp. 399, p. 252 "... She viewed a tall building with spires and circular windows along the top of the walls. It was engraved with sun stones, a typical symbol of eternity in ancient Armenian architecture."

- ^ Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977). The Illyrians: history and culture. Noyes Press. ISBN 978-0815550525.

- ^ Carus, Paul (1907). The Open Court. Open Court Publishing Company.

- ^ "Swastika (Kolovrat) – Historical Roots" (in Russian). Distedu.ru. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Vladimir Nikolaevich. "The Swastika, the historical roots" (in Russian). Klk.pp.ru. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Vladimir Plakhotnyuk. "Kolovrat – Historical Roots – Collection of articles" (in Russian). Ruskolan.xpomo.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ Claire Polakoff. Into Indigo: African Textiles and Dyeing Techniques. 1980

- ^ Warnick, Ron (26 October 2006). "Swastikas on old Arizona road maps?". Route 66 News. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "Swastika signs on american advertisements and banners". www.mallstuffs.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Schliemann, H, Troy and its remains, London: Murray, 1875, pp. 102, 119–120.

- ^ Boxer, Sarah (29 June 2000). "One of the World's Great Symbols Strives for a Comeback". Think Tank. The New York Times. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Holocaust Chronology Archived 1 August 2012 at archive.today

- ^ "Emblem or the Seal | TS Adyar". www.ts-adyar.org.

- ^ "Flickr Album; "Probably the Best Photo's of Swastikas in the World"". Fiveprime.org. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Carlsberg Group Website".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Saga Eimskips". Eimskip. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Swastika chimney". The Irish Times. 3 March 2007. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ "Swastika Laundry (1912–1987)". Come here to me!. Comeheretome.wordpress.com. 26 April 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ "Partiolippukunta Pitkäjärven Vaeltajat ry". Pitva.Partio.net. Retrieved 2 March 2010.