Retigabine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Trobalt, Potiga |

| Other names | D-23129, ezogabine (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| MedlinePlus | a612028 |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60% |

| Protein binding | 60–80% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic glucuronidation and acetylation. CYP not involved |

| Elimination half-life | 8 hours (mean), range: 7–11 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Renal (84%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.158.123 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

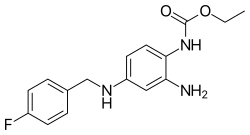

| Formula | C16H18FN3O2 |

| Molar mass | 303.337 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Retigabine (INN) or ezogabine (USAN) is an anticonvulsant used as an adjunctive treatment for partial epilepsies in treatment-experienced adult patients.[2] The drug was developed by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and GlaxoSmithKline. It was approved by the European Medicines Agency under the trade name Trobalt on March 28, 2011, and by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), under the trade name Potiga, on June 10, 2011. Production was discontinued in June 2017.[3][4]

Retigabine works primarily as a potassium channel opener—that is, by activating a certain family of voltage-gated potassium channels in the brain.[5][6][7] This mechanism of action is unique among antiepileptic drugs, and may hold promise for the treatment of other neurologic conditions, including tinnitus, migraine and neuropathic pain. The manufacturer withdrew retigabine from clinical use in 2017.

Adverse effects

The adverse effects found in the Phase II trial mainly affected the central nervous system, and appeared to be dose-related.[8] The most common adverse effects were drowsiness, dizziness, tinnitus and vertigo, confusion, and slurred speech.[9] Less common side effects included tremor, memory loss, gait disturbances, and double vision.[10] In 2013 FDA warned the public that Potiga (ezogabine) can cause blue skin discoloration and eye abnormalities characterized by pigment changes in the retina. FDA does not currently know if these changes are reversible. FDA is working with the manufacturer to gather and evaluate all available information to better understand these events. FDA will update the public when more information is available.[11] Psychiatric symptoms and difficulty urinating have also been reported, with most cases occurring in the first 2 months of treatment.[12][13]

Interactions

Retigabine appears to be free of drug interactions with most commonly used anticonvulsants. It may increase metabolism of lamotrigine (Lamictal), whereas phenytoin (Dilantin) and carbamazepine (CBZ, Tegretol) increase the clearance of retigabine.[13][14]

Concomitant use of retigabine and digoxin may increase serum concentration of the latter. In vitro studies suggest that the main metabolite of retigabine acts as a P-glycoprotein inhibitor, and may thus increase absorption and reduce elimination of digoxin.[13]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Retigabine acts as a neuronal KCNQ/Kv7 potassium channel opener, a mechanism of action markedly different from that of any current anticonvulsants.[5][6][7] This mechanism of action is similar to that of the chemically-similar flupirtine,[15] which is used mainly for its analgesic properties.

The term "channel opener" refers to a shift in the voltage dependence for channel opening towards more negative potentials. This means that KCNQ/Kv7 channels open at more negative potentials in the presence of Retigabine. Recently, it has also been shown that Retigabine stabilizes the open Kv7.2/7.3 channel, making deactivation slower with little change in voltage dependence. This effect of Retigabine is observed at concentrations below 10 micromolar.[16] A similar effect is observed on the homomeric Kv7.2 channel.[17]

Pharmacokinetics

Retigabine is quickly absorbed, and reaches maximum plasma concentrations between half an hour and 2 hours after a single oral dose. It has a moderately high oral bioavailability (50–60%), a high volume of distribution (6.2 L/kg), and a terminal half-life of 8 to 11 hours.[14] Retigabine requires thrice-daily dosing due to its short half-life.[8][9][13]

Retigabine is metabolized in the liver, by N-glucuronidation and acetylation. The cytochrome P450 system is not involved. Retigabine and its metabolites are excreted almost completely (84%) by the kidneys.[13][14]

History

Among the newer anticonvulsants, retigabine was one of the most widely studied in the preclinical setting: it was the subject of over 100 published studies before clinical trials began. In preclinical tests, it was found to have a very broad spectrum of activity—being effective in nearly all the animal models of seizures and epilepsy used: retigabine suppresses seizures induced by electroshock, electrical kindling of the amygdala, pentylenetetrazol, kainate, NMDA, and picrotoxin.[18] Researchers hoped this wide-ranging activity would translate to studies in humans as well.[8]

Clinical trials

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase II clinical trial, retigabine was added to the treatment regimen of 399 participants with partial seizures that were refractory to therapy with other antiepileptic drugs. The frequency with which seizures occurred was significantly reduced (by 23 to 35%) in participants receiving retigabine, and approximately one fourth to one third of participants had their seizure frequency reduced by more than 50%. Higher doses were associated with a greater response to treatment.[8][10][9]

A Phase II trial meant to assess the safety and efficacy of retigabine for treating postherpetic neuralgia was completed in 2009, but failed to meet its primary endpoint. Preliminary results were reported by Valeant as "inconclusive".[19]

Regulatory approval

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration accepted Valeant's New Drug Application for retigabine on December 30, 2009.[20] The FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee met on August 11, 2010 to discuss the process and unanimously recommended approval of Potiga for the intended indication (add-on treatment of partial seizures in adults).[21][22] However, the possibility of urinary retention as an adverse effect was considered a significant concern, and the panel's members recommended that some sort of monitoring strategy be used to identify patients at risk of bladder dysfunction.[21] Potiga was approved by the FDA on June 10, 2010, but did not become available on the U.S. market until it had been scheduled by the Drug Enforcement Administration.[12]

In December 2011, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) placed the substance into Schedule V of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), the category for substances with a comparatively low potential for abuse. This became effective 15 December 2011.[23]

Name

The International Nonproprietary Name "retigabine" was initially published as being under consideration by WHO in 1996.[24] This was later adopted as the recommended International Nonproprietary Name (rINN) for the drug, and, in 2005 or 2006, the USAN Council—a program sponsored by the American Medical Association, the United States Pharmacopeial Convention, and the American Pharmacists Association that chooses nonproprietary names for drug sold in the United States—adopted the same name.[25] In 2010, however, the USAN Council rescinded its previous decision and assigned "ezogabine" as the United States Adopted Name for the drug.[26] The drug will thus be known as "ezogabine" in the United States and "retigabine" elsewhere.

References

- ^ Ferron GM, Paul J, Fruncillo R, et al. (February 2002). "Multiple-dose, linear, dose-proportional pharmacokinetics of retigabine in healthy volunteers". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (2): 175–82. doi:10.1177/00912700222011210. PMID 11831540. S2CID 5568963.

- ^ "POTIGA (ezogabine) Tablets, CV. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline and Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57fe4b6640f0b6713800000c/Trobalt_letter.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Epilepsy drug Trobalt (retigabine) to be discontinued". epilepsysociety.org.uk. 14 September 2016.

- ^ a b Rundfeldt C (October 1997). "The new anticonvulsant retigabine (D-23129) acts as an opener of K+ channels in neuronal cells". European Journal of Pharmacology. 336 (2–3): 243–9. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01249-1. PMID 9384239.

- ^ a b Main MJ, Cryan JE, Dupere JR, Cox B, Clare JJ, Burbidge SA (August 2000). "Modulation of KCNQ2/3 potassium channels by the novel anticonvulsant retigabine". Molecular Pharmacology. 58 (2): 253–62. doi:10.1124/mol.58.2.253. PMID 10908292. S2CID 11112809.

- ^ a b Rogawski MA, Bazil CW (July 2008). "New Molecular Targets for Antiepileptic Drugs: α2δ, SV2A, and Kv7/KCNQ/M Potassium Channels". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 8 (4): 345–52. doi:10.1007/s11910-008-0053-7. PMC 2587091. PMID 18590620.

- ^ a b c d Ben-Menachem E (2007). "Retigabine: Has the Orphan Found a Home?". Epilepsy Currents. 7 (6): 153–4. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7511.2007.00209.x. PMC 2096728. PMID 18049722.

- ^ a b c Plosker GL, Scott LJ (2006). "Retigabine: in partial seizures". CNS Drugs. 20 (7): 601–8, discussion 609–10. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620070-00005. PMID 16800718.

- ^ a b Porter RJ, Partiot A, Sachdeo R, Nohria V, Alves WM (April 2007). "Randomized, multicenter, dose-ranging trial of retigabine for partial-onset seizures". Neurology. 68 (15): 1197–204. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000259034.45049.00. PMID 17420403. S2CID 24574886.

- ^ "Potiga (Ezogabine): Drug Safety Communication". Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ a b Hitt E (2011-06-13). "FDA approves ezogabine for seizures in adults". Medscape. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ a b c d e "Trobalt – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. 2011-05-05. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ a b c Łuszczki JJ (2009). "Third-generation antiepileptic drugs: mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics and interactions" (PDF). Pharmacology Reports. 61 (2): 197–216. doi:10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70024-6. PMID 19443931.

- ^ Brown, DA; Passmore, GM (2009). "Neural KCNQ (Kv7) channels". British Journal of Pharmacology. 156 (8): 1185–95. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00111.x. PMC 2697739. PMID 19298256.

- ^ Corbin-Leftwich, Aaron; Mossadeq, Sayeed M.; Ha, Junghoon; Ruchala, Iwona; Le, Audrey Han Ngoc; Villalba-Galea, Carlos A. (March 2016). "Retigabine holds KV7 channels open and stabilizes the resting potential". The Journal of General Physiology. 147 (3): 229–241. doi:10.1085/jgp.201511517. ISSN 0022-1295. PMC 4772374. PMID 26880756.

- ^ Villalba-Galea, Carlos A. (2020-06-19). "Modulation of KV7 Channel Deactivation by PI(4,5)P2". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 11: 895. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00895. ISSN 1663-9812. PMC 7318307. PMID 32636742.

- ^ Rogawski MA (June 2006). "Diverse Mechanisms of Antiepileptic Drugs in the Development Pipeline". Epilepsy Research. 69 (3): 273–94. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.02.004. PMC 1562526. PMID 16621450.

- ^ "Valeant Pharmaceuticals Announces Preliminary Results From Its Phase IIa Retigabine Study for the Treatment of Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN)" (Press release). PRNewswire. 2009-08-24. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ "Retigabine NDA accepted for filing" (Press release). PRNewswire. 2009-12-30. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ^ a b Lowry F (2010-08-12). "Epilepsy drug exogabine gets green light from FDA Advisory Panel". Medscape. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ^ [No authors listed] (2010-06-25). "August 11, 2010: Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Announcement". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ^ U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (15 December 2011). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Ezogabine Into Schedule V" (PDF). Federal Register. 76 (241).

- ^ World Health Organization (1996). "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN). Proposed INN: List 76" (PDF). WHO Drug Information. 10 (4): 215. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2004.

- ^ [No authors listed] (2005–2006). "Statement on a nonproprietary name adopted by the USAN council: Retigabine" (PDF). American Medical Association. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ^ [No authors listed] (2010). "Statement on a nonproprietary name adopted by the USAN council: Ezogabine" (PDF). American Medical Association. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Further reading

- Flupirtine

- Blackburn-Munro G, Dalby-Brown W, Mirza NR, Mikkelsen JD, Blackburn-Munro RE (2005). "Retigabine: chemical synthesis to clinical application". CNS Drug Rev. 11 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2005.tb00033.x. PMC 6741764. PMID 15867950.

- Hempel R, Schupke H, McNeilly PJ, et al. (May 1999). "Metabolism of retigabine (D-23129), a novel anticonvulsant". Drug Metab Dispos. 27 (5): 613–22. PMID 10220491.

External links

- "Ezogabine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.